People’s mental health and the material conditions that shape their lives and livelihoods today and into the future – in particular income, debt, macro-economic shocks; work and job quality; and housing – are intricately linked. Poor material conditions lead to the onset or worsening of mental health outcomes, while at the same time, those experiencing mental ill-health are more likely to suffer worse financial, labour market and housing outcomes. Policy interventions that can simultaneously improve mental health and move people out of poverty include: increasing the affordability and ease-of-access to a range of social services; better integrating mental health and employment services; and providing public housing that meets the needs of those experiencing mental ill-health.

How to Make Societies Thrive? Coordinating Approaches to Promote Well-being and Mental Health

2. Risk and resilience factors for mental health and well-being: Material conditions

Abstract

Income and wealth, work and job quality, as well as housing and neighbourhood amenities make up the material conditions that shape households’ well-being. Each of these well-being dimensions is influenced by, and in turn influences, mental health outcomes. Deprivations in material conditions can lead to worsening mental health and the development of specific conditions, such as anxiety and/or depression, while policy interventions to support financial, employment and housing resilience can bolster positive mental health and lead to improved outcomes for those with psychological symptoms. It is not just people’s current material conditions that matter: systemic aspects of economic capital – which include macroeconomic phenomena such as income inequality, aggregate levels of household and public debt, business cycles and inflation – also directly influence population mental health.

2.1. Income, wealth and broader macroeconomic conditions

Low income and poor mental health often co-occur. OECD research has shown that, across member countries, people with severe mental health conditions are 83% more likely to live in low-income households than would be expected if those with mental health challenges were evenly placed across the income distribution. Conversely, those without a condition are 12% less likely (OECD, 2021[1]). Systematic reviews have shown that people with the lowest incomes are 1.5 to 3 times as likely to report symptoms of depression, anxiety or other common mental health conditions, as compared to those with the highest incomes (Ridley et al., 2020[2]; Lund et al., 2018[3]). Income poverty is also associated with higher rates of deaths of despair.1 Suicide attempts are more common in low-income households (Sareen et al., 2011[4]). In the United States and Australia, low-income individuals are more likely to use opioids, and in the United States the risk for opioid overdose is significantly higher for individuals who are diagnosed with depression and have been prescribed opioids (OECD, 2019[5]); overdose deaths are also more heavily concentrated in poor areas (Kneebone and Allart, 2017[6]).

In addition to determining what people can afford today, having a sufficient disposable income helps to smooth consumption and build future wealth, which then allows for long-term investment in economic and human capital (e.g. in property, education and health). It also functions as a backstop against future unforeseen events (e.g. accidents, illness, unemployment) and can act as a safeguard against some of the risk factors for poor mental health. At the same time, poor mental health can hinder one’s ability to shore up financial resources to invest in the future. A society’s broader macroeconomic circumstances, which affect the sustainability of economic well-being, set the conditions for people to thrive and feel mentally well. It is important for policy makers interested in improving mental health via these channels to keep in mind that income, wealth and the macroeconomic environment are directly amenable to policy intervention, for instance, via taxation, social services and monetary policies (Box 2.1).

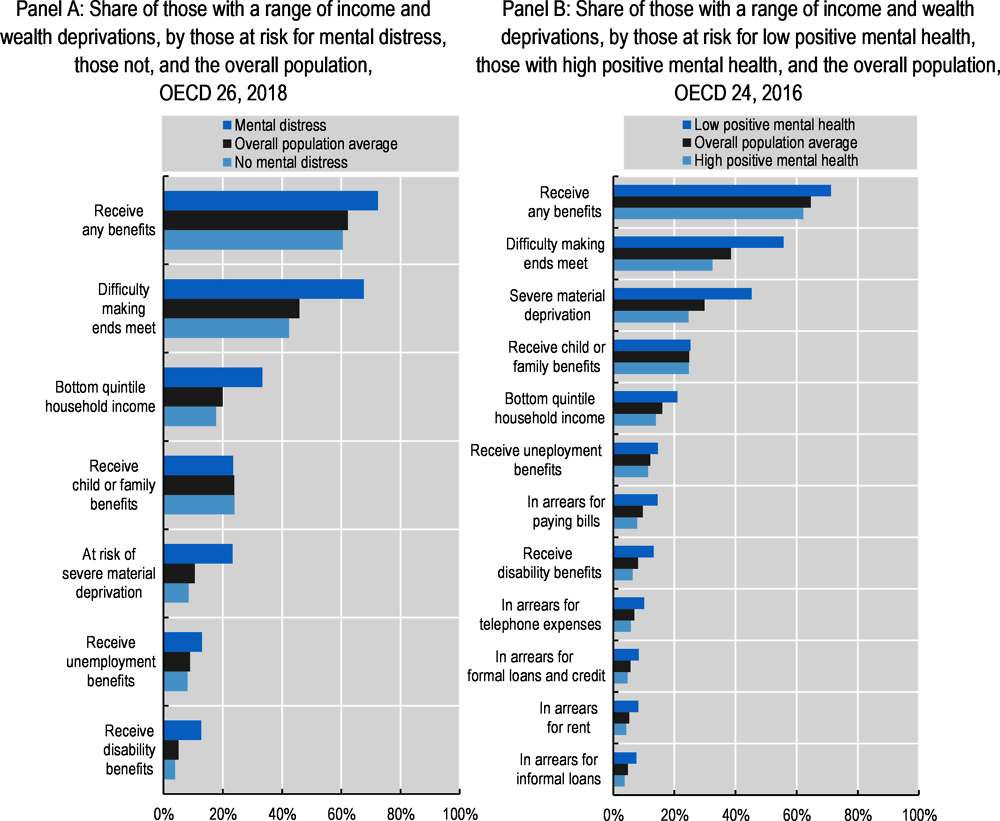

Both mental ill-health and positive mental health are strongly associated with income and wealth outcomes (Figure 2.1). Generally speaking, people at risk for poor mental health are more likely to experience lower income and wealth outcomes, compared to those not at risk. The relative gaps between those at risk for poor mental health and those not at risk (whether using mental distress (Panel A) or low levels of positive mental health (Panel B) as the mental health outcome measure of interest) are largest for people receiving disability payments, i.e. those who are unable to work due to health problems. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that these individuals suffer from the confluence of both health (mental and physical) and material deprivations. Large gaps also exist when considering financial constraints (being at risk for material deprivation, having difficulty making ends meet) and being in debt (those with worse mental health are twice as likely to report being in arrears for various expenses).

In the case of low vs. high levels of positive mental health (Panel B), there are distinct gaps when measuring the share of people who fall in the bottom quintile of the income distribution. However, these gaps are smaller than those for perceived financial instability: this suggests that the absolute level of income matters less for a person’s positive mental health than one’s perceived ability to get by. For mental ill-health (Panel A), the opposite is true: relative gaps in mental distress are larger for low household income than for reported difficulties in making ends meet.

Figure 2.1. Both mental ill-health and positive mental health are closely related to income and wealth status

Note: In Panel A, risk of mental distress is defined using the Mental Health Index-5 (MHI-5) tool. In Panel B, positive mental health is defined using the World Health Organization-5 (WHO-5) tool. Refer to the Reader’s Guide for full details of each mental health survey tool, for how each well-being deprivation is defined and for which countries are included in each OECD average.

Source: Panel A: OECD calculations based on the 2018 European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (n.d.[7]) (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions; Panel B: OECD calculations based on the 2016 European Quality of Life Surveys (EQLS) (Eurofound, n.d.[8]) (database), https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-quality-of-life-surveys.

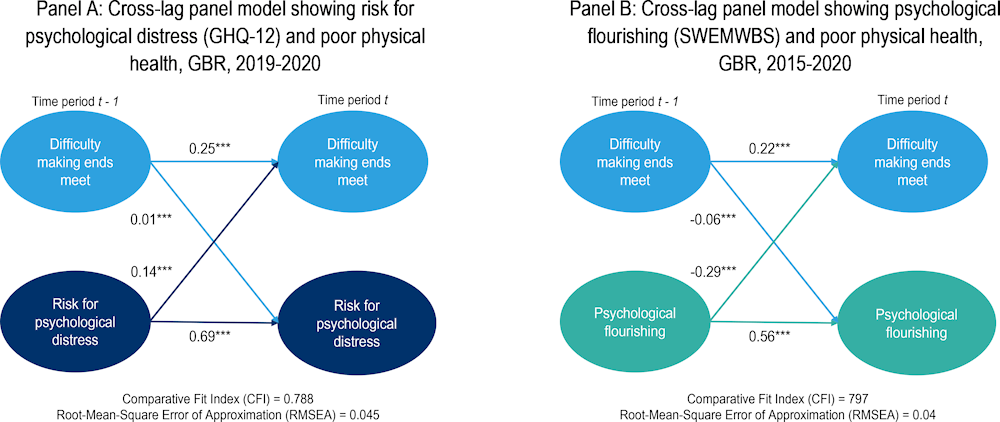

The mechanisms underpinning these associations are complex, and move in both directions, often simultaneously. Using data from the United Kingdom, the bidirectional relationship between income and mental health is illustrated in the cross-lagged panel model below (Figure 2.2). Cross-lagged panel models are useful to illustrate how the causal relationship between two variables – here, mental health outcomes and experiencing difficulty making ends meet – moves in both directions simultaneously. As is shown here, the impacts of mental health on financial insecurity are significant in both directions; however, the negative impact of previous mental ill-health on current financial insecurity is much larger than the impact of previous financial insecurity on current mental ill-health.

Figure 2.2. Previous experience of poor mental health is a predictor for current financial precarity – and vice versa, though not as strongly

Note: The model is adjusted for the following time-invariant covariates: age, sex, education, ethnicity, urban/rural. Coefficients are standardised. Difficulty making ends meet is defined as those reporting they are finding it “very difficult” or “quite difficult” to manage financially. The data included come from waves 9 and 10 (Panel A) and waves 7 and 10 (Panel B) of the UKHLS survey; the waves are different across panels due to data limitations. GHQ-12 measures psychological distress on a scale from 0 (least distressed) to 12 (most distressed). SWEMWBS measures positive mental health, ranging from 9.5 as low psychological well-being to 35 as mental flourishing. All analyses were performed using Mplus and the R “MplusAutomation” package. More details on the models can be found in the Reader’s Guide.

Source: University of Essex (2022[9]), Understanding Society: Waves 1-11, 2009-2020 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009. [data collection]., 5th Edition. UK Data Service., https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/.

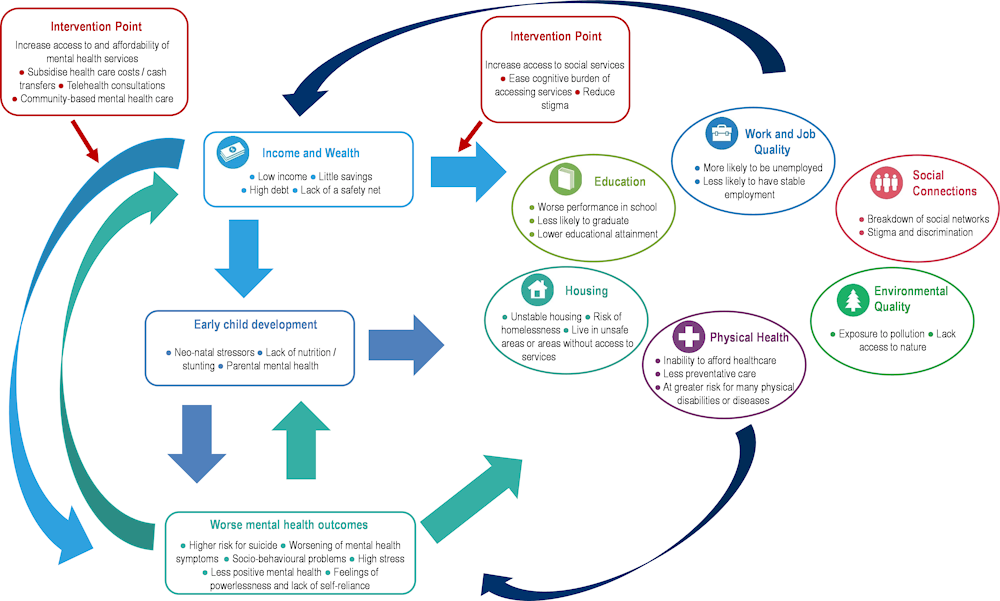

The two-way relationship between income poverty and mental health is often described as a cyclical vicious circle: worse mental health inhibits one’s ability to shore up financial resources or find employment opportunities, while at the same time the chronic stress and instability of monetary poverty can lead to the onset or perpetuation of mental disorders (WHO, 2014[10]; WHO, 2022[11]; Clark and Wenham, 2022[12]). Each process exacerbates the other, worsening outcomes across all dimensions of well-being. These mechanisms are described in Figure 2.3 below, and in more detail in the following sections, along with possible intervention points to break the cycle between material deprivation and mental ill-health. Interventions include breaking down barriers to the access of mental health care services by increasing affordability and expanding the types of services available and making social service systems more user-friendly to encourage up-take (Box 2.1).

Figure 2.3. The relationship between low income and mental health outcomes is cyclical

Note: A stylised depiction of the cyclical relationship between poverty, well-being deprivations and poor mental health outcomes. Potential policy interventions are noted in red.

Poor mental health makes it harder to escape from monetary poverty

Mental health can influence income both directly and indirectly, as the presence of specific conditions inhibits one’s ability to shore up financial resilience and tempers educational attainment and labour market participation, lowering lifetime earnings. A national cohort study in Finland found that being diagnosed with a mental health disorder2 between the ages of 15 and 25 is associated with significantly lower earnings and income over the subsequent three decades, primarily as a result of lower education and greater likelihood of experiencing unemployment (Hakulinen et al., 2019[13]). Research in the United States suggests that people with serious mental illnesses earn around USD 16 000 less than their peers with no such conditions, totalling more than USD 190 million for society as a whole over a 12-month period, primarily due to worse employment outcomes (e.g. higher likelihood of unemployment and lower earnings when employed) (Kessler et al., 2008[14]). Workers with mental health conditions are more likely to have higher rates of absence and to be less productive while on the job (OECD, 2021[1]) (see also Section 2.2 on work and job quality), in part because of increased fatigue, an inability to concentrate and less motivation (Ridley et al., 2020[2]).

The cognitive and behavioural changes stemming from mental illnesses can themselves impact earnings potential, beyond poor job performance. Poverty in and of itself can lead to deficiencies in cognitive functioning: research has shown that cognitive performance declines in times of more acute income poverty, which researchers theorise is due to the fact that the mental resources needed to deal with poverty concerns lead to less brain space for other tasks (Mani et al., 2013[15]). These issues can compound for those experiencing both poverty and mental health conditions. Those with mental ill-health may be more likely to avoid making active choices, to excessively ruminate over options or to avoid risk-taking (Gotlib and Joormann, 2010[16]) – all of which may lead to their ending up with lower income and worse economic outcomes. These cognitive impacts make quotidian choices and activities mentally taxing, and potentially paralysing for those with mental health conditions (Ridley et al., 2020[2]), which then perpetuates the cycle of poverty. Policies designed to target, or to include, those with poor mental health need to account for diminished cognitive functioning, for example by decreasing the cognitive burden of signing up for social benefits (Box 2.1).

Just like poverty itself, poor mental health can lead to social isolation, as a result of the stigma and discrimination surrounding a range of conditions (Pescosolido et al., 2013[17]). Those with mental ill-health may be excluded from social networks: in addition to loneliness and social isolation leading to the worsening of existing symptoms (see Chapter 4), the breakdown in social connections can mean less access to informal networks that provide employment and earnings opportunities (Ridley et al., 2020[2]). There can be more direct impacts on employment and income (Sharac et al., 2010[18]). For example, a study in New Zealand found that job seekers reported losing out on job offers after disclosing their mental health history to prospective employers; hired individuals felt discriminated against in the workplace by colleagues; and those seeking loans reported discrimination from financial institutions, in the form of rejected applications for mortgages or insurance policies or being charged higher fees or premiums (Peterson et al., 2007[19]).

Experiencing mental illness also has direct financial implications in terms of out-of-pocket health expenditures: not only directly, through the need for mental health care, but also because mental illnesses often co-occur with other physical health conditions that necessitate treatment (Scott et al., 2016[20]). Conversely, access to treatment can both alleviate symptoms of a mental disorder as well as improve material outcomes. Indeed, a systematic review of 39 clinical trials conducted in lower- and middle-income countries found that pharmacological and/or psychosocial treatment interventions can improve patients’ economic outcomes, too (Lund et al., 2018[3]) (see Box 2.1 for policy interventions that can increase access to and affordability of treatment).

Income declines, monetary poverty and debt can cause a deterioration in mental health outcomes

The causal relationship moves in the other direction as well, with falls in income leading to worsened mental health. Income declines can lead to an increased risk for the onset of mental disorders, including a range of incident mood disorders, anxiety and substance use (Sareen et al., 2011[4]). Evidence from Great Britain found that, over a seven-year period, income reductions were associated with an increased risk for symptoms of depression, primarily due to financial strain and its associated stress (Lorant et al., 2007[21]). In severe cases, financial shocks can lead to suicide: a natural experiment in Indonesia found that a reduction in agricultural output and income due to excessive rainfall led to increased rates of depression and suicide (Christian, Hensel and Roth, 2019[22]).3 This relationship between poverty and an elevated risk for suicide has been observed in a number of countries (Bantjes et al., 2016[23]), particularly in the aftermath of negative economic shocks, including recessions and unemployment (Haw et al., 2015[24]).

The impacts of income status and income changes are most acute for the most socio-economically disadvantaged: those earning lower incomes are less able to access health-promoting goods and services and are less able to maintain a feeling of control or security over their lives (Thomson et al., 2022[25]). Low-income households were particularly hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, in that they were more likely to lose their jobs, suffer financial difficulties and suffer health risks – both increased exposure to the virus, and worse outcomes, including death, once contracting it. This helps to explain why symptoms of depression and anxiety, which were higher in general in 2020, were especially so among those experiencing financial difficulties, across OECD countries (OECD, 2021[26]).

It is not just the objective fact of lost income that hurts mental health; perceived economic insecurity can be detrimental to a range of mental health outcomes (Stiglitz, Fitoussi and Durand, 2019[27]). Evidence from panel datasets in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia has shown the strong links between economic insecurity and mental distress (Rohde et al., 2016[28]; Watson and Osberg, 2017[29]). Work from Eurostat shows that an inability to cover unexpected costs leads to significant declines in positive mental health, even after controlling for a range of objective measures, including income and employment status (Eurostat, 2016[30]; Stiglitz, Fitoussi and Durand, 2019[27]). Research has found links between food insecurity and risk for depression, stress and anxiety (Pourmotabbed et al., 2020[31]; ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health, 2022[32]), in part due to the shame associated with needing to use food banks and having to ask for assistance (Pollard, 2022[33]). Fuel poverty is also linked to lowered life satisfaction (Davillas, Burlinson and Liu, 2022[34]; ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health, 2022[32]). Furthermore, findings from the United Kingdom show that that fear or stress over the possibility of future risks to economic security can lead to even greater declines in mental health than actual instances of volatility in ones’ economic circumstances (Kopasker, Montagna and Bender, 2018[35]).

Debt is a particularly strong predictor for poor mental health outcomes (ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health, 2022[32]). A systematic review of 65 studies reports a significant positive relationship between debt and a range of mental health conditions, including depression, substance use (alcohol, drug use) and suicidal ideation (Richardson, Elliott and Roberts, 2013[36]). Another systematic review finds a strong relationship between unpaid financial obligations and heightened risk for depression and suicidal ideation (Turunen and Hiilamo, 2014[37]). The risk increases with the amount of debt: even after adjusting for income and other socio-demographic characteristics, the likelihood of developing a mental health condition increases with the size of one’s debt (Jenkins et al., 2008[38]; Meltzer et al., 2013[39]). This is due mainly to the chronic worry and stress associated with debt and financial obligations, which leads to deteriorating mental health, the onset of specific disorders and an increased risk of substance use (smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use) to self-medicate (Richardson, Elliott and Roberts, 2013[36]).

Conversely, income increases can lead to better mental health (Thomson et al., 2022[25]; Shields-Zeeman and Smit, 2022[40]). An experimental study in the United States found that income injections – in the form of casino profits – to households in American Indian reservations were associated with reductions in anxiety (Wolfe et al., 2012[41]). The effect of income increases seems to be largest when individuals move out of poverty (Thomson et al., 2022[25]). For example, increases in social security payments have been shown to decrease depressive symptoms for elderly women in low-income households (Golberstein, 2015[42]). In the context of COVID-19, swift government interventions – such as direct cash transfers and the extension of social benefits – helped to sustain OECD average household income levels, which likely prevented even further deteriorations in mental health (OECD, 2021[26]). While income injections can improve mental health, research has consistently shown that the effects of income shocks on mental health are asymmetric. That is, a fall in income will result in a greater deterioration in mental health than a rise in income of the same value will improve mental health: this is true for both mental ill-health and positive mental health (Thomson et al., 2022[25]; Clark, d’Ambrosio and Zhu, 2020[43]; Boyce et al., 2018[44]). This suggests limits to the efficacy of government intervention once an income loss has already occurred, and it shows the importance of building resilience to prevent income losses from happening in the first place.

Monetary poverty impacts a range of other well-being dimensions beyond those to do with material conditions – such as social connections, environmental quality and safety – which can themselves impact mental health (Figure 2.3) (Public Health England and UCL Institute of Health Equity, 2017[45]). For example, the stress and social marginalisation of poverty can lead to a breakdown in social networks, social isolation and loneliness, which can themselves trigger depression (Walker, 2014[46]). Furthermore, individuals experiencing monetary poverty are more likely to be exposed to crime, experience trauma, and feel unsafe or insecure in their homes, all of which can harm mental health (Ridley et al., 2020[2]) (see also Chapter 4).

Experiencing the adverse effects of poverty in early childhood is particularly detrimental to long-term cognitive development and mental health (OECD, 2021[47]; Ridley et al., 2020[2]). These relationships begin in utero: the mental health of the mother can impact the foetus, with mothers experiencing higher levels of mental distress leading to a higher likelihood of birthing infants who exhibit behavioural problems later in childhood (OECD, 2021[47]). One study found in-utero exposure to maternal stress, measured as the mother experiencing the death of a close relative while pregnant, led to an increased likelihood of the usage of behavioural medication (e.g. to treat ADHD) during childhood, and anti-anxiety medication and antidepressants in adulthood (Persson et al., 2018[48]). More particular to poverty, research has established a link between brain development and the stressors of living in a low-income environment as an infant and young child. The exposure to chronic stressors including loud noises, chaotic living environments, exposure to interpersonal conflicts among family members and physical violence combine and can contribute to cognitive, emotional and behavioural delays (Blair and Raver, 2016[49]). Given how formative the early years are, maternal health care and early childhood interventions are among the most effective for long-term positive outcomes (Box 2.1).

While the relationship between low income and mental health is well established, there are diminishing returns to positive mental health as one’s income increases. Studies of lottery winners have shown that positive income shocks lead to increases in life satisfaction (Boarini et al., 2012[50]; Gardner and Oswald, 2006[51]; Oswald and Winkelmann, 2019[52]), however, there is a limit to the extent to which income can improve mental health. The well-known Easterlin Paradox shows that, at a national cross-sectional level, higher GDP is associated with higher life satisfaction; however, when looking at trends over time, rising GDP does not lead to a concurrent rise in life satisfaction (Easterlin, 1974[53]). Life satisfaction is particularly sensitive to an individual’s relative position in the income distribution – that is, it is not the level of income received and/or lost that affects life satisfaction so much as one’s movement around a given reference point, as defined by the income and wealth of an individual’s family, friends and community members (Clark and Senik, 2010[54]; Boarini et al., 2012[50])

Broader macro-economic circumstances can directly impact mental health

On a broader societal level, it is not just levels but also the distribution of income that can influence mental health. OECD research has shown that the public cares about inequality: four out of five adults believe that income inequality in their country is too great, and inequality has been steadily growing over the past three decades (OECD, 2021[55]). This distaste for inequality can, however, move beyond just a statement of preferences, and lead to an increased societal prevalence of mental health conditions. A systematic review of 26 studies found a significant positive relationship between income inequality at a country level and the population prevalence of depression (Patel et al., 2018[56]). A similar review pointed to a positive relationship between income inequality and the prevalence of common mental ill-health conditions, especially depression (Ribeiro et al., 2017[57]).4 Countries with high income inequality may also be at risk for higher incidence rates of more severe mental health disorders, such as schizophrenia (Burns, Tomita and Kapadia, 2014[58]). The causal mechanisms are theorised to be a combination of the psychological stress brought about by inequality, anxiety relating to one’s relative socio-economic status, and the erosion of social capital in highly unequal societies, which results in the deterioration of trust and social networks (Patel et al., 2018[56]; Delhey and Dragolov, 2014[59]).

The booms and busts of the business cycle, and the economic uncertainty this brings, also matter for population mental (ill-)health. Periods of economic recession have been associated with a higher prevalence of mental health problems, including mental disorders and suicidal ideation (Frasquilho et al., 2016[60]). Evidence suggests a pro-cyclical relationship between the business cycle, psychological well-being and suicides, largely due to spikes in unemployment, economic uncertainty and identity disturbance (Chang and Chen, 2017[61]; Godinic, Obrenovic and Khudaykulov, 2020[62]; Claveria, 2022[63]). The relationship to suicide is also apparent when measuring economic conditions through changes in aggregate consumption (Korhonen, Puhakka and Viren, 2017[64]). A 2020 report on material insecurity and mental distress in the United Kingdom found that the two are closely linked, with those lacking savings much more likely to experience a range of anxiety-related symptoms (Clark and Wenham, 2022[12]).5

Life satisfaction has been shown conclusively to be negatively correlated with macroeconomic shock factors such as declining (or negative) real GDP growth, falling employment rates and inflation (Welsch and Kühling, 2015[65]; Gonza and Burger, 2017[66]; Dolan, Peasgood and White, 2008[67]). As at the individual level, such impacts are asymmetric: that is, the loss in life satisfaction engendered by a given decline in real GDP per capita will be much greater than the gain that would be brought about by an identical increase (Beja, 2017[68]; De Neve et al., 2018[69]). Volatility in the credit cycle and stock market shows similar negative impacts on individual happiness (Li, Zhong and Xu, 2020[70]; Tonzer, 2017[71]). The larger relative impact of negative shocks, coupled with general distaste for volatility, underscore the importance of stable, even if lower, economic growth for population mental health.

Interest rates and inflation impact mental health, which provides a lever for policy makers to target population mental health interventions. When Central Bank interest rates rise, there is a heightened risk of psychiatric morbidity among those with a high debt burden (Boyce et al., 2018[44]). Conversely, inflation can reduce the real value of a debt; however, inflation is not typically associated with better mental health outcomes, but rather with lowered life satisfaction (Dolan, Peasgood and White, 2008[67]), and the declines are highly heterogeneous, depending on where one is on the income distribution (Prati, 2022[72]). Following the financial and labour market disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, inflation has risen dramatically across OECD countries: in June 2022, inflation had risen to 10.3% on average, which marked the highest price increase since June 1988 (OECD, 2022[73]). This inflation has led to a fall in real household income (OECD, 2022[73]). When inflation is high, poorer households are the most vulnerable to declines in purchasing power and feel the impact of rising prices most acutely (The Economist, 2022[74]). Inflation has also directly impacted mental health through rising stress and anxiety. A July 2022 poll in the United States found that almost 90% of Americans felt anxious about rising levels of inflation (American Psychiatric Association, 2022[75]; Citroner, 2022[76]). In the United Kingdom between May and June of the same year, 77% of adults reported feeling worried about rising prices; this survey also showed that worry over inflation was correlated with higher levels of anxiety (What Works Wellbeing, 2022[77]). This is a global phenomenon: a June 2022 Ipsos poll across 27 countries found that inflation was the number one global concern, for the third month in a row (Ipsos, 2022[78]). To help alleviate the burden of inflation on the vulnerable, the OECD has recommended short-term, targeted fiscal policies. For example, to help households cover higher energy prices, means-tested transfers to those in need can be used – to last only for the duration of price pressures – rather than untargeted tax breaks on energy or price controls, which can have high fiscal costs (OECD, 2022[79]).

Box 2.1. Policy focus: Income and wealth interventions that also improve mental health outcomes

Increasing access to social assistance programmes while decreasing the cognitive burden of enrolment

In 2015, the OECD Council adopted the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy; a framework that sets out policy guidelines to prioritise and develop a whole-of-government approach to improving outcomes for individuals experiencing mental ill-health. The Recommendation calls for integrating health, education, employment and social service efforts to better address mental ill-health. Between one-third and one-half of social benefit recipients have experienced a mental health condition; for those receiving benefits in the long-term, the share is even higher (OECD, 2021[1]). Therefore, social benefits and social protection schemes are a key policy lever for addressing mental health, and indeed the bulk of the studies included in systematic reviews of the relationship between mental health and income – and the positive mental impacts of leaving poverty – look at welfare policies as the primary mechanism for improving mental health (Thomson et al., 2022[25]).

A range of social benefits, including direct monetary schemes – cash transfers, debt relief, pensions – or in-kind social assistance or social insurance schemes – health care, unemployment or workers’ compensation benefits, maternity care – that can help recipients escape the cycle of poverty can have a positive impact on mental health outcomes (WHO, 2022[11]). A few specific examples with proven benefits for mental health, which have already been implemented in some OECD member states, include the following:

Unconditional cash transfers can improve a range of quality-of-life indicators (see subsection below) (WHO, 2022[11]).

Breathing Space is a debt management initiative launched by the Treasury in England and Wales whereby debtors who are receiving mental health crisis treatment can request respite from creditor action (lasting as long as the crisis treatment, plus 30 days) (Gov.UK, 2021[80]).

Maternity leave benefits can improve maternal mental health in both the short- and long-term, with the reduction in the risk for later-in-life depressive symptoms for the mother rising in line with the generosity of the policy (defined as a combination of length of leave and the percentage of past wages that are replaced while on maternity leave) (Avendano et al., 2015[81]). Improved maternal health during pregnancy also has long-term positive impacts on the child’s physical and mental health (OECD, 2021[47]; Ridley et al., 2020[2]).

Despite the positive effects of social benefits, many individuals with mental health conditions do not apply for, or take advantage of, the benefits available to them. While some of this may be due to stigma, a lot is attributable to bureaucratic red tape: complex application processes, long and involved eligibility assessments, or falling through the cracks of the system if working in the gig or informal economy (WHO, 2022[11]). These psychological barriers – termed “sludge” (as in, the opposite of a behaviour nudge) – can significantly inhibit access to services (Thaler, 2018[82]). Policy makers can use lessons from behavioural economics to systematically assess social protection programmes to reduce the cognitive burden of accessing them and to build fault tolerance into them. Examples include cutting cognitive costs, including burdens on time and attention, by providing assistance in filling out forms or designing smarter defaults and planning prompts; creating flexibility by leaving room for error (i.e. not overly penalising an individual for incorrectly filling out a form or missing a deadline); providing regular and timely reminders to reduce the likelihood of absence or delay due to forgetfulness; and reframing processes to empower users (Daminger et al., 2015[83]; Mani et al., 2013[15]). One practical example of this is automatic enrolment in pension schemes: when switching to an opt-out (as opposed to opt-in) model, researchers found that employees with mental health conditions were more likely to participate (Arulsamy and Delaney, 2020[84]).

Universal and unconditional schemes to improve quality of life and reduce the stigma of social service use

Universal programmes – which are meant for the population as a whole, rather than a targeted sub-set – can be useful in reducing the stigma attached to social service use. Universal Basic Income (UBI) schemes are one such example of this type of programme. UBI is an umbrella term for programmes that provide recipients with a regular cash transfer, without any preconditions or requirements: i.e. recipients do not need to submit to drug testing, to be actively employed or seeking employment or to use the funds for any specific purchase. The idea is to provide people with ownership over their own financial decisions, with the assumption that they themselves are best placed to make economic decisions for their households. UBIs are distinct from unconditional cash transfers, in that they are designed for the population, rather than for a specific sub-set.

While UBIs contain the word “universal” in their name, in practice existing research has focused on pilot programmes that are only implemented in a segment of the population – typically low-income households, sometimes randomly selected as a part of a research study – and often as top-ups to existing benefits that, even when summed together, are still insufficient as a sole means of income. Multiple OECD countries have implemented some form of UBI programme, with varying transfer amounts and degrees of integration into existing benefit schemes.

Unconditional cash transfers – which, as discussed above, are similar in some respects to UBIs but are targeted to specific recipients, rather than implemented universally – can benefit a range of well-being outcomes. Such schemes have been consistently shown to decrease poverty and increase educational attainment (Hasdell, 2020[85]) – which, as this chapter and the next show, are intricately related to mental health outcomes. In terms of mental health in particular, some studies show that such programmes can lead to a decrease in hospitalisation for mental health-related reasons (Marinescu, 2018[86]), reduce the risk of psychological distress, stress, anxiety and worry, and boost self-esteem and happiness (Owusu-Addo, Renzaho and Smith, 2018[87]; Samuel, 2019[88]). However, other evidence suggests that unconditional cash transfers can increase the risk of worse mental health, as people feel socially stigmatised for participating (Hasdell, 2020[85]). Conversely, if everyone is included, there is less of a sense of being singled out (Hoynes and Rothstein, 2019[89]). This suggests that universality is an important component of UBIs that should be examined further, especially when considering mental health as an important outcome of interest.

Some degree of caution is warranted when considering the overall economic effects of UBIs. Researchers, including at the OECD, have warned that truly universal UBI schemes may have unintended negative consequences, in that the tax increases required to adequately fund them could lead to significant income redistribution by directing much larger shares of transfers to childless, non-elderly, non-disabled households than existing programmes, and more to middle-income rather than poor households, resulting in greater overall poverty (OECD, 2017[90]; Hoynes and Rothstein, 2019[89]). If UBIs prove to be untenable, future research could focus on the efficacy of unconditional cash transfers targeted to specific populations in need – in this case, low-income households in which some or all household members may be dealing with physical and mental health challenges – coupled with campaigns to combat stigma.

Increasing access to mental health care through new technology and expansion of community services

Affordability remains one of the primary reasons for which many who need mental health care services are unable to access them. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic – which has only increased demand for services – 67% of working-age adults in OECD countries with mental distress who wanted mental health care reported having difficulties accessing it (OECD, 2021[91]).

One potential avenue for reducing strain on the system is through the use of telehealth solutions and online counselling. OECD research has found that telemedicine can be an effective way to improve mental health outcomes: cognitive behavioural therapy conducted remotely has been found to be equally as effective as face-to-face treatment for conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, insomnia and excessive consumption of alcohol, as well as in reducing the symptoms of depression and anxiety (Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[92]). Remote therapy, especially for those with mild or moderate symptoms, can be more cost-effective than in-person treatment (OECD, 2021[1]). Many OECD member states introduced telehealth options for mental health care during the pandemic when in-patient services were disrupted by the influx of COVID-19 patients. These programmes were created as a stop-gap emergency measure, so more work needs to be done to integrate them into existing health care systems (OECD, 2021[1]), as, pre-pandemic, many insurance systems would not reimburse telehealth expenses (Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[92]).

Telehealth is unlikely to be appropriate in all cases, and therefore greater resilience must be built into mental health care systems to increase capacity and flexibility, while simultaneously reducing costs. The World Health Organization advocates for a system of “community-based care”, in which individuals receive treatment or counselling outside of psychiatric hospitals: for example, in a primary care clinic, via a social service office or in a local community mental health centre. Community-based care models have been shown to be a less costly approach to mental health care (OECD, 2021[91]). Furthermore, not only does this approach expand access by providing more physical locations where treatment is available, individuals are able to remain in their own homes and communities and maintain their social support networks. Community-based care can also help to reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness by keeping mental health service users in the community, rather than segregating them. It has also been shown to improve overall quality-of-life outcomes (WHO, 2022[11]). All OECD countries have either already transitioned to a community-based care model or have identified the shift as a policy priority. However, some are further along in the transition than others, and in some places significant barriers remain: for example, the need for structural changes to insurance and fee schedules, and stigma towards mental ill-health (OECD, 2021[91]). Integrating community concerns into mental health care, and having the buy-in of community leaders, can be especially important in building psychological resilience in the population (see Box 3.3 for a discussion of how this plays out in the context of climate change).

For additional policy examples in the area of income and wealth, including improving benefits systems to make them more accessible to people with mental ill-health, see Fit Mind, Fit Job (OECD, 2015[93]).

2.2. Work and job quality

Mental health is linked to a range of labour market outcomes, including both the quantity and quality of jobs. Those with a mental health condition are less likely to be employed, and when they are, are more likely to earn less and collect more working-age social benefits. Previous OECD work has estimated that the costs of poor mental health can be as high as 4% of GDP, when accounting for lowered productivity, higher absences, and increased spending on social services and health care (OECD, 2021[1]). These findings led to the adoption of the 2015 Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, which promotes a “mental-health-in-all-policies” approach to better integrate mental health services in education, workplace and social service systems (Box 2.2).

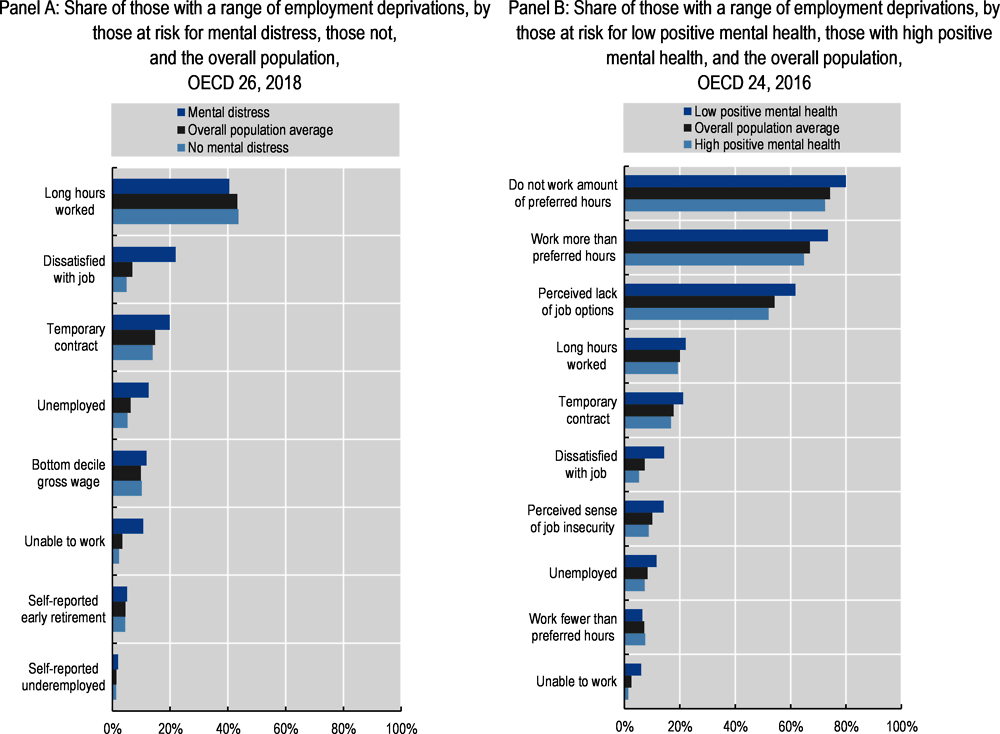

The relationship between poor mental health and worse labour market outcomes is illustrated in Figure 2.4. When measuring employment deprivations, the largest relative gaps between those with better and worse mental health outcomes are for being unable to work due to a permanent disability; those with poor mental health outcomes are also much more likely to report being unemployed, feel insecure in their employment or have a temporary contract. The relative gaps are smaller when looking at wages and earnings: for example, 12% of those at risk for mental distress report earnings in the bottom decile of the survey sample, compared to 10% of those not at risk. This suggests that looking at earnings only is insufficient to understand the relationship between work and mental health: poor working conditions, and unstable contracts, are more likely to be negatively related to mental health outcomes.

Figure 2.4. Worse mental health outcomes are associated with greater likelihood of being unemployed or on disability or of being employed in lower quality jobs

Note: The figure displays findings for the working-age population only (ages 15 to 64). For employment quality indicators (hours worked, satisfaction with job, wage levels, contract type, etc.), the sample is restricted to those who report being engaged in full-time or part-time paid work. In Panel A, risk of mental distress is defined using the Mental Health Index-5 (MHI-5) tool. In Panel B, positive mental health is defined using the World Health Organization-5 (WHO-5) tool. Refer to the Reader’s Guide for full details of each mental health survey tool, for how each well-being deprivation is defined and for which countries are included in each OECD average.

Source: Panel A: OECD calculations based on the 2018 European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (n.d.[7]) (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions; Panel B: OECD calculations based on the 2016 European Quality of Life Surveys (EQLS) (Eurofound, n.d.[8]) (database), https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-quality-of-life-surveys.

Unemployment worsens both mental ill-health and life satisfaction

Unemployment can lead to the onset of specific mental health conditions, or the worsening of pre-existing symptoms. Systematic reviews have shown that those who are unemployed – especially those who are unemployed for a long period of time – are more likely to develop depression and anxiety disorders (OECD, 2021[1]; McGee and Thompson, 2019[94]; Paul and Moser, 2009[95]) and have mortality rates 1.6 times higher than the employed (Herbig, Dragano and Angerer, 2013[96]). Research from the United States found that when county-level unemployment rates increased by one percentage point, emergency department visits for opioid overdoses increased by 7% and fatalities from opioid overdoses by 3.6% (Hollingsworth et al., 2017[97]).

Unemployment – and the financial instability it brings – is a stressful situation, and prolonged stress has been shown to negatively impact mental health (Wilson and Finch, 2020[98]). Losing one’s job can lead to lower self-esteem and greater feelings of helplessness, which social psychologists have demonstrated lead to anxiety and self-doubt, and eventually, depression (Diette et al., 2012[99]). Some studies have shown that better-educated employees who find themselves unemployed are particularly at risk for these negative emotions (Goldsmith and Diette, 2012[100]). Evidence shows that these feelings compound, and for this reason, prolonged unemployment can be worse for mental health than shorter periods of job loss (Wilson and Finch, 2020[98]; Goldsmith and Diette, 2012[100]). In addition to the psychological burden of unemployment, it also entails a loss of earnings, which can hurt financially and lead to debt, which in turn negatively impacts mental health (refer to the previous section). These negative impacts can persist over the life course: a number of studies have found that youth unemployment is associated with poor mental health (nervous and depressive symptoms, sleeping problems) later in life (Strandh et al., 2014[101]).

A study in Sweden examining the negative impact of unemployment found that the gaps in mental distress between the employed and unemployed could be partially explained by a lack of economic and social resources among the latter group (Brydsten, Hammarström and San Sebastian, 2018[102]).6 There is evidence that social services can help to mitigate these negative effects: a meta-analysis found that the negative mental health impacts of unemployment were lower in countries with more developed unemployment protection systems (Paul and Moser, 2009[95])

There is some evidence suggesting that the causal relationship is true in the opposite direction as well, with individuals experiencing severe mental health conditions being more likely to find themselves unemployed. A longitudinal study in the United States found that young people who experienced severe mental distress earlier in their lives were 32% more likely to be unemployed over the subsequent decade (Egan, Daly and Delaney, 2016[103]). A separate study in Sweden showed that the presence of mental ill-health at age 18 for males born between 1950 and 1970 predicted a higher likelihood of being unemployed in 2003: alcohol and drug dependence in adolescence had the strongest effect (Lundborg, Nilsson and Rooth, 2014[104]).

Unlike mental ill-health, the causal relationship between life satisfaction and unemployment appears to move in one direction (Boarini et al., 2012[50]). There is a considerable literature showing that unemployment leads to significant drops in life satisfaction, which persist even when controlling for loss of income (OECD, 2013[105]; Boarini et al., 2012[50]; Arampatzi et al., 2019[106]).7 This likely reflects the causal mechanisms seen in the relationship between mental health conditions and unemployment described above: losing one’s job leads to feelings of low self-esteem and helplessness, independent of income loss. The negative effects of unemployment can spill over to the next generation: a cross-sectional study of young children across North America, Europe and the Middle East found that parental unemployment was associated with significant drops in children’s life satisfaction (Hansen and Stutzer, 2022[107]).

Institutional policies can safeguard individuals against blows to their well-being in times of crisis. Preliminary evidence has shown that countries with higher unemployment replacement rates and stronger employment protection policies experienced greater life satisfaction during and immediately following the 2007-08 Great Financial Crisis (Boarini et al., 2012[50]). For instance, Iceland experienced significant negative macroeconomic shocks during the crisis yet saw little change in aggregate life satisfaction. This was likely because the country’s unemployment benefits and policies are relatively generous and provided people with a sense of stability, purpose and community involvement, all of which tempered the negative effects of unemployment (Gudmundsdottir, 2013[108]).

In addition, the impact of unemployment on life satisfaction can be context-dependent. Unemployment’s effects on an individual’s life satisfaction are closely linked to one’s peer reference group. A study using German data found that national aggregate unemployment has a small negative effect on life satisfaction for those who are employed, but no negative effects for those who are themselves unemployed. This is likely because in the context of wide-scale unemployment one feels less isolated or stigmatised by one’s lack of employment (Clark, Knabe and Rätzel, 2008[109]).

While employment can serve as a resilience factor for mental health, the type and quality of employment matter

Being employed can be a protective factor against mental health conditions. Systematic reviews have found that employment is associated with better physical health, better overall mental health and lower likelihood of having depression (Van Der Noordt et al., 2014[110]). Re-entering the workforce can lead to improved mental and physical health, with stronger impacts for the more highly educated (Schuring, Robroek and Burdorf, 2017[111]).

However, being employed is not in itself a sufficient safeguard for mental health, and the quality of the job matters – while “good” jobs can be protective, “bad” jobs are associated with worse mental health outcomes (Grzywacz and Dooley, 2003[112]).8 Those with mental ill-health are more likely to earn less, and work fewer hours than those who are not at risk for mental distress. Within the OECD employed population, individuals with mental health conditions earn on average 83% of what an individual without a mental health condition does; workers with mental health conditions are also more likely to work part-time (OECD, 2021[1]). These outcomes are not necessarily deprivations – someone with a mental health condition may choose to work fewer hours, or choose a lower paying job, to minimise work stress and have a healthier work-life balance to better handle their symptoms (OECD, 2021[1]). In fact, the OECD recommends flexible return-to-work models for individuals who have been absent due to a mental health condition, enabling employees to work shorter hours as they re-integrate themselves into the labour market. While a number of countries have introduced some form of part-time return options, there is still work to be done to better implement these programmes and expand access to them (OECD, 2021[1]; 2021[91]).

However, when part-time or temporary contracts are not the result of a deliberate choice, they can contribute to worse physical and mental health outcomes (Virtanen et al., 2005[113]), including lowered positive mental health (OECD, 2013[105]). Temporary work can be associated with depression and fatigue if the position is perceived as having poor working conditions (e.g. a noisy working environment, lack of support, compensation or lack thereof for overtime hours, lack of job training) or lacking stability (Hünefeld, Gerstenberg and Hüffmeier, 2019[114]). Workers in the gig economy, who are often piecing together income from a variety of low-paying tasks across platforms, are at risk for greater mental distress, primarily due to financial insecurity (Glavin and Schieman, 2022[115]; Gross, Musgrave and Janciute, 2018[116]) (Box 2.2). Job instability has been linked to a range of mental health conditions, including a heightened risk for suicide (Min et al., 2015[117]). Furthermore, suicide risk is higher for lower-skilled workers (Milner et al., 2013[118]) – those with mental ill-health are more likely to have lower levels of education and come from lower-income households, and thus make up a larger proportion of the low-skilled worker population. When considering positive mental health, the experience of job insecurity or labour market risk for those already employed exhibits a greater impact on life satisfaction than does the experience of actual unemployment (Clark, Knabe and Rätzel, 2008[109]).

Beyond job stability, employment in a position with low psychosocial job quality can lead to worse mental health. A national longitudinal study in Australia found that young people entering these types of jobs – characterised by lack of control, little support from co-workers or managers, high demands and complexity, job insecurity and unfair pay – saw significant declines in their mental health. Conversely, improved psychosocial job quality can promote mental health (Milner, Krnjacki and LaMontagne, 2017[119]). A separate study in Canada found similar patterns, with psychosocial work stressors associated with the likelihood of employee burnout, stress and cognitive strain (Shahidi et al., 2021[120]).

The relationship can move in the opposite direction, in that people experiencing mental ill-health are less productive at work, which can then lead to worse labour market outcomes. People experiencing mental ill-health symptoms may take more time off as a result of their condition (absenteeism), or they may be less efficient in completing tasks while at work (presenteeism) (OECD, 2021[1]). Evidence shows that employees with conditions such as depression or anxiety have poorer work performance (Plaisier et al., 2010[121]). For example, employees with depression may struggle to manage their time and have poorer interpersonal skills and less of an ability to complete physical tasks – all of which contribute to presenteeism (OECD, 2021[1]; Adler et al., 2006[122]). Mental health trainings in the workplace can teach managers how to help employees manage presenteeism by developing tailored work plans to manage workload and reduce stress (OECD, 2021[1]) (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Policy focus: Work and job quality interventions that also improve mental health outcomes

The 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy reaffirmed OECD member states’ commitment to a multi-sectoral, integrated approach to mental health care. Subsequent OECD publications, including Fitter Minds, Fitter Jobs: From Awareness to Change in Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policies (2021[1]) and A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-health (2021[91]) have outlined what countries are doing in terms of implementing integrated approaches and have set policy recommendations for how to better integrate employment and mental health systems, among others. The first two policy examples below are discussed in greater detail in (OECD, 2021[1]) and (OECD, 2021[91]).

Integrating mental health service provision into unemployment services through Individual Placement and Support (IPS) programmes

One way of integrating services across employment and health sectors is the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) programme. IPS, which is the programme with the greatest evidence base to date, has been piloted by eight OECD countries so far (OECD, 2021[91]).1 It uses a multidisciplinary team – including both employment and mental health specialists – to work with jobseekers to find employment and provide the support they need to develop the skills and training to remain in the job. IPS differs from other models of employment support in that those with mental health conditions enter employment directly and are immediately supported by the programme as they begin to work; they are not given a separate vocational training prior to entering the labour market, which can lead to segregation and less effective job retention outcomes (Metcalfe, Drake and Bond, 2018[123]). IPS has been found to be more effective than prevocational training at assisting those with mental health conditions to obtain jobs and remain in them (Crowther et al., 2001[124]; OECD, 2021[1]).

While IPS has been piloted by a number of OECD member states, only England has included it in a national plan thus far. This may be in part because IPS is resource-intensive – requiring the participation of many specialists across disciplines – which makes national scale-up either very difficult, or unfeasible. In addition, IPS in its current form focuses primarily on individuals with severe mental ill-health, and misses a segment of the unemployed population who have less severe forms of mental distress but may nevertheless still benefit (OECD, 2021[1]). One way of addressing this is to scale up current forms of IPS to include these individuals. Another avenue is to provide mental health training for existing unemployment service staff. A recent OECD survey found that 16 member states provided mental health training to unemployment staff or counsellors, but of those only one (Korea) indicated that the professionals received “a lot” of training (OECD, 2021[91]).

Encouraging employers to prioritise mental flourishing at work

Since the 2015 recommendations were published, many OECD countries have added measures of psychological distress or stress to national occupational health and safety guidelines. As is outlined in OECD (2021[1]), the policies differ across countries but include:

Required annual manager-employee “stress checks”, which are then linked to health services: i.e. if during such a meeting the employee is deemed to be at risk, they can be referred to a physician (Japan)

Toolkits for employers, including evaluation instruments and how-to guides, to promote healthy workplaces and minimise psychological distress (Colombia)

National voluntary guidelines to help employers promote mentally healthy workplaces (Canada).

OECD recommendations for improving general health in the workplace have focused on how governments can encourage employers to develop such schemes by regulation, financial incentives, guidelines and certification and award schemes (OECD, 2022[125]).

Other OECD work has sought to promote mentally healthy workplaces by engaging with businesses directly. Business for Inclusive Growth (B4IG) is a strategic initiative between the OECD and 35 large global corporations. Each member signs a pledge to pursue inclusive growth strategies by, among other things, creating supportive workplaces. Member countries have pledged to promote positive mental health at work by reducing stigma and actively supporting employee mental well-being through training and empowerment workshops, access to counselling services and self-directed learning experiences, among others (OECD, 2020[126]).

In 2022, the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organisation jointly published recommendations for best practices to prevent mental ill-health and promote good mental health in the workplace. The publication highlights a number of concrete policy recommendations, based on an extensive evidence-based literature review, tailored to different levels of interventions: organisation-level (e.g. contract type, workload, flexible working conditions), manager-level (e.g. mental health training), employee-level (e.g. mental health training, mental health awareness and literacy) and individual-level (e.g. stress management, physical health promotion, etc.) (WHO, 2022[127]).

Extending social protection schemes to platform workers

A growing number of individuals in OECD countries – up to 3% of the labour force – are a part of the gig economy, earning income by performing services relating to transport, delivery or household chores via digital labour platforms (Lane, 2020[128]). Platform work is considered a form of self-employment; therefore, these workers are typically not eligible for most social protection policies. The COVID-19 pandemic shone a spotlight on these vulnerabilities. Platform workers often performed essential services and thus had to continue working throughout the pandemic, often without sufficient Personal Protective Equipment. They also experienced significant income losses, either because of a lowered demand for certain types of gig work (e.g. transport) or because of an inability to work after having been exposed to the virus (OECD, 2020[129]). The stress and instability of gig economy work can lead to worsened mental health even in non-COVID times; the global pandemic compounded these risks.

Realising the vulnerability of these workers, many OECD country governments enacted emergency measures to ensure that gig economy workers could also benefit from cash transfers and unemployment benefits; however, many of these interventions were temporary. Governments should maintain this momentum moving forward, to strengthen occupational safety and health regulations for platform workers and to extend social protection schemes – including unemployment, maternity/paternity, health or pension benefits (Lane, 2020[128]). This will not only provide stability in gig economy workers’ financial and labour market outcomes but will also indirectly improve their mental health outcomes as well.

For additional policy examples in the area of work and job quality – including fostering employment-oriented mental health care systems, preventing workplace stress, improving mental health training and support structures at work, and managing return-to-work policies for those with mental health conditions – see Fit Mind, Fit Job (OECD, 2015[93]).

Note: 1. Countries include: Australia, Denmark, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (England only).

2.3. Housing and neighbourhoods

Housing provides residents with shelter, safety and privacy. Housing is the basis of a stable and secure life, but it entails more than a mere physical structure: housing includes the neighbourhoods and communities in which people live and the amenities to which they have access. Adequate and affordable housing has been recognised as a human right since 1948 (United Nations, 2022[130]), and it is existentially important in order for people to live well and feel well – both physically and mentally. Mental health outcomes are deeply entwined with both people’s ability to procure housing, as well as the quality of the housing and neighbourhood in which they live (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. The key tenets of housing and neighbourhoods as they relate to mental health

Note: Adapted from (HSE, 2012[131]), refer to Table 1.

Source: HSE (2012[131]), Addressing the Housing Needs of People using Mental Health Services, Health Service Executive, https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/mentalhealth/housingdocument.pdf.

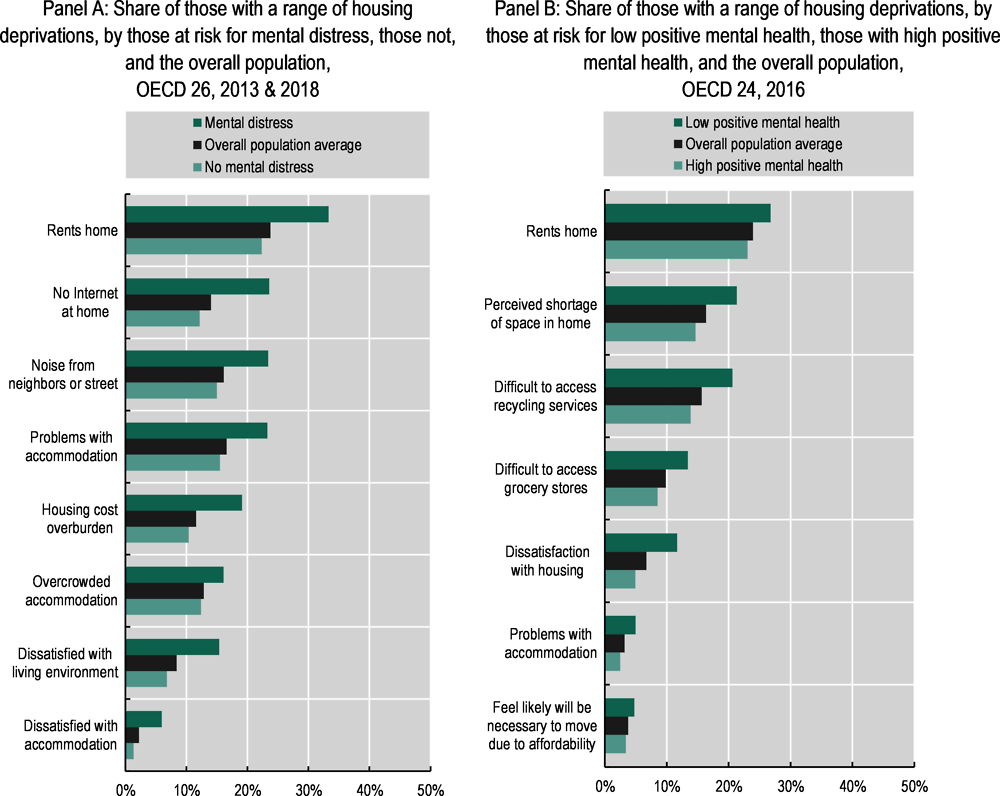

Figure 2.6 illustrates the relationship between mental health outcomes and a series of housing deprivations.9 For all housing characteristics, those at risk for mental distress (Panel A) or with low levels of positive mental health (Panel B) are more likely to report experiencing deprivations. The largest relative gaps in outcomes between those at risk for poor mental health and those not at risk are apparent when it comes to subjective indicators of housing deprivation: being dissatisfied with one’s accommodation and being dissatisfied with one’s living environment. However, these are closely followed by gaps in objective housing quality conditions: living in a structure with damp, rot or mould; living in a noisy or polluted area; or living in an area where it is difficult to access services such as grocery stores.

Figure 2.6. Those with worse mental health are more likely to report problems of unaffordable housing or poor-quality housing and dissatisfaction with living space

Note: In Panel A, risk of mental distress is defined using the Mental Health Index-5 (MHI-5) tool. In Panel B, positive mental health is defined using the World Health Organization-5 (WHO-5) tool. Refer to the Reader’s Guide for full details of each mental health survey tool, for how each well-being deprivation is defined and for which countries are included in each OECD average.

Source: Panel A: OECD calculations based on the 2013 and 2018 European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (n.d.[7]) (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions; Panel B: OECD calculations based on the 2016 European Quality of Life Surveys (EQLS) (Eurofound, n.d.[8]) (database), https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-quality-of-life-surveys.

Mental health conditions can increase the likelihood of becoming homeless, while the stress of homelessness can worsen mental health outcomes

There is a strong link between homelessness and mental ill-health. Getting accurate estimates of the prevalence of homelessness is challenging, due to differences in definitions and data collection methodology; however, recent estimates suggest that around 2.1 million people are homeless across OECD countries for which data are available (OECD, 2021[26]). Conducting surveys of the homeless population presents a number of challenges, but the efforts undertaken within individual OECD countries yield an alarmingly high prevalence of mental health conditions: up to 67% of the homeless population in Madrid had some form of mental health condition (Vázquez, Muñoz and Sanz, 1997[132]); 70% in Melbourne had some type of lifetime diagnosis (Herrman et al., 1989[133]); around 60% in Denmark had a registered psychiatric disorder; while between 35% and 50% had a substance abuse diagnosis (Nielsen et al., 2011[134]). In almost all cases, substance use – especially alcohol – conditions are most common (Schreiter et al., 2017[135]). Rates of schizophrenia and personality disorders are also significantly higher in the homeless population than in the general population (Koegel, Burnam and Farr, 1988[136]; Ayano, Tesfaw and Shumet, 2019[137]). In the United States, in areas where data are captured, the homeless die deaths of despair at significantly higher rates: in Los Angeles County, the homeless are 35 times more likely than the general population to die from drug or alcohol overdoses and eight times more likely to die from suicide (Fuller, 2022[138]), and across four states,10 the homeless have an elevated risk of opioid overdose as compared to low-income individuals in housing (1.8% compared to only 0.3%) (Yamamoto et al., 2019[139]).

A history of mental health conditions – including depressive episodes, psychiatric problems, substance use and previous suicide attempts – have been shown to increase the risk of homelessness (Nilsson, Nordentoft and Hjorthøj, 2019[140]; Moschion and van Ours, 2022[141]). Adverse childhood experiences including exposure to violence, abuse and family instability, can lead to socio-emotional difficulties, mental distress and an increased risk of homelessness (Sullivan, Burnam and Koegel, 2000[142]; Liu et al., 2021[143]). Traumatic incidents in childhood can also fragment family structures, leading to decreased social support and social networks, which in turn hurts education and employment prospects (Liu et al., 2021[143]). It is usually not the existence of a mental health condition on its own that leads to homelessness, but rather the confluence of mental ill-health and a range of other risk factors, including poverty, low education and poor physical health (refer to Section 2.1, and Chapters 3 and 4) (Sullivan, Burnam and Koegel, 2000[142]).

However, some evidence suggests the relationship moves in both directions: the experience of homelessness can also lead to the onset of mental health conditions, or the worsening of existing symptoms. In terms of direct pathways, those experiencing homelessness are less able to access services to treat pre-existing mental health conditions, which can lead to further deterioration of mental health (OECD, 2015[144]). Indirectly, homelessness is an inherently stressful and unstable experience, and research shows that the prolonged experience of elevated stress levels can lead to anxiety and depression (Hammen et al., 2009[145]; Jay Turner and Beiser, 1990[146]; Zhang et al., 2015[147]). Additionally, individuals who are homeless are more likely to experience direct stressors such as violence and assault, the trauma of which can increase the likelihood of developing a mental health condition (Riley et al., 2020[148]; Meinbresse et al., 2014[149]) (see also Chapter 4 for a discussion of how safety and violence impact mental health outcomes). A study conducted in the United States found that previous experience of homelessness was associated with higher levels of substance use, a higher likelihood of having some form of psychiatric distress, and lower self-reported likelihood of recovery from a mental illness (Castellow, Kloos and Townley, 2015[150]). The negative impacts of homelessness on mental health are not unique to adults: a meta-analysis of twelve studies in the United States found that homeless school-age children were two to four times more likely to have mental health conditions requiring clinical evaluations than were non-homeless, poor children (Bassuk, Richard and Tsertsvadze, 2015[151]). Conversely, a study in Australia found that previous experience of homelessness had no effect on the likelihood of experiencing future depressive episodes; however, among men, homelessness did lead to an increased likelihood of anxiety disorders (Moschion and van Ours, 2022[141]).

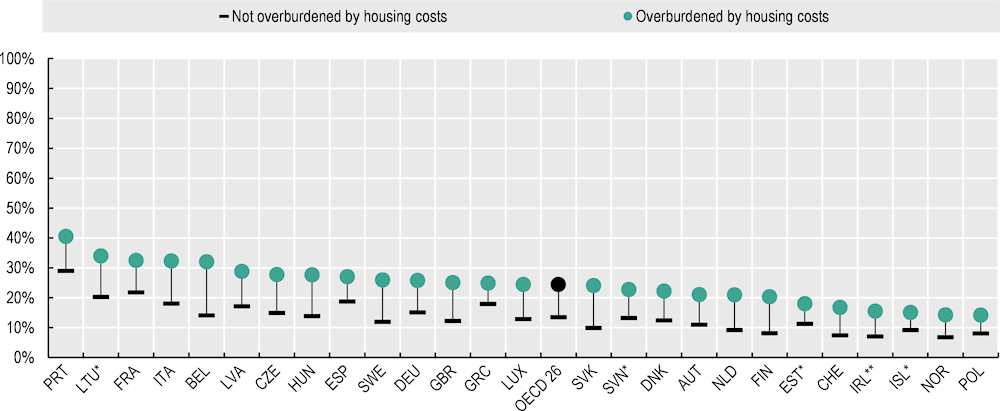

Housing unaffordability and instability are significant drivers of severe mental health conditions

Even for those who are able to secure accommodation, unaffordable housing and the instability of housing tenure can negatively influence mental health. As Section 2.1 showed, poverty and indebtedness can trigger or worsen pre-existing mental health symptoms: housing debt in particular can influence mental health as negatively as marital breakdown or job loss (Taylor, Pevalin and Todd, 2007[152]). In 26 European OECD countries, 24% of those overburdened by housing costs (defined as spending at least 40% of household income on housing) are at risk for mental distress, compared to only 14% who spend less (Figure 2.7). Both those who rent and those who own their own homes can suffer the risks of housing unaffordability. Mortgage delinquency is associated with an increased likelihood of developing depressive symptoms (Alley et al., 2011[153]), and losing one’s home through foreclosure is associated with an increased likelihood of experienced symptoms of major depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder (Mclaughlin et al., 2012[154]).

Figure 2.7. People spending more than 40% of household income on housing face a higher risk of mental distress

Note: The figure compares the mental health outcomes of those who are overburdened by housing costs (using the OECD definition of those who spend more than 40% of their household income on housing costs) and those who are not. ** indicates there are between 100 and 299 observations per country/category; * indicates there are between 300 and 499 observations. Countries in which categories have fewer than 100 observations are dropped from the figure.

Source: OECD calculations based on the 2018 European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (n.d.[7]), (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions.

Housing tenure – whether one owns or rents – can also affect both mental ill-health and positive mental health. Evidence from Australia shows that, for those in the lower 40% of the income distribution, renters experienced declines in mental health in the face of unaffordable housing, whereas owners facing similar levels of unaffordability saw no significant changes (Mason et al., 2013[155]).11 In the United Kingdom, renters reported higher rates of distress across a range of mental health indicators12 as compared to home owners (Clark and Wenham, 2022[12]). In terms of positive mental health, studies across a number of OECD countries have found that owning a home is associated with improved life satisfaction – especially for lower-income households (Zumbro, 2014[156]; Ruprah, 2010[157]; Stillman and Liang, 2011[158]). The improved mental health outcomes of home ownership may be due to higher levels of resilience to financial shocks and higher net wealth or to some degree of social prestige associated with owning one’s home, or may simply be due to socio-economic compositional differences in the sample of renters vs. homeowners (Mason et al., 2013[155]). The first channel can be addressed through measures to make housing more affordable, so that renters are also able to weather negative financial shocks and feel secure that their housing costs will remain at an affordable share of their total gross income.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments reacted swiftly to ease the financial burden of housing and prevent evictions and mortgage foreclosures from occurring in the midst of mandatory quarantine and lockdown procedures. Emergency responses included suspending eviction procedures, rent and mortgage forbearance and a moratorium on utility payments. While useful and important in the short-term, in the long-term these policies can have adverse effects on housing prices. For example, rental market restrictions during the pandemic prevented renters in vulnerable homes from losing housing at a time when they may have lost income or job opportunities. However in the long-run, these restrictions can prevent residential mobility, which depresses investment in housing, decreases the housing supply and eventually leads to higher housing prices (OECD, 2020[159]).

OECD research has focused on the need to improve the affordability of housing, and it has highlighted three key policy recommendations that governments can implement to put deflationary pressure on housing prices (OECD, 2021[160]):

1. Remove mortgage relief interest: makes home ownership less financially desirable compared to renting, which can help to lower house prices and potentially lessen the social prestige attached to ownership in certain markets.

2. Decentralise land-use decision-making processes: enables greater flexibility and responsiveness to fluctuations in demand, which can reduce housing prices significantly.

3. Ease rental market regulations: allows for greater investment in, and supply of, housing stock, in areas with more flexible land-use regulation, which can then keep housing prices proportionate to incomes.

The conditions of people’s residential space are important for their mental health

Mental health is not only associated with the presence or absence of housing: poor quality housing is associated with worse mental health outcomes. A review of multiple research studies finds that overall housing quality (metrics include structural condition, maintenance, upkeep) is related to psychological well-being (Evans, Wells and Moch, 2003[161]). Poor quality housing can lead to concerns about safety (e.g. fire hazards) and sanitation (e.g. garbage and waste removal), which can lead to higher stress and anxiety. Living in an overcrowded dwelling, with little privacy or personal space, can also negatively impact mental health (Guite, Clark and Ackrill, 2006[162]). The lockdowns associated with COVID-19 highlighted the importance of housing quality and exacerbated the negative psychological impacts of the pandemic for those living in cramped, low-quality settings (OECD, 2021[26]). A European cross-country study found that overcrowding, lack of access to outdoor facilities and living alone contributed to higher levels of loneliness, anxiety and lower life satisfaction (Keller et al., 2022[163]). Similarly, survey data from Italy collected during the first COVID-19 lockdown period show that, regardless of housing size, the poor quality of indoor housing is associated with moderate to severe symptoms of depression (Morganti et al., 2022[164]).

Children and infants are particularly vulnerable to living in poor quality housing. A large-scale programme in Mexico to replace dirt floors with cement floors found that the programme was associated with significant improvements in children’s health (less diarrhoea, parasitic infections and anaemia and increased cognitive functioning); this in part explains the finding that adults reported greater satisfaction with housing and lowered rates of stress and depression (Cattaneo et al., 2009[165]). Similarly, children who are exposed to significant amounts of lead at a young age, such as lead paint or contaminated drinking water, may suffer from a range of physical abnormalities and cognitive deficiencies, including: colic, anaemia, central nervous system problems, shortened attention span, increased proclivity to disruptive behaviour, and reduced intelligence (Bellinger, Stiles and Needleman, 1992[166]; Nilsson, 2009[167]; WHO, 2010[168]).

The relationship between housing and positive mental health is less well studied, but the evidence that does exist suggests that higher-quality accommodation is associated with greater satisfaction with housing and, in turn, overall satisfaction with life (Boarini et al., 2012[50]). A study in the United Kingdom found that excessive noise in the neighbourhood, and living in a dwelling that is damp, has rot, poor lighting and no garden access, and is subject to vandalism are all predictors of lower life satisfaction (Fujiwara and HACT, 2013[169]).

The conditions of people’s residential space are important for their mental health