This chapter examines the strategic use of digital technologies and data to transform Portugal's justice system to make it more accessible and people-centred. It applies key components of the OECD Digital Government Policy Framework to the Portuguese context and details Portugal's digital and innovative initiatives. The chapter also highlights challenges and opportunities in advancing digital transformation in the justice sector. It focuses on strengthening existing governance arrangements and institutional capabilities to ensure sustainability and continuity for greater impact.

Modernisation of the Justice Sector in Portugal

8. Digital technologies and data for people-centred Justice in Portugal

Copy link to 8. Digital technologies and data for people-centred Justice in PortugalAbstract

8.1. Leveraging digital governance to modernise justice systems

Copy link to 8.1. Leveraging digital governance to modernise justice systemsDigital transformation is a key priority in ongoing modernisation efforts to make justice systems more accessible and people-centred (OECD, 2024[1]). People and businesses are experiencing conflicts in new ways and becoming more demanding in terms of how their conflicts are solved. Higher expectations of public services from more empowered users in a context of growing internal and external pressures, such as lower levels of trust in public institutions (OECD, 2022[2]), promises of the digital age and economic crises are major drivers that call for change in justice systems. This implies putting people’s needs at the centre of the design and delivery of justice services. Digital technologies and data are important leverages in the process of transforming justice systems.

Digital technologies and data hold significant potential to strengthen access, resilience, efficiency, and effectiveness of justice systems. The COVID-19 pandemic showcased the important role that digital technologies and data can have in helping justice systems quickly react and respond to people’s needs and ensuring justice systems remained accessible. Digital technologies and data may support governments to better understand user needs through data-driven approaches, and help deliver services fit for their needs by reducing the length and complexity of processes. In particular, the use of digital technologies in dispute resolution mechanisms (before and in court) can significantly increase access to and responsiveness of justice systems to legal needs, accompanied by appropriate safeguards not to create additional barriers to accessing justice. Likewise, if managed in a way that puts people at the centre, digital transformation can be a source of empowerment to individuals and communities, allowing them to have access to accurate legal information and make informed decisions about their legal situations.

Understanding that governments should deliver on people’s needs, the OECD Digital Government Policy Framework (DGPF) identifies key determinants for effective design and implementation of strategic approaches to transition towards higher levels of digital maturity across the public sector (see Box 8.1). It underpins the drive to rethink internal processes and operations with a view to connecting different parts of the administration to improve efficiency, effectiveness and user experience (OECD, 2020[3]).

Box 8.1. The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework

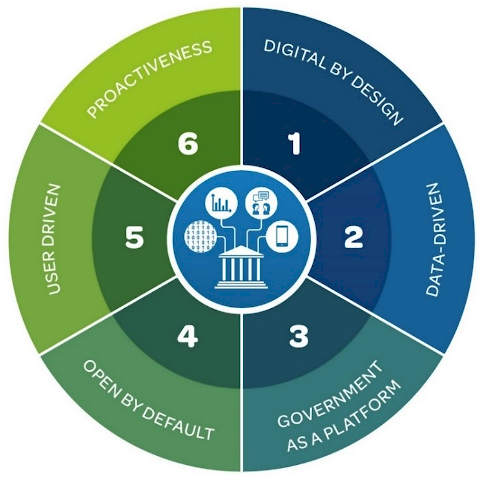

Copy link to Box 8.1. The OECD Digital Government Policy FrameworkThe OECD Digital Government Policy Framework consists of six dimensions that comprise a fully digital government:

Dimension 1 – Digital by design: Measures how digital government policies are designed to enable the public sector to use digital technologies and data in a coherent way when designing policies and services.

Dimension 2 – Data-driven: Measures government’s governance and enablers on access, sharing and reuse of data across the public sector.

Dimension 3 – Government as a platform: Measures the deployment of common building blocks (e.g. guidelines, tools, data, digital identity, software) to equip teams to advance a coherent transformation of government processes and services across the public sector.

Dimension 4 – Open by default: Measures openness beyond the release of open data, including efforts to foster the use of digital technologies and data to communicate and engage actors.

Dimension 5 – User-driven: Measures governments’ capacity to place user needs at the core of the design and delivery of policies and services.

Dimension 6 – Proactiveness: Measures governments’ capacity to anticipate the needs of users and service providers to deliver government services proactively.

Source: OECD (2020[3]), Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a digital government, https://doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en.

The six dimensions of the OECD Digital Government Policy Framework can be applicable to modernisation efforts for people-centred justice systems. For example:

Applying the Digital by design dimension to justice systems involves embedding digital technologies and data from the outset to transform justice policies, services and processes. For instance, governments can leverage digital technologies and data to implement seamless case management systems (including case filing, triage, document management, workflow automation, communicating with parties) for greater efficiency and transparency.

Implementing a Data-driven approach to justice systems entails the capacity of accessing, sharing, and reusing data within justice institutions and the public sector more broadly. A data-driven approach can also help design better justice policies (e.g. crime prevention and recidivism).

Government as a platform encourages the use of common digital infrastructure and tools across the justice system, including databases for legal precedents and legislation, digital identity and document authentication systems.

Adopting an open by default approach in justice systems implies improving transparency and openness in justice. This can include releasing court decisions in available, accessible and reusable formats, developing tools to allow people to listen to public hearings, and using platforms to improve communications and users’ awareness on court cases, legal aid, and their material and procedural rights.

User-driven justice systems essentially place users at the core of designing and delivering justice services. This could include, for instance, using data gathered from monitoring (e.g. certain administrative data collected on an ongoing basis from social security services) and evaluation mechanisms (e.g. satisfaction and legal needs surveys) to improve service delivery to victims of domestic violence, providing support for those who may face barriers to accessing justice services, adopting plain language when communicating with justice users.

Proactiveness emphasises the justice system's ability to anticipate and meet the needs of people and businesses proactively. It aims to create a more responsive and preventative justice system that can address issues efficiently and effectively. Examples include sending automatic notifications about case updates, using data analytics to identify and address potential legal issues before they escalate, and providing preemptive legal assistance or advice through users’ preferred channels.

8.1.1. Contextualising digital transformation in Portugal’s justice system

Copy link to 8.1.1. Contextualising digital transformation in Portugal’s justice systemPortugal has made significant efforts to accelerate digital transformation of its justice system and integrate digital technologies and data to design and deliver people-centred justice. Portugal’s strategic documents (see Towards people-centred justice in Portugal in Chapter 2, and Strategy and plan) to modernise its justice sector echo the national commitment to accelerate innovation and leverage digital technologies and data to improve people’s life, building on previous efforts on administrative simplification.

The most significant example is the Simplex programme, which emphasises a people-centred approach to the design and delivery of public services (see Legal and Justice Needs in Portugal, in Chapter 3). At the whole-of-government level, the commitment to accelerate digital transformation was reinforced with the Strategy for Innovation and Modernisation of the State and the Public Administration 2020–2023 (Government of Portugal, 2020[4]) and of Strategy Portugal 2030 (Government of Portugal, 2020[5]). Specifically for the justice sector, the Strategy for Innovation and Modernisation of the State and Public Administration focused on the need to invest in the people who work in public administration and to deepen the global governance of technologies.

Building on previous initiatives such as the National Initiative for Digital Competences e.2030 – INCoDe.2030 (Government of Portugal, 2018[6]), commitment to the digital transformation was fully embraced in 2020 at the whole-of-government level, with the approval of the cross-sectoral Action Plan for Digital Transition (Government of Portugal, 2020[7]). The action plan seeks to support the implementation of measures aiming at the digital transition of the public sector, companies and citizens (see Box 8.2).

Box 8.2. Portugal: Action Plan for Digital Transition

Copy link to Box 8.2. Portugal: Action Plan for Digital TransitionThe Action Plan for Digital Transition is a strategic document adopted by the Portuguese government to guide the country through a comprehensive digital transformation. This initiative aims to leverage digital technologies to drive economic growth, improve public services, and enhance the quality of life for all citizens.

This strategic document is based on three fundamental pillars:

The first pillar is focused on capacity-building strategies not only for public servants but also on initiatives to equip the Portuguese population with the necessary digital skills for the modern workforce, including training programmes and education initiatives at all levels from basic digital literacy to advanced digital skills.

The second pillar is based on fostering entrepreneurship and investments, supporting both small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as larger companies, to adopt digital technologies to improve competitiveness, innovation, and access to global markets. Support involves financial incentives, technical assistance, and innovation hubs.

The third pillar focuses on digital transformation of the public sector, notably by using digital technologies to make services more efficient, accessible, and user-friendly.

This Action Plan for Digital Transition is a multi-year effort involving collaboration between the government, private sector, academic institutions, and civil society to achieve these ambitious goals. Among the priority areas of the Action Plan, many apply to the modernisation of justice, in particular to the design and delivery of services. With a direct impact on the justice system, the priority measures include:

Digitalisation of the 25 most used public services, aiming at simplification and online access for at least the 25 most used administrative services, ensuring their dematerialisation and that everyone has access to digital public services (sub-pillar III.1 – digital public services);

Increased provision of digital services in different languages of interest for internationalisation, with the aim of ensuring that the services available on the ePortugal.gov portal are multilingual, and that information content and electronic forms are translated into languages other than Portuguese, ideally always in English by default (sub-pillar III.1 – digital public services);

Cloud strategy of the public administration, which provides the creation of the necessary strategic framework for the adoption of cloud tools by the public administration (sub-pillar III.1 – digital public services);

Simplification of public procurement of information and digital technology services by the public administration, which aims to simplify procedures related to the provision of services and acquisition of digital services and goods by the public administration (sub-pillar III.2 – agile and open central administration).

Source: Government of Portugal (2020[7]), Resolution of the Council of Ministers 30/2020, https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/resolucao-conselho-ministros/30-2020-132133788.

The modernisation efforts in Portugal's justice system, particularly through digital transformation initiatives, reflect the priority measures in the Action Plan and have seen varying levels of buy-in within and outside the public sector. High-level leadership has often publicly supported the modernisation of justice in Portugal including through the allocation of budget for modernisation initiatives (Government of Portugal, 2023[8]) (Government of Portugal, 2024[9]) (Sarmento e Castro, 2022[10]).

Portugal stood out with projects that aimed to improve the efficiency of justice and the dissemination of information on available services. Over the last two decades, considerable efforts have been made to provide the justice system with digital infrastructure that enables professionals to work more efficiently and more agilely. These efforts have been registered at different speeds in the various segments of the justice sector, from registry to courts and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms (Government of Portugal, 2024[11]) (Government of Portugal, 2024[12]) (Government of Portugal, 2023[13]). In addition, the active participation of stakeholders in training programmes and innovation initiatives have underscored their buy-in and collaborative modernisation of Portugal's justice system (Government of Portugal, 2024[14]) (Government of Portugal, 2022[15]) (Government of Portugal, 2022[16]).

Despite Portugal’s efforts in modernising its justice system over several decades of reform and noticeable buy-in within and outside the public sector, there is an untapped opportunity to enhance existing governance arrangements, including on ICT infrastructure, sustainability of strategic plans over time, institutional and individual capabilities and data governance to transform the justice system and services, and meet new demands on the justice sector from people and businesses.

8.2. Governance to steer the strategic use of digital technologies and data

Copy link to 8.2. Governance to steer the strategic use of digital technologies and dataThe complexity of digital transformation requires robust governance to drive change across the public sector. Such governance enables governments to envision and lead coherent and sustainable digital transformation across the public sector, establishing a collaborative and inclusive digital ecosystem. Grounded in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[17]), the E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government presents the OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government (see Box 8.3). It helps governments to seize the benefits, and manage and address the challenges of digitalisation through sound governance approaches (OECD, 2021[18]).

Box 8.3. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government

Copy link to Box 8.3. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government

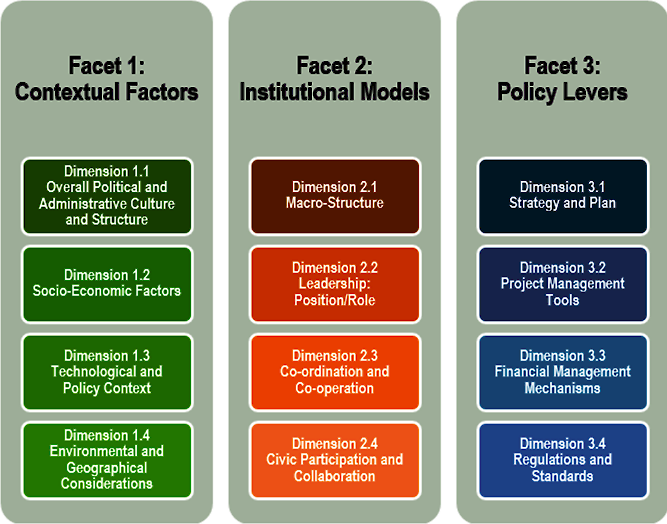

The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government presents three governance facets:

Contextual Factors: Define country-specific characteristics to be considered when designing policies to ensure a human-centred, inclusive and sustainable digital transformation of the public sector.

Institutional Models: Present different institutional set-ups, approaches, arrangements and mechanisms within the public sector and digital ecosystem, which direct the design and implementation of digital government policies in a sustainable manner.

Policy Levers: Support governments to ensure a sound and coherent digital transformation of the public sector.

Source: OECD (2021[18]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

The framework provides guiding policy questions, drawn from the insights, knowledge and best practices of OECD member and non-member countries. While initially conceived to support strengthening the governance of digital government towards a mature, digitally-enabled state, the framework’s dimensions can be applicable to modernisation efforts for people-centred justice systems. The next sections apply some of the relevant dimensions of the framework to help assess the state of play and identify areas for improvement in Portugal’s justice system.

8.2.1. Contextual factors: Technological and policy context

Copy link to 8.2.1. Contextual factors: Technological and policy contextContextual Factors refers to country-specific characteristics that should be considered according to the political, administrative, socio-economic, technological, policy and geographical context. Although each country has its contextual specificities that warrant a unique governance framework, the application of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[17]) can help to identify common elements of governance that are relevant for all countries.

The Technological and Policy Context dimension covers key contextual factors that are linked to the country’s past, current and prospective technological development and how technology is used in the public and private sector, which have fundamental influence over the digital governance in the public sector (OECD, 2021[18]). Fact-finding interviews and desk research helped identify two important bottlenecks of the digital transformation of the justice system in Portugal – connectivity and legacy systems.

Coverage and level of development of ICT/digital infrastructure

Copy link to Coverage and level of development of ICT/digital infrastructureCoverage and level of development of ICT/digital infrastructure looks at the availability, speed, latency, bandwidth, coverage, network and energy usage of Internet connectivity as the result of the country’s digital infrastructure policies (OECD, 2021[18]). A good coverage and level of development of ICT/digital infrastructure is fundamental to access and delivery of justice services across the country and enables greater digital inclusion. A sub-optimal coverage and level of development of ICT/digital infrastructures not only increases the digital divide between areas with fair and poor connectivity but also hampers service delivery and access to justice more broadly.

In 2022, Portugal reported a proportion of 88% of households with Internet access in 2022 (below the EU average of 93%). More importantly, the gap between cities and rural areas in household Internet access reached 14% and the proportion of people that had never used the Internet in Portugal was 14% (Eurostat, 2022[19]). The level of Internet access and use are also influenced by income level and people’s age. This is particularly relevant in the case of Portugal, with one of the oldest populations in Europe. The elderly (over 65) represent 24% of the country’s total population (OECD, 2022[20]). One of the main goals of the Action Plan for Digital Transition (see Contextualising digital transformation in Portugal’s justice system) is to promote the creation of conditions for generalised, easy and free access to the Internet. The Action Plan for Digital Transition foresees measures such as the creation of a social tariff for access to Internet services and the development of an educational project for the digital inclusion of one million adults lacking access to ICT/digital infrastructure.

Investment in making legal information available and delivering judicial services online seems to be a priority in Portugal. This is demonstrated by the development of the online Practical Guide to Justice and the implementation of the RAL+ platform. Nevertheless, respondents of the 2023 Portuguese LNS did not indicate “online access to legal information” as primary source of information. Another example demonstrates the need to invest in diverse channels. The dedicated telephone helpline operated by the DGPJ is frequented by many justice service users looking for information on ADR. Investing in online platforms to deliver information should not overlook the need to consider other channels for those with greater difficulty in accessing information on the Internet.

Portugal should sustain its efforts to improve Internet coverage through continued investments and innovation, as it has been doing in the past years. Looking ahead, the country could consider aligning the design and delivery of justice services with strategies on coverage and level of development of ICT/digital infrastructure. This includes supporting access to infrastructure for those who cannot afford it and promoting training programmes to increase digital literacy. Furthermore, mindful of the Portuguese context, it is important to recognise the value of the omni-channel approach to engage users and ease access to legal information and services, as well as the role digital technologies and data can play in achieving the omni-channel approach. This could enhance Portugal’s efforts to bridge the digital divide and provide a seamless user experience.

E-government heritage and legacy

Copy link to E-government heritage and legacyThe e-government approach tends to make the implementation of technology the focus, especially in the context of digitising existing government processes and services. In the rush to make things available online, the result has been government-centred services, reproducing analogue bureaucratic procedures online (OECD, 2020[21]). As a consequence, this has resulted in government practices that do not respond to users’ needs, including siloed approaches to the design of policies, duplications of services and legacy technologies.

The diagnostic phase of the project identified some challenges in mobilising digital technologies to enhance a people-centred approach. Fact-finding interviews, a government questionnaire, and desk research suggested issues to do with legacy technologies, multiplication of channels, and lack of joint prioritisation and co-ordination across institutions within and beyond the public sector. This has had some important implications, including users’ distrust in certain platforms.

The fact-finding interviews showed stakeholders’ recognition of the importance of digital technologies and data to improve the efficiency of the justice system and justice actors’ daily work. However, the focus seems to largely remain on the use of online platforms to submit requests and communicate during a process, and less on the strategic use of digital technologies and data to address people’s needs. Another challenge identified was the lack of joint prioritisation for developing new interoperable services among different entities and governmental areas. This is crucial to ensure alignment of investments and activities.

The digital transformation of the justice system in Portugal has gone through different stages of development that have unevenly affected the various entities involved. Over time, sector-specific investment has exacerbated the challenge of dealing with legacy channels, technology and infrastructure. Most recent projects have sought to address these issues. Several examples of these various stages can be found in the different institutions of the justice system.

In courts, for example, the first attempt to use digital technologies for case management started in 1999, with a project addressed to and developed by court clerks. Citius, the current information system to support the work of the courts, was introduced in 2007 and gradually extended to the various judicial courts (European Judicial Network, 2024[22]).

In parallel, in 2004, SITAF was introduced. The implementation of a dedicated information system for the administrative and fiscal jurisdiction was conceived as part of the overall reform, and developed with the aim of simplification, rationalisation of resources, and dematerialisation. Although this platform was used for electronic filing and processing of cases before Citius, it was widely underused and identified as a source of serious constraints.

SITAF has generated distrust among users due to constant system crashes and a perceived complexity of use. Because lawyers did not trust the information system, the same pleading was often sent to the courts in different formats – uploaded in the platform, sent by e-mail or by post. This multiplication of copies of the same pleading led to additional work for the court registries and, often, to duplication of cases, as more than one case would be opened based on the different copies received through different channels.

In 2013, a new architecture of the system was designed, but it was not until 2017 that the enhancements became visible and SITAF gained new noticeable functions. The different perceptions of the functional performance of these two information systems led to constant comparisons between them. It was mentioned during fact-finding interviews that the possibility of using Citius or merging the two information systems were a constant topic of discussion among justice users (e.g. judges, court clerks, lawyers), especially with those who work with Citius and, in general, recognise its greater potential.

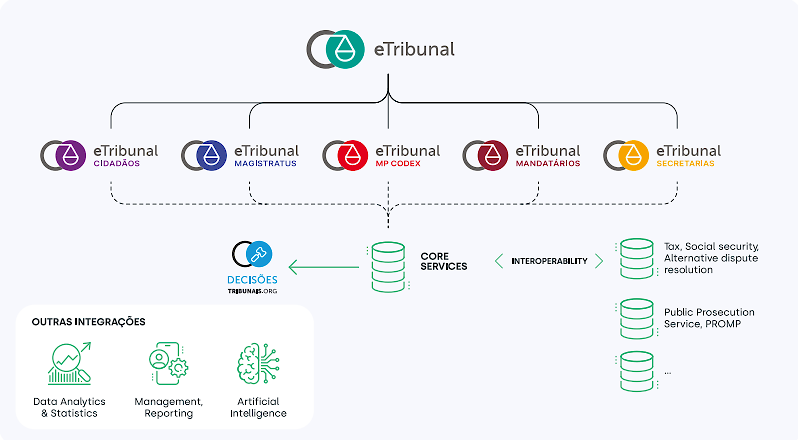

Under the Justiça + Próxima programme, the Portuguese justice sector started integrating these court information systems (see Figure 8.1). From the end of 2023, eTribunal Magistratus and eTribunal MP Codex became the main access points for judges and prosecutors, respectively, to the court system for both jurisdictions (ordinary, and administrative and fiscal) and included the functionalities previously available in Citius and SITAF. New functionalities have also been introduced. This includes the automation of tasks and the implementation of mechanisms to facilitate research, namely case law, thus streamlining the judicial process.

New applications for lawyers and the general public have been introduced to improve user experience and to increase the number of accessible digital services. The eTribunal Mandatários was introduced as a new interface for lawyers, granting unified access to ordinary, administrative, and tax courts. It enables lawyers to view electronic communications by the courts, as well as by the secretariats of the National Injunctions Counter (BNI), the National Leases Counter (BNA), and the Leases Injunction Service (SIMA) from a single platform. Additional features include e-mail alerts for new electronic filings and notifications of procedural events in specific cases. Other features under development include direct access to court proceedings and updates on changes of lawyers' professional addresses.

Figure 8.1. Portugal: Court’s information system eTribunal

Copy link to Figure 8.1. Portugal: Court’s information system <em>eTribunal</em>

Note: Only available in Portuguese.

Source: Government of Portugal (2024[23]), Justice Digital Transformation.

Another example of information system developments is from the registration services (land registry, car registry, civil registry, and commercial registry), which was one of the areas that significantly benefited from the Simplex programme. Between 2004 and 2006, Portugal launched SIRCOM (Integrated Commercial Registry System), SIRP (Integrated Land Registry System), SIRIC (Integrated Civil Registration and Identification System) and DUA (Single Automobile Document), a set of systems that enables the dematerialisation of acts, processes and documents. Following their implementation, a major challenge has been ensuring seamless communication between these systems and the information systems of the courts and the Ministry of Justice, especially for services like the registries that need to interact with the courts at certain stages of judicial proceedings.

Another clear example of the challenges posed by years of specific sectoral investments is the development of multiple websites that provide legal and justice information in recent years not only from the government but also from multiple entities in the area of justice (e.g. courts, public prosecution service, the justice of the peace courts, alternative dispute resolution institutions). Despite the efforts made with the creation of the Digital Justice Platform in 2017, information is still scattered across several of the government's own websites, running the risk of becoming outdated. Fact-finding interviews suggested that search tools and scattered official websites of both the Ministry of Justice and other entities (e.g. courts, justice of the peace, ADR) are the most visible sources of information to users about entities’ competences and services available.

The issues mentioned above, including legacy technologies, multiplication of online platforms, and the lack of joint prioritisation and co-ordination across institutions, share a common e-government approach that is focused on technology. Gradually, Portugal has been moving away from this approach. The principles of interoperability, reuse of information and sharing of resources are some of the main priorities of the Justice + Proximity programme, also with a view of fostering inter- and intra-institutional collaboration. Interoperability between the information systems of other government sectors and those of the justice sector services are thus among the main objectives of the programme. Some of the most important initiatives in recent years have been to improve interoperability and thus the capacity of different information systems to communicate and exchange information smoothly.

Portugal should consider applying a digital-by-design approach, embedding digital technologies and data to reengineer and redesign services and processes with the focus of meeting users’ needs. This includes securing through DGPJ the long-term vision and governance mechanisms for the coherent implementation of service design, delivery and data strategies in the justice sector.

Likewise, establishing a permanent strategic co-ordination body for service design and delivery of justice would help joint-prioritisation and cross-government commitment to cut through organisational siloes, thus helping ensure consistency of experience from users’ perspective. This would also help move away from sector-specific investments and contractual arrangements that have exacerbated the multiplication of channels. This co-ordination body could involve relevant justice stakeholders such as the Ministry of Justice, DGPJ, IGFEJ, Supreme Council of the Judiciary, Supreme Council of Administrative and Tax Courts, Public Prosecution Office, ISS Bar Association, and ADR service providers, in addition to government agencies (notably the Administrative Modernisation Agency [AMA]) in charge of broader digital transformation efforts in the public sector.

8.2.2. Leadership

Copy link to 8.2.2. LeadershipOne of the key elements to achieving digital transformation is political commitment and institutional leadership (OECD, 2014[17]). This includes clearly communicating a shared vision and priorities, and promoting co-ordination and collaboration across organisations (OECD, 2020[24]). In the context of modernisation efforts, the role of senior leaders as champions for digital transformation and promoting a digital culture and mindset have been increasingly recognised as a requirement by OECD member and non-member countries (OECD, 2020[24])

Portugal has benefited from the strong political commitment of leaders. High-level leadership has often publicly supported the modernisation of justice in Portugal (Government of Portugal, 2023[8]) (Government of Portugal, 2024[9]). Some examples are their in-person participation and support of digital transformation initiatives such as hackathons, training programmes and calls for innovation such as the Desafios Justiça (see Box 8.4).

Box 8.4. Portugal: Leveraging innovation in justice – Desafios Justiça

Copy link to Box 8.4. Portugal: Leveraging innovation in justice – <em>Desafios Justiça</em>Desafios Justiça is an initiative that aims to contribute to the development of innovative technological solutions that respond to the concrete needs of justice services’ users. The initiative is part of Govtech Justiça, under the component “Identify and co-create”. Its objective is to promote exchange and foster synergies and co-creation processes between the public sector, academia, research centres and the national, European and international innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems to experiment and test ideas.

The calls for innovation are launched by public organisations and are open to both natural and legal entities. Applications are submitted through a specific form and selected candidates present their ideas to a jury. The first challenge was launched at the beginning of 2023, with INPI as the promoting organisation. On 29 September 2023, four selected applications were presented at an event held at the Justice Hub.

Source: Government of Portugal (2024[25]), Desafios Justiça, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt/participar/#desafios.

Commitment is also shown at ministerial level through clear communication of the government’s vision to digital transformation in justice, and even more specifically through the allocation of budget for modernisation initiatives (Sarmento e Castro, 2022[10]) (Government of Portugal, 2024[26]). This commitment and a strong leadership for its modernisation agenda in the justice system can be seen in the various competences attributed to bodies. The General Secretariat of the Ministry of Justice ensures co-ordination, efficiency and effectiveness within the Ministry of Justice. Among other important roles, the General Secretariat oversees the development and implementation of the strategic view of digital transformation and innovation within the Ministry of Justice, namely the Justiça + Próxima plan and SIMPLEX programme, ensuring alignment between initiatives and the ministry’s operational and strategic needs (Government of Portugal, 2022[27]). The General Secretariat also fulfills an important role of co-ordination of cross-departmental projects and programmes, including those involving international co-operation and aimed at reforming and modernising the justice system.

Other institutions have important functions in the Portuguese justice governance landscape (see People-centred justice data in justice sector institutions in Portugal in Chapter 6). In the context of digital transformation of justice, DGPJ and the Justice Institute for Financial and Equipments Management (IGFEJ) have a prominent role. DGPJ is responsible for supporting the Ministry of Justice in policy formulation, planning, evaluation, and co-ordination of the justice sector in close collaboration with the General Secretariat of the Ministry of Justice. DGPJ also plays a key role in the administration of justice in Portugal, overseeing various aspects of the justice system, including the modernisation of judicial services. Its activities are aimed at improving the efficiency, accessibility, and quality of the justice system to meet the needs of the public and ensure the effective administration of justice.

IGFEJ plays a pivotal role in Portugal's justice system by managing the financial, human resources, and technological infrastructure within the Ministry of Justice. Its responsibilities include developing, implementing, and managing ICT systems – from case management systems to secure communication networks that enable the efficient operation of the justice system. In close co-ordination with the General Secretariat of the Ministry of Justice, IGFEJ actively works on initiatives aimed at modernising the justice system through digital technologies, data and innovative practices. It develops proposals for articulation with Portugal’s strategic plans of modernisation of justice, taking into account technological evolution and the overall training needs in the justice sector. IGFEJ oversees the budgeting, accounting, and financial management of resources allocated to the justice sector. This includes ensuring the appropriate distribution and utilisation of funds within the various entities under the Ministry of Justice.

While Portugal currently has strong political leadership in the digital transformation of justice, efforts in strengthening the institutional leadership need to be sustained over time across political mandates and government composition. The country should continue investing in capacity-building and engaging with stakeholders within and outside the public sector to help maintain knowledge, embed the agenda within the fabric of government operations and sustain commitment over time.

Furthermore, there is an untapped opportunity to further institutionalise certain priorities, such as the GovTech Justiça (see Strategy and plan) by formalising them into legal documents. This could ensure continuity and sustainability of priorities and strategic view, resulting in a more enduring impact. For instance, the sustainability of digital transformation initiatives can be at risk due to a lack of alignment between policies and budget. While there is an overall four-year plan which sets priorities (“Grandes Opções do Plano”), budget allocation does not always align with the defined goals and priorities, and is renegotiated on an annual basis, making long-term planning difficult. Setting clear strategic priorities in legal documents or regulations may help ensure the execution of the agenda and continuity of initiatives in the long-term.

Strengthening the institutional leadership to govern justice data is also crucial for driving the justice sector’s modernisation agenda forward. This would allow Portugal to promote a data-driven approach across the justice ecosystem and foster collaboration among different stakeholders. It is also important to ensure that all stakeholders acknowledge that data governance is multifaceted, involving not only technology but also organisational structures, policy levers and changes in the organisational culture.

8.2.3. Strategy and plan

Copy link to 8.2.3. Strategy and plan“Strategy and plan” examines the existence of a strategic document that sets the vision, clear objectives, key actors involved and action items in line with other relevant policy objectives and which are to be carried out in an effective, efficient and organised manner. A strategy for the digital transformation of the justice system should detail a vision, goals and milestones, the stakeholders, their respective activities, funding and ideally key performance indicators (KPIs) and monitoring mechanisms (OECD, 2021[18]).

Portugal is one of the few countries introducing a comprehensive package of administrative simplification, digitalisation and innovation measures with the aim to bring justice closer to people. In line with Portugal’s broader agenda on digital transformation in the public sector (see Contextualising digital transformation in Portugal’s justice system), the country has made significant efforts to advance the agenda at sectoral level in justice. The Justiça + Próxima programme (see Box 2.,) and, more recently, the Justiça+ and the GovTech Justiça are a step forward in leveraging digital technologies and data, and taking innovative approaches to design and deliver justice services.

Some of the initiatives in Justiça+ reflect a comprehensive effort to integrate digital technologies and data across the Portuguese justice system, aiming to enhance efficiency, transparency and access to justice services. While Chapter 2 provides an overview of Portugal’s strategic documents and initiatives, and a general overview of Justiça+, Box 8.5 details some of its initiatives in the area of digital transformation.

Box 8.5. Portugal: Leveraging Justiça + to promote digital transformation in the justice system

Copy link to Box 8.5. Portugal: Leveraging <em>Justi</em><em>ç</em><em>a +</em> to promote digital transformation in the justice systemJustiça + is a comprehensive effort aimed at broadly modernising the country's justice system. Within the programme’s 10 key responses to advance a people-centred justice in Portugal, the following initiatives are contemplated with a focus on using digital technologies and data to attain the programme’s main goal:

Strengthening resilience of information systems: Investing robustness of infrastructure, capacity-building and the development of new systems in courts and judicial police.

Improving interoperability: Enhancing integration between the information systems of administrative and tax courts and the Tax Authority for electronic citations.

Optimising case management in courts: Improving functionalities in MP Codex and Magistratus. This includes automating more tasks and enhancing search mechanisms.

Enhancing online platforms and expanding their usability: This includes broadening access to the RAL+ platform to all peace courts and consumer dispute arbitration centres that are part of the consumer arbitration network. In addition, Justice + sets as target the introduction of new features in the Empresa Online 2.0 platform to streamline the business lifecycle, including creation, management, financial reporting and closure. These changes aim to improve integration, reduce redundant data provision and allow access to all necessary information and services in a single space.

Anonymising judicial decisions: Implementing an integrated solution for the anonymisation of judicial decisions through algorithms.

Launching GovTech initiatives: By promoting involvement with academia, research on innovation, and creating the conditions to make data available, accessible and reusable within and outside the public sector.

Source: Government of Portugal (2023[28]), Justiça +, https://mais.justica.gov.pt/#continuaravancar.

Portugal has been taking a forward-looking approach in its efforts to promote digital transformation of is justice system. One concrete example is the launch of GovTech Justiça. GovTech Justiça (see Box 8.6) stems from proposal 4 of Justiça +, “Innovate in justice”, and Portugal’s broader efforts on digital transformation of the public sector. GovTech Justiça shares with Justiça + the steering concept of leveraging digital technologies and data to improve service delivery in the justice system.

Launched in February 2023, GovTech Justiça aims to consolidate a culture of innovation in the justice sector. The starting point of the strategy is building synergies with relevant stakeholders to identify priorities and co-design solutions that help address users’ needs. GovTech Justiça emphasises the use of emerging technologies, innovative approaches and building shared solutions with universities, research centres and start-ups. It has IGFEJ as the co-ordinating body responsible for the shared technological dimension and for overseeing the management of the Justice Hub, the physical space for the strategy’s implementation.

As an evolving strategy, GovTech Justiça is continuously being developed with the Justice Hub at the centre of its implementation. The government has also secured resources clearly allocated in the RRP (Government of Portugal, 2024[29]).

Box 8.6. Portugal: GovTech Justiça

Copy link to Box 8.6. Portugal: <em>GovTech Justi</em><em>ç</em><em>a</em>Launched in February 2023, the GovTech strategy has three goals:

1. To accelerate the modernisation and digital transformation of the justice system in Portugal;

2. To foster a culture of collaborative innovation by bringing justice entities closer to national and international innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems;

3. To identify and share good practices on the use of emerging technologies, as well as govtech and legaltech projects.

The strategy has led to the creation of several initiatives, including:

LAB Justiça, an executive education programme in partnership with universities in the areas of strategic management, digital transformation and leadership;

Desafios Justiça, a set of open calls for innovators to present solutions to concrete issues in justice;

The consolidation of an innovation framework for the justice system;

The development of a strategic plan for the Justice Hub;

The automation of the company name pool, which allows the automatic creation of company names, using artificial intelligence algorithms. This helps streamline the creation of companies and eliminates the execution of a task that was entirely manual in the past;

Authenticity validation for online citizenship applications. This allows online submission of citizenship applications and helps dematerialise the procedure;

The BUPi app, which allows owners to capture the geographic co-ordinates of their land on site and, thus, start the process of registering it through the BUPi platform, Balcão Único do Prédio;

The BUPi geographic services platform (GeoHub BUPi), which is based on a highly available, scalable, resilient (disaster recovery) and secure geographic services platform to provide content to the BUPi Viewer and partner entities;

The Darlene project, aimed at law enforcement agencies, develops applications with the support of augmented reality. The project aims to equip law enforcement agents to improve their physical and mental processing capability, and increase situational awareness and support decision-making in critical situations;

A beta version of the Practical Guide to Justice (GPJ), an online service based on GPT-4.0 language model. By March 2024, the service was trained to provide information in the areas of online criminal records, ADR, marriage, divorce and company creation.

Source: Government of Portugal (2023[30]), GovTech Justiça, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt; Government of Portugal (2024[31]), GovTech Justiça: Projetos, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt/projetos/.

GovTech Justiça has given rise to visionary initiatives in the justice system. The strategy makes Portugal a pioneer in the use of digital and emerging technologies to enhance the delivery of people-centred services, improving overall access to justice.

An example of a forward-looking initiative carried out as part of GovTech Justiça is the Practical Guide to Justice (GPJ) (see Box 8.6). The initiative was launched in March 2023 in an effort to make information more accessible to citizens and businesses. The GPJ facilitates the identification of the most appropriate justice services in certain areas in a transparent and intuitive manner. For example, the GPJ’s website provides important disclaimers about the tool’s aims and limitations, and explains how the tool generates and manages information collected. The project results from a partnership between DGPJ, Genesis.studio (a software company) and Microsoft. Beginning in February 2024, DGPJ has incorporated a mechanism for collecting user feedback on responses that the GPJ offers.

While Portugal has advanced digital transformation of the justice system through implementation of government-wide and sector-specific strategies, there is still an opportunity to yield a greater impact by defining a long-term plan to achieve its vision and setting a clear monitoring mechanism to ensure the continued relevance of the strategic documents and plans over time.

During the fact-finding interviews, many stakeholders voiced common challenges in understanding the wider vision of the strategies and action plans, inter-linkage among different measures and the rationale behind prioritisation of initiatives. These concerns may lead to disengagement in developing and implementing cross-cutting justice services that require the involvement of multiple parts of the justice sector. The interviews also identified the lack of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, along with limited engagement of justice stakeholders in evaluation outcomes and assessing user satisfaction (see Strategic partnerships). Apart from some satisfaction surveys, there is no systematic monitoring and evaluation of the impact of justice services and people's experiences in using justice services.

Institutionalising GovTech Justiça would support Portugal to address these challenges as it is the predominant strategy in the digital transformation of the Portuguese justice system. GovTech Justiça clearly presents its aim, dimensions and initiatives in an agile format on the website govtech.justiça.gov.pt. Nevertheless, formalising GovTech Justiça into a structured legal document would help ensure wider buy-in, continuity and sustainability of the strategy across political terms and budget cycles.

Furthermore, defining a clear long-term plan for GovTech Justiça may help bring more clarity on shared priorities for the justice system as a whole. This includes creating a shared vision for the strategy, as well as setting tactical and operational aspects for its implementation. The plan should identify how specific stakeholders can act on the strategy through various governance mechanisms and arrangements, with clearly defined roles, responsibilities and deliverables. Setting clear priorities and activities in the plan can also better align policies and budget. Portugal might consider developing an investment plan to address the financial resources needed for specific activities or initiatives within the plan. This would help ensure the continuity and sustainability of GovTech Justiça over time across political mandates and government composition.

Finally, establishing a clear monitoring and evaluation mechanism for GovTech Justiça would support Portugal to sustain its success in the long run. This involves setting out key performance indicators (KPIs) in an open and transparent manner, aligned with the stated objectives and deliverables (see Box 8.7. In addition, the mechanism should enable evaluating outputs, outcomes and impacts achieved to allow continuous improvement on an ongoing basis (OECD, 2021[18]).

Box 8.7. Korea: Monitoring mechanism of digital government initiatives

Copy link to Box 8.7. Korea: Monitoring mechanism of digital government initiativesThe government of the Republic of Korea has established a monitoring mechanism to track the progress and effectiveness of its digital government initiatives. It demonstrates the government’s commitment to transparency, efficiency and accountability. The mechanism contains different components to ensure that its digital transformation efforts are effectively implemented and aligned with user needs.

The digital government usage survey

In accordance with the Electronic Government Act, the survey is conducted annually to evaluate service usage rates and public perception of digital government services. The survey outcomes are published openly to ensure transparency and accountability. The survey data is also accessible through the Korean Statistical Information Service (kosis.kr) and the Public Data Portal (data.go.kr).

The performance management system

The government uses a performance management system outlined in the digital government performance management guideline. Central government institutions need to follow the performance management manual to manage their performance effectively and efficiently during digital government projects or initiatives. The Ministry of the Interior and Safety also provides guidelines for defining performance indicators for digital/ICT projects to ensure consistency and effectiveness across the public sector.

The government performance evaluation portal

Each ministry’s key performance indicators (KPIs) are integrated into the government’s performance evaluation system. Evaluation outcomes are publicly available on the portal.

Source: Government of Korea (2023[32]), Electronic Government Act, https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=electronic+government+law&x=35&y=28#liBgcolor0; Government of Korea (2024[33]); Government Performance Evaluation Committee; https://evaluation.go.kr/web/index.do.

Another area Portugal can benefit from is developing a long-term strategic vision on the use of AI in the justice system. The absence of such a strategic view can hinder responsible and trustworthy use of AI with potential inefficiencies and inconsistencies in justice systems and services. This can also deepen challenges such as lack of co-ordination in the implementation of solutions, inconsistent standards and practices, and most importantly, distrust in the justice sector.

AI systems are prone to bias if not properly designed and monitored. Without the clear strategic direction that emphasises ethical AI use, there is a risk of deploying AI solutions that perpetuate historical biases, leading to unfair treatment of certain groups. Likewise, AI-leveraged services may compromise data privacy and jeopardise trust levels of digital transformation initiatives in justice if standards for data protection are not set and measures to address security risks established. To address this issue, it is important that Portugal consider embedding its strategic vision for AI use and key principles in GovTech Justiça and Justiça +. As Portugal has already developed the national strategy for AI (“AI Portugal 2030”), it would be important to consider applying its vision and values, and adapt them to serve the needs of the justice sector (see Box 8.8). In addition, Portugal would also need to foster a shared understanding of AI among justice actors and service users broadly. This includes communicating transparently and regularly on the purpose, risk, benefits and good-use cases of AI in the justice sector.

Box 8.8. Portugal: National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence (AI Portugal 2030)

Copy link to Box 8.8. Portugal: National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence (AI Portugal 2030)The National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence was launched in June 2019 and promoted by the Portugal INCoDe.2030 in collaboration with other entities, including the Science and Technology Foundation (FCT), the National Innovation Agency (ANI), Ciência Viva and the Administrative Modernisation Agency (AMA).

Developed under “Research”, the fifth axis of Portugal INCoDe.2030, the strategy syncs with the European Co-ordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence and rests on seven foundational pillars:

1. Enhancing societal well-being;

2. Boosting AI competencies and digital literacy across the population;

3. Encouraging the creation of new employment opportunities and an AI-driven services economy;

4. Establishing Portugal as an experimental hub for AI innovation;

5. Identifying and exploiting specialised AI market niches in Portugal;

6. Supporting AI research and innovation for knowledge generation and technological advancement; and

7. Improving public services for both citizens and businesses by integrating data-driven methodologies in policy-making and administrative decisions.

Overall, this strategy seeks to position Portugal at the forefront of both fundamental and applied AI research, elevate workforce qualifications, and leverage AI technology for economic advancement. Under the AI national strategy, INCoDe.2030 plans to:

Enhance visibility and support for AI initiatives by public and private sectors, academic institutions, and innovation hubs;

Organise webinars addressing AI-related subjects;

Launch the PT AI WATCH platform for an extensive overview of AI projects;

Advocate for digital and AI skill development;

Reevaluate and update existing AI strategy to craft a new National AI Strategy and Implementation Plan.

Aligned with the European Union's Digital Decade vision, preparations for a revised strategy tailored to Digital 2030 goals are currently underway.

Source: Government of Portugal (2019[34]), National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence, https://portugaldigital.gov.pt/en/accelerating-digital-transition-in-portugal/get-to-know-the-digital-transition-strategies/national-strategy-for-artificial-intelligence/.

8.2.4. Co-ordination and co-operation

Copy link to 8.2.4. Co-ordination and co-operationCo-ordination and co-operation play a crucial role in the successful implementation of policies and initiatives. Effective co-ordination and co-operation enable governments to navigate the complexity of digital transformation, aligning the efforts of various actors towards common goals, reducing duplication of efforts and ensuring coherence across different parts of the government. This can also contribute to enhancing transparency, accountability and trust in government. In addition, transparent processes would empower the public to engage, reinforcing trust in the government’s initiatives. Co-ordination and co-operation require clear mandates, and roles and responsibilities among public sector stakeholders to implement strategies and action plans that cut across levels of government and policy areas (OECD, 2021[18]).

Taking into account the strategic direction discussed in the following section, building strategic partnerships is among the most important elements in the context of the justice sector in Portugal.

Strategic partnerships

Copy link to Strategic partnershipsThe involvement of public, private, and civil society stakeholders in the design and delivery of justice policies and services is key for transforming justice systems to be more people-centred. Engaging these diverse groups ensures that justice policies and services are innovative, efficient and reflective of the community's needs. This collaborative approach promotes transparency, trust and accessibility, making the justice system more responsive to the people it serves. Furthermore, joint efforts have the potential to increase policy stability, reducing dependence on political will.

The concept of strategic partnerships for better public services is not new in Portugal. This is at the heart of the philosophy behind the development of the Simplex programme. The programme was launched in 2006 with the primary goal of simplifying access to public services for people and businesses by cutting red tape, reducing compliance costs and leveraging digital technologies and data to enhance service delivery. Each year, all government departments, companies, associations, and citizens can propose initiatives to be included in the programme (Government of Portugal, 2024[35]).

The Justiça + Próxima programme implemented the same approach and promoted a culture of collaboration. It benefitted from the contribution of 15 entities in justice, including the Supreme Council of the Judiciary, the Supreme Council of the Administrative and Tax Courts, and the Office of the Prosecutor General. The programme aimed to involve civil society organisations in developing solutions to the challenges in the justice sector. Portugal has taken the strategic partnerships even further with GovTech Justiça. It facilitates collaboration between the private and public sectors, as well as universities, research centres and start-ups, to transform the design and delivery of justice services through innovative digital initiatives.

The fact-finding interviews also highlighted several efforts to engage diverse stakeholders from the early stage of the service design process in Portugal. Prominent examples include the RAL+ initiative, which aims to modernise alternative dispute resolution (ADR) by establishing an online platform for mediation and justice of the peace courts. For this project, various stakeholders across the justice system have participated in design sessions and interviews, with the purpose of gathering insights and inputs for the development of the service according to stakeholders' needs. Other examples are Magistratus and MP Codex, which considered the participation of specific groups of users in the design process of these platforms.

Although Portugal has made significant efforts to engage stakeholders from the outset in the design and delivery of justice services, there is still room for improvement to maximise strategic partnerships across the justice sector, leveraging current initiatives.

Portugal should consider taking an iterative approach to engage various stakeholders throughout the entire service cycle. In the case of Magistratus and MP Codex, for instance, while workshops and interviews were organised to extensively involve stakeholders in the design of justice services (Government of Portugal, 2024[23]), some interviewees expressed concerns about the status of the projects due to limited follow-up after these meetings and working sessions, including the absence of feedback on stakeholders’ inputs. This can demotivate and compromise stakeholders’ involvement over time.

To address this issue, Portugal could consider organising follow-up activities to test and learn before committing to launching a service. This would provide an opportunity to better reflect the needs of the stakeholders and correct course in response to their needs. In addition, setting a clear communication plan to transparently communicate progress of design and delivery of these services may also help improve engagement with stakeholders throughout the design cycle. Portugal may also want to consider keeping accessible records of consultation processes and background documents, communicating proactively with stakeholders about processes and decisions, and creating feedback loops to inform the design process.

Portugal can also capitalise on the Justice Hub to be a central point for building strategic partnerships in the justice sector. The Hub can facilitate knowledge creation, project development and a community of practice across the public and private sectors, academia and the civil society. The Hub can provide the necessary support, resources, and momentum to drive meaningful change and modernisation of the justice sector. To attain such objectives, Portugal might consider setting a strategic plan and developing a sustainable operational model for the Hub. Concretely, some actions may include defining a configuration of functioning process (e.g. clear mandates and service catalogues), developing training guidelines for capacity-building, and setting management mechanisms (e.g. core team skills and capabilities, definition of resources, operational guidelines, and roles and responsibilities of members of the Hub) for the Hub.

8.2.5. Empowerment of justice actors

Copy link to 8.2.5. Empowerment of justice actorsAs countries embrace the use of digital technologies and data to respond to the needs of the economy and society, this requires a capable workforce to work across organisational silos and public institutions equipped to place the needs of people at the core of the design and delivery of policies and services. Achieving these outcomes relies on skills and a learning culture.

With the rapid evolution of digital technology, digital skills need to be able to mature and respond over time. Therefore, it is crucial to create an environment that encourages staff to continuously learn and grow. Leaders have the responsibility of promoting the establishment of such an environment and supporting digital skills initiatives. To encourage digital transformation across the public sector, an organisation needs to embrace a learning culture at all levels. This starts with leadership creating a safe environment for employees to experiment, learn and develop through testing, iterating and even failing (OECD, 2020[24]).

Portugal has implemented several initiatives to enhance the digital skills of the public sector in the past years. In addition to embedding skills in broader national strategies, such as the Strategy for the Digital Transformation of Public Administration 2021–2026 and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, the country launched the National Digital Competences Initiative e.2030 (Portugal INCoDe.2030), that aims to provide basic digital skills to Portuguese citizens and upskill public servants to accelerate the digital transformation in the public sector.

To implement Portugal’s skills strategies, the country has been implementing important initiatives, including the Programme for the Development of Digital Skills for public servants (Government of Portugal, 2024[36]), the Centre for Digital Competences of the Public Administration (Government of Portugal, 2018[37]) and the AMA Academy (Government of Portugal, 2024[38]). Despite differing in some of their specific initiatives, they provide training and education programmes to equip public servants with skills needed in a digitally-enabled public sector, and foster a culture of innovation, collaboration and responsiveness to the needs of people (e.g. through knowledge-sharing, best practices, partnerships).

Portugal has also launched digital skills initiatives to equip stakeholders beyond the public sector. Some of these main initiatives include Jovem + Digital programme (Government of Portugal, 2020[39]), a training programme for acquiring digital skills aimed at young adults; the Digital Skills Certificate programme, which aims to improve the digital skills of the Portuguese population, enhancing their social inclusion and employability (Government of Portugal, 2021[40]); and Academia Portugal Digital, designed to enhance the digital skills of the Portuguese population, including professionals, students, and the general public, to meet the demands of the digital economy and support digital transformation across various sectors. This last initiative likely involves collaboration between public and private entities to facilitate access to digital learning opportunities and foster a digitally skilled workforce in Portugal (Government of Portugal, 2024[41]).

In the justice sector, the Centre for Judicial Studies (CEJ) offers continuous training and education for legal professionals, including judges and public prosecutors. These programmes cover various areas, including new legal frameworks, digital skills, and innovative practices in the justice sector. Within GovTech Justiça, certain sporadic initiatives, such as Lab Justiça, help strengthen the skills of various actors in justice services on strategic management, digital transition and leadership in a context of change (see Box 5.2). This investment in capacity-building is particularly relevant in the context of executing projects and reforms envisioned in the PRR.

Portugal could draw inspiration from its own initiatives in the executive branch to continue developing projects that aim at empowering justice actors, including justice service users. This includes, for instance, expanding the offer and continuity of training programmes, building on existing sporadic initiatives such as Lab Justiça training programmes (see Box 5.2). In addition, there is an untapped opportunity to leverage the Justice Hub as a platform to promote capacity-building, peer-learning, knowledge-sharing and creating a community of practice for stakeholders in the areas of digital transformation and innovation in justice.

References

[22] European Judicial Network (2024), Online processing of cases and e-communication with courts, https://e-justice.europa.eu/content_automatic_processing-280-pt-maximizeMS_EJN-en.do?member=1.

[19] Eurostat (2022), Digital economy and society statistics - households and individuals, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Digital_economy_and_society_statistics_-_households_and_individuals#Internet_access.

[28] Government of Justice (2023), Justiça+, https://mais.justica.gov.pt/.

[33] Government of Korea (2024), Government Performance Evaluation Committee, https://evaluation.go.kr/web/index.do.

[32] Government of Korea (2023), The 2023 digital government usage survey, https://www.mois.go.kr/frt/bbs/type001/commonSelectBoardArticle.do?bbsId=BBSMSTR_000000000014&nttId=106158.

[26] Government of Portugal (2024), C18 Justiça económica e ambiente de negócios, https://recuperarportugal.gov.pt/justica-economica-e-ambiente-de-negocios-c18/.

[14] Government of Portugal (2024), Capacitar para inovar, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt/capacitar-para-inovar/.

[25] Government of Portugal (2024), Desafios Justiça, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt/participar/#desafios.

[38] Government of Portugal (2024), Home, https://academia.ama.gov.pt/.

[41] Government of Portugal (2024), Home, https://academiaportugaldigital.pt/.

[9] Government of Portugal (2024), IGFEJ hosts Forum for Innovation and Technology in Justice, https://igfej.justica.gov.pt/Noticias-do-IGFEJ/IGFEJ-recebe-Forum-para-a-inovacao-e-Tecnologia-da-Justica.

[23] Government of Portugal (2024), Justice Digital Transformation.

[35] Government of Portugal (2024), Livro, https://www.simplex.gov.pt/livro.

[11] Government of Portugal (2024), Login, https://ralmais.dgpj.justica.gov.pt/ords/f?p=102:LOGIN_DESKTOP::::::.

[29] Government of Portugal (2024), Projects financed through RRP, https://igfej.justica.gov.pt/Projetos-financiados/Projetos-PRR.

[31] Government of Portugal (2024), Projetos, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt/projetos/.

[12] Government of Portugal (2024), Serviços online, https://irn.justica.gov.pt/online.

[36] Government of Portugal (2024), Training, http://www.ina.pt/index.php/centro-de-formacao-oferta-formativa.

[13] Government of Portugal (2023), Acesso mais simples na justiça: arrancou o eTribunal, https://www.portugal.gov.pt/pt/gc23/comunicacao/noticia?i=justica-arrancou-hoje-a-nova-interface-com-os-tribunais-.

[30] Government of Portugal (2023), GovTech Justiça, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt.

[8] Government of Portugal (2023), Technology at the service of justice: Discussions assessed the impacts of the digital transformation of justice, https://justica.gov.pt/Noticias/Debate-avaliou-os-impactos-da-transformacao-digital-da-Justica?pk_vid=e0268741b454535817092979129b03e3.

[16] Government of Portugal (2022), “Desafio da Justiça” will be launched soon, https://www.portugal.gov.pt/pt/gc23/comunicacao/noticia?i=desafio-da-justica-vai-ser-lancado-em-breve.

[15] Government of Portugal (2022), Engage companies, universities and science to transform justice, https://justica.gov.pt/Noticias/Envolver-empresas-universidades-e-ciencia-para-transformar-a-Justica.

[27] Government of Portugal (2022), Order no. 7122/2022, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/despacho/7122-2022-184357031.

[40] Government of Portugal (2021), Portaria n.º 179, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/portaria/179-2021-170322930.

[39] Government of Portugal (2020), Portaria n.º 250-A, https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/portaria/250-a-2020-146244078.

[7] Government of Portugal (2020), Resolution of the Council of Ministers 30/2020, https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/resolucao-conselho-ministros/30-2020-132133788.

[4] Government of Portugal (2020), Resolution of the Council of Ministers 55/2020, https://data.dre.pt/eli/resolconsmin/55/2020/07/31/p/dre/pt/html.

[5] Government of Portugal (2020), Resolution of the Council of Ministers 98/2020, https://data.dre.pt/eli/resolconsmin/98/2020/11/13/p/dre/pt/html.

[34] Government of Portugal (2019), AI Portugal 2030, https://portugaldigital.gov.pt/en/accelerating-digital-transition-in-portugal/get-to-know-the-digital-transition-strategies/national-strategy-for-artificial-intelligence/.

[6] Government of Portugal (2018), Council of Ministers’ Resolution 26/2018, https://data.dre.pt/eli/resolconsmin/26/2018/03/08/p/dre/pt/html.

[37] Government of Portugal (2018), Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 22/2018, https://dre.pt/web/guest/home/-/dre/114825660/details/maximized.

[1] OECD (2024), Developing Effective Online Dispute Resolution in Latvia, https://doi.org/10.1787/75ef5c4c-en.

[2] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[20] OECD (2022), Elderly population, https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm.

[18] OECD (2021), E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

[21] OECD (2020), Digital Government in Chile – Improving Public Service Design and Delivery, https://doi.org/10.1787/b94582e8-en.

[3] OECD (2020), Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a digital government, https://doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en.

[24] OECD (2020), The OECD Framework for digital talent and skills in the public sector, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en.

[17] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

[10] Sarmento e Castro, C. (2022), Speech by the Minister for Justice, Catarina Sarmento e Castro, as part of the specialised assessment of the 2023 State Budget proposal, https://app.parlamento.pt/webutils/docs/doc.pdf?path=6148523063484d364c793968636d356c6443397a6158526c63793959566b786c5a793944543030764e554e505269394562324e31625756756447397a51574e3061585a705a47466b5a554e7662576c7a633246764c7a45784f575135596d46694c57553559.