This chapter defines employability skills as assessed by PISA-VET and elaborates the framework for employability skills that has been designed for the Development Phase of the project, including descriptions of the competencies and constructs to be assessed. It presents and explains the dimensions reflected in PISA-VET’s employability skills domains and how these will be assessed and provides several sample items with descriptions of task characteristics. The chapter also discusses how student performance in the employability skills is measured and reported against proficiency levels and scales.

PISA Vocational Education and Training (VET)

7. Employability Skills

Copy link to 7. Employability SkillsAbstract

Introduction to Employability Skills in PISA-VET

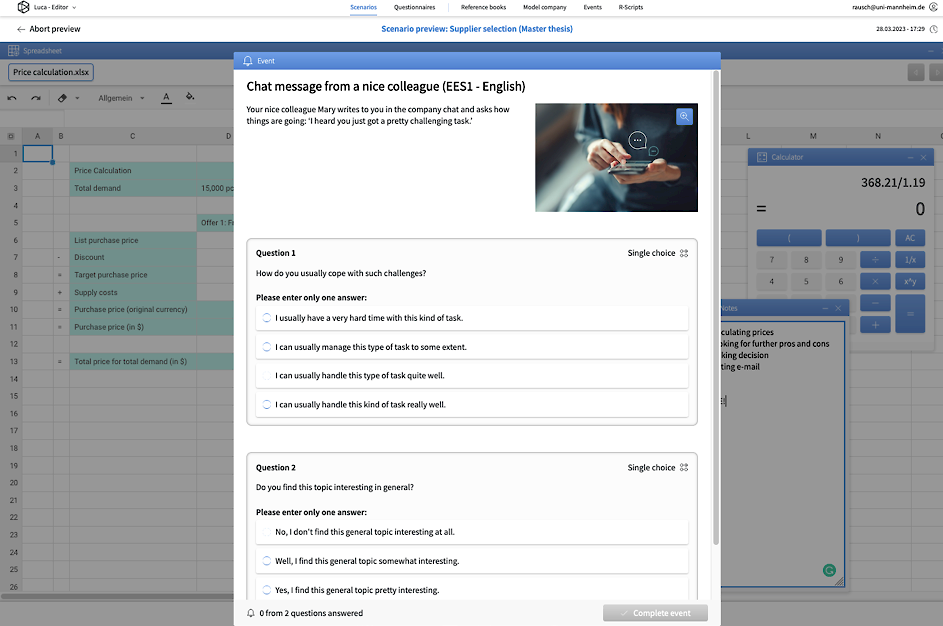

Copy link to Introduction to Employability Skills in PISA-VETPISA-VET must reflect today’s workplaces in their complexity and dynamic nature. As mentioned in Chapter 1, the changing world of work in the 21st century is being profoundly shaped by several megatrends, including the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the advent of Artificial Intelligence, and the green and digital transformation. These trends are fundamentally alerting the nature of work and employment and shifting the global economy, society as well as consumer and employee demands (Frey and Osborne, 2017[1]; McClelland, 2020[2]; World Bank, 2018[3]). Therefore, labour markets are constantly evolving, requiring individuals to engage in lifelong learning and master new situations within their occupation or even across different occupations. The prerequisite for achieving this mastery, even in job market situations that we may not yet know will exist a decade from now, is through possessing so-called employability, i.e. a set of transversal and foundational skills that are fundamental for success in the workplace and for navigating a changing labour market. The significance of such employability skills is paramount for the workplace but extends even further: they are equally valuable for leading a successful and fulfilling social and civic life.

The topic of employability skills needed for the future of work has been of interest to policy makers and practitioners alike for several years, and the role of employability skills for students and adults in successful participation in modern society has been receiving increasing attention in several international surveys. PISA is one such study that has looked at the importance of employability skills in student populations. The most recent PISA report (OECD, 2019[4]) found that students who possess strong employability skills, such as problem solving, critical thinking, and communication, are more likely to perform well in all three subject areas and exhibit higher levels of well-being. PIAAC is another OECD study that has examined the importance of employability skills in the context of the working adult population. PIAAC assesses the proficiency of adults in key areas, such as literacy, numeracy, and problem solving in technology-rich environments. The most recent PIAAC report (OECD, 2019[5]) found that adults with stronger employability skills are more likely to have higher levels of employment, earn higher wages, and have better health outcomes. Furthermore, the OECD’s Study on Social and Emotional Skills (SSES) (OECD, 2021[6]) identified five key employability skills that help individuals to be successful in the workplace, namely task performance, emotional regulation, collaboration, open-mindedness, and engaging with others. Overall, these studies not only emphasise the relevance of employability skills for academic and career achievements but also highlight the individual benefits for personal growth and overall well-being associated with these skills in both student and adult populations.

PISA-VET includes employability skills derived from these OECD frameworks. These employability skills can be defined as a broad set of skills and abilities that are essential for success in any occupational field (a more detailed definition can be found in the next section). Without a strong foundation in these skills, individuals may struggle to acquire specialised skills or adapt to changing job requirements and will, thus, not be well-prepared to master the workplaces of the future. Therefore, developing employability skills through VET programmes and integrating them nationwide across occupational areas is critical for ensuring employability and success in the modern workforce as well as individual well-being. The assessment of employability skills in PISA-VET strives to provide valuable insights into their development within VET programmes, predict future employability, and facilitate comparisons both within specific occupations and across diverse contexts.

The purpose of this chapter is to define employability skills as understood by PISA-VET and highlight their relevance in the modern workforce. It also aims to elaborate the framework for employability skills that has been designed for the Development Phase of the project and explain the selected domains and the proficiency levels of employability skills in PISA-VET. Finally, a mode for the assessment of employability skills is proposed.

Defining Employability Skills

Copy link to Defining Employability SkillsEmployability skills are a set of competencies that are relevant across occupational areas for success in the workforce and beyond. Employability skills are characterised by the following hallmarks: a) they are necessary for an individual’s full integration and participation in the labour market, education, and training, as well as in social and civic life; b) they are highly transferable to other contexts; and c) they are learnable, and thus subject to the influence of policy (OECD, 2019[4]). In other words, these skills enable individuals to adapt to new technologies and rapidly changing workplaces (OECD, 2019[5]) and prepare individuals for future learning and help them master situations at work that may not even be relevant today but will be in the future. They are crucial for individuals to navigate the rapidly changing labour market and succeed in an increasingly complex and dynamic world of work. Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of employability skills in education and the workforce. For instance, PISA and PIAAC have shown that individuals who possess strong employability skills are more likely to perform well academically, have better job prospects, and earn higher wages. Research studies have also found that employability skills are positively associated with job performance, job satisfaction, and career advancement (OECD, 2013[7]; 2019[4]; 2019[5]), which in turn contribute to individuals’ integration into society, resilience, personal growth, and well-being (Vanhercke, De Cuyper and De Witte, 2016[8]).

There are many different terminologies in use for what this chapter calls “employability” skills, and the term “employability skills” has been used synonymously to foundational skills, transversal skills, transferable skills, cross-domain skills, generic skills, core skills, key competencies, soft skills, and 21st-century skills. For example, PISA defines key competencies as the set of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values needed for individuals to succeed in the 21st century. Similarly, PIAAC emphasises the importance of transferable skills for success in a constantly evolving labour market. Albeit in slightly different terminology, the OECD's PISA (OECD, 2019[4]) and PIAAC (OECD, 2013[7]) studies regard employability skills as a combination of cognitive and non-cognitive skills, including problem solving, critical thinking, communication, collaboration, literacy, numeracy, information and communication technology (ICT) literacy, and more. These skills are not limited to specific school subjects, occupations, or industries and can be applied across a variety of contexts. In their report “Enhancing Employability” for the G20 Employment Working Group, the OECD, the ILO (International Labour Organization), and the World Bank (OECD, ILO and The World Bank, 2016, p. 3[9]) define transferable skills as “skills that can be used in most occupations – e.g. problem solving, team working, etc. – including core skills such as literacy and numeracy, which are essential in all occupations and required for learning new skills.” Furthermore, these ‘skills that are relevant to labour market needs and transferable to different sectors and technologies’ (p. 7) are also referred to as adaptability and are supposed to enhance the employability of employees and job seekers. Like the report “Enhancing Employability”, the focus of PISA-VET is the improvement of individuals’ employability and their capacity to successfully seek and maintain employment in the future. The term “employability skills” is chosen to best reflect the context of PISA-VET, and essentially includes skills that are not occupation-specific but relevant across occupations and sectors (albeit at different levels/intensity).

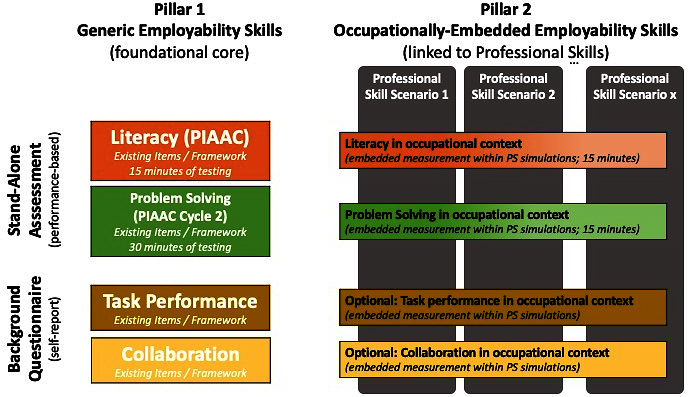

For success in the workforce, employability skills are essential, both by themselves and in close interplay with occupation-specific skills. However, a key question is whether these employability skills should be regarded as domain-general (i.e. independent of occupation-specific knowledge and competencies) or domain-embedded (i.e. including occupation-specific knowledge and competencies). One main advantage of the understanding of employability skills as domain-general is that it not only enables comparability across different occupations but also allows for the measurement of a general capacity to navigate even in workplaces that do not yet exist. However, completing work tasks and solving complex problems in a particular domain always require domain-specific knowledge and skills. Therefore, employability skills are always, at least to some extent, intertwined with occupation-specific skills (Humburg and Velden, 2013[10]). PISA-VET considers both considerations and includes a generic assessment part of employability skills and a domain-embedded assessment part to capture the full breadth of both the generic and the domain-nature of employability skills as will be outlined in more specific terms throughout this chapter. While there are highly domain-specific approaches that are represented within the context of occupational skills, the primary emphasis here deliberately focuses on the overarching, non-occupation-specific aspects of employability skills and their integration within occupation-specific contexts.

The topic of employability skills is not only limited to whether they are domain-general or domain-embedded. An associated aspect under discussion is the time frame for defining these skills, which can be either short-term (aimed at being employable now) or long-term (aimed at becoming or staying employable). However, on the basis of responses from more than 900 employers in nine different European countries, Humburg et al. (2013[10]) conclude that “the skills that are needed to ensure short-term employability are no different from the skills that are needed to increase employability in the long run.”

The core employability skills selected for PISA-VET cut across occupational areas and are essential for all the selected occupations, while also enabling international comparability. As such, four core employability skills are identified for PISA-VET: literacy, problem solving, task performance, and collaboration. Other employability skills may also be important for certain occupations, such as communication skills in healthcare and tourism and hospitality, and numeracy skills for electricians, and these have been integrated within the frameworks for the occupational area assessments (see previous chapters). The four core employability skills were identified as the most relevant by policy makers and stakeholders from participating countries, based on extensive existing knowledge of their relevance from research and policy making (as discussed in Chapter 1). Moreover, test constraints were considered when selecting the employability skills to be included in PISA-VET, as only a small core of the most relevant employability skills could be assessed in the time available. The selected employability skills represent a diverse set of skills that tap into both cognitive and non-cognitive aspects. They are closely aligned with existing well-validated scales from PISA, PIAAC, and SSES. Detailed definitions of these skills will be presented in the section on assessment.

Organising the Domains of Employability Skills

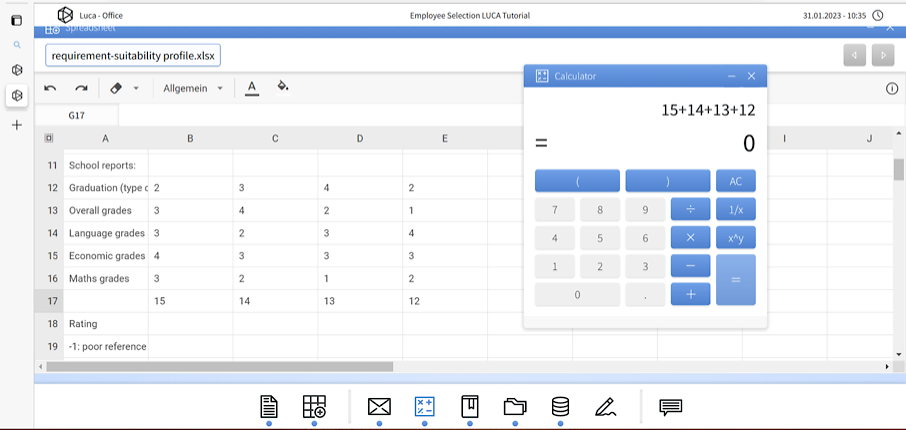

Copy link to Organising the Domains of Employability SkillsThe four employability skills chosen for PISA-VET, literacy, problem solving, task performance, and collaboration, have been extensively studied in previous OECD assessments. PISA-VET therefore benefits from the in-depth conceptual work already completed on these assessments. To this end, the approach taken towards the employability skills included in PISA-VET is to use the existing OECD frameworks for organising the selected domains. This involves PIAAC Cycle 1 (and Cycle 2) for literacy, PIAAC Cycle 2 for problem solving, and the SSES for both task performance and collaboration.

PISA-VET will utilise these existing frameworks and adapt them to the VET context to provide the conceptual background of the four core employability skills. In the sections below information on each of the four core employability skills is presented, including their definition, relevance to VET, (sub-)processes involved in the employability skill, proficiency levels, relations to other relevant frameworks, and its occupation-specific modulation. Acknowledging that employability skills beyond literacy, problem solving, task performance, and collaboration can also be of paramount importance for specific occupations, a later section of this chapter will briefly discuss a set of further skills that are not included as direct assessments in PISA-VET. These further skills were discussed for potential inclusion in assessment but had to be excluded, mainly due to concerns related to testing time and potential low data validity from test taker fatigue.

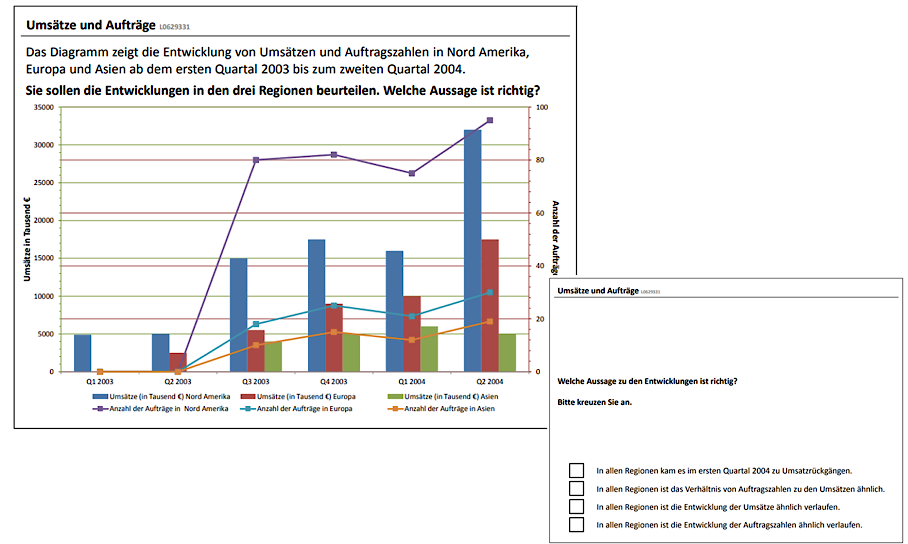

Literacy

Copy link to LiteracyThis section aims at summarising the literacy framework, as defined by PIAAC and its relevance to the area of VET as a foundational employability skill. It is based to a large extent on the PIAAC Cycle 2 Literacy Framework (OECD, 2021[6]) that was developed by the members of the PIAAC Cycle 2 Literacy Expert Group. Literacy skills are fundamental for individuals to participate fully in society, access opportunities, pursue education and employment, communicate effectively, and continue learning and growing throughout their lives. Literacy serves as a gateway to knowledge, empowerment, and personal development, contributing to both individual success and societal progress.

Definition of Literacy

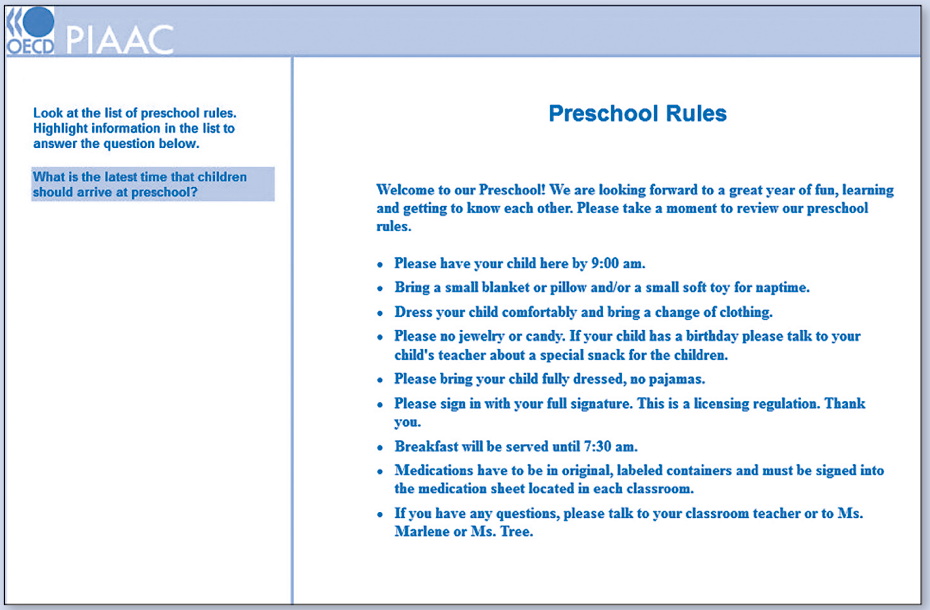

Copy link to Definition of LiteracyPIAAC defines literacy as the ability to "access, understand, evaluate and reflect on written texts to achieve one's goals, to develop one's knowledge and potential and to participate in society" (OECD, 2021[6]). In its most literal sense, literacy refers to one's ability to comprehend and use written sign systems. Literacy encompasses a range of skills, from decoding written words and sentences to comprehending, interpreting, and evaluating complex texts. However, it does not involve the production of text (writing). Information on the skills of adults with low proficiency levels is provided by assessing reading components that cover text vocabulary, sentence comprehension, and passage fluency.

Relevance of Literacy to VET

Copy link to Relevance of Literacy to VETPIAAC views key competencies as "general" in the sense of being relevant to all members of the working population and across all fields of economic and social activity (OECD, 2021[6]). It further recognises that "while the economic and social importance of 'specific' competencies (skills related to specific rather than general-use technologies, discipline-specific or occupation-specific skills) is not denied, they are intentionally defined to be outside the scope of key competency frameworks" and thus not included in the PIAAC literacy framework (in PISA-VET, both aspects are considered for the assessment as outlined in a later section of this chapter).

Literacy provides the foundation for effective participation in society and literate individuals can make use of a broad diversity of written materials in the service of a wide range of activities and are knowledgeable of the cultural standards of their communities of practice. Thus, literacy is a necessary, but not sufficient, skill for performance in occupational areas where written communication dominates education and training and continuing education. As an employability skill in the PISA-VET framework, it allows individuals to progress towards applying literacy within their occupational areas of interest.

For instance, an automotive technician will need to read through technical manuals and understand the requirements and processes in the maintenance or repair of a car. An electrician will need to read and understand installation requirements, wiring diagrams, and operating instructions. Business and administration professionals will need to comprehend written information and graphical representations, such as evaluating delivery conditions based on international standards. Healthcare workers will habitually engage in reading scientific publications or medical procedures to stay updated on relevant topics and unfamiliar diseases. In tourism and hospitality, literacy is also a strong requirement, as employees will need to both converse with customers in oral and written form, and understand documentation, procedures or regulations that are applicable – for example, reading and understanding documentation relating to checking-out procedures and guest’s departure. This intimate relationship between literacy as an employability skill and its role in the various occupational areas is further illustrated below.

In addition to being directly relevant for their target occupations, literacy skills are also crucial to VET learners to adapt to the constant change that they experience at the workplace. As highlighted above, literacy skills are important prerequisites for engaging in further learning. Evidence shows that adults who hold a VET qualification are strongly exposed to automation in their jobs and are therefore likely to need to adapt and update their skills (OECD, 2020[11]). Without solid literacy skills they risk not being able to adjust to new working methods and technologies or not being flexible enough to change sectors or occupation – creating a risk that they leave the labour market or end up in low-quality jobs.

It needs to be acknowledged that literacy skills, as with the other employability skills, are not only developed through the VET programmes that the learner participates in. As mentioned in Chapter 1, employability skills are developed in a variety of settings - including settings outside of the education and training system - and are accumulated over the life course. In particular for literacy skills, early stages of education are important. The literacy skills of the learners targeted by PISA-VET are likely to reflect to a large extent the skills they developed even before entering their VET programme. As such, the assessment will not derive conclusions about how well VET does in equipping learners with literacy skills, but rather about how well VET together with the earlier stages of education is at ensuring that all learners have the literacy foundations needed in today’s labour market.

Processes, content and contexts involved in Literacy

Copy link to Processes, content and contexts involved in LiteracyThe literacy domain in PIAAC encompasses cognitive processes, content, and social context. These dimensions are also helpful in defining the proficiency levels for literacy.

Cognitive processes involve accessing text, understanding its meaning, and evaluating its quality. Accessing text includes identifying relevant texts and locating information within them. Understanding involves comprehending written words, integrating text information with prior knowledge, and handling multiple texts with inconsistent or conflicting information. Evaluating entails critically assessing the accuracy, soundness, and task relevance of the information, considering both the content and the source.

Content refers to the texts, tools, knowledge, and cognitive challenges that authors use to convey ideas. It includes different text types (description, narration, exposition, etc.), text formats (continuous or non-continuous), text organization (amount of information and density), and text sources (single or multiple texts).

Social contexts represent situations where reading activities are normally situated and may serve various purposes, from personal to professional and civic with professional contexts being the one that PISA-VET will be looking at. These refer to the different situations in which individuals must read: i) work and occupation, ii) personal use, and iii) social and civic context. For PISA-VET, the focus will be on situations in work and occupation.

Proficiency Levels of Literacy

Copy link to Proficiency Levels of LiteracyProficiency scales, also known as reporting scales, are important components of large-scale international assessments, enabling comparisons across countries and providing insights into student performance. In addition to defining the numerical range of the proficiency scale, it is also possible to define the scale by describing the competencies typical of students at points along the scale. Thus, the described proficiency scales describe what students typically know and can do at given levels of proficiency.

Table 7.1 shows the PIAAC literacy described scale from Cycle 1. Across the 32 participating Cycle 1 OECD countries, the average literacy score was 266.2 (Proficiency Level 2) with a standard deviation of 47 points. As the PIAAC literacy framework was updated for Cycle 2, this scale will be updated for reporting. Thus, the scale below is shown for reference only and PISA-VET will rely on Cycle 2.

Table 7.1. PIAAC Literacy Described Scale

Copy link to Table 7.1. PIAAC Literacy Described Scale|

Proficiency Levels |

Score Range |

Types of tasks completed successfully in each level of proficiency |

|---|---|---|

|

5 |

Equal or higher than 376 points |

At this level, tasks involve searching, integrating, and synthesizing information from multiple dense texts. Respondents are expected to evaluate arguments based on evidence and apply logical and conceptual models. They need to assess the reliability of sources and select pertinent information. Tasks may also require understanding subtle cues, making advanced inferences, and applying specialized knowledge. |

|

4 |

326 to less than 376 points |

At this level, tasks involve integrating and synthesizing information from complex texts, including continuous, non-continuous, mixed, or multiple types. Respondents must perform multiple-step operations and make complex inferences using background knowledge. Understanding specific non-central ideas and interpreting subtle evidence or persuasive relationships are often required. Respondents must consider conditional information and navigate competing information in these tasks. |

|

3 |

276 to less than 326 points |

Texts at this level are dense or lengthy, including continuous, non-continuous, mixed, or multiple pages. Understanding text and rhetorical structures is crucial, particularly in navigating complex digital texts. Tasks involve identifying, interpreting, and evaluating information, often requiring different levels of inference. Respondents must construct meaning from larger portions of text and perform multi-step operations to formulate accurate responses. Filtering out irrelevant content is often necessary. While competing information may be present, it is not more prominent than the correct information. |

|

2 |

226 to less than 276 points |

At this level, texts can be digital or printed, including continuous, non-continuous, or mixed types. Tasks involve matching information in the text, sometimes requiring paraphrasing or basic inferences. There may be competing information to consider. Some tasks require the respondent to: • cycle through or integrate two or more pieces of information based on criteria • compare and contrast or reason about information requested in the question • navigate within digital texts to access and identify information from various parts of a document. |

|

1 |

176 to less than 226 points |

Tasks at this level involve reading short digital or print texts, including continuous, non-continuous, or mixed formats, to find a specific matching or synonymous piece of information mentioned in the question or directive. Some tasks may require entering personal information on a document. There is minimal or no competing information. Simple cycling through multiple pieces of information may be needed for certain tasks. Basic vocabulary recognition, sentence comprehension, and paragraph reading skills are expected. |

|

Below Level 1 |

Below 176 points |

Tasks at this level involve reading short texts on familiar topics to find specific information. There is usually no competing information, and the requested information is identical to what is mentioned in the question or directive. The respondent may need to locate information in short continuous texts, but it can be treated as non-continuous for locating purposes. Basic vocabulary knowledge is sufficient, and understanding sentence or paragraph structure is not required. Tasks below Level 1 do not involve specific features of digital texts. |

Source: PIAAC Cycle 1 assessment framework; (OECD, 2012[12]).

Related Frameworks pertinent to Literacy

Copy link to Related Frameworks pertinent to LiteracyThe PIAAC Cycle 2 Literacy Framework (OECD, 2021[6]) represents an evolution of the role of literacy in the adult population (16–65 year-olds) that started with the International Adult Literacy Study (IALS; 1994-1998). The framework has undergone several iterations, including the Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey (ALL; 2003-2008), the Survey of Adult Skills Cycle 1 (PIAAC; 2008-2018), and the ongoing implementation of the Survey of Adult Skills Cycle 2. The PIAAC Cycle 2 framework summarises and organises the evolution of the literacy construct in four areas (p. 24):

A reduction of the number of separate domains of literacy assessed: IALS (OECD/Statistics Canada, 2000[13]) measured literacy through separated scales of prose, document, and qualitative literacy. This aspect remained in ALL (Murray, Clermont and Binkley, 2005[14]) when quantitative literacy was replaced by numeracy. Quantitative literacy in IALS had a sole focus on functional, arithmetic calculation embedded in printed materials. In comparison, numeracy is a broader measure, covering a wider breadth of mathematical skills, purposes, and content. Furthermore, it depends less heavily on reading skills (Tout, 2020[15]). PIAAC Cycle 1 (OECD, 2012[12]) introduced literacy as a single, global construct, which remained in PIAAC Cycle 2 (OECD, 2021[6]).

An expansion of the range of text types covered in the assessment: PIAAC eliminated the differentiation between the reading of prose and document texts and expanded the range of text to include digital and electronic texts.

An increasing emphasis placed on evaluation and evaluating metacognition as cognitive strategies required for effective reading: IALS/ALL emphasised "matching" strategies (locating, integrating, and generating understanding) with PIAAC Cycle 1, expanding it towards evaluation and reflection and PIAAC Cycle 2 expanding evaluation further into the evaluation of the accuracy, soundness, and task relevance of a text concerning both its source and content.

The disentangling of the description and specification of cognitive strategies from questions of task difficulty: IALS/ALL frameworks combined cognitive strategies and the factors affecting task difficulty, while PIAAC views these independently. It conceived task difficulty as being driven by the stimulus text(s) features, the formulation of the question/task description and the interaction of the text and question/task description.

Additionally, there has been an increasing interest in providing more detailed information about adults with poor literacy skills. In response, PIAAC Cycle 1 introduced the assessment of reading components – the basic set of decoding skills essential for extracting meaning from written texts: knowledge of vocabulary (word recognition), the ability to process meaning at the level of the sentence, and fluency in reading passages of text – with PIAAC Cycle 2 assessing only the sentence meaning and passage fluency dimensions (OECD, 2021[6]).

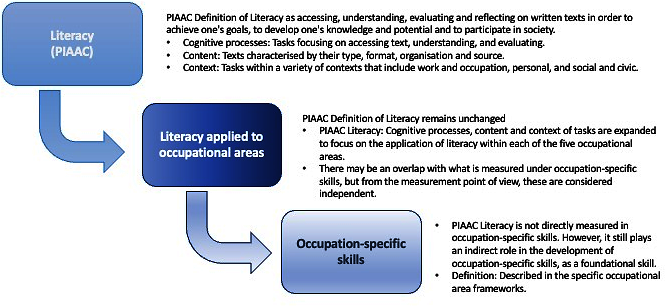

Occupation-Specific Modulation of Literacy

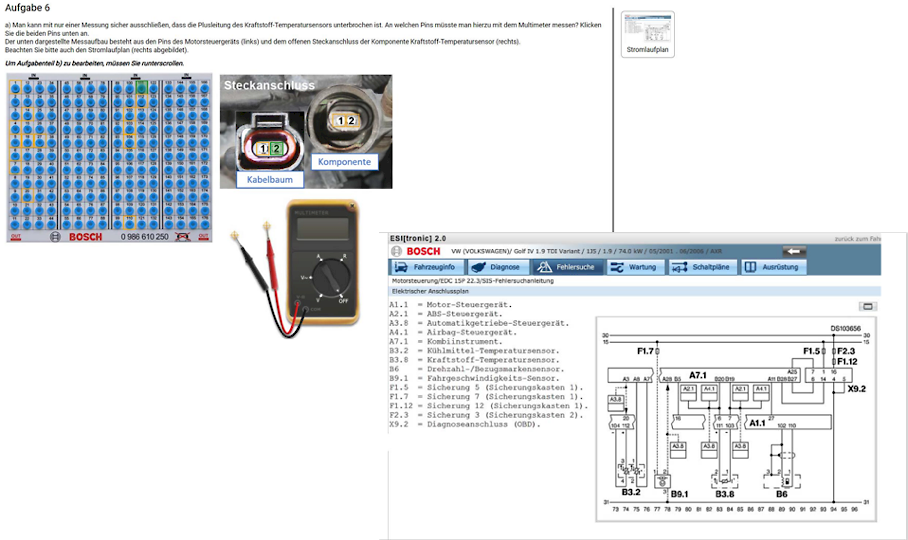

Copy link to Occupation-Specific Modulation of LiteracyThe previous section mentioned that the PIAAC framework recognises 'specific' competencies but intentionally leaves them out of the key competency frameworks. This aligns with the proposed PISA-VET theoretical skills continuum (Figure 7.1). In this continuum, employability skills function as a prerequisite for individuals as they proceed from securing foundational level competency towards applying literacy in one of PISA-VET’s five occupational areas and then onwards to demonstrate occupation-specific skills in one of these occupational areas. A key issue for PISA-VET is the point along this continuum at which the skills being measured are no longer the application of employability skills in the occupational area but are rather their direct application as an occupation-specific skill. This aspect and how a generic assessment of literacy as done in PIAAC as well as an extension of this as literacy applied in occupational domains within PISA-VET is discussed further in a later section of this chapter.

Both as a generic employability skill and as a skill that is occupationally embedded, literacy is related to the five vocational domains covered in PISA-VET. The diagnostic skill of automotive technicians cannot be separated from their abilities to understand what the client wants and to consult the relevant technical repository, in order to understand how a specific technical ensemble is diagnosed, repaired, or maintained. An automotive technician needs to diagnose (which is impossible without understanding the target of the diagnosis, i.e. being able to read through the relevant technical documentation), repair (which is not possible without continuously consulting technical documentation, especially in non-routine cases), maintain or inspect (e.g. write off for service) mechanical parts or vehicles. All these processes and activities require literacy, especially related to technical literature.

Figure 7.1. The Literacy Continuum towards Occupation-Specific Skills

Copy link to Figure 7.1. The Literacy Continuum towards Occupation-Specific Skills

Electricians may need to assess and diagnose technical equipment - for which they need to read and understand installation requirements and technical guidance documents, as well as wiring diagrams and operating instructions. They also need to assemble and install and to inspect, test and maintain electrical equipment - for which they need to read and understand data generated by testing equipment, and need to interpret associated reports, as well as read and understand inspection and commissioning procedures. In general, to perform these activities, electricians need to read and understand manufacturer’s instructions, wiring diagrams and layout drawings, to read and understand outputs of the various instruments they work with, and to read and understand (in order to follow them) industry procedures, regulations, or rules with respect to functionality and safety.

Employees working in business and administration need to use literacy in identifying needs for action (e.g. identifying the requirements for a new supplier by processing written information from internal and external business communication and retrieving information from databases), process quantitative and qualitative data (e.g. applying algorithms such as calculating bid prices and interpreting written information and graphical representations regarding delivery conditions based on the comparison with international standards), and communicate with internal and external stakeholders (e.g. understanding and evaluating written and oral communication from a customer).

Employees working in health care need literacy in activities and processes such as assessing needs and plan healthcare (e.g. documentation of past illness and related to planning intervention for a specific illness need to be consulted), supporting and enhancing clients’ quality of life (e.g. clients may need to be counselled and supported, and understanding their written case history, as well as their specific personal circumstances will require literacy), providing and supporting treatment and interventions (e.g. preparing for a case conference to assist the assessment of patients’ needs).

Finally, literacy will come into play in tourism and hospitality settings, including in activities such as checking in (e.g. reading a reservation document and understanding hotel’s policy and procedure for issue room keys to guests and providing directions to allocated rooms and information about hotel services and facilities) or checking out (e.g. reading and understanding documentation relating to checking-out procedures and guest’s departure) a customer. Table 7.4. presents examples of occupation-specific modulations of literacy to highlight the relevance of this employability skill within the five occupational areas under consideration in PISA-VET.

Summary

Copy link to SummaryLiteracy, as defined by the PIAAC framework, is a foundational or employability skill essential for participation in all aspects of society. More importantly, it serves as the basis for developing additional skills within occupational areas. In the context of PISA-VET, higher literacy levels are most likely linked with better use of these skills within occupational settings and more successful engagement in upskilling or reskilling.

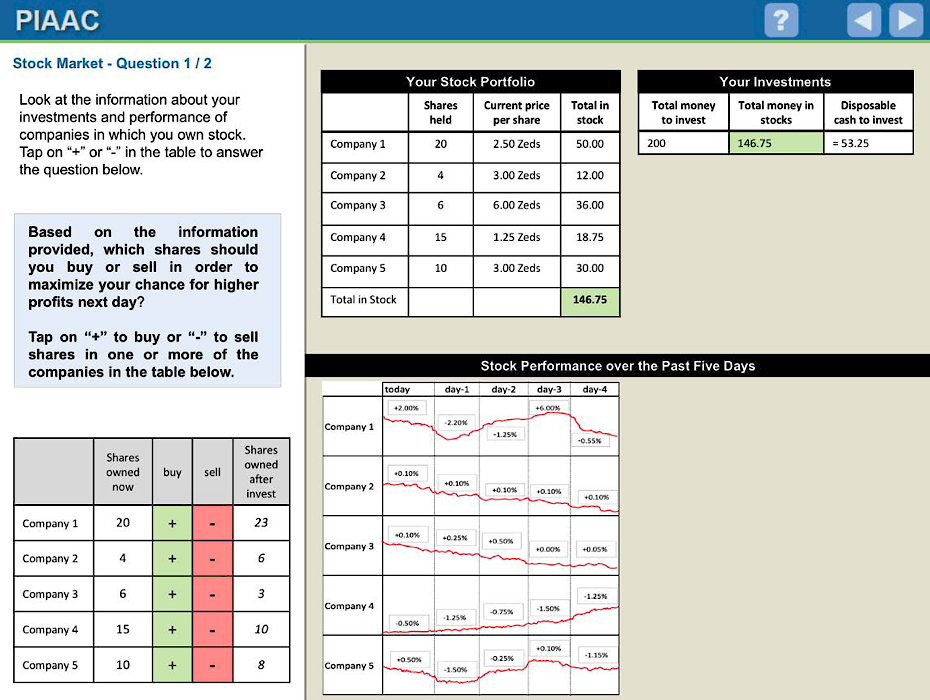

Problem Solving

Copy link to Problem SolvingThis section aims at defining problem solving, based on existing assessment frameworks: PIAAC Cycles 1 (“problem solving in technology rich environments”; (OECD, 2009[16])) and 2 (“adaptive problem solving”; (OECD, 2021[6]); PISA 2003 (“mathematical problem solving”; (OECD, 2003[17])) and 2012 (“creative problem solving”; (OECD, 2013[18])). Most of this summary is driven by the latest conceptualisation of problem solving, i.e. “adaptive problem solving”, as defined by the PIAAC Cycle 2 (OECD, 2021[6]). This broad inclusion of problem solving across several large-scale assessments is driven by the notion that problem solving skills are essential in the personal, social, and professional lives of adults. They enable individuals to approach complex situations with confidence, creativity, and resilience, allowing them to overcome obstacles and achieve desired outcomes in both personal and professional domains. This section explains the relevance of the concept to the area of VET as an employability skill.

Definition of Problem Solving

Copy link to Definition of Problem SolvingPIAAC Cycle 2 defines problem solving as “the capacity to achieve one’s goals in a dynamic situation, in which a method for solution is not immediately available. It requires engaging in cognitive and metacognitive processes to define the problem, search for information, and apply a solution in a variety of information environments and contexts” (OECD, 2021[6]). In its most basic sense, problem solving is centered around contexts that demand non-routine solutions, and some difficulties for the one facing them, irrespective of any content-specific domain and across occupations.

The latest PIAAC Cycle 2 approach emphasises the following components of this definition:

Capacity: Problem solving is a complex proficiency, and its application to a problem is a goal-directed activity that may result in various degrees of success or performance in handling the problem.

Adaptivity: Problem solving takes place in complex environments that force the process to be a dynamic and not a static sequence of pre-set steps, thus forcing problem solvers to remain open, to monitor the problem environment, and to adapt their approach constantly.

Cognition and metacognition: Problem solving involves cognitive performance to organize and integrate information into a mental model, as well as metacognition for self-monitoring and self-reflection on progress. These two components are interconnected and challenging to separate.

Process: Problem solving is a three-stage process containing problem identification (i.e. “problem finding”), actions to bridge the gap between the initial point to the desired goal (i.e. “problem shaping”), and the actual performance of actions until a satisfactory outcome is achieved. These stages can occur in different orders or even simultaneously.

Environment: Problem solving is typically embedded in information-rich physical, social, and digital environments, emphasizing the particular importance of digital literacy. Digital environments especially are critical in this respect. PIAAC Cycle 1 has already recognized problem solving in technology-rich environments, highlighting the integration of digital skills in today’s problem solving scenarios. Consequently, competent problem solvers are expected to be able to deal with problem solving situations that are digitally embedded.

Relevance of Problem Solving to VET

Copy link to Relevance of Problem Solving to VETProblem solving skills are essential in the personal, social, and professional lives of adults. Problem solving has been linked with positive individual-level and societal level outcomes, as it describes at its core “the ability to quickly and flexibly adapt to new circumstances, learn throughout life, and turn knowledge into action” (OECD, 2021[6]). Problem solving skills have been found in modern economies to be most important for a worker to be successful (OECD, 2015[19]).

PIAAC views problem solving as a general key competency, i.e. it emphasises the empirically underscored assumption that this competency is relevant to all members of the working population and across all fields of economic and social activity (OECD, 2021[6]). Problem solving is thus ostensibly defined in contrast (and opposition) with specific competencies, i.e. skills that are discipline-specific or occupation-specific. The importance of such specific competencies is not denied, but on the contrary emphasised; however, they were not included in the PIAAC framework: they are intentionally defined to be outside the scope of key competency frameworks (OECD, 2021[6]). This fundamental notion of how problem solving is defined is rooted in its pivotal role in current and future employability across diverse contexts. In PISA-VET, both generic and occupationally embedded aspects of problem solving are considered for the assessment as outlined in a later section of this chapter. In this, problem solving is considered to be foundational and essential for effective participation in society and the labour market but is not sufficient for performance in specific professional settings. In such specific professional settings, aside from more specialised skills, problem solving itself may be challenged by the context: Specialized information may mark the problem environment, and specialised reasoning may mark the stages of the problem solving process.

Some examples of how problem solving is inherently bound into the focal occupational areas follow here. An automotive technician may need to identify the causes of automotive malfunction and derive appropriate repair actions, such as removing a rusted bolt with a snapped-off head. An electrician will need to identify and diagnose electrical breakdowns and make informed recommendations to customers or clients. For employees in business and administration roles, typical office work will encompass significant non-routine problems, exceptions, errors, and innovative tasks that include problem solving, especially now that many routine work processes have been automated or outsourced. In healthcare, the essence of intervention is that the problem needs to be understood beforehand – diagnosing the situation and deciding on the appropriate course of action may often be literally the difference between life and death. In tourism and hospitality, adhering to established procedures while adapting services to specific situations and customer needs defines excellency. This relationship between problem solving as an employability skill and success in occupational areas is further illustrated in the section on occupation-specific modulation.

In fact, in a labour market that is exposed to digitalisation and automation, including in the five occupational areas under consideration in PISA-VET, problem solving skills become increasingly important. Complex problem solving is identified as one of the skills that are least exposed to automation (Lassébie and Quintini, 2022[20]) that is, with a low probability that technology will be able to replace humans in carrying out tasks that require extensive problem solving skills. As such, problem solving skills are key for VET learners who are or will be working in an increasingly digital labour market.

Processes, content and contexts involved in Problem Solving

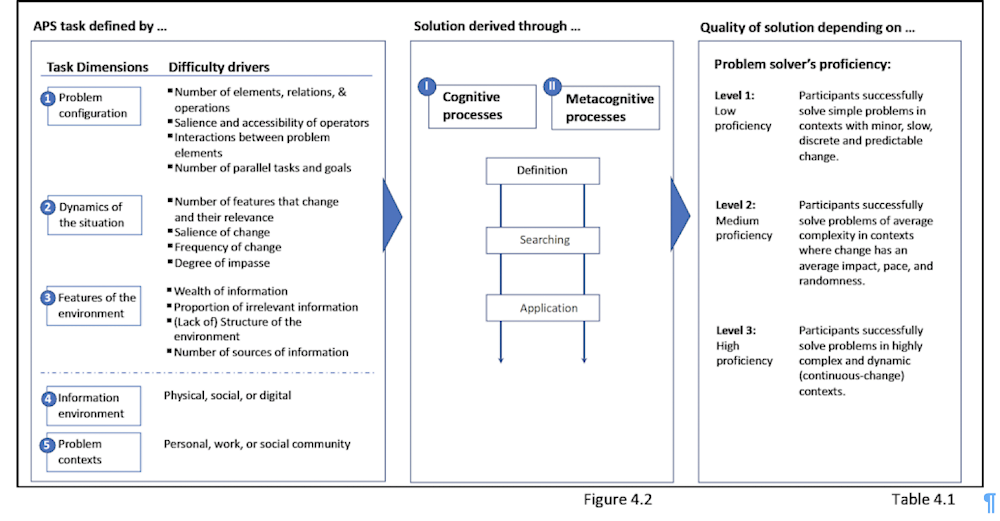

Copy link to Processes, content and contexts involved in Problem SolvingThe problem solving domain in PIAAC is organised along a set of task dimensions (problem configuration, dynamics of the situation, features of the environment, information environment, and problem contexts) and two large groups of processes: cognitive and meta-cognitive. This section focuses on these two overarching processes and describes the specific processes in each domain.

Cognitive processes are those that individuals must bring into play in order to construct a mental model of the state of affairs described in the problem and then to apply that mental model in real life. These cognitive processes are applied to the three stages of the problem solving process:

1. Defining (Problem definition: Mental model construction)

Selecting, organising, and integrating information into the mental model: Constructing a mental representation of the problem space (initial state, goal state, operators).

Retrieving relevant background information: Accessing memory to retrieve background knowledge (note: assessment tasks should be designed to avoid necessity of this process).

Externalising internal problem representation: Creating an external representation (e.g. drawing, table) that illustrates the problem solver’s mental model of the problem.

2. Searching (Search solution: Identifying effective operators)

Searching for operators in the mind and environment: Locating information about available action options that might be suited to solve the problem.

Evaluating operators based on problem constraints: Determining which of the action options will be best to reach the goal while considering all possible constraints.

3. Application (Apply solution: Applying plans and executing operators)

Applying plans and executing operators: Implementing the selected operator(s) to solve the problem.

Metacognitive processes are those that become more important to the extent that problems are more complex and difficult to comprehend, that the problems change, and that progress towards the solution becomes more difficult. The metacognitive processes are also applied to the three stages of the problem solving process:

1. Defining (Problem definition: Mental model construction)

Goal setting: Deciding upon what the to-be-achieved state is about (cannot be considered in large-scale assessments because allowing problem solvers to set their own goals would yield too many degrees of freedom).

Monitoring problem comprehension: Supervising whether one’s mental model of the problem matches the current state of affairs.

2. Searching (Search solution: Identifying effective operators)

Evaluating operators based on executability: Determining which of the action options will be best to reach the goal while considering all possible constraints.

3. Application (Apply solution: Applying plans and executing operators)

Monitoring progress: Determining whether executing operators achieves the desired outcome.

Regulating application of operators: Modifying the selection of operators in case the problem configuration has changed (cf. monitoring problem comprehension) or impasses have been noted (cf. monitoring progress).

Reflection: Deliberating about one’s own capabilities to solve problems with the goal of abstracting knowledge from it that can be applied in the future (cannot be considered in a large-scale assessment context because it requires repeated confrontation with similar problem solving instances).

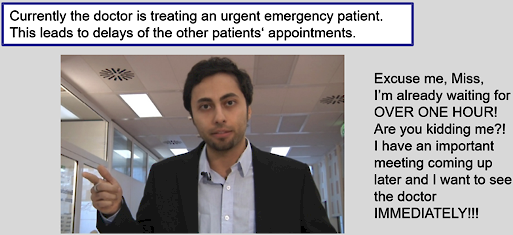

Proficiency Levels of Problem Solving

Copy link to Proficiency Levels of Problem SolvingTable 7.2 shows the general descriptions in the PIAAC adaptive problem solving scale from Cycle 2. These are based specifically on behaviourally descriptions that were offered in the PIAAC Cycle 2 framework for low and for high scorers on the three task dimensions, that is, when confronted with different (a) problem configurations, (b) dynamics in a situation, and (c) features of the environment. Table 7.2 illustrates the nexus of task dimensions, cognitive, and metacognitive processes, and proficiency levels.

Table 7.2. PIAAC Problem Solving Scale on Three Proficiency Levels

Copy link to Table 7.2. PIAAC Problem Solving Scale on Three Proficiency Levels|

Proficiency level |

General statement |

|---|---|

|

1 |

At Level 1, problem solvers successfully solve simple problems in contexts with minor, slow, discrete, and predictable change. They may also be able to solve static (and not dynamic) problems, or only tasks that are part of a static or dynamic problem. |

|

2 |

At Level 2, problem solvers successfully solve problems of average complexity in contexts where change has an average impact, pace, and randomness. |

|

3 |

At Level 3, problem solvers successfully solve problems in highly complex and dynamic (continuous change) problem contexts. They solve complex problems with multiple constraints in the problem configuration and with complex features of the problem environment and adapt their problem solving process well to highly dynamic changes in these problems. |

Source: PIAAC Cycle 2 assessment framework; (OECD, 2021[21]), p. 186.

Figure 7.2. The Nexus of Task Dimensions, Cognitive and Metacognitive Processes and Proficiency Levels

Copy link to Figure 7.2. The Nexus of Task Dimensions, Cognitive and Metacognitive Processes and Proficiency Levels

Note: APS is Adaptive Problem Solving.

Source: PIAAC Cycle 2 assessment framework; (OECD, 2021[21]): 167.

Related Frameworks pertinent to Problem Solving

Copy link to Related Frameworks pertinent to Problem SolvingDifferent frameworks have given slightly different definitions to problem solving, emphasising one or another component. The first paradigm was analytical problem solving in an earlier version of PISA (OECD, 2003[17]). PISA 2012 (OECD, 2013[18]) linked problem solving to creativity, emphasising creative and critical thinking abilities. PIAAC Cycle 1 (OECD, 2009[16]) focused on problem solving in technology-rich environments, considering the complexity introduced by technology. The fourth and current approach, championed by PIAAC Cycle 2 (OECD, 2021[6]), is central to understanding problem solving in PISA-VET. It introduces innovations such as the adaptive component (the problem changes during the process and an adaptive reaction to this is needed) and includes both metacognitive and cognitive skills in its definition. PIAAC Cycle 2 includes problem solving items in various activity contexts, with the "work" context being particularly relevant for the current endeavour. When selecting items from existing assessments, the focus will be on sampling PIAAC items from the work context owing to this compatibility.

Occupation-Specific Modulation of Problem Solving

Copy link to Occupation-Specific Modulation of Problem SolvingThe previous section mentioned that the PIAAC frameworks of both Cycle 1 and Cycle 2 recognise the importance of distinct competencies (some of which are associated with specific professional contexts) but intentionally leaves them out of the key competency framework. This approach is aligned with the proposed PISA-VET continuum of employability skills, in which these skills are considered transversal skills that function as prerequisites for individuals as they proceed from foundational level competency towards more sophisticated and profession-specific competency that are manifested and demonstrated as occupational-specific skills in one of the occupational areas of PISA-VET. Research regarding the five occupational domains covered by this project (see previous chapters) is overwhelming in terms of acknowledging the importance of problem solving as a prerequisite of job performance and of staying competitive on the job market throughout life.

For automotive technicians, their diagnostic skills have been closely linked to their problems solving skills and are a central point in the selection, training, and appraisal of mechanics (Abele, 2018). An automotive technician needs to diagnose (e.g. a faulty engine performance), repair (e.g. outdated equipment with no spare parts), or inspect (e.g. write off for service) mechanical parts or vehicles. Likewise, electricians, like all STEM-related professions, are deeply in need of problem solving skills, often for even routine and daily operations (Neubert et al., 2016[22]). They need to assess and diagnose (e.g. the breakdown of a large piece of electrical equipment in a factory), they need to assemble and install (e.g. a 'new to the market' piece of electrical equipment) and to inspect, test and report (e.g. a newly installed new piece of electrical equipment that shows a malfunction) technical equipment.

In business and administration, problem solving has been central both as managerial competency (van Aken and Berends, 2018[23]) and implicitly as well as explicitly as it is sometimes associated with Ackoff’s formulation of the central concept of “problem mess” (1981[24]), becoming part of the “problem solving cycle” as an approach to management. Similarly, Jonassen (2000[25]) points out that problems in real life are usually “meta problems” which consist of a bundle of nested problems of various kinds. An employee in such a role may need to identify needs for action (e.g. identify information gaps), process quantitative and qualitative data (e.g. apply the calculation scheme of manufacturing costs), or communicate effectively with internal or external stakeholders in loaded situations (e.g. recognise potential or actual conflicts and work towards their resolution; (Rausch and Wuttke, 2016[26])).

In health care, the importance of problem solving has been acknowledged very early on, and continues to be considered crucial for specialist performance and inclusion in modern approaches to the design of healthcare systems and physician training (Lorusso, Lee and Worden, 2021[27]). Employees in the health care industry may need to assess the needs of clients (e.g. analyse the physical and mental changes of a patient), plan a healthcare process (e.g. propose new coping strategies for a client in a therapeutic context), or monitor treatment and interventions (e.g. monitor the vital signs of a person who has undergone a difficult operation and who is still in a critical phase).

In tourism and hospitality, problem solving is considered a critical core skill by both experienced managers and students in hospitality (Dimmock, Breen and Walo, 2003[28]). Employees working in the hospitality industry may need to understand the personal needs of customers (e.g. converse with customers that are not fluent in your language and understand specific dietary requirements that they have), or manage complaints (e.g. understand and solve effectively complaints about the lodging arrangements of a customer, that have not been communicated in advance and for which the hotel is not prepared). To demonstrate the relevance of problem solving in a specific occupation, Table 7.4. displays examples of occupation-specific modulations of this employability skill across the occupational areas.

Summary

Copy link to SummaryProblem solving, as defined in the PIAAC Cycle 2 framework, is an employability skill that is foundational for participation in all aspects of work. While an essentially general skill, it may have job-specific components that are saturated in knowledge, reasoning, and decision-making typical for specific job domains or environments as acknowledged in an earlier section of this chapter. Thus, it may both contain and, more importantly, serve as the basis for developing additional occupation-specific skills within occupational areas. In the context of PISA-VET, higher levels on problem solving may be linked to better proficiency in the use of problem solving skills in specific professional settings, and in easier development of other skills.

Task Performance

Copy link to Task PerformanceThis section aims at summarising the task performance framework, as defined by the OECD's SSES and its relevance to the area of VET as a sub-set of employability skills. Developing and nurturing task performance skills supports individuals in leading fulfilling lives, forming meaningful connections, and thriving in various personal and professional contexts. This section on task performance was primarily extracted from the SSES Assessment Framework and Conceptual Framework (Kankaraš and Suarez-Alvarez, 2019[29]; Roberts et al., 2009[30]), which were developed by members of the SSES team. It derives from the international report on SSES Round 1 results (OECD, 2021[21]).

Definition of Task Performance

Copy link to Definition of Task PerformanceIn SSES, task performance was derived from the Big Five model of personality. Task performance corresponds to the dimension of conscientiousness. It is defined as a set of social and emotional skills, which are “individual capacities that can be manifested in consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours” (OECD, 2021[6]). These skills enable individuals to effectively manage and develop their emotions, thoughts, tasks, and relationships. Task performance refers to a range of constructs that describe the ability to be self-controlled, responsible to others, hardworking, motivated to achieve, honest, orderly, persistent and rule-abiding (Kankaraš and Suarez-Alvarez, 2019[29]). In short, it refers to the skills that enable individuals to get things done, as required and on time.

Relevance of Task Performance to VET

Copy link to Relevance of Task Performance to VETThe skills that are part of the SSES, including task performance and its dimensions, were chosen for their relevance to individuals across all aspects of life, whether professional, personal, or social. Empirical evidence supports the hypothesis that task performance is highly relevant across different work-related criteria such as job performance and trainings proficiency and across different occupations (Barrick and Mount, 1991[31]). Dudley et al. (2006[32]) found that responsibility, understood as one’s ability to honour commitments and be reliable, was significantly linked to several job performance criteria. It was positively linked to task performance (contributing to production of good or service) and organisational citizenship (pro-social workplace behaviour) and inversely linked to counter-productivity.

Consequently, task performance is relevant to the future of work as well as its demands today because it encompasses personal characteristics like being planful, careful, and hard working. Technology is replacing routine jobs, but, at the same time, is creating new opportunities that require individuals who can manage complex social interactions and non-routine tasks (OECD, 2019[5]). In fact, the capability to focus one’s attention on the task at hand is crucial in a lot of occupations and work settings, including scenarios like remote work, which has been accelerated adoption during and post the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, as an automotive technician, conscientiously working through a service checklist, despite high time pressure, noise, and other distractions is important to ensure a car’s repair and maintenance. Similarly, management assistants need to concentrate on the current task avoiding distractions from other activities when dealing with information-rich problems (Rausch and Wuttke, 2016[26]). For a peripatetic healthcare assistant, who provides support and assistance to patients in various healthcare settings, it is important to carefully plan the next week’s route for visits taking on responsibility towards the clients’ needs, but also on medical needs, logistical issues, and own role-associated boundaries. Well-rounded VET learners should therefore have solid task performance skills to be effective in their target occupation – in line with employers’ expectations. Research also suggests that these skills are malleable and susceptible to interventions (Durlak et al., 2011[33]; Sklad et al., 2012[34]; Taylor et al., 2017[35]), and can therefore be developed through education and training – including VET. Social and emotional skills are also more malleable at later stages in life than cognitive skills, which is especially relevant to VET programmes, as they typically cater to older populations, as opposed to general education (Cunha, Heckman and Schennach, 2010[36]; Cunha and Heckman, 2007[37]).

Processes, content and contexts involved in Task Performance

Copy link to Processes, content and contexts involved in Task PerformanceAs aforementioned, the SSES domain of task performance derives from the domain of conscientiousness from the Big Five model of personality and skills. SSES adapted the general Big Five framework to create a framework of skills, which are individual capacities that are learnable and malleable and thus, susceptible to program and policy interventions (OECD, 2021[21]). In SSES, task performance is divided into four dimensions, which compose more contextualised manifestations of broad domains. These narrower skills are more descriptive, specific, and accurate, and thus easier to measure:

Self-control: The ability to resist distractions, delay gratification and maintain concentration. Someone with high self-control postpones fun activities until important tasks are completed and thinks before they act, such as finishing notes before chatting to colleagues. Someone with low self-control is prone to say things before thinking and engages in impulsive behaviour, such as an employee who blurts out opinions in a meeting.

Responsibility: The ability to honour commitments and be punctual and reliable. Someone with high responsibility arrives on time for appointments and gets tasks done promptly, such as ensuring all emails are addressed before going home. Someone with low levels of responsibility, for example, does not follow through on agreements.

Persistence: The ability to persevere in tasks and activities until completion. Someone who is highly persistent finishes projects or work once started. Someone who has low persistence gives up easily when confronted with obstacles. This dimension is often assessed differently by age. In adult inventories of the Big Five, being persistent in the face of challenges is sometimes included under achievement motivation.

Achievement motivation: The drive to set high standards for oneself and work hard to meet them. Someone with high achievement motivation enjoys reaching a high level of mastery in some activity, is highly productive and aspires to excellence, such as an entrepreneur who works long hours and perseveres against setbacks to make their business profitable. Someone with low motivation lacks interest in reaching mastery in any activity, including professional competencies.

Proficiency Levels of Task Performance

Copy link to Proficiency Levels of Task PerformanceProficiency levels were not developed for SSES, although reporting scales were. For Round 1 of SSES (the only completed round to date), psychometric scales were developed using the assessment items for each skill. The reference was value fixed at 500 representing a centre of the scale characterized by individuals with either only mid-point or perfectly balanced responses (i.e. not leaning on one direction or another towards the poles defined below) and standard deviation set to 100.

The scale for each dimension (i.e. self-control, responsibility, persistence, and achievement motivation) features two meaningful poles. Individuals placed at one end of the scale have more of the attributes and qualities that define the pole to which they are closest and fewer of the attributes defining the pole from which they are farthest. Taking self-control out of the four dimensions of task performance, for example, respondents towards the highly self-controlled pole, reported themselves as more inclined to be careful with tasks, think before speaking, and postpone fun until they are finished with work. Respondents at the opposite end of the spectrum (uninhibited, less self-control) more often reported acting impulsively or speaking without thinking (SSES uses exclusively self-reports to assess skills).

Utilising proficiency levels is particularly beneficial when applied to performance-based measures since they enhance clarity and consistency by offering a clear and standardized framework for assessment and interpretation. However, there are several reasons for avoiding proficiency levels in social and emotional skills such as task performance. In fact, “proficiency levels” for social and emotional skills create problematic, universally normative measures for context-embedded and culturally relative capacities by implying an order, or hierarchy, to assessed behavioural patterns. Additionally, skills that may be useful in one context (e.g. high levels of self-control in fixing a delicate mechanical device or administering medication), may be less useful in others (e.g. coming up with new business ventures or taking creative risks may benefit from less restraint). This aspect of context-embedding is elaborated in the section below on the occupation-specific embedding of task performance. Measures of task performance provide countries and stakeholders with important insights into how test takers manifest task performance dimensions and how these link to contextual factors and outcomes. However, assigning universal proficiency levels may obscure the complexity and context-specific value of these skills.

Related Frameworks pertinent to Task Performance

Copy link to Related Frameworks pertinent to Task PerformanceThe SSES task-performance dimensions were derived from a range of existing child and adult taxonomies of the Big Five domains and facets. Task performance in general corresponds to the domain of conscientiousness. However, there are many different conceptualisations of its narrower dimensions. For SSES, taxonomies that were consistently identified and cross-culturally replicated were considered for possible inclusion. Seven dimension-level taxonomies for children and adolescents were used, along dimension scales from several well-known adult personality inventories. These seven taxonomies were examined for conceptual overlaps, similarities and differences and then served as a starting point of the development of a common framework. In addition to this, PISA 2021 Context Questionnaire Framework (OECD, 2019[38]) can be utilised as an additional point of reference for item adaptation. Within the PISA framework, task-performance items related to SSES were adapted, featuring extended item numbers across several task performance dimensions. These adapted items were seamlessly integrated into the background questionnaire and demonstrated strong psychometric properties.

In addition to these, task performance relates to other OECD frameworks on non-academic skills, such as PISA’s innovative domains and Education 2030’s Concept Notes. Outside the OECD, task performance overlaps with domains of many skills frameworks, including for social and emotional learning and employability. For example, achievement motivation and persistence both relate to Duckworth’s (Duckworth, 2007) much-used construct of Grit, describing sustained interest and perseverance toward long-term goals. The ExploreSEL platform created by the Ecological Approaches to Social and Emotional Learning (EASEL) Lab at Harvard identifies six common domains across 43 different frameworks for non-academic skills, including SSES. Task performance overlaps with all 42 other frameworks in certain dimensions of Cognitive, Values, Social and Identity (EASEL Lab., 2021[39]).

Occupation-Specific Modulation of Task Performance

Copy link to Occupation-Specific Modulation of Task PerformanceTask performance is a central skill to successfully perform at the workplace. All four facets of self-control, responsibility, persistence, and achievement motivation play an important role in different occupational settings. Concentrating on complex tasks, e.g. performing calculations while being frequently interrupted by phone calls or colleagues’ questions is challenging. Staying focused and handling those distractions reflects a strong degree of self-control.

In a working situation, for instance, when a colleague has not yet successfully solved a specific problem or an error is detected in an order, taking responsibility means not to ignore the problem or trying to delegate it to someone else. In contrast, a responsible person stays calm and remains focused on the relevant problem searching for additional information to solve it. Similarly, continuing with a task although unexpected challenges like a delivery of incorrect materials has occurred, reflects a high level of persistence. To demonstrate the relevance of task performance and the other three core employability skills in a specific occupation, Table 7.4. displays examples of occupation-specific modulations of the four employability skills.

Summary

Copy link to SummaryTask performance is a social and emotional skill with high relevance for the workplace across occupations consisting of the subdimensions self-control, persistence, responsibility, and achievement motivation. It has been included in previous OECD-led international assessments and describes an important employability skill in PISA-VET.

Collaboration

Copy link to CollaborationThis section summarises the Collaboration framework, as defined by the OECD's SSES and its relevance to the area of VET as a sub-set of employability skills. Collaboration skills facilitate effective teamwork, innovation, problem solving, and communication. They contribute to personal growth, enhance relationships, and improve outcomes in various contexts, ultimately leading to individual and collective success. This section was extracted from the SSES Assessment Framework and Conceptual Framework (Kankaraš and Suarez-Alvarez, 2019[29]), which were developed by members of the SSES team. It derives from the international report on SSES Round 1 results (OECD, 2021[21]).

Definition of Collaboration

Copy link to Definition of CollaborationIn SSES, collaboration was derived from the Big Five model of personality. Collaboration corresponds to the dimension of agreeableness. It is defined as a set of social and emotional skills, which are “individual capacities that can be manifested in consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours” (OECD, 2021[21]). These skills enable individuals to effectively manage and develop their emotions, thoughts, tasks and relationships (as already outlined in the previous section). Collaboration refers to a range of constructs that describe the ability to understand, feel, and express concern for others well-being, manage interpersonal conflict, and maintain positive relationships and beliefs about others (trust) (Kankaraš and Suarez-Alvarez, 2019[29]; Soto and John, 2017[40]). In short, it refers to the skills that enable individuals to get along with other people and work successfully together in various contexts and situational settings.

Relevance of Collaboration to VET

Copy link to Relevance of Collaboration to VETIn SSES, collaboration was chosen for its relevance to school children and individuals across all aspects of life, whether professional, personal, or social. Collaboration is also particularly relevant for VET due to its links to job performance outcomes, especially how individuals relate to colleagues in the workplace. Sackett and Walmsley’s meta-analysis found that agreeableness (the corollary to collaboration) predicted levels of organisational citizenship—pro-social workplace behaviours like supporting co-workers—and inversely predicted counter-productivity, such as absenteeism (Sackett and Walmsley, 2014[41]). Research also suggests that social and emotional skills such as collaboration are malleable and susceptible to interventions (Durlak et al., 2011[33]; Sklad et al., 2012[34]; Taylor et al., 2017[35]). Importantly, these skills are also more malleable at later stages in life than cognitive skills, which is especially relevant to VET programmes, as they typically cater to older populations, as opposed to general education (Cunha, Heckman and Schennach, 2010[36]; Cunha and Heckman, 2007[37]).

Developing the ability to collaborate is essential for VET learners, as many VET jobs – and the labour market more broadly – involve tasks that require workers to work and interact with others. Many typical VET jobs involve collaborating with workers in other roles and at different levels in a workplace hierarchy, as well as with clients/users. For example, healthcare/nursing assistants typically work closely with other healthcare professionals, while also interacting closely with patients to anticipate and understand (empathising) their needs. Electricians on construction sites will need to discuss with the client to understand wishes and constraints and need to work in tandem with architects and other construction workers. As such, collaboration capabilities are key, and VET learners can develop those in school settings as well as during work placements. Collaboration is relevant in many ways to today’s changing economies and societies. Diversifying societies, automation and the decline of traditional social networks are creating new pressures but also opportunities for those who can manage complex social interactions and non-routine tasks (OECD, 2019[5]). Strong collaboration and interpersonal skills, such as empathising and managing conflict, are increasingly key capacities for the future of work.

Processes, content and contexts involved in Collaboration

Copy link to Processes, content and contexts involved in CollaborationThe SSES domain of collaboration derives from the domain of agreeableness from the Big Five model of personality and skills (Chernyshenko, Kankaraš and Drasgow, 2018[42]). SSES adapted this framework to create its skills framework, focusing on capacities that are learnable and malleable and thus, susceptible to program and policy interventions (OECD, 2021[21]). In SSES, collaboration is divided into three dimensions:

Empathy: The ability to understand and care about others and their well-being. In VET contexts, someone with high empathy might be a nurse who knows how to console an upset patient or a manager who sympathizes with the needs of her employees. Someone with low empathy tends to misinterpret or disregard others’ feelings, such as a manager who ignores his employees’ wellbeing at work.

Trust: The ability to assume that others generally have good intentions and forgive those who have done wrong. Someone with high trust tends to lend things to others and avoids being judgmental or harsh, such as trusting the good intentions of an inexperienced colleague who makes mistakes. Someone with low levels of trust is secretive and suspicious in relation to other people, such as a manager who does not delegate tasks because they do not think their colleagues can handle them.

Co-operation: The ability to live in harmony with others, compromise, and value group cohesion. Someone with high levels of co-operation finds it easy to get along with people and respects group decisions, such as an engineer who can compromise on their plans when their teammates propose an alternative vision. Someone with low levels is prone to arguments or conflicts and does not tend to compromise, such as a mechanic who finds fault with suggestions from co-workers and gets into arguments over projects.

Proficiency Levels of Collaboration

Copy link to Proficiency Levels of CollaborationAs mentioned above in the section on task performance, proficiency levels were not developed for SSES, although reporting scales were developed. For Round 1 of SSES (the only completed round to date), psychometric scales were developed using the assessment items for each skill. The reference value was fixed at 500 representing a centre of the scale characterised by individuals with either only mid-point or perfectly balanced responses (i.e. not leaning on one direction or another towards the poles defined below) and standard deviation set to 100.

The scale for each process of collaboration (i.e. empathy, trust, and co-operation) included in SSES features two meaningful poles. Individuals placed at one end of the scale have more of the attributes and qualities that define the pole to which they are closest and fewer of the attributes defining the pole from which they are farthest. Taking “empathy”, for example, respondents towards the highly empathetic pole, reported themselves as more inclined to consider others’ wellbeing and their perspectives. Respondents at the opposite end of the spectrum (less empathetic) more often reported disregarding others’ feelings when making decisions.

As discussed in the earlier section on task performance, there are several reasons for avoiding proficiency levels in social and emotional skills such as collaboration. “Proficiency levels” for social and emotional skills create potentially problematic measures for context-embedded and culturally relative capacities. Skills that may be useful in one context (e.g. high levels of co-operation in healthcare where one often coordinates between healthcare assistants, nursing professionals, and medical doctors) may be less useful in others (e.g. a manager who must make tough but necessary staffing decisions despite short-term employee disapproval). This aspect of context-embedding is elaborated on in the occupation-specific embedding of collaboration.

Related Frameworks pertinent to Collaboration

Copy link to Related Frameworks pertinent to CollaborationThe SSES collaboration dimensions were derived from existing taxonomies of the Big Five domains and facets. Collaboration in general corresponds to the domain of agreeableness. However, there are many different conceptualisations of its narrower dimensions. For SSES, taxonomies that were consistently identified and cross-culturally replicated were considered for possible inclusion.

Collaboration relates to other OECD frameworks on non-academic skills, such as the PISA’s collaborative problem solving assessment in 2015 (OECD, 2017[43]; 2017[44]), the PIAAC Cycle 2 and the PISA 2022 and 2025 questionnaires. In the PIAAC Cycle 2, the assessment of Social and Emotional Skills is based on an extra short 15-item version of the Big Five Inventory BFI-2-XS (Soto and John, 2017[40]), an instrument based on self-reports composed of three items per domain. Countries had the option of administering a 30-item version (BFI-2-S) with six items per domain. The assessment distinguishes five broad skill domains: conscientiousness (i.e. task performance), emotional stability, extraversion, agreeableness (i.e. collaboration), and openness to experience. The inclusion of this module helps analysts understand the interaction between cognitive and social-emotional skills.

Also related to collaboration is the concept of collaborative problem solving as defined in PISA 2015: “the capacity of an individual to effectively engage in a process whereby two or more agents attempt to solve a problem by sharing the understanding and effort required to come to a solution, and pooling their knowledge, skills and efforts to reach that solution” ( (OECD, 2017[43]): 47). The framework encompasses four problem solving processes and three collaboration processes, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the underlying theoretical concept (OECD, 2017[44]; 2017[43]). The PISA 2022 and 2025 questionnaires expanded the assessment to include additional aspects such as co-operation, perseverance, self-control, curiosity, empathy, trust, perspective taking, assertiveness, stress resistance, and emotional control, using self-reported instruments. More specifically, within the PISA 2021 Context Questionnaire Framework (OECD, 2019[38]), collaboration items related to SSES were adapted, featuring extended item numbers across several dimensions of collaboration. These adapted items were seamlessly integrated into the background questionnaire and demonstrated strong psychometric properties. Thus, this PISA-VET framework can serve as an additional point of reference for item adaptation.

Outside OECD-conveyed studies, collaboration overlaps with domains of many skills frameworks, including for social and emotional learning and employability. The ExploreSEL platform created by the Ecological Approaches to Social and Emotional Learning (EASEL) Lab at Harvard identifies six common domains across 43 different frameworks for non-academic skills, including SSES (EASEL Lab, 2021). Collaboration overlaps with 41 other frameworks in the domains of Social, Emotion and Values.

Occupation-Specific Modulation of Collaboration