This section examines key differences and commonalities in policy design and scope of the measures included in this review. The first part of the comparative review focuses on the scope of the measures. The second part of the comparative review focuses on the due diligence process and approaches to enforcement, with a focus on mandatory measures.

Review of G7 Government-led Voluntary and Mandatory Due Diligence Measures for Sustainable Agri-food Supply Chains

3. Comparative review of identified policy measures

Copy link to 3. Comparative review of identified policy measuresAbstract

While the measures vary in design, scope and objective, several commonalities can be identified in how they promote sustainable agricultural supply chains, as well as the extent to which they reference or draw on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct or the OECD RBC due diligence guidance and OECD-FAO Guidance on Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains. This analysis can help G7 policy makers and other stakeholders better understand some similarities and differences in approach across the policy measures.

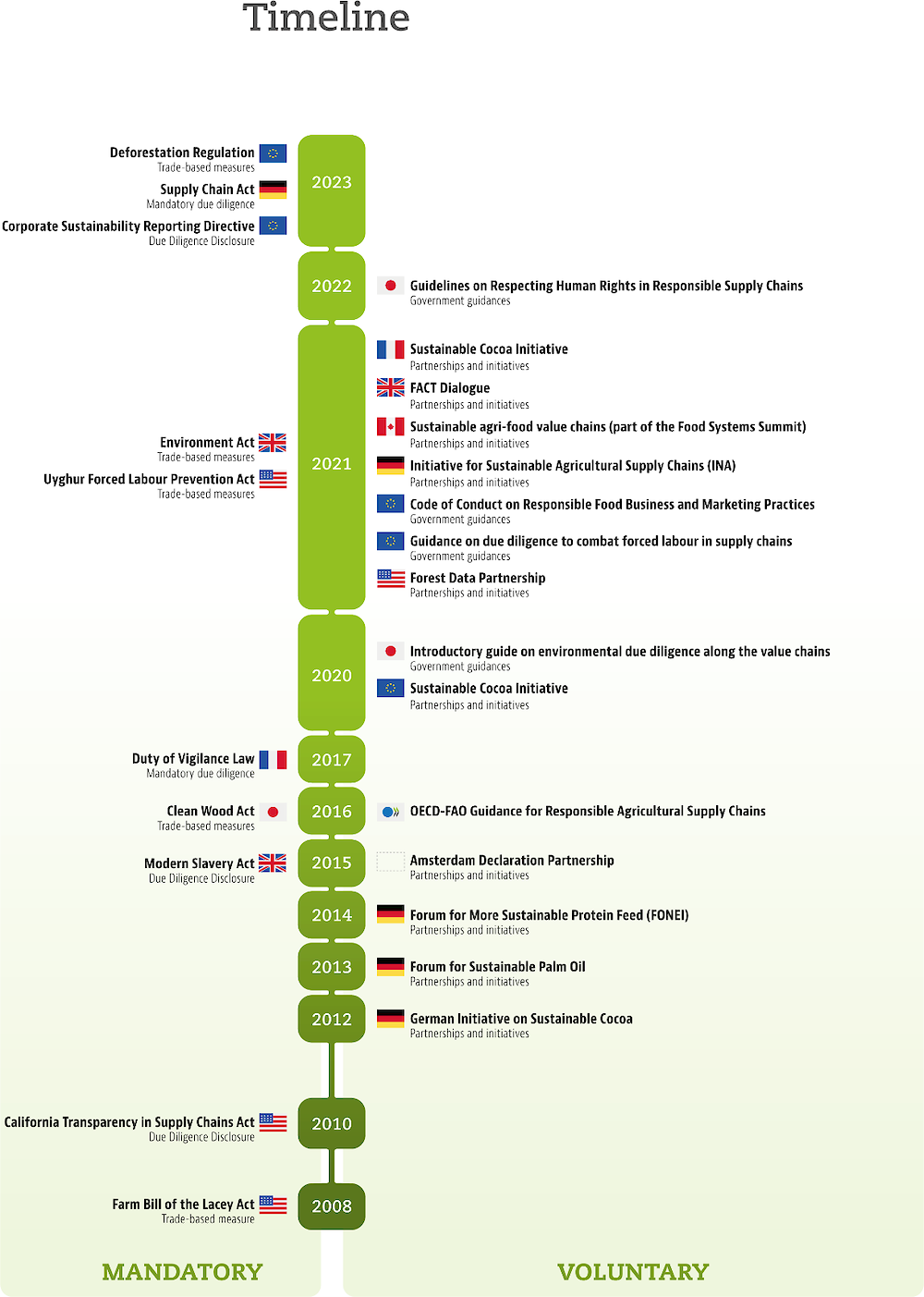

The selective inventory in Annex A identifies 24 mandatory and voluntary measures relating to due diligence for sustainable agricultural supply chains (food and non-food commodities e.g., palm oil, soy, cocoa, rubber, fibre leather). Among these:

Ten (42%) are mandatory measures, of which three are corporate due diligence disclosure measures, five are trade-based measures and two are mandatory due diligence laws.

Fourteen (58%) are voluntary measures: four are government guidances and ten are government-led partnerships and initiatives.

While promoting responsible agricultural supply chains is not a new concern for G7 policy makers, the past three years have seen a sharp increase in the number of measures introduced by G7 governments. 63% of the measures in scope of this paper were introduced in the past three years (15 out of 24). The majority of the trade-based measures, all of the government guidances and 60% of the government-led partnerships and initiatives were introduced in the last three years, with the latter focused on specific commodities and/or risks relevant to agriculture supply chains.

Infographic 3.1. Timeline of measures in scope of the review

Copy link to Infographic 3.1. Timeline of measures in scope of the review

Source: OECD

3.1. Comparative review of the scope of the identified policy measures

Copy link to 3.1. Comparative review of the scope of the identified policy measures3.1.1. RBC risk scope

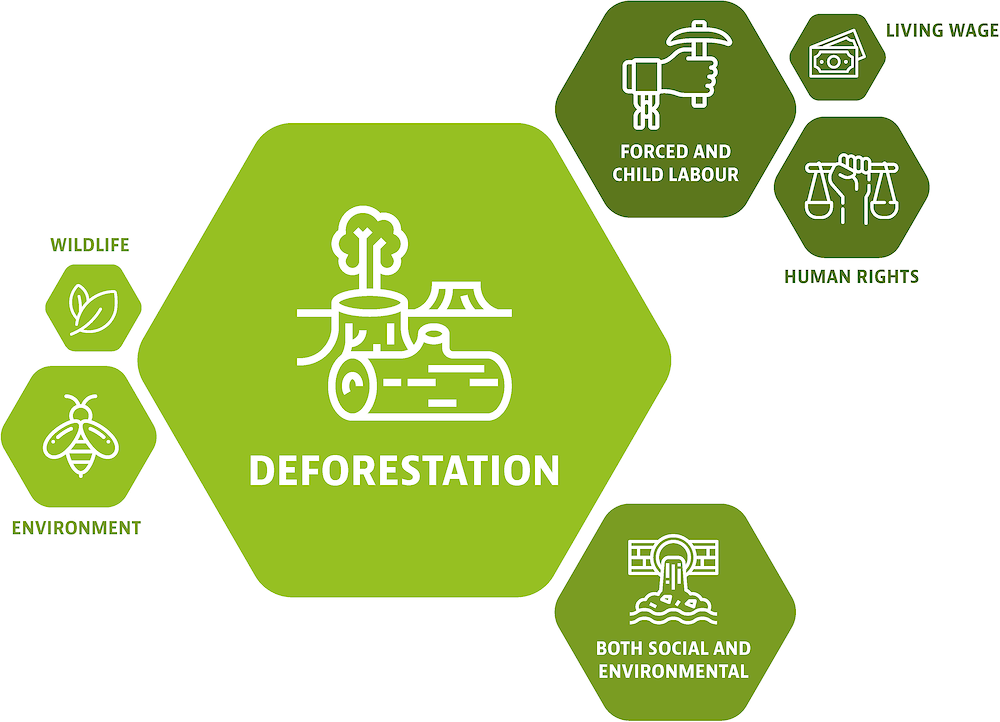

Copy link to 3.1.1. RBC risk scopeAll measures in the selective inventory aim to ensure that companies address sustainability or RBC risks or impacts1 that can occur in their operations and along their supply chains. The measures vary in whether they take a general or narrow approach to the risks or impacts that they aim to tackle. Seven of the measures (29%) take a cross-cutting approach that addresses a broad range of sustainability risks while the vast majority of measures (17 out of the 24 (71%)) take a more targeted approach, identifying a specific risk.

All trade-based measures focus on a specific type of RBC risk (e.g., deforestation, forced labour, illegal tracking of wildlife).2

Two out of three corporate due diligence disclosure measures focus on a specific risk (i.e., forced labour in the UK Modern Slavery Act and California Transparency in Supply Chains Act) while the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive covers a broad range of environmental, social and governance risks.

The vast majority of voluntary measures in scope also focus on one or more specified risks (i.e., 75% of the government guidances and all of the government-led partnerships and initiatives).

For measures identified that target specific risks, there seems to be broad convergence around which issues governments consider to be most salient, with the majority of those measures addressing risks related to deforestation3 and forced labour.4

Infographic 3.2. Key RBC risks and their prevalence in the identified policy measures

Copy link to Infographic 3.2. Key RBC risks and their prevalence in the identified policy measures

Source: OECD

Table 3.1 below sets out examples of how some of the relevant risk-specific policy measures define key risks, such as deforestation, forest degradation and forced labour.

Table 3.1. Examples of definitions of risks in identified policy measures

Copy link to Table 3.1. Examples of definitions of risks in identified policy measures|

Measures |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

EU Deforestation Regulation |

Forest: Draws on the FAO (2020[38]) definition - land spanning more than 0.5 hectares with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover of more than 10%, or trees able to reach those thresholds in situ, excluding land that is predominantly under agricultural or urban land use (Art. 2). Deforestation: the conversion of forest to agricultural use, whether human induced or not. (Art. 2). As such, the EU Deforestation Regulation deviates from the definition of deforestation as established by the FAO (2020[38]), which defines deforestation as the “conversion of forest to other land use”, thus including the conversion of forest for non-agricultural purposes such as urban development or infrastructure. Forest degradation: structural changes to forest cover, taking the form of the conversion of: (a) primary forests or naturally regenerating forests into plantation forests or into other wooded land; or (b) primary forests into planted forests (Art. 2). |

|

UK Environment Act |

Forest: an area of land of more than 0.5 hectares with a tree canopy cover of at least 10% (excluding trees planted for the purpose of producing timber or other commodities). This draws on the FAO’s definition of forest and includes land that is wholly or partly submerged in water (whether temporarily or permanently) (Schedule 17). Forest risk commodity: to be specified in regulations made by the Secretary of State. The regulations may only specify a commodity that has been produced from a plant, animal, or other living organism and where the Secretary of State considers that forest (as per definition above) is being or may be converted to agricultural use for the purposes of it producing the commodity (Schedule 17). Once a commodity has been introduced under the regulations, due diligence requirements will apply to all regulated businesses using that commodity or products derived from it regardless of where it has been grown, whether in forest areas or other ecosystems. |

|

Japan Clean Wood Act |

Legally harvested wood and wood products: wood from trees harvested in compliance with the laws and regulations of Japan or the country of harvest (Art. 2) |

|

European Commission External Action Service Guidance on Due Diligence to combat Forced Labour |

Forced labour: defined in line with the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 29 on Forced or Compulsory Labour as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily” (page 2). |

|

UK Modern Slavery Act |

Forced labour: defined in line with Article 4 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms agreed by the Council of Europe (1950), which states that “forced or compulsory labour shall not include: (a) any work required to be done in the ordinary course of detention imposed […] or during conditional release from such detention; (b) any service of a military character or, in case of conscientious objectors in countries where they are recognised, service exacted instead of compulsory military service; (c) any service exacted in case of an emergency or calamity threatening the life or well-being of the community; (d) any work or service which forms part of normal civic obligations.” |

|

US Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act |

Forced labour has the meaning given in section 1307 of the US Tariff Act of 1930 (19 USC. 1307) as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under menace of any penalty for its non-performance and for which the worker does not offer himself voluntarily,” including forced child labour (section 7, para. (1)A). |

Source: OECD

6 of the 24 measures (25%) take a broader and more holistic approach to addressing RBC risks, by requiring or expecting companies to address a range of RBC issues, including human rights, social, governance and/or environmental impacts. However, even within these broader measures, policy makers have taken different approaches to scoping and defining particular risks or impacts. For example:

The French Duty of Vigilance focuses on human rights and fundamental freedoms, the health and safety of individuals and the environment.

The German Supply Chain Act focuses on human rights, labour rights, health and safety, and a specific set of environmental risks. The Act takes a prescriptive approach — for example, by defining environmental risks against a list of prohibitions relating primarily to the use of chemicals5 (i.e., mercury) and through a human rights lens (i.e., rights to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health).6

The EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive focuses on a broader set of sustainability risks and impacts, with the first draft of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) covering sustainability matters related to environment, social and governance.7

Overall, there has been limited integration of climate risks and impacts (e.g., relating to greenhouse gas emissions) in the policy measures identified. Broader environmental risks and impacts are covered in both mandatory due diligence measures, though they differ significantly in how prescriptive they are in defining environmental adverse impacts. Climate-related disclosure rules, including on scope 3 emissions, are, however, part of the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

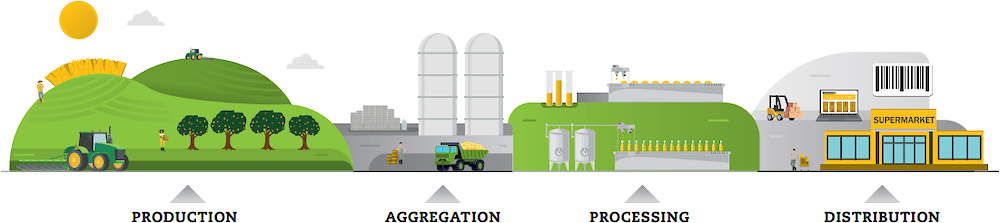

3.1.2. Supply chain scope

Copy link to 3.1.2. Supply chain scopeWhile all of the identified measures aim to address risks beyond companies’ own operations, they take different approaches when applying due diligence requirements to the supply chain and other business relationships8 – including the extent to which they expect covered entities to focus on specific points or tiers in the supply chain (e.g., direct suppliers), or to consider impacts associated with a wider group of entities in the supply and/or value chain. The measures also differ in level of detail, with many leaving terms like “supply chain” or “supplier” undefined.

Infographic 3.3. Simplified agriculture supply chain

Copy link to Infographic 3.3. Simplified agriculture supply chain

Source: OECD

Six measures have a broad supply chain approach, i.e., they expect companies to consider the supply chain from production and harvesting to sale, however they do not all define the supply chain’s scope. It is also not always clear whether measures focused on the supply chain also apply due diligence or other risk management expectations to the full lifecycle of a product or project, and to downstream as well as upstream entities (i.e., to buyers, distributors or other business relationships that receive or use products or services from the company). Other measures explicitly address both upstream and downstream (e.g., Japan’s Guidelines on Respecting Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains).

Some measures are broader still and apply due diligence expectations explicitly to the full “value chain” (e.g., the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and Japan’s Introductory Guide on Environmental Due Diligence along the Value Chains). However, these measures do not always define the term.

Table 3.2. Examples of supply chain scope in identified policy measures

Copy link to Table 3.2. Examples of supply chain scope in identified policy measures|

Measures |

Definitions |

|---|---|

|

German Supply Chain Act |

Defines the supply chain as referring to “all products and services of an enterprise. It includes all steps in Germany and abroad that are necessary to produce the products and provide the services, starting from the extraction of the raw materials to the delivery to the end consumers”. However, due diligence expectations vary depending on whether suppliers are direct or indirect. |

|

EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

Expects reporting to cover information about the undertaking’s own operations and “value chain, including, its products and services, its business relationships and its supply chain” The concept of value chain is further defined in the European Sustainability Reporting Standards. |

|

UK Modern Slavery Act |

Requires any commercial organisation within the scope of the act to prepare a slavery and human trafficking statement for each financial year covering “any of its supply chains” and “any part of its business” (MSAs. 54(4)(a)(i)), leaving open the extent to which organizations’ upstream activities are covered. The statutory guidance issued under section 54(9) further defines supply chains as having “everyday meaning” (UK Secretary of State, 2017) without, however, offering a specific definition of supply chains per se. |

|

Japan’s Guidelines on Respecting Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains |

States that “[t]he term “supply chain” as used in the Guidelines refers to “upstream” in relation to the procurement and securing, etc. of raw materials and resources for a business enterprise’s products and services, facilities, and software, and also “downstream” in relation to the sale, consumption, and disposal etc. of its products and services. In addition, the term “other business partners” refers to business enterprises other than those within the supply chain that are related to the business enterprise’s operations, products, and services. More specifically, for example, these are investment and lending locations, partners of joint enterprises, business operators providing equipment maintenance and inspection, and business operators providing security services, etc.” |

|

Japan’s Introductory Guide on Environmental Due Diligence along Value Chains |

Defines value chain as a series of economic entities or economic actions in all processes from creation to consumption of added value related to a company’s business activities. It includes a series of actions and entities related to business activities, such as mining, procurement, production, sales, transportation, use, and disposal of raw materials. This includes upstream and downstream and indirect and direct business relationships, as well as the behaviour of consumers who use the company’s products and services. |

|

EU External Action Service Guidance on Due Diligence to combat Forced Labour in Supply Chains |

Refers to “all levels of the supply chain” but does not define further. |

|

California Transparency in Supply Chain Act |

Expects companies to obtain from direct suppliers a certificate that “materials incorporated into the product comply with the laws regarding slavery and human trafficking of the country or countries in which they are doing business.” |

|

French Duty of Vigilance Law |

Expects companies’ due diligence to cover “activities of subcontractors and suppliers with whom the company has an established business relationship.” To date this has been interpreted in an inclusive, rather than exclusive way and as going beyond direct business relationships. |

|

EU Deforestation Regulation |

Expectations apply in relation to the “supply chain” but the term is not defined further. However, the Regulation does clarify the roles and expectations for supply chain actors. Article 2: Definitions (15) ‘operator’ means any natural or legal person who, in the course of a commercial activity, places relevant products on the market or exports them; (16) ‘placing on the market’ means the first making available of a relevant commodity or relevant product on the Union market; (17) ‘trader’ means any person in the supply chain other than the operator who, in the course of a commercial activity, makes relevant products available on the market; (18) ‘making available on the market’ means any supply of a relevant product for distribution, consumption or use on the Union market in the course of a commercial activity, whether in return for payment or free of charge; (19) ‘in the course of a commercial activity’ means for the purpose of processing, for distribution to commercial or non-commercial consumers, or for use in the business of the operator or trader itself. |

|

US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act |

Expectations apply in relation to the “supply chain” but the term is not defined further (although to some degree inferred by the geographic focus i.e., nexus in Xinjiang). |

|

Japan Clean Wood Act |

Applies expectations to companies’ “domestic supply chain” which includes “timber importers, producers, processors, and distributors (including exporters)” (Forest Trends, 2020[39]). Retailers were included by the amendment made in May 2023 (Japanese Law Translation, n.d.[40]). |

|

Lacey Act |

The term supply chain is not used or defined. |

|

UK Environment Act |

Expects regulated persons who use forest risk commodities (or products derived from them) in their UK commercial activities to report on their due diligence system but does not use the term “supply chain”. |

Source: OECD

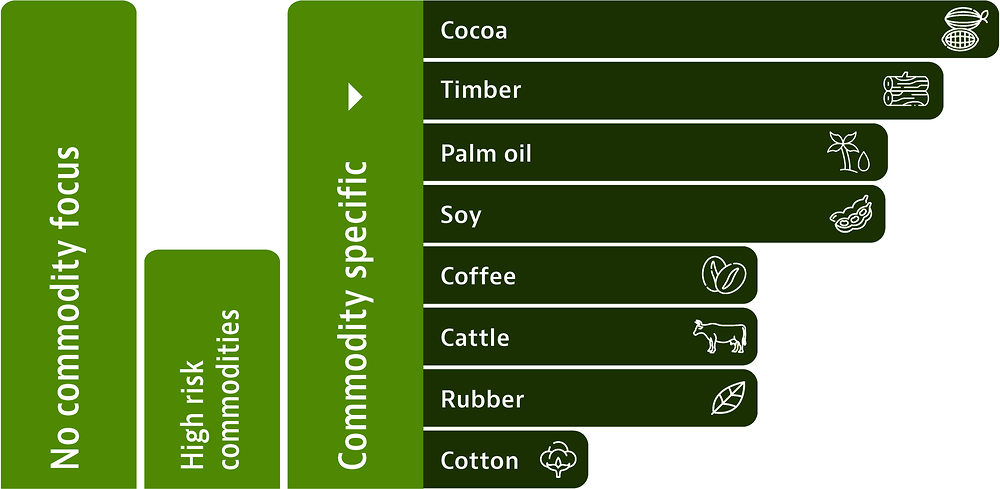

3.1.3. Commodity scope

Copy link to 3.1.3. Commodity scopeOf the mandatory and voluntary measures in scope of the selective inventory, 14 of 24 (58%) focus on specific commodities, which may include products derived from specified commodities (all the trade-based measures and government-led partnerships and initiatives).9 Trade-based measures tend to be more selective in commodity scope than mandatory due diligence or disclosure measures. The corporate due diligence disclosure measures, due diligence measures and government guidelines in scope of this paper are broader and do not tend to focus on specific commodities per se.10

Infographic 3.4. Commodities in scope of the measures

Copy link to Infographic 3.4. Commodities in scope of the measures

Source: OECD

For the fourteen measures that specify a focus on one (or more commodities), three out of five trade-based measures target a commodity (or commodities) related to deforestation or timber production.11 The way these measures target specific commodities differs: measures can focus on a specific commodity directly or focus on specific risk and determine a list of commodities that are targeted specifically to address that risk. Annex A provides the full list of commodities targeted by each measure.

3.1.4. Geographic scope

Copy link to 3.1.4. Geographic scopeMost of the policy measures have no direct geographic focus – though in some cases this may be indirectly inferred, for examples where measures target specific commodities or risks. The US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act is the only measure with an explicit geographic focus. However, a number of measures introduce country-specific elements in other ways. For example:

In the Japan Clean Wood Act, the Forestry Agency of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries has created country-specific pages that outline countries’ policies on legal forest harvest in order to assist companies with their risk-based prioritization.

Under the EU Deforestation Regulation, the EU Commission establishes a country benchmarking system consisting of a three-tier classification system (high-risk, low-risk and standard risk) applied to all countries, including EU Member States (see Article 29 of the Regulation).

3.1.5. Entity scope

Copy link to 3.1.5. Entity scopeThe policy measures also take different approaches to defining the entities in scope of the law. The corporate due diligence disclosure and mandatory due diligence measures included in the selective inventory target large MNEs and, in the case of the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, listed SMEs. Trade-based measures have wider scope, in some cases apply to any business entities–-including SMEs—or any natural or legal person that carries out activities covered by the law (e.g., UK Environment Act12 and US Lacey Act apply to legal and natural persons).

For the mandatory due diligence and corporate due diligence disclosure measures, different thresholds are applied to determine whether an entity is in scope. For large companies, measures apply thresholds such as a minimum number of employees or annual turnover/revenue, in addition to an enterprise “doing business in” the relevant country or region.

Table 3.3. Examples of criteria for determining entities in scope

Copy link to Table 3.3. Examples of criteria for determining entities in scope|

Measures |

Domiciliation |

Turnover |

Employee threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

|

UK Modern Slavery Act |

If the entity carries on business in any part of the UK. |

An annual turnover above GBP 36 million wherever incorporated or formed |

|

|

California Transparency in Supply Chains Act |

If the entity is doing business in the state of California |

An annual worldwide gross receipts in excess of USD 100 million. |

|

|

French Duty of Vigilance Law |

Headquartered in France |

5 000 employees in the company's direct or indirect French-based subsidiaries and with more than 10 000 employees if including direct and indirect subsidiaries globally. |

|

|

German Supply Chain Act |

Principal place of business in Germany |

From Jan 2023: at least 3 000 employees in Germany, including those posted abroad. From 2024: more than 1 000 employees per average per fiscal year. |

|

|

EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (Should exceed at least two of the following criteria) |

All EU listed companies (listed SMEs being covered as of 2026). |

Net turnover of EUR 40 million; balance sheet total of EUR 20 million |

250 employees on average over the financial year. |

Source: OECD

3.2. A comparison of risk-based due diligence and enforcement in mandatory measures

Copy link to 3.2. A comparison of risk-based due diligence and enforcement in mandatory measuresThis section considers examples of different approaches to integrating due diligence in the mandatory measures13 in scope of the selective inventory, using the OECD RBC due diligence framework as a reference point.14 It does not set out a comprehensive analysis of how the mandatory measures integrate or align with key due diligence principles or the six-step due diligence framework, but rather uses examples to highlight consistencies and inconsistencies between the measures:

Differences in nature and purpose of mandatory measures.

Approaches to two key “characteristics” of due diligence: the risk-based approach and stakeholder engagement.

Public reporting expectations on due diligence.

Approaches to enforcement.

The voluntary measures identified are outside the scope of the analysis on the basis that they do not set out due diligence conduct or disclosure requirements for companies or establish enforcement mechanisms. However, it is notable that all four of the Government guidances explicitly reference OECD standards on RBC. The EU Code of Conduct on Responsible Food Business and Marketing Practices (2021) sets out broader aspirational objectives and targets, with less of a focus on the RBC due diligence Guidance but references the OECD-FAO Guidance.

3.2.1. Differences in nature and purpose of mandatory measures

Copy link to 3.2.1. Differences in nature and purpose of mandatory measuresThe mandatory measures identified take different approaches to due diligence in part because of their core underlying nature and purpose (i.e., corporate due diligence disclosure, conduct-based or trade-based measure). Each category of measure has slightly different aims in how they seek to change company behaviour and incentivise more responsible conduct. For example, and as explained in Section 2

Mandatory due diligence measures establish a direct obligation for companies to conduct specific due diligence obligations based on a pre-determined framework and sanction those companies for non-compliance with those obligations.

Corporate due diligence disclosure measures aim to enhance transparency and incentivise changes in behaviour by requiring companies to disclose information about the steps taken in relation to their due diligence.

Trade-based measures expect companies to demonstrate to authorities’ adequate due diligence processes and/or a specific level of risk in connection with a particular product or supply chain.

Numerous other factors influence the approach of mandatory measures to due diligence, including the level of detail included on the due diligence process, on the information that companies should publicly disclose, and on what constitutes an “appropriate” or “effective” prevention, mitigation or remediation measure. For example, sector-specific or issue-specific legislation tends to result in more specificity on due diligence expectations than horizontal legislation with broader sectoral, risk and geographic coverage.

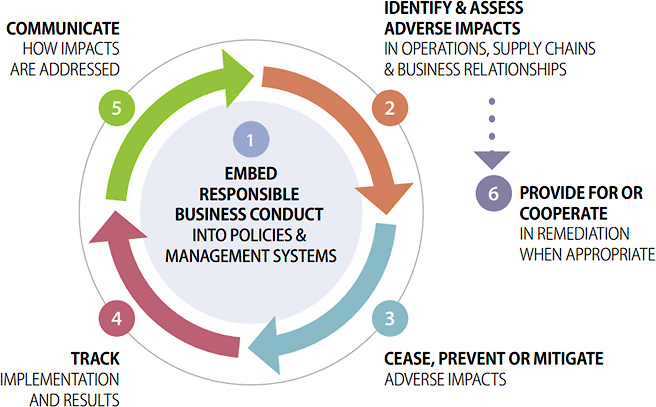

Box 3.1. The OECD Due Diligence framework

Copy link to Box 3.1. The OECD Due Diligence frameworkThe OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (the Guidelines) are recommendations from Governments to multinational enterprises on how to act responsibly and enhance their contribution to sustainable development. In 2023 the Guidelines were updated to better reflect current challenges and objectives. The OECD has developed a range of instruments providing further guidance on due diligence for specific sectors and risks issues, as well as at the cross-sectoral level through the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

The OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains was launched in 2016 following a two-year multi-stakeholder consultative process led by the OECD and FAO Secretariats. The OECD-FAO Guidance provides a common framework and globally applicable benchmark to help enterprises operating along agricultural supply chains to identify and mitigate adverse impacts and contribute to sustainable development. In addition, the OECD has developed Handbooks for business to help companies embed specific considerations on RBC risks such as deforestation, child labour and forced labour, into their corporate due diligence procedures.

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBC seeks to promote a common understanding among governments and stakeholders on due diligence for responsible business conduct. The OECD MNE Guidelines and Due Diligence Guidance for RBC are aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy.

Figure 3.1. RBC due diligence framework

Copy link to Figure 3.1. RBC due diligence frameworkAlthough the due diligence process is described in step-by-step fashion, in practice the process of due diligence is ongoing, iterative and dynamic, as several steps may be carried out simultaneously with ongoing feedback loops.

3.2.2. Approaches to two key characteristics of due diligence: the risk-based approach and stakeholder engagement

Copy link to 3.2.2. Approaches to two key characteristics of due diligence: the risk-based approach and stakeholder engagementThe OECD Guidelines and RBC due diligence guidance sets out key principles or “characteristics” of due diligence as well as a six-step due diligence framework, elaborated further in the RBC Due Diligence Guidance and the sectoral due diligence guidances. A comprehensive review of the policy measures against all characteristics and the six-step framework is beyond the scope of this report; this section instead focuses on two key characteristics in order to demonstrate some commonalities and differences in how the policy measures approach due diligence.

How do the mandatory measures identified integrate the risk-based approach?

Copy link to How do the mandatory measures identified integrate the risk-based approach?Under the RBC due diligence guidance, multinational enterprises throughout the supply chain are expected to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address actual and potential adverse impacts to people, society and the planet. As it will often not be possible for enterprises to identify or respond to all risks and impacts related to their activities and business relationships simultaneously and with the same degree of effort, enterprises are encouraged to prioritise their most significant risks and impacts first. They are also expected to tailor their due diligence to the nature, severity and likelihood of the risk and impacts they face in practice (see Box 3.2).

The extent to which mandatory measures integrate risk-based principles and expectations set out in the Due Diligence Guidance for RBC depends on numerous factors, as mentioned above. These include the issue and/or sector focus of the measure. Measures with a restrictive scope of risk in effect predetermine and prioritise specific RBC issues over others for companies; they also tailor due diligence requirements to the specific risk(s) in scope of the measure (e.g., deforestation). In these cases, measures may not incorporate additional risk-based requirements for enterprises in line with OECD RBC guidance.

Box 3.2. The risk-based approach under the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on RBC and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBC

Copy link to Box 3.2. The risk-based approach under the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on RBC and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBCThe OECD MNE Guidelines state that: “The nature and extent of due diligence, such as the specific steps to be taken, appropriate to a particular situation will be affected by factors such as the context of an enterprise’s operations, the specific recommendations in the Guidelines, and should be proportionate to the size of the enterprise, its involvement with an adverse impact and the severity of adverse impacts. In this respect, the measures that an enterprise takes to conduct due diligence should be risk-based, commensurate to the severity and likelihood of the adverse impact and appropriate and proportionate to its context. Where it is not feasible to address all identified impacts at once, an enterprise should prioritise the order in which it takes action based on the severity and likelihood of the adverse impact” (MNE Guidelines, 2023, Chapter II, Commentary, para. 19).

The risk-based approach is further elaborated in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBC and encompasses two “key characteristics” of due diligence under OECD RBC standards. It is an essential part of ensuring that:

Enterprises prioritise the order in which they take action based on the severity1 and likelihood of the adverse impact and, on that basis, focus their due diligence on their higher-risk operations and business relationships.

The measures an enterprise takes are commensurate to the severity and likelihood of the adverse impact and adapted to the nature of the adverse impact, which involves tailoring approaches for specific risks and taking into account how these risks affect different groups.

Once the most significant impacts are identified and dealt with, the enterprise should move on to address less significant impacts. The process of prioritisation is also ongoing, and in some instances new or emerging adverse impacts may arise and be prioritised before moving on to less significant impacts (OECD, 2022[42]).

1. Severity is not an absolute concept and is context specific; where the risk of a potential impact is most likely and most severe will be specific to the enterprise, its sector and the nature of its business relationships. Severity is determined according to three factors: Scale or the gravity or seriousness of the potential or actual impact, such as the degree of serious impact on workers’ health and safety, degree of waste or chemical generation; or loss of life or severe bodily harm caused; Scope or the reach or extent of the potential or actual impact, for example the number of individuals that are or will be affected, or the extent of environmental damage or other environmental impact; and Irremediable character or its irreversible nature, or any limits on the ability to restore the individuals or environment affected to a situation equivalent to their situation before the adverse impact.

For example, the US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act and the EU Deforestation Regulation pre-determine high-risk factors for companies (e.g., geographies, business entities and commodities) and ask them to focus on a specific risk. They do not include additional expectations for companies to prioritise and tailor their due diligence according to the nature, severity and/or likelihood of risk. However, the EU Deforestation Regulation includes a separate country benchmarking system intended to guide companies’ risk management.15

Other measures do integrate risk-based elements and principles into the due diligence expectations, but with varying degrees of specificity and consistency with international standards. For example, measures vary in the degree to which they list severity and likelihood as criteria to inform due diligence and prioritisation decisions. Some corporate due diligence disclosure and mandatory due diligence measures explicitly list severity and/or probability as factors to take into account in prioritisation decisions, either in the text of the law or in statutory guidance (e.g., UK Modern Slavery Act, German Supply Chain Act, French Duty of Vigilance Law) but they tend to vary in level of detail and do not always define severity. Other measures rely on broader concepts of “appropriateness” or “materiality” and are less specific about how companies should prioritise.

Importantly, the identified measures also take different approaches to the role of influence or leverage over a supplier or other business partner in the due diligence process. Under the OECD Due Diligence Guidance on RBC and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the degree of leverage or influence an enterprise has over a business partner is relevant to how it responds to an identified risk or impact but is not relevant to prioritisation decisions. However, some measures lack clarity on the role of influence or leverage; others require due diligence on longer-term or “established” business partners or only in relation to direct or Tier 1 suppliers (OECD, 2022[42]).

How do the mandatory measures identified reflect stakeholder engagement?

Copy link to How do the mandatory measures identified reflect stakeholder engagement?Box 3.3. Stakeholder engagement under the OECD Due Diligence Guidance on RBC

Copy link to Box 3.3. Stakeholder engagement under the OECD Due Diligence Guidance on RBCStakeholder engagement is a core element of a risk-based due diligence process under OECD RBC due diligence guidance. Under the MNE Guidelines, enterprises are expected to engage meaningfully with relevant stakeholders or their legitimate representatives as part of carrying out due diligence and in order to provide opportunities for their views to be taken into account with respect to activities that may significantly impact them related to matters covered by the MNE Guidelines (Chapter II, para. 15). Relevant stakeholders are persons or groups, or their legitimate representatives, who have rights or interests related to the matters covered by the Guidelines that are or could be affected by adverse impacts associated with the enterprise’s operations, products or services (Commentary to Chapter II, para. 28).

Stakeholder engagement is characterised by two-way, good faith communication and involves the timely sharing of the relevant information needed for stakeholders to make informed decisions in a format that they can understand and access. Meaningful engagement with relevant stakeholders is important throughout the due diligence process. In particular, when the enterprise may cause or contribute to, or has caused or contributed to an adverse impact, engagement with impacted or potentially impacted stakeholders and rightsholders will be important.

Source: (OECD, 2018[41]) (OECD, 2023[43])

Both of the mandatory due diligence measures have direct stakeholder engagement expectations embedded as core requirements, though with differences in emphasis and level of detail:

The French Duty of Vigilance Law requires the vigilance plan to be “drawn up in conjunction with stakeholders of the company, including as part of multi-stakeholder initiatives within sectors or at local level” and further mandates to establish a grievance mechanism “in consultation with the representative trade union organisations within the company”. However, it does not require engagement with relevant stakeholders more broadly during the due diligence process and does not define “stakeholders”.

The German Supply Chain Act requires companies, in establishing and implementing their risk management system, to “give due consideration to the interests of its employees, employees within its supply chains and those who may otherwise be directly affected in a protected legal position by the economic activities of the enterprise or by the economic activities of an enterprise in its supply chains”.

The corporate reporting and trade-based measures tend to include limited detail on stakeholder engagement expectations, though stakeholder engagement is sometimes addressed in accompanying guidance. Stakeholders also do not tend to be defined. The EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive requires companies to report information on "how the undertaking’s business model and strategy take account of the interests of the undertaking’s stakeholders and of the impacts of the undertaking on sustainability matters" (Art. 19(2)a, f & 29(2)a, f). Further detail on stakeholder engagement is expected in the EU’s future European Sustainability Reporting Standards. The US Customs and Border Protection guidance note to the US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act that “due diligence system information used to overcome rebuttable presumption may include engagement with suppliers and other stakeholders to assess and address forced labor risk” (US Homeland Security, 2022[44]).

3.2.3. Public reporting expectations on due diligence

Copy link to 3.2.3. Public reporting expectations on due diligenceOECD Due Diligence Guidance on RBC recommends that companies communicate externally relevant information on due diligence policies, processes and activities conducted to identify and address actual or potential adverse impacts, including the findings and outcomes of those activities. The Due Diligence Guidance for RBC and sectoral due diligence guidances provide additional detail.

Publication and disclosure of due diligence processes is the most common feature shared by mandatory measures, with eight out of ten (80%) measures mandating businesses to report publicly on their due diligence measures. However, the format and information contained vary significantly between measures.

While penalties related to a business’s failure to disclose are part of ensuring businesses meet expectations, mandatory reporting is also intended to enable civil society and market decision makers such as consumers, business to business and government to business buyers and investors to make decisions on their purchasing or investing based on those disclosures, and thereby exerting pressure to deliver improvements.

The two mandatory due diligence laws provide relatively detailed descriptions of what information companies should report on (see Table A B.1 in Annex B). The three corporate due diligence disclosure measures also provide a detailed and granular level of description of what elements of the due diligence processes companies are expected to report on.

While conducting due diligence is not directly mandated in trade-based measures, providing a ‘due diligence report’ is often required to demonstrate compliance or rebut a presumption that a product has been made by generating a specific risk. The UK Environment Act, the EU Deforestation Regulation and the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act provide (or will provide, pending secondary legislation) information as to what due diligence should or could look like either through the text of the law, through secondary legislation or accompanying Guidance.

Other trade-based measures are less specific about what due diligence information should be reported on and do not mandate any public reporting. For example:

The US Lacey Act does not refer to due diligence, but rather prohibits the trade of wildlife, fish and plants where the importer in the exercise of “due care”16 should have known that the goods were illegally taken, possessed, transported or sold. The Act does not define or mandate what due care constitutes in practice.17

Although an additional Guideline was published in 2023 which includes information about how to conduct due diligence and check lists for due diligence, under the Japan Clean Wood Act, it is left up to the company’s discretion with regard to how they check the legality of wood products in accordance with the act. In addition, the Japanese Forestry Agency has designed an accompanying guidance, the Clean Wood Navi, to aid companies in meeting the requirements under the Act. This Clean Wood Navi is a web portal that “contains information on the relevant laws and regulations for each producer country, as well as examples of certificates and permits for each” (Forest Trends, 2020[39]).

3.2.4. Approaches to enforcement

Copy link to 3.2.4. Approaches to enforcementThis section considers only the mandatory measures identified, which vary substantially in how they approach enforcement, both in terms of (a) which authorities are responsible for enforcement and (b) the regime for sanctioning and holding companies liable for non-compliance.

In terms of which authorities are responsible for enforcement:

Trade-based measures are generally enforced by custom and borders agencies, with authorities able to seize goods that do not meet the law’s requirements e.g., the US Customs and Border Protection is the primary authority responsible for enforcement under the US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. (CBP, 2020[45]). On a yearly basis, the US Customs and Border Protection provides metrics on the number of shipments seized and their value. For example, in 2022, a total of 262 agricultural product shipments were seized of an amount of USD 16 million (CDP, 2023[46]).

The two mandatory due diligence measures differ in approach. The German Supply Chain Act allocates new powers to an existing administrative agency (i.e., the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control) to enforce its provisions while in France, the Duty of Vigilance Law has no associated enforcement authority and can be enforced through civil court decisions.

The corporate due diligence disclosure measures also take different approaches. Under the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act, the Attorney General has exclusive authority to enforce the Act and may file a civil action for injunctive relief.18 Under the UK Modern Slavery Act, the Secretary of State can bring civil proceedings in the High Court for an injunction.19 Finally, nationally competent authorities (likely financial market authorities) will be in charge of supervising enforcement of the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive once transposed into national law.

Enforcement regimes also vary significantly when it comes to penalty and sanction regimes. For example:

Trade-based measures take a variety of different approaches. The EU Deforestation regulation’s penalties range from fines proportionate to the environmental damage, confiscation of revenues gained by the importer and (temporary) prohibitions from exercising the simplified due diligence option offered under the regulation or placing relevant commodities onto the market.20 Through the Lacey Act, illegal trafficking of wildlife can lead to a civil penalty, criminal penalty or a permit sanction. The Japan Clean Wood Act did not have any enforcement mechanism nor foreseen sanctions, except for revocation of the company’s registered status under the “Registered Wood-related Business Entity” until an amendment act was introduced in May 2023, which includes penal provisions for the violation of the act.

The two mandatory due diligence measures differ in important ways, with the French law based on judicial enforcement by competent courts. The court, upon being seized by "any interested person", can order the establishment, disclosure and effective implementation of vigilance measures, including under penalty payment. Judicial enforcement is the sole enforcement mechanism as there is no supervisory authority to monitor enforcement. Under the German Supply Chain Act, enforcement is based exclusively on administrative enforcement. The administrative supervisor can require that companies take concrete action to fulfil their obligations. Administrative fines of up to 2% of annual turnover can be awarded for failure to comply, as well as prohibition for sanctioned companies to receive government contracts.

Corporate due diligence disclosure measures also vary in their penalties. For the UK Modern Slavery Act and the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act, sanctions will be enforced through injunctions – depending on the proceedings undertaken by the High Court or the Attorney General. In the case of the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, specific sanctions will be at the discretion of Member States, which should ensure that there are effective systems of investigations and sanctions to “detect, correct and prevent inadequate execution of the statutory audit and the assurance”.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. RBC risks refer specifically to the risks of adverse impacts with respect to issues covered by the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises — impacts on society (including human rights and labour), governance and the environment.

← 2. The UK Environment Act does have a broad environmental scope but the due diligence component (Schedule 17) only addresses “forest risk commodity”. Under the Schedule, a regulated person must not use a forest risk commodity, or a product derived from a forest risk commodity in their UK commercial activities unless relevant local laws were complied with and must establish and report on a “due diligence system”.

← 3. Ten measures focus on deforestation risk. Four measures have their primary focus on deforestation-risk, i.e., the EU Deforestation Regulation, the Fact Dialogue, the Forest Data Partnership, and the Amsterdam Declaration Partnership. Six measures focus on several specific risks, of which deforestation is one. The UK Environment Act covers environment-related risks, with specific attention for deforestation risk. The Initiative for Sustainable Agricultural Supply Chains focuses on the risks of deforestation and living wage in the agricultural supply chain. The Forum for Sustainable Palm Oil covers deforestation, biodiversity loss and human rights. The French, German, and EU Sustainable Cocoa Initiatives both focus on a broad range of environmental and social issues, including deforestation and forced labour.

← 4. Four measures focus specifically on forced labour/modern slavery and human trafficking, i.e., the UK Modern Slavery Act, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act, the US Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (also known as UFLPA) and EU External Action Service guidance on Due Diligence to combat forced labour in supply chains. The French, German, and EU Sustainable Cocoa Initiatives focus on forced labour together with deforestation, amongst others. The German Forum for More Sustainable Protein Feed focuses on sustainable legume production for feed, sustainable value chains and biodiversity loss.

← 5. Minamata Convention on Mercury of 10 October 2013.

← 6. Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

← 7. Topical standards on Environment include climate change, pollution, water and marine resources, biodiversity and ecosystems and resource use and circular economy. Topical standards on Social are broken up into social standards with regard to company’s own workforce, their workers in the value chain, affected communities and consumers and end-users.

← 8. Note that the OECD Guidelines for MNEs define the term “business relationships” broadly (See Commentary on Chapter II, para. 17): “The term ‘business relationship’ includes relationships with business partners, sub-contractors, franchisees, investee companies, clients, and joint venture partners, entities in the supply chain which supply products or services that contribute to the enterprise’s own operations, products or services or which receive, license, buy or use products or services from the enterprise, and any other non-State or State entities directly linked to its operations, products or services.”

← 9. Government-led partnerships and initiatives all focus on specific commodities, with palm oil, cocoa and soy (all referenced in four times) being the most mentioned commodities amongst the eight measures. Some initiatives focus on one commodity, while others focus on a range of relevant commodities. The Sustainable Cocoa Initiative on cocoa, the Forum on more Sustainable Protein Feed mainly on legumes, including soy, the Forum for Sustainable Palm Oil on palm-oil. The Initiative for Sustainable Agricultural Supply Chains focuses on rubber, soy, palm oil, banana, coffee, cocoa, orange juice, cotton. The Amsterdam Declaration Partnership on cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy, wood, leather as commodities to tackle deforestation-risk. The Fact Dialogue focuses on palm oil, soya, cocoa, beef, and timber. The Forest Data Partnership specifically focuses on forest-risk commodities, being derived from deforestation-risk. The Sustainable Agri-food Value Chains focuses on agri-food.

← 10. Taking into consideration that the agricultural-lens of the study may influence this finding, and that RBC-related regulations and policies may not always have pre-selected commodities by design.

← 11. The UK Environment Act, the EU Deforestation Regulation, and the Japan Clean Wood Act.

← 12. The Forest Risk Commodities Scheme under the UK environment Act is less likely to apply to SMEs because of the definition of “regulated person” (including the requirement to meet conditions in relation to turnover) in para. 7 of Schedule 17. Para. 7 also expressly excludes natural persons (individuals). However, SMEs could be impacted is under Schedule 17, para. 7(1)(b), if the SME is ”a subsidiary of another undertaking which meets [the turnover] conditions”.

← 13. The OECD MNE Guidelines state that: “Where enterprises have large numbers of suppliers, they are encouraged to identify general areas where the risk of adverse impacts is most significant and, based on this risk assessment, prioritise suppliers for due diligence”.

← 14. A comprehensive alignment assessment of whether specific measures align with the international standards is, however, outside the scope of this paper.

← 15. The country benchmarking is based on an assessment which includes the following criteria: a) rate of deforestation and forest degradation b) rate of expansion of agriculture land for relevant commodities c) production trends of relevant commodities and of relevant products and may also take into account additional information as contained in Article 29.4.

← 16. “Due” care is a legal principle that means the degree of care at which a reasonably prudent person would take under the same or similar circumstances. The Lacey Act does not define nor mandate any requirements to constitute due care. U.S. importers have discretion to determine how to best verify the legitimacy of their supply chain going back to where the plant material was taken, and the legality of transactions thereafter, and to abide by plant protection and conservation laws in the U.S. and abroad (USDA, 2023[54]).

← 17. For certain products, a person is required to file an import declaration – a Lacey Act Declaration – upon importation that contains the scientific name of any plant (including the genus and species of the plant) contained in the importation, a description of the value of the importation, the quantity, including the unit of measure, of the plant and the name of the country from which the plant was taken. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) lists the products that require a Lacey Act declaration in the Harmonized Tariff Schedule chapter and continuously evaluates this list (CBP, 2020[45]).

← 18. Injunctive relief, also known as an injunction, is a remedy which restrains a party from doing certain acts or requires a party to act in a certain way.

← 19. See Injunctive relief. It is worth noting that this enforcement measure has never been used in practice.

← 20. Without prejudice to the obligations of Member States under Directive 2008/99/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council.