Alexander Hijzen

Reviving Broadly Shared Productivity Growth in Spain

1. Overview

Abstract

Spain has been confronted with weak wage and productivity growth for several decades. This chapter provides an overview of the role that labour market policies as well as other policies can play in reviving broadly shared productivity growth in Spain. To set the scene, it starts with documenting the decline in broadly shared productivity growth and its underlying mechanisms. It then provides a discussion of how policies can enhance the adaptability of the economy and the labour market to structural change. It concludes with a discussion of the role of selected labour market policies for promoting broadly shared productivity gains. The emphasis is on wage‑setting institutions, employment protection and job retention support, consistent with the focus of recent reforms.

1.1. Introduction

A well‑functioning labour market is crucial for sustaining gains in productivity which underpin high and inclusive growth and rising levels of well-being. Yet, productivity growth has tended to slow in Spain since the mid‑1990s. While many other OECD countries also experienced a slowdown in productivity growth, in Spain this started earlier and has been more pronounced. At the same time, average real wages have failed to keep up with even diminished productivity growth, making growth less inclusive. Thus, not only have productivity gains become smaller, but the share transmitted to workers has also declined, resulting in stagnating real wages.

This decline in broadly shared productivity growth reflects to an important extent the difficulty of workers, firms and the labour market more generally to adapt to structural change (adaptability), and more recently, also the long shadow cast by the global financial crisis (resilience). While the experience during the COVID‑19 crisis suggests that labour market resilience has improved, considerable uncertainty remains about the ability of the labour market to adapt to rapid structural changes (e.g. artificial intelligence, green transition). Indeed, seizing upon new opportunities may be a challenge unless the causes of weak productivity growth are effectively addressed.

The objective of this chapter is to provide an overview of the main messages of the report with respect to the role that labour market and non-labour market policies can play in reviving broadly shared productivity growth in Spain. To set the scene, it starts with documenting the decline in productivity growth and its underlying mechanisms. It then provides a brief discussion of how policies can enhance the adaptability of the economy and the labour market to structural change. It then discusses in more depth the role of selected labour market policies in promoting broadly shared productivity gains. The emphasis is on wage‑setting institutions, employment protection and job retention support, consistent with the focus of recent reforms in Spain. The chapter concludes with concrete recommendations to revive broadly shared productivity growth and enhance labour market performance more generally.

1.2. The slowdown in productivity and wage growth in Spain

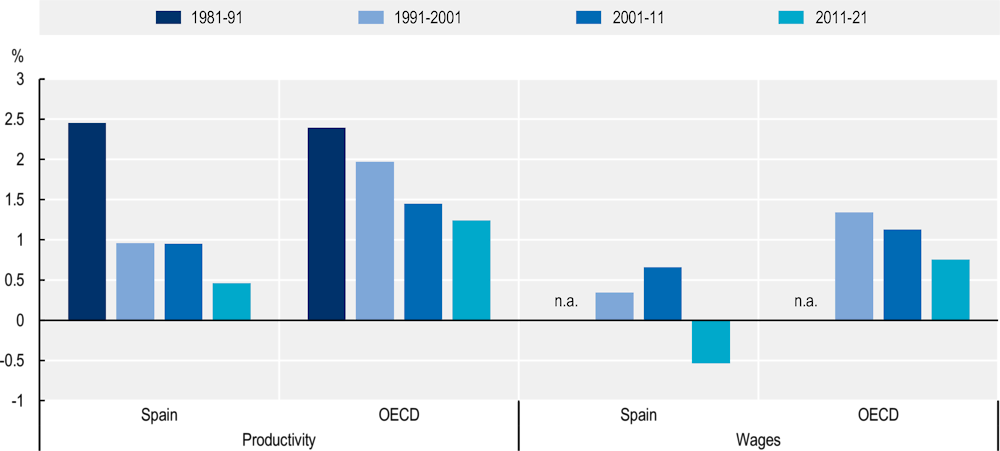

For several decades, Spain has experienced consistently low levels of productivity and wage growth. The decline in productivity growth began in the mid‑1990s, earlier than in many other OECD member countries, and this slowdown has been particularly significant. In recent years, the rate of productivity growth, measured in terms of total output per hour worked, has only averaged 0.5% per year in Spain, whereas the OECD as a whole has seen an average of 1.2% (Figure 1.1). Consequently, Spain’s productivity performance has fallen below the OECD average, with significant implications for the growth of real wages and the overall standard of living. In fact, real wage growth in Spain has remained close to zero since the 1990s, and it even turned slightly negative in the 2010s, failing to keep pace with already weak productivity growth. Weak real wage growth is therefore not just a sign of lagging productivity growth but also reflects additional factors, related to for example changes in wage‑setting due to a decline in the bargaining of power of workers or composition effects due to the growing concentration of productivity gains in capital-intensive firms. This suggests that to restore real wage growth, there is a need not only to revive productivity growth, but potentially also for strengthening wage‑setting institutions.

Figure 1.1. Productivity and wage growth have been particularly weak in Spain

Average annual growth (%)

n.a. Not available.

Note: Productivity is GDP per hour worked. Wages refer to the average across full-time and full-year employees. See Chapter 2 for full details.

Source: OECD Productivity Statistics Database; see Figure 2.1 of this report (Chapter 2) for more details.

The slowdown in labour productivity growth in Spain reflects three fundamental challenges. While many OECD countries have been confronted with similar challenges, they have tended to be more pronounced in Spain.

1.2.1. Slower labour productivity growth mainly reflects a slowdown in making efficiency gains

The bulk of the decline in productivity growth reflects a slowdown in multifactor productivity (MFP) growth, i.e. the slower pace of advancements in the efficiency with which labour and capital are used in the production process thanks to, for example, the adoption of more advanced production technologies and management practices in firms, and the reallocation of capital and labour from less to more efficient firms. MFP growth fell from about 1% in the late 1980s to about 0.25% in the 1990s and even turned slightly negative in the 2000s. Low MFP growth in Spain reflects in part the difficulties of firms and workers to adapt to rapid structural change driven by technological developments and globalisation.

1.2.2. But lower labour productivity growth also reflects a persistent decline in investment

Slow growth in labour productivity also reflects a decline in the pace of capital deepening due to persistently weak investment in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The decline in investment was particularly sharp in Spain due to the collapse of a housing and real estate bubble as well as the banking sector’s exposure to the housing sector. While investment in Spain held up well during the COVID‑19 crisis and its aftermath until 2022, thanks in part to the role of crisis-support and recovery packages put in place by the government, it remains well below its historical average, its level in the OECD on average or nearby countries such as France and Italy. Factors that continue to weigh on investment include weak MFP growth, high economic uncertainty, and enduring financial weaknesses.

1.2.3. Weak labour productivity growth is concentrated in lagging firms and regions

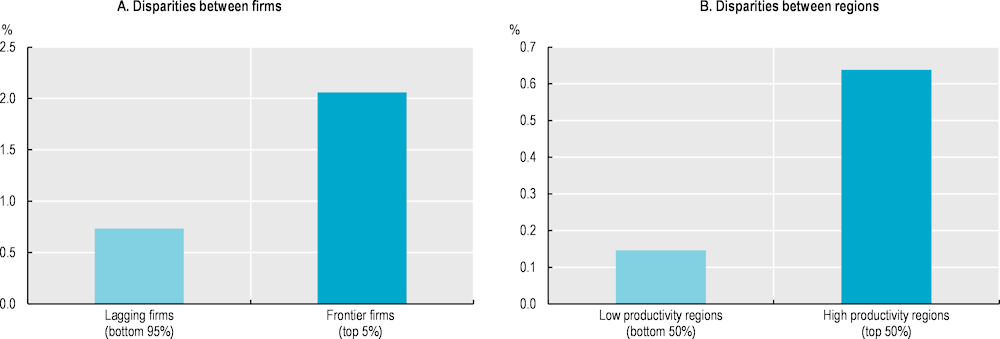

Slow growth in labour productivity is concentrated in lagging firms and regions and hence coincides with deepening economic inequalities (Figure 1.2). While the top 5% of most productive firms in Spain, so-called frontier firms, exhibit healthy labour productivity growth (about 2% per year on average), comparable to that of their counterparts in other OECD countries, labour productivity growth among other firms, so-called lagging firms, has fallen behind considerably (Panel A). A similar pattern is observed across regions, with productivity growth in lagging regions falling behind that of more advanced regions (Panel B). Weak productivity growth in lagging firms and regions is likely to reflect various factors: difficulties in adopting increasingly complex technologies that require high levels of human and organisational capital; weak incentives for firms with structural difficulties to downsize; and barriers to the mobility of workers from lagging to more advanced firms and regions.

Figure 1.2. Slow labour productivity growth is concentrated in low productivity firms and regions

Labour productivity average growth rate

Note: Panel A. Average growth in value‑added per worker across firms (2010‑18). Panel B. Average GDP growth per worker (2011‑19). Firms and regions are classified into lagging and leading categories based on the initial productivity level at the start of the period.

Source: Preliminary calculations following the methodology in Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal (2016[1]) using the 2021 vintage of the Orbis firm-level financial accounts database by Moody’s/BvD, with acknowledgments to Natia Mosiashvili for carrying out the calculations. OECD Regional Statistics Database. See Figure 2.3, Panel A and Figure 2.4, Panel B of this report (Chapter 2) for more details.

1.3. Policies to enhance labour market adaptability

To revive labour productivity growth, a key challenge is to enable firms and workers to increase their efficiency by allowing them to seize upon the opportunities provided by technological change and globalisation. This requires amongst others addressing persistent skill imbalances that limit the adoption of new technologies, promoting the adoption of more advanced technologies while supporting the allocation of resources from less to more productive firms, and tackling regional disparities in productivity.

1.3.1. Significant skill imbalances prevent the full use of new technologies

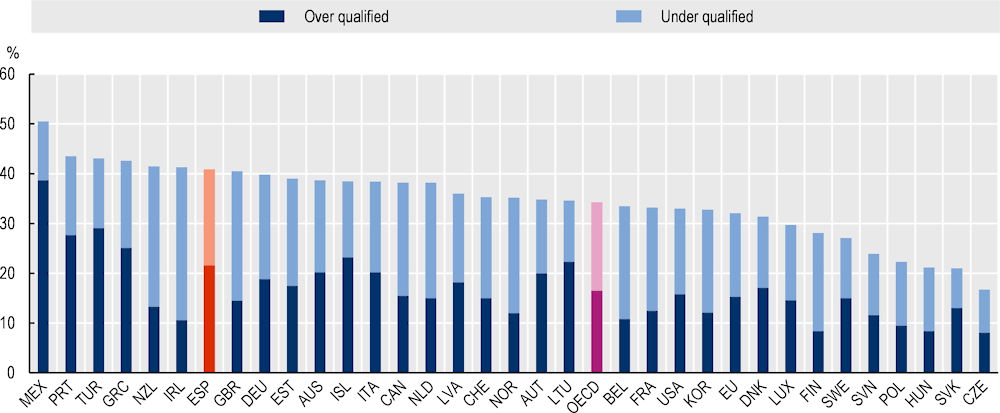

In Spain, a mismatch between the skills provided by workers and those required by firms hamper productivity growth. Compared to other OECD countries, a sizeable share of workers report having higher qualifications than required for their job (22% compared with 17% for the OECD), and to a lesser extent, that they lack the qualifications that are needed (19% compared with 18% for the OECD) (Figure 1.3). While some mismatch is inevitable in a rapidly changing economy, its relative importance in Spain is likely to hold back productivity growth and contribute to persistently high levels of unemployment.

Figure 1.3. Qualification mismatch is common in Spain

Percentage of mismatched workers, 2019

Note: Data refer to 2019, with the following exceptions: they refer to 2017 for Korea; to 2016 for Australia; to 2015 for Türkiye.

Source: OECD Skills for Jobs database (2022), https://www.oecdskillsforjobsdatabase.org/.

To improve the relevance of skills for labour market needs, Spain needs to confront a number of challenges. First, it needs to tackle early school leaving, which remains more common than in most other countries despite progress in recent years: in 2021, 13% of the 18‑24 year‑olds leave school without having gone beyond lower secondary education, compared to an OECD average of 9%. Prevention can work through measures that enhance attitudes to learning such as investments in early education and care and targeting educational resources at disadvantaged students. Second, there is a continued need for building stronger links between the world of education and the world of work. Expanding student enrolment in vocational education and training (VET) in particular should be a priority. The new Organic Law on Vocational Education (March 2022) may help, but its success crucially hinges on its implementation. Involving businesses more closely in the design of degrees and curricula can further help to improve the match between the skills acquired in education and labour market needs. Third, as in most other OECD countries, continued efforts are needed to promote a culture of adult learning and training to ensure that worker skills evolve in line with changing labour market needs. This requires investing more in adult learning to ensure that adults, particularly those with low skills, can upgrade their skills, and in doing so, remain employable and contribute to productivity growth.

1.3.2. Supporting productivity growth in firms

Low productivity growth in Spain mainly reflects low growth among low-productivity firms whereas growth among frontier firms has remained robust. A first priority therefore is to support productivity growth in lagging firms by promoting the diffusion of new technologies. Tackling skills imbalances will facilitate the adoption of advanced technologies in lagging firms, but specific measures that focus directly on lagging firms are also needed. This includes measures that promote investment in intangible assets (e.g. managerial talent, software and R&D) by easing financial frictions and scaling up support for R&D. It also involves initiatives that enhance access to digital communications networks in underserved areas through a combination of private and public investment. Providing a sound regulatory framework that supports the reallocation from less to more productive firms by removing barriers to entry and exit is also important and can help to alleviate skill mismatches between firms and workers (e.g. insolvency procedures, product market regulations, employment protection).

1.3.3. Tackling regional disparities in productivity

Tackling disparities in productivity across regions requires a combination of place‑based policies to support disadvantaged regions (e.g. education, training, activation) and policies that can promote geographical mobility from disadvantaged regions to high-performing ones. Since the implementation of active labour market policies (ALMPs) is the responsibility of regions, more attention could be devoted to assessing the effectiveness of regional skills and training policies, identifying best practices, providing policy guidance and promoting the adoption of more effective policies in lagging regions, in line with the recent Programa de Aprendizaje Mutuo. Geographical mobility can also help reducing regional disparities but tends to be low in Spain. It can be promoted by making location-based welfare entitlements portable, as was done through the introduction of the “social card” and ensuring that affordable housing is available for workers from lagging regions through the use of housing allowances, rent ceilings or social housing targeted to low-income households.

1.4. Policies to enhance the functioning of the labour market

Labour market policies also have an important role to play in reviving broadly shared productivity growth. The discussion below mainly focuses on wage‑setting institutions, employment protection and job retention support, consistent with the focus of recent labour market reforms.

1.4.1. Wage‑setting institutions have been strengthened

Wage‑setting institutions in the form of minimum wages and collective bargaining have significantly been strengthened to promote a broader sharing of productivity gains with workers, particularly those with low wages.

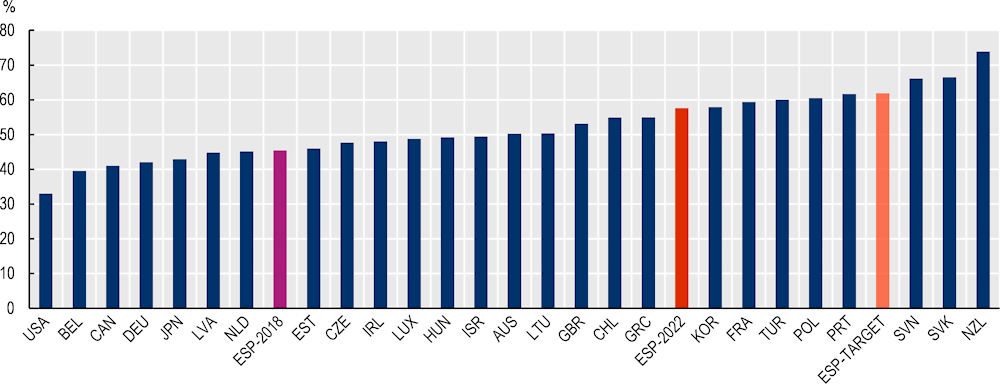

The renewed importance of the minimum wage as a policy tool should not just reflect its level but also its design

The minimum wage has gained significant importance as a policy tool in recent years (Figure 1.4). Until 2018, it only played a modest role as it was set at a relatively low level by OECD standards, around 45% of the median wage in the private sector. However, since then it has rapidly increased. It reached 58% of the median wage in 2022, with most of the increase taking place in 2019, and is set to increase further to 60% of the average net wage, which corresponds to about 62% of the gross median wage, the fourth highest in the OECD. Evidence on the effects of the minimum wage reform of 2019 tend to suggest that this significantly increased the wages of low-wage workers without significantly undermining their employment opportunities (see Box 1.1). These findings are broadly in line with similar studies for other countries.

To ensure that the minimum wage continues to support a broad sharing of productivity gains without undermining employment, a number of actions could be considered. First, continue supporting the work of the minimum wage commission by strengthening its resources to monitor and evaluate the effects of the minimum wage on the labour market, while ensuring that both trade unions and employers take part. This also requires investing in data that allow tracking the wages of individual workers in a timely manner. Second, explore ways to enhance the effectiveness of the minimum wage in supporting the incomes of low-wage workers. For example, an in-work benefit could be introduced to further reduce in-work poverty. More generally, it will be important to ensure that the increased relevance of the minimum wage as a policy tool is reflected in its institutional set-up and design.

Figure 1.4. The minimum wage in Spain is being revalued

Minimum wage as a share of median wage, 2022 unless indicated otherwise

Notes: The figure represents the minimum gross wage in 1 January 2022 as a share of the 2022 gross median wage in the private sector (unless stated otherwise). ESP‑2018 refers to the 2018 minimum gross wage as a share of the gross median wage for 2018. ESP‑target refers to the target minimum gross wage equivalent to 60% of the average net wage as a share of the median gross wage in 2022.

Source: OECD Tax-Benefit model, see Figure 3.1 (Chapter 3) of this report for more details.

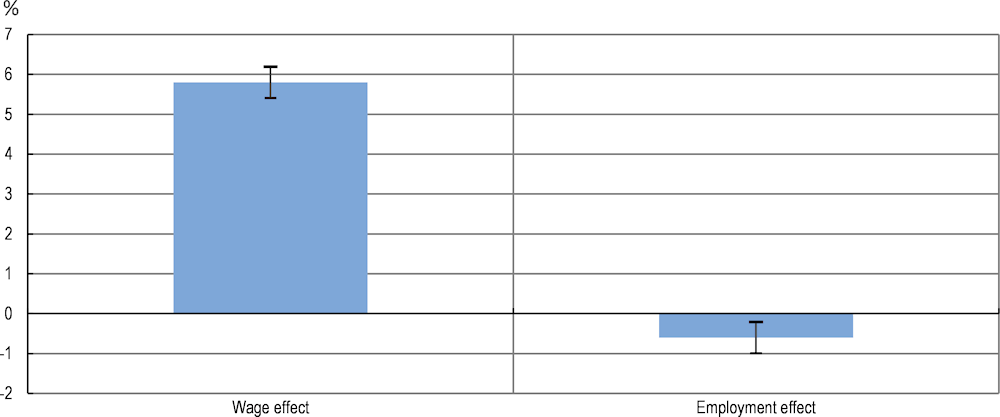

Box 1.1. An assessment of the 2019 minimum wage hike in Spain

In the context of this review, the OECD conducted an evaluation of the impact of the minimum-wage reform that took place in Spain in 2019 (Hijzen, Pessoa and Montenegro, 2023[2]). The reform increased the minimum wage by a 22% in a single step, affecting approximately 7‑8% of employed individuals. The evaluation relied on an in-depth analysis of individual-level data in which the outcomes of workers employed in the year prior to the reform are tracked over time.

The results of the evaluation indicate that, among the workers directly affected by the minimum wage increase, the reform increased monthly earnings by on average 5.8% and reduced employment by 0.6% or about 7 000 jobs (Figure 1.5). Further analysis indicates that job losses were more pronounced among workers holding fixed-term contracts. In summary, the 2019 minimum-wage hike had a significant positive effect on the wages of low-wage workers, without causing substantial job losses.

Figure 1.5. The wage and employment effects of the 2019 minimum wage hike in Spain

Change in outcome between 2018 and 2019 relative to that between 2017 and 2018

Note: Estimated coefficients plus 95% confidence intervals based on clustered standard errors by province, industry and wage bin.

Source: Hijzen, Pessoa and Montenegro (2023[2]), “Minimum wages in a dual labour market: Evidence from the 2019 minimum-wage hike in Spain”, https://doi.org/10.1787/7ff44848-en.

Continue efforts to promote social dialogue in the workplace and at national level

To further promote a broad sharing of productivity gains, the labour market reform of 2021 has considerably strengthened sectoral collective bargaining and the position of sectoral trade unions. To some extent, this reverses the 2012 labour market reform that sought to decentralise the system by providing more scope for negotiation at the firm level. The initial hope was that this would contribute to more flexibility at the firm level and support employment and productivity growth. It is not clear however whether the 2012 reform has indeed led to more negotiation at the firm-level, possibly due to the lack of worker representation in smaller firms. However, there are concerns that it has undermined the bargaining position of trade unions at the sectoral level and that this has contributed to the decoupling of wage growth from productivity growth. To allow making use of the remaining scope for negotiation at the firm-level and support the quality of labour relations more generally, further efforts could be made to promote the representation of workers in the workplace, especially in smaller firms, as has been done for example in Italy (see Chapter 3 for details). At the same time, there is a continued need to involve the social partners at the national level in the co‑ordination of wage agreements across sectors, including to ensure that the costs of increased energy prices are fairly shared between firms and workers, and the development of broad-based forward-looking reforms that can help to make the labour market more adaptable to future challenges.

1.4.2. The use of temporary contracts has been curtailed

Employment protection can contribute to stronger productivity growth by strengthening incentives for the accumulation and preservation of firm-specific human capital in the workplace based on stable employer-employee relationships and the use of high-performance work and management practices. However, evidence for OECD countries suggests that it can also undermine productivity growth by reducing the tendency of firms to adjust employment in line with changing business conditions and strengthening incentives for the use of flexible work arrangements, resulting in labour market duality. From a productivity perspective, it is therefore crucial that employment protection strikes the right balance between supporting job reallocation and providing incentives for learning and innovation.

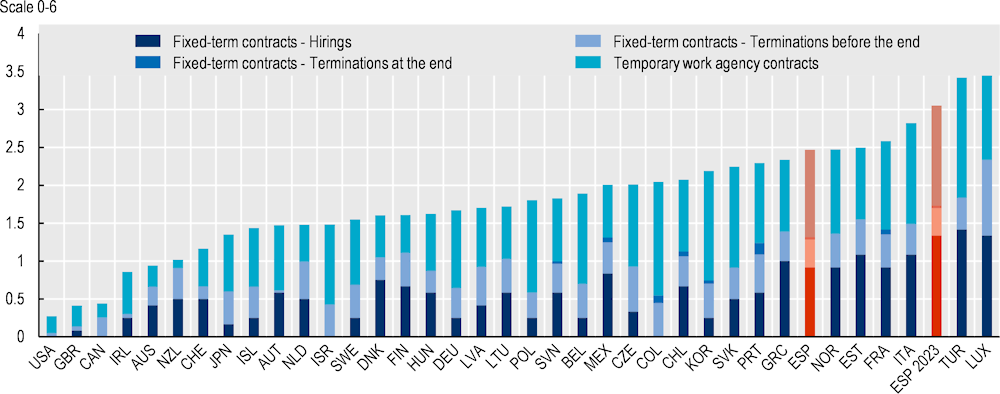

The excessive reliance on fixed-term contracts presented a major challenge for Spain. To tackle labour market duality, the use of fixed-term contracts has been significantly restricted. Since the entry into force of the 2021 labour market reform, open-ended contracts became the default contract, while the use of fixed-term contracts has been strictly limited to temporary staff needs. More specifically, i) the very flexible and widely used contract for work and service (contrato por obra o servicio) has been abolished, ii) the existing training contracts (contrato de trabajo en prácticas and contrato para la formación y el aprendizaje) have been replaced with two shorter training contracts (contrato para la obtención de la práctica profesional and contrato de formación en alternancia); and iii) the requirements to justify the temporary nature of needs have been strengthened. As a result, Spain has become the country with the third strictest rules for the use of fixed-term contracts in the OECD (Figure 1.6). Another important part of the reform, but one that is not reflected in the OECD Employment Protection indicators, is the increased scope for the use of open-ended intermittent contracts (contrato fijo-discontinuo) to all intermittent activities, temporary agency work, and contract work. Consequently, open-ended intermittent contracts can be used for many of the activities that were previously conducted with temporary contracts.

The reform has resulted in a sharp reduction in the incidence of fixed-term contracts during the first year following its implementation. The incidence of fixed-term contracts declined by about a quarter from more than 20% in 2021, the second highest in the OECD, to less than 15% in the first quarter of 2023. Moreover, the decline in the number of fixed-term contracts is offset by a similarly sized increase in the number of open-ended contracts, suggesting that for now the reform did not have major effects on overall employment. A significant fraction of the increase in permanent employment, about 20%, reflects the increased use of open-ended intermittent contracts. Its incidence in employment doubled from 2.7% in 2021Q1 to 5.3% in 2022Q4. Such contracts offer more employment stability than temporary contracts but not necessarily more income security for workers. Although working hours are known in advance, they may vary over time depending on the length of the period of activity and the season, within the limits of the applicable sectoral collective agreement. The medium-term implications of the reform need to be closely monitored. The government has committed to a full evaluation of the reform by 2025.

Looking ahead, there may be a case for further adjusting the regulation of contracts. First, the appropriate use of all contracts should continue to be closely monitored and transitions from temporary and intermittent contracts to regular open-ended contracts could be promoted further. While efforts are already made to promote such transitions (e.g. systematically informing workers of vacancies for regular open-ended positions in the same firm; promoting training during periods of inactivity) more could be done (e.g. paying more attention to career guidance, developing flexible courses that can be combined with intermittent contracts). Second, workers could be given greater incentives to terminate open-ended contracts by mutual consent under certain circumstances. Unlike in many other OECD countries, workers who end their contract by resignation or mutual consent are not entitled to unemployment benefits and cannot easily access public employment services. This reduces the willingness of workers to terminate contracts voluntarily and increases the cost of dismissal for firms. Third, the balance between the length of notice period and other aspects of employment protection could be adjusted. Notification periods are currently relatively short, which makes it hard for the public employment services to intervene early before dismissal takes place. To allow intervening earlier and provide more effective support to displaced workers, the notification period could be increased, while other aspects of employment protection could be adjusted to keep the overall stringency of employment protection constant.

Figure 1.6. The regulation of employment contracts is relatively strict in Spain

Regulation of fixed-term and temporary work-agency contracts (0‑6), 2019 and 2022

Source: OECD EPL database, see Figure 3.7 (Chapter 3) of this report for more details.

1.4.3. The scheme of job retention support has become a model for best practice

Job retention schemes aim to safeguard temporarily vulnerable jobs by enabling companies to adjust their workforce in response to economic downturns while also providing financial support to employees facing suspensions or reduced working hours. From a productivity standpoint, the primary benefit of these schemes lies in the preservation of company-specific skills and expertise in positions that may be temporarily unprofitable but have long-term viability. A potential drawback is that job retention support might be used to sustain jobs in businesses experiencing structural challenges, potentially impeding the efficiency-enhancing reallocation of jobs among different companies that differ in their productivity.

While the use of job retention support was negligible during the global financial crisis, it played a major role in preventing job losses during the COVID‑19 crisis in Spain. In April 2020, just one month after the outbreak of the pandemic, almost one in four workers were covered by Expedientes de Regulación Temporal de Empleo (ERTE). Thanks to the widespread use of job retention support, the increase in unemployment in response to the decline in economic activity was several times smaller during the COVID‑19 crisis than during the global financial crisis when unemployment surged. The positive impact of job retention support on employment is also confirmed in an ongoing evaluation by the OECD (2024, forthcoming[3]). Moreover, the use of job retention support declined quickly as economic restrictions were withdrawn and the generosity of support scaled back. The fact that take‑up did not persist long into the recovery is reassuring and suggests that ERTE is unlikely to have had a major impact on slowing job reallocation from low-productivity firms with structural difficulties to high-productivity ones with healthy growth prospects.

The labour market reform of 2021 also affected the regulation of ERTE. It established the parameters for the permanent scheme and introduced an explicit framework for scaling up support in times of exceptional need (the “RED mechanism”) (OECD, 2024, forthcoming[3]). More specifically, the reform created two new types of ERTEs that can be “activated” in the case of either (i) macroeconomic cyclical downturns, or (ii) sectoral transformations that require substantial labour reallocation. These schemes are activated by the government, in the second case, following the request of a tripartite committee. This possibility is referred to as the “RED Mechanism”. Once this mechanism is activated, firms can apply for the use of ERTE under a special procedure while benefiting from favourable exoneration rates to social security. Spain is now one of the few OECD countries with an explicit framework for scaling up support in times of exceptional need (RED Mechanism). It allows for government discretion over its activation while the parameters of the crisis scheme are defined in advance.

While ERTE already presents a well-designed job retention scheme, it may still be possible to further enhance its effectiveness in the future. For example, the effectiveness of training while on short-time work could be strengthened by requiring work-related training to be provided externally by certified external suppliers and monitoring the effectiveness of training courses through the use of regular evaluations. Moreover, the targeting of support could be enhanced by replacing direct co-financing by firms with experience‑rated employer contributions. This could be part of a broader reform that introduces a bonus-malus system for the financing of unemployment insurance, following the examples of France and the United States. Such a system would provide incentives for employers to internalise the costs of short-time work, intermittent inactivity and layoff decisions for society without affecting the benefits for employees.

1.4.4. There is a growing debate on the potential role of a shorter working week for well-being and productivity

In Spain as well as in several other OECD countries, there is a growing debate on the possible role that working-time reductions can play in promoting well-being and productivity and the possible introduction of a four‑day working week. Indeed, there is clear evidence that very long working hours increase health risks and reduce job satisfaction and hourly labour productivity. There is also some evidence based on working time reforms in different EU countries that reducing the normal working week can raise wages and productivity, with little or no effect on employment. The evidence on reducing the number of weekly working days to four remains patchy and tends to be based on small-scale trials with voluntary participation.

The current regulation of working time in Spain is similar to that in most EU countries. It limits statutory normal working hours, excluding overtime, to 40, while overtime has to remain within the limit of 80 hours per year. These rules comply with the EU Working Time Directive which limits total weekly hours including overtime to 48. However, it also allows for flexibility through the use of collectively agreed derogations in certain sectors and activities. The flexibility in the Spanish system suggests that collective bargaining can play a potentially important role in reducing normal and maximum weekly working in cases where this is likely to increase worker well-being as well as productivity.

The government should build on the strong involvement of the social partners in the regulation of working time to promote policy experimentation and expand the evidence base. This should help to better understand to what extent a shorter working week can generate sufficiently large productivity effects to compensate employers for the increase in hourly labour costs and/or workers for the loss in earnings (depending on the way the shorter working week is implemented), and the extent to which any productivity effects depend on the way the shorter working is organised (more compressed worker schedules over fewer days or fewer hours per day) and the economic activity of the firm.

Box 1.2. Recommendations to revive broadly shared productivity growth in Spain

Framework conditions

Support lagging firms by fostering the adoption of advanced digital technologies and efficient management practices, promoting investment in intangible assets and enhancing access to digital communications networks.

Continue efforts to provide a regulatory framework that supports the reallocation of resources from less to more productive firms (e.g. insolvency regulations, product market regulations, employment protection).

Education and training policies

Increase the inclusiveness of the education and training system by tackling early school leaving and remedying skills gaps through second-chance schools and adult learning programmes.

Enhance the responsiveness of the education and training system to changing labour market needs by promoting a culture of life‑long learning, increasing the number of places in vocational education and training (VET) and involving employers more strongly.

Minimum wages, working time and collective bargaining

Continue supporting the work of the minimum wage commission, by ensuring that both trade unions and employers take part and strengthening its resources to monitor and evaluate the effects of the minimum wage on the labour market.

Explore ways to further enhance the role of the minimum wage by leveraging its co‑ordination with the tax-and-benefits system.

Support social dialogue and organised decentralisation by further promoting the local representation of workers in firms.

Continue supporting the efforts of the social partners to reach broad and forward-looking agreements such as that that led to the 2021 reform or the 2023 social pact on wages.

Build on the strong involvement of the social partners in the area of working time to promote a better understanding of the effects of a shorter working week by facilitating policy experimentation and expanding the evidence base.

Employment protection and job retention support

Continue monitoring the appropriate use of all types of contract and further support transitions to regular open-ended contracts.

Establish procedures to promote termination by mutual consent while maintaining access to unemployment benefits under certain circumstances.

Increase the length of the notification period to allow providing early support to dismissed workers, while adjusting other aspects to keep the overall stringency of employment protection constant.

Promote the effectiveness of training while on short-time work by requiring work-related training to be provided externally by certified suppliers and conduct regular evaluations to assess the effectiveness of training courses.

Unemployment benefits and activation policies

Experience‑rate employer social security contributions for unemployment insurance and short-time work.

Provide employment services to workers who are at risk of job loss by intervening early during the notice period for dismissal or reaching out to workers on short-time work for structural reasons.

Enhance the effectiveness of active labour market policies in lagging regions by identifying best practices and providing technical and financial support to local providers.

References

[1] Andrews, D., C. Criscuolo and P. Gal (2016), “The Best versus the Rest: The Global Productivity Slowdown, Divergence across Firms and the Role of Public Policy”, OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 5, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/63629cc9-en.

[2] Hijzen, A., S. Pessoa and M. Montenegro (2023), “Minimum wages in a dual labour market: Evidence from the 2019 minimum-wage hike in Spain”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 298, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7ff44848-en.

[3] OECD (2024, forthcoming), Preparing ERTE for the future: An evaluation of job retention support during the COVID-19 crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris.