The chapter reviews selected implications of trade integration via global value chains (GVC) and identifies gaps in understanding of GVC risks. Despite recent significant progress, many GVC risks remain unknown. The chapter also discusses pros and cons of possible strategies to minimise GVC risks and specific measures that are debated in the literature. None of the proposed strategies is a silver bullet and best measures are likely to vary across products and sectors. Most actions to improve resilience lie with firms rather than governments. There is less controversy about governments taking a more proactive role in co‑ordinating data collection, analysing GVC risks and collaborating with private firms to promote standards of conduct. In contrast, there is less agreement about governments using financial incentives, regulatory requirements and direct government control to reshape GVCs. Government intervention risks creating costly distortions without minimising economic volatility and improving national security, and making international co‑operation.

Economic Policy Reforms 2023

Going for Growth

2. Risks and opportunities of reshaping global value chains

Abstract

Introduction and the main takeaways

Growing trade and capital integration in the 1990s and the 2000s have profoundly affected the performance and structure of the global economy. Globalisation enabled increasing specialisation, concentration of production and trade in intermediate inputs. These brought many benefits in terms of higher productivity, lower prices, greater variety of goods and accelerated income convergence of many emerging-market economies (EMEs). However, some global value chains (GVCs) have become intricate and prone to disruptions that spread across sectors and economies. The COVID-19 crisis and Russia's war against Ukraine have acutely renewed awareness of these risks, even if international trade and GVCs proved to be beneficial in many instances.

Globalisation is facing political headwinds. Factory closures and growing income inequality have contributed to eroding social support for globalisation in advanced economies for more than a decade. National security and strategic autonomy considerations have gained traction, risking a more fragmented economic and political order. In many OECD countries, the supply of some critical goods has become heavily dependent on imports, raising geopolitical risks. All these factors have led to increased calls on governments to wield economic measures (trade, investment and industrial policies) to limit dependency on some foreign economies.

Against this background, this chapter reviews selected characteristics of trade integration via GVCs and their implications and identifies gaps in our understanding of risks related to GVCs, building on extensive OECD analyses and the academic literature. The focus is on foreign dependencies, including the so‑called strategic dependencies, geographical and firm concentration of production, weak points in supply chains and shock propagation. The chapter then outlines possible general strategies to address GVC risks identified in the rapidly emerging literature. Subsequently, the chapter discusses specific measures that private firms and governments could take, stressing their pros and cons. To keep the chapter concise, many other aspects of globalisation, including capital flows, migration, and knowledge spillovers, are not analysed here even if they interact with trade integration and policies aimed at addressing GVC risks. The main takeaways of the chapter are summarised in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1. Main takeaways

Increased trade integration and the emergence of global value chains (GVCs) have contributed to higher productivity, lower prices, greater variety of goods, and accelerated income convergence of many emerging-market economies.

At the same time, dependency on imports, including for pharmaceuticals, products underpinning green and digital transitions and energy, and on exports increased but to a varying degree across OECD countries and sectors. The production of some products has become highly concentrated in specialised firms and countries. GVCs have become longer and more complex.

These features ensure efficiency gains and facilitate diversification of supply and demand. However, they may create potential for single points of failure (choke points) and for propagation and amplification of micro shocks. They may also raise geopolitical risks.

Theoretical links between trade integration and economic volatility are not clear‑cut, and related empirical evidence is mixed. Even if trade were to increase volatility, it is not obvious that such volatility is univocally bad and should be limited. According to some simulations, the quantitative effects of higher volatility are not guaranteed and are small in relation to efficiency gains.

Understanding of GVC risks has improved, but many unknowns remain. Exposures at product and firm levels are less well researched. Many GVC indicators based on input-output data do not account explicitly for substitutability across suppliers, complementarity of inputs to production, international transport, and foreign dependencies of investment and technologies.

The potential for reducing GVC risks without eroding efficiency gains vary across products and sectors. So do possible strategies and specific measures. Diversifying, bringing production home or to closer (friendlier) locations (the so-called re-shoring and near-(friend)-shoring), and optimising stockpiling are the three most frequently discussed strategies.

Diversifying is generally superior to re-shoring in ensuring resilience and robustness of supply chains. Near-shoring can reduce delays of long supply chains and import fees. Friend‑shoring can facilitate greater regulatory alignment, involve smaller risks to intellectual property and help to minimise geopolitical risks. However, defining “friends” based on clear and lasting criteria without adding to business uncertainty is challenging.

Reshaping supply chains can be costly, but diversification could be less expensive than re/near‑shoring. It is generally cheaper and easier to diversify production of goods that require simple technologies, are characterised by small economies of scale and are standardised. Diversifying and re-shoring may be unviable or difficult in sectors with high fixed costs and for many natural resources.

Adjusting inventories could boost GVC robustness for some goods and for some shocks, but it is not a panacea for all GVC risks. It can also be costly. The viability of this solution is going to vary not only across sectors but also across products and firms within a given sector.

Most actions to improve resilience lie with firms rather than governments. Private firms have financial incentives to reduce risks of costly disruptions to production, though they could be muted by costs of adapting supply chains and by the sunk costs of past investment. Private firms seem also to be best placed to choose between minimising exposures to risks (robustness) and improving the ability to resume operations after a negative shock (resilience).

The fundamental questions about the case for and the nature of public involvement in reducing GVC risks remain unsettled. Public intervention can be in principle justified when public and private interests are misaligned, and when private firms underestimate risks due to the lack of information.

Governments could take a more proactive role in co‑ordinating collection of data and analysing GVC risks. They could also collaborate with private firms to promote standards of conduct to increase robustness and resilience. The benefits would be higher if such efforts are co‑ordinated internationally. Governments may also conduct stress tests for essential supply chains, but feasibility and design of such test remain challenging.

Governments can in principle support risk‑reducing strategies with a combination of financial incentives, regulatory requirements and direct government control. These measures vary in effectiveness, side effects. They should be tailored to specific industries and products, given considerable heterogeneity across sectors and firms. The complexity of modern supply chains makes a comprehensive evaluation of government policies aimed at minimising GVC risks and the ensuing distortions difficult.

The main concern about distortions of policies aimed at reducing foreign exposures relates to efficiency effects as they can impose significant welfare losses.

Threats to national security in principle justify insuring against negative geopolitical events or acting to prevent such events. However, geopolitical risks and associated economic costs are difficult to evaluate. Besides, some policy measures may prove ineffective in ensuring security. To minimise risks that such policies will be ineffective and costly for taxpayers and consumers, objective and thorough evaluations are needed.

So far, most of GVC-risk-reducing government policies have focused on re/near/friend-shoring, with fewer measures aimed at diversification and inventory management. Scant empirical evidence on the effectiveness of the government measures to encourage re‑shoring and friend‑shoring is mixed.

Protectionist policies could hinder achievement of global social and environmental objectives. Inward-oriented policies could also reduce knowledge spillovers, with negative consequences for technological progress and productivity growth. Tit-for-tat protectionist policies could magnify welfare losses from the less integrated world economy.

Trade globalisation: Trends and implications

After a rapid expansion, trade globalisation has ceased to advance

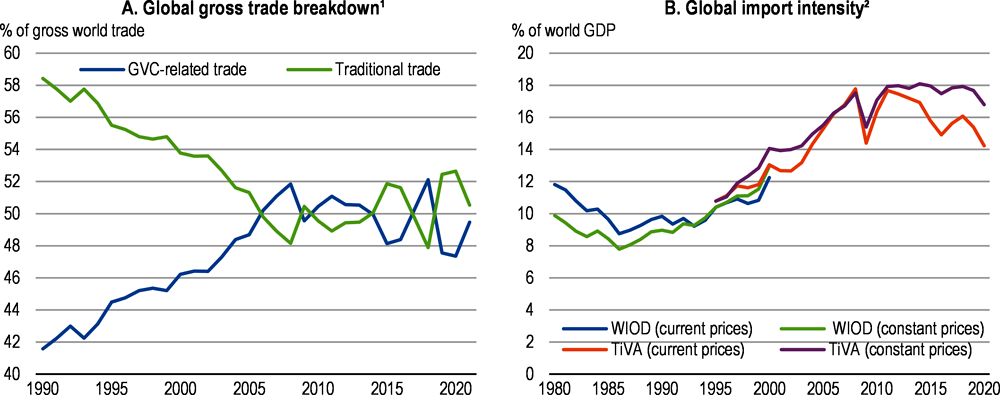

Since the mid-1980s, global trade has increasingly moved from the exchange of finished goods between countries to breaking up of stages of production across borders. This process changed the nature of specialisation from one focussed on discrete products to one focussed on the production of individual components and processes as part of wider global production chains. In this model of global trade, materials and components cross national borders many times as they move through stages of the production chain (Cheng et al., 2015). Consequently, trade in intermediate goods became increasingly important for world trade in the 1990s (Figure 2.1, Panel A).

Since the global financial crisis, there has been some signs of slowing or retreating trade globalisation, at least as far as measured by flows of gross exports and imports. However, trade in goods and services remain an important share of global production (Jaax, Miroudot and van Lieshout, 2023). The fall in the ratio of goods trade to GDP is largely driven (until more recently) by declines in the relative price of heavily traded goods, such as fuel and mining commodities, and by the declining importance of manufacturing as a component of GDP (Baldwin (2022); Figure 2.1, Panel B). Still, an actual decrease in fragmentation has also contributed (Jaax, Miroudot and van Lieshout, 2023). However, world trade flows have remained high, trade in services has continued to grow, and GVC activity is still close to the level of the mid-2000s (Antràs, 2020).

The shift to fragmented global production chains observed from the mid-1980s was driven by three factors (OECD, 2013; Antràs, 2020). First, falls in tariffs and improvements in the cost and reliability of transport across borders meant that multiple production sites imposed less of a burden on manufacturers. Second, new information and communications technologies (ICT) allowed the effective management and co‑ordination of geographically dispersed production sites. Third, the spread of the global market system gave firms access to large and cheap workforces and growing numbers of customers. Off‑shoring not only lowered the marginal cost of production but also encouraged higher output to better amortise the fixed costs associated with moving production overseas.

One of the key trends to emerge from the last three decades has been the increasing importance of China in GVCs. A large supply of low-cost labour and a regulatory environment conducive to trade resulted in significant inflows of FDI to China, which has contributed to the development of China-centric GVCs (Xing, 2022).

Figure 2.1. Global trade integration remains high

1. Traditional trade considers exports of goods and services that are produced in one country and absorbed in the destination country. Therefore, only one frontier is crossed. GVC trade comprises exports of goods and services that are produced in more than one country and have crossed more than one border, at least. The time series are spliced from World Bank Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) Eora and Asian Development Bank Multi-Regional Input-Output data.

2. The Long-run World Input Output Database 1965 – 2000 (WIOD) and OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) are measures of global trade and value chains. Import intensity is a measure of the ratio of imports to total production.

Source: World Bank WITS Eora; ADB MRIO data; OECD Inter-Country Input-Output database; Long Run World Input Output database; OECD calculations.

Trade globalisation has brought many benefits but involved hardships for some

Trade integration and the emergence of GVCs have brought many benefits to consumers and firms. The development of the multilateral trading system has drastically lowered the price of consumer and intermediate goods and increased the range and quantity of available goods. These benefits are felt also among lower‑income households who spend a larger proportion of their income on standardised consumer items (Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal, 2016; Jaravel and Sager, 2019). Trade is also associated with higher productivity through channels such as technology transfer and knowledge diffusion and access to a wider variety of inputs (Égert, 2017). Access to larger markets has helped high‑productivity firms to increase their output and employment. Participation in GVCs has allowed firms and workers, often from EMEs, to specialise in the stages of production at which they are most competitive, without having to master all the technology needed to produce complex modern products and without requiring the domestic development of supply chains which may not be globally competitive (OECD, 2017).

The fragmentation of production has also facilitated the integration of many EMEs into the global economy, helping to achieve a rapid technological catch-up and significant reduction in global poverty. Increases in trade volumes in developing economies have been associated with high economic growth, relative to advanced economies and developing economies that did not benefit from global trade and participation into manufacturing stages of value chains (Dollar and Kraay, 2004). Leveraging the steps of the production chain where EMEs have a comparative advantage has improved the living standards of workers in these countries. Growth in GVC exports of EMEs is associated with increases in key macroeconomic variables such as GDP per capita, investment and productivity (Mitra, 2020). GVCs have had direct positive impacts on jobs and wages in EMEs and, through spillover effects, in the global economy. They have also increased demand for skilled workers in these countries (WTO, 2019).

Trade integration has been disruptive to many industries and local communities in advanced economies, contributing to anti-globalisation sentiment (Rodrik, 1998; Antràs, 2020; Rodrik, 2021). Growing trade and capital mobility in the 1990s and the 2000s enabled substitutability of labour provided by large segments of advanced economies’ population with labour of people in EMEs. This has contributed to a reduction in labour bargaining power, partly due to the segmentation of the workforce, and in manufacturing employment (Durand and Milberg, 2019).1 Consequently, many workers have experienced instability in earnings and precarity, and real growth in median earnings has been sluggish (Acemoglu and Autor, 2011). These effects have been stronger in the United States than in Europe. This is partly explained by less generous social protection in the United States than in Europe. On the other hand, large income gains have been realised by shareholders of companies that benefited from globalisation.

The exact contribution of international trade and off-shoring to rising income inequality is still being debated. Some researchers find that trade played only a small role in rising wage inequality within countries, with technological progress favouring highly-skilled workers and changes in corporate and public policies being more important causes (Helpman, 2018; Heimberger, 2020).

Generally lower labour and environmental standards in EMEs than in advanced economies have led to perceptions of unfair competition and to underestimation of the total social costs of off‑shoring. According to some estimates, environmental externalities of production in off‑shore locations are considerable, particularly in heavy industries (Wiedmann and Lenzen, 2018; Felbermayr and Peterson, 2020). Independent from domestic standards, long‑distance international transport increases the cost of environmental externalities. Moreover, some cases of breaches of basic labour rights add to social externalities of globalisation (European Union, 2021).

Selected characteristics of global value chains and their implications

Increased trade integration and specialisation have boosted productivity and lowered prices. The flip side of these processes is that: dependency on imports, including for products underpinning green and digital transitions, and dependency on foreign demand increased; the production of some products has become highly concentrated in specialised firms and countries; and GVCs have become longer and more complex. These features have given rise to potential single points of failure (choke points) but also improved resilience in some cases. A low diversity of suppliers or buyers can increase the risk of disruption and can magnify the propagation of shocks given few alternatives to buying from or selling to other firms or countries (Arriola et al., 2020; Schwellnus et al., 2023).

Import and export dependencies

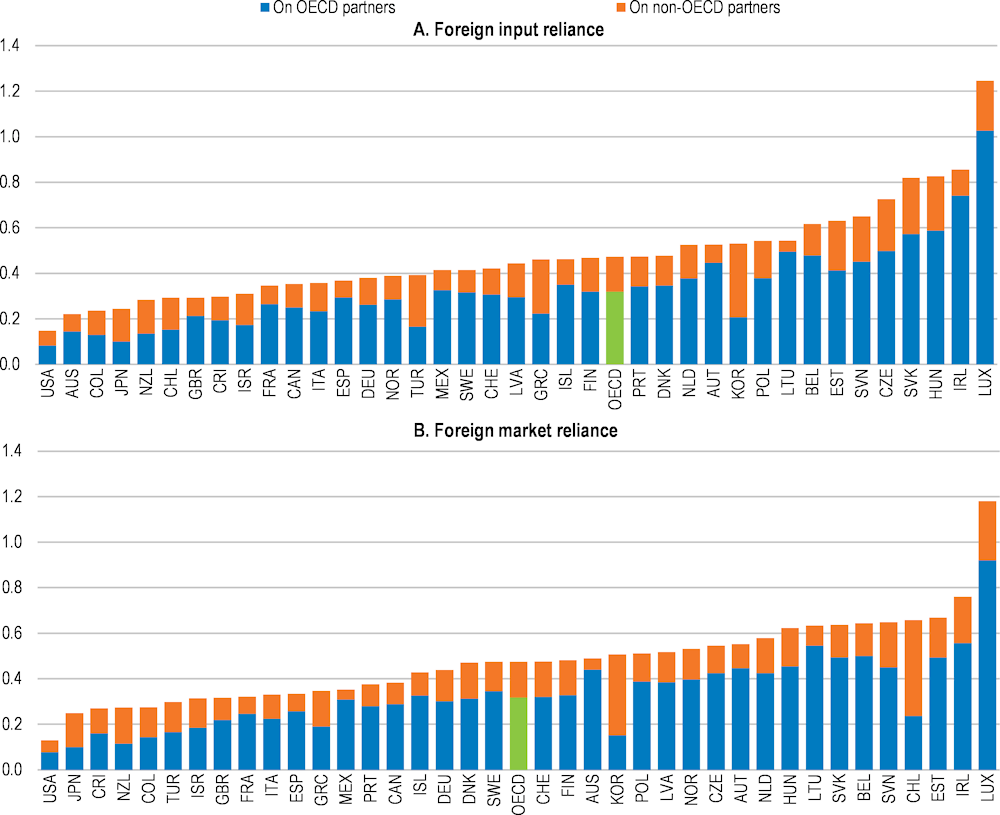

Various measures of foreign exposures exist. Each has advantages and disadvantages (Borin, Mancini and Taglioni, 2021; Baldwin, Freeman and Theodorakopoulos, 2022). Measures based on gross trade, in contrast to trade in value added, that account for both direct and roundabout trade via third countries are preferred for assessing exposures to supply shocks. For instance, foreign input reliance (FIR), measuring dependencies on suppliers (upstream), and foreign market reliance (FMR), measuring dependencies on buyers (downstream), capture risks to GVCs stemming both from the size of exposures and the complexity of the value chain (Schwellnus et al., 2023).

Figure 2.2. Foreign dependencies vary across OECD countries

Note: Foreign import reliance (FIR) can be understood as the share of a country’s output that is exposed to disruptions to overseas supply chains. It is computed as the ratio of foreign inputs used in domestic industry to domestic gross output. Foreign market reliance (FMR) measures the share of a country’s output that is used overseas, and it is computed as the ratio of domestic output used in foreign production to domestic gross output.

Source: Schwellnus et al. (2023), “Global Value Chain Dependencies under the Magnifying Glass”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 142, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The analysis of the FMR and FIR indicators highlights key features of foreign dependencies (Figure 2.2, Schwellnus et al. (2023)). Not surprisingly, small open economies tend to be more exposed to foreign suppliers and buyers. Downstream dependencies in several cases arise from specialisation in mining of natural resources (Norway, Chile and Australia). For most OECD countries, exposures are largely within the OECD block, especially within regional hubs: the Americas, Europe and Asia. However, some Asian and South American countries depend crucially on China. Moreover, dependencies vary significantly across sectors. Motor vehicles, other transport, textile and apparel, ICT and electronics and machinery are particularly dependent on foreign inputs, and mining, warehousing and chemicals being particularly exposed to foreign demand.

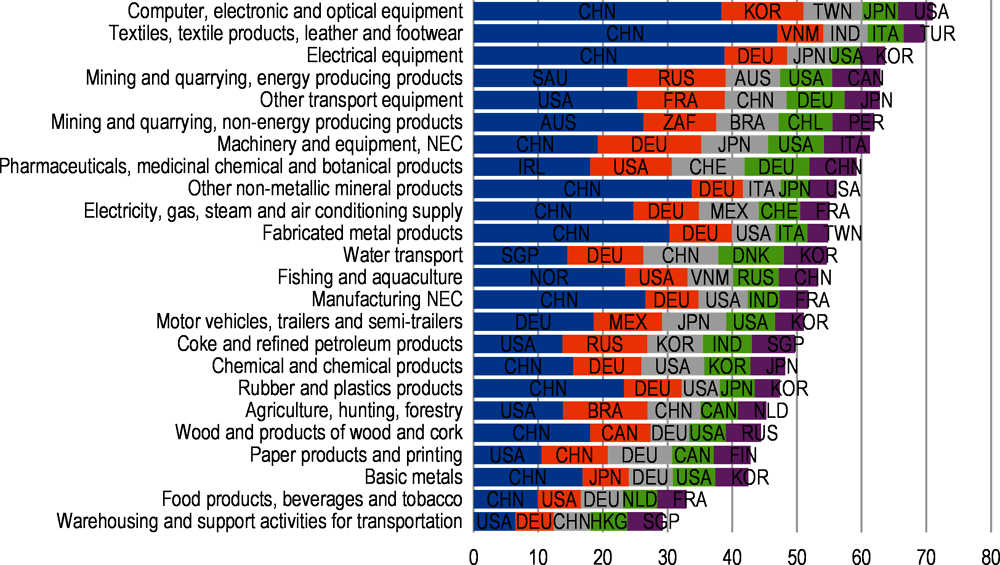

Country concentration of production and exports

Production of several sectors and products is highly concentrated in very few countries. The share of the top five countries in global gross output is the highest in mining, machinery, textile and apparel, electrical equipment, ICT and electronics, basic metals and fishing industries (Schwellnus et al., 2023). These concentrations are positively correlated with the size of economies, with China and the United States dominating the ranking. The country concentration of intermediate goods exports in mostly manufacturing sectors is smaller than for gross output but still high in some sectors (Figure 2.3). The ranking of countries is more diversified geographically, even if China and the United States still top the ranking in most of the analysed sectors.

Figure 2.3. The geographic concentration of intermediate goods exports is high in some sectors

Note: Excluding exports of the rest of the world in the Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) database. NEC stands for not elsewhere classified.

Source: Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) database; and OECD calculations.

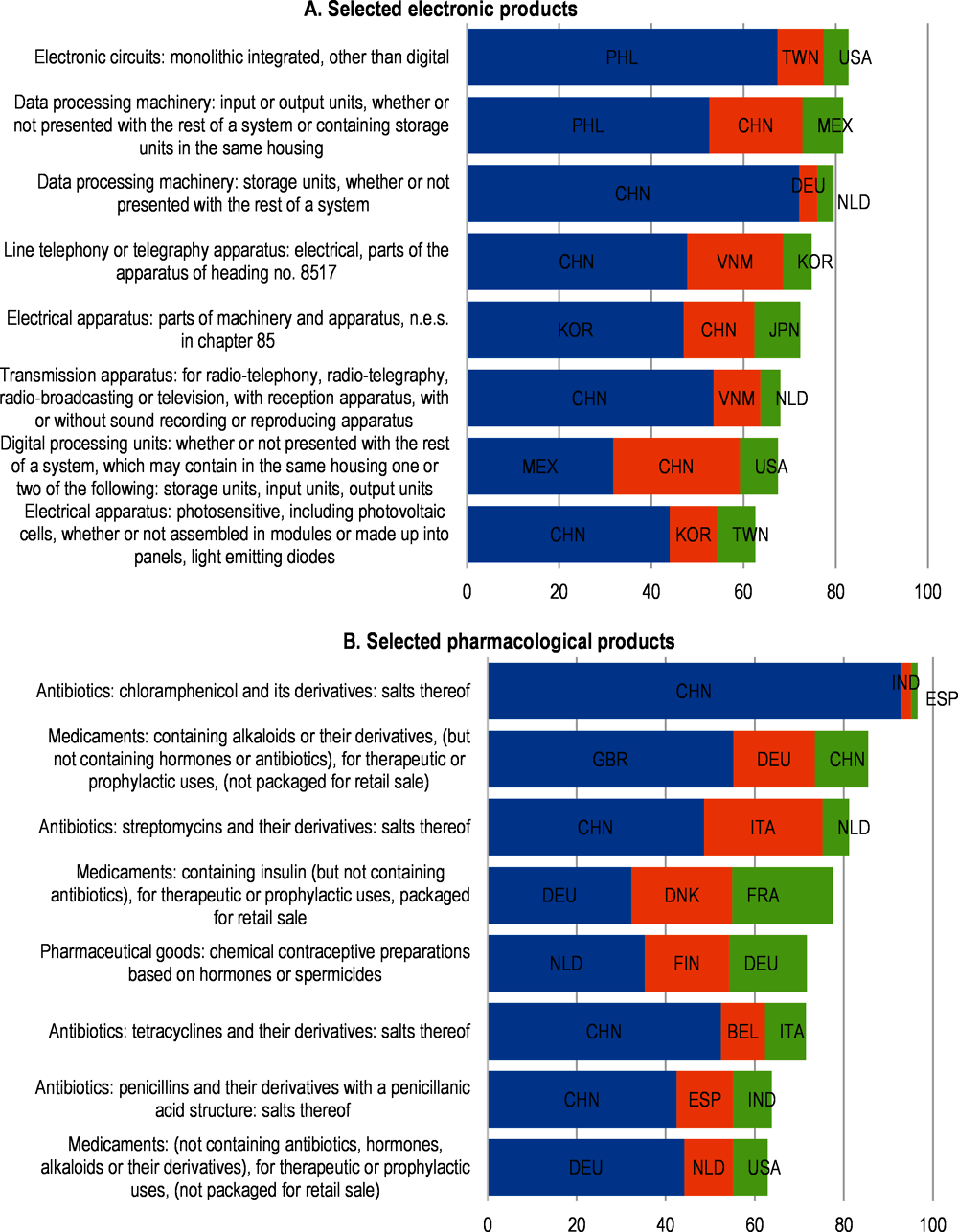

The geographic concentration can be even higher at a product level. For example, for many electronic products (including electronic circuits, data processing machinery and parts of telephone equipment) three‑quarters of world inputs is provided by two countries, with China, Korea, the Philippines and Vietnam leading the ranking (Figure 2.4, Panel A; Arriola et al. (2020)). Production is also highly concentrated for many pharmaceuticals, especially for components of antibiotics, with China and several European countries being the main producers (Figure 2.4, Panel B).

Figure 2.4. The geographic concentration of production is also very high for individual products

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2020 BACI (Base pour l’analyse du Commerce International) database; and and Arriola et al. (2020), “Efficiency and risks in global value chains in the context of COVID-19”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1637, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Strategic dependencies

One aspect of dependencies relates to imported products that are of strategic importance to a nation (Bonneau and Nakaa, 2020; European Commission, 2021; The White House, 2022). There is significant ambiguity in the definition of strategic dependencies in international law. In practice, various reports usually identify strategic sectors as related to security and safety, healthcare, energy, and goods, services and technologies that are key for digital and green transitions.2

The European Commission (2021) has identified 137 strategic products for which the European Union depends significantly on imports from third countries, mainly from China but also from Vietnam and Brazil.3 These products relate to raw/processed materials and chemicals that are energy‑intensive; active pharmaceutical ingredients and other health-related products; and several essential products for digital and green transitions. Imports of around one‑quarter of these products are particularly vulnerable given low potential for further diversification and substitution with domestic production (the latter due to large price differences). In the United States, strategic dependencies on China are similar to the ones in the European Union. They mainly relate to several products in healthcare, selected raw materials, and key products for green and digital transitions (European Commission, 2021; The White House, 2022).

The semiconductor industry has gained strategic importance given its vulnerability due to high geographical concentration (Haramboure, Lalanne and Schwellnus, 2023). Semiconductors are critical inputs into a range of industries, including ICT goods, electronics and motor vehicles (with their value added accounting for up to 8% of final demand) and military equipment. Their shortages during the COVID‑19 crisis have demonstrated the potential to disrupt production in other sectors. The top‑five semiconductor‑producing economies account for around three‑quarters of global value added. Currently, their production is dominated by China, Korea and Chinese Taipei; they account for around 60% of global semiconductor value added.

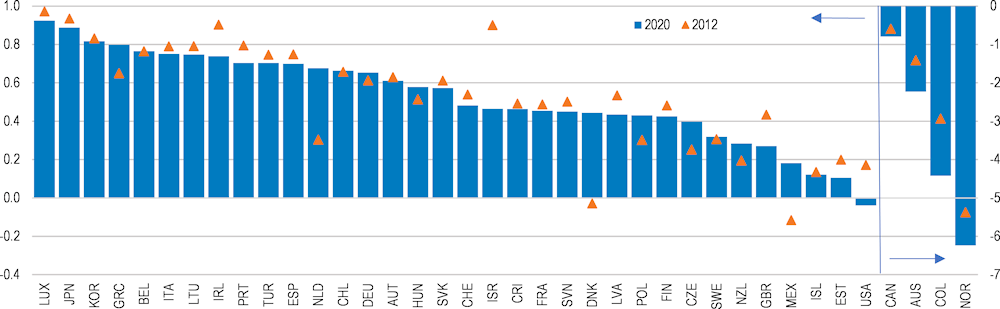

Energy is a critical sector, and the volatility of supply can affect its costs severely, with important implications for household life quality and firm competitiveness. Many OECD countries are highly dependent on foreign energy sources, especially in Europe and East Asia (Figure 2.5). Furthermore, energy sources are relatively unfungible in the short term, such as powerplants and vehicle fleets, use specific fuels. This can exacerbate the dependency of national energy systems. Import dependencies are particularly high for crude oil and natural gas. For instance, while the overall energy import dependence rate of the European Union was 58% in 2020, its import dependency rate for natural gas was 88%.

Figure 2.5. Energy import dependence is high in many OECD countries

Note: The figure shows the energy import dependency rate which is calculated as the ratio of net imports (imports minus exports) to gross inland energy consumption (production plus net imports). Energy includes coal, oil, natural gas and electricity.

Source: IEA Extended World Energy Balances Database and OECD calculations.

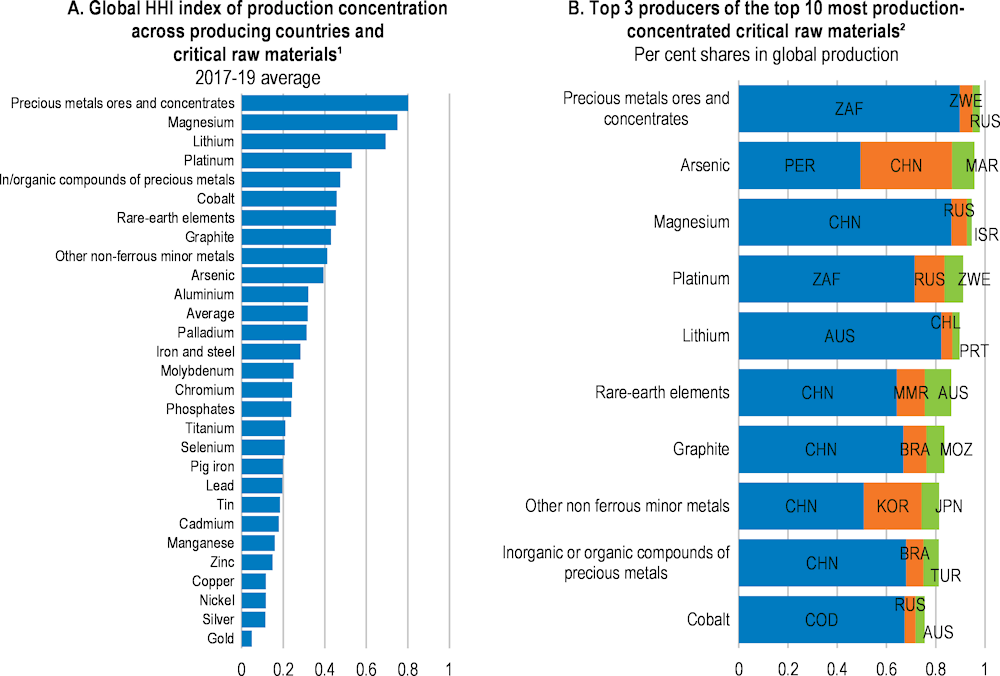

In the last decade, production of critical raw materials has become increasingly concentrated amongst few countries (Kowalski and Legendre, 2023), frequently categorised as politically unstable or extremely unstable (Federal Ministry of Agriculture Regions and Tourism, 2022).4 Moreover, some of leading countries account for large shares of production of more than one critical raw material (Figure 2.6). China is among top three producers of six out of ten most production‑concentrated critical raw materials. The processing of critical minerals is high and typically more concentrated than extraction (IEA, 2022). However, for some minerals, the current concentration of extraction is higher than the concentration of natural reserves, implying that extraction may become less concentrated in the future.5

The high concentration of production is partly explained by geological conditions and high fixed capital costs in mining and quarrying, but industrial policies have played a role too. China’s leading position in owning foreign mineral assets and refining capacities are behind its dominance.

Figure 2.6. Concentration of production of critical raw materials is high

1. Concentration of production is measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI).

2. 3-letter country ISO codes for countries that are not in the OECD and are not among the key partners and the accession countries refer to: Democratic Republic of the Congo (COD), Morocco (MAR), Mozambique (MOZ), Myanmar (MMR), Russia (RUS) and Zimbabwe (ZWE).

Source: Kowalski and Legendre (2023), “Raw materials critical for the green transition: Production, international trade and export restrictions”, TAD/TC/WP(2022)12/REV1; and OECD calculations based on the United States Geological Survey data.

Concentration is also high for several products that are central for the green transition. For example, China dominates global production of solar photovoltaic (PV) products and batteries, which are central for achieving the next zero emissions targets (IEA, 2022; IEA, 2022). China’s share of global polysilicon, ingot and wafer production (the key stages in the manufacturing process of solar PV) is soon expected to reach 95%. This production is concentrated in a single region and in a few factories, leading to important supply vulnerabilities. China produces three quarters of all lithium-ion batteries and is home to 70% of production capacity for cathodes and 85% for anodes – the two key components of batteries. China’s dominance in these products owes to government industrial policies that enabled huge economies of scale and continued innovation in the supply chain.

Centrality and choke points

The structure of networks determines potential GVC vulnerabilities and propensity to amplify shocks. Network analysis helps identify the importance of a country or sector in the GVC network – the so‑called centrality – by accounting for the direct participation of countries in GVCs and also for the participation of their value-chain partners (Criscuolo and Timmis, 2018; Cingolani, Iapadre and Tajoli, 2018; Altomonte, Colantone and Bonacorsi, 2018; Arriola et al., 2020). The higher the centrality indicator, the greater the importance of a country/industry as a supplier or customer in the network and the larger potential to propagate shocks.

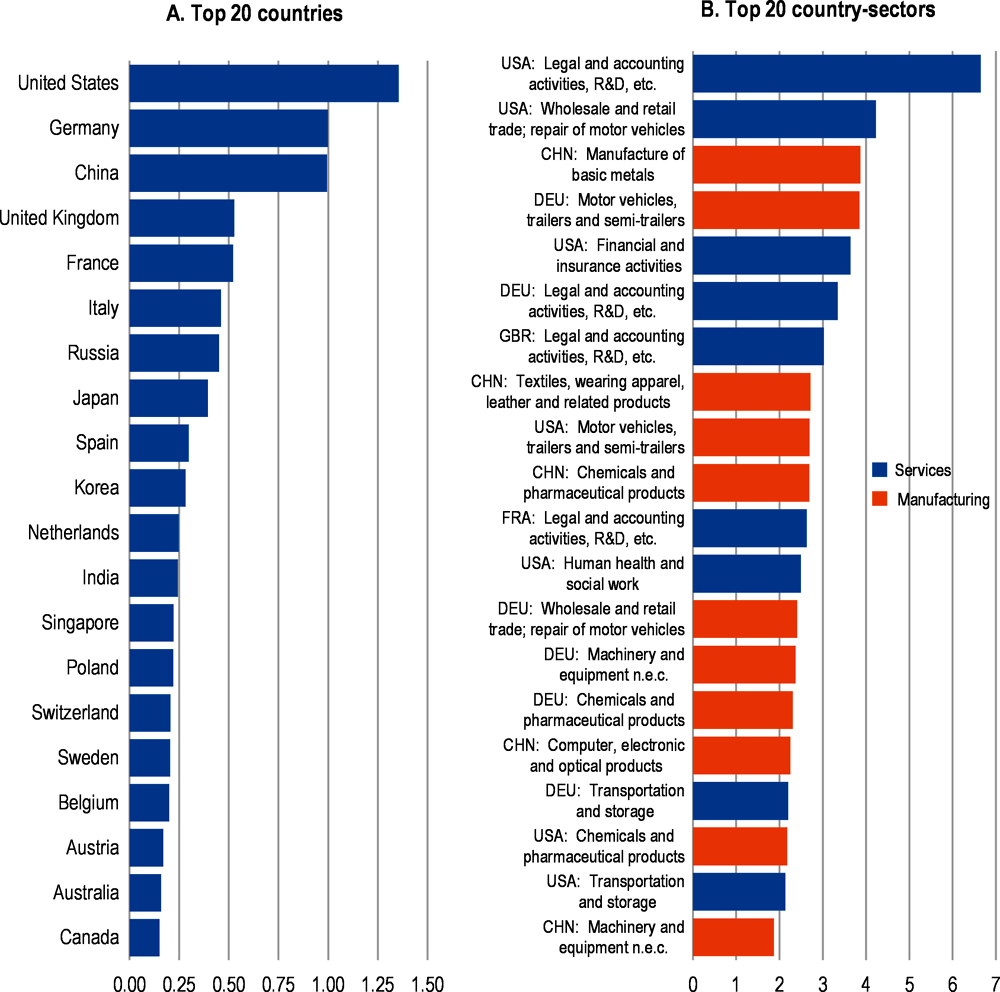

According to some measures, China and G7 countries are the most central countries in GVCs, with China having significantly advanced the ranking since 2005 (Figure 2.7, Panel A).6 Looking at the sectoral ranking, legal and accounting activities and wholesale and retail trade sectors in the United States are the most central among service sectors, while manufacture of basic metals in China and motor vehicles production in German are the most central among the manufacturing sectors (Figure 2.7, Panel B).

A similar picture is given by measures of upstream choke points (defined as the most important suppliers of intermediate inputs) and downstream choke points (the most important buyers of intermediate inputs) (Schwellnus et al., 2023).7 Within the manufacturing industries, China scores the highest in several industries both as the key supplier and as the key buyer (ICT and electronics, basic metals, chemicals, machinery, electoral equipment and construction). China is also an important choke point on the buying side for mining of energy products, while Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States are key on the supplying side. Among the OECD countries, only few manufacturing industries in Germany and the United States are identified as choke points.

Figure 2.7. Centrality differs across countries and sectors

Note: The country centrality measure in Panel A is computed as the average across all sectors’ total foreign centrality for each country. Total foreign centrality in Panel B is computed as the average of forward and backward centrality in a given country-sector. Foreign forward centrality captures the importance of a country or a sector as a supplier of value added embedded in foreign countries’ exports, while foreign backward centrality measures the importance of a country as a buyer of foreign value added used in its own exports. The manufacturing sector excludes construction while the service sector excludes electricity, gas, water supply services. The “rest of the world” has been excluded from the chart. The centrality measure is a relative measure of Bonacich-Katz eigenvector centrality of countries and country-sectors developed in Criscuolo and Timmis (2018). The larger the measure, the more central is a sector/country.

Source: OECD (2018) Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) database; and Arriola et al. (2020), “Efficiency and risks in global value chains in the context of COVID-19”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1637, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Not all vulnerabilities are known

Despite the wealth of data and analyses on country and sector dependencies and centrality, understanding of vulnerabilities is not complete. Exposures on a product level and complexities of networks at the firm level, and their macroeconomic, systemic and security implications, are less well researched. Such micro analyses could help better understand implications for macro risks and design targeted policy measures.

Identification of weak points by researchers and governments is difficult because data on supply chains are proprietary to specific businesses (Farrell and Newman, 2022). Even large firms can have challenges with understanding their own complex networks (Baldwin and Freeman, 2022). Their first‑tier suppliers make up only a small fraction of the full value chain (Lund, 2020).8 Smaller companies could have less complex supply chains but they are more likely than large companies to face resource constraints on effectively monitoring and analysing supply chains and to be reliant on the supply chains of other firms where they do not have access to information.

Comparable trade statistics on specific or specialised products across a large number of countries are not available, preventing more refined analysis of dependencies (European Commission, 2021). The lack of details is particularly acute for services and complex technologies.

Many evaluations of GVCs exposures and risks based on input‑output data (choke points or centrality) usually do not account for important aspects of exposures:

Substitutability. The ease of substituting across suppliers of a given input can affect resilience. For any given exposure to foreign supply of inputs, economic risks are lower (resilience is higher), if foreign products can be easily substituted by alternative suppliers (either from a different country or domestically). As assessment of substitution is challenging, these considerations are usually not part of GVC vulnerability evaluation.

Complementarity. Complementarity of a given input to production also affects resilience. Analyses of shock propagation via GVCs usually assume that a given sector’s output is affected by declines in output of intermediate inputs in proportion to this input’s share in gross output. However, some inputs can be highly complementary, and no output can be produced without them (OECD, 2022). For instance, the share of energy input in gross output is generally small, but most of the sectors would not be able to deliver any output without electricity or gas. Similarly, a lack of semiconductors would prevent the manufacture of many products.

International transport. Shocks to transportation are separate from the standard analysis of shocks to supply and demand. 80% of trade is carried by sea. Shipping networks are characterised by concentration on a small set of routes; most shipping connections involve a stop in at least one other country; and a few central ports, acting as hubs in the sparse network, handle huge chunks of global seaborne (Heiland et al., 2019). Several recent events demonstrate that transportation shocks can significantly disrupt international trade, though such disruptions are usually short‑lived.9 They are more likely for transport between continents, where cheap alternatives for bulk products are not available. However, also the road transport links can be negatively affected.10

Investment: Most analyses of exposures focus on trade in intermediate inputs in relation to gross output or value added. Thus, they fail to account for trade in final investment goods in relation to total investment. Import dependence of investment can be another source of exposures to foreign shocks or policies. For instance, in the semiconductor sector, machines to produce chips are manufactured by few companies.11 Thus, any disruption in deliveries of such machines could make the expansion of production in the future difficult.

Shock propagation and economic volatility

Theoretical links between trade integration and economic volatility are not clear‑cut, and related empirical evidence is mixed. The relationship depends on underlying model assumptions, the nature of a shock, and characteristics of economies and networks. Consequently, it is difficult to draw universal policy implications and to formulate policy solutions.

Increased specialisation can raise volatility by reducing the scope for shock absorption by suppliers (Newbery and Stiglitz, 1984). In addition, complex and long value chains in intermediate inputs can propagate firm or regional-specific disruptions to flow of goods and services across numerous firms and industries in various countries (Levine, 2012). Longer value chains imply also that products cross borders multiple times and consequently there are higher chances of transport disruption.

Microeconomic shocks can be amplified to have macroeconomic consequences (Carvalho and Tahbaz‑Salehi, 2019).12 In principle, the nature of such amplification depends on the distribution of firms’ size and the structure of the input‑output networks; with shocks to large firms that supply many sectors being more likely to affect macroeconomic volatility (Acemoglu et al., 2012). While such effects can arise in a domestic context only, integration in GVCs may have increased specialisation and the heterogeneity across firms in terms of their importance as input suppliers, which is one of the key factors giving a rise in macro volatility from micro shocks.

However, international trade can also facilitate diversification of supply and demand, reducing exposures to domestic shocks. Indeed, a higher diversification of suppliers in production networks minimises the impact of micro shocks on macroeconomy (Carvalho and Tahbaz-Salehi, 2019). In addition, with a global pool of suppliers and fragmented supply chains it may be easier to manage inventories, adapt just a segment of a supply chain, and change a supplier in the presence of a negative shock than with domestic and less specialised production.

Empirical evidence on the role of trade on macroeconomic volatility is mixed (D’Aguanno et al., 2021). Looking at the general link between trade openness and volatility, some studies find that higher trade integration can lead to more volatility (Rodrik, 1998; Easterly, Islam and Stiglitz, 2001; Giovanni and Levchenko, 2009), but others show the opposite (Bejan, 2011; Buch, Döpke and Strotmann, 2021; Cavallo, 2009; Haddad et al., 2013). Papers that explicitly investigate input‑output linkages show consistently that diversification of suppliers reduces economic volatility (Caselli et al., 2020; Ardelean, Leon-Ledesma and Puzzello, 2022; Todo, Nakajima and Matous, 2015). In contrast, the role of specialisation is ambiguous; higher specialisation is found to increase volatility in some studies (Caselli et al., 2020; D’Aguanno et al., 2021), but to lower volatility in others (Ardelean, Leon-Ledesma and Puzzello, 2022). Empirical ambiguity about the link between trade integration and volatility can also reflect inherent differences in volatilities among countries and sectors (Caselli et al., 2020).

Even if trade integration were to increase volatility, it is not obvious that such volatility is univocally bad and should be limited (Levine, 2012). The full assessment should also take into account implications for productivity and welfare (see above). The increasing reliance on intermediate inputs facilitated by GVC integration spurs economic growth, leads to denser production networks and reduces all prices (Acemoglu and Azar, 2020). According to some simulations, the quantitative effects of higher volatility are not guaranteed and are small in relation to efficiency gains (Arriola et al., 2020; D’Aguanno et al., 2021).

A related and important issue in assessing the trade-volatility nexus is the distinction between the resilience (i.e. the ability to recover after a negative shock) and robustness of GVCs (i.e. the ability to maintain operations through the duration of the shock and to minimise the likelihood of the shock) (Miroudot, 2020). Shocks to output in specific sectors, even if frequent, could be short‑lived and have negligible macroeconomic implications in the longer term.13 In other words, even if some value chains are not robust (are affected by shocks), they could be resilient, implying that their production can be quickly restored after a negative shock. For instance, after the Great East Japan earthquake, firms with extensive networks of suppliers had a quicker recovery, partly thanks to support from trading partners, an easier search for new partners, and agglomeration benefits (Todo, Nakajima and Matous, 2015). Resilience of the GVCs could result from the ability of negatively affected companies to resolve problems themselves or from the relative ease to switch to alternative suppliers.

In contrast, foreign exposures maybe consequential when trade is used as a coercive tool (for instance during a prolonged periods of serious geopolitical conflicts or wars), and when it is difficult and costly to substitute affected imports. The abrupt and large reduction of gas and oil imports from Russia following the Russia’s war against Ukraine, and the resulting spillovers to the European economy, illustrate such challenges well (OECD, 2022).

What can be done to reduce GVC risks?

The literature and discussions above demonstrate that despite some risks stemming from GVCs, trade integration has brought many benefits. The need and urgency to reduce these risks without eroding the economic and risk management benefits of GVCs vary across products and sectors. So do strategies and specific measures. In addition, there is no consensus about the extent of public intervention and specific policies. This section discusses possible solutions to reduce GVC risks, specific measures to achieve such goals and the respective roles of the private sector and governments.

Possible general strategies

Global supply disruptions and increasing geopolitical tensions over the past decade have increased calls for reducing vulnerabilities of GVCs and for strengthening strategic autonomy. Three strategies have been most frequently discussed in the literature: diversifying sources of inputs; relocating production closer to home (near‑shoring), especially to friendly countries (friend‑shoring), or home (re‑shoring); and improving stockpiling. Each of these strategies has advantages and disadvantages and the ultimate policy mix should be chosen based on the balance of costs and benefits of the options and how they interact.

Diversifying suppliers is generally preferred over re/near-shoring

Economic arguments mostly support diversification over re-shoring.14 Re-shoring is sometimes portrayed as a strategy to reduce GDP volatility. However, in most cases, self-sufficiency or domestic production does not imply robustness of value chains (Miroudot, 2020). Moreover, several model simulations considering different re-shoring scenarios show that re-shoring does not guarantee to achieve this goal, in contrast to diversification and can imply significant welfare FRe-shoring is just likely to shift the relative importance of domestic versus foreign shocks. Even in the most GVC integrated economies, domestic links are already more prominent than foreign links, raising the possibility of further concentration risks. Similarly, the management literature suggests that re‑shoring and shortening of the supply chains do not necessarily reduce risks (Miroudot, 2020).

Welfare losses and failure to achieve lower output volatility seem to be less of a concern for near‑shoring than re-shoring, given smaller exposures to domestic shocks and, possibly, less marked price differences. Near-shoring can be effectively part of the diversification strategy. Moreover, near-shoring can offer several other benefits. Sourcing from neighbouring economies can reduce delays of long supply chains and import fees. Friend-shoring, which could effectively imply near-shoring and which recently gained political appeal,15 can facilitate greater regulatory alignment, involve smaller risks to intellectual property and help to minimise geopolitical risks (see below).

Nonetheless, friend-shoring may be difficult to operationalise in practice. Firms could face uncertainty which countries will be identified as “friends” in a manner that will be robust over time. The ambiguity about “safe” locations can add to business uncertainty, with negative implications for investment.16

Reshaping supply chains can be costly, but diversification could be less expensive than re/near‑shoring. Finding alternative suppliers of specific products could imply sourcing from more expensive producers. If diversification implies shifting one’s own factories across countries, it will also entail sunk costs of past investment. This will be especially the case for highly capital and knowledge-intensive industries. The exact impact on costs and profits is likely to be firm‑specific and is difficult to assess. In principle, total costs would depend on the size of diversification or re-shoring, price differences between suppliers and any associated changes in transport costs.17 More studies on the price effects of diversification and re/near‑shoring, even at an aggregated level, are needed. The sunk cost argument makes a reshaping of supply chains unlikely in the medium to long term without substantial government support (Antràs, 2020; Baldwin and Freeman, 2022; McIvor and Bals, 2021; European Union, 2021).

Friend-shoring can involve additional costs. The impact of world trade dividing between two blocs could be significant, lowering global GDP by between 0.6% to 4.6% in the medium term (Javorcik et al., 2022). Moreover, homogeneity between friendly countries could eliminate many of the gains from comparative advantage and result in welfare loss.

The possibility to diversify and re/near-shore production is likely to differ significantly across products. Diversifying among products that require simple technologies, are characterised by small scale economies and are standardised is likely to be cheaper and easier than among products that are technology-intensive, require large economies of scale and are highly customised (Baldwin and Freeman, 2022). Economies of scale and resource constraints (labour, capital and technologies) could be also more of an obstacle for re/near-shoring rather than diversification, especially for mid-sized and small economies. Domestic economies and “friendly” countries could face limits to their ability to absorb investment imposed by infrastructural and institutional capacities, available labour force with appropriate skills and the technological base of the economy (Every and van Harn, 2022). Still, diversification may not be viable in sectors with high fixed costs because there would not be sufficient scale of production (Antràs, Fort and Tintelnot, 2017). Similarly, diversification can be difficult to achieve, and re/near‑shoring be virtually impossible, for many natural resources that are characterised by high geographical concentration, stemming from natural monopolies (see above).

The feasibility of diversification and near-shoring will also depend on transport infrastructure. For instance, many Southeast Asian economies do not have ports as large and as efficient as ports in China, which could hinder shifting production from China to other Asia countries (Shih, 2020). Thus, without investment in transport infrastructure, considerable diversification and near‑shoring would imply high transport costs (longer transport time) (Iakovou and White III, 2020).

Optimising inventories can help reduce some supply chain risks

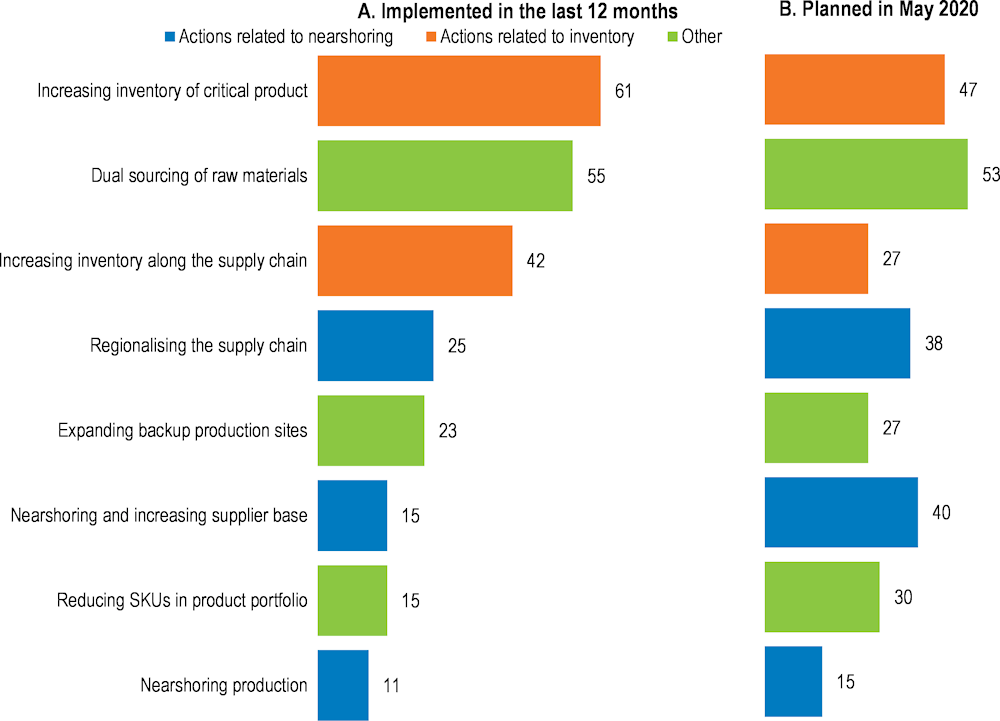

Building redundancy by increasing inventories, especially of critical intermediate inputs and critical final products, has been long recognised as one of the ways to boost robustness of supply chains in some situations (Shih, 2020). Indeed, during the COVID-19 crisis, commentators noted a shift from “just‑in‑time” inventory management to the so-called “just-in-case” approach, driving warehouse take‑up (Salomon, 2022). In mid‑2021, a McKinsey survey of global supply-chain leaders showed that most manufacturers implemented actions to improve inventories rather than near-shore in response to the COVID-19 crisis (Alicke (2021); Figure 2.8). For most products, the cost of storage can be low compared with options to near or re-shore. However, for bulk commodities (including oil and gas), building storage capacity can be expensive and can take time.

Still, the viability of such solution is going to vary not only across sectors but also across products and firms within a given sector. For instance, within pharmaceuticals, stockpiling buffer reserves of perennial drugs with stable demand is indeed a viable option. However, this is not an option for drugs that expire quickly or for which future demand is difficult to predict (for instance due to uncertainties about future health crises and thus required drugs and equipment). Furthermore, while stockpiles can mitigate the impact of volatility in specific supply chains, they will be exhausted by severe or prolonged shocks and rely on stakeholders correctly identifying critical materials and components which could disrupt production and the probability and severity of shocks. The experience of countries during the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the benefits and risks of seeking to manage supply chain disruption through stockpiling. While some countries had significant stocks of personal protective equipment for treating COVID-19 patients, other countries had significant medical stocks that were ill-suited to the needs of staff on COVID-19 wards (Feinmann, 2021). In addition, maintaining sizeable inventories can lead to waste and inefficiencies that may also discourage firms from investing in resilience.

What should be the role for governments?

The fundamental question about the case for and the nature of public involvement in reducing GVC risks remains unsettled. The literature mainly discusses measures at a firm level and not at a country or global level (Baldwin and Freeman, 2022). In principle, private firms have financial incentives to reduce risks of costly disruptions to production. Prolonged delays in delivery of intermediate inputs make production and sales of products difficult which can lead to financial and reputational losses.18 Moreover, a company’s resilience at the time when competitors struggle with resuming production after a negative shock helps it to gain market share and extra profits. However, financial incentives to reduce risks of disruptions are muted by investment needs to adapt supply chains and by the sunk costs of past investment. Private firms are also best placed to decide whether to focus on improving robustness (i.e. minimising exposures to risks) or on improving resilience (i.e. the ability to resume operations after a negative shock). The ideal strategy is likely to differ across sectors and firms (Miroudot, 2020).

Government intervention could be in principle justified on two grounds.

First, when there is a misalignment of public and private interests. For instance, if firms do not account appropriately for social costs of disruptions to production, and ensuing unavailability of specific products, they may underinvest in resilience from the social point of view. In this case, public intervention to align private and societal incentives is justified. A special case of this problem is national security, when the unavailability of certain components or finished products may threaten the economic, health or military security of a country (see below). Thus, leaving the decisions on how best to secure the provision of such goods entirely to private companies could be undesirable. In these cases, the challenge for policymakers is to identify exposures and risks, and to come up with proportional measures to mitigate them. However, this can be difficult in practice.

Second, public intervention could be motivated by a lack of appropriate information that results in underestimation of risks by private firms. This could reflect complexities of supply networks, costs in gathering and analysing data, and co-ordination failures that prevent firms from obtaining a global perspective for a specific product or a market. Government’s help could involve measures to tackle externalities from information asymmetry but also initiatives to improve the understanding of risks (see below).

Thus, direct policy interventions in the global trading system may be justified if they are co-ordinated and targeted to address well‑identified market failures. However, evidence on the presence of such market failures in the existing academic literature is limited, making the design of welfare-improving policy interventions difficult (D’Aguanno et al., 2021).

Which specific measures facilitate risk-reduction strategies?

Several specific measures can be taken, both by private companies and governments, to achieve the strategies discussed above. This section summarises them briefly.

Private companies have many ways to reduce risks to their supply chains

Supply chain management literature has long identified numerous measures that companies can undertake to reduce risks to their supply chains (Sáenz and Revilla, 2014; Kamalahmadi and Parast, 2016; Sá et al., 2020). They include designing the supply chain by considering the riskiness of locations and particular suppliers but also agility to resolve disruptions. It is also frequently recommended to boost the flexibility of manufacturing processes and to rely on standardised inputs from multiple suppliers. A good practice is to establish redundant production capabilities. In this respect, long‑term purchasing commitments are a good way to incentivise capacity building and lowering prices by alternative suppliers (Shih, 2020). Finally, the literature advises optimising stockpiles.

Private firms should strive to gather precise, extensive and timely information, including about warehousing, inventory and transportation (Kamalahmadi and Parast, 2016; Sá et al., 2020). Production processes could be classified as low, medium and high-risk based on criteria such as the impact on revenues if a certain source of supplies is lost, the time it would take a particular supplier’s factory to recover from a disruption, and the availability of alternate sources (Shih, 2020). The success of such an endeavour would depend on co-operation of suppliers and customers. The main challenge with this strategy is that collecting and analysing data by firms is costly, especially for smaller firms. Moreover, some firms may not be willing to share data given market sensitive information.

Available, though relatively scant, evidence on improving resilience suggests that firms in recent years, and in particular after the COVID-19 crisis, have expressed a preference for improving their inventory management and for diversifying supplies rather than re/near-shoring production. Several business surveys have indicated that companies in advanced economies mostly increased stockpiles and shifted from just‑in‑time to just‑in‑case inventory management (Alicke, 2021 Asian Development Bank, 2021; Nordström, Elfving and Nilsson, 2021; BCI, 2021; EBRD, 2022) (Figure 2.8).19 Some companies also planned to diversify their suppliers, including from domestic sources. However, few companies considered re‑shoring factories. This could be rationalised by the temporary nature of the COVID-19 shock, sunk costs and the desire to maintain proximity to large emerging markets, in particular China. Such outcomes are consistent with firm‑level analysis of Italian multinationals in response to the COVID‑19 shock (Di Stefano et al., 2022) and a modest tendency for re-shoring prior to the COVID‑19 recession (De Backer et al., 2016). However, re-shoring could intensify with increasing geopolitical polarisation in the world economy and increased automation, and it may be a non-linear process (Every and van Harn, 2022).

Figure 2.8. Companies' intentions and implemented actions to boost supply-chain resilience

Governments could also play a role

Improving monitoring of risks and stress-testing is key

Designing measures to improve resilience and robustness of supply chains should be based on a thorough cost-benefit analysis, requiring in-depth understanding of risks. As discussed above, several dimensions of GVC’s exposures are not comprehensively measured yet. Thus, there is scope for improvement in this area. Governments could help to co‑ordinate data collection, analyse them and distribute results. Several such initiatives have already been taken or are being planned (Box 2.2).

Governments can also collaborate with private firms to promote standards of conduct to reduce risks of supply chain disruptions (robustness) and minimise negative effects once such disruptions materialise (resilience) (OECD, 2021). Such collaboration could be built on the responsible business conduct framework, in line with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and OECD due diligence guidance (OECD, 2018).

Drawing on the experience in the financial sector after the global financial crisis, it has been suggested that governments could also play an active role in developing stress tests for essential supply chains (OECD, 2020; Simchi-Levi and Simchi-Levi, 2020; D’Aguanno et al., 2021). Such initiatives could in principle help increase the transparency of complex GVCs by improving the timeliness and granularity of data needed for monitoring vulnerabilities, and harmonising data. The results of such stress tests could be used for setting requirements for suppliers of essential goods to implement contingency plans in case of supply disruptions. The benefits of such an exercise could be strengthened by international co‑operation, where multilateral organisation could play an active role.20 However, given the considerable heterogeneity of sectors and firms and the large number of unsupervised manufacturing companies (compared with financial institutions), comprehensive stress-testing would not be realistic and could imply high compliance costs for companies. Thus, authorities could rather select a few key sectors or branches and focus on the largest producers. Moreover, it is not clear how such stress tests could be designed, what could be a meaningful and universal metric for assessing firm performance, and how to define shocks.

Governments can help reduce GVC risks but some measures can be costly and ineffective

A universal policy approach to reduce GVC risks is difficult to design given considerable heterogeneity across sectors and firms. In general, governments have three broad sets of direct measures to support risk-reducing strategies. They could be part of industrial and innovation policies. Most such policies focus on re/near/friend-shoring, with fewer measures aimed at diversification and adequate inventories. These measures vary in effectiveness and side effects. They should be tailored to specific problems for specific industries and products.

Financial incentives: governments could encourage re-shoring by imposing tariffs on specific imported products (Dong and Kouvelis, 2020; Feng et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023); taxing profits from off-shore activities; and/or by providing subsidies or tax credits to support domestic production and diversification (Grossman, Helpman and Lhuillier, 2021; Evenett and Fritz, 2021; Xie et al., 2022). Financial incentives could also target domestic innovation and development of production capacity, indirectly encouraging re‑shoring. Governments could opt for horizontal measures, such as carbon taxes and preferential tariff rates for near‑shored products, affecting broader categories of goods and services (European Union, 2021).

Regulatory measures: Governments could impose local content requirements (LCRs) to encourage re‑shoring. Such measures require firms to use domestically-manufactured goods or domestically‑supplied services in order to operate in an economy. There has been a substantial increase in the use of LCRs in recent years, as governments tried to achieve a variety of policy objectives, including employment, and industrial and technological development (OECD, 2019).21 LCRs could be used as a condition for obtaining subsidies, like is the case of for the US Inflation Reduction Act (Box 2.2), or be part of government procurement policy. Governments could also oblige private companies to maintain pre-defined stocks of critical products, including of pharmaceuticals, oil and gas. Stockpiling requirements could involve financial compensation or be part of public procurement conditions (European Union, 2021).

Direct government control: Governments can manage strategic stockpiles for economic and strategic purposes themselves. Many governments maintain stockpiles of critical supplies such as fuel and medical supplies.22 Countries should strive to ensure that their national stockpiling strategy aligns with the requirements of their supply chains and that the contents of stockpiles are updated to reflect the demands of industry. In Japan, the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security oversees the National Rare Metal Stockpiling Project in collaboration with industry as a safeguard against interruption of supply. In March 2020, the government announced an intention to review how stockpile targets are set and to set them exclusively for government stockpiles, no longer including industry stockpiles (IEA, 2022). The United States also maintains the National Defense Stockpile with the stated mission to “decrease and preclude dependence upon foreign sources or single points of failure for strategic materials in times of national emergency.” In March 2022, an agreement expanding the remit of the stockpile to include materials critical for clean energy technologies was signed (IEA, 2022).

Governments could continue using regional trade agreements (RTAs) to encourage near/friend‑shoring. RTAs have been actively used in the past two decades and cover more than half of international trade (Lee, Mulabdic and Ruta, 2019; Mattoo, Rocha and Ruta, 2020; OECD, 2020). They involve preferential tariffs to partners within the trading block but could address also several frontier issues related to digital trade, anti‑corruption, investment, environmental standards, state‑owned enterprises and intellectual property rights. Thus, they could be effective not only in reducing trade costs but also in building closer economic co-operation based on similar rules and thus nourishing trade integration and national security. Granting preferences in government procurement and incentives programmes among allies could be another way to promote friend-shoring.23

Box 2.2. Selected public policy initiatives motivated by GVC risk-reducing objectives

Improving monitoring of GVC risks and stress-testing

There are still gaps in understanding of GVC risks and governments can plan an active role in filling in these gaps. Several governments initiatives to co‑ordinate data collection and analyse them have already been taken or are being planned.

The US government undertook risk reviews of supply chains with a particular emphasis on semiconductors, high‑capacity batteries, critical minerals and strategic materials and pharmaceuticals and active pharmaceutical ingredients (The White House, 2021). These reviews identified goods and services needed for the supply chains to function; risks that could disrupt these supply chains; and the resilience of American manufacturing towards the risks identified. The reports also considered allied and partner actions and made recommendations on how supply chain resilience can be improved.

The EU has also engaged in a review of “strategic dependencies”, including six specific in-depth reviews,1 as part of the 2021 update to the 2020 Industrial Strategy. Strategic trade dependencies have been identified through an initial bottom-up quantitative analysis of the EU’s total trade flows to identify sectors where the European Union was reliant on a limited number of suppliers. This was followed by qualitative assessments of sectors and ecosystems that may be of strategic significance and the dependencies within these sectors that drive this exposure (European Commission, 2021). There are also calls in the European Union for establishing an early warning system to anticipate shortages of strategic inputs, by introducing regular information exchange obligations, in the context of the forthcoming EU Critical Raw Materials Act. The EU Chips Act establishes a monitoring and crisis response mechanism with respect to Europe’s supply of semiconductors (see below).

Increasing resilience by diversifying domestic and international suppliers

Concerns over the resilience of supply of manufactured goods that are critical inputs for the economy due to high concentration of production abroad have led some governments to support domestic production.

The United States introduced the US CHIPS and Science Act for the development of domestic semiconductors production capacity. The CHIPS and Science Act authorises over $52 billion over ten years (0.22% of annual GDP) in incentives to increase the production of semiconductors and the construction of fabrication facilities in the United States. These incentives include tax credits for investment in manufacturing, sectoral R&D funding and funding for education and skills (Cooper, 2022). Alongside the CHIPS and Science Act, the United States also passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to, among other goals, reduce carbon emissions in the transport sector by subsiding sales of electric vehicles. To support the development of secure supply chains for the United States’ supply of electric vehicles, the vehicle, the vehicle’s battery and the battery’s critical minerals must meet thresholds for construction or sourcing in North American or from trusted trade partners to be eligible for the full suite of available subsidies (The White House, 2023).

Likewise, the European Commission has proposed the European Chips Act. The proposal is based on a three-pillar structure: a “Chips for Europe” initiative which seeks to improve Europe’s chips pipeline at all steps of the value chain; “security of supply” focussed on strategic manufacturing facilities; and monitoring and crisis response, which establishes a monitoring and crisis response mechanism with respect to Europe’s supply of semiconductors. The act provides derogations to state aid rules for key facilities, provides €3.3 billion (0.02 % of GDP) in EU funds to relevant projects, and seeks to rationalise investment by member states. The European Commission intends to mobilise €43 billion (0.3% of GDP) in public and private funds through the act (Ragonnaud, 2022).

The Republic of Korea launched its Materials, Parts, Equipment 2.0 Strategy in July 2020 to prepare the economy for shifts in global supply chains after the COVID-19 pandemic. The government committed to spending 1.5 trillion won over five years (0.08% of annual GDP) on R&D and offered direct support to firms to cover relocation costs, with additional support provided to firms that relocate outside the Seoul region and those that build smart factories (Szczepański, 2021).

Improving security of critical minerals

Several economies have drawn up or are planning strategies to improve their security of supply of critical materials.

In the United States, these strategies generally aim at: developing recycling and reprocessing technologies and alternative technologies to limit the use of critical materials; expanding the production and processing capacities; and enhance international trade and co‑operation regarding critical materials (U.S Department of Commerce, 2019).

Similar objectives are likely to be part of the forthcoming EU Critical Raw Materials Act. The European Union has established the European Raw Materials Alliance which brings together a range of relevant stakeholders to attract investment into the supply chains, foster innovation and support recycling and the circular economy.

Canada seeks to leverage its substantial reserves of minerals in a sustainable and responsible manner. The Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan focusses on promoting investment, and the Green Mining Innovation Initiative intends to accelerate the development of green mining technologies(IEA, 2021).

However, countries, frequently not in the OECD, have also implemented protectionist measures. The number of export restrictions on critical raw materials increased globally more than five‑fold over the last decade (Kowalski and Legendre, 2023). Consequently, about 10% of the global value of exports of critical raw materials faced at least one export restriction measure in recent years. Such policies could have negative spillovers (Chen, Hu and Li, 2021).

____________

1. These were raw materials, active pharmaceutical ingredients, li-on batteries, clean hydrogen, cloud and edge computing, and semi-conductors.

Friend-shoring may be ineffective. Strategies to encourage friend-shoring may be undermined by parallel policies to encourage re‑shoring if partners perceive subsidies and tariff barriers as protectionist in intent and introduce corresponding measures (Echikson, 2022). Furthermore, commentary on friend‑shoring elements of the US Inflation Reduction Act (Box 2.2) suggests that manufacturers would find it difficult to meet the requirements to benefit from tax credits and that the narrow list of eligible countries would limit their capacity to benefit from it (Harput, 2022).

Scant empirical evidence on the effectiveness of the government policy measures to encourage re‑shoring and friend‑shoring is mixed.

Re-shoring policies pursued in the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan in recent years have been found to be only modestly effective (European Union, 2021). In particular, tariff policies are likely to have limited effectiveness for promoting re-shoring, especially if there is uncertainty about their duration and size. While some manufacturing jobs have been indeed re‑shored and capital investment increased, off-shoring still continued and dominated the macroeconomic outcomes (De Backer et al., 2016).

LCRs have a predominately negative impact on economic development and trade, even if they could help achieve short-term government’s objective (OECD, 2019). They result in long-run inefficiencies not only in the affected sector but also in the rest of the economy (Stone, Messent and Flaig, 2015). These inefficiencies ultimately reduce job growth and opportunities to achieve economies of scale and to innovate, undermining objectives for imposing LCRs.

Similarly, changes in the regional value contents of car manufacturers following the adoption of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) did increase the proportion of imports of these products into the United States that came from Mexico and Canada (Hsu, Li and Wu, 2022). However, firms were much more likely to near-shore non-ICT elements of production. This aligns with the observation that ICT production is capital intensive and, therefore, less attractive for near‑shoring.

The government measures discussed above, in principle, should be implemented if their costs are expected to be lower than their benefits in terms of higher resilience (OECD, 2020). However, due to the complexity of modern supply chains, it is very difficult for governments to fully evaluate policies aimed at building resilience and the distortions these policies create (Grossman, Helpman and Lhuillier, 2021).

The main concern about distortions relates to efficiency effects of policies aimed at reducing foreign exposures as they can impose significant welfare losses (Levine, 2012). As discussed above, replacing imports with domestic production could negatively affect prices, productivity and the variety of products available. Adverse economy-wide consequences of protectionist policies in specific sectors are likely to be the largest for the most central sectors in a given supply chain. This reflects the fact that many remaining sectors are dependent on inputs from them (Grassi and Sauvagnat, 2019). This is important as calls for government support are particularly strong in several of the central sectors, including semiconductors (Box 2.2). Increased policy interventions to reduce foreign dependencies could also raise business uncertainty, with negative implications for investment and employment. It is also possible that government measures could lead to overinvestment in resilience, resulting in lower levels of production. Such an outcome is particularly likely if governments assume that the private sector underinvests without sound evidence (Grossman, Helpman and Lhuillier, 2021).

Such concerns are equally present for policies driven by national security considerations as evaluating the economic costs and effectiveness of such policies is challenging. National security rhetoric has been increasingly influencing economic policy and in an increasing number of areas (Murphy and Topel, 2013; Heath, 2020).24 National security has become more intertwined with international economics and foreign policy (Lind, 2019) and has been used as argument for industrial and protectionist policies to buttress state control, self-sufficiency and resilience. In principle, threats to national security can justify implementing measures to provide insurance against negative geopolitical events or acting to prevent such undesirable events (see above). However, in practice, risks of geopolitical events and the associated economic costs are difficult to evaluate, even if, ex-post, such costs may turn out very high.25 Besides, some policy measures, especially if taken unilaterally, may prove ineffective in ensuring security objectives.26 To minimise risks that such policies will be costly for taxpayers and consumers, objective and thorough evaluations are needed.

Protectionist policies could reduce international co-operation and thus hinder achievement of social and environmental objectives at a global scale. Trade and financial integration facilitate international co‑operation. In contrast, if re-shoring and friend-shoring-oriented government policies result in an economically and geopolitically fragmented world, international co‑operation in several areas would be affected negatively.

It could be more difficult to make a co-ordinated response to climate change (Rajan, 2022). Achieving and enforcing international agreements on climate change mitigation policies is easier in an economically integrated world, with few barriers to trade and investment. Protectionist measures and geo-strategically motivated sanctions lead to geopolitical rivalries and mistrust. Moreover, deglobalisation could also hinder the development of technologies and production of goods needed to accelerate the decarbonisation process. Open globalisation could help to facilitate the reallocation of production in the future from the climate-hit places to those less affected by climate change.

Inward-oriented policies could reduce knowledge spillovers and academic co‑operation, with negative consequences for technological progress and productivity growth (Cerdeiro et al., 2021; Góes et al., 2022).27 Countries closing themselves to international trade would likely hinder openness to ideas and people (Iakovou and White III, 2020). Consequently, they could become less attractive as innovation centres and as employers for an internationally mobile, talented workforce, to the benefit of other countries (Kato and Sparber, 2013; Glennon, 2020). This could be particularly consequential in advanced economies with rapidly ageing populations and thus with shrinking work force.

Protectionist policies by one country or economic area could result in other countries adopting similar measures that could magnify welfare losses from a less integrated world economy. Proliferation of tit-for-tat policies could upend the international system of trade and investment that has been built over past decades. Moreover, there is a risk that demands for protectionist measures could increase with domestic companies becoming less competitive as a result of re-shoring policies (OECD, 2020).

Given the many possible side effects and risks of governmental policies, it would be good to subject such measures to comprehensive evaluation and consultations, involving international organisations, academic experts, regulators and industry representatives (European Union, 2021).

Bibliography

Acemoglu, D. and D. Autor (2011), Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings, Elsevier, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169721811024105.

Acemoglu, D. and P. Azar (2020), “Endogenous Production Networks”, Econometrica, Vol. 88/1, https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta15899.

Acemoglu, D. et al. (2012), “The Network Origins of Aggregate Fluctuations”, Econometrica, Vol. 80/5, https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta9623.

Aksoy, C. et al. (2022), Reactions to Supply Chain Disruptions: Evidence from German Firms, https://www.econpol.eu/publications/policy_brief_45.

Alicke, K. (2021), How COVID-19 is reshaping supply chains?, McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/how-covid-19-is-reshaping-supply-chains.

Allianz SE (2021), The Suez canal ship is not the only thing clogging global trade, https://www.allianz.com/en/economic_research/publications/specials_fmo/2021_03_26_SupplyChainDisruption.html (accessed on 23 January 2023).

Altomonte, C., I. Colantone and L. Bonacorsi (2018), “Trade and Growth in the Age of Global Value Chains”, SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3295553.

Antràs, P. (2020), De-Globalisation? Global Value Chains in the Post-COVID-19 Age, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.3386/w28115.

Antràs, P., T. Fort and F. Tintelnot (2017), “The Margins of Global Sourcing: Theory and Evidence from US Firms”, American Economic Review, Vol. 107/9, pp. 2514-2564, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141685.

Ardelean, A., M. Leon-Ledesma and L. Puzzello (2022), “Growth Volatility and Trade: Market Diversification vs. Production Specialization”, Discussion Papers, No. 2022-11, Monash Business School. Department of Economics.

Arriola, C. et al. (2020), “Efficiency and risks in global value chains in the context of COVID-19”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1637, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3e4b7ecf-en

Asian Development Bank (2021), Global Value Chain Development Report 2021:, Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines, https://doi.org/10.22617/tcs210400-2.

Autor, D., D. Dorn and G. Hanson (2013), “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 103/6, pp. 2121-2168, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42920646.