This chapter provides an overview of recent foreign direct investment (FDI) trends in SADC, including a preliminary assessment of its contribution to sustainable development. It then summarises key messages and main considerations that emerge from the substantive chapters of the report.

Sustainable Investment Policy Perspectives in the Southern African Development Community

1. Overview

Abstract

Introduction

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is a large and dynamic regional economic community (REC) with the second highest level of regional integration among all African RECs. It has also been at the forefront of regional investment policy making in Africa, with the Finance and Investment Protocol and the Investment Policy Framework (building on the OECD Policy Framework for Investment), as well as the SADC Model Bilateral Investment Treaty. More recently, SADC Member States have worked to implement these frameworks at country level through the National Action Programmes for Investment. At the same time, like much of Africa, SADC faces difficulties in attracting foreign direct investment which can contribute to sustainable development in the region.

The recent African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) and its related Protocols will offer both greater investment opportunities for SADC Members within an integrated continental market as well as increased competition for footloose investment. This will imply an even greater need to focus on raising the competitiveness of the region for investment, and on how to improve sustainable outcomes from investment.

This report introduces newly developed OECD tools and analysis to the SADC region, including both FDI Qualities and a database on investment incentives. It is designed as a baseline diagnostic to explore ways to reinvigorate the reform of the SADC investment climate in order to prepare the region for the AfCFTA, while also providing a greater focus on how to improve sustainable outcomes from investment. The policy areas covered in this study include the national regulatory framework encapsulated in national investment laws and how this compares with initiatives at a regional level, investment promotion and facilitation in SADC, investment incentives, investment for green growth and, lastly, responsible business conduct.

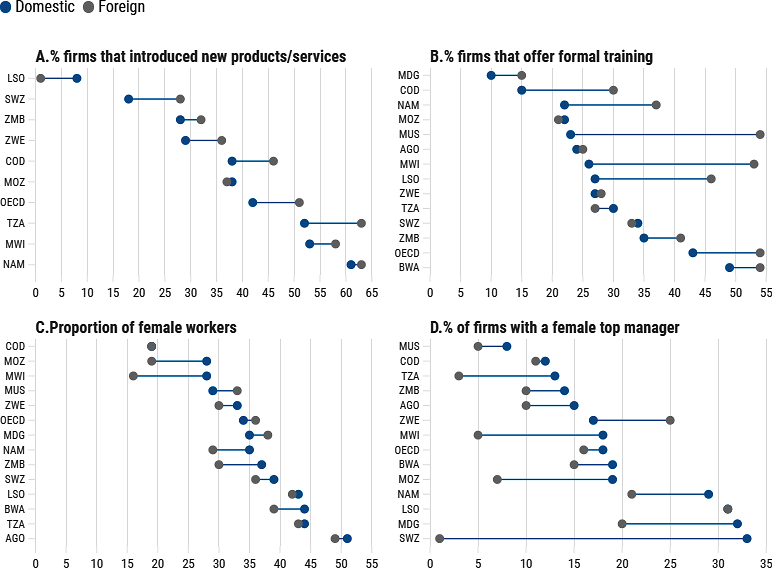

Recent trends in FDI in SADC and estimates of its impact

Foreign direct investment flows into the SADC region have been volatile over the last decade, exhibiting a considerable drop in 2015, and a spike in 2021 as a result of a large one‑off intra-firm financial transaction in South Africa (Figure 1.1). Within the region, inward FDI stocks are highest in South Africa (51%), the largest and most diversified economy, followed by other large SADC economies that are rich in natural resources like Mozambique (15%), DR Congo (9%), and Zambia (6%). Fluctuating flows into these large recipients, combined with divestment in Angola, drove the volatile FDI performance observed in recent years. The economic importance of FDI stock relative to GDP is high, averaging 70% across the region; yet there is considerable variation across countries, with FDI shares in GDP around 10% in Comoros and Malawi, and over 250% in Seychelles and Mozambique.

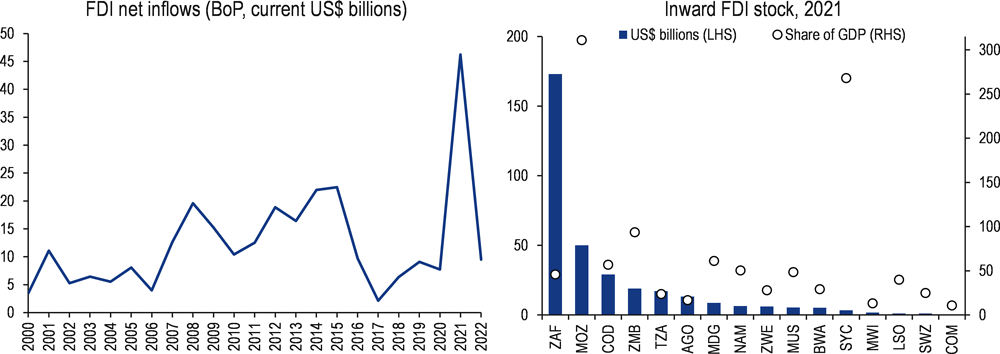

New FDI projects or expansions of existing FDI projects (i.e. greenfield FDI flows) have similarly exhibited considerable volatility over the last two decades, with the value of investments flowing into the region oscillating between USD 10 and 40 billion (Figure 1.2, Panel A). The COVID‑19 pandemic appeared to have a modest and transitory effect on FDI inflows into SADC, which were already low in 2019, and rose significantly above pre‑pandemic levels by 2022. While the value of greenfield investments exhibits a relatively constant trend, the volume of investments has declined over the last 15 years, suggesting that SADC attracts fewer but larger investments. Jobs created from these investment projects have also been on a declining trend since 2007, suggesting that FDI inflows have become relatively more capital-intensive. A closer look at the stock of greenfield investment projects by sector shows that the vast majority of these investment are in capital-intensive sectors like coal, oil and gas (29%), metals (17%), construction (11%) and renewable energy (10%). Indeed, extraction, manufacturing, and electricity generation in the energy and metals sectors accounts for 55% of the entire stock of greenfield FDI in the region.

Figure 1.1. FDI flows into SADC has been volatile

Note: The surge in inflows in 2021 is driven by one large inter-firm transaction in South Africa.

Source: OECD elaboration based on IMF (2022) Balance of Payments Statistics and UNCTAD (2023[1]).

Figure 1.2. Greenfield FDI projects have become increasingly large and capital intensive

Note: Data includes all open and announced projects between 2003 and 2022.

Source: OECD elaboration based on Financial Times fDi Markets (2023[2]).

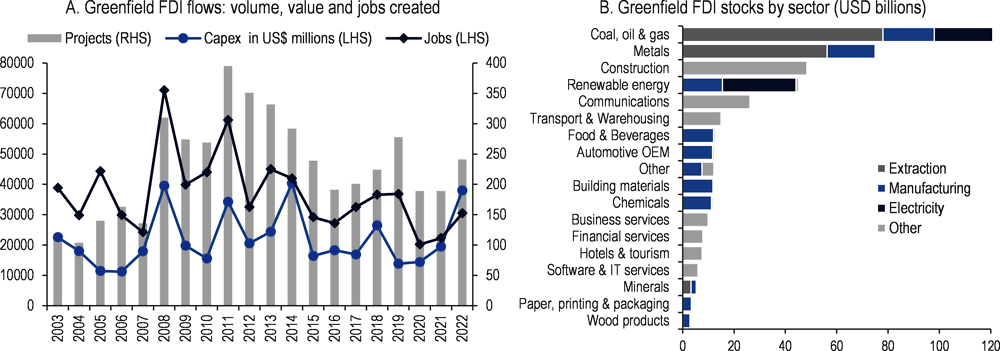

At the country-level, a similar pattern emerges (Figure 1.3). Greenfield FDI in SADC created 1.8 jobs per million USD invested, on average, well below the world average of 3.3, yet with wide variation across the region (OECD, 2022[3]). Countries with abundant natural resources, like Angola and Mozambique, attracted over two‑thirds of FDI in extraction, electricity generation and construction, which are highly capital-intensive activities and exhibit the lowest job-intensity, averaging 0.8 and 1.1 jobs per million USD invested, respectively. Malawi and Seychelles also attracted considerable FDI in energy and construction activities with low job-intensity, while more diversified economies like Botswana and Mauritius attracted more labour-intensive FDI in manufacturing and services, respectively. Lesotho and Eswatini attracted the bulk of their inward FDI in garments manufacturing and food processing, and exhibit the highest job-intensity of FDI, with four and seven direct jobs created per million USD invested, respectively.

Figure 1.3. FDI-induced job creation varies according to its sectoral distribution

Note: The figures include all opened and announced greenfield FDI projects across SADC members between 20 003 and 2022.

Source: OECD elaboration based on Financial Times fDi Markets (2023[2]).

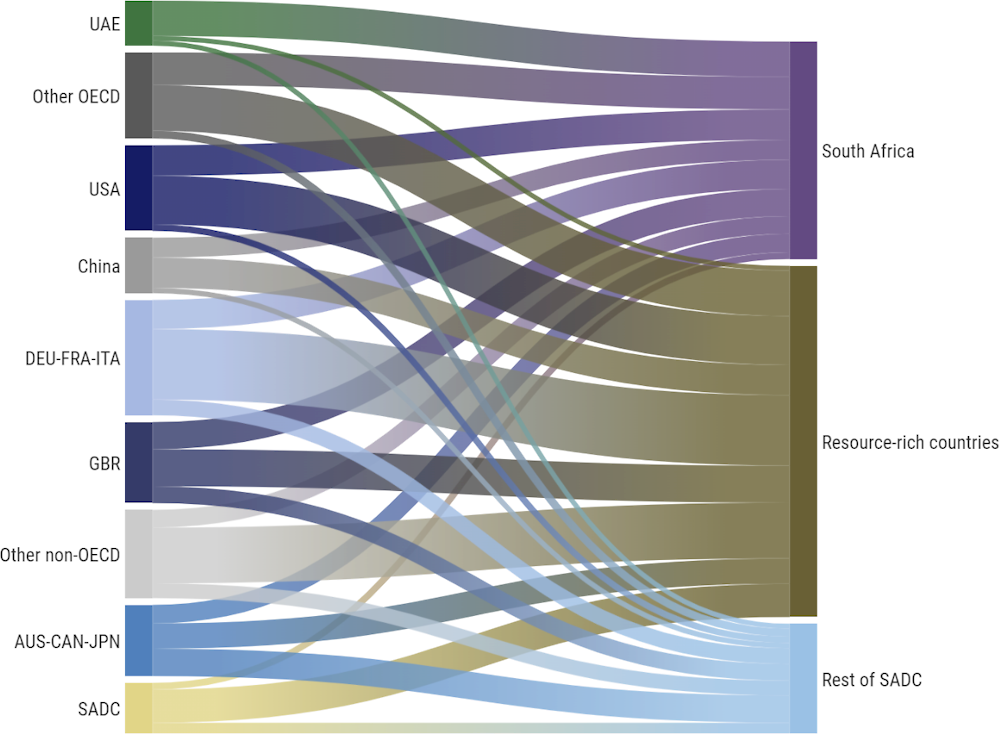

In light of the previous discussion, South Africa attracted 32% of the value of greenfield FDI projects in SADC while resource‑rich economies jointly attracted 52%, and the remaining SADC economies attracted 16% (Figure 1.4). Among resource‑rich countries, the main recipients of greenfield investments are Angola (20%) and Mozambique (15%), followed by Zimbabwe (7%), Zambia (6%) and Tanzania (6%). The largest source of greenfield investments in SADC over the last two decades is the USA (13%), followed by the UK (12%). Other major investors include France (8%), China (8%) and the UAE (7%), followed by South Africa, Italy and India, which each account for another 5% of greenfield FDI stocks. Other OECD economies including Canada, Australia and Germany have sizeable stocks of SADC FDI, at around 4% each, and invest relatively more in SADC countries that are less dependent on natural resources compared to the USA and European investors. OECD countries collectively account for two‑thirds of greenfield FDI in the region, while intra-regional investment from other SADC members accounted for 8%. After South Africa, Mauritius is the second largest intra-regional investor (1.3%).

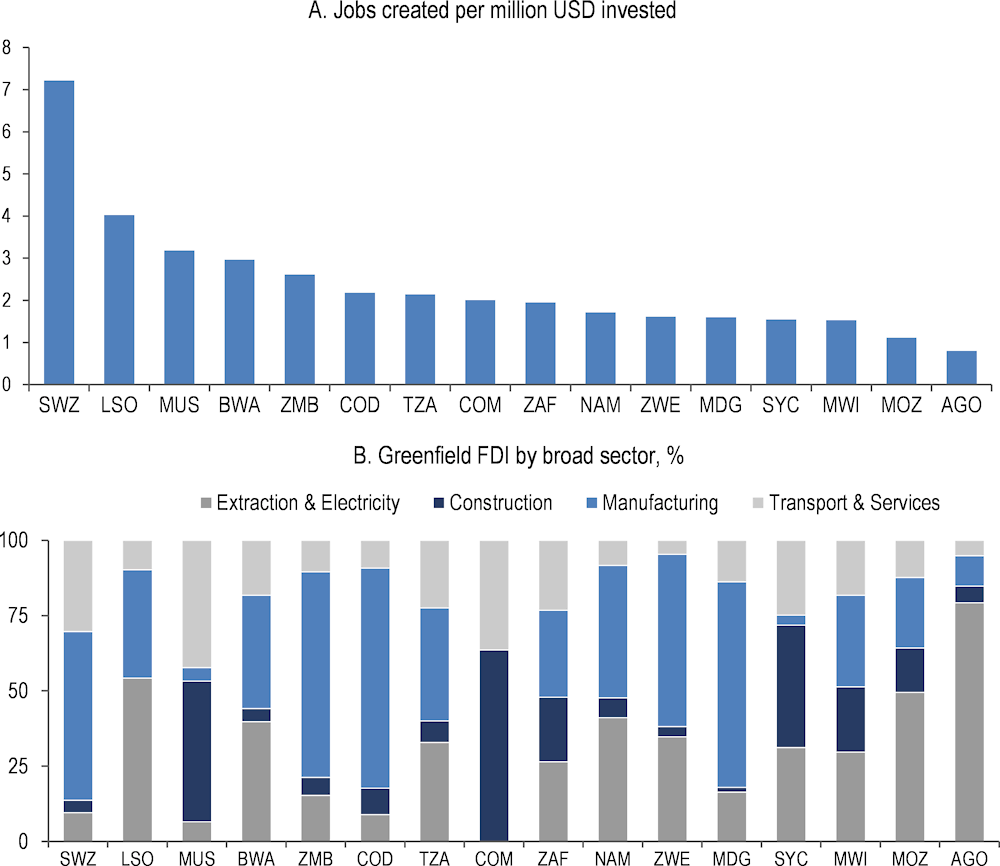

There is evidence that FDI offer additional advantages beyond the contribution to capital stock and jobs, by raising total factor productivity and the efficient use of resources in host economies, and bringing new technologies, skills and business practices. In SADC, firm-level data suggests that in most SADC countries, foreign companies are more likely to introduce new products or services than their domestic counterparts (Figure 1.5, Panel A). This pattern suggests that foreign investors have greater innovation capacity and that there may be opportunities for knowledge and technology transfers to local entities. Foreign firms are also more likely to offer training opportunities to their employees, and contribute to on-the‑job skills development, suggesting that FDI plays an important role in creating quality jobs and developing human capital (Figure 1.5, Panel B). The relationship between FDI and gender equality in the labour market appears less favourable. With few exceptions, foreign firms employ smaller shares of women in their workforce and are less likely to have female top managers than domestic peers (Figure 1.5, Panel C and D), as is the case also in other regions in the world (OECD, 2022[3]).

Figure 1.4. FDI flows to SADC originate from a diversified set of investors

Note: The figure includes all opened and announced greenfield FDI projects over 2003 and 2022. Resource‑rich countries (i.e. where natural resource rents account for at least 10% of GDP) include Angola, DR Congo, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Source: OECD elaboration based on Financial Times fDi Markets (2023[2]).

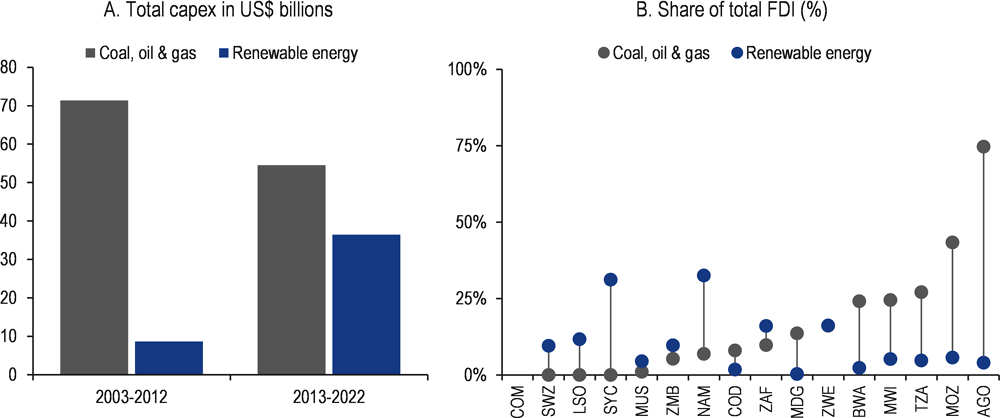

FDI can make a significant contribution to the energy transition by increasing renewable energy capacity, and indeed accounts for 30% of new investments in renewable energy, globally (OECD, 2022[3]). In SADC, fossil fuels still dominate the stock of FDI in the energy sector (74%). Nevertheless, the last decade saw a fourfold increase in the stock of FDI in renewable energy compared to the previous decade, while FDI in fossil fuels shrank by 24% (Figure 1.6, Panel A). At the same time, the variation across countries remains wide (Figure 1.6, Panel B). In Angola and Mozambique, fossil fuels account for 78% and 45% of total greenfield FDI accumulated since 2003, and over 94% of FDI stocks in the energy sector. In Tanzania, Malawi, and Botswana, fossil fuels account for over a quarter of overall greenfield FDI stocks and also dwarf renewable energy FDI. Madagascar, Zimbabwe and DRC also lag behind in terms of attracting renewable energy FDI. Conversely, in Namibia, Seychelles, Lesotho and Eswatini, renewable energy FDI dominates the energy sector and has attracted a sizeable share of greenfield FDI, ranging from 10% in Eswatini to 32% in Namibia. In Zambia and South Africa, the gap between renewable and conventional energy in terms of FDI attraction is smaller, but there is a clear trend toward greener energy.

Figure 1.5. FDI contributes to innovation capacity and skills

Figure 1.6. FDI in renewables has gained momentum in the last decade

Note: Figures include all opened and announced greenfield FDI in fossil fuel and renewable energy sectors, in SADC over 203 to 2022.

Source: OECD elaboration based on FT fDi Markets (2023[2]).

Key messages and considerations

Sustainable investment has been defined as “commercially viable investment that makes a maximum contribution to the economic, social and environmental development of host countries and takes place in the framework of fair governance mechanisms” (Sauvant and Mann, 2017[9]). A broader definition would consider that sustainable investment should contribute towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While an investment project can contribute to several SDGs, trade‑offs might also arise when an investment moves the host country closer to some SDGs but farther away from others.

As mentioned at the beginning of this report, the challenge for governments is not just to attract foreign investors at a time of diminishing global FDI flows, but also to ensure that the investment confers sustainable benefits on the host economy. Attracting investment and reaping the maximum benefit in terms of sustainability depend first and foremost on the overall policy framework in which investment occurs. Policymakers need to maintain a sound, transparent and open investment climate, and adopt policies that ensure the benefits of FDI are maximised and their potential harm on the local economy, society and environment are minimised. Furthermore, targeted promotion tools and measures to enable responsible business conduct (RBC) are equally important for a sustainable investment framework.

This requires whole‑of-government efforts, evidence‑based policy making and meaningful stakeholder consultations. This report looks primarily at what host governments can do to attract sustainable investment and promote the benefits of investment for social and environmental objectives, including how to facilitate and enable RBC. It provides an analysis to make SADC a preferred destination for national and foreign investment that is reinforced by effective governance that promotes sustainable and inclusive regional economic development. It is based on the OECD tools, including the Policy Framework for Investment and the FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit and Indicators. Key messages and main considerations that emerge from different chapters are summarised below.

Designing investment frameworks and strategies to promote sustainable investment

Increase coherence between national legislation and regional and continental treaties. The analysis suggests that national investment laws do not yet fully reflect innovations at a regional or continental level, although newer investment laws seem to be closer to regional practice. Furthermore, there is still considerable diversity in individual laws across the SADC region. Greater coherence in approaches within and across regions in Africa at all levels could contribute to improved clarity and predictability for both governments and investors, although sufficient room should be left for further experimentation at national level.

Consider further integrating SDG considerations into investment promotion strategies of SADC Member States and develop IPAs’ value propositions for sustainable investment opportunities accordingly. Several agencies in the region have put strong focus on attracting investment in sustainable development sectors and activities, such as renewable energy, the blue economy, sustainable agriculture, forest restoration and social inclusion initiatives. The value propositions for these sustainable investment opportunities should be further developed and better marketed with stronger communication on their related incentives, industry information and legal background. More targeted investment generation can also allow SADC agencies to select FDI projects that are more likely to contribute to the SDGs, including by prioritising investors with good sustainability track-records.

Put in place adequate KPIs to select priority investors and measure their sustainability impacts. While it is key to prioritise certain investments over others to respond to sustainability objectives, it is equally important to understand and track their contribution to the desired outcomes. Adopting the right KPIs is necessary to measure the results of the agency and the effective contribution of companies assisted by the IPA to sustainable development. SADC IPAs should also ensure that the KPIs used to select priority investments and measure their outcomes are aligned with national development objectives and the agencies’ overarching investment promotion priorities. Consider diversifying them to reflect all areas of the SDGs and include sustainable and inclusiveness considerations (e.g. low-carbon transition, gender equality, regional development).

Use the SDGs to guide IPA aftercare services to existing investors who wish to expand or reinvest. IPAs should not only focus on promoting sustainable investment through new investments, but also use the SDGs to guide them in the way they deliver aftercare services to existing investors, not only to retain them but also to support their potential expansion or reinvestment. IPAs in SADC could, for example, consider focusing aftercare activities on those investors with the highest sustainability impacts. They could also take advantage of these services to better promote responsible business conduct within the existing business community and encourage investors to comply with sustainability-related laws more systematically, as well as to embrace responsible practices in their business operations. SADC IPAs should also consider providing more systematically matchmaking services to connect local suppliers with foreign affiliates and, as such, support the development of SMEs and sustainable local value chains

Assessing use and design of investment incentives

Assess whether investment tax incentives are aligned with investment promotion strategies and sustainable development goals, and whether they are the best policy instrument to achieve these goals. SADC Member States offer a range of tax incentives to attract private investment, direct it into certain sectors and locations, and encourage certain activities. Most incentives offered in the region seek to support key sectors, notably manufacturing industries, agriculture and services. Several SADC Member States offer incentives that are fairly targeted to specific goals, including reducing the costs associated with skills training and renewable energy equipment. Yet, in some cases incentives are available to broad segments of the economy, increasing the risk of redundancy. Tax incentives are not always effective to attract investors, while tax revenues are crucial for delivering public goods and services, including those that affect the investment climate. Economic, social and environmental goals might be better supported by regulations or other policies, and tax incentives should be used in complement with wider development strategies.

Design incentives to generate investments and related outcomes that would not materialise otherwise. Use of corporate‑income tax exemptions is less widespread in SADC than in other regions. Most SADC countries offer primarily expenditure‑based incentives (tax allowances and credits), which reduce the cost of capital. Eleven countries offer tax allowances for costs related to training, R&D, and job creation. Governments that rely more on CIT reductions and exemptions could consider phasing out most costly benefits (as Namibia has been doing since 2020) and introducing more targeted types of incentives, that reduce the cost of specific expenses (e.g. training, R&D, machinery). Improving incentive design, by promoting desired outcomes through tax relief on qualifying expenditure, can help limit redundancies and encourage positive spillovers.

Improve monitoring of tax incentive uptake and costs, and evaluation of costs and benefits of policies. Better understanding of whether incentives contribute to policy goals, and at what costs, requires monitoring and evaluation. While some countries in SADC conduct tax expenditure reporting, most governments face administrative, fiscal, data and human resource constraints to carrying out in-depth evaluations. The SADC Secretariat can continue to advocate for improved monitoring and evaluation, including by supporting use of the recently reviewed SADC Tax Expenditure Model for Tax Incentives, and by further advancing co‑operation on commitments related to incentives under the Protocol for Finance and Investment.

Promoting investment for green growth

Strengthen NDC targets and develop long-term low-emission development strategies. Collectively SADC NDCs are not yet aligned with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Four countries have committed to achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, one by 2070, and another has already achieved is committed to maintaining net-zero. Only one country has submitted long-term strategy documents in addition to its NDCs. Ambitious long-term strategies are vital since current near-term NDCs are only sufficient to limit warming to 2.7‑3.7°C. Moreover, long-term strategies provide a pathway to a whole‑of-society transformation and a vital link between shorter-term NDCs and the long-term objectives of the Paris Agreement. Given the 30‑year time horizon, these strategies offer many other benefits, including guiding countries to avoid costly investments in high-emissions technologies, supporting just and equitable transitions, promoting technological innovation, planning for new sustainable infrastructure in light of future climate risks, and sending early and predictable signals to investors about envisaged long-term societal changes.

Use SADC as a platform to promote strategic environmental assessments (SEA) and transboundary environmental impact assessment (EIA). Southern African countries made great strides in formalising EIA into their legal frameworks, with most providing for the three critical procedural rights of access to information, public participation, and access to remedies. While most countries in the region have made SEAs a legal requirement, only three countries have developed regulations or guidelines that set out the procedures for their implementation, leaving considerable room for interpretation. Moreover, the application of EIA principles to the assessment of transboundary impacts of investment remains limited, and only one country provides a framework for the control and restriction of cross-border contamination. Recognition of transboundary SEA and EIA at the SADC level could encourage other SADC governments to adopt these tools in their national EIA systems.

Consider phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, and using freed up funds to mitigate adverse social impacts of climate policies. Overall, fossil fuels remain highly subsidised in Southern Africa, with total explicit and implicit subsidies amounting to USD 62 billion in 2020, and projected to rise in subsequent years. Following the surge in fuel prices since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic and exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, subsidy levels are set to rise with fuel prices, which may reduce government capacity to promote clean energy. Governments may resort to more targeted tools than subsidies on energy use to improve energy access and affordability. Phasing out subsidies could free up public funds for targeted support to ensure vulnerable groups access clean and affordable energy, but adequate compensation and support measures for those affected by subsidy reform should be put in place.

Promoting and enabling responsible business conduct

Increase awareness and understanding of Responsible Business Conduct (RBC). Although there has been some improvement in general awareness of RBC, including international standards and expectations for due diligence, many related initiatives are still in their initial phases, and most stakeholders in the region have limited awareness regarding RBC standards and approaches to due diligence. SADC and its Member States can strategically enhance awareness of the public and private sector as well as stakeholders and foster understanding of the importance of RBC in relation to trade and investment. This may involve organising capacity-building activities and workshops on international RBC frameworks and risk-based due diligence.

Strengthen the domestic policy framework governing RBC. At the regional level, SADC has established comprehensive policies that cover various areas, themes, and sectors, in relation to RBC and international RBC standards, as outlined in the SADC Investment Policy Framework. Although these frameworks serve as an initial recognition and effort to tackle RBC matters, there is still a need for further development of SADC’s policy frameworks that aim to foster and facilitate RBC. At the national level, SADC Member States have implemented a range of policies to tackle RBC concerns, and in some instances, they have begun incorporating RBC instruments into their legal systems. However, there is still a lack of comprehensive domestic regulations and specific action plans pertaining to RBC in the region. For instance, the establishment of clear expectations for due diligence has not yet been fully developed and adopted within SADC. National governments can take the lead by developing and implementing National Action Plans on RBC, as well as sector-specific or issue‑specific reforms.

Ensure policy coherence and harmonisation in line with international RBC standards. SADC serves as a platform for promoting coherence and harmonisation of RBC policies, aligning them with major international RBC standards notably the OECD MNE Guidelines and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBC. SADC can take further steps to achieve strong alignment and co‑ordination of RBC policies among its Member States, ensuring a unified approach and a level playing field at the regional level.

References

[5] African Union (2019), African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement, https://au-afcfta.org/afcfta-legal-texts/.

[2] FT fDi Markets (2023), Database of crossborder greenfield investments, https://www.fdimarkets.com/ (accessed on 30 January 2023).

[3] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Indicators: 2022, https://www.oecd.org/investment/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

[1] UNCTAD (2023), Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock, annual (Balance of Payments), https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds (accessed on 30 January 2023).

[4] World Bank (2022), World Bank Enterprise Survey, http://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys (accessed on 30 January 2023).