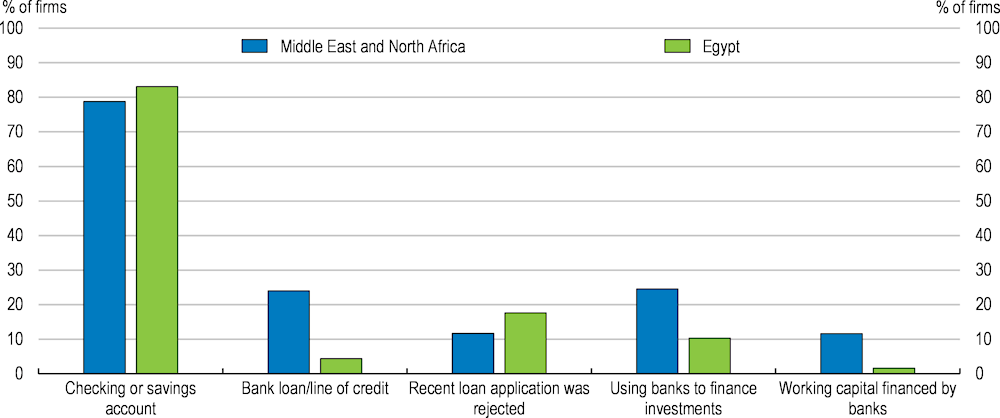

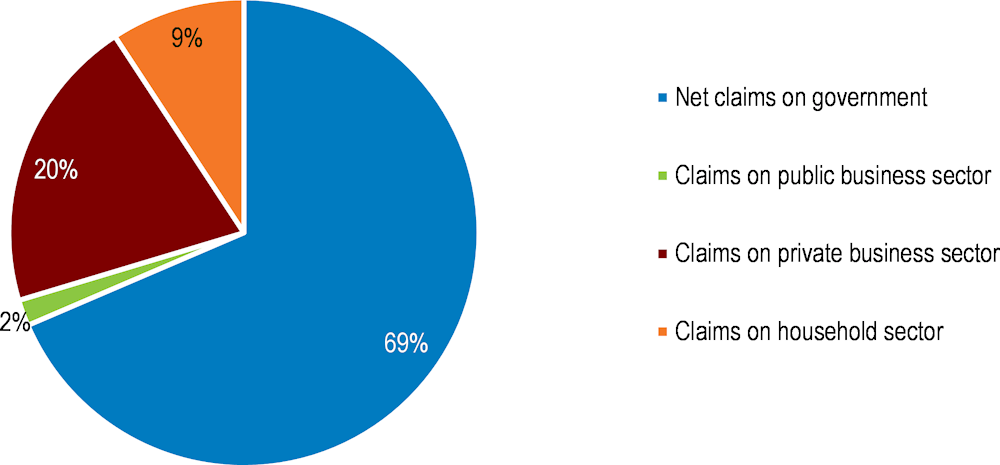

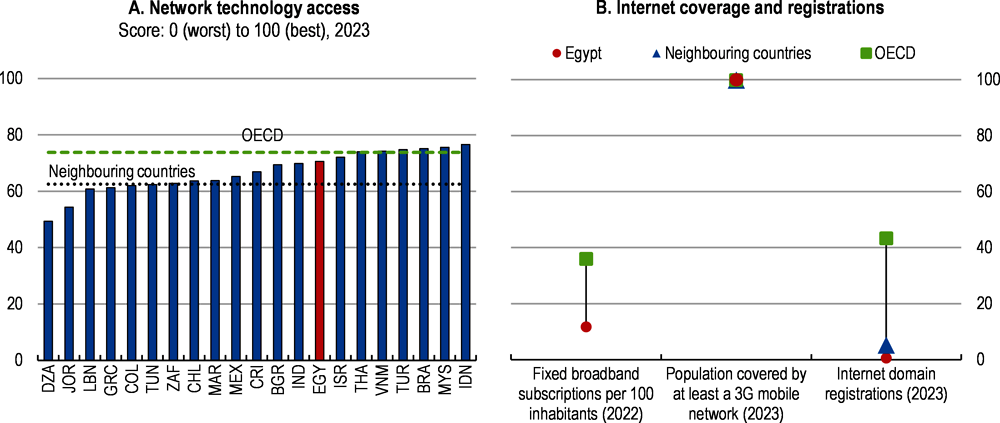

Weak productivity in Egypt is rooted in deep-seated structural causes that impede market competition and prevent a more efficient resource allocation. This implies a number of challenges for economic policy to meet the objectives for long-term sustainable growth as set out in the National Structural Reform Programme, but the government is determined to tackle the issues, and is committed to increase the role of the private sector. Market mechanisms such as business entry and exit, and growth of the most efficient firms, appear to be weaker than in many similar emerging markets. Recent reforms have started to tackle heavy regulatory burdens and barriers that hinder market entry and encourage informality and should be pursued, while the judiciary system still requires improvement. Competition from abroad, and the attraction of foreign direct investment are hampered by tariff and non-tariff barriers, implying that Egypt does not fully benefit from global value-chains and spillovers of technology and knowledge that would help lift productivity. The way state-owned companies are operating across a large number of sectors prevents private businesses from competing on a level playing field, although the government has recently started to take steps to level the playing field for all firms. Moreover, many businesses still face difficulties in accessing finance, as banks overwhelmingly prefer to lend to the government. Enhancing access to finance and improving digitalisation would contribute to a more competitive environment, lifting business sector growth.

OECD Economic Surveys: Egypt 2024

3. Improving the business climate to revive private sector growth

Abstract

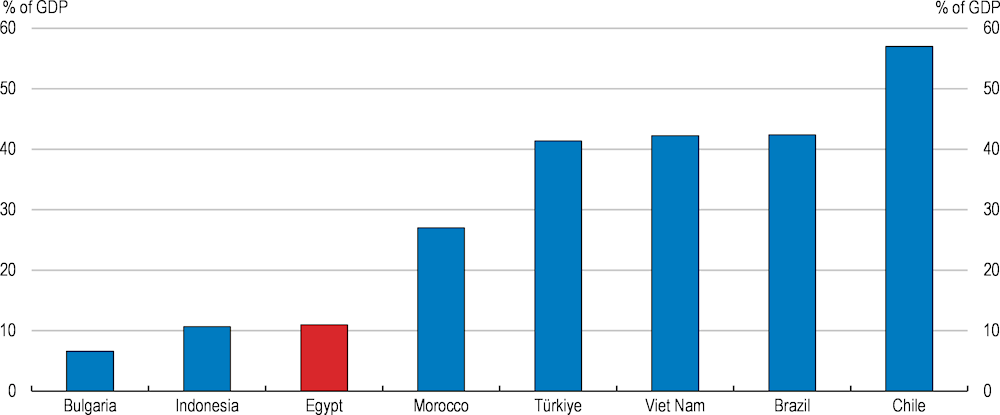

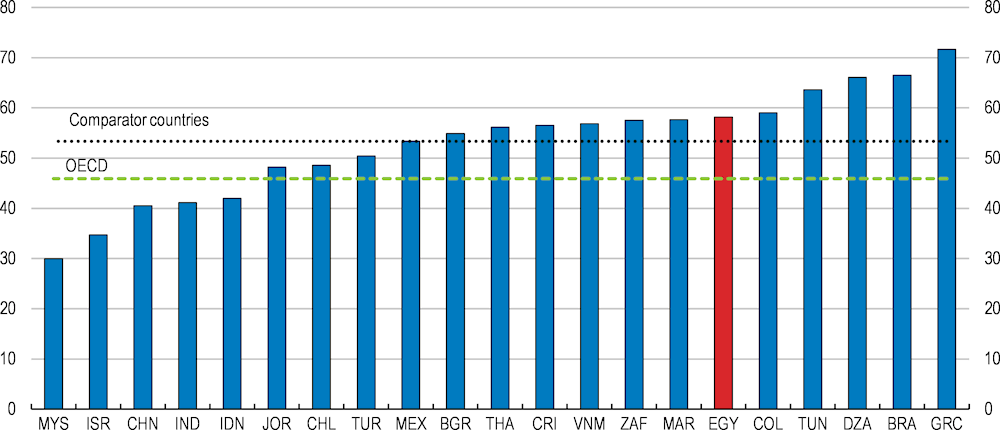

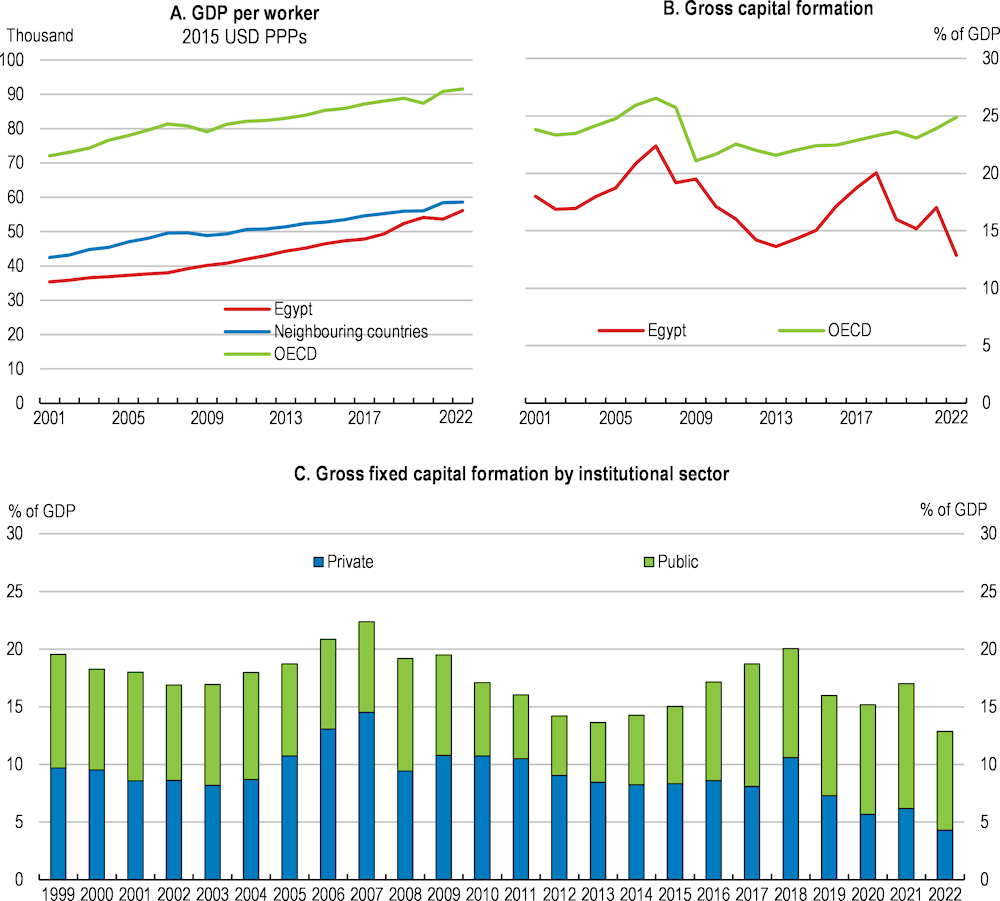

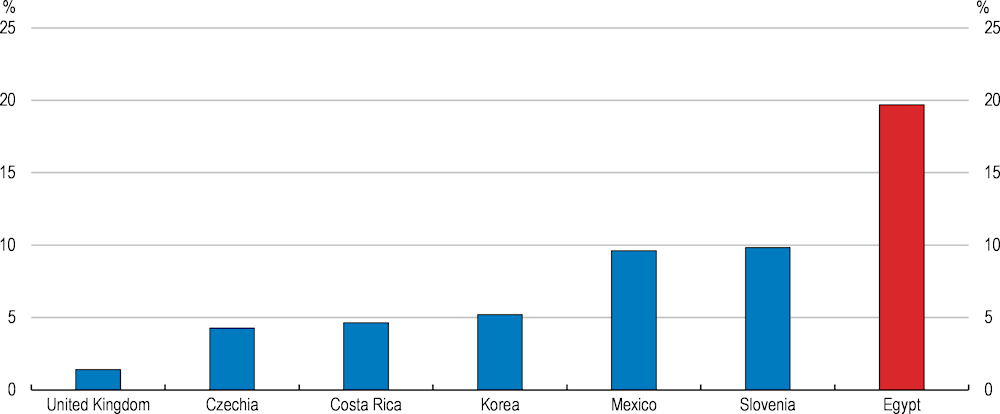

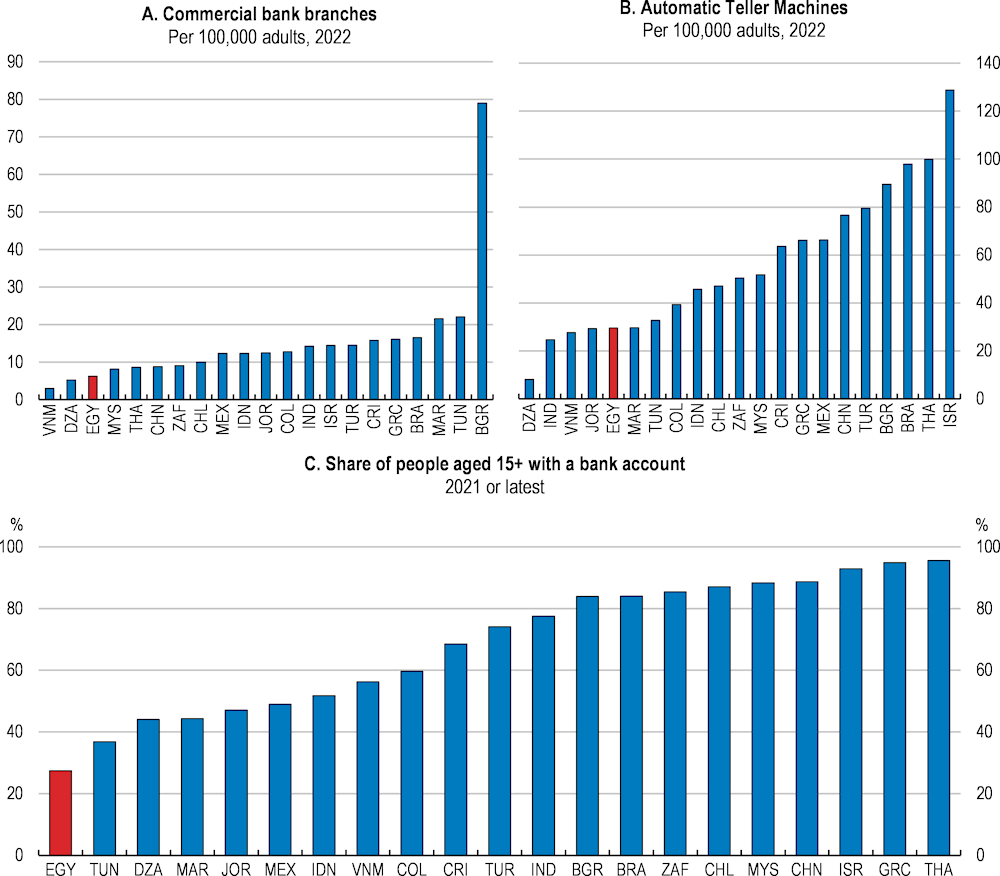

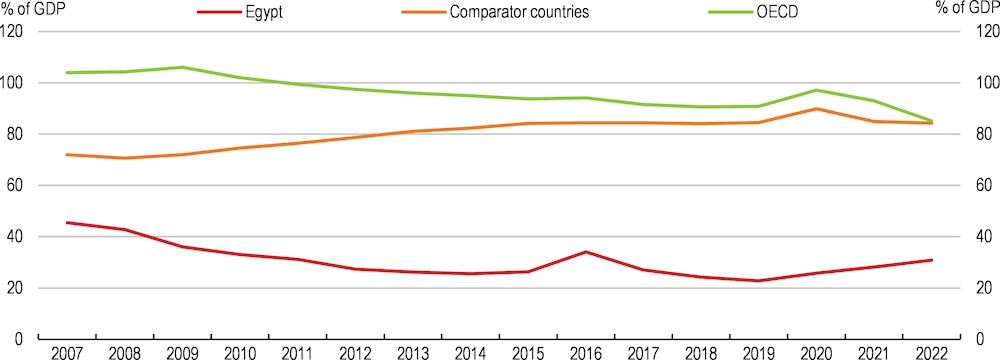

Productivity is the principal source of long-run growth. It provides the basis for better material living standards and improvements in well-being. Productivity is also the main driving force for economic convergence towards better performing economies (OECD, 2015d). In Egypt, labour productivity is still significantly below the OECD average (Figure 3.1, Panel A), with low overall investment (Panel B) and a declining share of private investment in the total (Panel C). Low investment in innovation and R&D also contributes to low productivity growth (OECD, 2015d). Egypt spends less than 1% of GDP on R&D (Figure 3.2). Moreover, total factor productivity (TFP) declined in most sectors between 2013 and 2018, against the backdrop of a deteriorating investment climate and the presence of regulatory barriers (Zaki, 2022).

Figure 3.1. Low output per worker is related to low investment

Note: Data for Egypt in all three panels refer to fiscal years (from July of indicated year to June of the following year). In this report, the following definitions are used: comparator countries refer to Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Greece, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, South Africa, Thailand, Tunisia, Türkiye and Viet Nam. Neighbouring countries refer Algeria, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia and Türkiye. These country aggregates are employed if data are available for at least 80% of the countries. Panel C: data for public investment include state-owned enterprises.

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook database October 2023; OECD, National Accounts database; Ministry of Planning and Economic Development; and OECD calculation.

Figure 3.2. Spending on research and development is low

Spending on research and development as a share of GDP, calendar years

Note: Country groups refer to simple averages of its members. For the definition of comparator countries refer to the note in Figure 3.11.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Slow productivity growth in Egypt is rooted in deep-seated structural causes that impede market competition and prevent a more efficient resource allocation. To ensure sustainable economic growth, as set out in the National Structural Reform Programme, policy reforms are required that can boost market competition and raise productivity to lift Egypt to a higher economic growth path. This is also needed to provide more and better-quality jobs to Egypt’s fast-growing and young population, to help tackle endemic youth unemployment (Chapter 4). The ongoing IMF Extended Fund Facility programme underlines the role of structural reform in general, including divestment, to shore up the Egyptian economy.

Against this background, this chapter explores ways to promote a more competitive business environment, shedding light on factors that are known to stimulate market competition and to facilitate the entry and expansion of new firms. First, it presents some stylised facts about productivity growth and competition. Then it turns to conditions needed to unleash private sector growth, starting with a conducive regulatory framework, an efficient judiciary and measures to fight corruption, as well as an enhanced competition law enforcement framework, and improved trade and investment policies. The next section then discusses how to reduce the state’s presence in the economy through the divestment of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and a levelling of the playing field. The last two sections discuss access to finance and digitisation, which are key growth enablers.

3.1. Weak productivity growth is related to a challenging business climate

Competition supports the process of economic convergence. Competitive pressure spurs firms to constantly improve to attract customers, through product innovation, better quality and higher efficiency. OECD research shows that diffusion of frontier technologies, thus productivity growth, is slow where competitive pressures are weak, be it at the macro, sector or firm level (Nicoletti and Scarpetta, 2003, Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016). Hence, competition is vital for market selection mechanisms to work and for efficient resource allocation (Andrews, Cingano and Conconi, 2014).

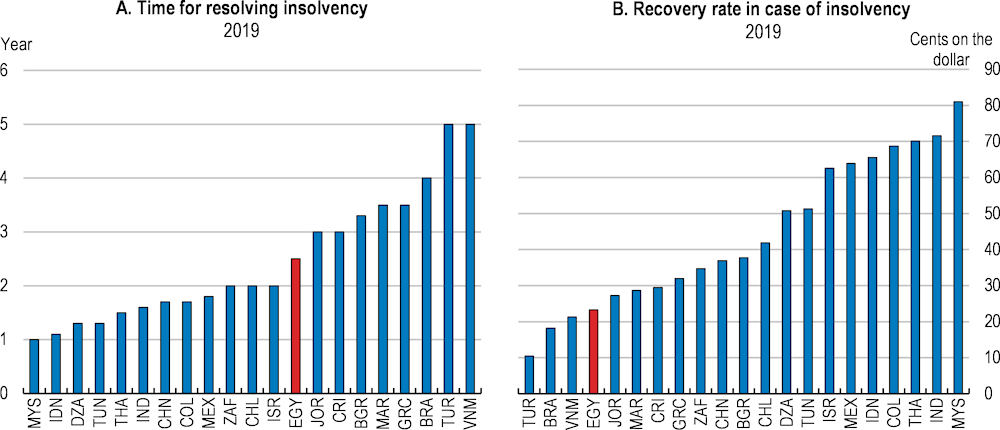

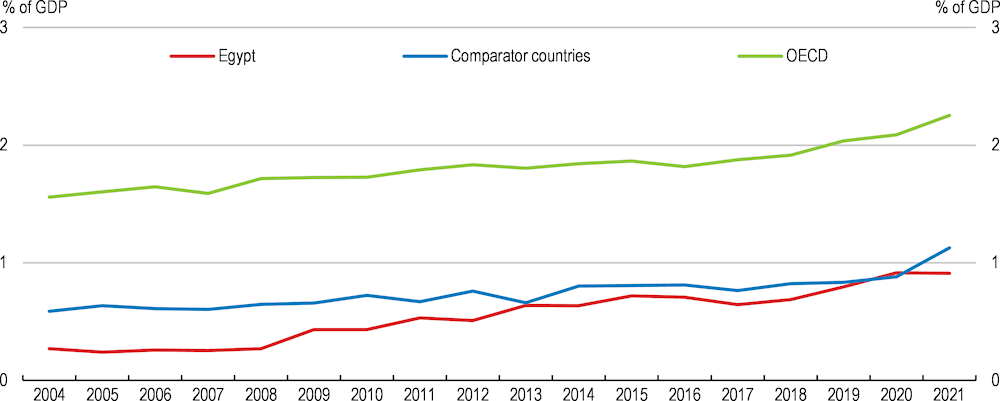

Business dynamism ensures that productive firms enter the market and grow, while unproductive firms exit and their owners can make a fresh start, which keeps up the competitive pressure (OECD, 2015d; Berlingieri et al., 2020). Egypt exhibits weak business dynamism: both start-up and exit rates are below regional and global averages relative to population size (AUC, 2022). The number of limited liability company starts related to the adult population is one of the lowest among Egypt’s peers, and significantly behind OECD economies with a dynamic business sector, and likewise for exits (Figure 3.3, Panels A and B). A low business churn rate, i.e., the rate at which companies are formed and exit, is typically associated with limiting factors that restrain business activity, such as regulatory restrictions (Thum-Thysen and Canton, 2017). The authorities are working to facilitate procedures related to the start-up of firms. For instance, a new legal type of firm, the one-person company, was launched in 2018, and the government supports initiatives offering funding to startups, including through Egypt Ventures, a government-backed venture capital firm (StartupBlink, 2023). Encouragingly, the number of newly incorporated companies is on the rise, from around 22 000 in 2018/19 before the pandemic, to 31 165 in 2021/22 and 32 447 in 2022/23. Low exit rates may reflect obstacles to the orderly exit of failing firms, such as inefficient insolvency regimes (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2016). The lack of competition and of fluid entry and exit reduces the pressure for firms to innovate or adopt better management processes. The OECD is currently conducting a Review of Business Dynamics that investigates firm entry, expansion and exit in Egypt, with results to be published in 2024.

Figure 3.3. Business dynamism is low in Egypt

Note: Enterprises here refer to limited liability companies. Panel A, data for Egypt cover 2015-22, data for Indonesia cover 2015-16. Panel B, data for Jordan cover 2018-20, data for Brazil, Costa Rica, Israel, Türkiye 2019-20, and for Indonesia - 2020. Averages chosen to smooth the impact of the pandemic in 2020 on business dynamism.

Source: World Bank, Entrepreneurship database.

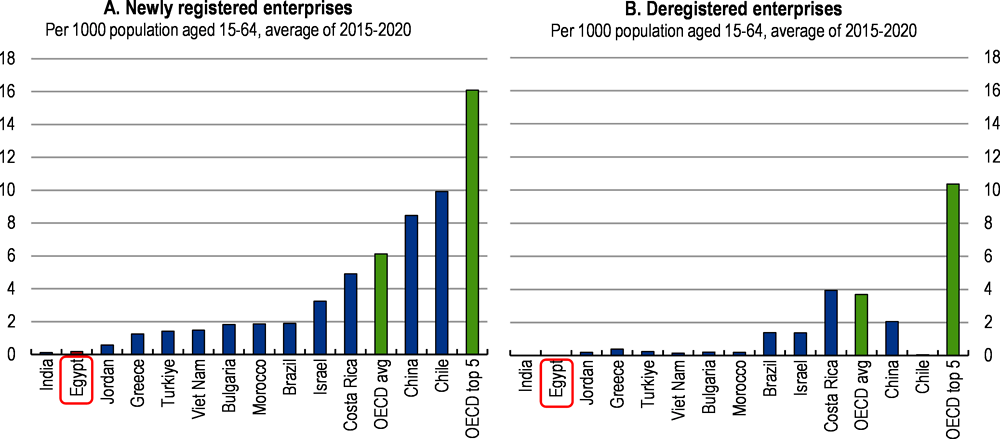

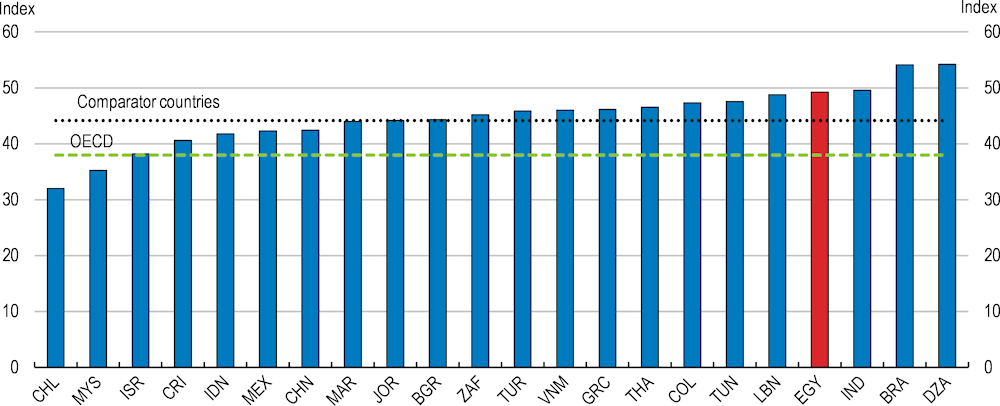

International indicators point to inefficiencies in product markets owing to Egypt’s regulatory environment (Figure 3.4). Complex regulatory procedures, a lack of trade openness, and high state control and involvement in product markets, compared to the OECD, impede business operations. Recent reforms are likely to have led to some improvement in Egypt’s position. In particular the 22 measures to support Egypt’s business and investment climate announced in May 2023 are welcome (Table A.1 in the annex). Even so, enabling Egypt’s private businesses to play a greater role in driving overall growth will require continuing with the reform of regulatory settings and the institutional framework within which Egypt’s firms operate.

Wide-reaching state involvement in the economy is crowding out the private sector (IMF, 2021). Including military-owned establishments, there are more than 700 SOEs in Egypt with combined assets of around 50% of GDP, some of which are joint-venture firms between the state and private-sector partners, often with complex ownership structures, involving ministries and/or other public sector firms, or other public stakeholders, which add to the complex landscape of state-involvement in the economy. In total, 33 state entities own and operate firms (18 ministries, 9 governorates, the Central Bank of Egypt, The General Authority for Financial Supervision, the Radio and Television Union, the Unified Purchasing Authority, the Upper Egypt Development Authority, and the Suez Canal General Authority), according to the State Ownership Policy Document follow-up report. SOEs are prevalent not only in the utility and public services typically provided by the state, but also operate in most other sectors (Ramirez Rigo et al., 2021). They have historically been endowed with tax benefits and better access to land and resources, thereby enjoying a competitive advantage. The authorities recognise the market-distorting impact of the SOEs, and the National Structural Reform Programme (NSRP) sets out measures to address the issue of state-ownership through a reboot of the country’s privatisation programme, and measures to provide for a level playing field.

Figure 3.4. Egypt’s business environment is restrictive

Business environment in product markets

Note: Business environment in product markets is an overarching indicator covering domestic market competition and trade openness, namely, distortive effects of taxes and subsidies on competition, extent of market dominance, competition in services, prevalence of non-tariff barriers, trade tariffs, complexity of tariffs, and border clearance efficiency.

Source: World Economic Forum (2019), Global Competitiveness Index 4.0.

OECD research quantifying the impact of structural reform finds that reforms in product market regulation (measured by an improvement in the OECD product market regulation (PMR) indicator over two years) lead to higher growth in per capita income (Égert and Gal, 2017). Such effects are found to be much stronger among emerging economies: stringent product market regulations have a three-times larger negative impact on TFP in countries with per-capita income lower than about USD 8 000 (in PPP terms). A similar pattern can be observed for doing-business indicators, the time for insolvency procedures and the time for starting a business. Policies that improve business and product market regulations can have substantial economic benefits in Egypt over the longer term, as indicated by quantitative estimates of the impact that some of the structural reforms undertaken by Egypt could have over time (Box 1.4, Chapter 1). Moreover, as confirmed by other studies, the benefits from structural reforms are particularly large when they are associated with institutional reform, aligning countries with principles of good governance, respect for property rights and measures to fight corruption (Égert, 2017).

3.2. Unleashing market forces to promote private sector expansion

To reap the full benefits of its policy reform programme (Chapter 1), building on the progress made in 2023, Egypt’s regulatory framework should be improved further, with a stronger competition law enforcement regime, enhanced institutional quality and lower corruption. Opening up for trade, attracting more foreign direct investment (FDI) and integrating global supply chains would also expand growth and development opportunities for Egypt’s firms (OECD, 2020b). These priorities are reflected in the government’s reform efforts, such as the NSRP, and in several reform initiatives under the Ministry of Trade and Industry. These include the National Strategy for Industrial Development (FY2022/23-2026/27), which targets priority industrial sectors in which Egypt has a manufacturing base, opportunities and competitive advantages, to move up the value chain. They also include the adoption of a National Single Window to facilitate customs procedures (Nafeza). The authorities’ efforts to attract more FDI through targeted measures have been followed by an increase in net FDI inflows from USD 5.1 billion in 2021 to USD 11.4 billion in 2022, mainly driven by rising cross-border merger-and-acquisition activity (UNCTAD, 2023), making Egypt the second-highest recipient of FDI among Arab states, behind the United Arab Emirates.

3.2.1. Improving market competition through regulatory reform

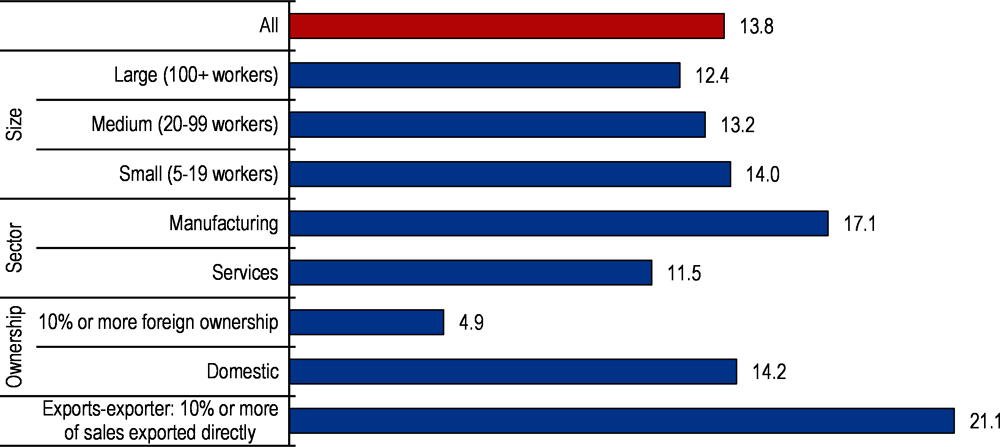

The operating environment in Egypt for both domestic and foreign firms is restrictive (Figure 3.5), although ongoing reforms to ease business regulations in Egypt are likely to lead to improved operating conditions, provided they are fully implemented. This should also enhance Egypt’s position in international comparisons. While licences and permits are useful regulatory tools to ensure adequate levels of service quality, counter market failures or allocate scarce resources, complex and excessive licencing procedures raise barriers to the entry of new firms, leading to potentially anti-competitive effects. Incumbent firms have strong incentives to lobby regulators to use licensing arrangements to protect themselves from new entrants. Permits can also increase costs and multiply barriers for businesses owing to the burden involved in compliance. Product market regulations, like any kind of regulation, may drift away from their original purpose and hamper the good functioning of markets. They can influence the productivity of existing firms by reducing their incentives to grow, innovate and adopt modern technologies (Arnold and Grundke, 2021). In addition, regulations and administrative burdens may create opportunities for corruption, especially if they involve multiple agencies delivering authorisations.

A high regulatory burden and the cost of compliance can also encourage informality. Kelmanson et al. (2019) find that poor regulatory quality, along with shortcomings in government efficiency and human capital are among the drivers of informality in emerging Europe. Workers and firms with little human and physical capital, and very low productivity, may choose to remain informal, as the regulatory and tax burden imposed by the requirements for entering the formal labour market is untenable for them (Loayza, 2018). In Egypt, the informal sector accounts for around one-third of GDP (Medina and Schneider, 2018), one of the largest shares in the MENA region, and slightly above the 29% global average for emerging markets (IMF, 2022). Under the OECD Egypt Country Programme, a study is being conducted to explore avenues to reduce informality, and the Egyptian authorities are already working to encourage firms to formalise: Law 152/2020 for the development of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) provides for a five-year exemption from stamp duty and other taxes and fees, as well as a full tax amnesty for all owed taxes, for firms that apply to regularise their status, in addition to other non-tax incentives. These efforts are complemented by the Financial Inclusion Strategy (2022-2025), approved by the Central Bank of Egypt. One of its objectives is to provide and facilitate MSMEs and start-ups’ access to financial services and to encourage their integration into the formal sector, as well as the provision of non-financial services. A new law (149/2023) grants the Industrial Development Authority (IDA) the possibility of delivering temporary three-year operating permits to unlicenced industrial firms, provided they commit to adhering to environmental requirements, civil procedures and related inspections. During the three-year period, the firm can regularise its statutes and employees.

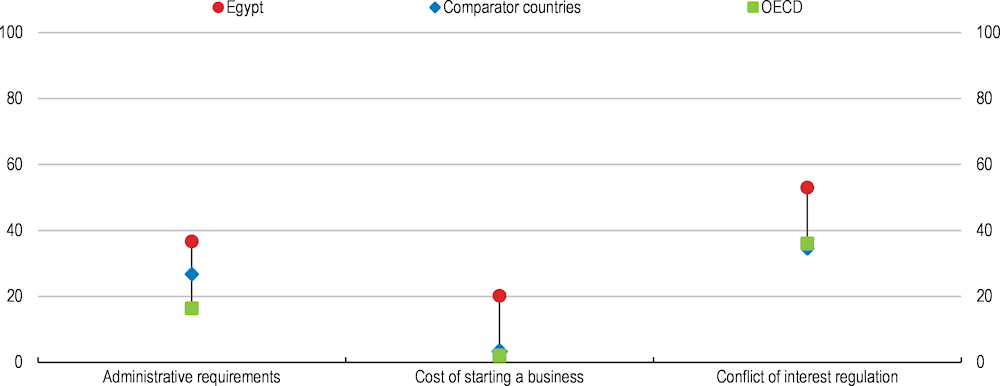

Figure 3.5. Barriers to entrepreneurship are high

Scale from 0 (not burdensome at all) to 100 (extremely burdensome), higher score corresponds to a poorer outcome, 2019

3.2.2. Reducing regulatory complexity to support business expansion

The licensing burden imposed on firms is high (Figure 3.6). Moreover, the cost of administration entailed in compliance has a disproportionate effect on micro and small enterprises (MSEs), which have more limited resources and account for some 98% of firms in Egypt. The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency (MSMEDA) can issue a five-year temporary licence for MSE. However, experience with size-based regulation show that this tends to be ineffective, as it may discourage smaller firms from growing, or lead to perverse outcomes, such as failing to declare revenues or staff once the critical size has been attained (Dabla-Norris et al., 2018). Ultimately, reducing the administrative burden on all firms will also benefit small firms. Despite recent reforms, it still takes at least 12 days for a firm to be fully operational after registration in Egypt, against nine days on average in the OECD (World Bank, 2020a; GAFI, 2023). The actual time to register a company has been known to reach 30 days (OECD, 2019e, 2020b), although recent reforms, including the August 2023 opening of an e-platform by the General Authority for Investment (GAFI) to register new firms online, should cut the time for the firm to be listed in the company registry to as little as two days. The principle of “silence is consent” for business registration or licensing, which implies that licences are issued automatically if the competent licensing authority has not reacted by the end of the statutory response period, is not used in Egypt (around half of the OECD countries used this principle in 2018). The one exception is for new micro and small enterprises that apply to incorporate under MSMEDA. Since the entering into force of Law 152/2020 on MSMEs in April 2021, they receive a renewable one-year licence. After two years, if no further exchange of information with MSMEDA has taken place, the principle of “silence is consent” will apply and they receive a permanent licence. This practice greatly enhances the business environment and should be applied to most business incorporations that do not involve toxic or hazardous products.

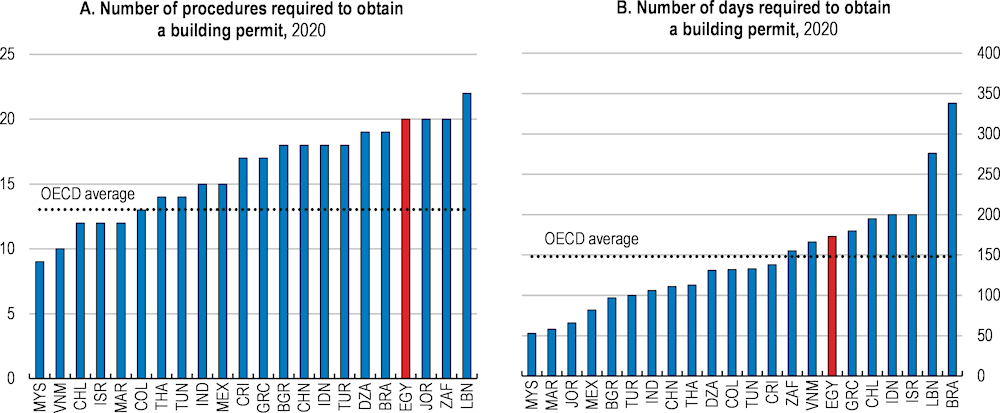

The new e-platform registry will help speed up firm registration, and should strengthen the functioning of the Investor Service Centre, created within GAFI under the 2017 Investment Law to help with business incorporation. However, post-establishment administrative requirements, which are equally important, remain heavy and add significantly to the burden (OECD, 2020b). For instance, obtaining a construction permit takes longer and involves more steps than the regional and OECD averages (Figure 3.7, Panels A and B). The overall amount of paperwork is also high. Registering employees for social security, a compulsory step in opening a business, involves providing copies of the graduation certificate of both the employer and the employee, as well as their birth certificate, and the lease agreement for the firm’s premises. The latter is also required for VAT registration, limiting opportunities for internet and data service firms that may not need physical premises. In the United Kingdom, only four procedures are required when establishing a firm, and all of them can be conducted online. In New Zealand, registering a business takes only half a day, and involves a single procedure which can be conducted online (World Bank, 2020b).

Figure 3.6. Business licensing is a major constraint for domestic businesses and exporters

Percentages of firms in Egypt1 identifying business licensing and permits as a major constraint, 2020

Note: 1. Share of respondent firms out of 3075 firms surveyed.

Source: World Bank, Enterprise Surveys.

Egypt’s regulatory landscape is also rather complex. The industrial sector is governed by seven different laws, 15 legislative amendments, as well as presidential decrees. Three ministries are directly involved in granting industrial licences (Environment, Interior and Health), but depending on the economic activity, a number of different ministries may be involved in providing licences and permits for the industrial sector. Other permits, such as construction permits, may be granted at the governorate level, subject to the local development plan. For heavy industry (such as steel and cement), their establishment or expansion requires a decision by the Prime Minister after determining the needs of the sector: investors then have to bid for licences that are made available by the Industrial Development Authority, with the final cost, the timing of new licences, the total market available, and the decision times not always known to bidders. Despite Cabinet decrees to address these issues in 2020 and 2021, just one bid has been submitted since. Some of the high licensing costs may serve to abate carbon emissions as these industries tend to be heavy polluters, but increasing transparency about the procedure, timing and cost would help to even the playing field for investors.

Egypt has taken steps to simplify the industrial licensing system. The 2017 Industrial Permits Act was intended to make the Industrial Development Authority (IDA) under the Ministry of Trade and Industry a one-stop-shop for industrial operating licences, as the only entity interfacing with businesses. However, manufacturers still need to seek pre-establishment approvals from local authorities, for instance for health and safety, or environmental impact, involving the Civil Protection Authority and the Environmental Affairs Agency, among others. This is also the case for the annual renewal of operating licences, which can lead to delays, reportedly of up to six months, which hamper business expansion, and may lead businesses to divest or work in the informal sector (OECD, 2020b). Long delays and the multiple agencies involved may also provide opportunities for corruption. However, the IDA recently issued a number of regulations to facilitate land allocation – a major stumbling block for industrial projects – as well as the issuance of operating licences. Measures include a simplification of the documentation required for prior notification, and better co-ordination between agencies involved in the licencing process, through the creation of committees where the IDA will represent the investor before the General Administration of Civil Protection, or the Environmental Affairs Agency. These measures could reduce the time to acquire an industrial licence to seven days for low-risk projects, and 20 days for high-risk projects.

Figure 3.7. Obtaining permits is a lengthy and complex process

Building on this initiative, Egypt should take a step further and make the most of information technology to provide fully-fledged one-stop shops for licences, permits, and other procedural requirements to make service delivery more streamlined and user-focused, as per the OECD’s Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (OECD Council, 2012). Fully implementing the Industrial Permits Act at the governorate level would help. The number of procedures involved in granting new and operational licences should be significantly reduced, and documentary requirements simplified. A recent measure now grants foreign investors a one-year residence permit during the incorporation period, allowing them to complete bank transactions, bank account opening and company incorporation procedures, but simplifying and digitising procedures would shorten the time needed for business incorporation.

Further, to minimise delays, Egypt should implement the “silence is consent” principle for the issuing of business registration licences for non-industrial licences, provided authorisations are carefully drafted to minimise the risk that this would lead to increased informality. Businesses could, for instance, be required to simply register their new business on a website, to be given the ID number required to proceed with other formalities, for instance to open the business bank account, and to facilitate spot checks. This would significantly reduce the burden and costs on both businesses and the administration, and interventions would only take place in case of a genuine need, such as for products or activities with a risk to health or the environment. The OECD Standard Cost Model provides details on how to reduce administrative costs and burdens, taking advantage of the experience in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Denmark (OECD, 2007). The model was successfully applied in Greece in 2014, identifying cost savings up to EUR 3.28 billion (OECD, 2014b).

3.2.3. Performing regulatory impact assessments

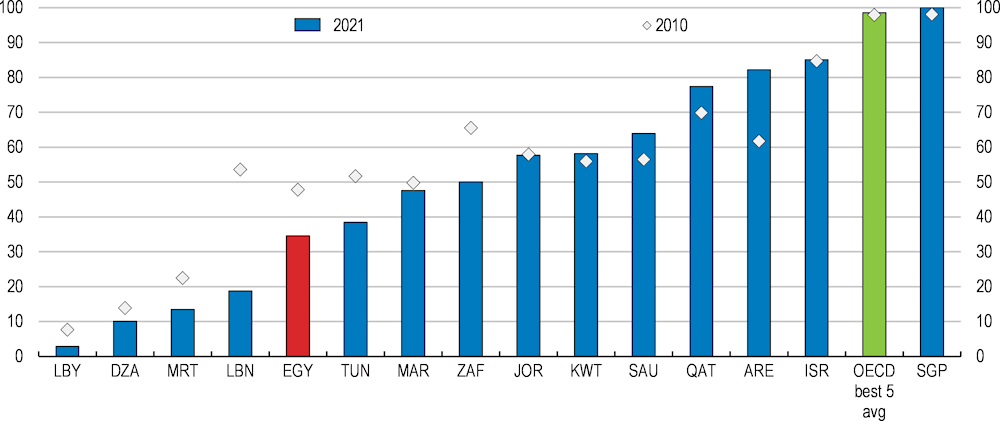

Regulatory quality in Egypt is perceived to be low, hampering private sector development (WGI, 2022) (Figure 3.8). Poorly drafted legislation creates legal ambiguity and insecurity which undermines investor confidence, and hampers the cost-effective delivery of policy objectives (OECD, 2019e; 2020b).

Figure 3.8. Despite reforms, regulatory quality has declined

Regulatory quality1, ranks from 0-100 (100=best)2

Note: 1. Reflects perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development. 2. Percentile rank among all countries (ranges from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest) rank). Singapore is the best performer. The Worldwide Governance Indicators collect six aggregate indicators, based on over 30 underlying data sources reporting the perceptions of governance of a large number of survey respondents and expert assessments worldwide. For details on the underlying data sources, the aggregation method, and the interpretation of the indicators see Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi (2010), "The Worldwide Governance Indicators: A Summary of Methodology, Data and Analytical Issues", World Bank Policy Research Working Papers, No. 5430.

Source: World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators.

To support a leaner and more efficient regulatory framework, Egypt should systematically carry out regulatory impact assessments (RIA) of new draft legislation, before its enactment, in line with the 2012 Council Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (OECD Council, 2012). Such assessments should include the expected impact on the fiscal budget, the investment climate, the environment, gender balance and market competition (OECD, 2020c). Carrying out regulatory impact assessment also allows legislators to identify what means, other than regulation, may help achieve policy goals. This should be complemented with an ex-post assessment of existing regulations against clearly defined policy goals, to ensure that regulations remain up to date, are cost justified, cost effective and consistent, and deliver the intended policy objectives. The principle of proportionality of a regulation should be respected throughout the process, meaning that regulation should be proportional to the objective it seeks to solve (Box 3.1).

In 2019 Egypt re-launched ERRADA (Egyptian Regulatory Reform and Development Activity: Egypt’s unit for regulatory review, first created in 2008) to support good regulatory practices, notably by assisting the government in improving regulatory quality and simplifying procedures. ERRADA’s tools include the ability to carry out a light review of draft legislation, conducting “light RIA”; to meet stakeholders that will be affected by legislative changes; and to conduct workshops on best practices. This is an encouraging initiative, but to be effective, ERRADA would require a stronger mandate to perform RIA systematically on draft legislation, and this should include quantitative assessments. This in turn would require more resources being directed to the unit, including more staff with the technical capability to conduct quantitative impact assessments.

Box 3.1. The principle of proportionality in EU legislation

The “principle of proportionality” underpins the legislative process in the European Union. Under this principle, EU regulations: (i) must be suitable to achieve the desired end; (ii) must be necessary to achieve the desired end; and (iii) must not impose a burden on the individual that is excessive in relation to the objective sought to be achieved (proportionality in the narrow sense). In the case of a breach of the principle of proportionality, the measures may be challenged before the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Source: Treaty of the European Union, Article 5(4) (European Union, 2007).

Egypt would also benefit from an ex-post evaluation of its sector regulations (also known as Competition Assessment), i.e., a full review of all existing laws and regulations of a sector to scan for potential regulatory obstacles to competition, such as excessive standard requirements or legal barriers to entry (OECD, 2019b). This would be particularly beneficial for the three NSRP priority sectors, manufacturing, agriculture and the information technology and communication sector (ICT); or sectors with high employment or growth potential, for instance tourism; or sectors with a high regulatory burden, such as the network sectors (mainly utilities), discussed below (OECD, 2019b). In Australia, since the mid-1990s, the National Productivity Commission has systematically carried out an assessment of existing product market regulations in the economy, reviewing more than 1 800 laws. A first stock-taking after ten years of reviewing and eliminating regulatory restrictions found that observed productivity and price changes in a number of selected sectors boosted Australia’s GDP by 2.5% (Productivity Commission, 2005).

In the past decade, several countries have undertaken such competition assessments with the support of the OECD, including Brazil, Greece, Iceland, Mexico, Portugal, Romania and most recently, Tunisia. In Greece, an OECD project identified benefits from lifting restrictions in four key sectors of the economy (tourism, food processing, retail trade and construction materials) amounting to more than 2.5% of GDP, while a review of tourism and construction in Iceland found benefits of around 1% of GDP from lifting sector regulatory restrictions (OECD, 2014c; OECD, 2020a). The Egyptian Competition Authority (ECA) has a mandate to review draft legislation for potential barriers to competition, but so far, its opinions are not binding. To improve the effectiveness of regulatory review, the ECA’s opinions should become binding.

3.2.4. Improving legal certainty and trust with a more efficient judicial system

The regulatory framework and institutional capacity for overseeing a competitive business environment, and for conducting reform effectively, are crucial to promote market competition. An effective legal system can provide firms with greater certainty when doing business, and limit costs when disputes arise (OECD/WJP, 2019; OECD, 2021c). It can also help to reduce corruption risks. Prolonged times to resolve cases and lack of judicial efficiency are cited as important impediments to investment in Egypt (overall, Egypt ranked 93rd out of 141 countries in the latest World Economic Forum assessment; WEF, 2019). Inefficient courts also detract from the effectiveness of competition enforcement as well as the anti-corruption system. Egypt ranks 130th out of 139 worldwide for effective enforcement of civil justice, and likewise (130/139) for regulatory enforcement, with a rank of 138th out of 139 for the sub-indicator, conducting administrative proceedings without an unreasonable delay (WJP, 2021).

Egypt’s courts remain under pressure from a high case load, despite the creation of the economic courts in 2008 (effective 2011). Around 9 million cases are settled annually in Egypt, but with an overall case load estimated at 12 million cases a year, this leaves a substantial backlog (Hesham, 2020). Enforcing contracts took on average 1 000 days in Egypt in 2019, of which 700 were spent on trial and judgement (Gold et al., 2019), almost four times the average in the European Union. The economic courts were created to relieve some of the pressure on Egypt’s court system by treating all cases related to commercial and competition law. Their remit was expanded in 2019 to also include consumer protection, bankruptcy, microfinance, cybercrimes, as well as aviation and maritime law, and in 2022 to include trade law. However, paper-based procedures continue to create many inefficiencies. Furthermore, outside of Cairo, the courts lack IT equipment and the means to implement automation which would help speed up processing cases. While economic court judges have received specialised training, further training is required to match the expanded jurisdiction since 2019 (Gold et al., 2019). Increasing judicial efficiency to support Egypt’s business environment will require more targeted investment in economic courts outside of Cairo, including through donor funding, in equipment, training and more administrative staff. As part of a USD 77 million Comprehensive Economic Governance agreement between the US and Egyptian governments, a project to support the development of the economic courts, including through digitalisation and better governance, was launched in June 2022.

Alternative dispute resolutions can help resolve these problems. The revised 2017 Investment Law established alternative out-of-court forums for foreign and national investors for resolving commercial disputes, including mediation, with support from the Investment Dispute Resolution and Investment Contracts Dispute Resolution centres in GAFI, which also includes a Grievances Committee. In addition, Egypt has set up a Ministerial Committee on Investment Disputes Resolution and a Ministerial Committee on Investment Contracts Dispute Resolution. The 2018 Bankruptcy Law gives the economic courts the jurisdiction for overseeing both bankruptcy cases and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms such as restructuring. Requiring, or strongly encouraging, firms to attend an initial mediation session or other alternative dispute resolutions can promote out-of-court solutions, and would help make this an efficient system and reduce the case load. On average across EU countries, using mediation before deciding whether to go to court has been shown to reduce the overall time to resolve disputes by up to 60%, and to cut average costs per case – comprising the use of courts, mediators and lawyers – by up to 33% (De Palo et al., 2014).

3.2.5. Combating corruption to promote a better business climate

Alongside judicial efficiency, tackling corruption is an important component of building an enabling business environment. Bribery and corruption discourage investment and distort international and domestic competitive conditions. Corruption hampers economic efficiency and leads to an inequitable allocation of resources. Moreover, the exploitation of public office for personal gain undermines state institutions and public trust.

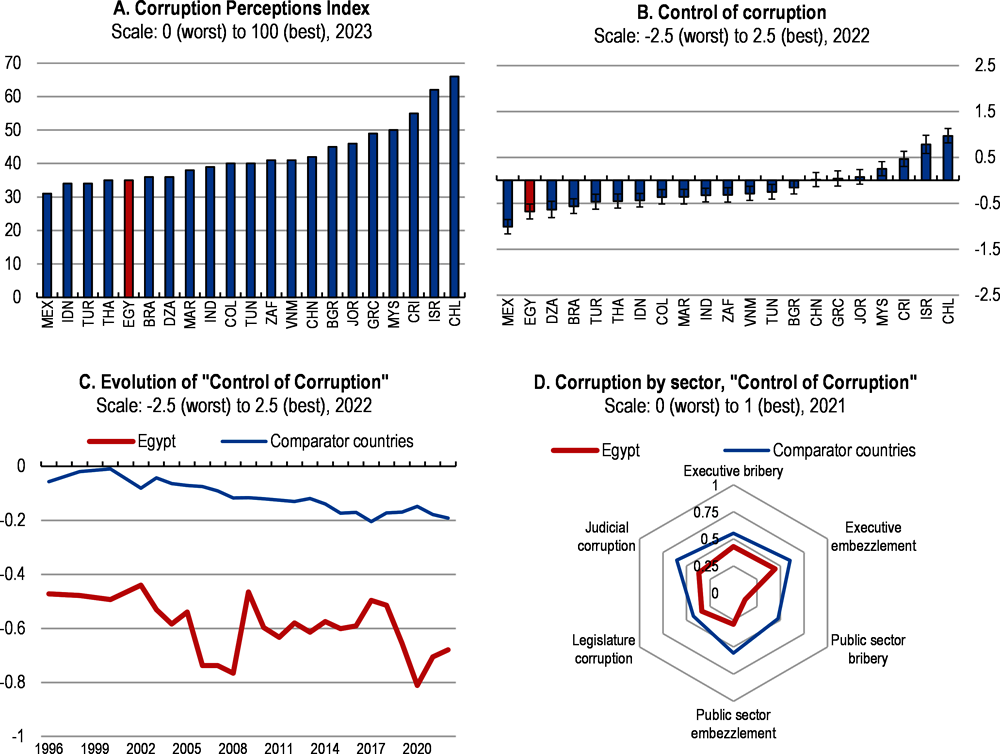

Perceptions of the control of corruption are worse than in many comparator countries and have tended to worsen over the past decade (Figure 3.9). Corruption is seen to be pervasive in Egypt according to several sources, encompassing both "petty corruption", such as facilitation payments, within the public sector, and "grand corruption" involving officials abusing public institutions. 35% of surveyed firms in 2020 identified corruption as a major constraint for doing business and 41% of firms expected to have to give a gift in order to obtain a construction licence (World Bank, 2020c).

Tackling corruption is high on the political agenda in Egypt. Vision 2030 has a strong focus on strengthening reform and good governance in the civil service to combat corruption and promote transparency and integrity. The Administrative Control Authority (ACA) was created in 1964 and has jurisdiction over state administrative bodies, SOEs, public associations and institutions, private companies undertaking public work, and organisations to which the state contributes in any form. The ACA reports to the President, who also appoints its head. However, the Law grants the ACA technical, financial and administrative independence, and the head of the ACA has the rank of minister and appoints the rest of the staff. Additional entities to fight and prevent corruption include a specialised national academy to build the capacity of ACA staff (OECD, 2020b). Other actors that have a role in supporting public integrity in Egypt include the Central Agency for Organisation and Administration (CAOA), the Accountability State Authority, and the National Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development within the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development.

Figure 3.9. Perceptions of corruption are high

Note: Control of corruption captures perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as "capture" of the state by elites and private interests. Panel B shows the point estimate and the margin of error or confidence interval. Panel D shows sector-based subcomponents of the “Control of Corruption” indicator by the Varieties of Democracy Project. For the definition of comparator countries in Panels C and D refer to the note in Figure 3.1.

Source: Transparency International; World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators; Varieties of Democracy Project, V-Dem Dataset v12.

On paper, Egypt has a strong legal framework to address corruption. It ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption in 2005. The Egyptian penal code criminalises active and passive abuse of power including facilitating payments and bribes, and a Conflict-of-Interest Law targeting senior public officials was passed in 2013. However, Egypt is not party to the OECD Convention on Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. A National Strategy for Combatting Corruption has been in place since 2014, with two programmes implemented in 2014-18 and 2019-22, while the third phase, to run from 2023 to 2030, was launched in December 2022 by the ACA. Yet, despite robust laws and multiple administrative efforts, corruption and money laundering remain a concern. The OECD Financial Action Task Force identifies Egypt as being exposed to “domestic risks of money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation”, in addition to risks related to transnational activities owing to its geographical position and long land borders, as well as the large size of the informal economy, which means that many transactions remain cash-based (FATF, 2021). The lack of progress with fighting money laundering and corruption is mainly because of poor implementation of the instruments in place, shortcomings in complaint mechanisms, such as assured anonymity, and a lack of protection of whistle-blowers, poor auditing, difficulties for the public to obtain information, and insufficient monitoring of anti-corruption policy (European Commission, 2017; FATF, 2021; Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022).

The Money Laundering Combating Unit, under the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE), is in charge of the supervision and enforcement of anti-money laundering measures. New regulations from late December 2023 aim to tighten banks’ monitoring of cash flows, particularly transactions made in USD and credit card deposits. The CBE and the Federation of Egyptian Banks have introduced measures to incentivise individuals and small businesses to join the formal financial sector. To this end, the National Council for Payment (NCP) was established in February 2017 to limit cash usage, encourage the adoption of electronic payment methods, and integrate citizens and businesses into the banking system. The CBE issued new regulations in March 2023 to introduce tokenisation services and promote the use of electronic and contactless payment methods. This has resulted in a significant increase in mobile payment accounts (“mobile wallet”), with around 34 million users by June 2023, according to the State Information Service. In addition, the Central Agency for Organisation and Administration is developing a new Code of Conduct and Ethics for internal compliance in the public administration.

Reforms should prioritise strengthening private sector and civil society involvement in promoting integrity. Indeed, promoting integrity is not only the responsibility of the public sector, but also that of citizens, civil society organisations and the private sector, as they can harm or promote integrity with their actions (OECD, 2017). This entails engaging relevant stakeholders in developing, updating and implementing public integrity policies, raising awareness in society of the benefits of public integrity, and encouraging misconduct reporting, amongst others. Legislating to safeguard whistle-blowers is also crucial (OECD, 2020b). Additionally, fostering a culture of accountability, integrity, and transparency across both public and private sectors is crucial, notably through public awareness campaigns that emphasise how civil society and the private sector are key actors in supporting public integrity, and providing civic education programmes at all levels of education to cultivate skills and behaviours to uphold public integrity (OECD, 2020d).

Some progress has been made in this area. The government is carrying out initiatives to promote awareness, education and training in the field of anti-corruption, mainly through the ACA, to raise awareness and improve public knowledge of corruption. Measures include support for anti-corruption education; promoting ethics and integrity training; and adopting the Global Initiative for Anti-Corruption Education and Youth Empowerment. Moreover, governments can also encourage integrity within the private sector by ensuring public integrity standards are established and implemented in companies, in particular through their lobbying and political financing practices, as well as in the movement between the public and private sectors (OECD, 2020d). To strengthen public integrity systems and practices, Egypt could also adhere to the OECD Convention on Bribery, and the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity, both of which are open to non-members.

Corruption in public procurement particularly harms private sector business dynamism notably by undermining investor confidence. A new Public Procurement Law was passed in 2018 to regulate public procurement processes. However, SOEs are exempt from its provisions, and the law still allows direct awards to “non-civil” entities (Tiemann et al., 2021). Since 2020, public entities must have a governance and compliance unit in charge of internal audits and monitoring of procurement, and the Ministry of Finance has announced its intention to start publishing all government procurement contracts above EGP 20 million on a monthly basis. Once it has been applied, the Ministry of Finance will also publish information on all bids made, the winning bid, and names of successful bidders. These are important steps to ensure that public procurement is competitive, non-discriminatory, and transparent (IMF, 2023). However, with the exception of the public health sector, there is no central government procurement authority. Each public entity carries out its own procurement which runs counter to recommended practice (OECD, 2015b), which is to centralise procurement to minimise opportunities for corruption and to enhance purchasing power.

OECD work on fighting bid-rigging in public procurement (OECD, 2023a) also underscores the benefits from centralising procurement. A survey of OECD member states found that central purchasing bodies obtain better prices for goods and services (100%), lower transaction costs (96%), improve capacity and expertise (81%), increase legal, technical, economic and contractual certainty (81%), and provide greater simplicity and usability (78%) (OECD, 2015e). Additionally, central purchasing bodies can play an important role in the implementation of secondary policy objectives, such as environmental considerations. The government is in the process of establishing an e-procurement platform. Doing so would also help minimise opportunities for bid-rigging. Under the OECD Egypt Country Programme, the OECD is engaged in a project on public procurement focusing on SOEs. Progress in this area requires fully implementing the new procurement law, removing the procurement exemptions for SOEs except in exceptional cases, which need to be clearly defined and published, as well as the direct-award option for non-civil entities. The authorities should also consider the benefits of moving towards more centralised procurement.

3.2.6. Strengthening the competition law and the competition authority

A good regulatory framework needs to be supplemented by an effective competition law and enforcement framework to enable market competition. Fair competition between firms allows for better outcomes in terms of innovation, prices and product quality while anticompetitive conduct by dominant firms can seriously inhibit incentives to innovate and diversify (Nickell, 1996; Aghion et al., 2005).

The Egyptian Competition Law was introduced in 2005, and the Egyptian Competition Authority (ECA) began functioning in 2006. The Competition Law covers both private and public operators, prohibits horizontal agreements, vertical constraints and abuses of dominant or monopolistic positions. The law does not apply to agreements made by the government to fix the price of designated “essential products”, nor to public utilities managed by the state or any of its public juristic persons. The Competition Law has been amended four times, in 2008, 2014, 2019, and 2022, to allow for merger control. From early on, the ECA took fairly strong action against breaches of the Competition Law (OECD, 2011a and 2012b). The 2014 amendments reinforced the ECA’s independence and powers to conduct investigations and strengthened its enforcement tools through enhanced settlement powers and a leniency programme. As a result, the number of ECA decisions against anticompetitive practices increased significantly from 2015, covering a wide range of markets, including insurance, pharmaceuticals, fertilisers, the health sector and poultry, and cases of abuse of dominance in telecommunications, electricity, media, health and sports (Arezki et al., 2019).

In 2017, the ECA carried out its largest bid-rigging case related to public tenders for governmental and university hospitals, which involved seven of the biggest suppliers in Egypt of medical equipment for heart and chest surgeries (Talaat and ElFar, 2017). Other large cases include a price-fixing cartel among 70 clay brick factories which was referred to court (Egyptian Competition Authority, 2018), and a case against the Qatari sports broadcaster, beIN, which was fined for abusive bundling of international football events (Nasser Al-Khulaifi / beIN Media). More recently, the ECA took on Uber to prevent a take-over of a regional ride-sharing firm. As a relatively young agency, the ECA’s track record has improved in recent years, in particular with regard to strengthening the legal framework, enhancing international co-operation (which is increasingly crucial for effective competition enforcement to address violations by multinational firms), and improving its enforcement (UNESCWA, forthcoming).

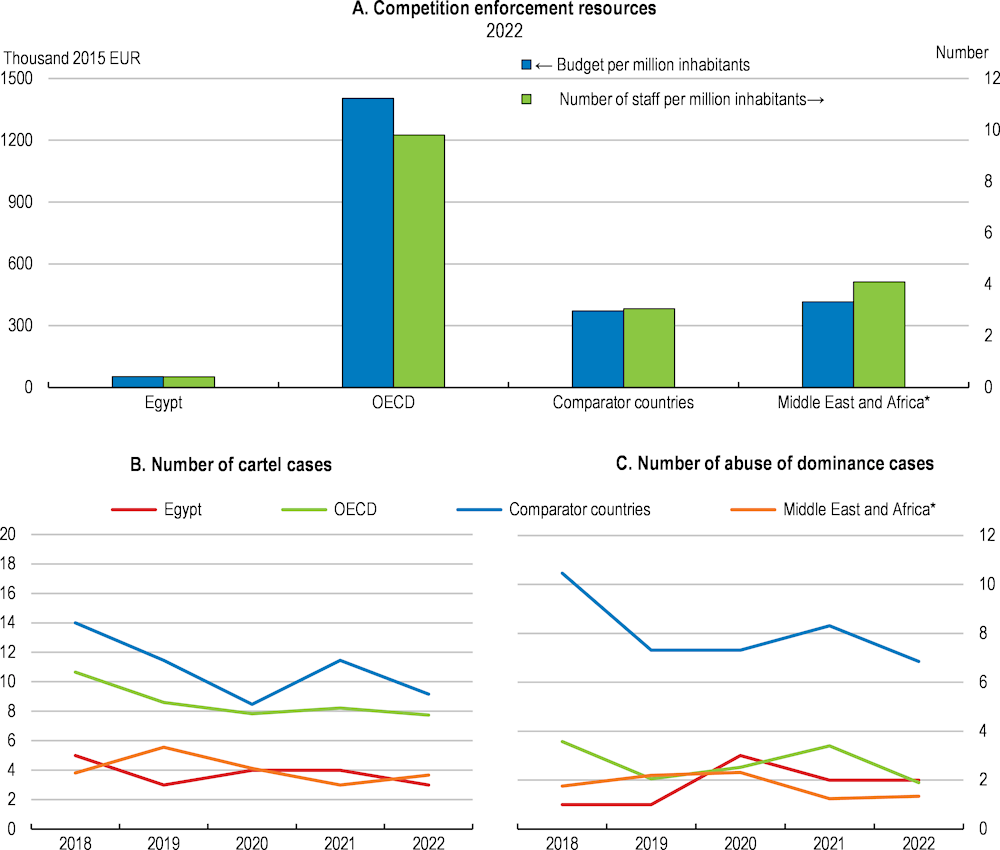

Sufficient staff and budget for competition authorities are key for them to function effectively and independently (European Commission, 2014). Budget allocation is a critical point on which undue pressure could be exercised and where appropriate safeguards should be in place (OECD, 2016a). Egypt’s enforcement record holds up well amongst its peers, but it has completed comparatively fewer cartel cases (Figure 3.10, panels B and C). Cartel investigations are resource intensive, and the ECA has fewer resources than most other competition authorities, even compared with the rest of the Middle East and Africa (Panel A), and despite its large population size. The state budget approved annually by Parliament includes ECA funding, but without a dedicated line of appropriation. Additional funding for the ECA can be provided in the form of grants or donations and, since the December 2022 amendment, a small fee for merger notifications. However, the executive regulations for the 2022 law have still not been published. To support its competition enforcement efforts, not least in light of the heavier burden implied by the work on competitive neutrality, the ECA could benefit from more staff and financial resources. This would also bolster its independence. Ideally, the agency should be funded from a combination of sources, to reduce the risk of dependence on a single source of funding (OECD, 2016a).

Figure 3.10. Egypt’s competition enforcement could improve further with more resources

Note: Data for Egypt was provided by Egypt Competition Authority and country aggregates were computed by OECD based on CompStats database. In Panel A, values were converted in 2015 EUR using exchange rates on 31 December 2015.In Panels B and C, the number of cases refer to absolute number of cases for Egypt and simple averages for country aggregates. Middle East and Africa* include Botswana, Egypt, Kenya, Mauritius, Tunisia, and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). For the definition of comparator countries refer to the note in Figure 3.1.

Source: Comp Stats, Egypt Annual Competition Reports to the OECD Competition Committee (2020 and 2021), ECA, OECD calculations.

The ECA’s mandate and ability to support the government’s competitive neutrality policies (see below) could be further improved with stronger independence to support its enforcement powers and guard it from political interference. The ECA’s governance structure may affect its independence, as the Board has ministerial representation, contrary to suggested good practice (OECD, 2016a). This is particularly important in view of the ECA’s central role in the recently created Higher Committee for Competitive Neutrality, which has been set up under the Cabinet to help preserve a level playing field in markets where SOEs are operating, discussed below. The Committee, which involves several key ministries, is tasked with examining breaches of competitive neutrality. One of the Committee’s first decisions involved an exclusivity contract carried out between a state authority and an undertaking affiliated with the military. The ECA’s powers related to competitive neutrality include tackling discrimination on any basis, including state ownership. The ECA’s Competitive Neutrality Strategy states that maintaining competitive neutrality includes encouraging a level playing field between all undertakings, regardless of ownership, nationality, or size.

As an enforcer, the ECA can document violations, issue cease and desist orders against anticompetitive practices and reach extra-judicial settlements with wrongdoers, but only the economic courts may impose fines for antitrust violations. The inability to sanction and to issue fines creates uncertainty on the final outcome of the ECA’s decisions and may make deterrence less effective (OECD, 2016a; Arezki et al., 2019). Moreover, the economic courts which deal with anti-trust violations have a high case load and enforcement is slow, further eroding the deterrent effect, as discussed above. To increase judicial certainty, the ECA could be granted the powers to sanction anticompetitive conduct associated with the ability to issue administrative fines for breaches of competition law, which is common in many OECD jurisdictions, and only refer criminal matters, such as cartels, to be decided by a court. In the case of Egypt, such measures would help safeguard the independence of the ECA and increase deterrence.

Further amendments to the Competition Law are pending in parliament to grant the ECA more independence. These amendments would create a more independent Board. They also give the ECA more budgetary autonomy, and it would gain the power now held by the judiciary to sanction anticompetitive practices and increase transparency through enhanced publishing obligations. These amendments should be passed as soon as possible. An amendment to improve the ECA’s independence should include granting it the status of “Autonomous Organisation” (Article 125 of the Egyptian Constitution) similar to other regulators such as the Financial Regulatory Authority or the Central Auditing Organisation. This entails being technically, financially and administratively independent; and the ECA would have to be consulted with respect to the bills and regulations that relate to its field of work.

3.3. Increasing competitive pressures through trade and foreign investment

Strengthening competitive pressures from abroad through trade and foreign direct investment raises competition (Arnold and Grundke, 2021) and increases firms’ competitiveness (Sakakibara and Porter, 2001). With total trade at around 40% of GDP (Chapter 1), Egypt’s economy is significantly less open to international trade than other emerging market economies of similar size. Trade liberalisation is associated with higher levels of investment and output (Boubakri, Cosset and Guedhami, 2005).

Competition in the domestic market can also be spurred by stimulating direct competition between foreign counterparts and Egyptian firms by attracting more inward investment. Access to superior service inputs, including through FDI, is crucial for advancing sectors like manufacturing, boosting economic growth, and creating more job opportunities. FDI can also help rebuild Egypt's capital stock and contribute to an expansion of exports, and increased participation in global value chains. Foreign firms bring innovation, introduce new products, improve processes, invest in R&D and tend to use more sophisticated technologies. Therefore, attracting FDI can enhance competitiveness and support the development of local enterprises through technology transfers, expertise and skills acquisition (OECD, 2020b, 2022b). To this end, and as part of its role in investment promotion, GAFI has set up an interactive online “investment map” to showcase different investment opportunities in Egypt to both local and foreign investors. It recently revised the investment-map development process to facilitate addition of more opportunities by different government agencies in various economic sectors. Information on the opportunities listed on the investment map includes property type and location, sector and market size, infrastructure availability and cost, incentives for the project, whether for local or export production, and associated costs, fees and permits for the project set-up.

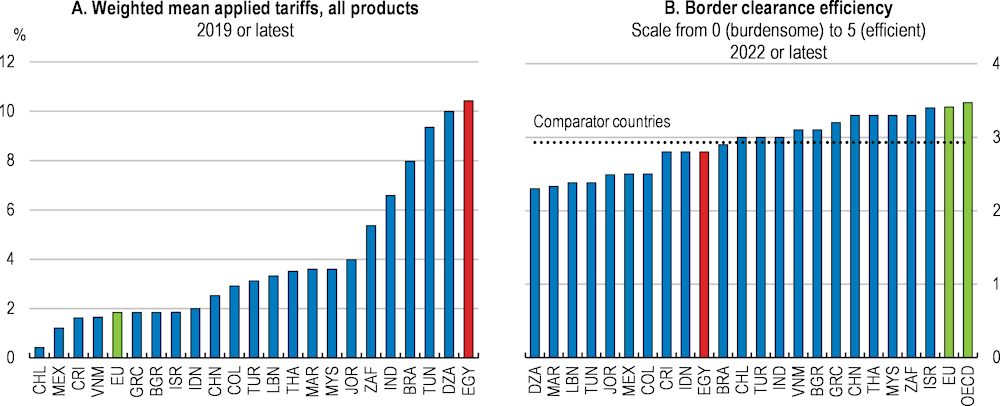

3.3.1. Tariff and non-tariff barriers are high

In Egypt external competition is hampered by trade barriers. Average tariff levels weighted by trade are the highest amongst regional peers, and more than twice as high as in Morocco or Jordan (Figure 3.11, Panel A). Egypt’s average trade weighted tariff was 10.5% in 2019 (most recent comparable data), but tariff rates are higher for agricultural products, and for imported alcoholic beverages (notably for the important tourism sector) where the maximum tariff is 3000%, and products that compete with Egyptian manufactured products such as textiles, where the tariff rate is 40-60%. The system is difficult to navigate: it contains 7 850 tariff lines (World Trade Organization, 2019) and rules change frequently (US Department of Commerce, 2022). The presence of import tariffs cushions many sectors from the forces of external competition. Opening up for trade, by lowering, simplifying and streamlining tariffs, would give a significant stimulus to competition. Moreover, increasing trade can help alleviate poverty over time through increasing the number and quality of jobs, stimulating economic growth and driving productivity increases. The poor also benefit from lower prices of imported goods when trade barriers come down (Bartley Johns et al., 2015; OECD, 2009b).

Figure 3.11. Import tariffs are high

Note: In Panel A, data for the countries presented refer to 2019 except for Thailand (2015), Tunisia (2016), Israel (2017), Mexico (2018), Jordan and Malaysia (2020). Weighted mean applied tariff is the average of effectively applied rates weighted by the product import shares corresponding to each partner country. When the effectively applied rate is unavailable, the most favoured nation rate is used instead.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators; World Economic Forum (2019), Global Competitiveness Index 4.0.

Competitive pressures are reduced when firms shelter behind non-tariff barriers. Egypt remains among the group of developing countries that have the highest frequency index, i.e., the share of products that are subject to non-tariff measures, and coverage ratio, i.e., share of imports that is subject to one or more non-tariff measures (Youssef and Zaki, 2019). Non-tariff measures include heavy registration and documentation rules, and the requirement to obtain an import licence. A long list of items such as household goods and beauty products must be pre-registered with the Egyptian General Organisation for Export and Import Control, under the Ministry of Trade and Industry, or they will be refused entry (US Department of Commerce, 2022). Technical barriers such as additional product requirements and local standards are widespread (Youssef and Zaki, 2019). While this is ostentatiously for quality assurance purposes, the effect is to limit competition, and simpler procedures, including mutual recognition of products that already fulfil national standards, would benefit trade. Such non-tariff barriers are essentially anticompetitive, and Egypt may forego opportunities to participate in global trade if the costs to meet additional market requirements are too high. Such costs can be related to product and production requirements, the conformity assessment and certification requirements, or to information requirements. These tend to be particularly prohibitive for small firms where the cost of simply gathering the necessary information can be disproportionately high. Well-designed and efficient processes, including use of relevant international standards, can help facilitate participation in trade by more and smaller firms, help ensure consumer trust, and help support good regulatory practices (OECD, 2023d). Previous studies also found that non-tariff barriers have a negative effect on trade in Egypt and the wider region (Ghali et al., 2013; Péridy and Ghoneim, 2013). OECD work to assess the impact of trade facilitation measures during COVID-19 demonstrate the importance of trade facilitation to support an effective supply chain (Sorescu and Bollig, 2022).

Efforts to automate administrative processes through the 2020 Customs Law are welcome and should be stepped up to reduce trading costs and delays. As international trade becomes more digitalised, customs procedures should be further streamlined to keep up with global progress (OECD, 2022d). In this respect, the creation of the National Single Window (Nafeza), which is meant to facilitate external trade and is becoming compulsory for any goods exported to Egypt, should support faster custom clearance, despite some teething problems, which are holding up the full roll-out of the programme. Border clearance has improved but remains comparatively slow (Figure 3.11, Panel B). To support faster import release, the General Organisation for Export and Import Control (GOEIC) is working on a new risk management system for inspection and testing of imported non-food industrial products, which should speed up processes by reducing the number of inspections to those selected by the risk matrix. However, Egypt should also simplify its tariff regime. Foreign traders whose products already meet domestic standards should not have to preregister their products with GOEIC. Import licences could be replaced by a simple registration with the customs authorities, as is the case in Europe, except for hazardous or security-related products. Removing pre-shipping clearing formalities, even if they comply with WTO rules, and abolishing pre-authorisation for products that meet domestic standards, would facilitate trade, and support a more competitive business climate. Digital trade facilitation measures can support such efforts (OECD, 2022d).

Trade liberalisation would support Egypt’s growth strategy. Costa Rica, for instance, undertook a vast trade liberalisation programme in the 1980s as part of its development strategy. It cut import tariffs unilaterally, from an average of 46.3% in 1982 to 16.8% in 1989 and 1.43% by 2021. Costa Rica also entered a large number of preferential trade agreements, supporting the creation of a robust export platform. Trade liberalisation has hugely benefited the economy and led to a profound diversification of the export portfolio, along with the emergence of new export, business and employment opportunities, including high value-added industries such as medical equipment and business services. The broad diversification of exports is a source of resilience during negative economic shocks, as witnessed during the Covid-19 pandemic (OECD, 2011b, 2023c; WITS, 2023). Costa Rica’s ambitious trade agenda has however demanded significant resources from the government plus technical expertise, which have been provided in part by international institutions and donors.

Other trade facilitation measures could involve the customs authorities liaising with all importers, exporters and manufacturers of essential goods, providing regular information on shipments of critical supplies and compiling concerns from the private sector to facilitate information flows, as implemented by New Zealand Customs (OECD, 2022d). New Zealand, in the mid-1980s, embarked on a thorough trade reform: over time, it unilaterally reduced tariffs (now at 2.2%), dismantled subsidies for its protected agriculture, and removed import licensing requirements, as part of a broader economic reform programme, boosting trade and inward investment (WTO, 2022). A twinning project, such as the two-year project between the Italian and Egyptian customs authorities from March 2021 to strengthen the administrative and operational capacities of the Egyptian Customs Authority, under the aegis of the European Union, is also a useful measure which could be replicated with other trading partners (EUItalia, 2021).

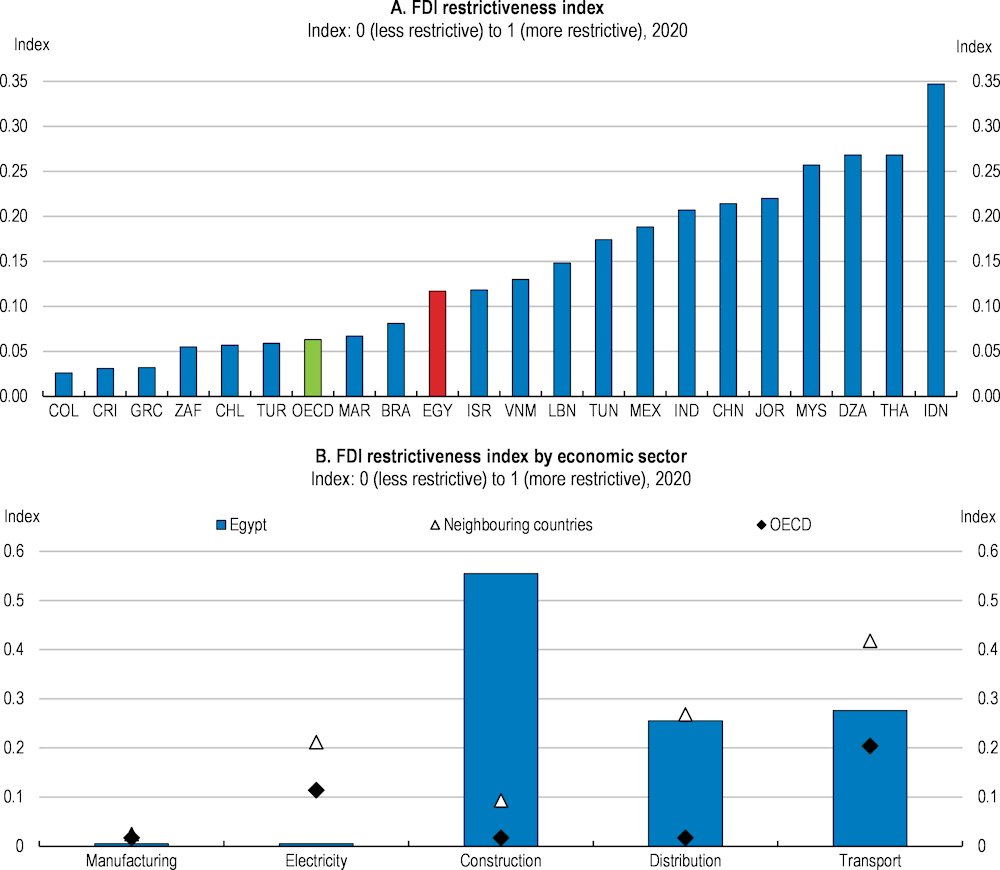

3.3.2. Barriers to foreign direct investment remain high

Regulatory obstacles to FDI are greater in Egypt than in most OECD and other emerging countries, hindering market competition. To create a conducive investment climate for foreign investors, Egypt has undertaken reforms, such as the 2017 Investment Law, which lifted most ownership restrictions for foreign nationals. However, certain sectors still require a joint venture with 51% Egyptian co-ownership. Additional recent legislative changes, including the new Companies Law, Bankruptcy Law, and Customs Law, further support investment activities for instance by allowing a smaller customs levy on firms that fall under the Investment Law.

Despite these reforms, Egypt has scope to further reduce barriers to FDI as reflected in the OECD FDI Restrictiveness Index (Figure 3.12), although Egypt performs better than some OECD member states. Sector-specific legislation maintains foreign equity restrictions and imposes limits on foreign-controlled firms’ entry and operations. Restrictions exist on foreign ownership in activities such as civil aviation and tourism transportation (OECD, 2020b). Commercial agents must be Egyptian nationals. However, a May 2023 legal amendment allows foreign investors to be registered as importers for a 10-year period, even if they do not hold Egyptian citizenship, to help them import goods for their projects.

Figure 3.12. There is scope to improve Egypt’s FDI regime

Note: The FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (FDI Index) measures statutory restrictions on foreign direct investment across 22 economic sectors and is bound between 0 (open) to 1 (closed). It gauges the restrictiveness of a country’s FDI rules by looking at the four main types of restrictions on FDI: 1) foreign equity limitations; 2) discriminatory screening or approval mechanisms; 3) restrictions on the employment of foreigners as key personnel and 4) other operational restrictions, e.g., restrictions on branching and on capital repatriation or on land ownership by foreign-owned enterprises. The discriminatory nature of measures, i.e., when they apply to foreign investors only, is the central criterion for scoring a measure. The FDI Index is not a full measure of a country’s investment climate. A range of other factors come into play, including how FDI rules are implemented. For the definition of neighbouring countries in Panel B refer to the note in Figure 3.1.

Source: OECD (2023), Foreign Direct Investment restrictiveness indicator.

All foreign investments, including touristic activities, undergo security screening and require government approval on a case-by-case basis, leaving room for discretion and causing delays. A new decree aims to reduce the duration of security screenings to ten days, past which the security clearance is considered to be granted. This would be a positive step. Foreign ownership of agricultural land, as well as land in the attractive Sinai Peninsula and border regions is prohibited. Investment projects in Sinai require an Egyptian shareholding of at least 55%, but a 2022 decree exempts the sites of Sharm-el-Sheikh, Dahab and Aqaba from this provision. While a recent presidential decree grants the right to apply for Egyptian citizenship to investors that invest more than USD 300 000, or make a non-refundable deposit of a similar amount with the Treasury, it remains unclear whether this grants access to land purchase in restricted areas. Removing remaining barriers to foreign involvement, particularly for commercial agents, traders, and the tourism transport sector, could attract more inward investment and foster market competition.

3.3.3. Simplifying incentives to minimise the anti-competitive impact

Tax incentives, when well-designed, can effectively encourage investment in areas such as R&D, innovation and the green transition. However, poorly-designed incentives may limit efforts to mobilise tax revenues, or even reduce them, without generating new or significant “additional” investment, thereby creating windfall gains to investors that would have invested anyway, even in the absence of the tax incentive, or yielding investments of low quality, with limited spillovers on productivity and employment (OECD 2022c). To ensure a level playing field, as recommended by the OECD Council (2021), the authorities could improve the design of their tax incentives, notably by using cost-based rather than profit-based tax incentives (OECD, 2022c).

Egypt employs a wide range of tax incentives to attract foreign investors (although in principle incentives are available to all investors), including tax holidays, income tax exemptions, accelerated depreciation, reductions in customs duty, and stamp duty exemptions for new projects. So-called “special tax incentives” are granted based on criteria related to investment type and location, ranging from 50% to 30% of investment costs, such as for investments in green hydrogen; in labour-intensive projects (if the wage cost exceeds 30% of the operating costs); projects where exports account for at least 50% of the output; or investments in deprived areas. Egypt also implements various special (“free”) zone regimes, again depending on location and the type of investment. These include Free zones, Investment zones, Technological zones, Industrial zones and, under a separate law, the Suez Canal Economic Zone (Box 2.4). The Council of Ministers can also grant a “Golden Licence” to targeted investors in accordance with a list of project types and criteria that was expanded in 2023 to include green and infrastructure projects (Box 3.2). By mid-February 2024, 26 such licences had been awarded according to GAFI, the General Authority for Investment.

GAFI assesses eligibility for the special tax incentives, while the Ministry of Trade and Industry can provide incentives for industrial projects, and the Council of Ministers can provide additional non-tax incentives on a case-by-case basis, such as free personnel training or separate customs facilities, a rebate on land costs and on infrastructure costs. So far these types of incentives have not yet been allocated as they involve post-project allocations from the state budget, requiring multi-authority co-operation. Moreover, granting post-establishment incentives involves paying out state financing that is not allocated in the budget, which creates a dilemma from a fiscal perspective, and may render the incentives difficult to implement de facto.

Inconsistent interpretation of incentives can distort competition in the market. Moreover, incentives that target specific locations or sectors may not yield the expected results (OECD, 2020b). In Egypt, the complex governance structure of both tax and non-tax investment incentives, with multiple overlapping authorities empowered to grant permissions, and several co-existing legal texts, further increases the risk that incentives do not fulfil their foremost objective of attracting more foreign investment. Consolidating tax incentives into a single law under the Ministry of Finance can increase their transparency and reduce potential overlap and duplication (OECD, 2022b). Such work is currently underway by the Ministry of Finance, to support a more stable tax legislation environment. This is encouraging. Tax incentives should furthermore be reviewed regularly to ensure they continue to be the right policy instrument to meet the investment objectives.

The granting of incentives should ideally be triggered by “outcome conditions” which are a more indirect way of linking tax relief to substance than minimum conditions: for instance, tax relief could be conditioned ex-post on the firm effectively creating a certain number of jobs, or reaching a certain value-added to output ratio; or investing a determined share of capital in R&D (OECD, 2020b, 2022c). An OECD project on tax-incentive reform in Egypt is ongoing and will include a discussion on the interaction between tax incentives and the global minimum tax (OECD, 2023b/CTP, forthcoming). The Ministry of Finance is working to standardise tax rates and exemptions, and aims to review them regularly. Two reports on tax policy and tax expenditure are also under preparation (Chapter 2). These should be published as soon as they are ready to increase transparency and certainty for businesses.

As in the case of investment incentives, several bodies appear to have overlapping roles with respect to investment policy. The 2017 Investment Law grants the Supreme Council of Investment, under the President of the Republic, the power to establish investment frameworks and policies, while GAFI oversees operational matters. The Council approves the investment policies and plans that determine the priority of targeted investment projects in alignment with the state's overall policy, economic and social development plan, and sets investment priorities. Between 2017 and 2019, the Ministry of Investment co-existed with the Council, but the Ministry was then absorbed by the Prime Minister’s office in December 2019, and the Prime Minister became the acting Minister for Investment (the 2017 Investment Law stipulates that there must be an investment minister; it would require a new law to remove this position). Formally, it thus appears that the Prime Minister is mandated with the formulation and execution of investment policy in co-ordination with the Cabinet of Ministers, while GAFI remains in charge of investment promotion. At the same time, the provision of investment incentives formally lies with GAFI, but the Ministry of Trade and Industry and the Supreme Council for Investment can also grant incentives, while the Ministry of Finance is tasked with their execution.

Separating the functions of investment promotion and operational matters from the overall formulation of investment policy strategy, and multiplying the bodies involved in investor relations, may lead to co-ordination difficulties that could hamper effective implementation of reforms and the maximisation of investment potential. It also makes the institutional landscape more opaque for investors. Egypt’s business environment would benefit from having a clearly communicated investment strategy with the investment portfolio gathered into a single entity, for instance, a fully-fledged Ministry of Investment, while GAFI should be solely in charge of investment promotion. Subsequently, reporting lines and the division of tasks and responsibilities between the Supreme Council for Investment and GAFI should be further clarified and enforced, beyond the provisions in the 2017 Investment Law, to enhance transparency and ease of use for investors. Decisions arising from other ministries that affect the process and cost of doing business should be cleared by a technical body, for instance a secretariat within the Supreme Investment Council, or in a future Ministry of Investment, to limit any negative impact on the wider business climate.

Box 3.2. The Golden Licence

A so-called Single Approval, or “Golden Licence”, was created in the 2017 Investment Law. It dispenses the investor from all further licensing procedures. Issued by the Council of Ministers, rather than the usual channels, it is supposed to be quick, comprehensive and directly enforceable. A holder of a Golden Licence may also be granted further tax incentives and reductions in fees and customs duties, as well as in-kind “special incentives”, such as a special customs outlet for the project’s imports or exports. The state also offers to bear the costs of connecting utilities, training personnel, and allocating plots of land, among other incentives.

The use of the Golden Licence system has been expanded, and investors are encouraged to apply through GAFI or directly through Cabinet. The list of criteria of eligibility to obtain the licence, including the type of project, the legal form of the firm and other attributes, has been expanded beyond the previous ‘priority’ areas. However, the Committee at GAFI that oversees the attribution of the Golden Licence acts on a case-by-case basis with full discretionary powers over the attribution of the licence, and it is not clear how the different criteria are weighed up. The process remains heavy: the applicant still has to submit a similar number of documents as for a normal business licence application. There have also been teething problems, with investors reporting that local authorities do not recognise the legality of the licence. The Golden Licence does not address the wider issue of over-regulation; it merely increases the speed at which successful applicants obtain their licences. Finally, the distinction between projects that receive the usual investment incentives, and those that obtain the Golden Licence, is not clear. Recent changes to the executive regulations of the 2017 Investment Law expanded the use of the Golden Licence to include most legal forms of companies, not just those established under the Investment Law, and to companies established before the Investment Law came into effect. However, while all firms are now in theory eligible, the size and nature of the projects on offer (such as green hydrogen plants) for the Golden Licence means that most such licences will be awarded to large firms.

3.4. Reducing the state footprint to support competitive markets

The state may choose to have recourse to SOEs to help address market failures, ensure fast or quality public service delivery, and contribute to the broader economy, provided they operate efficiently, transparently and on a level playing field with private enterprises. However, state-ownership is often associated with weaker corporate performance, in particular for firms that are wholly owned by the state, with inefficient management and declining or even negative returns on assets (Musacchio, Lazzanini and Farias, 2014). Poorly governed SOEs can negatively affect wider economic growth, crowd out more productive private sector activity and strain public resources (Szarzec, Dombi and Matuszak, 2021). When inadequately regulated, they can also be abused for political patronage or self-enrichment, reducing the confidence of public and private investors (OECD, 2015c, 2018a).

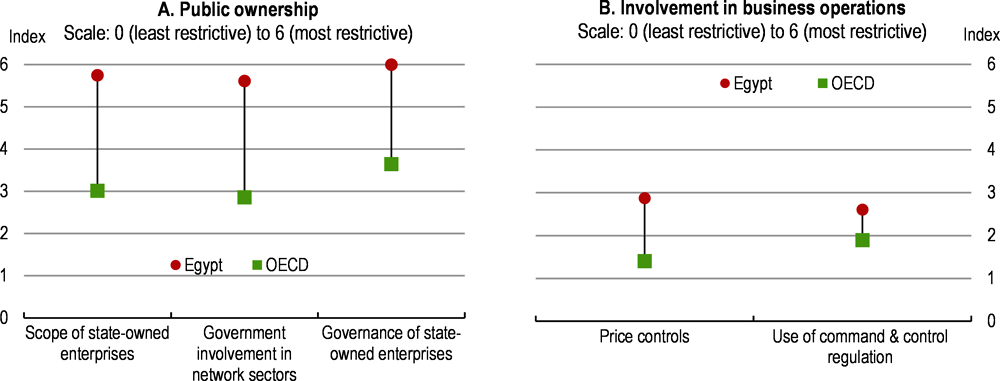

Public ownership and state-involvement are factors that likely distort market competition in the Egyptian economy. According to the OECD-World Bank product market indicators (PMR), the governance of SOEs does not conform to best practices, while the state is highly dominant in the network sectors, such as electricity, water, energy, railways, insurance and aviation (Figure 3.13). The PMR indicators were collected in 2017, but according to the latest available data, the state maintains a dominant presence in the network sectors, which remain heavily regulated, and the state often plays a dual role as both owner and regulator, potentially leading to conflicts of interest. This affects competition and productivity both in those sectors and in the downstream sectors that rely on their inputs, for instance, manufacturing (Conway and Nicoletti, 2006). Indeed, a study carried out in India found that reforms to liberalise similar service sectors, such as the banking, telecommunications, insurance and transport sectors, all had significant positive effects on the productivity of manufacturing firms (Arnold et al., 2015). Reducing the weight of the state in the economy by carrying out privatisations, implementing a level playing field, and resolving conflicts of interest in network sectors, would support private sector expansion.