Social impact measurement needs to be integrated in a permanent management process to enable evidence-based decision making and organisational learning. Impact management involves repeated measurement and continuous monitoring to understand what works and integrating those lessons into organisational practices and policies. This chapter outlines six building blocks that structure an impact management system that is not only used for reporting to external stakeholders but also for feeding into strategic action and planning.

Measure, Manage and Maximise Your Impact

4. The building blocks of impact management

Abstract

Manage and maximise impact for strategic decision-making

Most organisations embrace impact measurement progressively. Impact measurement practices run along a continuum, from the more basic solutions (e.g. developing a theory of change and monitoring outputs) to those requiring more sophisticated skills and data (e.g. impact attribution and monetisation) (OECD, 2021[1]; HIGGS et al., 2022[2]). During consecutive measurement cycles, the social economy entity will fine-tune the number and complexity of tools it deploys, the way it uses them, and the level of ambition/challenge involved.

An organisation can only maximise its positive impacts, and mitigate the negative ones, if it embeds impact management directly into its long-term strategy and governance, and across its activities (IMP, 2023[3]). Organisational learning is an iterative and evidence-based process that takes time. Social impact management can complement strategic planning, reducing the risk of performing unnecessary actions or wasting resources. Impact management involves repeated measurement and continuous monitoring to understand what works, and integrating those lessons into organisational practices and policies. This includes adopting a level of quality checks and balances for impact measurement similar to what is done for other functions, like human resource management and accounting.

Infographic 4.1. Steps to manage and maximise social impact

Source: OECD

Impact management is the process by which an organisation understands, acts on and communicates its impacts on people and the natural environment, in order to reduce negative impacts, increase positive impacts, and ultimately achieve sustainability and increase well-being (IMP, 2023[4]).

Impact measurement alone is not enough to enable evidence-based decision-making and organisational learning. Impact evidence becomes most powerful when integrated in a permanent process of impact management, which feeds into the social economy entity’s strategic and operational decisions. Institutionalising feedback loops with beneficiaries, members, employees and owners at an appropriate timing and frequency will ensure that the information collected is not only useful for reporting to external stakeholders, but also for strategic action and planning (Figure 4.1).

Social economy entities go through different phases in their impact creation journey. Each has different commitments and motivations for undertaking impact measurement, based on its fundamental activities, priorities and challenges. The pathway to impact creation is not necessarily linear. Instead, social economy entities enter, exit and revisit their measurement and management approach in response to changing needs, priorities, resources and contexts (Budzyna et al., 2023[5]). Many will move from purely formal compliance (responding to funders’ requests) to slowly reducing the level of internal resistance and starting to use the data for management purposes (structuring meetings, holding specific discussions and widening participation) and finally engaging actively in evidence-based decision-making, adapting interventions and processes, collaborating with others in the ecosystem (Arvidson and Lyon, 2014[6]). Over time, and with repeated measurement cycles, the impact management infrastructure will come to crystallise the social economy entity’s experience and inform future decisions to maximise impact. Figure 4.1 outlines the journey from measurement and management to maximisation.

Figure 4.1. The journey from impact measurement to maximisation

Source: OECD.

Integrate impact evidence into decision-making

To serve decision makers’ needs in a responsive and timely fashion, it is important to embed social impact measurement in the social economy entity’s strategic governance system. Impact measurement should not be regarded as a one-shot, standalone activity, but should rather be integrated in the end-to-end process of performance management, with its own timeframe and feedback loops to ensure proposer use of the information. To better fit the needs of social economy entities, the impact management process should be:

Strategic: What can and should be measured depends on the social economy entity’s visibility and control over impacts, and how its operating model and mission evolve.

Adaptive: Social economy entities cannot hold conditions constant or use the same metrics consistently (i.e. over time and with peers) because their context, resources, mission and strategy change over time.

Iterative: The impact measurement and management journey ebbs and flows, from sophisticated and multidimensional approaches to simple and direct measures, and then back again (Budzyna et al., 2023[5]).

With the notable exception of foundations, social economy entities have historically relied on participative and collaborative governance structures to spur their development. The composition of formal governance bodies, such as the general assembly and the board of directors, reflects the pursuit of the collective or general interest (OECD, 2023[7]). Mutual societies and cooperatives are owned and controlled by their members, who are also users, producers or workers. Over 68% of social enterprises in Europe involve employees in organisational decision-making to a (very) high extent, and almost 55% also involve beneficiaries to a moderate or (very) high extent (Dupain et al., 2022[8]). It follows that decision-making bodies are particularly relevant to informing the impact measurement process, as they are already an intrinsic expression of stakeholder engagement.

Impact management responsibilities need to be formalised as part of the governance and oversight functions. Typically, the governing body will be responsible for adopting the change strategy at the organisational level, in accordance with the social economy entity’s mission, and defining the impact-measurement priorities (ideally, by adopting a multi-annual plan reconciling learning needs and reporting deadlines). It may also adopt impact management policies, in compliance with international standards and requirements for public disclosure of impact evidence. Finally, it will approve annual reports before their dissemination, and oversee the consistency of external communication and fundraising efforts with the stated impact objectives.

Every social economy entity will decide which stakeholders to involve and when, ideally utilising stakeholder engagement tools that help establish relevance. Different measurement tools require different capabilities and not all tools are appropriate for all audiences, due to their levels of complexity, cost, or suitability for the parameter being measured (Hall, Millo and Barman, 2015[9]). Social economy entities can decide which tools are most appropriate based on whether there is sufficient budget to undertake the whole process, whether the impact-measurement lead (i.e. the person responsible for leading the whole measurement cycle internally) has the necessary skills to measure using specific tools, and whether the data and complexity of the process match the needs of the stakeholder group being asked to participate.

To consider impact evidence holistically, social economy entities can carefully synchronise the measurement cycle(s) with the management process. The impact-measurement lead can set up regular meetings with executive or operational management, encourage reflection before meetings, debate emerging findings with internal stakeholders, identify failures and strengths, disseminate regular updates on key performance indicators and reader-friendly summaries of longer reports, and so on. These interactions can be scheduled in advance of important dates in the social economy entity’s calendar, for instance strategic meetings, negotiations with funders and partners, performance reviews, sectoral conferences (see Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Creating spaces for dialogue based on impact evidence

Impact evidence can be particularly helpful to the social economy in balancing social and financial considerations, especially when decisions are reached through participatory practices.

Social economy entities have experimented with creating spaces for negotiation, where internal stakeholders come together to share their different – and sometimes conflicting – understandings of the main goals and results, review potential resolutions to any difficulties encountered, and decide on the strategic actions and trade-offs necessary to address the entity’s mission.

These can be complemented by herding spaces, which involve similar debates and conflict resolution, but with external stakeholders at the institutional or sectoral level (e.g. with incubators or other social enterprises). By involving the wider community of external stakeholders, herding spaces provide a moral, motivational and pragmatic compass to internal decision makers. In fact, they often serve as a reminder of the social economy entity's ideological purpose (“why we are doing this”) and methods (“how we can do it”). They also help understand the normative expectations and evolving conditions in which the entity operates.

Both spaces for negotiation and herding spaces are considered essential in enabling social enterprises to avoid mission drift, ultimately also helping to scale operations in a sustainable manner.

Source: (Ometto et al., 2018[10]).

Furthermore, as some interventions target longer-term change, social economy entities must allocate sufficient budget and time to establishing and maintaining important stakeholder relationships over longer periods. Depending upon whether impact is expected within the short, medium or long term, social economy entities may need to collect several years’ worth of data to determine whether the intended change has occurred, checking in with the stakeholder group either annually or bi-annually, using the agreed method (e.g. surveys, interviews, face-to-face meetings or focus groups). This will require closely managing the stakeholder relationship by sending results back to the stakeholder group after every round of data collection, to maintain contact and increase the likelihood of commitment. This may also be required at the programme level, although external stakeholders rarely provide support (in terms of resources and reporting deadlines) over the long term.

Engage stakeholders

Participatory governance is one of the fundamental principles of the social economy. Concretely, it means ensuring that the interests of all relevant stakeholders are represented in decision-making processes (European Commission, 2020[11]). This is especially true for cooperatives and mutual benefit societies, which have shared ownership by design. Social impact measurement and management represents an important venue for engaging stakeholders in the decision-making process, offering them an opportunity to scrutinise and debate an organisation’s values, activities, performance and social outcomes (Brown and Dillard, 2015[12]).

A social economy entity’s stakeholders are people or groups who are directly or indirectly affected by its operations or interventions, or may influence the outcomes positively or negatively. Typical internal stakeholder groups include owners, board members, managers, clients and members (of social enterprises, cooperatives and mutual societies), employees, volunteers, and clients or beneficiaries (the end users receiving a social change intervention). A characteristic that helps distinguish social economy entities from conventional businesses is that they have beneficiaries. These can at times overlap with users, clients and customers, who may benefit from reduced costs or more targeted services and products that might otherwise not exist on the market. Common external stakeholder groups include suppliers and distributors, local and national public administrators (financiers and/or regulators), private investors and funders, local community organisations and citizens, and professional and trade networks. Figure 4.2 shows the various stakeholders by type of social economy entity.

Figure 4.2. Stakeholder groups by type of social economy entity

Since participatory governance is a building block of social economy entities, various stakeholder groups may already be identified and consulted in the decision-making process. This might facilitate the social impact measurement and management process at the corporate level. For instance, worker and social cooperatives in Europe already have access to a common blueprint for categorising them (CECOP, 2021[13]). However, impact measurement at the programme level may require identifying a more specific set of stakeholders (e.g. local rather than umbrella organisations). Moreover, the operational and governance model chosen by the social economy entities implies that one or more of these groups are vulnerable in some way (i.e. suffering from poverty, health issues, trauma, living with disabilities or under conditions of displacement). It follows that stakeholder engagement is even more fundamental when assessing indicators relating to social inclusion, well-being and sense of community, as this often requires beneficiaries to describe the change being created in their own words or values.

Yet stakeholders come with their own expectations for participating in impact measurement, and not all need or want to be involved in all phases of the measurement cycle. While internal stakeholders (such as managers and employees) are primarily responsible for supervising and providing inputs until its completion, other groups may only intervene sporadically. Social economy entities also need to accommodate the needs of the different groups with which they work, whose different vulnerabilities can strongly influence their ability to engage with the various components and methods of the measurement cycle. Due to the intrinsic social orientation and participatory values of the social economy, any dedicated effort to measure their impact will therefore strive to put stakeholder engagement at centre stage. Figure 4.3 provides a checklist for having meaningful consultations with stakeholders.

Figure 4.3. Checklist for a meaningful consultation with stakeholders

In conclusion, there are both benefits and challenges to engaging stakeholders. Stakeholders can help mobilise additional contributions (both in terms of resources and data), identify important externalities and build trust with communities. Yet stakeholder consultation during impact measurement is often costly, and may be underutilised for lack of budget or capabilities. Moreover, gaining access to the full range of relevant stakeholders (all of whom have diverse needs, values and interests) in a timely and consistent manner is rife with operational challenges. Table 4.1 lists the benefits and challenges of stakeholder engagement.

Table 4.1. Benefits and challenges of stakeholder engagement

|

Benefits |

Challenges |

|---|---|

|

Engagement can lead to more ownership and control over the outcomes. When people participate in decisions that affect them, they are more likely to understand the reason for the decision and participate in implementing and maintaining the activities supported by that decision. |

Engaging stakeholders is especially challenging for social economy entities owing to high costs, limited capabilities, poor access to information and stakeholders’ different needs. |

|

Engagement minimises the risk of failing to involve people who may be affected by a decision and might as a result attempt to undermine or disrupt the initiative decided upon by others. |

Social economy entities have different budgets for impact measurement, influencing their options and degree of engagement with various groups. |

|

Internally, it provides managers and employees with more opportunities to learn and improve the entity’s activities and operational processes, based on a better understanding of stakeholders’ needs and demands, as expressed through ongoing consultations. |

Stakeholder engagement varies across the measurement process: the tools that will be required (from identifying the stakeholders to be involved, to generating a consensus on the objectives, to gathering data from stakeholder groups –especially vulnerable ones – and then valuing and validating those data before reporting them) are likely to require different capabilities and skill sets. |

|

Consistent engagement is likely to promote a learning culture, developing trust between various stakeholder groups. This opens the possibilities of sharing and confronting failures rather than avoiding them or being fearful of discussing problems, ultimately reducing risks. |

Tools such as stakeholder mapping and outcome mapping, which help social economy entities detect relevant stakeholders and identify their impact measurement needs, can also help them plan the necessary resources to engage stakeholder groups at different stages. However, the different stakeholder groups may not always be identified beforehand, especially if they are external to the operating model and geographically dispersed. Consequently, they may fail to be engaged at the right time – or in the right way – in the impact measurement process. |

Develop skills

Impact analysis requires specific skills, especially for quantitative data treatment, monetisation and engaging vulnerable groups. Social economy entities can choose to source that capacity externally or develop it internally. Even when resorting to independent experts, they may still need to build some level of impact literacy in-house to interpret, use and communicate the results of the impact measurement process meaningfully.

At some point along their impact journey, social economy entities may wish to establish the impact measurement function in-house, with an impact measurement lead and possibly a supporting team. This does not necessarily require a full-time equivalent employee (especially in small structures), but responsibilities throughout the measurement cycle need to be clearly defined as part of the management process. Larger social economy entities may have three or four staff members on the impact measurement team, one of whom needs to take the lead. Smaller entities without a permanent team tend to assign responsibility to employees working in marketing or operations. In such cases, data collection becomes an additional task, and often does not receive enough attention to confer robustness and credibility without external validation.

Even before independent verification, it is critical to identify a single one person responsible for internal quality checks in order to support good and credible data. When conducting surveys, for example, it is helpful to test the questionnaire beforehand and check the answers as they are coming in, to provide prompt feedback about whether corrections are needed and still possible. The impact measurement lead requires a range of skills, such as knowledge of stakeholder engagement and management, as well as quantitative and qualitative indicator design; the ability to analyse and interpret multiple datasets (written and oral); and a talent for communication and advocacy. To promote effective stakeholder engagement in particular, the team should also possess soft skills. These include reflexivity and the ability to facilitate group dynamics, listen and respond appropriately to sensitive subjects, and counsel vulnerable individual suffering with difficult life circumstances.

Many options are emerging internationally for trainings and certifications on impact measurement, some of which are available at no cost. Public authorities have supported the creation of free trainings on social impact measurement in many countries, although these are often short-lived projects (OECD, 2023[18]). These trainings are generally offered by:

Universities and research institutions: the free virtual training on “Impact Measurement and Management for the Sustainable Development Goals” was created by the Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship (CASE) at Duke University (United States) as part of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)’s “SDG Impact” initiative.1 The Coursera e-learning platform proposes several other courses, for instance by the University of Pennsylvania2 and ESSEC Business School.3 While the modules are generally accessible for free, most certifications can only be obtained through payment. Similarly, hybrid or in-person trainings, like the “Impact Measurement Programme” taught by Oxford University,4 typically require tuition fees.

Social economy umbrella organisations and social enterprise incubators or accelerators: among their offerings are the social impact measurement training platform for social enterprises in Lithuania and “Développons et Évaluons Notre Impact Social” (DENIS), a project implemented in Wallonia, Belgium (OECD, 2023[18]).

Professional networks of impact measurement experts or standard-setting organisations, often targeting the broader social economy system: notable examples include the accreditation on SROI and impact measurement and management granted by Social Value International and its affiliated providers,5 the educational offerings by the Global Impact Investing Network to support the implementation of IRIS+,6 and the Cerise+ Social Performance Task Force (Cerise+SPTF) certification on social and environmental performance management.7 National or local competence centres may also provide workshops or fully fledged training programmes on impact measurement, like the centre recently established in Turin, Italy (OECD, 2023[18]), or the Social Impact Labs in Germany.

In Europe, several resources for capacity-building on impact measurement and management targeted at the social economy are available for free, thanks to co-financing by the European Commission. Since 2022, the online platform of the Social Impact Measurement for Civil Society Organizations (SIM4CSOs) has been offering free training materials specifically designed for civil society organisations, their volunteers and staff (Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Training on Social Impact Measurement for Civil Society Organizations (SIM4CSOs)

The EU-funded SIM4CSOs project was implemented from 2020 to 2022 in eight countries with the goal of empowering non-profit organisations by enhancing their effectiveness, transparency and governance through the application of social impact measurement methods.

Comprehensive training materials were developed through research, surveys and focus groups at the country level. The online learning platform provides free access (though a simple registration process) to three mini lessons on the design and implementation of a social impact measurement system. Besides the virtual learning environment, the website offers a methodological manual, practical worksheets, filled examples and a self-assessment checklist, all free to download.8

By the end of the project, more than 100 people had registered on the online learning platform. In feedback surveys, users positively assessed the quality and coherence of the content, as well as the platform’s usefulness and efficacy. They especially appreciated the lessons’ clarity in illustrating the transition from theory to practice, the immediacy and extent of the content, the simplicity of the language used, and the provision of relatable examples and practices.

Source: https://measuringimpact.eu/.

While these efforts aim to directly capacitate social economy entities, they serve a secondary function: they enhance the understanding of stakeholders in the broader social economy system (including public and private funders), and independent experts who may accompany them in implementing social impact measurement and management. These resources may also boost the offer for social impact verification by third-party service providers.

Explore digital tools for data collection, storage and visualisation

On top of the regular monitoring usually undertaken by social economy entities, impact measurement requires collecting new information about social needs and external stakeholders, and even counterfactual data. Impact data also need to be retrieved from external stakeholders, creating additional technical and operational hurdles. In the absence of an adequate infrastructure for information and knowledge management, difficulties relating to reliability and compliance with regulatory requirements – particularly on data protection – are very common. Ultimately, the analysis and presentation of impact evidence for reporting and communication may require new equipment that is not yet available in-house. Introducing these new functionalities in the social economy entity’s information system may therefore generate recurring difficulties (OECD, 2021[1]).

Today, social economy entities may tap into an extensive set of online survey tools for remote data collection.9 These tools are not specifically aimed at social economy entities: they are designed for all types of organisations wishing to hear from their customers, stakeholders or beneficiaries. By facilitating the rollout of questionnaire surveys, they help lighten the burden on internal staff and reduce the cost of data collection. The design of the questionnaires, their means of dissemination (emails, SMS, telephone, etc.), the purchase of respondent panels, as well as the more-or-less developed functionalities for exporting, analysing and visualising data, may vary. Although such questionnaires are suitable for questioning the general public and people with full mastery of digital communications, they may be less suited for the specific audiences supported by social economy entities, such as migrants, elderly people and people with disabilities, who may have difficulties in mastering language, different levels of digital literacy, and physical or cognitive impairments (IMISCOE, 2013[19]); (IDEAS, 2021[20]).

Social economy entities can systematise their impact measurement efforts by integrating them into their beneficiary management system. It is generally good practice to integrate, inasmuch as possible, ad-hoc data-collection tools into the existing data infrastructure, since data collected at the earlier stages of a given change strategy (e.g. inputs, activities and outputs) will be relevant for assessing medium-term outcomes and even long-term impacts. Using their own resources or external support, social economy entities can strengthen their information system by developing specific modules dedicated to recurrent impact data collection and analysis. Ideally, these modules provide for collecting longitudinal data about beneficiaries before, after and sometimes during the activities provided by the entity. For instance, in the case of a work integration programme, the information system could be expanded to track (Table 4.2):

the beneficiaries' pre-existing conditions and needs: during the initial interview, go beyond the administrative situation and the level of qualification by recording information on barriers to employment (mobility, language skills, family difficulties, etc.) and their intensity.

the beneficiaries’ conditions at the end of the programme, and the impacts of the support: during the final interview, go beyond the description of the employment situation (contract, duration, etc.) by recording data on the increase in employability, the level of income and even the level of personal fulfilment in the new job.

By integrating the collection of impact data in the relationship with beneficiaries and planning for regular check-ins, social economy entities can achieve systematic data collection, which will significantly lighten the burden of annual (or end-of-project) impact reporting.

Table 4.2. Potentially relevant data for impact measurement

|

Outreach |

Outputs |

Observed changes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

More comprehensive online platforms also exist for collecting, analysing and reporting impact data, some of which cater explicitly to social economy entities.10 These solutions start by developing a theory of change for the organisation, and are thus better suited to the social mission of the social economy. In some cases, large social enterprises, non-profit associations or foundations have developed a customised platform for data collection, often as a spin-off to their existing information technology (IT) infrastructure. These (costly) developments are often sponsored by big players in the digital industry, for instance as an extension of pre-existing solutions for accounting, customer relationships, human resources or patient journey management for health care organisations. Still, the vast majority of available solutions mainly target conventional for-profit companies wishing to fulfil their corporate social responsibility (CSR) commitments.11 Building on existing CSR standards, these solutions typically support the identification and mitigation of potentially harmful externalities.

These different platforms directly underpin the digitalisation, automation and cost reduction of regular impact monitoring. Generally inspired by shared impact management principles, they can be used at the project, programme (portfolio) or organisational level. While they may offer free demonstrations or partial access, most will charge a fixed rate to install them, and then monthly subscriptions. The user journey typically includes:

an initial description of the organisation, its operating model and the social need it is trying to address,

refining the change strategy, often structured around the logical model or causal chains identified by the organisation,

selecting indicators from existing menus (e.g. the IRIS+ Catalog of Metrics), or defining ad-hoc indicators for the expected outputs, outcomes and impacts identified,

defining the corresponding sources and data-collection tools,

directly capturing information from beneficiaries and external stakeholders, or importing datasets produced elsewhere,

optional assistance with analysis, formatting and visualisation of the impact evidence.

Depending on the service provider, significant variations may exist in the modalities for administering the survey (e.g. SMS questionnaire, QR code); advanced analysis functionalities (e.g. monetisation proxies and calculation of the SROI ratio), dashboard visualisations and the guarantees of regulatory compliance on data management. The service provider may also collect data from stakeholders (often suppliers) through blockchain technologies or from online databases, using artificial intelligence technologies. It may also offer extensive integration with existing information systems and direct assistance to improve the user experience. See Box 4.3 and Box 4.4 for examples.

Box 4.3. The SPI Online platform for social and environmental performance management

Freely accessible on the SPI Online platform, the social performance indicators (SPI) are open to all organisations targeting vulnerable and underserved clients, to measure and manage the achievement of their social strategy. Users include purpose-driven financial service providers (such as microfinance institutions and financial cooperatives), social enterprises and NGOs.

The portal offers a full range of free resources, including audit tools, guidelines, template reports, e-learning and access to a network of qualified experts. Its content is aligned with international standards, including the Universal Standards for Social and Environmental Performance Management, standards developed by the International Labour Organization and the OECD (on decent work, human rights, health/security), and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Each organisation can engage at its own pace, according to its own priorities (e.g. social audit, environmental performance or outcomes management). Users select different pathways and choose different tools, depending on their needs (e.g. taking the first step towards improving their social and environmental performance, or conducting a comprehensive assessment of their practices); the indicators to be completed are determined accordingly. Users can visualise the results with dashboards designed to generate actionable insights and benchmark their performance against peers.

One example is the Framework on Outcomes Management, which helps build concrete surveys and data analysis of clients aligned on social goals. Some of the leading questions include: “Do clients have access to financial services for the first time? Do they feel they are treated fairly? Is repayment a burden? What changes do they see in terms of economic growth, gender equality and access to basic needs?” By conducting segmented analysis of social outcomes along client categories (gender, level of income or age) and shedding light on the unintended negative consequences, organisations enhance their understanding of the risks and changes observed, so as to improve their products and services.

Another noteworthy example is the Social Business Scorecard (SBS), a self-assessment tool designed to help social businesses boost their credibility and avoid misusing the concept. The absence of principles to guide practices in a so-called “double-bottom-line” sector opens the door to mission drift and abuse. Social businesses can thus refine their social strategy; define indicators; generate an ergonomic dashboard to share social achievements with board members, investors and partners; and ultimately drive decision-making based on the social mission, thereby enhancing their services to clients.

The audit tools available on the SPI Online platform have been used by more than 800 financial service providers in more than 100 countries, amounting to about 2 000 audits. One-third of the audits were conducted by financial NGOs and cooperatives, either as self-assessments or with the support of external auditors. The tools facilitate participative governance, by equipping members with a common language for general assemblies, concrete assessment and dashboards of their practices, and clear roadmaps for implementation. For instance, several financial cooperatives in Latin America and Africa rely on SPI Online to inform their discussions on impact.

Note: Cerise+SPTF is a joint venture between Cerise, a French non-profit association created in 1998 that has been working on the SPI with committed financial service providers since 2001, and SPTF, which started the Universal Standards for Social and Environmental Performance Management for inclusive finance in 2005. SBS is the result of a three-year collaborative effort led by Cerise with representatives from NGOs, foundations and companies that support social businesses worldwide. While most resources on the SPI Online platform are in English, SBS is only available in French.

Box 4.4. Show Your Heart”, the digital platform that supports Spanish social enterprises and cooperatives in measuring impact and aggregating results

“Show your Heart” (Ensenya el Cor) is an impact measurement software that supports several environmental, social and governance (ESG) accounting methods. It was developed by the Catalan Network of Solidarity Economy (Xarxa d’Economia Solidària de Catalunya [XES]) in 2008 to help members self-assess their commitment to social economy values. By 2016, the solution had been adopted by the Spanish Network of Networks of Alternative and Solidarity Economy (Red de Redes de Economía Alternativa y Solidaria [REAS]) and hence scaled up to the whole national territory. It enables social cooperatives and other legally recognised social enterprises to assess and improve their social and environmental impact, as well as their governance practices.

The “Show your Heart” platform offers 13 sectoral or regional modules or user pathways, allowing adaptation to the entity’s profile (e.g. social cooperatives, social enterprises, non-profits, urban commons), as well as its local and socio-economic context (e.g. specific methods developed by some regional networks within REAS). Each module typically consists of a set of ESG topics, with associated key impact performance indicators and surveys for data collection. All modules share a common set of basic indicators, reflecting the core values of the social economy.

As an example, the Social Balance (Balanç Social) module is expected to be applied annually by XES members, but is open and free for any organisation to use. Besides economic and environmental performance, it covers topics like:

Social commitments: purchase of goods and services from other social economy entities; production of goods, services or materials that are made available at no cost; promotion of functional diversity and social inclusion.

Workplace quality: active measures to promote workplace health and improve work-life balance beyond legal obligations; internal policies improving on the conditions stipulated by collective labour agreements; encouraging the training of workers; ensuring the availability spaces for workers’ emotional and physical care.

Democracy and equity: worker demographics (average age, disability rate, gender disaggregation of management, executive and political positions); participation in the preparation and approval of the management plan and annual budget; online publication of the “Social Balance report”; gap between the highest and lowest remunerations; disclosure of wages to workers; use of non-sexist and inclusive language; adoption, monitoring and evaluation of an equality plan; existence of a protocol for the prevention and handling of sexual harassment.

The data are collected through surveys addressed to organisational managers or, where available, impact measurement leads. The platform also allows deploying stakeholder surveys, which can elicit subjective assessments from workers and business partners. The Social Balance has two variants: a brief version featuring 80 indicators and the complete version (including stakeholder surveys) featuring 200 indicators. Entities with an overall score equal to or greater than four out of ten can download an automatically generated infographic and impact report.

A state-wide, bottom-up, democratic process was followed to agree on a core set of 70 indicators that are common to all ESG accounting methods. These core indicators facilitate the creation of aggregated reports that analyse data from all organisations within the same network at the regional or country level, which in turn demonstrates the overall performance of the social economy and its inherently value-driven behaviour. For instance, they help highlight the low pay gaps and the gender-balance ratios in the sector, and then compare them to the conventional Spanish economy. Thematic reports are also sometimes issued on specific topics (e.g. environmental sustainability, the feminist economy).

Around 700 social economy entities throughout Spain use the online platform every year. “Show your Heart” is licensed as open-source software, and its dissemination is supported by freely available guides and reports. In collaboration with other social economy networks, the tool is being piloted in the Netherlands, with additional opportunities for transposition abroad in the medium term.

Seek independent validation

Like all private-sector actors, social economy entities are increasingly subjected to public scrutiny. Considering the growing importance of impact data in social economy entities’ decision-making (and interactions with stakeholders), and the multiplication of similar approaches in the private sector, entities are increasingly aware of the risk of "impact washing". In response, growing attention is being paid to the robustness of results from the impact measurement process, with the result that it is increasingly common to subject impact claims to some form of independent validation (OECD, 2021[1]).12

There exist several ways to obtain independent validation of impact claims, from functional separation to external audit. Their relevance depends on the means available to the social economy entity and whether the impact measurement processes relied mostly on quantitative monitoring (e.g. regular data collection with impact indicators for management or reporting purposes) or ad-hoc research work (studies based on theoretical frameworks from the social or clinical sciences and relying on primary data collection).

Social economy entities may establish an internal but independent team dedicated to impact measurement. The unit may bring together all the oversight functions, often including audit. Its independence is warranted by the fact that it reports directly to the governing board, rather than line management. Especially in small organisations, the responsibility for impact measurement is often located within the same team that is in charge of operations, fundraising, advocacy or communication.

In cases where the social impact measurement approach mainly consisted of quantitative monitoring of the organisation’s impacts, an audit of impact data can be performed by an independent third party (usually an audit or consulting firm), which primarily ensures the opposability of the data used and disclosed by organisations on their achievements or impacts.13

If the social impact measurement primarily involves research work (rather than monitoring data, as described earlier), an independent expert or peer can review the impact report. This critical review will focus on assessing the validity and reliability of the reported results, also explaining any biases and limitations of the study. It is mainly conducted by researchers with relevant expertise or ad-hoc bodies (e.g. scientific committee or expert committee) formed around the study work.

In practice, some form of independent audit is often imposed when social economy entities decide to seek external recognition of their commitment to impact, for instance through B-Corp certification14 or the BBB Wise Giving Alliance Standards.15 In some cases, the audit may extend to benchmarking among a group of peers, as happens with rankings of charitable organisations.16 In Spain, as part of the Balanç Social systems, 5-10% of respondents are audited every year to guarantee the reliability of the data.

Designating a dedicated team may only be possible in larger entities. Whether resorting to external verification by audit or review, social economy entities must anticipate an additional cost in the impact measurement cycle, mainly associated with the services provided by the independent third party. This additional cost is sometimes difficult to justify for social economy entities with limited resources (OECD, 2021[1]).

To date, there exist no shared or institutionalised quality criteria for social impact measurement in the social economy. The existence of charters (e.g. by the American Evaluation Society or European Evaluation Society) defining the practices of evaluators in the realm of public policies partly addresses this lack. Other initiatives aimed at a more general public and intending to raise critical awareness around social impact measurement can also be identified. See Box 4.5 for a perspective on social impact reports in France. Infographic 4.1 takes a comparative look at the independent verification options.

Box 4.5. A critical perspective on social impact reports (France)

As the impact measurement practice is developing considerably among French social economy actors, it is particularly important to focus on transparency and the quality of reports, analyses and data produced. In 2020, a working group led by Convergences and Avise, comprising evaluation practitioners, social economy entities and funders, developed a practical tool for analysing the quality of impact measurement.

Intended for a broad and non-specialist audience, Mesure d’impact: pour un regard critique (Avise, 2022[25]) assists those who read and use material related to the impact of organisations (such as reports and studies) in their analysis and decryption work by providing objective and consensual guidelines for critical thinking. The proposed critical review process addresses four successive questions:

Nature of data: does the publication actually focus on social impact? Initial guidelines invite the reader to ensure that the information contained in the document actually relates to transformations or social changes occurring as a result of the organisation's activities – and not, for example, to the activities conducted or the satisfaction of beneficiaries.

Intentionality: does the organisation intend to generate this impact? A second set of guidelines invites the reader to analyse the existence and quality of the theory of change developed by the organisation – and thus to distinguish reports relating to the impact from data relating to externalities.

Robustness of the method: was the assessment methodology robust? Acknowledging the need to implement methodologies adapted to each organisation’s context and objectives, the reader is invited to question the validity and reliability of the data and results proposed, and even more, to question the transparency (or lack thereof) around the biases and limits of the publication.

Use of lessons learned: are the data and lessons actually used by the organisation? To distinguish between purely symbolic impact measurement approaches and more desirable approaches that actually influence decision-making, the reader is invited to verify that the organisation has explained the observed or expected impacts of the impact measurement.

While these criteria remain succinct and cannot alone warrant the validity and reliability of quantitative, qualitative or mixed research, they constitute an interesting attempt to raise public awareness on the risk of impact washing.

Source: (Avise, 2022[25]).

Infographic 4.2. A comparative look at independent verification options

Source: OECD.

Establish a permanent action plan to follow up on learnings

Social economy entities with a mature impact management approach will establish a formal process to facilitate the uptake of lessons emerging from the impact measurement cycle. Ultimately, the resulting learnings might lead to a management decision to stop, scale or change an activity (Aps et al., 2017[26]). Concretely, the management process may entail:

Reviewing early findings with internal management: for example, once the impact data become available, the impact measurement lead can organise a meeting to brief and obtain feedback from senior management on the implications.

Developing an action plan to improve operations based on the final impact evidence, explicitly addressing areas of underachievement or unintended consequences: the plan should clearly list the actions to be implemented, their timeframe and the person or team in charge (see Table 4.3).

Submitting a summary of the measurement findings to the governing board or general assembly, accompanied by management recommendations for action based on those findings: if the measurement cycle included external consulting or verification, a formal response may be prepared.

Discussing the learnings and refining the actions to be implemented with employees, members and volunteers during the regular staff meetings or special dissemination events.

Table 4.3. Template for an action plan for following up on the implementation of learnings

|

Finding |

Actions to be implemented |

Person or team in charge |

Timeline |

Progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Indicator, findings, recommendations stemming from impact measurement |

Concrete changes agreed with internal governance and management |

Impact lead, management or staff members |

Short, medium or long term Number of months |

On track/completed Obstacles identified Alternative actions |

|

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

|

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

|

… |

… |

… |

… |

… |

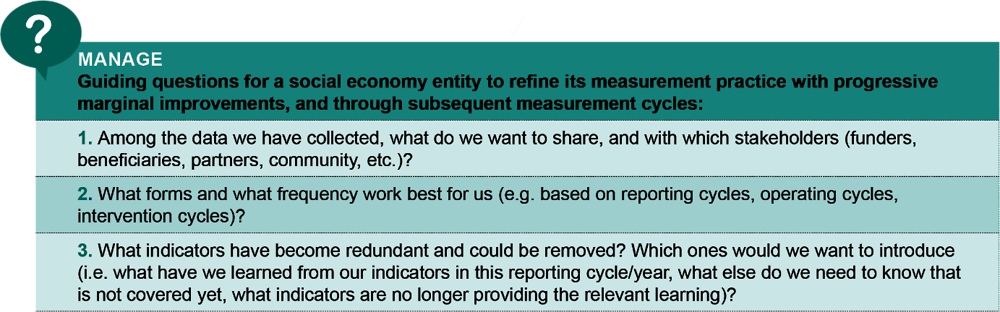

At the end of the impact measurement cycle (especially if it was the first), social economy entities may wish to review the process and identify aspects that may be strengthened. Potential improvements include choosing to collect or manage data in-house, rather than externally; better exploiting new technologies; extending the timeframe to detect longer-term change; investing in staff training; reserving sufficient time (and possibly introducing incentives) for field staff to engage in data collection; strengthening the procedures for data quality checks; and developing dashboards or upgrading software for routine reporting (Sinha, 2017[27]). See Infographic 4.2 for some guiding questions for self-reflection.

In a learning organisation, the impact targets and indicators can be reviewed and adapted over time. Table 4.4 offers a series of questions social economy entities can ask themselves to test and determine the relevance of single indicators in their measurement system (Gray, Micheli and Pavlov, 2015[28]). Obviously, these questions can already be asked about indicators used during each measurement cycle’s design phase, but they become even more relevant in hindsight.

Table 4.4. Checklist for reviewing impact indicators over time

|

Criteria |

Questions |

|---|---|

|

Accuracy |

Is the indicator measuring what it is meant to measure? |

|

Precision |

Is the indicator consistent whenever or whoever it measures? |

|

Access |

Can the data be readily communicated and easily understood? |

|

Clarity |

Is any ambiguity possible in the interpretation of the results? |

|

Timeliness |

Can we collect the data early enough so that action can be taken? |

|

Action |

Have the data been acted upon? What effect has this indicator triggered in terms of management? |

|

Incentives |

What behavioural changes does the indicator encourage? |

|

Cost |

Is it worth the cost of collecting and analysing the data? |

Source: Adapted from (Gray, Micheli and Pavlov, 2015[28]).

Infographic 4.3. provides an overview of impact management touching upon the success factors and pitfalls to avoid.

Infographic 4.4. Success factors and pitfalls in impact management for the social economy

Source: OECD.

References

[21] Aliaga, V. (2022), “Another Economy Is Possible Already Exists”: Making Democratic Worlds One Day at a Time in Barcelona, Doctoral dissertation, Rice University, https://repository.rice.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/25a64dd8-7d59-45f2-b134-979d9fa08943/content.

[23] Alquézar, R. and R. Suriñach (2019), El Balance Social de la XES: 10 años midiendo el impacto de la ESS en Cataluña, United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Solidarity Economy, https://knowledgehub.unsse.org/knowledge-hub/el-balance-social-de-la-xes-10-anos-midiendo-el-impacto-de-la-ess-en-cataluna/.

[26] Aps, J. et al. (2017), Maximise Your Impact: A Guide for Social Entrepreneurs, https://www.socialvalueint.org/maximise-your-impact-guide.

[6] Arvidson, M. and F. Lyon (2014), “Social Impact Measurement and Non-profit Organisations: Compliance, Resistance, and Promotion”, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol. 25/4, pp. 869-886, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43655037.

[25] Avise (2022), Mesure d’impact : pour un regard critique, http://www.avise.org/ressources/mesure-dimpact-pour-un-regard-critique.

[16] Beer, H., P. Micheli and M. Besharov (2022), “Meaning, Mission, and Measurement: How Organizational Performance Measurement Shapes Perceptions of Work as Worthy”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 65/6, pp. 1923-1953, https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.0916.

[12] Brown, J. and J. Dillard (2015), “Opening Accounting to Critical Scrutiny: Towards Dialogic Accounting for Policy Analysis and Democracy”, Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, Vol. 17/3, pp. 247-268, https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2014.989684.

[5] Budzyna, L. et al. (2023), Ventures At The Helm, https://immjourney.com/wp-content/uploads/Ventures-At-The-Helm.pdf.

[13] CECOP (2021), Lasting impact. Measuring the social impact of worker and social cooperatives in Europe: focus on Italy and Spain, https://mcusercontent.com/3a463471cd0a9c6cf744bf5f8/files/b86afc11-1cab-13ff-afd3-d5ec375a8610/CECOP_lasting_impact_digital.pdf.

[24] CECOP (2019), Measuring the social impacte of industrial and services cooperatives in Europe, https://cecop.coop/uploads/file/vqXaL3qDRaYIZxlE39VajDsun2AZ3mVnpvgQY2Be.pdf.

[8] Dupain, W. et al. (2022), The State of Social Enterprise in Europe – European Social Enterprise Monitor 2021-2022, Euclid Network.

[11] European Commission (2020), Social Enterprises and Their Ecosystems in Europe, Publications Office of the European Union, https://europa.eu/!Qq64ny.

[28] Gray, D., P. Micheli and A. Pavlov (2015), Measurement Madness: Recognizing and avoiding the pitfalls of performance measurement, John Wiley & Sons.

[9] Hall, M., Y. Millo and E. Barman (2015), “Who and What Really Counts? Stakeholder Prioritization and Accounting for Social Value”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 52/7, pp. 907-934, https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12146.

[15] Hehenberger, L. (2023), “Prioritizing Impact Measurement in the Funding of Social Innovation”, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Vol. 21/2, pp. 74-75, https://doi.org/10.48558/SHQ7-VK20.

[2] HIGGS, A. et al. (2022), Methodological Manual for Social Impact Measurement in Civil Society Organisations, https://measuringimpact.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Methodological-Manual-English.pdf.

[20] IDEAS (2021), Evaluation in contexts of fragility, conflict and violence, https://ideas-global.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/EvalFCV-Guide-web-A4-HR.pdf.

[19] IMISCOE (2013), Surveying Migrants and Minorities, https://www.imiscoe.org/docman-books/354-font-a-mendez-eds-2013/file.

[4] IMP (2023), , https://impactmanagementplatform.org/actions/.

[3] IMP (2023), Impact Management Platform: Manage impact for organisations.

[32] Impact Track (n.d.), , https://impacttrack.org/fr/.

[33] Impact Wizard (n.d.), , https://socialvalueuk.org/impact-wizard-magic-impact-assessment/.

[34] ImpactSo (n.d.), , https://impactso.com/.

[17] Kingston, K. et al. (2023), “Avoiding the accountability ‘sham-ritual’: An agonistic approach to beneficiaries’ participation in evaluation within nonprofit organisations”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 92, p. 102261, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2020.102261.

[35] Makerble (n.d.), , https://about.makerble.com/.

[18] OECD (2023), Policy Guide on Social Impact Measurement for the Social and Solidarity Economy, Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/270c7194-en.

[7] OECD (2023), What is the social and solidarity economy? A review of concepts, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2023/13, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/dbc7878d-en.

[1] OECD (2021), “Social impact measurement for the Social and Solidarity Economy”, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2021/05, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d20a57ac-en.

[30] OECD (2016), Understanding Social Impact Bonds, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/UnderstandingSIBsLux-WorkingPaper.pdf.

[10] Ometto, M. et al. (2018), “From Balancing Missions to Mission Drift: The Role of the Institutional Context, Spaces, and Compartmentalization in the Scaling of Social Enterprises”, Business & Society, Vol. 58/5, pp. 1003-1046, https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650318758329.

[27] Sinha, F. (2017), Guidelines on outcomes management for financial service providers, https://sptf.info/images/Guidelines-on-Outcomes-Management-for-FSPs.pdf.

[31] Social Value Engine (n.d.), , https://socialvalueengine.com/platform-features-and-benefits/.

[29] SoPact (n.d.), , https://www.sopact.com/.

[14] World Economic Forum (2017), Engaging all affected stakeholders: guidance for investors, funders, and organisations., https://sptf.info/images/SIWG-WEF-AG3-Engaging-all-affected-stakeholders-December-2017.pdf.

[22] XES (n.d.), Balance Social, https://xes.cat/es/comisiones/balance-social/.

Notes

← 2. “Social Impact Strategy: Tools for Entrepreneurs and Innovators”: www.coursera.org/learn/social-impact.

← 3. “Évaluation & Mesure d'Impact Social” (in French): www.coursera.org/learn/evaluation-mesure-impact-social.

← 4. www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/programmes/executive-education/person-programmes/oxford-impact-measurement-programme.

← 9. Several partially or completely free access tools can be cited as examples: FrontlineSMS, Kobo Toolbox, HubSpot Free Online Form Builder, SurveyMonkey, SurveySparrow, Lucky Orange, ProProfs Survey Maker, LimeSurvey, Delighted, Survicate, Sogolytics, Typeform, Qualtrics, SurveyPlanet, Google Forms, Alchemer, SurveyLegend, Zoho Survey, Crowdsignal, Survs and FreeOnlineSurveys.

← 10. Several platforms can be cited as examples: Impact Track (France) (Impact Track, n.d.[32]), Social Value Engine (Social Value Engine, n.d.[31]), ImpactSo (Czech Republic) (ImpactSo, n.d.[34]), Makerble (United Kingdom) (Makerble, n.d.[35]), SoPact (United States) (SoPact, n.d.[29]) and Impact Wizard (Belgium) (Impact Wizard, n.d.[33]).

← 11. Several solutions can be cited as examples: MASImpact (Spain), Social Value Portal (United Kingdom), Impact reporting (United Kingdom), Impaakt (Czech Republic), Leonardo (Germany), Impact Software (Netherlands) and Social Handprint (Netherlands).

← 12. Depending on the type of social impact measurement work conducted, different notions can be used to reflect on the quality of impact data and reports. When the data collection relies mainly on quantitative monitoring, it is opposability. In the context of auditing, opposability refers to the ability of data to be used as evidence by relevant stakeholders. An opposable conclusion can be relied upon in regulatory, financial or decision-making actions. When the data collection relies on research work, the notions are validity and reliability. In social science, validity refers to the extent to which a measurement instrument assesses what it is intended to assess. In other words, a measurement is considered valid if it accurately measures what it claims to measure. Social economy entities need to consider two types of validity: internal validity, which ensures that the impacts highlighted are indeed attributable to the action evaluated, and external validity, which ensures that the conclusions of the study are indeed applicable beyond the beneficiaries observed in the study. “Reliability” refers to the consistency and stability of a measurement. It indicates to what extent the results of a measurement are reproducible and consistent. A measurement is considered reliable if it produces similar results when repeated under similar conditions. The biases and limits of the ensuing report should typically be discussed using validity and reliability concerns.

← 13. This approach was notably illustrated in the context of the verification of data produced by organisations involved in social impacts bonds (OECD, 2016[30]). Several standard-setting organisations are currently working on defining or refining the impact reporting or management practices underpinning the verification, including the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), IRIS+, the “Operating Principles for Impact Management” (OPIM), the “Principles for Responsible Investment” (PRI), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the “Social Bond Principles” (SBP).

← 16. See, for example: www.charitynavigator.org; www.givewell.org.