Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) faces the significant challenge of raising its tax-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio, which remains too low despite substantial growth in per capita incomes. As a result, and without reform, Lao PDR will miss its 2025 tax revenue target. While tax policy cannot be examined in isolation from the country’s challenging macroeconomic setting, Lao PDR needs to change its approach to designing, administering and evaluating the tax system. This requires reconsidering many tax design features, such as overly generous investment tax incentives. There is also a lack of tax policy coherence across the enacted policies, and overall tax compliance remains low. In the future, the tax system should play a larger role in promoting formalisation. High-quality tax policy analysis will also be necessary in order to enact tax reforms and raise sufficient tax revenues while also promoting sustainable economic development.

Multi-dimensional Review of Lao PDR

4. Generating sustainable fiscal revenue

Abstract

Lao PDR’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains stuck at a level that is too low to support development despite significant economic growth

Tax revenues are low and not “buoyant”

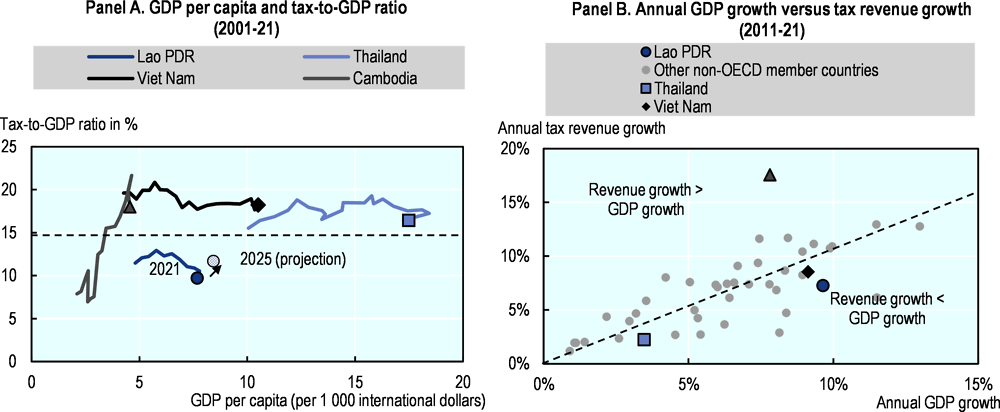

The tax system in Lao PDR mobilises too little revenue to support economic development; in fact, the country’s tax-to-GDP ratio has been declining, despite significant economic growth. Tax revenues were equal to 9.7% of GDP in 2021, lower than in 2010 (11.5%) and 2015 (12.6%). In fact, the tax-to-GDP ratio declined every year between 2015 and 2020, which suggests that the downward trend is not purely due to the COVID‑19 pandemic (OECD, 2023[1]).1 The decline in the tax-to-GDP ratio reflects a lack of tax revenue “buoyancy”. While Lao PDR recorded rapid economic growth over the past decade, with real per capita income growing by around 62% between 2010 and 2020, this economic growth did not result in an increase in the tax-to-GDP ratio. Tax revenue buoyancy refers to a state in which tax revenues grow faster than GDP on average, generating more resources and a higher tax-to-GDP ratio as a country develops (see Box 4.1).2

A low revenue buoyancy is the result of how the tax design, tax enforcement and tax policy in a country interact with the behaviour of taxpayers when the economy grows (or declines). For example, a well-enforced progressive tax system typically contributes to revenue buoyancy because taxpayers pay a higher marginal tax rate when incomes grow and a lower marginal rate when incomes decline. This chapter identifies a large number of features in the Lao PDR tax system that contribute both to low tax revenues and to the lack of tax buoyancy. Low revenue buoyancy can also be caused by revenue-reducing tax reforms that are positively correlated with economic growth. If a country tends to lower taxes discretionally in times of economic growth, as has been the case in Lao PDR, the buoyancy of tax revenue declines.

Revenue buoyancy has been sluggish in other countries in the Southeast Asian region as well, with the exception of Cambodia (Figure 4.1, Panel A). However, countries like Thailand and Viet Nam already mobilise a much higher tax-to-GDP ratio and enjoy a higher GDP per capita than Lao PDR. This leaves their governments with significantly more resources, although domestic resource mobilisation and re-establishing tax buoyancy are among those countries’ policy goals as well. Lao PDR stands out because it simultaneously exhibits a very low tax-to-GDP ratio and a low tax buoyancy (Figure 4.1, Panel B). Only three countries in the OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database recorded a lower tax-to-GDP ratio in 2020: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria.

Without reform, Lao PDR will miss its 2025 tax revenue target

Lao PDR requires buoyant tax revenues if the country wants to meet its own 2025 revenue target. According to its 9th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan (2021-2025) (NSEDP) (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[2]), Lao PDR aims to increase its tax-to-GDP ratio from 11.05% in 20203 to 14.0% by 2025 (i.e. by 2.95 percentage points). Buoyant tax revenues can indicate that it may be sufficient for a developing country to maintain its current tax policy path because future GDP growth will result in a growing tax-to-GDP ratio. This is not the case in Lao PDR. On its current path, with a declining tax-to-GDP ratio despite economic growth, Lao PDR will fail to meet the revenue targets set in its NSEDP.

Projections by the World Bank suggest that Lao PDR may see a slight increase in its tax-to-GDP ratio until 2025 (World Bank, 2023[3]). The tax-to-GDP ratio also rebounded slightly in 2021 from its absolute low in 2020 (from 9.17% to 9.7%) (OECD, 2023[1]). However, without additional measures, the country will fall short of the goals stated in its NSEDP. In addition, the increase in its tax-to-GDP ratio predicted by the World Bank would result in a slow return to Lao PDR’s previous revenue ratio levels (which reached a peak of 12.9% in 2015) but would fall significantly short of the government’s tax revenue target, let alone sustainably raise the revenue ratio to levels observed in neighbouring countries.

Figure 4.1. Evolution of tax revenue and GDP in Lao PDR and peer countries until 2021

Note: Tax-to-GDP ratio and GDP per capita (purchasing power parity) paths until 2021. The lines in Panel A represent values prior to 2021. The dots refer to the value for each country in 2021. The dashed line in Panel A represents the revenue target that the Lao PDR government specified in the NSEDP (14%). Light grey dots in Panel B represent other non-OECD member countries with available revenue data in the OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database as of August 2023. Annual growth rates in Panel B correspond to the compound annual growth rate of nominal values between 2011 and 2021.

Source: Tax-to-GDP ratio and GDP per capita paths until 2021. The lines represent values prior to 2021. The dots refer to the value for each country in 2021. The dashed line represents the revenue target that the Lao PDR government specified in the NSEDP (14%).

Source: (OECD, 2022[4]), Revenue Statistics 2022: The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues; (OECD, 2023[1]), Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2023: Strengthening Property Taxation in Asia; GDP data from (IMF, 2023[5]), World Economic Outlook Database (accessed on 5 September 2023); (World Bank, 2023[3]), Lao PDR Economic Monitor; (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[2]), 9th Five-Year National Socio-Economic Development Plan 2021-2025.

Peer countries raise more tax revenue in proportion to GDP

The Lao PDR government’s tax revenue target of 14% of GDP for 2025 (i.e. an increase by about three percentage points between 2020 and 2025) appears moderate compared with the revenue-raising capacity of peer countries. In 2021, the average tax-to-GDP ratio for the Asia-Pacific region (out of the 27 countries in the region that report to OECD Revenue Statistics) stood at 19.8%. With a tax-to-GDP ratio of 9.7% in 2021, Lao PDR’s tax-to-GDP ratio was more than ten percentage points below that average and was the lowest in the region. When Viet Nam had income per capita levels comparable to those of Lao PDR in 2022, its revenue ratio was significantly greater than Lao PDR’s. Cambodia, despite lower income levels, already mobilises a larger share of GDP in tax revenue than Lao PDR.

Box 4.1. Tax revenue buoyancy as a tool to evaluate the tax system’s response to growing incomes

Alongside tax revenue elasticity, tax revenue buoyancy is one of the key measures that captures the sensitivity of government revenue to economic activity. For instance, an overall tax revenue buoyancy of 1.2 suggests that when GDP grows by 1%, total tax revenues would be expected to grow by 1.2%. Buoyancy thus captures the total response of tax revenues to changes in GDP, including the impact of tax policy changes. In contrast, revenue elasticities control for tax policy reforms in order to isolate the impact of economic growth on tax revenue (i.e. in the absence of policy changes). If the tax revenue buoyancy is greater than 1, tax revenues in a country are “buoyant”, which implies that tax revenues tend to grow faster than GDP.

Buoyant tax revenues indicate that it could be sufficient for a developing country to maintain its current tax policy path because future GDP growth will likely result in a growing tax-to-GDP ratio. A tax revenue buoyancy between 0 and 1 suggests that tax revenues tend to increase when a country’s GDP grows, but revenues grow at a slower pace than GDP. Note that this results in a declining tax-to-GDP ratio, which is a particular problem in developing country contexts where tax-to-GDP ratios are already low. A negative tax buoyancy implies that tax revenues in absolute terms decline if a country grows its GDP.

The short- and long-term tax revenue buoyancy can be estimated empirically based on historical revenue and growth data (Cornevin, Corrales and Angel, 2023[6]; Belinga et al., 2014[7]). In addition to assessing the responsiveness of overall tax revenue, the analysis can also be conducted separately by tax type. For example, corporate income taxes are known to have a higher short-term tax buoyancy than other taxes, as profits are volatile and linked to the economic cycle. Tax buoyancy estimates can also be used to compare the actual responsiveness of tax revenues in one year with the expected change in tax revenues according to the historical tax revenue buoyancy (OECD, 2022[8]). A recent study finds a small difference between the tax revenue buoyancy and tax revenue elasticity for the average country, suggesting that tax revenue buoyancy estimates are mostly not driven by discretionary tax policy changes (Cornevin, Corrales and Angel, 2023[6]).

Another recent study estimated that the long-term tax revenue buoyancy in Lao PDR is 1.2 (Hill, Jinjarak and Park, 2022[9]). This is despite the fact that the tax-to-GDP ratio in Lao PDR was lower in 2022 than it was in 2010 (the earliest year for which tax revenue data are available in the OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database). Empirical tax revenue buoyancy estimates for developing countries can be misleading if they are based on historical tax data that date too far back in time. Using the relationship between economic growth and tax revenue as far back as the 1980s in order to estimate a tax buoyancy coefficient in a developing country with rapid economic growth in recent years results in estimates that need to be interpreted with care. A high tax buoyancy coefficient could also emerge if tax revenues and GDP fluctuate strongly from year to year – for example, due to changes in commodity prices (if the country is highly commodity dependent), due to a very low GDP and tax revenue (which magnify year-to-year percentage changes) or due to inaccuracies in measurement.

The lack of tax revenue buoyancy analysed in this chapter refers to the fact that the tax-to-GDP ratio in Lao PDR has not increased (and has actually declined recently) despite the country’s rapid economic growth.

Not only would increasing the buoyancy of the tax system in Lao PDR help the country achieve its 2025 revenue target but it would also establish a positive link between economic growth and government finances for the future. Countries with a higher income generally find it easier to increase tax revenue as a percentage of GDP, and a buoyant tax system generates extra tax resources exactly when income growth is rapid. It has also been suggested that once tax revenues as a share of GDP surpass a certain minimum tipping point – a sign of higher state capacity – a country can expect faster economic growth for several years (Gaspar, Jaramillo and Wingender, 2016[10]). The effect could be even stronger if the additional revenue is invested in initiatives that promote growth in the long term.

However, history also indicates that even with positive revenue buoyancy, raising the tax-to-GDP ratio by five percentage points over a decade is a challenging task but there are examples (Gaspar et al., 2019[11]) (Box 4.2). This is particularly true in Lao PDR, which needs to address a large number of other development challenges in addition to raising more tax revenue. Assuming a 4% real annual income growth rate, an absolute tax revenue increase of more than 50% would be necessary in order to increase the tax-to-GDP ratio from 11.05% to 14% within five years. It is important to ensure that raising more tax revenue does not unduly compromise progress towards other development goals.

Box 4.2. Colombia has increased its tax-to-GDP ratio through a number of tax reforms

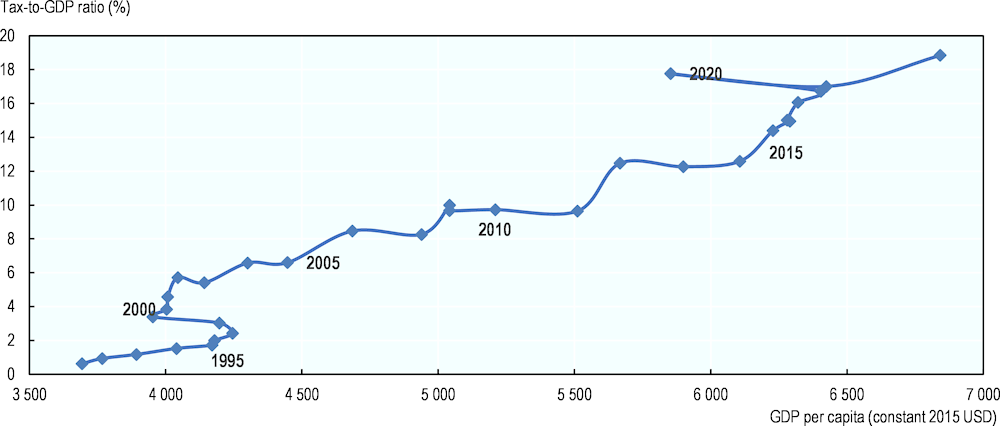

Starting from a low tax-to-GDP ratio, Colombia has made considerable efforts to broaden its tax bases, raise tax rates and stimulate voluntary compliance. Between 2000 and 2022, Colombia’s tax-to-GDP ratio increased from 3.8% to 18.8% (Figure 4.2). In 2012, Colombia implemented a tax reform that reduced the tax burden on labour. The reform aimed to strengthen the formal economy by reducing SSCs in order to finance social expenditure from general tax revenues, including the National Alternative Minimum Tax (IMAN) and Alternative Simplified Mínimum Tax (IMAS). The tax reform reduced the number of VAT rates from 15 to 3 and introduced electronic invoicing. Simultaneously, the capital gains tax was lowered significantly, from 33% to 10%.

Figure 4.2. With economic development, Colombia managed to increase its capacity to collect taxes

Source: (World Bank, 2024[12]), World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

In 2016, following recommendations from a group of experts, Colombia reformed its tax system in order to increase tax revenue. The revenues generated from the 2016 tax reform helped protect social spending while achieving the country’s structural deficit target. This reform involved raising the VAT rate from 16% to 19%, comprehensively streamlining the tax code, alleviating the high corporate tax burden and implementing measures to enhance formalisation and tax administration. The reform mandated electronic invoicing for real-time transaction monitoring and introduced general anti-avoidance rules.

Colombia undertook tax reforms in 2019, 2021 and 2022 with the aim of enhancing the progressivity of its tax system while also focusing on increasing tax transparency and information. Beneficial ownership rules were introduced, and the tax administration was strengthened in terms of both information technology and human resources. Improved tax audits, supported by information sources like ultimate beneficial data and electronic invoicing, aimed at building taxpayer confidence. Since 2022, the tax administration sends personalised emails to individuals who file personal income tax returns to explain how their taxes will be used.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD Mutual Learning Group meeting on 29 February 2024 and (IMF, 2023[13]), Article IV Consultation Report.

The link between economic growth and tax revenue generation is too weak in Lao PDR

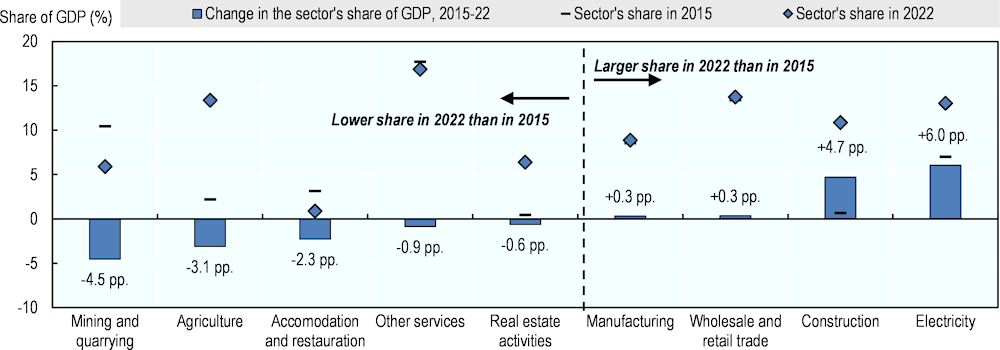

The low tax revenues and low tax revenue buoyancy in Lao PDR can be traced back to how the tax system interacts with economic growth. Economic sectors that have experienced above-average growth over the last years, such as the construction or electricity generation sectors, are particularly prone to not raising adequate revenue (Figure 4.3). This is linked to the approach that Lao PDR has decided to follow in order to try to grow its economy and attract investment. Rather than working towards a consistent and reliable standard tax system, which would provide potential investors with a stable environment for investing and doing business, the country tends to further expand its web of tax incentives, special rules and untransparent agreements with individual investors.

For example, large-scale hydropower projects regularly benefit from project-specific agreements that exempt the enterprises carrying out the projects from corporate income taxes or withholding taxes for many years, among other tax concessions. In some instances, the payment of these taxes is replaced by a lump-sum amount that the developer can transfer to the government. Such arrangements not only reduce tax collection, but also dissociate the revenues generated in a given year from the economic activity in that same year. Signing multi-year concession agreements with project developers has significantly reduced the government’s leeway in future years: Tax policy changes that Lao PDR decides to enact now will only affect major enterprises in growth sectors after a considerable delay.4

Widespread informality in the sectors driving economic growth contributes to low revenues as well. The construction sector, a sector with one of the highest levels of informality in Lao PDR (94% informal employment), has increased its share of GDP by almost five percentage points between 2015 and 2022 (Figure 4.3). However, additional employment in the construction sector will generate little additional revenue for the government if new workers are predominantly hired in the informal economy. Other economic activities benefit from permanently reduced corporate income tax (CIT) rates. Sectors with reduced CIT rates are frequently those whose growth the government of Lao PDR wants to stimulate, such as businesses operating in the area of green technologies. In practice, these types of incentives imply that growth in these sectors will not translate into significant revenues for the government.

Figure 4.3. Change in GDP by sector between 2015 and 2022 in Lao PDR

Note: Electricity includes water supply and waste management. ”'PP” refers to “percentage points”.

Source: (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2023[14]), Laos Statistical Information Service (LAOSIS), https://laosis.lsb.gov.la/main.do (accessed on 23 September 2023).

Tax design challenges can be identified across all tax types and across types of economic activity. Table 4.1 provides a stylised overview of features characterising the Lao PDR tax system, which can explain why economic growth does not translate into adequate tax revenue growth. This chapter discusses these and other tax design challenges in more detail and provides concrete tax policy recommendations. However, tax reform in Lao PDR has to go beyond specific tax design changes, and major improvements to the country’s approach to designing, administering and evaluating the tax system are needed as well. Ultimately, Lao PDR needs to identify a set of reforms that gradually increase revenue buoyancy (and raise revenue), while also turning the tax system into a positive force that helps address other developing challenges, such as high inequality, inadequate social protection, high informality or the lack of investment.

Table 4.1. Stylised overview of why economic growth does not result in adequate revenue growth in Lao PDR

|

Even if there is growth in Lao PDR in… |

…it may not translate into much higher tax revenue because… |

…which is a result of… |

|---|---|---|

|

Domestic enterprises’ profits |

Effective CIT rates are low |

Reduced CIT rates being offered in growth sectors (such as green technologies) |

|

Multinational enterprises’ profits |

Profits can be easily stripped out of the country |

The lack of a consistent international taxation framework |

|

The profits of enterprises in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) |

Profits are tax-exempt for many years |

The availability of generous profit-based tax incentives in SEZs |

|

Profits generated in the resource sector |

Effective CIT rates are low or zero |

Generous case-by-case tax incentives being granted to enterprises or consortia carrying out natural resource projects |

|

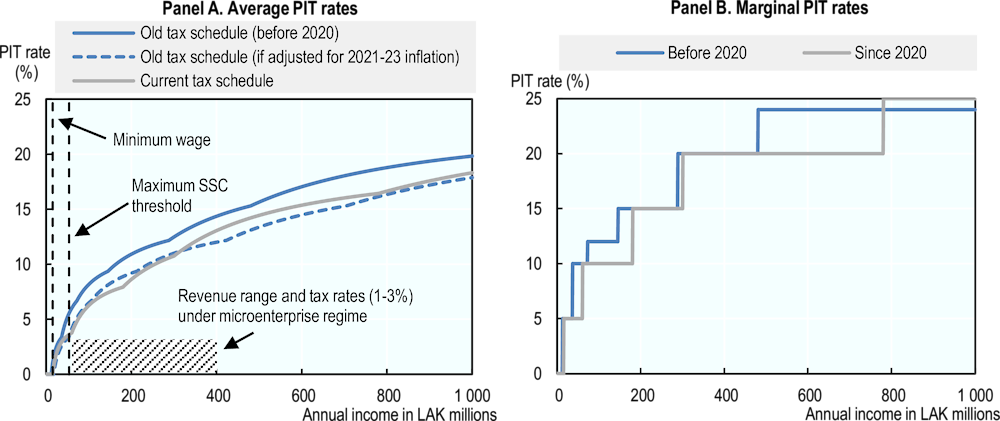

Salaries |

Average personal income tax (PIT)/SSC rates increase little with income |

Only moderately progressive PIT and a low maximum SSC threshold |

|

Capital incomes |

Withholding tax rates are low |

Low capital income taxes and a territorial PIT system |

|

Self-employed business income |

The self-employed are taxed more favourably than salaried workers, and their turnover is potentially under-reported |

Special regimes (e.g. the freelancer regime) and suboptimally designed presumptive tax regimes |

|

Real estate values |

The land tax is not linked to real estate values |

The lack of a mechanism to update land values, and no inclusion of the value of buildings and land improvements in the tax base |

|

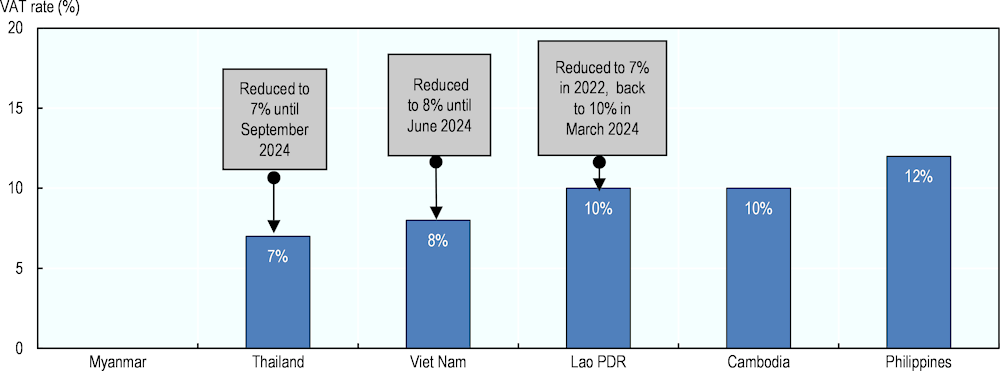

Consumption expenditure |

The VAT efficiency and the standard VAT rate are low |

The high share of informal businesses and a recent reduction in the standard VAT rate |

|

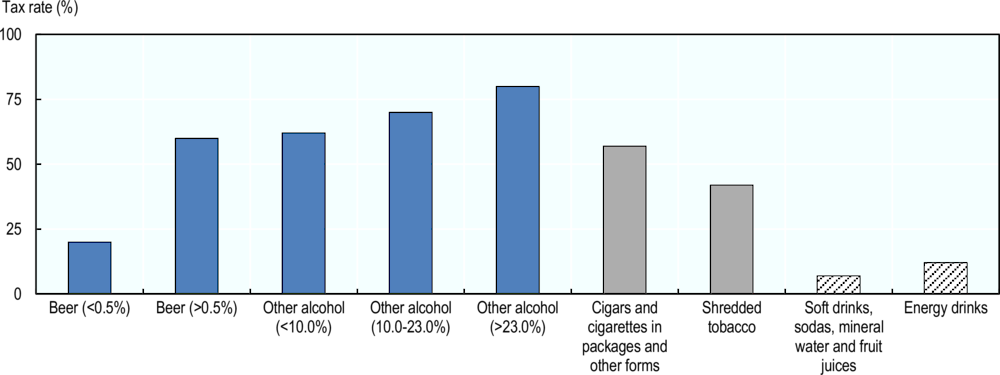

Consumption of harmful products |

Effective health taxes are low, despite increases in statutory rates |

Non-compliance and no consistent health tax policy (e.g. the long-term stability contract with Lao PDR’s leading tobacco producer) |

|

Imports |

A significant share of imports are undeclared |

Complex procedures and a different set of taxes (including a “deemed profits” tax) |

|

Exports |

Exporting businesses pay little CIT (and PIT/SSCs) |

Exporting businesses’ tendency to be located in SEZs |

Note: More details about these tax system design features and reform options are provided in the next section.

The tax policy in Lao PDR cannot be assessed in isolation from the country’s challenging macroeconomic setting and weak social protection system

Current tax revenues are insufficient to finance spending needs

Current levels of tax revenue are insufficient to finance the substantial spending needs that Lao PDR faces, even ignoring the additional revenue needed in order to service the high public debt. One key area requiring significant additional resources is social protection, but more tax revenue is also needed in order to provide quality education or further invest in the country’s infrastructure, which has been overly reliant on debt financing in recent years. Tax revenue mobilisation should be the preferred strategy for generating additional resources because debt financing has reached a limit in Lao PDR, and excessively cutting expenditure would harm the country’s growth trajectory. Only domestic government resources will provide the reliable stream of sizeable revenues that would be independent from other countries’ priorities and that are necessary in order to sustain and further expand public expenditure over the medium and long term. The goal of increasing tax revenue is therefore well-founded, and, in the medium term, tax revenues will likely have to exceed the 2025 target of 14% of GDP.

Financing needs are particularly significant if Lao PDR wants to achieve universal social protection by 2030 because the latest data suggest that the country currently only allocates 1.6% of its GDP to social protection (ILO, 2021[15]). On average, Lao PDR was therefore only able to spend less than LAK 40 000 (Lao kip) per person per month on social protection in 2022 (around EUR 2.0‑2.5 (euros) based on 2022 exchange rates). The Lao PDR National Social Protection Strategy includes the target to provide all Laotian people with access to basic social protection by 2030, including health insurance, social security and social welfare (Government of Lao PDR, 2020[16]). This 2030 target is consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals, but achieving it will require significantly more financial resources, especially if the benefits are adequate.5 The revenue generated from SSCs was equal to around 0.7‑0.8% of GDP in 2019 and 2020 (IMF, 2022[17]). This implies that general government revenues and donor funds had to contribute significantly to social protection expenditure, even at the low levels of such protection observed today.6

The tax system in Lao PDR has not managed to keep inequality in check

Economic inequality is on the rise in Lao PDR, and the tax system has so far been unsuccessful in stopping this trend. Evidence from private household expenditure data shows an increase in the Gini coefficient for Lao PDR from 0.31 in 1992 to 0.36 in 2012, indicating growing inequality in consumption expenditure (Warr, Rasphone and Menon, 2018[18]). More recent estimates point towards a continuation of this trend. Based on the latest edition of the Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey (LECS), the country’s Gini coefficient regarding consumption expenditure reached 0.388 in 2018. At the same time, peer countries in the Southeast Asian region experienced a decline in economic inequality. As measured by the Gini coefficient, inequality in Lao PDR was higher than in Viet Nam (0.357), Thailand (0.364) and Indonesia (0.384) in 2018. New data also suggest a shift in the dominant type of economic inequality in Lao PDR: Inequalities inside provinces and geographical regions – rather than larger gaps between regions – have been the drivers of the latest increases in inequality (World Bank, 2020[19]).

As economic inequality grows and turns into a predominantly within-region phenomenon, the role of the tax and transfer system as a tool for mitigating inequality increases. Broad-scale redistribution from richer to poorer regions cannot address inequalities that exist between individuals within the same city or region. Individual taxes and transfers, on the other hand, have the potential to redistribute income in a targeted way from the rich to the poor regardless of location – but the current tax system in Lao PDR is not well placed to take up that role. In the average OECD member country, the tax and transfer system reduces the level of inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient by 0.1 points (OECD, 2023[20]). Such a large reduction in inequality requires a combination of progressive taxes and targeted benefits. Data on the difference in inequality before and after accounting for tax and transfers are not available in Lao PDR. However, Lao PDR mobilises less than 25% of its tax revenue from personal and corporate income taxes, while consumption taxes make up the majority of tax revenue. The low tax-to-GDP ratio also implies that the fiscal space for redistributive transfers is very limited. In addition, high levels of informality make it difficult for the state to tax those with higher incomes and reach those in need of income support. Other characteristics of the tax system (such as its limited progressivity) imply that high-income earners likely pay little tax. In such a setting, it is not surprising that the current tax and transfer system has not been able to stop the increase in inequality.

Reducing inequality is a target of the NSEDP, but would require significant changes in tax policy and process. Reduction of “inequality in income distribution and consumption” is a stated policy goal in the NSEDP (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[2]). Reducing inequality requires reversing the current trend over the next years, which cannot be expected to happen without tax policy changes. The impact of potential tax reforms on inequality would need to be systematically assessed when Lao PDR decides on future tax policy changes. At a minimum, additional tax revenue mobilisation and enforcement efforts should not come at the expense of the bottom of the income and wealth distribution. However, in a conversation with the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, officials from the Ministry of Finance (MOF) in Lao PDR stated that, as of 2019, inequality did not play any role in the tax policy and budgeting process (United Nations, 2019[21]).

Most workers and firms operate in the informal economy

Only 10‑20% of employment in Lao PDR occurs in the formal economy, and more than 70% of businesses in Lao PDR are not registered (ILO, 2023[22]). Informality is most prevalent in the sectors with the largest workforces, among which are agriculture (in which 98% of workers are informal), construction (94%), and retail and trade (92%). The services (66%) and manufacturing (77%) sectors record the lowest levels of informality. Apart from Cambodia, where informality is similarly high, Lao PDR’s neighbouring countries have managed to bring a larger share of their workforces into the formal labour market. In addition, in Lao PDR, working in the formal sector is not the same as being able to access the national social protection system. Fewer than two out of five formal sector workers (37%) contribute to social security, despite the fact that they (and their employers) are mandated by law to do so (ILO, 2023[22]).

The high level of informality limits the revenue-raising potential of taxes and reduces the reach of the social protection system in Lao PDR. Mobilising a significantly larger share of tax revenue from personal income taxes and SSCs will not be possible if almost 90% of workers remain out of the reach of the tax system. The same applies to business taxes and indirect taxes if most enterprises are not registered. Informality also complicates standard tax policy reasoning because a large number of workers and businesses in Lao PDR effectively operate under a “shadow tax” system in which some rules of the ordinary tax system apply, but not others. For example, informal enterprises do not levy VAT on their sales, but they do pay the tax on some of their inputs without being able to recover it. And as long as enterprises face competition from informal businesses in the same sector, the regular tax system creates incentives for enterprises to remain partially informal, to not register all their workers or to under-report turnover, for example under a presumptive tax regime (World Bank, 2018[23]).

The tax system in Lao PDR is not conducive to business and worker formalisation. Instead, the design of the current tax system contributes to a polarised economy that generates too little revenue for the government. Informal economy workers and enterprises face high uncertainty and no protection, but a low tax burden. Formal workers and enterprises should, in theory, generate tax revenue as per the standard rules of the tax system, but many have developed tools to navigate the system in a way that ensures that their tax burden remains low as well. Large formal enterprises know how to utilise the web of tax incentives, SEZs and discretionary agreements with the tax administration system in order to keep their effective tax burden low. The CIT gap in Lao PDR has been estimated at 90% (World Bank, 2023[3]).7

The current system particularly disadvantages informal enterprises (and their workers) that would like to transition to the formal economy but lack connections, knowledge of the complex rules and the capacity to optimally use tax incentives. There is also evidence that registered enterprises that attempt to pay all taxes according to the rules encounter more scrutiny and are more likely to face charges for minor tax non-compliance than enterprises that are completely informal and not visible to the tax administration system (World Bank, 2017[24]). The result has been described as an “impossible choice” that enterprises in Lao PDR are confronted with: (i) remaining at least partially informal despite the high uncertainty; or (ii) trying to follow the complex set of rules and pay all taxes in full, risking losing out to competitors that remain in the informal economy or that reduce their tax burden through other means (World Bank, 2017[24]).

Mobilising additional tax revenue in Lao PDR thus needs to happen in parallel with efforts to further encourage the formalisation of the economy. Well-designed presumptive tax regimes can be a tool to stimulate formalisation while also gradually increasing tax revenues (Mas-Montserrat et al., 2023[25]). Although Lao PDR has made progress in redesigning its presumptive tax regimes, there is scope for further improvement. Any other tax policy change under consideration in Lao PDR needs to be assessed with regard to its impact on informality as well. It is also crucial that the social protection system is functional and is seen as providing adequate benefits of sufficient quality to encourage workers and their employers to register. The aftermath of the COVID‑19 pandemic could be a good time to capitalise on the experiences of workers and businesses during the health crisis. Certain transfers during the COVID‑19 pandemic were only available to registered workers and enterprises, which may have increased the salience of the benefits delivered by the social protection system that were accessible only to formal workers and enterprises (UNESCAP, 2021[26]).

Lao PDR’s economy is in a vulnerable state, making tax policy changes both necessary and difficult to implement

Lao PDR faces a multitude of acute macroeconomic challenges that create additional challenges for tax policy. The Lao kip depreciated by around 50% against the United States dollar and more than 40% against the Thai baht between December 2021 and December 2022 (IMF, 2023[27]). Inflation averaged 23% in 2022, and year-on-year inflation stood at 28.6% in June 2023, according to official Lao PDR government statistics (Lao Statistics Bureau, 2023[14]). The debt-to-GDP ratio (including publicly guaranteed debt) stood at 112% at the end of 2022 (Lao PDR Ministry of Finance, 2023[28]), which is very high in international comparison given the low amount of tax revenues that the country raises. There is a lack of transparency on the total amount of debt and its creditors, and the country faces hurdles to borrow on the international capital market. The following macroeconomic challenges will further complicate tax policy in the coming years:

Addressing these acute debt-servicing challenges will bind tax revenue and require additional revenue if large spending cuts are to be avoided. A credible debt-servicing and repayment plan needs to be developed that will increase transparency and reduce government debt to a sustainable level.

Lao PDR’s large debt-servicing obligations could potentially make it more difficult for the country to pass revenue-raising tax reforms because taxpayers may be less willing to pay taxes if the revenue is used to service debt, which would otherwise be deferred.8 Ensuring that economic growth translates into higher tax revenues – not only in total amounts but also as a percentage of GDP – is a crucial element of a strategy that puts government debt on a sustainable downward trajectory.

Inflation has eroded the net income of a large share of the population, and there has likely been an uptick in poverty (World Bank, 2023[3]), which reduces the ability of lower- and middle-income taxpayers to pay for additional tax increases.

High inflation may prompt Lao PDR to consider indexing tax brackets and other key parameters for inflation, although less than full indexing for inflation would result in a gradual increase in tax revenues.

Due to its exceptionally low tax-to-GDP ratio, Lao PDR also requires a strategy to navigate the trend in the Southeast Asian region of reducing tax rates such as the VAT or CIT. Continuing to move along with these tax reductions would create considerable additional challenges for Lao PDR.

These acute macroeconomic challenges come in addition to already existing structural economic vulnerabilities with implications for tax policy. For example, human capital development has been weak in Lao PDR, and a large number of workers (both low and high skilled) have left to work in neighbouring countries (ILO, 2023[29]). Lao PDR must balance its need to increase revenue in order to invest in human capital development with ensuring that the tax burden on labour does not become so great that it encourages more skilled workers to leave the country. Lao PDR is surrounded by richer neighbours that offer higher-paid jobs and better social protection. Thailand’s minimum wage, for example, is three times higher than the minimum wage in Lao PDR (ILO, 2023[29]).9 It is estimated that almost 1.3 million Laotians have left the country (which has a population of 7.5 million) to live abroad. As of 2020, more than 70% of these migrants were living in Thailand (UN/DESA, 2020[30]). While remittances constitute an important source of income (around 1‑2% of GDP), Lao PDR will not be able to grow its economy sustainably without a skilled domestic workforce and without ensuring that skilled workers find good-quality jobs that pay well. Lao PDR’s young population has the potential to do this – around 50% of the population in Lao PDR is aged under 25 years – but investment in training and skills development for this population is essential (UN/DESA, 2022[31]).

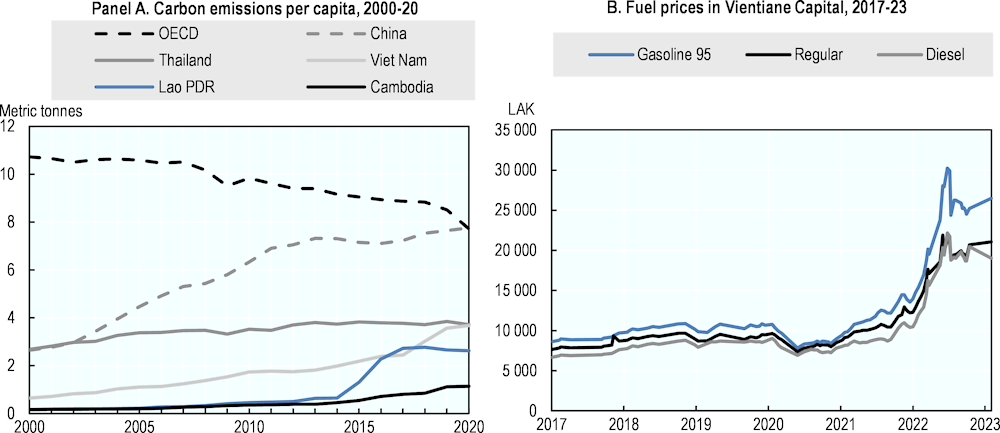

Environmental degradation comes at a large economic and societal cost, and the tax system has a stronger role to play in safeguarding the environment and ensuring that economic growth is sustainable.10 Estimates suggest that forest loss alone caused annual damage to Lao PDR’s economy equal to 3% of its GDP (World Bank, 2021[32]). Often, these activities take place either illegally or within the informal sector, implying that both wider society and the government miss out on potential economic benefits. Industrial mining has also frequently failed to create employment opportunities for local communities. Large foreign investors have tended to bring their own workforces and expertise, while the local population remained reliant on agriculture and small-scale mining.11 Air pollution, lead exposure and water contamination have started to severely affect local communities and their economic prospects. A reduction in the levels of rainfall caused by climate change may threaten the revenue generated by hydropower dams (Spalding-Fecher, Joyce and Winkler, 2017[33]). In order to combat this, the government of Lao PDR introduced the National Green Growth Strategy of the Lao PDR until 2030 in 2018, aspiring to shift the country’s economic growth model away from environmentally detrimental activities. The tax system needs to play a central role in this shift by: (i) ensuring that society benefits in the form of tax revenue when natural resources are exploited; (ii) mitigating environmental damage; and (iii) steering the economy towards a more sustainable growth model.

Further economic growth will be necessary in order to finance Lao PDR’s spending requirements

Neither reprioritising expenditure nor mobilising a higher share of GDP through tax revenues will ultimately be sufficient to meet the spending needs that Lao PDR faces. In 2022, even a tax-to-GDP ratio of 50% would have resulted in tax resources of only around LAK 1.2 million per person per month (around EUR 60 based on 2022 exchange rates).12 This figure still seems insufficient to finance pensions, high-quality healthcare, education and infrastructure, as well as to meet the cost of all other government transfers and operations. Despite rapid economic growth over the last decades, it is clear that there is a need for Lao PDR and its tax system to stimulate further economic growth in order to be able to meet the country’s spending needs.

In addition to raising more revenue, the tax system must actively contribute to promoting economic development while also helping to reorient the economy towards a new economic growth model that is less dependent on natural resources. Lao PDR wants to expand its economy through growth in the transportation, tourism, electricity generation, higher-value agricultural and manufacturing sectors, along with deepening its integration into the ASEAN community (Government of Lao PDR, 2021[2]). Currently, Lao PDR attempts to attract investment primarily through very generous tax incentives in order to compensate for a suboptimally designed and enforced standard tax treatment. Although the country’s economy has been growing rapidly, this chapter identifies ways in which the tax system could play a more active and efficient role in strengthening sustainable investment in particular.

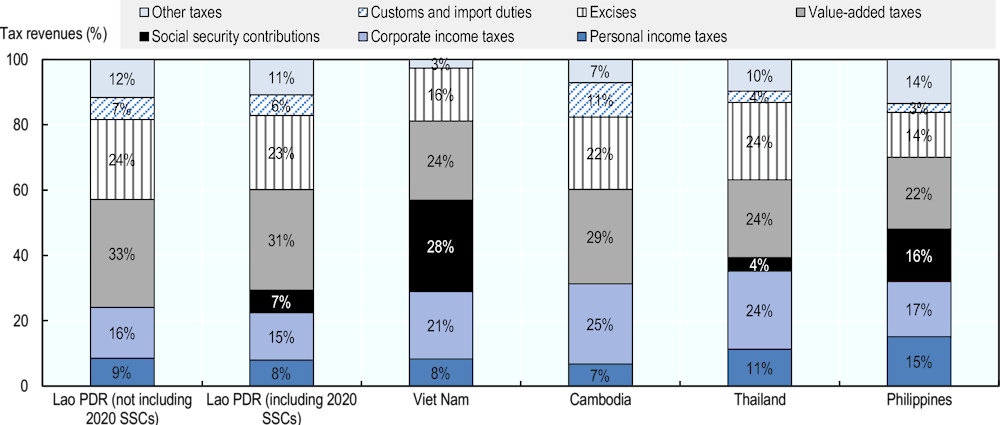

Lao PDR relies heavily on indirect taxes

VAT and excise duties play an outsized role in the tax mix, while revenue raised through personal and corporate income taxes is particularly low

Lao PDR currently relies heavily on revenues from taxes on goods and services, with scope for improvement. Notable revenue sources are the VAT (33% of tax revenue), excise duties (24% of tax revenue) and import duties (7% of tax revenue). In every year between 2011 and 2021, taxes on goods and services made up 70‑80% of total tax revenue in Lao PDR, with a peak of 78.1% in 2020. It is not unusual for indirect taxes to play a significant role in developing countries, but the combined contribution of personal and corporate income taxes is particularly low in Lao PDR. Revenues from SSCs, which are directly paid to the social security fund, are systematically excluded from tax revenue statistics in Lao PDR. However, even if these revenues were included in the tax mix, the combined share of personal income taxes, SSCs and corporate income taxes would increase only slightly (Figure 4.4). There is scope to improve the functioning of the VAT in Lao PDR, notwithstanding its large contribution to tax revenues. The VAT should be aligned with the International VAT/GST Guidelines (OECD, 2017[34]).

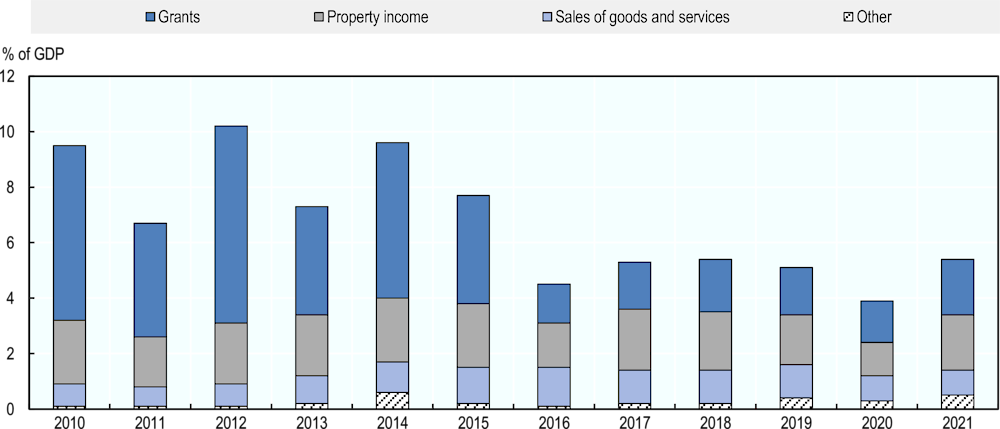

The government also collects significant non-tax revenues, notably through grants and property income. Property income predominantly includes income streams linked to the resource sector, such as government royalties (Figure 4.5). However, property income as a share of GDP is rather low, at around 1‑2%. Lao PDR does plan to reduce its resource dependence, which will ultimately also reduce resource-related government revenues. Lao PDR should make good use of resource-related revenues and ensure fiscal gains from resource rents, but the resources required to satisfy its spending needs will ultimately have to be delivered by the regular tax system. Revenue sourced from grants may eventually decline when Lao PDR graduates from the UN’s list of least developed countries (LDCs) and as its per capita income continues to grow.

Figure 4.4. Tax revenue mix in Lao PDR and peer countries in 2021

Note: Lao PDR includes 2020 SSC revenue as recorded in IMF (2022[17]) Technical Assistance Report on Government Finance Statistics Mission.

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2023: Strengthening Property Taxation in Asia, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/revenue-statistics-in-asia-and-the-pacific-5902c320-en.htm; (OECD, 2024[35]), Global Revenue Statistics Database, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/global-revenue-statistics-database.htm (accessed on 23 September 2023).

Figure 4.5. Non-tax revenue in Lao PDR between 2010 and 2021

Note: “Property income” includes royalties, natural resource taxes, and interest and dividend income of the government. “Sales of goods and services” includes sales by market establishments, administrative fees, incidental sales by non-market establishments, and imputed sales of goods and services.

Source: (OECD, 2024[35]), Global Revenue Statistics Database, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/global-revenue-statistics-database.htm (accessed on 5 September 2023).

A large number of tax design features contribute to low tax revenues and to the lack of tax buoyancy and progressivity

Tax incentives in SEZs are overly generous and not optimally designed

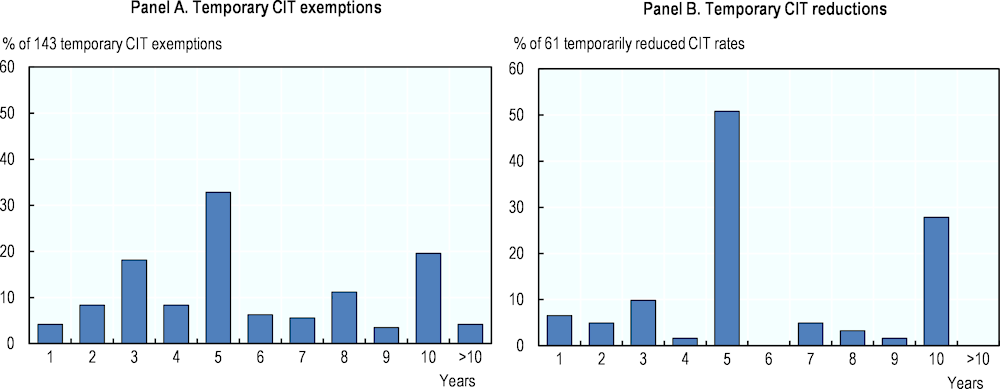

The growing presence of SEZs in Lao PDR means that the government collects little tax revenue from large formal enterprises whose activities would be the easiest to monitor and tax. Tax benefits granted in SEZs in Lao PDR are extremely generous, their design does not conform to best practice and they excessively undermine revenue mobilisation. While there is a strong rationale to have SEZs in Lao PDR, in particular because of the broader governance challenges in the country’s main economy, the government should avoid the use of overly generous tax incentives in SEZs. For example, the duration of the CIT exemption in SEZs in Lao PDR (6‑17 years) is longer than the average in other emerging and developing economies (Figure 4.6).

Lao PDR has designated a total of 21 SEZs in 7 provinces over the last 20 years, and these provide investors with multiple tax reductions. The types of economic activities that can be performed in SEZs, and which therefore benefit from preferential tax treatment, are very broad and not limited to manufacturing or industrial work. Indeed, there are SEZs that target investment in office buildings, residential complexes, hospitals, schools, golf courses, hotels, shopping centres and logistics centres. A prime example is the That Luang Lake SEZ, an upscale urban development project located in the heart of Vientiane, Lao PDR’s capital city, in which all buildings and operations fall under the SEZ designation. Outside Vientiane, SEZs are typically located near the border with neighbouring countries such as Cambodia, the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), Myanmar or Thailand.13

Although the exact incentives provided can vary by SEZ and type of business, tax incentives available to investors in SEZs can include:

exemption from CIT for 6‑17 years and, for example, a 65% reduction in CIT payments for the 5 years following that exemption period14

a VAT rate of 0% on the import of materials for developing the SEZ and a VAT rate of 0% on other imports into the SEZ, which could include construction materials, machinery, raw materials or minerals (from abroad or from businesses registered in the domestic economy)15

exemption from land and property sales tax

a minimum 50% reduction in VAT paid on electricity and water supply

a cap on the marginal PIT rate at 5%.

Tax incentives must be well designed and combine investment attraction with minimal tax revenue loss, safeguarding public financial resources. Tax incentives often play a role in attracting foreign investment, they are usually not the primary determinant for businesses deciding whether to invest in a developing country (Blomstrom and Kokko, 2003[36]). Other factors – such as the stability of the political and economic environment, the quality of the infrastructure, access to local and regional markets, the availability of skilled labour, and regulatory clarity – often weigh more heavily in the decision-making process. These elements contribute to the overall investment climate and are vital in ensuring that an enterprise can operate efficiently and profitably. Although tax incentives can lower the cost of doing business, they do not necessarily offset weaknesses in these other areas. To the contrary, by reducing tax revenues, incentives can undermine the ability to invest in improving them. Tax incentives therefore need to be targeted and properly designed in order to be effective at attracting investment while minimising tax revenue losses.

Figure 4.6. Duration of CIT reductions according to the OECD Investment Tax Incentives Database

Note: The OECD Investment Tax Incentives Database collects information about investment tax incentives in 52 emerging and developing economies (including Lao PDR). See (Celani, Dressler and Wermelinger, 2022[37]) for definitions. Based on information on 52 economies and 467 CIT incentive entries.

Source: Figure 1, Panel F in (OECD, 2022[38]), OECD Investment Tax Incentives Database – 2022 Update: Tax incentives for sustainable development (brochure) (accessed on 5 September 2023).

Lao PDR needs to rethink its tax incentive strategy in SEZs, shifting its focus away from profit-based incentives and towards expenditure-based ones. This would better target incentives while minimising revenue loss. Profit-based tax incentives, such as an exemption from CIT, provide tax benefits as a function of business profits. These types of incentives are heavily used in developing countries, in particular in SEZs (Celani, Dressler and Wermelinger, 2022[37]). Expenditure-based tax incentives, on the other hand, are tied to the amount of investment that businesses make in Lao PDR. They can come in various forms, including investment tax allowances, investment tax credits, or methods of quicker cost recovery, such as accelerated depreciation or immediate expensing.

Expenditure-based tax incentives offer several advantages compared with profit-based incentives, as follows:

Profit-based incentives contribute to a low revenue buoyancy. This is because even highly profitable enterprises that contribute to economic growth do not generate any (or only generate very little) tax revenue. Expenditure-based incentives ensure that tax revenues increase when profits grow. Under expenditure-based incentives, profitable enterprises also start paying tax earlier than those that are not profitable.

Expenditure-based incentives limit tax revenue loss because the government can set a maximum for an investment credit or allowance. Strategies such as accelerated depreciation or immediate expensing merely delay tax collection to the future, maintaining the actual tax payment. They only provide enterprises with the net present value difference that comes from making a deferred tax payment. In contrast, profit-based incentives lack such a built-in limit to potential tax revenue loss because the size of the tax reduction depends entirely on the profitability of the enterprises benefiting from the incentive.

Profit-based incentives disproportionately favour enterprises that generate tax-free returns with minimal real activity in Lao PDR. Enterprises making large long-term investments in tangible assets, which may initially yield lower returns, benefit comparatively less from such incentives. Expenditure-based incentives avoid this imbalance by providing tax relief as a function of actual investment in Lao PDR’s economy.

Expenditure-based incentives provide a continuous incentive for already existing enterprises to invest further, unlike the current system where investment incentives disappear for these enterprises once the tax exemption period ends. This property of profit-based incentives can also prompt enterprises to create new entities or threaten to move to another SEZ at the end of the exemption period in order to continue profiting from the tax exemption. Expenditure-based incentives do not tie tax benefits strictly to the number of years a business has existed.

Profit-based incentives can induce businesses with activity both within and outside the SEZ to artificially shift profits into the SEZ subsidiary, where profits are untaxed and reporting requirements are more limited (OECD, 2015[39]).

Profit-based incentives reduce the effective tax rate of businesses, which may trigger a “top-up tax” levied in another jurisdiction under the Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) rules (OECD, 2021[40]). If the effective tax rate of a multinational business within the scope of the GloBE rules is below 15%, a foreign jurisdiction may decide to collect a top-up tax in order to bring the business’s effective tax rate to 15%. In such a scenario, Lao PDR forgoes tax revenue, and the profit-based tax incentive is less effective because the tax-exempt business pays tax elsewhere. Certain types of expenditure-based incentives, including immediate expensing or accelerated depreciation, do not affect the effective tax rate calculated under the GloBE rules, so these incentives avoid the risk of a top-up tax being levied in other jurisdictions (OECD, 2022[41]).

There exists a strong rationale for Lao PDR to levy a top-up tax on certain businesses in SEZs, bringing their effective tax rate up to the new global minimum tax rate of 15%. Large multinational enterprises (MNEs) with revenue exceeding EUR 750 million and with a subsidiary in a Lao PDR SEZ could soon face tax obligations in their headquarter country or other countries in which they conduct business if their effective tax rate in Lao PDR is below 15%. This is a result of the GloBE rules agreed by a large number of countries in 2021.16 It is important for Lao PDR to assess how many and what type of MNEs with revenues exceeding the threshold operate in the country’s SEZs. This would help in formulating a strategy to reform Lao PDR’s SEZs, as well as its wider tax incentive regime in the context of the newly established global minimum tax rate. The implications of the GloBE rules should also be taken into account when Lao PDR considers extending the tax exemption status of some SEZs. If the officially recorded payroll and tangible assets of these businesses are significantl, there could be a potential to maintain an effective tax rate below 15%, according to substance-based carve-outs provided for in the GloBE rules.

In the future, tax benefits granted within SEZs could be even more contingent on the employment or training of local workers. This would strengthen the positive spillovers between SEZs and the domestic economy. Currently, foreign workers make up over 50% of the employees in SEZs (IOM, 2019[42]). About 50% of the workforce in SEZs are foreign workers, most of whom work in the construction sector. Laotian workers predominantly work in the manufacturing and services sectors within the SEZs. If a significant portion of activity within SEZs involves foreign enterprises that utilise foreign workers and foreign equipment for export production, all while being tax-exempt and benefiting from subsidised electricity, this arrangement might not be the most advantageous for Laotian taxpayers. The strategic placement of many SEZs right on the border with neighbouring countries suggests that a large share of input materials into SEZs might be imported. If this scenario holds true, it highlights the need to target the tax benefits more effectively in order to ensure that the domestic (and local) economy profits sufficiently from SEZ activities. Lao PDR has introduced rules that mandate investors to staff at least 30% of their workforce with Laotian workers, but it remains unclear whether these rules are enforced (OECD, 2017[43]). More targeted tax benefits could also ensure that enterprises do not use SEZs as a strategy to undermine the tax base in the broader Southeast Asian region. This risk emerges if enterprises are able to relocate their domestic production and workforce just a few kilometres away into a SEZ right across the border in a neighbouring country and thereby avoid paying any significant amount of tax for multiple years.

The tax revenue loss from SEZs can multiply if countries do not properly design and monitor rules on how SEZ businesses interact with the national economy. Trade between SEZs and the national economy appears limited in Lao PDR right now, but additional challenges could emerge if Lao PDR becomes successful in attracting businesses that operate from within SEZs in order to service the domestic market. For example, until recently, the supply of goods from a SEZ-located enterprise to the national economy was not subject to VAT in Lao PDR, which could prompt businesses to route goods through SEZs before making them available to domestic consumers (as businesses can issue a 0% VAT invoice and recover input VAT when they sell goods and services to SEZ businesses). While this particular loophole has been addressed, Lao PDR needs to properly monitor the flow of goods in order to ensure that VAT is levied on these goods in practice. In 2022, the Lao PDR government decided to introduce check-points in order to supervise the entry and exit of goods between SEZs and the rest of the country (JETRO, 2023[44]).

One potential strategy to reduce abuse if SEZ businesses start servicing the domestic economy could be to reconsider the VAT rate of 0% applied to sales to SEZs and to imports into the SEZs, because some of the goods purchased by SEZ businesses may find their way back into the domestic economy. In theory, there is no need to zero-rate products sold to SEZs because the input VAT could have been recovered by SEZ businesses in any case when these businesses export (or resell) the final good. One reason why the 0% VAT rate may be in place is in order to reduce the administrative burden for businesses in SEZs. When considering a reform, it would therefore be crucial to ensure that SEZ businesses are refunded the input VAT quickly upon presentation of the export or sales certificate. If leakages from the suspension of import tariffs are believed to be large (imports could be purchased by a SEZ business but then brought to the domestic market), the exemption from tariffs could be replaced by a drawback mechanism under which SEZ businesses can claim a refund for import tariffs only when they present an export certificate (Zee, Stotsky and Ley, 2002[45]).

In order to avoid additional and ineffective tax revenue loss, future investment incentives in SEZs should only be granted according to predetermined, uniform and clearly declared criteria. The authority to grant tax benefits should lie exclusively within the MOF. The benefits should be codified in the standard income tax law rather than in separate investment promotion laws. As suggested in the latest OECD Investment Policy Review of Lao PDR, negotiations on a case-by-case basis involving multiple government bodies can increase the bargaining power of investors and lead to rent-seeking behaviour (OECD, 2017[43]). The enforcement of existing rules and regulations within SEZs needs to be strengthened as well, and the government has recently announced steps to do so (JETRO, 2023[44]). As enterprises in SEZs are highly observable, it is unclear why a large share of workers in some SEZs are not registered with the social security administration (Gerin, 2022[46]). Tax benefits should be contingent on compliance with other legal obligations, and it needs to be made clear to potential investors that these obligations are enforced.

A thorough cost-benefit evaluation of the SEZ regime’s impact on investment since its introduction in 2003 is required as well. This investigation should centre around determining whether the tax incentives achieved “additionality”, i.e. whether they led to investments that would not have occurred without the incentives. The expiration of the CIT exemption for the first round of investment projects made in SEZs in 2003 (in case these exemptions are not extended) could provide a useful case study to examine how investors behave once the tax benefits fade out and whether the incentive has attracted long-term investment. It could also be a good time to assess the profitability that enterprises in SEZs have reached multiple years after their initial investment. Finally, the assessment should establish whether SEZs have contributed to the artificial growth of certain sectors that are not conducive to the long-term development of Lao PDR but have grown merely as a result of large tax incentives and speculative investor behaviour (such as, potentially, certain projects in the real estate sector). In addition to monitoring the profits that SEZ businesses earn and the taxes they pay, attention should also be given to the profits earned and taxes paid by the SEZ developers (i.e. the businesses that oversee the operations within the SEZs). Even if enterprises are not liable for CIT in SEZs, it is good practice for the tax administration to monitor the economic activity of those businesses.

It is worth mentioning that enterprises in neighbouring countries also enjoy generous profit-based tax incentives from SEZs. A study published in 2015 estimated that there were more than 1 000 SEZs in ASEAN Member States in 2015, and the number of SEZs has continued to grow since then (UNIDO, 2015[47]). In order to protect tax revenues from being undermined by an overuse of tax incentives, excessive competition and the artificial shifting of profits between each country’s SEZs, further regional collaboration on the design of SEZs would be beneficial.

Lao PDR also grants additional investment incentives with slightly different rules for investment projects in less developed areas of the country. For example, businesses that invest in poor remote areas can be eligible for a ten-year exemption from CIT (upon meeting certain other criteria). These incentives generally suffer from the same disadvantages as those available in SEZs. One advantage over SEZs is that the eligibility rules for these incentives are explicitly stated in the 2016 Law on Investment Promotion. They also require a minimum number of Laotian workers to be employed by the investor.

The CIT gap is large

Lao PDR exhibits a large gap between potential and actual CIT revenue, which weakens the link between growth in profits and tax revenue. A recent World Bank estimate puts the CIT gap at nearly 90%, which suggests that Lao PDR loses significant tax revenue from non-compliance and from granting generous tax reductions, such as the exemptions granted for businesses operating in SEZs or reduced rates for specific sectors of the economy (World Bank, 2023[3]). The CIT gap is calculated as the difference between potential and actual CIT revenue. A large CIT gap contributes not only to a low level of tax revenues, but also to low tax buoyancy. If non-compliance is high and if many businesses are exempt from paying CIT (i.e. the CIT gap is large), growing corporate profits do not translate into additional tax revenue for the government. The reverse is true in countries with a smaller CIT gap, where the CIT is often considered the most buoyant tax type because business profits fluctuate strongly over the economic cycle.

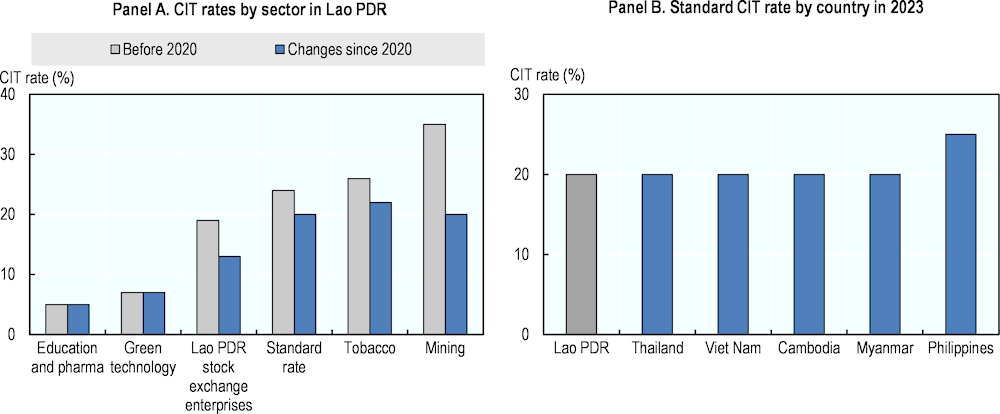

Lao PDR has a CIT system based on differentiated rates by economic sector, which comes with similar disadvantages as the profit-based tax incentives in SEZs. For example, businesses operating in the area of green technologies only pay a CIT rate of 7% instead of the 20% standard rate. Several other sectors also have reduced CIT rates (Figure 4.7), If Lao PDR’s growth strategy aims at growing the economy primarily in the sectors that enjoy reduced CIT rates (e.g. green technologies), and if Lao PDR is successful in implementing this strategy, the country’s CIT revenue will structurally decline in line with economic growth. This is because a larger share of businesses will be taxed under the reduced CIT rate. In addition to the overly generous tax incentives (such as those mentioned in the previous section), the standard CIT system therefore also contributes to the large CIT gap and low tax buoyancy in Lao PDR.

Lao PDR could consider transitioning towards expenditure-based tax incentives and gradually move away from providing reduced CIT rates with little targeting. The tax system should incentivise the transition to new technologies, which could be achieved through more generous tax deduction rules instead of profit-based tax incentives or the use of sector-specific reduced CIT rates. Once businesses in the new technology sector have reached profitability, these profits should be taxed at the standard CIT rate.

Figure 4.7. Tax rates on corporate income by activity in Lao PDR since 2020, and standard CIT rates in peer countries in 2023

Note: The reduced rate for businesses registered on the Lao stock exchange is valid for four years following registration.

Source: Tax rates in Lao PDR by industry from IBFD. Corporate tax rates from (PWC, 2023[48]) and VDB Loi (2023[49]).

Scope exists to increase revenue mobilisation from the mining and hydropower sectors

Opportunities exist to boost revenue generation from the natural resource sector in Lao PDR. Estimates indicate stable non-tax government revenues of approximately 1.2% of GDP from natural resource royalties (75% from mining and 25% from hydropower) and 0.6% of GDP from dividends. However, Lao PDR loses out on tax revenue by repeatedly entering into generous investment agreements with natural resource developers, particularly for major ventures like hydropower projects. These agreements (which are usually undisclosed and negotiated on a case-by-case basis) grant substantial tax reductions, including full CIT exemptions for a specified number of years after the first profitable year. These types of incentives are particularly unsuited for natural resource projects that only run for a limited number of years (like mining projects). In the near term, Lao PDR should (at a minimum) ensure transparency by publicly disclosing the terms granted to investors. Incentives offered by the Ministry of Energy and Mines in the past have also included provisions that exempt the investor from paying a withholding tax on repatriated profits (Netherlands Enterprise Agency, 2017[50]).

The increased CIT for the natural resource sector could be maintained, but it is an ineffective tool for capturing natural resource rents as long as generous tax exemptions continue to be granted on a project-by-project basis. The CIT surcharge can also only be effective if the tax administration is able to monitor how businesses in the natural resource sector declare costs and avoid profits being stripped out of the country. Instead, Lao PDR should prioritise and increase the role of royalties, as they are easier to enforce and collect and are less susceptible to profit manipulation.

The profits of foreign firms are taxed under a deemed profits tax

With the “deemed profits tax”, Lao PDR follows a peculiar approach to taxing the profits of foreign businesses that do not have any registered entities in the country.17 When a Laotian business purchases goods and services from a foreign supplier, the Laotian business needs to withhold a tax on the “deemed profits” of the foreign supplier.18 The tax is calculated by multiplying: (i) the amount of the purchase; (ii) a deemed profit margin specified by the tax administration for each sector; and (iii) the CIT rate. For example, the deemed profit rate in the manufacturing sector is 7%, so any purchase of manufactured goods from foreign suppliers is subject to an additional effective tax rate of 1.4% (7% profit rate × 20% CIT rate).

This deemed profits tax is incompatible with international model tax conventions and would likely have to be reformed were Lao PDR to strive for tax agreements with other countries. In international model tax treaties (such as the UN or OECD model tax conventions), a country’s taxing rights are limited to businesses that have a permanent establishment within the country. That is, only income from businesses that have a permanent establishment in Lao PDR would be taxable in Lao PDR under model tax treaties, and the mere fact of selling goods or services to an enterprise resident in Lao PDR does not trigger a permanent establishment. Other countries may not be willing to sign a tax agreement with Lao PDR as long as the domestic tax system includes a tax that is incompatible with model tax treaty rules.

Lao PDR has already entered into a small number of tax agreements based on model tax treaty templates (with countries such as Singapore and Thailand) despite the treaty rules being incompatible with its deemed profits tax. As per the rules of the tax treaties, suppliers located in either of these two treaty countries should be exempt from the deemed profits tax as long as they do not maintain a permanent establishment in Lao PDR (e.g. in the case of a Thai company selling machinery to a Laotian business).19 If Lao PDR plans to expand its tax treaty network over time, a larger and larger share of foreign suppliers would be exempt from the deemed profits tax, so it would no longer raise meaningful revenue.

The deemed profits tax is also ineffective at taxing the profits of foreign suppliers because, in practice, the deemed profits tax will often simply amount to an additional tax on imports to be paid by Laotian businesses.20 There are many inputs that Laotian businesses can only purchase from foreign suppliers, and purchases from Lao PDR likely constitute only a small fraction of total sales for large multinational businesses. In such a setting, the incidence of the deemed profits tax can be expected to largely fall on the Laotian businesses that purchase goods and services from abroad.

The deemed profits tax complicates the administrative procedures that Laotian businesses have to follow when purchasing inputs from abroad. Aside from the deemed profits tax and the import VAT, businesses often also have to pay an import tariff and an excise tax. Even if the combined tax burden created by these three or four distinct levies is not excessively high, such a system is complex for the government to administer and for the taxpayer to comply with. Businesses also have to consider the different tax implications for each of these taxes: A business can recover the VAT paid on its imports from abroad and it can deduct the excise taxes and import tariffs from its CIT, but the deemed profits tax is not deductible. Lao PDR could consider integrating the deemed profits tax into the VAT or into the import tariff system in order to reduce the number of different taxes importing businesses have to pay.

Without any transfer pricing rules, it is also difficult for the tax administration system to monitor if the prices charged and reported for the purposes of the deemed profits tax rate are correct. Taxing transactions with foreign enterprises based on a deemed profits tax that applies to the foreign enterprise’s domestic turnover creates incentives to manipulate the amount of economic activity and turnover reported in Lao PDR. Businesses could have an incentive to under-report the value of purchases made from foreign suppliers. If a multinational business regularly records transactions with its own subsidiaries outside Lao PDR, the business could have an incentive to reduce the price it charges to itself for the goods and services purchased by its Lao PDR subsidiaries.

The lack of a consistent international taxation framework results in revenue leakages

Lao PDR currently lacks a strong international tax framework, which is necessary in order to limit the taxable economic activity that enterprises and individuals can artificially shift abroad:

Individuals are not taxed on their foreign-sourced capital income because Lao PDR follows a purely territorial principle in its PIT system.

Lao PDR does not participate in international tax information sharing under the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) or Exchange of Information on Request (EOIR) standards. As a result, the country lacks information on the foreign income and assets held by its residents.

There are no codified transfer pricing, controlled foreign company (CFC) or thin capitalisation rules. In addition, the country is not part of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). This, in combination with the low withholding tax rates on payments to non-resident enterprises, can enable businesses to shift taxable profits outside the country.

Lao PDR only has a limited number of tax treaties, and the existing treaties foresee low withholding rates.

Under Lao PDR’s present system, individuals are taxed only on income earned within its borders. For example, capital income earned by residents from assets managed in foreign accounts (like those in countries with low capital income taxes, such as Singapore) remains untaxed in Lao PDR. A territorial approach to personal income taxation can prevent double taxation of foreign-earned income, especially as Lao PDR has few double taxation treaties. However, this is an uncommon approach, and it allows high net wealth individuals to avoid Lao PDR taxes by keeping their savings in low-tax jurisdictions.

Lao PDR could consider transitioning to a worldwide tax regime for personal income in order to tax the foreign-sourced income of individuals who are Lao PDR tax residents. Lao PDR would need to define clear rules that stipulate when an individual is considered a tax resident (for example, if residing in the country for more than 183 days per year) in order to ensure that foreign workers pay tax on their salaries and do not claim tax residency status in neighbouring countries. Currently, Lao PDR employs a worldwide approach for corporate income but a territorial system for personal income. In practice, reversing this system, taxing personal income on a worldwide basis, and partially transitioning to a territorial system for corporate income could better serve Lao PDR.

Participating in the international exchange of taxpayer information, could help Lao PDR raise additional tax revenue. If the country decides to switch to a worldwide tax system for personal income, participating in the information exchange between tax administrations (currently Lao PDR does not participate) could help raise additional tax revenue from undeclared income and assets held abroad by Lao PDR tax residents. Under the EOIR standard, a country’s tax authorities can make specific requests to the tax authorities of other countries for information that will allow them to progress their tax investigations. The AEOI standard organises the automatised annual transmission of detailed information about financial accounts held by non-residents to the resident country. Neighbouring countries such as Viet Nam have started the implementation process, and others (such as China and Thailand) are already sharing taxpayer information. Important regional financial centres, like Hong Kong, China and Singapore, have been sharing information under this mechanism for several years as well.

Through the automatic exchange of information between tax administrations, Lao PDR could gain access to information about financial accounts held by Lao PDR residents in foreign jurisdictions. Collecting tax on these capital income streams would generate additional revenue and strengthen the fairness of the tax system. Among the eight Asian nations that have tracked their increase in tax revenue generated from using the AEOI standard, the average revenue gain since participating in this information sharing was equal to approximately EUR 1.3 billion over the 2020‑22 period (OECD, 2023[51]). These statistics highlight the potential fiscal significance of participating in this information exchange system. While setting up the technical capabilities required in order to participate in the EOIR and AEOI involves upfront investment on the part of the tax administration, technical assistance would be available from international organisations.

Without transfer pricing rules, the tax administration system lacks the tools to verify that goods and services are sold at the correct “arm’s length” price between domestic and foreign enterprises – and taxed correctly under the CIT or deemed profits tax. Businesses may have an incentive to understate the price of intra-group purchases from abroad in order to pay a lower deemed profits tax. However, purchases from SEZ subsidiaries are prone to being overstated in value because these purchases enable businesses to shift more activity into the tax-exempt zone. As a first step, Lao PDR should assess the number of multinational businesses not located in SEZs and the number of Laotian businesses with subsidiaries both within and outside SEZs. These would be the two types of businesses for which the tax revenue loss from transfer mispricing could be the largest.

Despite capacity constraints, the tax administration should develop a set of transfer pricing guidelines for businesses to follow. The tax administration has stated that it does not have the capacity at this point to introduce and enforce full-scale transfer pricing rules (JETRO, 2022[52]). Nevertheless, it should develop guidelines to overcome current shortcomings. Lao PDR does provide some guidance stating that transactions should be recorded at “market value” or “fair value”, but how this price should be determined in the absence of a market transaction (i.e. if the transaction takes place within a group) is unclear. This creates uncertainty for businesses because, at the same time, tax inspectors have the discretion to determine whether or not a particular transaction was recorded at the appropriate price and retroactively adjust its value. As a result, some international businesses prepare transfer pricing compliant documentation even though it is not required. At the same time, the tax administration encounters difficulties in determining the taxable profits of subsidiaries of foreign MNEs that operate in SEZs.

Gaining access to country-by-country (CbC) reports could help Lao PDR carry out transfer pricing assessments on transactions between linked enterprises, and also analyse the tax revenue risk from other tax planning strategies potentially employed by MNEs. Today, as a non-member of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, Lao PDR does not have access to CbC reports prepared under the BEPS Action 13 standard. CbC reports include aggregate data on the global allocation of income, profit, taxes paid and economic activity among tax jurisdictions in which an MNE operates. More than 100 jurisdictions have laws in place introducing a CbC reporting obligation for MNEs. In addition, more than 3 000 relationships were in place for the exchange of CbC reports between jurisdictions in 2022 (OECD, 2022[53]). This means that every MNE with consolidated group revenue of at least MULTINATIONEUR 750 million is already required to file a CbC report – very likely including most MNEs that are active in Lao PDR. For example, China and Thailand (the headquarter countries of several major investors in Lao PDR) require MNEs to compile a CbC report.

The revenue loss from undeclared imports into Lao PDR is substantial

There is a need to enhance customs procedures and border checks in Lao PDR in order to reduce the high levels of fraudulent behaviour. Evidence suggests that Lao PDR may lose up to 1% of its GDP in revenue from import tariffs, excise taxes and import VAT through undeclared imports flowing into the country without being reported to the customs administration (AMRO, 2022[54]). These estimates have been calculated by comparing the value of exports recorded by Lao PDR’s trading partners with the imports recorded by Lao PDR, and then applying the relevant statutory tariffs, excise taxes and import VAT (Table 4.2).

Table 4.2. Undeclared imports into Lao PDR from major trading partners in 2019

|

Lao PDR trading partner |

Discrepancy between import and export statistics |

Major products |

|---|---|---|

|

China |

15% |

Office/data machines, vehicles, furniture |

|

Thailand |

28% |

Perfumes/cosmetics, miscellaneous food, telecommunications |

|

Viet Nam |

41% |

Petroleum and related products, beverages, miscellaneous food products |

Source: (AMRO, 2022[54]), Annual Consultation Report on Lao PDR, based on WITS.