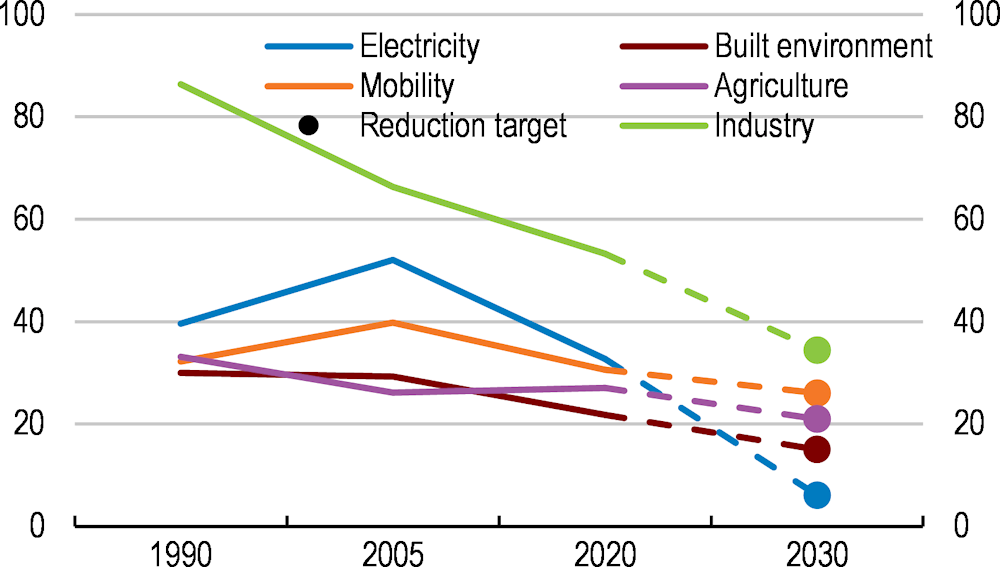

Fast-changing skill demand, low hours worked, and labour market segmentation contribute to tightness. About 28 000 technical jobs need to be created and filled to meet the country’s 2030 climate objectives – more than the current total employment in the energy sector. The incidence of part-time work is the highest in the OECD, with three out of four women and one out of four men working less than 35 hours a week. The 1.7 million workers on flexible contracts with little career prospects have weak incentives to work more.

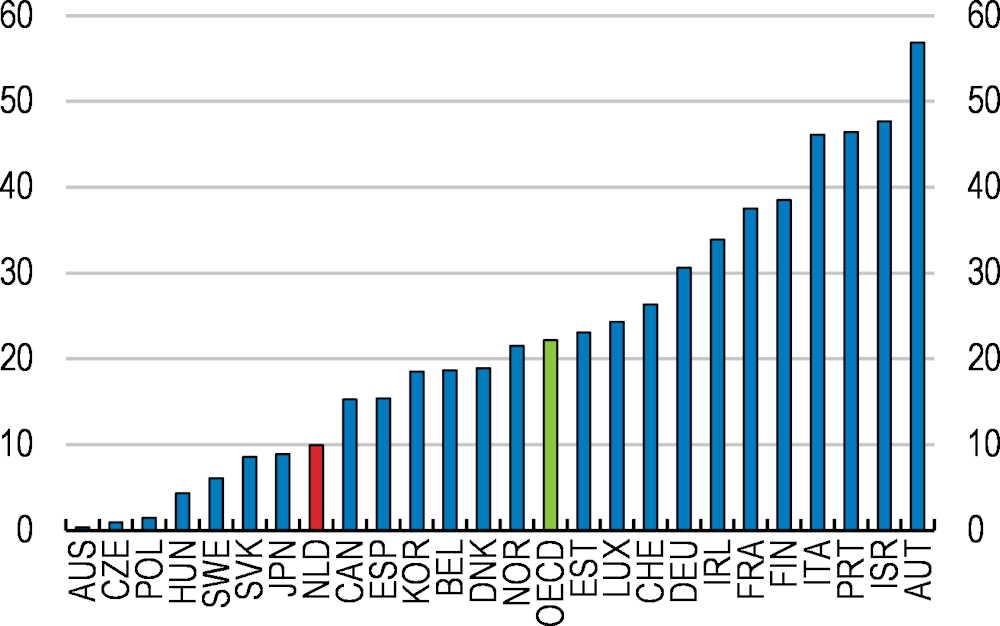

Training needs are massive and require the development of a stronger culture of lifelong learning. Total public spending on training falls short of estimated requirements by EUR 1.5-1.75 billion a year. Activation spending is high, but the share that goes towards training is low (Figure 5). The budget for the individualised training scheme introduced in 2021 (STAP) is too small, does not prioritise areas of skill shortages and lacks incentives for co-financing by employers.

Access to childcare is inadequate while looking after a child is the main reason for part-time employment. Low availability and affordability are important drivers of the unequal distribution of part-time work and ensuing gender inequalities. While urgent, implementing the reform to make childcare free for all working parents is challenging, as it is expected to strongly increase demand and worsen staff shortages in the short run. The repeal of the link between the amount of the childcare allowance and hours worked weakens work incentives.

Integration and the immigration system have responded little to labour market developments. The foreign-born have worse labour market outcomes. No migration scheme specifically targets medium-skill workers, despite their importance for the green transition. Hiring non-EU migrants currently requires labour market tests, even for shortage occupations.

Vocational education does not attract students, despite its strong potential to equip them with skills in high demand. Pre-vocational education faces declining enrolment and an image problem. Schools have no financial incentives to organise programmes across tracks or promote mobility between tracks. The existence of too many pre-vocational tracks complexifies education choices by students and their parents.

Cities and disadvantaged schools face acute teacher shortages, while inequalities in education are significant. The share of low-performing students increased from 14% to 24% over ten years. Even though one third of Dutch students attend schools with a lack of teachers, teaching in schools where shortages are significant is not rewarded with extra incentives.