This chapter reviews the existing collection, availability and quality of VET system-level data and sets out how system-level data for the PISA-VET Assessment differ from those used in the context of PISA. The chapter proposes an approach to using system-level data in the PISA-VET Assessment, drawing on existing data collections and a new system-level questionnaire to complement existing data.

PISA Vocational Education and Training (VET)

9. System-level data on VET

Copy link to 9. System-level data on VETAbstract

Introduction

Copy link to IntroductionThe purpose of system-level data in the context of the PISA-VET Assessment is to help the interpretation of the assessment and contextual data that will be collected. System-level data provide contextual information on national VET systems and allow for analysis of the relationship between results in the PISA-VET Assessment and various features of the design and delivery of VET in different countries.

From PISA to the PISA-VET Assessment

Copy link to From PISA to the PISA-VET AssessmentThe system-level questionnaire for PISA consists of a set of worksheets referring to the structure of national programmes, national assessments and examinations, instruction time, teacher training and salaries, educational finance (including enrolment), national accounts and population data. Not all countries participating in PISA complete this questionnaire; only those that are not already part of a joint data collection project led by UNESCO, the OECD and Eurostat, which collects the same information through annual surveys (see Box 9.1).

Many issues addressed by the system-level questionnaire in PISA are relevant for the PISA-VET Assessment. At the same time, there are differences, which mean adaptations to the collection and use of system-level data are needed to allow for meaningful international comparisons. In this regard, this section highlights three main differences between PISA and the PISA-VET Assessment: the target population, the prior education of learners, and learning providers.

First, the target population of the PISA-VET Assessment is different from that of PISA. For PISA the target population is 15-year-old students – more specifically, students between 15 years and 3 (completed) months and 16 years and 2 (completed) months at the beginning of the testing period, attending educational institutions located within the country, and in grade 7 or higher (OECD, 2019[1]). In practice, this includes mostly students in the early stages of upper secondary education and as well as some at the final stages of lower secondary education.

By contrast, the target population for the PISA-VET Assessment is not defined by age, but by a specific level of targeted learning outcomes: EQF 3-5 (or equivalent), or ISCED levels 3, 4 and 5. This translates into a broader age range and may cover more levels of education than PISA, depending on the ages and stages of education at which the targeted learning outcomes are provided. More specifically, the PISA-VET Assessment focuses on learners in initial VET who are close to completing an occupationally focused programme of study (both school-based programmes and those with substantial work-based learning). Therefore system-level data are needed to describe the profile of learners targeted by the PISA-VET Assessment in each country (e.g. age, level of currently pursued education) to help the interpretation of results and allow for meaningful comparisons.

At age 15 (i.e. in the PISA sample) enrolment in education is near-universal across OECD countries (and the extent to which it is not universal can be captured by a single indicator, such as the share of 15-year-olds in formal education). By contrast, participation in VET is not universal and there is no single age range or education level that could be defined as “the one” associated with VET. It is therefore useful to include system-level data that capture the use of vocational education and training at different ages and at different levels of education across OECD countries.

Second, the prior education of VET learners targeted by the PISA-VET Assessment is variable in a way that is more complex than in the case of PISA. Typically, 15-year-old students who are in upper secondary education have lower secondary education as their prior education, while those in lower secondary education will have primary education as their background. In the case of the PISA-VET Assessment there are two sources of heterogeneity in the prior education of VET learners. One source is that the targeted learning outcomes may be delivered at distinct levels of education. If automotive technicians are trained at upper secondary level in one country, most learners are expected to hold a lower secondary qualification as prior education. In another country training for automotive technicians may be delivered in short-cycle tertiary programmes, so that learners will have already completed (general or vocational) upper secondary education prior to starting their occupationally oriented programme. An additional source of heterogeneity in prior education is that even a specific level of education may be pursued by learners with different educational backgrounds – with variation within an individual country and/or between countries. For example, in Germany vocational ISCED level 3 programmes (dual system) target to a large extent young people who have recently completed lower secondary education, as well as an increasing share of graduates of upper secondary education (general programmes). In Australia, on the other hand, vocational programmes at this level (Certificate III) are delivered after the completion of initial schooling, so that many learners already hold an upper secondary qualification, and the average age of students is around 30. An additional complication is the enrolment of adult learners in VET, who come with a distinct education and work experience background.

Third, learning providers are more diverse for vocational programmes than they are in the case of programmes serving 15-year-olds. At age 15 instruction takes place predominantly in schools, except for the youngest participants in vocational programmes with work-based learning, who represent a small share of the target population overall. By contrast, vocational programmes targeted by the PISA-VET Assessment may be delivered in different educational institutions, such as upper secondary schools, training providers that are not viewed as part of initial schooling (e.g. TAFE-s in Australia) or tertiary education institutions (e.g. when vocational programmes are provided at short-cycle tertiary level), as well as workplaces. For the PISA-VET Assessment, it is therefore important to consider system-level data on where vocational programmes are delivered, including information on the use of work-based learning.

In addition to these three factors, various system-level features related to the occupational nature of VET programmes need to be added, as those are of course not addressed by PISA.

The proposed approach to system-level data on VET

Copy link to The proposed approach to system-level data on VETMuch information on VET is available through existing data collections within the OECD. These are publicly available online and/or are included as indicators published in the annual OECD Education at a Glance report. In the light of the wide range of system-level data that might be used to underpin the interpretation and analysis of the PISA-VET Assessment, this chapter proposes a slightly different approach to the PISA system-level questionnaire. Rather than selecting a set of indicators and including them in a pre-filled questionnaire, the proposal is to provide an overview of the available system-level data for two reasons. First, the comparative data mentioned in this chapter go through a thorough validation process and are publicly available online and/or published in Education at a Glance. Including them in a pre-filled questionnaire for countries to check is therefore not necessary. Second, the specific indicators that are relevant and most helpful for comparative analysis depend on the question in focus and countries to be compared. So, it is better to map out data on system-level features and allow users at later stages to select those most suited to the analysis.

Overview of available system-level data

Copy link to Overview of available system-level dataThis section provides an overview of currently available system-level data and metadata collected under the Indicators of Education Systems (INES) Working Party and its networks, in particular the UNESCO-OECD-Eurostat (UOE) data collection, the Network on Labour Market, Economic and Social Outcomes of Learning (LSO) and the Network for the Collection and Adjudication of System-Level Descriptive Information on Educational Structures, Policies and Practices (NESLI) (see Box 9.1). In addition, household surveys, such as the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) and the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) in EU countries, and individual-level surveys, such as the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) collect information on the educational background of participants and provide insights on VET.

Box 9.1. Data collections under the INES Working Party

Copy link to Box 9.1. Data collections under the INES Working PartySeveral annual data collections provide insights on VET and ad-hoc data collections (which may be one-off or cyclical surveys) focus on specific topics (e.g. VET systems, completion rates in upper secondary or tertiary education, VET finance). The regular data collections include:

UNESCO-OECD-Eurostat (UOE): The annual UOE questionnaires collect data on the enrolment of students, new entrants, graduates in various levels of education, educational personnel, class size, educational finance, and other aspects of education.

Network on Labour Market, Economic and Social Outcomes of Learning (LSO): The work of the LSO Network, mainly through labour force survey data, focuses on various outcomes of education, including educational attainment; school-to-work transitions; adult learning; employment, unemployment and earnings; educational and social intergenerational mobility; and social outcomes, such as health, trust in public institutions, participation in the political process and volunteering.

Network for the Collection and Adjudication of System-Level Descriptive Information on Educational Structures, Policies and Practices (NESLI): The Network for the collection and adjudication of system-level descriptive information on educational systems, policies and practices develops indicators for collection of system- level data.

The place of VET in national skills systems

Copy link to The place of VET in national skills systemsThe issue

Copy link to The issueData on participation in VET shed light on the position of VET within national skills systems. In many countries in continental Europe, Latin America and Asia, VET is one of the options at upper secondary level (ISCED level 3). By contrast, in some other countries (e.g. Canada, United States), upper secondary education is predominantly general (though students may choose vocational courses usually as a small part of the curriculum) and VET is mostly offered at postsecondary level. This means that preparation for the same occupation might be offered at a different level of education in different countries. For example, electricians are trained in upper secondary level apprenticeships in Switzerland with off-the-job training delivered in vocational schools (SDBB, 2023[2]), while in Canada a common route to becoming an electrician includes a one-year postsecondary certificate programme followed by an apprenticeship or a two or three-year college programme (OCAS, 2023[3]). In many countries, provision is developed at both upper secondary and higher levels. Vocational postsecondary and professional tertiary programmes (mostly at ISCED levels 5 and 6, but also some at level 7) offer avenues of progression for graduates of the upper secondary VET system, as well as serving general upper secondary graduates (OECD, 2022[4]). Data on participation also help gauge the size of the VET system at a given level of education and across different levels. Entrance and enrolment rates in VET and their evolution over time, are also viewed sometimes as indicators of the attractiveness of VET systems (Cedefop, 2014[5]) – although it is important to keep in mind how decisions about vocational or general enrolment are made (see below).

Existing comparative data

Copy link to Existing comparative dataThe UOE data collection provides data on entrants, enrolment (i.e. current students) and graduates by ISCED level and programme orientation. The three measures provide a different picture and need to be interpreted differently. While entrants and graduates measure the number of students at the start and at the end of programmes, enrolment data provide a different picture as they are shaped also by the duration of programmes.

Data are available for all countries, where vocational programmes exist at those levels, for all three levels targeted by the PISA-VET Assessment (ISCED 3, 4 and 5). Data can be broken down by a range of variables, such as gender, age, field of study, part-time or full-time mode of study. Complementing the picture, data are available on the highest qualification held by individuals in the workforce through the LSO data collection (with various breakdowns, such as gender, age and outcomes).

Pathways into and from VET

Copy link to Pathways into and from VETThe issue

Copy link to The issueThe educational pathways that lead to vocational programmes and the mechanisms for selection and/or self-selection vary greatly across countries. In some systems (e.g. Austria, Germany, Switzerland) tracking occurs at the entry to lower-secondary education, based on academic achievement. In most OECD countries, differentiation occurs at upper secondary level, based on different mixes of choice, selection and self-selection. In a few OECD countries (e.g. Canada, United States), upper secondary education is predominantly general, with vocational programmes being one of the postsecondary or tertiary options on offer. In Australia upper secondary level vocational programmes serve mostly young adults who have already left the school system, rather than being one of the routes within initial schooling.

The opportunities for higher level studies open to VET graduates and the extent to which they are pursued also vary considerably between countries (and sometimes within between different vocational tracks within a country). Some vocational programmes have a strong emphasis on preparation for higher level studies, sometimes connected to the field of study targeted by VET (e.g. progression from one of the vocational tracks in Netherlands to universities of applied sciences). By contrast, in some countries, progression from upper secondary VET to higher levels is a mere theoretical option, with few people choosing to pursue higher levels of education and many falling by the wayside. Finally, some vocational programmes do not allow graduates to enter higher level programmes directly, although there are typically bridging programmes that allow for such progression.

Existing comparative data

Copy link to Existing comparative dataVarious data sources are available on different aspects on the routes that lead into vocational programmes and progression opportunities after VET. These include:

Stratification and selection into VET: ISCED mappings provide data on the age of first selection. Qualitative data on the transition to upper secondary education and pathways from upper secondary VET to higher levels were collected in the context of the INES ad-hoc survey of upper secondary completion rates (2020 and 2023 cycles).

Completion: Data on completion rates are collected through cyclical INES ad-hoc surveys at upper secondary and tertiary level, separately identifying ISCED 5 programmes (which are predominantly vocational). Completion rates measure the percentage of new entrants to a specific level of education who complete their programme (in these surveys reporting completion within the theoretical duration of the programme and within theoretical duration plus two years).

Transitions to higher levels of education: ISCED mappings describe higher level programmes to which each programme provides direct access. This allows to identify potential entry routes into vocational programmes, as well as pathways from vocational upper secondary programmes to bridging programmes, postsecondary and tertiary education. In addition, data are collected on an annual basis on the share of students in upper secondary vocational education who pursue programmes that provide direct access to tertiary education. On the use of progression pathways, several data sources are available. The LSO data collection yields data on the highest qualification held by current tertiary students. The cyclical INES ad-hoc survey on tertiary completion rates collects data on the orientation of the upper secondary qualification held by first-time entrants to tertiary education, as well as data on the share of students who took at least a gap year between these two levels. Finally, the 2023 INES ad-hoc survey on upper secondary completion rates collected data on the education programmes pursued by VET graduates one year after graduation.

Profile of VET participants

Copy link to Profile of VET participantsThe issue

Copy link to The issueData on the profile of learners (and graduates) provide a picture of the population served by vocational programmes. Data on gender and socio-economic background are useful to identify challenges related to equity and measure changes over time. The age of participants signals the target population (and different mixes of profiles) served by vocational programmes – teenagers, young people with some labour market experience or older adults. Even within a specific level of education, there may be much variation across countries in the average age of participants (e.g. the average age of first-time upper secondary VET graduates is 18 in Korea and 29 in Ireland (OECD, 2022[6])). The profile of learners may also evolve over time – in Germany for example, the average age of apprentices has been increasing since 1993, as upper secondary vocational programmes increasingly enrol learners who already hold an upper secondary qualification (BIBB, 2021[7]).

Data on other aspects of the profile of learners are also important in terms of equity, in particular on socio-economic background and gender. Effective VET systems need to offer high-quality learning options to students from all backgrounds and avoid being a vehicle for segregation in education and training. In many countries, enrolment in VET is influenced by academic achievement, which in turn is correlated with socio-economic background (OECD, 2016[8]). The challenge is to ensure that learners enrol in VET because it suits their interests and abilities, and not because of their personal circumstances, which they cannot influence (OECD, 2016[9]). Similarly, VET systems need to offer equal opportunities to men and women. Gender imbalances in particular fields or types of programmes, for example, can raise equity issues – in an apprenticeship system dominated by the construction sector, the benefits yielded by apprenticeships fall disproportionately on men. Policies typically aim to address this in two ways: widening the coverage of programmes (e.g. expanding apprenticeships into traditionally female occupations) and encouraging entry into non-traditional occupations (e.g. encouraging women to train as electricians).

Existing comparative data

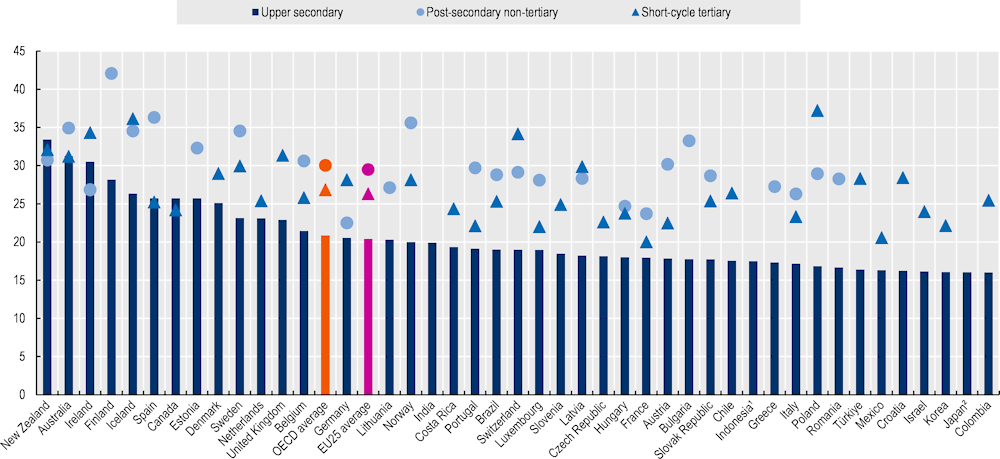

Copy link to Existing comparative dataVarious regular data collections (UOE, LSO) provide comparative data that can be broken down by age and gender. These include data on entrants, currently enrolled students and graduates in educational programmes at various levels. It is possible to identify, for example the average age of participants or graduates, the share of learners above a particular age etc. Figure 9.1, for example, shows the average age of learners in upper secondary, post-secondary non-tertiary vocational programmes, as well as in short-cycle tertiary education, illustrating the different functions of vocational programmes across different countries. Additional breakdowns are also available, such as gender by field of study, which is relevant in the context of VET. Comparative data on the socio-economic background of VET learners are patchy. The system-level questionnaire will seek to fill this gap.

Figure 9.1. Average age of learners in vocational programmes, by level of education

Copy link to Figure 9.1. Average age of learners in vocational programmes, by level of educationIn years

The delivery of VET

Copy link to The delivery of VETThe issue

Copy link to The issueVocational programmes may be delivered in various types of VET institutions (such as schools, colleges, or technical institutes) and workplaces (e.g. in the context of apprenticeships or internships).

How institutions that deliver vocational programmes are organised is an important part of the national context. In some countries a range of provider types exist, in others one type of institution delivers programmes at a specific level (OECD, 2022[11]). The function of institutions also varies, as some are specialised institutions focusing on vocational programmes only (including sometimes a focus on a specific field of study) while others deliver both general and vocational programmes.

How much and in what ways work-based learning is used also varies considerably across countries. Strong VET systems need to exploit the many benefits of work-based learning – using workplaces as a learning environment for the acquisition of both soft and hard skills, motivating learners to learn by helping them connect what is taught at the VET institution to real work contexts and saving on costly equipment in workshops of VET institutions. The extensive use of work-based learning can also help relieve teacher shortages, while the availability of work placements sends a signal of employer needs in an occupation, helping to shape the mix of provision.

In addition, some specific venues are also used in some countries, such as inter-company training centres and replicates of workplaces. Inter-company training centres managed by employers typically involve classroom-like settings for theoretical instruction and/or workshops for the development of practical skills. They typically complement school-based and work-based learning. Replicates of real workplaces in VET institutions allow learners to reap some but not all the benefits of work-based learning. For example, in a restaurant run by a catering school, students cook and serve real customers, though they may not face the same pressures and expectations as in regular restaurants and they do not gain useful connections with potential employers.

Existing comparative data

Copy link to Existing comparative dataCurrently data are available on whether institutions are public or private, including indicators of participation within different types of institution. Data are also regularly collected on the share of part-time and full-time students. Additional questions in the system-level questionnaire will provide further information on the institutions that provide vocational programmes (e.g. types of provider institutions, whether they deliver general programmes or vocational programmes in different fields).

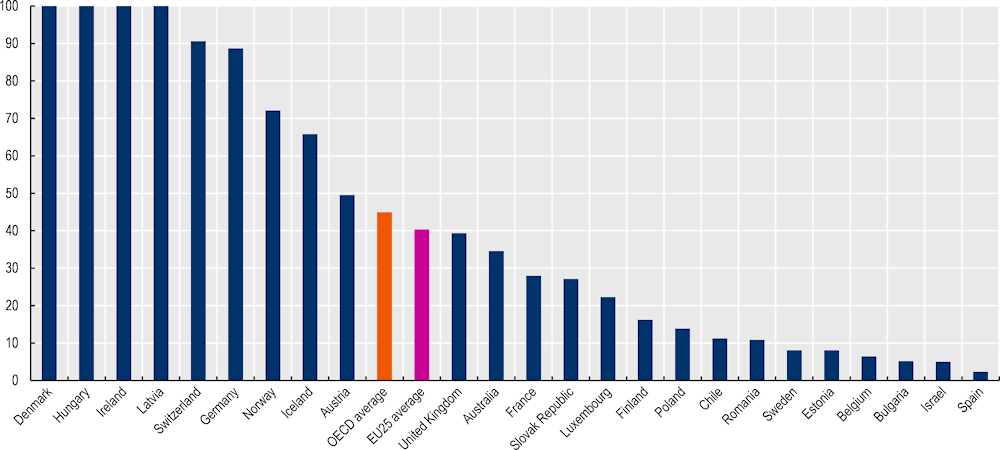

Information is collected on an annual basis on the share of VET learners in combined school- and work-based programmes (i.e. those involving work-based learning that accounts for 25-90% of programme duration). Data are available for upper secondary VET programmes in most countries – Figure 9.2 shows how the use of work-based learning varies across countries. Additional information on the type of work-based learning within different vocational programmes is collected since 2022 through ISCED mappings (distinguishing between apprenticeships, long internships, short internships, optional work-based learning, or none).

Figure 9.2. Share of upper secondary vocational learners in combined school and work-based programmes (2021)

Copy link to Figure 9.2. Share of upper secondary vocational learners in combined school and work-based programmes (2021)In per cent

Note: Combined school- and work-based programmes involve work-based learning that accounts for 25-90% of programme duration.

Source: OECD (2023[10]) Figure B1.5

Skills targeted by VET

Copy link to Skills targeted by VETThe issue

Copy link to The issueThere is much variation across countries in the mix of skills targeted by VET. Some VET systems remain dominated by traditional trades and crafts, often in construction and manufacturing, while others have successfully expanded into non-traditional areas, such as banking or ICT. While the PISA-VET Assessment will directly assess occupational skills in a selected set of occupations, data on fields of study targeted by VET can help situate the targeted programmes in a broader context.

The employability skills measured by the PISA-VET Assessment include literacy as one of the core generic skills needed by VET graduates (see Chapter 7). General skills like literacy, numeracy and digital skills are crucial in allowing transitions into tertiary education and more broadly, supporting lifelong learning. There is increasing awareness among policy makers, in the context of the green and digital transition driving greater need for worker reskilling and upskilling, that vocational programmes must prepare not just for a first job, but also for further learning. Yet too many people leave the education system, including VET programmes, with weak general skills. Measuring to what extent vocational programmes target general knowledge and skills (or general subjects, like mathematics more broadly) is important to gauge the attention to general vs. vocational skills across countries and programmes. In practice, all vocational programmes contain a mix of general and vocational content, but in varying proportions. Some programmes put strong emphasis on general skills – typically those that prepare graduates for entering tertiary level programmes (e.g. universities of applied sciences). Others have strong focus on occupational skills and include a small element of general education. The attention dedicated to general subjects also depends on the education background of the target population. Some programmes serve partly or predominantly learners who already hold an upper secondary qualification (often a general qualification). Information on the time dedicated to general subjects should therefore be interpreted together with data on other features of the VET system, including the profile of participants.

Existing comparative data

Copy link to Existing comparative dataData are available on graduates by field of study, although the breakdowns include relatively broad categories (1 or sometimes 2-digit ISCED-F categories). Further details are not collected on the content of vocational programmes (e.g. balance between general and vocational content), so this issue will be addressed in the system-level questionnaire for the PISA-VET Assessment.

Teachers and trainers

Copy link to Teachers and trainersThe issue

Copy link to The issueAs in general education, the quality of the teacher and trainer workforce is critical to effective learning in vocational programmes. Many countries are facing a wave of retirements among teachers or expect have one soon. Recruiting new teachers is often hard, as schools/colleges struggle to compete with salaries in the private sector. The challenge is particularly great in occupations where skilled workers (and therefore potential teachers) are in high demand and therefore offer the best career prospects. The second challenge is to ensure that VET teachers have a combination of up-to-date technical skills and pedagogical skills. Full-time teachers in VET institutions often lack industry experience and opportunities to update their technical skills, while those recruited from industry often lack pedagogical skills. In the workplace, trainers who supervise VET learners play a key role. When a substantial part of the programme is delivered in a workplace (e.g. apprenticeships), the learning experience at work is crucial and several countries offer mandatory or optional targeted training for trainers (OECD, 2022[12]).

The challenges of adequate supply and quality are interrelated, with policies often having implications for both. For example, strict pedagogical requirements designed to ensure quality can discourage entrants into the teacher profession (OECD, 2022[12]). To avoid this, some countries offer flexible ways of acquiring pedagogical skills.

Existing comparative data

Copy link to Existing comparative dataData on teachers are regularly collected through the UOE data collection, including breakdowns by age and gender. In addition, the NESLI data collection provides data on different types of teachers in vocational programmes (focusing on upper secondary education). Data on the profile of teachers (e.g. age distribution) provide information on the supply of teachers and extent of the recruitment challenge across countries. Data on qualification requirements for different types of teachers can shed light on how countries use entry and continuing professional development requirements to ensure the right competences among teachers. In addition, in the 2024 cycle of TALIS eight countries will survey teachers and school leaders in upper secondary schools, covering also vocational programmes. Further information is available from Cedefop in 29 thematic perspective reports from European Union member states, plus Iceland and Norway regarding VET teachers and trainers (Cedefop, 2023[13]). To fill gaps, the PISA-VET Assessment’s system-level questionnaire will include questions on teacher qualification requirements aligned with the NESLI data collection. Additional questions will explore requirements and training opportunities for in-company trainers, which are currently not covered by most of the international data collections. When the TALIS 2024 questionnaires are finalised, the system-level questionnaire may be updated to exploit synergies with TALIS.

Finance

Copy link to FinanceThe issue

Copy link to The issueAs for all education and training programmes, financial resources are key in steering the system. Financial resources can encourage institutions to offer some programmes rather than others and steer the number of places offered in each occupation. This is essential to ensure the mix of provision is responsive to labour market needs. Funding arrangements need to consider the targeted field of study, recognising that some programmes are cheaper to deliver than others – one challenge is that the high costs of starting new programmes (e.g. new equipment, staff recruitment) encourages the continuation of existing programmes and discourages the introduction of new programmes. Financial tools are also commonly used to encourage employers to offer work-based learning – for example in the form of tax breaks to training companies and subsidies to employers to take on an apprentice.

Comparative data can shed light on how much and in what ways governments, households and employers invest in VET. This can help compare the cost-effectiveness of different VET systems and approaches to delivery. For example, the effective use of work-based learning can reduce the costs of delivering programmes at the same time as promoting quality. When students can learn practice-oriented skills on equipment available in workplaces, school workshops typically need to provide only basic equipment to develop basic practice-oriented skills. Various financial flows between the public budget, employers and individuals are specific to VET – such as subsidies to employers that offer apprenticeships, or employer funded training levies. Data on transfer schemes and number of transfers are essential to enable meaningful international comparisons of expenditure.

Existing comparative data

Copy link to Existing comparative dataThe UOE data collection on education finance is built around three dimensions: sources of funds, the location where spending occurs and the type of expenditure. First, sources of funds include the public sector, international agencies, and private entities (households and other private entities, such as companies). Second, the location of service providers refers to the location where spending occurs. Spending on educational institutions includes spending on schools and universities, as well as non-teaching institutions (e.g. education ministries). Spending outside education institutions includes purchased books, computers, fees for private tutoring and student living costs. The third dimension refers to type of expenditure. Goods and services purchased include expenditure on educational core goods and services directly related to instruction and education (e.g. teachers, teaching materials, building maintenance, administration). Peripheral goods and services include ancillary services (e.g. meals, transport), and R&D. This dimension also breaks down current and capital expenditure and identifies financial transfers between the public and private sectors and between different levels of government within the public sector.

Available indicators include, for example, expenditure per full-time equivalent student in vocational vs. general upper secondary education, expenditure on staff per full-time equivalent student, or the share of expenditure on upper secondary VET institutions coming from households. Data are also available on various measures of expenditure as a percentage of GDP. In addition, information is available on transfers, including a qualitative data collection conducted in 2023 designed to improve information on financial flows in the context of VET (e.g. subsidies to companies that provide work-based learning). These are not yet published but will be included in the system-level data used for the PISA-VET Assessment.

Outcomes

Copy link to OutcomesThe issue

Copy link to The issueMeasures of different outcomes (including economic and social outcomes, as well as direct measures of skills) associated with vocational programmes, in comparison with other educational options, provide a key indicator of the effectiveness of VET. It is particularly useful to analyse data by various features of VET programmes (e.g. field-of-study, use of work-based learning) to explore which features are associated with the best outcomes. When interpreting data, it is also important to keep in mind the pathways that lead to vocational programmes and those pursued afterwards. For example, a vocational programme may enrol primarily graduates of general upper secondary education and focus on occupational skills, so the literacy and numeracy skills of graduates will reflect to a large extent their learning outcomes from general upper secondary education. Similarly, if a vocational programme leads primarily to higher level studies (e.g. higher vocational programmes or universities of applied sciences), looking simply at the economic and social outcomes and skills of those holding VET as their highest qualification will provide only a partial picture of the effectiveness of the programme (as in those cases many VET graduates may have moved on to and completed tertiary education and are therefore not part of the group of individuals holding a VET qualification as their highest qualification).

Existing comparative data

Copy link to Existing comparative dataData on economic and social outcomes are regularly collected through the LSO data collection, which allow to compare outcomes from VET with those associated with lower and higher levels of education, as well as general programmes. Economic outcomes systematically include employment, unemployment, and inactivity rates, as well as earnings. Breakdowns are available by age group and transition from school to work receives particular emphasis. In addition, data are available for European countries (through the European Labour Force Survey) on outcomes from VET depending on whether a person participated in some form of work-based learning during their last educational programme. In addition, the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) collects data on literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving skills. Currently available data focus on the highest qualification of individuals, but soon data will be available on the second highest or upper secondary level qualification of individuals in PIAAC and the European Labour Force Survey respectively.

Proposals for additional questions

Copy link to Proposals for additional questionsTo complement the available data described above, the PISA-VET Assessment will include a dedicated system-level questionnaire for countries to complete to fill the most important data gaps.

As general guidance, respondents will be asked the following:

If the response varies across programme types (e.g. different for 3-year programmes and 4 year-programmes at the same level) or across specific programmes/occupational areas (e.g. different for automotive technicians and for hotel receptionists), please provide separate responses as appropriate.

Please provide additional details in comments, if needed.

Choice and selection in VET

Copy link to Choice and selection in VET1. For upper secondary programmes, which factors constrain student choices of the type of programme?1

This question only applies to upper secondary programmes. It focuses on factors that constrain student choice regarding the type of upper secondary programme to be pursued – for example factors that determine, in addition to student choice, whether a student will pursue general or vocational upper secondary education, or whether they will pursue a 3-year vocational programme rather than a 2-year vocational programme.

Please select all that apply.

External examination (e.g. admission into certain upper secondary programmes requires passing an external examination or depends on results obtained at an external examination.)

School performance (e.g. entering programme A requires better grades in maths, while students with weaker grades may enter programme B – either because of a competitive admission system or because minimum thresholds beyond passing grades are set for certain programmes.)

Teacher / education institution recommendation

Type of lower secondary programme pursued (e.g. systems with early selection, when certain types of lower secondary programmes yield access only to vocational programmes)

Subject choices at lower secondary level (e.g. certain upper secondary programmes require the completion of the subject "higher mathematics" at lower levels)

For vocational programmes: availability of work-based learning (e.g. students who have not secured an apprenticeship contract with an employer cannot start a particular vocational programme and may need to pursue another type of programme)

Other (please specify below)

None

2. Which factors constrain student choices of the specific programme (focused on a given field of study or occupation)?

This question focuses on factors that are considered, beyond the choice of students, regarding the field of study or occupation targeted by the vocational programme.

Please select all that apply.

External examination (e.g. admission into certain upper secondary programmes requires passing an external examination or depends on results obtained at an external examination.)

School performance in specific subject areas (e.g. certain level of maths required for entry into a programme for electricians)

Teacher / school recommendation

Type of lower secondary programme pursued (e.g. systems with early selection, when certain types of lower secondary programmes yield access only to certain types of vocational programmes)

Subject choices at lower secondary level (e.g. certain upper secondary programmes require the completion of specific subjects at lower levels)

Availability of work-based learning (e.g. need to secure an apprenticeship contract prior to enrolment)

Other indicators of labour market relevance (e.g. skills forecasts)

Other (please specify below

3. Are there any incentives designed to guide student choice towards certain occupations? Please describe relevant initiatives.

The profile of VET learners

Copy link to The profile of VET learners4. Socio-economic background of VET vs. general education learners

Please provide data on the characteristics of VET vs. general education learners enrolled at <Level targeted by assessment>:

% of students with at least one tertiary-educated parent

% of foreign-born students

% of students with two foreign-born parents

% of students whose mother tongue is different from the language of instruction

Other (relevant to country context)

The delivery of VET

Copy link to The delivery of VET5. Where are programmes at <Level targeted by assessment> typically delivered?

Please indicate the share of programme duration delivered in each type of setting (shares need to sum up to 100).

School-based or college-based learning (…. %)

Work-based learning (…. %)

Inter-company training centres (…. %)

Other (please specify) (…. %)

School-based or college-based learning includes learning in classrooms as well as practical training spaces, such as workshops, in schools, colleges or similar types of VET institutions.

Work-based learning refers to some combination of observing, undertaking, and reflecting on productive work in real workplaces. This excludes simulated work environments, such as school workshops or practice companies.

Inter-company training centres exist in some countries. They are owned collectively by employers (e.g. a sectoral organisation) and typically involve classroom-like settings for theoretical instruction and/or workshops for the development of practical skills.

6. Which types of institutions provide vocational programmes at <Level targeted by assessment> in your country?

Please describe all institution types.

Table 9.1. Types of institutions

Copy link to Table 9.1. Types of institutions|

Institution type |

Share of students enrolled |

Delivery of general programmes |

Delivery of vocational programmes in multiple broad fields |

Delivery of vocational programme at multiple ISCED levels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

…% |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

|

|

…% |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

|

|

…% |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

Yes / Often / Rarely / No |

For each institution type, please specify:

% of students enrolled (i.e. VET students enrolled in this institution type / total number of students enrolled in vocational programmes at this level)

If this institution type also delivers general programmes at the same level

If this institution type delivers vocational programmes within one broad field or targets multiple broad fields. Broad fields of study are understood here as 2-digit categories in the ISCED-F framework.

If this institution type delivers vocational programmes at multiple levels. If the answer is “yes” or “often,” please specify which ISCED levels are typically covered.

Skills targeted by VET

Copy link to Skills targeted by VET7. Please describe at which level the learning outcomes targeted by a specific programme (e.g. electricians at <Level targeted by assessment>) are determined in your country.

National level

Sub-national level (please specify: ….)

A combination of national and sub-national level (please provide additional details)

Sub-national level may refer to regional or local level, groups of providers, or individual providers. If a combination of national and sub-national level applies, please specify details (e.g. providers can adapt 20% of the curriculum to local needs).

8. What the share of instruction time within VET institution-based settings is dedicated to general subjects?

<25%

25-49%

50-75%

>75%

Distinguishing between general and vocational subjects:

General subjects are not specific to a particular profession or field and may be the same as those taught in general programmes. Examples include mathematics, language, history, chemistry, or physics.

Vocational subjects focus on developing knowledge and skills that are specific to a particular profession or field. Examples include sales techniques or electronics.

General subjects with an explicit vocational focus (e.g. physics specifically designed for electricians) should be counted as half vocational and half general (e.g. if 10% of instruction time is dedicated to physics for electricians, 5% should be included in instruction time dedicated to general subjects and 5% in instruction time dedicated to vocational subjects).

Teachers and trainers

Copy link to Teachers and trainers9. What are the qualification requirements for teachers in VET in your country?2

Please specify the minimum level of qualification to be a fully qualified VET teacher, as relevant:

Level and type of formal education required

Relevant work experience (outside teaching), if appropriate (e.g. industry experience)

Other (please specify).

Please distinguish between different categories of teachers as appropriate in your country context: Teachers of general subjects in VET programmes; Teachers of vocational theory only; Teachers of vocational practice only; Teachers of vocational theory and practice. If there are various pathways to the teaching profession with different minimum requirements, please refer to the main pathway (or select two major pathways and describe them separately).

The minimum level of qualification of teachers refers to the requirements to become a fully qualified teacher (i.e. formal qualifications and attainment level, specific training or practical experience, competitive examinations, the successful completion of a probation period or induction programmes). For any of these characteristics to be considered as part of this level of qualification of teachers, they must be part of the core requirements to practice the teaching profession, and mandatory for all teachers (for example, competitive examinations or professional development activities that apply to all teachers without exception). Please describe pedagogical and occupational/field-specific requirements of applicable.

Fully qualified teacher means that a teacher has fulfilled all the training requirements for teaching (a certain subject) and meets all other administrative requirements according to the formal policy in a country.

For the purposes of this data collection, the category of VET teachers excludes in-company trainers responsible for work-based learning in VET.

10. What requirements must companies satisfy to provide work-based learning to students as part of a vocational programme?

Please specify requirements, which may include for example relevant vocational qualifications of staff in the company (in particular in-company trainers), the establishment of a training plan with clearly defined learning outcomes, and any other requirements regarding the company.

11. What types of “training the trainers” initiatives are available to in-company trainers in your country in the context of work-based learning for VET students?

In-company trainers are individuals within companies who are responsible for training vocational students during the work-based learning part of the programme.

Mandatory training and/or qualification (e.g. mandatory training in pedagogical skills). (Please specify duration)

Optional training. (Please specify duration)

No targeted training available.

Governance

Copy link to Governance12. Which ministries are responsible for VET at <Level targeted by assessment>?

Please describe which ministries (and dedicated agencies, if relevant) take responsibility for VET (and for which aspects/parts).

13. How are social partners engaged in VET at <Level targeted by assessment>?

Please describe how social partners are involved in the design and delivery of VET in your country and their particular role. You may describe involvement at national, regional, sectoral, local, and institutional level separately, as appropriate.

References

[7] BIBB (2021), Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2021, Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung, Bonn, https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/bibb-datenreport-2021.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2022).

[13] Cedefop (2023), Teachers and trainers in a changing world, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/country-reports/teachers-and-trainers-in-a-changing-world (accessed on 13 July 2023).

[5] Cedefop (2014), “Attractiveness of initial vocational education and training: identifying what matters”, Research Paper, No. 39, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Luxembourg, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/5539_en.pdf.

[3] OCAS (2023), Electrician / Electrical - Ontario Colleges, https://www.ontariocolleges.ca/en/programs/professions-and-trades/electrician-electrical (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[10] OECD (2023), Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e13bef63-en.

[6] OECD (2022), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[4] OECD (2022), Pathways to Professions: Understanding Higher Vocational and Professional Tertiary Education Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[12] OECD (2022), Preparing Vocational Teachers and Trainers: Case Studies on Entry Requirements and Initial Training, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c44f2715-en.

[11] OECD (2022), The Landscape of Providers of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/publications/the-landscape-of-providers-of-vocational-education-and-training-a3641ff3-en.htm.

[1] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed, OECD, https://doi.org/10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en.

[8] OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en.

[9] OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

[2] SDBB (2023), Berufsberatung, https://www.berufsberatung.ch/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).