This chapter details results of a novel and comprehensive survey on family carers in Croatia. It shows the profile of family carers in terms of demographics, socio-economic status, and care load. It also presents suggestions from focus group discussions on improving the current long-term care system, especially for family carer support.

Improving Long-Term Care in Croatia

3. Family carers need additional support

Abstract

In Croatia, as in many other EU countries, the bulk of care is provided by family carers, but little was known about them and their care situation. The OECD conducted a comprehensive survey under the guidance of the Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy by designing and carrying out a questionnaire and focus group discussions in 2020. Field work was conducted between March and July 2020. To reach family carers, a complex procedure was undertaken, with questionnaires sent to health centres, which redistributed them to visiting nurses, who lent them to family carers. About 220 visiting nurses and 1 126 family carers completed the questionnaire on family care, care recipients and the care situations. The completion rate was 63% and 33% of all visiting nurses in Croatia replied. The answers are considered representative of family carers of care recipients who receive care from both visiting nurses and family carers. In addition, twenty-three visiting nurses and eleven family carers participated in focus groups. The selection of 34 participants provided a good county coverage (Grad Zagreb, Splitsko-dalmatinska, Osjecko-baranjska, Istarska, Brodsko-posavska, Vukovarsko-srijemska, Primorsko-goranska and Koprivnicko-križevacka). The methodology of the survey is explained further in Annex A.

Family carers are mostly older women who are poor and feel fulfilled to provide a lot of (unpaid) care, but it takes a toll on them

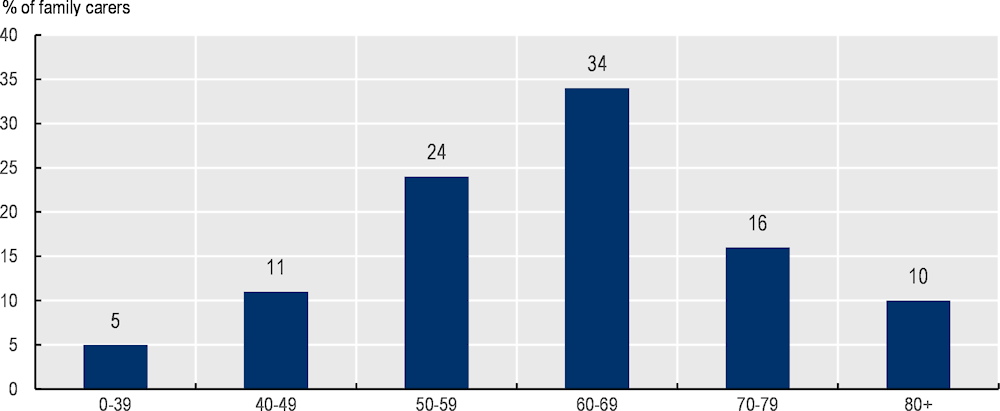

Nearly 75% of the responding family carers are women and the mean age is 62 years old. Still, about 40% are aged under 60 years old (Figure 3.1). About 67% are married or in a partnership, 13% have never been married, 7% are divorced and 13% are widowed. The overwhelming majority of carers has children (77%) who are typically adult. About 15% of carers live alone, 40% live with someone else, 22% live with two other people and the rest (23%) live with three or more other people. Slightly over half of carers are children or children-in-law supporting their parents or their parents-in-law. About one-fourth of carers are spouse or partner. Discussions from focus groups underlined that neighbours and friends may also provide help, but it is usually limited to a few household activities, such as doing the groceries and preparing some meals.

In Slavonski Brod-Posavina, Bjelovar-Bilogora, Koprivnica-Križevci, Sisak-Moslavina, Virovitica-Podravina and Vukovar-Srijem, over half of carers are aged below 60 years old. At the contrary, carers aged 70 and over represent 30% or more of carers in Split-Dalmatia, Osijek-Baranja, City of Zagreb, Primorje-Gorski kotar, Istria, Varaždin and Krapina-Zagorje. These results are broadly consistent with previous research in Zagreb City, although the mean age was relatively younger (55 years old) (Štambuk, Rusac and Skokandić, 2019[11]).

While 46% of carers report a fair, good, or very good health, 55% of them report a chronic illness or a disability and 54% report being limited in their own daily activities to some extent because of a health problem.

Figure 3.1. About one-third of family carers are aged between 60 and 69 years old

Source: OECD 2020 questionnaire to visiting nurses and carers in Croatia.

Family carers’ education level is relatively low. Over one-fourth of carers completed a primary school education, over half hold a high school degree while only about one-fifth had a bachelor or a most advanced education degree. These results are aligned with previous research in Zagreb City, although the education degree was slightly higher on average (Štambuk, Rusac and Skokandić, 2019[11]).

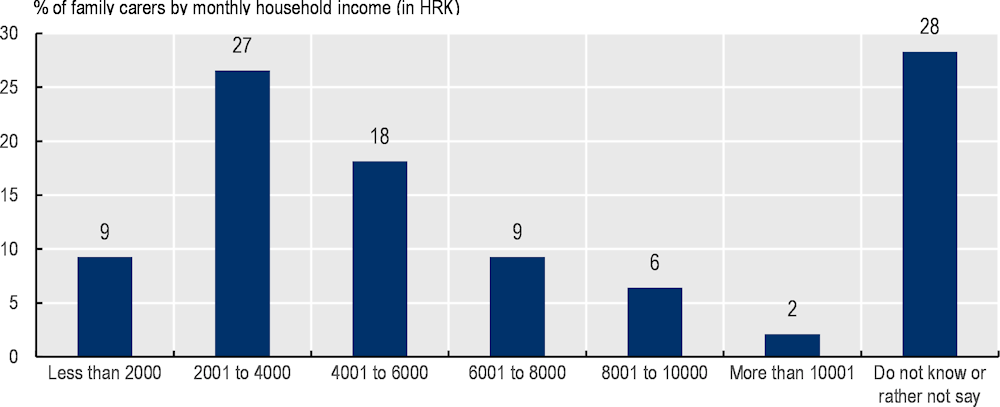

Most carers are from lower-income households, but nearly half own their dwelling

When looking at carers willing to provide information on their household’s income, over one-third of carers report a monthly household income under HRK 4 000, including for about 10% an income below HRK 2 000 (Figure 3.2). This is low in comparison to the minimum wage (HRK 3 750 in 2019). It is worth noting that 28% of carers indicate that they do not know or do not wish to provide information on their income.

Figure 3.2. Over one-third of carers report a monthly household income under HRK 4 000

Source: OECD 2020 questionnaire to visiting nurses and carers in Croatia.

The following information on equivalised income is based on the midpoint of above ranges. The median estimated equivalised earning is HRK 2 887 and 20% of carers earn an estimated equivalised income below HRK 1 732. These represent respectively about 64% and 38% of the median equivalised net income (HRK 4 517 in 2019). In other words, almost half of carers live below the poverty line based on these estimates (following the EU definition of financial poverty, which sets the poverty line at 60% of the median income).

With respect to carers’ assets, over 42% of carers who provided data own their dwelling without a mortgage, while 5% own it with loans. This is consistent with a previous study in Zagreb City (Štambuk, Rusac and Skokandić, 2019[11]).

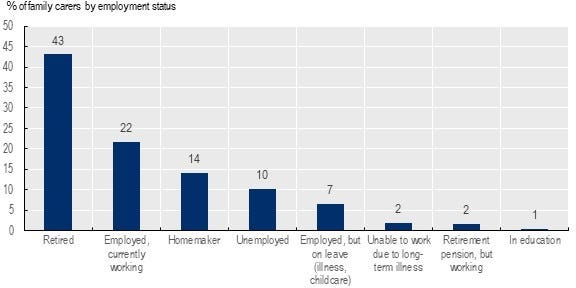

Most carers do not work

Nearly 45% of carers are retired while 40% are still in the labour market (Figure 3.3). About 22% are employed and working, 7% are employed but on leave (illness, childcare), 10% are unemployed and 2% are retired but still working. In addition, 14% of carers are homemakers. The vast majority (91%) report working full-time and only 4% report having reduced working hours because of care giving. Among those unemployed, 4% report that they stopped working because of care giving.

Figure 3.3. Nearly 45% of carers are retired and about 40% are still in the labour market

Source: OECD 2020 questionnaire to visiting nurses and carers in Croatia.

Results from the focus groups are consistent in terms of labour force status, except that some indicate they left their job because of care giving. Evidence from the literature is more in line with the results from the focus groups if family care is intense. It shows that carers heavily involved in caregiving are more likely to withdraw from the labour force (Colombo et al., 2011[12]).

Findings on paid informal carers are limited, but migration within and out of Croatia plays a role

The findings on informal care paid under the table are limited but still insightful to draw a picture of the grey market. It can be estimated that about 10% of responding carers are paid carers informally hired and paid by families. This estimate may be conservative because it is likely that many paid informal carers did not wish to participate to a questionnaire prepared for the Government of Croatia.

This 10% estimated is based on data on care relationship and compensation. About 16% of carers report that they support non-relatives, and these carers could be neighbours but also paid informal carers working in the grey market. Among the non-relatives, 63% report that they receive a compensation for time spent caring (compared with 4% for the relatives). Few carers report the number of hours compensated (128 observations), but related information might be of interest. The median number of compensated hours of care is 21 hours and the average is 38 hours. The average is driven in part by a substantial (14%) share of carers that are compensated 24/7. Thus, one can calculate that a conservative estimate is 10% (16% X 63%).

Visiting nurses believe that paid informal carers are more common in wealthier counties. Within Eastern counties, in rural areas, informal carers are uncommon because family ties are stronger, and families tend to be poorer. In urban areas, younger generations often left their home to move to bigger towns in other counties so they cannot provide daily care and informal carers are more common.

Focus groups indicated that migration from the poorest counties to neighbouring countries such as Austria and Italy and wealthier counties such as Istria depletes the local pool of paid informal carers in the poorest counties. In the North-Eastern counties, the paid informal carers prefer to work in Austria for the better working conditions. In North-Western counties, the picture is more nuanced. Even though paid informal carers from these counties emigrate to Italy where the pay is more than the double than in Croatia according to focus group participants, paid informal carers from Eastern counties move to North-Western to have higher wages. For example, the pay was about HRK 1500 for 15 days in Slavonski Brod in 2020 according to focus group participants. When the care recipient needs 24-hours care, two paid informal carers usually work in shift of 15 days, or else 12 hours/day. Focus group participants also reported that unpaid informal carers were paid around HRK 40 per hour in Zagreb City in 2020.

About three-quarters of carers provide personal care and help with household chores

About 75% of carers provide personal care and help with household chores, and 60% personal care, help with household chores and other types of support. The most common personal care is support in bathing or showering (69%), followed by support in dressing (62%), getting in and out of bed (50%), using the toilet (41%) and eating (37%). About one-fourth of carers provide these five types of support, suggesting that these carers look after care recipients completely reliant on support to live at home. Almost 90% of carers report helping with the groceries, 86% with cleaning the household, 75% with the laundry, 75% with the preparation of meals and 73% with the maintenance of the dwellings (e.g. gardening and or other maintenance chores). About 80% of carers provide other types of help, such as help with finances (70%), help with transport to leave the dwelling (70%), and help with medications (57%).

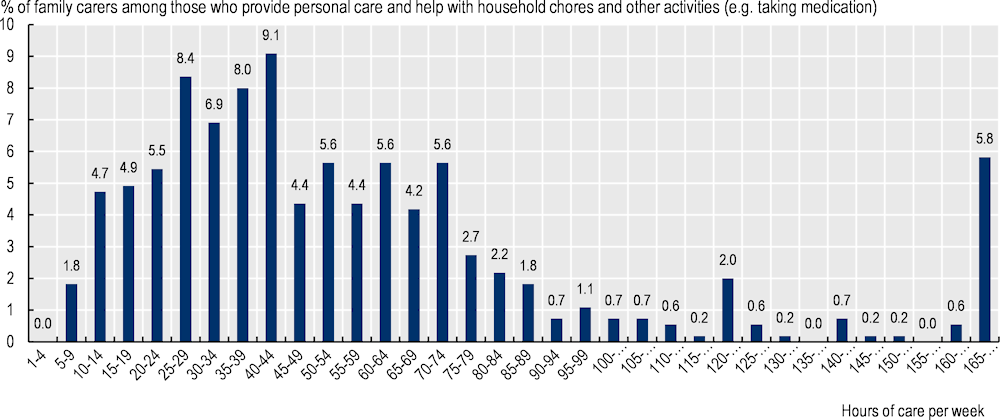

Caring takes more time than a ‘standard’ full-time job for 30% of all responding family carers. Among the 60% of carers reporting providing personal care, household chores and other types of support, the median number hours of care is about 45 hours per week and 6% provide care 24/7 (Figure 3.4). It may be possible that some carers could not allocate time spent on each type of support, overestimating the total number of hours of care.

Figure 3.4. Caring takes more time than a full-time job for half of the responding carers reporting personal care, household chores and other types of support

Note: These data are to be interpreted with caution as it may be possible that some carers could not allocate well time spent on each type of care or help, overestimating the total number of hours of care.

Source: OECD 2020 questionnaire to visiting nurses and carers in Croatia.

The number of hours of care is strongly associated with the frequency of care. Among those who care more than 10 hours per week, 85% care every day. Working family carers report a median of 35 hours of care, compared with 44 hours for non-working and non-retired family carers, and 50 hours of care for retired family carers. Caring may be so time-consuming that it can become difficult to juggle between care, work, and other activities.

About 90% of family carers (mostly women) with a job live in a household with at least one other adult and almost one-third live with a child aged below 18. In traditional households, these women would be expected to do the equivalent of three jobs: their paid job as an employee, the unpaid domestic work (e.g. cooking, cleaning) and the unpaid care work (older people and childcare). About 27% of carers who are employed report that they have problems to a great extent to juggle between care and their own daily activities, compared to 15% for retired carers.

Even if 90% of carers report fulfilled from care tasks, caring takes a toll

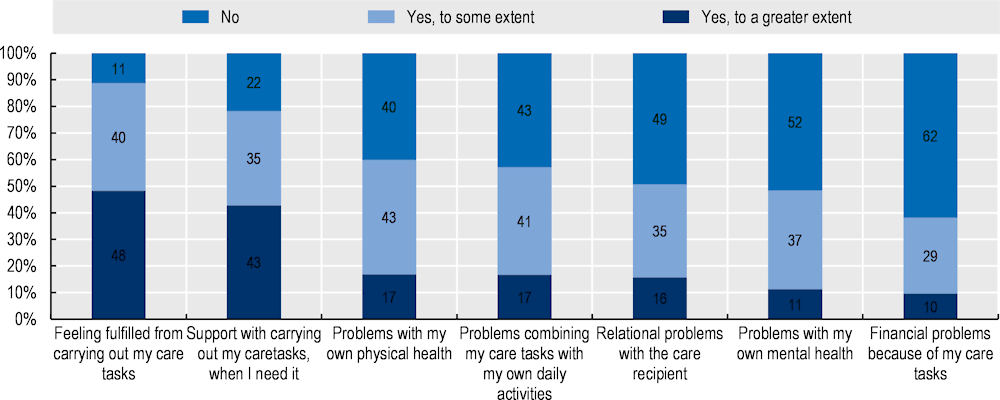

While about 90% report feeling fulfilled from carrying out care tasks and 78% report feeling supported, 60% report problems with their own physical health and 48% report problems with their own mental health. In addition, 57% of carers report problems to combine care tasks and their own daily activities and 38% report financial problems because of care tasks. About half of carers report relational problems with the care recipient (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5. Most carers feel fulfilled, but they also feel that care takes a toll on them

Source: OECD 2020 questionnaire to visiting nurses and carers in Croatia.

Focus group discussions highlight that those who bear the heaviest toll are family carers providing care 24/7 without the possibility to leave the care recipient for a few hours on a regular basis. The burden seems particularly difficult when the care recipient is bed-ridden and/or has advanced dementia. Focus group participants believe that nursing homes and foster care homes disregard bed requests of people with advanced dementia because of their dementia-related needs. Finding an appropriate substitute available for only a few hours on a punctual basis has also its array of challenges, so respite care is not guaranteed.

Preferred perceived options for improving care for the older people

Focus group participants highlighted training needs and financial support for family carers

According to participants of focus groups, family carers need more training to provide personal care and health care. For example, they commonly take care of wounds and pressure ulcers, and nurses train them “on-the-job,” but not always sufficiently. In addition, nurses train family carers to turn people in bed, change diapers and bath people using as little strength as possible. Nurses deem training as key to enable family carers to provide nursing care when nurses are absent since visiting nurses usually come one or twice per month in the morning. According to them, family carers need to learn more about nursing care early on, because they visit too rarely to provide training at the time when health conditions deteriorate (it can occur very quickly). They also believe that family carers should know more about broader determinants of health (e.g. nutrition, physical activity).

Some focus group participants mention that some visiting nurses could become care co‑ordinators and have this official responsibility. Croatia could learn from the example of Japan which created a new profession of LTC managers or from Germany. Such LTC managers or care co‑ordinators require a license and a qualification exam to co-ordinate provision of health and social services care needs for older people. Care managers carry primary responsibility for ensuring co‑ordination of care for older people with complex needs and are a first point of contact for such patients and their families (OECD, 2020[13]). In Germany, the community-based support for primary care (or AGnES) care model – nurses acting as case managers when visiting older people at home – provides specific training in case management. AGnES professionals can be qualified nurses or other assistants who have accumulated three years of professional experience; they receive training as a ‘Medizinischen Fachangestellten’ and an AGnES qualification. To work as case managers, they undertake an additional training module on communication and conflict management. AGnES nurses are also trained to deal with inter-professional and inter-sectoral collaboration (i.e. network and system management, co-ordination and control of aids, quality assurance in case management) and basics for taking a leadership role in care: assessing needs, monitoring and evaluating a patient (OECD, 2020[13]).

In addition, it may be worth training family carers to set boundaries, so that they feel less that their lives revolve only around care. Carers mention that older people can become more egocentric and impatient. Focus group discussions highlight that family carers providing care 24/7 should receive psychological support, because of the mental toll continuous care has on them.

Participants also agree that respite care, a cash benefit, and a carer status are essential support measures. Because it can be hard to find workers, they propose to introduce a new position of family carer for retired women, potentially those with a former professional background in nursing or childcare. These retired women could broaden the pool of competent workers willing to top up their pension with labour income.

Nursing homes are perceived as a last resort option

According to focus group participants, nursing homes tend to be seen as a last resort option in Croatia. It is the option when care recipients’ care needs are so complex that carers do not know or cannot provide sufficient care or cannot afford to pay for home care. In areas where each generation tends to live in their own house, family carers are seen as more likely to be employed and to be looking after their children. The move to nursing homes may be seen as the only option available that is both within their budget and that matches their time constraints. Conversely, nursing homes are not even considered as a last resort option for poor families living in rural areas. In families where multiple generations live in the same household, poor families have enough “hands” to provide care, and, in any case, they cannot afford nursing homes.

According to participants’ personal point of view, nursing homes have clear disadvantages. Beyond the lack of available and affordable places, inadequate quality was highlighted. Focus group discussions highlighted the poor-quality food, lack of staff (the ratio of one nurse per twenty residents was quoted multiple times) and poor-quality care. Interviewees think that nursing homes often disregard bed requests of people with complex needs (e.g. those immobile, with advanced dementia). They believe that residents with complex needs are often put in bed, tied up to wheelchair, or medicated. Some interviewees witnessed such issues, while others heard of them.

At the same time, participants support the development of nursing homes, not only because of the long waiting lists but also because they do not think that the younger (female) generations will be ready to put someone else’ needs first as much or will be able to. They believe that if quality improves, nursing homes would be a more attractive option. The main advantages of nursing homes mentioned were safety related to permanent supervision, socialisation, and group activities.

Quantitative data on the decision to provide family care confirms the qualitative findings. The most common combination is that family carers decide to care for the care recipient themselves and, at the same time, the care recipients decide that they do not to want to live in a nursing home. About 60% of carers report deciding to care for the older person, but in half of cases, the care recipients also decide that they do not want to live in an LTC facility. The results are similar across counties, except in Vukovar-Srijem and Osijek-Baranja, where the inability to pay for formal care is one of the main reasons to receive family care.

The focus group discussions nuance the picture on the decision of family carers to provide care. Participants report that many may help also out of social norms, especially in rural areas and especially if multiple generations live under the same roof. They believe that family carers may dare to go beyond social norms when their burden is very heavy, particularly when the care recipient is immobile and when it has advanced dementia.

Other types of care could be further developed

Other types of residential care – foster care and family homes – are better valued, but participants believe that the compensation for families make is unattractive when older people are immobile or with advanced dementia. Quality is considered higher: families are believed to have more time available to care as they can receive only up to four older people and standards are also higher (e.g. one older person per bedroom). Some believe that quality controls should be more frequent, notably because foster families provide care for financial reasons. In addition, they believe that foster families refuse people who are immobile or with dementia because the additional care is undervalued (the fee was between HRK 1 800 (about EUR 240) and HRK 2 400 (EUR 315) depending on the health condition of the older people).

With respect to care at home, participating visiting nurses propose to develop mobile teams to reach out to isolated people. The team could be composed of professionals who can provide health care and personal care. The idea behind is that mobile teams could visit more frequently each older person (visiting nurses tend to visit 1-2 times a month most older persons, while personal care needs are often daily needs). Croatia could implement the Buurtzorg model which originally started in the Netherlands and has been replicated in several countries. The model includes self-managed teams of nurses that are often composed of up to twelve nurses and support 50-60 patients at a time. The nurses provide a wide range of care; they also try to mobilise the client’s social network and work closely with general practitioners and other community health care workers (OECD, 2020[13]). In addition, participating visiting nurses also suggest developing day-care centres where older people can spend days of half-days.

In addition, participating family carers underline that the applicants to the Zaželi programme should be screened for mental health issues. It seems that some grapple more with mental health issues when they start to provide care and they can refuse to visit severely ill patients (e.g. those with advanced dementia, epilepsy). There is a solid body of evidence that caregiving causes or worsens mental ill health symptoms such as depressive symptoms, particularly when caring for older people with dementia (del-Pino-Casado et al., 2019[14]; Rocard and Llena-Nozal, 2022[15]).

Focus group participants also discussed the tasks of health care professionals. Insights from these discussions are in Annex B.