This chapter provides an assessment of Peru. It begins with an overview of Peru’s context and subsequently analyses Peru’s progress across eight measurable dimensions. The chapter concludes with targeted policy recommendations.

SME Policy Index: Latin America and the Caribbean 2024

19. Peru

Abstract

Overview

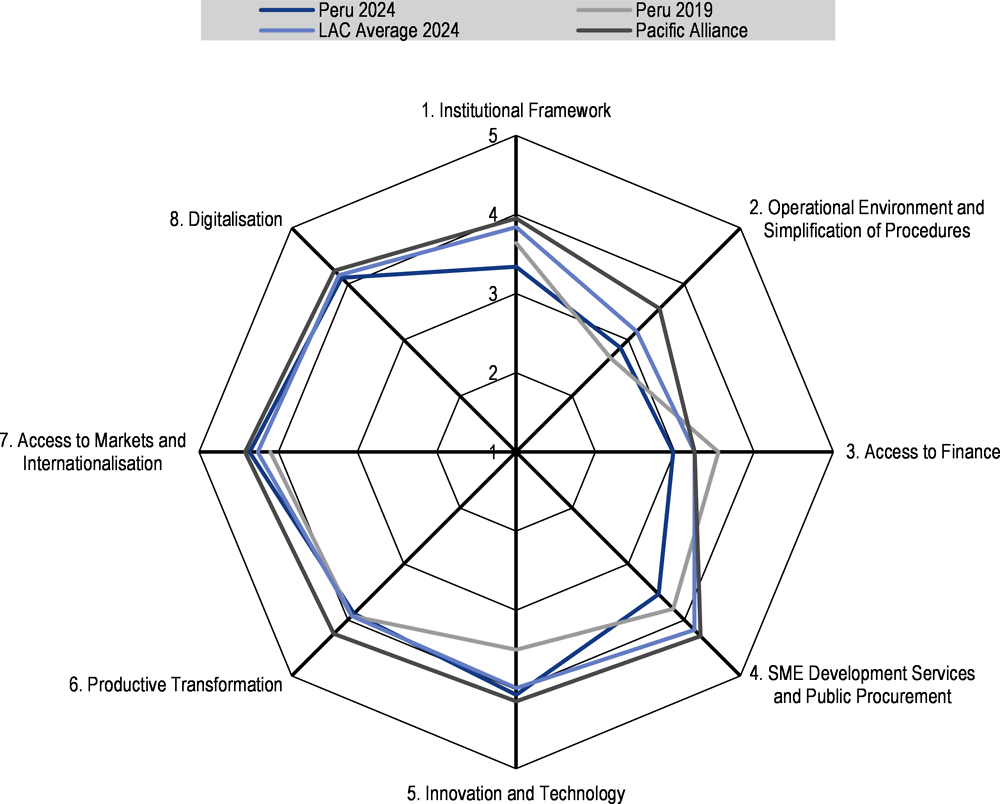

Figure 19.1. 2024 SME PI Peru's score

Note: LAC average 2024 refers to the simple average of the 9 countries studied in this 2024 report. There is no data for the Digitalisation dimension in 2019 as the 2019 report did not include this dimension.

Peru's performance in the second edition of the SME Policy Index (SME PI) demonstrates the various efforts and programmes the country has in place for SME development. Overall, Peru's performance stands out in the dimensions of Innovation and Technology (Dimension 5) and Market Access and Internationalisation (Dimension 7), where it has improved from the 2019 assessment and scored above the regional average. However, the country still faces particular challenges in the dimension of Operational Environment and Simplification of Procedures (Dimension 2). Although it has improved its score compared to its participation in 2019, mainly due to the development of its e-government services, it is still below the regional average.

Peru has maintained a well-established framework for SME policy and demonstrated commendable practices in medium-term policy planning. The country offers an extensive range of programmes and initiatives to support SME development, often featuring clear and time-bound objectives. However, challenges remain in the implementation and monitoring of these policies and programmes, making it difficult to assess the overall impact of SME support measures.

Looking ahead, as further detailed in this chapter, Peru could build on the foundation of the Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Nacional – Perú 2050 by developing a medium-term strategy for SME development. This strategy could be formulated in consultation with private sector representatives and international organisations. The plan could benefit from the incorporation of realistic and quantifiable objectives while strengthening the implementation mechanisms of its various SME support programmes, ensuring their alignment with strategic orientations.

Context

The Peruvian economy faced an 10.8% contraction due to the pandemic in 2020, followed by a recovery of 13.3% in 2021, driven by domestic demand, growth in productive sectors, and increased current income. By 2022, the economy slowed to 2.7%, (OECD, 2024[1]). Factors such as social conflicts, political uncertainty, and adverse weather conditions affected business confidence and slowed private investment in non-mining sectors, while mining investment contracted due to the absence of new large-scale projects (BCRP, 2022[2]).

Various factors, including weather disruptions and supply shocks, led to a peak inflation rate of 8.8% in June 2022. In response, the Banco Central de Reserva del Perú (Central Reserve Bank of Peru, BCRP) increased the benchmark interest rate by 500 basis points throughout 2022, reaching 7.5% (BCRP, 2022[2]). By end 2023, the inflation rate returned to a level within the inflation target, reporting 3.1%. The decline was driven by the rapid reversal of the impact of supply shocks on food prices observed in the second half of the year. The fiscal deficit, after reaching 1.7% of GDP in 2022, increased to 2.7% in 2023 (BCRP, 2023[3]).

In terms of employment, national formal jobs and the wage share increased in 2023 compared to 2022 (INEI, 2023[4]). However, there is a marked downward trend in job growth rates due to the fall in employment in the agricultural sector affected by El Niño (BCRP, 2023[3])).

Furthermore, Peruvian SMEs, constituting 99.5% of all firms and generating 90% of the economically active population in the private sector, were significantly impacted by the 2020 crisis. The number of formal enterprises contracted by 25.1% in 2020. To address this, the government launched financing programmes to help SMEs cope with the liquidity crisis. In 2023, the business fabric reached 3.2 million; however, there were more divestitures than additions during this year (INEI, 2023[5]). Trade and services activities account for 86.5% of SMEs, while manufacturing, construction, mining, and agricultural activities make up the remaining 13.5% (INEI, 2023[5]). Peru has 24 trade agreements in force with major partners such as China, the United States, South Korea, Canada, and Japan (MINCETUR, n.d.[6]).

Dimension 1. Institutional Framework

Until recently, Peru has upheld a reasonably well-established framework for SME policy and exhibited commendable practices in medium-term policy planning. However, persistent political instability has disrupted the planning and implementation of policies, while limiting the frequency of Public-Private Consultations (PPCs). Additionally, the expansion of the already large informal sector has posed challenges to the effectiveness of SME policies, resulting in a score of 3.34 for the Institutional Framework dimension.

Peru's SME definition (score: 3) relies on a singular criterion: total sales. These values are converted into Unidades Impositivas Tributarias (Tax Units, UIT) and are adjusted to account for inflation. This definition is universally adopted by all public entities and has remained unchanged since 2013. During this period, the inclusion of a second parameter—total employment—was discontinued due to challenges in collecting reliable employment data. Micro and small enterprises are mandated to register with the national Registro Nacional de Micro y Pequeñas Empresas (Register of Micro and Small Enterprises) to access public-sector support programmes and benefits.

Peru's score for the sub-dimension of Strategic Planning, Policy Design, and Coordination which scores 3.01 is below the average of LA9. The SME policy mandate in Peru is entrusted to the Ministerio de la Producción (Ministry of Production, PRODUCE), specifically under the purview of the Dirección General de Desarrollo Empresarial (General Directorate of Entrepreneurship Development, DGDE). The institutional framework for SME policy is defined by DS 013–2013 of the Ley de Impulso al Desarrollo Productivo Crecimiento Empresarial (Law for the Promotion of Productive Development Business Growth).

As of now, Peru lacks a medium-term SME Development Strategy. The strategic guidelines and objectives for SME policy until 2021 were outlined in the Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Nacional (Strategic National Development Plan, PEDN), which implicitly addressed aspects relevant to SMEs. Additionally, the Plan Estratégico Sectorial Multiannual (Multiannual Strategic Sector Plan, PESEM) was formulated and supervised by PRODUCE. The Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico (National Centre for Strategic Planning, CEPLAN) was responsible for overseeing the plan's implementation.

In 2022, the government approved a long-term development plan, the Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Nacional–Perú 2050, created by CEPLAN. This plan outlines strategic directions for the country's social and productive transformation, including aspects related to competitiveness, innovation, and digital transformation that indirectly impact SME policy. The absence of a medium-term plan, coupled with persistent political instability, has led to the introduction of ad hoc measures by the DGDE in response to specific policy issues.

The coordination and consultation of SME policies in Peru are overseen by the Consejo Nacional para el Desarrollo de la Micro y Pequeña Empresa (National Council for the Development of Micro and Small Enterprises, CODEMYPE). This council comprises representatives from different ministries (Economy, Agriculture, Production, Foreign Trade, Tourism, among others), local governments, and private sector associations. However, its influence and coordination capabilities have been relatively weak.

Other institutions involved in the implementation of SME policies include the Instituto Tecnológico de la Producción (Technological Institute of Production), specifically through the CITES. Key programmes, such as the Programa Nacional Tu Empresa, Proinnóvate, and the Programa Nacional de Diversificación Productiva, are designed with a focus on micro and small-scale enterprises. Nevertheless, current financial and human resources allocated to these programmes are considered insufficient to meet the needs of the SME sector.

Peru receives a score of 3.82 in the PPCs sub-dimension. While the country has had a programme for general citizen consultation since 2009, focusing on the development of new legislative and regulatory acts as part of the government's transparency policy, the standard consultation period lasts for 30 days, and there is no centralised portal for collecting citizen views. Micro and small enterprises are engaged in consultations during various phases of legislative and regulatory act development, with PRODUCE extending invitations for feedback. The primary consultation channel, CODEMYPE, previously organised regular meetings supported by a secretariat within the DGDE, but political instability has disrupted this process.

Furthermore, Peru faces a significant challenge with a large informal sector, as reflected in its score of 3.86 in the Measures to Tackle Informal Economy sub-dimension. Recent data from PRODUCE indicates that enterprise informality is as high as 86.5%. Despite positive employment data, the informal sector has increased, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The government's focus is primarily on reducing labour informality, with specific programmes implemented by the Ministerio de Trabajo y Promoción del Empleo (Ministry of Labour and Employment Promotion, MTPE), supported by international organisations like the International Labour Organization (ILO). The main instrument to address enterprise informality is the Programa Nacional Tu Empresa of PRODUCE. However, limited funding and coordination with other institutions pose challenges.

The way forward

Enhance the SME definition by incorporating additional parameters, such as employment and total assets. Improve the exchange of data between the tax administration, the MTPE, and PRODUCE to obtain reliable information on firm size.

Develop a medium-term strategy for SME development within the framework of the Plan Estratégico de Desarrollo Nacional – Perú 2050, in consultation with private sector representatives and international organisations. The plan should incorporate realistic and quantifiable objectives, include a section on monitoring and evaluation, and address the reduction of enterprise informality.

Resume and institutionalise PPCs through the CODEMYPE system. Ensure that consultations are open to all categories of SMEs.

Evaluate the measures implemented so far for reducing informality and elaborate a comprehensive medium-term plan for the reduction of labour and enterprise informality, considering the results of the evaluation exercise.

Dimension 2. Operational environment and simplification of procedures

SMEs operating in Peru encounter a challenging operational environment, as indicated by the overall dimension score of 2.86. The complexity of procedures, especially in starting a business (Company Registration 2.89) and filing and paying taxes (Ease of filing taxes 2.33), contributes to the difficulties faced by businesses. The regulatory reform process has faced challenges in recent years, experiencing a slowdown. However, there is progress in the provision of e-government services, reflected in the E-government score of 3.88.

Peru scores 2.60 in the Legislatives Simplification and Regulatory Impact Analysis sub-dimension. SMEs operating in Peru encounter a relatively complex and restrictive environment with a high administrative burden.

While the government states the presence of a regulatory reform plan, it could benefit from more clearly defined objectives, priorities, and a well-structured implementation timeline. Additionally, less than 25% of legislation related to private sector enterprise activities has been revised so far. Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) has been adopted since 2017, with each line ministry responsible for conducting RIA during the legislative and regulatory elaboration phase. The Comisión Multisectorial de Calidad Regulatoria (Multisectoral Regulatory Quality Commission, CMCR) oversees the application of RIA, and all RIA analyses are made publicly available.

For the registration process, it involves the intervention of a notary, as the business founder must sign the deed of incorporation before a Public Notary. This step significantly increases the overall cost of the process. Additionally, obtaining a Certificado de Inspección Técnica de Seguridad en Edificaciones (Technical Inspection Certificate for Safety in Buildings, ITSE) and obtaining the operating license from local authorities takes a considerable amount of time (14 days).

An enterprise in Peru is assigned two identification numbers for interactions with the public administration. The first is the registration number issued by the Superintendencia Nacional de los Registros Públicos (National Superintendency of Public Registries, SUNARP), and the second is issued by the tax administration upon registration of the enterprise in the Registro Único del Contribuyente (Single Taxpayer Register, RUC). While there is no One-Stop-Shop (OSS) in place, the Centro de Mejor Atención al Ciudadano (Centres Improved Citizen Services, MAC) offers orientation services and assistance to new entrepreneurs. To enhance its services, SUNARP has introduced the Registro Centralizado de Reclamos (Centralised Complaints Registry) to address dysfunctions in the registration procedures and improve the monitoring of the company registration process.

Regarding taxes, as highlighted in the 2019 SME PI report, the main issue is the time required for tax filing, which is 260 hours per year, well above the OECD average of 158.8 hours. No new tax reform has been introduced since 2019. Instead, the tax administration has increased actions directed at providing assistance to taxpayers and applying risk management techniques.

In a positive development, Peru has made considerable progress in developing e-government services. The country launched its first initiative to promote digital government in 2014 with the Cero Paper Initiative and established the Secretaria de Gobierno y Transformación Digital (Secretary of Government and Digital Transformation).

The digitalisation of public services remains one of the main government objectives. Over the period 2021-26, the government intends to accelerate the digital transformation of the public sector by upgrading the technology and improving the governance system. In 2022, Peru transitioned from high to very high in the UN Electronic Government Development Index. The country ranked 59 out of 193 countries surveyed.

The way forward

Clarify the objectives of its current regulatory reform plan and focus on areas of relative weakness. Simultaneously, it should take steps to introduce an SME RIA test to evaluate the impact of new laws and regulations on different classes and typologies of SMEs.

Take action to further simplify the company registration process and reduce associated costs, eliminating the need for notary services wherever possible.

Implement measures to simplify tax declaration and tax payment procedures and expand its online services.

Dimension 3. Access to finance

Peru achieves an overall score of 2.98 in the Access to Finance dimension. In the Legal, Regulatory, and Institutional Framework sub-dimension, it scores 4.13, surpassing the regional average. This success is primarily attributed to advancements in securities market regulation, the development of the asset register, and a strong focus on collateral. Notably, Peru has minimal regulation on the percentage of collateral required for medium-term loans to SMEs.

While Peru shows progress in the regulation and institutionalisation of the asset registry, there are areas for improvement. The cadastre and the registry of collateral rights over movable assets are available online, but their overall functionality is limited. Furthermore, the ownership of pledges is not adequately documented, and the acceptance of movable assets as collateral is selective, limited to large borrowers and some banks.

The development of the legal framework in terms of access to finance benefits from government provisions on the securities market. Although there is no specific regulation for SMEs in the capital market, there is a separate segment for small-cap companies with strategies designed to facilitate their compliance with listing requirements. Peru scores 3.24 in the sub-dimension of Diversified sources of enterprise finance. However, it faces significant challenges in the sub-sub-dimension of bank credit and traditional debt products, which affects its overall rating. The absence of export finance systems available to SMEs is a critical factor, despite plans to implement such facilities in the future.

In terms of guarantees, Peru has the presence of FOGAPI, which aims to facilitate access to credit by providing guarantees to financial intermediaries when entrepreneurs lack sufficient assets as collateral. The country also has several microfinance savings and credit institutions operating nationwide. Additionally, the Peruvian government promotes other financing mechanisms for SMEs, such as crowdfunding, regulated through the "Reglamento de la actividad de Financiamiento Participativo Financiero y sus sociedades administradoras." However, the current regulation presents barriers that discourage the creation of new crowdfunding companies and platforms, including a lengthy registration process, high minimum equity requirements, and funding thresholds that could be more flexible. Improving regulation to allow new institutions to enter the market and expand the range of services offered would particularly benefit the SME sector.

In the Financial Education sub-dimension, Peru scores 2.40. Although the country has conducted measurements of the financial capabilities of the general population, most assessments have not specifically focused on the knowledge of microentrepreneurs. Peru conducted financial capability surveys in 2012, 2019, and 2023, supported by CAF and in collaboration with the Superintendency of Banks, Insurance, and Pension Fund Administrators, using the OECD's established methodology. Additionally, the financial literacy of school-age youth (15 years old) has been measured as part of the OECD's PISA assessments.

Peru has integrated Financial Education and entrepreneurship programmes as compulsory subjects in the secondary school curriculum. The country has defined indicators for the follow-up, monitoring, and evaluation of financial education programmes for SMEs, alongside a detailed monitoring strategy that discloses the results of available baselines. Impact evaluations of financial education programmes have been conducted, led by the Ministry of Education and the Superintendency of Banks of Peru (SBS), with results helping to adjust ongoing programmes.

In the sub-dimension of effective procedures for handling bankruptcy or insolvency situations and mechanisms to facilitate the productive reintegration of affected entrepreneurs, Peru scores 2.15. The country has a regulatory framework with universally applicable laws, based on internationally recognised principles, extending even to state-owned enterprises. Additionally, there is a public register of insolvent and bankrupt companies, an early warning system for insolvency situations, and the possibility of resorting to out-of-court settlements that are less burdensome than declaring bankruptcy.

Peru also has regulations for secured transactions, prioritising payments when the assets of the bankrupt company are liquidated. However, improvements are needed in allowing secured creditors to seize their collateral after reorganisation and imposing restrictions, such as requiring creditor consent when filing for reorganisation. Post-bankruptcy, there is no maximum time limit for insolvency, nor an automatic system for removing this information from insolvency and credit record registers once the period has elapsed. Additionally, there is no capacity-building programme for entrepreneurs whose businesses have failed, although a corrective regime known as the surveillance regime exists in collaboration with the SBS.

The way forward

Strengthen the cadastre to make it functional, publicly accessible, and online, make the registry of security rights in movable assets accessible and online, and ensure that ownership of pledges is documented.

Develop special capital market regulation for SMEs and strengthen the strategy to help SMEs meet listing requirements.

Develop export finance systems with a specific focus on SMEs.

Promote the implementation and start-up of alternative financing mechanisms for SMEs. Crowdfunding, for example, although regulated, is difficult to implement in practice due to a lengthy process, high minimum equity requirements and funding limits that could be more flexible.

Conduct regular financial capability surveys for SMEs in order to have updated information for the design of financial education programmes, as well as design and implement a follow-up, monitoring and evaluation system for both policy and programmes.

Strengthen the system for handling bankruptcy through a capacity-building mechanism for entrepreneurs whose businesses have failed, and allowing secured creditors to seize collateral after reorganisation.

Create an automatic mechanism that removes companies and individuals from official bankruptcy and insolvency registers when the situation is resolved, in line with international best practices.

Establish maximum time limits for insolvency (international experience indicates that up to 3 years is a good length of time for such proceedings).

Dimension 4. SME development services and public procurement

The total score of Peru in this dimension is 3.54, which is below the regional average of 4.18. The highest performance is in the sub-dimension of Business Development Services (BDS), with 3.73, followed by public procurement with, 3.60 and entrepreneurial development services, with 3.29. This represents a fall in performance with respect to the 2019 SME PI, when Peru registered a total score of 3.80.

As noted in Dimension 1. Institutional Framework, Peru does not have a medium-term SME development strategy, which hampers the strategic orientations and coordination efforts for BDS and entrepreneurship support. The Strategic Plan for National Development - Peru 2050 contains the broad economic and social development priorities, including on competitiveness, innovation, and digitalisation, but does not comprise direct or explicit links to SME policy and hence business development services. According to the information provided for this assessment, the strategic directions for BDS are framed by the Strategic Institutional Plan of PRODUCE, which is an institutional document and not an SME development plan or strategy. Furthermore, there are no up-to-date analyses of the demand and supply for the provision of BDS in the country.

The information on the BDS available is scarce. The only reference provided in the questionnaire for this assessment is the Programme Proinnovate, which provides co-financing for innovation, productive development, and entrepreneurship. The website of PRODUCE provides information on other projects and programmes, including access to markets (Articulando Mercados), innovation (ProInnóvate), digitalisation (Kit Digital), business planning and technology transfers (Procompite), management (Tu Empresa), entrepreneurship (Startup Perú), etc. According to the responses to the questionnaire, the financial resources available for those programmes are not enough for the needs of SMEs in the country.

Public procurement is governed by Law 30225, which includes a few items on the participation of SMEs, including the possibility to form consortia and establishing a time limit of up to 15 days to pay for goods and services. Law 31535, amends Law 30225 to incorporate the cause of "impact on productive or supply activities due to health crises" as a criterion for reducing penalties for micro and small enterprises that have not been able to carry out their activities as a result of COVID-19. No other information or programmes are available on public procurement and SMEs.

The scarcity of content in the responses to this assessment and the limited and scattered availability of public information concerning this dimension indicate that there is ample margin for Peru to increase its performance in BDS, services for entrepreneurs and public procurement.

The way forward

Some key points going forward include:

Considering the strategic policy orientations for the provision of BDS and services for entrepreneurs and startups, including by linking small business support to the wider national development plan and devising concrete measures, targets and expected outcomes. Such a strategic approach goes beyond the current practice of linking BDS strategy to the institutional plan of PRODUCE only.

Expanding the offer of BDS, particularly those addressed to entrepreneurs and start-ups, which are much more limited than the support provided to the general SME population. Peru could also consider providing more structured and detailed information on the services available and undertake updated studies on the needs of small businesses and entrepreneurs.

Introducing more explicit support measures for SMEs to participate in public procurement. The existing framework comprises very few precepts to facilitate and encourage this.

Dimension 5. Innovation and technology

Peru has seen a notable improvement in the Innovation and Technology dimension, with its score rising from 3.50 in 2019 to 4.07 in 2023. This marks the largest increase in the LAC region. The major driver of this trend is the Institutional Framework sub-dimension, the score for which rose from 2.98 in 2019 to 4.21 in 2024.

The Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica (National Council of Science, Technology and Technological Innovation, CONCYTEC) is the governing body for Peru’s Sistema Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica (National System of Science, Technology and Technological Innovation, SINACYT). SINAYCT also comprises a range of other entities from the public, private and academic sectors, including the Consejo Consultivo de Investigación y Desarrollo (National Advisory Council for Research and Development, CONID), public research institutes, and public entities that provide funding or incentives for innovation. Peru has shown progress since 2019 in the institutional framework of the Innovation System, with ProInnóvate and ProCiencia representing a redefinition of entities fostering and supporting innovation. ProInnóvate has a mandate to implement initiatives to support innovation, technological development, productive development, and innovative entrepreneurship, with the aim of creating a more consolidated framework for innovation support, while ProCiencia is considered the entity linked to the promotion of R&D.

There are a range of supporting instruments available to SME innovators in Peru, contributing to an above average score of 3.94 in the Supports Services for Innovation sub-dimension. Publicly funded science parks, innovation centres, incubators, and accelerators all form part of Peru’s innovation strategy, laws, or policies. Innovative SMEs can also benefit from an online database of researchers, which can be used as a tool for forming collaborative research initiatives. Furthermore, ProInnóvate Programa de Apoyo a Clusters (Cluster Support Programme) aims to strengthen interrelationships between companies in the same geographical area or value chain by awarding co-financing for selected cluster initiatives.

Peru’s scores 4.06 in the Financing for Innovation sub-dimension. There are numerous sources of financial support to help SMEs to conduct innovation. These include ProInnóvate’s direct co-funding supports – which target high-growth enterprises and women entrepreneurs as some of its strategic lines of action– as well as the tax incentives contained within Law No. 30 309. Moreover, there is currently a proposal for the introduction of a public procurement for innovation scheme, as a demand side support for SME innovation. However, Peru’s score in this sub-dimension is reduced by the relatively low uptake of R&D tax incentives by SMEs, as well as weaknesses or gaps in the monitoring and evaluation of financing for innovation programmes.

The way forward

Going forwards, Peru could consider:

Identifying and addressing barriers to SMEs’ uptake of R&D tax incentives.

Conducting reliable impact evaluations of ProInnóvate’s major programmes, including its provision of financial supports for SME innovation.

Dimension 6. Productive transformation

Peru continues to make evident efforts to enhance the productivity and competitiveness of SMEs, resulting in a slightly decreased score of 3.89 in the productive transformation dimension. This decline is largely attributed to methodological changes when compared with the assessment conducted in 2019. Currently, the strategic directions for the country's productive and social transformation are outlined in the Strategic Plan for National Development - Peru 2050, as detailed in Dimension 1. Institutional Framework. Simultaneously, the Budgetary Programme 00993 for the Productive Development of Enterprises stands out as a budgetary instrument that enables the coordination of spending within the Production sector to deploy services for the benefit of SMEs. Additionally, the National Competitiveness and Productivity Plan 2019-2030 has a persistent influence that cuts across various aspects, including its impact on SMEs. The combination of all these efforts, together with their detailed action plans outlining specific objectives and time-bound quantifiable targets, is reflected in the 4.00 score for the Strategies to Enhance Productivity sub-dimension.

Peru continues its active involvement in the Cluster Support Programme, an initiative operated by ProInnóvate. This commitment is reflected in a score of 3.99 for the Measures to Encourage and Support Productive Associations sub-dimension. This programme functions as a call for proposals and involves co-financing with non-refundable resources. Structured in two sequential components, the first component, Dynamisation of Selected Cluster Initiatives, focuses on mapping, diagnosis, and strategic planning activities. The second component, Implementation of Competitiveness Strengthening Plans, centres on the development and implementation of prioritised sub-projects. Despite the 2019 assessment lacking data on the monitoring and evaluation aspects of the programme due to its recent nature, there remains a noticeable absence of publicly available records regarding monitoring mechanisms. This signifies a significant area for improvement in tracking and evaluating the programme's impact. Nonetheless, the results of the calls for proposals are accessible on the programme's official website.

In terms of industrial parks, including the national system, PRODUCE is the governing body in this area, responsible for coordinating with competent entities at all levels of government. Presently, Peru's national parks feature a One-Stop Shop for user services, as well as innovation and technology transfer services provided by ProInnóvate and the Instituto Tecnológico de la Producción (Technological Institute of Production, ITP). Within the National Competitiveness and Productivity Plan, Objective 6 of the nine outlined objectives incorporates fourteen measures, with 6.3 titled "National Strategy for the Development of Industrial Parks." This measure aims to ensure the implementation of a network of industrial parks at national level. Presented in 2020, this strategy encompasses a dedicated section that delineates strategic objectives, guidelines, lines of action, and a matrix of indicators and targets, contributing to the monitoring and evaluation section. This reflective approach underscores a policy characterised by well-coordinated elements in this area.

Peru's efforts in performance in the Integration into Global Value Chains (GVC) sub-dimension (3.80) are currently guided by the National Export Plan - PENX 2025. Among its pillars, the Internationalisation of companies takes precedence, specifically in line 1.3, addressing the Insertion in GVCs. This involves various activities, including mapping, monitoring, and systematisation of GVCs established in international markets. Additionally, the plan emphasises the formation of strategic alliances with commercial partners for the development of joint supply projects for multi-regional and global companies. Furthermore, it underscores the measurement and monitoring of Trade in Value Added (TiVA) indicators, following the OECD methodology. An element to highlight in this plan is that it drew from the lessons learned in the previous plan, incorporating new mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation, as well as fostering interaction with various stakeholders through dialogue forums. Simultaneously, Peru had a Supplier Development Programme that followed similar schemes to those in other countries in the region. However, at the time of this evaluation, there is no information available regarding its continuity, with the last recorded call being in 2019.

The way forward

Establish monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for the Cluster Support Programme to effectively track and assess its impact.

Continue the Supplier Development Programme, incorporating lessons learned from the previous call and making information publicly available.

Dimension 7. Access to market and internationalisation of SMEs

Overall, Peru registers a good performance in the Access to market and internationalisation dimension, with a score of 4.36. Heterogeneous results stand out in the sub-dimensions, especially in support programmes for internationalisation and trade facilitation.

In terms of Support programmes for internationalisation, Peru achieved a score of 4.91 thanks to the implementation of a solid strategy led by the Commission for the Promotion of Peru for Exports and Tourism (PromPerú), an autonomous entity of MINCETUR. PromPerú's actions are aligned with the National Strategic Export Plan (PENX 2025) and the National Competitiveness and Productivity Plan 2019-2030, both developed with the broad participation of public and private actors.

PromPerú offers various support programmes for exporting SMEs through tools on its website, such as market intelligence, specialised advice, training, and trade events. It is worth highlighting the "Export Route" programme, designed to strengthen export capacities, with active participation in 2022, benefiting 7,107 SMEs.

In addition, Peru has Special Economic Zones (SEZs) that offer incentives for the installation of national companies, facilitating industrial, logistics and service activities. In terms of financing, the country has a diverse ecosystem that includes traditional financing, government funds through the Development Finance Corporation (COFIDE), and programmes such as the "Fondo Crecer", which benefited 7,107 SMEs in 2022. Also noteworthy is the Internationalisation Support Programme (PAI), which co-finances projects of Peruvian companies to strengthen their internationalisation process.

In the Trade facilitation sub-dimension, Peru obtained an outstanding score of 4.72. The country offers a wide range of documentation and guides aimed at facilitating the export process for entrepreneurs, including specific information according to the destination of the goods or services, as well as a financial guide for exporters, which clarifies the financial instruments associated with international trade. In addition, Peru has tools and programmes designed to simplify trade, such as PeruExpert, an advanced platform for the internationalisation of Peruvian companies that facilitates the commercial connection between the supply of services and specialised niches in the target market.

MINCETUR administers the Foreign Trade Single Windows (VUCE), which facilitate trade operations. As of the first half of 2023, 227,623 operations had been carried out in the Restricted Goods component of the VUCE, approximately 48% of the annual target. In addition, the National Superintendence of Customs and Tax Administration (SUNAT) offers certification as an Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) to companies, with 376 companies registered to date. There is a solid regulatory framework governing AEOs. In the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators (TIF), Peru outperforms the Latin American average in all categories, with an overall index of 1,568. This reflects the country's efforts to improve the availability of information, simplify tariffs and charges, and streamline documents and procedures related to international trade.

On the other hand, in the e-commerce sub-dimension, Peru obtained a score of 3.57. Although there is extensive regulation on e-commerce, it is scattered in several laws, such as the Law on the Protection of Personal Data and its Regulations, the Law on Digital Signatures and Certificates, and the Code of Consumer Protection and Defence. INDECOPI is the government agency in charge of protecting consumer rights and competition.

PromPerú implements the e-commerce programme, training and advising SMEs to reduce their digital gap and compete in the global market. It offers benefits such as distribution centres for e-commerce through Peru's Commercial Offices abroad and preferential rates for courier shipments. In addition, PRODUCE and PromPerú have made efforts to promote e-commerce, participating in international fora such as the Asia-Pacific Cooperation Forum. However, these initiatives lack the backing of a national strategic plan with measurable objectives and indicators.

In the quality standards sub-dimension, Peru obtained a score of 4.10. Quality is a fundamental aspect in various export promotion and internationalisation programmes, such as the PNCP 2019-2030 and the PENX-2025, which seek to develop an exportable supply of quality goods and services. The National Quality Institute (INACAL) plays a crucial role in granting certifications, training, and guiding entrepreneurs to comply with standards, including technical norms, quality management, and metrology.

The Innóvate Peru programme, restructured as the National Programme for Technological Development and Innovation (Proinnovate) in 2021, drives technological innovation, development, and entrepreneurship to generate new products, services, and sustainable processes. In 2023, Proinnovate financed more than a thousand innovation projects with a budget of more than USD 40 million, including financing projects to improve productivity and access new markets by obtaining management, process, or product system certifications. Although PromPerú does not offer specific training programmes to improve quality standards, it integrates them transversally in other training programmes such as RutaExportadora. It also participates in, and organises, national and international fairs where the improvement of quality standards is promoted.

Finally, in terms of the benefits of regional integration efforts, Peru achieved a score of 3.58. As a member of the Pacific Alliance (PA), Peru actively participates in the PA SME Technical Group. In the framework of the II Meeting of the PA SME Exporters, a Public-Private Dialogue was held to develop a Public-Private Roadmap, with the objective of promoting the growth, development, and competitiveness of SMEs in the economies of the member countries of the Pacific Alliance.

For its part, in the Andean Community, in 2021, the creation of the Andean Observatory for the Business Transformation of MSMEs was approved, with the aim of socialising business strengthening policies, taking advantage of the Andean market, encouraging the use of information and communication technologies, and monitoring economic performance indicators. In addition, in the same year, CAMIPYME coordinated the preparation of the Study for the Diagnosis of Regional Value Chains in the Andean Community with the collaboration of the IADB/INTAL, to select and prioritise the chains with potential to strengthen their productive integration.

The way forward

Enhance and consolidate e-commerce support programmes and data collection, through a comprehensive, inter-ministerial digital transformation strategy with a dedicated system to facilitate monitoring and evaluation.

Conduct an impact assessment of the various existing support mechanisms for SMEs, with an emphasis on those related to quality certificates, to better inform the design of new policies; as well as to understand the mix of programmes to which a given SME has access.

Improve information and programmes around Authorised Economic Operators, providing specific benefits to those SMEs that obtain this certification.

Strengthen sub-regional integration and SME empowerment through standardised and collaborative trade promotion and internationalisation programmes. The importance of standardising programmes among Pacific Alliance export promotion agencies is highlighted, ensuring coherence, and facilitating SME participation.

Dimension 8. Digitalisation

Peru boasts a Digitalisation dimension score of 4.11, underpinned by an above-average score of 4.60 for its National Digitalisation Strategy. The country's National Digital Strategy is an integral component of the National Digital Transformation System and is governed by the Digital Government Law. However, the Digital Government Plan 2023-2025 (Peruvian Digital Agenda), aimed at enhancing ICT adoption to boost SME competitiveness, lacks an independent strategy. The coordination of the National Digital Transformation System involves key stakeholders, with the Secretariat of Government and Digital Transformation of the Council of Ministers at the helm, ensuring collaboration with state entities and other actors. Each entity has designated roles, and monitoring occurs through institutional management documents and, at a macro level, via the digital indicators’ platform.

In the Broadband Connectivity sub-dimension, Peru receives a less robust score of 3.44. This is attributed to Law 29904, the Promotion of Broadband and Construction of the National Fiber Optic Backbone Law (2012-2032). The Peruvian Digital Agenda outlines two key actions: firstly, driving widespread broadband adoption through a fibre optic backbone network, and secondly, promoting business connectivity, particularly for SMEs, by facilitating access to high-speed internet.

The availability of various digital skills support initiatives for SMEs contributes to Peru's above-average score of 4.27 in the Digital Skills sub-dimension. The National Digital Talent Strategy (2021-2026) and the National Digital Talent Platform address prioritised challenges, including the training of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises across all productive sectors to ensure they possess the essential digital skills for their digital transformation processes. Within this framework, the National Programme Tu Empresa forges strategic alliances to cultivate and enhance the digital skills of entrepreneurs and micro-entrepreneurs.

The way forward

Going forward, Peru could consider:

Promote inclusive broadband access for SMEs, ensuring that they benefit from the ongoing efforts to drive widespread broadband adoption.

Facilitate public-private partnerships to enhance digital infrastructure, fostering collaboration for the benefit of SMEs and promoting data transparency with standardised indicators for more accurate assessments of progress.

Develop and integrate a dedicated SME Digitalisation Strategy within the existing National Digital Transformation System.

References

[3] BCRP (2023), Reporte de Inflación. Panorama actual y proyecciones macroeconómicas 2023-2025, Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/docs/Publicaciones/Reporte-Inflacion/2023/diciembre/reporte-de-inflacion-diciembre-2023.pdf.

[2] BCRP (2022), Memoria, Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/publicaciones/memoria-anual.html.

[5] INEI (2023), Demografía Empresarial del Perú, Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, https://m.inei.gob.pe/biblioteca-virtual/boletines/demografia-empresarial-8237/1/#lista.

[4] INEI (2023), Situación del mercado laboral en Lima Metropolitana, INEI.

[6] MINCETUR (n.d.), Acuerdos Comerciales del Perú, https://www.acuerdoscomerciales.gob.pe/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

[1] OECD (2024), Real GDP forecast (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/1f84150b-en (accessed on 13 March 2024).