This chapter provides an overview of skills and competencies required from justice professionals in a people-centred and modern justice sector, based on the five pillars of the OECD Recommendation on Access to Justice and People-Centred Justice. It underscores the importance of skills development strategy for the advancement of justice reforms. The chapter outlines the methodology and findings of the recent skills survey conducted among justice stakeholders in Portugal. It discusses main strengths and gaps in terms of skills, management and organisational support related to each skill. By detailing the results of the survey’s dimensions, including the distribution of responses among respondents’ categories, the chapter provides a mapping of skills and competencies in the justice sector in Portugal. It also identifies needs and opportunities for capacity-building initiatives to empower justice stakeholders in supporting the transformation of the justice sector.

Modernisation of the Justice Sector in Portugal

5. Upskilling Portugal's justice sector: Towards a people-centred and digitally-enabled future

Copy link to 5. Upskilling Portugal's justice sector: Towards a people-centred and digitally-enabled futureAbstract

5.1. Identifying skills and competencies for a people-centred and modern justice sector

Copy link to 5.1. Identifying skills and competencies for a people-centred and modern justice sectorThe justice sector must continuously evolve to embrace shifting realities like digital transformation and transition towards people-centred approaches to effectively meet the legal and justice needs of different groups of people. This requires all stakeholders to adapt their skills and competencies to this changing environment. Data analysis, automation devices, big-data lakes, massive calculus potential applied to layers of data and information flows are altogether challenging the skills, the knowledge, and the cognitive frame through which all actors operating within the justice institutions and at the interface between societies and legal-justice systems need today and will need in the very near future. Furthermore, the demand and offer of legal and justice services now intersect in both physical and virtual spaces, such as courthouses, online dispute resolution (ODR) platforms, and virtual hearings. The quality of these spaces deeply influences the overall legitimacy of the legal and justice system. Therefore, professionals must navigate these changes effectively to ensure the continued credibility and effectiveness of the justice sector.

In particular, people working within the justice sector have a critical role in facilitating access to justice for those with legal and justice needs in a people-centred way. At the very core of justice institutions and services are the individuals who work to uphold and deliver justice, including judges, lawyers, administrators, community workers, those in information and communications technology (ICT), and other employees. It is necessary to develop the capabilities of these workers in designing and delivering people-centred legal and justice services, and engaging with non-governmental and private providers. Delivering accessible and inclusive justice services requires the ability to effectively communicate with users, including vulnerable people that often have specific needs. Justice actors should be able to make understandable and accessible the part of the justice system that the potential client is seeking to utilise. Skills to deal with cultural and linguistic differences are here salient, as well as skills to interact with people by listening and adapting to all the graduations of education, economic status, and social conditions to provide useful information and services. A particularly high value is put on the capabilities to create, deliver and assess legal services and justice outputs that respond to the needs of people with disabilities, LGBTQIA+, children and the elderly. Limitations faced by users, in particular when accessing or using digital tools, should also be considered by designers/developers of ICT software and processes. “Human-centric” interfaces tailored to the needs of each priority group and persons should be developed to ensure accessibility to all (OECD, 2021[1]).

Justice sector employees should also be empowered to engage in the creation of policies and interventions, and in facilitating dispute resolution. They should be actively engaged in developing and improving the service value chain of the justice system. It entails holding a joint purpose and vision, which can be promoted by the justice system’s leadership, but it also requires the engagement of workers and users, and the appropriate design to ensure that services continually meet users’ expectations for quality, cost, and timeliness. Finally, there must be continual improvement of services and practices. As such, the teams providing the services should be made aware of their crucial role in delivering justice for people and businesses (OECD, 2021[1]).

In addition, the transition towards digital processes and technologies within the justice sector offers both an opportunity and a necessity for continuous skills development to effectively adapt to new technological processes and tools. Specifically, the availability of data, resulting from the digital representation of a wide array of content, enables institutions to transform their functions in several ways. More accessible and practical data can allow individual stakeholders to excel in an evidence-based and knowledge-driven manner, especially if they are equipped with the necessary know-how and vision regarding the use of data, and their reliability and relevance in the context of their application. In addition, the data-driven design of services offers exceptional potential for holistic and modular solutions to meet the needs of citizens and users. This aligns with the need to transform the managerial approach, requiring a shift towards a cross-sectoral and cross-disciplinary perspective. Interoperability is crucial in this context, as is the integrated design of tools, platforms, and the automated management of items/files/cases.

In consequence, all public servants need to be equipped with the skills that are supportive of data-driven and digital transformation in the justice sector. This includes recognising the potential of digital for transformation; understanding users and their needs; collaborating openly for iterative delivery; trustworthy use of data and technology; and the capacity to understand a data-driven public sector. Justice staff must also acquire new professional competencies to adapt to a wide range of new tools and policy working methods based on new types of “intelligence” and rationalities (e.g. software devices, case management platforms, massive dataset of case laws, digital forensics, and artificial intelligence). It is crucial that organisations ensure their leaders have the skills to oversee digital transformation, are informed and aware of the benefit of going digital and can efficiently communicate the strategy to achieve it (see Strategy and Plan in Chapter 8). This will help set a digital culture within the workforce and the organisation.

In this context, the OECD has identified the skills that justice civil servants need for moving toward a modern people-centred justice sector highlighted in Box 5.1. This can be grouped into skills and competencies related to strategic vision and culture; a governance infrastructure including digital and data skills; a people-centred design and delivery of legal and justice; evidence-based planning, monitoring and evaluation; and empowerment of people.

Box 5.1. Towards an OECD skills framework for a people-centred and modern justice system

Copy link to Box 5.1. Towards an OECD skills framework for a people-centred and modern justice systemBuilding skills, competencies, and professionalism of justice stakeholders is an imperative enabler to move towards a people-centred and modern justice system. Based on the five pillars of the OECD Recommendation on Access to Justice and People-Centred Justice Systems, the OECD has identified the relevant necessary skills and knowledge that justice professionals need to acquire and embed to support the modernisation of the justice system:

A strategic vision and culture for driving the modernisation of the justice sector in a coherent and integrated manner: Justice civil servants must understand the interconnectedness of legal needs with other sectors and be capable of working across sectoral boundaries to implement an integrated agenda in a co-operative manner.

A governance infrastructure that enables people-centred justice: Justice civil servants must be capable of ensuring inclusivity of the justice sector. An inclusive agenda entails guaranteeing access to justice for all by paying specific attention to the needs of vulnerable groups. It also requires fostering dialogue and proactively involving all stakeholders in the design and delivery of justice services. To achieve this, networking skills and collaborative leadership are essential for justice civil servants to work across sectoral siloes and levels of government to ensure horizontal and vertical coherence, and harmonise priorities. Moreover, justice staff must possess abilities for conducting effective project management, impact and risk assessment, and aligning resources with service priorities to ensure successful implementation of initiatives aiming at responding to the needs of people and enhancing access to justice. Furthermore, proficiency in digital and data skills is necessary to facilitate co-operation and innovation across all functions, while clear and accessible communication skills are also vital for raising awareness and fostering transparent and inclusive dialogue with all stakeholders, including marginalised and vulnerable groups.

A people-centred design and delivery of legal and justice services: Justice civil servants must be able to adopt a people-centred approach when designing and delivering legal and justice services. This entails having the ability to design the right delivery model (e.g. direct delivery, commissioning and contracting, partnerships, digital channels), including localised adaptations and mobilising the necessary human and financial resources effectively.

Evidence-based planning, monitoring and evaluation: Justice civil servants must have the ability to design evidence-based policies and services informed by data analysis. This means being able to collect and analyse evidence, measure, and interpret progress. It also involves using people-centred approaches throughout all phases of the policy cycle, in particular, when collecting evidence and conducting evaluations to improve results. Additionally, a comprehensive understanding of legal and justice services, along with knowledge of quality standards, is essential for effective performance measurement, monitoring and evaluation to ensure the delivery of high-quality justice services.

People empowerment to make people-centred justice transformation happen: Justice civil servants, and mostly managers, must possess the essential skills for empowering staff and colleagues and building organisational stewardship. This entails fostering a culture of excellence and responsiveness to individuals' needs, alongside embracing cultural diversity and promoting a continual learning mindset. Furthermore, they must prioritise enhancing openness and inclusion in working environments, valuing diverse perspectives to drive innovation and advance the goals of the organisation.

Source: OECD (forthcoming), OECD Skills Framework for a People-Centred and Modern Justice System.

5.1.1. Organisational processes to support upskilling

Copy link to 5.1.1. Organisational processes to support upskillingImportantly, implementing effective skills strategy in the context of digital transformation and people-centricity in the justice sector implies adapting organisational processes to align with new approaches and to sustain this alignment over time. Justice civil servants do not work in a vacuum but in organisations with their own rules and procedures, and through systems and networks. Each institution may have distinct cultures, legacies and ways of working that distinguish them from others. Taking these characteristics into account, and aligning individual motivation and skills with the right supports and tools, is what creates performance and impact. Organisational processes can be seen as the catalyst in this regard: some speed up or facilitate achieving results, while others may hinder progress in the completion of projects or initiatives.

With regard to effective skills development strategies, organisational processes related to performance management, training and learning may be a key area of focus. For example, this may refer to establishing personalised and participative skills development strategies, overseen by direct managers, and supported by effective positive and negative feedback loops for continuous improvement and alignment with professionals’ needs. But this example also hints at the complexity and trade-offs in getting organisational processes right. In structuring access to learning and development opportunities, organisational processes may incentivise – or discourage – staff from participating in training. A catalogue of self-access training modules on carefully selected topics can be an indicator of good organisational processes, just as a lengthy process of requiring hierarchical authorisation and validation to participate in training may put public servants off. Understanding how organisational processes work (“as it is”) and the scope for improvement (“as it could be”) is thus a key part of building workforce capability.

The focus on processes in the questionnaire distributed to participants attempts to understand these issues, and also feeds into the analytical framework discussed in the next section.

5.2. Skills and competencies for people-centred and modern justice in Portugal

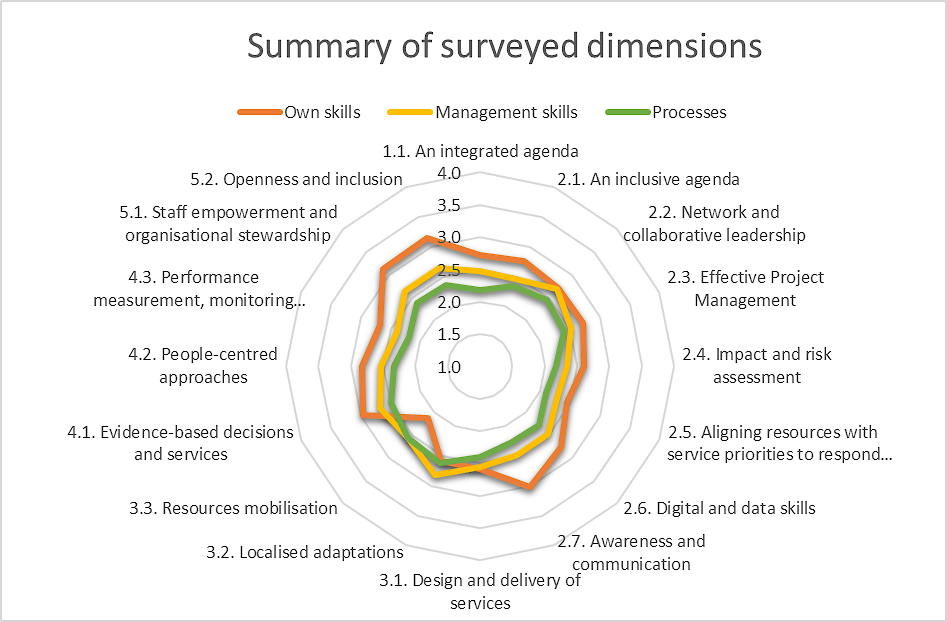

Copy link to 5.2. Skills and competencies for people-centred and modern justice in PortugalThe online survey1 conducted by the OECD aimed at assessing the skills and capabilities of Portuguese justice stakeholders2 based on the justice skills framework above. Based on the summary of survey’s dimensions (see Figure 5.1), the most negatively assessed areas were around services: design and delivery of services, localised adaptations, and resources mobilisation. The most positive concerned people empowerment, and communication and awareness skills. However, positive assessments must be approached cautiously considering the observed tendency for respondents to evaluate their own skills more, and more positively. Equal caution should be applied to negative results, taking into account the absence of actionable data concerning skills related to localised adaptations and resource mobilisation for all groups of respondents (except middle managers). Consequently, it is relevant to complement these results with the graph showing the share of respondents answering a negative option for each skillset. The highest share of respondents providing negative responses concerns the skillsets on vision and culture (40% of responses), inclusive agenda (34%), digital and data skills (34%), design and delivery of services (34%), evidence-based decisions and services (34%) and measuring, monitoring and evaluation (34%).

For vision and culture, and inclusive agenda, there are no significant differences between the responses of the different groups. For digital and skills, ICT professionals have a better perception of their own skills in general, which is not surprising as they are assessing their own area of expertise. The same reasoning can explain the uneven perceptions of respondents on design and delivery of services. Service providers (both in contact with users or not) have a better perception of their competencies than middle managers and ICT professionals. However, the low completion rate for ICT professionals may not properly reflect the perceptions of this group of workers. Again, for the skillset related to evidence-based decisions and services, ICT professionals rated their own skills better than the other respondents. While evidence-based decision and services are highly related to the use of data, this result is also understandable. Finally, all respondents have a low perception of their own skills in measuring, monitoring and evaluation (34%).

Building on these results, it appears that skills development policies should pay close attention to raising the knowledge and ability of justice civil servants in Portugal to consider the justice sector in the broader context of public services. Policies should bear in mind the interconnectedness of legal needs with other sectors (i.e. health, work), while leveraging the interoperability of actors between the different sectors. Raising awareness of the specific needs of vulnerable groups, challenges of inclusivity in general, and developing stakeholders’ skills to adopt an inclusive approach in the design and delivery of justice services and policies should also be a priority. In addition, the survey brought to attention some gaps in designing and delivering services that respond to the needs of different groups of people, in particular at local level.

A strong emphasis should also be put on capacity-building for performance measurement, monitoring and evaluation. The survey reveals a general lack of competencies from all stakeholders to monitor and evaluate their projects, services or policies. However, this finding should be analysed in conjunction with whether effective monitoring and evaluation processes exist or not. The results also indicate that non-ICT professionals self-identified a need for upskilling in competencies related to digital and data skills, as well as evidence-based decisions and services. In a context of constant evolution in terms of digital and data tools and processes, it is not surprising that stakeholders perceive weaknesses in this area. This perception can also be interpreted as a positive sign, indicating the potential motivation of respondents to improve these skills and address any potential gaps linked to digital transition in the justice sector.

Figure 5.1. Overview of survey results

Copy link to Figure 5.1. Overview of survey results

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

In addition, the survey shows that respondents generally rate their own skills and management support at moderate levels across various competency areas and skillsets. For almost all competency areas, respondents evaluated their own skills more positively than management support and organisational processes. However, this does not mean that the survey empirically establishes that managers are generally unsupportive (or unable to provide support). A similar trend was observed in an OECD study on perception of how managers supported innovation in Brazil: results showed that, overall, individuals’ self-perception of their own innovation capabilities is higher than their perception of their manager’s support and their organisation’s readiness. The same findings were observed in the survey conducted in Chile (OECD, 2019[2]).

One of the largest differences between the perception of own skills and the perception of managerial support relates to the skillset of “people empowerment” (including organisational stewardship, openness and inclusion), which is crucial for moving toward a people-centred justice system, in line with the OECD Recommendation on Access to Justice and People-Centred Justice Systems. The “services” skillset – a breakdown of design and delivery, localised adaptation, and resources mobilisation – features an opposite pattern with more positive responses for managerial skills than for own skills. The “services” skillset is also the most negatively assessed area but this may be due to a low completion rate for some competencies. When considering the highest share of negative responses, the primary deficiency lies in the ability of justice civil servants to comprehend and embrace a strategic vision and culture necessary for driving the modernisation of the justice sector in a coherent and integrated manner.

Comparing respondents’ categories, answers from ICT professionals are the lowest even when assessing their own skills. ICT professionals perceive their own skills related to awareness and communication as low, as well as skills that relate to measuring, monitoring, and evaluating performance. On the contrary, the perception of their competencies related to evidence-based decisions and services, and digital and data skills is higher than other categories of respondents. Middle managers and service providers without contact with users assessed managerial support and organisational processes, in general, more positively – contrary to ICT professionals, who were particularly critical regarding supporting processes. More importantly, 58,3% of ICT professionals selected negative option for skillsets that relate to their ability to train employees to ensure the systematic inclusion of stakeholders in the design and implementation of policies and services. The same holds for skillsets that relate to the ability to design policy and services from the point of view of users.

5.2.1. Capacity-building initiatives need to consider the interdependence between technical and managerial functions

Copy link to 5.2.1. Capacity-building initiatives need to consider the interdependence between technical and managerial functionsBuilding skills and capacities for a modern people-centred justice sector requires a strong involvement of managers, both as subjects of upskilling and to drive upskilling policies. This means that while they should themselves undergo training or skills development programmes to enhance their abilities, they also play a key role in developing, implementing, or promoting policies and initiatives aimed at improving the skills of others within the organisation. Therefore, capacity-building initiatives for technical staff are strongly interlinked with managers’ capacity to raise awareness of the existence of training or skills development programmes, and to support technical staff in getting involved in such programmes.

Taking into account the overall perception of Portuguese justice stakeholders, the perception of managerial support to improve skills and competencies is almost always lower than respondents’ perceptions of their own skills. This may mean that employees have a first-hand view of what types of competencies are needed for success in their work area but are constrained in their ability to engage with management to help build those competencies. It is therefore possible that managers are not providing enough information or resources to help enhance skills and capabilities within their organisation, and are not playing the leading role they should in aligning skills with needs and conducting upskilling policies.

As a result, when asked about the presence of a skills development programme, only 28.8% of respondents knew about its existence, with almost 50% not being aware, and 16.6% declaring that it does not exist in their organisation. Four respondents stated that if one such programme exists, it is a one-off and not effective. This impression seemed to be commonly diffused across categories of respondents, with the exception of middle managers themselves.

The gap between managers and technical staff in terms of awareness of skills development programmes is particularly indicative of the inability of managers to promote and communicate about these programmes. Managers’ self-assessment of their own skills related to staff empowerment and organisational stewardship is also interesting to analyse. On average, managers rated 3.03 in a 1-4 scale their capacity to empower staff/colleagues to work across traditional silos and take action, and 2.99 their capacity to empower teams to respond to the needs of clients. Due to limited data, these perceptions cannot be compared with the insights of other workers on management support for empowerment; however, this already reveals that managers have an average perception of their capability which may prompt questioning about the link between self-confidence levels and actual capacity.

When respondents did acknowledge the presence of such programmes, they generally found it very aligned to their needs (59% positive answers), to their level of competence (66%), to their responsibilities (67%), and to the responsibilities of their institution (63%) (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2. Perceptions of current capacity-building programmes

Copy link to Figure 5.2. Perceptions of current capacity-building programmesSource: Author’s own elaboration.

5.2.2. Organisational processes in general can be improved

Copy link to 5.2.2. Organisational processes in general can be improvedThe positive perception of respondents’ skills related to "commitment to promote learning of what works in the legal and justice initiatives” reveals a clear motivation to endorse a learning attitude. Once again, the responses cast light upon the need for proactive management and a development process design where learning is embedded and permanently comprised. The commitment is particularly high among ICT professionals. Motivational preconditions standing at the micro-level are meant to facilitate modernisation and people-centred justice systems.

Yet, in general terms, organisational processes to support stakeholders in developing their skills are generally perceived as shortcomings, as respondents largely reported to either be unaware of supporting processes, or that the processes are in place but do not work well in practice.

For all competency areas, respondents’ perception of supporting organisational processes was lower than their assessment of their own skills and management support. Comparing respondents’ categories, managers (middle managers and other managers) and service providers without contact with users appeared to assess their organisational processes more positively. Managers’ better perception of the way competencies are supported by organisational processes may result from better awareness of the processes in place as their role is strongly interlinked with the implementation of these processes.

Overall, the responses highlight a low capacity in enhancing skills but also reveals the inefficiency of current organisational processes in building an organisational culture. This is particularly visible when looking at the responses related to the comprehensive view of the system, to collect information across different services of the system, and to adapt in a resilient fashion to a fast-changing environment. This evidence points to a weak vision of the interdependence of services and to the limited capacity to see how a specific or local adaptation may facilitate other parts of the system or not.

Organisational processes are particularly important in the context of digitalisation, and strong data governance should be implemented. While prompt human capital to ensure transparent and trustworthy use of data looks available, what is missing is support from management and the development process. This support must go in the direction of situating data collection and use within a broader perspective. It is necessary and instrumental to have a data governance chain across legal and justice services as well as in between the justice system and other sectors of public governance that responds to the standard of quality. Individuals seem to be ready to embark into the new era where the digital tools, and the AI eventually, can be integrated with a human-centred approach and a trustworthy method of data use and reuse ensured at management level and entrenched in development processes.

Developing efficient and agile organisational processes is essential for moving toward a modern people-centred justice sector and aligning resources with needs. This is particularly important in sectors like justice that involve a wide variety of stakeholders. Effective processes to support interoperability and communication should be enhanced. Skillsets associated with the capacity of civil servants to situate themselves in the system where they operate are essential preconditions to setting up a people-centred approach in the justice system. This approach takes the citizens’ perspective as a compass in designing services and promoting an integrated and holistic view of these.

5.2.3. Stakeholders indicate a particular need for capacity-building initiatives related to digital skills and people-centred approaches, as well as networking and leadership

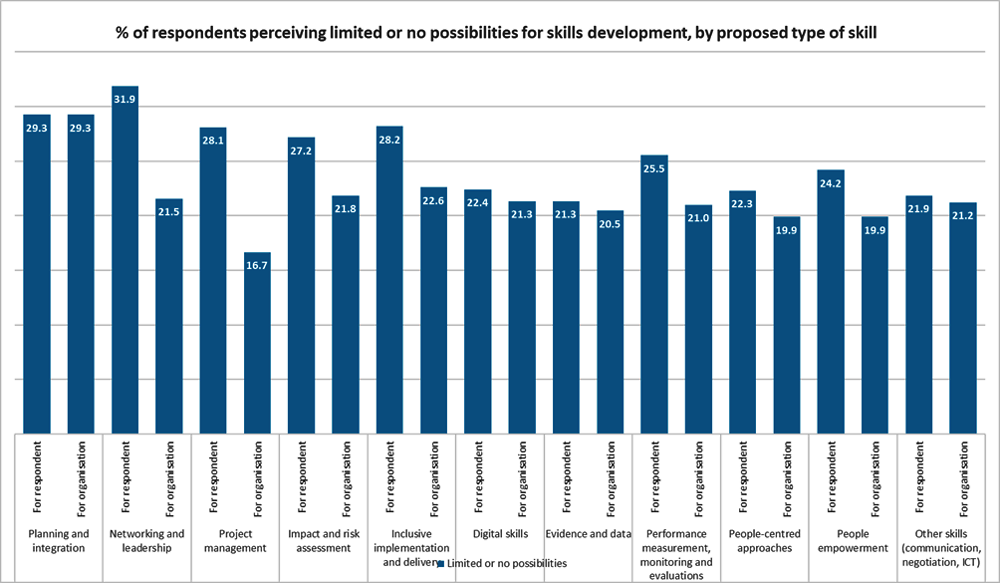

Copy link to 5.2.3. Stakeholders indicate a particular need for capacity-building initiatives related to digital skills and people-centred approaches, as well as networking and leadershipRespondents were asked to rate the opportunities they had to improve in the competencies listed in the questionnaire. On average, 29.4% of respondents thought there were ample possibilities; 31.9% thought there were some possibilities, but that these could be improved; 20.6% thought the possibilities were limited or non-existent; 18% chose to not answer. This means that at least half of respondents believe there is room for improvement in either the quality and/or accessibility of training programmes. Based on the share of respondents indicating limited or no possibilities for personal skills development, the largest gaps emerge around planning and integration (29.3%), networking and leadership (31.9%), project management (28.1%), impact and risk assessment (27.2%), and inclusive implementation and delivery (28.2%) (see Figure 5.3). When asked which areas should be prioritised, the most common answers concerned digital skills (56% of respondents) and people-centred approaches (44%). Some 36.6% of respondents also highlighted a need to prioritise capacity-building related to networking and leadership, and planning integration.

Figure 5.3. Perceptions of skills development opportunities

Copy link to Figure 5.3. Perceptions of skills development opportunities

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Therefore, it appears that while there are some – limited – possibilities for reinforcing digital skills and competencies related to people-centred approaches, respondents’ insights underscore a significant imperative to prioritise these two areas. While this result may primarily stem from a high level of responses highlighting constrained improvement opportunities, it may also underscore the necessity for heightened focus on the quality of existing training programmes. Based on the results, capacity-building initiatives must also focus on enhancing “Networking and leadership” capabilities. Respondents identified this area as the most constrained in terms of self-improvement opportunities and approximately one-third indicated it as a priority for capacity-building.

5.2.4. In-depth assessment across competency areas

Copy link to 5.2.4. In-depth assessment across competency areasVision and culture: An integrated agenda

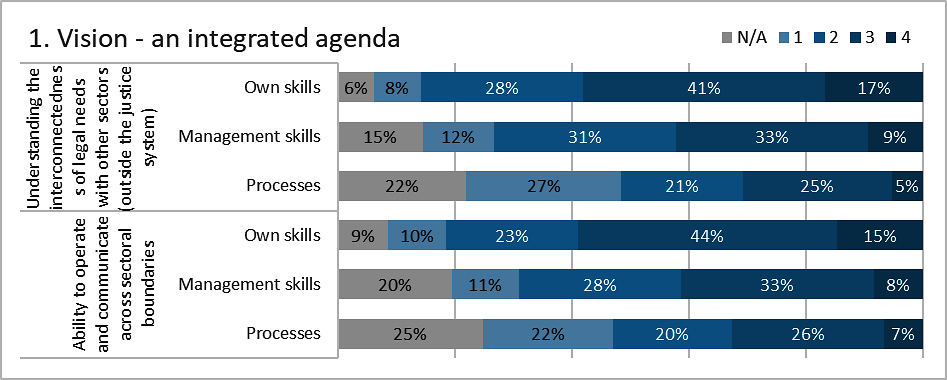

Copy link to Vision and culture: An integrated agendaFor this area, respondents were asked to assess two specific competencies: their ability to understand the interconnectedness of legal needs with other sectors and of operating and communicating across sectoral boundaries (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4. Vision and culture: Share of negative and positive perceptions

Copy link to Figure 5.4. Vision and culture: Share of negative and positive perceptions

Note: Responses rank from most negative (1) to most positive option (4).

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Respondents assessed their own skills in “understanding the interconnectedness of legal needs with other sectors” and “operating across sectoral boundaries” more positively than management and organisational support. For both skills, almost 60% of respondents either consider themselves as experts or use these skills regularly. Respondents have a more negative perception of management support to develop these skills with respectively 42.3% and 40.7% believing that they are either actively developing expertise in these areas or regularly using these skills and enabling others to. Finally, organisational processes were assessed positively by, respectively, 30.4% and 32.7% of respondents. Interestingly, this also might be due to the fact that in the case of management and organisational assessment, respondents more frequently chose not to provide an assessment.

Comparing respondents’ categories, ICT professionals expressed a larger gap in organisational processes related to understanding cross-sectoral connections (60% choosing option 1: there are no organisational processes in place, or option 2: they do not work well in practice); on the contrary, other managers assessed organisational processes related to operating and communicating across sectoral boundaries more positively (with only 30% choosing option 1 or 2).

Comparing mean answers across categories, the largest differences emerged among service providers without contact with users. They appeared to assess the support of their management more positively. This was also true among other managers (including senior managers and decision makers) who appeared to assess the processes of their organisation more positively.

Finally, as mentioned in the general analysis, this skillset received the highest number of negative responses of all three dimensions combined. This reveals a general lack of knowledge, awareness and efforts to support an integrated agenda in a co-operative manner.

Governance

Copy link to Governance5.2.5. An inclusive agenda

Copy link to 5.2.5. An inclusive agendaFor all skills related to fostering an inclusive agenda in the justice sector – ensuring access to justice for all and involving stakeholders in the design and delivery of services, while paying specific attention to the needs of vulnerable groups – respondents assessed their own capacities more positively than the support of their own management or the processes of their organisation. The only exception for which support from management and processes were better rated concerned the “capacity to approach the design of the policy and service agenda from the point of view of the users”.

As mentioned in the justice skills framework, ensuring inclusivity of the justice sector involves guaranteeing access to justice for all, including groups with specific needs. In this regard, respondents were questioned on their awareness of the main issues experienced by children, victims of violence, the elderly, LGBTQIA+ and people with disabilities. Results revealed a particular gap in knowledge of legal and justice issues encountered by LGBTQIA+ (34.3% of negative answers). This was even more pronounced for middle managers (50%).

An inclusive justice sector also requires fostering dialogue and proactively involving all stakeholders in the design and delivery of justice services. In this regard, respondents were particularly negative when assessing their own “ability to systematically include relevant stakeholders/end-users in the design and implementation of justice services and policies” (36.8% of negative responses) and “to systematically design legal services for and with vulnerable people” (33.3% of negative answers). It is worth mentioning that managers perceived more negatively than average their capacity to “include stakeholder feedback for service design and delivery”, “design legal services for and with vulnerable people” and “promoting dialogue through digital media” (50% of negative response from middle managers).

ICT professionals expressed particular deficiencies when assessing fundamental skills to ensure inclusivity in the justice sector. Some 40% of them provided negative responses to several skills evaluated: “fostering inclusive dialogue”, “including stakeholder feedback for service design and delivery”, “designing services for and with vulnerable people”, “promoting dialogue through digital media”. Negative self-assessment was even stronger when it came to assessing their own awareness of issues experienced by vulnerable people (40%) and especially people with disabilities (47%). Perhaps understandably given the nature of their functions, 58.3% of ICT professionals also negatively assessed their own competencies in “training employees to ensure the systematic inclusion of stakeholders in the design and implementation of policies and services”, and “approaching the design of the policy and service agenda from the point of view of users”.

Concerning management support, the two skillsets assessed as particularly deficient were also negatively assessed in terms of own skills: “ability to systematically include relevant stakeholders/end-users in the design and implementation of justice services and policies” (45.9% but less pronounced for service providers without contact with users, 21.4%) and “ability to systematically promote dialogue, including through digital media and social network” (42.2% but less pronounced among middle managers and other managers, with, respectively, 18.8% and 21.4%).

As for organisational processes, the largest gaps also aligned with negative perceptions in terms of own skills and management support, the most negative perceptions being related to the following skills: “ability to foster inclusive dialogue with a variety of stakeholders” (44.7%), “ability to systematically include relevant stakeholders/end-users in the design and implementation of justice services and policies” (45.5%), “awareness of complexity of legal language” (44.8%); “ability to train employees to ensure the systematic inclusion of stakeholders in the design and implementation of policies and services” (41.8%), “ability to systematically promote dialogue, including through digital media and social network” (42.3%).

However, perceptions of organisational processes tend to vary between respondents, with some viewing them more positively and others holding a more negative assessment. While managers and service providers without contact with users tend to assess more positively organisational processes for all skillsets, disparities in responses from other groups of respondents – whether positive or negative – are closely tied to specific groups’ perceptions of their own skills. For example, ICT professionals evaluated organisational processes to support “training employees to ensure the systematic inclusion of stakeholders in the design and implementation of policies and services” more negatively than average respondents (41.8%), while the opposite trend was observed for service providers without contact with users that rated processes to “support fostering inclusive dialogue with a variety of stakeholders” better (only 17.9% of negative responses) and “systematically include relevant stakeholders/end-users in the design and implementation of justice services and policies” (only 21.4%).

5.2.6. Network and collaborative leadership

Copy link to 5.2.6. Network and collaborative leadershipAs highlighted in the justice skill framework above, networking skills and collaborative leadership are necessary to enhance collaboration across justice institutions, level of government and across ministries. Looking at the respondents’ own skills, the largest gaps emerged for the following skillsets: “capacity to network and collaborate across justice institutions and ministries to harmonise priorities and ensure coherence” (34.3% negative responses), “ability to empower staff across ministries and justice agencies to dialogue across sectors and with other stakeholders (inside and outside the justice system)” with 25% of negative answers, and to “work across sectorial boundaries, identifying linkages between policies and services”.

However, respondents were less able to assess their “ability to empower staff across ministries and justice agencies” and their “ability to reach out to other ministries, sectors, levels of government establishing partnerships and dialogue”. This might be due to a perception that these skillsets refer to management and co-ordination abilities that are not normally requested from respondents. While strong leadership from management to empower staff to dialogue across sectoral/institutional siloes and levels of government is primordial, important gaps were observed with 71% of other managers providing negative responses to assess their “ability to work across sectorial boundaries, identifying linkages between policies and services”. Some 35.9% of middle managers also negatively assessed their “capacity to network and collaborate across levels of government to harmonise priorities and ensure vertical coherence”. Finally, 50% of them saw deficiencies in their own ability to “reach out to other ministries, sectors, levels of government establishing partnerships and dialogue”.

ICT professionals assessed particularly negatively their own ability to “network and collaborate across levels of government to harmonise priorities and ensure vertical coherence” (33% of negative answers) and to “work across sectorial boundaries, identifying linkages between policies and services” (44%). This may be due to a low level of interoperability across sectors and policies.

Management support and organisational processes were assessed in roughly the same way across questions, with no significant difference in the distribution of answers among them. The proportion of respondents who had a negative perception for these dimensions was homogeneous around 28.5% for management support and 29.2% for processes. No significant differences emerged across categories of respondents either.

5.2.7. Effective project management

Copy link to 5.2.7. Effective project managementRespondents were asked to assess the perception of their own skills, management support and organisational processes related to effective project management, including designing and implementing projects and using indicators and actions plans. As for other competency areas, respondents felt more comfortable assessing their own competencies than evaluating management support or organisational processes to support these skills. A larger number of respondents chose the “N/A” option for these dimensions.

Respondents were particularly positive about their own ability to effectively design and implement projects, with 61.8% choosing a positive answer, and their ability to use indicators and action plan tools to support decisions and design responsive policies and services, with 59.6% responding positively. They were less confident about their own ability to effectively manage projects (48.3% of positive answers).

Concerning respondents’ skills, the largest gaps emerged for other managers: 50% of them have a negative perception of their own skill when assessing their ability to use indicators and action plan tools to support decisions and design responsive policies and services; 57% of them did so when assessing their own ability to effectively manage projects.

Comparing respondents’ categories in the case of management support, the largest differences emerged for middle managers (with 51% of them negatively assessing management of their institution to support designing and implementing projects) and ICT professionals (with, respectively, 53% and 50% of them having a negative perception of the support received for designing and implementing projects, and for effectively managing projects.

5.2.8. Impact and risk assessment

Copy link to 5.2.8. Impact and risk assessmentFor competencies related to impact and risk assessment – breaking down into awareness of methodologies and framework; and ability to conduct the assessment and to envision and manage risk – again, respondents more frequently chose the “N/A” option when assessing management support and organisational processes, and gave more positive assessments of their own skills.

Some 61.6% of all respondents perceive themselves as well aware of impact and risk assessment frameworks and methodologies. Similarly, 58.2% have a positive perception of their own ability to assess impacts of policy and service proposals, including on access to justice. The same figure was lower for respondents’ ability to envision and manage risk (46.5%).

Comparing own skills across categories of respondents, other managers were comparatively negative, with 41% of negative answers on average. Some 47% of ICT professionals also negatively assessed their own “awareness of impact and risk assessment frameworks and methodologies”.

As for management support, 35% of respondents on average assessed the three competencies in this area as not existing, not regular or not a high priority. In this perspective, service providers with contact with users were particularly negative, with 44% of them on average providing negative answers.

As for organisational processes, the largest gaps were expressed by other managers across all skillsets (on average 49% negative responses), and ICT professionals regarding processes to support awareness of impact assessment framework and methodologies (60% of negative answers), and to support staff’s ability to envision and manage risk (54%).

5.2.9. Aligning resources with service priorities to respond to people’s needs

Copy link to 5.2.9. Aligning resources with service priorities to respond to people’s needsAligning resources with service priorities to respond to the needs of people refers to the following specific skills: aligning human and financial resources for joined-up service delivery with other institutions; aligning budget with people-centred justice policy and service needs; and considering economic, social and environmental impact of policies. Respondents evaluated their own competencies overwhelmingly positively: while 52.8% chose positive options when assessing their capacity to align human resources to deliver services in joined-up ways with other institutions, about 73% of them did so when evaluating their ability to align budget with people-centred justice policy; align financial resources for funding service delivery across levels of government; and consider cross-sectoral policy impacts (see Figure 5.5).

A similar pattern emerged for management support skillsets: 36.8% of respondents had a positive perception of management support to align human resources for joined-up delivery, and 50% positively assessed management support for budget and financial resources alignment, and considering cross-sectoral policy impacts. However, the same trend around assessment of management support and organisational processes holds for this competency area: respondents more frequently chose not to provide an assessment for the two dimensions. For organisational processes, the assessments were less positive, mainly because of a large share of answers being “N/A”.

In all three dimensions, the largest gaps in respondents’ skills emerged for ICT professionals and respondents in other roles, with an average share of negative answers of 50% and 44% for these groups. ICT professionals were also the group that most negatively assessed management support and organisational processes (e.g. 62% of negative answers for aligning human resources for joined-up delivery and for budget alignment with people-centred justice policy).

Figure 5.5. Share of negative responses by respondents’ categories

Copy link to Figure 5.5. Share of negative responses by respondents’ categoriesNote: 2.5a Capacity to align human resources to deliver services in joined up ways with other institutions, 2.5b Ability to align budget with people-centred justice policy and service needs, including for vulnerable groups, 2.5c Capacity to align financial resources to fund service delivery

across multiple organisations/levels of government, 2.5d Ability to consider economic, social and environmental policy issues when evaluating costs and benefits of a policy.

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

5.2.10. Digital and data skills

Copy link to 5.2.10. Digital and data skillsOne of the biggest challenges identified in the development of digital transition projects in the justice sector in Portugal are internal teams with few resources or capabilities for managing projects whose development has been contracted out to external teams. In order to ensure the operationalisation and evolution of those projects by the organisations themselves within the justice sector, Portugal launched LAB Justiça – a programme to strengthen strategic management digital and leadership skills (see Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. Portugal: LAB Justiça

Copy link to Box 5.2. Portugal: LAB JustiçaLAB Justice is a programme that aims to strengthen the skills of justice leaders and project managers with a focus on management and operationalisation of change. Launched in October 2022 in Lisbon, the programme is co-ordinated by the Justice Institute for Financial and Equipments Management (IGFEJ) and developed in partnership with Nova SBE and the Instituto Superior de Economia e Management (ISEG). LAB Justiça is part of the Skills Programme for Innovation in Justice – Build capacity to innovate (“Capacitar para Innovar”) – integrated as part of the GovTech Justiça and financed by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), which foresees an investment of EUR 4.9 million for the Skills Center for Innovation and Digital Transformation (Justice Hub).

The programme focuses on three strategic pillars: strategic management, digital transition and leadership in a changing context. It is based on a “learning and applying” methodology, with a strong emphasis on practical exercises, including workshops and collaborative working groups. In particular, participants are required to develop innovation projects applicable to the Ministry of Justice. Projects must be based on an existing project from the Justice Action Plan, or a new project corresponding to one of the strategic pillars of the plan.

The first edition of the programme targeted project leaders and managers and involved 100 participants from 18 bodies and entities in the area of justice. The second edition integrates 50 new staff from government agencies and institutions in the field of justice. It takes place in Porto in partnership with the Porto Business School. In addition, a new 60-hour specialised training course, called Deep Dive, is planned for the participants of the first edition to deepen the topics covered in the first edition.

Source: Government of Portugal (2023[3]), Lab Justiça, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/LabJustica_brochura.pdf.

In addition to being new legislation for the judicial system to adapt to, the above-mentioned EU Digital Services Act (DSA) includes instruments for complaint resolution in Articles 20 and 21 managed by the private sector. The internal complaint-handling system, facilitated for users as per Article 20, and the out-of-court dispute settlement under Article 21 are decentralised ways to ensure access to justice for citizens, focusing on resolving their demands. They can also serve as a source of learning for the judiciary to ensure better efficiency in judicial processes through the best practices of the private sector.

In terms of self-assessment of skills, a preliminary major competence for driving digital transformation of the justice sector is the “ability to understand the potential of digital transformation”. All respondents had a relatively positive perception of their ability to do so with 72.6% positive opinion. However, middle managers differed from the rest of respondents with 50% of them choosing a negative option, while their role in driving modernisation is essential. Again, management support and processes were assessed less positively, with 50% and 40% of respondents respectively choosing positive options for this dimension.

Respondents were also asked about their “ability to understand users and their needs”. Answers were more homogeneous across dimensions with 28.5% identifying their own skills as deficient, compared to 33.8% for management support and 35% for organisational processes.

A specific area of enquiry for the survey under digital skills was the ability to collaborate for iterative delivery:

1. For these skillsets as for others across the survey, again, respondents provided more responses and evaluated their own competences more positively than management support and organisational processes. Around a half of respondents chose a positive option when assessing their own skills, with a higher rate of positive responses for the “ability to understand different phases of delivery” (61.8%).

2. Surprisingly, the largest gaps emerged for ICT professionals around the “ability to understand open-source code and the community-based processes that support them” (46% negative answers), and “knowledge of common standards, components and patterns” and when to use them (50% negative answers).

3. Management support received more lukewarm assessments, with the share of negative answers being equal or superior to the share of positive ones. An exception to this was the mentioned “ability to understand different phases of delivery”, for which 42.6% had a positive perception of management support.

4. As for organisational process, in this group of skillsets an average of 33.7% of all respondents chose “N/A”, and 36.7% chose a negative response (no processes or processes that do not work well in practice).

5. Comparing categories, again middle managers had more negative impressions than other categories, with 50% choosing negative options.

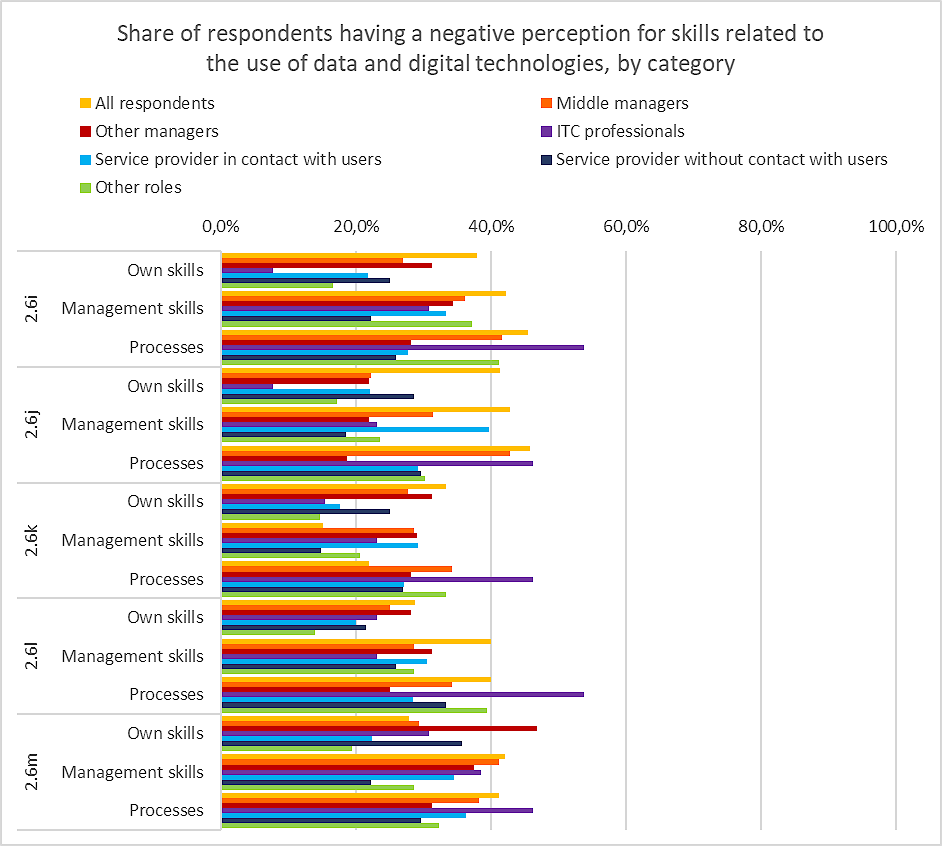

The survey also covered skillsets related to the capacity to be trustworthy in the use of data and digital technologies. Respondents were relatively positive about their own competencies, with over 50% choosing positive options for their “ability to understand one’s own responsibility in the workplace around information security and data handling or processing including the legislations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)” (52.9%), and their “capacity to be confident in terms of digital security and clear about password policies” (55.9%). For skillsets related to protection of privacy and ethical dimensions in handling data and using digital about two-thirds of respondents gave a positive assessment of their own skills. The result was roughly the same for respondents’ self-assessment of their “ability to ensure that contracts with third-party suppliers are consistent with the digital government agenda”.

Responses were more nuanced around management support, with roughly equal proportions of answers divided between positive (37.2%) and negative (37.7%) assessments, coupled with a homogeneous share of intentional non-answers (N/A, on average 24.6%). Less divided perceptions emerged from organisational processes, with about 40% of respondents on average choosing a negative option, 31.1% choosing N/As, and 28% having a positive perception.

Comparing categories, middle managers provided comparatively more negative perception, with 50% of them selecting negative options for all dimensions and skillsets. Similarly, and surprisingly, ICT professionals were slightly more negative than average, with 35.7% choosing negative options for all dimensions and skillsets (see Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6. Share of negative responses by respondents’ categories

Copy link to Figure 5.6. Share of negative responses by respondents’ categories

Note: 2.6i. Ability to understand one’s own responsibility in the workplace around information security and data handling or processing, 2.6j. Capacity to be confident in terms of digital security and clear about password policies, 2.6k. Ability to understand one’s legal requirements as individuals in terms of handling of data to protect the privacy of citizens, 2.6l. Ability to be comfortable considering the ethical dimensions associated with the use of digital technologies or data, 2.6m. Ability to ensure that contracts with third-party suppliers are consistent with the digital government agenda.

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Another group of skillsets assessed by the survey is the capacity to understand a data-driven public sector. This skillset is a breakdown of multiple competencies such as understanding who is responsible for the data agenda, the steps to establish a data-driven public sector, the arrangements for accessing and sharing data, and the legal and ethical obligations related to data and the interoperability of data.

Overall, answers to this group of skillsets were very homogeneous. Given the length of the section, it is possible this was a sign of fatigue for respondents, with consequent straight lining in the answer matrix provided. The observed trend of evaluating own skills more and more positively persisted. On average, 62.7% of respondents assessed their own competencies positively, with a minimum of 55.8% for “the ability to recognise opportunities for how interoperability and access to transactional data can support the better design of services” and a maximum of 66.7% for “the ability to understand the priority, roadmap and strategy for taking the steps to establish a data-driven public sector”.

The differences among answers in assessing management support were even less pronounced, and, as for the previous group of skillsets, less positive than those related to own skills: between 39.4% and 45.2% of respondents chose positive answers, while between 32.1% and 36% chose negative ones. As for management support, responses were roughly equally split between positive options (on average 32.2%), negative options (on average 36.9%) and N/As (on average 30.9%). Comparing categories, again 50% of middle managers were relatively more negative for all dimensions of most competencies related to the skill “capacity to understand a data-driven public sector”.

Additional competencies related to this skillset can be divided in two groups of skills:

1. Capacities related to the understanding of a digital system and fast-changing environment, diplomacy skills and evidence-based responses to needs3. For these, an average of 47.7% of respondents chose positive options, and 32.6% negative options, with a positive maximum in the case of “capacity to react to a fast-changing environment”, and the largest skills gap emerging in “capacity to see the full scope of a system and understand how different moving parts fit together, spot patterns and trends, look to the future". Comparing skill gaps across categories of respondents, service providers in contact with users were slightly less negative than average when it came to collecting information and providing evidence-based responses to needs (only 15.9% negative responses).

2. Regarding capacities related to ethics, security and reliable use of data and technology; and communication skills to champion the benefits of digital and enable decentralised decision making4, these were evaluated in an overwhelmingly positive way, with 78.7% of respondents on average choosing a positive option. Some 87.9% of respondents assessed positively their own ability to use digital means (social networking sites [SNS], websites etc.) to interact with users in an ethical manner. Comparing gaps across respondents’ categories, middle managers emerged as perceiving to have larger than average skill gaps in all skillsets mentioned except the “ability to ensure reliable use of data and technology”.

Looking at management support, the second group of skillsets above showed a lower share of intentional non-answers (20.6% on average) compared to other skillsets related to digital and data (29.6% on average). No particularly large difference emerged when comparing answers among categories.

As for processes, answers were roughly divided in equal parts between intentional non-answers, positive, and negative answers. At the same time, some skillsets presented considerable differences, with some larger gaps in skillsets of “diplomacy skills”, “capacity to react to a fast changing-environment”, to “actively champion the benefits of digital government” and to “enable a decentralised decision making” (all showing about 40% negative assessments). On the contrary, digital skills to make use of a complex and fast-evolving information landscape showed a larger share of positive answers (42.4%).

Considering that some respondents were ICT professionals, the following section of the survey was tailored to the characteristics of respondents. Some skills were only asked of respondents identifying themselves as digital professionals (knowledge and understanding of user-centred design, product and delivery, service ownership, data and digital technologies), or of respondents declaring they were not digital professionals (knowledge and understanding of law, policy, and subject matter, strategy and governance, commissioning and procurement, human resources, operations and customer service, digital/ICT).

5.2.11. Awareness and communication

Copy link to 5.2.11. Awareness and communicationPortugal is implementing projects to facilitate communication between justice actors and the general public (see Box 5.3).

Box 5.3. Portugal: Simplifying communication with service users

Copy link to Box 5.3. Portugal: Simplifying communication with service usersLabX’s initiatives to simplify language for service design

Copy link to LabX’s initiatives to simplify language for service designLabX is the Portuguese Centre for Innovation in the Public Sector, integrated to the Administrative Modernisation Agency (AMA). Its mission is to contribute to the innovation ecosystem in the Portuguese public administration and provide tools to support the design of public services with a people-centred purpose.

Copy link to <strong>LabX</strong><strong> is the Portuguese Centre for Innovation in the Public Sector, integrated to the Administrative Modernisation Agency (AMA). Its </strong><strong>mission is to contribute to the innovation ecosystem in the Portuguese public administration and provide tools to support the design</strong><strong> of public services </strong><strong>with a people-centred purpose.</strong>The Centre has developed several initiatives in recent years. This includes a methodology to help public sector organisations to draft in plain language when communicating with service users. The methodology encompasses capacity-building workshops – hands-on sessions that aim to support service delivery and communication teams to diagnose and review documents and written content available to users. LabX also provides a step-by-step guideline to help public officials apply the methodology. These initiatives have important outcomes, including enhancing efficiency in service delivery, and increasing levels of user awareness and uptake of public services.

Simplex +’s initiative Understanding justice (“Compreender a justiça”)

Simplex + is a programme aimed at legislative and administrative simplification, and the modernisation of public services.

Within the “simpler communication” component of the programme, the Ministry of Justice led the initiative Understanding Justice. The initiative aimed to address the lack of clarity that complex language and legislative texts may entail to justice users. The simplification of texts also included court summons and legal notifications to citizens.

Source: Government of Portugal (2024[4]), Language simplification workshops, https://labx.gov.pt/projetos-posts/oficinas-de-simplificacao-da-linguagem/; Government of Portugal (2016[5]), Simplex+ , https://simplex.gov.pt/simplexmais/app/files/332c67abd4420decd48c1c6429667a35.pdf.

Despite the country’s initiatives, 40% of respondents considered “raising awareness and communicating in plain language (especially reaching out to marginalised and vulnerable groups)” as deficient. They were much more positive on management support and organisational processes, with only 16.1% and 22.6% of answers being negative. Comparing respondents’ categories, middle management and ICT respondents emerged as more critical than average, with 44.1% and 58.3% providing a negative assessment for all dimensions (see Figure 5.7). With organisational processes and management support scoring quite high (in comparison to other skillsets) and staff perception of their own skills being relatively negative, capacity-building initiatives to raise awareness and communication may be an example of ‘low-hanging fruit’, assuming that targeted support in building staff competencies will in turn be supported by the organisational environment.

Figure 5.7. Awareness and communication: Share of negative and positive perceptions

Copy link to Figure 5.7. Awareness and communication: Share of negative and positive perceptionsNote: Responses rank from most negative (1) to most positive option (4)

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Services

Copy link to ServicesThe services skillset refers to several competencies required for adopting a people-centred approach when designing and delivering legal and justice services. As mentioned in the framework, it is a breakdown of the ability to design the right delivery model (e.g. direct delivery, commissioning and contracting, partnerships, digital channels), tailor them to local contexts and mobilise necessary human and financial resources effectively.

The observed trend of evaluating own skills more often and more positively repeats for this group of skillsets as well. Respondents were overwhelmingly positive in assessing their own skills for all skillsets, with the exception of their “ability to contract required services and goods”. In this case, 45.2% of respondents chose a negative option. Some 75% of managers positively assessed their own skills for “contracting required services and goods”, “co-ordinating policy delivery at local level including by interplaying with different communities and leaders in different locations”, and “designing funding tools and accountability framework for delivery partnerships to respond to local needs” (see Figure 5.8).

When it came to management support, the “ability to contract required services and goods” received a less positive assessment from managers, with 21.9% of them having a negative perception of management support. Excluding this, answers were prevalently positive (56.3% of positive responses on average) or N/As (27.3% on average).

A similar pattern emerged for organisational processes, excluding the “ability to contract required services and goods” (21.9% negative responses, and 37.5% intentional non-answer), 46.1% of respondents found them adequate, and 32.8% could not provide an answer.

Figure 5.8. Services: Share of negative and positive perceptions

Copy link to Figure 5.8. Services: Share of negative and positive perceptionsNote: 3.1a. Ability to plan and deliver legal and justice services to respond to the needs of different groups of people and stakeholders, 3.1b. Ability to contract required services and goods, 3.2a Ability to co-ordinate policy delivery at local level, 3.2b Capacity to interplay with different communities and leaders in different locations, 3.3. Ability to design funding tools and accountability frameworks for delivery partnerships to respond to local needs, including at the local level.

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

5.2.12. Design and delivery of services

Copy link to 5.2.12. Design and delivery of servicesThis skillset questioned justice civil servants’ ability to design evidence-based policies and services informed by data analysis. It involved assessing their capacity to plan and deliver evidence-based services, using data interpretation to inform decisions and create public value, and commit to promoting learning of what works in legal and justice initiatives.

As per other competency areas, respondents evaluated their own skills more often and more positively than management support or organisational processes. For this group of skillsets, respondents were overall very positive: on average, 72.9% of them responded positively about their own capacity to plan and deliver evidence-based services, to understand data interpretation and use it to inform decisions, design and run services, and create public value inside and outside government. They were also positive about their commitment to promote learning of what works in legal and justice initiatives. They were more negative on their ability to collect, manage, analyse and interpret relevant data (43.8% positive answers, 28.1% negative answers).

The same pattern emerged for management support and organisational processes, with a relatively low number of respondents identifying gaps in the dimensions mentioned above except for the “ability to collect, manage, analyse and interpret relevant data”, with 38.7% and 34.2%, respectively, negative responses.

5.2.13. Localised adaptations

Copy link to 5.2.13. Localised adaptationsThe same trends across dimensions described above were observed for this group of skillsets.

When assessing their own skills, respondents perceived the largest gaps in “knowledge of full spectrum of legal and justice services, including the non-litigious means of dispute resolution” (25% negative answers), orientation towards people-centred service (24.8%), and ability to interpret data and provide operative policy advice (24.4%). Comparing categories of respondents, ICT professionals were the most negative group, with 58.3% of them providing a negative assessment across all dimensions and skillsets.

As for management support, respondents were less confident in assessing support for “knowledge of the national and transnational standards of quality of justice” and “orientation toward people-centred service”, with 33.9% of respondents indicating N/A for both skillsets. Again, the largest gaps emerged for “knowledge of full spectrum of legal and justice services, including the non-litigious means of dispute resolution” (37.9% negative answers) and “ability to interpret data and provide operative policy advice” (35.8% negative answers). Comparing categories of respondents, other managers appeared to assess more positively management support under “adaptive leadership able to understand and apply people-centred and evidence-based approaches”.

Regarding organisational processes, about 42% of respondents chose “N/A” for the following skillsets: “knowledge of full spectrum of legal and justice services”, “knowledge of the national and transnational standards of quality of justice”, and “orientation towards people-centred service”. A relatively homogenous share of 32.3% of respondents found all skillsets as deficient.

Measuring, monitoring and evaluating performance

Copy link to Measuring, monitoring and evaluating performanceThe same trends across dimensions described above were observed for this group of skillsets. In assessing their own skills, on average, 52% of respondents gave positive answers. The largest gap was perceived in respondents’ own “ability to measure performance of projects/initiatives”, with 26% negative answers. The share of negative answers for “conducting evaluations to improve policy and service results” and “ability to plan, measure, and interpret progress” was not significantly different (25% and 23.7%).

Looking at management support, “conduct evaluations to improve policy and service results” emerged as the largest gap, with 44% of respondents choosing a negative option. As for organisational processes, a relatively homogeneous one-third of respondents (36.9% of respondents) identified these skillsets as deficient.

Comparing categories, as above again, the gaps in these competencies seemed to be felt more acutely among middle managers (44.4% providing negative answers across all dimensions and skillsets) and ICT professionals (58.3% of whom provided negative assessments).

People empowerment

Copy link to People empowerment5.2.14. Staff empowerment and organisational stewardship

Copy link to 5.2.14. Staff empowerment and organisational stewardshipRespondents were asked to assess their own skills, management support and organisational processes related to the following competences: orientation towards excellence; capacity to think outside the box; capacity to empower staff/colleagues to work across traditional silos and take action; capacity to empower teams to respond to the needs of clients; embracing cultural diversity; and adopting a learning mindset.

The same trends across dimensions described above were observed for this group of skillsets. When assessing their own skills, managers found themselves to be more deficient, with 39.7% choosing a negative option in assessing their own “capacity to empower staff/colleagues to work across traditional silos and take action”, and 41.7% doing so in evaluating their own capacity to “empower teams to respond to the needs of clients”. A similarly large gap emerged also for “embracing cultural diversity”, with 41.7% of respondents providing negative answers (see Figure 5.9).

When considering management support, a homogenous one-third of respondents across all skillsets (an average of 36.5%) considered them inadequate, with the largest gap emerging for “capacity to think outside the box” (39.2% negative answers). Similar figures emerged for organisational processes, with an average of 35.7% of respondents providing negative answers across all skillsets.

Figure 5.9. People empowerment: Share of negative and positive responses

Copy link to Figure 5.9. People empowerment: Share of negative and positive responsesNote: 5.1a Orientation towards excellence, 5.1b Capacity to think outside the box, 5.1c Capacity to empower staff/colleagues to work across traditional silos and take action, 5.1d Capacity to empower teams to respond to needs of clients, embracing cultural diversity, and adopting a learning mindset.

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

5.2.15. Openness and inclusion

Copy link to 5.2.15. Openness and inclusionThe assessment of skills related to openness and inclusion involved two questions for all respondents (embracing cultural diversity, adopting a learning mindset) and two others for managers only (ability to adapt management to cultural diversity, ability to promote open, inclusive working environments). The same trends across dimensions described above were observed for this group of skillsets.

The “ability to adapt management to cultural diversity” counts the highest share of negative responses, with 46.5% providing negative answers when assessing their own skills and 35.7% when assessing management support. The perception of management support to “promote open, inclusive working environments” was also mostly negative (35.3%). Considering organisational processes, across all skillset responses there was a homogeneous split, with N/As (32.3% on average), negative answers (33.7% on average) and positive answers (34% on average).

References

[4] Government of Portugal (2024), Language simplification workshops, https://labx.gov.pt/projetos-posts/oficinas-de-simplificacao-da-linguagem/.

[3] Government of Portugal (2023), Lab Justiça, https://govtech.justica.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/LabJustica_brochura.pdf.

[5] Government of Portugal (2016), Simplex+, https://simplex.gov.pt/simplexmais/app/files/332c67abd4420decd48c1c6429667a35.pdf.

[1] OECD (2021), OECD Framework and Good Practice Principles for People-Centred Justice, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cdc3bde7-en.

[2] OECD (2019), Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets 2019: An Assessment of Where OECD Countries Stand.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. For each competence area, respondents were prompted to assess three dimensions using a 1-4 scale: Their own competence: What is the level of your competence in this area? 1: I know very little about this; 2: I have a general awareness of this and do it sometimes; 3: I do this regularly; or 4: I consider myself an expert in this; or N/A; The management support received: To what extent does the management of your institution support these competences? (1: Not at all/ they are not aware; 2: They do this sometimes but not a high priority; 3: They do this regularly and enable others to; 4: They are actively developing expertise in this area (e.g. by hiring specialists or training); or N/A; Organisational processes in place within their organisation or department: Are there processes in public administration to support these skills? 1: No, not that I am aware of; 2: Some, but they do not work well in practice; 3: Yes, there are well-used processes, but there is room for improvement; 4: Yes, they function well; or N/A.

In the following sections, “negative” perception/response will refer to respondents choosing option 1 or 2, while “positive” perception/response will refer to respondents choosing option 3 or 4.

← 2. Some 56.5% of respondents belonged to three organisations: the Directorate-General for Justice Administration (28.9%), the Judicial Police (14.2%), and the National Institute of Legal and Forensic Medicine (13.4%). Most respondents hold technical functions (72.5%), while 20.7% hold only managerial functions. Most respondents are in contact with service users (83.8%) and citizens (67.9%) with almost half of them identifying as service providers (47.7%), and 16.6% as middle manager. There was a clear prevalence of people aged 45-to-64-years-old (73.7%), with 496 people serving as a civil servant for more than 11 years – and 288 for more than 20 years. This tells a story about both the embeddedness of the work routines – inverse proportionality to the critical stance toward these routines – and about the potential for the development of the professionalism of these people who may have a demand for upskilling.

← 3. Respondents were asked about the following skills: capacity to see the full scope of a system; to collect information and provide evidence-based responses to needs; diplomacy skills; capacity to react to a fast-changing environment and digital skills to make use of a complex and fast-evolving information landscape.

← 4. Respondents were asked about the following skills: ability to ensure reliable use of data and technology; to use digital means to interact in an ethical manner; to anticipate and mitigate privacy, security and ethical risks; to communicate a clear vision of the role of digital; to actively champion the benefits of digital government; and to enable a decentralised decision-making.