This section focuses on the factors that impact the value of fake imports. The value of imports of fake goods was calculated using data from customs seizures of small parcels to which the OECD methodology described in (OECD/EUIPO, 2016[3]) and (OECD/EUIPO, 2019[1]) was applied.

Why Do Countries Import Fakes?

2. Factors that shape imports of fakes

1. Imports of fakes in small packages: what does this trade look like?

Which countries import counterfeit goods?

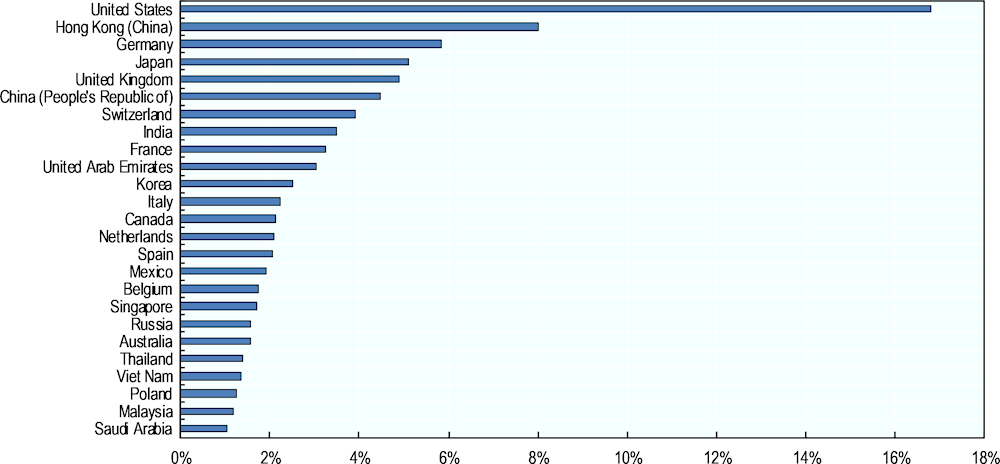

Figure 2.1 shows that when considering the estimated value of fake imports, the United States remains by far the first importer of counterfeit goods shipped in small packages. However, the picture differs somehow from the one based on raw customs seizures data. One can note that in addition to European countries, importers of small parcels of counterfeit goods are in different regions such as Asia, Gulf region, South America, and Oceania. Overall, fake imports were mostly destined to countries quite well integrated in international trade in absolute terms.

Figure 2.1. Distribution of the value of fake imports, by destination economies, 2019

Source: OECD/EUIPO calculations

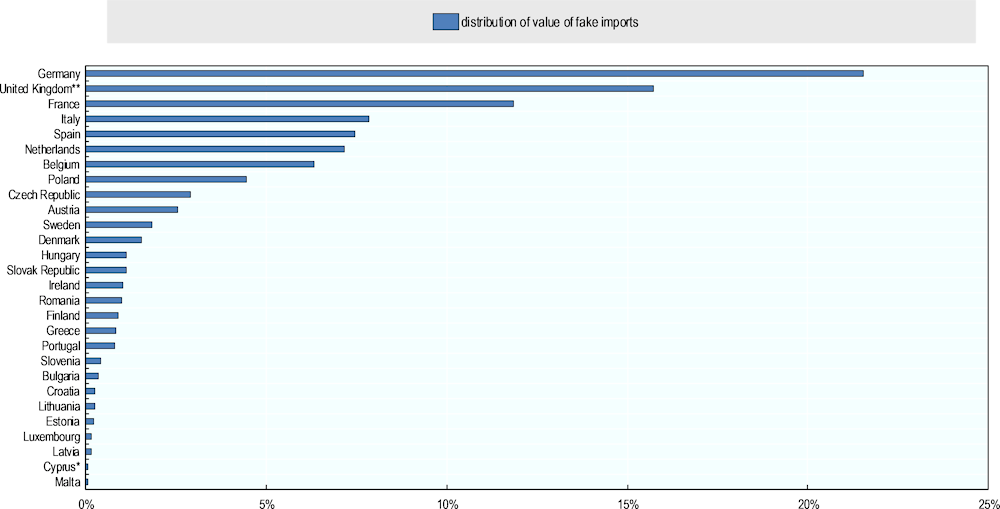

Figure 2.2 shows the distribution of the value of fake imports into the EU by destination economies. Germany was the country with the highest value of fake imports in 2019. It was followed by United Kingdom, France, and Italy.

Figure 2.2. Distribution of the value of fake imports in the EU, by destination economies, 2019

* Note by Türkiye: the information in this document with reference to "Cyprus" relates to the southern part of the Island. There is no single authority representing both Turkish and Greek Cypriot people on the Island. Türkiye recognizes the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Until a lasting and equitable solution is found within the context of the United Nations, Türkiye shall preserve its position concerning the "Cyprus" issue. Note by all the European Union Member States of the OECD and the European Union: the Republic of Cyprus is recognised by all members of the United Nations with the exception of Türkiye. The information in this document relates to the area under the effective control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus. ** United Kingdom is included in EU countries as the analysis refers to the period prior to the Brexit.

Source: OECD/EUIPO calculations.

Table 2.1 shows that United Kingdom and France appear as main importers of fakes among EU member states in both absolute and relative terms. It also indicates that Spain, Poland, and the Czech Republic are among the largest importers of counterfeit goods in the EU in relative terms.

Table 2.1. Top 15 destination economies of counterfeit imports destined to the EU countries, 2017-19

|

Rank |

Value of fake imports |

Share of fakes in total imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Germany |

United Kingdom* |

|

2 |

United Kingdom* |

Spain |

|

3 |

France |

Poland |

|

4 |

Italy |

France |

|

5 |

Spain |

Czech Republic |

|

6 |

Netherlands |

Germany |

|

7 |

Belgium |

Italy |

|

8 |

Poland |

Netherlands |

|

9 |

Czech Republic |

Denmark |

|

10 |

Austria |

Greece |

|

11 |

Sweden |

Austria |

|

12 |

Denmark |

Belgium |

|

13 |

Hungary |

Slovak Republic |

|

14 |

Slovak Republic |

Finland |

|

15 |

Ireland |

Estonia |

Note: * United Kingdom is included in EU countries as the analysis refers to the period prior to the Brexit.

Source: OECD/EUIPO calculations.

What counterfeit products are imported?

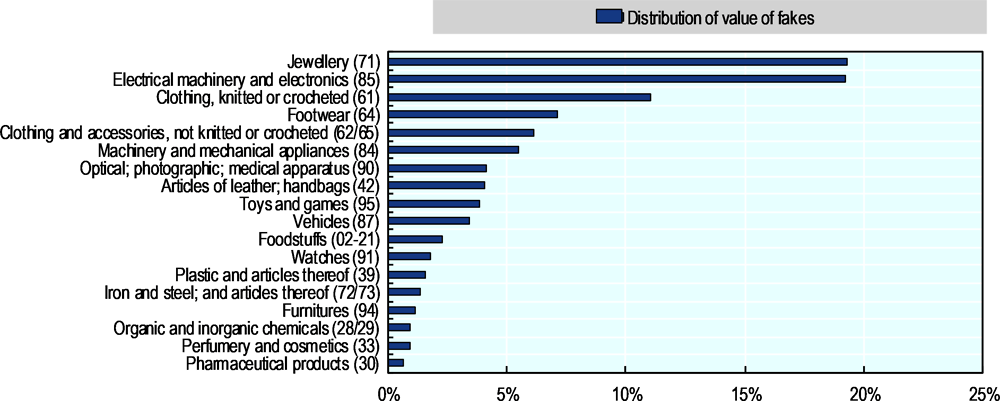

Figure 2.3 shows the distribution of the value of fake imports by product categories. It indicates that the range of fake goods traded is very wide including common goods (footwear, ready-to-wear items), luxury goods but also potentially dangerous fakes such as toys and games, spare parts, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Jewellery and electronics were the two product categories associated with the highest value of imported fake products in 2019. They were followed by clothing and footwear.

Figure 2.3. Distribution of the value of fake imports, by product categories, 2019

Source: OECD/EUIPO calculations.

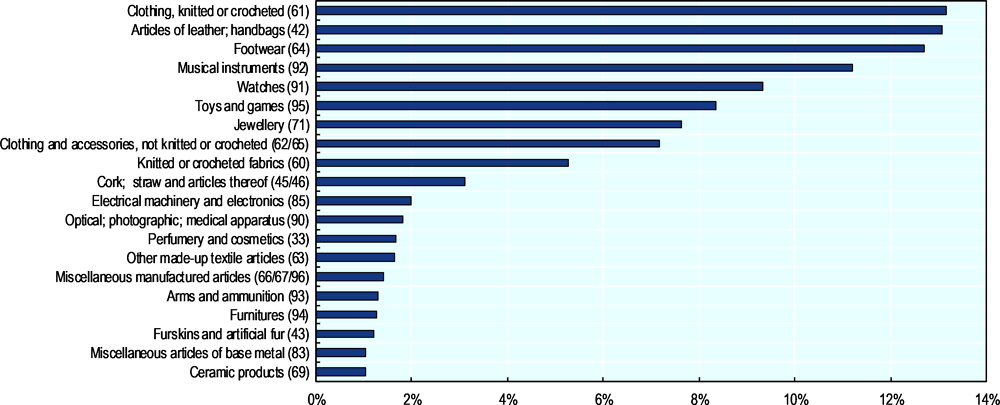

Fake clothing, leather goods and footwear are the product categories in which fakes are most often imported in relative terms (see Figure 2.4). This figure also indicates that the share of fakes in total imports is significant for musical instruments while its associated value is limited. It is also the case – but in a lesser extent – for fake watches and toys and games.

Figure 2.4. Top product categories of counterfeit goods shipped in small parcels, in relative terms, 2019

Source: OECD/EUIPO calculations.

Tables 2.2 – 2.7 focus on imports of counterfeit products by sector. Special attention was paid to sectors where fakes can pose direct health and safety risks such as food, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and toys and games. The case of common products frequently seized like clothing and electronics was also analysed.

Table 2.2 indicates that the value of fake imports, in relative terms (e.g., in terms of fake imports of food in total imports of food), Asian and African countries were the main importers of counterfeit food products. In absolute terms, China and OECD countries dominate, however.

Table 2.2. Top 15 importers of counterfeit food products

|

Rank |

Value of fake imports |

Share of fakes in total imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

United States |

Macau (China) |

|

2 |

China (People's Republic of) |

Comoros |

|

3 |

Japan |

Afghanistan |

|

4 |

Germany |

Mongolia |

|

5 |

Netherlands |

Lao People's Democratic Republic |

|

6 |

France |

Hong Kong (China) |

|

7 |

United Kingdom |

Thailand |

|

8 |

Hong Kong (China) |

Benin |

|

9 |

Spain |

Madagascar |

|

10 |

Korea |

Indonesia |

|

11 |

Italy |

Cambodia |

|

12 |

Russia |

Myanmar |

|

13 |

Belgium |

Côte d'Ivoire |

|

14 |

Canada |

Mauritania |

|

15 |

Saudi Arabia |

Kuwait |

As for imports of counterfeit medicines, six African countries are among the 15 top importers in relative terms.

Table 2.3. Top 15 importers of counterfeit pharmaceuticals

|

Rank |

Value of fake imports |

Share of fakes in total imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Argentina |

Argentina |

|

2 |

United States |

Afghanistan |

|

3 |

Germany |

Brunei Darussalam |

|

4 |

Belgium |

Palestinian Authority* |

|

5 |

Switzerland |

Yemen |

|

6 |

China (People's Republic of) |

Georgia |

|

7 |

Japan |

Burundi |

|

8 |

United Kingdom |

Lao People's Democratic Republic |

|

9 |

Italy |

Zambia |

|

10 |

France |

Gambia |

|

11 |

Netherlands |

Madagascar |

|

12 |

Spain |

Rwanda |

|

13 |

Russia |

Cambodia |

|

14 |

Canada |

Nigeria |

|

15 |

Korea |

Aruba |

In absolute terms, the United States, China, and Hong Kong (China) were the largest importers of counterfeit cosmetics. In relative terms, Afghanistan, Yemen, and India were the top destination countries for fake cosmetics, associated with the highest shares of fake imports in this sector.

Table 2.4. Top 15 importers of counterfeit cosmetics

|

Rank |

Value of fake imports |

Share of fakes in total imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

United States |

Afghanistan |

|

2 |

China (People's Republic of) |

Yemen |

|

3 |

Hong Kong (China) |

India |

|

4 |

Germany |

Indonesia |

|

5 |

United Kingdom |

Lao People's Democratic Republic |

|

6 |

Japan |

Belize |

|

7 |

France |

Viet Nam |

|

8 |

Singapore |

Philippines |

|

9 |

United Arab Emirates |

Mauritania |

|

10 |

Russia |

Comoros |

|

11 |

Thailand |

Ecuador |

|

12 |

Saudi Arabia |

Gambia |

|

13 |

India |

Rwanda |

|

14 |

Canada |

Burundi |

|

15 |

Netherlands |

Pakistan |

The main importers of counterfeit toys and games are developed countries with the United States, Japan, Germany, and United Kingdom being those with the highest value of fake imports in this field. In relative terms, the United States and Japan also appear as large importers, but the largest ones were Yemen, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan.

Table 2.5. Top 15 importers of counterfeit toys and games

|

Rank |

Value of fake imports |

Share of fakes in total imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

United States |

Yemen |

|

2 |

Japan |

Pakistan |

|

3 |

Germany |

Uzbekistan |

|

4 |

United Kingdom |

Afghanistan |

|

5 |

Hong Kong (China) |

Myanmar |

|

6 |

France |

Lao People's Democratic Republic |

|

7 |

Canada |

Ecuador |

|

8 |

Spain |

Brazil |

|

9 |

Australia |

Mauritania |

|

10 |

Netherlands |

United States |

|

11 |

Mexico |

Egypt |

|

12 |

Russia |

Hong Kong (China) |

|

13 |

Poland |

Indonesia |

|

14 |

Korea |

Cambodia |

|

15 |

Italy |

Japan |

The United States, Germany and Japan were the three first destination economies for fake clothing in terms of value of fake clothing imported. When considering the share of fake imports of clothing among genuine imports, Yemen, Rwanda, and Afghanistan were the three economies most affected by imports of fake ready to wear articles.

Table 2.6. Top 15 importers of counterfeit clothing

|

Rank |

Value of fake imports |

Share of fakes in total imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

United States |

Yemen |

|

2 |

Germany |

Rwanda |

|

3 |

Japan |

Afghanistan |

|

4 |

United Kingdom |

Pakistan |

|

5 |

France |

Gambia |

|

6 |

Spain |

Palestinian Authority* |

|

7 |

Hong Kong (China) |

Kyrgyzstan |

|

8 |

Netherlands |

Madagascar |

|

9 |

Italy |

Azerbaijan |

|

10 |

Canada |

Egypt |

|

11 |

Australia |

Burundi |

|

12 |

Korea |

Chile |

|

13 |

Poland |

Belize |

|

14 |

Russia |

Jordan |

|

15 |

Belgium |

Armenia |

Table 2.7 shows that counterfeit electronics were mostly destined to countries well integrated in the international trade with Hong Kong (China), the United States and China being the three main destinations of counterfeit electronics, in terms of value of fakes. When considering the share of fake imports of electronics, one third of the main importers are African countries, while Asian countries also figure prominently. This means that Africa and Asia can be seen as specific targets for counterfeit electronics.

Table 2.7. Top 15 importers of counterfeit electronics

|

Rank |

Value of fake imports |

Share of fakes in total imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Hong Kong (China) |

Pakistan |

|

2 |

United States |

Macau (China) |

|

3 |

China (People's Republic of) |

Yemen |

|

4 |

Germany |

Afghanistan |

|

5 |

Japan |

Kyrgyzstan |

|

6 |

Korea |

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

|

7 |

Mexico |

Togo |

|

8 |

India |

Côte d'Ivoire |

|

9 |

Viet Nam |

Cambodia |

|

10 |

Singapore |

Hong Kong (China) |

|

11 |

Netherlands |

Kenya |

|

12 |

United Kingdom |

Nigeria |

|

13 |

Malaysia |

India |

|

14 |

France |

Myanmar |

|

15 |

United Arab Emirates |

Indonesia |

2. What are the main drivers of imports of fakes?

The purpose of this section is to highlight the relations that exist between some factors and the value of imports of fakes. The analysis is carried out at a country level for a one-year period (2019). The selected factors are in principle country-level reflections of specific microeconomic drivers of intentional and unintentional demand discussed in the sections above. These factors include indices of economic development, demographics, education, use of Internet, and logistical and trade performance.

Modelling the value of fake imports

While some links between these indices and the imports of fakes are obvious a priori, some results can be more difficult to determine and require further analysis. For example, economic development can determine the ease of Internet access, but on the other hand it can be also linked to the overall level of quality of governance framework, including IP enforcement.

To better understand the role of each of the factors impacting the demand for fakes, a multiple regression model was used. This statistical method is designed to model relationships between an independent variable and various predictors. It also provides the magnitude of the effects of each predictor on the independent variable.

The factors impacting the value of fake imports are described and the results of the multiple linear regression model are discussed below. Table 2.8 presents the results of the best multiple linear regression in terms of adjusted R2, significance of coefficients, normality of errors and absence of multicollinearity between independent variables.

Table 2.8. Multiple regression of the value of fakes (in log)

|

Multiple regression of the value of fakes (in log) |

|

|---|---|

|

Imports (in log) |

1.006*** |

|

(0.0412) |

|

|

Infrastructure |

0.367*** |

|

(0.0902) |

|

|

Population aged 65 + |

-0.063*** |

|

(0.0111) |

|

|

Individuals using Internet |

0.015** |

|

(0.00491) |

|

|

Tertiary education |

0.013** |

|

(0.00415) |

|

|

GDP per capita (in log) |

-0.349** |

|

(0.105) |

|

|

constant |

-3.336** |

|

(0.988) |

|

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.960 |

|

N |

61 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Source: OECD/EUIPO calculations.

As can be seen in Table 2.8, the variable to be explained in our model is the log of the value of imports of fakes. The use of logarithmic specification is linked to improving model fit. The model comprises six explanatory variables and a constant term, including:

The value of imports by country (in USD). For model performance reasons, this variable is expressed in log;

The quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure. This index reflects professionals’ perceptions of quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure of each country and ranges from 1 to 5: the higher the score the better the performance;

The population aged 65 and above as a share of total population;

The share of individuals using Internet of each country;

The gross graduation ratio of tertiary education;

The GDP per capita in USD, which is expressed in log for a better model fit.

The detailed data descriptions can be found in Appendix B of this report.

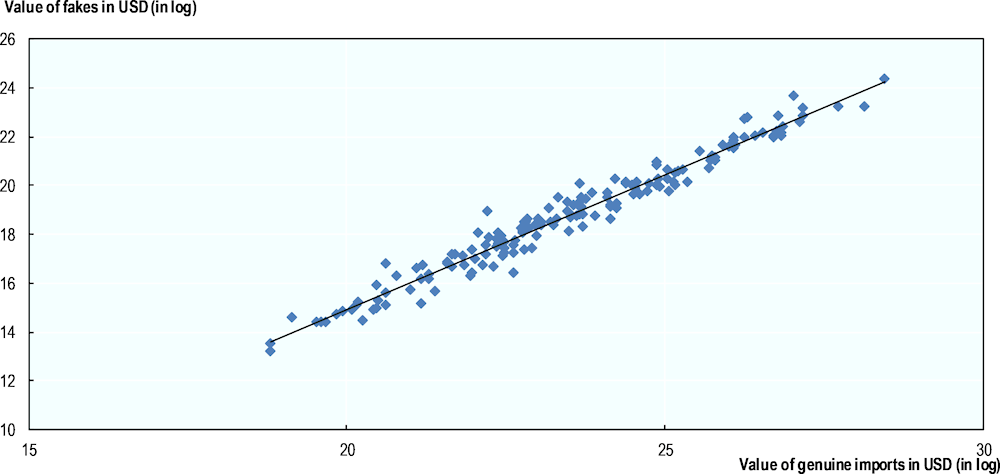

Imports

Figure 2.5 indicates a very strong and positive correlation between the value of fake imports and the value of genuine imports. The higher the imports of a country, the higher the value of fake imports.

Figure 2.5. Link between the value of fake imports and total value of imports

Note: This graph should be interpreted carefully. To avoid any confusion, it is important to point out that for each country, the value of imports of fake goods is lower than the total value of imports (official trade data) but both values are high in absolute terms. On this graph, these two values may appear close due to the log entry, but they differ in reality. Indeed, the y-values of large x-values are closer together in the case of a logarithmic function, whereas the y-values of small x-values are further apart. Each point corresponds to one country for 2019.

Source: UN Comtrade database and OECD/EUIPO calculations.

The statistical model confirms that genuine imports are an important driver of fake imports, as Table 2.8 shows an increase in value of genuine imports is associated to a significantly increase of the value of fakes imports.

This result is somehow straightforward, particularly when considering that the regression uses the value of imports of fakes as the dependant variable. In this context the value of imports to an economy, in addition to its straightforward explanatory power, captures the scale effect, when a large economy is a more significant importer of fakes only because of its large volumes of trade.

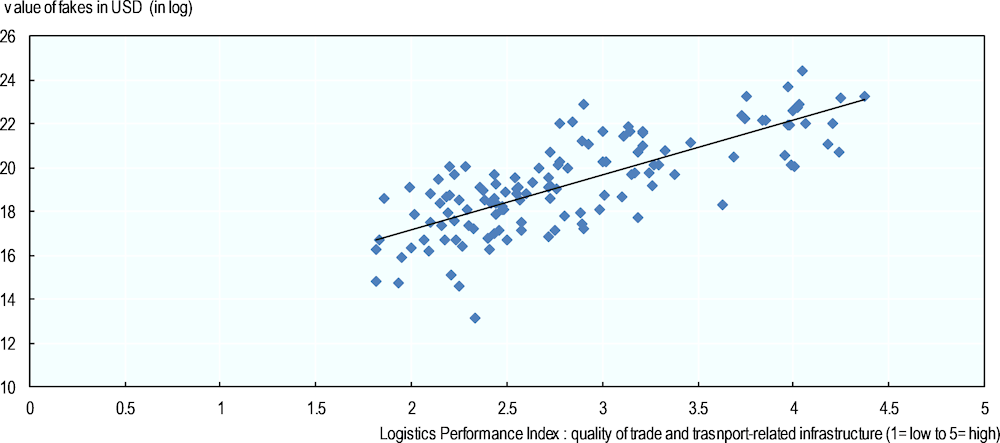

Infrastructure

As highlighted in previous OECD-EUIPO studies, good quality trade infrastructure tends to facilitate counterfeit imports to the same extent it facilitates licit trade. This is particularly the case for countries with relatively low governance standards related to IP respect and protection.

To verify if economies with efficient logistics are more likely to import counterfeit and pirated products, the study uses the Logistics Performance Index (LPI) provided by the World Bank and Turku School of Economics. The LPI is an interactive benchmarking tool updated every two years; it ranks 160 countries on the efficiency of their international supply chains. It is based on a worldwide survey of logistics professionals on the ground who provide feedback on the logistics friendliness of the countries in which they operate and those with which they trade. LPI is the combination of country scores on six dimensions : the ability to track and trace consignments, the level of competence and quality of logistics services (e.g. transport operators, customs brokers), the ease of arranging competitively priced shipments, the efficiency of customs clearance processes (i.e. speed, simplicity and predictability of formalities), how often the shipments to the assessed country reach the consignee within the scheduled or expected delivery time and the quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure (e.g. ports, railroads, roads, information technology). Scores are averaged across all respondents and all indices range from 1 to 5: the higher the score the better the performance.

In this study, the focus is the infrastructure quality dimension as it seems to be a determinant of imports of fakes. Indeed, Figure 2.6 shows a strong and positive correlation between the quality of trade and transport infrastructure and the value of fake imports.

Figure 2.6. Link between value of fake imports and quality of trade and transport infrastructure

Note: Each point corresponds to one country for 2019.

Source: World Bank (Logistics Performance Index) and OECD/EUIPO calculations.

Table 2.8 indicates that infrastructure is an important driver of counterfeit and pirated imports as the two columns show that an increase in quality of trade and transport related infrastructure significantly increase the value of fake imports. The quality of logistics and transport related infrastructure tends to facilitate counterfeit imports and in the framework of small parcels, infrastructure such as big airports are clearly considered as facilitating both genuine and illicit trade.

This result corroborates the trends already highlighted by the OECD and the EUIPO on counterfeiters’ strategies. Their strategies are multifaceted and consist in misusing all facilitation of international trade. For example, the misuse of containerized maritime, small parcels, free trade zones and online environment was already described in several publications1.

GDP per capita

A priori, the economic wealth of consumers can influence the purchase of counterfeit goods in several ways. It is important to recall that demand of fakes is specific as we distinguish two types of consumers. There are consumers who deliberately buy fake goods and those who buy fakes thinking the goods are genuine. On the one hand, people with low wealth may be motivated by lower prices in the illicit market. On the other hand, for people who are deceived, the purchase of counterfeit goods is not motivated by the price and consequently the role of economic wealth is less marked in this case.

The results of the multiple regression model (see Table 2.8) indicate that higher wealth per capita tend to reduce the value of fake imports. Ceteris paribus, an increase of the GDP per capita leads to a decrease of the value of counterfeit goods imported.

This result indicates that countries where wealth is lower are more likely to consume counterfeit and pirated goods which are often more attractively priced. Moreover, it can also be linked to the fact that countries with lower GDP per capita tend to pay less attention to IPR protection. In fact, as shown by several empirical studies, GDP capita is usually positively correlated with the overall quality of respect for IP in a country2 Consequently, this finding indirectly shows that countries that enjoy a higher respect for IP and stronger IP protection levels, also report lower volumes of import of fake goods.

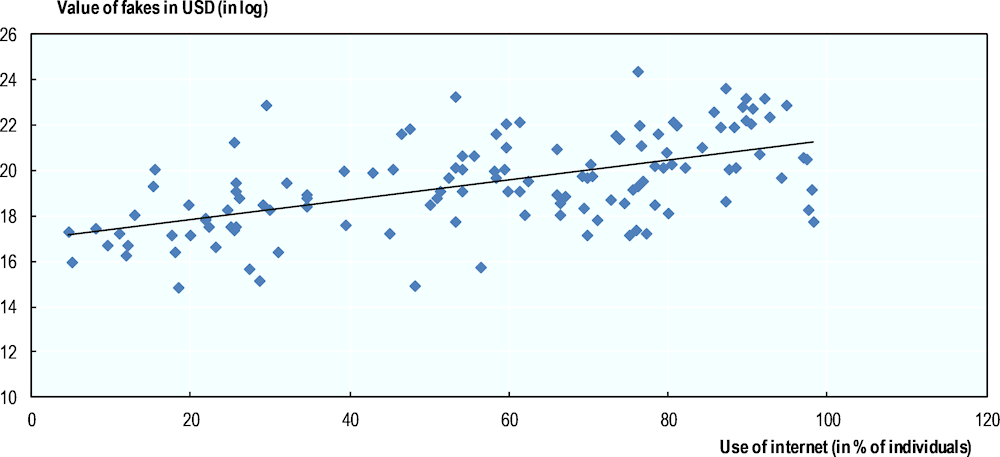

Use of internet

Figure 2.7 shows a positive correlation between the percentage of people using the Internet and the value of imports of counterfeit goods. Such a relationship is logical given the growing importance of online shopping for both genuine and counterfeit purchases. As highlighted in (OECD/EUIPO, 2021[36]), 56% of seizures made by European customs between 2017 and 2019 were related to online sales.

Figure 2.7. Link between the share of individuals using Internet and the value of fake imports

Note: Each point corresponds to one country for 2019.

Source: World Economic Forum and OECD calculations.

The regression model confirms (see Table 2.8) the positive relationship between the use of Internet and the value of fake imports. This result is not surprising since the online business is a complex and fast-moving environment where the consumer can be easily deceived. It is also a common way to serve the intentional demand for counterfeit goods through social media where the promotion and sale of replicas is made.

Population aged 65 and more

The relation between age and imports of fakes is a priori difficult to determine. On the one hand the relationship could be negative as studies show that young people are more likely to use counterfeit products than older people. On the other hand, the ageing countries are often developed countries that are well integrated in world trade and have a high import value.

The econometric model presented in Table 2.8 indicates that the age of the population is also a factor that impacts the value of imports of counterfeit goods. The results of the multiple regression indicate that an increase in the share of the elderly population (aged 65 and more) significantly decreases the value of imports of fakes. This result confirms the hypothesis that young people can be considered as the suitable target for bad actors supplying counterfeit goods.

The exact mechanism that reduces the overall propensity to import fakes with the share of elderly populations cannot be determined at this stage. In fact, several mechanisms could act independently. A greater awareness on the threat represented by counterfeiting as well as lower economic constraints for elderly (compared to younger people) may be elements of explanation. Last, less intense use of the Internet - which is a major source of counterfeit goods - by older people for their purchases may also explain such a relationship between the age of population and the value of imported fake goods.

Education

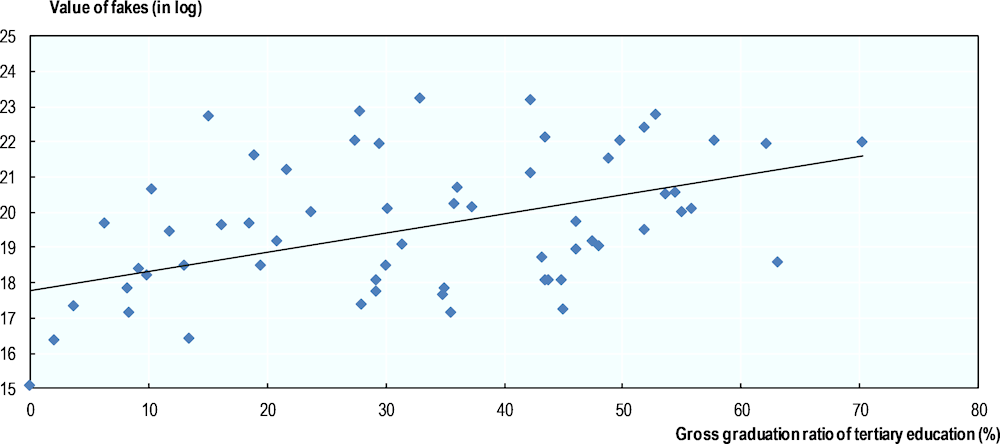

The data show a positive relationship between the gross graduation ratio of tertiary education and the value of imports of counterfeit goods. The multiple regression model confirms that an increase of the share of graduates from tertiary education leads to an increase in the value of fake imports (see Table 2.8).

More in-depth analysis is needed to explain this pattern, as several underlying facts could potentially explain such a relationship. Possible explanatory factors, include for example lack of awareness about this risk (including the presence of counterfeit goods in all sectors and not only in the fashion or luxury goods sectors), or higher digital skills that might result in a higher ability to look for bargains online

In addition, the evidence highlighted by the OECD in several previous reports indicate that criminals are very creative and use all possible means to deceive consumers. The specific case of fake medicines is illustrative. A priori, the purchase of fake medicines is less demand-driven than other sectors like clothing or leather items (see Table 1.1). However, a survey conducted by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) in 2020 reveals that nearly half of Americans (42%) are currently purchasing medications online and 45% of Americans erroneously believe all websites offering healthcare services/prescription medications to Americans via the Internet have been approved by the FDA or state regulators. This means that for some sectors the risk of counterfeiting is not so well-known, and the purchase of counterfeit goods can potentially be made by all people, those with high digital skills to look for good offers online.

Figure 2.8. Link between tertiary education and the value of fake imports

Note: Number of graduates from first degree programmes (at ISCED 6 and 7) expressed as a percentage of the population of the theoretical graduation age of the most common first-degree programme. Each point corresponds to one country for 2019.

Source: World Bank and OECD/EUIPO.

References

[15] Agarwal, S., & Panwar, S. (2016), Consumer orientation towards counterfeit fashion products: A qualitative analysis, IUP Journal of Brand Management.

[26] Baumol, W. (1990), Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive., Journal of Political Economy, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2937617.

[33] Becker, S. (1968), Crime and punishment: An economic approach, Journal of political economy.

[42] Besley T, G. (2010), “Property rights and economic development. In: Rodrick D, Rosenzweig M”, Handbook of development economics, 5th edn, pp. 4525–4595.

[35] Bhattacharjee, S., Gopal, R. D., & Sanders, G. L. (2003), “Digital music and online sharing: Software piracy 2.0? Communications of the ACM,”, Vol. 46 (7), 107–111.

[17] Bian, X., & Veloutsou, C. (2007), “Consumers’ attitudes regarding non-deceptive counterfeit brands in the uk and china.”, Journal of brand management, pp. 14, 211–222.

[22] Bian, X., Wang, K.-Y., Smith, A., & Yannopoulou, N. (2016), “New insights into unethical counterfeit consumption”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69 (10), pp. 4249– 4258.

[8] Cordell, V. V., Wongtada, N., & Kieschnick Jr, R. L. (1996), “Counterfeit purchase intentions: Role of lawfulness attitudes and product traits as determinants”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 35 (1), pp. 41–53.

[13] Craft, J. (2013), “A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011”, Journal of business ethics, Vol. 117, pp. 221–259.

[18] Eisend, M., Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza, V. (2017), “Who buys counterfeit luxury brands? a meta-analytic synthesis of consumers in developing and developed markets”, Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 25 (4), pp. 89-111.

[14] Elsantil, Y. G., & Hamza, E. G. A. (2021), “A review of internal and external factors underlying the purchase of counterfeit products.”, Academy of Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 20 (1), pp. 1–13.

[39] EUIPO (2022), Intellectual Property and Youth Scoreboard 2022, https://doi.org/10.2814/249204.

[38] EUIPO (2020), European Citizens and Intellectual Property : Perception, Awareness, and Behaviour 2020, https://doi.org/10.2814/788800.

[5] EUIPO, E. (2022), EU enforcement of intellectual property rights : results at the EU border and in the EU internal market 2021, European Union Intellectual Property Office, https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/observatory/documents/reports/2022_EU_enforcement_of_IPRs_2021/2022_EU_enforcement_of_IPRs_results_2021_FullR_en.pdf.

[20] Geiger-Oneto, S., Gelb, B. D., Walker, D., & Hess, J. D. (2013), ““buying status” by choosing or rejecting luxury brands and their counterfeits”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 41, pp. 357–372.

[37] Geiger-Oneto, S., Gelb, B. D., Walker, D., & Hess, J. D. (2013), “buying status” by choosing or rejecting luxury brands and their counterfeits, pp. 357–372.

[25] Gentry, J. W., Putrevu, S., & Shultz, C. J. (2006), “The effects of counterfeiting on consumer search.”, Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, Vol. 5 (3), pp. 245–256.

[40] Gould, D. (1996), “The role of intellectual property rights in economic growth”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 48/2.

[19] Grossman, G. M., & Shapiro, C. (1988), “Foreign counterfeiting of status goods.”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 103 (1), pp. 79–100.

[41] Haydaroğlu, C. (2015), “The relationship between property rights and economic growth: an analysis of OECD and EU countries”, DANUBE Law Econ Rev, Vol. 6(4), pp. 217–239.

[10] Hoon Ang, S., Sim Cheng, P., Lim, E. A., & Kuan Tambyah, S. (2001), “Spot the difference: Consumer responses towards counterfeits.”, Journal of consumer Marketing, Vol. 18 (3), pp. 219–235.

[28] Husted, B. (2000), “The impact of national culture on software piracy.”, Journal of Business Ethics,, Vol. 26 (3), pp. 197–211.

[11] Koklic, M. K., et al. (2011), “Non-deceptive counterfeiting purchase behavior: Antecedents of attitudes and purchase intentions.”, Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), Vol. 27 (2).

[30] Li, T., & Seaton, B. (2015), “Emerging consumer orientation, ethical perceptions, and purchase intention in the counterfeit smartphone market in china.”, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 27 (1), pp. 27–53.

[21] Liao, C.-H., & Hsieh, I. (2013), “Determinants of consumer’s willingness to purchase gray-market smartphones.”, Journal of business ethics, Vol. 114, pp. 409–424.

[27] Maskus, K. (2000), “Intellectual property rights in the global economy.”, Peterson Institute..

[29] Moores, T. (2008), “An analysis of the impact of economic wealth and national culture on the rise and fall of software piracy rates.”, Journal of business ethics, Vol. 81, pp. 39–51.

[4] OECD (2008), The economic impact of counterfeiting and piracy, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/sti/38707619.pdf.

[43] OECD/EUIPO (2021), Misuse of Containerized Maritime Shipping in the Global Trade of Counterfeits, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e39d8939-en.

[36] OECD/EUIPO (2021), Misuse of E-Commerce for Trade in Counterfeits, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c04a64e-en.

[1] OECD/EUIPO (2019), Trends in Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union Intellectual Property Office, Alicante, https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9f533-en.

[2] OECD/EUIPO (2018), Misuse of Small Parcels for Trade in Counterfeit Goods: Facts and Trends, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307858-en.

[44] OECD/EUIPO (2018), Trade in Counterfeit Goods and Free Trade Zones: Evidence from Recent Trends, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union Intellectual Property Office, Alicante, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264289550-en.

[3] OECD/EUIPO (2016), Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact, Illicit Trade, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252653-en.

[16] Penz, E., & Stöttinger, B. (2012), “A comparison of the emotional and motivational aspects in the purchase of luxury products versus counterfeits.”, Journal of Brand Management, Vol. 19 (7), pp. 581–594.

[7] Penz, E., & Stöttinger, B. (2008), “Original brands and counterfeit brands—do they have anything in common?”, Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review,, Vol. 7 (2), pp. 146–163.

[23] Penz, E., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Stöttinger, B. (2008), “Voluntary purchase of coun-terfeit products: Empirical evidence from four countries.”, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 21 (1), pp. 67–84.

[24] Poddar, A., Foreman, J., Banerjee, S. S., & Ellen, P. S. (2012), “Exploring the robin hood effect: Moral profiteering motives for purchasing counterfeit products”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 65 (10), pp. 1500–1506.

[34] Reardon, J., McCorkle, D., Radon, A., & Abraha, D. (2019), “A global consumer decision model of intellectual property theft.”, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing.

[31] Rod, A. (2015), “Economics of luxury: Counting probability of buying counterfeits of luxury goods.”, Procedia Economics and Finance, Vol. ,30, pp. 720-729.

[6] Rosen, S. (1974), “Hedonic Prices and Implicit Markets: Product Differentiation in Pure Competition”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 82, pp. 34-55, https://doi.org/10.1086/260169.

[32] Tom, G., Garibaldi, B., Zeng, Y., & Pilcher, J. (1998), “Consumer demand for counterfeit goods”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 15 (5), pp. 405–421.

[12] Turkyilmaz, C. A., & Uslu, A. (2014), “The role of individual characteristics on consumer’s counterfeit purchasing intentions : research in fashion industry”, Journal of Management, Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 1 (3), pp. 259–275.

[9] Wee, C.-H., Ta, S.-J., & Cheok, K.-H. (1995), “Non-price determinants of intention to purchase counterfeit goods: An exploratory study”, International Marketing Review.

Notes

← 2. (Gould, 1996[40]); (Besley T, 2010[42]) Besley T, Ghatak M (2010) Property rights and economic development. In: Rodrick D, Rosenzweig M (eds) Handbook of development economics, 5th edn. Elsevier, North Holland, pp 4525–4595; (Haydaroğlu, 2015[41]).