This chapter describes the current corporate landscape in ASEAN economies, provides trends in the use of equity and corporate bonds markets and discusses issues related to capital market development that deserve special consideration. It starts by describing the current use of market-based financing versus bank financing in the region and provides an overview of the current marketplaces for equity and corporate bonds in ASEAN economies. It follows by providing a characterisation of the corporate sector with respect to its capital structure, profitability and investment, and describes the trends in the use of equity and corporate bond markets. The chapter also discusses selected issues related to the development of capital markets in the region and policy considerations that deserve attention from ASEAN authorities.

Mobilising ASEAN Capital Markets for Sustainable Growth

1. Corporate landscape and the use of capital markets in ASEAN economies

Abstract

1.1. Introduction

Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, ASEAN economies made significant efforts to enhance market resilience. A series of reforms aimed at stabilising the macroeconomic landscape and extending jurisdiction-level initiatives into regional efforts were introduced. Against this background, operating as a block laid the foundations for economic growth in the region. ASEAN represents today a dynamic economic region characterised by diverse cultures, vibrant trade and robust economic growth. At the heart of this economic dynamism lies the corporate sector responsible for investing, innovating and creating jobs to ultimately contribute to sustainable economic growth.

This chapter delves into the pivotal role the corporate sector plays in driving economic growth and the essential role capital markets have in enabling this growth. Well-functioning capital markets provide corporations with the necessary funds to finance expansion, innovation and strategic initiatives. They offer corporations the flexibility to optimise their capital structure, manage risks and enhance shareholder value. Beyond the corporate realm, robust capital markets contribute to broader economic prosperity by channelling savings into productive investments, spurring job creation and driving technological advancements. They serve as engines of economic growth, facilitating the efficient allocation of resources and promoting financial stability. As such, well-functioning capital markets not only empower businesses to thrive but also underpin the foundation of a resilient, dynamic and sustainable economy.

1.2. The use of market-based financing in ASEAN economies

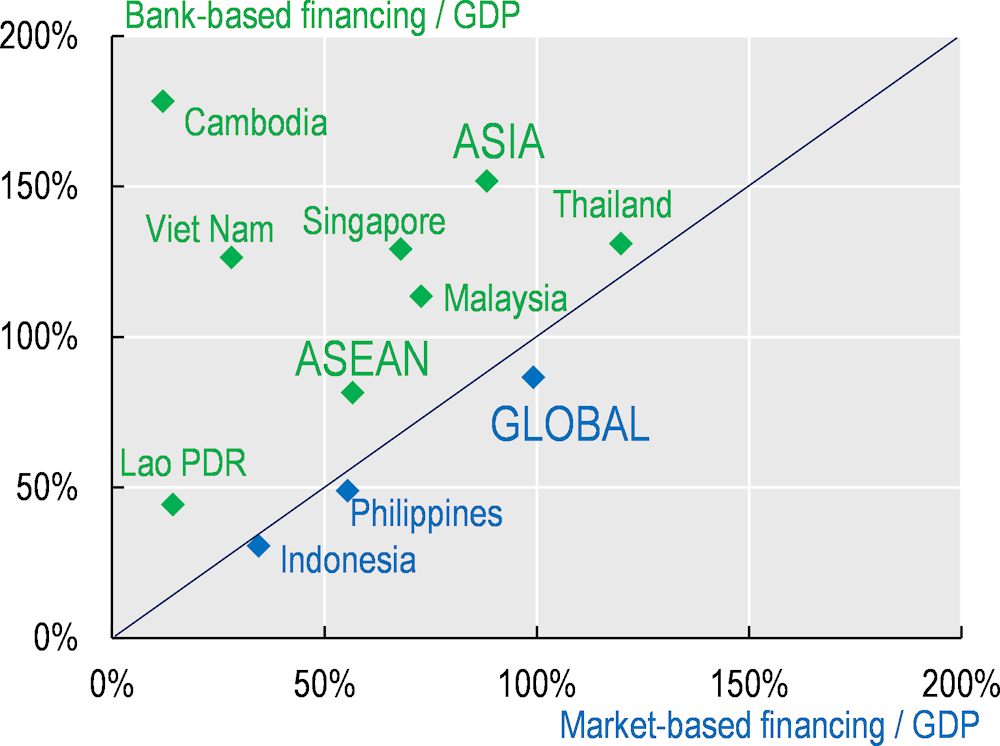

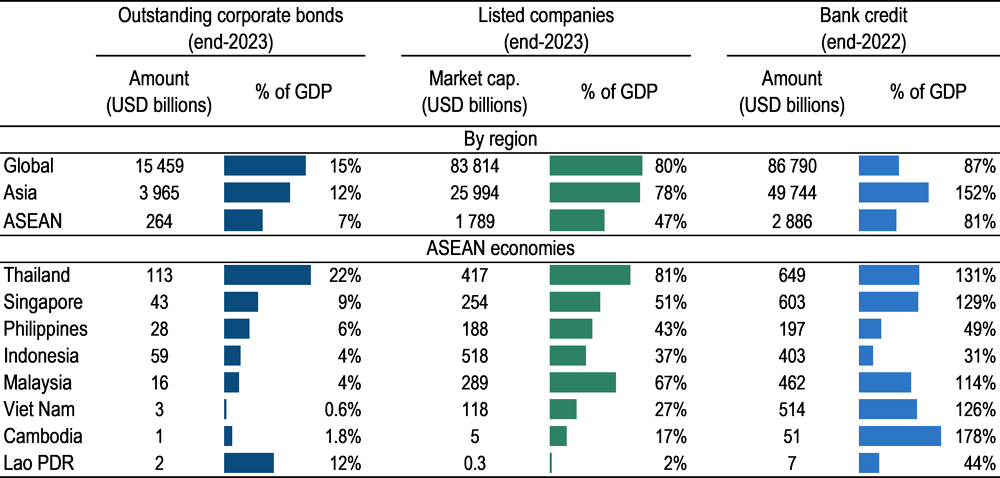

ASEAN economies have implemented various capital markets reforms to improve the availability of market‑based financing for corporations, while also facilitating the allocation of resources towards innovative and sustainable businesses. While, globally, market-based financing has grown in importance representing in 2022 a larger share of GDP (99%) than bank credit (87%), ASEAN economies and Asia in general, still show a high reliance on bank financing (Figure 1.1).

Bank credit to the non-financial corporate sector in ASEAN economies represents 88% of GDP whereas in Asia bank financing represents 152% of the region’s GDP. In Asia, despite the increasing use of public equity and corporate bonds, companies still heavily rely on bank credit to finance their activities. In ASEAN markets both market- and bank-based financing remain limited representing less that the region’s GDP. Compared to Asia, the low share of bank financing in ASEAN economies is mostly driven by the limited size of the financial system.

The financing structure of corporations shows further differences across ASEAN economies (Figure 1.1). Only in Indonesia and the Philippines, market-based financing to GDP is slightly higher than bank-based financing. However, this is mainly driven by the small size of the total financing in these two economies. In other ASEAN economies bank-based financing dominates. Cambodia shows the highest reliance on bank financing and the lowest use of market-based financing. Bank credit to GDP represents 178% of GDP, while market-based financing accounts for only 8%. Thailand, on the contrary, shows the highest use of market-based financing at 120% of GDP and also a strong use of bank loans (131% of GDP).

Figure 1.1. Market-versus bank-based financing use by non-financial companies, end-2022

Notes: Market-based financing is defined as the sum of the market capitalisation of non-financial listed companies and the outstanding amount of non‑financial corporate bonds. Bank-based financing is defined as bank credit to non-financial corporations. Both measures are expressed as share of GDP in the figure. For Lao PDR credit to non-financial corporations was not available and therefore credit to the private sector was used instead.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, Bank for International Settlements, World Bank, October 2023 World Economic Outlook dataset, LSEG.

1.3. Marketplaces for equity and corporate bonds in ASEAN economies

Marketplaces for listing and trading public equity and corporate bonds play a vital role in supporting the use of market-based financing by non-financial corporations and, at the same time, in attracting investors to capital markets. ASEAN economies have made great efforts to develop their marketplaces. All ASEAN countries covered in this report have one stock exchange, where both stocks and bonds can be traded. Viet Nam is the exception with two stock exchanges. The first stock exchanges in the region were established in Indonesia and Philippines in the early 1900s. However, these stock exchanges underwent significant changes since their establishment.1 In contrast, Lao People's Democratic Republic (hereafter “Lao PDR”) and Cambodia established their stock exchanges recently, in 2010 and 2011, respectively. Both stock exchanges were established as joint ventures with the Korea Stock Exchange, which still retains part of the ownership (Table 1.1). In Viet Nam, the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HOSE) and the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX) were established in 2007 and 2009, respectively.

Out of the nine ASEAN stock exchanges, five are state-owned,2 three are publicly listed and the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) is privately owned. Among the publicly listed stock exchanges, the Singapore Exchange was the first to go public in 2000, followed by the Philippine Stock Exchange in 2001 and Bursa Malaysia in 2005.

A majority of the ASEAN stock exchanges operate at least two different segments: a main market for established companies, and a market targeted to smaller and younger companies usually referred as growth market. However, the Lao Securities Exchange, and the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange only have a main segment. In Thailand and Indonesia, the stock exchanges offer additional segments. The Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) further distinguishes between Thai medium-sized companies, traded on the Mai segment, and small companies and startups, traded on Livex. The Indonesia Stock Exchange offers an intermediate segment between the growth market and the main market, the development market. Moreover, among companies listed on the main market, the Indonesia Stock Exchange further classifies companies depending on their technological intensity. Those highly intense in the use of technology to create innovative products and services are listed on the main-new economy market.

Growth markets in the region are characterised by less stringent listing requirements and lower fees to allow younger and smaller companies to access funding. Companies applying to be listed on the ACE market in Malaysia and on the catalist market in Singapore do not need to satisfy any operating track record or profit requirement. In Indonesia, the acceleration market does not set any operational requirement, against the 36 months needed to be listed on the main market. As examples of lower fees on the growth markets, in Cambodia, the initial listing fee on the main market is more than twice that on the growth market.3 Similarly, in the Philippines the minimum annual listing fee on the main market corresponds to the maximum annual fee on the SME market. 4

Table 1.1. Stock Exchanges in ASEAN economies

|

Jurisdiction |

Stock Exchange |

Year of establishment |

Ownership structure |

Segments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cambodia |

2011 |

State-owned by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (55%) and the Korea Stock Exchange (45%) |

Main market Growth market |

|

|

Indonesia |

1912 |

Privately-owned |

Main market New Economy (main market) Development Acceleration (growth market) |

|

|

Lao PDR |

2010 |

State-owned by the Bank of Lao PDR (51%) and the Korea Stock Exchange (49%) |

Main market |

|

|

Malaysia |

1964 |

Publicly-owned |

Main market ACE (growth market) LEAP (growth market for qualified investors) |

|

|

Philippines |

1927 |

Publicly-owned |

Main market SME (growth market) |

|

|

Singapore |

1973 |

Publicly-owned |

Main market Catalist (growth market) |

|

|

Thailand |

1962 |

State-owned |

SET (main market) Mai (medium-sized companies) Livex (growth companies) |

|

|

Viet Nam |

2007 |

State-owned |

Main market |

|

|

2009 |

State-owned |

Main market UPCoM (unlisted public companies) |

Notes: The year of establishment refers to the date when the first stock exchange was established in the country. For Indonesia it refers to the year the stock exchange was established by the Dutch East Indies government as a branch of the Amsterdam stock exchange. For Thailand it refers to the year the Bangkok Stock exchange was established (failed in the early 1970s).

Source: Stock exchanges website, links are provided in the “Stock Exchange” column of the table.

1.4. Corporate landscape in ASEAN economies

This section provides an overview of the corporate landscape in ASEAN economies with a specific focus on companies using market-based financing. In particular, it provides a description of the number and size of listed companies in the region, their capital structure, profitability and investment developments, and compares it with global and Asian figures.

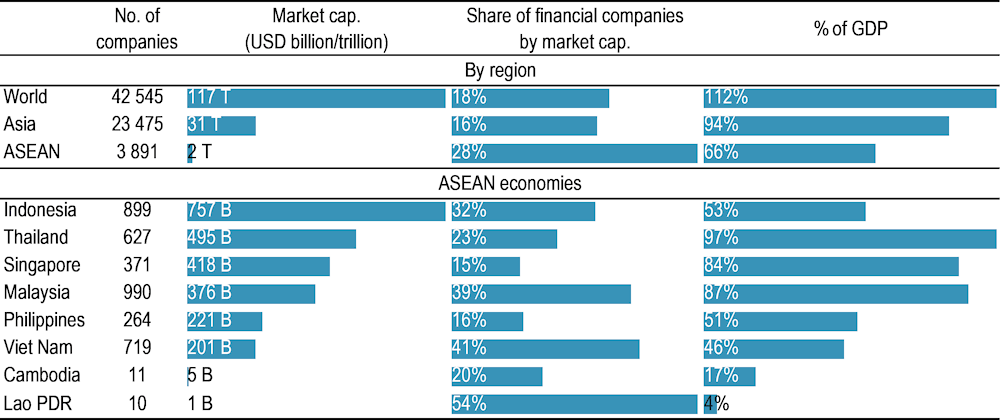

A total of 3 891 companies were listed on ASEAN exchanges by the end of 2023, with a market capitalisation representing 66% of the region’s GDP (Figure 1.2). The size of the listed sector differs widely across countries, ranging between 84% and 97% as share of GDP in Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand, to much lower levels in Lao PDR, Cambodia, Viet Nam, Philippines and Indonesia. Lao PDR and Cambodia have smaller equity markets with market capitalisation to GDP ratios of only 4% and 17%, respectively. Although Indonesia is the biggest market in terms of market capitalisation (USD 757 billion), as share of GDP is relatively low, at 53%. Measured by the number of listed companies, Malaysia ranks first by listing 25% of all the listed companies in ASEAN markets.

An important feature of equity markets in ASEAN economies is the large share financial companies represents in total market capitalisation compared to Asia and globally. In ASEAN markets, financial companies represent 28% of the total market capitalisation as opposed to 16% in Asia and 18% globally. Lao PDR has the highest share of financial companies (54%) in total market capitalisation, followed by Viet Nam (41%) and Malaysia (39%).

Figure 1.2. Listed companies in ASEAN economies, end of 2023

Notes: “T” stands for trillion and “B” stands for billion. The GDP used in the calculations corresponds to 2023 forecast. Market capitalisation for Cambodia was collected from the Securities Commission of Cambodia.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, Securities Commission of Cambodia, October 2023 World Economic Outlook dataset, see Annex for details.

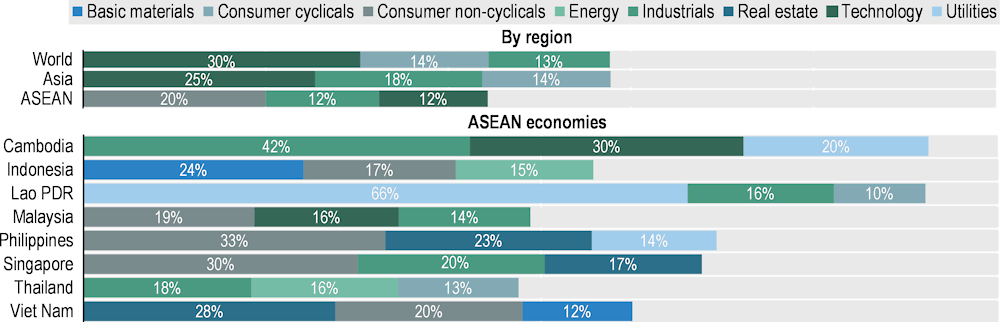

Excluding the financial sector, the consumer non-cyclicals industry is prominent in ASEAN economies, representing 20% of the regional market capitalisation (Figure 1.3). This is well above the levels observed in Asia and globally, where consumer non-cyclicals accounts for only 10%. At the country level, the consumer non-cyclicals industry is dominant in Philippines (33%), Singapore (30%) and Malaysia (19%); and is the second most important in Viet Nam (20%) and Indonesia (17%). In Thailand, consumer non‑cyclicals companies only represent 13% of total market capitalisation, while Cambodia and Lao PDR do not have listed companies from that industry.

In ASEAN markets, technology despite ranking third, is less prominent compared to Asia and globally. Indeed, it only represents 12% of market capitalisation against 25% in Asia and 30% globally. Contrary to most ASEAN peers, Viet Nam’s market is dominated by real estate companies representing 28% of the market capitalisation. Notably, in Lao PDR two-thirds of the market capitalisation corresponds to utilities, and in Cambodia 42% corresponds to industrial companies.

Figure 1.3. Top 3 industries by market capitalisation in ASEAN economies, end of 2023

Notes: This figure shows only the top three industries (excluding financials) by the share they represent in total market capitalisation.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, Securities Commission of Cambodia, see Annex for details.

1.4.1. Capital structure

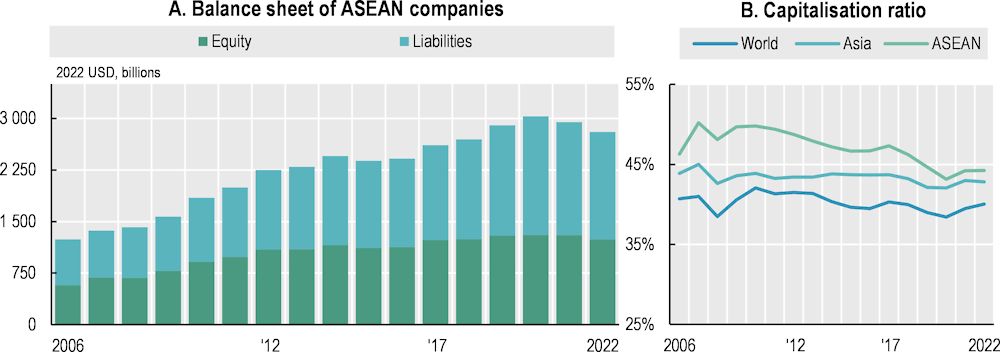

The aggregate balance sheet of ASEAN listed companies expanded substantially over the past years, growing in real terms 126% between 2006 and 2022, in line with the expansion in the number of listed companies in the region (Figure 1.4, Panel A). While a larger aggregate corporate balance sheet is auspicious, in recent years, this has been mainly driven by a rapid increase in liabilities. Between 2017 and 2020, liabilities grew 25% while equity grew only 6%. The rise in liabilities is also reflected in the fall of the capitalisation ratio (equity over assets) over the same period (Panel B). In 2020, the capitalisation ratio fell to 43%, the lowest level since 2006, as a result of increased borrowing in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. In general, capitalisation levels in ASEAN corporations have been converging to those observed in Asia and globally.

Figure 1.4. Balance sheet of non-financial listed companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details

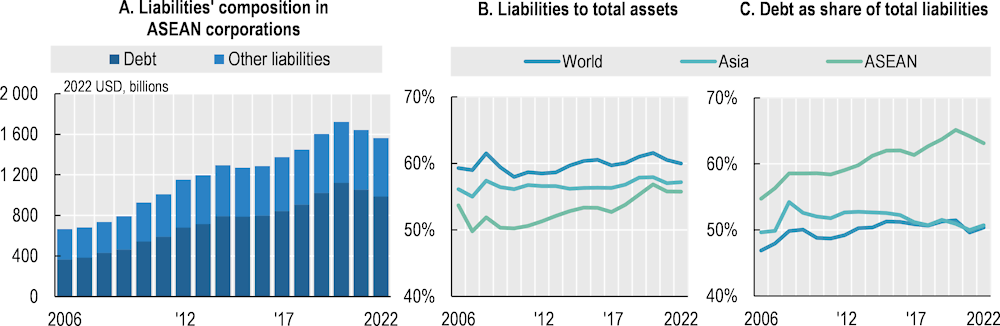

Liabilities of ASEAN corporations, primarily consisting of financial debt and accounts payable, have steadily increased from 2006 to 2022, reaching a peak in 2020 due to heightened borrowing requirements and financial distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Total liabilities increased from USD 666 billion in 2006 to USD 1 563 billion in 2022, representing an annualised growth of 5.5% (Figure 1.5, Panel A). However, both in 2021 and 2022, total liabilities contracted 5% compared to the previous year.

Similarly, aggregate liabilities to total assets have grown considerably, reaching 56% in 2022 from the lowest level of 50% in 2007 (Figure 1.5, Panel B). However, from 2006 to 2022 liabilities in ASEAN corporations have consistently remained lower compared the levels observed in Asia and globally. Notably, financial debt (bank loans and debt securities) has consistently grown in ASEAN corporations since 2006 and has always surpassed the levels observed in Asia and globally. The share of financial debt over total liabilities reached 65% in 2020, the highest level since 2006, before falling to 63% in 2022 (Panel C).

Figure 1.5. Liabilities’ structure of non-financial listed companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details

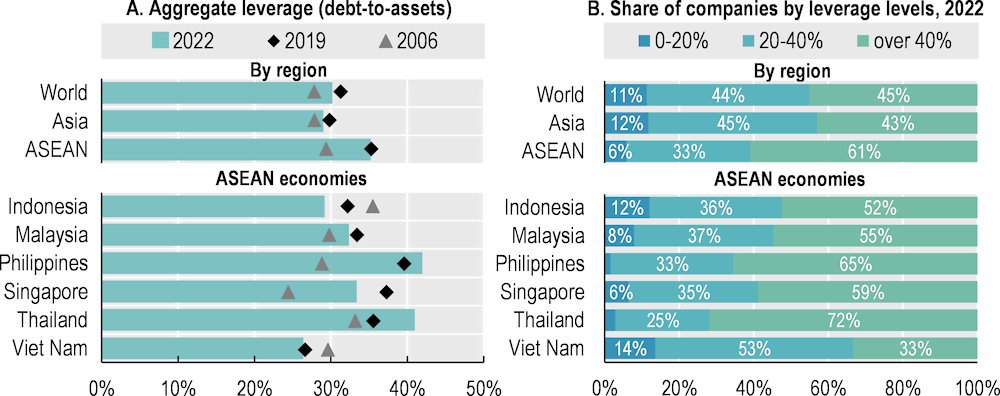

When measuring leverage as debt over total assets, ASEAN companies’ leverage stood at 35% in 2022, higher than that of companies in Asia (29%) and globally (30%) (Figure 1.6, Panel A). At the country level, corporate leverage also shows significant differences. In 2022, aggregate leverage in companies from the Philippines and Thailand was 42% and 41%, respectively, considerably higher than that of companies in other ASEAN economies. Moreover, leverage in ASEAN corporations experienced a surge during the COVID-19 pandemic and returned to 2019 levels in 2022, consistent with global trends. Thailand and the Philippines were the exception to that trend since corporate leverage further increased 5 and 2 percentage points between 2019 and 2022, respectively.

In line with higher aggregate indebtedness of ASEAN corporations, the share of companies with significantly high leverage is also larger in ASEAN economies. While 6 out of 10 ASEAN companies have leverage levels over 40%, in Asia and globally this is the case only for 43% and 45% of the companies, respectively. At the same time, the share of ASEAN companies with low leverage is around a half of that in Asia and the world. At the country level, Thailand accounts for the largest share of highly indebted companies (72%), followed by the Philippines and Singapore (Figure 1.6, Panel B). In general, higher leverage lowers the ability of corporations to withstand sudden shocks.

Figure 1.6. Corporate leverage of non-financial listed companies

Notes: Debt-to-assets ratio is calculated using only financial debt. In Panel B, the distribution of leverage by levels is made based on the share of financial debt that falls in each interval of leverage.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

1.4.2. Profitability

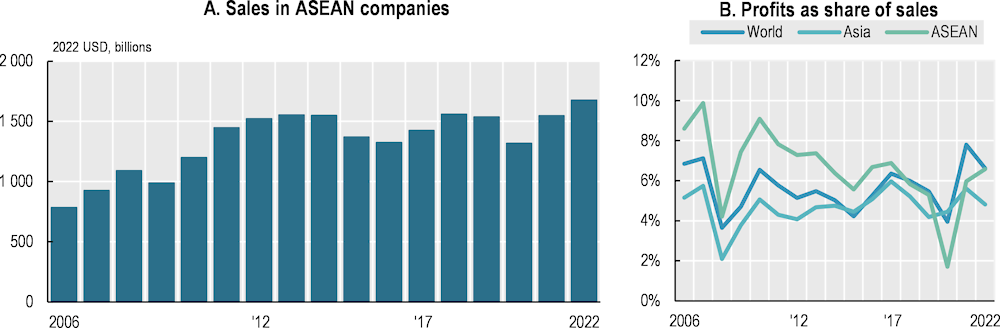

ASEAN corporate sales have continuously increased between 2006 and 2014, almost doubling in real terms from USD 784 billion to USD 1 549 billion (Figure 1.7, Panel A). However, since 2014 sales have fluctuated without showing the growth observed in the previous period. Notably, in 2020, sales contracted by 14% as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Profitability, measured as net income over sales, followed a declining trend in the ASEAN region for most of the analysed period (Panel B). Only in 2009 and 2010, during the recovery from the global financial crisis, and during 2021 and 2022, after the sharp decline experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, profits were on the rise. Notably, profitability among ASEAN corporations experienced a stronger contraction during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to corporations in Asia and globally. In 2022, both sales and profits continued to increase, with sales hitting the highest level (USD 1 675 billion) since 2006, and profits recorded 7% of sales. Overall, profits in ASEAN corporations are converging to Asian and global levels.

Figure 1.7. Sales and profits of non-financial listed companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

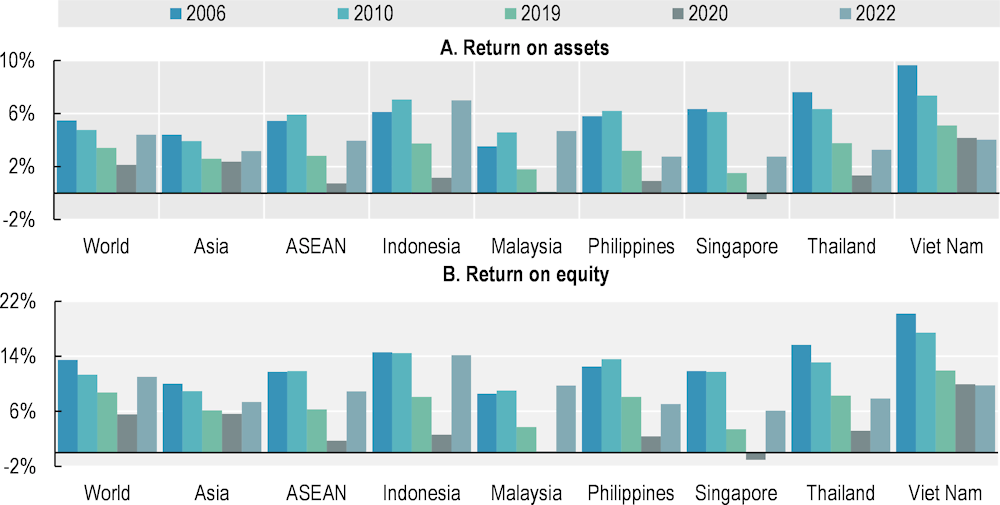

Profitability, both measured in terms of return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE), has also been declining in the majority of ASEAN economies since 2006, with a sharp drop observed between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 1.8). For instance, ROA in ASEAN companies recorded a decline from 6% to 3% between 2010 and 2019 while ROE fell from 12% to 6% over the same period. While the decline in profitability was also observed in Asia, and across the globe, it was much more pronounced for ASEAN corporations. In 2020, profitability contracted across regions as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, ASEAN corporate profitability recovered considerably with ROA and ROE reaching 4% and 9%.

A similar trend is observed across ASEAN markets, however some differences are worth noting (Figure 1.8). Despite the overall decline in profitability observed in all ASEAN markets and globally during 2020, Viet Nam experienced a moderate decline compared to regional peers. Indeed, in Viet Nam, corporate profitability has been higher than its peer countries. In 2020, ROA and ROE only fell from 5% to 4%, and 12% to 10%, respectively. These levels were considerably higher compared to those observed in other ASEAN economies where profitability fell more sharply in 2020. It is also worth noting that Indonesian and Malaysian companies recovered quickly from the contraction observed in 2020 reaching high profitability levels in 2022.

Figure 1.8. Profitability of non-financial listed companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

1.4.3. Productivity and investment

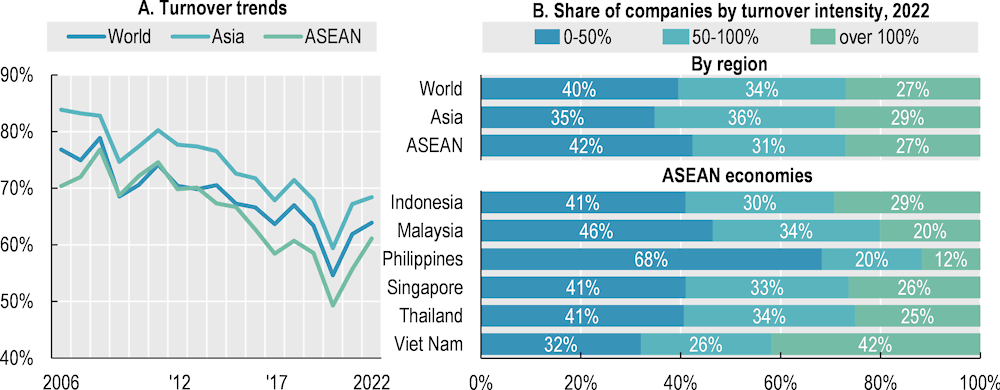

Productivity5 of non-financial listed companies in ASEAN markets has decreased over the 2006-22 period, following Asian and global trends. This decline reflects a mismatch between rapidly expanding assets (see Figure 1.4) and stagnant sales, suggesting a loss of operating efficiency for corporations in ASEAN economies. The median turnover ratio in ASEAN corporations fell from 70% to 58% between 2006-17 (Figure 1.9, Panel A). In 2020, the asset turnover ratio hit 49%, the lowest level observed since 2006. This ratio recovered in 2022 driven by an increase in sales.

The level of asset turnover varies also varies across regions. In the ASEAN region, 42% of companies has asset turnover of less than 50%, meaning that one dollar in asset generates less than 50 cents in sales (Figure 1.9, Panel B). This compares with lower levels of less productive companies of 40% at the global level and 35% in Asia. The share of companies with asset turnover between 50-100% is only 31% in the ASEAN region, lower than the 36% in Asia and 34% globally. The share of productive companies with asset turnover ratios over 100% stood at 27% in the ASEAN region, in line with the global share and below that of Asia at 29%.

Differences in companies’ productivity are more visible across countries (Figure 1.9, Panel B). While the Philippines has the highest share of less efficient companies at 68%, this share stands at 41% for Indonesia, Singapore and Thailand. Viet Nam has the lowest share of less productive firms at 32% and the highest proportion of productive companies (asset turnover over 100%) at 42%. Less differences are observed in the share of companies with asset turnover between 50-100%, ranging from 26% to 34%. Again, the Philippines stands out with only 20% of companies having an asset turnover between 50-100% and only 12%, the lowest share among ASEAN economies, of most efficient companies.

Figure 1.9. Asset turnover ratio of non-financial listed companies

Notes: Asset turnover ratio is measured as total sales divided by total assets. Panel A shows for each region the median values.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

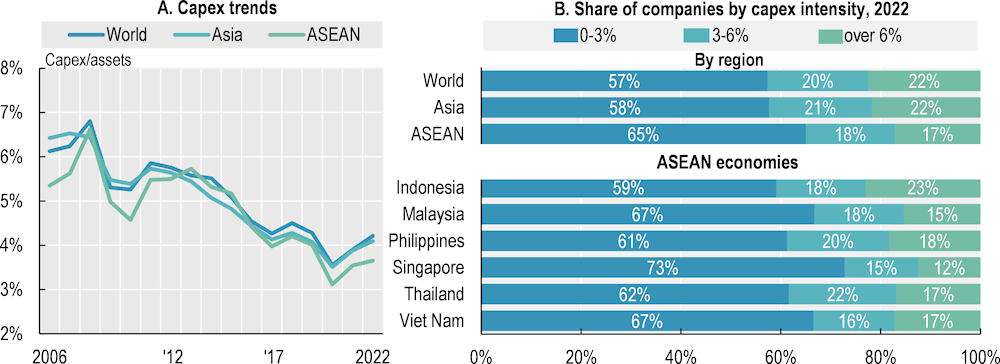

Investment in capital expenditure (capex) by ASEAN corporations has moved closer to global and Asian trends. Across region, investment in capital expenditure has been on a declining trend since 2011 reaching the lowest point in 2020 (Figure 1.10, Panel A). The contraction in investment in 2020 was stronger in ASEAN corporations and the recovery has been slower than in other regions.

In 2022, the ASEAN region showed the largest share of companies (65%) with low levels of investments (less than 3% of the assets) when compared to Asia and globally at 58% and 57% respectively (Figure 1.10, Panel B). Moreover, differences are more pronounced at the country level. Across ASEAN economies, Malaysia, Singapore and Viet Nam stand out with a high share of companies with low investment in fixed capital. Indonesia not only few companies with low investment, but also has almost one-quarter of firms investing in capex over 6% of assets.

Figure 1.10. Investment in capital expenditure by non-financial listed companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

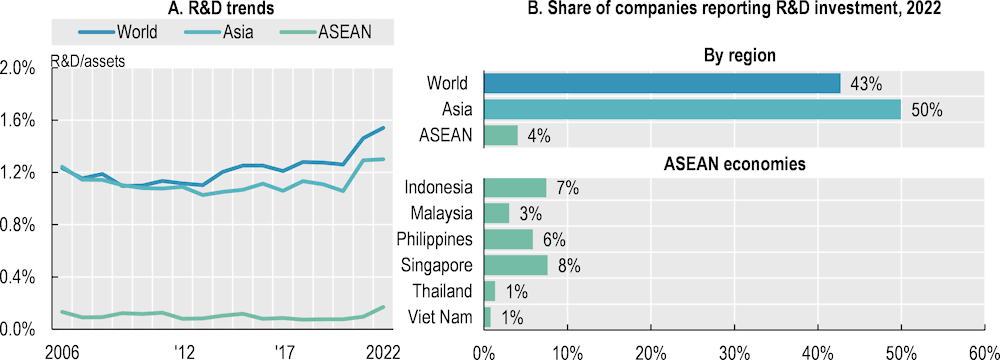

Differently to investment in capital expenditure, investment in research and development (R&D) is much lower in the ASEAN region compared to Asia and globally (Figure 1.11, Panel A). While R&D has been increasing globally and in Asia over the last years, the increase has been minor in the ASEAN region. Investment in R&D is a key driver of economic growth and enhances the competitiveness of economies and corporations in the global market. Moreover, it fuels the development of new industries, improves productivity and creates high-quality jobs. However, the success of R&D investment is highly uncertain and the resulting assets are intangible, therefore, the use of debt is of limited value for this type of investment. Debtholders in general prefer to use physical assets to secure loans and are reluctant to lend when the project involves substantial R&D investment. Well-functioning capital markets, in particular equity markets, allows corporations to fill the R&D financing gap enabling economies to exploit the benefits of innovation in terms of productivity and growth.

Figure 1.11. Investment in research and development by non-financial listed companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

The difference is also striking when looking at the share of companies investing in R&D (Figure 1.11, Panel B). While globally and in Asia, 43% and 50% of listed companies, respectively, reported R&D in 2022, only 4% of companies did so in ASEAN economies. At the country level, the share of companies investing in R&D remains small. Countries like Indonesia, Singapore and Philippines show a higher share of companies investing in R&D relative to the regional aggregate. On the other end, not many firms invest in R&D in Malaysia, Thailand and Viet Nam.

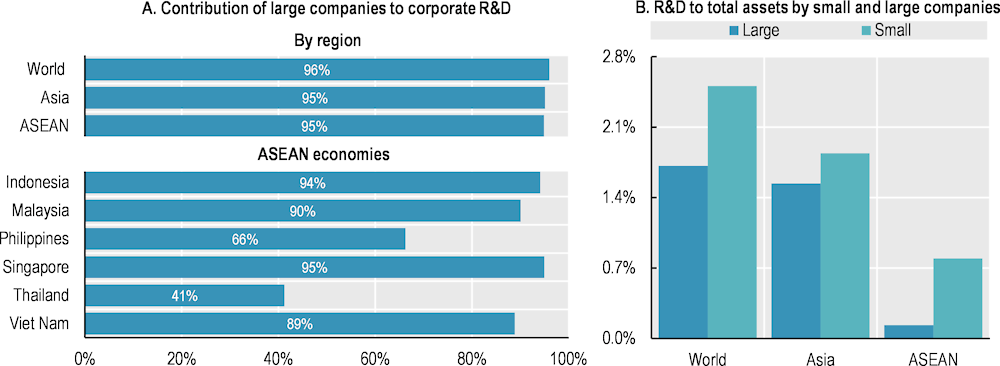

Most of the R&D investment across regions is done by large companies (Figure 1.12, Panel A). They account for more than 95% of the total R&D investment in Asia, ASEAN and globally. This holds true at the country level, with the exception of Philippines and Thailand, where the contribution of large companies was considerably lower than their regional peers, at 66% and 41% respectively. Smaller companies have a minor contribution to aggregate R&D. However, when investment in R&D is scaled by assets, the relationship reversed, and smaller companies show a higher R&D ratio globally, in Asia and in the ASEAN region (Panel B).

Figure 1.12. R&D investment of non-financial companies by size, end of 2022

Notes: Panel B shows the median value of R&D to assets for each region. Companies with assets larger than the median asset size of each group are categorised as large companies. In Panel B, only companies with reported R&D are included.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

1.5. ASEAN companies’ use of public markets

ASEAN economies have seen an increased activity in recent years in both corporate bond and public equity markets. By the end of 2023, market-based financing in the region represented 54% of GDP, a much lower share than that of bank financing (81%).6 The use of capital markets by non-financial ASEAN companies remains somewhat limited. The ratio of market capitalisation of listed companies to GDP and the amount of outstanding corporate bonds to GDP in 2023 was lower in ASEAN region than in Asia and the world. In particular, in 2023, market capitalisation of ASEAN listed companies reached USD 1.8 trillion representing 47% of region’s GDP while non-financial companies had USD 264 billion in outstanding corporate bonds, equivalent to 7% of the region’s GDP (Figure 1.13).

At the country level, significant differences exist in the development and the use of capital markets. At the more developed end, Thailand ranks first in terms of market capitalisation of non-financial listed companies and the outstanding amount of corporate bonds, even surpassing global figures as share of GDP. Indonesia follows with the second highest outstanding amount of corporate bonds and market capitalisation. However, as share of GDP, market-based financing is among the lowest in the region suggesting that capital markets are not contributing enough to the intermediation of financing in the economy. In Malaysia, the stock market is more developed with market capitalisation representing 67% of GDP while the outstanding amount of corporate bonds to GDP remains low, at 4%. On the other end, Cambodia and Lao PDR have the least developed capital markets in the region.

Figure 1.13. Overview of non-financial companies’ use of market-based financing and bank credit

Notes: Bank credit refers to bank credit to non-financial corporations, except for Lao PDR, where credit to non-financial corporations was not available and credit to the private sector was used instead. The GDP values used to compute the size of the corporate bond and equity markets corresponds to 2023 forecast values. Market capitalisation for Cambodia was collected from the Securities Commission of Cambodia. Non‑financial corporate bond data excludes convertible bonds, deals that were registered but not consummated, preferred shares, sukuk bonds, bonds with an original maturity less than or equal to one year or an issue size less than USD 1 million. Non‑financial listed companies’ data excludes units, trusts, secondary listings, firms trading on over-the-counter markets and those listed on SME/growth markets, special purpose acquisition companies, investment funds and real estate investment trusts.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, Bank for International Settlements, Securities Commission of Cambodia, October 2023/April 2024 World Economic Outlook dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

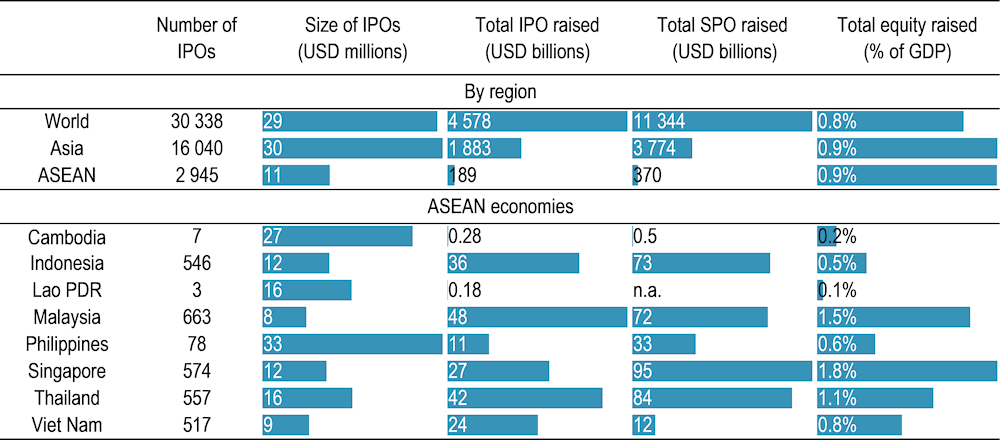

1.5.1. Trends in the use of public equity markets

The use of public equity markets by ASEAN companies has grown over the last two decades. Between 2000 and 2023, the annual average share of the capital raised via public equity offerings to GDP was 0.9% in ASEAN economies in line with the figure for Asia (0.9%) and slightly above the global average of 0.8% (Figure 1.14). Despite smaller initial public offerings (IPOs) in the ASEAN region, since 2000, almost one in every 10 IPOs in the world correspond to an ASEAN company. The total amount of capital raised via secondary public offerings (SPOs) in ASEAN economies almost double that of initial offerings.

The use of public equity market shows significant differences across ASEAN economies over the 2000-23 period (Figure 1.14). The most active markets over the last two decades were Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, where the total capital raised represented between 1.1-1.8% as share of GDP. Viet Nam, Philippines and Indonesia show lower levels of capital raised. Conversely, Cambodia and Lao PDR exhibited a more limited use of public equity financing, with total equity capital raised representing less than 0.2% of their respective GDP.

In the Philippines, Lao PDR and Cambodia the IPO activity is led by fewer and larger companies. Notably, Malaysia stands out as the jurisdiction with the highest overall IPO activity between 2000 and 2023 in terms of both the number of IPOs and total proceeds raised. With respect to secondary equity offerings, Singapore ranks first in the region with USD 95 billion raised (Figure 1.14).

The median size of IPOs in the majority of ASEAN economies remains small compared to Asia ranging between USD 8 billion and USD 33 billion. While Malaysia has the smallest IPOs among ASEAN peers, Philippines recorded the largest ones, mainly as a result of fewer but larger IPOs.

Figure 1.14. Equity capital raised by non-financial companies, 2000-23

Notes: The size of IPOs is calculated by taking the median value of IPOs. The GDP values used in the calculations correspond to forecast values for 2023. Total equity raised as share of GDP is the annual average of the ratio between 2000 and 2023.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, October 2023 World Economic Outlook dataset, see Annex for details.

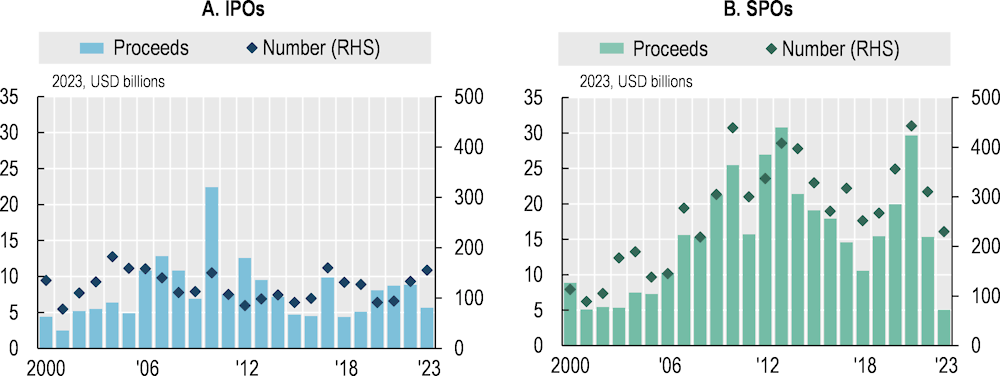

Over time, the trends in the amount of equity capital raised via initial and secondary public offerings, and the number of accessing equity markets have changed. From 2000 to 2010, the capital raised by ASEAN corporations joining public equity markets showed an upward trend with an annual average of USD 8.4 billion, reaching its peak in 2010 at USD 22 billion. In the following years, there was a decline in the IPO activity with an annual amount raised between 2011 and 2019 averaging USD 7.3 billion. Since Between 2020 and 2022, the annual capital raised by non-financial companies stood at around USD 8.5 billion. However, in 2023, the equity raised through IPOs decreased to USD 5.7 billion. The number of IPOs has declined since 2010, from 1 575 IPOs between 2000 and 2011 to 1 370 IPOs between 2012 and 2023 (Figure 1.15, Panel A).

Following global trends, the amount raised through secondary public offerings (SPOs) in the ASEAN region exceeded that of IPOs. However, between 2013 and 2018, the amount of capital raised via secondary offerings followed a downward trend. On average, since 2012, 326 companies issued USD 18.9 billion in new equity annually. These figures indicate a 58% increase in average proceeds and a 57% rise in the number of companies compared to the preceding period (from 2000 to 2011). The secondary public offerings activity increased particularly during the crisis, when non-financial companies extensively use the equity market to raise funds. Indeed, in 2021, amid the notable challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, 443 already listed companies from the ASEAN region collectively raised USD 30 billion (Figure 1.15, Panel B). Nonetheless, in the subsequent years, both the number and amount raised via SPO declined substantially. In 2023 the equity capital raised in the ASEAN region only totalled USD 5 billion.

Figure 1.15. Initial and secondary public equity offerings by non-financial ASEAN companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset; see Annex for details.

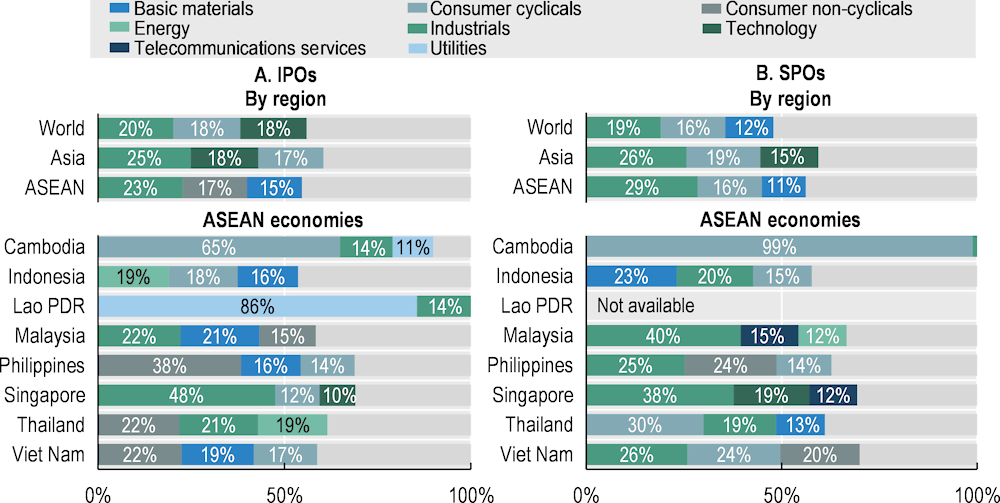

In terms of the industry breakdown of equity public offerings, industrials emerge as the most active industry for both IPOs and SPOs globally, as well as in Asia and in the ASEAN region (Figure 1.16). Globally consumer cyclicals ranks second, while in Asia and the ASEAN region technology and consumer non‑cyclicals rank second, respectively. Technology companies, despite using equity markets to access financing in Asia and globally, they are not important users of public equity in ASEAN economies. This coincides with the low investment in R&D observed by listed companies in the region (Figure 1.11).

Figure 1.16. IPO and SPO proceeds of non-financial companies by industry, 2000-23

Note: This figure shows only the top three industries among non-financial listed companies by share of proceeds.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, see Annex for details.

The most active industries in raising public equity vary across ASEAN economies. In terms of funds raised through IPOs, industrials is the leading industry in Singapore and Malaysia, representing 48% and 22% of the total, respectively. In the Philippines, Viet Nam and Thailand, the consumer non-cyclicals industry stands out as the most active, representing 38%, 22.4% and 21.8% of the equity raised, respectively. On the other hand, Cambodia and Lao PDR, due to the limited use of capital markets, exhibit a less diverse industry composition. For example, in Cambodia, consumer cyclicals companies concentrate 65% of the equity raised while in Lao PDR the utilities industry constitutes 86% 7 (Figure 1.16, Panel A).

Regarding SPOs, the industrials sector dominates in the majority of ASEAN markets. However, in Malaysia and Singapore, this industry’s importance is notably high at 40% and 38%, respectively. In Thailand, the consumer cyclicals industry takes the lead, constituting 30% of the total equity capital raised through SPO, while in Indonesia, 23% or the capital was raised by companies in the basic materials industry. Cambodia's SPO issuance mostly corresponds to consumer cyclicals companies, while Lao PDR did not recorded SPO over the analysed period (Figure 1.16, Panel B).

1.5.2. Trends in the use of corporate bonds

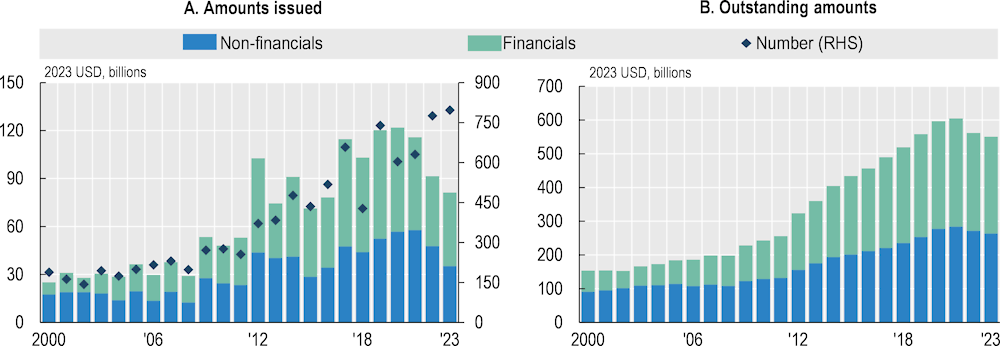

Over the last two decades, the use of corporate bonds by ASEAN companies have steadily grown both by non-financial and financial companies. Capital raised through corporate bonds reached USD 122 billion in 2020, before declining to USD 81 billion in 2023. Over the period 2000-23, issuance by non-financial companies represented 47% of the total. In line with increasing issuance, the amount of outstanding corporate bonds in the region reached USD 551 billion in 2023 and non-financial companies represented 48% of the total.

However, despite the observed growth, the outstanding amount of non-financial corporate bonds represented only 7% of the region’s GDP, below the 12% observed in Asia and 15% globally. Moreover, the capital raised via corporate bonds by ASEAN non-financial corporations during the last decade only accounted for 5% of the total capital raised in Asia, much lower than the ASEAN contribution to Asian GDP (11%) over the same period.8

Capital raised through corporate bonds by ASEAN non-financial companies increased from an annual average of USD 19 billion during 2000-11 to USD 44.1 billion in 2012-23 (Figure 1.17, Panel A). During the latter period, more than 3 000 non-financial ASEAN companies accessed market financing by issuing corporate bonds. They raised a record high of USD 57.8 billion in 2021, largely driven by increased borrowing needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, 2022 and 2023 saw a decline in the use of corporate bonds in line with global trends as a response to tightening monetary policy. The overall growth in the use of corporate bonds by non-financial companies is also reflected in the growing outstanding amounts in the region reaching its peak in 2021 at USD 284 billion (Figure 1.17, Panel B).

Figure 1.17. Corporate bond trends in ASEAN economies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

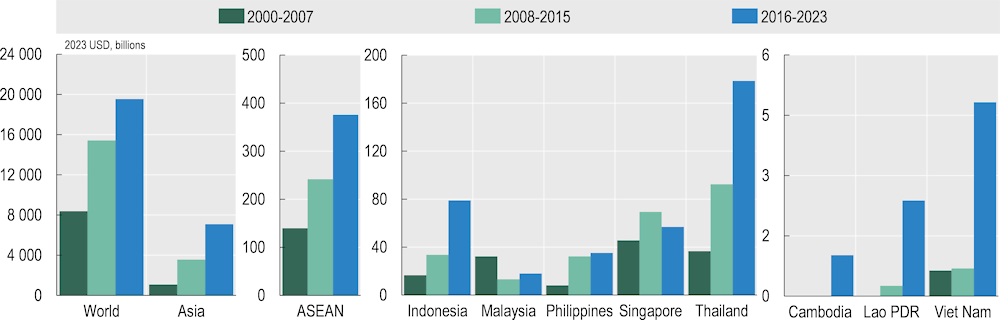

The use of corporate bond markets by non-financial companies shows significant differences across ASEAN economies (Figure 1.18.). Companies from Thailand, Indonesia and Philippines increased their use of corporate bonds over time, in line with global and regional trends. However, Malaysia experienced a decline in corporate bond issuance from USD 32.2 billion during the 2000-07 period to USD 18 billion in the 2016-23 period. Additionally, Singapore also experienced a decrease in issuance over the last seven years. While the use of corporate bonds in Cambodia, Lao PDR and Viet Nam have in improved over time, it is important to note that these markets remain small and are still at an early stage of development.

Figure 1.18. Corporate bond issuances by non-financial companies in ASEAN economies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

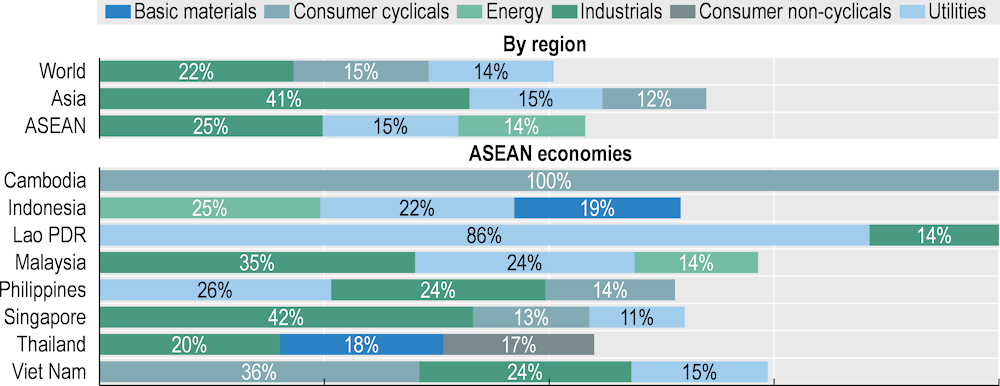

Similar to the use of equity markets, industrial companies dominate the corporate bond issuance globally, as well as in Asia and in the ASEAN region (Figure 1.19). Utilities followed in the ASEAN region. Energy companies are also important issuers of corporate bonds occupying the third place in ASEAN markets, while consumer cyclicals represent a larger share of the issuance globally and in Asia.

Figure 1.19. Industry distribution of non-financial corporate bonds, 2000-23

Note: The figure only shows the top three non-financial industries of corporate bond issuers.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

The most active industries using corporate bonds differ at the country level (Figure 1.19). Similar to ASEAN trends, industrial companies are the largest bond issuers in Singapore (42%), Malaysia (35%) and Thailand (20%) accounting for a significant share of the total capital raised over the last two decades. Utility companies rank within the top three in Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Viet Nam contributing to the regional dominance of that industry. Energy companies account for 14% of ASEAN corporate bond issuance while they are responsible for 25% in Indonesia and 14% in Malaysia. Notably, in Cambodia, all corporate bonds were issued by companies from the consumer cyclical industry, which also represents a significant share (36%) of the issuance of corporate bonds in Viet Nam.

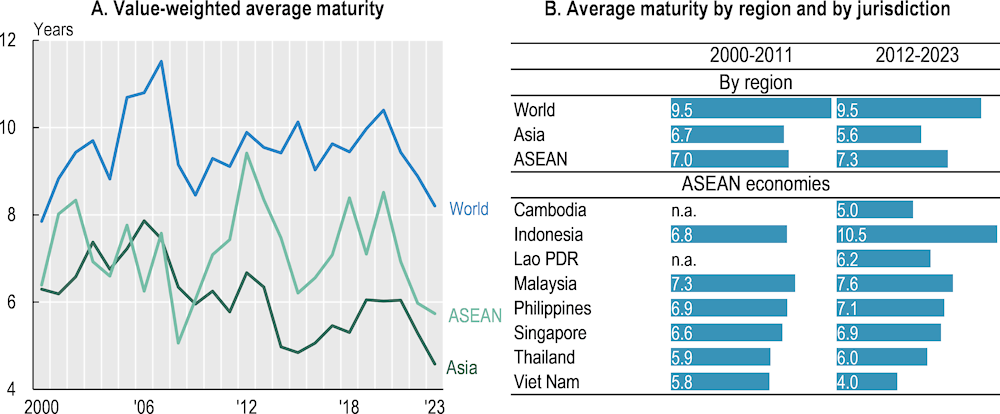

The maturity of corporate bonds has fluctuated over time showing an overall decreasing trend in Asia and in ASEAN economies while it has remained at around the same level globally (Figure 1.20, Panel A). During the past three years there have been a substantial decline in the maturity of corporate bonds across regions. Tighter financing conditions and investors’ concerns about economic prospects are behind the decline observed decline in maturities. Notably, average maturity in ASEAN economies dropped from 8.5 years in 2020 to 5.7 years in 2023.

When analysing average corporate bond maturities between the 2000-11 and 2012‑23 periods, the picture changes for ASEAN economies. Globally, the average maturity of non-financial corporate bonds was 9.5 years, and in the ASEAN region it went up from 7 to 7.3 years (Figure 1.20, Panel B). The exception has been Asia where maturities dropped, driven by the high volume of short-term Chinese corporate bonds.

At the country level, most ASEAN issuers have lengthened the tenor of their corporate bonds, except those from Malaysia and Viet Nam. However, the average maturity of corporate bond issuances for Cambodia and Lao PDR should be interpreted with cautious since in these two young markets there are few issuances.

Figure 1.20. Value-weighted average maturity of non-financial corporate bonds

Note: Maturity used in the figure and in the analysis refers to maturity of the corporate bonds at issuance.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

1.6. Selected issues in the public equity and corporate bond markets

This section discusses selected issues related to the public equity and corporate bond markets that may deserve the attention of policy makers such as: secondary stock market liquidity, index inclusion of ASEAN companies, credit and quality assessment in the corporate bond markets, and barriers to the development of corporate bond markets. It also discusses the listing requirements and fees in the public equity and corporate bond markets.

1.6.1. Secondary stock market liquidity

A liquid market ensures an efficient price formation process, improves investor confidence and contributes to the overall functioning of capital markets. Overall, lack of liquidity undermines the attractiveness of capital markets for certain investors and discourages companies to use marketplaces in the first place. To have meaningful trading in the secondary market, a certain size of activity in the primary markets is essential. Moreover, capital markets’ liquidity is linked to various factors, including the functioning of stock exchanges, the investors base, derivative markets, as well as the engagement of market makers, among others. The affordability and the existence of research on companies, the accessibility of trading information, cost of trading and fiscal arrangements could also have implications on the liquidity levels.

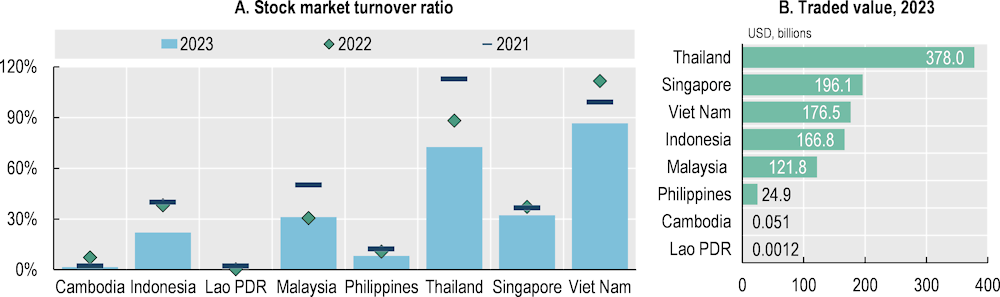

Most public equity markets in ASEAN economies are characterised by low levels of liquidity. The fact that ASEAN markets remain small and underrepresented in investable indices (see Section 1.6.2) does not help attracting foreign investors. In addition, the national investor bases are not broad enough. In 2023 stock market liquidity, measured by the turnover ratio, decreased even further in all the jurisdictions (Figure 1.21, Panel A). Stock markets in the Philippines, Cambodia and Lao PDR offer negligible liquidity (Panel B). In the Philippines, turnover ratio was 8% in 2023, lower than the levels recorded in previous years. Cambodia witnessed a slight increase in the turnover ratio in 2022, reaching 7.3%. However, in 2023 it decreased to 1.6%. Lao PDR has exhibited the lowest stock market liquidity among ASEAN economies over the last three years, with 2023 marking the lowest level at 0.18%. Equity markets in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia showed comparatively higher levels of liquidity with turnover ratios 32%, 31% and 22% respectively in 2023.

Equity markets in Thailand and Viet Nam show relatively higher liquidity. In particular, Thailand’s turnover ratio was 73% in 2023, although it decreased compared to the previous years. Viet Nam’s public equity market, despite being one of the smallest in the region, showed the highest level of liquidity in 2023 among ASEAN markets. However, liquidity significantly decreased in Viet Nam when compared to that in 2022.

Figure 1.21. Liquidity in the public equity market in ASEAN economies

Notes: The data used in the figures was retrieved from the respective stock exchange websites. The turnover ratio is calculated as the total value traded in a given year divided by the market capitalisation at the end of that year. For Lao PDR, the turnover ratios for 2021 and 2022 were directly extracted from the figures disclosed by the Lao Securities Exchange.

Source: Bursa Malaysia, Cambodia Securities Exchange, Lao Securities Exchange, The Philippine Stock Exchange, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, Indonesia Stock Exchange, Hanoi Stock Exchange, HCM Stock Exchange, The Stock Exchange of Thailand, World Federation of Exchanges.

1.6.2. Index inclusion of companies from ASEAN region

In recent years, institutional investors have widely adopted the use of investable indices in their asset allocation process, primarily due to the benefits of index investing such as portfolio diversification and lower management fees. Most indices adopt a market capitalisation-weighted approach when assigning index weights to companies, leading to an inherent bias towards larger companies. Moreover, in the selection of markets to be included in the indices, certain liquidity requirements have to be met. Therefore, investors’ portfolios mirroring these indices are often heavily concentrated in markets with certain level of liquidity and in fewer and larger corporations, leaving smaller companies and less liquid markets out of the radar of institutional investors.

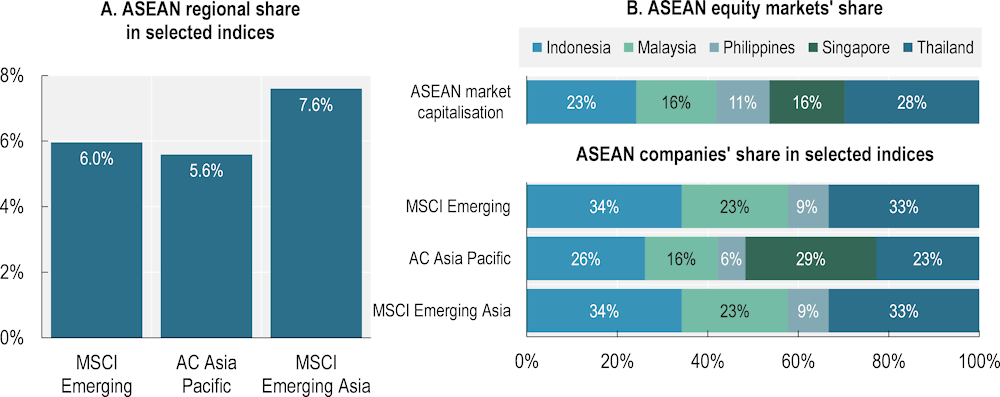

An increasing number of ASEAN corporations have been included into major investable indices. Index inclusion improves the visibility of companies and markets, thus attracting more foreign investors, in particular institutional investors. However, there are notable differences in the inclusion of ASEAN companies in different indices.

In terms of regional representation, ASEAN companies are underrepresented in the MSCI Emerging Market index. The index allocates a weight of only 6% to ASAEN companies, lower than the ASEAN economies’ share in the GDP of emerging markets and developing economies (8.4%) (Figure 1.22, Panel A). Moreover, companies from only five ASEAN economies are included in global and regional indices. (Panel B). Notably, companies from Cambodia, Lao PDR and Viet Nam are currently not included in any of the indices shown here. Additionally, compared to their share in total ASEAN market capitalisation, companies from Thailand are underrepresented in the AC Asia Pacific index, while companies from the Philippines are underrepresented in the MSCI Emerging, AC Asia Pacific and MSCI Emerging Asia indices when compared to their market capitalisation share in the ASEAN region.

Figure 1.22. Share of ASEAN companies in major global and Asian indices, end of 2022

Note: The information on MSCI constituents is as of September 2023, REITS and investment funds are excluded from the indices.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, MSCI, see Annex for details.

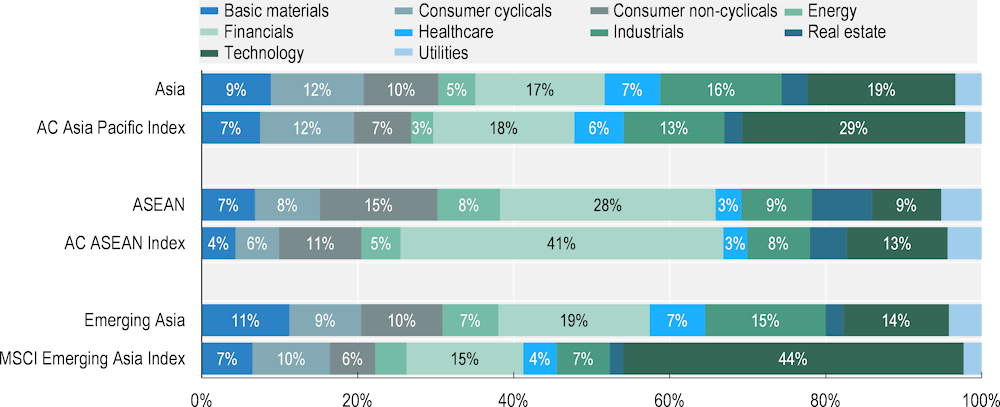

Major Asian and ASEAN indices do not fully reflect the industry composition of the markets they track (Figure 1.23). While in Asia, the indices feature a higher proportion of companies from the technology sector, the index including ASEAN companies has a predominant presence of companies from the financial sector. Major Asian indices, such as the AC Asia Pacific Index and the MSCI Emerging Asia overweight the technology sector. In contrast, the AC ASEAN index is heavily weighted towards the financial sector, constituting 41% of the market capitalisation covered by the index, a significantly higher share than the financial sector's share in ASEAN markets as well as that of other indices.

Figure 1.23. Industry composition of major global, Asian and ASEAN indices, end of 2022

Notes: The information on MSCI constituents is as of September 2023, REITS and investment funds are excluded from the indices. Apart from the industry composition of major indices, the figure also shows the actual industry composition for the listed companies in Asia, ASEAN and Emerging Asia.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, MSCI, see Annex for details.

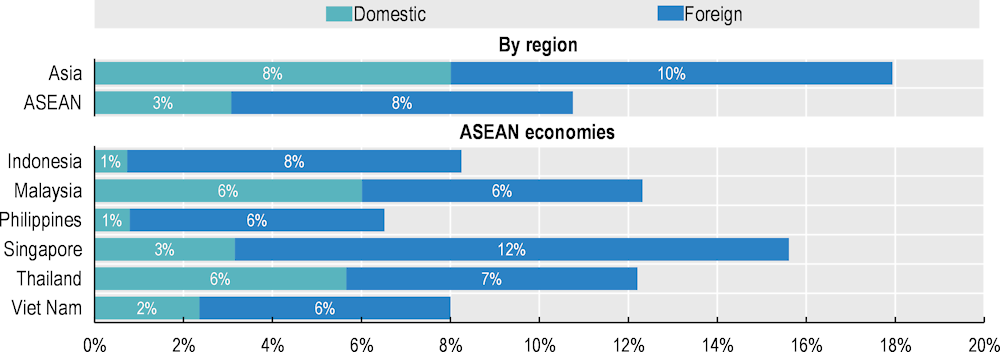

The lack of inclusion of ASEAN companies in investable indices is also visible in the participation of foreign institutional investors in ASEAN markets (Figure 1.24). While 10% of the Asian listed equity in 2023 was in the hands of foreign institutional investors, this number is only 8% in ASEAN markets. Moreover, there are significant differences in foreign ownership across ASEAN markets. Singapore stands out with foreign institutional investors holding 12% of the listed equity. This does not come as surprise since Singapore is the only ASEAN markets included in the MSCI World Index (covering developed markets) and also represents a high share of the AC Asia Pacific index (see Figure 1.22). Markets such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand are also represented in investable indices and show a significant share of foreign institutional ownership.

Figure 1.24. Institutional investor ownership in ASEAN markets, end of 2023

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, LSEG, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

1.6.3. Credit assessment and quality in the corporate bond markets

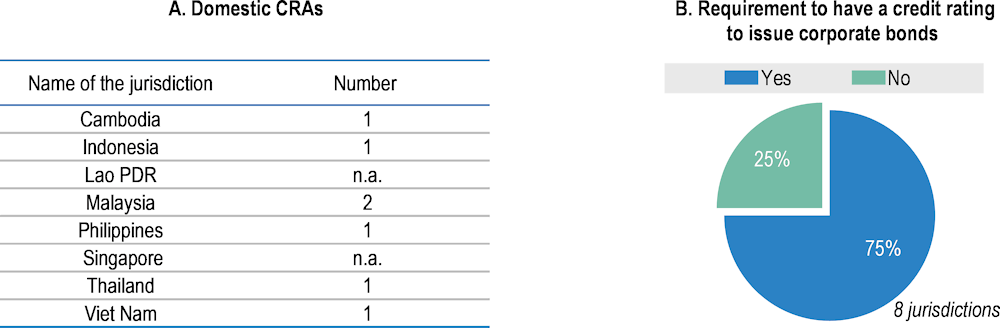

Easy and affordable access to credit ratings and familiarity with the rating process significantly increases companies’ ability to use long-term debt securities. Assessment of the creditworthiness of companies is perceived as the second most significant barrier to the development of corporate bond markets in the ASEAN region (OECD, 2024[1]). Despite the expansion of corporate bond markets globally over the last two decades, credit quality has deteriorated. The same has been observed in Asia and in ASEAN economies. This has been mainly the result of the surge in lower-grade corporate bonds.

All ASEAN markets have registered at least one or several credit rating agencies (CRAs). Domestic CRAs operate in the majority of them, while international and regional CRAs operate only in a few. Recent OECD research shows that all ASEAN markets, except Singapore and Lao PDR, have at least one registered domestic CRA (Figure 1.25, Panel A). Differently, one regional CRA operates in Lao PDR and one international CRA in Singapore. International CRAs also operate in Thailand and Viet Nam, and Thailand also hosts a regional CRA. In Malaysia, international CRAs have a stake in the domestic ones.

Obtaining a credit rating from a CRA for a corporate bond typically demands technical expertise to understand and navigate the involved processes, which smaller companies may lack. Additionally, considering the costs associated, it can also be unaffordable for smaller issuers to obtain a credit rating which may ultimately impede access to corporate bond financing. To address this issue and support market-based financing for growth companies, Malaysia introduced an alternative credit system where SME Corporation of Malaysia provides rating services.

The rating scales and process could vary across markets, posing challenges in objectivity, transparency and the quality of the analysis regionally. In order to improve rating quality through mutual cooperation Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam joined to the Association of Credit Rating Agencies in Asia (ACRAA).

Figure 1.25. Number of domestic CRAs and requirements to have a credit rating

Notes: Lao PDR recognises a regional CRA, while Singapore an international CRA. The number of domestic Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) in Panel A is based on the information about ACRAA (Association of Credit Rating Agencies in Asia) membership. For Cambodia the information was collected from the Securities and Exchange Regulator of Cambodia.

Source: OECD (2024[1]), Corporate Bond Markets in Asia: Challenges and Opportunities for Growth Companies, https://doi.org/10.1787/96192f4a-en; Japan Credit Rating Agency, (2023[2]), Association of Credit Rating Agencies in Asia (ACRAA), https://www.jcr.co.jp/en/service/international/acraa/; Securities and Exchange regulator Cambodia (2024[3]), Credit Rating Agency, https://www.serc.gov.kh/english/m69.php?pn=6.

Credit ratings also play an increasingly important role by influencing the investment decisions and asset allocation of financial and non-financial institutions in different ways such as quantitative limits by regulation, self-defined investment policies, rating-based indexes and investment mandates. All ASEAN markets, but Singapore and Viet Nam, require corporate bonds to be rated and have a minimum credit rating (Figure 1.25, Panel B). For example, companies wanting to list their bonds on the Lao’s Exchange need to obtain a minimum “BB” credit rating. Even though Singapore does not set out any rules regarding the credit rating level of issued corporate bonds, the exchange requires them to be investment grade. Indonesia requires in its legal framework that corporate bonds require at least an investment grade rating.

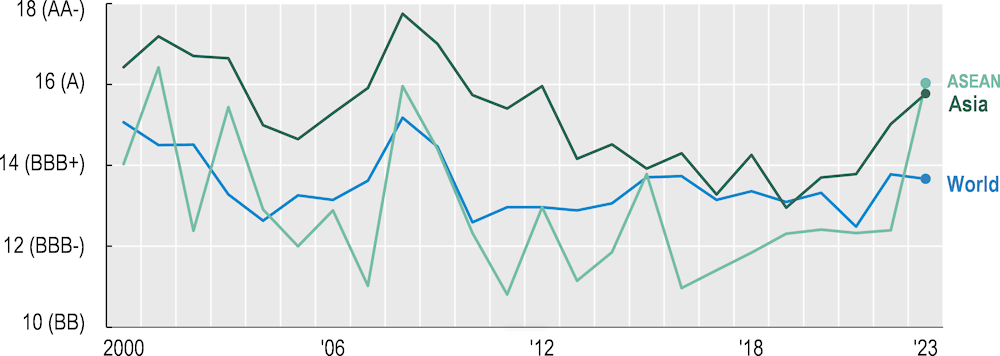

The aggregate credit quality of non-financial corporate bonds has seen a decline over time globally, as well as in Asia and in the ASEAN region. The OECD corporate bond credit quality index,9 shows this decrease in the credit quality of newly issued corporate bonds (Figure 1.26). In 2022, the average rating of corporate bonds issued by ASEAN companies was slightly higher than the investment grade threshold “BBB-”. Importantly, over the period 2000-22, the quality of bonds issued by ASEAN companies has been mostly lower than in Asia. In 2023, corporate bonds issuance in Asia and ASEAN experienced a decline and therefore restricting access for lower-rated companies. Consequently, only highly rated companies were able to issue corporate bonds in 2023. As a result, the corporate bond credit quality index significantly improved in Asia and in the ASEAN region. On average, in 2023 corporate bonds issued in these regions carried an average "A" rating.

Figure 1.26. Corporate bond credit quality index

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

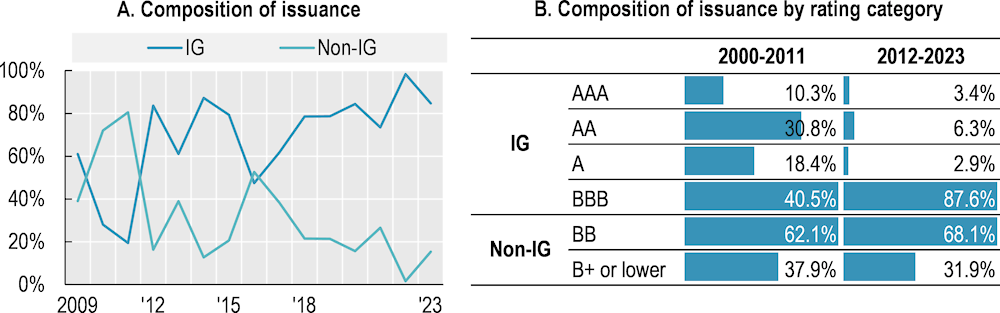

A closer look at issuer credit rating composition shows that the decrease in credit quality is partly an effect of increasing issuances in BBB rated bonds and an expansion of the non-investment grade market. Figure 1.27 in Panel A provides a breakdown of corporate bond issuance among ASEAN non-financial companies over the 2009-22 period. In general, the issuance of investment grade (IG) bonds dominated that of non‑investment grade (non-IG) bonds.

A breakdown of corporate bond credit quality in Panel B shows a significant surge in lower-rated bonds. Within the investment grade category, BBB rated bonds’ share in issuance increased from 40.5% during the 2000-11 period to 87.6% in the 2012-23 period. This is the opposite for non-investment grade bonds, where the share of the bonds with the highest rating (BB) increased from 62.1% to 68.1%.

Figure 1.27. Credit quality of non-financial corporate bonds in ASEAN economies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

1.6.4. Barriers to the development of corporate bond markets

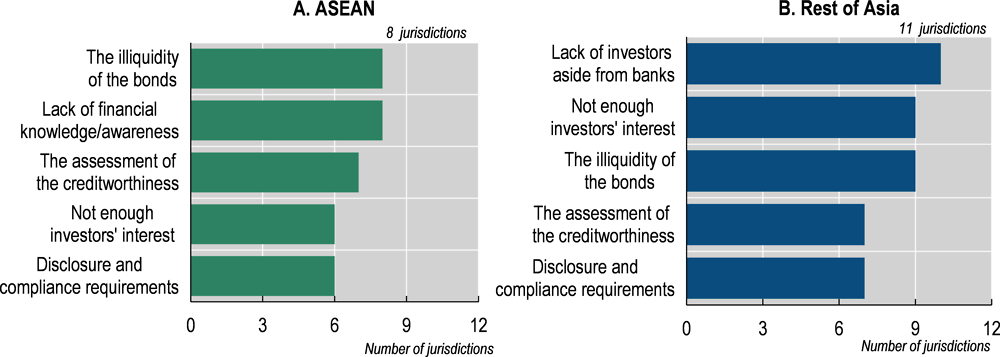

Despite the observed growth in ASEAN corporate bond markets, companies still have limited access to these markets. Some of the potential barriers to the further development of corporate bond markets include: weak regulatory frameworks (i.e. tax treatment and bankruptcy laws), lack of market infrastructure and the presence of intermediaries, a small and unsustainable investor base, high costs and complexity of issuance of bonds compared to bank credit, legal and investor protection issues, corporate governance issues, undeveloped government bond markets, a small number of mature firms and weak disclosure standards (IOSCO, 2015[4]).

Figure 1.28. Barriers to the development of bond markets in ASEAN and Asia

Notes: The figure shows the number of countries that identified the different factors as a barrier to the development of a corporate bond market. Panel B includes: Australia, Bangladesh, People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong (China), India, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Chinese Taipei.

Source: OECD (2024[1]), Corporate Bond Markets in Asia: Challenges and Opportunities for Growth Companies, https://doi.org/10.1787/96192f4a-en/

According to recent OECD research one of the most important barriers to the development of corporate bond markets in ASEAN economies is the lack of market liquidity (Figure 1.28, Panel A). Importantly, this has been pointed out as more significant barrier in ASEAN economies compared to the rest of Asia, where lack of liquidity ranks second (Figure 1.28, Panel B). Available data on trading volumes for corporate bonds shows that the corporate bond market in Indonesia has the highest turnover ratio10 in 2022, while Thailand and Malaysia have comparatively low levels of liquidity at 27% and 11.4%, respectively (OECD, 2024[1]).

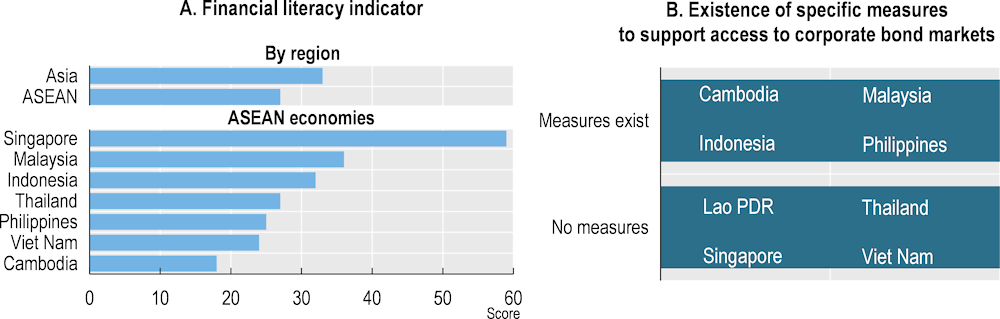

Lack of financial knowledge and awareness was identified as other significant barrier by all ASEAN regulators. The issue is more relevant for ASEAN economies than for the rest of Asia, where this was not cited among the top five perceived barriers. Lack of financial knowledge could undermine investors’ ability to assess the benefits and risks of corporate bond investments, which in turn could limit their participation in this market. The level of investors’ financial literacy in the majority of ASEAN economies is lower than in Asia. The median value of the share of adults that are financially literate in ASEAN economies was 27%, six percentage point lower than in Asia (33%). Among ASEAN economies, only Singapore and Malaysia show higher values than in Asia (Figure 1.29, Panel A).

The lack of interest from investors and the assessment of creditworthiness, were identified within the five most important impediment for issuing corporate bonds both in ASEAN and in the rest of Asia (Figure 1.28). These two issues are interrelated and tend to self-reinforce each other, as challenges in evaluating credit worthiness undermine the investors’ ability to evaluate risks and willingness to invest.

Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines have in place at least one measure in place aiming to promote access to corporate bond markets (Figure 1.29, Panel B).

Figure 1.29. Financial literacy and measures to support access to corporate bond markets

Notes: Panel A shows the share of adults who were financially literate in 2014. Data are not available for India and Lao PDR. In the S&P Global FinLit Survey, the literacy questions measure the four fundamental concepts for financial decision-making that include basic numeracy, interest compounding, inflation and risk diversification. The median values are shown for Asia and for the ASEAN region.

Source: OECD (2024[1]), Corporate Bond Markets in Asia: Challenges and Opportunities for Growth Companies, https://doi.org/10.1787/96192f4a-en, Klapper, Lusardi and Van Oudheusden (2014[5]), Financial Literacy Around the World: Insights from the S&P Ratings services global financial literacy survey, https://gflec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/3313-Finlit_Report_FINAL-5.11.16.pdf.

1.7. Policy considerations

The growth of market-based financing in ASEAN economies is a reason for optimism. However, the fact that corporations in the region continue heavily relying on bank financing provides enough ground for further improvements in the functioning of capital markets in the region to allow companies to diversify their funding sources while increasing corporate sustainability. The fact that investment in the region is mostly concentrated on fixed capital, and little is invested in research and development, raises questions if corporations are provided with the appropriate financing sources. The need of well-functioning capital markets able to channel enough resources to enable the green and digital transitions in the region should be at the top of the policy agenda. With this in mind, the following policy considerations should be explored by policy makers in ASEAN economies:

Continue developing market-based financing: Local authorities should consider designing policies to encourage the development and use of market‑based financing. Corporations heavily rely on bank-based financing in the majority of ASEAN economies (e.g. Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam) and market-based sources play a secondary role. While Indonesia and Philippines show a higher dependence on market-based financing, the penetration of both bank- and market-based financing remains low suggesting that the existence of many financially constraint businesses.

Promote the listing of non-financial corporations: Financial companies represent 28% of the market capitalisation in ASEAN markets, almost twice the figure in Asia and globally. Most of these companies are banks that raise financing from public markets to later intermediate credit to the real sector. Indeed, the banking sector in ASEAN economies has a prominent position as provider of financing to the corporate sector.

Inclusion of companies in investable indices: The lack of inclusion of ASEAN companies in investable indices has a visible impact on the participation of foreign institutional investors in ASEAN markets. While 10% of the listed equity is owned by foreign institutional investors in Asia, this number is 8% in ASEAN markets. Moreover, there are significant differences in foreign ownership across ASEAN markets. The fact that indices usually select markets with a certain level of liquidity and within those markets they adjust market capitalisation by free-float ratios, raises the need for ASEAN markets to increase the size of their local markets by bringing more and larger companies, but also by encouraging already listed companies to increase their free-float levels through increased new equity issuance or reduced shares in the hands of controlling shareholders.

Promote the access to long-term financing via corporate bonds: Corporate bonds have increasingly become a source of long-term financing for non-financial companies. Despite the observed growth of this market in ASEAN economies, the capital raised by ASEAN corporations during the last decade only accounted for 5% of the total capital raised in Asia, much lower than the ASEAN contribution to Asian GDP (11%). Overall, more than half of the capital raised in the ASEAN region is issued by financial companies and in some markets financial companies are the largest users of corporate bonds. Importantly, corporate bond markets in the region are at differences stages of development which should require the implementation of different set of policies to continue developing each market (for a full set of recommendations to develop see (OECD, 2024[1])). One of the main barriers to access bond markets is easy and affordable access to get a credit rating.

Enhancing secondary market liquidity and broadening the investor base: Secondary market liquidity plays a pivotal role in facilitating an efficient price discovery mechanism, bolstering investor confidence, and fostering the overall functioning of capital markets. The lack of liquidity reduces the appeal of capital markets for certain investors and dissuades companies from using public markets. Across ASEAN economies, most public equity markets grapple with low liquidity levels. Similarly, the inadequate liquidity in corporate bond markets within ASEAN nations remains a concern. Low liquidity levels have been identified as a key impediment to corporate bond market development. Today, institutional investors’ participation in ASEAN equity markets remains low compared to Asia and globally. In many markets around the globe, the involvement of domestic institutional investors has played a pivotal role in nurturing local capital markets. Therefore, further developing domestic institutional investors and allowing them to participate in local capital markets should be a priority in the region.

Foster investment and boost productivity: The ability to generate sales of ASEAN corporations has been on a declining trend since 2011, despite the continued growth of listed companies’ assets. This is a sign of a reduced capacity of corporations in the region to generate better products or to use more efficient and better technologies in their production processes to enhance margins. One important factor is investment. ASEAN corporations despite showing similar levels of investment in physical capital (capex) to those observed in Asia and globally, they underinvest in research and development. Investment in R&D is a key driver of economic growth and enhances the competitiveness of economies and corporations in the global market. It fuels the development of new industries, improves productivity and creates high-quality jobs. However, the success of R&D investment is highly uncertain and, therefore, well-functioning capital markets, in particular equity markets, play a key role in allowing corporations to invest in R&D enabling economies to exploit the benefits of innovation in terms of productivity and growth.

Foster innovation and digital transformation: Better access to market-based financing could support the development of innovative ventures and at the same time, digital technologies could be used to ease access to financing. Contrary to what it is observed in Asia, technology companies are not important users of public equity capital. Companies from industrials, consumer cyclical and consumer non-cyclicals are instead the most important users of public equity. Policy makers in the region should consider taking actions to draw the benefits from the new opportunities presented by digital technologies and to explore the potential capacities in the region.

References

[4] IOSCO (2015), Corporate Bond Markets: An Emerging Markets Perspective, Staff Working Paper of the IOSCO Research Department, https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD510.pdf.

[2] Japan Credit Rating Agency, L. (2023), Association of Credit Rating Agencies in Asia (ACRAA), https://www.jcr.co.jp/en/service/international/acraa/.

[5] Klapper, L., A. Lusardi and P. Van Oudheusden (2014), Financial Literacy Around the World: Insights from the S&P Ratings services global financial literacy survey, Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, https://gflec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/3313-Finlit_Report_FINAL-5.11.16.pdf.

[1] OECD (2024), Corporate bond markets in Asia: Challenges and Opportunities for Growth Companies, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/96192f4a-en.

[3] Securities and Exchange Regulator of Cambodia (2024), Credit Rating Agency, https://www.serc.gov.kh/english/m69.php?pn=6.

Notes

← 1. In Indonesia the first stock exchange was put in place by the Dutch East Indies government as a branch of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, while in the Philippines the Manila Stock Exchange was merged with the Market Stock Exchange to form the Philippine Stock Exchange.

← 2. The Cambodia Securities Exchange, the national stock exchange, is 55% owned by the Ministry of Economy and Finance; and Lao’s stock exchange (Lao Securities Exchange) is 51% owned by the Bank of Lao PDR. The Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) is a fully owned subsidiary of the Stock Exchange of Thailand Group which is a government agency operating under the legal framework laid down in the Securities and Exchange Act. Both the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange and the Hanoi Stock Exchange are 100% state-owned.

← 3. The calculation for Cambodia is based on the maximum threshold of both the main market and the growth market. In the main market, the initial listing fee follows a regressive structure, capped at KHR 10 million for a market capitalisation of KHR 12 billion. Conversely, in the growth market, the maximum fee is KHR 4 million.

← 4. In the Philippines, the annual listing fee in the main market has a minimum of PHP 250 000, whereas this amount represents the maximum annual fee in the SME market.

← 5. Measured by the turnover asset ratio that is defined as sales over assets.

← 6. Bank financing information refers to 2022, the latest available.

← 7. This corresponds to a single IPO occurring in 2011.

← 8. The calculation is based on the IMF World Economic Outlook Database.

← 9. The OECD corporate bond credit quality index is calculated as a weighted average of individual corporate bond credit ratings. Each credit rating is translated into a scale from 1 to 21. The lowest credit rating is assigned a value of 1 and the highest quality rating is assigned a value of 21.

← 10. The corporate bond turnover ratio shows the trading volume relative to the outstanding amount of corporate bonds.