The Dutch economy recovered quickly from the COVID-19 shock, returning to its pre-pandemic growth path by early 2022. But rising inflation, amplified by rapidly rising global energy prices following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, has been weighing on growth. A healthy fiscal position allowed for temporary support against high energy costs, but support should become more targeted to vulnerable households. Streamlining the tax system would enhance macro-financial stability and productivity by reducing debt bias and distortions in investment and labour supply decisions. Policy reforms to advance the green transition can reduce dependence on fossil fuel energy and the country’s exposure to global energy price fluctuations.

OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2023

1. Key policy insights

Abstract

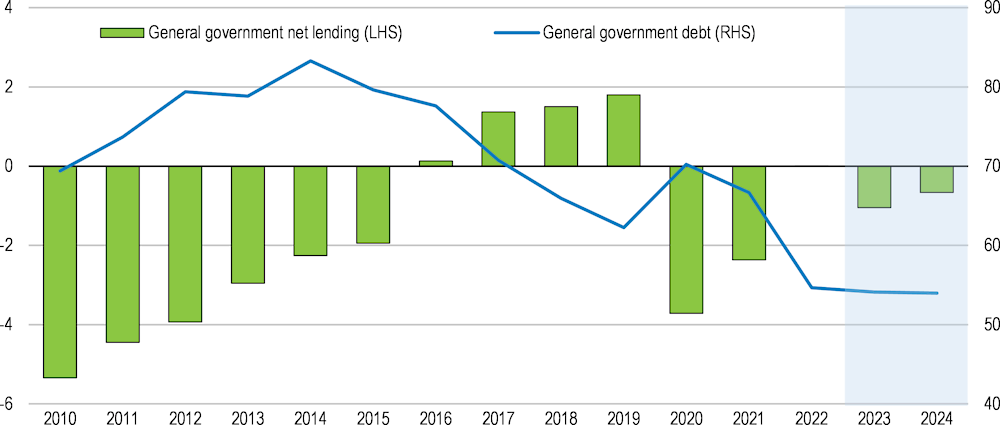

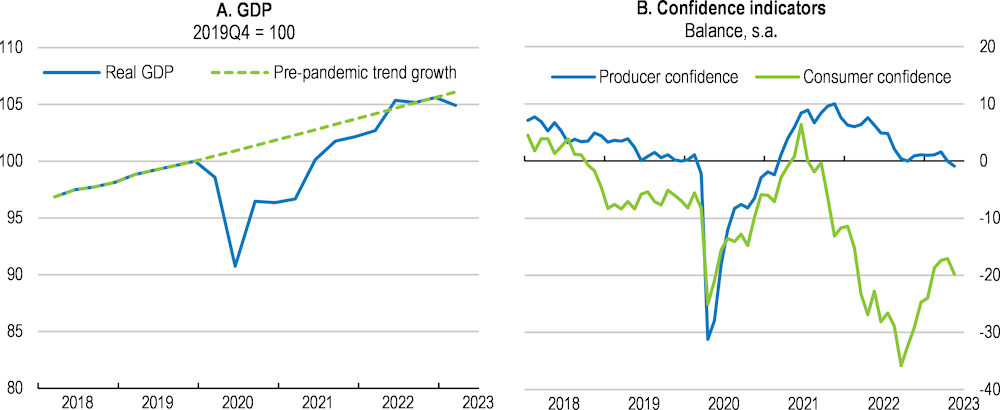

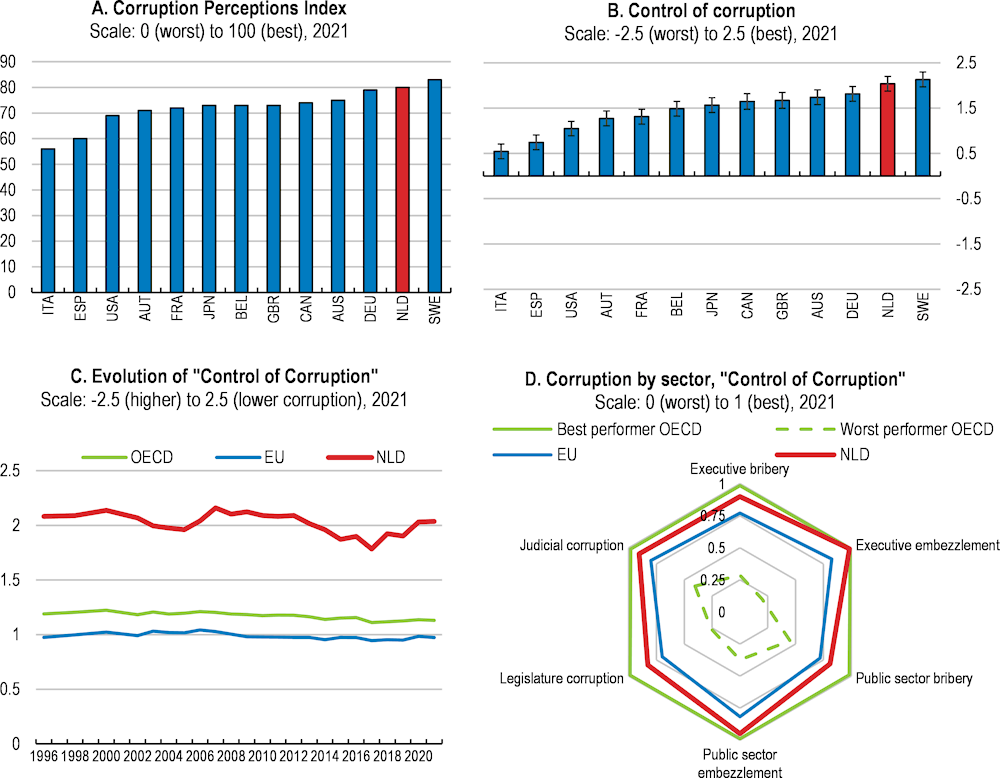

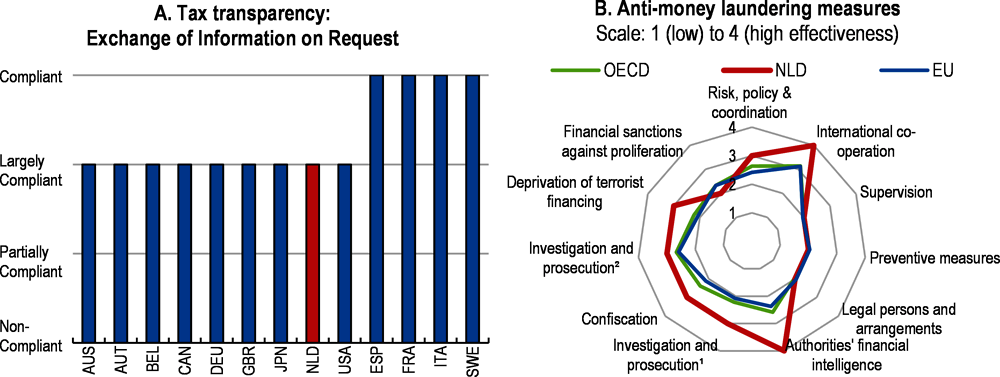

Strong institutions, a high degree of digitalisation and effective support policies secured a vigorous recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, but the impact of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine disrupted this strong economic performance. GDP surpassed its pre-crisis level by mid-2021 – faster than in most OECD economies (Figure 1.1, Panel A). As the global recovery took hold and demand surged, supply shortages led to an increase in inflation from mid-2021 across OECD countries, amplified by soaring energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 (Figure 1.1, Panel B). These new developments have magnified some pre-existing challenges, such as macro-financial vulnerabilities due to high debt levels incentivised by the tax system, a persistent dependence on fossil fuel energy, low productivity growth and an extremely tight labour market.

Figure 1.1. Economic growth remains robust despite high inflation

Note: The Netherlands’ inflation (HICP) is calculated based on the assumption that all energy consumers are on new contracts. This leads to an overestimation of inflation when prices rise sharply and an underestimation when they fall sharply. As from reporting month June 2023, Statistics Netherlands will employ a new method to measure energy prices in the CPI, using transaction data provided by energy suppliers, so that the tariffs paid under long-standing energy contracts can also be taken into account.

Source: OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and OECD Consumer Price Indices (database).

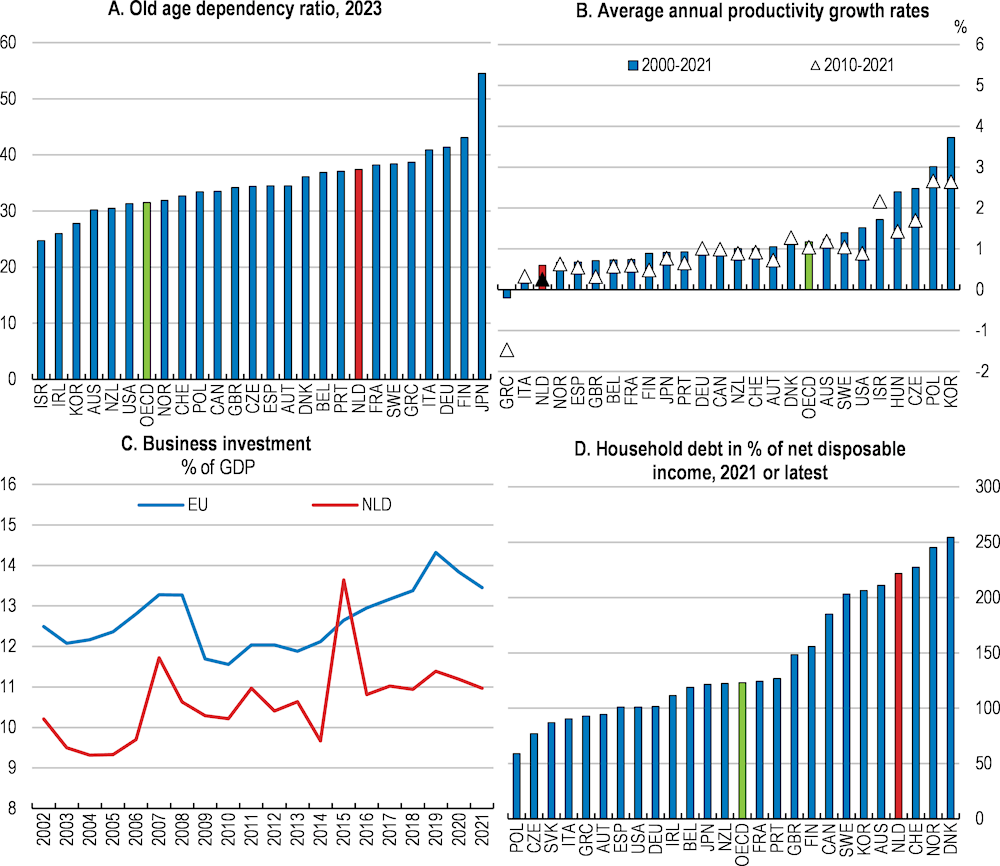

Fiscal prudence up to the COVID-19 crisis created ample space to provide substantial fiscal support during the pandemic, followed by support packages to protect households and firms from rapidly rising energy prices. Still, gross public debt, at 55% of GDP in 2022, is low in international comparison. Fiscal support to protect the most vulnerable households is warranted, but should not work at cross-purpose with monetary policy to tackle high inflation. The current energy price cap is not well targeted and thereby comes at a risk of high fiscal costs, stimulating demand while also reducing incentives for energy savings. An ageing population (Figure 1.2, Panel A) in combination with an already tight labour market will increase fiscal pressure going forward, both through higher ageing-related spending and lower revenues.

Rapid population ageing aggravates skill shortages and labour market tightness, calling for a more efficient use of resources to maintain economic growth. The labour market is very tight despite high employment, due to low hours worked and significant skill mismatch. Productivity growth has been sluggish over the past decade and is lower than in many other advanced OECD economies, largely driven by lower private investment (Figure 1.2, Panels B and C). While public investment was boosted through the launch of the National Growth Fund in 2021, the Dutch tax system distorts private investment and labour supply decisions, with negative consequences for productivity growth. Tax subsidised housing debt contributes to high household debt in the Netherlands, which is at 222% of net disposable income among the highest in the OECD (Figure 1.2, Panel D). Not only do high debt levels increase macro-financial vulnerabilities as interest rates rise, but tax-induced incentive to finance certain assets may bind capital that would otherwise be available for more productive investments. The tax system is also skewed towards non-standard employment, which has increased over the past years and may weigh on productivity in the longer term by lowering the uprating of skills.

Figure 1.2. An ageing population meets low productivity growth and low investment

Note: Panel A shows the old-age to working-age demographic ratio which is defined as the number of individuals aged 65 and over per 100 people of working age defined as those aged 20 to 64. The evolution of old-age to working-age ratios depends on mortality rates, fertility rates and migration. In panel B, labour productivity is measured as GDP per hour worked at constant prices, USD purchasing power parities. Panel C depicts gross fixed capital formation expressed as a percentage of GDP for the business sector. The spike in 2015 is due to a EUR 22 billion R&D purchase by a Dutch multinational enterprise.

Source: OECD (2021), Pensions at a Glance 2021; OECD (2023), Productivity database; OECD (2023), Economic Outlook: Projections and Statistics Database; Eurostat; and OECD (2023) National accounts at a glance database.

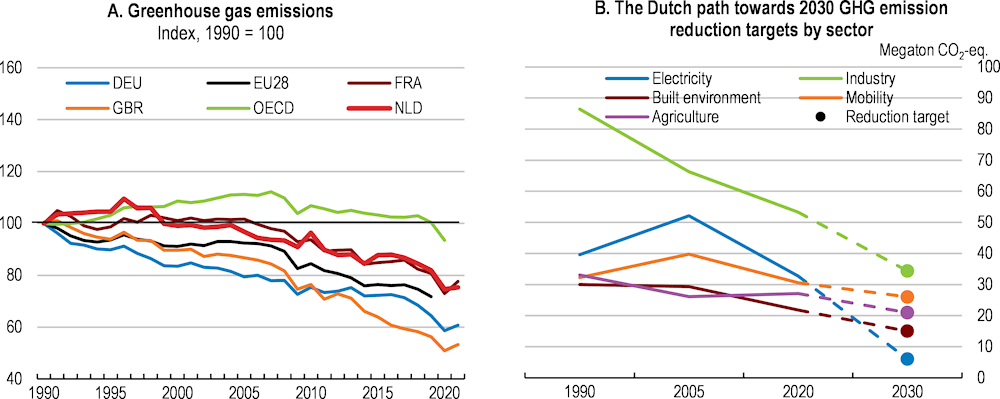

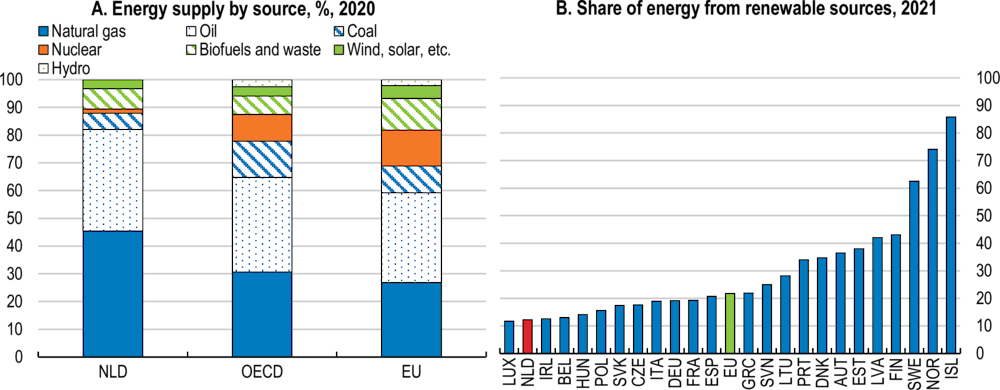

The energy crisis highlighted the importance of reducing the country’s strong reliance on fossil fuels and advancing the green transition is a key policy priority for the government. Since 1990, the Netherlands has reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 25% and the government has put forward the legally binding target to cut emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Policies mainly focus on increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix and reducing emissions in the industry sector. However, implemented policies are not yet sufficient to meet the 2030 target. Advancing the green transition also faces bottlenecks in terms of physical capacity and skill shortages.

Against this background, the main policy messages of this Survey are:

Fiscal support to protect households against high energy prices is not well targeted and thereby comes at a risk of an unduly high fiscal cost and at the expense of climate objectives. A longer-term fiscal strategy is needed to alleviate fiscal pressures from ageing-related spending and rising interest rates.

A holistic long-term strategy for reaching net zero by 2050 is needed, including carbon pricing, regulation, innovation and skills policies across sectors. Detailing pathways beyond 2030 could avoid trade-offs between measures favouring short-term success and efficient longer-term solutions.

Tackling the tight labour market requires implementing a comprehensive policy package to increase the labour market integration of women, elderly, and low-skilled workers, and expand adult learning opportunities.

The economy is slowing amidst high price pressures

Economic growth started to slow following a quick recovery from the pandemic

After a strong rebound from the COVID-19 recession, economic growth in the Netherlands has started to slow. Although the COVID-19 pandemic led to a contraction of 3.9% in 2020, GDP quickly recovered to pre-pandemic levels by mid-2021 and resumed its pre-pandemic growth path by early 2022 (Figure 1.3, Panel A). GDP growth in 2022 continued to be strong at 4.5%, although the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 disrupted the Dutch economy. GDP growth started to slow from mid-2022 on the back of high inflation, lower investment and a weakening trade balance. In the first quarter of 2023, GDP contracted by 0.7% as exports dwindled and gas inventories declined due to lower domestic gas production and colder weather, among other factors. Private investments contributed positively to growth, but producer sentiment remained subdued. Private consumption stalled in the first quarter of 2023, and consumer confidence remained fragile (Figure 1.3, Panel B).

Figure 1.3. GDP has recovered, but confidence remains low

Note: In panel A, the pre-pandemic trend growth is calculated as the average growth between 2018 and 2020Q1, and is projected from 2020Q2 onwards. In panel B, production confidence refers to confidence of the manufacturing industry.

Source: OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); OECD (2023), OECD Main Economic Indicators (database).

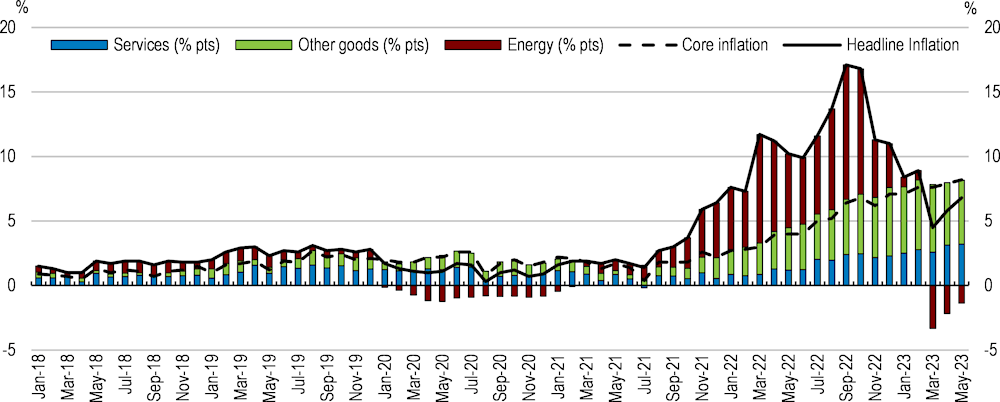

Headline consumer price inflation has risen sharply from mid-2021, peaking at 17.1% in September 2022 before slowing to 6.8% in May 2023 (Figure 1.4). The early rise in inflation was largely driven by global supply chain disruptions, higher transport costs and a sharp increase in global commodity prices. The sharp rise in prices of raw material and energy in late 2021 was modest, however, compared to the explosive price increases of natural gas, oil, food and commodities since the start of the war in Ukraine. In recent years, only 3-4% of the Netherlands’ energy consumption was imported from Russia, thus direct exposure to sanctions on Russia’s oil and gas is limited. But the Netherlands is a net-importer of gas and therefore vulnerable to spill over effects from rising global energy prices. High energy prices have been the initial driver of inflation, but prices of other goods and services have picked up as well. Core inflation rose to 8.2% in May 2023, up from 2.7% at the beginning of 2022 as higher prices for energy, commodities and transport fed into prices of goods and services (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Inflation has peaked but remains high as core inflation continues to rise

Year-on-year growth in the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP)

Note: The Netherlands’ inflation (HICP) is calculated based on the assumption that all energy consumers are on new contracts. This leads to an overestimation of inflation when prices rise sharply and an underestimation when they fall sharply. As from reporting month June 2023, Statistics Netherlands will employ a new method to measure energy prices in the CPI, using transaction data provided by energy suppliers, so that the tariffs paid under long-standing energy contracts can also be taken into account.

Source: Statistics Netherlands (CBS).

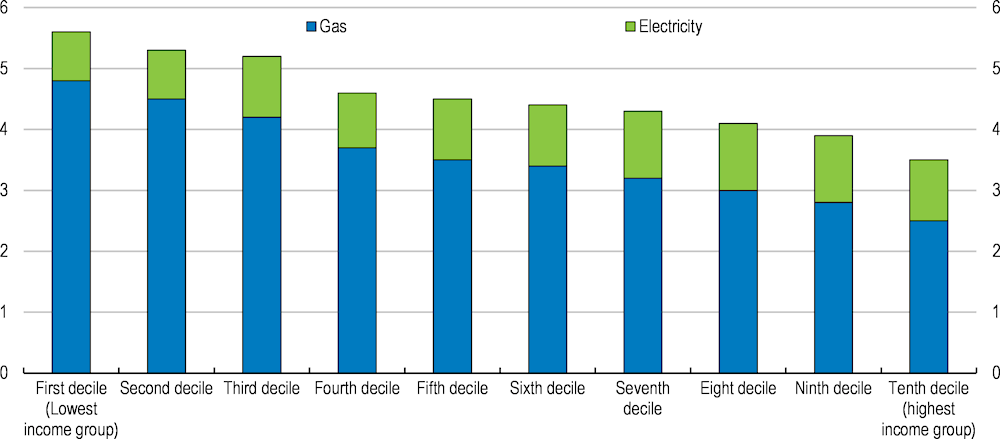

Rapidly rising energy prices triggered a new wave of fiscal support to businesses and households (Box 1.1). To help energy-intensive small and medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), the government introduced the Energy Cost Contribution Scheme (Tegemoetkoming Energiekosten-regeling) for the period from November 2022 to December 2023. The government also supports small energy consumers such as households, the self-employed, shops, associations, small social organisations and some of the small SMEs through an energy price cap up to a maximum consumption threshold put in place from January to December 2023. As rising energy prices disproportionally affect lower-income households who spend a relatively large part of their income on energy (Figure 1.5) and often have a smaller financial buffer to absorb large increases in the cost of living, the support measures are welcome. However, in the context of high inflation, fiscal measures that provide additional demand stimulus should be avoided. Untargeted measures such as the cut in excise duty on petrol and diesel should be phased out. Moreover, the energy price cap should maintain energy saving incentives and remain a temporary solution, targeted towards vulnerable households and be complemented by a structural approach to aid households with higher energy costs, for example through energy savings measures. To ensure an efficiently functioning energy and electricity market, it is important that energy support measures remain temporary.

Box 1.1. Fiscal support to help households in the cost-of-living crisis

Support to cope with high energy prices:

In 2022

A temporary VAT reduction on energy (natural gas, electricity, and district heating) from 21% to 9% from July to December 2022.

A cut in excise duty on petrol and diesel by 21% from April 2022 to July 2023.

A one-off energy allowance of EUR 1300 for people with an income around the social assistance level.

The government brought forward spending of EUR 150 million, originally earmarked for 2026, to help low-income households take energy-saving measures.

EUR 190 discount on households’ energy bills both in November and in December.

A decrease of the energy tax on electricity of 8 ct/kWh, and an increase of the energy tax credit, from EUR 560 to EUR 790.

In 2023

A price cap on energy bills from January to December 2023. For gas the maximum rate will be EUR 1.45 per cubic metre up to a consumption of 1 200 cubic metres. For electricity the maximum rate will be lowered to EUR 0.40 per kWh with a maximum consumption of 2 900 kWh. For all usage that exceeds these thresholds, the rates for small consumers remain as is stated in their energy contract.

A one-off energy allowance of EUR 1 300 for people with an income around the social assistance level.

VAT on solar panels is cut to 0% without an end period so far.

Other measures to aid with high cost of living effective from January 2023

The minimum wage was raised by 10.15%, to EUR 1934.40 gross per month. Related benefits, including the state pension under the National Old Age Pensions Act (Algemene Ouderdomswet) and the unemployment benefit under the Unemployment Insurance Act (Werkloosheidswet), went up by the same percentage.

Housing, healthcare and child benefits also increased. These measures will support purchasing power for the average family, which is set to decrease 0.2% in 2023, following a decline of 2.7% in 2022.

In the income tax system, the rate in the first tax bracket has been reduced from 37.07% to 36.93%. The annual income ceiling for this rate has been raised from EUR 69 398 to EUR 73 031. The maximum labour tax credit was increased by EUR 523 to EUR 5 052.

The extra spending will be partly paid for by an extra ‘contribution’ from oil and gas companies as well as a higher corporate income tax rate and an increase in the tax rate on income from savings and investment.

Figure 1.5. Lower-income households are more affected by higher energy prices

% of disposable income spent on energy, 2020

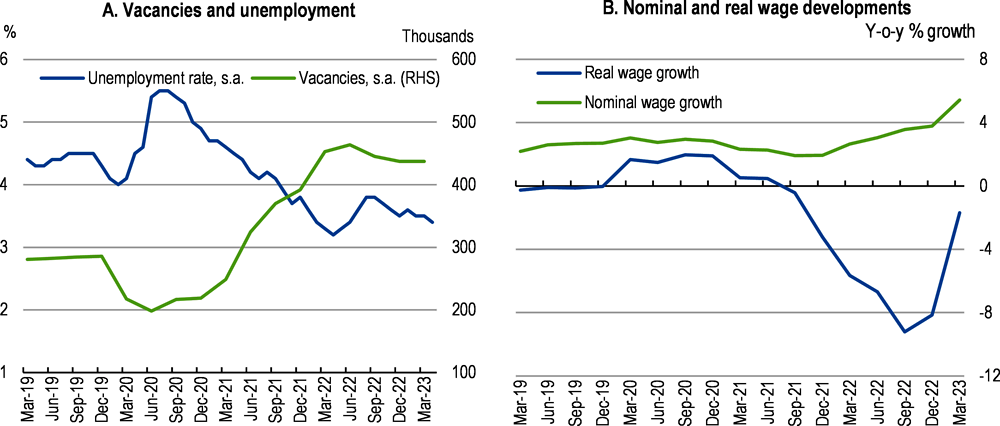

Figure 1.6. The labour market remains tight

Source: Statistics Netherlands (CBS); and OECD (2023), OECD Consumer Price Indices (database).

A tight labour market has not yet translated into significant domestic price pressures. Already prior to the pandemic, the labour market was tight, but since the end of 2019, the ratio of job vacancies per 100 unemployed increased from 0.7 to 1.2 by the first quarter of 2023 (Figure 1.6, Panel A). As highlighted in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]), the first COVID-19 lockdown resulted in higher inactivity and unemployment, but the labour market recovered strongly thereafter. The unemployment rate declined to a two-decade low of 3.3% in the second quarter of 2022 before picking up to 3.5% in the first quarter of 2023. The employment rate recovered as well, surpassing the pre-pandemic rate of 80.1% by the third quarter of 2021, and reached 82.1% at the beginning of 2023. Staff shortages are being felt across the economy (see Chapter 2) and collectively negotiated wages rose by 5.4% in the first quarter of 2023 compared to a year earlier, the largest increase over the past decade. Yet, nominal wages have lagged consumer prices and although improving, leading to a decline of 1.7% in real terms in the first quarter of 2023 (Figure 1.6, Panel B). Similarly, the Dutch national minimum wage has fallen in real terms over the course of 2022, and at 46% of the median wage was already below that of most OECD countries before the crisis (OECD, 2023[5]; OECD, 2022[6]).Therefore second-round effects on inflation are expected to be limited from the 10.2% increase in the minimum wage in January 2023.

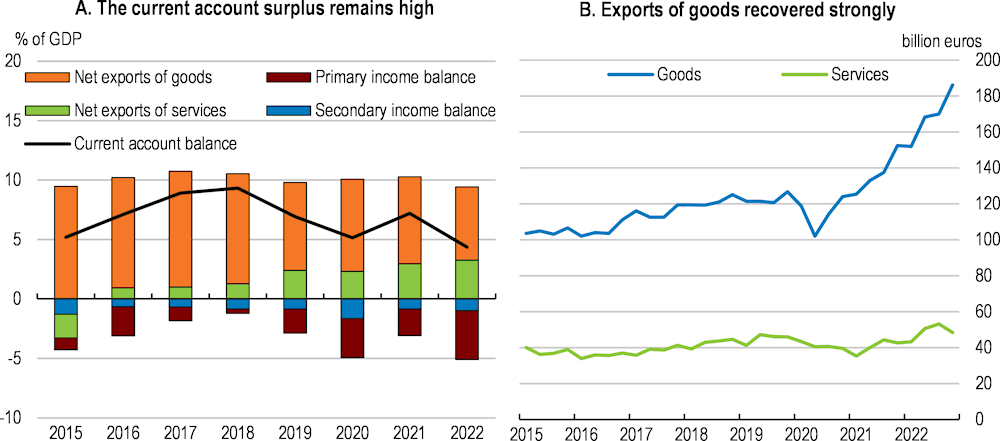

As a small and very open economy, the Netherlands is sensitive to global developments. The current account surplus remains strong, albeit declining to 4.4% of GDP in 2022 (Figure 1.7, Panel A). The strong current account reflects persistently higher saving than investment of corporations residing in the Netherlands. High saving on the part of non-financial corporations is mainly high foreign investment of multinationals in the form of retained earnings as reflected by a positive financial and capital account. In 2022, the capital account surplus was exceptionally high, at 11% of GDP, largely driven by the sale of intellectual property by a Dutch business unit of a foreign multinational to a foreign unit of the same multinational. The current account surplus also reflects the Netherlands’ strong export performance (DNB, 2022[7]). Exports of goods recovered quickly following global production disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis, surpassing pre-crisis levels by early 2021 (Figure 1.7, Panel B). Exports of services were more severely affected by recurring lockdowns and travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and only started to recover to pre-pandemic levels by mid-2022 (Figure 1.7, Panel B).

Figure 1.7. The current account surplus is driven by net exports

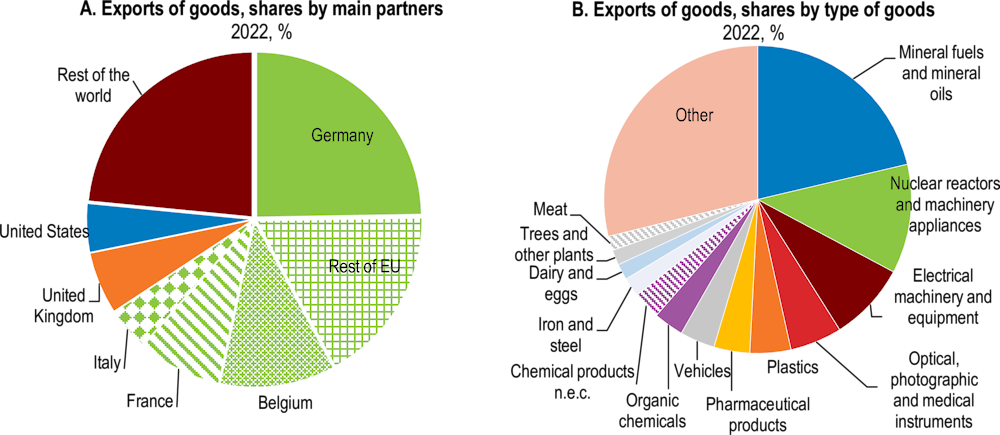

The Dutch economy has important trade linkages within the European Union. In 2022, Germany, Belgium and France were the largest export destinations for the Netherlands (Figure 1.8, Panel A). More than a third of imports in 2022 came from Germany, Belgium and China. Imports from China are increasingly important in Dutch supply chains. Imported Chinese goods are used throughout the economy, with the manufacturing sector and the construction sector leading in using imported goods from China in their production processes (CPB and Statistics Netherlands, 2022[8]). While increasing trade with China brings the benefit of a larger and more diverse product supply at lower prices, it also comes with greater dependence and risks of supply chain disruptions as seen during the pandemic. In particular for sectors relevant for exports, such as manufacturing of machinery and electrical equipment (Figure 1.8, Panel B), supply disruptions could severely affect growth. The Netherlands has only limited direct trade linkages with Russia and Ukraine, but is exposed to disruptions to the supply of commodities and materials from this region, as well as to logistics and transport blockages. Continuing disruptions to global supply chains, sanctions and surging commodity prices are weighing on world trade. As such, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has implications for the Dutch economy not only through high energy prices and increased uncertainty, but also through depressed growth of world trade.

Figure 1.8. Exports of goods by trading partner and type of goods

Economic growth is expected to moderate

GDP is expected to slow to 0.9% in 2023 and to pick up to 1.4% in 2024 (Table 1.1). Growth in 2023 is supported by private consumption, aided by the purchasing power package that came into effect at the beginning of 2023. Slowing private residential and non-residential investments weigh on growth over the projection horizon amidst uncertainty, rising interest rates and credit tightening. Headline inflation is expected to fall further due to lower energy prices, but core inflation is likely to remain elevated until 2024. Wages react to inflation with a time lag and are projected to rise by 5.3% in 2023 and by 4.9% in 2024. The unemployment rate will gradually rise to 4.1% by the second half of 2024.

The outlook is surrounded by several risks, including a severe 2023/24 winter with higher-than-expected energy prices, and increasing macro-financial vulnerabilities as rapidly rising interest rates could increase the risk of financial contagion through the global financial system (Table 1.2). Bankruptcies, which are still below the pre-pandemic level, could rise significantly due to the increasing pressure on businesses from higher interest rates, labour costs and uncertainty. A faster return of inflation to the target than expected could allow central banks to loosen monetary policy, stimulating domestic demand.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices)

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (EUR billion) |

||||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

812.9 |

-3.9 |

4.9 |

4.5 |

0.9 |

1.4 |

|

Private consumption |

353.5 |

-6.4 |

3.6 |

6.5 |

1.7 |

0.7 |

|

Government consumption |

200.1 |

1.5 |

5.2 |

1.6 |

2.8 |

1.4 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

172.9 |

-2.6 |

3.2 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

0.0 |

|

Housing |

41.1 |

-0.6 |

3.2 |

0.6 |

4.0 |

-1.4 |

|

Business |

104.1 |

-5.3 |

4.8 |

5.2 |

0.4 |

-0.9 |

|

Government |

27.6 |

4.4 |

-2.0 |

-4.4 |

2.1 |

5.7 |

|

Final domestic demand |

726.5 |

-3.3 |

4.0 |

4.1 |

2.1 |

0.7 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

6.9 |

-0.8 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

-1.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

733.3 |

-4.2 |

3.9 |

4.1 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

670.7 |

-4.4 |

5.2 |

4.7 |

1.0 |

2.8 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

591.1 |

-4.8 |

4.0 |

4.2 |

1.1 |

2.1 |

|

Net exports1 |

79.6 |

-0.1 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

0.8 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|

|||||

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

2.2 |

2.3 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

1.4 |

|

Output gap2 |

. . |

-4.6 |

-2.2 |

0.3 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

|

Employment |

. . |

0.0 |

1.5 |

3.2 |

1.9 |

0.4 |

|

Unemployment rate |

. . |

4.9 |

4.2 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

1.9 |

2.4 |

5.3 |

5.6 |

2.0 |

|

Consumer price index (harmonised) |

. . |

1.1 |

2.8 |

11.6 |

3.2 |

2.2 |

|

Core consumer prices (harmonised) |

. . |

1.9 |

1.8 |

4.8 |

6.8 |

3.9 |

|

Household saving ratio, net3 |

. . |

18.8 |

17.6 |

12.7 |

10.7 |

13.2 |

|

Current account balance4 |

. . |

5.1 |

7.3 |

4.4 |

5.3 |

6.0 |

|

General government fiscal balance4 |

. . |

-3.7 |

-2.4 |

0.0 |

-1.0 |

-0.7 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance2 |

. . |

-0.7 |

-1.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.9 |

-0.5 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance2 |

. . |

-0.3 |

-0.6 |

0.2 |

-0.5 |

0.1 |

|

General government gross debt4 |

|

70.2 |

66.7 |

54.7 |

54.1 |

54.0 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht)4 |

. . |

54.7 |

52.5 |

51.0 |

50.5 |

50.3 |

|

General government net debt4 |

. . |

35.0 |

33.1 |

25.6 |

25.1 |

24.9 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

0.3 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. As a percentage of household disposable income.

4. As a percentage of GDP.

Source: OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Table 1.2. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Uncertainty |

Possible outcome |

|---|---|

|

A more virulent COVID resurgence or another pandemic. |

New containment measures could constrain consumption, leading to firm failures and increased unemployment. Disrupted supply chains would hurt production, while depressed global demand would weigh on trade. |

|

Large-scale cyber-attacks. |

A cyber-attack could disrupt business operations or shut down domestic infrastructure vital for the functioning of the economy. |

|

High and persistent inflation in the euro area requiring steep monetary tightening. Rapidly rising interest rates could increase the risk of financial contagion through the global financial system. |

High mortgage rates could lead to falling housing prices, reducing mortgage values, which together with falling real incomes could raise loan defaults and expose vulnerabilities in the financial system. Financial contagion could lead to insufficient liquidity of banks, insurers and pension funds that could affect the domestic market. |

|

Geopolitical tensions decrease. |

Confidence could recover spurring investment and private consumption. Energy prices could decrease faster than expected, lowering inflationary pressures, and allowing central banks to loosen monetary policy, which would stimulate domestic demand. |

Macro-financial vulnerabilities have increased

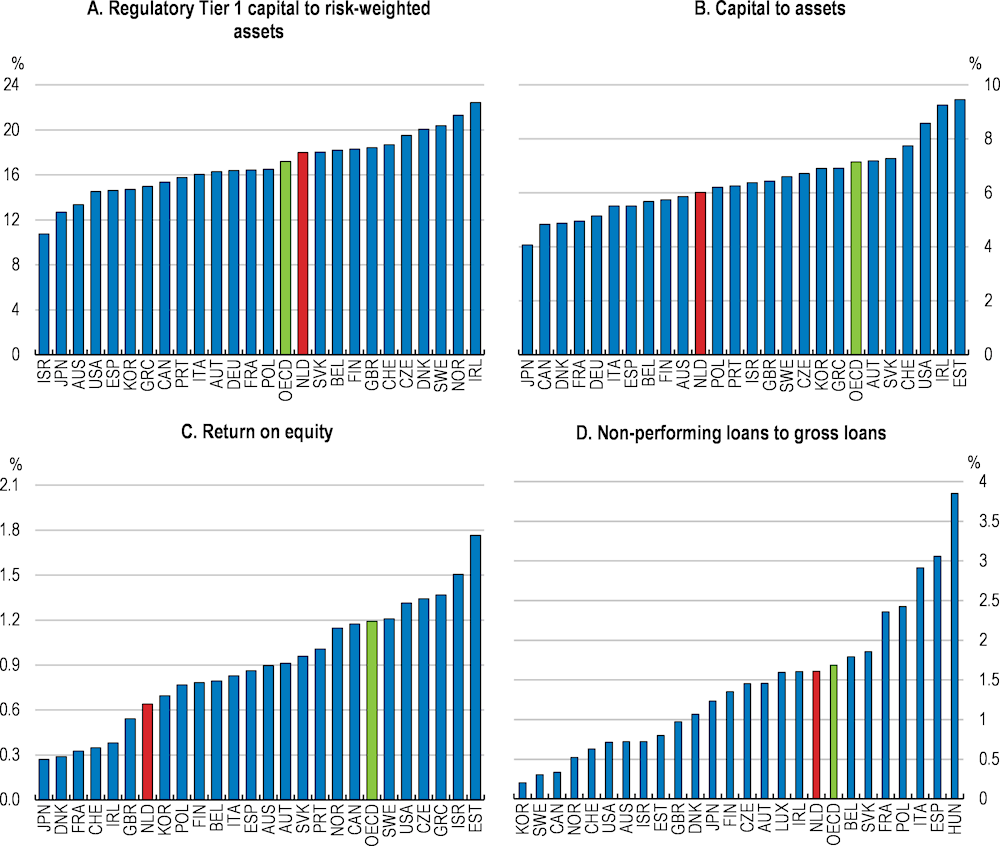

The Dutch financial sector has been stable and resilient, maintaining capitalisation and liquidity positions well above the statutory minimum requirements. While banks are still highly leveraged in gross terms, the risk weighted capital ratio is well above the OECD average (Figure 1.9, Panels A and B) and even increased during the COVID-19 crisis from 16.9% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 18% in the fourth quarter of 2022. During the COVID-19 crisis, the Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) and the European Central Bank (ECB) allowed banks to use capital buffers to keep lending to firms and households in order to prevent the economic crisis from spreading to the financial sector. The DNB decided to replace systemic buffers with a gradual build-up of the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) and raised the CCyB from 1% in May 2022 to 2% in May 2023. Banks will have to comply with this requirement by May 2024, provided there is no substantial change in the risk assessment. This development is welcome as the combination of high inflation, rising interest rates and slowing economic growth is putting the financial sector to the test once again, as recently shown by the collapse of some regional banks in the United States and its effect on global stock markets. Rising interest rates can ease the long-standing pressure on banks’ profitability (Figure 1.9, Panel C) through higher interest income, but may lead to losses from their fixed income trading portfolio as rising interest rates are resulting in declining bond prices. In addition, an increase in non-performing loans may occur, although so far, their share remains low (Figure 1.9, Panel D). A recent stress test by the DNB (2022[9]) based on prolonged high inflation and a further rise in interest rates suggests that the positive impact of high interest rates is more than offset by rising credit losses and an increase in credit risks. Even so, banks are expected to be able to absorb the losses based on their good starting position.

Vulnerabilities that have accumulated over a protracted period of low interest rates are now surfacing. Favoured by a tax system that subsidises debt financed housing (see below), households have high mortgage debt on average and may face difficulties to meet their mortgage obligations if high inflation continues to reduce real incomes. In particular, recent first-time buyers borrowed large sums relative to their income, as house prices have seen a steep rise over the last years (Figure 1.10, Panel A). Although the maximum loan-to-value ratio on new mortgages has been lowered to 100% since the Global Financial Crisis, the debt-to-income ratio has steadily increased in recent years. Around 60% of households under the age of 36, and 45% of older households have a debt-to-income ratio above 450% (DNB, 2022[9]). Continuing to lower the maximum loan-to-value ratio to 90% could support financial stability in the longer term. As the share of fixed rate loans is high, with about 75% of outstanding mortgage debt in 2022 bearing an interest rate that was fixed for more than five years, the recent rise in mortgage rates is not likely to lead to significant losses in banks’ mortgage portfolio in the short term, but could have indirect effects through decreasing housing prices (DNB, 2022[9]).

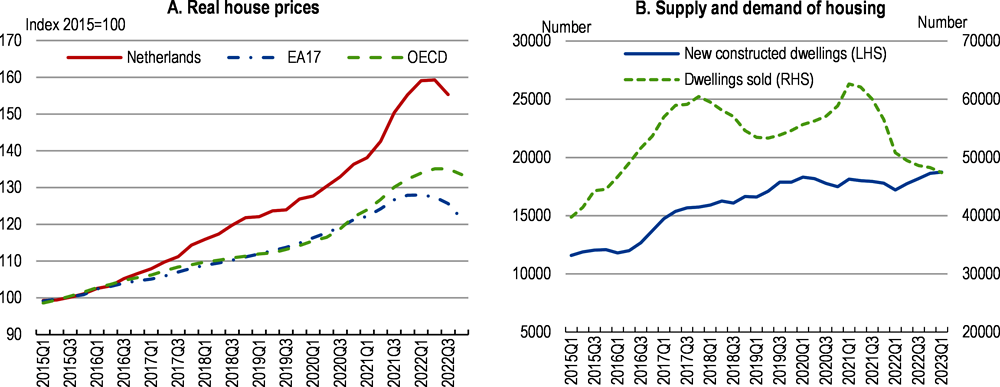

The housing market shows signs of cooling, as selling prices started to fall from August 2022. Real house prices dropped almost 2% on average in the third quarter of 2022, compared to the second quarter, the steepest drop in more than eight years. Still, house prices are significantly above the OECD and euro area average (Figure 1.10, Panel A), driven by high demand stimulated through tax advantages for home ownership (see below) that meets a housing supply shortage. As discussed in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]), housing supply has not kept pace with demand since the Global Financial Crisis, partially due to slow planning procedures. More recently, the availability and prices of construction materials and labour as well as the nitrogen problem (Box 1.2) are significant obstacles for the government to meet its ambition to add 100 000 new dwellings to the housing stock per year until 2026-27. Even though supply is limited, the rise in house prices started to slow from mid-2022 as demand declined (Figure 1.10, Panel B) on the back of rising mortgage rates. The developments in the housing market should be closely followed and banks should be prepared to absorb the impact of price corrections in the housing market. Against this backdrop, the DNB introduced a requirement on 1 January 2022 for banks to hold a certain minimum of capital for their mortgage portfolio for at least two years.

Figure 1.9. Financial stability indicators are in the mid-range of other OECD countries

2022Q4 or latest quarter

Despite recent developments, the government’s overarching ambition to increase affordability for first-time buyers is likely to come under additional pressure, as the rise in interest rates outpaces the restraining effect on house prices. Even though the Netherlands records a large share of renters, which at 40% is nearly double the OECD average, these renters are living in social rental housing as the private rental market is small. Affordable alternatives in the rental market are limited (OECD, 2022[10]), due to a considerable tax-favoured owner-occupied housing stock and rent controls for housing defined as social housing. Households with limited savings and limited ability to obtain a sufficient mortgage and that do not qualify for social housing are left with limited housing options. Plans to tighten rental controls to also cover the mid-market segment are motivated by the need to provide affordable housing, but also lower incentives for investors. To balance the housing market and increase the size of the private rental market, the government should re-evaluate the large role attributed to rent controls and closely monitor developments on the housing market in response to the tightening of rental controls. The government should develop a medium-term strategy to gradually limit rent controls to a narrower part of the market as stressed in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]). Such a strategy should be gradually phased in to create a better balance between supply of and demand for housing and make rental housing available to people when and where they need it. First steps in a coherent housing reform package should include reducing the favourable tax treatment of owner-occupied housing to create room for private rental investments, and speeding up planning procedures to boost housing supply. These two reforms would contribute to increased supply and lower price pressures on existing housing and market rents, and could therefore lead to a situation where rent controls, at least on the mid-market segment, are no longer necessary.

Figure 1.10. House prices are falling

Note: In panel B, a four-quarter moving average is applied to the series of dwellings sold and new constructed dwellings.

Source: OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); CBS (2023), House Prices: new and existing dwellings price index (database), CBS (2023), Dwellings and non-residential stock; changes, utility function, regions (database).

Rising interest rates can increase profitability for insurers and improve the financial position of pension funds, but also gives rise to new risks. As highlighted in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]), pension funds’ funding ratios had been under pressure from low interest rates for a long time. Rising interest rates since the beginning of 2022 improved the funding ratio, but also increased the margin requirements under derivative contracts. In the first half of 2022, Dutch pension funds sold a record EUR 88 billion worth of assets, approximately 4.6% of pension funds’ total invested assets, of which EUR 82 billion were used to fund margin calls (DNB, 2022[9]). While a gradual rise in interest rates does not pose a liquidity risk, a rapid rise in interest rates may require the realisation of investment within a short period, causing liquidity risks with a potential market impact. Non-banking housing finance in the Netherlands is higher than on average in the European Union, and thus Dutch insurance companies and pension funds are exposed to price corrections on the housing market and rising NPLs on the back of rising interest rates (OECD, 2021[11]). It should be monitored that investments of pension funds and insurances are sufficiently diversified to accommodate market corrections accompanied by high financial market volatility.

Box 1.2. The Dutch nitrogen problem

As highlighted in the previous Economic Survey (2021[4]), excessive nitrogen deposits in natural preservation areas in the Netherlands are not only polluting nature, air, soil and water, but also limit the available nitrogen space for new developments, slowing down new investment projects due to unclarities in the permitting procedure for nitrogen emitting projects. Without policy action, moving forward with much-needed building activities in the Netherlands is severely hampered.

Background

In the Netherlands, nitrogen pollution mainly derives from two main sources – burning fossil fuels for energy or transport (nitrogen oxides), and from the manure created by the livestock farming industry (ammonia and nitrous oxide). The Netherlands has 162 Natura 2000 areas, which are special preservation zones covering about 15% of the country and protected by the European Habitat Directive. Of these areas, 129 are sensitive to nitrogen and 118 exceeded the critical limits for nitrogen in 2018. In May 2019, the Council of State ruled that the existing policy framework at that time (PAS) did not provide the required assurance that the nitrogen deposition would not affect the natural features of the Natura 2000 sites, and was therefore in conflict with EU law. The Council of State also found that many of the programme's measures were necessary as a minimum requirement to fulfil the goals set out in the Habitats Directive, and therefore could not be used to offset emissions from new activities causing nitrogen deposition on the Natura 2000 sites. As a result of the ruling, projects have been postponed or cancelled as the necessary evaluation whether the emissions of a project could potentially harm a Natura 2000 area has to be done on a case-by-case basis and often require additional mitigating measures to offset the potential damage of the project.

A special committee, the Remkes Commission, advised the government to take several steps to reduce nitrogen emissions and deposits. Several short-term solutions were implemented in 2020, such as reducing maximum speed limits during daytime from 130km/h to 100km/h, and buy-out schemes for farmers near Natura 2000 areas. Long-term solutions are outlined in the 2021 nitrogen law, which comprises: i) a legally binding obligation to ensure that the share of nitrogen-sensitive hectares in Natura 2000 areas below the critical deposition load is brought back to 40% by 2025, to 50% by 2030 and to 74% by 2030, ii) a comprehensive programme with nitrogen reduction measures, iii) a nature improvement programme, and iv) a system of regular monitoring and adjustment.

In the Coalition Agreement for 2021-25, the Dutch government announced it would meet these objectives by means of an integrated, area-oriented approach regarding nature, nitrogen, climate and water. For this purpose, the National Programme for Rural Areas was established. The government also brought forward from 2035 to 2030 the ambition to have 74% of the Natura 2000 areas below the critical deposition load. A transition fund of EUR 24.3 billion was announced to make substantial investments in sustainable farming and robust natural habitats to redress the balance.

After having been appointed as a moderator between government, farmers organisations and other stakeholders, Mr Remkes issued another report in 2022, which contains various policy suggestions, including the recommendation to buy out several hundred enterprises causing a very high deposition of nitrogen on vulnerable Natura 2000-areas (so called ‘peak loaders’) in order to significantly reduce nitrogen emissions for nature recovery, the legalisation of PAS-reporters and to enable further economic development. In November 2022, the government announced amongst other policy initiatives a specific approach for peak loaders. This approach aims to reduce emissions by a buy-out scheme for farmers, while simultaneously preparing obligatory measures if insufficient reduction is achieved. The government also announced it would develop new regulatory measures and pricing mechanisms to contribute to achieve the targets of the integrated approach (nature/nitrogen, water and climate targets). It also announced several limiting measures concerning permitting. The objective of these measures is to ensure the validity of permits and to limit the unintentional increase of nitrogen deposition in the permitting process (transfer of rights).

Source: OECD (2021[4]), Remkes Commission (2020[12]), Remkes (2022[13]), Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (2022[14]).

The DNB is a frontrunner of stress-testing “non-traditional” risks, such as the effects of cybercrime and climate change. Amidst increasing geopolitical tensions, banks and other financial institutions are increasingly exposed to cyber-attacks, which can be a powerful weapon to disrupt the economy and the financial system. Climate change increases the scale and frequency of natural disasters such as floods and storms, raising the claim burden for insurers and re-insurers, even though this will be reflected in premiums over time. Climate change policies, technological developments and changing consumer preferences in favour of sustainable solutions, could also pose a significant risk to the financial sector, particularly in the transition period (Merten and Verhoeven, 2022[15]). Current investments in companies with relatively large GHG emissions can decrease in value faster than expected leading to losses in banks’ asset position. While the current macroprudential toolkit for banks is able to hedge most of the systemic risks, data collection on non-traditional risks that could become systemic should be improved to evaluate whether these risks could be addressed within the existing framework or whether adjustments would be needed, e.g., a broader perspective on the resilience of financial infrastructures or limiting exposure to cyber-risks by reducing the concentration of operational services (European Systemic Risk Board, 2022[16]).

Table 1.3. Past recommendations on financial stability

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken since the previous 2021 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Continue to gradually reduce the maximum loan-to-value ratio on new mortgages from 100% in 2018 to 90% in 2028. |

No action taken. |

|

Gradually limit rent controls to a narrower part of the market. |

Rent controls are to be expanded from 2024. |

Addressing long-term fiscal challenges to maintain debt sustainability

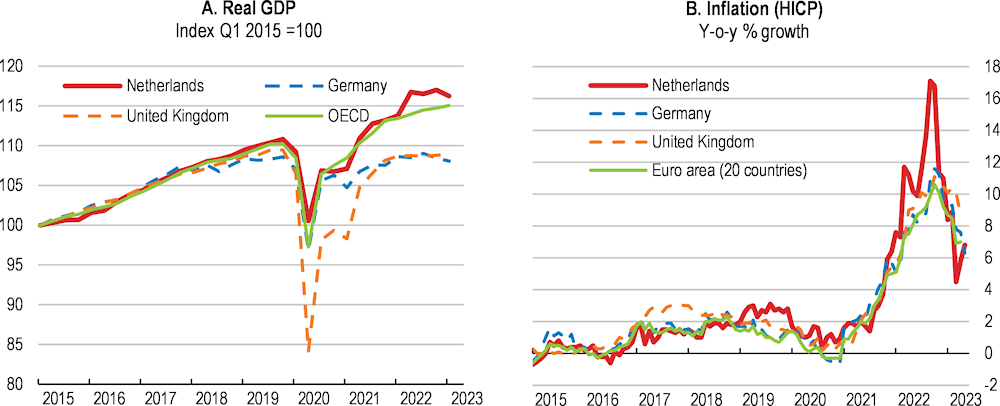

The Netherlands’ solid fiscal position enabled the government to provide unprecedented support to businesses and households during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fiscal surpluses turned into deficits, reaching 3.7% in 2020 before moderating to 0% of GDP in 2022 (Figure 1.11) due to lower COVID-19-related expenses and high economic growth. The Netherlands follows a trend-based fiscal policy framework, and at the start of a government term, the cabinet agrees on a maximum amount it may spend each year with limited room for exceeding commitments calling for explicit explanations for expenditure ceiling corrections. Since 2020, these annual real expenditure ceilings have been exceeded, as the COVID-19 pandemic and the energy crisis required fast implementation of fiscal support to prevent permanent damage to the economy (CPB, 2022[2]). Although deviations from the rules in situations of crisis are understandable, the government should clearly justify exceptions and ensure a quick return to compliance with budget rules.

Figure 1.11. The budget deficit and public debt remain moderate

% of GDP

The fiscal stance is expected to remain expansionary, as rapidly rising energy prices and cost of living prompted the government to provide support to households and firms once again (Table 1.4). In its 2022 September Budget (Ministry of Finance, 2022[1]), the government announced support measures totalling about EUR 16 billion (2% of GDP) in 2023 of which about EUR 11 billion are allocated to a purchasing power package to help households with the high cost of living. The package that came into effect January 2023 includes around EUR 6 billion in temporary measures, such as an energy discount for lower-income households, and about EUR 5 billion in structural measures, including amongst others a 10.2% rise in the minimum wage, rising social benefits, and a decrease in the rate of income tax payable in the first tax band (Box 1.1). The cost of the energy price cap will depend on energy prices in 2023, but is estimated at around EUR 5.1 billion (CPB, 2023[3]), coming on top of the purchasing power package. The debt-to-GDP ratio is likely to remain stable at around 50% of GDP in 2023 and 2024, as the energy price cap is expected to end December 2023 and that the government will not be able to spend some of the budgeted funds in the short term due to the tight labour market. In the context of high inflation, the government should better target the energy price cap at households in need and ensure that consumption thresholds are low enough to incentive energy saving. To improve targeting of future support measures, the government should accelerate the development of data and IT infrastructure to identify vulnerable households.

Table 1.4. A strong fiscal position allows for temporary support measures

Per cent of GDP

|

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023¹ |

2024¹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spending and revenue |

|||||

|

Total revenue |

44.1 |

44.4 |

44.5 |

44.4 |

44.3 |

|

Of which: |

|||||

|

Income tax |

13.2 |

13.6 |

14.3 |

14.5 |

14.6 |

|

Social contributions |

14.1 |

13.7 |

13.3 |

13.2 |

13.1 |

|

Other receipts |

16.8 |

17.1 |

16.8 |

16.7 |

16.6 |

|

Total expenditure |

47.9 |

46.7 |

44.5 |

45.4 |

45.0 |

|

Of which: |

|||||

|

Government consumption |

26.1 |

26.2 |

25.5 |

25.2 |

25.2 |

|

Social transfers |

11.1 |

10.7 |

10.1 |

10.1 |

10.4 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

3.7 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.5 |

|

Gross interest payments |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

|

Budget balance |

|||||

|

Fiscal balance |

-3.7 |

-2.4 |

0.0 |

-1.0 |

-0.7 |

|

Primary fiscal balance |

-3.2 |

-2.0 |

0.4 |

-0.6 |

-0.1 |

|

Cyclically adjusted fiscal balance2 |

-0.7 |

-1.0 |

-0.2 |

-0.7 |

-0.4 |

|

Underlying primary fiscal balance2 |

-0.3 |

-0.6 |

0.2 |

-0.5 |

0.1 |

|

Public debt |

|||||

|

Gross debt (Maastricht definition) |

54.7 |

52.5 |

51.0 |

50.5 |

50.3 |

|

Gross debt (national accounts definition)3 |

70.2 |

66.7 |

54.7 |

54.1 |

54.0 |

|

Gross financial assets (EUR billion) |

280.3 |

286.7 |

273.3 |

291.1 |

301.1 |

|

Net debt |

35.0 |

33.1 |

25.6 |

25.1 |

24.9 |

1. OECD estimates except otherwise stated.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. National Accounts definition includes state guarantees, among other items.

Source: OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database)

Shifting from crisis mode to long-term fiscal management

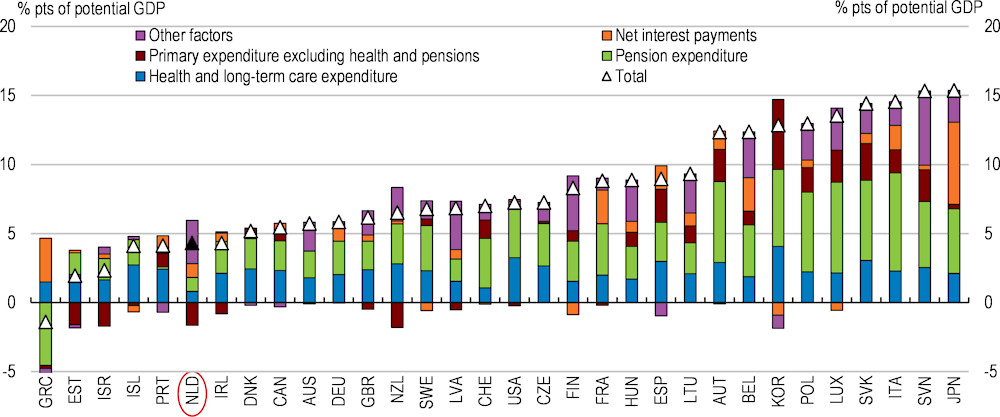

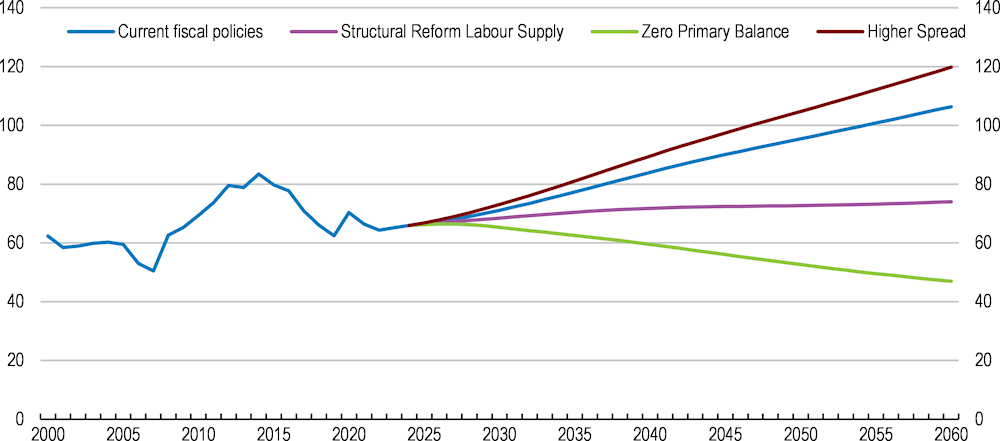

In the longer term, debt sustainability is challenged not only by the fiscal cost of ageing, but also by the risk of rising interest rates. In early 2022, the CPB projected that the policy package announced in the 2021 Coalition Agreement (Box 1.3, Government of the Netherlands (2021[17])) would lead to an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio by 2060 to 92% compared to a baseline scenario of no policy change at 28%, due to structural spending increases on education, social security, climate, environment and defence (CPB, 2022[18]). While these projections assumed a zero interest rate for the entire period, simulations for an interest rate of 1.5% or 3% show that debt could be pushed up to 113% and 151%, respectively (CPB, 2022[19]). Given the recent pension agreement linking the retirement age to life expectancy and the fully funded pillar two pensions, ageing pressures are relatively mild in a cross-country comparison (Figure 1.12). Moreover, the government announced in its 2021 Coalition Agreement measures aiming at limiting the increasing expenditure on health and long-term care (Box 1.3), but those have not yet been sufficiently worked out to be included in the analysis. Thus, in order to maintain the current debt-to-GDP ratio constant, subject to the assumptions of the OECD long-term model (Guillemette and Turner, 2023[20]), the structural primary revenue would have to increase by 4.3% of GDP, or corresponding savings would need to be implemented in the longer term. To preserve intergenerational equity and ensure that public debt remains sustainable, the government should prepare a multi-year fiscal strategy. Implementing labour market reforms that increase the employment rate and working hours (see Goos et al., (2022[21]) and Chapter 2), as well as reducing pathways into early retirement would boost medium-term growth and significantly reduce the public debt ratio in the longer term (Figure 1.13). The Netherland has a long tradition in providing spending reviews as part of the annual budget cycle. This expertise can be valuable in informing spending priorities and adapting to fiscal challenges, in particular ageing.

Figure 1.12. Population ageing will add to future spending pressures

Revenue increases needed to maintain a constant debt to GDP ratio from 2023 to 2060, by spending category

Note: The chart shows how the ratio of structural primary revenue to GDP must evolve between 2023 and 2060 to keep the gross debt-to-GDP ratio stable near its current value over the projection period (which also implies a stable net debt-to-GDP ratio given the assumption that government financial assets remain stable as a share of GDP). The underlying projected growth rates, interest rates, etc., are from the baseline long-term scenario. The necessary change in structural primary revenue is decomposed into specific spending categories and ‘other factors’. This latter component captures anything that affects debt dynamics other than the explicit expenditure components and includes potential new sources of expenditure pressure, for instance the energy transition, climate change adaptation or defence.

Source: Simulations using the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

Box 1.3. The 2021-25 Coalition Agreement

On 14 December 2021, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), the Christian Democratic Alliance (CDA), Democrats ’66 (D66) and the Christian Union (CU) approved the 2021‑25 coalition agreement “Looking after each other and looking ahead to the future”. The outlined policy plans of the new government focus amongst others on:

Climate and environment

Cutting greenhouse gases by 55% by 2030, with the focus on long-term impact, including the development of a new national power grid. Plans include spending of EUR 35 billion over 10 years on climate change.

Providing a total of EUR 24.3 billion up to 2035 for a National Rural Areas Programme. Part of it is likely to be used for the buying out of livestock farmers, who are partly responsible for the high level of nitrogen pollution near nature reserves (Box 1.2).

Building of two nuclear power plants.

Setting up a new fund to stimulate homeowners to insulate their properties as part of the move to a carbon neutral society.

Housing

Increasing the supply of new homes by 100 000 a year. At least two-thirds of these must be affordable rental homes or private homes with a selling price below the ceiling of the National Mortgage Guarantee (EUR 355 000 in 2022).

Permitting the building of new housing both within and outside city limits, abandoning previous standards to only build within existing built-up areas.

Improving the co‑operation across the entire housing chain – from local authorities and national government to developers and investors.

Social welfare

Reducing childcare expenditure for parents, by raising the childcare allowance for working parents to 95% of the costs, with the ambition of increasing this further to100%.

Reducing healthcare spending by EUR 4.5 billion up to 2052 including planned measures in the basic health insurance package such as no longer reimbursing certain (alternative) therapies and treatments, and the concentration of highly complex care in a limited number of hospitals. Planned measures also include, amongst other, collective framework agreements in which healthcare providers and insurers agree on a yearly ceiling on net expenditure growth, an agenda to improve the functioning of the healthcare system by promoting “the right care at the right place” and accelerate the shift from residential care to non-residential care.

Gradually increasing the minimum wage by 7.5%. This proposal was adjusted significantly in September 2022 and the minimum wage rose by 10.2% in January 2023.

Implementation of the new pension system, which has been finalised but not yet put into effect. Under the new system, the second pillar occupational pensions move from defined benefit to defined contribution pension rights. The new system gives more room for individual choices, although the provision of these choices is up to the pension funds. Furthermore, a new option is introduced which allows a withdrawal of 10% of the individual’s pension wealth around the statutory retirement age. The reform is likely to be fully phased in by 2027.

Budget:

Aiming for the budget deficit to be restored to a downward trajectory as soon as possible, while accepting temporarily a higher debt to solve problems facing the society. The associated underlying EMU balance is -1.75% of GDP (Table 1.5).

Table 1.5. Budget balance as outlined in the 2021 coalition agreement

|

% of GDP |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

Structural |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EMU balance |

Government’s calculations in the coalition agreement assume an earning effect of 42% for the government’s term of office. |

-3.2 |

-2.3 |

-2.4 |

-2.5 |

|

|

EMU debt |

58.6 |

59.0 |

59.6 |

60.4 |

||

|

Underlying balance (coalition target). |

With a balance of -1.75%, the debt will stabilise at 60% of GDP, assuming an interest rate of 0% and nominal GDP growth of 3%. |

-1.75 |

Source: Government of the Netherlands (2021[17]).

Figure 1.13. Reforms are needed to stabilise public debt

Gross public debt, % of GDP

Note: The Current fiscal policies scenario assumes the continuation of current fiscal policies and no offsetting of the rise in ageing related costs; the Structural Reform Labour Supply scenario assumes a stabilisation of the primary deficit to 2024 levels over the projection period and a progressive increase in the proportion of women working full-time from one quarter to one third over 5 years, which amounts to a 1% increase in labour input by 2030; the Zero Primary Balance scenario assumes a fiscal consolidation of 0.25 % points per year from 2025 until 2030 and the primary balance to stabilise to that level over the projection period, and no structural reform; the Higher Spread scenario assumes an increase in the Dutch sovereign spread of 50 basis points over the projection period, and no structural reform nor fiscal consolidation.

Source: Simulations based on preliminary projections from the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

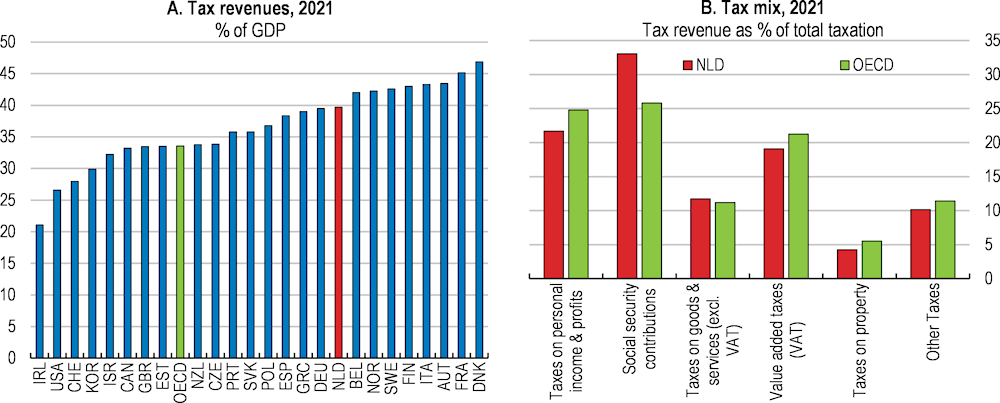

The tax system can be made more efficient, equitable and environmentally friendly. The Dutch tax-to-GDP ratio is at 40% well above the OECD average of 34% (Figure 1.14, Panel A), driven by high labour taxation (Figure 1.14, Panel B). Social security contributions, which are earmarked to fund pension, health and long-term-care spending, are particularly high compared to the OECD average. In the context of rapid population ageing, reforms should shift the tax burden from labour towards other taxes, such as capital income, property and consumption taxes, while also reducing the overall complexity of the tax system. Numerous deductions, exemptions and income transfers make the system overly complex, resulting in different income tax treatment of households in similar economic situations (Cnossen and Jacobs, 2021[22]). The government has stressed its ambition to simplify the tax system by abolishing the system of benefits administered by the Benefits Office, and has further explored policy options to address wealth inequalities introduced by the tax system (Ministry of Finance, 2022[23]; Government of the Netherlands, 2021[17]). Those are promising ambitions. The government could further focus on identifying and ending reliefs and exemptions that do not serve an economic, social or environmental purpose. The standard value-added tax (VAT) rate is 21%, but a 9% rate is applied to a wide range of goods and services. The government could consider moving towards a single uniform VAT rate in the medium term by broadening the VAT base and compensating lower income groups through the tax-transfer system to reduce distortions and address equity concerns. Environmental taxes represented 2.9% of GDP in 2021, significantly more than the OECD average of 1.1%, and constitute about 6.5% of Dutch government revenues (OECD, 2022[24]). But regressive rates apply on natural gas and energy taxes are significantly lower for energy-intensive firms than for small users, particularly households (OECD, 2021[25]; OECD, 2019[26]). In its Coalition Agreement and the 2022 September Budget, the government announced it would reduce the regressivity of these rates to incentivise decarbonisation and from 2024 and 2025, natural gas taxes will be higher than electricity taxes (Government of the Netherlands, 2021[17]; Ministry of Finance, 2022[1]). Electricity generation is covered by the European Union’s emission trading scheme (EU-ETS), but tax exemptions and reductions for fossil fuel not only distorts carbon price signals, but also led to an estimated EUR 4.48 billion (0.6% of GDP) in foregone revenues in 2021 (OECD/IEA, 2020[27]) and should be phased out.

Figure 1.14. High labour taxes push Dutch tax revenues above the OECD average

Table 1.6. Past recommendation on fiscal policy

|

Recommendations from previous Surveys |

Action taken since 2021 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Fully implement the tri-partite occupational pension agreement moving to defined contributions. |

The pension reform has been delayed and it is expected that the new pension system will now not come into effect until at least July 2023. |

Streamlining the tax system to remove distortions that hold back productivity

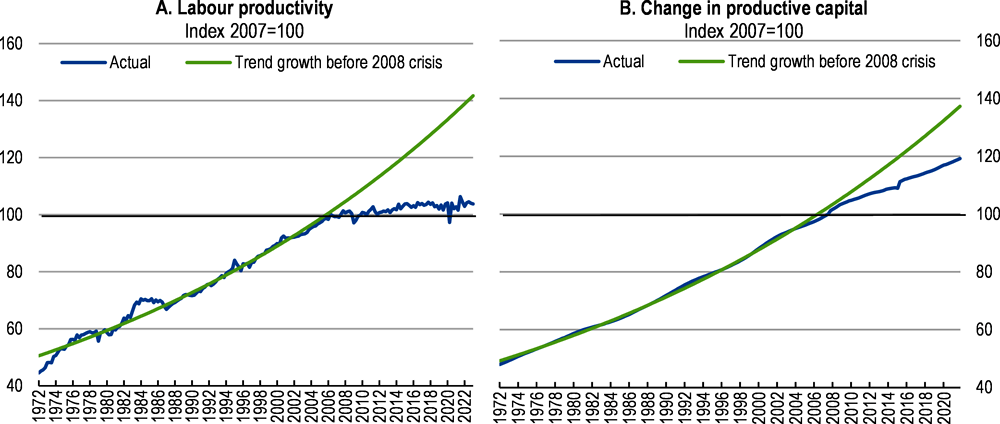

Reviving productivity growth is needed, as it has stalled since the global financial crisis (Figure 1.15, Panel A). With a strong ICT infrastructure and well-educated workforce, the Netherlands is well positioned to boost productivity through digitalisation as discussed in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]). However, the digitalisation process is held back by labour shortages of ICT professionals and lagging digital adoption of SMEs (OECD, 2023[28]). Smaller enterprises continue to significantly lag behind larger firms due to a lack of awareness and the fixed cost nature of investment in digital technologies, which drags on productivity growth. SMEs account for a relatively large share of employment and value added, the government developed policies to support the financing and digitalisation of SMEs in line with recommendations of the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]). It should continue its efforts and provide direct support to SMEs, including business advisory services and testing facilities, in order to increase awareness and help SMEs overcome barriers to the adoption of digital tools.

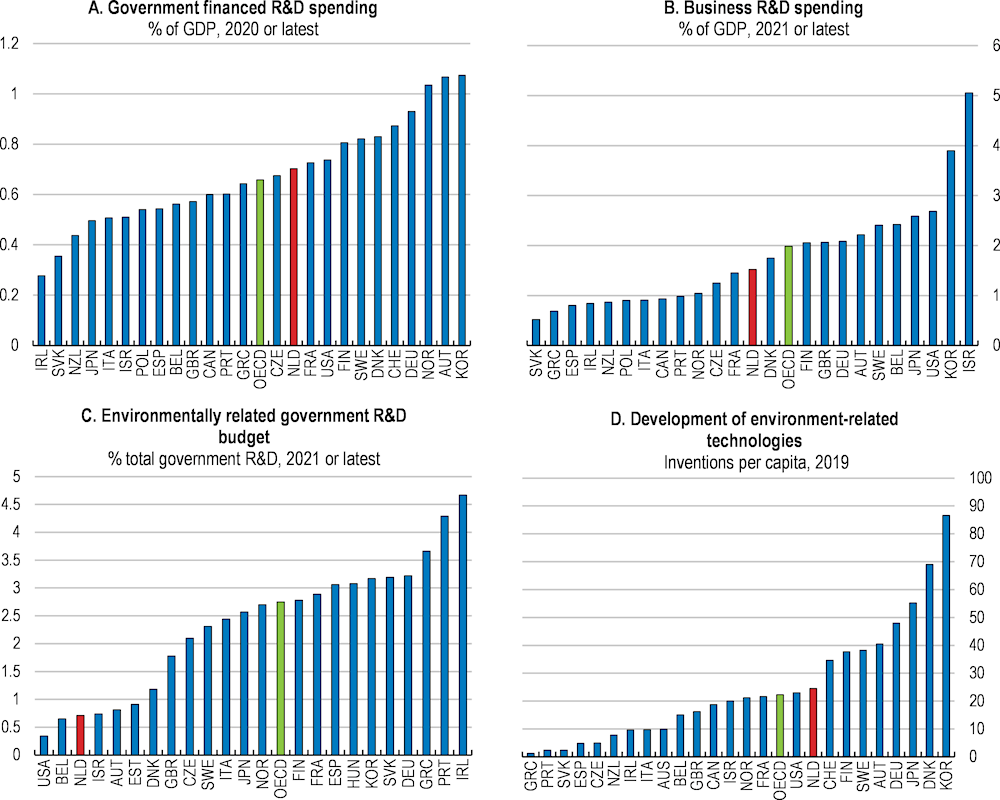

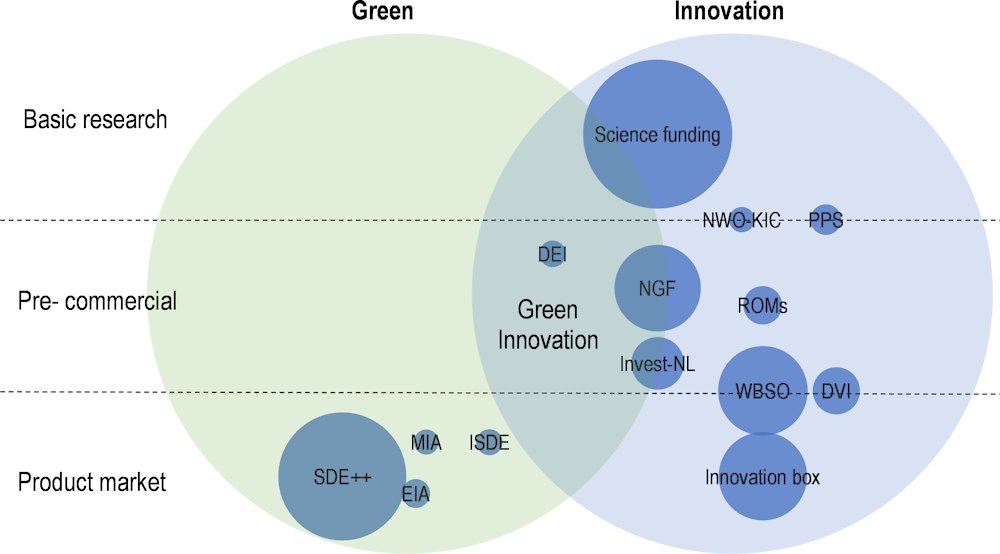

Weak investment is a key impediment to productivity growth as described in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]) (Figure 1.15, Panel B). The Netherlands has made significant advances to support investment through a multitude of investment packages and funds to support productivity, such as the National Growth Fund launched in 2021, which subsidises projects in the areas of knowledge development, research and development and innovation with a total of EUR 4 billion per year until 2025. As highlighted in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]), the increase in public investment is a welcome development, particularly in areas where private incentives to invest are too weak. The government could consider streamlining administrative procedures between different funds, as different timelines and procedures pose the risk of higher administrative cost for businesses (see below).

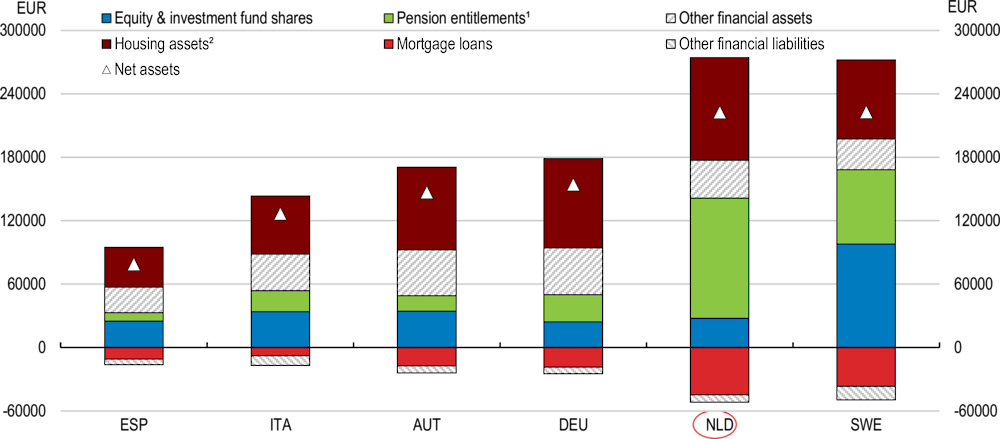

Private investment remains subdued as the tax system favours illiquid wealth accumulation, which may bind resources that would otherwise be available for more productive uses. In particular, tax deductions and exemptions on owner-occupied housing and on pensions result in households accumulating a relatively large amount of illiquid wealth (Figure 1.16). Similarly, a tax system that distorts labour supply decisions towards less productive uses can lead to lower productivity growth, if for example non-standard employment contracts with little incentives for skill accumulation are favoured.

Figure 1.15. Weak investments have contributed to lacklustre labour productivity growth

Note: Pre-crisis trend growth is calculated between 1972 Q1 and 2007 Q4, and is projected from 2008 onwards. In panel A, labour productivity refers to real GDP divided per total hours worked. Panel B refers to productive capital stocks. The increase in 2015 is due to a EUR 22 billion R&D purchase by a Dutch multinational enterprise.

Source: OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

Figure 1.16. Households hold high assets and high debt on average in the Netherlands

Household assets and liabilities per capita, 2021 or latest

Note: 1. Including life insurance and annuity entitlements. 2. Gross housing assets is proxied by the sum of net housing assets and mortgage loans.

Source: OECD (2023), “Financial Balance Sheets”, “Households’ financial assets and liabilities”, “Population and employment by main activity”, and “PPPs and exchange rates” in the OECD National Accounts Statistics (database); and Eurostat, Balance sheets for non-financial assets.

Making taxation neutral across assets

Investment decisions are influenced by the tax system. In December 2021, the Dutch Supreme Court ruled the taxation of income from savings and investments based on presumptive returns incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights (Box 1.4). As a result, the government adjusted capital income taxation, which will be based on actual returns as of 2026. This is a welcome step, but further efforts are needed to reduce distortions in investment decisions. As such, the government could consider the ruling as starting point to revisit and streamline the taxation of different types of income to reduce tax avoidance.

Box 1.4. The Dutch personal income and wealth tax system and the 2021 Supreme Court Ruling

The personal income and wealth tax system

Governed by the 2001 Income Tax Law, income is divided into three separate “boxes” (see Table 1.7). Each box taxes a different type of income according to different tax rules. Box 1 taxes labour income, self-employment income, pension benefits, transfer income and imputed rental income from owner-occupied housing at progressive rates varying in 2023 from 36.9% to 49.5%. Box 2 taxes profits distributed to, and capital gains realised by taxpayers who own at least 5% of a corporation, called substantial ownership, at a 26.9% rate in 2023. As long as no dividends are paid out and capital gains are not realised, income is only taxed at the corporate level. Box 3 covers all wealth except for owner-occupied housing, substantial ownership and pension wealth. Among other types of wealth, the Box 3 tax base includes bank deposits, bonds, non-substantial ownership of shares, and second homes.

Table 1.7. The three income boxes

Rates refer to 2023

|

Box 1 |

Box 2 |

Box 3 (Bridging Act Bill, until 2026) |

|---|---|---|

|

Employment income Business income of unincorporated firms Owner-occupied property - Imputed rent of 0.5% of the property value up to EUR 1.11 million, and 2.35% on the excess - Mortgage rate deduction (36.9%) Pension income - Pay-out at reduced rates - Contributions are tax deductible Tax rates: 36.93% for up to EUR 73 031; above 49.5%. Tax credit of EUR 3 070 for up to EUR 22 661; EUR 3 070-6.095% x (taxable income from work and home – EUR 22 660) for up to EUR 73 031. |

Income from substantial interest or holding (at least 5%) in a limited company. Income includes: Dividend income Capital gains Tax rate: 26.9% (in addition to corporate level taxes). |

Income from assets such as savings and investments are taxed on the returns of the assets, where returns vary by type of asset and are considered as follows: Savings: 0.01% Investment: 6.17% Debts: 2.46% Tax free capital limit: EUR 57 000. Tax rate: 32%. |

The 2021 Dutch Supreme Court ruling

On 24 December 2021, the Dutch Supreme Court ruled that the presumptive income tax regime in effect since 2017 violates the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The ruling concerns the years 2017 and 2018, with the tax authorities being ordered to review the tax declarations of at least 60 000 people who had objected to the presumptive capital income tax.

In the system that has been in force between 2017 and 2021, savers and investors paid tax of 31% on a set presumptive return on their assets. In doing so, the tax authorities have since 2017 assumed that taxpayers have a larger portion of their assets invested - and a smaller portion in their savings accounts - the richer they are (see Table 1.8). This system ignored the actual asset distribution of taxpayers, and a higher presumed proportion of investments in the asset mix implied a higher fictive return, resulting in overpayment for those with more savings. The Supreme Court not only ruled that the system violated the ECHR for all taxpayers whose actual returns were lower than the presumed – and taxed – returns, but also that legal redress had to be provided to all plaintiffs in the mass objection procedure. In 2022, the government paid a reimbursement to the plaintiffs totalling about EUR 2.8 billion (0.4% of GDP).

Table 1.8. Assumed portfolio allocation and return for the different tax brackets

2017

|

Tax brackets |

Assumed portfolio allocation |

Assumed returns |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Savings |

Investment |

||

|

EUR 0 – EUR 25 000 |

Exempt |

||

|

EUR 25 000 – EUR 100 000 |

67% |

33% |

2.90% |

|

EUR 100 000 – EUR 1000000 |

21% |

79% |

4.70% |

|

Above EUR 1 million |

0% |

100% |

5.50% |

Source: Ministry of Finance (2022[29]; 2022[1]), OECD (2018[30]).

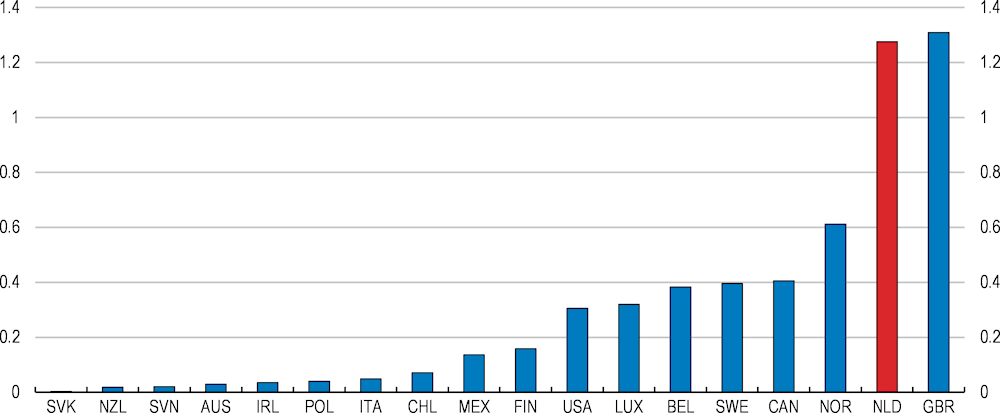

Owner-occupied housing enjoys favourable tax treatment compared to alternative investments. Although past policy measures have reduced some distortions, housing remains under-taxed compared to other wealth assets. Not only does this result in foregone tax revenue from tax relief for homeownership, which amounted to around 1.3% of GDP in 2020 (Figure 1.17), but also binds resourced that could be invested more productively. Although the mortgage rate deduction has been gradually lowered to match the basic income tax rate in the so-called “Box 1” of the Dutch tax code at about 37% in 2023 (Table 1.7), distortions towards debt biased homeownership remain. Moreover, individuals who live in their own home but have little or no mortgage debt left still benefit from the tax system, as imputed rents are subject to a deduction of 86.7% (2022), even though this deduction is reduced each year by 3.3% until being phased out by 2048. As stressed in the previous Economic Survey (OECD, 2021[4]), this tax bias has important implications for the functioning of the housing market, and more neutral taxation of different forms of wealth could free resources for more productive uses, help curb housing price growth, boost supply in the free private rental segment and increase residential mobility. The latter could play an important role when trying to attract labour to address labour shortages.

Figure 1.17. Foregone tax revenue from tax relief for home ownership is high

In percent of GDP, 2020

Note: Spending is missing for one of the policy instruments and the reported amount is therefore a lower-bound estimate for NOR, SWE, LUX, USA, CHL, POL, AUS. For more details on the exact calculations see https://www.oecd.org/els/family/PH2-2-Tax-relief-for-home-ownership.pdf.

Source: OECD Questionnaire on Affordable and Social Housing (2019, 2021).

Taxing homeowners in line with other wealth would help to attenuate inequalities. The tax system benefits homeowners, who tend to have higher incomes than renters, who are more likely to be young, of immigrant background and on non-standard work contracts (OECD, 2021[4]). Thus, the tax system leads to redistribution from households without an owner-occupied home or with a relatively cheap home to households with expensive homes, high mortgage payments and a high income, aggravating already high wealth inequality (Ministry of Finance, 2022[23]; OECD, 2022[31]). This incentive is reinforced because the profit on the sale of the owner-occupied home is not taxed. Phasing out the favourable tax treatment of owner-occupied housing through removing the mortgage interest deduction would allow for a more neutral taxation of different forms of wealth.

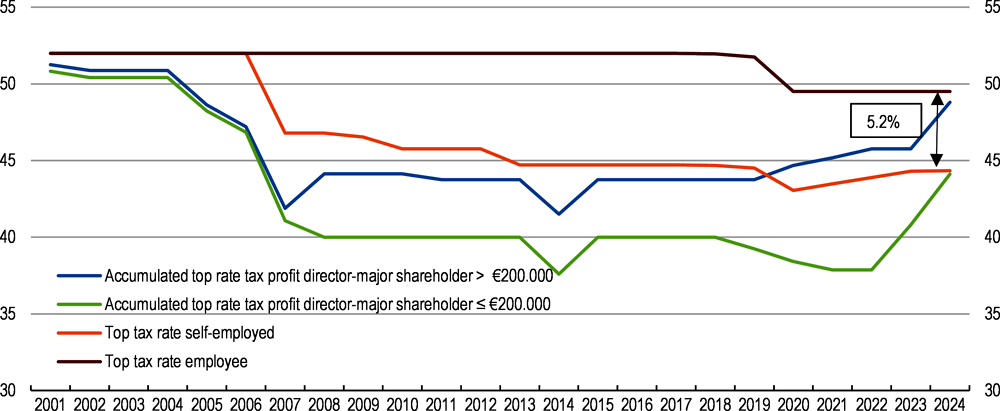

Reducing tax distortions across forms of employment

Labour income of workers, self-employed, and business owners is treated unequally. Differences in the tax treatment of work contracts creates incentives for self-employment. Over the past years, the self-employed without employees have consistently accounted for a substantial part of the increase in the share of non-standard employment (see Chapter 2). While non-standard types of work can reflect individual preferences for more flexibility in working relationships, they can also result in a deterioration of work quality, with weaker job and income security and greater wage inequality, as well as hamper productivity in the longer term, as incentives to invest in skill improvements are small (Goos et al., 2022[21]). Although tax rates were set to be neutral across forms of employment when the Box system was introduced in 2001, large discrepancies emerged over the years (Figure 1.18). Some tax relief is only available for self-employed entrepreneurs, resulting in beneficial tax treatment compared to employees. While both wages and income from self-employment are taxed in the same box of the tax system (Box 1.4, Table 1.7), own-account workers benefit from a self-employment deduction, a one-year starter’s deduction and also from a SME profit exemption allowing a lower taxable rate of earnings at 14%. The self-employed are not required to have mandatory insurance for illness, invalidity, or unemployment, nor pillar two pensions. This creates incentives for employers to hire people as own-account workers as their tax wedge is lower, and it may also leave the self-employed less protected in case they fail to arrange sufficient insurance from their net income (see previous Economic Surveys (OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2018[32]) for a discussion).

Figure 1.18. Differences in the top marginal tax rate by worker status have increased

Top marginal tax rates by worker status

The government has made several advances to reduce differences in the tax treatment of employees and self-employed. With its Tax 2023 plan (Ministry of Finance, 2022[1]), it accelerates the phasing out of the permanent self-employment deduction, from EUR 6 310 in 2022 to EUR 900 by 2027, compared to a previously slower phasing out to EUR 1 200 by 2030. The CPB estimates that this decrease could result in a structural revenue gain of about EUR 650 million, although subject to behavioural adjustment effects and a potential decline in self-employment (van Essen et al., 2022[33]). The gradual reduction of the permanent self-employment deduction is welcome, and in addition to recently announced government plans (Government of the Netherlands, 2023[34]), further adjustments could be made in line with the recommendations of the Commission for Work Regulation (“Borstlap” commission, see Chapter 2) to align tax rates and social security contributions between contract types for workers doing similar jobs.

Interaction effects of corporate and personal capital income taxation also create additional distortions in the way that labour is treated. A person who owns 5% or more shares in a company is, for tax purposes, treated as a combination of employee, entrepreneur and investor. For such a director and major shareholder, income can be taxed either as salary for labour input or as capital income. In the Netherlands, these income types are taxed differently: salary is taxed under Box 1 of the tax code; profits are first taxed with corporate income tax (CIT) and then income deriving from the substantial interest (dividends and the gain on the sale of one or more of the shares) is taxed under Box 2 of the tax code. The director and major shareholder has an incentive to keep the salary to the minimum legal requirement, as it faces the highest tax rate. Box 2 taxation can be deferred until profits are paid out as a dividend (or a capital gain on the sale). In 2022, about 97% of corporate income taxpayer fell below the threshold for the reduced rate, indicating that the system drives tax avoidance behaviour (Ministry of Finance, 2022[23]). The reduced CIT rate increases the incentive to defer profit distribution and hence Box 2 taxation. It also creates an incentive to define income as much as possible as capital income instead of labour income. By deterring firms from growing and providing incentives of splitting into smaller units, the current CIT system can weigh on productivity (IMF, 2016[35]). At the beginning of 2023, the government has increased the reduced CIT rate for profits from 15% to 19%, which is a step in the right direction, and reduced the ceiling from EUR 395 000 in 2022 to EUR 200 000. In 2024, the tax rate of Box 2 will be adjusted by introducing two brackets: a reduced rate of 24.5% for the first EUR 67 000 in income per person and a rate of 31% for the remainder. The basic rate of 24.5% increases the incentive to distribute profits. The government could further consider abolishing the reduced CIT rate, as the comparatively lower taxation of retained earnings creates a strong incentive to keep savings inside the corporations, and reduce the statutory CIT rate such that tax revenues remain neutral.

Table 1.9. Past recommendation on reducing distortions in investment and labour supply

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken since the previous 2021 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Phase out the permanent self-employment tax deduction. |

The phasing out of the permanent self-employment tax deduction has been sped up, to reach EUR 900 in 2027, compared to previous plans of reaching EUR 1200 in 2030. |

|

Align tax rates and social security contributions between contract types for workers doing similar jobs. |

In December 2021, the Dutch government adopted legislation that will make it compulsory for self-employed professionals to take out disability insurance (AOV). This legislation is expected to come into effect in 2024. |

|

Lower social security expenses, for instance by reducing the generosity for sickness insurance. |

No action taken. |

|

Reduce severance pay for employees who are dismissed under reasonable grounds. |

No action taken. |

Box 1.5. Quantifying the impact of selected recommendations

This box summarises potential medium-term impacts of selected structural reforms included in this Survey on GDP (Table 1.10) and fiscal balance (Table 1.11). The quantification impacts are merely illustrative. The estimated fiscal effects include only the direct impact and exclude potential behavioural responses that might occur due to a policy change. While recommended reforms in this survey have budget and GDP implications, not all can be quantified due to model limitations.

Table 1.10. Illustrative GDP impact of selected recommendations

|

Policy |

Scenario |

Impact |

|---|---|---|

|

Increase spending on training subsidies. |

Increase ALMP by EUR 1 billion to 0.7% of GDP to reduce the spending gap in training. |

0.5% increase in GDP per capita in 5 years, 2.7% long-term effect. |

|

Further stimulate business R&D. |

Raise business R&D by 0.4ppt of GDP to the OECD average. |

0.3% increase in GDP per capita in 5 years, 1.6% long-term effect. |

|

Streamlining the tax system1 |

Positive |

|

|

Labour market reforms1 |

A gradual increase in the proportion of women working full-time from one quarter to one third over five years, which amounts to a 1% increase in the labour input by 2030. |

Positive |

Note: 1. These reforms cannot be quantified within the model framework, but are likely to have a positive impact on GDP.

Source: OECD calculations based on the framework in Égert (2018[36]).

Table 1.11. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

|

Measure |

Description |

Additional fiscal revenue (% of GDP) |

|---|---|---|

|

Expenditures |

||

|

Increase spending on training subsidies. |

Increase ALMP by EUR 1 billion to 0.7% of GDP to reduce the spending gap in training. |

-0.1 |

|

Implement the childcare reform for people in work as planned. |

Increasing the subsidy for childcare costs to 96% for working parents. |

-0.3 |

|

Taxes |

||

|

Reduce favourable tax treatment of owner-occupied housing. |

The fiscal impact reflects additional tax revenue from scrapping mortgage interest rate deductions amounting to about EUR 6.4 billion.2 |

0.8 |

|

Reduce tax exemptions and reduced rates for fossil fuels. |

Tax exemptions and reduced rates for fossil fuels for energy intensive industries and other end-users are phased out. |

0.1 |

|

Introduce a single VAT rate. |

Move from the current dual rate structure of 9% and 21% to a single rate of 17.5% without compensating measures based on simple back-of-the envelope calculations. |

0.05 |

|

Reduce discrepancies in the tax treatment for different types of work contracts. |

Abolishment of low corporate income tax rate, and align tax rate and social security contributions between contract types for workers doing similar jobs.3 |

0.1 |

|

Lower labour taxation |

Reduce the marginal tax wedge, including on moving from part-time to full-time employment.4 |

-0.8 |