This chapter provides an assessment of Ecuador. It begins with an overview of Ecuador’s context and subsequently analyses Ecuador’s progress across eight measurable dimensions. The chapter concludes with targeted policy recommendations.

SME Policy Index: Latin America and the Caribbean 2024

20. Ecuador

Abstract

Overview

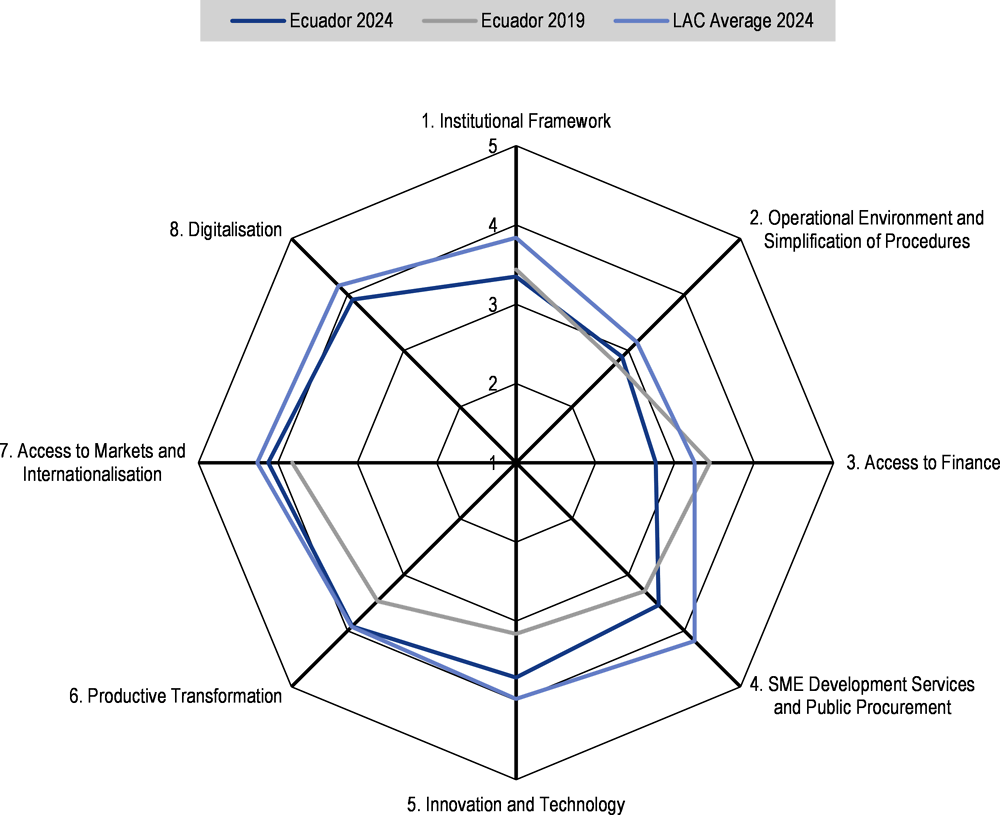

Figure 20.1. 2024 SME PI Ecuador's score

Note: LAC average 2024 refers to the simple average of the 9 countries studied in this 2024 report. There is no data for the Digitalisation dimension in 2019 as the 2019 report did not include this dimension.

Ecuador continues to make significant efforts in developing policies aimed at SMEs, as evidenced by the improved scores in several of the eight evaluated dimensions compared to its 2019 performance (see Figure 20.1): Operational Environment and Simplification of Procedures (Dimension 2), SMEs Development Services and Public Procurement (Dimension 4), Innovation and Technology (Dimension 5), Productive Transformation (Dimension 6), and Access to Market and Internationalisation (Dimension 7). However, the previous policy focus on entrepreneurship and micro-enterprises has faced disruption due to macroeconomic challenges and political instability, impacting primarily its Institutional Framework (Dimension 1) and Access to Finance (Dimension 3).

Developing a new SME development strategy with realistic, quantifiable, and time-bound objectives, and setting targets for reducing enterprise informality, while carefully choosing policy tools that take into account budget and operational constraints, could provide the country with the necessary tools to further strengthen SME development policies.

As noted in the previous assessment, the current lack of a comprehensive SME development strategy hinders the optimisation of synergies and spillover effects among existing actions. Moreover, operational complexities, particularly in starting a business, pose significant hurdles with lengthy and relatively costly procedures. Nonetheless, there is optimism driven by the government's commitment to legal simplification and regulatory reforms. The prioritisation of the simplification of procedures and the competitiveness agenda culminated in the introduction of the Ecuador Competitiveness Strategy in 2022, representing an ambitious action plan encompassing three key areas: Ecuador Productivo, Ecuador Global, and Ecuador Innova.

Going forward, Ecuador could benefit from increasing direct financial support for SME innovation, including performance-oriented key performance indicators (KPIs) to monitor existing policies, and using online platforms to provide comprehensive explanatory information for current programmes. This would facilitate access for relevant stakeholders, including the SME population.

Context

In 2020, Ecuador faced severe economic repercussions from the COVID-19 pandemic, experiencing a contraction of 7.8%. This decline was attributed to various factors, including reductions in gross fixed capital formation, household and government consumption, and a slowdown in exports (BCE, 2021[1]). To mitigate the impact, measures were implemented to alleviate financial and tax obligations, support employment, and enhance access to credit (Heredia and Dini, 2021[2]).

By 2021, the economy rebounded with a 4.2% growth, driven by global recovery, successful vaccination efforts, and improved employment indicators. Despite this recovery, GDP did not reach pre-pandemic levels (BCE, 2022[3]). In 2022, facing international challenges and disruptions, Ecuador's economic growth slowed to 2.9%, influenced by health measures and the vaccination rollout (BCE, 2023[4]). In the last quarter of 2023, the Ecuadorian economy contracted by 1.3% compared to the previous quarter (BCE, 2023[5]).

In 2022, the global economy faced an inflationary crisis as a consequence of the significant rise in international and energy prices, intensified by Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine. This was compounded by the progressive global economic recovery, led by household consumption and fiscal stimulus. In Ecuador, the expansion of demand and the paralysis during June, which caused disruptions in local supply chains and generated an immediate rise in food prices, pushed inflation to 3.5% at the end of the year; it should be noted that, among the economies of the region, Ecuador's inflation was among the lowest, second only to Bolivia's (BCE, 2023[4]).

Regarding the labour market, Ecuador's employment indicators showcase a distinctive aspect among Latin American countries, as the deterioration is reflected more in the quality of employment than in the unemployment rate. In 2021, only 33.7% of the economically active population (EAP) had adequate employment1, a figure higher than in 2020 (29.1%) but still below pre-pandemic levels (around 40%). Consequently, the quality of employment in Ecuador declined, with under-employment reaching 23.5% (BCE, 2022[3]), while informality stood at 50.6%. In 2022, the overall participation rate reached 65.7%, the employment rate increased to 96.2%, under-employment decreased to 20.8%, and informality reached 53.4%. Unemployment decreased to 3.8% in the fourth quarter of 2022 (BCE, 2023[4]). In 2023, the unemployment rate remained relatively stable at 3.8%, with an informality rate of 54.4%, under-employment at 20.0%, and the overall participation rate closing the year at 65.6%.

Furthermore, Ecuador has made progress in international trade integration, particularly with Latin American and European countries. The country has 11 trade agreements with these regions, with its primary export destinations being the United States, China, and Panama (Ministry of Production Ecuador, n.d.[6]). Major exports include crude oil, bananas, and aquaculture products. Despite these advancements, there are considerable areas for improvement in regulatory simplification and ease of tax filing. Ecuador has also seen progress in e-government, facilitated by electronic signatures and the digitalisation of various government services. In terms of access to credit, Ecuador performs similarly to other countries in the region but exhibits shortcomings in mechanisms for dealing with business insolvency (OECD, 2019[7]).

Finally, according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos of Ecuador (National Institute of Statistics and Census of Ecuador, INEC), by 2022, a total of 863,681 companies were registered in Ecuador. This included 810,691 micro companies (93.86%), 38,291 small companies (4.43%), 6,065 medium-sized companies "A" (0.70%), 4,197 medium-sized companies "B" (0.49%), and 4,437 large companies (0.51%). These businesses operated in various economic sectors: 44.78% in Services, 34.50% in Commerce, 9.24% in Agriculture, 8.15% in Manufacturing, 3.14% in Construction, and 0.19% in Mining. SMEs accounted for 99.54% of the business landscape and represented 56.18% of national employment (INEC, 2022[8]).

Dimension 1. Institutional Framework

Ecuador scores a total of 3.35 in the first dimension, reflecting its relatively well-established institutional framework for SME policy. The country has adopted an operational SME definition and defined institutions for policy elaboration, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. The previous policy focus on entrepreneurship and micro-enterprises has faced disruption due to macroeconomic challenges and political instability. The large informal sector remains a significant challenge, affecting the effectiveness of SME policy, reflected in sub-dimension scores of 4.33 for SME Definition, 3.09 for Strategic Planning, Policy Design and Coordination, 3.52 for Public-Private Consultations, and 2.71 for Measures to Tackle Informal Economy.

The SME definition is set by the Código Órganico de la Producción, Comercio e Inversiones (Production, Trade and Investment Code) based on employment and annual turnover parameters, categorising enterprises into micro, small, and medium-sized. To benefit from public support and a favorable tax regime, SMEs must register with the Registro Único de MIPyMES (Single Registry of MSMEs, RUM). The Ministry of Production, External Trade, Investment, and Fishery, specifically the Sub-secretariat of SMEs and Crafts is responsible for SME policy elaboration and implementation.

Legislative acts such as Código Órganico de la Producción, Comercio e Inversiones, Ley Orgánica de Emprendimiento e Innovación (Organic Law on Entrepreneurship and Innovation), and Código Orgánico de la Economía Social de los Conocimientos, Creatividad e Innovación (Organic Code of the Social Economy of Knowledge, Creativity, and Innovation) shape the SME policy framework. Strategic guidelines are found in planning documents like the Plan de Desarollo 2030 (Development Plan 2030), Industrial Policy for Ecuador 2016-2025, and the completed Plan Toda la Vida (2017-2021).

Until the presidential elections of May 2023 Ecuador have pursued a policy trying to match industrial policy objectives with measures to promote a more equitable and socially oriented economic system, with a focus on local development, entrepreneurship promotion and micro-enterprises. However, due to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, a worsening of the macro-economic conditions, increased political instability and a deterioration of the internal security situation, policy implementation has been disrupted.

The new government, installed after the May 2023 presidential elections, has initiated consultations for the development of new strategic guidelines for SME development. However, no comprehensive strategic plan is currently in place. The Ministry of Production has been adopting ad-hoc measures in response to economic conditions through executive decrees.

Ecuador has developed a specific methodology for monitoring publicly funded programmes, known as Gobierno por Resultados (Government by Results). The application of this methodology is coordinated by the National Secretary of Planning and Development. In the specific case of each Ministry, monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are managed in accordance with the current technical regulations.

Furthermore, the Law on Efficiency and optimisation of procedures requires institutions engaged in norm preparation to publish text consultation with the population for at least a week. The Consejo Nacional de Competitividad, Emprendimiento y Innovación, established in 2022, introduces a new public-private consultation table with private sector representatives and relevant ministries for SME policy.

On another note, Ecuador grapples with a substantial informal sector, ranking among the largest in Latin America. Informal employment is estimated to exceed 52% of total employment, according to a labour survey conducted by the national statistical office in 2022. This informality is notably concentrated among self-entrepreneurs and micro-enterprises.

Currently, there is no specific strategy in place to address labour and enterprise informality. However, the Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca (Ministry of Production, Foreign Trade, Investment and Fisheries, MPCEIP) has introduced incentives to facilitate registration in various regulatory bodies, including the Registro Único de Contribuyente (Registro Único de Contribuyente, RUC), the Registro Único Artesanal (Single Register of Crafts, RUA), the RUM, and the Registro Nacional de Emprendedores (National Register of Entrepreneurs, RNE).

The way forward

Develop a new SME development strategy with realistic, quantifiable, and time-bound objectives. Set targets for reducing enterprise informality and carefully choose policy tools, taking into account budget and operational constraints.

Engage the newly established Consejo Nacional de Competitividad, Emprendimiento e Innovación in the strategy elaboration. Strive to forge a pro-development pact with the private sector, mitigating the negative impact of criminal and informal sector activities. Identify short and medium-term measures to support legal and productive activities.

Elaborate a comprehensive strategy to reduce labour and enterprise informality through a broad public debate involving private sector representatives, local authorities, labour and SME development experts, and international organisations. Given the absence of pre-defined solutions for dealing with d informality, embrace experimentation to identify effective policy actions. Organise calls for proposals to select and test projects aimed at reducing informality at the local level, monitor their implementation, and learn valuable lessons on effectively addressing diffuse informality.

Dimension 2. Operational environment and simplification of procedures

SMEs in Ecuador face a challenging operational environment. While operational complexities, especially in starting a business, pose hurdles with lengthy and relatively costly procedures, there is optimism fuelled by the government's commitment to legal simplification and regulatory reforms. Despite the limited progress due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and broader macro-economic challenges, the ongoing initiatives signal an area of opportunity for improvement and enhanced business facilitation.

Ecuador's overall score in this dimension is 2.89, with specific scores of 3.12 for Legislative Simplification and Regulatory Impact Analysis, 2.70 for Company Registration, 2.40 for Ease of Filing Tax, and 3.40 for E-government, reflecting advancements made during the 2019 assessment.

In 2018, Ecuador initiated regulatory simplification through the approval of Executive Decree 372, directing the Ministry of Telecommunications to establish an electronic platform cataloguing all administrative regulations. Concurrently, the Inter-institutional Committee for Regulatory Simplification was formed. The Law on Efficiency and optimisation of procedures ratified in the same year, mandates public institutions to institute programmes for regulatory simplification when regulations affect private enterprises. Despite these efforts, the regulatory reform lacks a systematic approach, and there is currently no comprehensive plan for legislative simplification. The Organic Law for Entrepreneurship supports a similar approach. Although ad-hoc interventions are in place, the establishment of an Interinstitutional Committee for Regulatory Simplifications, associated with the E-Government programme, is a positive step. The application of Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) is still in its early stages.

Furthermore, the procedures of starting a business in Ecuador are complex. For incorporated companies, standard procedures involve registration in three different registries: the Register managed by the Superintendence of Companies, the Register at the Mercantile Registry Office (company’s charter and resolutions, name of the company’s legal representatives) and the RUC requiring legal and notary services. While online registration is available, there is no One-Stop-Shop, and procedures must be completed sequentially. Nevertheless, Ecuador's new Organic Law on Entrepreneurship and Innovation, passed in 2020, established the Simplified Joint Stock Company. This type of company facilitates simpler and more economical management, making it easier to start or grow a business.

Ecuador's corporate tax regime is costly, with a heavy administrative burden. The country ranks 147/190 in the Paying Taxes dimension of the Doing Business 2020, with a performance index of 58.6/100. While the number of yearly tax payments is better than the regional average, the time required for these payments is exceptionally long (664 hours per year), more than double the average time for the region. Corporate taxes and social contributions amount to 34.4% of total profits. A simplified tax regime Régimen Simplificado para Emprendedores y Negocios Populares (Simplified Regime for Entrepreneurs and Popular Businesses, RIMPE) is in place for enterprises with an annual turnover between USD 20,000 and 300,000, aiming to combat informality.

Furthermore, Ecuador launched its first National E-Government Plan in 2018, covering the period 2018-2021, and is implementing its Política Ecuador Digital. The policy aims to promote digital transformation across enterprises, citizens, and public administration, addressing the digital gap and enhancing public administration efficiency. The Política Ecuador Digital is supported by a legal and regulatory framework, including the Organic Law on Telecommunications, The Organic Law for the Optimisation and Efficiency of Administrative Procedures, the General Law on Civil Registration, Identification and Identification Cards, the Organic Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information, and Law 067 on Electronic Commerce.

The way forward

Ecuador could consider resuming the 2018 legislative simplification and regulatory reform. It should strengthen the role of the Inter-institutional Committee for Regulatory Simplifications and elaborate a medium-term plan, identifying the reforms that may be achieved in a relatively short term, have contained implementation costs, but are expected to have a significant impact on the improvement of the business environment, while contributing to rebuilding the private sector’s confidence in governmental action.

Steps should be taken towards the application of RIA on the most relevant new legislative and administrative acts. In order to proceed in this direction, the government should give a mandate to a public institution to form a team of RIA specialists and to act as a supervisor of RIA applications.

Simplify company registration procedures by establishing a network of OSS, combining national and local registration procedures, and developing online registration, with an initial focus on individual entrepreneurs and micro-enterprises.

Simplify tax declaration and payment procedures. Additionally, it should calculate the effective tax rate imposed on SMEs following the introduction of the RIMPE and examine potential distorting effects on enterprise growth.

Dimension 3. Access to finance

Ecuador obtains an overall score of 2.76 in the Access to Finance dimension. It also achieved a score of 2.94 in the Legal, Regulatory and Institutional Framework sub-dimension, standing out mainly for a good score in the weighting of guarantees for SMEs and progress in the development of securities market regulation. In access to finance, there is a legal framework for the regulation of the capital market for SMEs, including a separate market for these small-cap companies. However, there is a lack of strategies to help SMEs comply with listing requirements.

On the other hand, regulation on the percentage of collateral required for medium-term loans to SMEs is low. However, the overall score is negatively affected by the under-developed regulation and institutionalisation of the registration of tangible and intangible assets. Despite the existence of a cadastre, it is neither fully functional nor accessible to the public online, and the absence of a registry of security rights over movable assets.

In terms of the availability of diversified sources of Enterprise Finance, Ecuador scores 4.33, slightly above the average (4.32). It stands out positively for the presence of numerous microfinance institutions with national coverage. In addition, the country offers export financing schemes and credit guarantee tools for SMEs that lack assets to meet the collateral demands of commercial banks.

Despite these advances, Ecuador does not have private sector participation in the management of public credit guarantee schemes, nor are there any mutual or private credit guarantee schemes in the country. In addition to these schemes, Ecuador has other asset-based financial tools, such as factoring, which are adequately regulated. It has also sought to promote other capital instruments, such as crowdfunding, regulated through the Organic Law on Entrepreneurship and Innovation of 2020. However, the effectiveness of these tools remains low due to the early stages of their development.

In the Financial Education sub-dimension, Ecuador scores 2.40. The country has a Estrategia Nacional de Educación Financiera (National Financial Education Strategy, NFES), aligned with the Política Nacional de Inclusión Financiera (National Financial Inclusion Policy, PNIF), published in September 2023. The ENEF's vision is to enhance the economic development and well-being of individuals and SMEs through the sustainable provision of quality financial products and financial user empowerment. In this strategy, SMEs are considered as a priority segment. In addition, Ecuador has carried out financial capability surveys using the OECD methodology, although these are mainly targeted at individuals and are conducted in collaboration with local supervisory institutions, such as the Superintendency of Banks and the Central Bank, with the support of CAF.

Ecuador's biggest challenges are in the sub-dimension of Effective procedures for handling bankruptcy or insolvency, where the country scores 1.35 points. Ecuador still has much potential for improvement in the design and performance of procedures for handling insolvency and bankruptcy situations, as well as for facilitating the productive reinsertion of entrepreneurs whose previous ventures were unsuccessful.

Although Ecuador has a regulatory framework and some procedures for insolvent companies, these lack many of the elements necessary to achieve the objectives of protecting and developing the skills of entrepreneurs, as well as protecting creditors and the state. Despite these shortcomings, the presence of early warning systems to detect companies at risk of bankruptcy was identified. In addition, the existence of regulations for secured transactions was validated, including provisions that prioritise secured creditors in the liquidation processes of bankrupt companies, as well as the priority of tax debts over other debts in such processes. Furthermore, in July 2023, the President of the Republic of Ecuador issued the decree of the Organic Law on Corporate Restructuring. This law aims to protect credit, preserve viable companies and sources of employment, as well as to liquidate unviable companies in an orderly manner.

The way forward

Establish a strategy to support SMEs comply with stock market listing requirements.

Strengthen the cadastre to make it functional, publicly accessible and online. Additionally, create the registry of security rights over movable assets, documenting ownership of registered pledges, and make it publicly accessible online.

Promote the development of credit guarantee systems, while encouraging private sector participation in its management of public credit guarantee systems.

Conduct regular financial capability surveys for SMEs in order to have updated information for the design of financial education programmes, as well as design and implement a follow-up, monitoring and evaluation system.

Strengthen the existing regulatory framework related to bankruptcy and insolvency policies and develop specialised information and training mechanisms for entrepreneurs in search of a new opportunity.

Promote other out-of-court mechanisms for bankruptcy cases that can be more cost and time efficient for the parties.

Create an official bankruptcy and insolvency register, which should be open to the public with the possibility of removing companies and individuals from such registers when the situation is resolved, in line with international best practices.

Dimension 4. SME development services and public procurement

Ecuador’s scores in this area show that there is important room for improvement. The overall result for the dimension is 3.54, below the regional average and behind the majority of countries assessed. The results for public procurement are the most solid, at 4.20 (an improvement from the past assessment); yet entrepreneurship development services lag well behind, at 3.00, followed by business development services at 3.61. Despite these challenges, there is an overall improvement compared to the 2019 SME PI, reflecting the positive direction the country is heading in this regard.

As noted in Dimension 1, Ecuador has a relatively established institutional and strategic framework for SME policy, under the responsibility of the MPCEIP for policy design, and implementation through the Sub-Secretariat of SMEs and Crafts. The strategic guidance for SME policy and therefore for the provision of BDS and services for entrepreneurs is somehow fragmented, with strategic guidelines in the National Development Plan 2030, and the Industrial Policy 2016-2025, as well as the new orientations yet to be provided by the new administration.

The Sub-secretariat of SMEs and Crafts is responsible for the development, strengthening, and training of SMEs, artisanal production branches, and entrepreneurship. Among its responsibilities are the planning and development of programmes and projects to support SMEs, artisanal production branches, and entrepreneurship, establishing the application of business tools for competitiveness development, such as associativity processes, excellence management, value chains, and economic agglomerations. To carry out these responsibilities, the Sub-secretariat offers a portfolio of services that includes technical assistance, counselling, and entrepreneurship development. These services are available to SMEs from the idea phase to the inclusion of their products in the market. Specific services include business planning, marketing and sales, financial management, product development and innovation and access to markets and financing assistance.

According to the responses of the authorities and independent evaluators to the questionnaires for this assessment, the design of BDS is not based on thorough diagnostic studies of the needs of SMEs and their objectives are not explicitly linked to the national strategies mentioned above. Hence, the supply of BDS is rather disperse and, according to the conversations of the independent evaluators with small business associations, the perception is that the offer of BDS is not enough and there is a lack of information on them. In addition, there seem to be no programmes for the specific support of high growth and high potential enterprises, and there is no solid information regarding the support to business incubators, accelerators or other services aimed at entrepreneurs and start-ups.

In terms of the resources available, 62% of the budget for the provision of BDS comes from government sources, 35% from international development banks, and the rest from other organisations. According to the evaluation, the resources available are not enough to cover the needs of the SME population.

The public procurement regime in Ecuador is provided by the Ley Orgánica del Sistema Nacional de Contratación Pública, (Organic Law of the National System of Public Procurement, LOSNCP). As noted in the 2019 edition of the SME PI, the LOSNCP includes the intention to facilitate the participation of SMEs in public procurement, although no details on how to achieve this are explained in the law. According to the responses to the questionnaire for this assessment, the procurement regime includes the possibility, but not an obligation, to break tenders above a certain size in lots, the possibility for SMEs to form consortia for joint bidding, and preference margins and set aside for SMEs in public procurement. Furthermore, article 101 of the LOSNCP establishes penalties and dismissal for government officials in charge of procurement payments who “unduly withhold or delay payments,” however, it does not specify payment deadlines or sanctions to institutions. According to the independent evaluation, SME business associations representatives state that in practice, the participation of SMEs in public procurement is not facilitated since, for example, technical specifications are difficult to meet and administrative burdens are put in place.

The Servicio Nacional de Contratación Pública (National Service for Public Contracting, SERCOP) is the authority in charge of public procurement and manages the electronic procurement portal, which can handle all steps in the procurement process. In addition, Ecuador has a Registro Único de Proveedores (Unified Registry of Suppliers, RUP), which serves to facilitate the future participation of suppliers in procurement processes.

The way forward

As in the 2019 assessment, Ecuador has ample scope for improving in this dimension, by:

Preparing thorough diagnostics about the different needs of SMEs and entrepreneurs, so that policies and programmes can better respond to their priorities.

Addressing the fragmentation of the provision of BDS for SMEs and support for entrepreneurs, including by linking the national development strategy to specific SME development policies and programmes.

Expanding the offer of BDS and entrepreneurial development services, including by establishing support for high growth and innovative SMEs and start-ups, as well as strengthening a national system of business incubators and accelerators.

Improving the measures to facilitate SME access to public procurement, including by specifying concrete actions currently absent in the LOSNCP and by further clarifying payment deadlines and introducing measures addressed to institutions, instead of relying on sanctions only to individuals.

Addressing the concerns of SME business associations regarding the difficulties and technical specifications (if needed) to facilitate access to public procurement.

Dimension 5. Innovation and technology

Ecuador has a score of 3.71 in the Innovation and Technology dimension, boosted by particularly high scores in the Institutional Framework and Support Services sub-dimensions. Innovation policy in Ecuador is overseen by the Consejo Nacional de Competitividad, Emprendimiento e Innovación (National Council for Entrepreneurship and Innovation, CONEIN), which was established under the 2020 Law on Entrepreneurship and Innovation. The Council is chaired by the President (or a delegate) and has representatives from key government ministries, as well as business associations and research institutions. This represents an effective mechanism for inter-ministerial collaboration and private sector engagement. The government has recently adopted a national innovation strategy, although its implementation has not yet begun. While the private sector was consulted during the design of the strategy, there would be scope to increase the level of consultation with SMEs specifically to ensure that the particular needs of this group are addressed in future innovation policies. Ecuador has a score of 3.96 in the Institutional Framework sub-dimension, reflecting the strong co-ordination and consultative mechanisms that are in place.

There are innovation centres and technology parks in Ecuador, such as the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL) Science and Technology Park, that connect SMEs with research institutions. Ecuador also has some incubators and accelerators, which are often private sector or university initiatives. Ecuador’s score for the Support Services sub-dimension (3.81) could be improved by strengthening monitoring and evaluation practices, for example by reliably evaluating the impacts of innovation support programmes on SME performance.

Ecuador performs slightly worse in the Financing for Innovation sub-dimension, with a score of 3.36. Financial support options for innovative SMEs are less extensive in Ecuador than in other LAC countries, and available grants for SMEs do not appear to place a strong emphasis on innovation. However, the Law on Entrepreneurship and Innovation does include provisions to strengthen innovative SMEs’ and entrepreneurs’ access to finance.

The way forward

In the future, Ecuador could consider:

Increasing direct financial supports for SME innovation, including through innovation vouchers or grants.

Strengthening public support for the incubator and accelerator system.

Dimension 6. Productive transformation

Ecuador's endeavors in productive transformation persist under the framework of the Industrial Policy 2016-2025, obtaining a score of 3.92 in this dimension. Introduced during the 2019 SME PI, this policy encounters challenges parallel to those faced by other strategies in LA9, primarily due to its lack of quantifiable objectives, making it difficult to instrument progress as its completion approaches. Despite their ongoing efforts, Ecuador is yet to make substantial progress towards attaining the overarching goals set for 2025. These goals encompass a 10-percentage-point increase in GDP, a reduction of the trade deficit by $10.2 million, the creation of 251,000 new jobs, and a $13.6 million increase in investment —highlighting the implementation problems the policy has faced. However, in 2021 with Executive Decree No. 68, the facilitation of trade and production, the simplification of procedures and the competitiveness agenda were declared as priority public policy, which culminated with the introduction of the Ecuador Competitiveness strategy in 2022 representing an ambitious action plan encompassing three key areas: Ecuador Productivo, Ecuador Global, and Ecuador Innova. Oversight of this strategy falls under the purview of the MPCEIP, in collaboration with an Inter-ministerial Commission dedicated to its effective implementation. For its elaboration, a participatory process was carried out through 60 workshops with companies and trade unions. Ecuador scores 4.39 in the Productivity-Enhancing Measures sub-dimension.

Measures to encourage and support productive associations in Ecuador took a positive turn with Executive Decree No.68, which also includes cluster initiatives reflected in the score of 3.72 for this sub-dimension. This initiative assigns the MPCEIP the responsibility to provide technical and financial assistance to SMEs wishing to form or join a cluster and implements a number of actions framed in three factors: (1) generation and promotion of productive clusters, (2) promotion of entrepreneurship and SMEs, and (3) promotion of a quality ecosystem in the local market. Although there is no information available on the development of the action plan for the implementation of the initiative, as of the date of the assessment, there are 20 initiatives underway in the sectors of logistics, agriculture, industry, technology, finance, and real estate development, with a budget of USD 340,000 for the first phase and USD 385,134.13 for the second phase of its implementation. Finally, as a continuation of the current Industrial Policy 2016-2025, the eight projects established in basic industries were implemented, but there is no monitoring or evaluation data available, reflecting the lack of monitoring on the implementation of the policy.

Similar to most Latin American countries assessed, Ecuador's score is, to some extent, affected by its performance in the sub-dimension of integration into global value chains, particularly in the monitoring and evaluation section, resulting in a score for the entire sub-dimension of 3.77. At the time of the first assessment, the ENCADENA programme, which included several components such as an industrial cadastre update, the establishment of an inter-ministerial information and support platform for Ecuadorian industry, diagnostic studies of priority value chains, and support to large companies for supplier development, had reached its conclusion and encountered issues in its deliverables and implementation. However, the competitiveness strategy under the key area of Ecuador Global aims to replace these efforts by providing technical assistance, though currently there is no additional data on key actions to enable this. Conversely, ongoing initiatives such as the Supplier Development programme with UNDP, continue to work with large companies and their suppliers in value chains.

The way forward

Although Ecuador has initiated a new strategy to enhance productivity, the lack of consolidated and accessible information poses a challenge for effective engagement. To address this, Ecuador could:

Enhance the transparency of ongoing implementation efforts by increasing the availability of information to external stakeholders, including SMEs.

Develop a website specifically designed to offer more comprehensive details on the key actions and initiatives embedded in the strategy and to track and communicate the progress of the strategy. Drawing inspiration from successful examples in other LA9 countries, such as Mexico and Chile, can provide valuable insights into designing an effective platform.

Dimension 7. Access to market and internationalisation of SMEs

Ecuador obtained a score of 4.12 in the market access and internationalisation dimension. Its good performance in the sub-dimensions related to Support Programmes for Internationalisation, as well as Trade Facilitation, stands out.

In terms of the sub-dimension of Support Programmes for Internationalisation, Ecuador achieved a score of 4.46. The internationalisation and export promotion policy are developed and implemented by the MPCEIP, through the Coordination of Export and Investment Promotion Abroad (VPEI). The overall strategy is defined by the Plan for the Creation of Opportunities 2021-2025 and, more recently, by the Development Plan for the New Ecuador 2024-2025. Both plans include objectives and strategies aimed at increasing productivity and creating better conditions for foreign trade, with the purpose of improving the country's participation in international trade. Thus, for example, the Development Plan for the New Ecuador establishes as a policy to "Increase trade openness with strategic partners and with countries that constitute potential markets", which in turn is accompanied by a strategy with measurable objectives and goals. In this context, the VPEI has the ProEcuador agency, which is responsible for implementing the country's export and investment promotion policies and regulations to promote Ecuador's products and markets.

The MPCEIP promotes the country's commercial insertion in the international market, supported by national and international organisations. Within this framework and in collaboration with the European Union, the MPCEIP is carrying out the training programme "Internationalisation of Ecuadorian companies, technical obstacles and access barriers for their exports to the European Union market". The programme, distributed in 11 workshops until 29 November, is aimed at companies registered in the ProEcuador route for exports, with the objective of increasing productivity and quality-related services, as well as increasing the degree of commercial openness, promotion, and non-oil productive-export diversification.

Ecuador scored 4.65 in the Trade Facilitation sub-dimension. In this regard, the Ecuadorian Single Window (VUE) is an electronic tool through which all foreign trade operators submit the requirements, procedures and documents needed to carry out foreign trade operations. Approximately 200 applications are received daily, and although the law currently stipulates a processing time of 5 days, thanks to the improvements implemented, applications are processed in an average of 2.13 days. To promote the use of this tool, ProEcuador has carried out introductory training on foreign trade at the national level, including a training module in “Exporta Fácil” since 2011, as well as linking its users to trade promotion events abroad and export training projects and adaptation of the exportable supply.

The main objective of Exporta Fácil is to facilitate and promote the export of small and medium-scale Ecuadorian products to other countries. To achieve this, it simplifies customs and logistics procedures, reduces costs, and offers a more efficient shipping process for exporters. This programme is the result of collaboration between the MPCEIP, ProEcuador, the public postal company Correos del Ecuador and SENAE, with the aim of providing a practical and specialised service. Another outstanding programme is "Exporta País", developed by the MPCEIP and ProEcuador, which focuses on generating new exporters and strengthening existing ones by diversifying markets.

In addition, the National Customs Service offers certification as an Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) and promotes its use; however, SME participation needs to be enhanced. Ecuador also provides companies with a detailed guide with the steps to export. However, according to the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicator (TFI), Ecuador is below average in all variables considered, with the largest growth gaps in documents (LAC: 1,591; ECU: 1,111) and availability of information (LAC: 1,467; ECU: 1,200).

In the e-commerce sub-dimension, Ecuador scored 3.90. Although the country has a solid legal framework for e-commerce, there are still opportunities to improve the training, adoption, and promotion of e-commerce in the country. Ecuador's e-commerce legislation is based on the Law on Electronic Commerce, Electronic Signatures and Data Messages, the Production, Commerce and Investment Code, and the Organic Law on Communication. These laws regulate various areas related to electronic transactions, online consumer protection and digital communication.

The MPCEIP, together with the Ministry of Telecommunications and the Information Society, the private sector and academia, have developed the Estrategia Nacional de Comercio Electrónico (National Electronic Commerce Strategy, ENCE) to encourage the use of e-commerce through information and communication technologies. This approach seeks to support innovation, productivity, and competitiveness. Promotion and training programmes, mainly aimed at SMEs, are implemented by these ministries.

For the quality standards sub-dimension, Ecuador obtained a score of 3.57. The country has the Organic Law of the Ecuadorian Quality System, which establishes a comprehensive framework for quality assurance in Ecuador. The Servicio Ecuatoriano de Normalización (Ecuadorian Standardisation Service, INEN) is the institution responsible for metrology, standardisation, accreditation, and conformity assessment in the country. INEN offers an extensive training programme in standardisation, regulation, metrology, validation, and certification, accessible to all citizens free of charge. In addition, INEN carries out an annual "Metrologist Training Programme", which is highly valued by both the public and private sectors. The National Standardisation Strategy 2023-2025 reflects international support and cooperation, establishing strategic objectives to promote a culture of quality in the country, aligned with global trends and committed to stakeholders. This strategy links with several national frameworks and policies, including the National Plan for the Creation of Opportunities 2021-2025, the Industrial Policy of Ecuador 2016-2025, and the Ecuador Competitiveness Strategy.

Finally, in the sub-dimension on the benefits of regional integration, Ecuador obtained a score of 3.47. In order to boost the business landscape of SMEs in the Andean Community, the creation of the Andean Observatory for the Business Transformation of MSMEs has been approved. This initiative, accompanied by a diagnostic study of regional value chains, seeks to strengthen productive integration in the region. In addition, the Andean Community is working on strengthening value chains in member countries through studies carried out by CAMIPYME with the support of the IADB/INTAL.

The way forward

Strengthen and expand public sector support for quality certifications for Ecuadorian SMEs, capitalising on existing efforts and programmes.

Consolidate the future of Andean SMEs: capitalising on CAMIPYME's research and establishing a solid and measurable development strategy. This will strengthen sub-regional integration that will result in specific benefits for SMEs.

Strengthen and promote e-commerce as a strategic tool for the internationalisation of Ecuadorian SMEs, highlighting the positive impact that e-commerce can have on Ecuadorian exports, such as expansion to new markets, cost reduction and improved competitiveness.

Improve the monitoring and evaluation of the different SME support programmes, as well as the channels of communication with the private sector, in order to facilitate the continuous improvement and adaptation of the programmes.

Dimension 8. Digitalisation

Ecuador achieves a score of 3.91 in the Digitalisation dimension, propelled by commendable performance in the National Digital Strategy and Digital Skills sub-dimensions. The nation is actively embracing digital advancement through the National Digital Transformation Agenda, spearheaded by the Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Society. This agenda champions digitalisation to enhance competitiveness and innovation across various societal domains. At its core is the Digital Transformation Agenda 2022-2025, delineating Ecuador's digital objectives. It underscores the development of digital skills and a digital culture while integrating emerging technologies. Collaboration between ministries, such as Education and Health, ensures a cohesive approach to Ecuador's digital transformation, reflected in a robust score of 4.33 in the National Digitalisation Strategy sub-dimension, highlighting effective coordination and consultative mechanisms.

Ecuador aspires to ensure universal internet access, with a specific focus on underserved regions and SMEs through its Digital Transformation Agenda. While lacking a dedicated law, the agenda strongly advocates for widespread broadband access. The pivotal role of public-private partnerships and international collaborations is underscored in enhancing connectivity infrastructure and delivering high-speed internet services. This comprehensive initiative guarantees inclusivity and accessibility nationwide, enabling seamless participation in the digital ecosystem for all citizens and businesses, irrespective of location or size. Improving Ecuador’s score in the Broadband Connectivity sub-dimension, currently at 3.17, below the regional average, could significantly enhance the overall digitalisation score, recognising access to infrastructure as a prerequisite for SME digitalisation.

Ecuador excels in the Digital Skills sub-dimension, securing a score of 4.23. The nation's approach to cultivating digital skills is a multifaceted initiative spanning various educational tiers and societal segments. At its core is the Digital Education Agenda intricately woven into the broader Digital Transformation Agenda. This educational blueprint serves as the cornerstone for instilling digital skills, commencing from primary education and extending through higher education. Ecuador is steadfast in equipping its students with fundamental Information and Communication Technology (ICT) knowledge, ensuring their proficiency in essential digital competencies.

The way forward

In the future, Ecuador could consider:

Allocate funds for the development of digital infrastructure in underserved regions, with a specific focus on improving broadband connectivity. This could include investments in laying down internet infrastructure and upgrading existing networks.

Develop a comprehensive training and consultation programme aimed at enhancing the digital skills of SME owners and employees. This could include workshops, seminars, and one-on-one consultations to address the specific needs and challenges faced by SMEs in Ecuador.

References

[4] BCE (2023), Informe de la evolución de la economía ecuatoriana en 2022 y perspectivas 2023, Banco Central Ecuador, https://contenido.bce.fin.ec/documentos/Administracion/EvolEconEcu_2022pers2023.pdf.

[5] BCE (2023), La economía Ecuatoriana reportó un crecimiento interanual de 0.4% en el tercer trimestre de 2023, https://www.bce.fin.ec/boletines-de-prensa-archivo/la-economia-ecuatoriana-reporto-un-crecimiento-interanual-de-0-4-en-el-tercer-trimestre-de-2023 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

[3] BCE (2022), Informe de la evolución de la economía ecuatoriana en 2021 y perspectivas 2022, https://contenido.bce.fin.ec/documentos/Administracion/EvolEconEcu_2021pers2022.pdf.

[1] BCE (2021), La pandemia incidió en crecimiento 2020: la economía ecuatoriana decreció 7,8%, https://www.bce.fin.ec/index.php/boletines-de-prensa-archivo/item/1421-la-pandemia-incidio-en-el-crecimiento-2020-la-economia-ecuatoriana-decrecio-7-8 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

[2] Heredia, A. and M. Dini (2021), Analysis of policies to support SMEs in confronting the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America, United Nations, https://hdl.handle.net/11362/46743.

[8] INEC (2022), Estadísticas de la empresa, https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/estadisticas-de-las-empresas/ (accessed on 5 June 2024).

[6] Ministry of Production Ecuador (n.d.), Ministerio de Producción, Comercio Exterior, Inversiones y Pesca, https://www.produccion.gob.ec/acuerdos-comerciales/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

[7] OECD (2019), Latin America and the Caribbean 2019: Policies for Competitive SMEs in the Pacific Alliance and Participating South American countries,, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/d9e1e5f0-en.

Note

← 1. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), people with adequate employment refer to those who have an income equal to, or higher than, the minimum wage and work 40 hours or more per week.