Nicolas Gonne

OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2023

2. Lifting labour supply to tackle tightness

Abstract

The Dutch labour market is strong but very tight. The unprecedently fast recovery from the pandemic, fast-changing skill demand, low hours worked, and the segmentation of the labour market contribute to labour shortages, weighing on growth potential and jeopardising the green and digital transitions. To tackle shortages, lifting labour supply is a necessary complement to raising productivity, as labour-saving innovation alone is unlikely to significantly reduce overall labour demand. Lowering the effective tax rate on moving from part-time to full-time employment and streamlining income-dependent benefits while improving access to childcare would both increase labour input and reduce gender inequalities in career prospects, incomes, and social protection. Narrowing regulatory gaps between regular and non-standard forms of employment further would alleviate shortages by facilitating transitions between occupations. Better integrating people with a migrant background and easing medium-skill labour migration in specific occupations would help to fill vacancies, especially those related to the low-carbon transition. Scaling up the individualised training scheme while ensuring quality and providing stronger incentives for co-financing by employers would boost the supply of skills and promote growth in expanding industries. Rewarding teachers in schools where shortages are significant and facilitating mobility between vocational and academic tracks would improve equality in education and better prepare the future workforce.

The labour market is strong, but shortages weigh on growth prospects

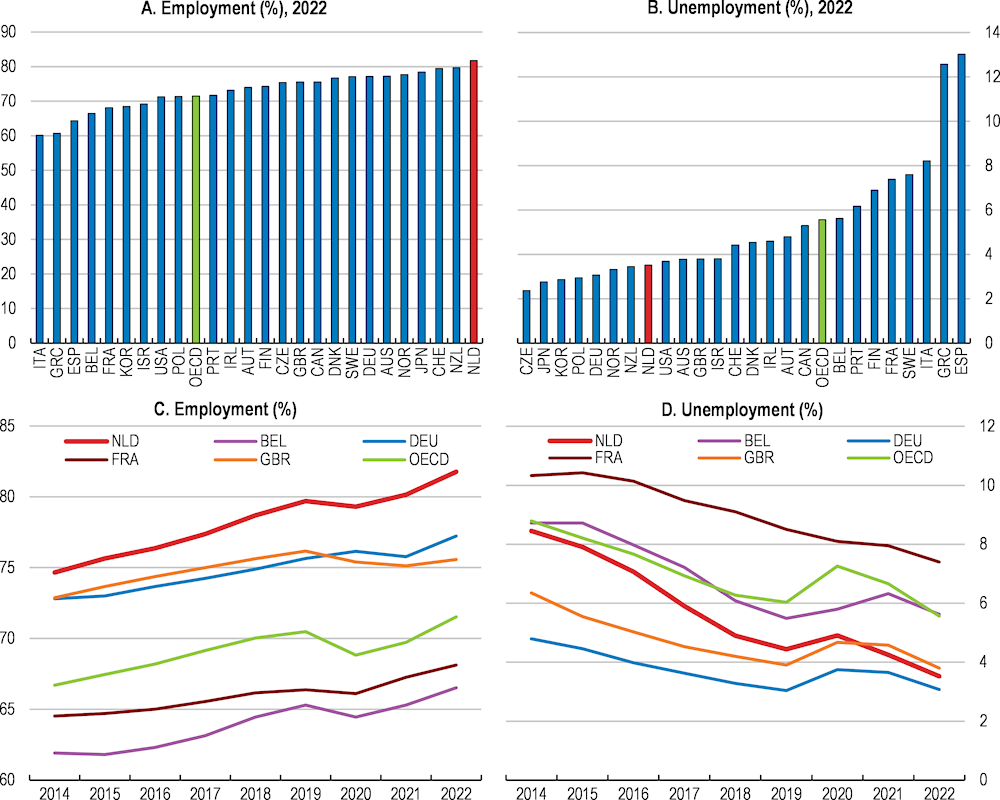

The Dutch labour market is very strong in international comparison. The employment rate is one of the highest in the OECD, at 81.8% of the population aged 15 to 64 in 2022 (Figure 2.1, Panel A), while the unemployment rate is relatively low, at 3.5% (Figure 2.1, Panel B). Moreover, workers are paid well on average, with wages among the highest in the OECD in purchasing power parity terms (OECD, 2022[1]). Finally, the share of employees experiencing job strain appears significantly lower than the OECD average (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[2]). This contributes to making the Netherlands one of the OECD countries with the highest reported life satisfaction (OECD, 2020[3]).

The Dutch employment rate has been increasing steadily since the mid-2010s, reaching historically high levels (Figure 2.1, Panel C). This mostly reflects rising participation and inflows from inactivity to non-standard forms of employment (OECD, 2021[4]), particularly own-account workers (zelfstandigen zonder personeel, ZZP). Major labour law reforms underlie these trends, including the 2015 Law on work and security (Wet werk en zekerheid) and the Law on participation (Participatiewet), which increased labour market flexibility but contributed to polarisation between regular and non-standard employment. The unemployment rate also decreased steadily (Figure 2.1, Panel D), due to the reforms but also to stronger incentives for municipalities to activate the long-term unemployed (OECD, 2023[5]).

Figure 2.1. Employment is historically high and unemployment, historically low

Note: Panels A and C refer to the share of the population aged 15-64. Panels B and D refer to the share of the labour force aged 15-64.

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics (database).

The Netherlands performs well on many, though not all, measures of labour market equality. Relative to other OECD countries, employment rates are equally high across gender, age groups and education levels. Women’s employment rate at 78% in 2022 is the second highest in the OECD, despite remaining about seven percentage points lower than men’s (OECD, 2022[6]). Moreover, wages are distributed relatively equally. Wage earners at the ninth decile of the distribution make a bit more than two and a half times as much as those at the first decile in 2021, comparable to Nordic countries and much lower than the OECD average of more than three times as much (OECD, 2022[7]). Yet, large gender gaps remain in hours worked and, therefore, in earnings.

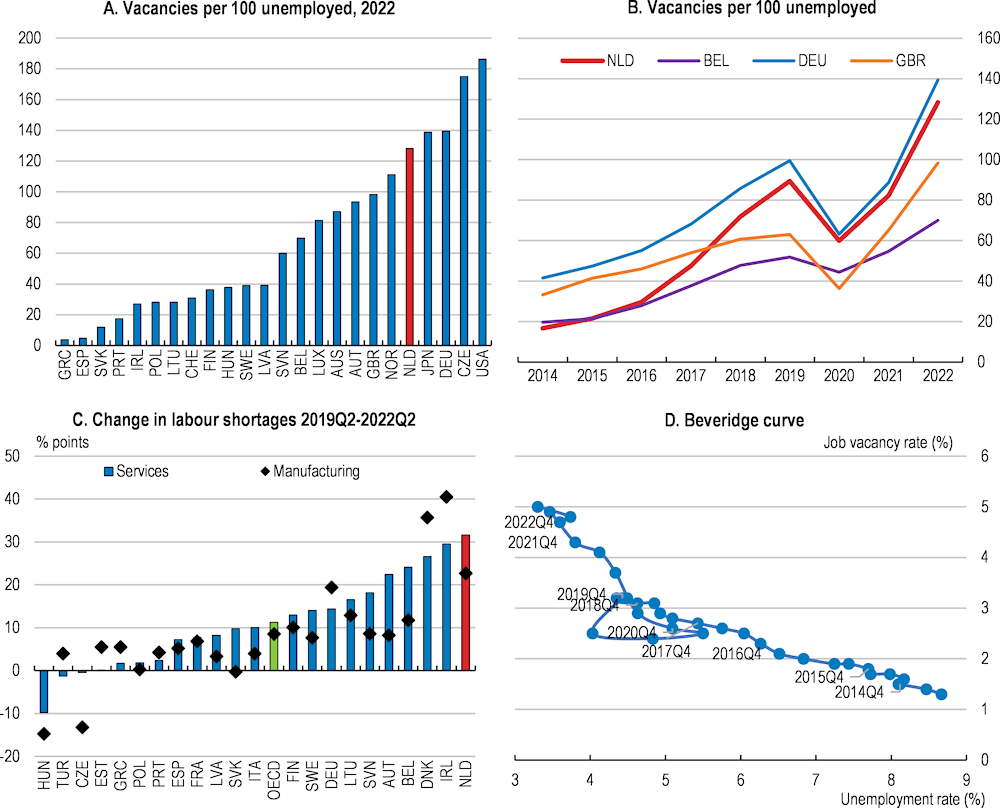

The labour market is also very tight in the Netherlands. Labour demand largely exceeds supply: vacancies are plenty, but available workers are scarce, with almost 130 vacancies per 100 unemployed in 2022, one of the largest vacancy-to-unemployment ratios in the OECD (Figure 2.2, Panel A). All measures of labour market demand and supply point to acute tightness in the Netherlands (Box 2.1). The vacancy rate, measured as the ratio of vacancies to the total of jobs, both occupied and vacant, stood above 5% in the second quarter of 2022, second only to the United States and substantially higher than the euro area average of 3.2% (OECD, 2022[8]). The number of people not in employment (either unemployed or inactive) has declined steadily in recent years, and an increasingly small fraction is available for work (CBS, 2022[9]).

Box 2.1. Measuring labour market tightness and shortages

Like many measures of economic outcomes, labour market tightness is the result of the simultaneous determination of demand and supply. Specifically, labour shortages arise when labour supply falls short of labour demand. Some indicators of labour market tightness focus on either demand or supply, while others explicitly or implicitly combine demand and supply statistics.

The job vacancy rate is a measure of labour demand, defined as the ratio of the number job vacancies to the total number of jobs, both occupied and vacant. Changes in the vacancy rate reflects changes in the ease with which positions are filled, so that an increase can be indicative of labour market tightness and risks of shortages.

The unemployment rate is a partial measure of slack in labour supply, defined as the ratio of unemployed to the labour force. Changes in the unemployment rate reflect changes in the available labour resources, so that a decrease can be indicative of labour market tightness and risks of shortages.

The vacancy-to-unemployment ratio is a direct measure of labour market tightness, defined as the ratio of the number of vacant positions to the number of unemployed. An increase in the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio indicates a tightening of the labour market and increasing risks of labour shortages.

The share of managers who report shortage of staff as a factor limiting production in business surveys is another direct measure of labour market tightness.

The job filling rate, measured as the ratio of the number of hires to the number of job vacancies, is a direct measure of labour market slack. A decrease in the job filling rate indicates a tightening of the labour market.

With the concomitant increase in vacancies and decrease in unemployment, the vacancies-to-unemployment ratio has been reaching all-time highs in the Netherlands (Figure 2.2, Panel B). The number of vacancies has been higher than the number of unemployed since the fourth quarter of 2021 (Eurostat, 2022[10]). Labour demand has been exceeding supply in many OECD countries due to the unprecedented speed of the post-pandemic recovery (OECD, 2022[11]; Causa et al., 2022[12]). However, the tightness of the Dutch labour market predates the pandemic: the number of vacancies per 100 unemployed stood at 89 in 2019 in the Netherlands, higher than in most OECD economies.

Tightness is not unique to the Dutch labour market, but the resulting labour shortages are particularly severe (Figure 2.2, Panel C), making it difficult for Dutch businesses to operate at their desired production level. Shortages of staff concerned one third of businesses in the second quarter of 2022 and have consistently been reported by managers as the main obstacle in carrying out business since the third quarter of 2021 (CBS, 2022[13]). While labour shortages were mostly limited to high-skill occupations before the pandemic, they have become pervasive across industries, occupations and regions in the Netherlands (UWV, 2022[14]; OECD, 2023[5]).

Figure 2.2. The labour market is increasingly tight

Note: Panels A and B refer to the ratio of job vacancies (s.a.) to the unemployed (s.a.) aged 15 and over; job vacancies comprise newly created, unoccupied and about to become vacant paid positions, except for Australia, Hungary, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States, where job vacancies refer to an estimate of unfilled vacancies, and for Japan, where job vacancies refer to active job openings. Panel C refers to the share of firms reporting labour shortages; 2019Q2 is an abuse of notation and refers to Q2 average over 2016-19.

Source: Eurostat Job Vacancy Statistics; Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training; OECD Labour Force Statistics (database); OECD (2022) OECD Employment Outlook 2022; Statistics Netherlands.

Labour shortages reflect a growing imbalance between labour supply and demand, and do not seem to result from a decline in matching efficiency between firms and workers. Indeed, the Beveridge curve, which captures the negative relationship between the job vacancy rate and the unemployment rate, does not exhibit a simultaneous increase in vacancies and in unemployment (Figure 2.2, Panel D), as in other OECD countries such as the United Kingdom or the United States (OECD, 2022[11]). Apart from a marked but brief decrease in vacancies at the onset of the pandemic and a loosening over the next couple of quarters, the Dutch labour market has been tightening continuously since the mid-2010s.

Imbalances between labour demand and supply appear to have peaked in the second quarter of 2022 as the economy started to slow (CBS, 2022[15]). At the same time, the government’s plans to increase employment in the public sector and in education and health, as set out in the 2021 Coalition Agreement, will partly aggravate the tightness of the labour market (CPB, 2022[16]). Public employment growth is driven in large part by significant staff needs related to the energy transition, especially at the local level, suggesting that labour shortages will remain in specific industries and regions (UWV, 2022[17]).

At first sight, labour market tightness may seem a blessing for workers, whose bargaining power increases as firms try to attract them by offering better pay and work conditions. Indeed, the post-pandemic increase in job-to-job transitions seems mostly driven by workers moving from one firm to the other within the same industry or occupation (OECD, 2022[11]). Workers with sought-after skills may enjoy a wage boost or obtain better employment conditions, including transitioning from flexible to regular employment. Moreover, relatively high labour costs tend to accelerate automation and other labour-saving innovations and investments, which supports productivity, thereby increasing living standards.

However, enduring labour market tightness is eventually detrimental to economic growth and well-being. Labour and human capital are key resources in the production process and cannot be perfectly substituted with physical capital or other inputs. Therefore, labour shortages not only reduce the volume of potential output in the long run, but also decrease the productivity of capital investment. A lack of workers in certain occupations can even have immediate and disruptive negative impact on access to essential goods and services, for example agriculture and food production, retail trade, healthcare or education, and hold back digitalisation, thereby weighing on productivity growth. Moreover, rising tightness risks bringing wage inflation and unsettling supply chains.

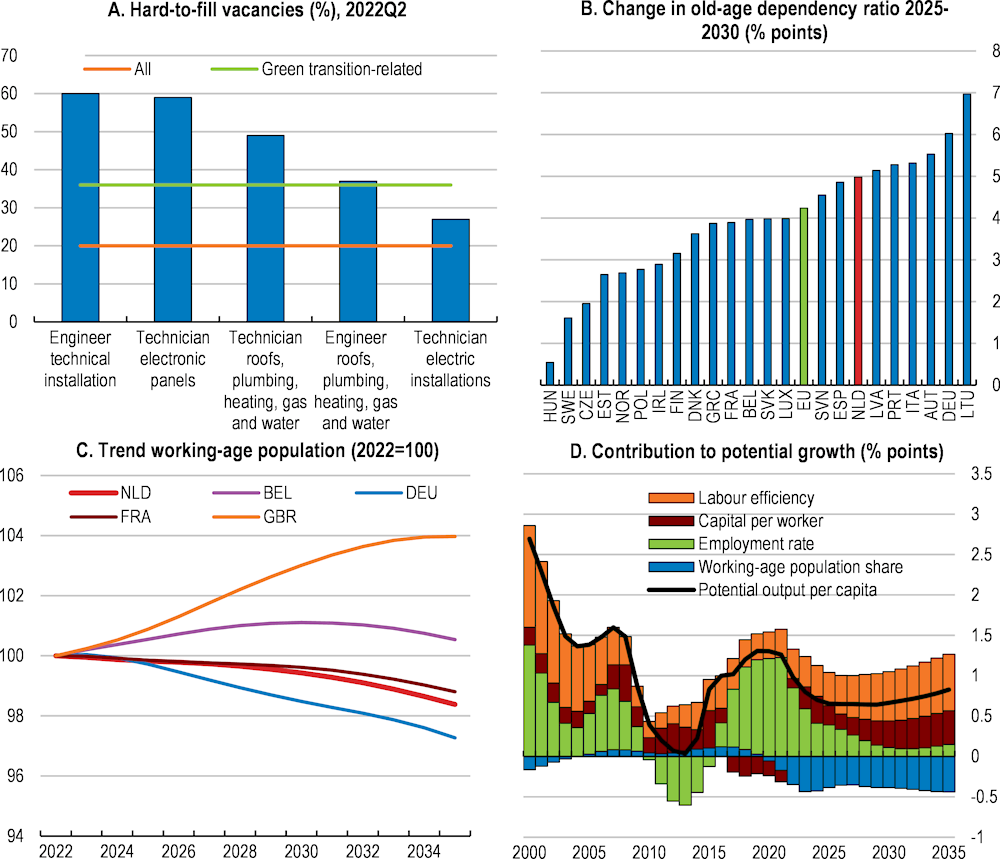

In the Netherlands, labour shortages specifically jeopardise the green transition, as most occupations related to low-carbon investments and maintenance face important shortages (Figure 2.3, Panel A). While about 20% of vacancies were hard to fill in the Netherlands as of the second quarter of 2022, the proportion reached 36% for occupations that are relevant for the low-carbon transition (ABN AMRO, 2022[18]). In the tightest occupations, such as electrical engineers or solar panel installers, more than half of vacancies are hard to fill. Limited availability of green skills constitutes an important bottleneck for the decarbonisation of the Dutch economy (Anderson et al., 2021[19]). Ensuring that adequate labour resources are available for the expansion of sectors that are instrumental in achieving the green transition is essential (Chapter 1), as the Dutch government recognises (EZK, OCW and SWZ, 2023[20]).

Labour shortages also compound challenges related to demographic change. The ratio of the population aged 65 and over to the population aged 20-64 will go up by about five percentage points between 2025 and 2030 in the Netherlands (European Commission, 2021[21]), which will raise labour demand in healthcare and other old-age industries (Figure 2.3, Panel B). The contraction of the Dutch working-age population will make the labour market even tighter in the medium run (Figure 2.3, Panel C). Moreover, the shrinking workforce will weigh on potential growth, with potential output projected to grow significantly slower over the period 2025-34 than over the period 2015-24, chiefly due to the negative contribution of the working-age population share (Figure 2.3, Panel D). Maintaining strong growth potential is a key reason to tackle tightness (Chapter 1).

Figure 2.3. Labour shortages compound climate and demographic challenges

Note: Panel B refers to the ratio of the population aged 65 and over to the population aged 20-64. Panel C refers to the population aged 15-74; fertility, mortality and migration parameters follow the assumptions of Eurostat and the United Nations as of January 2023.

Source: ABN AMRO; European Commission; Institute for Employee Insurance; OECD Economics Department Long-Term Model.

Both supply and demand can adjust to address labour market imbalances. From a macroeconomic perspective, wage developments have not fully reflected the disequilibrium between supply and demand yet. On the structural demand side, automation and other labour-saving innovation can raise labour productivity, enabling the reallocation of labour inputs towards industries and occupations where such investments are not yet profitable or feasible. Digitalisation is a key enabler of productivity growth and requires technology adoption by firms, access to complementary skills and investment in research and development, as discussed in depth in the thematic chapter of the previous OECD Economic Survey of the Netherlands (OECD, 2021[4]). It is important to note that the available evidence suggests that labour-saving innovation and higher productivity do not reduce overall labour demand but rather alter its composition (Squicciarini and Staccioli, 2022[22]; Aghion et al., 2020[23]; Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2019[24]; Graetz and Michaels, 2018[25]). On the supply side, structural policy reforms to lift labour supply can contribute to reduce labour shortages. These policies are the focus of the present thematic chapter.

Beyond addressing labour shortages, lifting labour supply also offers an opportunity to enhance social cohesion. Participation in the labour market provides an important pathway to social integration, particularly for vulnerable groups, such as migrants and their offspring. Enhanced labour market opportunities can also reduce incentives to participate in the informal economy.

This chapter reviews the options available to increase labour supply. It first describes the key factors behind the tight labour market in the Netherlands, before discussing policy options to address them. These include reforming taxes and benefits to strengthen work incentives; alleviating the maternity penalty to counter gender norms hampering labour supply; reducing labour market fragmentation to ease transitions between occupations; better integrating migrants and facilitating labour migration for shortage occupations; stepping up lifelong learning to promote growth in expanding industries; and upgrading compulsory education to better prepare the future workforce. The focus is on policies to boost the supply of labour; other policies that can contribute to a smoother functioning of the labour market, such as housing and transport infrastructure, were discussed in previous OECD Economic Surveys of the Netherlands (OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2018[26]; OECD, 2016[27]).

Both cyclical and structural factors underlie labour shortages

The Dutch labour market has been remarkably resilient despite the successive shocks of the pandemic, the inflow of refugees fleeing Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, and the energy crisis. The government swiftly intervened with support packages to protect jobs and firms during the pandemic (Box 2.2), limiting scarring on the labour market and enabling a speedy recovery. After a brief setback during the pandemic, employment continued to increase and unemployment to decrease steadily until mid-2022, before flattening (CBS, 2022[28]). Growth in the number of open vacancies strongly rebounded (CBS, 2022[29]), with the vacancy rate reaching about 5% in the second quarter of 2022 and stabilising since. Moreover, about 30 000 Ukrainian refugees (almost one out of two of working age) had found work in the Netherlands as of January 2023 (CBS, 2023[30]). The government is also implementing energy support measures to protect jobs in energy-intensive activities (Chapter 1).

Box 2.2. Measures to support the labour market during the COVID-19 pandemic

The support package was put in place in March 2020 and expired in March 2022 after being extended multiple times, with adjustments to eligibility thresholds and support parameters to reflect economic circumstances. The main measures were the following:

Temporary emergency scheme for job retention (NOW): a grant compensating parts of employers’ wage costs, conditional on a given fall in turnover; employers commit to retaining current jobs and paying 100% of the wages of the employees involved.

Self-employment income support and loan scheme (TOZO): a temporary support scheme for self-employed workers (without employees) under the form of a monthly allowance depending on the household situation; municipalities provide extra services to the self-employed, including retraining, and help upgrading existing skills and exploring new careers.

Fixed costs grant scheme (TVL): a compensation for the costs of businesses that have suffered a given turnover loss, with a maximum amount depending on firm size.

Other measures include tax deferral measures; support for specific sectors particularly hard hit by the pandemic; and the extension of existing state guarantee schemes for business loans, namely the Business Loan Guarantee Scheme (GO-C), the Small Credits Corona Guarantee Scheme (KKC), and the Credit Guarantee Scheme for Agriculture (BL-C).

A further social package of EUR 1.4 billion was allocated to help mitigate job losses, increase training and retraining efforts, combat youth unemployment and support poverty and debt reduction efforts.

Source: OECD (2021[4]) OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2021.

Overall, the pandemic does not appear to have changed workers’ preferences meaningfully. Growth in labour force participation resumed after a brief slowdown in 2020, and hours worked per job are not significantly lower than before the pandemic (CBS, 2022[31]). However, the crisis had a heterogeneous impact across occupations (OECD, 2021[4]) and has exacerbated pre-crisis labour market issues, notably employment insecurity for the low-skilled and labour shortages in non-market services such as healthcare and education (SER, 2021[32]).

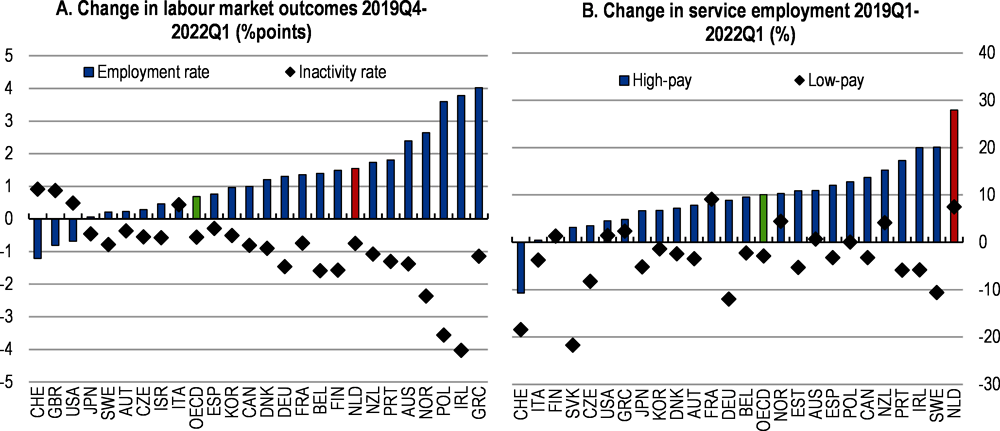

Exceptional macroeconomic conditions contributed to tightness across-the-board

Cyclical factors are partly behind the tight labour market. As economies reopened when the pandemic receded, OECD economies recovered quickly, and labour demand surged. The Dutch labour market rebounded fast, with the employment rate in the first quarter of 2022 more than 1.5 percentage points higher than before the pandemic (Figure 2.4 Panel A). The Dutch recovery was broad-based, with employment gains in both low-pay and high-pay services (Figure 2.4, Panel B). Rising public employment, including in the education and health sectors, also contributes to labour market tightness (CPB, 2022[16]).

Figure 2.4. Labour markets rebounded exceptionally fast

Note: Panel A refers to the population aged 15-64. Panel B refers to employment in service industries; low-pay services comprise Accommodation and Food Service Activities, Administrative and Support Service Activities, Arts, Entertainment and Recreation, Wholesale and Retail Trade, and Transportation and Storage; high-pay services comprise Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities, Information and Communication, and Financial and Insurance Activities.

Source: OECD (2022) OECD Employment Outlook 2022.

At the same time as labour demand surged, labour supply was held back by a number of factors compared to the pre-pandemic trend, including the protracted weakness of net labour migration (Bodnár and O’Brien, 2022[33]), and the lingering pandemic that made contact-intensive, low-paid jobs less appealing. Moreover, while measures to support workers and firms during the COVID-19 pandemic prevented unnecessary scarring by preserving worker-firm matches at illiquid but viable firms (Box 2.2), they also sunk labour inputs at unproductive firms, which may have contributed to labour shortages during the recovery. Indeed, bankruptcies plummeted in the second quarter of 2020 and remain significantly below pre-pandemic levels (CBS, 2022[34]), suggesting that support kept unviable firms active. In the Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Utrecht districts (COROP-gebied), which account for about one quarter of the Dutch labour force, bankruptcies were about 50% lower in 2021 than before the pandemic (OECD, 2023[5]).

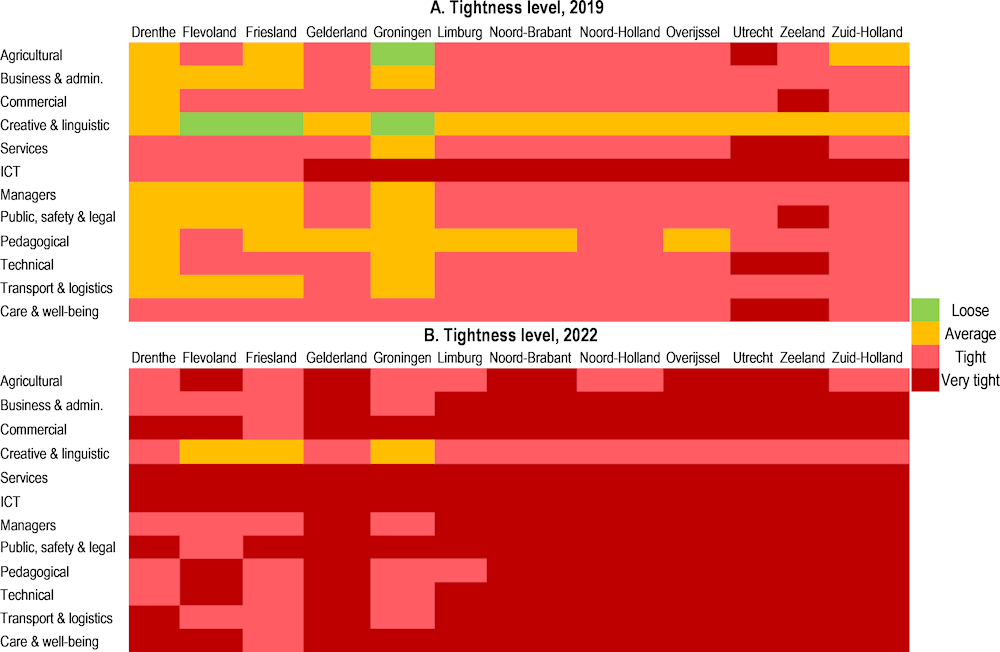

The pervasiveness of labour market tightness across industries, occupations and regions in the post-pandemic recovery suggests that the current situation is not solely driven by the scarcity of a specific type of labour that could arise, for example, from the asymmetric impact of the crisis across sectors (OECD, 2022[11]). Pre-pandemic, tensions were restricted to occupations in information and communication technologies (ICT) and, to a lesser extent, in care and wellbeing and in technical occupations, as well as in pedagogical occupations in large cities (Figure 2.5, Panel A). Post-pandemic, shortages have become widespread across occupations and regions, and are also affecting rural provinces and lower-skill occupations, including most services that had been affected by lockdowns (Figure 2.5, Panel B). Although the Netherlands is characterised by strong regional industrial specialisation (Anderson et al., 2021[19]), only six of the 35 local labour markets (arbeidsmarktregios) were not very tight as of mid-2022, according to the classification of the Dutch public employment services (UWV, 2022[14]). Measures of labour market tightness and shortages at a more disaggregated level could help point to potential underlying causes of the labour demand-supply disequilibrium, but measuring labour supply at the industry or occupation level is challenging.

Figure 2.5. Labour demand exceeds supply across occupations and regions

Note: Indicators refer to the Institute for Employee Insurance (UWV)’s ordinal index of labour market tension (spanningsindicator arbeidsmarkt), defined at the occupation-province level based on a logarithmic transformation of the ratio of the number of vacancies to the number of people who have been receiving unemployment benefits for fewer than six months.

Source: Institute for Employee Insurance.

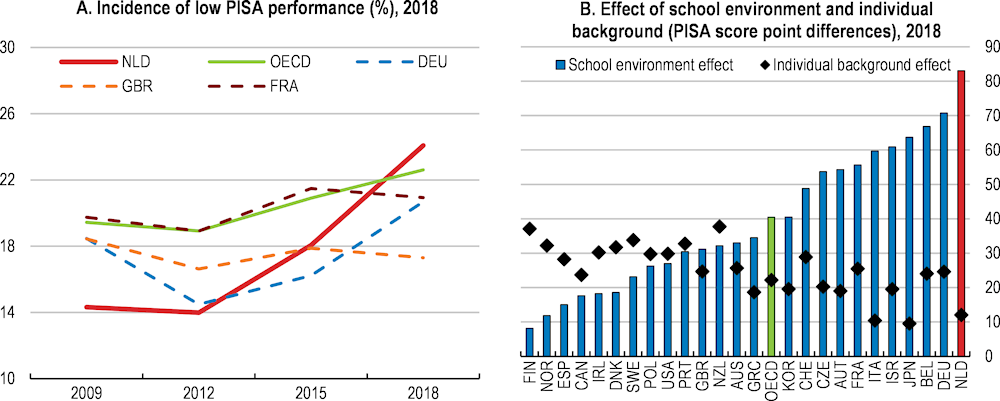

Skill mismatches endure, creating bottlenecks in specific industries

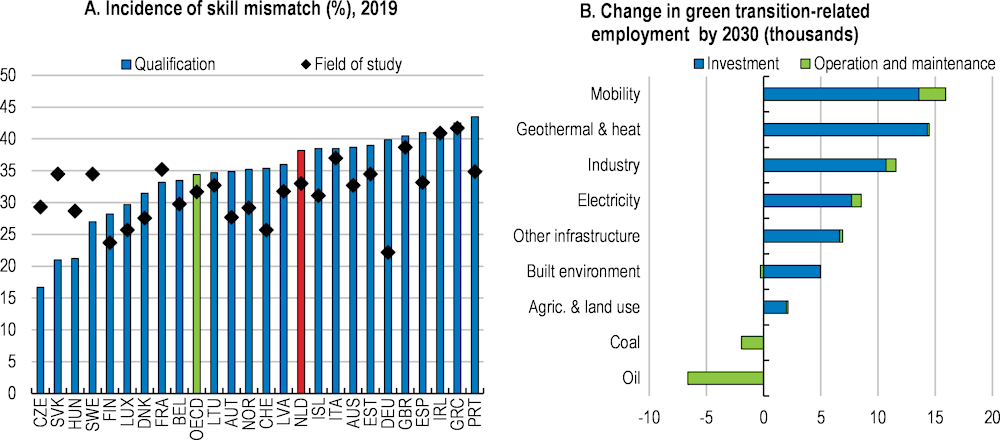

Beyond the business cycle and pandemic-related factors that are expected to subside, structural factors have been playing an important role in making the labour market increasingly tight. Digitalisation and the low-carbon transition have been altering the skill composition of labour demand since before the pandemic (TNO, 2021[35]). The ensuing skill mismatch is important in the Netherlands (Figure 2.6, Panel A) and expected to increase in the absence of policy intervention. Green skills are in particularly high demand, given the country’s ambitious climate goals. Estimates suggest that realising the necessary investments to achieve a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 requires about 28 000 technical jobs to be created and filled, more than the 26 000 full-time equivalents currently employed in the Dutch energy sector, including network operators (Ecorys, 2021[36]). Other estimates, based on early assessments of all the necessary measures required to reach the Climate Agreement’s objectives, point to 39 000 to 72 000 direct and indirect extra jobs (PBL, 2018[37]; TNO, 2019[38]), accounting for the reduction in contracting sectors, such as fossil fuels industries (Figure 2.6, Panel B). The supply of other specific skills is also falling increasingly short of demand, particularly in ICT occupations (Eurostat, 2022[39]).

Figure 2.6. Rising labour demand for green jobs exacerbates skill mismatch

Note: Panel A refers to the share of workers whose qualification or field of study do not match their job requirements; data for Australia are from 2016. Panel B refers to indicative projections by the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) based on the 2018 assessment by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) of the Climate Agreement; data are in full-time equivalent.

Source: OECD Skills for Jobs (database); TNO (2019) “Verkenning werkgelegenheidseffecten van klimaatmaatregelen”.

By contrast, the COVID-19 crisis likely accelerated digitalisation and automation of repetitive tasks, a development that could alleviate shortages of middle-skilled labour in some industries that were hit hard by the pandemic, notably administrative and support services and transportation and storage (OECD, 2021[4]). Robotisation could partly address shortages in other industries such as long-term care, as in Japan where robots replace nurses for some tasks. Although hard evidence is not available yet, anecdotal evidence points to a growing landscape of Dutch start-ups working to bring AI-driven labour-saving technologies to the market, like in many other OECD countries (AI.nl, 2022[40]; AI.nl, 2022[41]).

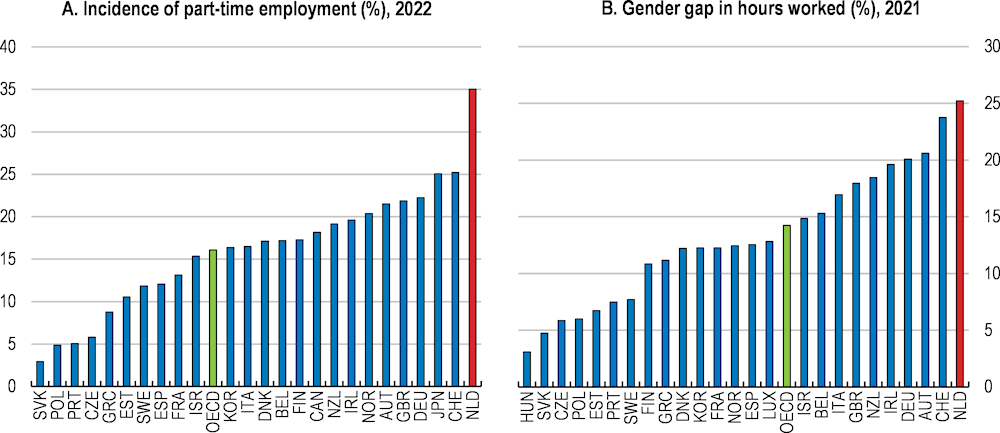

The prevalence of part-time work explains low labour input despite high employment

The high incidence of part-time work also contributes to a structural labour supply shortfall in the Netherlands. Despite remarkably high participation and employment, labour utilisation is paradoxically low, as more than one out of three employees worked less than 30 hours per week in 2022, by far the largest proportion in the OECD (Figure 2.7, Panel A). When measured based on Statistics Netherlands’ convention of fewer than 35 hours a week for part-time employment, the incidence reaches almost 50% of the working population (CBS, 2022[42]). Low labour utilisation is also reflected in low average hours worked at roughly 1 400 per worker per year, the fourth lowest in the OECD, higher than Germany’s 1 350 but significantly lower than France’s and the United Kingdom’s roughly 1 500 hours or the United States’ almost 1 800 hours (OECD, 2022[43]). The gap partly closes when looking at hours worked per capita over the lifetime, as widespread possibilities of part-time work come with and partly encourage high participation from a young age.

Figure 2.7. The incidence of part-time work is high and uneven between genders

Note: Panel A refers to the share of employees aged 15 and over who usually work less than 30 hours per week in their main job. Panel B refers to the difference between women’s and men’s average hours worked as a share of men’s, for workers aged 15-64.

Source: OECD Labour Market Statistics (database).

Social institutions and cultural factors, rather than economic incentives and rationale, appear to determine the incidence of part-time work, inducing a large gender gap in hours worked (Figure 2.7, Panel B). Indeed, part-time work is distributed particularly unequally between genders: about 55% of Dutch women work part-time, almost three times the rate for Dutch men and more than twice the OECD average for women (OECD, 2022[44]). Based on Statistics Netherlands’ definition mentioned above, almost three out of four women work part time, versus a bit more than one out of four men (SCP, 2022[45]; CBS, 2022[42]). Women work as much as men when both paid and unpaid work are considered, but spend almost four hours per day in unpaid work on average, versus less than two and a half hours for men (OECD, 2023[46]). Such imbalance constitutes a significant misallocation of human capital and leads to large gender gaps in earnings, wealth and pensions, and slower progression of women into management roles (OECD, 2021[4]). Moreover, while Dutch women’s labour market participation at the extensive margin is particularly high and surveys generally find part-time employment to be voluntary within the current cultural and institutional setting (SCP, 2022[47]), the underutilisation of women’s labour resources at the intensive margin contributes to labour shortages (Box 2.5 below).

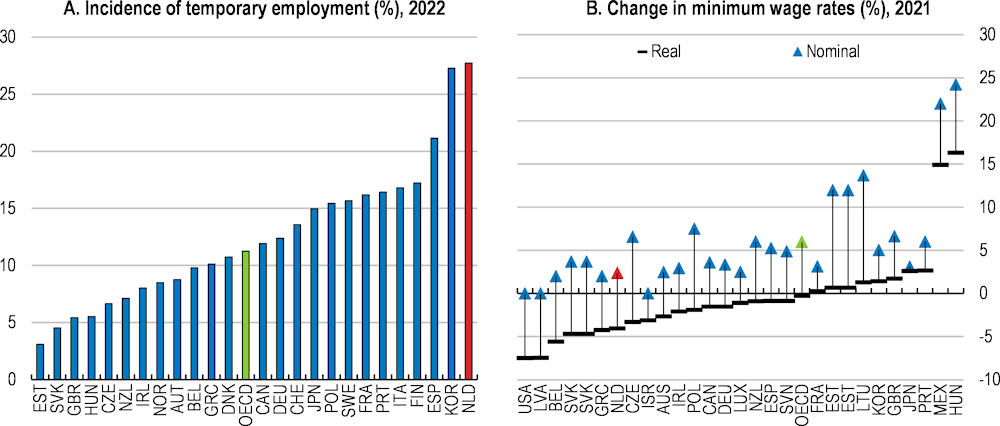

Unfavourable working conditions in some sectors likely discourage vulnerable workers

Non-standard forms of employment provide more flexibility in working relationships, as well as a flexible labour margin, which can increase labour utilisation. In the Netherlands, the strong flexibility of the labour market contributed to increasing participation and employment to historically high levels (Box 2.3). The incidence of temporary employment at 27.4% in 2021 is among the highest in the OECD (Figure 2.8, Panel A), mainly reflecting greater flexibility in specific segments of the labour market following the 2015 labour law reforms. Similarly, favourable tax treatment for the self-employed and lower social security contributions have contributed to significantly increasing self-employment, both by enabling individuals to make that career choice, but also by incentivising employers to hire own-account workers.

Figure 2.8. Temporary employment is pervasive and the real minimum wage falling

Note: Panel A refers to the share of dependent employees whose contract has a pre-determined termination date. Panel B refers to changes between January 2021 and January 2022.

Source: OECD Labour Market Statistics (database); OECD (2022) OECD Employment Outlook 2022.

However, unfavourable working conditions in some parts of the economy likely reduce labour supply and structurally contribute to tightness on the labour market. Non-standard employment typically offers lower job quality, weaker income security (e.g., in case of shocks such as the pandemic) and fewer lifelong learning opportunities compared to workers on standard contracts (OECD, 2020[48]). In the Netherlands, workers hired through employment agencies are less likely to remain employed or to obtain a permanent contract, make lower pension contributions and experience lower growth in hourly wages (Scheer et al., 2022[49]). The 1.7 million workers on flexible contracts (short-term, agency and other non-standard forms of employment) in 2020 earn less, have lower social protection and worse career prospects (OECD, 2021[4]; DNB, 2021[50]). The self-employed are less well protected regarding disability and pensions.

Such strong segmentation can end up discouraging vulnerable workers who are not productive enough compared to the cost of permanent employment, and detaching them from the labour market. The 2020 report of the Commission for the regulation of work (commissie regulering van werk, also known as the Borstlap Commission) recommended reducing the differences between forms of employment (Box 2.6 below). The government started to rescind some of the tax advantages for non-standard employment, but further reforms are needed to level the playing field between employment and self-employment, as recommended in Chapter 1. The labour market package recently presented by the government goes in the right direction (SZW, 2023[51]).

Subdued wage growth despite structural labour shortages is another factor that may weigh on labour supply. Minimum wages have decreased significantly in real terms over 2021 in the face of high inflation (Figure 2.8, Panel B) and keep falling, as in many countries (OECD, 2022[52]), even with the 10% increase in January 2023 (Chapter 1). Many benefits and collective labour agreements are indexed on minimum wage rates, so that average wages follow a comparable pattern overall. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, annual consumer price inflation has outpaced growth in collectively agreed gross wages in seven out of 15 years (CBS, 2022[53]), even as the labour market was tightening. The increase in regular employment from 2018 until the pandemic partly explains the puzzle of stagnating real wages in a tight labour market, as workers in non-standard forms of employment negotiate permanent contracts rather than higher wages (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. Employment growth in the Netherlands: evidence at the occupation-contract level

Historically high participation and employment in the Netherlands mainly reflect growth in non-standard forms of employment due to major labour market reforms, including the 2015 Law on work and security (Wet werk en zekerheid) and the Law on participation (Participatiewet).

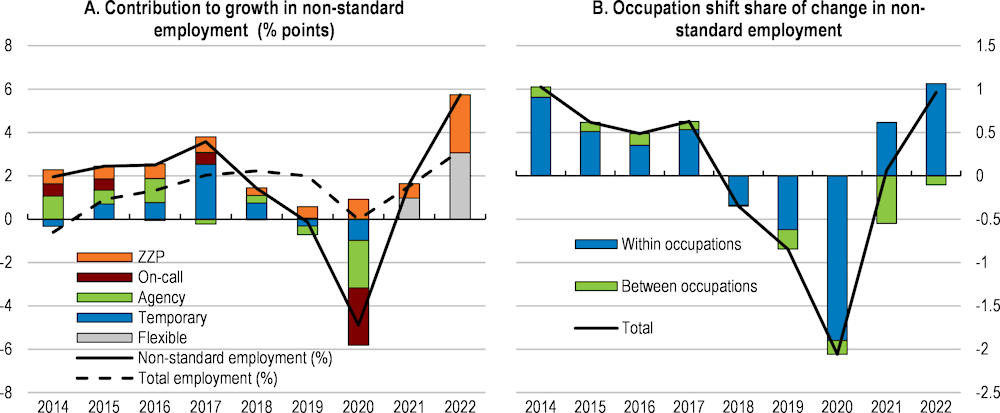

The self-employed without employees have consistently accounted for a substantial part of the increase in the share of non-standard employment since 2014, while on-call, agency and temporary employment tend to follow the business cycle (Figure 2.9, Panel A). The slowing contribution of non-standard employment to total employment growth from 2018 until the pandemic likely reflects workers on flexible contracts negotiating permanent contracts instead of higher wages as the labour market tightens. Recent analysis based on data at the occupation-type of contract level shows that changes in non-standard employment occurred across occupations, as opposed to only in occupations more conducive to flexible work (Figure 2.9, Panel B).

Figure 2.9. Non-standard employment grew across the board

Note: Non-standard employment comprises workers on temporary contracts, agency workers, on-call workers and the self-employed without employees (zelfstandigen zonder personeel, ZZP); the flexible category comprises workers on temporary contracts, agency workers and on-call workers.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Netherlands Statline.

Lifting labour supply is necessary to tackle shortages

Structural policies to address labour shortages work through two main channels. First, policies can directly increase labour supply by tapping into available but unused labour resources. Such policies mainly focus on encouraging longer hours worked, activating the unemployed, bringing the inactive back into the workforce or facilitating labour migration. Second, policies can promote the efficient reallocation of labour resources towards expanding, higher productivity activities. Both channels are critical in the Netherlands, where the workforce will be contracting, and the composition of labour demand is changing rapidly due to the urgent need to reduce the country’s carbon emissions.

No single structural policy reform can achieve the desired increase in labour supply to fully address labour shortages in the Netherlands. The policy discussion below focuses on six policy areas that together have the potential to raise labour input. The success of the proposed reforms hinges on the complementarity between policies, requiring a multipronged, whole-of-government approach with the overarching objective to lift labour supply.

Reforming taxes and benefits to strengthen work incentives

Labour tax and benefit systems have important effects on individuals’ decision regarding their labour supply, both whether to participate (the extensive margin) and how many hours to work (the intensive margin). Taxes and benefits reduce economic insecurity by cushioning the impact of adverse labour market transitions, e.g., into unemployment, but also need to strike the balance with maintaining strong work incentives (OECD, 2019[54]). Moreover, to ensure that all available human capital is used at its potential, tax and benefit systems need to be free of implicit biases against specific groups due to their specific socio-economic realities, e.g., women due to institutional and cultural preferences regarding parenting (Harding, Perez-Navarro and Simon, 2020[55]).

In the Netherlands, taxes and benefits discourage the supply of labour in two important instances. First, disincentives are strong at the intensive margin for middle-income couples with children, which is a key explanation for the particularly low performance in terms of hours worked despite one of the highest participation rates in the OECD. Second, disincentives are also substantial at the extensive margin for single parents who are dependent on childcare services to enter employment, which suggests that there is room to increase participation even further. The government is considering several ways to reduce marginal tax rates on labour income (SZW, 2023[56]).

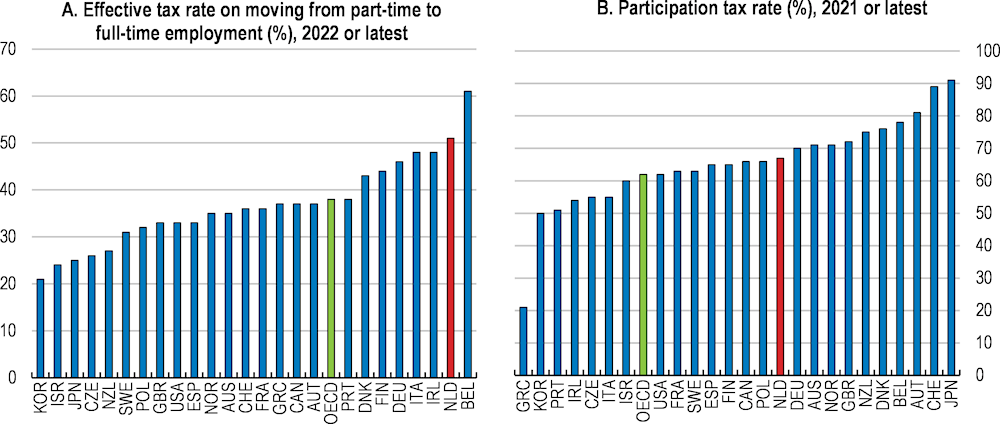

The effective tax rate on increasing hours worked is particularly high for second earners in the Netherlands (Figure 2.10, Panel A). The fraction of additional earnings lost to either higher taxes or lower benefits when a second earner increases hours worked from part-time to full-time work was more than 50% in 2022. While the system of taxes and benefits encourages second earners to enter employment in the Netherlands, it strongly discourages them to work full time. Dutch authorities have introduced several tax incentives for second earners to work more, including stronger in-work benefits (inkomensafhankelijke combinatiekorting, IACK, which will be phased out by 2025), a childcare allowance, and limits on the transferability of the general tax credit between partners, with little effect on participation at the intensive margin. Marginal tax rates on labour income are even set to increase slightly on average across households under the 2023 Tax Plan (Box 2.4), in large part because of the increase in income-dependent benefits as part of the comprehensive energy support package (Financiën, 2022[57]).

Part-time work is often presented as a cultural preference in the Netherlands, irrespective of the tax system or other institutions. The “male breadwinner” model is also frequently explained away as an economically efficient division of labour, in which the higher earner specialises in the labour market and the lower earner specialises in household labour. Yet, these explanations are at odds with the large gains in human capital accumulated by Dutch women over the past decades, as measured by educational achievement (OECD, 2022[58]). Moreover, the Netherlands is one of the few OECD countries where the gender wage gap is quasi-inexistent for individuals in their twenties (OECD, 2017[59]), which also runs counter to the efficiency argument.

Figure 2.10. Lower effective taxation could increase work incentives

Note: Tax rates include social assistance, temporary in-work benefits, and housing benefits. Panel A refers to the share of gross earnings in a job that pays the average wage when increasing hours worked from 50% to 100% of full-time employment, for a second earner with two children and a partner working full-time in a job that pays the average wage. Panel B refers to the share of gross earnings in a new job that pays 67% of average wage, for a single person with two children claiming guaranteed minimum income and using childcare services.

Source: OECD Benefits, Taxes and Wages (database).

Box 2.4. Recent reforms in labour taxation and benefits in the Netherlands

The maximum IACK (inkomensafhankelijke combinatiekorting) was reduced by EUR 395 in 2022, with the aim to partially fund parental leave. This tax credit is provided at a rate of 11.45% of taxable income and aimed at incentivising participation for working single parents or second earners, conditional on children being below the age of 12 and the taxable income from employment exceeding EUR 4 993.

The averaging scheme, which allowed taxpayers with significant income fluctuations to average their income over three consecutive years, will be abolished with effect in 2023. The reform aims at simplifying the tax system and increasing tax compliance.

The tax deduction for the unincorporated self-employed will be gradually phased out until 2027, from EUR 6 310 in 2022 to EUR 900 in 2027.

Source: OECD (2022[60]) Tax Policy Reforms 2022; OECD (2022[61]) Taxing Wages 2022; Financiën (2022[62]).

The Netherlands should strengthen incentives for second earners to increase hours worked. The current tax structure is implicitly promoting the “one-and-a-half” worker model, whereby one partner (often a man) works full-time and the other partner (often a woman) works relatively few hours. Over 40% of Dutch partnered couples had this working arrangement in 2017, more than in any other European country (OECD, 2019[63]). As the large penalty for a second earner moving into full-time work (at average wage) is driven mostly by an increase in the income tax burden (OECD, 2019[63]), altering the income tax schedule would alleviate the bias, promote labour utilisation and reduce gender inequalities.

As labour market decisions also depend on factors other than taxes, interventions in complementary policy areas are required. Indeed, tax systems can only accommodate so many provisions to alter individuals’ labour input decisions. The Netherlands has gone relatively far already in providing tax incentives for second earners to increase their labour input (Cnossen and Jacobs, 2021[64]). While widespread teleworking has been providing workers with workplace and commuting flexibility since before the pandemic (Ker, Montagnier and Spiezia, 2021[65]), there is room to reduce work disincentives arising from childcare, schooling, and leave arrangements (Financiën, 2019[66]). A strong impetus is particularly needed to alleviate the so-called “maternity penalty” (next section).

Participation tax rates are also relatively high, discouraging labour market entry (Figure 2.10, Panel B). About two thirds of earnings are lost to higher taxes, lower benefits and net childcare costs when a parent with young children takes up full-time employment and uses full-time centre-based childcare, the second highest proportion in the OECD. The financial disincentive arises from the existence of income-dependent benefits that distort labour supply decisions. But the complexity of the system also plays a role. In the absence of clear information, some individuals refrain from entering the labour market out of fear of losing benefits.

The Netherlands should reduce the complexity of the benefits system, as a simpler and more straightforward system could help individuals make better-informed decisions about their participation in the labour market, especially the most vulnerable. The current system comprises no fewer than seven different income-dependent benefit schemes that interact non-linearly at different income thresholds, namely the housing benefit (huurtoeslag), the labour income tax credit (arbeidskorting), the additional labour income tax credit for working parents (inkomensafhankelijke combinatiekorting, IACK), the child allowance (kindgebondenbudget), the childcare allowance (kinderopvangtoeslag), the healthcare allowance (zorgtoeslag) and the general tax credit (algemene heffingskorting). Priority should be given to streamlining existing benefits, possibly into a system of fewer allowances and tax credits based on a limited number of household characteristics, for example income, assets and children. Such a reform was considered under the previous government, but rejected due to concerns related to the portability of benefits for Dutch citizens residing abroad. The government could start again from that basis and address the portability issue.

Alleviating the maternity penalty to counter gender norms hampering labour supply

Even if implicit and unintended, gender inequalities have large detrimental consequences on labour supply and potential output. The disproportionate share of housework performed by women tends to prevent them from committing time to and advancing in employment, which entrenches gender differences in the opportunity cost of unpaid work and ends up institutionalising them. Consequently, human capital is not allocated based on economic potential but on socially constructed circumstances. Therefore, the unequal distribution of part-time work between genders constitutes both an equity and an economic challenge (OECD, 2017[59]). While decisions regarding the sharing of housework ultimately lie with individuals, policies can reduce gender biases.

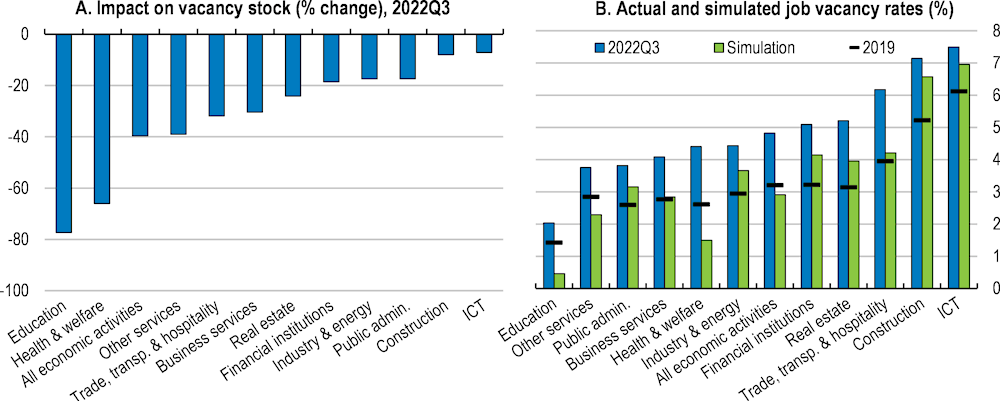

The significant underutilisation of women’s labour input due to their disproportionate uptake of part-time work contributes to labour market tightness in the Netherlands. Illustrative simulations suggest that partly closing the gender gap in part time work would substantially alleviate labour shortages in specific sectors (Box 2.5). For example, an increase in women’s labour input equivalent to a 15% reduction in gender gap in hours worked would reduce the stock of unfilled vacancies by more than half in the health sector.

Box 2.5. The impact of reducing the gender gap in part-time work on shortages: a simulation

Illustrative simulations show that increasing the average number of hours worked by women to achieve a 15% reduction in the gender gap in hours worked within industries would allow to fill about 40% of the current vacancy stock.

The effect would be particularly large in industries that disproportionately employ women, such as the health and education sectors (Figure 2.11, Panel A). Other sectors, such as construction and ICT, would remain tight (Figure 2.11, Panel B).

Figure 2.11. A lower gender gap in hours worked could alleviate labour shortages in some sectors

Note: Figures refer to the simulation of a 15% reduction of the gender gap in hours worked within industries.

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Netherlands Statline and on Eurostat Job Vacancy Statistics.

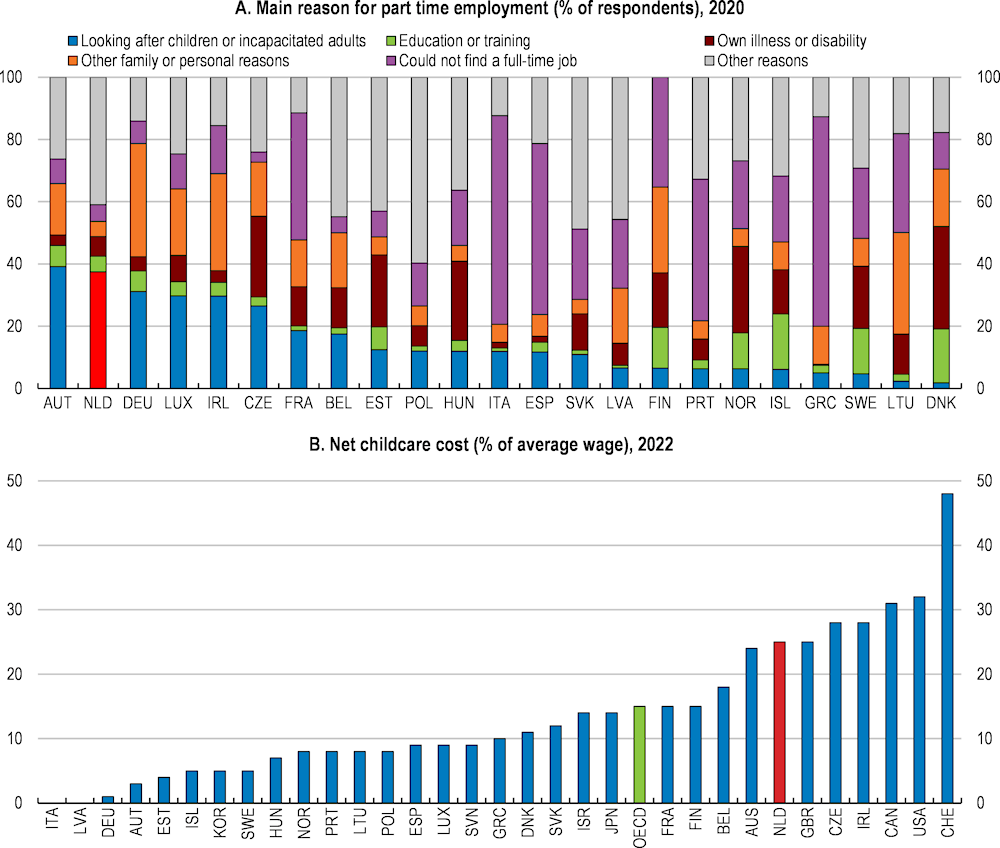

Looking after a child is the main reason for part-time employment in the Netherlands (Figure 2.12, Panel A), where childcare is expensive in international comparison (Figure 2.12, Panel B). The relatively low availability and affordability of childcare appears to be an important driver of the high incidence of part-time work. While enrolment in centre-based childcare is well above the OECD average, total hours spent in childcare is low (OECD, 2021[4]). Dutch women often transition to part-time work after they become a mother, like in many other countries. But the associated increase in the gender gap in hours worked is particularly large in the Netherlands (OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2019[63]). Moreover, the associated “maternity penalty” is estimated at 46% compared to the pre-birth earnings trajectory for the period 2005-2009 in the Netherlands, whereas father’s earnings are unaffected (Rabaté and Rellstab, 2021[67]).

The Netherlands should swiftly proceed with a fundamental childcare overhaul, as recommended in the previous OECD Economic Survey of the Netherlands (OECD, 2021[4]). Improving access to childcare and reducing its cost typically boosts uptake, which in the long run can contribute to changing the gender bias in attitudes towards mothers’ labour force participation (OECD, 2019[63]). The government’s reform of childcare support, with EUR 2.2 billion earmarked to subsidising 96% of childcare costs (up to a ceiling) for all working parents, goes in the right direction (SZW, 2022[68]). The simplification of support also provides parents with welcome certainty in the wake of the recent childcare benefit scandal. However, doubts have emerged regarding the feasibility of implementing the reform as rapidly as envisaged, given the strong expected increase in demand for childcare and staff shortages. Moreover, the untargeted nature of the subsidy and the fact that it does not depend on income pushes up the fiscal cost and possibly creates windfall gains for households who would have used childcare anyway, as was the case with the 2005 Childcare Act (Wet kinderopvang) (Bettendorf, Jongen and Muller, 2015[69]). Further, the concomitant phasing out of the IACK tax credit is expected to limit the positive labour supply effect of better childcare access (CPB, 2020[70]). Finally, failing to extend childcare access to those actively seeking a job would unnecessarily hamper their transition into employment. Monitoring the impact of the reform on access to childcare and contingency planning are required against the background of possible shortages. The effect of the 2023 repeal of the link between hours worked and the childcare allowance should be assessed: while it could improve inclusiveness by avoiding lock-out effects for low work intensity households, it will also weaken badly needed work incentives at the intensive margin.

Figure 2.12. More affordable childcare could boost women’s hours worked

Note: Panel A refers to respondents aged 25-64; data are the average over 2017-20, except for Bulgaria and the United Kingdom (2017-19). Panel B refers to costs for parents of two children aged 2 and 3 using full-time centre-based childcare and earning the average wage; data for New Zealand are from 2018.

Source: OECD calculations based on EU Labour Force Survey; OECD Social and Welfare Statistics (database).

Parental leave policy also drives social norms that ultimately condition labour market participation. The base maternity leave entitlement at 16 weeks with a 100% salary replacement rate is low in international comparison, but paternity leave at six weeks with a 70% replacement rate is even lower, which is likely insufficient to overcome gender norms and earnings shortfalls when the father is the main earner (OECD, 2021[4]). The extra nine weeks with 70% replacement rate that each parent receives since 2022 does not fundamentally alter the gender balance. School hours and out-of-school care are also an important determinant of mothers’ labour supply. In the Netherlands, school hours are short and sometimes unpredictable due to teacher shortages (see above), which can limit parents’ ability to work more hours. Moreover, only one out of four children aged 6-11 attends out-of-school care at least once per week, compared to about one in two in Denmark, Sweden or Luxembourg (OECD, 2019[63]).

The Netherlands should provide stronger paternity leave incentives. Equal sharing of parental leave would shorten the out-of-work time for mothers while lengthening it only a little for fathers, thereby reducing the likelihood of detachment of any parent from the labour market. The July 2020 increase in paternity leave brought Dutch fathers’ entitlement closer to the OECD average, but more could be done. The experience of other OECD countries can help: Japan and Korea provide both mothers and fathers with about one year of non-transferable paid parental leave (even though fathers rarely exercise the option), and Nordic countries reserve parts of the parental leave period for the exclusive use of each parent (OECD, 2019[63]). Another option is to introduce bonus periods, where parents can qualify for extra weeks of paid leave if both use a given amount of shareable leave, as is the case in Germany. The Netherlands could also consider promoting out-of-school care more, to align children’s daily activities on the typical schedule of a full-time worker.

Like childcare, informal long-term care keeps individuals from increasing labour input. In the Netherlands, about ten percent of adults report being involved at least several days a week in caring for disabled or infirm family members, neighbours or friends outside of paid work (Eurocarers, 2021[71]), and more than five million people provide informal care on a less regular basis (SCP, 2022[72]). Moreover, informal long-term care is disproportionately provided by women, which adds to other gender imbalances in unpaid household work and keeps them from fully participating in the labour market.

The Netherlands should maintain its excellent access to publicly subsidised long-term care. The country currently performs very well in terms of both the number of long-term care workers per elderly person (OECD, 2020[73]) and affordability, thanks to generous public social protection benefits (Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal, 2020[74]). However, access to formal long-term care is expected to become increasingly challenging, as labour shortages of long-term care workers are large and projected to increase. In that respect, the consequences of the 2015 long-term care reform should be evaluated. While early assessments suggest that the reform was successful in containing costs in the face of population ageing (SCP, 2018[75]), it also increased budgetary pressure on municipalities and led to layoffs, likely reducing the attractiveness of long-term care jobs (OECD, 2020[73]).

Reducing labour market segmentation to ease transitions between occupations

The co-existence of relatively low regulation of non-standard forms of employment and high regulation of regular contracts can lead to strong, unintended labour market segmentation between highly and weakly protected workers (OECD, 2020[48]). In the Netherlands, excessive segmentation is a long-standing issue (EC, 2022[76]; OECD, 2021[4]; IMF, 2021[77]). A consensus exists among Dutch social partners that a better balance must be struck between flexibility for employers and security for all workers (SER, 2021[32]). The government already attenuated the regulatory gap between permanent and flexible contracts with the 2020 Law on balanced labour markets (Wet arbeidsmarkt in balans) and presented a labour market reform package based on the conclusions of the Commission for the regulation of work (Borstlap Commission, Box 2.6 below), as agreed in the 2021 Coalition Agreement (SZW, 2023[51]).

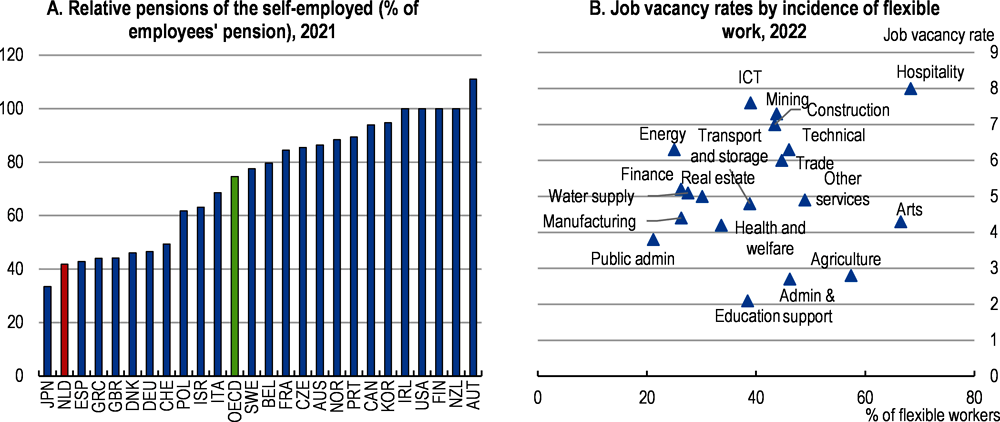

Reforming the labour market is urgent. The current level of segmentation makes the self-employed without employees (zelfstandigen zonder personeel, ZZP) and other categories of flexible workers significantly less well-off in terms of social security benefits (OECD, 2021[78]). For example, the theoretical average pension of the self-employed only amounts to about 40% of that of employees, largely below the OECD average of more than 75% (Figure 2.13, Panel A). Furthermore, severance payments, sickness-related payments or employers’ support for labour market reintegration are limited or inexistent for most flexible workers, such as own-account workers and temporary workers (OECD, 2018[79]). The youth, the low-educated and second-generation immigrants from outside of the European Union are more likely to be in flexible, non-standard forms of employment (OECD, 2018[79]).

Unequal social protection that leaves a large swath of the workforce less well-off likely contributes to labour shortages for some industries in the most flexible segments of the labour market. The hospitality industry is a particularly striking example of high vacancies combined with a high incidence of non-standard forms of employment (Figure 2.13, Panel B). By contrast, the public administration sector has a low share of flexible workers and occupies a segment of the labour market that is comparatively not tight. Important exceptions exist, such as the ICT industry, where labour has been in relatively short supply since before the pandemic despite favourable working conditions.

Figure 2.13. A social security level playing field could improve transitions between occupations

Note: Panel A refers to theoretical pensions accrued to workers with a full career from age 22 in 2018 and contributing the mandatory amount, based on taxable income equal to the average net wage before taxes. Panel B refers to the share of flexible workers, comprising workers on temporary contracts, agency workers, on-call workers and the self-employed without employees (zelfstandigen zonder personeel, ZZP).

Source: OECD (2021) Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators; Statistics Netherlands.

Strong segmentation between regular and non-standard forms of employment reduces labour market mobility and transitions in and out of regular employment. Employers are reluctant to award permanent contracts due to the prohibitively high cost wedge between regular and flexible employment, especially given the advantages of flexibility in some industries, such as hospitality. Excessively stringent employment protection is known to play an important role in restricting the transition to a permanent contract from a temporary one (Bassanini and Garnero, 2013[80]). While reducing labour market segmentation would not directly increase labour supply, it would contribute to the smooth functioning of the labour market by facilitating transitions between occupations and from contracting to expanding businesses, thereby alleviating shortages by preventing labour from being sunk in zombie firms.

The Netherlands should align incentives between contract types and ban regulatory arbitrage whereby de facto employees are defined as own-account workers. Reforms need to ensure that job characteristics, instead of differences in tax treatment and employer responsibility, determine the type of work contract, as recurrently recommended in previous OECD Economic Surveys of the Netherlands (OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2018[26]). Swiftly implementing the recommendations from the Commission for the regulation of work in full would achieve such convergence in a balanced way, by both increasing flexibility of regular employment contracts and reducing tax and social security incentives favouring flexible workers (Box 2.6). The labour market package recently presented by the government intends to deliver on key parts of the Commission’s recommendations, such as reducing the tax wedge between employees and the self-employed without employees (Chapter 1), aligning social security contributions, and giving employers more leeway to adapt tasks, working hours and location given the economic circumstances (SZW, 2023[51]). Furthermore, the ongoing pension reform should mandate pension fund membership for flexible workers, as recommended in the previous Survey (OECD, 2021[4]).

Box 2.6. Borstlap Commission’s main recommendations regarding labour market duality

The 2020 report of the Commission for the regulation of work (commissie regulering van werk, also known as the Borstlap Commission) recommended the following to reduce labour market segmentation.

Increase the flexibility of regular employment contracts

Enable employers to adapt jobs, workplace and working hours of regular employees in line with the demands of the economy.

Introduce part-time redundancy up to a certain percentage of working hours if economic conditions warrant it.

Reduce tax and other incentives for hiring flexible workers

Require firms to provide temporary agency workers, freelance and gig workers the same terms of employment as regular employees, unless proven that they are really self-employed.

Phase out the tax deduction for the permanent self-employed.

Introduce minimum disability insurance coverage for all workers regardless of their contract.

Incentivise employers to hire regular employees by reducing the duration of mandatory sickness pay to one year, from currently two years.

Introduce a higher minimum wage for employees with flexible employment contracts to compensate the additional risk.

Source: OECD (2021[4]) OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2021; OECD (2019[81]) Input to the Netherlands independent commission on the regulation of work (Commissie Regulering van Werk).

High sickness and disability insurance premiums and related obligations for employers also contribute to the cost wedge between regular and flexible employment, and make employers reluctant to offer permanent contracts. The cost to employers of sickness and disability insurance rose significantly following major reforms in the sickness and disability system between 1996 and 2006, which reduced incentives to move workers to disability. These reforms achieved their intended objectives of lowering the overall cost of the system, which was high in international comparison as the scheme had come to function like a long-term benefit programme for less employable workers. However, they failed to fully bring beneficiaries back into the labour force, as a significant share of those who left benefits did not obtain substantive gainful employment (Koning and Lindeboom, 2015[82]). Moreover, the reforms also create incentives to circumvent the schemes by hiring workers with temporary contracts. The labour market reform package recently proposed by the government includes provisions to ease the burden of sickness and disability obligations for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SZW, 2023[51]).

The Netherlands should find a better balance in its sickness and disability system between employer incentives to support the return to work of their sick-listed employees and hiring disincentives. Specifically, it could revise the gate keeping protocol, whereby employers are financially responsible for the first 24 months of their employees’ sick leave, and the experience rating, whereby the insurance premiums paid by employers are linked to the employers’ experience of employees receiving disability. These provide very strong disincentives to offer regular employment, and the available evidence suggests that vulnerable groups with bad health conditions sort into flexible jobs (Koning and Lindeboom, 2015[82]). Instead of employers, public employment services could play a larger role in disability protection through early intervention approaches. For example, Austria and Norway introduced transitional disability programmes towards employment, with a strong focus on vocational rehabilitation and training (OECD, 2022[83]).

Better integrating migrants and facilitating migration for shortage occupations

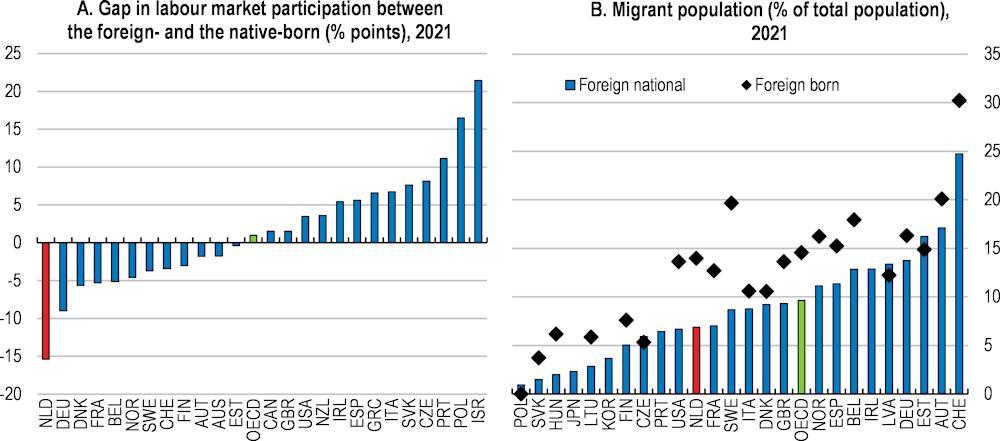

Migrants and people with a migrant background constitute a pool of underutilised labour potential, which could be unlocked to partially tackle labour market shortages in the Netherlands. While labour market participation overall is high, the gap between the native-born and the foreign-born at 15 percentage points in 2021 is the largest in the OECD (Figure 2.14, Panel A). Participation is particularly low for migrants from outside of the European Union (CPB/SCP, 2020[84]): the gap between Dutch nationals and non-EU citizens is larger than 25 percentage points, substantially above the EU average of about 15 percentage points (EC, 2022[76]). The unemployment gap between natives and the foreign-born at 3.8 percentage points in 2021 is also above the OECD average of less than three percentage points (OECD, 2022[85]), and the incidence of long-term unemployment is higher. Better employment outcomes for these underemployed groups would not only reduce income inequality, but also partially address labour shortages. The eight pilot programmes to improve labour market integration focusing on individuals with a migrant background from outside of the European Union (programma verdere integratie op de arbeidsmarkt, VIA) go in the right direction, and their impact should be evaluated.

Figure 2.14. Better use of migration’s potential could prop up the workforce

Note: Panel A refers to the shares of the foreign- and native-born populations aged 15-64.

Source: OECD Migration Statistics (database); OECD (2022) International Migration Outlook 2022.

Adequately targeting active labour market policies is key to ensure that activation increases individuals’ employability and leads to higher participation and employment among underemployed groups, such as foreign-born, in a cost-efficient manner (OECD, 2015[86]). The COVID-19 crisis reinforced the importance of specifically activating vulnerable groups, which have disproportionately transitioned out of employment and into inactivity during the economic contraction induced by lockdowns and other restrictions on activity (OECD, 2021[87]). Moreover, the continuing digital transformation and the changing nature of work tend to increase the risk of transitions out of standard forms of employment and, therefore, the need for job-search support.

The Netherlands should consider expanding skill assessment and statistical profiling tools for activation to specifically target shortage skills among migrant populations. In many OECD countries, public employment services increasingly complement rule- and caseworker-based profiling with statistical models to predict labour market disadvantage and classify job seekers into client groups for activation (Desiere, Langenbucher and Struyven, 2019[88]). In the Netherlands, the Work Profiler model determines how fast jobseekers are invited for a first interview with a caseworker based on risk scores of long-term unemployment. It could be augmented to statistically infer whether migrants are likely to have shortage skills despite not having these qualifications formally recognised. A number of local, bottom-up initiatives aim at expanding skill assessment, but coordination is lacking (OECD, 2023[5]).

Most migrants obtained qualifications abroad but face barriers to unfolding their skill potentials. In the Netherlands, more than half of the highly educated foreign-born either worked in jobs that require a lower level of formal education than what they hold or were not in employment in 2017 (OECD/European Union, 2018[89]). Moreover, those in employment have lower returns to their education in terms of employment prospects and wages than the native-born with similar domestic qualifications, even after accounting for age, gender, field of study and differences in the quality of education systems (OECD/European Union, 2014[90]). Foreign credentials do not have the same signalling effect as domestic qualifications partly due to employers’ lack of information regarding foreign education and training systems (OECD, 2017[91]).

The Netherlands should streamline and accelerate the existing processes of recognition and validation of qualifications acquired abroad for shortage skills. The non-profit organisation in charge of the recognition of qualifying degrees in the Dutch system (Nederlandse organisatie voor internationalisering in onderwijs, NUFFIC) already matches the level of education previously obtained in the country of origin with the Dutch requirements and indicates the amount of additional courses needed to obtain an equivalent professional degree (OECD, 2018[92]). Early detection mechanisms could be fostered to identify individuals whose foreign-acquired skills could be easily supplemented to provide formal qualification in fields where labour shortages are the most acute. Similar mechanisms could be implemented through the framework of the civic integration exam, which also systematically assesses foreign qualifications.

Permanent-type migration to the Netherlands remains moderate in comparison to peer countries (OECD, 2022[93]), suggesting that more immigration can be part of a larger solution to address the structural shortfall in labour supply (Figure 2.14, Panel B). Given existing constraints on housing and public services, any migration policy should consider ensuing additional demand and therefore should be targeted. Dutch migration policies focus on high-skill migrants with the Knowledge Migrant Programme (kennismigrant) based on salary floors, but also under the EU’s Blue Card Directive, and on researchers, intra-corporation transferees and students (Cörvers et al., 2021[94]). These programmes are essential as they contribute to meeting the strong demand in high-skill occupations against the backdrop of digitalisation. However, no policy specifically supports the middle-skill segment of the labour market, despite its key importance for the low-carbon transition (ACVZ, 2019[95]). Current migration pathways for (prospective) medium-skilled workers rely on several schemes, including the regular, employer-sponsored work visa, intra-company transfers, trade in services (so-called mode 4, i.e., presence of natural persons) and secondary or vocational education. Moreover, despite significant streamlining and improvement thanks to the 2013 Modern migration policy reform (Wet modern migratiebeleid), the migration system remains little responsive to the specific needs of the economy (OECD, 2016[96]).

The Netherlands should continue streamlining the immigration system, focusing also on medium-skill migrants, and strengthen its responsiveness to economic needs. Labour market tests, whereby employers are required to search for applicants from the Netherlands or other EU countries before turning to non-EU migrants, should be repealed for structural shortage occupations. Waiving foreign degree recognition for migrants with a job offer could be considered in non-regulated professions. Moreover, the many schemes that constitute the immigration landscape for medium-skill workers need a complete overhaul. An option for incremental reform is to augment the existing Knowledge Migrant Programme to include medium-skill occupations where shortages are significant, with a lower salary requirement to reflect the lower skill wage premium. A more fundamental reform would be a points-based system to grant admission and job search visa depending on criteria such as qualification, experience, age or language skills. Austria, Türkiye and Japan use such systems to grant favourable permit conditions to migrants with a qualifying job offer, and the Netherlands itself uses a similar system to admit foreign entrepreneurs. These systems remain contingent on finding employment within a given time frame, contrary to Australia, Canada and New Zealand’s points-based systems, which grant immediate permanent residence (OECD, 2019[97]). The Netherlands could draw from Germany’s immigration reform geared towards skilled migrants (Box 2.7).

Box 2.7. Migration to tackle shortages in medium-skill occupations: the case of Germany

The 2020 Skilled Workers Immigration Act (Fachkräfteeinwanderungsgesetz) determines access to the German labour market for medium-skilled migrants from non-European Economic Area countries. The act allows migrants to be recruited from abroad for specific occupations, permits migrants with recognised qualifications to search for jobs in specific occupations, facilitates migrants’ access to training and reduces visa processing times.

The Act came into force in March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, making an evaluation of its impact on the German labour market difficult. The Federal Ministry of the Interior issued 30 000 visas over the first year of the policy, but strict criteria for the recognition of skills acquired abroad appear to hamper migration. Many medium-skilled migrants come to Germany under apprenticeship contracts.

The German government is planning an overhaul of the immigration landscape in 2023. A key feature of the prospective reform is the points-based Opportunity Card system (Chancenkarte), which would allow non-EU migrants to enter Germany to look for a job if they meet a combination of criteria including qualifications, age, language skills and work experience. The reform would also waive foreign degree recognition in non-regulated professions, extend the list of occupations that qualify for a residence permit and repeal labour market tests for apprenticeship.

Source: Cörvers et al. (2021[94]) “An exploratory study into the shortages of qualified personnel”; Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community (Germany); OECD (2023[98]) OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2023.

Increasing low-skill labour migration will also be necessary as shortages concern all industries, including those that do not disproportionately rely on high- or medium-skill work. A case in point is the agriculture and horticulture sector, which has long relied on seasonal migrant work and has been facing significant labour shortages since before the pandemic slowed circular migration flows (Ryan, 2023[99]). The long-term care sector is also confronted with growing shortages of relatively low-skill work but has only relied little on immigration so far, as foreign-born workers represent less than 10% of the long-term care workforce in the Netherlands, largely below the OECD average of 25% (OECD, 2020[73]).

The Netherlands should ensure that the immigration system is conducive to both admitting and retaining migrant workers for selected low-skill occupations. If moving to a points-based system, its design should ensure that appropriate weights are given to experience in occupations that face shortages but do not require strong qualifications. Where necessary, vocational language training should be offered. Moreover, public image campaigns can help improve the perception of specific low-skill jobs, such as long-term care work, among prospective migrants. Finally, promoting the integration of low-skill migrant workers into the workforce would ensure a more stable long-term supply of labour to the concerned sectors.

Stepping up lifelong learning to promote growth in expanding industries

More than 43% of the population aged 25 to 64 and about 56% of the population aged 25-34 holds a tertiary degree in the Netherlands (OECD, 2022[58]). Average adult skills are among the highest in the OECD, with the Dutch ranking third in literacy and numeracy, behind Finland and Japan, and third in problem solving in technology-rich environments, behind Sweden and New Zealand (OECD, 2019[100]). Therefore, the Netherlands starts from a solid position to manage the digital and low-carbon transitions. Indeed skills, in particular digital, are essential for workers to adapt to the ever-changing world of work and leverage complementarities with technological innovation, thereby supporting productivity and wage growth (OECD, 2019[54]; OECD, 2021[4]). Dutch people with higher digital skills are 10% more likely to be in employment and have about 5% higher hourly wages (Non, Dinkova and Dahmen, 2021[101]).

But with a very strong demand for specific skills in the Netherlands, especially related to the digital and low-carbon transitions, even a small share of the population with insufficient skills can bring disproportionate skill mismatch and shortages. Almost one in six Dutch adults is a low-performer in either literacy or numeracy, and more than 40% of adults are not sufficiently proficient in problem solving in technology-rich environments (OECD, 2019[100]). Although minimal in comparison to other OECD countries, the incidence of low skills among the Dutch adult population exacerbates labour shortages.

Training needs are important in the Netherlands, given the tight labour market and the massive number of new jobs that will be necessary for the low-carbon transition and the continued digitalisation of the economy (Bakens et al., 2021[102]; TNO, 2021[35]). Reskilling and upskilling are essential to promote worker reallocation towards expanding sectors facing shortages. Estimates from 2019 suggest that half of the Dutch workforce (about 4.5 million people) needs upgraded digital skills; that half a million workers (more than 5% of the workforce) need to change career by 2030; and that the necessary training will cost EUR 6-7 billion per year (DenkWerk, 2019[103]). However, total public spending on training was less than half a billion in 2021 in the Netherlands (OECD, 2022[104]). With the public sector typically accounting for about a quarter of total funding for adult learning (OECD, 2019[105]), this suggests a shortfall in public spending of EUR 1.5-1.75 billion per year. Planned initiatives on lifelong learning to be funded by the National Growth Fund are steps in the right direction.

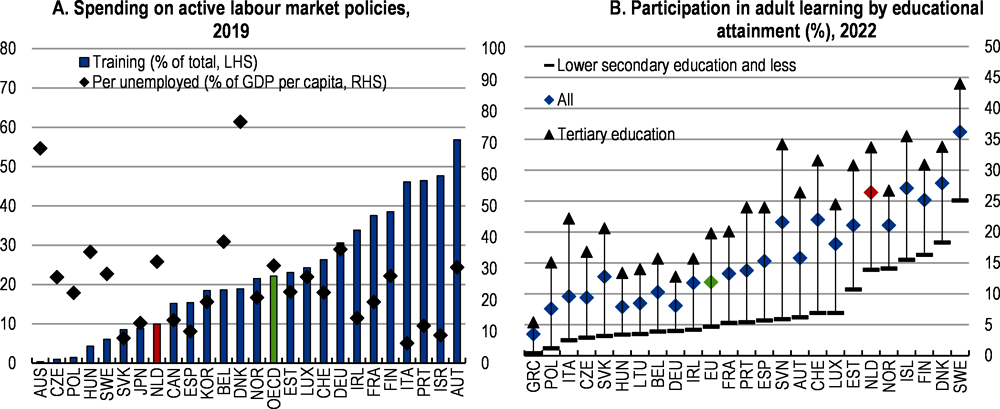

The Netherlands should shift the composition of spending on active labour market policies towards training. Despite being one of the OECD’s top performers in terms of activation spending, the country only allocated about 10% of the total to training in 2019, far less than the OECD average (Figure 2.15, Panel A). In a first approximation, a threefold increase in the share of spending on active labour market policies allocated to training (keeping total spending per unemployed constant) would be necessary to achieve the necessary reskilling and upskilling. The government’s plan to spend an extra EUR 1.2 billion on training between 2022 and 2027 (SZW, 2022[106]), or EUR 200 million a year, is a step in the right direction, but falls far short of estimated needs.

The personal learning and development budget STAP (Stimulering Arbeidsmarkt Positie), implemented in 2022 in replacement of a tax deduction for training expenses and set to expire by the end of 2023, provides a striking illustration of the apparent disconnect between stated objectives and budgeted resources. Under the STAP, people between the age of 18 and statutory retirement are eligible for a training subsidy of up to EUR 1 000 per year, through a registry of approximately 700 approved educational institutions and 20 000 educational activities, both formal and non-formal, with training slots and funding allocated online in real time on a first-come-first-served basis. However, with a EUR 218 million annual budget including implementation costs (SZW, 2022[106]), the scheme can only serve about 200 000 people per year. Major scaling-up and stronger incentives for co-financing by employers are needed to deliver on the stated objective of promoting a new culture of lifelong learning (SER, 2022[107]; OECD, 2017[108]).

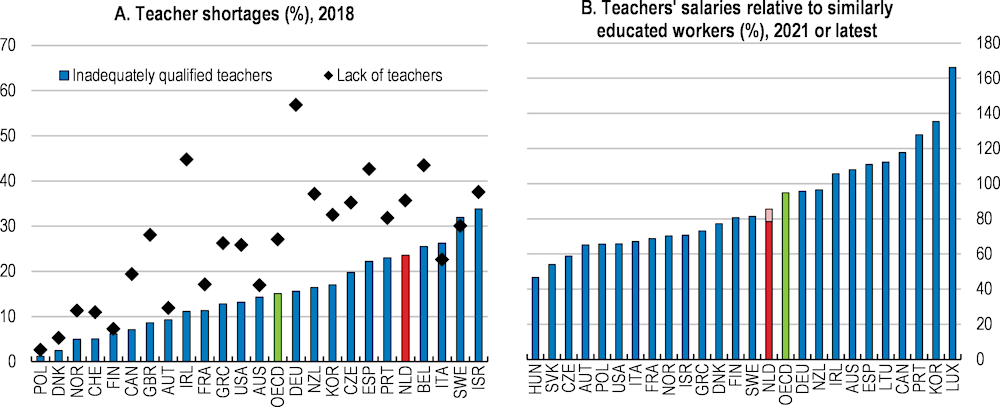

Participation in lifelong learning is very high across the board in the Netherlands (Figure 2.15, Panel B). On average, more than one in four people aged 25-65 have participated in either formal or non-formal education and training in 2022. All groups perform very well in international comparison, including participation at almost 14% for the low-skilled, 18% among the population aged 55-64 and 30% among the unemployed (Eurostat, 2022[109]). However, the participation gaps vis-à-vis prime-age highly educated individuals remain substantial. Closing them would contribute to reducing skill mismatch and, therefore, alleviate labour market tightness.