Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) has made significant headway on its development path over the past three decades. The country’s sustained economic growth has been led by booming commodity exports and substantial inflows of external financing. Many Laotians have seen significant improvements in their well-being. Poverty has declined as household income has increased, and many important development goals in education and health have been achieved. In the face of macroeconomic challenges, a shift from commodity-driven growth to a more inclusive prosperity paradigm that emphasises the creation of broad-based opportunities, human capital development and green sustainability can unlock Lao PDR’s future development. This overview summarises the report and presents priorities for overcoming the country’s current fiscal constraints and finding ways to fund this shift. Recommendations address strengthening Lao PDR’s sustainable finance, revenue generation and tax reform, investment promotion, and data capacity in order to tap into green finance mechanisms.

Multi-dimensional Review of Lao PDR

1. Overview: Pathways for financing the sustainable development of Lao PDR

Abstract

Lao PDR is striving to realise an ambitious development agenda that is centred on human capital, well-being and safeguarding the country’s tremendous natural resources. These objectives are outlined in the 9th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan (2021-2025). Lao PDR’s ambitions build on a very successful development path that has seen rapid economic growth and steady social progress since the 1990s.

Today, Lao PDR faces a challenging fiscal and debt situation and pressure to update its development model towards a more balanced and sustainable development pathway. Public revenues from economic activity are low, while debt service is poised to increase further. In order to realise its ambitions and enable the necessary investments for development given this situation, Lao PDR has developed a Financing Strategy for the 9th National Socio-Economic Development Plan (NSEDP).

This Multi-dimensional Country Review (MDCR) is being undertaken in order to support Lao PDR in financing its sustainable development and achieving its ambitions. It builds on joint workshops and policy discussions held in Vientiane between April and December 2023, as well as a review process with the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) Development Centre’s Mutual Learning Group in February 2024.

The report’s development diagnostic (Chapter 2) builds on the MDCR methodology, which combines participatory visioning and foresight with traditional development analytics, including the OECD Well-being Framework, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), benchmarking and comparison of Lao PDR’s results and experiences with those of other countries. For each MDCR, a set of comparator countries is designed to include regional peers, countries from other regions with similar structural characteristics (for example, being landlocked, level of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, and the structure of the economy) and OECD member countries. Depending on data availability, Lao PDR is compared with a set of benchmark countries (Albania, Plurinational State of Bolivia [hereafter “Bolivia”], Botswana, Cambodia, Colombia, Czechia, Ghana, Korea, Paraguay, Thailand and Viet Nam) as well as the average for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Member States throughout this report.

Building on this diagnostic, this MDCR provides priorities and recommendations for financing Lao PDR’s sustainable development. Chapter 3, “Opportunities and challenges in Lao PDR’s sustainable development financing landscape”, reviews Lao PDR’s financing trajectory and provides recommendations for ensuring sustainable flows of financing; Chapter 4, “Generating sustainable fiscal revenue”, provides recommendations for a radical overhaul of Lao PDR’s tax system and how the country translates investments and economic revenue into resources for development; Chapter 5, “Stimulating sustainable investment in Lao PDR”, identifies actions for attracting the type of investment that can underpin sustainable and balanced growth; and Chapter 6, “Strengthening environment statistics in order to support sustainable development”, sets out a road map for building green data and statistics as a core capacity for mobilising future green finance flows.

This overview chapter begins with a brief history of Lao PDR’s development and a summary of the development diagnostic and priorities, including a future vision and the Lao PDR government’s development strategy. It then presents recommendations for improving sustainable development finance, which are drawn from the subsequent four thematic chapters. The overview concludes with a focus on implementation.

A brief history of Lao PDR’s development

Lao PDR has a proud history, shaped by its strategic location at the centre of mainland Southeast Asia and along the Mekong River The country dates back to the emergence of the Kingdom of Lan Xang (literally “million elephants”) in the 14th century, which marked a significant era of power and cultural influence (Pholsena, 2004[1]). Following centuries of both peaceful and violent evolution in interplay with its neighbours and foreign powers, the modern-day Lao PDR was established in 1975. The Mekong River, which flows through Lao PDR, serves as a connecting link to Thailand in the west and Cambodia in the south. It has remained a vital source of livelihood and economic activity throughout Lao PDR’s history.

Lao PDR initially applied a centrally planned economic system according to communist doctrine. Most economic activity was nationalised, prices were administratively determined and trade between provinces was highly regulated. The emphasis was primarily on modernising production technology, and on attaining self-sufficiency through food and rural reforms centred on the collectivisation of agriculture (OECD, 2017[2]; Fujita, 2006[3]). The results were disappointing and Lao PDR found itself facing shortages and high inflation.

In the mid-1980s, the government began to shift towards market-oriented reforms known as the "New Economic Mechanism" (NEM). The government of Lao PDR began opening up the economy, liberalising domestic and foreign trade, encouraging foreign investment, and initiating policies to promote private enterprise. This period marked a turning point in Lao PDR’s economic strategy, as it brought dynamism to the economy and set the stage for Lao PDR’s subsequent development success and integration with the global economy.

The 1990s were marked by rapid regional integration and trade expansion. Lao PDR joined the Greater Mekong Subregion in 1992 and the ASEAN in 1997 (ASEAN, 2024[4]). The strengthening of regional trade institutions stimulated the swift integration and expansion of trade within regional markets. Between 1990 and 1998, trade grew from 36% to 84% of Lao PDR’s GDP (World Bank, 2024[5]). Endowed with abundant natural resources, Lao PDR’s export growth was led by agricultural and forestry products, and subsequently more and more by hydropower and minerals.

In the first two decades of the 2000s, Lao PDR’s economy was one of the fastest growing in the world, with an average annual growth rate of 7.1% (World Bank, 2024[5]) (Figure 1.1). The country reached middle-income status in 2011 and joined the World Trade Organization in 2013. Booming investment was an important driver of Lao PDR’s economic success, spurring large-scale infrastructure projects and a continued push into the mining and energy sectors.

Between 2006 and 2017, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows grew almost tenfold, from USD 187.4 million (United States dollars) to USD 1.69 billion. Investment in Lao PDR’s Special Economic Zones (SEZs) reached a cumulative USD 7.6 billion in 2021 (Dalavong, 2021[6]; SEZO, 2023[7]). Exports have grown almost fourfold since 2010, reaching USD 9.2 billion in 2021. Exports of ores and metals including gold, silver, copper and iron boomed as well, followed by agriculture- and forestry-based products such as cassava, rubber, paper and pulp.

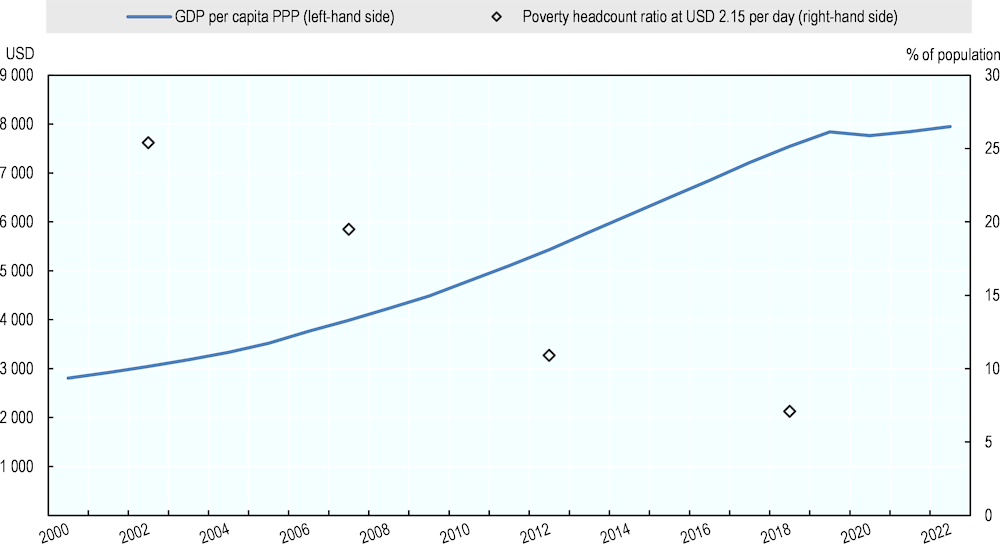

Figure 1.1. Lao PDR experienced significant growth and poverty reduction between 2000 and 2020

GDP per capita, adjusted by purchasing power parity (constant 2017 international dollars) and poverty headcount ratio at USD 2.15 per day (2017), % of population

Source: (World Bank, 2024[5]), World Development Indicators (database) (accessed on 15 November 2023).

Adding to its success, Lao PDR was able to translate its economic growth into many important development gains in relation to household income, poverty reduction, education and health. Extreme poverty fell from 25.4% to 7.1% between 2002 and 2018 (Figure 1.1). Lao PDR has made steady progress in expanding access to education and achieving nearly universal primary education, making primary school in Lao PDR compulsory and free through the fifth grade. Progress in health outcomes has been equally significant. Maternal mortality dropped from 284 deaths per 100 000 births in 2010 to 126 deaths per 100 000 births in 2020, and the mortality rate for children aged under 5 years improved from 61 deaths per 1 000 births in 2010 to 44 deaths per 1 000 births in 2020 (World Bank, 2024[5]).

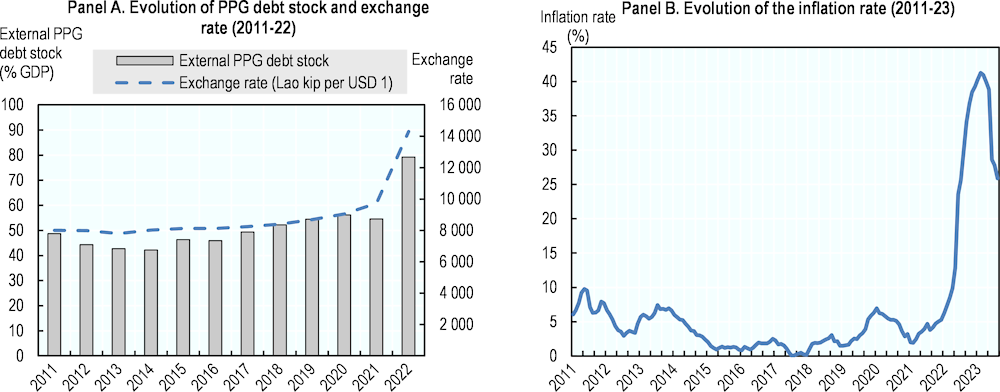

After three successful decades, Lao PDR now faces a challenging economic situation. Triggered by the COVID‑19 pandemic’s sudden halt to the global economy and a drop in prices for many of Lao PDR’s exports, the country’s impressive growth streak has come to an end. While economic growth did not turn negative in 2020, it has remained between 2% and 3% since then, a visible deviation from the previous trend. Public debt has reached unsustainable levels and the burden of servicing existing debt is high (IMF, 2023[8]). High inflation and currency depreciation have put pressure on incomes (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Macroeconomic imbalances materialised in 2022, notably because of a depreciation of the Lao kip and rapid inflation

Note: In Panel A, data for 2022 are preliminary. PPG stands for publicly guaranteed debt.

Source: (Government of Lao PDR, 2022[9]), Public and Publicly Guaranteed Debt Bulletin of Lao PDR, https://www.mof.gov.la/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2022-Public-and-Publicly-Guaranteed-Debt-Bulletin-of-Lao-PDR-Final.pdf; (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2023[10]), Lao Statistical Information Service (database) https://www.https://laosis.lsb.gov.la; and (World Bank, 2024[5]), World Development Indicators (database) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.DOD.DPPG.CD?end=2021&locations=LA&start=2010 (accessed on 23 October 2023).

Elements of the current difficulties were apparent during previous years of high growth and investment. Beyond the challenges of the COVID‑19 pandemic and changing global macroeconomic conditions, the decrease in growth is also the result of a rapid build-up of government debt throughout the 2010s, fuelled by large current account deficits and a high share of external finance in investment projects without the generation of commensurate revenues or the existence of sufficient foreign exchange reserves to pay for debt service. Although the country reduced its external borrowing in recent years, it still faced growing difficulties in meeting its debt service obligations. As commonly seen in countries facing debt issues, the financial strain ultimately caused the local currency (the Lao kip) to depreciate by more than 50% against the United States dollar in 2022. Largely because of the Lao kip’s depreciation, the PPG debt stock rose from 88% of GDP in 2021 to 112% of GDP in 2022. The country is now in “debt distress” (IMF, 2023[11]).

Development diagnostic and priorities

Development is not about getting everything right, but about getting right what matters most. This pertains to both objectives and the actions necessary in order to achieve those objectives. MDCRs have been developed based on the understanding that development is not just about money and growth but also about sustainability and good stewardship of natural resources, as well as human well-being and providing all citizens with the opportunity to reach their full potential. The implementation of Lao PDR’s 9th NSEDP and its associated Financing Strategy offers an important opportunity to deliver on these objectives.

In order to continue its success story, Lao PDR must overcome the current macroeconomic crisis, shift into a higher gear and address the shortcomings of its current development model. The development diagnostic of this report builds on the MDCR methodology, which combines exploring a citizens’ vision of the future (Box 1.1) with an assessment of constraints and opportunities applying the OECD Well-being Framework (Box 1.2) and the “prosperity”, “people”, “planet” and “financing (partnership)” pillars of the SDGs. This diagnostic serves to inform priorities during the ongoing implementation of the Lao PDR government’s own development strategies. Building on these priorities, this report’s recommendations then focus on addressing the current situation and on mobilising the financial means necessary in order to fund Lao PDR’s future sustainable development.

Box 1.1. Vision workshop: Lao PDR: Green Perspectives for 2040

As part of the MDCR process, a vision workshop, Lao PDR: Green Perspectives for 2040, was jointly organised by the OECD and the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) in Vientiane in September 2023. It gathered around 40 stakeholders representing different perspectives (government, academia, the private sector and civil society) in order to capture the aspirations and perspectives of different groups. Narratives of the lives of future citizens were the basis for the vision statement for a green future for Lao PDR.

The future narratives of Lao PDR highlighted aspirations for citizens’ high awareness and engagement in protecting the environment. Most narratives of the lives of future citizens focused on highly educated citizens actively contributing to greening their respective communities, both through their work as teachers or civil servants and through activities in their daily lives in the use of public transportation and electric vehicles, and reducing waste. All have middle-class family lives; decent, stable work; good health; and access to quality education. They live in green cities and enjoy leisure time in green, clean public spaces. An environment with clean water and minimal air pollution and waste, with infrastructure that allows for green transportation, were included in the desired future stories.

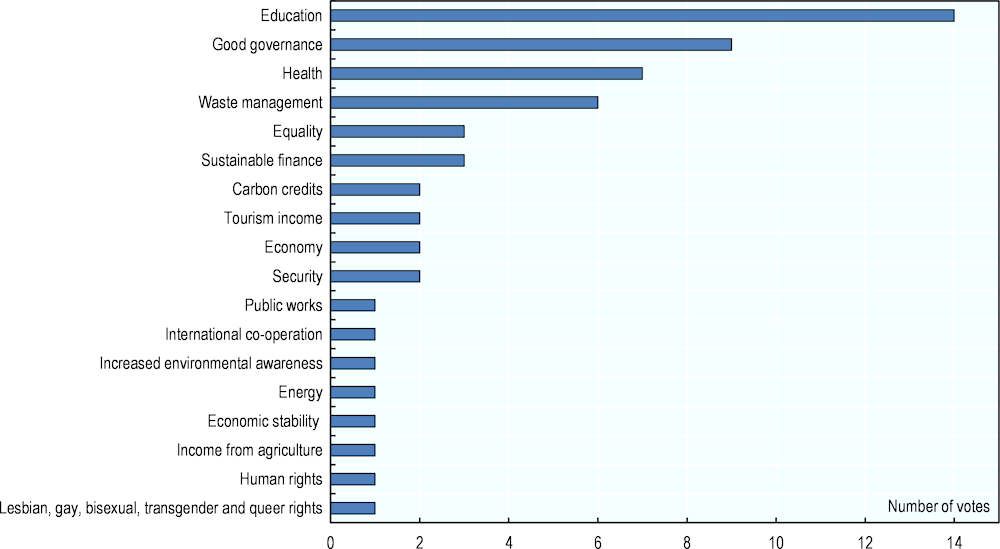

Strong education systems, good governance and the rule of law, a clean environment, and a dynamic economy offering abundant opportunities were all highlighted as the main elements of a desired future for Lao PDR. Following the formulation of narratives and vision statements, workshop participants voted on the most important dimensions of a positive green future. Quality education was ranked highest in the workshop, followed by issues related to good governance (Figure 1.3). Access to (and quality of) healthcare services, functional waste management, sustainable finance, and equality were also ranked high as important dimensions for achieving a desired green future for citizens.

Figure 1.3. Dimensions of a green vision for 2040 in Lao PDR

Selected vision statements for a desired green future in Lao PDR:

“Citizens have high awareness and engage in environmental protection”,

“All stakeholders including government, private sector and communities contribute, engage and benefit from carbon credit trading in agriculture, forestry, renewable energy as well as supporting organic farming.”

“We have successfully built good governance and institutions through effective and efficient co-ordination among multiple stakeholders, specifically effective law and legal enforcement mechanisms from central to local levels, a system that is based on fair, equal, just and transparency, with strong responsibility and commitment. Enhanced institutional research and human resource capacity meet the needs for policy transformation and effective implementation.”

Prosperity: Moving from booming commodities to broad-based opportunities

Past growth and investment in Lao PDR was impressive, but also highly concentrated in a few sectors and dominant state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Lao PDR’s remarkable economic growth has mainly been attributed to capital-intensive sectors such as mining and energy, which have created limited employment opportunities. More than 90% of workers are still employed in sectors with labour productivity below the national average, with more than 50% working in the agricultural sector, generating limited income. A more balanced growth path could generate broader economic opportunities for Laotians. A more diversified economy would also be more resilient to shocks and, possibly, more capable of limiting the rapid loss of natural resources.

In its present state, Lao PDR’s pre-COVID‑19 growth model, which was largely reliant on large infrastructure projects funded through public debt accumulation, is no longer viable. In this context, efforts to diversify the economy and bolster sectors beyond infrastructure (such as tourism and agriculture) can pave the way for a more balanced, diversified and resilient economic landscape in the future. In order to be successful, such efforts will need to be accompanied by an endeavour to establish conditions that are conducive to attracting and mobilising the right financing sources.

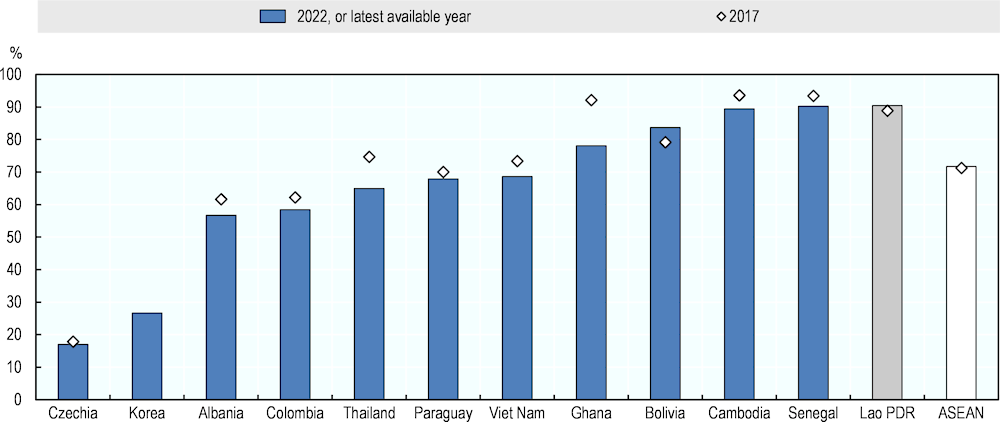

The share of informal employment in Lao PDR stands out in international comparisons and illustrates the concentration of opportunity for only a small proportion of the population (Figure 1.4). Informal enterprises exhibit significantly lower productivity when compared with their formal counterparts, achieving only 13% of the sales per worker that formal enterprises achieve (World Bank, 2019[12]). Informal workers are more likely than employees and employers to experience low job and income security, as well as lower coverage of social protection systems and less protection from employment regulation. The formal sector, which accounts for only 9.5% of employment in Lao PDR, is dominated by government employment and public services (48.4% of formal employment) and by the few larger enterprises that are operating in Lao PDR.

Figure 1.4. Lao PDR’s economy remains informal

Informal employment as a proportion of total employment

Note: Data for Bolivia, Colombia, Lao PDR, Paraguay and Viet Nam are from 2022; data for Albania, Cambodia, Korea and Senegal are from 2019; data for Thailand are from 2018; and data for Ghana are from 2015. No data were available for Korea for 2017. For the ASEAN average, no data were available for Malaysia and the Philippines for 2022 or 2017, and no data were available for Cambodia for 2017.

Source: (ILO, 2023[13]), ILO modelled estimates database, ILOSTAT [database], https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

A thriving private sector that promotes employment and productivity across multiple sectors would be key to creating more broad-based economic growth. Currently, In 2020 Lao PDR had 276 enterprises with more than 100 employees, equivalent to 0.2% of all enterprises in Lao PDR (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2020[14]). Creating a level playing field and a more attractive business environment, developing a supportive financial sector, and addressing skills and human capital shortages would be important in order to support the development of enterprises that can provide opportunities and support innovation.

Investment can play an important role in supporting more broad-based growth. Lao PDR experienced an impressive increase in FDI inflows between 2006 and 2017, which has been one of the main drivers of economic growth. However, the country would benefit from attracting more sustainable investment that advances environmental and social goals. This requires, first and foremost, improving the overall enabling environment for investment in the country. It would also be important for Lao PDR to integrate environmental and social considerations into investment policies and strengthen the implementation of social and environmental safeguards for investment projects.

People: Making human capital development a priority

A more balanced growth path would increasingly rely on human capital. While capital-intensive investments in natural resource extraction and energy generation require limited skilled labour, an economic model with more emphasis on sectors such as manufacturing, agri-business, tourism and services requires larger numbers of qualified workers. Beyond education and skills development, human capital also requires adequate funding for healthcare and a minimum level of social services.

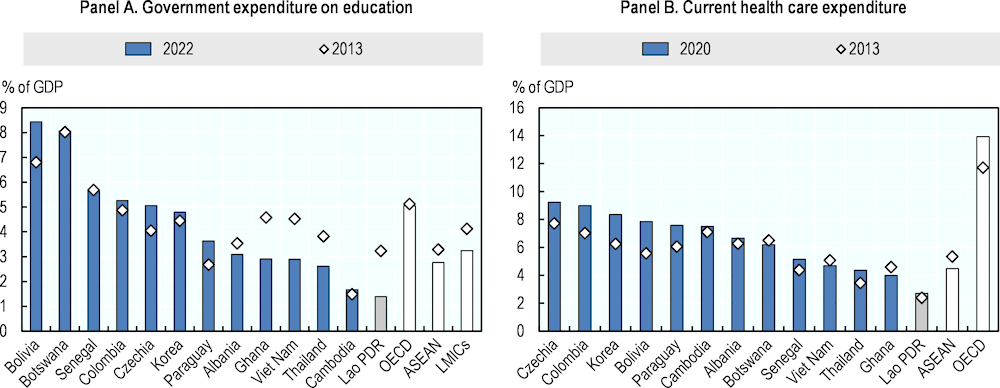

However, human capital development is a pressing development need for which funding capacity must be strengthened. Although Lao PDR has made significant progress in expanding access to primary and secondary education, the quality of education remains low, and enrolment levels for both primary and secondary have started to decline. Completion rates and student performance on international comparison tests are also cause for concern. One particular concern is that Lao PDR exhibits low spending on social services as well as for environmental protection. Government expenditure on education stands at around 1.4% of GDP in Lao PDR compared with 3.2% for the average lower middle-income country (LMIC), and healthcare expenditure represents a mere 2.7% of GDP (compared with 3.9% on average in LMICs) (World Bank, 2024[5]). Similarly, government expenditure on healthcare, which totalled 1.2% of GDP in 2020, remains far from the 4% of GDP recommended by the World Health Organization (ADB, 2023[15]) (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Government expenditure in social sectors in Lao PDR ranks among the lowest in the world

Note: Panel A: Data for Korea are from 2015 instead of 2013; data for Bolivia, Botswana, Colombia and Korea are from 2020 instead of 2022; and data for Albania, Cambodia, Czechia and OECD member countries are from 2021 instead of 2022. Panel B: Data for Albania are from 2018 instead of 2020.

Source: (World Bank, 2024[5]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators(accessed on 15 January 2024).

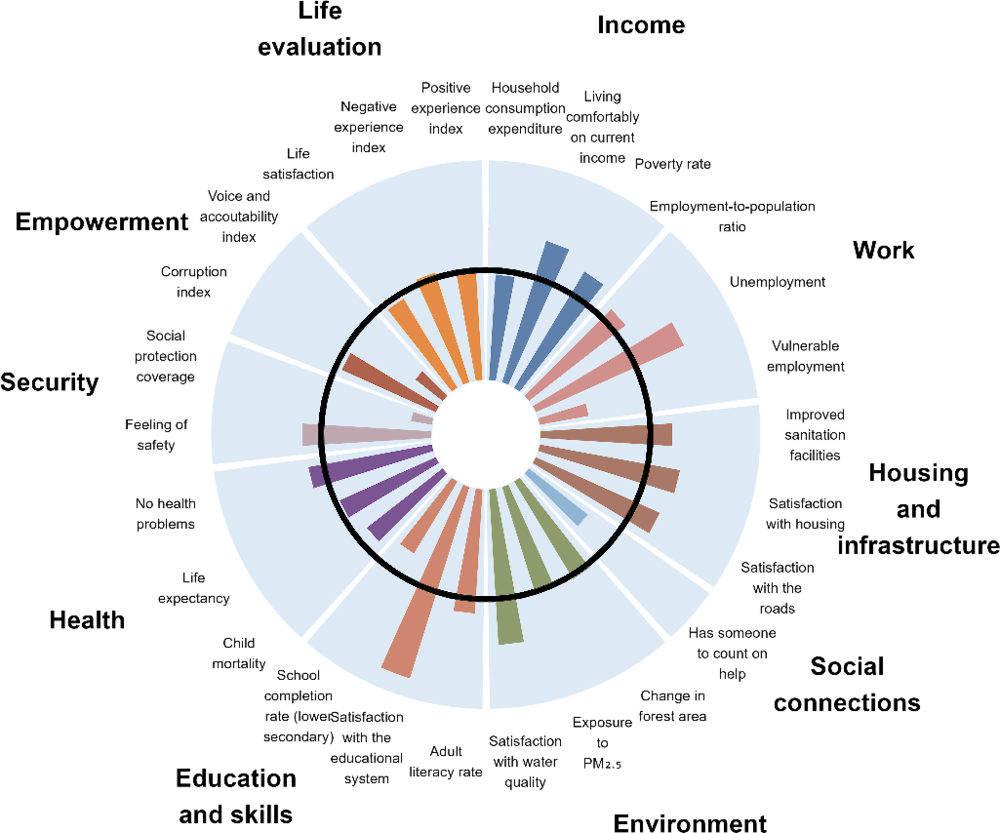

Box 1.2. How is life in Lao PDR? Viewed through the OECD well-being lens

The OECD Framework for Measuring Well-Being and Progress uses a mix of objective and subjective indicators to account for people’s well-being (OECD, 2017[16]). A well-being lens allows countries to identify areas where their performance is better or worse than other countries at similar levels of GDP per capita. Comparing Lao PDR with countries that have similar levels of GDP per capita (Figure 1.6) shows the country’s performance across outcome indicators in ten dimensions of well-being (bars longer than the black circle represent better performance, whereas bars shorter than the black circle represent worse performance).

Figure 1.6. Current and expected well-being outcomes for Lao PDR: Worldwide comparison

Note: The observed values falling inside the black circle indicate areas where Lao PDR performs poorly in terms of what might be expected from a country with a similar level of GDP per capita. Expected well-being values (the black circle) are calculated using bivariate regressions of various well-being outcomes on GDP using a cross-country dataset of around 150 countries with populations of more than 1 million people. All indicators are normalised in terms of standard deviations across the panel. M2.5 = particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 microns or smaller.

Source: IQAir, (2023[17]) World’s most polluted countries & regions (2018-2022), https://www.iqair.com/world-most-polluted-countries; (World Bank, 2024[5]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/; (Gallup, 2023[18]), World Poll: 2006-2023, https://www.gallup.com/analytics/318875/global-research.aspx; Transparency International (2023[19]), Corruption Perceptions Index 2023 (database) https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022; FAO and UNEP (2020[20]), The state of world’s forest 2020, https://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/en/; WHO (2023[21]), Global Health Observatory, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/population-using-improved-sanitation-facilities-(-); UNESCO (2023[22]), UNESCO Institute for Statistics, http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=3803.

Overall, Lao PDR performs at a level comparable to other countries at the same level of economic development. It performs slightly better with regard to poverty, income, unemployment, housing, and satisfaction with education and water quality. However, the share of informality in employment is much higher in Lao PDR than in other countries with a similar level of GDP per capita. The same holds true for secondary school completion rates, for social protection coverage and for empowerment.

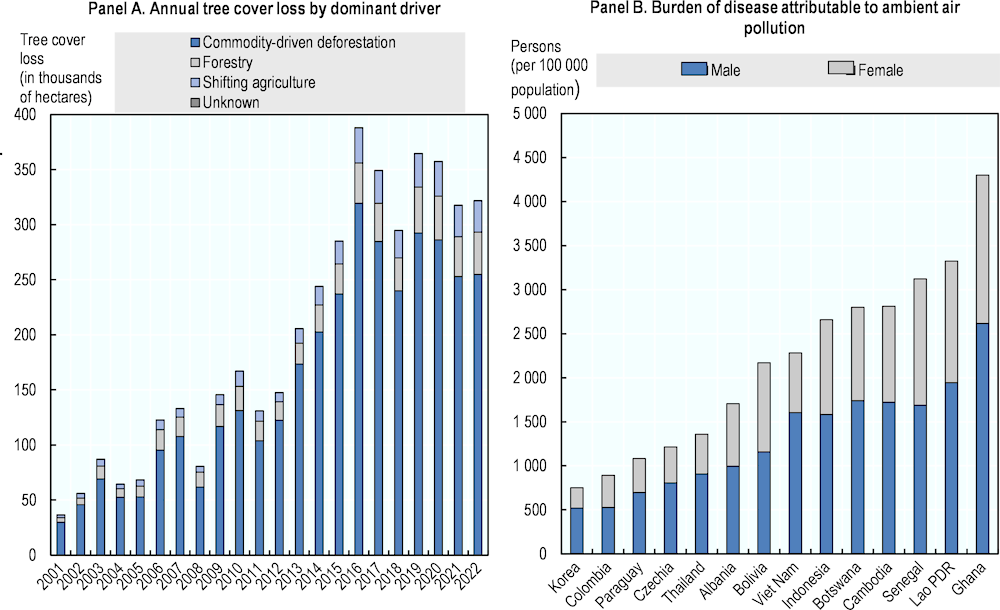

Planet: Preserving Lao PDR’s abundant natural resources and fighting air pollution

The current growth model has put pressure on the environment and biodiversity at a cost for the economy, and for the well-being of Lao PDR’s citizens and nature. Lao PDR’s abundant natural resources have historically fuelled the country’s prosperity, particularly in the agricultural, tourism, mining and hydropower sectors. However, the current growth model has put pressure on the country’s environment and biodiversity. Forests, grasslands and other terrestrial habitats are being degraded, fragmented and lost as a result of the expansion of industrial agriculture and commercial timber extraction, which also threatens biodiversity (Figure 1.7) (World Bank, 2020[23]). “Slash-and-burn” agriculture, where farmers clear and burn forests in order to create ash-fertilised soil, is another major driver of forest degradation in Lao PDR. Estimates suggest that forest loss alone causes annual damage equal to 3% of Lao PDR’s GDP (World Bank, 2021[24]). In addition, large-scale hydropower dams have been associated with negative effects on the environment and local communities, with impacts on water quality and sediment flows, hydrology and water levels, aquatic ecosystems, and food security. Mining projects and hydropower dams are also frequently located in protected areas or close to important tourism and natural sites; such projects and dams can have adverse effects on the environment and scenery, and can discourage tourism.

Air pollution is a significant challenge and poses health risks. Air pollution (measured in particulate matter (PM), and especially particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 microns or smaller (PM2.5)) in Lao PDR exceeds national and international air quality standards, and Lao PDR’s burden of disease caused by ambient air pollution is high compared with its peers (Figure 1.7). Chronic exposure to PM2.5 considerably increases health risks, particularly the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (OECD, 2024[25]). Estimates suggest that 22% of all deaths are related to environmental pollution and 27% of these deaths are from ambient air pollution. Health costs related to ambient air pollution amounted to 3.5% of Lao PDR’s GDP, and environmental health costs amounted to 15% of Lao PDR’s GDP in 2017 (World Bank, 2021[24]).

With regard to climate change, Lao PDR is simultaneously increasing emissions that contribute to climate change and becoming more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, especially floods and droughts. Lao PDR’s 2019 carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP (0.339 kilogrammes (kg) per 2017 purchasing power parity USD) were among the highest in the ASEAN region and were above the average for LMICs (0.236 kg per 2017 purchasing power parity USD). The commissioning of the 1 878 megawatt lignite-fired power plant in Hongsa in 2015 is the main driver of the increase in emissions; the plant produces electricity that is predominantly (95%) exported to Thailand. Furthermore, there are additional coal-fired plants in the pipeline – specifically in Xekong, Lamam, Houaphan and Boualapha – which could further increase Lao PDR’s carbon emissions intensity (Asian Development Bank, 2019[26]). Lao PDR’s vulnerability to climate change has been growing with the increase in extreme weather events. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events, resulting in more frequent and more severe flooding in vulnerable and rapidly growing cities along the Mekong River (UNEP GRID Geneva, 2024[27]).

Figure 1.7. Lao PDR’s current economic development model has caused a decline in natural assets and affected people's health

Note: Panel A: The methods used to collect these data have changed over time, especially after 2015 (Global Forest Watch, 2021[28]), Assessing Trends in Tree Cover Loss Over 20 Years of Data. “Commodity-driven deforestation” refers to large-scale deforestation linked primarily to commercial agricultural expansion. “Shifting agriculture” refers to the temporary loss of forest cover or permanent deforestation due to small- and medium-scale agriculture. “Forestry” refers to the temporary loss of forest cover from plantation and natural forest harvesting, with some deforestation of primary forests. The commodity-driven deforestation represents permanent deforestation, while tree cover affected by the other categories often regrows. The dataset does not indicate the stability or condition of land cover after the tree cover loss occurs. Panel B: Age-standardised data.

Source: Panel A: (Global Forest Watch, 2023[29]), Tree Cover Loss by Dominant Driver, www.globalforestwatch.org. Panel B: (World Bank, 2024[5]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 23 September 2023).

Lao PDR’s abundant nature holds the potential for green and climate finance at scale, if the necessary capabilities are put in place. Mechanisms such as carbon credits show increasing potential, with an estimated global market potential of more than USD 50 billion by 2030 (McKinsey, 2021[30]). Most green finance instruments require robust monitoring and reporting mechanisms and strict transparency and verification processes, and environment statistics are crucial to both. In order to support Lao PDR’s efforts to harness innovative financing such as carbon credits, the country’s statistical systems and data collection methods need to be strengthened, especially in the areas of environmental protection and climate adaptation and mitigation.

Lao PDR’s development strategy framework reflects many of the priorities of this report’s diagnostic. The country’s sustainable development agenda is anchored in two overarching documents: Vision 2030 and 10-Year Socio-Economic Development Strategy (2016-2025), published in 2016, and the National Green Growth Strategy of the Lao PDR until 2030, adopted in 2019. This vision is backed by subsequent strategic documents, in particular the 9th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan (2021-2025) (which received a mid-term review in 2023) and the associated Financing Strategy, which was released in 2023 (Box 1.3). In addition, the country has developed a Smooth Transition Strategy (STS) for its graduation from the United Nations (UN) list of least developed countries (LDCs) in 2026. Moreover, the National Green Growth Strategy (NGGS) defines green growth in the context of Lao PDR as “raising the efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability of the utilization of limited natural resources” (Lao People's Democratic Republic, 2018[31]) and sets green growth objectives for different sectors and policy areas . In addition, Lao PDR’s Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry has published a Green and Sustainable Agriculture Framework for Lao PDR to 2030 (MAF, 2021[32]).

Box 1.3. Lao PDR’s sustainable objectives: The 9th NSEDP and the associated financing strategy

Lao PDR’s 9th NSEDP

Lao PDR’s 9th NSEDP emphasises green and sustainable economic growth. It also seeks to develop the country’s full potential to grow its manufacturing and service sectors in line with green and sustainable development principles, in the context of preparing for Lao PDR’s graduation from the UN’s LDC list. The NSEDP’s overall directions include striking a balance between economic and social development and environmental protection, effectively implementing the NGGS, and progressing towards the SDGs. The 9th NSEDP emphasises the importance of both a comprehensive economic transformation based on the country’s potential and of a climate change response strategy and disaster risk preparedness. In order to achieve the overall directions of the 9th NSEDP, efforts are focused on implementing the following six main outcomes:

Outcome 1: Continuous quality, stable and sustainable economic growth achieved

Outcome 2: Improved quality of human resources to meet development, research capacity, science and technology needs, and to create value-added production and services

Outcome 3: Enhanced well-being of the people

Outcome 4: Environmental protection enhanced and disaster risks reduced

Outcome 5: Engagement in regional and international co‑operation and integration is enhanced with robust infrastructure and effective utilisation of national potential and geographical advantages

Outcome 6: Public governance and administration is improved, and society is equal, fair, and protected by the rule of law.

The 9th NSEDP Financing Strategy

The financing needs for the sustainability-related aspects of the 9th NSEDP are substantial. The 9th NSEDP Financing Strategy identifies 19 policy directions and 54 practical actions focusing on priority sectors that are vital to Lao PDR’s sustainable development progress: human capital (health and education), green and climate-resilient growth, a focus on outcomes for people, and environmental sustainability. Within this comprehensive reform framework, several priorities emerge, as follows:

The relinking of fiscal policy with inclusive growth is the most important precondition to continued development progress without risking the environmental and climate objectives specified in Lao PDR’s nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Broadening the tax base in order to ensure sufficient revenues for development is paired with the need for public and foreign financial flows to contribute more directly to Lao PDR’s development objectives.

The mid-term review of the 9th NSEDP

The priority is to build a solid foundation for Lao PDR’s economic recovery. This foundation could include an emphasis on the country’s demographic transition and the comparative advantages that brings. At the same time, the severe impacts of Lao PDR’s current macroeconomic issues on the most vulnerable citizens must continue to be recognised and the risks to vulnerable communities mitigated.

Short-term prospects for pro-poor growth are clouded by the threat of continued macroeconomic instability and the further reduction of developmental expenditures as a result of unsustainable debt obligations. The immediate objective is to protect purchasing power and access to public services from macroeconomic instability and fiscal pressure on social spending.

Medium-term prospects for poverty reduction and shared prosperity are impeded by stagnant job creation, which creates non-pro-poor growth. Therefore, the next objective is to improve the labour opportunities and incomes of vulnerable households. A third objective could be to strengthen sustainable livelihoods through better management of natural resources.

Source: (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[33]) 9th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan; (Government of Lao PDR, 2023[34]) The 9th national Socio-Economic Development Plan Financing Strategy (2023-2025); (Government of Lao PDR, 2024[35]), 9th Five-year National Socio-Economic Development Plan (2021-2025). Mid-Term Review.

Financing sustainable development in Lao PDR: Diagnostic and recommendations

Financing sustainable development: Doing what it takes

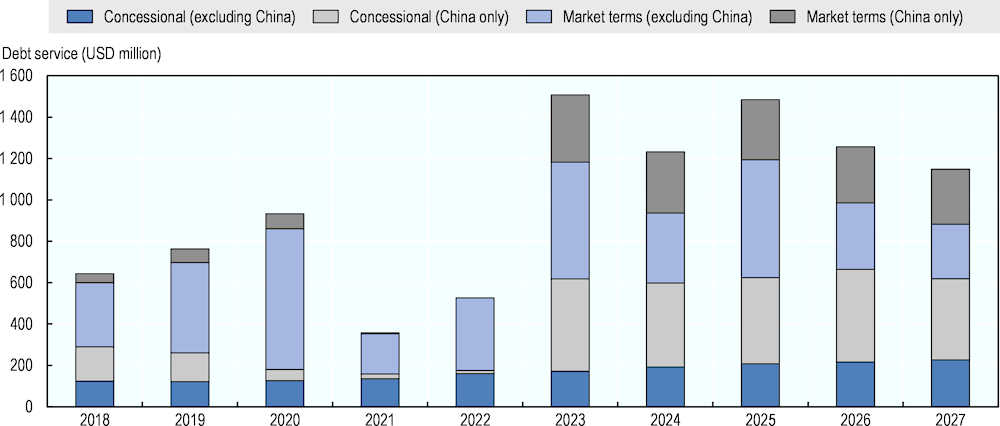

Looking ahead, Lao PDR faces a challenging financing landscape. Debt service is projected to surge over the coming years (Figure 1.8). Low levels of government revenue, combined with increasingly restrictive global financing conditions, have made it more challenging for the country to fulfil its financing needs, jeopardising its financial stability. This is reflected in the slow recovery of financing flows to the country. Exacerbating this problem are the elevated interest rates that Lao PDR faces as a result of increasingly restrictive global financing conditions and the downgrade of its sovereign credit rating in 2022.

Figure 1.8. Lao PDR confronts a surge in debt service costs beginning in 2023

External PPG debt service (2018‑27)

Source: (Government of Lao PDR, 2022[9]), Public and Publicly Guaranteed Debt Statistic Bulletin, https://www.mof.gov.la/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2022-Public-and-Publicly-Guaranteed-Debt-Bulletin-of-Lao-PDR-Final.pdf.(accessed on 13 October 2023).

Lao PDR’s fiscal situation has adversely affected its sovereign credit rating, constraining the country’s ability to secure new financing. The decline in the country’s fiscal position is expected to pose challenges for debt servicing in the coming years, given the limited options for Lao PDR to roll over and refinance its debt. According to the latest World Bank/International Monetary Fund Debt Sustainability Analysis, Lao PDR is now in debt distress. The country is grappling with significant financing needs and liquidity pressures that are expected to persist for years to come. The suspension of debt service negotiated with the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) prevented a default during the COVID‑19 crisis, but this merely postponed the underlying debt issue. Debt service was projected to surge by 186% in 2023 compared with 2022, reaching USD 1.51 billion, and it is expected to remain above USD 1 billion through at least 2027 (Government of Lao PDR, 2022[9]).

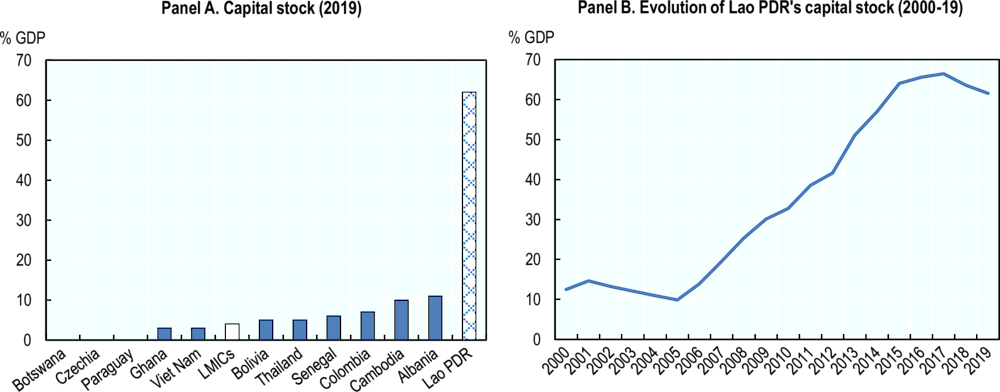

Lao PDR’s reliance on public-private partnerships (PPPs) for major investments has contributed to the country’s fiscal challenges. In fact, Lao PDR has the highest volume of PPP capital stock in the world as a proportion of GDP. While the government’s extensive use of PPPs has been successful in attracting investment, it has also introduced fiscal challenges and risks that have contributed to the country’s debt problems. These challenges include forgone revenue from tax exemptions, fiscal commitments and contingent liabilities. The fact that Lao PDR exhibits low PPP regulatory quality for PPPs is an added concern considering the fiscal significance of such partnerships. Heavy reliance on PPPs seems unsustainable in the long term as a way of encouraging investment and economic growth. PPPs have stimulated the rapid growth of the country’s capital stock, making it a global outlier due to the outsized volume of its PPP capital stock as a proportion of GDP (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9. Lao PDR has become an outlier in terms of capital stock arising from public-private partnerships

Source: (IMF, 2021[36]), Investment and Capital Stock Dataset (database), https://data.imf.org/?sk=1ce8a55f-cfa7-4bc0-bce2-256ee65ac0e4 (accessed on13 October 2023).

The NSEDP Financing Strategy acknowledges the gap between the Lao PDR government’s development priorities and actual allocations of public resources. A strategic focus on healthcare, education and the environment in the 9th NSEDP and its Financing Strategy reflects the government’s commitment to sustainable development and inclusive growth, and is designed to address the interlinked challenges of reducing poverty, improving the quality of life for Lao PDR’s citizens and safeguarding natural resources. However, some of the sectors with negative social and environmental effects account for a sizeable share of public expenditure. For example, energy, mining and public works together made up more than 20% of Lao PDR’s public spending in 2020. On the other hand, Lao PDR presents low spending in social sectors and environmental protection. A sustained underinvestment in these areas not only affects immediate well-being but can also hinder human capital formation, which is crucial for Lao PDR’s overall growth trajectory and competitiveness on the global stage. Similarly, insufficient financial support for environmental protection and climate action could ultimately pose a threat to the implementation of the NGGS.

In order to effectively pursue its ambitious sustainable development agenda, Lao PDR must address its debt issues and the fragmented governance of its financing framework. Tackling these challenges is fundamental for building the type of sound environment required in order to harness additional and innovative resources in support of the country’s development goals. This necessitates efforts to boost tax revenues, diversify investments and develop the domestic financial sector. Given Lao PDR’s current financial constraints, sustained international support is essential in order to safeguard investments in key development areas, such as healthcare and education. In parallel, designing preventive strategies is crucial to ensuring long-term financial stability and avoiding future debt issues.

Meeting Lao PDR’s development ambitions will require better generation of revenue. Lao PDR’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains stuck at a level that is too low to support development despite significant economic growth. The significant debt service burden further exacerbates this situation. A radical change to the design, evaluation and administration of the tax system is a necessary condition for a sustainable way forward. A robust revenue system would provide a steady stream of resources that can be channelled into crucial public services and infrastructure. It also reduces the country’s dependency on external finance, ensuring that domestic priorities can be consistently met.

In order to address the immediate needs of the current economic situation, multilateral development partners have coined the “Vital 5”. These five suggestions summarise a reform road map prepared by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank in support of the Lao PDR government’s National Agenda on Addressing Economic and Financial Difficulties, covering the period from 2021 to 2023 (which has been extended until 2025) (World Bank and Asian Development Bank, 2022[37]):

Cut costly tax exemptions in order to raise public revenue and protect social spending.

Improve the governance of public and public-private investment.

Restructure public debt through ongoing negotiations.

Strengthen the financial sector’s stability through legal and regulatory tools.

Enhance the business environment via effective regulatory reforms.

Key recommendations in order to strengthen sustainable development financing in Lao PDR

In the short term, Lao PDR should deleverage in order to reduce the debt burden and re-establish macroeconomic stability:

Address the country’s fiscal challenges in order to break the vicious cycle of escalating debt, currency depreciation and high inflation:

Seek debt relief from the country’s primary lender (i.e. China) in order to free up fiscal space and alleviate short-term payment pressures.

Co‑ordinate and communicate transparently with development partners in order to avoid moral hazard concerns, ensuring that any new concessional financing results in additional investment in development.

Gradually shift the emphasis of fiscal consolidation efforts from expenditure reduction to increased revenue generation and spending efficiency in order to ensure the sustainability and credibility of the fiscal adjustment.

Mitigate mounting fiscal risks arising from contingent liabilities associated with PPPs and SOEs:

Audit existing SOEs and PPPs in order to evaluate their fiscal risk profiles and identify urgent threats to macroeconomic stability.

Define and enforce strict criteria for government guarantees in order to minimise fiscal exposure, ensuring that such guarantees are only issued when absolutely necessary.

Identify and enact quick-win reforms (such as cost-cutting and operational efficiency improvements) in those SOEs that present the riskiest profiles in order to stabilise SOE finances.

Communicate clearly with development partners and the public about the short-term fiscal risks identified in SOEs and PPPs, and about the measures being taken to address them.

In the medium term, Lao PDR should establish a sound framework in order to secure financing for the country’s development goals:

Address the current fragmentation and lack of co‑ordination in the country’s sustainable development financing landscape:

Establish a shared and well-co‑ordinated governance of the sustainable development financing agenda among the multiple government stakeholders involved, including the co‑chairing of key committees.

Ensure adequate resourcing of, and institutional engagement in, the sector and subsector working groups of Lao PDR’s Round Table Process.

Secure the active participation of, and garner contributions from, all relevant development partners in strategic development and aid co‑ordination mechanisms, including the Integrated National Financing Framework.

Develop a clear and coherent governance framework for sovereign carbon finance in order to promote a co‑ordinated approach across the government, avoiding inefficiencies and reputational risks that could jeopardise this new financing source.

Take steps to safeguard the impact and effectiveness of development co‑operation:

Reinvigorate the multi-stakeholder dialogue around the Vientiane Declaration on Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (2016-2025), as well as efforts to monitor the implementation of the Country Action Plan for the Implementation of the Vientiane Declaration on Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (2016-2025).

With a view to maximising international support for sustainable development, use existing aid co‑ordination platforms in order to consult partners on key governance and institutional issues constraining development co‑operation flows to Lao PDR.

Enhance spending efficiency and build greater capacity for revenue collection:

Explore opportunities with key development partners for enhanced support on public financial management and domestic resource mobilisation appropriate to Lao PDR’s fiscal context and challenges.

Develop and implement a comprehensive action plan to increase government revenue, with clear and credible revenue targets.

Review the current investment promotion framework in order to assess its costs and benefits, factoring in the effect of tax incentives on government revenue.

Create and strengthen a centralised public debt management function with authority over public debt issuance:

The legal framework should clarify which body has the authority to borrow and to issue new debt; to invest; and to undertake transactions on the government’s behalf.

Credit risk assessment and validation should be centralised for all public debt issuance, including by SOEs.

In the long term, Lao PDR should lay the foundations to shift away from the current growth model that generates fiscal burdens and take preventive measures in order to avoid debt issues in the future:

Strengthen the business environment in order to encourage greater private sector development, reducing the strong reliance on public investment:

Carry out an in-depth review of the role, governance and performance of the country’s SOEs, which can help inform an action plan to tackle the negative implications of their dominant position in Lao PDR’s private sector development.

Strengthen the local banking sector in order to reduce financial sector vulnerabilities and fiscal liabilities while promoting enhanced credit provision to the private sector.

Identify new drivers for foreign private investment, and seek development partner support in order to design an integrated and cross-cutting investment promotion strategy that considers the impacts on various sectors of the economy and aligns with Lao PDR’s sustainable development objectives.

Engage with South-South partners and regional platforms in order to exchange knowledge and experiences with regard to maximising the development impact of remittances, including through policies supporting increased human capital and productive investments.

Promote sustainable borrowing policies and practices, and design formal mechanisms for contingency planning:

Continue the policy dialogue on debt management initiated with the main international financial institutions and identify key functions of government that require additional technical support.

Seek technical support and capacity building from development partners in key areas of sustainable development finance, specifically in order to better harness finance opportunities and to design sound frameworks allowing Lao PDR to tap into innovative or nascent financing instruments in the future, including carbon and biodiversity finance.

Explore and assess the benefits for Lao PDR of mechanisms to stabilise and sustainably manage future revenues from commodity exports such as hydropower and mining.

Develop a knowledge base and robust country systems in order to harness innovative financing sources:

Strengthen the country’s statistical systems and data collection processes – especially with regard to environmental protection and climate adaptation and mitigation – in order to support Lao PDR’s efforts to harness innovative financing such as carbon credits.

Keep abreast of developments and the experiences of regional peers with regard to green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked bonds as possible instruments to consider in the future, once Lao PDR is back to sustainable debt levels.

Lao PDR presents vast scope for improving the mobilisation and use of government revenue

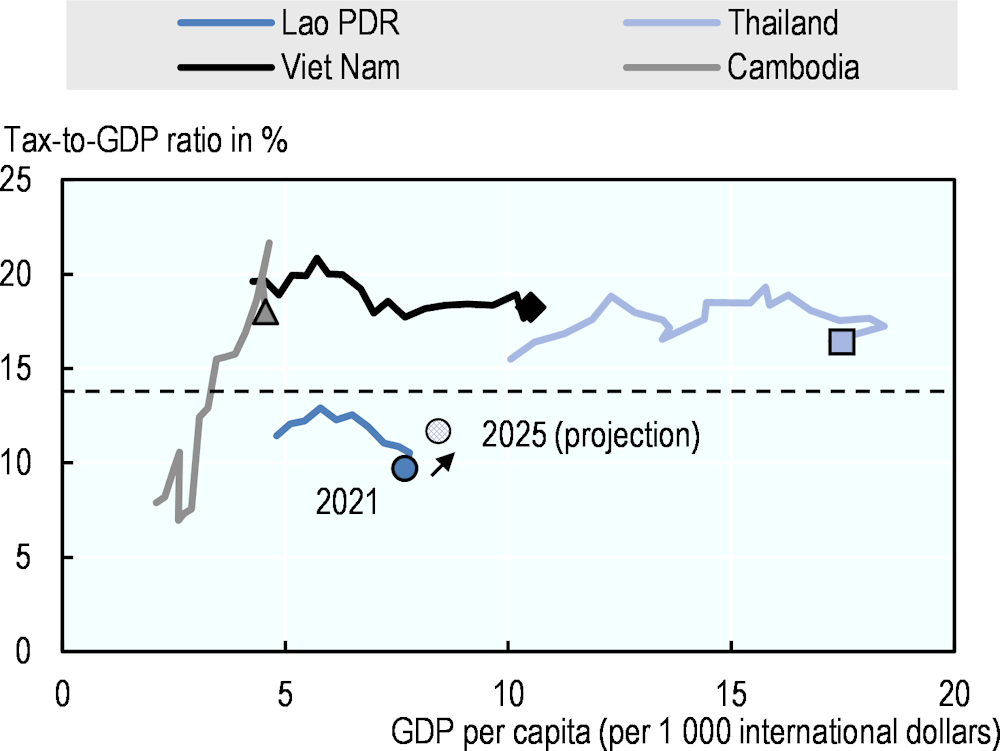

The strong and sustained economic growth experienced by Lao PDR has not translated into an increasing tax-to-GDP ratio. While most countries enhance their revenue mobilisation capacity as their economies mature, Lao PDR’s tax revenue has shown little responsiveness to the country’s economic growth. As a result, Lao PDR stands out for its low capacity to raise taxes, having the lowest tax-to-GDP ratio out of all ASEAN Member States. Lao PDR’s tax-to-GDP ratio in 2021 was less than 10%, in contrast to Thailand’s 16%, Viet Nam’s 17% and the OECD average of almost 35% (Figure 1.10).

The decline in the tax-to-GDP ratio reflects a lack of tax revenue “buoyancy”. Tax revenue buoyancy refers to a state in which tax revenues grow faster than GDP on average, generating more resources and a higher tax-to-GDP ratio as a country develops. Buoyant tax revenues can indicate that it may be sufficient for a developing country to maintain its current tax policy path because future GDP growth will result in a growing tax-to-GDP ratio. This is not the case in Lao PDR. The significant debt service burden in addition to the very high inflation rate further exacerbate this situation. The high level of informality further limits the revenue-raising potential of taxes and reduces the reach of the social protection system in Lao PDR.

Figure 1.10. Evolution of tax revenue and GDP in Lao PDR and peer countries until 2021

GDP per capita and tax-to-GDP ratio (2001-21)

Note: Tax-to-GDP ratio and GDP per capita paths until 2021. The lines represent values prior to 2021. The dots refer to the value for each country in 2021. The dashed line represents the revenue target that the Lao PDR government specified in the NSEDP (14%).

Source: (OECD, 2022[38]) Revenue Statistics 2022: The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues; (OECD, 2023[39]) Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2023: Strengthening Property Taxation in Asia; GDP data from (IMF, 2023[40]), World Economic Outlook Database (accessed on 5 September 2023); (World Bank, 2023[41]) Lao PDR Economic Monitor; (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[33]), 9th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan 2021-2025.

Without reform, Lao PDR will miss its 2025 tax revenue target. According to its 9th NSEDP, Lao PDR aims to increase the tax-to-GDP ratio from 11.05% in 2020 to 14.00% by 2025 (i.e. by 2.95 percentage points) (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[33]; World Bank, 2023[41]). On its current path, with a declining tax revenue ratio despite economic growth, Lao PDR will fail to meet this target. Revenue Statistics 2022: The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues

In addition, the country’s acute macroeconomic and governance challenges create issues for tax policy. Addressing Lao PDR’s acute debt-servicing challenges will bind tax revenue and require additional revenue if large spending cuts are to be avoided. A credible debt-servicing and repayment plan needs to be developed that will increase transparency and reduce government debt to a sustainable level. In addition, Lao PDR’s large debt-servicing obligations could potentially make it more difficult for the country to pass revenue-raising tax reforms because taxpayers may be less willing to pay taxes if the revenue is used to service debt that would otherwise be deferred. Ensuring that economic growth translates to higher tax revenues – not only in total amounts but also as a percentage of GDP – is a crucial element of a strategy that puts government debt on a sustainable downward trajectory. Inflation has eroded the net income of a large share of Lao PDR’s population, and there has likely been an uptick in poverty (World Bank, 2023[41]), which reduces the ability of lower- and middle-income taxpayers to afford additional tax increases.

These acute challenges come in addition to structural difficulties, which require additional government revenues and a well-designed tax system. Lao PDR has significant unmet spending needs. Financing gaps are particularly significant if Lao PDR wants to achieve universal social protection by 2030. The formal social protection system (which is funded through social security contributions (SSCs)) only covers 300 000 workers out of a total population of more than 7 million. Economic inequality is on the rise in Lao PDR, and the tax system has so far been unsuccessful in stopping this trend. Evidence from private household expenditure data indicates growing inequality in consumption expenditure (Warr, Rasphone and Menon, 2018[42]).

In addition, most workers and enterprises operate in the informal economy, and the tax system is not conducive to business and worker formalisation. Only 10‑20% of employment in Lao PDR occurs in the formal economy and more than 70% of businesses in Lao PDR are not registered, according to the latest estimates (ILO, 2023[43]). The high level of informality limits the revenue-raising potential of taxes and reduces the reach of the social protection system in Lao PDR. The design of the current tax system contributes to a polarised economy that generates too little revenue for the government.

Weak human capital development is another major structural vulnerability with implications for tax policy. Lao PDR will not be able to grow its economy sustainably without investing in a skilled domestic workforce (which requires public resources) and without ensuring that skilled workers find good-quality jobs that pay well. Lao PDR has to balance its need to increase revenue in order to invest in human capital development with ensuring that the tax burden on labour does not become so large that it entices more skilled workers to leave the country.

The tax system has a larger role to play in safeguarding the environment and ensuring that economic growth is sustainable. Environmental degradation comes at a significant economic and societal cost. Estimates suggest that forest loss alone caused annual damage to Lao PDR’s economy equal to 3% of its GDP (World Bank, 2021[24]). In the future, the tax system needs to play a central role in: (i) ensuring that society benefits in the form of tax revenue when natural resources are exploited; (ii) mitigating environmental damage; and (iii) steering the economy towards a more sustainable growth model.

Key recommendations for generating sustainable fiscal revenue

Strengthen the buoyancy of the tax system in order to ensure that the tax-to-GDP ratio increases when the economy grows:

Address concrete tax design flaws across all types of taxes and change the approach to designing, administering and evaluating the tax system.

Identify a set of reforms that gradually increase tax revenue buoyancy (and raise tax revenue) while also turning the tax system into a positive force that helps address other developing challenges, such as high inequality, inadequate social protection, high informality or the lack of investment.

Reconsider the suboptimal tax incentive strategy in SEZs and the corporate income tax (CIT) system based on differentiated rates by sector:

Grant tax incentives according to predetermined, uniform and clearly declared criteria; the authority to grant tax benefits should lie exclusively with the Ministry of Finance (MOF).

Shift the focus away from profit-based tax incentives and towards expenditure-based ones.

Move away from providing reduced CIT rates according to economic sector.

Levy a “top-up tax” on certain businesses in SEZs, bringing their effective tax rate to the new global minimum tax rate of 15%.

Make tax benefits in SEZs more conditional on the employment or training of local workers and on complying with other laws, such as registering workers for social security.

Assess the tax revenue impact of interactions between SEZs and the national economy.

Launch a thorough cost-benefit evaluation of the SEZ regime’s impact on investment.

Gradually work towards a consistent international taxation framework in order to reduce revenue leakages:

Consider transitioning to a worldwide tax regime for personal income in order to tax the foreign-sourced income of individuals who are Lao PDR tax residents.

Conversely, consider switching to a territorial tax system for business income in order to reduce the administrative burden linked to a worldwide business tax regime.

Implement transfer pricing guidelines.

Sign up for international tax information sharing in order to gain access to information about financial accounts held by Lao PDR residents in foreign jurisdictions (which will be relevant if the country decides to switch to a worldwide tax system for personal income).

Analyse the tax revenue risk from other tax planning strategies that are potentially being employed by multinational enterprises (for example, through gaining access to country-by-country reports).

Reform other features of the tax system that introduce distortions or that contribute to low revenues and the limited equity of the tax system:

Introduce an official land register and better-defined land property rights.

Devise a mechanism to link property taxes to the evolution of land prices, and increase the land tax.

Consider an upward adjustment of the personal income tax and SSC maximum contribution thresholds and index the thresholds to inflation.

Maintain the increased CIT rate for the natural resource sector, but evaluate whether it is effective at taxing resource rents or entirely undermined by tax incentives or profit shifting.

Enhance customs procedures and border checks in Lao PDR in order to reduce high levels of fraudulent behaviour and reduce the administrative cost faced by importers.

Reduce the number of different taxes and levies to be paid when importing goods and services.

Increase the effective taxation of harmful products (health taxes) and develop a consistent tobacco tax strategy.

Refrain from pursuing further untargeted tax cuts; instead, prioritise improving the design and enforcement of the tax system in order to increase tax buoyancy.

Co‑ordinate with neighbouring countries in order to avoid or limit harmful tax competition.

Improve the design of the presumptive tax regime in order to increase its effectiveness at encouraging formalisation and to limit tax revenue loss:

Lift the presumptive tax regime’s three-year eligibility limit.

Remove the additional eligibility rule based on asset ownership.

Include SSCs in the scheme.

Introduce a transition path between the presumptive and the standard tax system.

Evaluate the introduction of sector-specific taxes on turnover.

Offer a one-stop tax office.

Limit abusive practices.

Increase the role of the tax system as a tool to promote the formalisation of workers and businesses:

Abolish fees to register workers for social security.

Make social security forward-looking in order to help ensure that enterprises do not have to pay SSCs retroactively if they register workers.

Disallow enterprises from deducting the labour cost of workers as a business expense if the workers are not registered with the social security administration.

Make investment tax incentives conditional on compliance with other legal obligations, including registering workers for social security.

Advertise that future “insurance-type” government benefits are conditional on registration as a formal worker or business and having contributed to social security.

Consider introducing a progressive SSC schedule with reduced rates for lower-income workers that are matched by government contributions.

Allow workers to view the contributions that they have made to social security and their accumulated pension rights (e.g. through an online portal) in order to counter the perception that these contributions are “lost”.

Overhaul the approach to designing, evaluating and administering the tax system:

Increase collaboration among ministries and other government institutions.

Strengthen the MOF’s position as the key actor in tax policy making and make the MOF’s consent mandatory for any tax policy change.

Unify all legal provisions pertaining to one type of tax in one tax law that is made available online for taxpayers to consult.

Consider establishing an independent tax revenue agency that would be responsible for revenue collection.

Devise a formal dispute resolution mechanism in order to resolve tax disputes.

Increase efforts to prioritise non-cash payments in order to settle tax bills.

Maintain and strengthen recent initiatives to modernise and digitalise the tax administration.

Establish and strengthen a stand-alone tax policy analysis unit within the MOF that evaluates and assesses tax policy.

Stimulating sustainable investment in Lao PDR

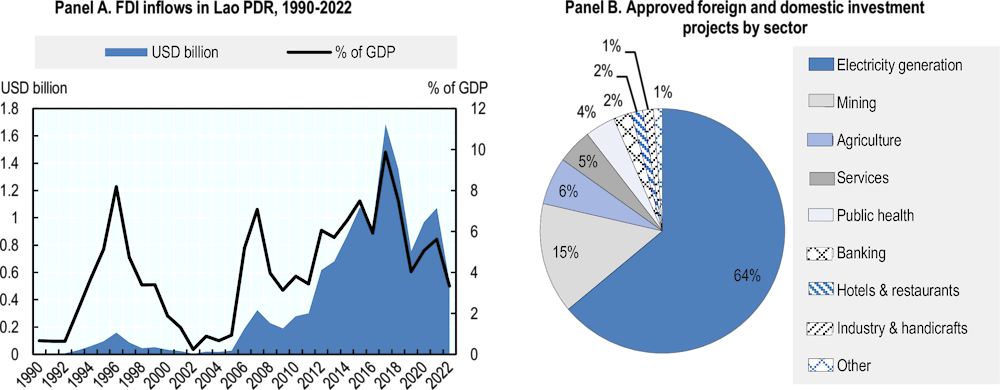

Lao PDR experienced an impressive increase in FDI inflows between 2006 and 2017, from USD 187.4 million to USD 1.69 billion (Figure 1.11, Panel A). This strong growth in FDI can be attributed to the government’s Turning Land into Capital (TLIC) (nayobay han din pen theun) policy, which facilitated large concession investment projects (World Bank, 2006[44]) in hydropower (64% of investment in Lao PDR between 2017 and 2021), mining (15% of investment) and agriculture (6% of investment) (Figure 1.11, Panel B). The amount of FDI as a share of GDP is also considerably higher compared with other ASEAN Member States. Lao PDR’s FDI stock amounts to 80% of GDP. Between 2020 and 2022, FDI inflows to Lao PDR as a share of GDP were three times those of Thailand and almost twice the ASEAN average. China is the main country of origin of FDI in Lao PDR: it accounted for 66% of FDI inflows and for 63% of Lao PDR’s FDI stock in 2021 (IMF, 2023[45]). More recently, FDI inflows into Lao PDR decreased in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020 but remain significant.

Figure 1.11. FDI inflows into Lao PDR have increased impressively since 2006, largely in the country’s natural resources sectors

Source: Panel A: (UNCTAD, 2023[46]), Bilateral FDI database on flows and stocks (database), https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.FdiFlowsStock (accessed on 15 October 2023). Panel B: (IPD, 2021[47]), Statistics (database), https://investlaos.gov.la/resources/statistics/ (accessed on 15 October 2023).

FDI has been an important driver of economic growth in Lao PDR. Between 2006 and 2017, when FDI inflows into Lao PDR grew significantly, annual GDP growth averaged 7.7%. This compares with only 5.4% GDP growth on average in ASEAN, 3.5% in Thailand and 6.3% in Viet Nam. Among ASEAN Member States, only Myanmar experienced higher average GDP growth during this period (8.9%) than Lao PDR (World Bank, 2024[5]). FDI in Lao PDR contributed to economic growth mainly through capital accumulation and the exploitation and export of Lao PDR’s natural resources (OECD, 2017[2]; CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[48]).

However, Lao PDR would benefit from attracting more sustainable investment that advances environmental and social goals. The bulk of FDI inflows into Lao PDR are directed towards natural resource sectors such as mining and hydropower, which are capital intensive and typically create few jobs or business linkages with domestic enterprises. At the same time, these sectors are highly susceptible to generating environmental and social risks if environmental safeguards are not respected. In Lao PDR, large-scale hydropower dams have been associated with negative effects on the environment and local communities. Additionally, as a result of their impact on the scenery and natural sites, power plants and mining developments can also discourage tourism. Agriculture, on the other hand, has been linked to deforestation, soil pollution and land degradation (Sylvester, 2018[49]; Village Focus International/National University of Laos, 2019[50]; CDE/University of Bern/MRLG, 2019[48]).

Key recommendations for harnessing FDI in order to support Lao PDR’s sustainable development

Improving the enabling environment for investment and integrating environmental and social considerations into investment policies could allow Lao PDR to attract more sustainable investment that advances environmental and social goals. This includes investments that create a significant number of good-quality jobs; generate local linkages and spillovers such as technology and skills transfers; contribute to skills development; and adhere to strict environmental and social standards (OECD, 2022[51]). By reducing the cost and complexity of investing in Lao PDR, a better enabling environment for investment could allow more investors to make the additional effort and invest the additional resources required in order to limit the negative social and environmental impacts of their investment projects. Improving the enabling environment first and foremost requires a whole-of-government approach to investment. It also involves improving access to skilled labour and to land, upgrading transport infrastructure, reducing opportunities for corruption, and strengthening the regulatory framework. In addition, it would be important to strengthen the implementation of social and environmental safeguards for investment projects and to more actively advance environmental and social goals through investment promotion policies, tax incentives and a better policy framework for responsible business conduct (RBC).

Improve co‑ordination between different government entities and between the public and private sectors. A whole-of-government approach can facilitate the development of public policies and services for investors that are integrated and correspond to their needs rather than being defined by siloed administrative structures (OECD, 2015[52]). This requires improving inter-institutional co‑ordination and the alignment of strategic objectives and priorities among the different government entities involved in the design and implementation of investment policies in Lao PDR.

Improve the availability of skilled labour through in-house training in private enterprises and the provision of better information on those skills that are in demand in the labour market. Different policies – such as tax incentives for training, for example – could encourage more in-house training by private enterprises. In addition, improved co‑ordination between the private sector, the government and educational institutions could help better align Lao PDR’s educational offering with those skills that are in demand in the labour market. This process could be facilitated through the regular engagement of relevant stakeholders in a dedicated council or committee. Finally, an effective skills assessment and anticipation system could identify the types of occupations, qualifications and fields of study that are currently in demand in the labour market in Lao PDR, or that may become so in the future (OECD, 2019[53]).

Improve institutional capacity and inter-institutional co‑ordination in land administration and management, and accelerate the implementation of the 2019 Land Law. A significant share of land in Lao PDR is not formally registered, and the responsibility for land use management is divided among a large number of institutions (National Assembly, 2019[54]) that lack sufficient co‑ordination (MRLG/LIWG, 2021[55]). This can create challenges for investors in accessing land. While a World Bank project is already in the process of significantly expanding formal land registration (World Bank, 2023[56]), going forward, it would be beneficial to simplify the institutional set-up for land management and to enhance inter-institutional co‑ordination between the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) and line ministries. In addition, in order to ensure clarity for investors on land rights in rural areas that are governed by customary land rights and in state forest areas, it would be important to accelerate the implementation of the 2019 Land Law. Finally, additional reforms to Lao PDR’s legal framework for land rights are required in order to add further clarity to existing legislation on customary land rights and formal tenure documents in relation to state forest land (Derbidge, 2021[57]; Derbidge, 2021[58]; Derbidge, 2021[59]).

Enhance Lao PDR’s capacity for PPP delivery, strengthen infrastructure planning and improve the management of fiscal risks related to PPPs. This could allow for making use of PPPs in order to improve Lao PDR’s transportation infrastructure in the long term. In order to improve the value for money of PPPs, it would be important to strengthen Lao PDR’s capacity to prepare, procure and manage PPP projects. In order to ensure that those projects with the greatest benefits are implemented first, Lao PDR requires a medium- to long-term infrastructure plan, including a pipeline of infrastructure and PPP projects with clear prioritisation based on a cost-benefit analysis. In light of the negative impact that past PPPs have had on public finances in Lao PDR, which account for almost one-half of the country’s PPG debt stock, it would also be important to improve the management of PPP-related fiscal costs and risks throughout the project life cycle. Allowing for effective risk sharing with private investors requires reducing the country’s high amount of public debt (OECD, 2017[2]; OECD, 2012[60]).

Improve the predictability of the regulatory framework for investment and the effectiveness of the court system while introducing policy tools that promote integrity among public officials. Gift-giving and informal payments, both on a small scale and in order to buy political support, can affect the efficiency of enterprises operating in Lao PDR (GAN Integrity, 2020[61]; ECCIL, 2022[62]). In order to reduce opportunities for corruption, first and foremost, Lao PDR requires a more stable, clearer, more predictable and more consistently applied regulatory framework for investment and an effective, impartial and independent court system. An effective public procurement system that disburses public funds sustainably and efficiently is another critical element (OECD, 2015[52]). In addition, improved human resource management, training and counselling could enhance the integrity of lower-ranking public officials in Lao PDR. Integrity tools and mechanisms in high-risk areas such as conflict of interest and lobbying, as well as political whistle-blower mechanisms, could also enhance public officials’ integrity (OECD, 2015[52]).

Simplify Lao PDR’s institutional and regulatory framework for starting an investment project. A large number of institutions are involved in this process, and there are three different avenues for obtaining an investment licence, depending on the sector and type of investment. Combining the responsibility for issuing investment licences for different types of investments under the umbrella of a single institution and reducing the number of institutions involved in the allocation of investment licences could speed up the licensing process, enhance efficiency, increase transparency and solve co‑ordination problems between entities.

Strengthen the implementation of social and environmental safeguards for investment projects. Lao PDR’s Law on Investment Promotion contains detailed social and environmental obligations for investors. In addition, two types of environmental impact studies exist in Lao PDR, and environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are mandatory for most investment projects. However, it has been reported that EIAs are treated as just a formality, with limited follow-up or impact on project design. In addition, the monitoring and inspection of environmental obligations could be improved.

Develop more sophisticated and better targeted policies, activities and tools for investment promotion, which should include a greater focus on environmental and social sustainability. Lao PDR would benefit from a clear and coherent inward investment promotion strategy that articulates the government’s vision on the contribution of investment towards environmental protection and social development. More targeted investment promotion efforts, including investor targeting and lead generation, could attract greater investment in Lao PDR’s nine priority sectors, many of which advance social and environmental goals. It would also be important to introduce more key performance indicators (KPIs), both for selecting priority investments and for monitoring and evaluating the activities of the Investment Promotion Department (IPD) of the MPI, including KPIs linked to the environmental and social impacts of investment projects. Finally, in order to allow the IPD to develop these tools and activities, it would be beneficial to gradually endow it with more and better human and financial resources, as well as technical and managerial skills.

Increase positive spillovers from SEZs to the local economy and improve SEZs’ social and environmental performance. Investment in Lao PDR’s SEZs has increased impressively since 2014. SEZs can facilitate access to land for investors in Lao PDR and offer spaces for policy experimentation. They can generate FDI, create jobs, contribute to economic diversification and upgrading, and allow for the transfer of knowledge, technology and skills. However, SEZs also generate costs, including administrative costs, forgone tax revenues as a result of tax incentives, and the cost of resettling local communities. Potentially significant profits earned by SEZ developers combined with discretion in granting approval for new SEZs could also create opportunities for rent seeking. Lao PDR could increase the positive impacts and spillovers from SEZs to the local economy through the right policy and regulatory mix, by encouraging local business linkages, and through skills development. At the same time, comprehensive and strategic planning of SEZ development could reduce opportunities for rent seeking. There is also scope to improve the regulation of the social and environmental aspects of SEZs in order to limit their negative effects on the environment and local communities.

Redesign tax incentives to be based on expenditure rather than income and to more actively advance social and environmental goals. A good enabling environment is more important for attracting and retaining investors than generous tax incentives are. While investment tax incentives can be complementary to a good enabling environment for investment, Lao PDR could consider phasing out the use of income-based incentives in favour of expenditure-based incentives, such as accelerated depreciation and tax allowances or credits. Income-based tax incentives generally attract investments that are already profitable early in the tax relief period, while expenditure-based tax incentives reduce specific costs, thereby encouraging investments that might not occur without the incentives. In addition, incentives should be designed to encourage positive spillovers to the economy and society, such as local linkages, training and skills development, and environmental protection. Incentives for investors that offer training could potentially contribute to bridging Lao PDR’s skills gap. It would also be important to reduce discretion in the allocation of incentives for concessions, which creates avenues for corruption, and to improve the monitoring and evaluation of investment tax incentives.

Intensify efforts aimed at promoting and implementing international RBC and due diligence standards in the local context. First and foremost, this includes developing an institutional and policy framework for RBC, including a special dedicated RBC body or government focal point and a national RBC policy or action plan. RBC efforts should also be incorporated more systematically into investment promotion activities. In addition, homegrown RBC programmes targeted at specific high-risk industries, such as the mining, hydropower and agricultural sectors, could be developed in order to raise awareness and encourage the implementation of due diligence in business practices. Lao PDR would also benefit from better access to remedy and grievance mechanisms for addressing the negative impacts of investment projects (particularly the environmental and social impacts). RBC for concession investments could be improved through including stronger safeguards in concession agreements and making these agreements public.

Opportunities to unlock green and climate financing as a result of strengthened environment statistics