This chapter provides an assessment of Colombia. It begins with an overview of Colombia’s context and subsequently analyses Colombia’s progress across eight measurable dimensions. The chapter concludes with targeted policy recommendations.

SME Policy Index: Latin America and the Caribbean 2024

17. Colombia

Abstract

Overview

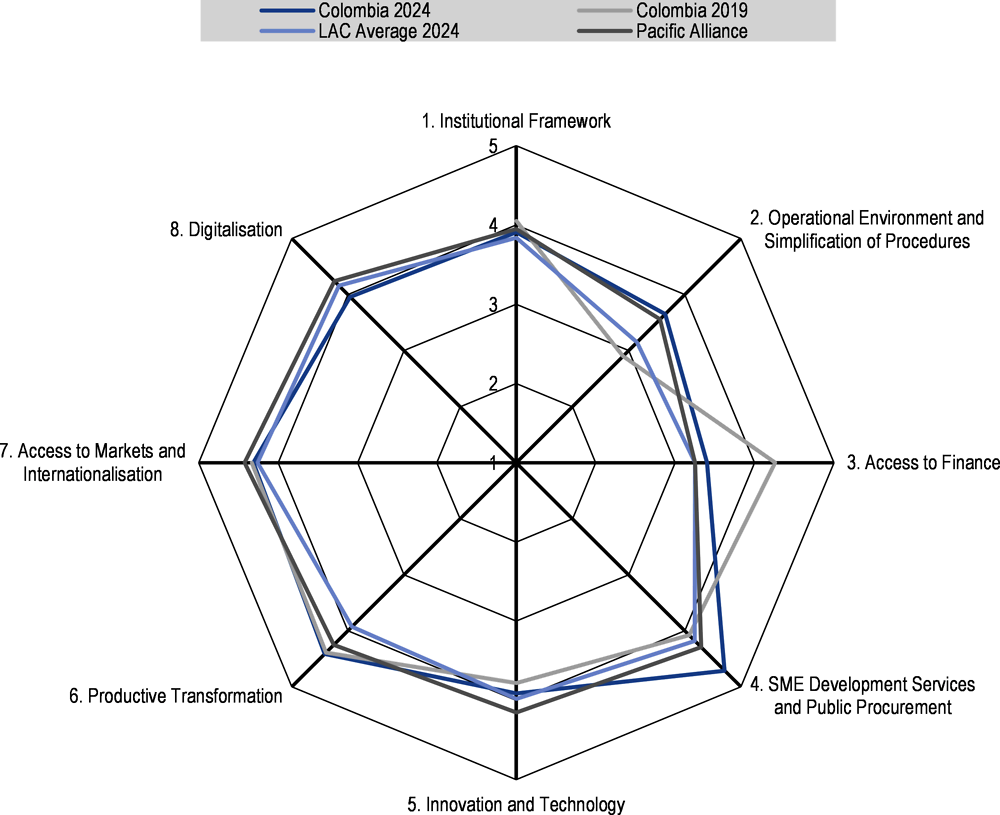

Figure 17.1. 2024 SME PI Colombia's score

Note: LAC average 2024 refers to the simple average of the 9 countries studied in this 2024 report. There is no data for the Digitalisation dimension in 2019 as the 2019 report did not include this dimension.

Colombia demonstrates notable improvement in the second SME Policy Index assessment, surpassing the LA9 average in seven of the eight dimensions assessed (see Figure 17.1). Compared to its 2019 scores, Colombia has enhanced its performance in four dimensions: Operational Environment and Simplification of Procedures (Dimension 2), SME Development Services and Public Procurement (Dimension 4), Innovation and Technology (Dimension 5), and Productive Transformation (Dimension 6). However, challenges persist in Dimension 8, where despite achieving a reasonably strong overall score, largely due to its robust National Digitalisation Strategy, its performance is somewhat hindered by deficiencies in the digital skills framework.

Looking ahead, Colombia could benefit from delineating SME development priorities within the new National Development Plan. These priorities should be translated into realistic, quantifiable, and time-bound objectives, while establishing an effective monitoring and evaluation mechanism—a point that will be further elaborated upon in this chapter.

Context

Colombia exhibits robust macro-economic conditions that facilitated its resilience to the pandemic's impact. The country's prudent fiscal and macro-economic management, anchored by a targeted inflation regime, flexible exchange rate, and a rules-based fiscal framework, enabled a swift economic recovery post-COVID-19 (World Bank, 2021[1]). After reaching pre-pandemic GDP levels by the second half of 2021, Colombia recorded an impressive 11% growth for that year. However, growth moderated to 7.3% in 2022, attributed to a deceleration in domestic demand amidst high inflation, elevated interest rates, tight external financial conditions, and economic slowdowns in trading partners (OECD, 2024[2]). In 2023, the economy faced a further slowdown to 1.2%, primarily influenced by declining investment in sectors like construction and machinery.

Throughout 2022, Colombia faced rising inflation, closing at 13.1%, a continuation of the upward trend observed since late 2020, prompting a restrictive monetary policy. The significant depreciation of the exchange rate during the year, impacting various goods and services, including food, was a notable contributor (BANREP, 2023[3]). Exchange rate pressures were compounded by high demand, surpassing the economy's productive capacity. From March 2023 onwards, inflationary pressures began to ease, ending the year at 9.6%, despite notable increases in energy prices and a 16% hike in the minimum wage. The alignment of domestic gasoline prices with international rates helped alleviate the impact of global oil price fluctuations on public finances (OECD, 2023[4]). Projections indicate inflation at 4.2% in 2024 and 3.0% in 2025 (BANREP, 2023[3]) contingent on the severity of the El Niño weather phenomenon, which may lead to droughts and impact food prices due to crop failures (OECD, 2023[4]).

In 2022, Colombia experienced improvements in its labour market, with the national unemployment rate at 11.2% and the urban rate at 11.4%, marking a decrease of 2.6 percentage points nationally and 3.8 percentage points in urban areas, compared to 2021. Employment dynamics surpassed pre-pandemic levels, driven by increased formal employment and a higher proportion of female employment. All sectors contributed positively to employment generation during 2021-2022. In 2023, the unemployment rate further improved to 10.6%, attributed to the recovery of rural employment and growth in the non-wage segment, characterised by high informality (OECD, 2023[4]).

SMEs in Colombia faced significant challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 66% of businesses experiencing a decline in sales volume, 46% ceasing activities, 40.1% reducing staff, and 52% adopting teleworking or a hybrid work model (ANIF, 2020[5]). In Colombia, SMEs play a crucial role in driving economic growth, transformation, and employment, constituting 93.2% microenterprises, 6.4% SMEs, and 0.4% large enterprises within the formal business structure. Together, micro-enterprises and SMEs contribute approximately 40% to GDP and 65% to employment (OECD, 2022[6]). Colombia, with moderate international trade integration, is involved in numerous free trade agreements, boasting 18 agreements in force. The country has made significant strides in developing operational e-services for businesses and maintaining a well-functioning credit market (OECD/CAF, 2019[7]).

Dimension 1. Institutional Framework

Colombia has successfully established a robust framework for SME policy, evident in its commendable 3.91 overall score in the first dimension. The country boasts a well-developed experience in formulating national development plans that articulate strategic directions for SME policies, along with effective mechanisms for monitoring their implementation. While Colombia has made substantial progress, there remains room for improvement, particularly in refining policy implementation mechanisms, enhancing institutional capacity, and addressing the significant challenge of labour and enterprise informality.

The SME definition, earning a score of 4.33, is based on three parameters: total employment, total annual gross sales, and total assets. These values are denominated in Unidades de Valor Tributario (Tax Value Units), an accounting unit subject to periodic reviews to accommodate inflation. The SME definition, initially introduced in 2004 through Law 905, outlines the scope and institutional framework of SME policy. The definition underwent its latest revision in 2019 and is consistently applied across the public administration.

In the sub-dimension of Strategic Planning, Policy Design, and Coordination, Colombia attains a score of 3.66. The Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo (Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism, MINCIT) specifically the Vice-Minister for Enterprise Development, SME Technical Direction, is entrusted with the SME policy mandate. The regulatory landscape was initially shaped by Law 905 in 2004, establishing the Sistema Nacional de Apoyo a las Mipymes (National Support System for SMEs), which included public institutions, a National Council for micro-enterprises, and a National Council for small and medium-sized enterprises. The subsequent Law 2069 of 2020 introduced modifications, creating the Sistema Nacional de Competitividad e Innovación (National System for Competitiveness and Innovation, SNCI) as a coordinating body for policy actions promoting economic development.

SME policy strategic directions are embedded in the National Development Plan Pacto por Colombia, Pacto por la Equidad (Law 1955 of 2019). The pillars of this plan include initiatives to reduce informality and enhance enterprise productivity, further detailed in MINCIT's Planeación Estratégica Sectorial 2019-2022 (Strategic Sectoral Planning, PES).

The National Development Plan is the document that serves as the basis and provides the strategic guidelines for the public policies formulated by the President of the Republic through his government team. Its elaboration, socialisation, evaluation, and monitoring are the direct responsibility of the Departamento Nacional de Planeación (National Planning Department, DNP).

The new government elected in 2022 has introduced a new national development plan called "Colombia Potencia Mundial de la Vida" which was approved and elevated to the status of Law of the Republic in May 2023. This plan prioritises the recognition and support of the Economía Popular (Grassroots Economy), which encompasses a significant portion of the country's population still facing social and economic inclusion challenges.

On the other hand, the Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social (National Council for Economic and Social Policy, CONPES) is the highest national planning authority and serves as an advisory body to the government in all aspects related to the country's economic and social development. To achieve this, it coordinates and guides the bodies in charge of economic and social management in the government, through the study and approval of public policy documents.

Directly overseeing SME policy implementation, MINCIT collaborates with various institutions, including sectorial chambers, chambers of commerce, local administrations, and other independent bodies. These collaborations are facilitated through convocatorias (calls for proposals) within the frameworks of key programmes which are carried out through: iNNpulsa Colombia and Colombia Productiva, bodies responsible for implementing public policy on SMEs. Notably, there has been no evaluation of the 2018-2022 National Development Plan to date.

Furthermore, Colombia has instituted a system of public consultations for the development of new legislative acts through the electronic portal Sistema Único de Consulta Pública (Unique Public Consultation System, SUCOP), allowing for a 15-day consultation period. The country exhibits a well-established practice of Public-Private Consultations (PPCs), reflected in its 4.18 score for this sub-dimension. The significant involvement of the largest SME association and private sector representatives in legislative processes underscores the collaborative approach.

On another note, efforts to reduce labour and enterprise informality have been central to recent National Development Plans. While these measures have yielded positive results, the informal sector remains substantial, with an estimated 60% of total employment consisting of informal workers. In 2019, CONPES outlined a strategic direction for reducing informality (Document CONPES 3956), which will require revision in alignment with the priorities of the new National Plan of Economic Development (2022-2026). A recently established public-private technical committee, the Comité Técnico Mixto de Formalización (Joint Technical Committee on Formalisation), underscores Colombia's commitment to addressing informality, evident in its 3.69 score for the Measures to Tackle Informal Economy sub-dimension.

The way forward

Define SME development priorities within the new National Development Plan, translating them into realistic, quantifiable, and time-bound objectives. Establish an effective monitoring and evaluation mechanism, involving private sector representatives in all phases of SME policy, including design, elaboration, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation.

Consider the establishment of an SME development agency operating under the supervision of the Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism, but with a large degree of operational autonomy. This agency could oversee conducting entrepreneurial promotion and support programmes, as well as implementing the two main programmes providing SME support: iNNpulsa Colombia and Colombia Productiva.

Define the mandate of the newly established Comité Técnico Mixto de Formalización and consider developing a comprehensive strategy for the reduction of labour and enterprise informality to be part of the country’s national development plan.

Dimension 2. Operational environment and simplification of procedures

The operational landscape for SMEs in Colombia is generally well-functioning, yet there exist areas that have not undergone reform, resulting in complex and time-consuming procedures. Colombia is actively engaged in a regulatory reform policy, incorporating advanced analytical tools. However, the progress of these reforms has been notably hindered by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and a phase of political fluctuations post the 2022 presidential election. The overall score for Colombia in this dimension is 3.65, with specific scores of 3.65 in Legislative Simplification and Regulatory Impact Analysis, 3.82 in Company Registration, 3.20 in Ease of Filing Tax, and an exemplary performance in E-government 4.00, ranking among the top with Mexico and Chile.

Colombia initiated a trajectory of legislative simplification and regulatory reforms in 2012, marked by the approval of Decree 019 of 2012, outlining guidelines for legislative review and the elimination of redundant laws. While progress has been significant in some areas, the overall reform process lacks a systematic approach.

The accession to the OECD in 2020 injected momentum into the regulatory reform process, prompting Colombia to enhance its regulatory tools. In 2020, a new Law on Legislative and Regulatory Reform was enacted, introducing tools such as the Ciclo de Gobernanza Regulatoria. Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA), introduced in 2017, is systematically applied, overseen by the DNP. A methodological guide has been developed, and an SME test is now applied when new legislative or regulatory acts are expected to significantly impact SMEs.

The process of starting a business in Colombia is relatively straightforward. The 10-day timeline involves seven mandatory procedures, with the most time-consuming steps related to registration with entities such as the Family Compensation Fund, National Training Service, Colombian Family Welfare Institute, and the Agency for employees for public health coverage.

Through the online platform Ventanilla Única Empresarial (One-Stop Business Shop, VUE), new companies are assigned a single identification number Registro Único Tributario (Single Tax Register, RUT) by the tax administration, valid for interactions with all public administration bodies. Company creation and registration procedures can be efficiently completed online through the VUE platform.

The tax filing and payment process in Colombia is comparatively complex. Key challenges include the time required for tax filing and payment, significantly surpassing the OECD average, and a high rate of tax and social contributions on profits (71.2% against an OECD average of 39.9%). The 2018 tax reform introduced measures and incentives benefiting SMEs, along with simplified accounting for micro-enterprises. The electronic platform Dirección de Impuestos y Aduanas Nacionales (National Tax and Customs Directorate, DIAN) has further streamlined tax-filing procedures.

Colombia has been proactively implementing its Digital Government Policy, overseen by the Ministerio de Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones (Ministry of Information and Communications Technology, MinTIC). This strategic document aims to provide digital government services for enterprises and citizens, monitored through the Índice de Gobierno Digital (Digital Government Index). The country has already established a commendable array of e-government services for enterprises.

The way forward

Identify areas of relative weakness in relation to the quality of its business environment reform and resume the process of regulatory reform and legislative simplification. The agenda should conduct an in-depth assessment of the business environment, possibly using the same methodology as the OECD regulatory reform tools.

Assess the impact of the recently implemented tax reform and monitor the effective tax rate imposed on different typologies of SMEs as a result of the reform.

Extend the range of available e-government services and implement programmes to promote the uptake of those services by SMEs.

Dimension 3. Access to finance

Colombia achieves an overall score of 3.40 in the Access to Finance dimension, the second highest in the region. Additionally, it scores 3.44 in the Legal, Regulatory, and Institutional Framework sub-dimension, driven by its advancements in the regulation and institutionalisation of tangible and intangible asset registration. The country boasts an accessible online cadastre for the public, documenting ownership of registered pledges. While there is a public registry of security interests in movable assets, it is not available online. However, movable assets are only accepted as collateral by some banks or large borrowers.

Regarding access to financing, legal framework development is propelled by government provisions in the securities market. There is a legal framework for regulating the capital market for SMEs and a separate section in the stock market for these low-capitalisation companies. Nevertheless, there is a lack of a strategy to assist SMEs in meeting listing requirements. Moreover, the country demands a high percentage of collateral for medium-term SME loans, which could affect their access to financing. However, through the National Guarantee Fund, collateral guarantees are provided.

Colombia attains a notable score (4.56) in the sub-dimension of Diversified Sources of Enterprise Finance. Several nationally regulated microfinance institutions are present, along with Bancóldex, the country's business development and import-export bank, the country's business development and export-import promotion bank whose products are widely used by SMEs. Additionally, the National Guarantee Fund, with public and private participation, facilitates SMEs' access to credit by providing bank guarantees when they lack adequate collateral.

Preferential interest rates are offered through rediscount operations for banks that grant loans to SMEs with the aim of passing on part or all of the benefit of the better rate to the end user of the credit, and several incentive mechanisms of finance access for business development are highlighted, such as the Emprender Fund and specific programmes for new sources of financing, such as those offered by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Tourism through multiple entities such as Bancóldex, iNNpulsa Colombia and the Banca de las Oportunidades (Opportunities Banking) programme.

Furthermore, Colombia boasts diverse alternative financing sources based on assets and private equity investment instruments, including crowdfunding mechanisms, private equity, venture capital funds, and angel investors.

On the other hand, Colombia stands out with a solid score of 3.2 in the Financial Education sub-dimension, thanks to its initiatives and programmes aligned with international best practices. SMEs are identified as a central sector in its Estrategia Nacional de Educación Económica y Financiera (National Economic and Financial Education Strategy, ENEEF), with the Banca de las Oportunidades programme responsible for promoting financial education for micro-entrepreneurs.

The CONPES 3956 of 2019 on business formalisation entrusted the Opportunities Banking to establish a roadmap for designing, socialising, and implementing methodologies, materials, and content to promote economic and financial education for SMEs within the framework of the ENEEF. Additionally, the Financial Superintendence of Colombia developed the Non-Formal Financial Education Seal, a distinction for entities supervised by the Superintendency and sector guilds committed to activities, campaigns, and programmes that meet requirements of relevance, quality, and suitability. The SMEs Initiative of the Seal defines the requirements to identify institutional strategies that facilitate access to financial education services for them.

Similarly, within the framework of the ENEEF, initiatives were designed that incorporated private sector needs through an advisory committee coordinated by the Banca de las Oportunidades programme, as well as business perspectives obtained from the SMEs Grand Survey conducted by the National Association of Financial Institutions (ANIF). Additionally, in 2020, the national government introduced the national policy for inclusion and economic and financial education (CONPES 4005 of 2020). This policy aims to integrate financial services into the daily activities of citizens and SMEs, addressing their needs and creating economic opportunities to foster the country's financial growth and inclusion. It outlines an action plan to enhance the provision of relevant financial services to the entire population, thereby contributing to broader economic development and financial accessibility.

At the same time, the Colombian government offers a variety of programmes aimed at entrepreneurs, such as Bancóldex content on financial, management, and corporate governance topics mainly directed at entrepreneurs. One area of opportunity is to implement surveys to measure the financial capacities of SMEs that allow for diagnoses to guide the ENEEF, as well as the design of financial education programmes. Likewise, establish monitoring, follow-up, and evaluation systems for public policy and programmes.

Colombia obtains a score of 2.40 in the sub-dimension of Efficient procedures for dealing with bankruptcy. Although it has universally applicable regulations based on internationally accepted principles, it lacks early warning systems for insolvency situations and the possibility of resorting to less burdensome out-of-court agreements than declaring bankruptcy.

Details of a company declaring insolvency are available in special publicly accessible records. However, Colombia does not establish a maximum time limit for insolvency nor automatically remove this information from records after said period. Similarly, the country does not provide information or specialised training for those seeking a new business opportunity.

The way forward

Promote regulation and institutions so that movable assets are accepted as collateral throughout the financial system. Review downward the weighting of collateral for medium-term loans to SMEs.

Continue the development of the asset register to make systems and information accessible and online and establish a strategy to help SMEs meet listing requirements.

Implement surveys to measure MSMEs' financial capabilities to provide diagnostics to guide the ENEEF, as well as the design of financial education programmes. Likewise, establish follow-up, monitoring, and evaluation systems for public policy and programmes.

Develop early warning mechanisms to make out-of-court settlements for bankruptcy less burdensome.

Promote other out-of-court mechanisms for bankruptcy cases that can be more cost and time efficient.

Design and implement training programmes for second chances, targeting individuals who have had their businesses go bankrupt.

Dimension 4. SME development services and public procurement

With a total score of 4.71, Colombia performs above the regional average in this dimension (4.18). This represents an improvement compared to the 2019 edition, where the total score was 4.08. Progress was driven by improvements in public procurement, which now scores 4.60, compared to 3.64 in 2019, although Business Development Services (BDS) and services for entrepreneurs also registered progress from 4.35 and 4.07 to 4.63 and 4.89, respectively.

As noted in the analysis of Dimension 1, Colombia has an established SME policy system, framed by the Sistema de Apoyo a las PYMEs (National SME Support System) and more recently by the SNCI, with the participation of various government agencies and in consultation with relevant actors, under the leadership of the MINCIT. The national SME policy and consequently its programmes, including BDS and services for entrepreneurs are professedly framed by the National Development Plan 2018-2022, which is being succeeded by a new Development Plan “Colombia Potencia Mundial de la Vida”.

Within the National Development Plan 2018-2022, the "Pacto por el emprendimiento, la formalización y la productividad" focuses on creating a dynamic, inclusive, and sustainable economy through a robust and competitive business sector. The pact aims to foster entrepreneurship and business dynamism, and boost innovation and productive transformation. The design and implementation of business development services for SMEs stem from these strategies.

The main schemes for the provision of BDS in Colombia include iNNpulsa Colombia, which focuses on innovation and entrepreneurship, and Colombia Productiva, which addresses productivity and competitiveness. These initiatives are overseen by the Vice-Ministry for Enterprise Development, SME Technical Direction. Additionally, the National Tourism Fund (FONTUR) focuses on tourism and is coordinated by the Vice-Ministry of Tourism, while ProColombia, which supports foreign investment, tourism, and exports, is coordinated by the Vice-Ministry of Foreign Trade. All three Vice-Ministries are part of MINCIT and in collaboration with chambers of commerce, business associations, universities, and specialised private entities. The principal modality for the delivery of those programmes is that of convocatorias or calls for projects, although some support is also provided through bonos (vouchers) that are exchanged for services through private suppliers or other suppliers in case of specific needs such as digital solutions, productivity increases, etc. The programmes are evaluated at the end of their periods of implementations and the results are used to decide on adjustments or continuity of support. The evaluations are for internal use and are not publicly available.

In addition, the government provides assistance to business incubators through Law 119 of 1994, which states that the Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje (National Learning Service, SENA), should allocate 20% of its income to the development of competitiveness and productive technological development programmes. This includes funding for business incubators. With the information provided for this assessment, however, it was not possible to ascertain the level of operation of a national system of incubators, beyond the business incubator Incubar Colombia.

The public procurement system is governed by Law 80 of 1993 and subsequent regulations, including Law 1150 of 2007 which advanced the introduction of e-procurement through the Sistema Electrónico para la Contratación Pública (Electronic System for Public Procurement, SECOP) and Decree 4170 of 2011 which created the National Agency for Public Procurement (Colombia Compra Eficiente). The system goals include facilitating the participation of SMEs in public procurement, including through set-asides or quotas for SMEs, pre-qualification procedures allowing SMEs to save time and money when bidding for contracts, and technical assistance through information for SMEs to prepare and submit bids. The system also foresees the possibility, but not obligation, to break tenders above a certain size into smaller lots, allowing SMEs to form consortia for joint bidding, favouring SMEs in case of bidding draws, and establishing timely payments of less than 45 days after the issuance of an invoice. According to the information provided for this evaluation, past efforts have led to an increase in the participation of SMEs in public procurement.

The way forward

Continuing the strategic approach towards BDS and ensuring that the new national development plan of the Grassroots Economy serves to articulate the supply of development services for SMEs and entrepreneurs of various types.

Strengthen the delivery of support services for entrepreneurs, including through business incubators and accelerators. Although the responses to the request for information for this assessment show that all boxes are ticked, there is less clear evidence on how effective and extensive the measures are.

Dimension 5. Innovation and technology

The strength of Colombia’s institutional framework for supporting SME innovation contributes to a fairly strong overall score of 3.91 in the Innovation and Technology dimension. There are a number of government entities involved in innovation policy in Colombia, including the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Tourism, the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation, the Ministry of Information Technologies and Communications, Administrative Department for Social Prosperity, and the National Planning Department. The activities of these entities are overseen by a coordinating body, which helps to facilitate synergies and avoid overlap or duplication of efforts. iNNpulsa Colombia, is Colombia’s dedicated innovation agency, focusing on supporting high-potential businesses with scaling potential.

Colombia’s national innovation strategy places a strong emphasis on innovation within SMEs and start-ups. Among the strategy’s goals are facilitating business creation, expanding SMEs’ access to markets, improving access to finance for entrepreneurs, and strengthening the entrepreneurial culture. There is a robust system in place for monitoring the implementation of the national strategy, with six-monthly monitoring reports to be developed until the end of the implementation period in 2025. Another strong point is Colombia’s engagement with key stakeholders including private sector associations and academics in the design of its innovation strategies and policies. These factors contribute to a score of 4.44 in the Institutional Framework sub-dimension, which is the highest in the LAC region.

There is some room for improvement with respect to the Support Services sub-dimension, where Colombia scored a below-average 3.34. Linkages between SMEs and research institutions are supported by MINCIT through its national strategy for Science, Technology, and Innovation Parks. These efforts could be complemented by online tools to connect researchers and SMEs, which are currently not available in Colombia. Also, while there are policies in place to support incubators and accelerators, the number of accelerators in the system appears relatively low and many of the incubators offer a relatively basic package of supports without access to specialised equipment.

Turning to financial supports for innovation, iNNpusla Colombia implements the Aldea and Aldea Escala programmes. These provide innovation vouchers to entrepreneurs that satisfy certain criteria. There are also tax incentives to encourage innovation, including VAT exemptions for the importation of research equipment and tax deductions for investors that engage in innovation projects. However, the number of SMEs that benefit from these measures is relatively low. Colombia’s score for the Financing for Innovation sub-dimension is 3.95.

The way forward

Promoting and adapting tax incentives for innovation to make them more relevant and accessible to SMEs.

Investing in improving the quality of support provided to innovative SMEs through the incubation and acceleration system.

Dimension 6. Productive transformation

Colombia maintains one of the highest performances in the productive transformation dimension among the LA9 countries, with a score of 4.41. This is attributed to its ongoing efforts at both the strategic and programmatic levels, primarily through the sustained implementation of its National Policy for Productive Development 2016-2025 (Document CONPES 3866 of 2016), serving as a guide to propel the country's productive transformation. Although this policy was in its early stages during the 2019 assessment, Colombia has demonstrated strong efforts, especially in monitoring and evaluation, by incorporating a detailed Plan de Acción y Seguimiento (Action and Monitoring Plan, PAS) with quantifiable objectives of defined duration. This comprehensive approach is reflected in Colombia's score of 4.85 for the first sub-dimension.

Colombia's score of 4.36 in the sub-dimension of measures to improve productive associations echoes its performance in 2019. The development of clusters in Colombia initially established in 2012 persists as a well-established integral system within the framework of iNNpulsa Colombia, under the Competitive Routes programme, which involves creating roadmaps aimed at establishing new clusters or strengthening existing ones.

In 2019, the autonomous entity Colombia Productiva was established through the issuance of the National Development Plan 2018-2022 Pact for Colombia, Pact for Equity (see Dimension 1. Institutional Framework). Formerly known as the Productive Transformation Programme, Colombia Productiva operates under the MINCIT with the mandate to promote productivity, competitiveness, and productive linkages. In 2021, Colombia Productiva adopted the Cluster Strategy. This strategic shift led to the creation of the Clúster Más Pro initiative within Colombia Productiva.

The Clúster Más Pro programme aims to provide tools that foster collaborative work among companies, enabling them to enhance their productivity, quality, and sophistication to develop products and services with greater added value. Additionally, the programme seeks to facilitate market expansion or entry, promote the recovery of markets, and generate new public goods.

In addition to this, the Cluster Network Colombia, represented in the form of a website, currently has 148 registered cluster initiatives and 37,728 interconnected businesses. It also serves as a database with information about programmes and calls.

In addition to the Cluster Más Pro strategy and the Colombia Cluster Network, the MINCIT, through Colombia Productiva and in collaboration with chambers of commerce and public-private partners, has launched the Fábricas de la Productividad (Productivity Factories) programme. This initiative contributes to the goal of enhancing productivity, seen as a key driver for accelerating the country's growth.

The programme offers technical assistance and specialised support. The objective of the programme is to address information asymmetry gaps related to enterprise performance and the availability of specialised technical assistance services in the country, which hinder companies from implementing improvements that could enhance their productivity. To this end, the Productivity Factories strategy is built upon three main pillars: (1) provision of support and specialised technical assistance, (2) consolidation of a National Data Base of productivity experts, and (3) development of training activities and personnel. These efforts aim to equip regional personnel with the necessary skills to support companies effectively, while also establishing a network of complementary services provided by public and private partners to further advance the programme's objectives.

Colombia's strong performance in the productive transformation dimension is, to some extent, overshadowed by its score (4.14) in the sub-dimension of integration into global value chains. While the country has developed a supplier development programme that facilitates the inclusion of SMEs in global value chains through call for proposals, similar to those in Uruguay, Chile, and Peru, its design and implementation are hampered by low levels of monitoring and evaluation. These levels lack clear evaluation mechanisms, coupled with a lack of initiatives to raise awareness among SMEs about the potential benefits of participating in global value chains.

The way forward

Examine the outcomes derived from the monitoring and evaluation mechanisms implemented under CONPES 3866 of 2016-2025. This analysis should serve as a foundation for shaping the new productive development plan, drawing insights and lessons from the experiences and impacts of the existing plan.

Extend similar monitoring and evaluation endeavours to encompass initiatives focused on integrating SMEs into GVCs. Systematically promote the potential advantages for SMEs associated with participating in GVCs, fostering a comprehensive understanding of the benefits.

Dimension 7. Access to market and internationalisation of SMEs

Colombia achieves an outstanding score of 4.31 in the market access and internationalisation dimension, thanks to its performance in quality standards (4.49), trade facilitation (4.41) and support for internationalisation programmes (4.64). ProColombia, in charge of promoting non-mining energy exports and services, is crucial in this aspect, contributing to sustainable growth and employment generation.

ProColombia has defined six strategic focuses, including capturing new foreign direct investment opportunities and strengthening the tourism sector. In addition, it actively participates in the strategic pillars of the National Development Plan, focusing on investment, entrepreneurship, and institutional strengthening. ProColombia's portfolio of initiatives includes training and support programmes for exporters, such as the "Export Training" and "Export Motivation" programmes. The "Export Accompaniment" programme offers advice to companies in search of new markets, while "Factories of Internationalisation" seeks to increase exports in a competitive and sustainable manner. During 2022, these programmes provided services to 394 companies, mainly SMEs, with significant results. In addition, digital tools for internationalisation are offered.

On the other hand, Colombia obtained an outstanding score of 4.41 in Trade facilitation, thanks to various initiatives to support exporters. These include export guides provided by MINCIT, ProColombia and Dirección de Impuestos y Aduanas Nacionales (National Tax and Customs Directorate, DIAN), as well as export logistics profiles by country. DIAN continues to implement the Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) programme in Colombia, although participation is more difficult for SMEs due to certification requirements. Colombia has also established Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) with several countries and is part of the Regional MRA of the Americas, thus facilitating foreign trade operations.

To streamline trade, Colombia has installed the National Facilitation Committee, which has generated 415 actions in 2022 with a high percentage of compliance. In addition, efforts have been made to strengthen the Foreign Trade Single Windows (VUCE), with 80% progress towards the goal of inter-operability of information systems.

The Export Access project for goods, developed with the IADB, provides information on non-tariff requirements for SMEs, while Export Access Services provides information relevant to the export of services. Colombia also outperforms the Latin American average in the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators (TFI), with an overall index of 1.638, except for the document’s indicator.

Furthermore, Colombia has obtained a solid score of 3.90 in the use of e-commerce. Since 2019, MINCIT has concentrated its efforts on implementing and expanding this trade modality, accelerating this process during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bancóldex has contributed by offering the free course "E-Commerce: Create your online shop".

At the Andean Community level, work has been done on the proposal of a general regulatory framework for e-commerce. ProColombia has facilitated the participation of Colombian companies in marketplaces through its "Colombia a un Clic" programme, generating sales of USD 33 million since 2019. On the other hand, the alliance between Compra Lo Nuestro and StoreON provides benefits to Colombian SMEs to boost their online sales. In 2020, Decree 1692 was enacted, which regulates low-value payment systems, promoting transparency, innovation, and user protection.

Similarly, Colombia stands out in the quality standards sub-dimension with a score of 4.49. During 2022, significant actions were implemented, such as the "Co-financing Programmes on Quality Certificates for Exporting" and "Training and Technical Support Programme on Quality for SMEs", with an investment of approximately USD 1.9 million, benefiting 1,474 companies. The objective was to strengthen the institutions that form part of the country's quality infrastructure and promote the adoption of the highest quality standards.

Through the "Quality for Export" programme, non-reimbursable co-financing resources were provided to firms and laboratories to obtain international quality certifications. To date, 52 companies have obtained quality certifications required to access international markets, and 5 laboratories have accredited tests required for exporting.The "Quality for Growth" programme, led by MINCIT and Colombia Productiva, launched four calls for proposals that benefited close to 700 companies, including SMEs, productive units and laboratories. These initiatives enabled companies to raise their quality standards, improve their productivity and prepare their offer for the most demanding markets. In addition, through the "Quality Training" project, specialised training and technical assistance was provided to SMEs in strategic sectors, preparing them to meet the quality standards of their industries and compete in international markets. This initiative is supported by the Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación (Colombian Institute of Technical Standards and Certification, INCOTEC) and the Subsistema Nacional de la Calidad (National Quality Subsystem, SICAL).

Finally, in the regional integration sub-dimension, Colombia obtained a score of 3.60 as a result of its integration efforts. Of particular note is the Pacific Alliance's SME Technical Group, which seeks to promote crowdfunding, encourage trade between creative industries, promote the digitalisation of SMEs, establish a network of business incubators, and strengthen capacities for cross-border e-commerce. In the context of the Andean Community, the creation of the Andean Observatory for the Business Transformation of SMEs was approved and the preparation of a study to diagnose regional value chains was coordinated, with the aim of strengthening productive integration in the region.

The way forward

Promote the seamless integration of digital platforms and key actors such as AEO in the trade facilitation ecosystem. This will simplify logistical processes and unify information and dissemination of its benefits to SMEs.

Integrate the e-commerce promotion strategy into SME sector development plans, with quantifiable and measurable objectives, in order to achieve better coordination and monitoring of the policies implemented.

Enhance the benefits of sub-regional integration through standardised SME trade promotion and internationalisation programmes, with inter-operability between the different export promotion agencies of the Pacific Alliance.

Strengthen evidence-based decision-making for the design, implementation, and adjustment of public policies, through rigorous monitoring and evaluation. This guideline promotes a more efficient public-private information flow, improves policy outreach, and promotes transparency.

Dimension 8. Digitalisation

Colombia achieves a reasonably robust overall score of 3.96 in the Digitalisation dimension, predominantly attributed to the strength of its National Digitalisation Strategy, although it is somewhat diminished by deficiencies in the digital skills framework.

Colombia's digital transformation journey is guided by a comprehensive National Digitalisation Strategy (NDS), which seeks to utilise technology for economic growth, social development, and innovation. Anchored in the Digital Transformation Framework for the State introduced by the MinTIC, Colombia's NDS prioritises the reimagining of processes, products, and services through digital means. Outlined in the National Development Plan 2022 - 2026, the strategy concentrates on harnessing emerging technologies, bolstering human capital, and cultivating conducive conditions. It promotes digital innovation across public and private sectors, propelling the nation towards a future defined by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. These factors contribute to an impressive score of 4.80 in the National Digitalisation Strategy sub-dimension.

Colombia's score in the Broadband Connection sub-dimension is 3.94. Ambitious connectivity initiatives are outlined in the National High-Speed Connectivity Project, launched in 2022. This project acts as a digital lifeline, connecting 28 municipalities and 19 non-municipalised areas, primarily in the Orinoco, Amazon, and Pacific regions of Chocó. The deployment of high-speed satellite and terrestrial networks has overcome geographical limitations, ensuring that even remote areas are integrated into the digital landscape. Notably, the project integrates various digital access points, including public institutions, digital kiosks, and free WiFi zones, promoting equitable digital access and empowering communities.

There is room for improvement in the Digital Skills sub-dimension, where Colombia scored a below average 3.13. Initiatives such as the ICT Women for Change programme, led by the Ministry of ICTs, exist as catalysts, nurturing women's leadership and entrepreneurial spirit through free training sessions. By offering courses on essential business tools and content creation, it enhances employability, competitiveness, and innovation among women entrepreneurs. Additionally, virtual open courses (MOOC) are made available to civil servants, fostering a culture of continuous learning and upskilling within the public sector.

The way forward

The government could strengthen support for SME digitalisation by:

Advocating for the development of a dedicated SME Digitalisation Strategy within the overarching national plan can ensure a more nuanced approach to addressing the unique needs of small businesses. This should involve consultations with diverse stakeholders, both public and private, to gather insights that shape the development of policies supporting SMEs.

Enhance data transparency and standardisation of indicators to facilitate more accurate and comparable assessments of digitalisation progress across the region.

References

[5] ANIF (2020), La Gran Encuesta Pyme, Lectura Nacional, Centro de Estudios Económicos Anif, https://www.anif.com.co/encuesta-mipyme-de-anif/gran-encuesta-pyme-nacional/.

[3] BANREP (2023), Informe de política monetaria, https://repositorio.banrep.gov.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.12134/10591/informe-politica-monetaria-enero-2023.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2024).

[2] OECD (2024), Real GDP forecast (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/1f84150b-en (accessed on 13 March 2024).

[4] OECD (2023), “Colombia”, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/e2f39dc4-en.

[6] OECD (2022), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2022: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e9073a0f-en.

[7] OECD/CAF (2019), Latin America and the Caribbean 2019: Policies for Competitive SMEs in the Pacific Alliance and Participating South American countries, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d9e1e5f0-en.

[1] World Bank (2021), Colombia overview, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/colombia/overview.