Upper secondary education is the most common level at which vocational education and training (VET) programmes are provided: on average, 69% of VET students (from upper secondary to short-cycle tertiary levels) pursue a programme at upper secondary level1. However, the importance of VET within the broader educational landscape varies widely across countries. This Spotlight analyses the diversity of upper secondary VET programmes and builds a typology of them across three dimensions: 1) the structure; 2) the share of students enrolled; and 3) the use of work-based learning (see Table 1. ).

Spotlight on Vocational Education and Training

A focus on upper secondary vocational education

How do VET systems differ in structure and importance?

The structure of upper secondary VET systems

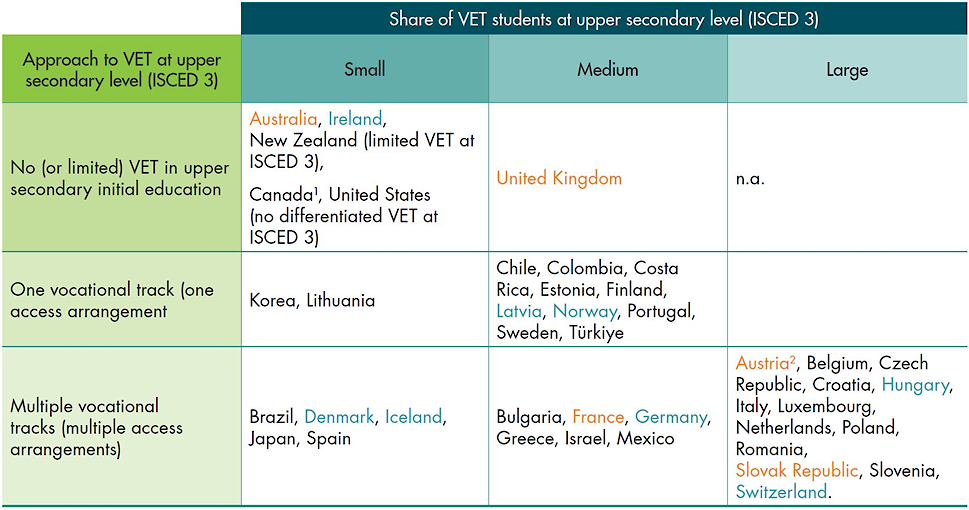

The first dimension of the typology refers to the structure and degrees of differentiation within upper secondary education systems. Approaches range from having no differentiated vocational tracks at all in initial schooling, to having a single vocational track, or having several vocational tracks.

Most OECD countries have differentiated vocational tracks in upper secondary education, including initial schooling. Some of these offer VET through a single main vocational track in initial education, alongside a general track. In these countries, the single vocational track yields direct access to tertiary education (Table 1. ).

Another large group of countries offer multiple vocational tracks in initial upper secondary education, some of which lead to tertiary education and some of which do not. The vocational tracks with direct access to tertiary education will have a stronger element of general education (and thus help prepare students for further studies), while others will focus more on preparation for an occupation. For example, Mexico offers a technological baccalaureat with access to tertiary education, and technical professional programmes without. In Hungary five-year technikum programmes yield access to tertiary education, but three-year vocational programmes do not. In France the bac professionnel gives access to tertiary education, while Certificat d'aptitude professionnelle (CAP) programmes allows students who so wish to continue their studies towards a vocational baccalaureate once they have obtained their diploma. Among the 2020 CAP graduates (school-based route), 56% have continued their studies within 6 months after graduation (DEPP, 2022).

In a small group of countries, there is no or limited VET in initial upper secondary education. For instance, in some anglophone countries such as New Zealand and the United Kingdom, vocational programmes are mostly offered to students who have completed their initial schooling (although they are still at upper secondary level). For example, New Zealand has a generally oriented school system with one predominant upper secondary programme and most formal VET is offered after this initial schooling, at upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary or short cycle tertiary levels.

Finally, in Canada (except for the province of Quebec) and the United States, VET is not offered as a separate programme at upper secondary level. Instead, vocational learning is typically integrated, available in the form of individual or clusters of optional courses. In such undifferentiated upper secondary (high school) programmes, there is no single decision point when students choose between a vocational or general pathway, as they continue to take courses with a general focus at the same time as pursuing vocational ones. While these vocational courses aim to prepare students’ transition from school to the labour market or to further vocational studies, all students receive the same qualification and have access to the same higher level learning opportunities, regardless of whether they took vocational courses or not. Vocational learning in undifferentiated systems is not reported in comparative data. For these countries only VET students at post-secondary and tertiary levels can be identified.

Table 1. Approaches to VET provision in initial upper secondary education (2021)

Note: Table only includes programmes leading to full completion of upper secondary education (ISCED 3). The share of upper secondary VET students enrolled in VET is measured here by the percentage of upper secondary students aged 15-19 who pursue a vocational programme (small – up to 25%; medium – 25-49%; large – 50% or more). A country is considered as having multiple vocational tracks if there are at least two tracks (programmes associated with a particular access arrangement) with at least 5% of upper secondary VET students in each.

Colours indicate the share of VET students pursuing combined school- and work- based programmes. Green – 50% or more; grey – 25%-49%; not highlighted – less than 25%.

1. In Canada, VET is offered in the province of Quebec.

. In Austria programmes in BHS schools span levels ISCED 3 and 5 and are considered here as yielding direct access to ISCED 6.

Source: (Kis, forthcoming[2]), Indicator B1 and OECD ISCED mappings (2022).

Participation among 15-19 year-olds

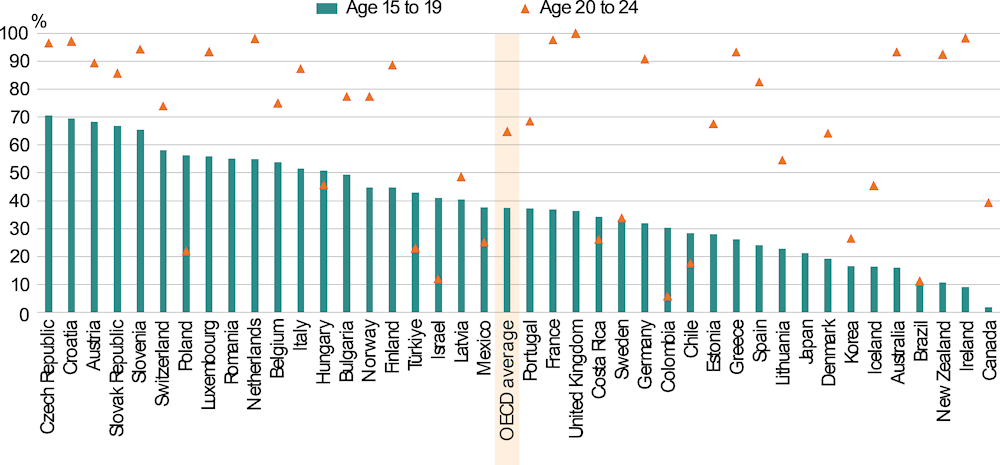

The second dimension of the typology gauges the weight of VET in initial upper secondary education by considering the shares of 15-19 year-olds upper secondary students enrolled in vocational and general education (recognising that some students in this age group will still be in lower secondary education, while others might have completed their upper secondary studies).

On average, 37% of all upper secondary students aged between 15 and 19 are pursuing a vocational programme, but this figure conceals major disparities between countries (Figure 2. ). There are 13 countries where VET is the main initial upper secondary education pathway. In these countries, more than 50% of upper secondary students aged 15-19 are enrolled in vocational programmes (Table 1. ). All but one of these countries offer multiple vocational tracks in the sense that different types of vocational programmes have differences in eligibility to higher levels of education (Figure 11. ). This approach allows education systems to accommodate the diverse needs of a large group of students who are more heterogenous in their learning needs, aspirations and interests than in countries where VET serves a smaller share of students.

The largest group of countries (17 countries) have medium-sized VET systems at upper secondary level, with 25% to 49% of upper secondary students enrolled in VET. Of these, two-thirds have one vocational track, which always yields direct access to tertiary education. For example, in Chile and Estonia, VET enrols 28% of 15-19 year-olds at this level in programmes that are predominantly school-based. In Norway, 45% of 15-19 year-old upper secondary students are enrolled in VET, a majority of them in the 2+2 school apprenticeship model (i.e. two years of school and two years of apprenticeship) and the others are in variants of it (OECD, 2022[3]). France, Germany and Mexico offer more than one track in initial VET, which enrol over 30% of 15-19 year-old upper secondary students. In Germany, the average entrance age to vocational training is 20 years, and around 30% of new entrants have a higher education entrance qualification. The United Kingdom reports 36% of 15-19 year-olds upper secondary students are in VET, enrolled in post-school settings (e.g. further education colleges, which serve learners aged 16 and over).

Figure 2. Share of upper secondary students enrolled in vocational programmes, by age groups (2021)

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of 15-19 year-olds students in 2021.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en,, Table B1.2.

The remaining 12 countries – where less than one-quarter of 15-19 year-olds upper secondary students are enrolled in VET (or where no VET is reported) – take a mix of approaches. For example, Korea and Lithuania offer a single vocational track but several other countries offer multiple vocational tracks (Table 1. ). Finally, some English-speaking countries report low enrolment in VET at school either because VET is delivered in post-school contexts and/or is offered in non-differentiated programmes. Canada (where both English and French are official languages) reports that only 2% of its 15-19 year-olds upper secondary students are in vocational education as differentiated programmes are only offered in the province of Quebec. The United States reports no enrolment in upper secondary VET, as there are no differentiated vocational programmes in high schools. In Ireland 9% of 15-19 year-olds upper secondary students are pursuing VET, also in post-school contexts (e.g. traineeships, second chance programmes or learning opportunities for marginalised learners), while much of its vocational provision is offered at higher levels (such as apprenticeships and post-leaving certificates at post-secondary non-tertiary level).

The use of work-based learning

A third dimension differentiating VET systems concerns the use of work-based learning. Including an element of quality work-based learning in vocational programmes has multiple benefits. Workplaces are powerful environments for the acquisition of both technical and socio-emotional skills. Students can learn from experienced colleagues, working with the equipment and technology in use in their field. It is also easier to develop soft skills like conflict management in real life contexts than in classroom settings. Delivering practice-oriented training in work environments can reduce the cost of training in schools, as equipment is often costly and quickly becomes obsolete. Including a strong element of work-based learning in VET can also help tackle teacher shortages. Finally, work-based learning creates a link between schools and the world of work, as well as between students and potential employers (OECD, 2018[4]).

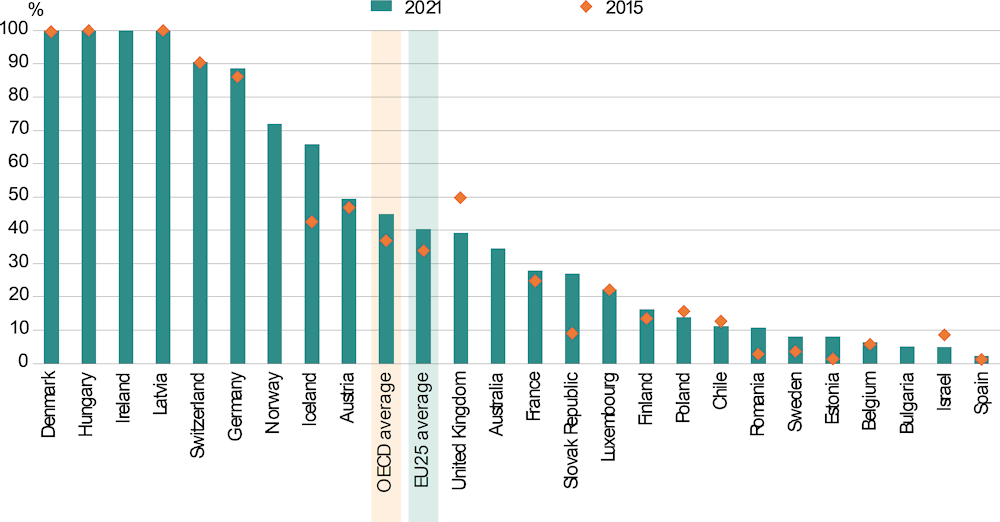

Despite these numerous labour-market advantages, only 45% of all students in upper secondary vocational education are enrolled in programmes with a substantial work-based element on average across OECD countries (Figure 3. ). However, looking only at countries with data for 2015 and 2021, enrolment in upper secondary programmes combining school- and work-based learning increased from 37% to 40%.

Figure 3. Share of upper secondary vocational students enrolled in combined school- and work-based programmes (2015 and 2021)

Note: The work-based component is between 25% and 90% of the curriculum in combined school and work-based programmes. These programmes can be organised in conjunction with education authorities or institutions.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of students in combined school- and work- based programmes in 2021.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en,, Table B1.3 (2015 in web column).

The use of work-based learning in vocational programmes varies widely between countries. Figure 3. shows the share of students in programmes that involve at least 25% work-based learning. In six countries, at least 85% of VET students pursuit these kinds of programmes2. In a large group of countries, both school-based and combined school- and work-based programmes have a substantial presence, while in seven countries less than 10% of students pursue combined school- and work-based VET.

Some countries with a small share of students in combined school- and work-based programmes are making efforts to expand the use of work-based learning. Some, such as Estonia and Romania, and in a lesser extent Spain, have seen the number of students enrolled in such programmes rise sharply since 2015 following reforms. Romania has strengthened the work-based programmes since 2015 and introduced the dual VET pathway in 2017, expanding from less than 5% of students in 2015 to more than 10% in 2021. Estonia has sought to improve transitions to the labour market by developing work-based learning and by clarifying the qualifications system. New regulations in Spain have sought to strengthen the links between companies and VET providers, and to increase the work-based learning component. Sweden has been expanding apprenticeships, increasing the share upper secondary vocational students taking part in them from less than 4% in 2015 to 8% in 2021 (Figure 3. ).

More generally, apprenticeships and other forms of work-based learning have received a great deal of attention from policy makers, and about two-thirds of countries with available data have implemented recent reforms to strengthen the quality of their combined school- and work-based programmes. The nature of these reforms differs across countries. Some have strengthened their apprenticeship training and other forms of work-based learning. For some countries (Australia, Belgium, Chile, Finland, France, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Korea, Norway and the United Kingdom) this meant creating new places in apprenticeship programmes. Some countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Hungary and Korea) have focused additional attention on public support for students to access VET and on the provision of financial incentives to enterprises taking part (Indicator B7 of (OECD, 2020[5]), (OECD, 2018[4]) and Box 1).

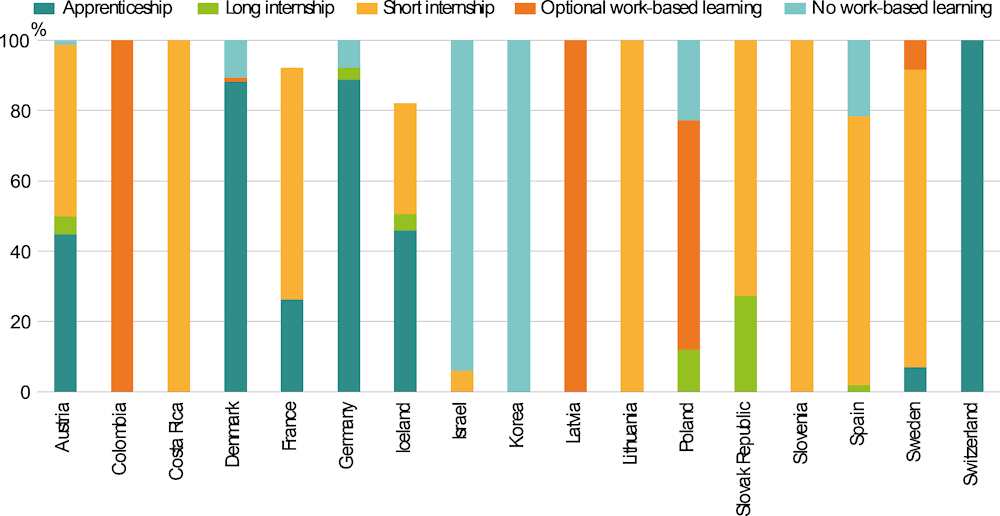

Programmes that do not fit the definition of “combined school- and work-based” may still include shorter forms of work-based learning, accounting for less than 25% of the programme’s duration. For 16 countries there are more fine-grained data available (see Figure 4), enabling programmes to be broken down into the following categories:

apprenticeships: work-based learning is mandatory, accounts for at least 50% of the curriculum and is paid;

long internships: work-based learning is mandatory and accounts for 25% to 49% of the curriculum;

short internships: work-based learning is mandatory and accounts for less than 25% of the curriculum;

optional work-based learning: work-based learning is an optional part of the curriculum;

no work-based learning as part of the curriculum.

Figure 4. Distribution of students enrolled in upper secondary vocational programmes by type of work-based learning (2021)

Note: Numbers may not add up to 100 if information on the type of work-based learning was not available for some programmes. For France data on the type of work-based learning are limited to CAP and baccalauréat professionel. In Sweden apprenticeships are unpaid.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en,, Indicator B1 and OECD ISCED mappings (2022).

Apprenticeships are the dominant form of upper secondary VET in Denmark, Germany and Switzerland but in other countries programmes with different types of work-based learning co-exist. In France, for example, upper secondary vocational qualifications may be acquired either through an apprenticeship or through a school-based route with a short internship. In Austria, upper secondary VET includes both apprenticeships and programmes in higher technical and vocational colleges with short internships. Short internships are dominant in several countries, including Costa Rica, Lithuania, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.

How do VET systems compare in terms of equity?

Across OECD countries, there is increasing interest in the development of vocational upper secondary programmes as a means of equipping young people with the skills they need to enter the labour market. Completing a vocational programme offers improved employability compared to a general qualification at the same level. However, vocational education may also raise questions of equity, particularly if the decision to enrol in a vocational programme is determined primarily by students' socio-economic background or gender, or if these streams have a very high share of those students with academic difficulties. While vocational programmes should provide an alternative to academic programmes for those who struggle or are less interested academically, it should be a pathway that works for everyone – including those with strong academic performance.

Enrolment by students’ socio-economic background

Students from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to be over-represented in vocational education in most countries with available data. This is partly driven by selection and self-selection mechanisms that shape enrolment in upper secondary education. Half of the countries that participated in the 2022 OECD Survey of Upper Secondary Completion Rates report that students’ choices (i.e. of whether they can enrol in vocational or general education) are limited by their school performance (e.g. grades in lower secondary education). Performance in an external examination is a factor in nine countries, and teacher or school recommendations matter in seven countries. Finally, in four countries the type of lower secondary education a student has pursued limits their upper secondary options. Only 6 out of 30 countries report that students’ choice of upper secondary programme was entirely unconstrained. As school performance is correlated with socio-economic background, this means that students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to pursue vocational programmes. Aspirations also differ, which calls for strong counselling/guidance. Effective VET systems need to serve learners of all backgrounds and avoid being a vehicle for social segregation. The challenge is to ensure that students pursue VET because it suits their interests and abilities, and not because of their personal circumstances, which they cannot influence.

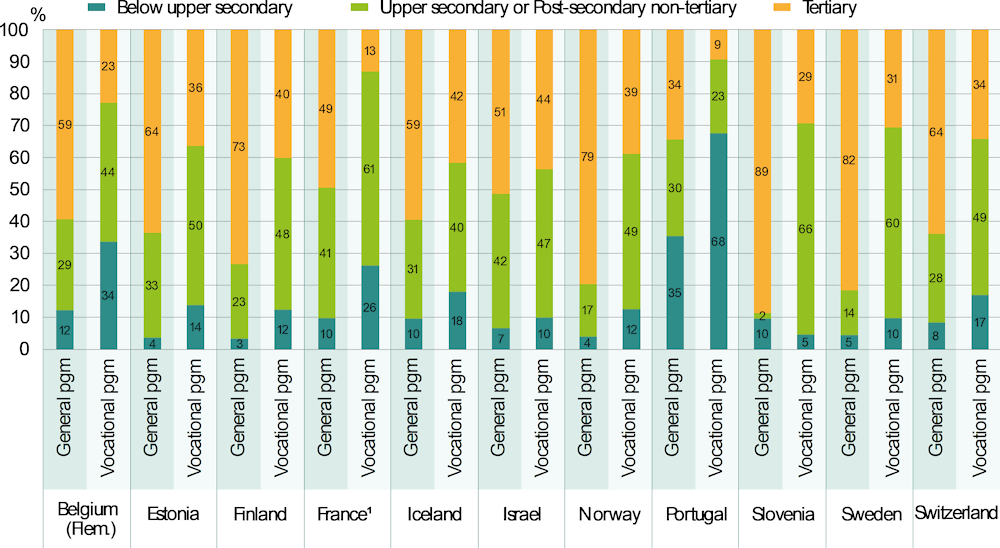

Figure 5. shows the breakdown of students in general and vocational programmes by parents’ educational attainment. In all countries with available data except Slovenia, students whose parents have lower educational attainment are substantially over-represented in vocational programmes. In nearly every country, the share of students whose parents have not attained upper secondary education is at least twice as high among entrants to vocational programmes as among entrants to general programmes. The gap is even more striking at the other end of the spectrum, when considering students with at least one tertiary-educated parent. In Portugal, for example, students with at least one tertiary-educated parent make up 34% of those in general programmes, but only 9% of those in vocational ones.

Figure 5. Share of entrants to upper secondary initial education, by programme orientation and parents’ educational attainment (2022)

Note: Data did not take into account students for whom the parents' level of education is unknown.

1. Year of reference 2017.

Source: Education at a Glance database, INES survey on upper secondary completion rates.

Enrolment by gender

Enrolment patterns in VET also vary by gender, and in different ways at upper secondary and higher levels of VET. Overall men are more likely to pursue VET than women. On average across OECD countries, 45% of students enrolled in upper secondary vocational programmes are female. Only in about one-quarter of the 44 countries with available data female students account for the majority. There is, however, significant variation across countries: the share ranges from less than 38% in Germany, Greece, Iceland, India, Italy and Lithuania to over 55% in Brazil, Costa Rica and Ireland.

The pattern changes when looking at post-secondary non-tertiary education. At this level, more than 53% of students are women. They account for the majority of enrolment in most of the countries with available data. It should be noted that although the proportion of women in vocational courses at upper secondary level is low in Germany, they account for 55% of students enrolled in post-secondary non-tertiary programmes, and a very large majority of those enrolled in the health and welfare sector at this level.

The same applies to short-cycle tertiary, but the trend is less pronounced. On average in OECD countries, women account for 52% of all students enrolled at this level and make up more than 50% in about two-thirds of countries for which data are available. However, there are wide variations between countries, with the share of female students in short-cycle tertiary programmes ranging from less than 30% in Italy and Norway to 65% or more in Brazil, Germany, Poland and the Slovak Republic.

There are two main reasons that may explain the under-representation of women in upper secondary vocational education but not in post-secondary education. First, women have higher upper secondary VET completion rates than men and are therefore more likely to continue their studies in post-secondary education. Second, women are more strongly represented in certain broad fields of study such as health and social welfare, and business, administration and law – fields which are very prevalent in short-cycle tertiary vocational education, and especially so in post-secondary non-tertiary education. They represent, for example, 77% of the students enrolled in short-cycle tertiary in Germany in the field of health and welfare. In contrast, the share of women in short-cycle tertiary education tends to be lower in countries where science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields are prominent at this level (Indicator B7, (OECD, 2020[5])).

Several countries have recently implemented reforms to reduce the gender gap in some fields, and are also seeking to widen the talent pool in particular sectors. Thus, some countries provide financial incentives to apprentices from the under-represented gender or to employers taking on these apprentices. In Ireland, for example, employers are eligible for a bursary for every female craft apprentice registered. This bursary has recently been expanded to all programmes where one gender accounts for more than 80% of students. In Canada, the Apprenticeship Incentive Grant for Women helps female apprentices pay for expenses while they train as an apprentice in a designated trade sector where women are under-represented ( (OECD, 2022[6]), (OECD, 2023[7])).

Enrolment of older students

The average age of vocational students (21 years old) is higher than for students of general programmes (17 years old). In Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland and Spain, the average age of students in upper secondary level vocational programmes is between 25 and 28; in Australia, Ireland and New Zealand it is over 30.

On average across OECD countries, about two-thirds of 20-24 year olds upper secondary level students are in VET programmes (Figure 2. ). Relatively high enrolment rates in these programmes among this older age group are explained in some countries by the fact that some VET programmes serve those who seek to re-skill or upskill, or complete upper secondary schooling if they did not do so at a younger age. This includes participation in second-chance programmes and other forms of adult education, as is the case in Finland, Luxembourg. In Australia and New Zealand upper secondary enrolment among 20-24 year-olds is predominantly vocational. This reflects the fact that in these countries initial schooling is largely general and VET is typically pursued after the completion of upper secondary education to satisfy different needs at different stages of people’s lives, whether they are preparing for a first career, seeking additional skills to assist in their work or catching up on educational attainment, but also to help students to develop work-relevant skills and to wider their career choices.

How do completion patterns vary in upper secondary VET?

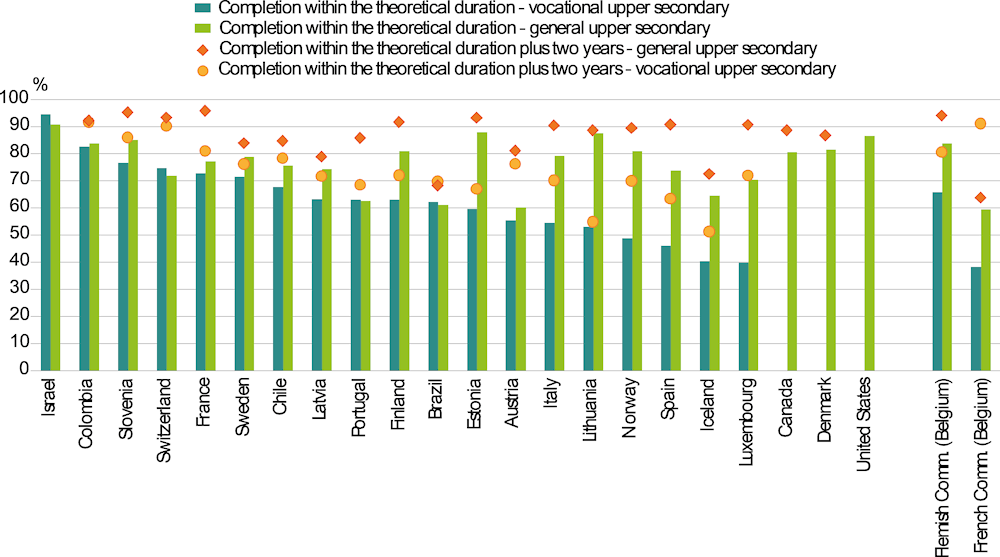

Completion rates in general and vocational programmes

Ensuring that all students complete their upper secondary education is a challenge in several countries, especially in vocational programmes. In most countries, the completion rate of upper secondary education (within the theoretical duration of the programme) is lower among students enrolled in vocational education (62%) than among those in general education (77%). These averages mask wide differences across countries. Less than 50% of vocational upper secondary students in Iceland, Luxembourg, Norway and Spain complete their studies by the end of the theoretical duration. After a further two years, however, completion rates are higher and exceed 70% in Luxembourg and Norway. In contrast, in some countries, completion rates among vocational students exceed 70% at the end of theoretical duration. There is much less cross-country variation in the case of general programmes. Completion rates in general upper secondary education exceed 70% everywhere except in Austria, Brazil, the French Community of Belgium, Iceland and Portugal (Figure 6. ).

Figure 6. Upper secondary completion rates, by timeframe and programme orientation on entry (2021)

Note: The data presented here come from an ad-hoc survey and only concern initial education programmes. The reference year (2021, unless noted otherwise) refers to the year of graduation by the theoretical duration plus two years.

1. Year of reference differs from 2021. Refer to the source table for more details.

Countries and other participants are ranked in descending order of the completion rate within the theoretical duration of vocational upper secondary students.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en,, Table B3.1.

The completion gap between general and vocational programmes is partly driven by selection or self-selection. Students with weaker school performance and/or motivation are often guided into or opt for vocational programmes. However, unlike most countries, in Brazil, Israel, Portugal and Switzerland, completion rates are higher for students in vocational programmes. In Brazil, public vocational schools are viewed as high-status institutions and face excess demand; many of their graduates continue to higher education (OECD, 2022[8]). In Switzerland, where the VET system is based on apprenticeships, shorter programmes have been developed for youth at risk of dropping out and there are various targeted measures to support completion (OECD, 2018[4]). Another reason for lower completion rates in vocational education is that learners may already accept a job in their training company (or a related one) before finishing their studies.

Completion rates by type of vocational programme

Several countries provide data on completion patterns in different vocational tracks, distinguishing between programmes with or without direct access to tertiary education. In nearly all countries with available data, students who entered programmes without direct access to tertiary education are less likely to complete them than their peers in programmes which do offer such access. In Italy, for example, 53% of students who entered a vocational programme without direct access to tertiary education will have completed their studies two years after the theoretical duration, compared to 71% of those in programmes with direct access. The only exception is Latvia, where the completion rates are 85% for programmes without direct access, and 70% for those with. The difference in completion rates varies considerably across countries, ranging from 21 percentage points in Austria to only 4 percentage points in Slovenia.

The different completion rates between programmes with or without direct access to tertiary education also reflects a combination of selection and self-selection into the programmes. Among countries offering multiple vocational tracks at upper secondary level, programmes with direct access to tertiary education tend to place more emphasis on general content and preparation for further studies. Students with weaker lower secondary school grades and those who are less interested in school-based forms of learning are more likely to choose or be guided towards vocational programmes without direct access to tertiary education, as these tend to have a stronger focus on occupational skills and a lighter academic workload. Some programmes in this category were explicitly designed for youth at risk of dropping out.

Completion rates of general and vocational programmes by gender

Male students are less likely than their female peers to complete upper secondary education. In nearly all countries with available data, female students have higher upper secondary completion rates than male students. This holds for both vocational and general programmes, with Lithuania and Sweden being the only exceptions for vocational programmes. On average, the gender gap (within the theoretical duration) in general programmes is 7 percentage points, while it is 6 percentage points in vocational programmes. The gender gap in completion rates is consistent for both timeframes (within the theoretical duration and plus two years), although the gap narrows slightly two years after the theoretical duration, indicating that male students, especially when they are enrolled in vocational programmes, are more likely to delay graduation.

Countries show different patterns when it comes to gender gaps in completion rates by programme orientation. The gender gap is wider for vocational programmes in some countries and in general programmes for others. For example, in Norway the gender gaps in completion rates are 20 percentage points for vocational and 7 percentage points for general programmes, and in Spain they are 11 percentage points for vocational programmes and 8 percentage points for general ones. On the other hand, in both Brazil and Israel, the gender gap for general programmes is more than 10 percentage points but less than 5 percentage points for vocational programmes.

What are the labour-market benefits of holding an upper secondary vocational qualification?

Strong vocational programmes need to ensure that graduates are able to find employment and pursue successful careers. Data on outcomes associated with vocational qualifications can shed light on this, but with an important caveat: the difficulty of establishing a suitable point of comparison. Selection and self-selection drive participation in different types and levels of education. As a result, young people who complete tertiary education have different profiles overall in terms of skills and interests from those who hold a vocational qualification as their highest level of education. Comparing VET graduates to general education graduates at the same level is also challenging, as general programmes are not designed to prepare for labour-market entry and the large majority of general education students continue to tertiary education. Comparison to those who leave the education system without an upper-secondary degree may suggest that the alternative to VET is dropping out, which is setting the bar too low.

Employment

High-quality VET programmes can be effective at developing the skills students need to ensure a smooth and successful transition from school into the labour market. Failing to support transition into jobs is also costly – a large share of youth who are neither employed nor in education or training (NEET) involves significant social and economic costs (Mawn et al., 2017[9]).

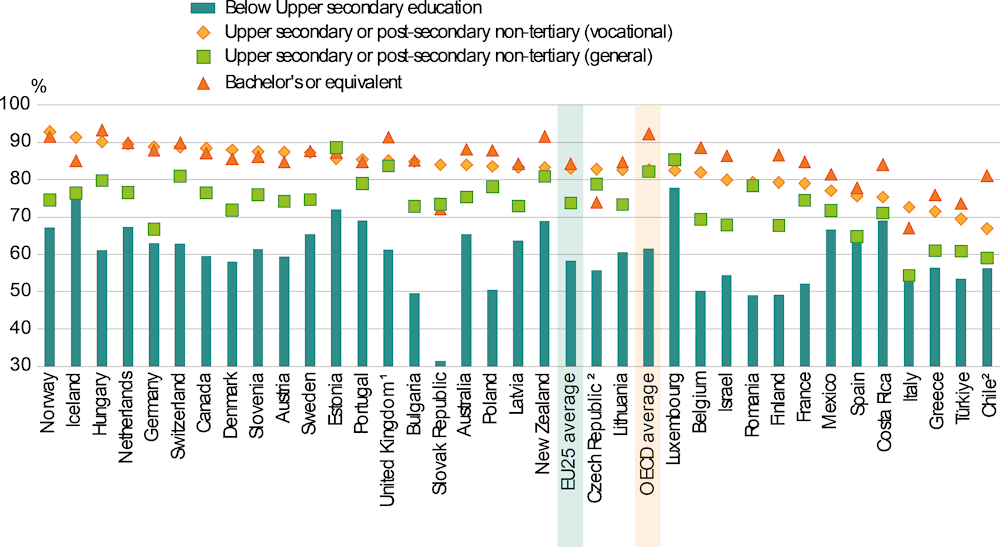

Holding a vocational upper secondary qualification is associated with higher employment rates than holding a general qualification at the same level or lacking an upper secondary qualification altogether. This potential to facilitate school-to-work transition has been a factor behind increasing policy attention to VET over the last decade (see Box 1). The average employment rate among 25-34 year-old adults is 62% for those without upper secondary education and 83% for those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary vocational education as their highest attainment.

In OECD countries, the employment rate among younger adults whose highest attainment is upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education is about 10 percentage points higher for those with a vocational qualification than for those with a general qualification. The employment rate of those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary vocational education has increased by an average of 3 percentage points between 2015 and 2022 (Figure 7).

Gender gaps in employment persist in virtually all countries, for both general and vocational programmes. On average across OECD countries, 74% of 25-34 year-old women with a vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary programme as their highest level of educational attainment are employed, against 89% of their male peers. These gaps are similar to those observed in general upper secondary programmes, where employment rates are 80% for men and 66% for women.

Figure 7. Employment rates of 25-34 year-olds, by educational attainment and programme orientation (2022)

1. Data for upper secondary attainment include completion of a sufficient volume and standard of programmes that would be classified individually as completion of intermediate upper secondary programmes (9% of adults aged 25-34 are in this group).

2. Year of reference differs from 2022. Refer to the source table for more details.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the employment rates of 25-34 year-olds with vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en, Table A3.2.

Upper secondary VET graduates are less likely to continue in education than their peers from general programmes. On average across OECD countries, 29% of 25-29 year-olds with general upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment are in education, the rest are either employed (55%) or NEET (around 17%). Those with vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment are much less likely to be enrolled in education (only 9% on average) while 75% are employed and around 17% NEET.

Attaining upper secondary vocational education or post-secondary non-tertiary education also reduces the risk of unemployment. In most OECD and partner countries, among young adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment, those with a vocational qualification have a lower risk of unemployment than those with a general one, although the average difference across OECD countries remains small (about 2 percentage points). The differences in unemployment rates are most pronounced in Costa Rica, Finland and the Netherlands, where they reach 5-7 percentage points.

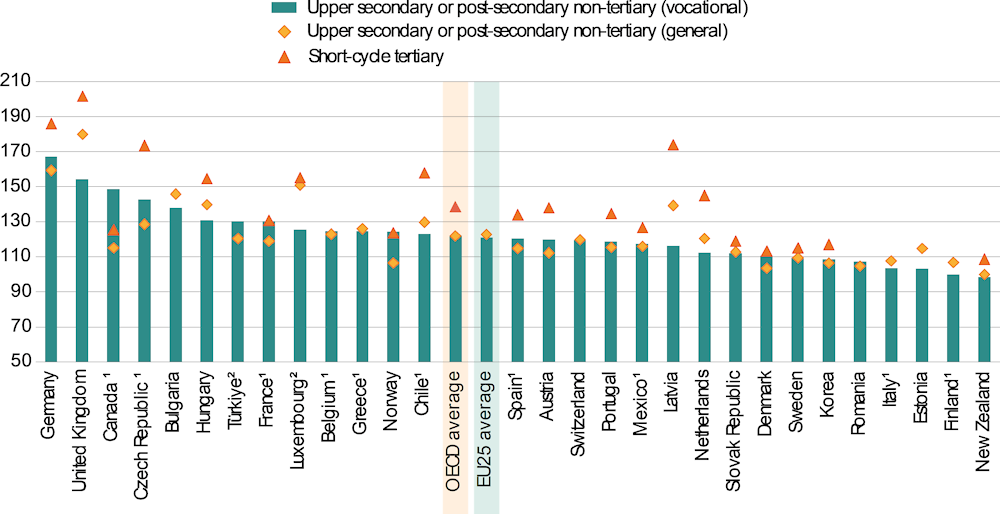

Earnings

The earnings benefits associated with holding a vocational qualification can vary widely. The differences between countries also reflect the fields offered in VET - some fields have much higher incomes than others (OECD, 2020[10]). It is also important to bear in mind that in many countries only a small group of adults have general upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment, while VET graduates form a much larger group. In more than half of OECD, partner and accession countries with available data, young adults with a general upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment earn more than those with vocational attainment at that level. Although the difference in earnings is small or even negligible in most cases, it is over 10% in Latvia, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom. In contrast, young adults with a vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment earn 10% more than their peers with a general qualification in the Czech Republic and Norway, and the difference reaches almost 30% in Canada (Figure 8. ). It should be noted that in Canada, there is no differentiated vocational track at upper secondary level outside of Quebec and differentiated occupational preparation starts at post-secondary non-tertiary level. The earnings advantage from vocational qualifications in Canada is therefore not fully comparable with those advantages in other countries where upper secondary vocational education exists.

On average across OECD countries, young adults who attained short-cycle tertiary education earn 14% more than those with vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment. The earnings advantage is greatest in Latvia (50%) and the United Kingdom (31%).

Although the earnings difference by programme orientation is small or even negligible among young adults in most OECD, partner and accession countries, the gap widens among 45-54 year-olds, usually in favour of those with a general qualification. On average across OECD countries, 45-54 year-olds with vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment earn 6% less than those with a general qualification at the same level. This difference is about 40% in Finland and Luxembourg and is still above 10% in favour of those with a general qualification in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. In contrast, in Brazil, Canada and the Czech Republic, 45-54 year-olds with a vocational qualification earn at least 10% more than those with a general qualification.

Figure 8. Relative earnings of workers compared to those with below upper secondary attainment, by educational attainment and programme orientation (2021)

Note: There are cross-country differences in the inclusion/exclusion of zero and negative earners.

1. Year of reference differs from 2021. Refer to the source table for more details.

2. Earnings net of income tax.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the relative earnings of 25-34 year-olds who attained vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en, Table A4.4.

Box 1. Recent vocational education and training reforms to facilitate the transition from school to work

Vocational education and training (VET) has the potential to facilitate students’ transition from school to work, prepare them for higher level studies and provide adults with opportunities to improve their skills or change careers. Seeking to realise their VET systems’ full potential, many countries have recently changed their policies and have implemented significant reforms since 2013. For example, these have aimed at:

1. improving the overall quality of VET programmes by updating curricula and improving the quality of teachers;

2. supporting students’ transitions after graduation from upper secondary education into post-secondary non-tertiary or tertiary education or the labour market;

3. improving access to VET and its attractiveness to students and employers;

4. strengthening apprenticeship systems by increasing the number of places available and encouraging employer engagement (OECD, 2018[11]; OECD, 2018[4]).

Several countries have introduced reforms to improve the labour-market relevance and quality of existing VET and adult learning provision (OECD, 2022[6]), with an emphasis on strengthening co-operation with employers and industry:

In the Republic of Türkiye, the Ministries of National Education and of Industry and Technology signed in 2021 a co-operation protocol to strengthen links between VET institutions and regional hubs that bring together representatives from different employment sectors. The protocol aims to facilitate institutional collaboration for curriculum planning.

Greece began a broad reform of VET and lifelong learning systems based on three core pillars: integrating strategic planning for VET and lifelong learning; enhancing the alignment of education and training pathways with the real needs of the labour market through collaboration with social partners; and upgrading the structures, procedures, curricula and certification of initial and continuing education. At the national level, a newly established Central Council for Vocational Education and Training conducts analysis of labour-market developments and makes recommendations for updates to VET courses, curricula and infrastructure. At the regional level, Production-Labour Market Liaison Councils identify gaps in VET and adult learning provision and develop proposals based on local skill needs.

In Germany, the amendment of the German Vocational Training Act (Berufsbildungsgesetz - BBiG) in 2020 strengthened and modernised higher vocational education and training. In order to reinforce vocational upskilling, consistent higher vocational education and training levels have been introduced that stress the equivalence of vocational qualifications (Bachelor Professional, Master Professional) to academic bachelor’s and master’s degrees and render vocational degrees internationally comparable. In addition, in order to provide a new boost to initial, further and continuing training and professional reorientation, Germany has started the Excellence Initiative for Vocational Education and Training in December 2022. The Excellence Initiative for Vocational Education and Training is intended to raise the attractiveness of vocational education and training for all young people. In addition, it places a special focus on young people who can choose between different training paths (training in the dual system, trade and technical school, higher education study).

France has been strengthening its upper secondary vocational pathways since the Act for the freedom to choose one’s future career in 2018, with the aim of making the VET sector more attractive, more efficient and better oriented towards the needs of an evolving labour market. The reform aims to improve the support, guidance and opportunities available to vocational students by fostering greater collaboration between a variety of actors. This work builds on the Job Campuses (Campus des métiers et qualifications) established since 2013, which aimed to open up VET institutions to establishing stronger links with higher education and research institutions, other training providers, and economic actors at local level. The September 2018 also provides 5 main measures for apprenticeship in France, namely:

Revaluation of the remuneration for 16-20 year-olds + €500 aid for young people aged 18 or over who wish to take the driving test.

Better information for young people and their families on the quality of apprenticeships available to them.

All apprentices whose employment contract is interrupted during the year will no longer lose their year spent in the VET programme.

Apprenticeships will be open to young people up to the age of 30, instead of 26.

All work-study contracts are financed, in all sectors, whatever the size of the company.

New Zealand passed legislation in 2020 providing major reforms of vocational education. These are intended to bring together industry and educators into a single vocational education system, increasing collaboration and consistency of provision, and increasing availability of workplace-based experiences for students.

Romania introduced in 2017 the dual VET pathway, at the demand and with the active involvement of employers and industry.

Source: (OECD, 2022[6]) , Education Policy Outlook 2022: Transforming Pathways for Lifelong Learners, https://doi.org/10.1787/c77c7a97-en.

How is VET resourced?

Expenditure

Obtaining accurate and comprehensive expenditure data for VET poses various challenges across OECD countries. Different institutional settings imply that funding sources and flows as well as their importance in overall funding differ strongly between countries. Moreover, various country specific challenges in reporting VET expenditure may affect the comparability of VET expenditure statistics. Additionally, the level of expenditure on VET varies greatly across countries, depending on the amount of work-based learning and how it is captured by data, making it sometimes difficult to interpret the data.

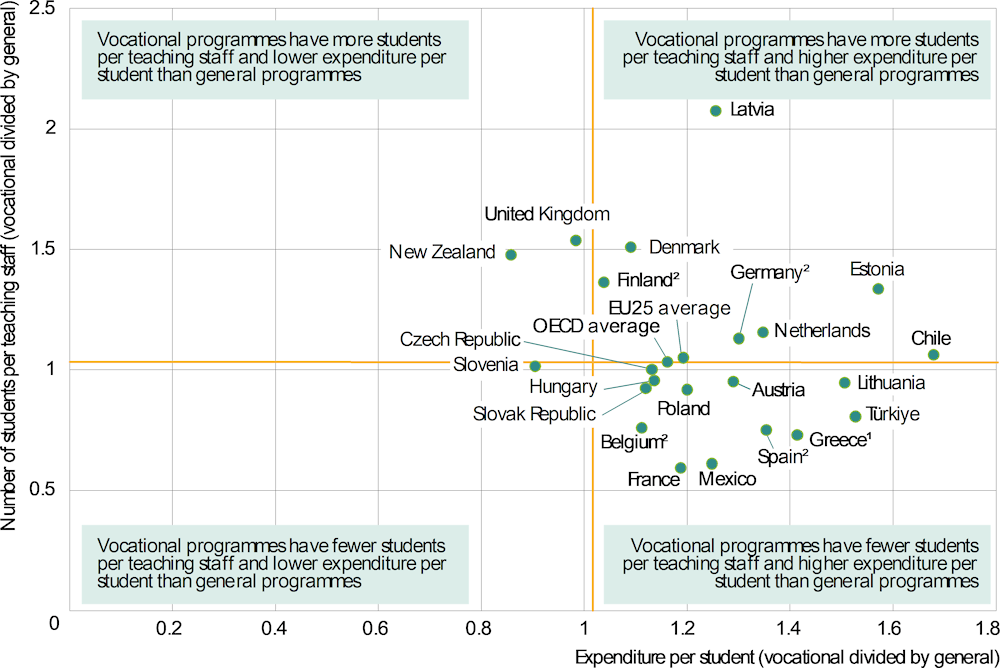

VET programmes typically cost more per student than general programmes. On average across OECD countries, total expenditure on educational institutions per student in 2020 is about USD 11 400 in general upper secondary programmes, compared to about USD 13 200 in vocational programmes. The largest differences are seen in Chile, Estonia, Iceland, Lithuania and Türkiye, where funding for students enrolled in upper secondary vocational education is at least 50% higher than for students enrolled in general programmes (Figure 9).

Higher expenditure per student may stem from vocational education often requiring specific equipment and infrastructure, especially when work-based learning is not extensively used. Vocational programmes may also be expected to have lower student-to-teaching staff ratios (i.e. smaller classes) than general ones because of their practice-oriented nature, driving the expenditure per student upwards. However, this second relationship is not easy to establish as it varies according to the field of study and because of complexities in reporting consistent enrolment and expenditure data for the work-based part of vocational education.

The relationship between expenditure per student and the number of students per teaching staff member in both general and vocational programmes can provide valuable insights into the educational resources allocated per student. Higher expenditure per student coupled with a lower student-to-teaching staff ratio may indicate a greater investment in individualised attention and support for students. This can be particularly important in vocational programmes, which generally emphasise practice-oriented training.

However, no strong correlation is found when plotting differences in the expenditure per student against differences in the number of students per teaching staff. The student-to-teaching-staff ratio in vocational programmes across OECD countries is higher than in general programmes, with 15 students per teacher on average in VET compared to 14 in general programmes. Only 10 out of the 23 countries with available data report that upper secondary vocational programmes have fewer students per teaching staff member than general programmes, and these 10 countries are not necessarily those with the greatest difference in expenditure per student between vocational and general education. In other words, although the student-to-teaching staff ratio is indeed lower in vocational programmes in some instances, it does not consistently correlate with higher expenditure per student (Figure 9). A potential explanation may be that countries putting the emphasis on work-based learning would require fewer VET teachers, and thus have both higher student-to-teaching staff ratios as well as lower levels of expenditure per student, all else being equal.

Figure 9. Differences by programme orientation in expenditure per full-time equivalent student and number of students per teaching staff (2020)

1. Year of reference differs from 2020. Refer to the source table for more details.

2. Data on upper secondary includes another level of education. Refer to the source table for more details.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en, Table C1.1 and Indicator D2.

Latvia is an interesting case: its upper secondary vocational programmes have twice as many students per teacher as its general programmes, the largest difference across countries with data. This may be because vocational programmes are significantly work-based, so vocational students spend a considerable amount of time outside of school while still enrolled. The difference is also influenced by the optimisation of the vocational education school network, which has not been carried out for general education schools yet. Despite this much higher ratio of students per teacher in vocational programmes, Latvia’s expenditure per student in upper secondary vocational programmes is still higher than in general ones, with a ratio comparable to the OECD average. This could be related to the fact that Latvia captures expenditure associated with the work-based component of its programmes, while some other countries may not be able to report this information, but also to the differences in material and technical costs between vocational and general education programmes, which is confirmed by the data for most OECD countries.

In upper secondary education, central governments, rather than regional or local authorities, provide the largest share of government funding in most OECD countries even after transfers between government levels. On average, central governments provide more than 60% of government funding in upper secondary VET, compared with 53% for general programmes. While governments tend to be the main funder of the school-based part of VET, enterprises bear the bulk of the cost of work-based learning (with some government support in many countries). On average across OECD countries, other private entities than households account for 5% of the total funding for upper secondary vocational programmes, but only 2% of the total for general ones. In Norway for example, where almost 3 VET students out of 4 were enrolled in a combined school- and work-based upper secondary programme in 2021, private entities other than households account for 14% of the total funding of upper secondary vocational programmes.

The delivery of VET also often involves transfers, including some that are specific to VET (e.g. subsidies to employers hosting apprentices). Government transfers to the private sector become more relevant for higher education levels: they average 2% for upper secondary vocational education whereas they represented less than 1% of the total funds devoted to primary and lower secondary education in 2020 across OECD countries. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, several countries introduced new financial incentives or scaled up existing ones to support employers providing work-based learning opportunities. In some countries, these new or scaled-up incentives have been specifically targeted at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as, even under normal circumstances, they tend to face more barriers to the provision of work-based learning than larger firms do. During the COVID-19 crisis, many countries also encouraged teachers to develop their skills in remote or hybrid teaching, by providing financial support for training.

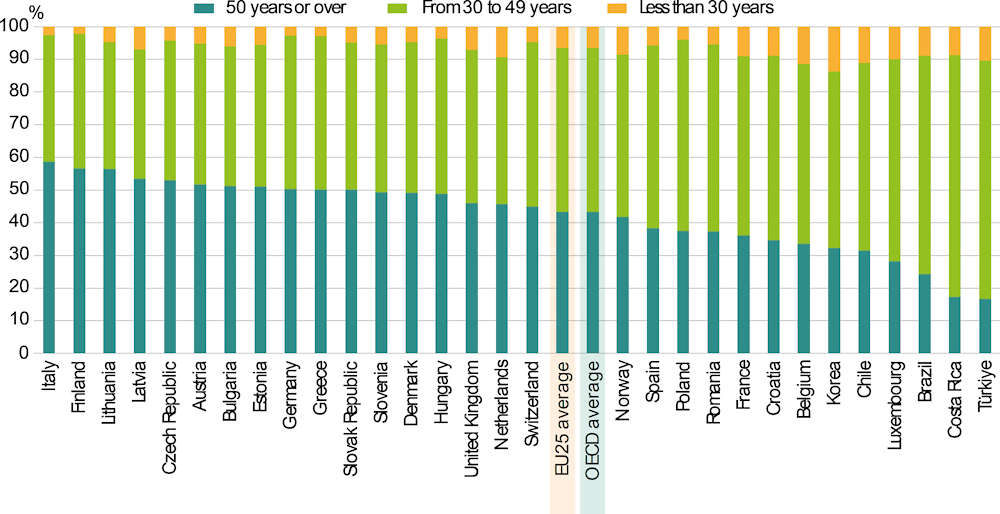

The VET teaching workforce

The VET teaching workforce is ageing: on average across the 25 OECD countries with available data, 43% of teachers in upper secondary VET programmes were 50 years old or older in 2021, compared to 41% in 2013 (Education at a Glance Database and Figure 10. ). This is higher than the share for general education teachers (39% in 2021), where there has been a similar 1 percentage point increase between 2013 and 2021. These large proportions of older teaching staff reflect the wider challenge of an ageing teacher workforce in many countries, but could also be compounded by the usual practice (or sometimes even requirement) of VET teachers gaining industry experience before joining the teaching profession.

Figure 10. Age profile of teachers in upper secondary vocational programmes (2021)

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of teachers aged 50 years or over in upper secondary vocational programmes.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en,, Table D7.2.

Enabling VET teachers to develop and update their skills is an important issue for VET, as technological advances are very rapid in certain parts of the labour market and VET teachers need to stay abreast of these changes. This has led to some countries to introduce reforms in recent years. For example, the Slovak Republic has introduced several measures to facilitate collaboration between schools and companies in VET. Since 2018, teachers working as pedagogical advisors in work-linked training have had dedicated time to collaborate with employers. Brazil has considerably expanded the training on offer for VET teachers and trainers, taking advantage of digital training solutions (OECD, 2021[12]).

The vocational teaching workforce has become more female in many countries. Between 2013 and 2021, the share of male teachers in upper secondary vocational programmes fell by 2 percentage points (from 47% to 45%) on average across OECD countries. However, teachers in upper secondary vocational programmes are more likely to be men than those in general ones. On average across OECD countries, men account for only 39% of teachers in upper secondary general programmes. Despite their substantial representation among the VET teaching staff at upper secondary level, women continue, as for general programmes, to be paid less than men. However, female VET teachers are also more likely to work part-time than their male peers.

Notes

← 1. It should be noted that vocational programmes at lower secondary level also exist in some countries, but account for only a very small proportion of enrolments at this level. VET programmes at this level are often designed for adults and are not part of initial education. These programmes are not included in the Spotlight.

← 2. These programmes in principle have a large work-based learning component, but in the end not all learners will indeed take up work-based learning, sometimes because this is not mandatory, sometimes because it is not available)