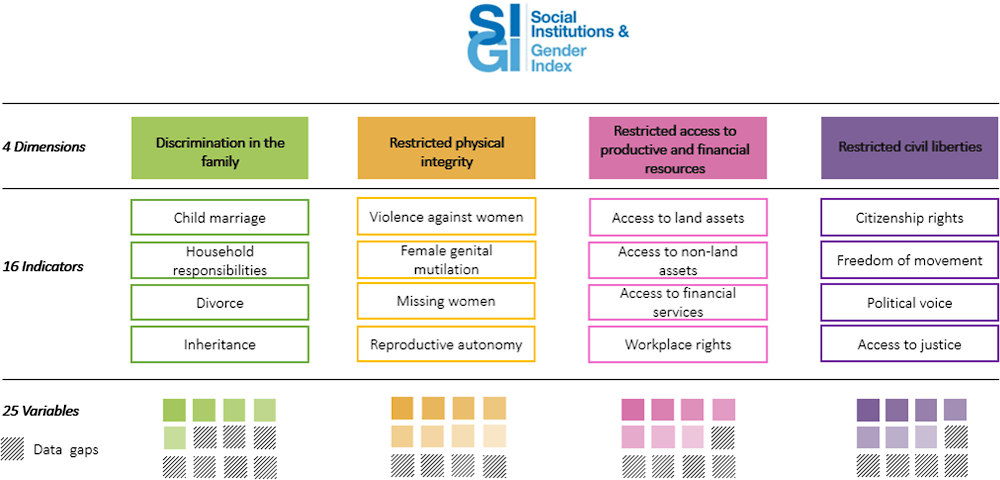

The SIGI is a composite index that builds on a framework of 4 dimensions and 16 indicators. For the fifth edition of the SIGI, these indicators build on 25 underlying variables (Figure A C.1).

SIGI 2024 Regional Report for Southeast Asia

Annex C. Conceptual framework of the SIGI

Figure A C.1. Conceptual framework of the fifth edition of the SIGI

The four dimensions of the SIGI cover the major socio-economic areas that affect women and girls throughout their lifetime:

The “Discrimination in the family” dimension captures social institutions that limit women’s decision-making power and undervalue their status in the household and the family.

The “Restricted physical integrity” dimension captures social institutions that increase women’s and girls’ vulnerability to multiple forms of violence and limit their control over their bodies and reproductive autonomy.

The “Restricted access to productive and financial resources” dimension captures women’s restricted access to and control over critical productive and economic resources and assets.

The “Restricted civil liberties” dimension captures discriminatory social institutions restricting women’s access to, and participation and voice in, the public and social spheres.

Variables included in the SIGI conceptual framework

Each dimension of the SIGI comprises four indicators (Figure A C.1). Theoretically, each indicator builds on three variables. The first variable aims to measure the level of discrimination in formal and informal laws, while the second and the third variables aim to measure the level of discrimination in social norms and practices:

Legal variables describe the level of gender-based discrimination in legal frameworks. Data for these variables are collected by the OECD Development Centre via a legal questionnaire (the SIGI 2023 Legal Survey) consisting of 173 questions. The survey was first filled by legal experts and professional lawyers from national and international law firms, before being reviewed by the Gender team of the OECD Development Centre and sent to governments for validation of the data. The cut-off date for the legal information collected was 31 August 2022.

Attitudinal variables describe the level of discrimination in social norms. Data for these variables are compiled from secondary data sources. The cut-off date for the attitudinal data was 31 December 2022.

Practice variables describe the level of discrimination in terms of prevalence and parity. Data for these variables are compiled from secondary data sources. The cut-off date for the practice data was 31 December 2022.

Treatment of missing data

In theory, the computation of the SIGI should be based on 48 variables (16 indicators each composed of 3 variables). However, because of data gaps, discrepancies exist between the conceptual framework and the number of variables used to calculate the SIGI. In total, the fifth edition of the SIGI in 2023 is based on 25 variables – including 15 legal variables, 9 practice variables and 1 attitudinal variable (Table A B.1). These variables were selected based on the following criteria:

Conceptual relevance: The variable should be closely related to the conceptual framework of discriminatory social institutions and measure what it is intended to capture.

Underlying factor of gender inequality: The variable should capture an underlying factor that leads to unequal outcomes for women and men.

Data quality, reliability, and coverage: The variable should be based on high-quality, reliable data. Ideally, the data should be standardised across countries/territories and have extensive coverage across countries/territories.

Distinction: Each variable should measure a distinct discriminatory institution and should add new information not measured by other variables.

Statistical association: Variables included in the same dimension should be statistically associated, and thereby capture similar areas of social institutions without being redundant.

Variables that measure important concepts covered by the SIGI but that could not be used to calculate the SIGI because of their low geographical coverage, are featured in the Gender, Institutions and Development Database (GID-DB). The GID-DB is a repository of legal, attitudinal and practice data measuring gender-based discrimination. For the fifth edition of the SIGI, this database includes 53 variables, including the 25 variables used to compute the SIGI (Table A C.1).

Table A C.1. SIGI and GID-DB variables included in the fifth edition of the SIGI

|

Variable |

Coding |

Sources |

Type of variable |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Discrimination in the family |

|||

|

Child marriage |

|||

|

Laws on child marriage |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: Child marriage is illegal for both women and men and the legal age of marriage is the same for women and men, without any legal exception. There are no informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) that allow or encourage girl child marriage. 25: Child marriage is illegal for both women and men, without any legal exception. However, some informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) allow or encourage girl child marriage. 50: Child marriage is illegal for both women and men. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of women or with the consent of certain persons (e.g. parents, legal guardians or judge). 75: Child marriage is legal for both women and men, or there is no legal age of marriage specified. 100: Child marriage is legal for women whereas the legal age of marriage of men is 18 or above. |

SIGI |

|

|

Prevalence of boy child marriage |

Percentage of boys aged 15-19 years who have been or are still married, divorced, widowed or in an informal union. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Prevalence of girl child marriage |

Percentage of girls aged 15-19 years who have been or are still married, divorced, widowed or in an informal union. |

SIGI |

|

|

Prevalence of girl child marriage (SDG Indicator 5.3.1) |

Percentage of women aged 20-24 years married or in union before age 18. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Household responsibilities |

|||

|

Laws on household responsibilities |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: Women have the same legal rights as men to be “head of household” or “head of family” (or the law does not make any reference to these concepts) and to be legal guardians of their children during marriage or in informal unions. There are no informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities regarding being recognised as the head of household, being the legal guardians of children nor choosing where to live. 25: Women have the same legal rights as men to be “head of household” or “head of family” (or the law does not make any reference to these concepts) and to be legal guardians of their children during marriage or in informal unions. However, some informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) create different rights or abilities regarding being recognised as the head of household, being the legal guardians of children or choosing where to live. 50: Women have the same legal rights as men to be “head of household” or “head of family” (or the law does not make any reference to these concepts) and to be legal guardians of their children during marriage or in informal unions. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of women. 75: Women do not have the same legal rights as men to be either “head of household” or “head of family” or to be legal guardians of their children during marriage or in informal unions. 100: Women neither have the same legal rights as men to be “head of household” or “head of family” nor to be legal guardians of their children during marriage or in informal unions. |

SIGI |

|

|

Attitudes on gender roles in the household |

Percentage of the population aged 18 years and above agreeing or strongly agreeing that “being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for pay.” |

GID-DB |

|

|

Attitudes on women’s income |

Percentage of the population aged 18 years and above agreeing or strongly agreeing that “if a woman earns more money than her husband, it's almost certain to cause problems.” |

GID-DB |

|

|

Attitudes on women’s work and children |

Percentage of the population aged 18 years and above agreeing or strongly agreeing that “when a mother works for pay, the children suffer.” |

GID-DB |

|

|

Unpaid care and domestic work (UCDW) ratio |

Female-to-male ratio of time spent on unpaid, domestic and care work in a 24-hour period. |

GID-DB |

|

|

UCDW daily hours: Men |

Men’s average time spent (in hours) on unpaid domestic and care work in a 24-hour period. |

GID-DB |

|

|

UCDW daily hours: Women |

Women’s average time spent (in hours) on unpaid domestic and care work in a 24-hour period. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Divorce |

|||

|

Laws on divorce |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: All women and men have the same rights as men to initiate or file for a divorce, to finalise a divorce or an annulment, and to retain child custody following a divorce. There are no informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities regarding initiating a divorce or being the legal guardians of children after a divorce. 25: All women and men have the same rights as men to initiate or file for a divorce, to finalise a divorce or an annulment, and to retain child custody following a divorce. However, some informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) create different rights or abilities regarding initiating a divorce or being the legal guardians of children after a divorce. 50: Women have the same rights as men to initiate or file for a divorce, to finalise a divorce or an annulment, and to retain child custody following a divorce. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of women. 75: Women do not have the same rights as men to initiate or file for a divorce, or to finalise a divorce or an annulment, or to retain child custody following a divorce. 100: Women do not have the same rights as men to initiate or file for a divorce, or to finalise a divorce or an annulment. Women do not have the same rights as men to retain child custody following a divorce. |

SIGI |

|

|

Inheritance |

|||

|

Laws on inheritance |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: All widows and daughters have the same rights as widowers and sons to inherit. There are no informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities regarding inheritance between sons and daughters and between male and female surviving spouses. 25: All widows and daughters have the same rights as widowers and sons to inherit. However, some informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) create different rights or abilities regarding inheritance between sons and daughters or between male and female surviving spouses. 50: Widows and daughters have the same rights as widowers and sons to inherit. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of widows and/or daughters. 75: Widows do not have the same rights as widowers to inherit, or daughters do not have the same rights as sons to inherit. 100: Widows and daughters do not have the same rights as widowers and sons to inherit. |

SIGI |

|

|

Restricted Physical Integrity |

|||

|

Violence against women |

|||

|

Laws on violence against women |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (comprehensive legal framework) to 100] 0: The law protects women from the following forms of violence: honour crimes, intimate partner violence, rape and sexual harassment. There are no legal exceptions that reduce penalties for domestic violence and the law recognises marital rape. The law is comprehensive (e.g. regarding specific provisions, all types of violence covered and all places covered). 25: The law protects women from the following forms of violence: honour crimes, intimate partner violence, rape and sexual harassment. There are no legal exceptions that reduce penalties for domestic violence and the law recognises marital rape. However, the approach is not fully comprehensive (e.g. lack of specific provisions, not all types of violence covered or not all places covered). 50: The law protects women from the following forms of violence: honour crimes, intimate partner violence, rape and sexual harassment. However, legal exceptions reduce penalties for domestic violence, or the law does not recognise marital rape. 75: The law protects women from some but not all of the following forms of violence: honour crime, intimate partner violence, rape and sexual harassment. 100: The law does not protect women from any of the following forms of violence: intimate partner violence, rape and sexual harassment. |

SIGI |

|

|

Attitudes justifying intimate-partner violence |

Percentage of women aged 15 to 49 years who consider a husband to be justified in hitting or beating his wife. |

SIGI |

|

|

Lifetime intimate-partner violence (IPV) |

Percentage of ever-partnered women and girls aged 15-49 years subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner over their lifetime |

SIGI |

|

|

Intimate partner-violence (IPV) rate in the last 12 months |

Percentage of ever-partnered women and girls subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Female genital mutilation (FGM) |

|||

|

Laws protecting girls and women from FGM |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (strongest protection by the law) to 100 (no protection by the law)] 0: The law criminalises FGM on narrow grounds and there are no informal laws that allow or encourage FGM. 25: The law criminalises FGM on broad grounds and there are no informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws) that allow or encourage FGM; or the law criminalises FGM on narrow grounds, informal laws exist, but the statutory law takes precedence over them. 50: The law criminalises FGM on broad grounds only. Informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws) that allow or encourage FGM exist but the statutory law takes precedence over them. 75: The law criminalises FGM on broad grounds only. Informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws) that allow or encourage FGM exist and the statutory law does not take precedence over them. 100: The law does not protect women and girls from FGM at all. Narrow grounds: Laws that explicitly criminalise FGM. Laws make reference to FGM, excision, female circumcision, genital mutilation or permanent altering/removal of external genitalia. Broad grounds: FGM can be prosecuted under law provision on mutilation, harming of a person's organs, (serious) bodily injury, hurt or assault. |

SIGI |

|

|

Attitudes of women towards FGM |

Percentage of women aged 15-49 years who have heard about FGM and think the practice should continue. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Attitudes of men towards FGM |

Percentage of men aged 15-49 years who have heard about FGM and think the practice should continue. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Prevalence rate of FGM |

Percentage of women aged 15-49 years who have undergone FGM. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Missing women |

|||

|

Missing women: measurement whether the population has a preference for sons over daughters |

Boy-to-girl ratio among 0-4-year-old (number of males per 100 females). Note: The natural birth ratio is 105 boys for 100 girls. |

SIGI |

|

|

Reproductive autonomy |

|||

|

Laws on women’s right to safe and legal abortion |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (rights are guaranteed) to 100 (rights are not guaranteed)] 0: The law protects women's right to a legal and safe abortion and does not require the approval of the father of the foetus to seek a legal abortion. 25: The law protects women's right to a legal and safe abortion. However, the law requires the approval of the father of the foetus to seek a legal abortion. 50: The law protects women's right to a legal and safe abortion when it is essential to save the woman's life and when the pregnancy is the result of rape, statutory rape and incest. However, the law does not protect women's right to a legal and safe abortion in one or more of the following circumstances: to preserve the mother's mental or physical health, for social and economic reasons, or in case of foetal impairment. 75: The law does not protect women's right to a legal and safe abortion in one or more of the following circumstances: when it is essential to save the woman's life or when pregnancy is the result of rape, statutory rape or incest. 100: The law does not provide women the right to a legal and safe abortion under any circumstance. |

SIGI |

|

|

Prevalence of unmet family planning needs |

Percentage of currently married or in-union women of reproductive age (15-49) who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception |

SIGI |

|

|

Restricted access to productive and financial resources |

|||

|

Access to land assets |

|||

|

Laws on access to land assets |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: All women and men have the same legal rights to own and use land assets. There are no informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities regarding the ownership or use of land. 25: All women and men have the same legal rights to own and use land assets. However, some informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) create different rights or abilities regarding the ownership or use of land. 50: Women and men have the same legal rights to own and use land assets. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of women. 75: Women and men have the same legal rights to own land assets. However, women do not have the same legal rights to use and/or make decisions over land. 100: Women do not have the same legal rights and access as men to own and use land assets. |

SIGI |

|

|

Gender gap in land ownership |

Share of women in the total number of land holders. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Land ownership of men |

Percentage of men who are land holders. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Land ownership of women |

Percentage of women who are land holders. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Access to non-land assets |

|||

|

Laws on access to non-land assets |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: All women and men have the same legal rights to own and use non-land assets. There are no informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities regarding the ownership or use of non-land assets. 25: All women and men have the same legal rights to own and use non-land assets. However, some informal laws (customary, traditional or religious laws/rules) create different rights or abilities regarding the ownership or use of non-land assets. 50: Women have the same legal rights as men to own and use non-land assets. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of women. 75: All women and men have the same legal rights to own non-land assets. However, women do not have the same legal rights as men to use and/or make decisions over non-land assets. 100: Women do not have the same legal rights as men to own non-land assets. |

SIGI |

|

|

Gender gap in house ownership |

Share of women in the total number of people who own a house alone. |

GID-DB |

|

|

House ownership of men |

Percentage of men who own a house alone. |

GID-DB |

|

|

House ownership of women |

Percentage of women who own a house alone. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Access to financial services |

|||

|

Gender-based discrimination in the legal framework on financial assets and services |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: All women have the same rights as men to open a bank account at a formal financial institution and to obtain credit, and the law does not require married women to obtain the signature and authority of their husband to do so. There are no informal laws (customary, religious, or traditional laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities between men and women to open a bank account or obtain credit. 25: All women have the same rights as men to open a bank account at a formal financial institution and to obtain credit, and the law does not require married women to obtain the signature and authority of their husband to do so. However, informal laws (customary, religious, or traditional laws/rules) create different rights or abilities between men and women to open a bank account or obtain credit. 50: Women have the same rights as men to open a bank account at a formal financial institution and to obtain credit, and the law does not require married women to obtain the signature and authority of their husband to do so. However, legal exceptions regarding access to formal financial services exist for some groups of women. 75: Women have the same rights as men to open a bank account at a formal financial institution and the law does not require married women to obtain the signature and authority of their husband to do so. However, the law does not provide women with the same rights as men to obtain credit. 100: Women do not have the same rights as men to open a bank account at a formal financial institution or the law requires married women to obtain the signature and authority of their husband to do so. |

SIGI |

|

|

Gender gap in bank account ownership |

Share of women in the total number of people aged 15 and above who have a bank account at a financial institution (by themselves or together with someone else) |

SIGI |

|

|

Bank account ownership of men |

Percentage of men who have a bank account at a financial institution (by themselves or together with someone else). |

GID-DB |

|

|

Bank account ownership of women |

Percentage of women who have a bank account at a financial institution (by themselves or together with someone else). |

GID-DB |

|

|

Workplace rights |

|||

|

Laws on workplace rights |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: Women and men are guaranteed equality in the workplace, including the right to equal remuneration for work of equal value, to work the same night hours, to work in all professions, and to register a business. The rights of all women are protected during pregnancy and maternity/parental leave. There are no informal laws (customary, religious, or traditional laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities between men and women to enter certain professions, take a paid job or register a business. 25: Women and men are guaranteed equality in the workplace, including the right to equal remuneration for work of equal value, to work the same night hours, to work in all professions, and to register a business. The rights of all women are protected during pregnancy and maternity/parental leave. However, some informal laws (customary, religious, or traditional laws/rules) create different rights or abilities between men and women to enter certain professions, take a paid job or register a business. 50: Women and men are guaranteed equality in the workplace, including the right to equal remuneration for work of equal value, to work the same night hours, to work in all professions, and to register a business. Women’s rights are protected during pregnancy and maternity/parental leave. However, legal exceptions to the rights to take a paid job and/or to register a business exist for some groups of women. 75: Women and men are guaranteed equal rights to enter all professions, to work the same night hours as men, and to work or register a business without the permission of someone else. However, women are not guaranteed non-discrimination in employment on the basis of sex, equal remuneration for work of equal value, or protection of their rights during pregnancy and maternity/parental leave. 100: Women do not have the same rights as men to enter all professions, to work the same night hours as men, or to work or register a business without the permission of their husband or legal guardian. |

Yes |

|

|

Attitudes on women’s right to a job |

Percentage of the population aged 18 years and above agreeing or strongly agreeing that “when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” |

GID-DB |

|

|

Attitudes on women’s ability to be a business executive |

Percentage of the population aged 18 years and above agreeing or strongly agreeing that “men make better business executives than women do.” |

GID-DB |

|

|

Gender gap in management positions |

Share of women among managers (SDG Indicator 5.2.2) |

SIGI |

|

|

Gender gap in top management positions |

Share of firms with a woman as top manager. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Restricted civil liberties |

|||

|

Citizenship rights |

|||

|

Laws on citizenship rights |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: Women and men have the same rights to acquire, change and retain their nationality as well as to confer their nationality to their spouse and children. There are no informal laws (customary, traditional, or religious laws) that create different rights or abilities between men and women to acquire, change, or retain their nationality, or to confer nationality to their spouse and/or children. 25: Women and men have the same rights to acquire, change and retain their nationality as well as to confer their nationality to their spouse and children. However, some informal laws (customary, traditional, or religious laws) create different rights or abilities between men and women to acquire, change, or retain their nationality, or to confer nationality to their spouse and/or children. 50: Women and men have the same rights to acquire, change and retain their nationality as well as to confer their nationality to their spouse and children. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of women. 75: Women and men have the same rights to acquire, change and retain their nationality. However, women do not have the same rights as men to confer their nationality to their spouses and/or children. 100: Women do not have the same rights as men to acquire, change or retain their nationality. |

SIGI |

|

|

Freedom of movement |

|||

|

Laws on freedom of movement |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: Women have the same rights as men to apply for national identity cards (if applicable) or passports, and to travel outside the country. There are no informal laws (customary, religious, or traditional laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities between men and women to apply for identity cards or passports. 25: Women have the same rights as men to apply for national identity cards (if applicable) or passports, and to travel outside the country. However, some informal laws (customary, religious, or traditional laws/rules) create different rights or abilities between men and women to apply for identity cards or passports. 50: Women have the same rights as men to apply for national identity cards (if applicable) or passports, and to travel outside the country. However, legal exceptions exist for some groups of women. 75: Women do not have the same rights as men to apply for national identity cards (if applicable) or passports, or to travel outside the country. 100: Women do not have the same rights as men to apply for national identity cards (if applicable) or passports, nor to travel outside the country. |

SIGI |

|

|

Gender gap in safety feeling |

Share of women among the total number of persons declaring not feeling safe walking alone at night in the city or area where they live. |

SIGI |

|

|

Safety feeling of men |

Percentage of men declaring not feeling safe walking alone at night in the city or area where they live. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Safety feeling of women |

Percentage of women declaring not feeling safe walking alone at night in the city or area where they live. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Political voice |

|||

|

Laws on political voice |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: Women and men have the same rights to vote and to hold public and political office in the legislature and executive branches. There are constitutional/legislated quotas or special measures other than quotas (e.g. disclosure requirements, parity laws, alternating the sexes on party lists, financial incentives for political parties) in place to promote women's political participation at the national or local levels. There are no informal laws (customary, religious or traditional laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities between men and women to vote or hold public office. 25: Women and men have the same rights to vote and to hold public and political office in the legislature and executive branches. There are constitutional/legislated quotas or special measures other than quotas (e.g. disclosure requirements, parity laws, alternating the sexes on party lists, financial incentives for political parties) in place to promote women's political participation at the national or local levels. However, some informal laws (customary, religious or traditional laws/rules) create different rights or abilities between men and women to vote or hold public office. 50: Women and men have the same rights to vote and to hold public and political office in the legislature and executive branches. However, there are no constitutional/legislated quotas or special measures other than quotas (e.g. disclosure requirements, parity laws, alternating the sexes on party lists, financial incentives for political parties) in place to promote women's political participation at the national or local levels. 75: Women and men have the same rights to vote. However, women do not have the same rights as men to hold public and political office in the legislative or executive branch. 100: Women do not have the same rights as men to vote. |

SIGI |

|

|

Attitudes on women’s ability to be a political leader |

Percentage of the population aged 18 years and above agreeing or strongly agreeing that “men make better political leaders than women do.” |

GID-DB |

|

|

Gender gap in political representation |

Share of women in the total number of representatives in parliament (lower house). |

SIGI |

|

|

Access to justice |

|||

|

Laws on access to justice |

[Scale: 0-100: scores range from 0 (no discrimination) to 100 (absolute discrimination)] 0: Women and men have the same rights to sue. Women’s and men’s testimony carries the same evidentiary weight in all types of courts, and in all justice systems when parallel plural legal systems exist. Women have the same rights as men to hold public or political office in the judiciary branch. There are no informal laws (customary, religious or traditional laws/rules) that create different rights or abilities between men and women to sue someone, to provide testimony in court, or to be a judge, advocate or other court officer. 25: Women and men have the same rights to sue. Women’s and men’s testimony carries the same evidentiary weight in all types of courts, and in all justice systems when parallel plural legal systems exist. Women have the same rights as men to hold public or political office in the judiciary branch. However, some informal laws (customary, religious or traditional laws/rules) create different rights or abilities between men and women to sue someone, to provide testimony in court, or to be a judge, advocate or other court officer. 50: Women and men have the same rights to sue. Women’s and men’s testimony carries the same evidentiary weight in all types of courts, and in all justice systems when parallel plural legal systems exist. However, women do not have the same rights as men to hold public or political office in the judiciary branch. 75: Women and men have the same rights to sue. However, women’s testimony does not carry the same evidentiary weight as men's testimony in all types of courts, or in all justice systems when parallel plural legal systems exist. 100: Women do not have the same rights as men to sue. |

SIGI |

|

|

Gender gap in population’s confidence in the judicial system and courts |

Share of women among the total number of persons declaring not having confidence in the judicial system and courts of their country. |

SIGI |

|

|

Confidence in the judicial system and courts of men |

Percentage of men who declare not having confidence in the judicial system and courts of their country. |

GID-DB |

|

|

Confidence in the judicial system and courts of women |

Percentage of women who declare not having confidence in the judicial system and courts of their country. |

GID-DB |

|

Note: SIGI variables refer to variables used to construct the composite index. GID-DB variables refer to variables measuring gender-based discrimination included in the Gender, Institutions and Development Database but not used to calculate the index.

Statistical computation of the SIGI

The statistical methodology of the SIGI consists in aggregating the levels of discrimination as measured by the variables into 16 indicators, which are in turn aggregated into 4 dimensions. These 4 dimensions are then aggregated into the SIGI score. At each stage of the aggregation process, the same aggregation formula is used.

The current methodology was developed in 2017 following an extensive process of consultation with gender and statistical experts and was first applied for the fourth edition of the SIGI published in 2019 (Ferrant, Fuiret and Zambrano, 2020[17]). In 2020, the methodology was reviewed during an Expert Group Meeting, and an internal quality review was undertaken in 2021 with the support of OECD’s Statistics and Data Directorate. The fifth edition of the SIGI in 2023 is the second time this methodology is applied.

Data cleaning and manipulation

Attitudinal and practice data

The SIGI relies on secondary data for the attitudinal and practice variable with varying data sources depending on the country/territory and the variable in question.

To ensure comparability across countries and adherence to the SIGI framework, quantitative data are first cleaned. This includes, for instance, ensuring that the population base is the same, or ensuring that the most recent datapoint is selected when relying on data from various sources.

In order to fit the SIGI scale that ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 being the best outcome and 100 being the worst, all quantitative variables are rescaled following a min-max normalisation process, which varies depending on the type of variable.

Variables measuring absolute levels of women’s deprivation: These variables do not have a male counterpart. Examples include the prevalence rate of female genital mutilation or the share of women facing unmet needs for family planning. These variables are expressed so that 0% corresponds to the best outcome for women – e.g. no women having experienced female genital mutilation – and 100% as the worst possible outcome for women – e.g. all women of reproductive age who want to delay a pregnancy with unmet needs for family planning.

Variables measuring relative levels of achievement or deprivation of women compared to men as the fraction of women among a particular sub-population: For these variables, the best possible outcome is 50%, indicating equality between men and women. These variables are capped at 50% and rescaled following a min-max normalisation process so that scores range from 0 to 100 with 0 being the best outcome for gender equality and 100 the worst possible outcome.

Case 1: The worst possible outcome is 100%, indicating that women account for the entire population deprived or facing discrimination. In this case, discrimination exists as long as women’s share is above 50%. No penalties are applied if women perform better than men and if their share drops below 50%. Examples include the gender gap in safety feeling, i.e. the share of women among those not feeling safe when walking alone at night, or the gender gap in bank account ownership, i.e. the share of women among bank account owners.

Case 2: The worst possible outcome is 0%, indicating that women account for the entire population deprived or facing discrimination. In this case, discrimination exists as long as women’s share is below 50%. No penalties are applied if women perform better than men and if their share exceeds 50%. Examples include the gender gap in management positions or among members of national parliaments.

Variables measuring the relative levels of achievement or deprivation of women compared to men as the female-to-male ratio: These variables are calculated as the value for women divided by the value for men. For these variables, the best possible outcome is 1, indicating equality between men and women. The worst possible outcome is the maximum value of the ratio across all countries covered. These variables are capped at 1, meaning that discrimination exists as long as the female-to-male ratio is above 1. No penalties are applied if women perform better than men and if the ratio drops below 1. These variables are rescaled following a min-max normalisation process so that scores range from 0 to 100 with 0 being the best outcome for gender equality and 100 the worst possible outcome. Examples include the boy-to-girl ratio where, because the natural birth ratio stands at 105 boys per 100 girls, the variable is capped at 105.

Legal data

The SIGI relies on primary data collection for the legal variables, measuring gender-based discrimination in formal and informal laws. The SIGI 2023 Legal Survey consists of 173 questions, among which 114 are used to create the legal variables (see Annex C in (OECD, 2023[18])). Legal experts and lawyers completed the SIGI 2023 Legal Survey between March 2022 and February 2023, with a cut-off date for legal information on 30 August 2022. The Gender team of the OECD Development Centre performed data quality checks before sharing the responses with governments to validate the collected data.

The information captured by the SIGI 2023 Legal Survey is encoded to build 15 legal variables across each indicator of the SIGI conceptual framework – the only indicator that does not have a legal variable is the Missing women indicator as there are no laws that can be measured for this type of discrimination against girls.

A coding manual was created to quantify the level of legal discrimination based on the information collected via the SIGI 2023 Legal Survey. The coding manual ensures consistency across variables, guarantees objectivity in the selection criteria for scoring, and allows for comparability across countries as well as over time. A five-level classification (0, 25, 50, 75 and 100) serves as the basis to encode the legal information and reflects the level of discrimination in formal and informal laws: 0 denotes equal legal protections between women and men, without legal or customary exceptions, and 100 denotes a legal framework that fully discriminates against women’s and girls’ rights (Table A C.2).

Table A C.2. Scoring methodology for legal variables

|

|

Score |

|---|---|

|

The legal framework provides women with the same rights as men, with no exceptions, and applies to all groups of women. There are no customary, religious or traditional practices or laws that discriminate against women. |

0 |

|

The legal framework provides women with the same rights as men, with no exceptions, and applies to all groups of women. However, some customary, religious or traditional practices or laws do discriminate against women. |

25 |

|

The legal framework provides women with the same rights as men. However, it foresees exceptions or does not apply to all groups of women. |

50 |

|

The legal framework restricts some women’s rights. |

75 |

|

The legal framework fully discriminates against women’s rights. |

100 |

Scores of legal variables take into account all applicable legal frameworks in the country whether formal or informal, including those that may only apply to part of the population. In many countries across the world, parallel, dual, plural or federal legal frameworks exist, all of which can further co-exist with informal law and justice systems. The SIGI methodology takes this legal plurality into account by assessing whether all women have the same rights under the respective applicable formal laws. The SIGI methodology further assesses whether informal laws create exceptions to the formal law(s).

Construction of indicators, dimensions and the SIGI

Following the cleaning and rescaling of attitudinal and practice data, as well as the encoding of legal data, quantitative and qualitative variables are grouped into a unique database, which serves to build the indicators, dimensions and the SIGI.

The computation of the SIGI relies on the use of the same formula in three different stages to aggregate variable into indicators, indicators into dimensions and dimensions into the SIGI. The formula was developed in 2017, during the revision process that produced the current methodology (Ferrant, Fuiret and Zambrano, 2020[17]).

Aggregation of variable into indicators

In theory, each indicator of the SIGI relies on three distinct variables, each measuring a different area where discrimination can occur: a legal variable, an attitudinal variable and a practice variable. Because of data gaps, this is not always possible and certain indicators rely on only one or two variables. Underlying variables are equally weighted within a given indicator. For instance:

or

Scores for an indicator can only be calculated if data are available for all underlying variables. In case of missing data, the indicator score is left to missing.

Aggregation of indicators into dimensions

Each dimension builds on four indicators that are equally weighted. For instance:

Scores for a dimension can only be calculated if data are available for all underlying indicators. In case of missing data in one or more indicators – resulting from missing data in the underlying variables – the dimension score is left to missing.

Aggregation of dimensions into the SIGI

The four dimensions are aggregated into the SIGI score for each country. Dimensions are equally weighted:

SIGI scores can only be calculated if data are available for all underlying dimensions. In case of missing data in one or more dimensions – resulting from missing data in the underlying variables – the country does not obtain a SIGI score.

References

[12] DHS Program (2022), DHS Program STATcompiler, https://www.statcompiler.com/en/.

[8] European Commission (2016), Special Eurobarometer 449: Gender-based violence, https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2115_85_3_449_eng?locale=en.

[17] Ferrant, G., L. Fuiret and E. Zambrano (2020), “The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) 2019: A revised framework for better advocacy”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 342, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/022d5e7b-en.

[15] Gallup (2021), Gallup World Poll, https://www.gallup.com/topic/world-poll.aspx.

[5] Inglehart, R. et al. (2022), “World Values Survey: All Rounds – Country-Pooled Datafile Version 3.0”, World Values Survey, JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat, Madrid, Spain and Vienna, Austria, https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp.

[16] IPU Parline (2022), Global data on national parliaments. Monthly ranking of women in national parliaments, https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=1&year=2023.

[18] OECD (2023), SIGI 2023 Global Report: Gender Equality in Times of Crisis, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4607b7c7-en.

[1] OECD Development Centre/OECD (2023), SIGI 2023 Legal Survey, https://oe.cd/sigi.

[9] UNICEF (2022), Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Statistics, https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/.

[2] UNICEF (2022), “Percentage of boys aged 15-19 years who are currently married or in union”, UNICEF Data Warehouse (database), https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=.PT_M_15-19_MRD..&startPeriod=2011&endPeriod=2021.

[3] UNICEF (2022), “Percentage of girls aged 15-19 years who are currently married or in union”, UNICEF Data Warehouse (database), https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=.PT_F_15-19_MRD..&startPeriod=2011&endPeriod=2021.

[4] UNICEF (2022), “Percentage of women (aged 20-24 years) married or in union before age 18”, UNICEF Data Warehouse (database), https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=.PT_F_20-24_MRD_U18..&startPeriod=2012&endPeriod=2022.

[10] United Nations (2022), 2022 Revision of World Population Prospects, https://population.un.org/wpp/.

[11] United Nations (2022), Family Planning Indicators, https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/family-planning-indicators.

[6] United Nations (2022), UN SDG Indicator Database, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/dataportal/database.

[7] WHO (2022), “Proportion of females 15-49 years who consider a husband to be justified in hitting or beating his wife”, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health and Ageing Data Portal (database), https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/indicator-explorer-new/mca/proportion-of-females-15-49-years-who-consider-a-husband-to-be-justified-in-hitting-or-beating-his-wife.

[14] World Bank (2022), World Bank Enterprise Surveys, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data.

[13] World Bank (2021), The Global Findex Database, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex/Data.