Grant all stakeholders equal and fair opportunities to be informed and consulted and actively engage them in all phases of the policy cycle and service design and delivery. This should be done with adequate time and at minimal cost, while avoiding duplication to minimise consultation fatigue. Further, specific efforts should be dedicated to reaching out to the most relevant, vulnerable, underrepresented or marginalised groups in society, while avoiding undue influence and policy capture.

Open Government for Stronger Democracies

9. Provision 8: Stakeholder participation

Abstract

Provision 8 reflects a key component of an open government: the interaction between public authorities, stakeholders and citizens. Participatory processes, beyond elections, allow for the public to contribute with ideas, evidence and informed recommendations. Citizen and stakeholder participation1 differs from traditional democratic participation as, rather than selecting representatives, citizens’ and stakeholders’ needs and views are integrated throughout the policy cycle and in the design and delivery of public services. Rather than replacing formal rules and principles of a representative democracy – such as free and fair elections, representative assemblies and accountable executives – citizen and stakeholder participation aims to renew and deepen the relationship between governments and the public they serve. This includes, among others, meaningful youth participation in public decision-making and spaces for intergenerational dialogue at all levels (OECD, 2022[1]).

The importance of citizen and stakeholder participation for Adherents’ open government agendas is reflected in the fact that “participation” is one of the key terms used by Adherents in their official definition of open government (see also Box 1.2). In addition, the 2021 OECD Perception Survey on Open Government shows that Adherents consider citizen and stakeholder participation as the most important indication of a government’s level of openness, as four out of the five highest ranked answers fall under the principle of participation (OECD, 2021[2]).

Box 9.1. The three levels of stakeholder participation

The OECD Recommendation on Open Government classifies participation under three levels, which differ according to the level of involvement and the impact that stakeholders can have in the final decision. Stakeholder participation is understood through a ladder of participation which includes the following stages:

Information: an initial level of participation characterised by a one-way relationship in which the government produces and delivers information to stakeholders. It covers both on-demand provision of information and “proactive” measures by the government to disseminate information.

Consultation: a more advanced level of participation that entails a two-way relationship in which stakeholders provide feedback to the government and vice-versa. It is based on the prior definition of the issue for which views are being sought and requires the provision of relevant information, in addition to feedback on the outcomes of the process.

Engagement: when stakeholders are given the opportunity and the necessary resources (e.g., information, data and digital tools) to collaborate during all phases of the policy-cycle and in the service design and delivery.

Source: (OECD, 2017[3]).

8.1: Putting participation at the core of open government agendas, to provide diverse opportunities for both citizens and stakeholders in all phases of the policy-cycle and service design and delivery

While the concept of citizen and stakeholder participation is at the heart of Open Government and of most OGP initiatives, the results of the OECD Open Government Reviews and Scans show that the wider participation agenda has not always been considered an integral part of Adherents’ open government agendas which were initially often focused on issues relating to open government data and/or the fight against corruption (see above). Notably, the participation and open government files are often placed under the responsibility of different public institutions and are not being coordinated as an integrated policy agenda. This was initially the case for Adherents such as Brazil, Canada, Colombia and Romania.

In addition, in many cases, Adherents do not link high-level participatory processes with the broader open government effort in the country. For example, the OECD (OECD, 2020[4]) gathered numerous case studies of the use of representative deliberative processes across Adherents and found that few of these experiences emerged from/are integrated in Adherents’ wider open government agendas. This often also applies to non-deliberative processes, with key national participatory processes such as the Grand Débat in France or the Conversación Nacional in Colombia that were not coordinated as part of the open government agenda.

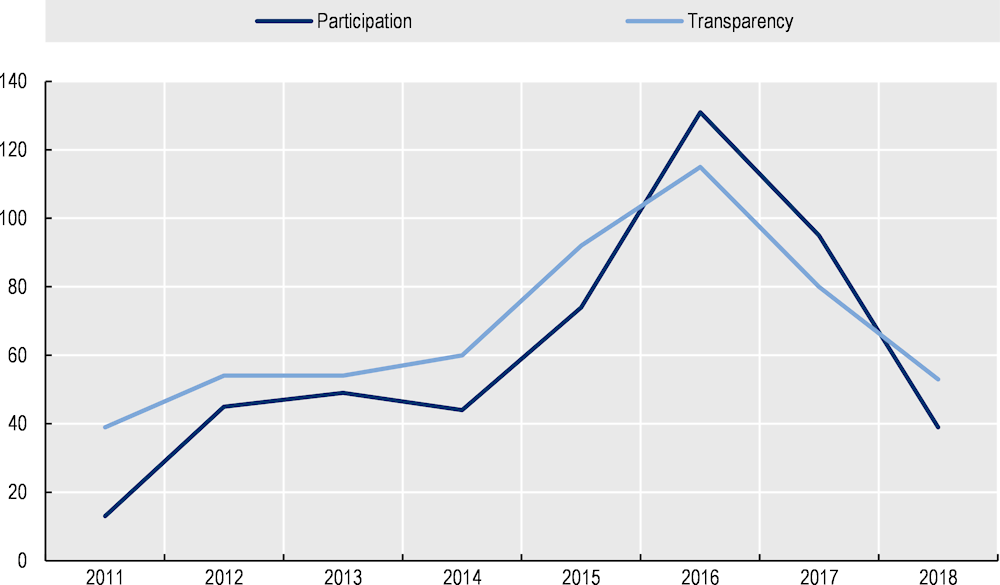

However, an analysis of commitments included in Adherents’ OGP Action Plans reveals that the number of commitments on citizen and stakeholder participation included in them has progressively increased. Transparency has always been at the core of Adherents’ open government agendas, however, evidence suggests a shift towards a stronger participatory focus in recent years as also a rise in the number of initiatives that promote youth’s involvement in the policy cycle shows. For instance, Spain’s 2017-2019 Open Government Action Plan included a commitment for the Spanish Youth Institute INJUVE to promote the effective participation of young people in democratic life and in the creation of youth policies through the national implementation of the EU Structured Dialogue (OECD, 2020[5]).

Figure 9.1. Transparency and Participation commitments in Adherent’s OGP Plans

Note: Transparency includes commitments tagged as “open data” and “right to information”. Participation includes commitments tagged as “public participation” and “e-Petitions”.

Source: OGP (2022[6]).

There are opportunities to further integrate the open government and participatory agendas. For example, some Adherents have recently mandated the same public institutions with both agendas to increase coordination and synergies and treat them as the same agenda. This is the case, for example, in France. Moving forward, for Adherents that are part of the OGP, the co-creation process and the multi-stakeholder forum (MSF) could be used strategically as pillars of an open government agenda that fully integrates participation activities. On one hand, the OGP co-creation process is usually a stable and regular space for stakeholders to participate in public policy. This type of participatory practices could be enlarged to other policy areas beyond the OGP-process and be part of a country’s participatory toolbox. Furthermore, the MSF usually gathers stakeholders that are familiar with the wider participation agenda, whether from civil society or academia, and it could be used as a platform to promote participation beyond the OGP and the Action Plans.

Increasing the diversity of participatory processes and practices.

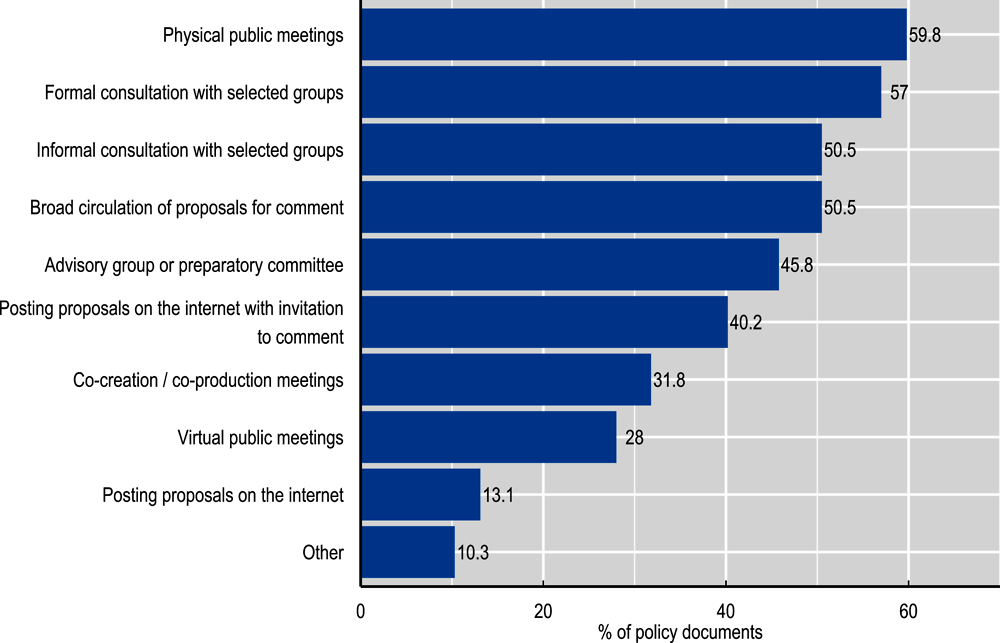

Citizens today are more informed than ever and are demanding a say in shaping the policies and services that affect their lives. In response, public institutions at all levels of government are increasingly creating opportunities to harness citizens’ experiences and knowledge to make better public decisions (OECD, 2020[4]). Evidence collected through the OECD Open Government Reviews and Scans and the OECD Database of Representative Deliberative Processes and Institutions (2021[7]) shows that the global landscape for citizen and stakeholder participation is evolving constantly, becoming richer with new and innovative ways to involve citizens and stakeholders in public decisions. Adherents are now implementing a diverse set of participatory mechanisms to involve citizens and stakeholders in public decisions: from more traditional mechanisms such as public meetings, in-person consultations, roundtables and workshops, to more innovative approaches like digital platforms and, recently, representative deliberative processes (Figure 9.2). This contributes, among others, to ensure age diversity in stakeholder participation through in-person as well as digital means, with methods tailored to different groups’ availability, needs and interests (OECD, 2022[1]).

Figure 9.2. Channels used to involve non-public stakeholders in developing the main policy documents on open government in Adherents

Note: N=37 for 107 policy documents. Multiple selection possible.

Source: OECD (2020[8]), 2020 Survey on Open Government.

When developing their main policy documents on open government, in 60% of the cases Respondents use in-person public meetings to provide information to stakeholders. However, the most common way to involve stakeholders is through consultations, namely:

Formal consultations with selected groups in 57% of Respondents (61) of the policy documents submitted.

Informal consultation with selected groups in 50.5% of Respondents (54) of the cases.

Advisory group or preparatory committees for 45.8% of Respondents (49) of the submitted documents.

Public consultation conducted over the internet with invitation to comment on 40.2% of Respondents (43) of the cases.

The quality and impact of participatory processes vary widely among Adherents.

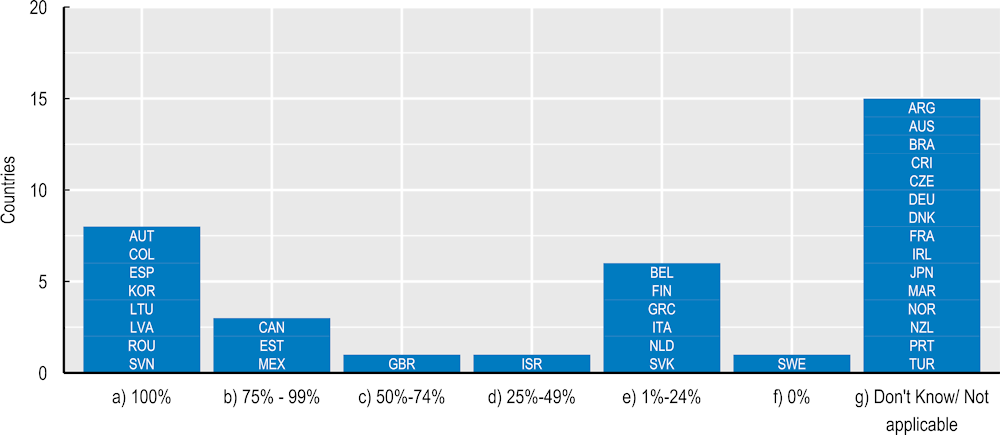

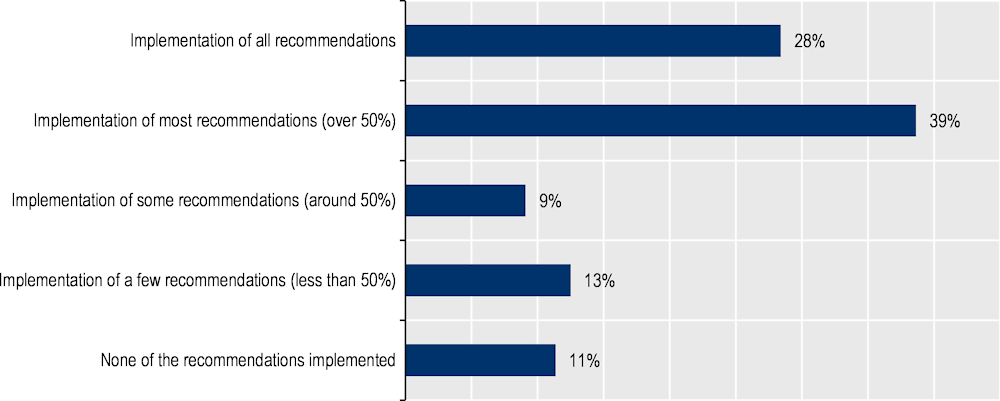

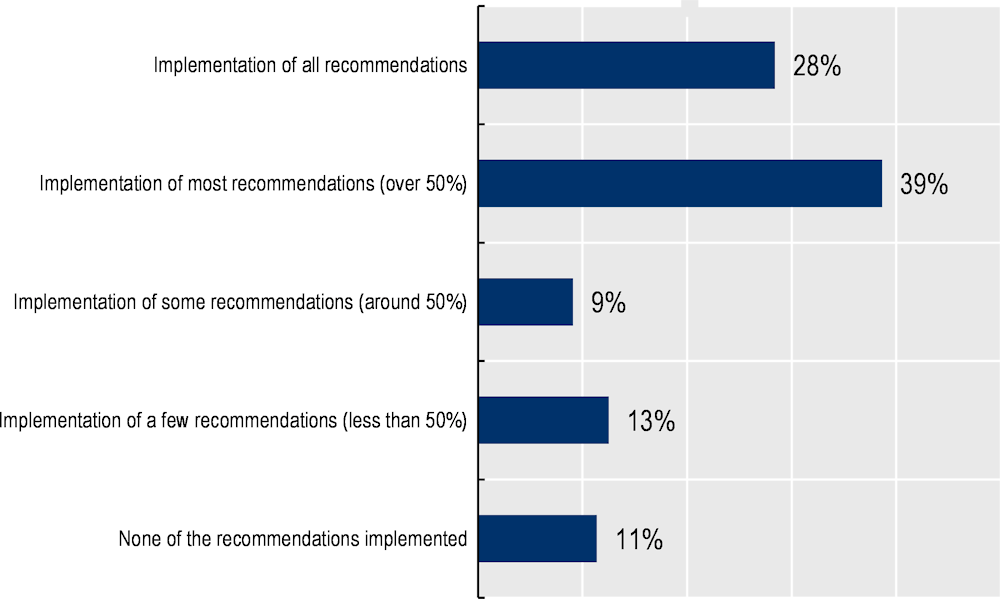

The quality of a participatory process is of great importance to ensure impact and citizen satisfaction (OECD, 2022[9]). However, evidence collected through the OECD Open Government Reviews and Scans shows that “closing the feedback loop” (i.e., efforts taken by the conveners of a participatory process to get back to participants about the status of their inputs and the ultimate outcome of their participation) is not yet common practice among Adherents. By not properly closing the feedback loop, public institutions risk discouraging people from participating another time and potentially diminish the benefits of participation. A notable exception are representative deliberative processes. Data collected by the OECD regarding the implementation of recommendations issued from these processes shows that, in around two-thirds of cases, at least half of the participants’ recommendations were implemented (Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3. Implementation of recommendations produced during representative deliberative processes for public decision making in Adherents, 1979-2021

Note: N=88. Data is based on 16 Adherents’ responses (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Estonia, France, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, UK and USA) plus the European Union, from 1997-2021.

Source: OECD (2021[7]), Database of Representative Deliberative Processes and Institutions.

To increase the quality of participation, Adherents are increasingly investing in internal capacities and skills to ensure civil servants are trained to involve citizens and stakeholders. Almost 80% of Respondents already have toolkits and guidelines for civil servants regarding citizen and stakeholder participation, and almost 64% of them also offer trainings on the subject (OECD, 2020[8]). Nevertheless, there is a need to make further efforts to gather higher quality comparative information regarding the quality and impact of participatory processes. To support this, the OECD recently published the OECD Guidelines on Citizen Participation Processes which could provide an opportunity for further data collection and policy analysis.

Box 9.2. Case studies: Representative deliberative processes

The Irish Citizens’ Assembly 2016-2018 (Ireland)

The Irish Citizens’ Assembly involved 100 randomly selected citizen members who considered five important legal and policy issues: the 8th amendment of the constitution on abortion, ageing populations, referendum processes, fixed-term parliaments and climate change. The Assembly’s recommendations were submitted to parliament for further debate. Based on its recommendations, the government called a referendum on amending the 8th amendment and declared a climate emergency. More information can be found here: https://www.citizensassembly.ie/en/

Citizens' Jury on the Construction of Gwangju Metropolitan Subway 2018 (South Korea)

The city of Gwangju in South Korea convened a Citizens’ Jury to deliberate on the construction of line 2 of their metropolitan subway system. The city council decided to go down that route after 16 years of internal conflict and political gridlock. 250 randomly selected citizens participated in an overnight public deliberation, along with other stakeholders. They recommended that the city should go ahead with the construction of the line but making sure to implement other measures to prevent wasted resources and address other concerns.

More information can be found here: https://en.kadr.or.kr/blank-4

Participatory processes can involve both common citizens and organised groups of stakeholders.

The Recommendation refers to stakeholders, as “any interested and/or affected party, including individuals, regardless of their age, gender, sexual orientation, religious and political affiliations, and institutions and organisations, whether governmental or non-governmental, from civil society, academia, the media or the private sector”. It is thus understood that stakeholders include citizens, as well as governmental and non-governmental organisations. The line between organised stakeholders and citizens can be blurry and, in reality, is not always perfectly neat. No value or preference is given to citizens or stakeholders in particular, as both groups can enrich public decisions, projects, policies, and services.

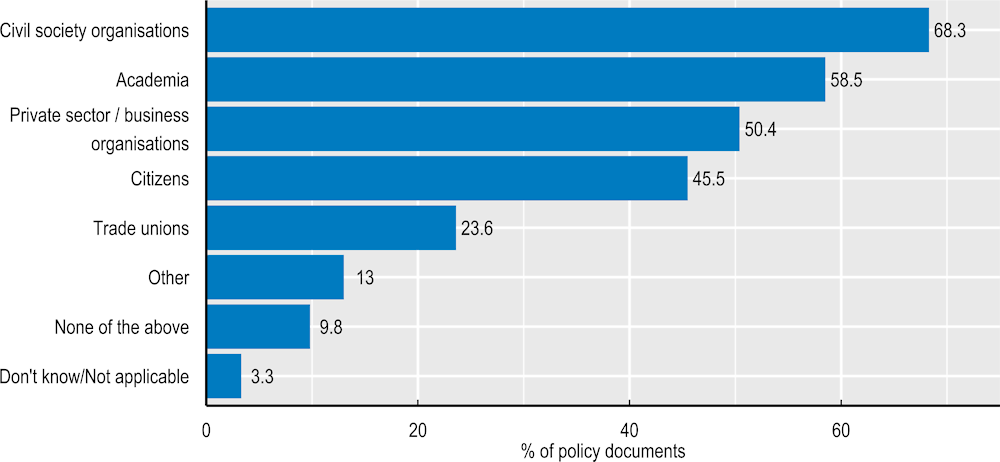

Data and evidence collected by the OECD shows that Adherents involve organised groups of stakeholders more regularly than individual citizen. As shown in Figure 9.4, Respondents involve civil society organisations in 68.3% of the main policy documents on open government submitted in response to the OECD Survey on Open Government, followed by stakeholders from academia and the private sector. In contrast, citizens were only consulted in the design of 45.5% of the policy documents. In addition, through the OECD Open Government Reviews and Scans, the OECD gathered evidence from Adherents such as Canada, Colombia, Argentina, Brazil and Romania showing a more recurrent involvement of organised stakeholders such as CSOs than individual citizens in public decisions, most notably at the national level (OECD, 2022[10]).

Figure 9.4. Types of non-public stakeholders consulted and/or engaged in the design of the policy document(s)

Note: N=38 for 123 policy documents. Multiple selection possible.

Source: OECD (2020[8]), 2020 Survey on Open Government.

Nevertheless, there is a global trend of increased involvement of individual citizens in policy making as seen through the waves of participatory budgeting or the use of representative deliberative processes. In recent years, Adherents have started showing a stronger interest in the constructive involvement of citizens (as individuals) at the central/federal level. Evidence collected through the OECD Database of Representative Deliberative Processes and Institutions (2021[7]) points to an increased use of representative deliberative processes2 with 21 cases organised in OECD Members in 2015, 32 in 2017, and 41 in 2019. For example, France, Spain, Germany and the United Kingdom have recently organised participatory processes for citizens to shape key policies like environment, health and immigration. The inclusion of individual citizens represents different challenges, especially regarding representativeness and inclusion.

Moving forward, Adherents could pay further attention to not treating organised stakeholders and citizens as equally and interchangeably, as they do not require the same conditions to participate and will not produce the same types of inputs (OECD, 2022[9]). Stakeholders can provide expertise and more specific input than citizens through mechanisms such as advisory bodies or experts’ panels, whereas citizens require methods that provide sufficient time, information and resources to produce quality inputs and develop individual or collective recommendations.

Box 9.3. Good practice cases: Citizen and stakeholder participation at the central/federal level in Brazil and Canada

Brazil – Multilevel participation on key policy areas

Beyond the famous case of Porto Alegre’s participatory budget, Brazil has coined other innovative mechanisms, notably the colegiados (Public Policy Councils and the National Conferences), which allow for large-scale stakeholder deliberation. Non-governmental stakeholders can inform policy making and provide recommendations on key areas including health, environment and education.

National Conferences: Periodic instance of debate, formulation and evaluation on specific themes of public interest, with the participation of government and non-public stakeholders. A conference can include stages at the State, District, Municipal or Regional level, to propose guidelines and actions on a specific topic.

Public Policy Councils: Permanent thematic collegial bodies, created by a normative act, to foster dialogue between non-public stakeholders and the government and promote participation in the decision-making process and in the policy cycle.

Canada – Stakeholder consultations

Canada has been consulting stakeholders at the Federal level for a certain time and on a wide range of policy areas. For example, the Department of Finance regularly consult stakeholders on budget priorities through the Let’s Talk Budget project. The Federal Government involved experts from the health sector to shape COVID-19 related policies through different mechanisms such as the National Advisory Committee on Immunization and the COVID-19 Clinical Pharmacology Task Group. Canada has taken efforts to increase inclusion, especially towards indigenous communities through the First Nations Consultations.

Source: (OECD, 2022[10]); OECD (2023[11]).

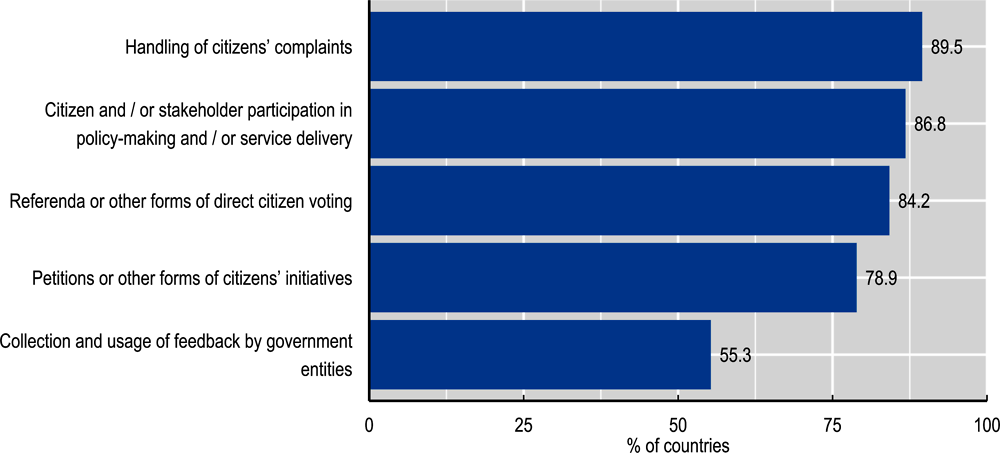

8.2: Institutionalise participatory processes and practices

A strong enabling environment can give participatory mechanisms and processes a high degree of institutionalisation and embed these practices in the institutional architecture of a country (OECD, 2021[12]). Almost all Adherents have adopted a legal framework in support of citizen and stakeholder participation, as 89.5% (34) of Respondents have adopted a legislation to handle citizen’s complaints, 84.2% (32) on the use of direct democracy mechanisms and 78.9% (30) on petitions and other forms of citizen initiatives (Figure 9.5). This is a positive finding, as a legal framework can support the institutionalisation of participation. However, there are opportunities to harmonize such frameworks as evidence collected by the OECD shows that these laws are usually fragmented and only addressing a partial aspect of participation.

Figure 9.5. Legislations to support citizen and stakeholder participation in Adherents

In addition, a majority of Adherents (86.7% of Respondents) have adopted specific policy documents to foster citizen and stakeholder participation (SOG) and many Adherents that are part of the OGP have used policy documents such as the OGP Action Plan to reinforce their enabling environment for participation (e.g., the Citizen Participation Councils and Legislation in Chile), develop trainings on participatory practices for public officials (e.g., Open Government Education in Spain) or create new digital participation platforms (e.g., Participa.br, the digital platform for participation in Brazil).

Adherents can further support institutionalisation by providing an office with a clear mandate to steer and coordinate the agenda across the whole government. Currently, the participation file has no clear institutional leadership at the level of the central/federal government of most Adherents. Rather, participatory practices are often implemented on an ad hoc basis by public institutions. Data collected through the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government shows that most Adherents have institutions that are in charge of issues that are related to participation, but responsibilities are usually scattered and multiple institutions have (sometimes conflicting) tasks. Notably:

83.8% (31) of Respondents have an office to strengthen relationships between government and civil society.

81.1% (30) of Respondents have an office to provide support to public institutions on how to consult and engage with citizens and stakeholders (guidance, advice, training, etc.).

67.6% (25) of Respondents have an office to provide technical support to public institutions on the use of digital technologies for citizen and stakeholder consultation or engagement.

Moreover, only 22.9% (eight) of Respondents currently have dedicated staff in charge of participation in all the ministries at the central/federal level.

Figure 9.6. Existence of dedicated staff in charge of citizen and stakeholder participation in Adherent’s ministries at central/federal level

Given the experience that Adherents’ Open Government Offices have gathered through the co-ordination of the OGP co-creation process and through the inclusion of relevant initiative in the OGP Action Plans (see the analysis of provision 3 above), Adherents that are part of the OGP could consider making them also the co-ordinators of the central/federal government’s citizen participation/engagement policy, as an integral part of the wider open government agenda.

Finally, citizen and stakeholder participation can also be institutionalised through practice and culture. Online government portals, such as the ones created by Brazil and Estonia, provide a centralised online architecture that can foster the move towards a culture of participation by increasing harmonisation of participatory practices, and by creating a habit among public servants and stakeholders alike.

8.3: Ensure inclusion and accessibility of participatory processes

Stakeholder participation can make decision making more inclusive by opening the door to more representative groups of people. Through participatory processes, public authorities can include the voice of the "silent majority" and strengthen the representation of minorities and often excluded groups like informal workers, migrants, women., indigenous populations and LGBTI communities. (OECD, 2022[9]). Stakeholder participation in public decision making can further answer the concerns of minorities and unrepresented groups by addressing inequalities of voice and access, and thus fight exclusion and marginalisation. However, for participatory practices to foster inclusion, public authorities have to take the necessary actions to reach out and involve those traditionally marginalised groups as well as take into consideration any special needs and verify that individuals with disabilities are able to exercise their right to participate in comfort (OECD, 2022[9]).

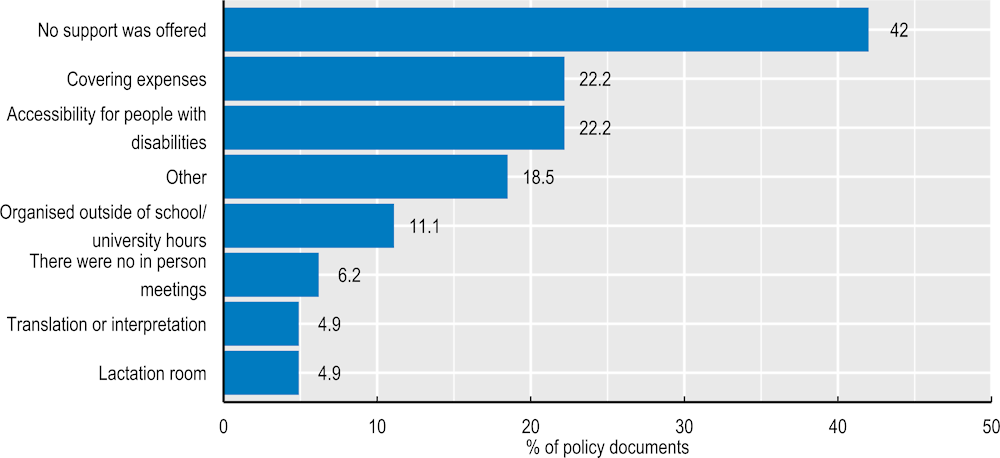

Data collected through the 2020 OECD Survey on Open Government shows that there is room for further efforts to increase the representation of the “silent majority” in the design and implementation of Adherents’ open government agendas. For example, in 42% (34) of the cases, Respondents did not provide any specific support for people to attend in-person meetings when designing their main policy documents on open government (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7. Support offered for non-public stakeholders to attend in-person meetings during the design of the main policy documents on open government

Note: N=31 for 81 policy documents. Multiple selection possible.

Source: OECD (2020[8]), 2020 Survey on Open Government.

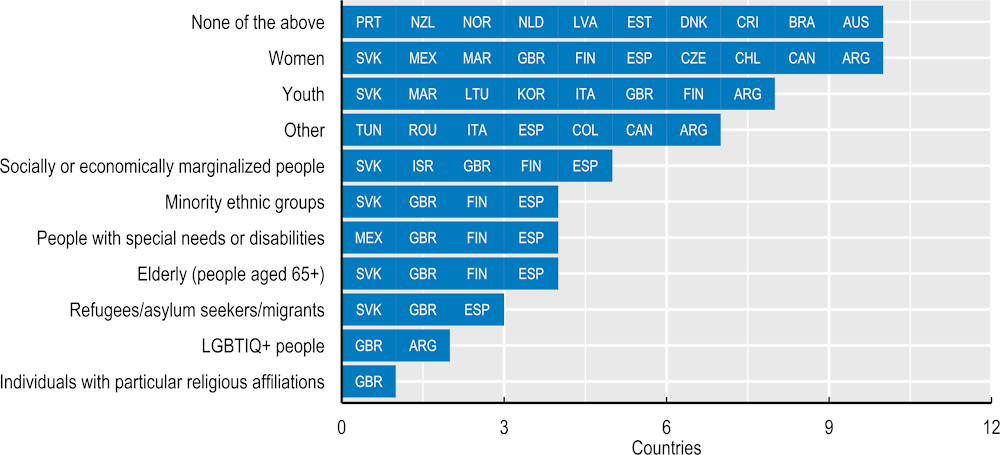

Similarly, 37% (ten) of Respondents that are part of the OGP do not include any representation of underrepresented groups in their OGP multi-stakeholder forum (MSF). 37% (ten) of Respondents that are part of the OGP make efforts to involve women in their MSF, while 29.6% (eight) of Respondents ensure a youth representation. Only 7.4% of Respondents that are part of the OGP are involving the LGBTI community in their MSF.

Figure 9.8. Inclusion and representation in Adherents’ OGP multi-stakeholder forum (MSF)

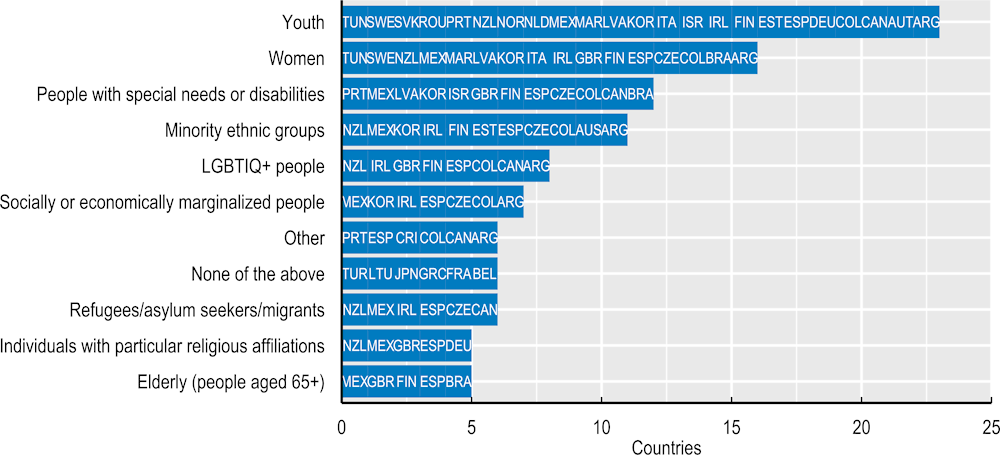

Nevertheless, data collected by the OECD suggest that Adherents are gradually increasing their efforts to increase inclusion. Almost all Adherents have strategies in place to ensure the participation of underrepresented groups in policy process. In particular, 67.6% (23) of Respondents have a strategy or policy to specifically foster the inclusion of youth in participatory processes, 47.1% (16) to increase women participation, 35.3% (12) for people with disabilities and 23.5% (eight) for LGBTI communities (Figure 9.9).

Figure 9.9. Availability of specific strategy/policy to encourage the participation of underrepresented groups in decision making

To foster inclusiveness, mitigate low participation turnout and broaden the scope of participants beyond “the usual suspects” (OECD, 2020[4]) governments can also remunerate participants for their participation. Research shows that more affluent citizens tend to participate more frequently in government-initiated processes (OECD, 2022[13]). Participation requires time and effort, especially of unorganised citizens, who, unlike stakeholders and interest groups, have a lower threshold for participation (OECD, 2022[9]). Evidence gathered by the OECD suggests that when more advanced levels of citizen engagement are pursued, such as representative deliberative processes, they tend to be accompanied with more substantive efforts ensuring inclusion of all members of society. For instance, in 238 out of 325 representative deliberative processes for which data is available, Adherents’ governments gave some form of compensation to participants – be it remuneration, transport compensation or coverage of expenses, as shown in Figure 9.10.

Figure 9.10. Remuneration of participants in representative deliberative processes in Adherent countries

Note: N=325.Data is based on 23 Adherent countries plus the European Union.

Source: OECD Database of Representative Deliberative Processes and Institutions (2021).

Box 9.4. The OECD Citizen Participation Guidelines

The OECD Citizen Participation Guidelines (2022) are intended to support the implementation of provisions 8 and 9 of the OECD Recommendation on Open Government. They are aimed at any individual or organisation interested in designing, planning and implementing a citizen participation process. The guidelines walk the reader through ten steps to design, plan and implement a citizen participation process, and detail eight different methods that can be used to involve citizens in policy making, illustrated with good practice examples.

The eight participation methods described are:

Open Meeting and Town Hall Meeting

Public Consultation

Open innovation methods: Crowdsourcing, Hackathons, and Public Challenges

Civic Monitoring

Participatory Budgeting

Representative Deliberative Process

Their content is based on evidence collected by the OECD over the years and various OECD publications, as well as existing resources from academia and other organisations regarding the intrinsic and instrumental benefits of citizen participation in policy making.

As part of the document, the OECD suggests eight guiding principles that help ensure the quality of these participatory processes: purpose, accountability, transparency, inclusiveness and accessibility, integrity, privacy, information, and evaluation.

Source: OECD (2022[9]), Guidelines for Citizen Participation Processes.

Protected civic space can increase inclusion in participatory processes.

Protected civic space can help to increase inclusion in participatory processes as it encourages stakeholders to organise and inform themselves and facilitates inclusion in public debate. Research indicates that while the legal foundations for civic space protection are relatively strong in OECD Members, with some exceptions, challenges remain.

Overall, data shows that freedom of expression could be better protected, for example. Article 19’s freedom of expression rankings for the 41 Adherents for which data is available, demonstrate that 78% of those Adherents rank as “open”, meaning it is possible for citizens to access information and distribute it freely, share their views both on and offline and protest in order to hold their governments to account (Article 19, 2021[14]). Four countries (10% Respondents) are ranked “less restricted”, three countries (7% of Respondents) as “restricted”, one country as “highly restricted” (2% of Respondents) and one country (2% of Respondents) is considered to be “in crisis”. Data also shows a significant decline in some Adherents since 2013 in press freedom and rising vilification of journalists and targeted violence and killings reported in some countries (OECD, 2022[15]). A number of countries have passed special measures to enhance protection for journalists.

Press freedom organisations and monitoring bodies have indicated that criminal defamation cases continue to be brought against journalists and human rights defenders in retaliation for unwanted investigations or commentary (Freedom House, 2021[16]; OSCE, 2017[17]; Council of Europe, 2022[18]). Research suggests that occasional convictions for defamation continue to take place in countries, including those considered to be strong defenders of media freedom such as Greece (OSCE, 2017[17]) and Italy (Borghi, R., 2019[19]). Some countries are experiencing particular challenges in relation to protecting journalists in contexts where they engage in investigations on issues related to organised crime and social conflicts (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2021[20]; UNESCO, 2021[21]).

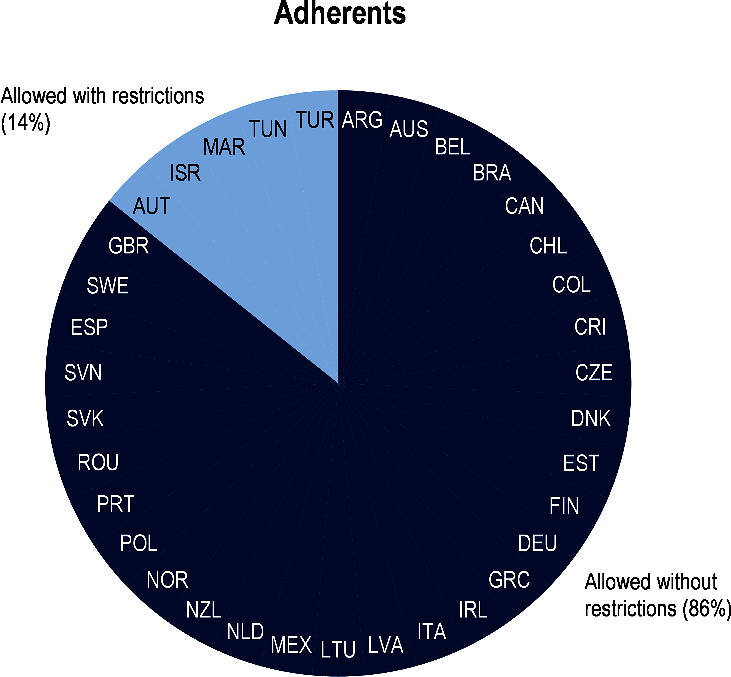

As regards freedom of peaceful assembly in Adherents, data from the Varieties of Democracy Institute shows that in 62% of Adherents, state authorities almost always allow and actively protect peaceful assemblies, except in rare cases of lawful, necessary and proportionate limitations. 26% of countries mostly allow peaceful assemblies, 9% sometimes arbitrarily deny citizens the right to assemble peacefully and 2% of countries rarely allow peaceful assemblies (OECD, 2022[15]).

Box 9.5. Laws, policies and programmes for the physical protection of journalists

A number of Adherents have passed special measures enhancing the rights of journalists, providing them with additional support when conducting their work or protecting them against threats of violence or intimidation. Aside from supporting press freedom as a crucial pillar of democracies, this can help to ensure that stakeholders have access to sufficient information to engage in public debate.

The human rights defenders protection law in Mexico explicitly applies to journalists, while Colombia has passed additional legislation and policies to protect journalists and social communicators (Government of Colombia, 2000[22]). Mexico has a special prosecutor’s office that investigates crimes against journalists (UNESCO, 2021[23]), and in Portugal, murder is met with aggravated sanctions if committed against a journalist.

In response to the rising levels of threat to journalists, several countries have also started to develop specific policies to protect them. The United Kingdom, for example, has a national action plan to protect journalists from abuse and harassment, including measures for training police officers and journalists, while social media platforms and prosecution services have committed to taking prompt and tough action against abusers (Government of the United Kingdom, 2021[24]).

In Brazil, since 2018, the federal human rights protection programme of the Ministry of Human Rights has also explicitly protected “communicators”, defined as persons performing regular social communication activities to disseminate information aimed at promoting and defending human rights (Government of Brazil, 2018[25]).

Source: Government of Colombia (2000[22]); Government of Brazil (2018[25]); UNESCO (2021[23]); Government of the UK (2021[24]).

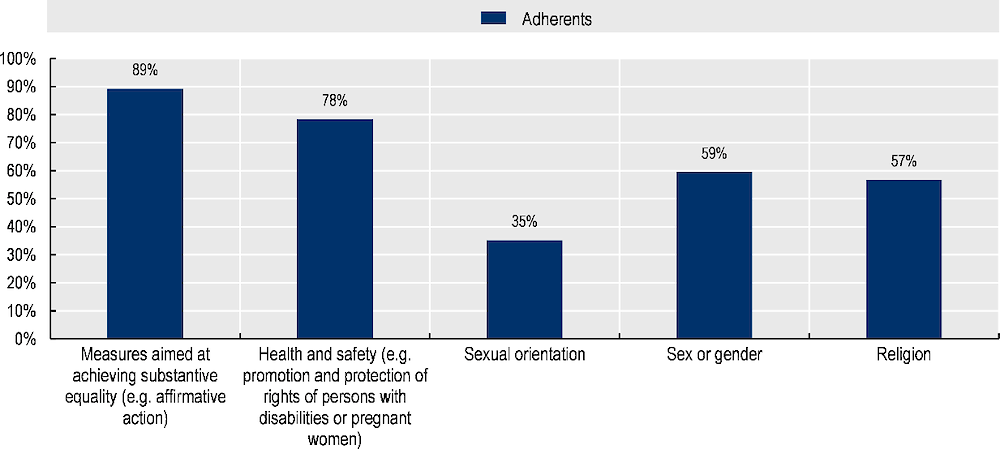

Anti-discrimination laws are central to facilitating citizen and stakeholder participation.

The broad legal environment on non-discrimination is an essential precondition for inclusive, responsive and effective democratic participation. Discrimination can affect citizens’ trust, in addition to their ability and willingness to engage with state institutions if they feel undervalued, excluded, unprotected or threatened. As such, all forms of discrimination can affect individuals’ and CSOs’ ability and willingness to freely express themselves or to assemble and influence public decision-making. Adherents’ discrimination laws (found in all Adherents) are thus central to protecting civic space for all members of society.

Figure 9.11. Legally mandated exceptions to protection against discrimination, 2020

Note: N=37. Percentage relates to countries that provided data on this topic in the OECD Survey on Open Government.

Source: OECD (2022[15]).

Survey data shows that laws in 89% of Respondents state in their constitutional and/or anti-discrimination legislation that measures aiming to achieve substantive equality or protection (e.g. affirmative action) for disadvantaged groups will not be considered discrimination (Figure 9.11). Furthermore, 35% of Respondents foresee affirmative action for persons based on their sexual orientation and do not consider this kind of distinction to be discrimination. For example, Belgium includes a number of protected characteristics in its national legislation, including sexual orientation. Similarly, in Canada, the law permits measures aimed at the promotion and protection of the rights of vulnerable or marginalised groups, where this is, among others, because of their sexual orientation or gender. In Chile, legislation allows distinctions, exclusions or restrictions based on protected grounds including sexual orientation that are reasonable, and states that these shall be considered justifiable in the legitimate exercise of another fundamental right, in particular private life, religion or belief, education, freedom of expression, freedom of association, right to work or economic development.

Overall, there is a trend towards making anti-discrimination legislation more comprehensive and in recognising different groups that are affected. In recent years, many EU member states have rendered their laws more comprehensive in the field of ethnic or racial discrimination (European Commission, 2019[26]). Ireland formally recognised “Travellers” as an ethnic group in 2017, for example, meaning that they are covered under that ground, as well as under the separate ground of being part of the traveller community, under relevant anti-discrimination legislation. Likewise, some legislative improvements in EU countries aim to enhance equal treatment of persons with disabilities, with laws and high court decisions attesting to a wide interpretation of the definition of disability (European Commission, 2019[26]).

Monitoring and data collection on discrimination are central to making participatory processes more inclusive.

The collection of data on hate speech (and related hate crimes) can be an important indicator of existing patterns of discrimination. However, in many Adherents’ countries, the actual extent of discrimination, hate crime and hate speech remains uncertain as comprehensive data is lacking. Data collection systems that fully disaggregate data by category of offence, type of hate motivation, target group as well as judicial follow-up and outcomes are important tools to reach out to marginalised groups when undertaking outreach activities for participatory processes. Some countries, such as Denmark, publish an analysis of trends on hate crime and hate speech, disaggregating data by motivation and type of bias, and compare the data across years.

Funding for the CSO sector is a valuable lifeline that facilitates stakeholder participation.

A favourable financial environment for CSOs is a key pillar of an enabling environment for civil society and stakeholder participation in public decision making. International guidance has made access to funding resources, including foreign funding, a key component of the right to freedom of association. CSOs should be free to solicit and receive funding, including state funding and other forms of public support, such as exemption from income tax or other taxes and that any form of public support should be governed by clear and objective criteria (Kiai, 2013[27]; 2012[28]; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2011[29]; Council of Europe, 2007[30]). Additionally, NGOs could be free to receive different forms of assistance from non-public sources, as well as from foreign and multilateral agencies.

Comprehensive data on funding for CSOs is lacking in a significant number for Adherents, partly due to the fact that public resources for CSOs come from a wide range of sources, involving different ministries, budget lines and both local and regional governments. The absence of an overview in many countries, including those giving generously towards the CSO sector, makes it difficult to strengthen systems and monitor funding trends. By enhancing data collection on government funding provided to the CSO sector, including on funding coming from different ministries and state institutions, disaggregated by funding modalities, type of support and area of focus, governments can develop a more strategic approach to supporting civil society.

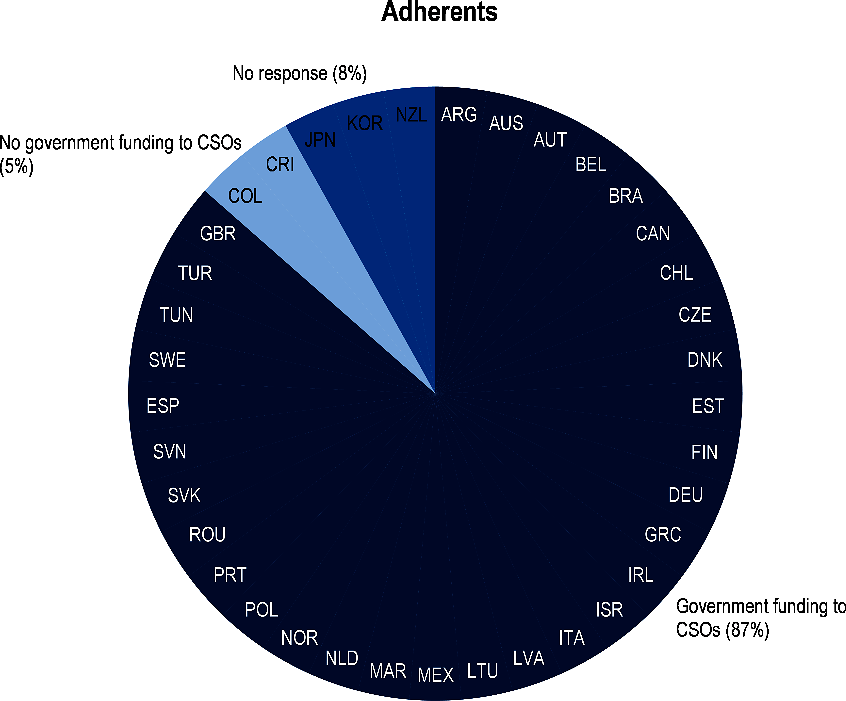

Figure 9.12. Adherents that provided government funding to CSOs in 2019

Note: N=37. Percentages relate to countries that provided data in the OECD Survey on Open Government.

Source: OECD (2022[15]).

There are many ways Adherents create a supportive environment for CSOs that facilitates their ability to access funding in a predictable, sustainable, transparent and fair manner. Figure 9.12 illustrates that 87% of Respondents provided some type of central/federal state funding to CSOs in 2019. In some countries, there are examples of core funding, which is a funding modality that is directed at supporting CSOs’ organisational expenses that cannot be allocated to specific projects, including administrative costs, infrastructure costs, institutional capacity building, board meetings, audit expenses and other recurring costs. Core funding is important for organisations’ successful operations and for increasing the capacity of the CSO sector (OSCE/ODIHR and Venice Commission, 2015[31]). For instance, in Finland, the Ministry of Education and Culture provides subsidies to CSOs (Government of Finland, n.d.[32]) that cover costs related to their operations and the construction of educational and cultural sites. Sweden provides investment grants and business development grants to CSOs and companies that establish public meeting rooms with the precondition that “in their activities, they respect the ideas of democracy, including the principles of gender equality and prohibition of discrimination” (Government of Sweden, 2016[33]). In Spain, organisations engaged in promoting equality, social inclusion, and poverty reduction can be awarded grants that can cover a wide range of running costs and capacity-building activities (Government of Spain, 2019[34]). The Ministry of Education in Estonia also provides funding to strategic partner organisations for a three-year period. This funding includes an operating grant aimed at building the organisation’s capacity to participate in policy-making processes (Government of Estonia, 2022[35]).

In countries where government funding is limited or unavailable and where there is a lack of private donations, foreign or international funding can also be a lifeline. Governments can thus contribute to an enabling environment for CSOs by incentivising foreign and international donors to support the sector. Figure 9.13 illustrates that laws governing freedom of association or other laws directly covering associations restrict foreign funding for CSOs in 14% of Respondents.3 The limitations provided for in relevant laws apply in different forms and include pre-conditions or the need for state authorisation to receiving foreign funding, in addition to administrative requirements and intensified monitoring and oversight. Reporting requirements can include disclosing the frequency and content of financial statements or information about donors and persons affiliated with the CSO and can be accompanied by sanctions for non-compliance. According to guidance from the United Nations, onerous or arbitrary reporting obligations for CSOs on funds from foreign sources, including on how these are allocated or used, and to obtain authorisation from state authorities to receive foreign funds can have a negative impact on the right to freedom of association (Kiai, 2013[27]).

Figure 9.13. Rules in laws governing CSOs on receiving funding from abroad, 2020

Note: N=35. Percentages relate to the countries that provided data in the OECD Survey on Open Government.

Source: OECD (2022[15]).

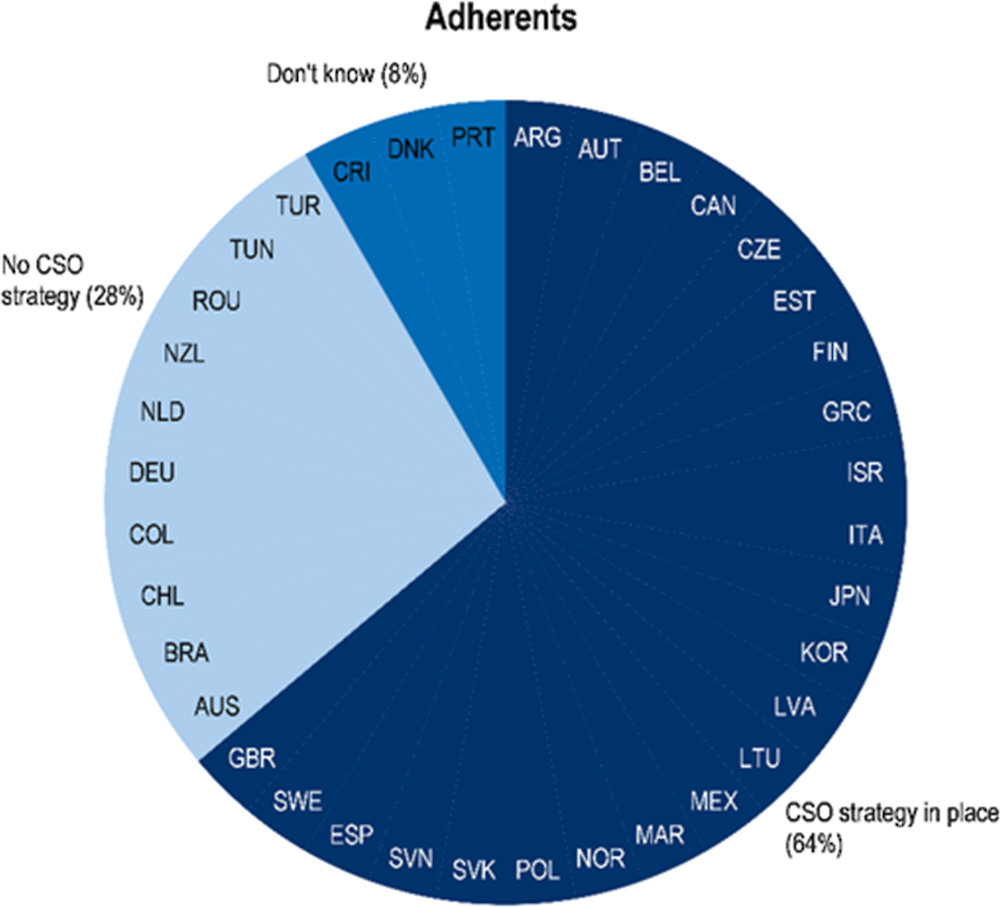

CSO strategies can strengthen government - CSO relations, thereby facilitating more effective participation in public life.

Many governments are making substantial efforts to support the CSO sector. However, some of these initiatives are undertaken through a scattered approach without clearly delineated objectives outlined in an overarching framework. A majority (64%) of Respondents have a policy or strategy in place to improve or promote an enabling environment for CSOs (OECD, 2020[8]). Government strategies to promote an enabling environment for CSOs can have multiple beneficial outcomes. First, they offer governments an opportunity to assess the current conditions that CSOs operate within, and second, they enable governments to set expectations and benchmarks for areas of improvement. In addition, such strategies allow governments to concretely outline mechanisms for bolstering the role of CSOs while taking their varying needs into account. A strategy can also highlight the difficulties that CSOs may be facing, particularly in the aftermath of global crises, such as COVID-19, and identify potential future risks.

Figure 9.14. Adherents with a policy or strategy to improve or promote an enabling environment for CSOs, 2020

Note: N=36. Percentage relates to countries that provided data in the OECD Survey on Open Government.

Source: OECD (2022[15]).

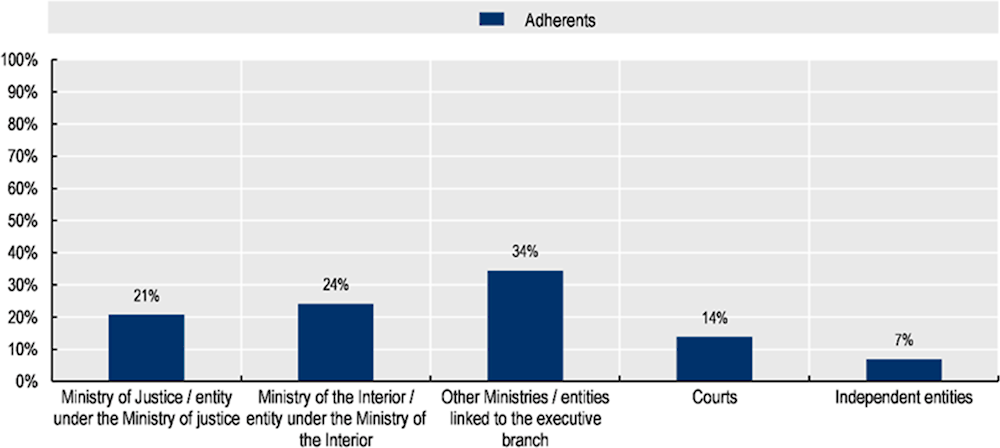

Entities responsible for CSO registration set the tone for healthy government - civil society relations.

Responsibility for registering CSOs is an important function and can send a powerful message about the sector as a whole. In 24% of Respondents (OECD, 2020[8]), Ministries of Interior are in charge of registration. In other countries, this function is performed by the Ministry of Justice (or an entity under the Ministry of Justice) (21%), the courts (14%) or other independent entities (7%). The main trend is for other ministries, such as Ministries of Culture or Labour and Social Affairs, or administrative entities at local level to fulfil this role (34%). Giving the registration responsibility to entities that are at the same time responsible for investigating crimes or protecting national security or public order, such as Ministries of Interior risks associating CSOs with security risks and threats to public order.

Figure 9.15. State entities responsible for the registration of CSOs

Note: N=29. Percentage relates to countries that provided data in the OECD Survey on Open Government.

Source: OECD (2022[15]).

Conclusions and way forward (provision 8)

The analysis shows that, overall, the implementation of provision 8 is progressing well, however further efforts could be made to ensure inclusion, quality and impact of participatory processes.

8.1: Adherents have been gradually increasing the integration of their participation agendas into their wider open government agendas, for example through OGP commitments. Moving forward, Adherents that design holistic Open Government Strategies could ensure that these strategies fully integrate their countries’ participation agendas. Furthermore, Adherents that are part of the OGP could include high-level participatory efforts (e.g., deliberative processes) into their action plans.

8.2: All Adherents are involving citizens and stakeholders at some point of their open government policy cycles. Most Adherents are informing stakeholders through public meetings, the vast majority is consulting stakeholders through different forms of public consultation and a smaller proportion is engaging stakeholders through mechanisms such as co-creation or deliberative processes. Moving forward, Adherents could make increasing efforts to bring participatory practices to all policy areas (e.g., education, health, finance, etc.) and put an emphasis on moving beyond consultation towards practices of citizen and stakeholder engagement.

8.3: Adherents currently involve organised groups of stakeholders such as experts more regularly in their open government agendas than individual citizens, reflecting that stakeholders can provide specific expertise and inputs than common citizens. Moving forward, and reflecting the increased demand from citizens to be part of public decisions, Adherents could make further efforts to involve individual citizens in public decision-making.

8.4: While almost all Adherents have adopted legislation and policies to support participation, evidence shows that this legislation is scattered. In addition, while all Adherents have offices in the central level with responsibilities regarding participation, very few of them have a mandate to steer the agenda across the entire government. Moving forward, Adherents could focus on consolidating their legal and policy frameworks governing participation as part of the wider open government agenda and empower a national office to become the leader and coordinator of a dedicated agenda to foster participation (e.g., the Open Government Office).

8.5: Efforts to include the voice of the "silent majority" and strengthen the representation of minorities and excluded groups are crucial for open government. Moving forward, Adherents could regularly review their legislation, policies and their effects, to assess and remedy violations of individuals' right to protection from discrimination and to ensure that implementation is in line with international guidance. Regular monitoring of discrimination targeting at-risk groups would also enhance understanding of trends and facilitate the development of evidence-based, resourced strategies to counter it. Adherents could further consider increasing the representation of underrepresented groups of society in their OGP-process, and in general, in all their participatory processes. Finally, Adherents can create a supportive enabling environment for civil society via dedicated strategies, facilitated funding and supportive practices for the sector, thereby facilitating more inclusive and effective participation.

References

[14] Article 19 (2021), The Global Expression Report 2021: The state of freedom of expression around the world, https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/A19-GxR-2021-FINAL.pdf.

[19] Borghi, R. (2019), Defamation lawsuits against journalists doubled in 5 years. Ossigeno: Intimidation Impunity rate is 96.7% [Querele per diffamazione contro giornalisti raddoppiate i 5 anni. Ossigeno: tasso impunità intimidazioni è 96,7%], https://www.primaonline.it/2019/10/26/296460/querele-per-diffamazione-contro-giornalisti-raddoppiate-i-5-anni-ossigeno-tasso-impunita-intimidazioni-e-967/.

[20] Committee to Protect Journalists (2021), Committee to Protect Journalists, https://cpj.org/data/killed/?status=Killed&motiveConfirmed%5B%5D=Confirmed&motiveUnconfirmed%5B%5D=Unconfirmed&type%5B%5D=Journalist&start_year=1992&end_year=2022&group_by=year.

[18] Council of Europe (2022), Annual Report by the partner organisations to the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and Safety of Journalists,, https://rm.coe.int/platform-protection-of-journalists-annual-report-2022/1680a64fe1.

[30] Council of Europe (2007), Recommendation CM/Rec(2007)14 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on the legal status of non-governmental organisations in Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/ingo/legal-standards-for-ngos.

[26] European Commission (2019), A Comparative Analysis of Non-discrimination Law in Europe 2019, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a88ed4a7-7879-11ea-a07e-01aa75ed71a1.

[16] Freedom House (2021), Freedom in the World 2021: Democracy under Siege, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2021/democracy-under-siege (accessed on 16 February 2022).

[25] Government of Brazil (2018), Ordinance Nº 300 of 3 September 2018, Ministry of Human Rights, https://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/39528373/do1-2018-09-04-portaria-n-300-de-3-de-setembro-de-2018-39528265.

[22] Government of Colombia (2000), Decree 1592 of 2000, https://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?id=1314526.

[35] Government of Estonia (2022), Ministry of Education, https://www.hm.ee/et/tegevused/rahastamine/strateegiliste-partnerite-rahastamine (accessed on 9 May 2022).

[32] Government of Finland (n.d.), Subsidies of the Ministry of Education and Culture, https://okm.fi/en/subsidies.

[34] Government of Spain (2019), Real Decreto 681/2019, https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2019-16869.

[33] Government of Sweden (2016), Ordinance (2016: 1367) on state subsidies for public meeting places, https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/forordning-20161367-om-statsbidrag-till_sfs-2016-1367.

[24] Government of the United Kingdom (2021), Government publishes first ever national action plan to protect journalist, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-publishes-first-ever-national-action-plan-to-protect-journalists.

[29] Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (2011), Second Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in the Americas, https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/defenders/docs/pdf/defenders2011.pdf.

[27] Kiai, M. (2013), Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G13/133/84/PDF/G1313384.pdf?OpenElement.

[28] Kiai, M. (2012), Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, https://www.ohchr.org/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/regularsession/session20/a-hrc-20-27_en.pdf (accessed on 2019).

[11] OECD (2023), Open Government Scan of Canada, Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1290a7ef-en.

[13] OECD (2022), “Engaging citizens in cohesion policy: DG REGIO and OECD pilot project final report”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 50, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/486e5a88-en.

[9] OECD (2022), Guidelines for Citizen Participation Processes, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/f765caf6-en.

[10] OECD (2022), Open Government Review of Brazil: Towards an Integrated Open Government Agenda, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3f9009d4-en.

[1] OECD (2022), Recommendation of the Council on Creating Better Opportunities for Young People, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0474.

[15] OECD (2022), The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: Strengthening Alignment with International Standards and Guidance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d234e975-en.

[12] OECD (2021), “Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 12, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/14e1c5e8-en-fr.

[7] OECD (2021), OECD Database of Representative Deliberative Processes and Institutions.

[2] OECD (2021), Perception Survey for Delegates of the OECD Working Party on Open Government.

[5] OECD (2020), Governance for Youth, Trust and Intergenerational Justice: Fit for All Generations?, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/c3e5cb8a-en.

[4] OECD (2020), Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/339306da-en.

[8] OECD (2020), OECD Survey on Open Government.

[3] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438 (accessed on 23 August 2021).

[6] OGP (2022), OGP Explorer, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/explorer/all-data.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

[17] OSCE (2017), Defamation and Insult Laws in the OSCE Region: A Comparative Study, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, https://www.osce.org/fom/303181.

[31] OSCE/ODIHR and Venice Commission (2015), Joint Guidelines on Freedom of Association, https://www.osce.org/odihr/132371.

[23] UNESCO (2021), Recent convictions highlight the work of Mexico’s Prosecutor Office dedicated to crimes against freedom of expression, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/recent-convictions-highlight-work-mexicos-prosecutor-office-dedicated-crimes-against-freedom#:~:text=UkraineWorld%20Heritage-,Recent%20convictions%20highlight%20the%20work%20of%20Mexico's%20Prosecutor%20Office,crimes%20a.

[21] UNESCO (2021), UNESCO observatory of killed journalists, https://en.unesco.org/themes/safety-journalists/observatory?field_journalists_date_killed_value%5Bmin%5D%5Byear%5D=2022&field_journalists_date_killed_value%5Bmax%5D%5Byear%5D=2022&field_journalists_gender_value_i18n=All&field_journalists_nationality_tid_i.

Notes

← 1. The Recommendation understands stakeholder participation as “all the ways in which stakeholders can be involved in the policy cycle and in service design and delivery”.

← 2. In such processes, randomly selected citizens form a microcosm of the community they aim to represent and deliberate to deliver recommendations on a specific policy challenge to public authorities.

← 3. While desk research indicates that many countries also restrict funding from abroad in anti-money laundering or anti-terrorism laws, these are not reflected in Figure 3.60.