Competition in Tunisia’s market for bank loans to small businesses does not work as well as it could. The market for business loans is concentrated, with the five largest banks accounting for between 70% and 75% of all lending in 2021. Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises – 45% of which hold finance products only with their current account providers, and more than half of which do not compare offers among banks – tend to obtain finance from their current account providers and face significant barriers to shopping around. While aiming to protect vulnerable customers, the cap on lending interest rates has negative effects on lending markets, and historically Tunisian banks have imposed very high collateral requirements on borrowers – almost 300% of the value of loans, according to the World Bank. The lack of a private credit information bureau exacerbates larger banks’ credit information advantage and increases the cost of shopping around for credit, especially among small businesses, which has the effect of limiting their ability to do so. Finally, the influence of large industrial groups over banks increases small businesses’ barriers to access finance.

Competition Market Study of Tunisia's Retail Banking Sector

5. Bank loans to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises

Abstract

In 2018, 30% of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Tunisia regarded access to finance as a major barrier to growth, while 50% considered the cost of finance to be a major obstacle to expansion.1 This chapter assesses how competition works in the market for bank loans to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), their most common form of financing. Section 5.1 provides details of the main characteristics of loan products. Section 5.2 discusses the structure of the supply side, which is important because the relative size of providers has a significant effect on competition and market outcomes. Section 5.2.3 finds that state‑owned banks and banks connected with large industrial groups account for around 75% of total lending, which may restrict access to finance to small businesses in non-finance sectors. Section 5.3 discusses market outcomes. Given that granular data on loans is not available, the section relies on the perceptions of the businesses that use these products, expressed in the OECD’s MSME survey. Section 5.4 provides an assessment of demand behaviour. This is important because, for example, incentives to compete are weakened if borrowers do not shop around, or if banks expect them not to. The chapter also discuss potential effects of the cap on lending interest rates in Section 5.3.1.

5.1. Parameters of competition

MSMEs’ choices of loan products depend on whether they need finance in the short term to manage cash flow or in the longer term to grow their business or make investments.

Overdrafts are typically short-term loan facilities associated with business current accounts (BCAs). Business loans are often used by larger and more established MSMEs that need longer-term financing. Based on the OECD’s MSME survey, micro‑enterprises are more likely to apply for unsecured loans requiring no collateral than larger businesses (28% vs. 5% of enterprises with more than 50 employees). Larger businesses are more likely to apply for secured loans that require collateral. In the survey, 64% of loan applications were for either secured or unsecured loans.2

Leasing finance does not require MSMEs to provide collateral or a credit history, as lending risks are lower because the ownership of leased assets remains with the finance provider. Factoring is a tool used to facilitate cash flow as it allows MSMEs to sell debt and transfer the risk of the debtors’ insolvency to the factoring company. As for leasing, factoring finance does not require MSMEs to provide collateral or credit histories.

The reasons why MSMEs need finance vary widely and may depend on characteristics of businesses such as their size, age and activity. For example, smaller firms are more likely to need finance to start up operations, while larger businesses need it to grow.

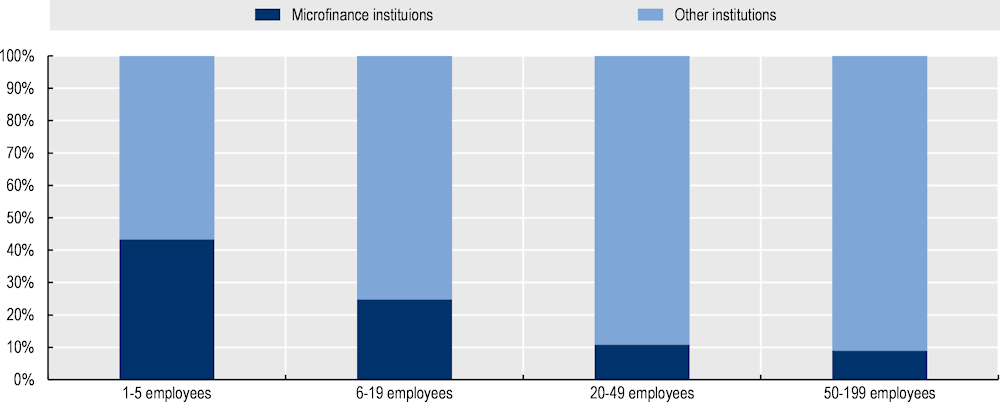

Loan products offered by banks may overlap with loan products offered by microfinance institutions. Microfinance loans in Tunisia cannot exceed TND 40 000 and are typically targeted at retail customers, professionals or micro‑enterprises that may lack credit histories or collateral. Interest rates on microfinance products are typically significantly higher than rates on bank loans. In 2021, the average taux effectif global, or global effective rate, on products offered by microfinance institutions was 31.8% [see Autorité de Contrôle de la Microfinance (2021[1]); Section 2.10], compared to 9‑13% for loan products from banks or leasing companies (see Table 5.2). Figure 5.1 shows that micro‑enterprises are more likely to use microfinance.

Loan products offered by banks, leasing firms and factoring companies are subject to a cap in Tunisia. Section 5.3.1 provides details of how the cap works and its potential effects on competition. Unlike bank finance, microfinance loans offered by microfinance institutions are not subject to the cap.

Figure 5.1. Proportion of MSMEs applying for loans from microfinance institutions, by firm size

Source: OECD MSME survey (Q31.1 and S1, N=183).

As opposed to the market for current accounts, in which the main criterion for choosing a provider is proximity to a branch, the most common reason for choosing a lender are the fees and conditions it offers (22% of respondents). The second most common reason is the range of services offered (19%). The fact that the lender is also a firm’s BCA provider is the third most common reason (17%). Branch proximity is the fourth most common reason (10%).3 Given MSMEs’ differing financing needs, where appropriate the chapter presents the results of the analysis broken down by different sizes of MSMEs.

5.2. Market structure and shares of supply

This section provides an overview of the supply side of the market for SME finance, presenting the main loan products available and the market shares of banks. This is a key element of the assessment of competition, as the structure of the sector may affect firms’ incentives to compete. The focus is on bank loans for businesses. Using a classification drawn up by the Central Bank of Tunisia, banks offer six loan products to businesses:

overdraft facilities

short-term credit (maturity of less than one year)

medium-term credit (maturity of one to seven years)

long-term credit (maturity longer than seven years)

leasing

factoring.

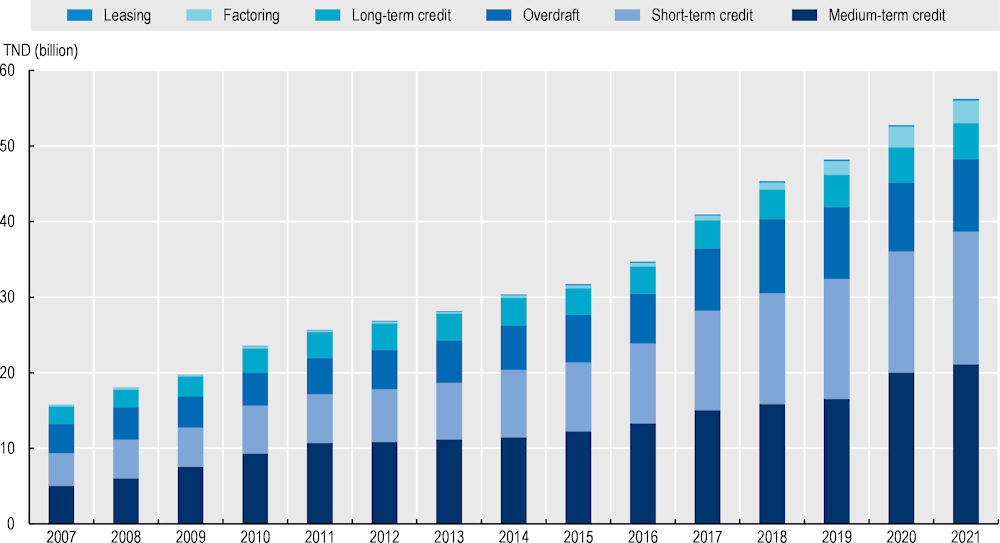

5.2.1. Recent trends in lending value

The BCT provided biannual data on the value and volume of various loan categories by bank for the 15‑year period between 2007 and 2021. The data had several limitations: it could not be broken down by borrower characteristics (thus, it includes both lending to MSMEs alongside larger businesses), it included loans for only the ten largest banks, and it did not include data on leasing and factoring companies. Despite these limitations, the data was useful for assessing trends over time and the relative importance of different types of loans.

The total amount loaned using these six products increased by around 250% between 2007 and 2021, from around TND 30 million to more than TND 100 million (see Figure 5.2). Over the same period, the total number of loans fell 13%. The total value of medium-term loans (the most common type of loan, accounting for around 32% of lending value), increased 320%, while the number of medium-term loans decreased 22% over the same period. As a result, the average value of medium-term loans increased 437% between 2007 and 2021, from TND 132 000 to TND 709 000. This was not driven by any single bank, as the average medium-term loan size increased at eight of ten banks. The average value of long-term loans increased 1 025% over the same period, from TND 65 000 to TND 737 000 (the average long-term loan size increased for nine of ten banks). By comparison, the average size of loans to consumers grew at the same rate. In fact, between 2007 and 2021, the average value of mortgage loans grew 118% and the average value of consumer loans increased 126%.

Although the analysis was limited by a lack of granular data, the significant increases in the average size of business loans were consistent with increased obstacles to accessing finance experienced by smaller enterprises.

Figure 5.2. Total lending value for selected products, 2007‑21

Note: Lending value of short-term credit (with and without overdrafts), medium-term credit, long-term credit, leasing and factoring by Tunisia’s 10 largest banks.

Source: BCT; OECD calculations.

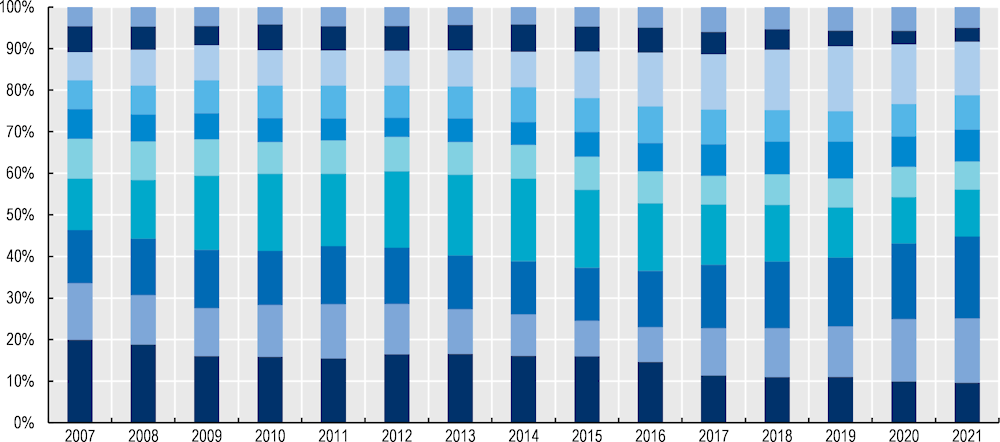

5.2.2. Shares of supply

Based on the data provided by the BCT, the aggregate shares of the five largest banks as of the end of 2021 were 69‑75%, depending on the product. Given that the state‑owned banks are controlled by one single entity (i.e. the state), it is possible to consider state‑owned banks a single entity, in which case the aggregate share of the five largest banks would be much higher. Figure 5.3 shows the shares of the ten largest banks, measured as outstanding loans at the end of each calendar year between 2007 and 2021, for medium-term loans, the most common loan type. Data provided by the BCT could not be broken down by borrower characteristics, and thus included both lending to MSMEs and to larger businesses. The aggregate shares of the largest five banks were 68% in 2007 and 69% in 2021. Four of the five largest providers in 2007 were also the largest providers in 2021.

Figure 5.3. Medium-term loan shares of supply of Tunisia’s ten largest banks

Note: Each colour corresponds to a bank. Data is anonymised.

Source: BCT data; OECD calculations.

Conclusions

Over the last decade, the market shares of Tunisia’s five largest banks have remained stable, accounting for around 70‑75% of lending value. Concentration levels would be significantly greater if state‑owned banks were considered to act as a single entity and if common shareholders and indirect interlocked directorates weakened incentives to compete, as described in Section 3.3 Moreover, the average size of business loans has increased significantly, which is consistent with increased obstacles to access to bank finance among smaller businesses, which typically apply for smaller loans.

5.2.3. Links between financial firms and non-financial industrial groups, and lending to related parties

Several stakeholders interviewed by the OECD were concerned about the connections between firms in the financial sector and non-financial industrial groups, and the effects of these links on access to finance among MSMEs. Stakeholders said that such connections may result in banks lending at favourable conditions to borrowers related to them via their ownership structures. This concern has also been expressed by the (World Bank, 2014[2]).

The OECD requested data on banks’ loan portfolios, including information on which loans had been granted to related borrowers over time. However, some of the key information in the dataset was not shared, so it was not possible for the OECD to assess the prevalence of these practices and their impact on competition. The following sections discuss the potential risks to competition and the relevant regulatory framework.

Potential effects on competition

Firms belonging to industrial groups connected to banks may have easier access to finance. While lending to related borrowers may reduce information asymmetries and therefore the cost of credit, related lending may also have negative effects on the economy. For example, if banks have some degree of market power and capital is a scarce resource, related lending may result in unrelated borrowers being excluded from financing.

As a result, related lending may create barriers to entry in non-financial sectors for borrowers that do not have connections with banks. This may negatively affect competition in other sectors by reducing the number of providers, weakening incentives to compete and reducing innovation. This may be particularly problematic for firms that are actual or potential competitors of the large domestic industrial groups that control banks. When related lending is performed by state‑owned banks, it may give state‑owned enterprises an advantage by providing easier access to finance than that obtained by private firms.

A condition for foreclosure effects to arise is that downstream firms – in this case Tunisia’s large domestic industrial groups – control a significant proportion of the upstream market – in this case the provision of bank loans to enterprises. Based on BCT data (which among other limitations included only loan data from the ten largest listed banks), Table 5.1 shows that as of the end of 2021, state‑owned banks and banks controlled by Tunisian industrial groups had granted around three‑quarters of all business loans.

Table 5.1. Proportion of outstanding loans by bank type, end‑2021

|

Bank type |

Number |

Medium term |

Long term |

Overdraft |

Short term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

State‑owned |

3 |

38% |

38% |

51% |

56% |

|

Controlled by Tunisian private investors |

3 |

34% |

35% |

26% |

20% |

|

Controlled by non-Tunisian investors |

4 |

28% |

27% |

23% |

24% |

|

Total |

10 |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Sources: BCT data; OECD calculations.

Regulatory framework on lending to related parties

The regulatory framework in Tunisia contemplates safeguards aimed at mitigating the concerns raised above. Circular No. 2018‑06 provides for specific rules limiting banks’ exposure to related borrowers and to multiple borrowers belonging to the same industrial group, with the primary objective being to avoid conflicts of interest and insufficient portfolio diversification. In particular, as of the end of 2018, Article 52 set the maximum amount of risk/exposure vis-à-vis “related parties” at 25% of banks’ net equity, down from 75%.4 Article 43 of Law No. 2016‑48 contemplates a broad definition of “related parties”, comprising connections through common directors and top management as well as through shareholdings exceeding 5% of a bank’s capital.5 6

Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD noted that these rules are not as effective as they could be. Despite a warning issued by the BCT, at least the three largest banks have exceeded the limit, according to annual reports. Table 5 of the BCT’s 2020 annual report on banking supervision shows aggregate information on the disciplinary measures taken by the BCT (Banque Centrale de Tunisie, 2022, p. 36[3]). However, given the aggregate nature of the information, it was not possible to understand which rules were breached.

Moreover, banks appear to engage in agreements whereby they lend to one another’s related parties, de facto exceeding the 25% threshold. One bank interviewed by the OECD said that when it approached the 25% threshold, it co‑ordinated with other banks to swap customers to remain below the limit. This conduct may be in breach of competition law as in so doing, banks share information on and allocate customers. It is not the role of this report to assess these allegations, but the OECD recommends that they should be considered by the appropriate authorities.

Box 5.1. Separation of financial and non-financial institutions

Other countries facing similar challenges involving links between financial and non-financial businesses have introduced legislation to limit the influence of large industrial groups on financial institutions. For example, in 2013, Israel introduced a Law for the Promotion of Competition and Reduction of Concentration to mitigate the control that a small number of people had over a significant proportion of Israeli economy. To reduce market concentration, its provisions prohibit large, non-financial corporations from holding majority stakes in large financial entities. The law also prevents financial entities from holding stakes of more than 10% in large non-financial institutions.

Source : Israel Competition Authority (2013[4]), Law for Promotion of Competition and Reduction of Concentration, https://www.gov.il/en/departments/legalInfo/concentrationlaw.

5.2.4. Conclusions

Related lending can lead to foreclosure for borrowers without connections to banks. This risk is higher for actual or potential competitors of the industrial groups that control banks. Stakeholders expressed concerns over related lending, and it is considered a significant barrier to entry and expansion for MSMEs in all sectors of Tunisia’s economy.

The analysis shows that connections between industrial groups and banks are widespread, and that a significant proportion of Tunisia’s 100 largest firms are connected to banks. It also shows that state‑owned banks and banks controlled by large industrial groups account for around three‑quarters of all business loans. The measures in place to mitigate this situation are not effective as they could be, as some banks have exceeded the threshold set by the BCT on lending to related parties.

Although the limited information available did not allow a detailed assessment of the prevalence of related lending and its potential negative effects on competition, these practices, combined with other aspects of the banking sector in Tunisia described in Chapter 3, may increase barriers to accessing finance among MSMEs and have negative effects on all parts of Tunisia’s economy.

5.3. Market outcomes

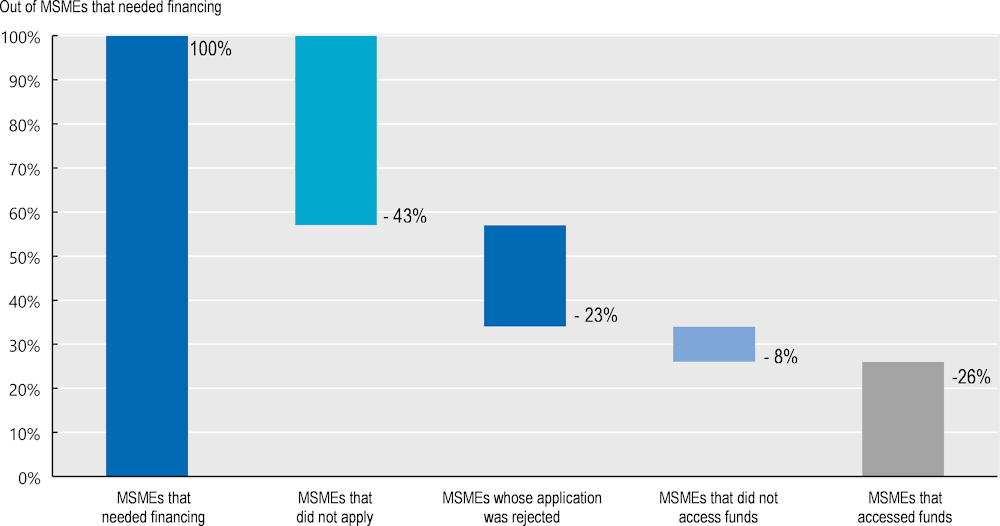

Analysis of market outcomes can provide useful information for understanding competition in markets and potential harm to customers. Given the lack of granular data on loan prices, and on the value and volume of lending to MSMEs, this section relies on the responses to the OECD’s MSME survey. The perceptions of businesses are useful for identifying the perceived obstacles when accessing finance and the reasons why, for example, firms that need finance do not even apply.

Respondents to the MSME survey indicated that the three major obstacles to accessing finance were excessive interest rates (83% of MSMEs agreed or strongly agreed), excessive collateral requirements (79%), and the length of the process (72%). Perceptions did not change significantly among different sizes of businesses.7

Figure 5.4 shows that among the MSMEs that needed finance over the five years leading up to the survey, 43% did not apply for finance,8 and 23% saw their applications rejected.9 8% of MSMEs did not withdraw funds, for example because banks’ loan decisions arrived too late, the amount granted was insufficient or the collateral too high.10 Among the respondents, 26% accessed funds.11 Lenders did not communicate the reasons for rejecting credit applications in more than half of cases.12

Figure 5.4. The MSME experience of accessing finance

Source: OECD MSME survey (Q29, Q31, Q41 and Q44, N=140).

Around 25% of the firms who needed finance and did not apply expected interest rates to be too high, and around 15% did not do so because the expected collateral requirements were too high. 43% used a source of finance other than a formal financial institution.13

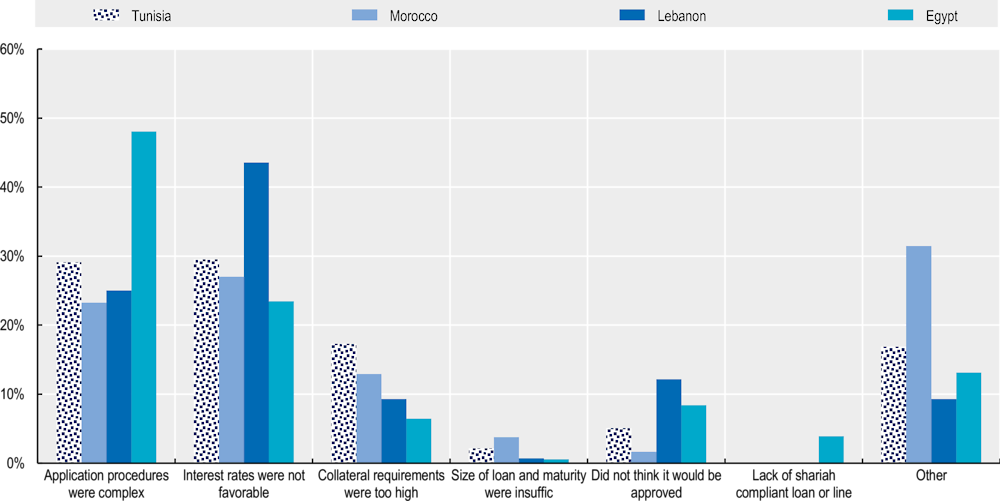

This is consistent with the results of the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, shown in Figure 5.5. In the World Bank surveys, Tunisian MSMEs considered high interest rates and high collateral requirements to be two of the biggest obstacles to accessing finance. Compared to other Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region countries, collateral was mentioned as a reason for not applying for loans more often in Tunisia than in Morocco, Lebanon and Egypt.

The next two sections discuss the cap on lending interest rates and collateral requirements in Tunisia.

Figure 5.5. Main reasons for not applying for new loans or new credit lines

Note: Due to data limitations, the OECD average and MENA average include only a selection of countries. Data is from surveys conducted between 2013 and 2020 (only four of 26 surveys were conducted before 2019). The chart is based on the most recent data for each country.

Source: World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

5.3.1. Cap on lending interest rates

Banks and financial institutions in Tunisia such as leasing and factoring companies are subject to a cap on lending interest rates set by the BCT every six months and which varies by loan product.14 Caps on lending interest rates are widely used in both developed and developing economies (see Box 5.2 for an overview). The cap on lending interest rates in Tunisia has been discussed in various reports by international organisations in recent years. According to the (World Bank, 2021[5]) Tunisia’s cap on lending interest rates prevents the optimal allocation of resources at the expense of riskier borrowers and SMEs. (Morsy, Kamar and Selim, 2018[6]) and the (World Bank, 2014[2]) said the cap led banks to exclude start-ups and businesses with insufficient guarantees. Unfortunately, no report includes an empirical assessment of the effects of Tunisia’s cap on its credit market.

Although one bank interviewed by the OECD said the cap did not create obstacles to financing, for some banks it represents a barrier to the accurate pricing of risk. One bank, for example, said the cap prevented it from engaging in price discrimination between low- and high-risk borrowers, as it could not charge higher interest rates to reflect higher risk. Another bank said that if a borrower were considered too risky and the price of a loan to it would be higher than the cap, it explored alternative finance arrangements, including equity financing or higher collateral requirements. A third bank said that it often priced loans at the level of the cap, suggesting that the cap is binding on a large proportion of its loans. Another stakeholder said leasing companies faced higher refinancing costs than banks (which also offer leasing products), so the cap on leasing products had the potential to squeeze leasing companies out of the market.

The remainder of the section provides a description of the cap in Tunisia and its potential impact on lending markets.

The cap on lending rates

Law No. 1999‑64 and secondary legislation drafted by the Ministry of Finance and the BCT introduced a cap on the interest rates of eight different loan products.15 The cap is calculated for each lending product and is relative to the average interest rate observed during the previous six months. The cap was originally set at 133% of the average rate of the previous six months. It was reduced to 120% in 2008 (Law No. 2008‑56) and restored to 133% in November 2022 to take effect from January 2023. The cap is set on the annual effective interest rate, and it covers all fees and charges (Article 2 of Law No. 1999‑64). 16 The cap does not apply to microfinance products.

There is no clear timeline for the periodic publication of the next period’s cap. This may increase market uncertainty and compliance risks as to which interest rate conditions to apply.17 Table 5.2 shows the average market rate between January and June 2022, and the value of the cap between July and December 2022.

Table 5.2. Average market rate, January-June 2022 and cap, July-December 2022, by credit product

|

Credit product |

Average market rate in Jan-Jun 2022 (%) |

Cap in Jul-Dec 2022 (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Short-term loans |

8.84 |

10.60 |

|

Long-term loans |

8.94 |

10.72 |

|

Medium-term loans |

9.30 |

11.16 |

|

Mortgages |

9.30 |

11.16 |

|

Factoring |

10.37 |

12.44 |

|

Consumer credit |

10.56 |

12.67 |

|

Overdrafts |

10.63 |

12.75 |

|

Leasing |

13.33 |

15.99 |

Source: Order of the Minister of Finance, 17 August 2022.

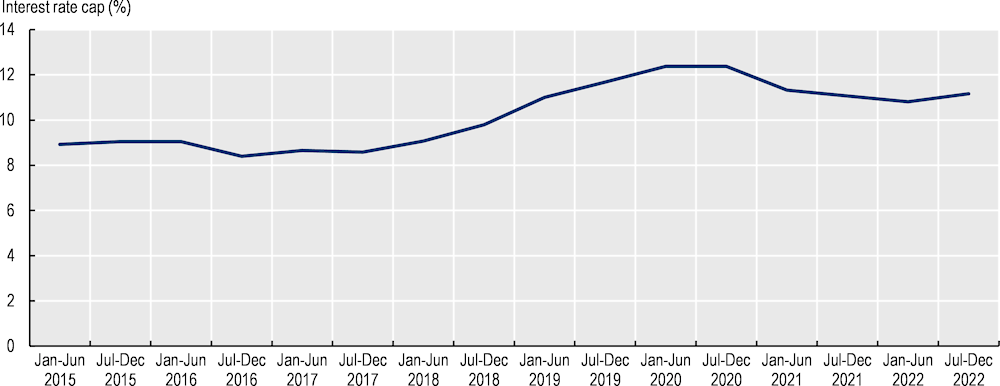

Figure 5.6 shows that the cap on medium-term loans – the most common loan product – remained relatively stable between January 2015 and January 2018. The cap was 8.92% in the first half of 2015 and equal to 9.07% in the first half of 2018. It then increased to 12.38% in the first half of 2020 (given that the cap is based on the market average of the previous six months, this increase was not due to the COVID‑19 pandemic). The fact that the cap was relatively stable between January 2015 and June 2018 implies that it was not binding on all loans offered during that period (if it had been, it would have increased 20% in each period). Nevertheless, the cap may still bind some loans, for some banks or in some periods. This is discussed in the next section. Trends among caps on other loan products were similar.

Figure 5.6. Cap on medium-term loans, January 2015 to December 2022

Sources : Jurisite Tunisie (2023[7]), Les taux d’intérêts effectifs moyens (TIEM) et les seuils des Taux excessifs correspondants, https://www.jurisitetunisie.com/tunisie/index/taux/index.html#topcontent; OECD calculations.

The cap is binding on some but not all loans

A bank offers many loans in each period, each with a potentially different interest rate. Without the cap, the interest rates charged would form a distribution. The introduction of the cap may cut the higher end of the distribution. If that happens, applications for loans that would have been priced higher than the cap may either be rejected or may be accepted with lower interest rates (for example, equal to the cap) and banks may compensate for that through such measures as requiring higher levels of collateral.

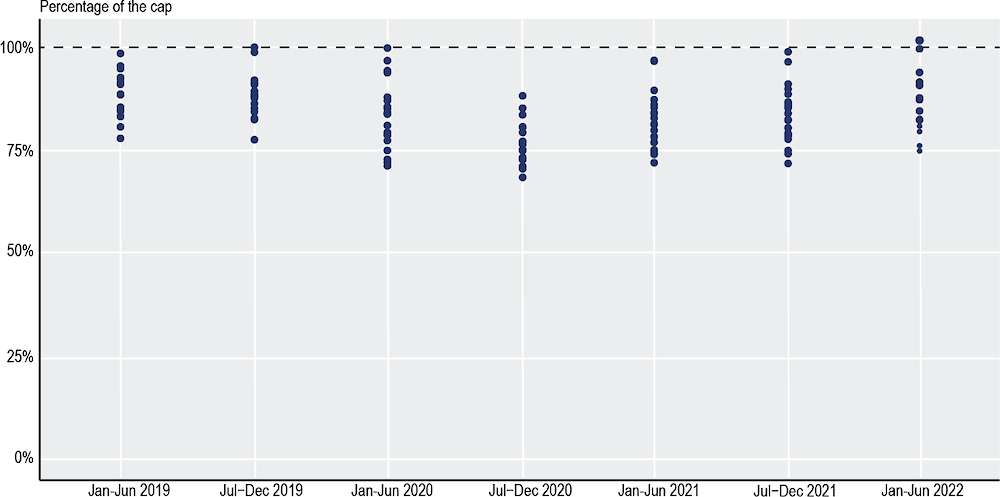

The OECD did not have access to loan-level data on interest rates or to the distribution of interest rates across loans. It was thus not possible to assess how often banks price their loans at rates equal or close to the cap. The BCT provided the six‑month average interest rates charged by each of the 22 banks on each lending product over the period from January 2019 to December 2021. This is the same data that banks submit to the BCT for the calculation of the cap.

Each dot in Figure 5.7 is the average interest rate charged by a bank in a six‑month period for medium‑term loans, the most common type of business loans. Figure 5.7 shows that in the six months between June and December 2019, the average interest rate charged by one bank were equal to the cap. This means that the bank charged an interest rate equal to the cap for each loan granted in the period. The average interest rate charged by another bank was equal to 99% of the cap. This means that most of the loans offered by the bank were priced at the cap. Conversely, in the same period, another bank charged an average interest rate equal to 77% of the cap. Based on this information, the bank may or may have not priced some loans at the cap, and it certainly priced many loans well below the cap. In other periods, such as during the six months between June and December 2020, no bank charged on average more than 85% of the cap.

This suggests that pricing strategies vary significantly across banks, with some pricing closer to the cap than others. The average interest rates charged by some banks are sometimes very close or equal to the cap, which means that, for these banks, most loans are priced at (or very close to) the cap.

Figure 5.7. Average medium-term loan interest rates charged by banks as a proportion of the cap, January 2019 to December 2021

Note: Each dot is the average interest rate charged by a bank in a six‑month period for medium-term loans.

Source: BCT data; OECD calculations.

The dispersion of average interest rates charged by banks over time varies between loan products.

Potential effects of the cap on competition

Despite its stated objective of protecting vulnerable consumers and reducing the overall cost of credit, the cap may have negative consequences. It may prevent banks from pricing risk accurately, which leads to distortions in the lending market that may reduce access to financing.

Credit providers may decide not to serve riskier borrowers or seek to obtain higher guarantees for loans in the form of collateral, which may exclude firms that lack such collateral. Smaller enterprises and start-ups are more likely than other businesses to be affected by this, because they are typically riskier (for example, because they do not have long credit histories), they are less likely to have collateral, and they are more likely to request smaller loans, which are less profitable (Reifner, Clerc-Renaud and Michael Knobloch, 2010[8]).

The cap also reduces the ability of providers to respond to cost shocks. For example, given that the cap is set relative to the average of past market rates, an unexpected increase in costs, such as in the base rate, may reduce firms’ profitability and, in certain cases, may make it unprofitable to serve riskier customers.

The effects of the cap could also be asymmetric, and it may have a greater impact on providers that already have higher overheads, such as leasing companies, which have higher financing costs than banks, as discussed above. To mitigate this risk, under Article 6 of Decree No. 2000‑462, in exceptional circumstances, the BCT may adjust its calculation to consider large variations of economic conditions within a given six‑month period. The OECD is not aware of any instances in which the BCT has used this power. Data on average interest rates and lending volumes provided by the BCT show that banks that make smaller loans on average charge higher prices, closer to the cap. This is consistent with concerns that the effect of the cap is asymmetric, and that smaller banks are more constrained by it than larger banks.

The cap may also be used as a focal point to facilitate co‑ordination. For example, (Knittel and Stango, 2003[9]) found that credit card providers in the US in the 1980s used price caps to facilitate co‑ordination. This may be inconsistent with BCT data showing that average interest rates vary across banks, but given that the data is aggregated (making it impossible, for example, to observe the distribution of interest rates) and does not include information on borrowers, it is not possible to conclude whether the cap is a focal point for co‑ordination.

Finally, stakeholders said the BCT’s guidelines for banks on calculating effective interest rates on lending products leave room for interpretation and that, as a result, banks use differing methodologies. This may create an uneven playing field.

Conclusions on the cap

Identifying the effects of caps on lending interest rates is complex because they are often introduced as a response to the economic environment, and this makes it difficult to observe their causal effects and distinguish them from other factors. In addition, an assessment of caps involves trade‑offs of different effects, as they may decrease interest rates, at least for some categories of customers.

Several banks interviewed by the OECD said that Tunisia’s cap prevented them from pricing risk accurately, leading them to exclude riskier borrowers and making them vulnerable to shocks.

The data available to the OECD did not allow a detailed assessment of the cap, but the OECD’s analysis found that the cap was likely to be binding for at least some banks on a significant proportion of loans, and that smaller banks with lower lending volumes charged on average higher prices, closer to the cap. This is consistent with the theory whereby the effect of the cap represents a more significant constraint for smaller banks.

Box 5.2. Lending rate caps: international experience

In 2018, the World Bank found that 76 countries imposed some restrictions on interest rates on loan products (Ferrari, Masetti and Ren, 2018[10]). It found 30 instances since 2011 in which new caps on lending rates had been introduced or existing restrictions had been tightened (and, in more than 75% of cases, these instances were in lower-income countries).

Interest rate caps can take many forms. They can vary in terms of the scope of products covered and they can be set at differing levels for different product types. Caps can also vary in how they are calculated, as they can be absolute or relative. Relative caps can be calculated based on a variety of benchmarks (e.g. the central bank base rate or an average market rate). Caps can be a multiple of the benchmark rate, or they can be calculated as the benchmark plus a fixed spread. Finally, caps can be applied to all financial costs of loans (i.e. interest rates, fees and commissions), see (Munzele, Claudia and Gallegos, 2014[11]) and (Ferrari, Masetti and Ren, 2018[10]).

Caps typically have two broad sets of objectives. First, in many jurisdictions, the objective is to avoid the charging of extortionate rates in order to protect vulnerable consumers. The caps in these countries are typically set at a high level to affect only extreme prices. Second, in other jurisdictions, caps are used to reduce the overall cost of credit and are set at levels closer to or lower than market rates.

Empirical evidence

The policy objectives of caps make quantitative analyses of their effects particularly challenging. This is because caps are often introduced as a response to the economic environment, which makes it difficult to identify their causal effects and distinguish them from other factors. Also, the heterogeneity of caps between countries makes international comparisons difficult. Despite these challenges, many studies have sought to identify the effects of interest rate caps around the world. Caps typically reduce lending interest rates and reduce access to credit for riskier borrowers, and total lending may or may not be affected. For example:

Comparisons of caps in relatively homogenous states in the US suggest that low interest rate caps typically reduce total consumer credit and reduce access to credit for lower-income borrowers. (Reifner, Clerc-Renaud and Michael Knobloch, 2010[8]).

Comparisons among EU countries, whose interest rate caps are typically higher than those in the US and are specific to certain high-cost credit products, found that although credit to high-risk borrowers is reduced, this market segment is relatively small and unlikely to have an impact on total consumer credit. (Reifner, Clerc-Renaud and Michael Knobloch, 2010[8]).

The IMF assessed the impact of the introduction of a cap on interest rates on microfinance loans in Cambodia in 2017. Using a difference‑in-difference approach, it found that the cap led to a significant increase in non-interest fees (that were not included in the calculation of the cap), a reduction in the number of borrowers, and an increase in the total sums loaned out. The last two findings suggest that banks served larger borrowers at the expense of smaller ones (Heng, Chea and Heng, 2021[12]).

The World Bank assessed the introduction of a cap on lending interest rates in Kenya in 2016. It found that total lending declined, non-performing loans increased, and that banks loaned more to safer corporate borrowers at the expense of SMEs. It also found a negative effect on interest rates paid on deposits (Safavian and Zia, 2018[13]).

5.3.2. Onerous collateral requirements

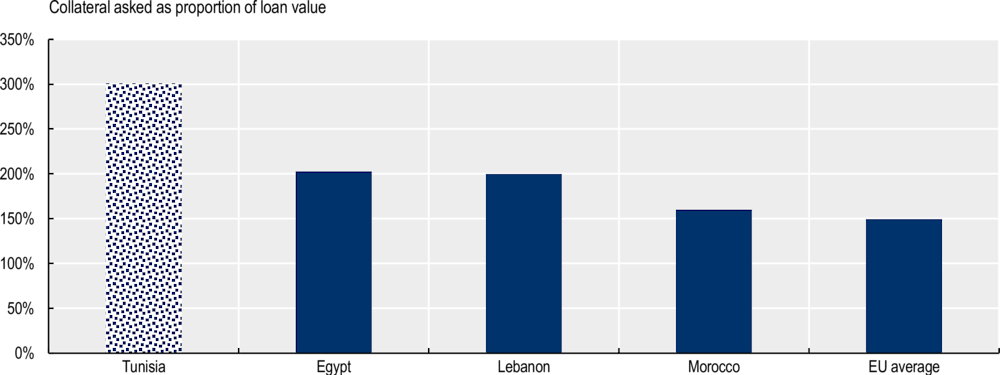

This section considers banks’ requests for collateral and the extent to which these are a significant barrier to accessing finance. According to the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, the average collateral requested of MSMEs in Tunisia is almost 300% of loan values, the highest among the countries in the enterprise surveys dataset (see Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.8. Collateral requirements in Tunisia vs. other countries

Note: Due to data limitations, the OECD average includes only a selection of countries. Data is from surveys conducted between 2013 and 2020 (only four of 26 surveys were conducted before 2019). The chart is based on the most recent data for each country. Egypt has a cap on lending interest rates but Lebanon and Morocco do not.

Source: World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

Article 25 of Circular No. 2006‑19 prescribes that to assess credit risk, banks should consider elements relating to the financial situation of the beneficiary (in particular its ability to repay) and that collateral obtained should be considered only of secondary importance. In practice, in Tunisia, collateral is required for most loans. Based on the OECD’s MSME survey, 82% of firms that successfully applied for credit were asked to provide collateral. This is consistent with the results of the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, which found that in 2020, Tunisian banks required collateral on 83% of loans approved. This was a similar proportion to Egypt and Lebanon, and significantly higher than Morocco and any of the OECD countries in the database.

Despite the widespread use of collateral, stakeholders indicated that creditors struggle to enforce collateral rights in a timely manner and take ownership of collateral after defaults. It appears that this is due mainly to lengthy court proceedings and, in cases involving movable goods, to the absence of a collateral registry. A large body of research examines how laws on collateral affect access to finance. For example, (Calomiris et al., 2017) showed the importance of borrowers’ ability to use movable assets as collateral and they found that loan-to-value ratios (the value of a loan divided by the value of its collateral) of loans collateralised with movable assets was lower in countries with weak collateral laws.

Existing schemes to provide guarantees to MSMEs, such as those operated by the Société Tunisienne de Garantie (SOTUGAR) are not as effective as they could be. Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD said the existence of a SOTUGAR guarantee does not significantly affect the conditions of the loan, such as its price, and that banks typically ask for collateral in addition to a SOTUGAR guarantee. The SOTUGAR is used mostly by Tunisia’s five largest banks (two private and three state‑owned) and by the development-focused Banque de Financement des Petites et Moyennes Entreprises (BFPME). Around one‑quarter of SOTUGAR guarantees are on loans granted by BFPME and around half of guarantees are on loans granted by the country’s three large state‑owned banks.

5.3.3. Conclusions on market outcomes

High interest rates and collateral requirements have been consistently identified as the main obstacles to accessing finance in Tunisia. In particular, the collateral requested by banks is the highest among the countries in the dataset of the World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

High collateral requirements may have several causes. The cap on lending interest rates may lead banks to require high collateralisation ratios and banks may reduce the risk of customers not repaying their loans by requiring collateral. Another cause may be the limited ability of Tunisian banks to assess risks, due to, for example, limited information on the creditworthiness of existing and prospective customers. This is discussed in Section 5.5. Finally, the risk of not being able to enforce collateral rights increases credit risk and may lead banks to require higher levels of collateral from all borrowers.

5.4. MSME behaviour

An important element of the assessment of competition is the analysis of how MSMEs behave when seeking finance. For example, if banks expect MSMEs not to compare loan conditions among providers, banks do not have incentives to offer cheaper loans to prevent borrowers from seeking alternatives. This section reports evidence from the OECD’s MSME survey on credit product holdings, the propensity to shop around, and barriers to seeking financing. The MSME survey shows that:

Some MSMEs use BCAs as a gateway to establish relationships with banks and obtaining additional services such as financing (around 16% of the respondents to the MSME survey said they chose their BCAs for that reason; see Section 4.2).18

MSMEs are significantly more likely to obtain financing from their BCA providers than from other sources. Among respondent MSMEs, 45% held credit products only with their BCA providers and 31% said they had credit facilities with both their BCA providers and other banks, while 21% did not hold credit products and only 3% of respondents said they held no credit products with their BCA providers and some credit products with other banks (see Figure 4.2).19 MSMEs may do so for a variety of reasons. For example, they may value the convenience of sourcing all their financial products from their BCA providers, reducing the sunk costs of searching and establishing several banking relationships, and making it easier to manage their credit holdings. MSMEs may also have increased access to financing when using their BCA providers. Lenders rely on credit and payment histories to assess creditworthiness and make lending decisions, and in Tunisia they may not have reliable sources of information on new customers. Thus, lenders may be unable to accurately assess risk among new customers and may therefore charge high interest rates, impose high collateral requirements, or decline credit applications.

Around 67% of respondent MSMEs did not compare fees and other conditions among providers. The propensity to shop around varied significantly by firm size. Only 14% of micro‑enterprises compared terms offered by more than one provider, compared with around 35% of firms with between 50 and 199 employees. Smaller firms were more likely to be newer and may not have extensive credit histories, limiting their options when shopping around for financing.20

Among the MSMEs that compared fees and conditions, around 22% used information from the websites of financial institutions and around 43% used financial advisers.21 Almost one in three MSMEs that compared fees and conditions found it hard or very hard.22 37% said they found it hard or very hard because information was presented in differing formats.23

This section first presents the main obstacles to accessing finance as understood by MSMEs. It then considers the MSME journey to finance and quantifies the proportion of MSMEs that drop out at each stage of that journey.

5.5. Lack of a credit information bureau

Tunisia does not have a private credit information bureau. Although the BCT maintains a registry with information on consumers’ and enterprises’ outstanding loans (see Section 2.2.3),24 several banks and other stakeholders said the information held by the BCT was insufficient to make accurate lending decisions because it does not include information on companies and individuals with no outstanding loans, because it includes only negative information on such events as missed payments or defaults but no positive information on payment histories and balances, and because it does not include information on non-financial products.

Other reviews have described the lack of a private credit information bureau as hinderance to the growth of credit markets in Tunisia. For example, the World Bank (2021[5]) said the introduction of a private credit information bureau in Tunisia could improve access to credit among MSMEs because it would offer a means by which credit providers could assess risk.

5.5.1. A credit information bureau could reduce information asymmetries and reduce related arbitrage among big banks

When deciding whether to grant loans, banks typically assess borrowers’ creditworthiness. To do this, they may use information they hold in-house on prospective borrowers (for example, because they are existing customers or if they have previously requested loans), they may rely on the information provided at the application stage, or they can use information from other sources, such as credit information bureaus or credit referencing agencies. The information made available by bureaus can vary widely and may include information on financial products such as a borrower’s total number of loans, repayment history, previous defaults, and on non-financial products such as utilities payment histories. Credit information bureaus reduce information asymmetries between lenders and borrowers by consolidating information on (potential) borrowers from a range of sources and making it available to lenders. The effect is greater when the lender is an institution that has no existing relationship with a prospective borrower.

Credit information bureaus reduce adverse selection by allowing lenders to assess applicants’ credit risk more accurately, therefore reducing overall risk and the cost of lending. Credit information bureaus also reduce moral hazard by sharing information on missed payments and defaults, and therefore increase the cost of defaulting. Finally, credit information bureaus have a positive impact on competition, as they reduce the information advantages of larger banks, which rely on the amount of data on their larger customer bases. These larger customer bases allow them both to gain a better understanding of credit risk and more complete information on credit applicants.

Credit information bureaus can be public or private. While in principle the ownership structures of bureaus do not necessarily make a difference, (OECD, 2010[14]) suggests that credit markets with state‑owned credit information institutions are associated with greater perceived barriers to accessing finance. This may be because the objectives of public bureaus vary from those of private bureaus. The main objective of state‑owned bureaus is typically banking supervision. This implies, for example, that non-financial information, such as payments for utilities, is not included. As a result, such bureaus may have no information on firms that have never accessed financing. Public bureaus may not include smaller loans, as these are less likely to pose a threat to financial stability. Finally, public bureaus may not offer services to help banks making lending decisions, such as credit-scoring or anti-fraud services.

5.5.2. The regulatory framework for credit information bureaus in Tunisia

In 2014, Mitigan Credit and Insurance Bureau, a Tunisian financial services company, launched a project to establish a private credit information bureau in Tunisia. However, the bureau is still not operational.

Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD indicated that several potential reasons, including delays in introducing a legislative framework to offer the service in the country and a lack of co‑ordination between commercial banks. Given the first-mover disadvantage, the benefits of sharing information with a credit information bureau materialise only when several banks have already joined. Other reasons mentioned include the reluctance of the BCT to allow a private company to offer credit information services that would compete with its public registry.

In January 2022, Tunisia’s president adopted Decree‑Law No. 2022‑2 to regulate the establishment of credit information bureaus, the exercise of their activities, and exchanges of relevant information.25 The decree introduces a capital requirement of at least TND 3 million (Article 10). It also introduces several elements that give the BCT the discretion to reject authorisation, such as “fit and proper” status considerations and requirements relating to the professional experience of credit information bureau directors.

5.5.3. Conclusions

A well-functioning market for credit information is an important component of a lending market. However, the delays in adopting a regulatory framework in Tunisia have so far prevented the entry of a private provider of services based on credit information. The 2022 decree regulating credit information bureaus introduces several unnecessary barriers to entry, such as the high capital requirements of TND 3 million (in European countries, by contrast, no such capital requirements exist).

The limited availability of high-quality credit information may prevent lenders from accurately assessing risk, especially risk associated with new borrowers that may lack existing banking relationships. This reduces incentives to lend to new borrowers such as start-ups or less established MSMEs and may make banks excessively reliant on collateral. The absence of credit information-sharing arrangements also increases barriers to entry and expansion for smaller and newer banks, because larger banks have larger databases and a superior ability to assess risks. Finally, the lack of a credit information bureau increases barriers to switching for existing borrowers.

5.6. Other regulatory restrictions affecting lending conditions

Circular No. 1987‑47, as further amended and complemented, requires banks to comply with stringent conditions for lending to businesses, including MSMEs and professionals. These conditions are complementary to the cap on interest rates described above, and they concern such issues as the maximum maturity of loans and the maximum amount of capital that banks can grant, often calculated as a percentage of the value of the relevant project/product/sales. This imposes additional unnecessary constraints on the ability of banks to set the terms of loans and it seems to lack justification by any public policy objective.

5.7. Conclusions

Competition in the market for bank loans to small businesses is not working as well is it could in Tunisia. The market for business loans is concentrated, with the five largest banks accounting for 70‑75% of total lending in 2021. The shares of supply of these banks have been stable between 2007 and 2021.

The MSME survey highlights the importance of relationship lending and MSMEs’ limited propensity to shop around for financial products. Establishing banking relationships is an important reason for choosing BCA providers, and for 45% of businesses, BCA providers are the only sources of financing. The survey also found consistently that more than half of all MSMEs did not compare fees and other terms of loans among providers, reducing the competitive pressure that they could exert. The lack of a private credit information bureau can exacerbate the information advantages of larger banks and increase the cost of shopping around for credit and switching providers, especially among small businesses.

The analysis also shows that Tunisian banks rely heavily on collateral when granting loans. According to the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, the average collateral required of MSMEs in Tunisia is almost 300% of loan values, the highest among the countries in the enterprise surveys dataset (see Figure 5.8). This is due partly to the cap on lending interest rates, which aims to protect vulnerable customers but prevents banks from accurately pricing risk.

References

[1] Autorité de Contrôle de la Microfinance (2021), Rapport de revison des comptes.

[3] Banque Centrale de Tunisie (2022), Rapport Annuel sur la Supervision Bancaire - Exercice 2020.

[10] Ferrari, A., O. Masetti and J. Ren (2018), Interest Rate Caps The Theory and The Practice, http://econ.worldbank.org.

[12] Heng, D., S. Chea and B. Heng (2021), “Impacts of Interest Rate Cap on Financial Inclusion in Cambodia”, IMF Working Papers, Vol. 2021/107, https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513582634.001.A001.

[4] Israel Competition Authority (2013), Law for Promotion of Competition and Reduction of Concentration, https://www.gov.il/en/departments/legalInfo/concentrationlaw (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[7] Jurisite Tunisie (2023), Les taux d’intérêts effectifs moyens (TIEM) et les seuils des Taux excessifs correspondants, https://www.jurisitetunisie.com/tunisie/index/taux/index.html#topcontent (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[9] Knittel, C. and V. Stango (2003), “Price Ceilings as Focal Points for Tacit Collusion: Evidence from Credit Cards”, Vol. 93/5, pp. 1703-1729.

[6] Morsy, H., B. Kamar and R. Selim (2018), Tunisia Diagnostic paper: Assessing Progress and Challenges in Unlocking the Private Sector’s Potential and Developing a Sustainable Market Economy, http://www.ebrd.com/publications/country-diagnostics.

[11] Munzele, S., M. Claudia and A. Gallegos (2014), Interest Rate Caps around the World Still Popular, but a Blunt Instrument, http://econ.worldbank.org.

[14] OECD (2010), Discussion Paper on Credit Information Sharing, https://www.oecd.org/global-relations/45370071.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2022).

[8] Reifner, U., S. Clerc-Renaud and R. Michael Knobloch (2010), Final report of the Study on interest rate restrictions in the EU.

[13] Safavian, M. and B. Zia (2018), “The Impact of Interest Rate Caps on the Financial Sector Evidence from Commercial Banks in Kenya”.

[5] World Bank (2021), Réformes économiques pour sortir de la crise - Région Moyen-Orient et Afrique du Nord.

[2] World Bank (2014), The Unfinished Revolution: Bringing Opportunity, Good jobs and Greater Wealth to all Tunisians, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/tunisia/publication/unfinished-revolution (accessed on 28 April 2022).

Notes

← 1. The Institut Tunisien de la Compétitivité et des Etudes Quantitatives (ITCEQ) is a public market research agency based in Tunis.

← 2. OECD MSME survey (Q31, Q33 and S1, N=804).

← 3. OECD MSME survey (Q35, N=183).

← 4. At the end of 2017, the limit was reduced from 75% (Article 23 of Law No. 2001‑65) to 25% of banks’ net equity.

← 5. Moreover, Article 51 prescribes that the level of risk vis-à-vis the same beneficiary shall not exceed 25% of net equity, with borrowers affiliated to the same group regarded as the same beneficiary. For breaches of Articles 51‑52, the BCT may impose fines of up to 2.5% of the amount above 25% (see Circular No. 2018‑06, Article 55, and Annex Relative à la Grille des Sanctions Pécunières). In addition, Article 43 of Law No. 2016‑48 requires banks and other financial institutions to adopt policies to manage conflicts of interest.

← 6. Article 43 of Law No. 2016‑48 requires banks and other financial institutions to adopt policies to manage conflicts of interest and, to this end, it entrusts the BCT to lay down rules governing transactions with (and in particular lending to) related parties. In addition, from a governance perspective, Article 58 of Law No. 2016‑48 prohibits individuals from holding top management functions (such as director general or deputy-director general) at banks and other businesses concurrently.

← 7. OECD MSME survey (Q48, N=986).

← 8. OECD MSME survey (Q29 and Q31 and N=322).

← 9. OECD MSME survey (Q29 and Q41 and N=183).

← 10. OECD MSME survey (Q44, N=141).

← 11. OECD MSME survey (Q44, N=141 and Q42, N=127).

← 12. OECD MSME survey (Q45, N=29).

← 13. OECD MSME survey (Q31 and Q32, N=139).

← 14. Microfinance institutions and crowdfunding platforms are not subject to the cap (the interest rate for services offered by the latter is set by law).

← 15. The cap was imposed initially on short-term loans, overdrafts, personal loans, medium-term loans, long-term loans, mortgages, student loans and leasing. In 2006 the BCT removed the cap from student loans and in 2013 the BCT imposed it on factoring products.

← 16. Under Article 5 of Law No. 1999‑64, breaches of the cap are subject to criminal fines and imprisonment. Decree No. 2000‑462 provides guidance to calculate the effective interest rate and the average interest rate. Each bank submits to the BCT (see Article 5 of Decree No. 2000‑462) the unweighted mean of the interest rates it has charged in the previous six months. The market average is the unweighted mean of rates submitted by each bank. The BCT then conducts spot checks with credit providers to check compliance. Pursuant to Article 5 of Decree No. 2000‑462, the average effective interest rates and the corresponding excessive interest rate thresholds are published in the Official Journal in the form of a Ministry of Finance order.

← 17. For example, the average market rate for the period January-June 2022 and the value of the cap for the period July-December 2022 were published on 17 August 2022. Also, the average market rate for the period July-December 2021 and the value of the cap for the period January-June 2022 were published on 31 January 2022, and the average market rate for the period January-June 2021 and the value of the cap for the period July-December 2021 were published on 1 September 2021. See Nouveaux seuils des taux d’intérêt excessifs des crédits au titre du deuxième se (ilboursa.com).

← 18. OECD MSME survey (Q13, N=804).

← 19. OECD MSME survey (Q27, Q=804 and Q28, N=1 005).

← 20. OECD MSME survey (Q6, N=804).

← 21. OECD MSME survey (Q6 and Q38, N=44).

← 22. OECD MSME survey (Q6 and Q39, N=44).

← 23. OECD MSME survey (Q40, N=21).

← 24. Access to information held by the BCT is regulated under Circular No. 2019‑09. Fees are charged for offline access to most information (Article 5 and Annex 2). Online access is subject to the creation of an account, which still requires an offline registration procedure (Article 3).

← 25. Circular No. 2022‑09 sets out authorisation procedures and documents to submit to the BCT.