This chapter focuses on the role evaluation plays in ensuring effective and impactful development co-operation. The dual evaluation objectives of accountability and learning remain steadfast. However, persistent challenges in ensuring consistent use of evaluation findings have led to greater focus on the learning objective. This chapter also reviews the overall number of evaluations undertaken by different types of organisations, setting the context for subsequent chapters that explore the driving forces and processes behind evaluations.

Evaluation Systems in Development Co-operation 2023

2. The role of evaluation

Abstract

2.1. Evaluation purpose

Evaluation plays an essential role in development co-operation. It is a vital tool for maximising the impact of development co-operation efforts. At its core, development evaluation is a process that critically examines a policy, programme or project to better understand whether, and how, it has delivered the intended results. Institutions have put in place unique governance arrangements to ensure evaluation systems provide relevant, objective, and impartial insight into the performance of development efforts, while connecting country-level data and evidence with decision makers, who are often removed from day-to-day implementation and results.

“The Department uses evaluation to assess its policies, strategies, programmes, projects and other initiatives to generate evidence that provides both accountability for public funding and learning to inform strategic and operational decision making.”Ireland, Department of Foreign Affairs

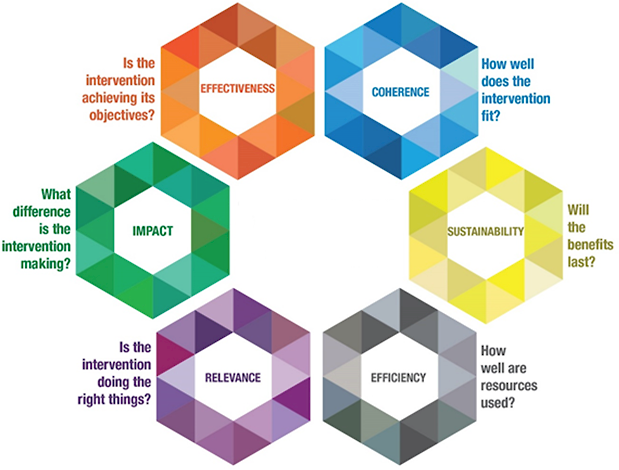

Evaluation helps answer critical questions about interventions and their results. These questions are captured in the six criteria defined by the OECD-DAC (Figure 2.1). Evaluation questions include: Is the intervention doing the right things? How well does the intervention fit? Is it achieving its objectives? Is it implemented coherently and efficiently? Is it having positive impacts that last? (OECD, 2021[1]).

Figure 2.1. OECD evaluation criteria

Source: OECD (2021[1]), Applying Evaluation Criteria Thoughtfully, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/543e84ed-en

In the current global context, evaluation is more critical than ever. Eight years ago, countries around the world adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. As we pass the halfway point in implementing this ambitious agenda, it is clear that progress has not been fast enough. The global community remains off track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. Persistent poverty and inequality, deadly conflicts, gender inequality and the climate crisis all threaten people. These challenges have been further exacerbated in recent years by the COVID-19 pandemic, growing disaster risks from climate change, rising food and fuel prices, and violent conflicts that have led to record levels of people being displaced.

The development financing landscape puts further stress on development initiatives. Aid budgets face downward pressure in many countries, while development organisations are pushed to demonstrate results and value for money. In this context, it is important to think critically about development co-operation systems and structures to ensure that each development dollar is spent on relevant priorities and has maximum impact.

Accountability and learning are the dual objectives of development evaluation. Accountability in development co-operation, between governments and development partners, as well as towards citizens, civil society and other development stakeholders, is essential for effective development activities and maximising impact. Accountability in development co-operation means ensuring all resources are used efficiently and as intended. It also goes beyond this, ensuring that results are achieved and co-operation delivered in a way that supports inclusive, green and sustainable development.

“Evaluations contribute to the ongoing streamlining of innovation of the development co-operation programme as a whole by making recommendations for the improvement of future development interventions.”Czechia, Department of Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid

Learning is an equally important evaluation objective. Development evaluations provide important data and evidence on why an approach has worked or has not, as well as whether results are contributing to overall development goals and whether they are sustainable. When evaluation findings are used to inform future planning and resourcing decisions, the quality of co-operation is improved. In this vein, evaluation findings, including lessons learned and success factors, are used alongside complementary research to design future policies, programmes and projects.

In line with past findings, participating organisations highlighted that both accountability and learning objectives remain central. The 2016 study noted that organisations aimed to find a balance between accountability and learning (OECD, 2016[2]). Similarly, all respondents in 2022 noted that the purpose of evaluations includes both accountability and learning dimensions. However, interviews confirm an increasing focus on the learning function of evaluation (further details can be found in Chapter 5), as well as on results reporting.

The recent focus on learning reflects challenges in systematically using evaluation findings to inform decision making and strengthen overall effectiveness. During the 2022 data collection process, including written submission and interviews, participants highlighted a strong focus on the use of evaluation findings to drive organisational learning and to support evidence-based decision making. This is not to say that one objective is more important than the other. Rather, it indicates that more work can be done to facilitate the use of evaluation findings (see Chapter 5).

2.2. Number and type of evaluations

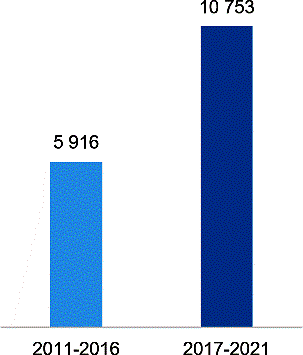

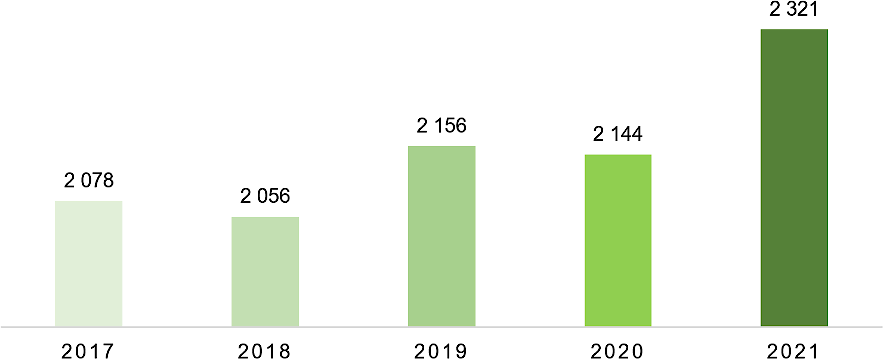

The overall number of centralised and decentralised evaluations undertaken by participating organisations has increased in the past decade.1 This demonstrates the significant value participating organisations place on evaluative evidence and reflects a growing appetite for evaluations from programme staff and other audiences. The number of evaluations conducted in the 2017-2021 period increased 82 percentage points over the 2011-2016 period (Figure 2.2). Over 2017-2021, the number of evaluations undertaken remained relatively steady (Figure 2.3), despite a slight drop in 2020 – likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic – and a jump in 2021 when travel restrictions were eased in most member countries allowing for evaluation units to catch up on some planned evaluations.

Figure 2.2. Total number of evaluations, 2011-2016 vs 2017-2021

Note: Data on the number of evaluations conducted were reported by 34 members and observers in 2022, and these varied slightly from those reporting in 2016, the two time periods are therefore not perfect comparisons. However, the conclusion of an increase in the total number of evaluations increasing is supported by other data sources including interviews and member submissions to EvalNet.

Figure 2.3. Total number of evaluations, 2017-2021

Note: Data on the number of evaluations conducted were reported by 34 members and observers, although the datasets vary slightly between 2011-2016 and 2017-2021. Not all participating centralised evaluation units reported on the number of decentralised evaluations.

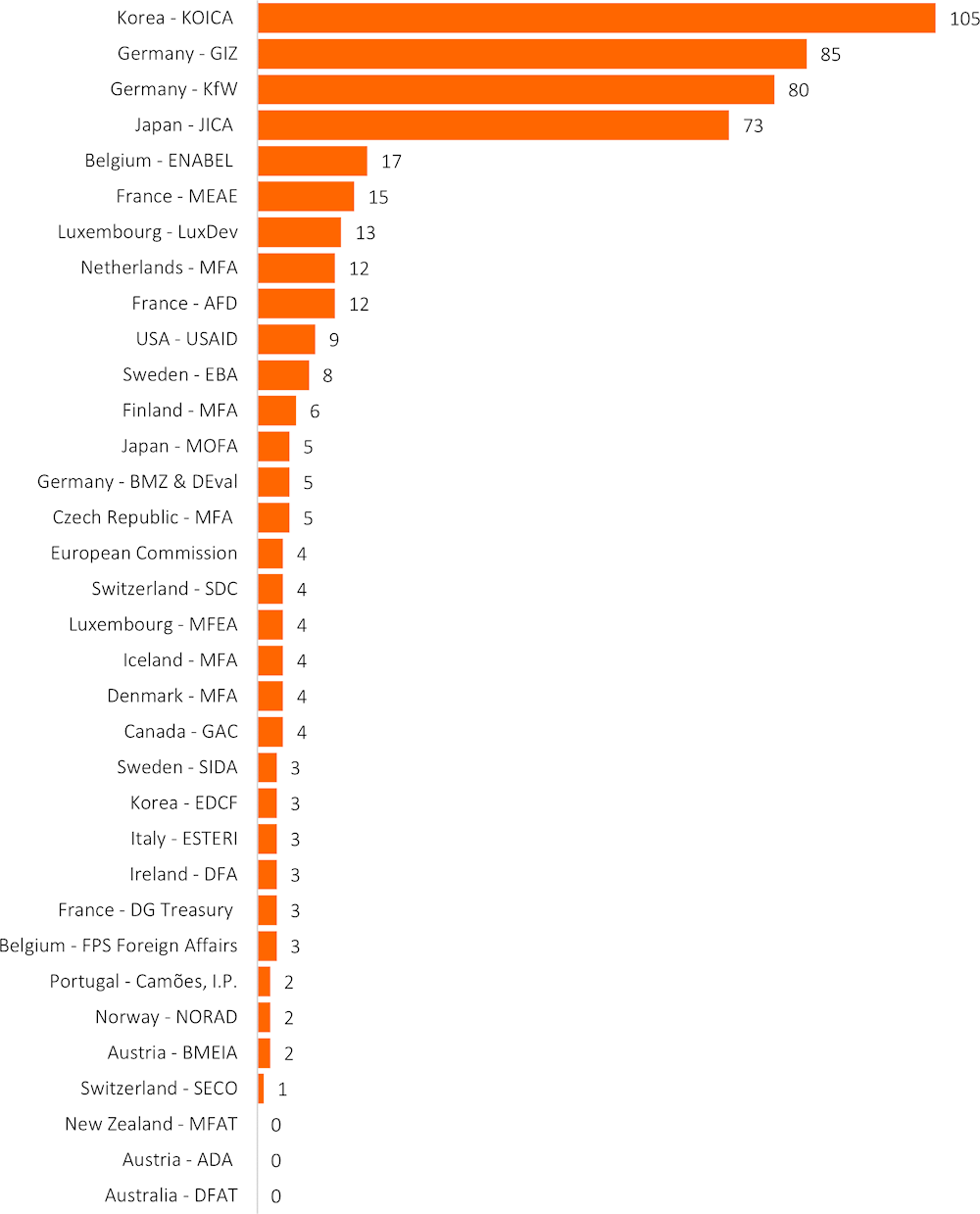

Figure 2.4. Total number of centralised evaluations conducted in 2021, bilateral organisations

Note: Data on the number of evaluations conducted were reported by 35 out of 42 bilateral organisations responding to the questionnaire (several members reported data from multiple institutions).

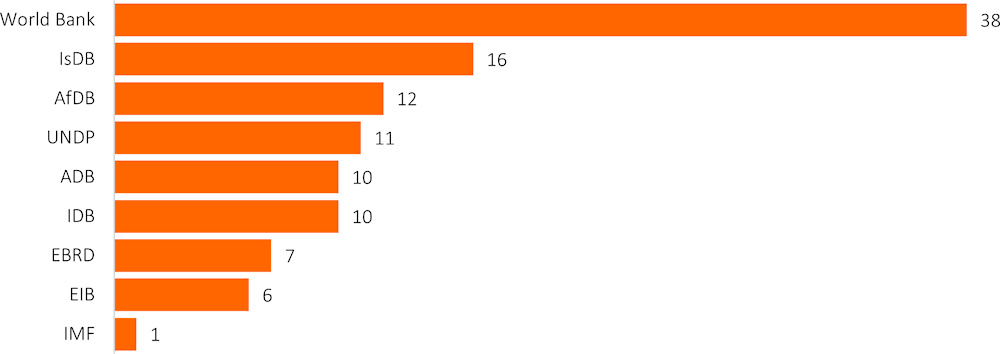

Figure 2.5. Total number of centralised evaluations conducted in 2021, multilateral organisations

Note: Data on the number of evaluations conducted was reported by 9 out of 9 multilateral organisations that responded to the questionnaire. See Table 1.1 for multilateral acronyms.

The number of evaluations conducted by reporting institutions varies greatly across organisations. Of the responding evaluation units, only a handful conduct more than 50 centralised evaluations (Figure 2.4,Figure 2.5). Conversely, 27 respondents conducted 10 evaluations or fewer (see Annex C). This reflects the significant diversity in the mandates, roles, and resourcing of evaluation units and the size and composition of the portfolios covered, rather than the overall size of the organisation per se. For example, KfW’s evaluation unit is mandated to evaluate the programmes and projects that it implements on behalf of BMZ, while DEval has a crosscutting function, covering all German development assistance (Box 2.1). In contrast, in the Netherlands, one evaluation unit is mandated to cover all Dutch development assistance, as well as foreign policy and trade activities that impact partner countries.

The age and size of bilateral organisations do not systematically affect the number of evaluations conducted, which is instead driven by the role evaluation plays within an organisation and the institutional set-up. Analysis was conducted to determine whether the age of the organisation and the amount of official development assistance (ODA) provided (both in terms of total amount and as a share of gross national income – GNI) influences the number of evaluations undertaken. No such relationship was found. This reflects the significant diversity in how development organisations set up and use their evaluation function. For example, some participating organisations conduct many centralised evaluations themselves. Other organisations focus more on decentralised evaluations, with centralised units providing an oversight or quality assurance function, or only conducting a smaller number of strategic evaluations.

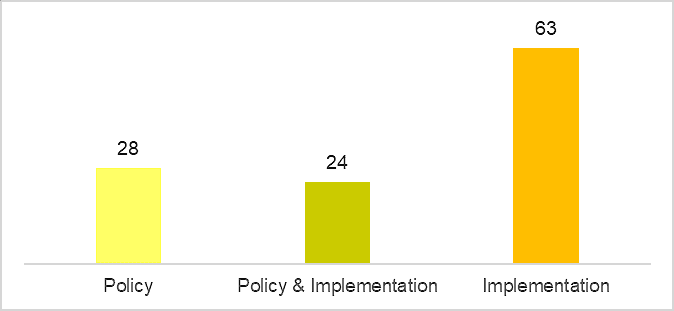

Multilateral organisations conduct more evaluations overall than bilateral organisations, and implementing agencies conduct more evaluations than those with a policy-focused role. On average, in 2021, multilateral organisations conducted 123 evaluations (centralised and decentralised), compared to 35 for bilateral organisations. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which is a relatively new institution, has just begun conducting evaluations and is therefore not included in the overall dataset for this study (Box 2.2). When comparing the number of evaluations undertaken by organisations with different roles (primarily policy, primarily implementation or a dual role), analysis found that implementing agencies conduct more evaluations, on average (Figure 2.6). As can be seen in the individual profiles (Annex C), 2020 – and to a lesser extent 2021 – saw a dip in the number of evaluations conducted, due to pandemic-related challenges including travel restrictions.

Figure 2.6. Average number of evaluations conducted in 2021, by role

Note: Data on number of evaluations conducted were reported by 44 out of 51 reporting organisations. Not all participating centralised evaluation units reported on the number of decentralised evaluations.

Most organisations use both centralised and decentralised evaluations. Centralised evaluations, undertaken by units in headquarters, often focus on high-level policies, strategies or themes. Decentralised evaluations are undertaken by evaluation units of implementing agencies and by programmatic units or country offices, and often focus on specific sectors, programmes or projects.

There is significant variety in the types and methodologies of evaluations conducted. Across participating organisations, centralised evaluation units conduct many different types of evaluations, including policy/strategy evaluations, sector programme evaluations, country programme evaluations, project evaluations, process evaluations, thematic evaluations, cluster evaluations, impact evaluations; and syntheses or meta-evaluations (Box 2.3).

Box 2.1. Evaluation in Germany

Overall responsibility for development evaluation in Germany falls under the remit of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Under the direction of BMZ, other key actors in this system are: the German Institute for Development Evaluation (DEval); the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ); and the KfW Development Bank (KfW).

The Evaluation Unit within BMZ provides overall direction to the evaluation system. This includes setting standards and overseeing their implementation, as well as ensuring coherence among evaluations undertaken by all organisations within the system. Since the foundation of DEval in 2012, BMZ’s evaluation unit only conducts evaluations in exceptional cases.

DEval is mandated by the German federal government, through BMZ, to conduct evaluations of German development co-operation. It conducts a variety of types of evaluations, contributes to the setting of evaluation standards and conducts capacity building. GIZ and KfW are the two largest implementing agencies of BMZ. Both organisations conduct evaluations related to their work and develop learning processes and products for their own activities.

Box 2.2. Evaluation at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was established in 2016 and is still in the process of fully establishing its learning and evaluation function. It is therefore not included in the overall dataset for this study.

The Complaints-Resolution, Evaluation and Integrity Unit was envisioned in the Bank’s Articles of Agreement. A Terms of Reference (ToR) was included in AIIB’s 2019 Oversight Mechanism and a Learning and Evaluation Policy was approved in 2021. The policy recognised the importance of building a fit-for-purpose approach and a corporate and learning culture to support institutional performance, continuous improvement, and credibility for this young Bank ─ all aspects of accountability. A small professional staff implements the Learning and Evaluation Policy, working with task-specific consultants, consistent with AIIB’s portfolio size and values.

The Learning and Evaluation team reports to the Board quarterly on annual workplan implementation, providing Members and Bank staff with valuable lessons from its activities and those of peer multilateral development banks. For example, it conducts Early Learning Assessments annually to identify findings, lessons and evaluability in selected on-going Bank financing. Going forward, it will undertake Project Learning Reviews (independent post-evaluations) of completed Bank financing. The Policy and Strategy Committee of the Board discusses each assessment and review. Similarly, peer independent evaluation departments are invited to discuss their evaluation findings and recommendations with AIIB staff in quarterly Practitioner Dialogues. The unit is also an EvalNet observer and a member of the COVID-19 Global Evaluation Coalition.

As was found in 2016, the links between centralised evaluation units and colleagues conducting decentralised evaluations are often weak. This is usually because there is no comprehensive evaluation workplan that includes all evaluations undertaken by the organisation. In some cases, there is no full accounting of all decentralised evaluations undertaken. However, some centralised units, for example in FCDO, do provide guidance, advice and quality assurance support to other parts of the organisation, allowing for a more complete understanding of the evaluation portfolio across departments.

“A large majority of the decentralised evaluations are deemed to be useful. However, insights from decentralised evaluations are not systematically exploited for organisational learning but [instead] remain on the individual level.”Finland, Development Evaluation Unit

About half of evaluations conducted in 2021 were decentralised, though due to limited reporting this is likely an underestimate. Of the total 2 321 evaluations reported by participating organisations, 760 (33 %) were conducted or commissioned by centralised evaluation units. Some 1 032 decentralised evaluations were conducted (44 %). However, as noted, this study focuses on centralised evaluation units in headquarters. While data were collected on both centralised and decentralised evaluations, detailed information on evaluations undertaken by specific programmatic units, country offices or projects was not specifically included in the data collection and therefore is likely undercounted in these figures.

Box 2.3. Evaluation types

In June 2023, the OECD published the second edition of the Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results-Based Management. This glossary provides definitions for the common types of evaluations:

Cluster evaluation: An evaluation of a set of related activities or interventions, either similar interventions in different locations or a cluster of complementary components of an overall initiative.

Country programme evaluation: Evaluation of one or more institution’s or partner’s portfolio of interventions in a specific country, including the strategy behind them in a specific period of time.

Impact evaluation: An evaluation that assesses the degree to which the intervention meets its higher-level goals and identifies the causal effects of the intervention. Impact evaluations may use experimental, quasi-experimental and non-experimental approaches.

Meta-evaluation: The term is used for evaluations designed to synthesise findings from a series of evaluations. It can also be used to denote the assessment of an evaluation to judge its quality or scrutinise the performance of the evaluators. Process evaluation: An evaluation of the internal dynamics of implementing organisations, their policy instruments, their service delivery mechanisms, their management practices and the linkages among these.

Programme evaluation: Evaluation of a set of interventions, combined to attain specific global, regional, country, or sector development objectives.

Project evaluation: Evaluation of an individual intervention designed to achieve specific objectives within specified resources and implementation schedules, often within the framework of a broader programme, examining its relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability.

Sector programme evaluation: Evaluation of a cluster of interventions within one country or across countries, all of which contribute to the achievement of a specific goal.

Thematic evaluation: Evaluation of a selection of interventions, all of which address a specific sustainable development priority or topic, that cuts across countries, regions, and sectors.

Source: OECD (2023[3]) Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results-based Management for Sustainable Development (Second Edition) https://doi.org/10.1787/632da462-en-fr-es

References

[3] OECD (2023), Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results-based Management for Sustainable Development (Second Edition), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/632da462-en-fr-es.

[1] OECD (2021), Applying Evaluation Criteria Thoughtfully, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/543e84ed-en.

[2] OECD (2016), Evaluation Systems in Development Co-operation: 2016 Review, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264262065-en.

Note

← 1. Participants were asked to report on the total number of evaluations conducted by their organisations in 2021 – both centralised and decentralised. However, kindly note that not all participating centralised evaluation units reported on the number of decentralised evaluations, and several have provided only an estimate.