As digital transformation accelerates, policy makers must consider not only which policies are important, but also how those policies are co-ordinated, monitored and implemented. This is because the success of policies to achieve their desired outcomes depends on devising effective governance regimes. This section briefly discusses the Going Digital Integrated Policy Framework (Framework), which is used as a guide to Norway’s digital policy landscape. It then considers recent developments in the Norwegian digital policy ecosystem, including the main entities that design and implement digital policies in Norway. The section then briefly examines Norway’s current national digital strategy (NDS) – the “Digital Agenda for Norway” – as well as the wider digital policy landscape.

Shaping Norway’s Digital Future

Section 2. Mapping norway’s digital policy ecosystem

The Framework as a benchmark for a holistic approach to policy making

Digital transformation affects almost all aspects of the economy and society, and designing effective digital policies requires a whole-of-government effort. The effects of digital technologies and data differ depending on national context and culture. However, the challenge of navigating the digital transition effectively and ensuring that well-being and growth are not just protected, but enhanced, is a global one. For this reason, the Framework (OECD, 2020[1]) aims to help countries build a more inclusive and prosperous digital future with effective, impactful and evidence-based digital policies.

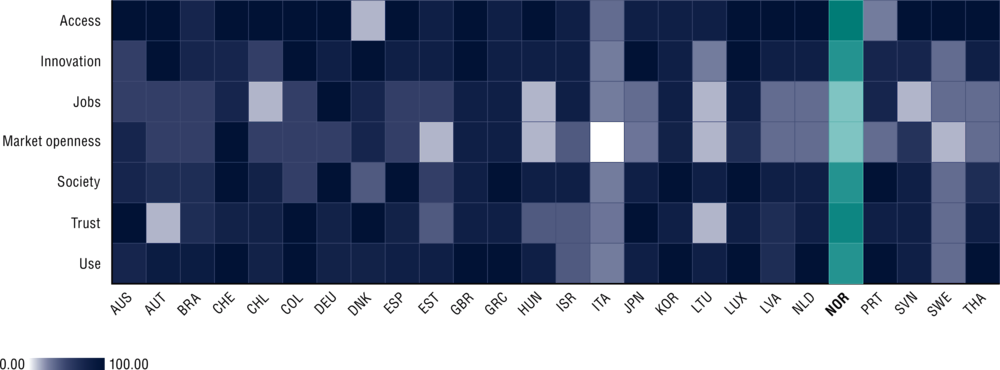

The Framework comprises seven interrelated policy dimensions (Access, Use, Innovation, Jobs, Society, Trust and Market openness), each of which contain several policy domains (Figure 7). Growth and well-being are at its heart, and several transversal domains (investment, digital government, skills, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), tax and benefits, regional development, privacy and security) cut across multiple dimensions. Some domains, such as data and data governance, are relevant for all of the Framework’s dimensions.

Figure 7. The Going Digital Integrated Policy Framework

Source: OECD (2020[1]), “Going Digital integrated policy framework”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 292, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dc930adc-en.

The Framework has been used as a guide to develop national digital strategies in OECD countries and partner economies. It has also been applied as a benchmark to assess the comprehensiveness of national digital strategies (Gierten and Lesher, 2022[20]). Recognising the evolving nature of digital technology, the Framework has remained relatively flexible to accommodate changes in the landscape. It further provides guidance on the governance of digital policies to ensure coherence and co-ordination across all domains and sectors that shape digital transformation. This includes how to involve all relevant stakeholders in the development and implementation of digital policies.

Norway’s governance ecosystem

While governance understandably varies between countries, research has shown certain cross-country trends in the governance of national digital strategies. Most notably, there is a growing move towards the development and co-ordination of national digital strategies being led either at the prime ministerial or chancellery level of government, or by a dedicated digital ministry (Gierten and Lesher, 2022[20]; OECD, forthcoming[21]). This approach helps ensure that digital policies are created and organised by bodies with enough specialist knowledge to design them effectively and with enough clout to guarantee their implementation.

The Norwegian government has created a new ministry to steer the country towards an inclusive digital society. In October 2023, the government announced the creation of the Ministry of Digitalisation and Public Governance. The new ministry, alongside a new ministerial post with the same title, took effect on 1 January 2024 (Office of the Prime Minister, Norway, 2023[22]). The new ministry comprises elements of digital policy previously situated in the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. This announcement reflects the growing importance of digital transformation to the Norwegian government and ensures the forthcoming NDS will have a dedicated home. Central to its success is the ability of the new ministry to collaborate effectively with others, given the cross-cutting nature of digital transformation.

While the new ministry leads on digital policy, it is supported by a range of other actors, including an agency focused on the public sector, as well as departments, regulators, and other agencies and trade organisations. The creation of the new ministry means that one government body will assume primary responsibility for designing, implementing and evaluating digital policy. The ministry will be complemented by the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency (Digdir), an underlying agency that will co-ordinate the digitalisation of the public sector. This will help create a coherent approach and support effective co-ordination across the full range of Norwegian digital policies. Beyond this organisation, however, a number of others are vital to the healthy functioning of Norway’s digital policy governance ecosystem. These are highlighted below.

Government departments

Given that various departments address digitalisation and its impacts within their individual sectors, Norway needs to ensure they work in sync to achieve its digital policy priorities. As every sector of the economy digitalises, specialist and sector-specific knowledge can often improve the design and delivery of policy. In Norway’s case, in addition to the Ministry of Digitalisation and Public Governance, a range of other departments prepare and oversee elements of the digital policy landscape. Each ministry is responsible for digitalisation in its respective sector. For example, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security and the Ministry of Defence are jointly responsible for Norway’s National Cyber Security Strategy. For its part, the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, including the Directorate of Health, manages Norway’s National Strategy for e-health. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education and Research directs skills and education policy from school age into research settings and adult life. Effective co-ordination between and among these agencies and others is essential for Norway to achieve its digital policy priorities.

Regulators

Independent regulators contribute specific expertise and ensure markets function effectively. They are responsible for upholding regulation in a fair and even-handed way and can be crucial partners to small and new firms seeking to enter tightly regulated markets. To that end, they help such firms understand and comply with complex regulations. Increasingly, regulators are also helping stimulate innovation by creating regulatory sandboxes. These ensure that new products and services can be tested and improved without fear of sanction if they do not meet existing regulations.

Norwegian regulators are already part of the digital ecosystem. The Norwegian Communications Authority (Nkom) and the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (Datatilsynet) are both underlying agencies of the Ministry of Digitalisation and Public Governance. They play an important role in digital policy making in Norway, as does the Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway (Finanstilsynet), which operates or oversees digital policies in financial markets. These organisations are key to achieving the priorities of ensuring a high-quality information and communications infrastructure, developing the data economy, and fostering data protection and information security.

Agencies and trade organisations

Alongside government departments and regulators, government-funded agencies and industry-founded trade organisations can also help ensure that digital transformation works for growth and well-being. They tend to be more agile and better able to form close connections with industry participants, while benefiting from a narrower and more focused remit than government departments. In many cases, these organisations can be backed with significant amounts of government capital to deliver large and important programmes with a real impact on individuals and firms.

Innovation Norway and Digital Norway are both helping the government achieve its digital objectives. These organisations work directly with individuals and firms to provide advice and guidance, as well as implement government-funded programmes. Innovation Norway, founded by the Norwegian government, specialises in helping innovative companies to grow and establish themselves overseas. Meanwhile, industry founded Digital Norway to help SMEs digitalise. Both organisations are integral to Norway’s priority to support further digitalisation of SMEs.

The “Digital Agenda for Norway”

At the centre of Norway’s digital policy landscape is its NDS “Digital Agenda for Norway”, which sets out how the country can exploit information and communication technology (ICT) in the best interests of society (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2016[23]). This report to the Storting, published in 2016, has two main objectives: to create a user-centric and efficient public administration and to enhance value creation and inclusion, beneath which sit five key priorities:

a user-centric focus;

ICT as a significant input factor for innovation and productivity;

strengthened digital competence and inclusion;

effective digitisation of the public sector; and

sound data protection and information security.

The Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development (now the Ministry for Digitalisation and Public Governance) is the primary lead for development, co-ordination, monitoring and evaluation of the strategy. However, given the cross-cutting nature of digital transformation, all ministries are expected to contribute to and implement the strategy. Overall, the strategy has been backed with a budget of NOK 1 500 000 000 for digitalisation initiatives, which is decentralised across all of the ministries implementing the objectives in the report.

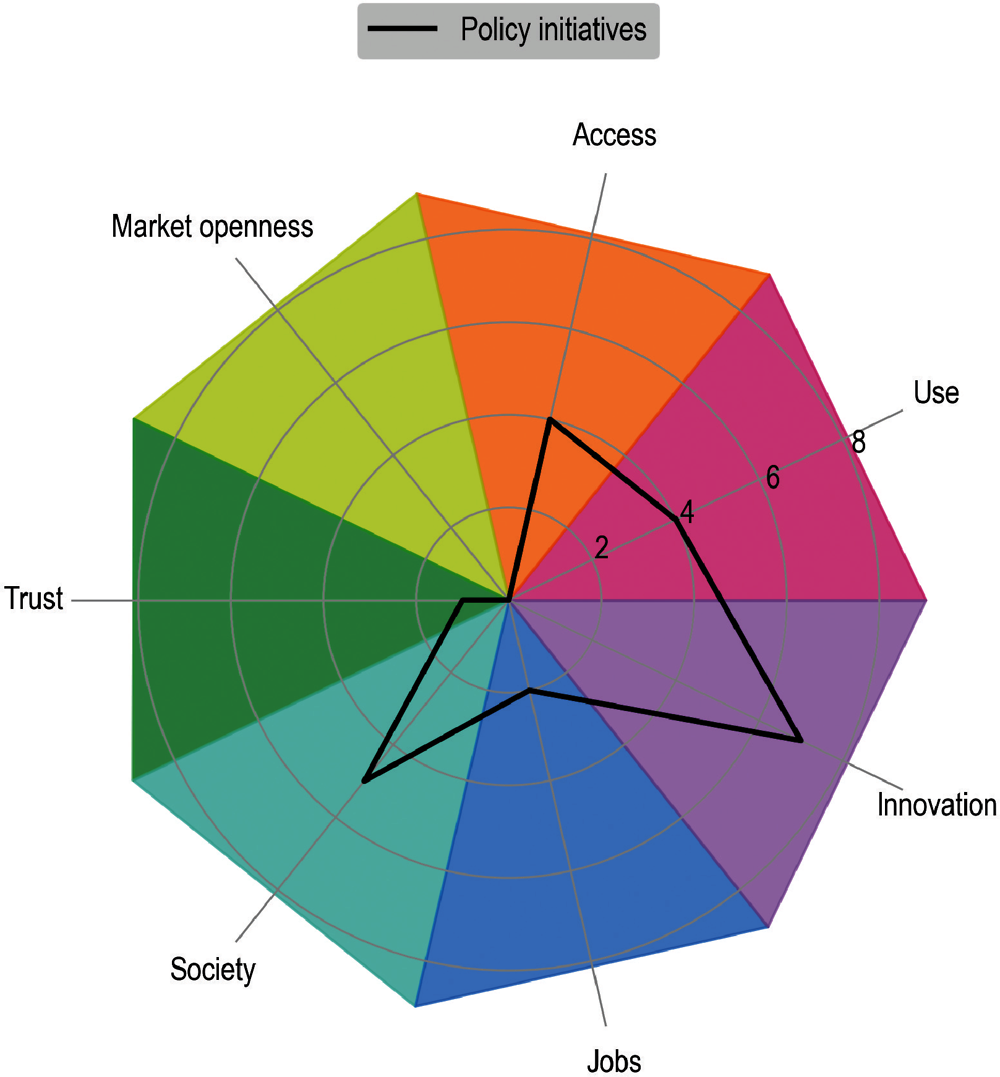

The comprehensiveness of the Digital Agenda for Norway was assessed using the Framework as a benchmark (Gierten and Lesher, 2022[20]). The resulting National Digital Strategy Comprehensiveness indicator (NDSC) measures how comprehensively Norway’s NDS covers the Framework. It also serves as a tool to determine the likely effectiveness of the NDS in promoting a digital transition that boosts growth and well-being (Figure 8). The higher the NDSC score per Framework dimension, the more comprehensively that dimension is covered in the NDS. Each dimension is scored out of a maximum of 100.

Figure 8. National digital strategy comprehensiveness across countries

2021

Notes: Norway’s NDSC score is based on the NDS in force, the “Digital Agenda for Norway” strategy. A darker colour indicates greater comprehensiveness in relation to the Framework.

Source: OECD (2024[96]), OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on the OECD National Digital Strategy Database, https://oe.cd/ndsc.

Based on the NDSC, Norway scores highly for dimensions such as Access and Trust, but it needs to improve coverage in Jobs and Market openness. The NDSC for Norway shows that Access is the most comprehensively covered dimension, and the only area to achieve the maximum score of 100. This is followed by Trust (80), Use (71) and Innovation and Society (67). Jobs and Market openness are the least comprehensively covered dimensions, each with a score of 40. As Norway develops its next NDS, improving its level of comprehensiveness in domains such as Jobs and Market openness will help ensure all areas of the Framework are implemented effectively. This, in turn, will help Norway achieve its digital policy priorities in a holistic manner.

Norway’s digital policy landscape beyond its national digital strategy

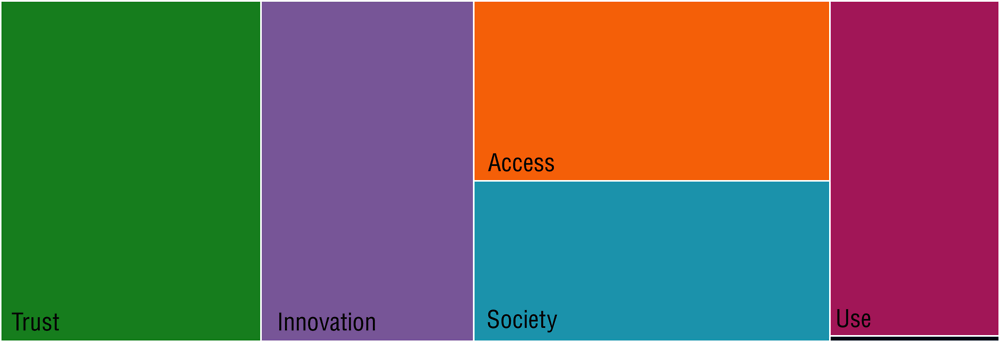

Beyond Norway’s NDS, the wider digital policy landscape clearly plays a definitive role in Norway’s ability to achieve its policy objectives. Figure 91 shows Norway’s major digital policy initiatives mapped according to the Framework’s seven dimensions. At first glance, Innovation is the area with the most policy initiatives, followed by Society, Access and Use. There are two initiatives in the Jobs dimension, only one in Trust, and none in the Market openness dimension. More detail about the policy initiatives can be found below and in Annex A.

Figure 9. Norway’s digital policy landscape

Per dimension of the Framework, 2023

Note: The depth of the colours in each of the Framework’s dimensions do not represent any score or numerical value.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the 2024 OECD Digital Economy Outlook Questionnaire.

Simply counting the number of initiatives is not a robust method of determining the level of policy focus given to each dimension. One well-funded and detailed initiative with clear goals and policy measures, for example, can have much more impact than several more limited and less specific initiatives. Moreover, the relationship between a policy initiative’s success and its level of funding is not always linear. However, exploring the size of budget allocated to a specific intervention can offer clues to its likely effectiveness and its relative importance for a national government. Figure 10 provides a relative assessment of the different levels of funding allocated to each dimension of the Framework within Norway’s digital policy landscape.

Figure 10. Allocated budget for Norway’s digital policy landscape per Framework dimension

NOK, 2024

Notes: The Jobs dimension is displayed under Use in dark blue. No budget is indicated for Market openness. Some policy initiatives are relevant for more than one dimension; therefore, some funding has been counted more than once. The budget allocated to Meld St. 28 in the Access dimension, for example, incorporates the budget for the broadband support scheme, and the security and resilience scheme.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the 2024 OECD Digital Economy Outlook Questionnaire.

The data show a relatively even allocation of funding across most Framework dimensions except for Jobs and Market openness, which received little or no funding. This is particularly surprising for Jobs, given the likely cost of delivering skills and training initiatives. Most funding was allocated to the Trust dimension, which will help Norway achieve its priority to develop the data economy and foster data protection and information security.

The relationship between Norway’s NDS and its other major digital policies

How well the forthcoming NDS can co-ordinate Norway’s wider digital policy landscape is a crucial determinant of its success. The rapid pace of technological change means obsolescence is, to a certain extent, built into the design of digital policies. This means new policies are almost constantly under development. Thus, losing sight of the wider strategic direction is easy without clear and explicit co-ordination between the NDS and its policy environment. To the extent possible, clearly identifying and linking the NDS with future policies also helps ensure it will remain relevant throughout its life cycle.

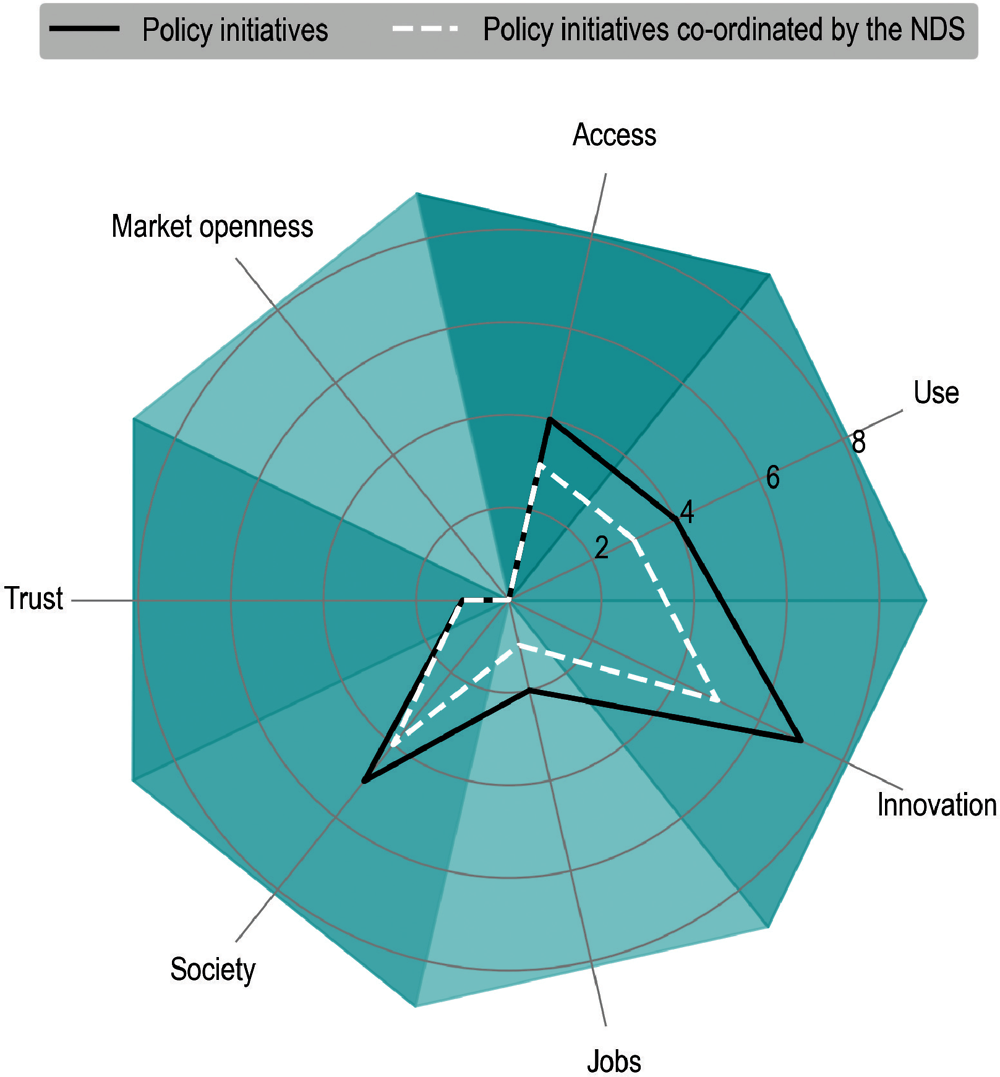

An analysis of how the major digital policies in Norway’s ecosystem interact with its NDS reveals the extent to which the strategy acts as a strong co-ordinating force. Figure 118 combines the NDSC indicator and the assessment of the wider digital policy landscape. It shows that Norway’s NDS co-ordinates most of its digital policy landscape in all dimensions. While the Trust dimension includes a relatively small number of policy initiatives, it is the second most comprehensively covered in Norway’s NDS and the area with the largest budget. This suggests there is strong policy action in this dimension. Norway’s NDS also co-ordinates all major policy initiatives in the Trust dimension.

Figure 11. Disentangling the relationship between Norway’s NDS and its major digital policies

Norway’s NDSC (heatmap) and major digital policies, 2023

Notes: Norway’s current NDS is the “Digital Agenda for Norway” strategy. For the NDSC (heatmap), a darker colour indicates greater comprehensiveness in relation to the Framework.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the 2024 OECD Digital Economy Outlook Questionnaire and the OECD National Digital Strategy Database, https://oe.cd/ndsc.

As Norway develops its next NDS, it needs to ensure a greater balance among the seven dimensions. The Innovation and Society dimensions are equally comprehensive in Norway’s NDS. However, there are more Innovation initiatives in the wider policy landscape and it receives more funding than Society. Norway’s NDS co-ordinates some of the small number of Jobs digital policy initiatives. Jobs and Market openness are the two dimensions least comprehensively covered by the NDS. They have the fewest initiatives and, likewise, the least amount of funding allocated to them. This suggests that Jobs and Market openness dimensions are in the greatest need of enhanced policy focus as Norway develops its next NDS.

Norway can draw on lessons learnt from outside the digital policy landscape to inform its next NDS. Policy initiatives not co-ordinated by Norway’s NDS tend to be either highly technical or implemented primarily by a technical agency, such as the Finanstilsynet’s fintech regulatory sandbox. In addition to co-ordination, adequate monitoring and evaluation helps ensure policies achieve their desired outcomes. It also enables policy makers to learn lessons for use in future policies. The Norwegian government has indicated that it monitors and evaluates all policies within its digital policy landscape and its NDS (Table A.1). Using the outputs of these processes should help develop the forthcoming NDS by enabling integration of good practice from elsewhere into the policy ecosystem.

Note

← 1. The total number of major policy initiatives differs from the numbers indicated by the black line because some policy initiatives are relevant to more than one dimension as they contain specific measures that relate to domains that cut across various framework dimensions. As a result, some policy initiatives are included more than once. A full breakdown of the policy initiatives considered and how they were mapped to the Framework dimensions can be found in Annex C.