Paraguay responded to the social challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis by buttressing existing social programmes and implementing several ad hoc emergency social transfer programmes targeting food security and workers excluded from the social protection system. Paraguay is facing up to the challenge of building a comprehensive social protection system. This chapter examines how the implementation of emergency programmes during the pandemic hold valuable lessons for the future of social protection in the country. They can pave the way to expanding the coverage of income support measures, to improving targeting and delivery through digitalisation, and to expanding active labour market policies.

A Multi-dimensional Approach to the Post-COVID-19 World for Paraguay

2. An inclusive recovery: Social protection, access and quality to basic public services, vulnerabilities, and equal opportunities

Abstract

Box 2.1. Main findings and assessment

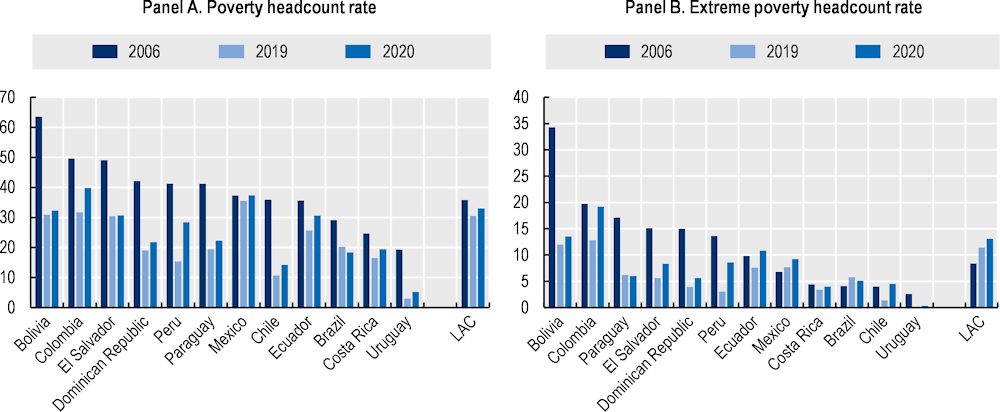

Benchmark data

Inequality in Paraguay is at the higher end of the range for OECD countries, as measured by the S80/S20 Household disposable income ratio. The country (13) has slightly higher inequality than Costa Rica (12.3), but far above the OECD average (5.4).

The percentage of young adults aged 15 to 24 in Paraguay not involved in an activity, whether a job, education or training, is 8% for men and 23% for women.

Paraguay experienced a fall in the percentage of the population living in extreme poverty in 2020 (from 6.2% to 6.0%) according to regionally comparable estimates. Among LAC countries, this trend was only matched in Brazil and Panama, while none of the OECD countries in Latin America experienced a similar decrease*.

Paraguay experienced a slight increase in subjective well-being: life satisfaction increased by 0.1 points between 2015 and 2020, rising from 5.56 to 5.65 between 2015 and 2020 on a score of 0 to 10, and then again to 6.1 in 2022.

Main findings on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Paraguay on public health outcomes was comparable to that in most countries in the region.

Most households in Paraguay experienced a reduction in their incomes. A reduction in food intake was the main coping strategy for most households, in particular at the onset of the pandemic and more so in the rural sector.

While poverty increased by 3 percentage points during the pandemic, from 19% in 2019 to 22% in 2021, extreme poverty fell slightly in Paraguay between 2019 and 2020.

Education was one of the most sectors affected by the pandemic, with schools in Paraguay being closed for 32 weeks.

Paraguay’s employment rate fell by 4 percentage points during the pandemic, with a more significant impact on women than men. The crisis impacted informal workers more than formal workers, but only for a relatively short period of time.

Policy responses

Paraguay quickly designed and implemented several ad hoc emergency social protection programmes in response to the pandemic:

The Ministry of Finance’s direct transfer programme, Pytyvõ, targeted informal workers – both own-account workers and workers employed by MSMEs – whose livelihoods had been affected by the pandemic and who had not previously benefited from public transfers. By the end of the crisis, Pytyvõ had reached 1.56 million beneficiaries.

The food security programme Ñangareko provided food vouchers worth 25% of the minimum wage (PYG 500 000, about USD 78) to 330 000 vulnerable families whose income came from subsistence activities and were strongly affected by social distancing measures.

Paraguay’s Social Security Institute (Instituto de Previsión Social, IPS) provided subsidies worth 50% of the minimum wage to formal workers (earning a maximum salary worth two minimum wages), whose contracts had been suspended due to the pandemic. In total,103 320 formal workers benefited from the programme by the end of the pandemic.

In addition to the new social assistance programmes, Paraguay also maintained and extended existing social protection programmes such as Abrazo, Adultos Mayores and Tekoporã.

Strategies for the recovery

To ensure a robust and sustainable recovery, Paraguay must tackle the structural problems exposed by the pandemic, while also learning from innovative approaches applied during the crisis:

The rapid development of emergency social assistance programmes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic shows that it is possible to expand social protection coverage. Paraguay’s emergency social protection programmes succeeded not only in quickly expanding the coverage of social protection to a relatively large share of the population but also in closing the coverage gap in the middle of the income distribution temporarily and providing a large share of independent and informal workers with social protection coverage. Electronic payment systems and innovative payment processes based on national identity cards facilitated the implementation of these programmes during the pandemic.

It is important to improve the targeting of social assistance programmes and streamline and consolidate the variety of existing programmes. A comprehensive national registry of potential beneficiaries could improve targeting and the impact of social assistance programmes in the future.

Paraguay requires systematic social protection for those not covered by the current system, most of whom are informal and independent workers. Independent and informal workers require different but co-ordinated social protection solutions. Formalisation and the generation of more quality jobs is a key part of the solution to improving access to financially sustainable social protection mechanisms for these population segments. Given Paraguay’s high levels of informality, simply extending formal workers’ social security to family members is not a solution.

Paraguay’s ad hoc transfer programme for formal workers during the pandemic has demonstrated the potential of unemployment insurance in Paraguay. These subsidies worked in practice like a non-contributory unemployment insurance. A contributory scheme would be financially more sustainable while acting as an automatic stabiliser in economic downturns, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic, thereby reducing the need for emergency support measures.

There is scope to further improve and expand active market policies in Paraguay, both in terms of capacity building and intermediation. At present, spending on active labour market policies remains very limited in Paraguay. Furthermore, employment services are concentrated in the capital city, with regional employment offices not always able to provide the full range of services. Institutional fragmentation and weak co-ordination remain important issues and there is scope to increase efficiency through digitalisation.

Notes: * Data are drawn from ECLAC’s regionally comparable poverty rate estimates (ECLAC, 2022[1]). National estimates differ in the levels of poverty but coincide in the movement and magnitude of changes (between 2019 and 2020 extreme poverty fell from 4.0% to 3.9%, while total poverty increased from 23.5% to 26.9%) (INE, 2023[2]).

Figure 2.1. The OECD COVID-19 Recovery Dashboard: Inclusive dimension

Source: All data for OECD countries have been extracted from the OECD Recovery Dashboard (OECD, 2022[3]). Data for Paraguay, Panel A and C are drawn from the ECLAC (2022[4]) Cepalstat (database), https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/index.html, Panel B from ILO (2022[5]) ILOSTAT (database), https://ilostat.ilo.org/, and Panel D from the Gallup World Poll (Gallup, 2022[6]).

The impact of COVID-19 on people in Paraguay

Although the COVID-19 pandemic affected people’s health and livelihoods, the government’s quick response mitigated the negative impact on Paraguayans’ well-being. The impact of the pandemic in Paraguay on public health outcomes was comparable to that in most countries in the region. However, in terms of mental health, Paraguayans exhibited the highest proportion of people among LAC countries reporting anxiety, unease, or concern during the months of the pandemic. With respect to income, most households experienced a reduction in income and many diminished their food intake accordingly, a coping strategy visible particularly at the onset of the pandemic and more so in the rural sector. While poverty increased during the pandemic, extreme poverty fell slightly in Paraguay between 2019 and 2020. Education was one of the sectors most affected by the pandemic, with schools in Paraguay being closed for 32 weeks. In terms of employment, Paraguay’s employment rate fell by 4 percentage points during the pandemic, impacting women more significantly than men. The crisis affected informal workers more than formal workers, but only for a relatively short period of time.

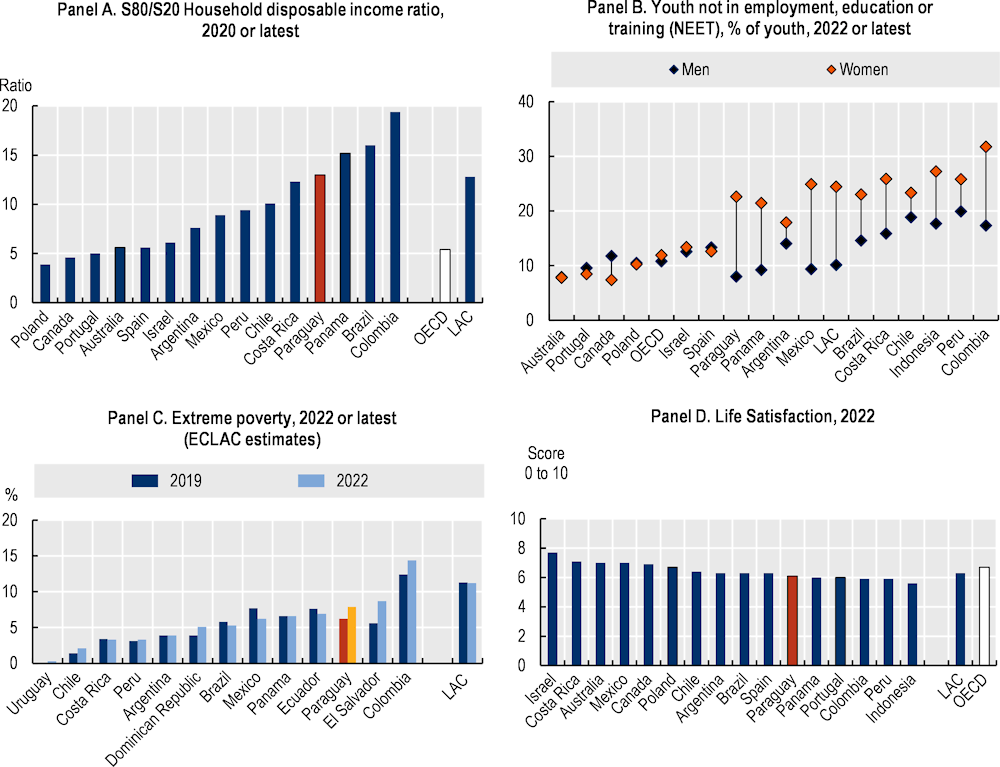

The public health dimension of the pandemic was comparable to that of other countries in the region

Public health outcomes from the COVID-19 crisis in Paraguay were comparable to those in most other countries in the region. As of August 2022, Paraguay had registered 710 890 cases of COVID-19 and recorded 19 289 deaths (and respectively 735 759 cases and 79 880 deaths by January 2024). While detection of cases is largely dependent on testing capacity, in per capita terms, the prevalence of COVID‑19 over the period (108 507 per million inhabitants) was lower but of the same order of magnitude as the average for Latin America and the Caribbean (131 677 cases per million inhabitants) and significantly lower than in other countries in the region (including Argentina, Chile and Uruguay) and also lower than the OECD average (401 866 per million inhabitants) (Figure 2.2). Death rates due to COVID‑19, however, were higher in Paraguay (2 931 per million population) than the unweighted regional averages for the LAC region and OECD countries (2 190 and 2 403 per million respectively).

Figure 2.2. Contagion and death rates from COVID-19 in Paraguay

Note: Cumulative data up to January 2024.

Source: Our World in Data COVID-19 dataset (Our World in Data, 2024[7]).

In response to the public health emergency, Paraguay took rapid and strong measures, imposing a six-week long total quarantine. The quarantine started on 20 March 2020, only 12 days after the first COVID-19 case was detected in the country. Most economic activity except for essential services such as healthcare and grocery stores ceased. All educational activities in schools and universities had already been suspended on 10 March 2020. The country then closed its borders on 24 March 2020. The quarantine was lifted through the gradual easing of restrictions in May 2020.

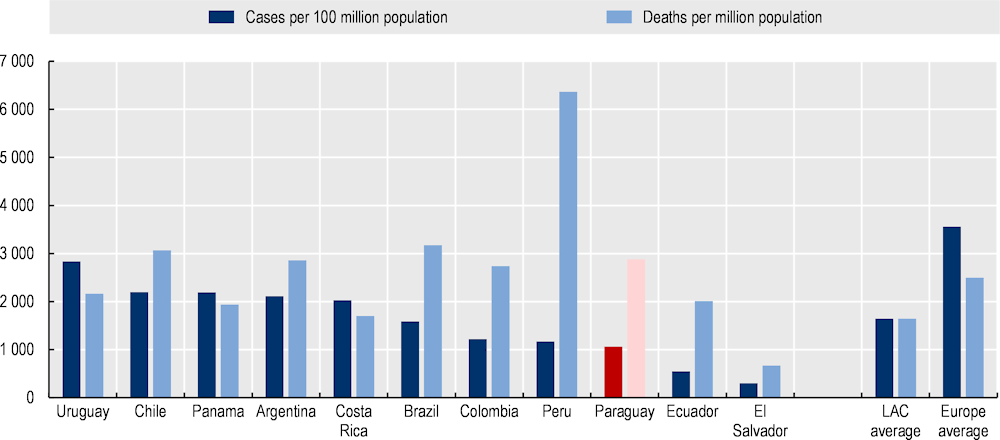

The COVID-19 pandemic affected multiple well-being outcomes beyond direct health impacts

Paraguayan citizens were particularly exposed to psychological distress during the pandemic. According to data gathered by High-Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS) carried out by UNDP and the World Bank during the pandemic, as of June 2021, 62% of the population reported anxiety, nervousness or concern during the months of the pandemic, one of the highest proportions among LAC countries (Figure 2.3). This result should be interpreted with care, however, as the evolution of the pandemic was not synchronous across countries and survey collection dates may correspond to higher pressure periods in some countries. Nevertheless, it is notable that absolute levels of mental health issues only fell marginally in the LAC region between mid-2021 and the end of 2021, while the ranking evolved only marginally, with Paraguay remaining above the LAC average (World Bank/UNDP, 2022[8]). Moreover, women were overrepresented among the group suffering from this form of psychological stress (70% of women compared to 53% of men). Two critical gender disparities explain the increased anxiety among women: increased responsibilities at home and gender-related disadvantages faced in the workplace.

Figure 2.3. Paraguayans suffered psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic

Share of the population that reported feeling anxiety, nervousness or worry (%) in mid-2021

Source: World Bank (2023[9]), High-Frequency Phone Surveys, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/hfps/?page=1&ps=15&repo=hfps.

The pandemic had a notable impact on incomes and livelihoods. According to the High-Frequency Phone Surveys carried out by the World Bank and UNDP during 2020 and 2021, as noted above, most households (61.7%) reported a reduction in income during the pandemic months. This was unequally distributed and affected households with children and elderly more than the average household. In particular, households with greater asset ownership were less likely to be affected (those with over three assets among a predetermined set reported a 56% reduction compared to 74% among those that had none), as were those with members with better education endowments (households with tertiary educated members reported a 47% reduction compared to 69% among those with only primary education or less).

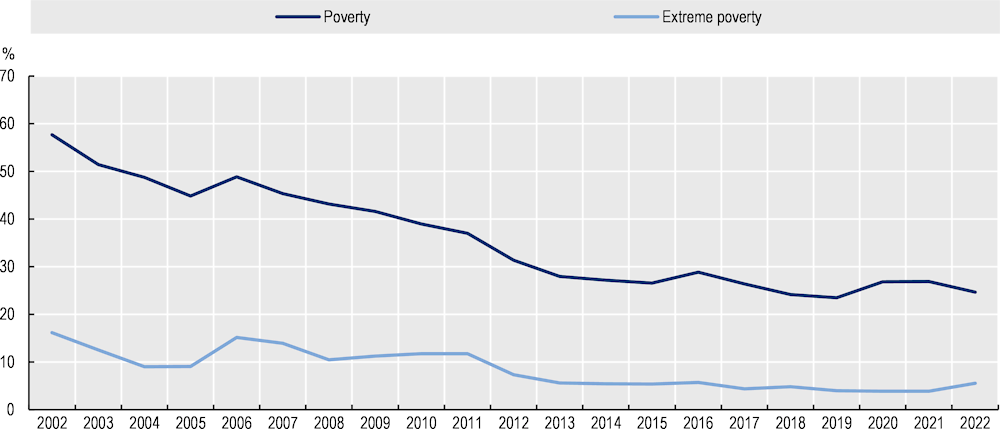

The COVID-19 crisis had only a moderate impact on poverty in Paraguay compared to most of the LAC region and did not raise the extreme poverty headcount rate. In fact, according to comparable estimates produced by ECLAC (ECLAC, 2022[1]), extreme poverty fell slightly. This is a remarkable result relative to the region. Poverty rose 3 percentage points in Paraguay between 2019 and 2020, from 19% to 22%, remaining below the regional average of 33% (Figure 2.4). Meanwhile, extreme poverty fell slightly between 2019 and 2020 from 4.0% to 3.9% (Figure 2.5). This result attests to the effectiveness with which emergency assistance was put in place to contain the imminent threat to the livelihoods of the most vulnerable population. Moderate poverty did increase in 2020, breaking the downward trend that it has followed in the past 20 years. However, moderate poverty fell back to pre-pandemic levels in 2023, reaching 22.7% (INE, 2024[10]).

Figure 2.4. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on poverty was more muted in Paraguay than the rest of the LAC

Poverty and extreme poverty headcounts (%)

Figure 2.5. The COVID-19 pandemic halted the downward trend in poverty in Paraguay

Poverty and extreme poverty headcount rates (%)

Source: INE (2024[11]), Principales indicadores de pobreza de la población por año de la encuesta (database), https://www.ine.gov.py/publicacion/4/pobreza.

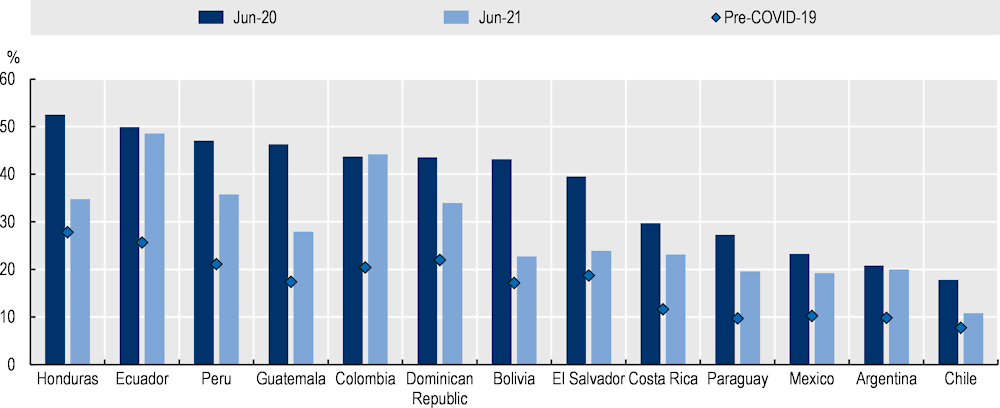

Despite the muted impact on poverty, the pandemic impacted livelihoods in Paraguay, as in the rest of the LAC region. For example, food insecurity increased considerably in a number of countries. Overall, the share of households facing food insecurity doubled with respect to the level registered before the pandemic (rising from 10% to nearly 20%) (World Bank, 2023[9]). The proportion of households reporting to have run out of food in the last month rose above 40% in nearly half the countries in Latin America by June 2020. In contrast, 27% of households in Paraguay reported similar conditions in June 2020, a proportion that fell to 20% by June 2021.

Figure 2.6. Food insecurity increased with the pandemic, albeit less than in other countries in the region

The household ran out of food in the past 30 days

Source: World Bank (2023[9]), COVID-19 LAC High-Frequency Phone Surveys, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/hfps/?page=1&ps=15&repo=hfps.

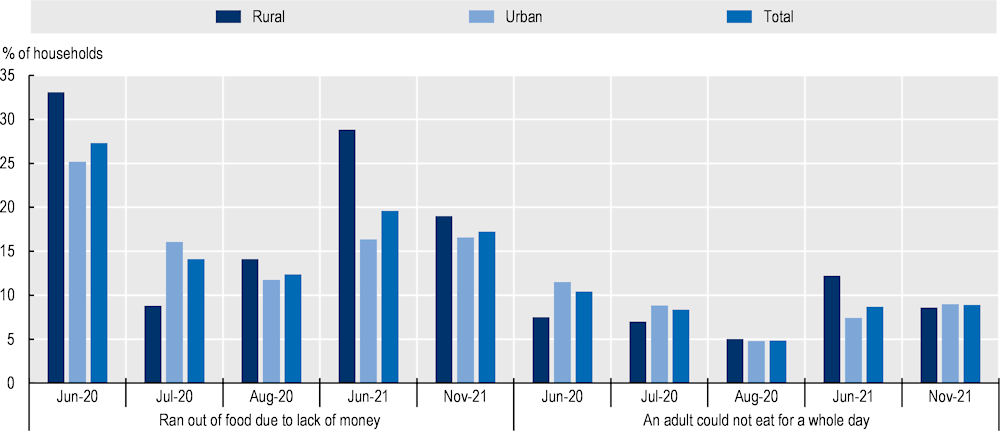

A reduction in food intake was the main coping strategy for most households, in particular at the onset of the pandemic and more so in the rural sector. Transfers helped to counteract the pressing effects of the pandemic on food security, although by mid-2021 structural food insecurity remained (Figure 2.7). In February 2020, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, only approximately 10% of households reported running out of food (World Bank/UNDP, 2022[8]). According to data from the FAO, 5.2% of the population was affected by severe food insecurity in 2019 prior to the pandemic and 24% of the population was affected by moderate or severe food insecurity, numbers which rose to 5.6% and 25.3%, respectively, in 2020 during the pandemic. However, food insecurity had been on a steady upward trend already prior to the pandemic: only 1.2% of Paraguay’s population was affected by severe food insecurity and only 8.3% of the population was affected by moderate or severe food insecurity in 2015 (FAO, n.d.[12]). Although data may not be fully comparable over time given gradual improvements in the measure of food insecurity in the country,1 the trend has corresponded to a more moderate increase in the prevalence of undernourishment (from 2.6% in 2015 to 4.2% in 2021) (UN DESA, n.d.[13]). Such reductions in food intake and nutrition could potentially have lasting effects, yet to be quantified. Individuals with underweight have an almost three times higher risk of respiratory disease and a higher risk for chronical heart disease, stroke and cancer (Development Initiatives, 2022[14]).

Figure 2.7. Food insecurity affected Paraguayans unequally during the COVID-19 pandemic

Proportion of households that faced food insecurity (%)

Source: World Bank (2023[9]), High-Frequency Phone Surveys, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/hfps/?page=1&ps=15&repo=hfps.

Education was one of the sectors most affected by the pandemic. Schools in Paraguay were closed for 32 weeks, a period longer the OECD (14.8) and LAC (25.8) averages (Figure 2.8). The shift to online education was particularly successful in maintaining educational continuity in Paraguay. According to the World Bank/UNDP High-Frequency Phone Surveys, overall school attendance was 92.8% in June 2021, among the highest rates in the region (World Bank, 2020[15]). However, the shift to online education is likely to have exacerbated existing significant inequality in education. Indeed, parental ability and availability and connectivity can impact learning outcomes and are both related to overall socio-economic status. Indeed, according to data from the PISA-D national report for Paraguay, the gap in performance between socio-economically disadvantaged and advantaged students was significant (70 points in reading) and close to the OECD average (88 points) despite a significantly lower average (OECD, 2019[16]; MEC, 2019[17]).

Figure 2.8. School closures in Paraguay were above the LAC and OECD averages

Number of weeks of school closures due to COVID-19, March 2020-May 2021

Note: OECD average includes the then 37 member countries. LAC average includes Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. Updated until 1 March 2021.

Source: OECD et al. (2021[18]) based on UNESCO (2021), Global monitoring of school closures due to COVID-19.

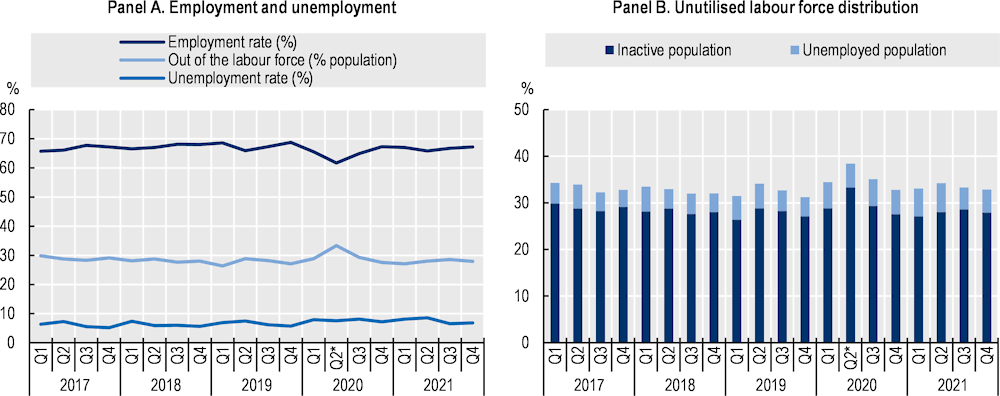

The COVID-19 pandemic had a sizeable impact on Paraguay’s labour market

The pandemic and the quarantine period in the second quarter of 2020 had a marked impact on the labour market in Paraguay. According to official data, the employment rate fell by 4 percentage points in the second quarter of 2020 (from 65.6% to 61.6%), with a larger impact on women (5.2 percentage points) than men (2.7 percentage points) (MTESS, 2022[19]).2 According to data from the High-Frequency Phone Surveys collected by the World Bank and the UNDP during the pandemic, significant churning occurred in the labour market. A quarter of workers lost their pre-pandemic jobs (of which 43.6%, including a high share of women, had moved to inactivity by June 2021), while 60% of previously inactive persons became active after the pandemic.

In aggregate terms the labour market had largely recovered within a year of the quarantine period. Labour force participation rates had returned to within a percentage point of their medium-term (2018-19) averages by the last quarter of 2020. Occupation rates rebounded in the last quarter of 2020 (from 61.6% in the second quarter to 67.2%, close to the medium-term average of 67.5%). However, quarterly occupation rates in 2021 remained about 1 percentage point below those of 2019 on a year-on-year basis. A year from March 2020, the labour market had recovered in terms of participation, and the distribution of unoccupied labour force between unemployment and population out of the labour force also returned to pre-pandemic dynamics (with the open unemployment rate falling back to 6.5% in the third quarter of 2021).

Figure 2.9. The labour market had largely recovered a year after the pandemic

Note: The unemployed population in Panel B is presented as a percentage of the working-age population.

Source: Observatorio Laboral (MTESS, 2022[19]).

The impact of the crisis on informality was also relatively short-lived. The crisis impacted informal workers more than formal workers, with non-agricultural informal work falling by almost 10% (a loss of 164 508 jobs) in the second quarter of 2020. Conversely, the recovery of the labour market was particularly strong in informal segments, leading to an increase in the share of informal work in the fourth quarter of 2020, before levels stabilised in 2021 at their pre-crisis levels. In fact, although registered employment (according to social security registries) fell during the first half of 2020, with a 3.7% reduction by July compared to March 2020, it had returned to pre-pandemic levels by April 2021 and had also recovered its pre-pandemic upward trend (MTESS, 2022[20]).

The response to the pandemic combined existing measures and ad hoc emergency programmes to support households and employment

The social protection system in Paraguay is designed to provide support and security to its citizens, especially those who are most vulnerable. At its core, the system encompasses a range of programmes aimed at ensuring healthcare, pension benefits and social assistance to cover the different needs of the population. The healthcare system operates under a mixed model that includes public, private and not-for-profit providers, offering services to employees, their dependents, and the impoverished. Pension schemes are fragmented; the Instituto de Previsión Social (IPS) manages retirement, disability, and survivor benefits for private sector employees, while a number of separate systems cover public sector employees, although coverage is limited mainly to formal sector employees. A sizeable social pension has increased in coverage, protecting elderly citizens in need.

Social assistance programmes in Paraguay target poverty alleviation and support for vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, people with disabilities and families in extreme poverty. These programmes include direct cash transfers, such as Tekoporã, which aims to reduce poverty by providing financial support and promoting access to education and health services. Another significant initiative is the Adultos Mayores programme, which provides a non-contributory pension to senior citizens who lack a contributory pension. These programmes form part of a broader effort to build a more inclusive society by addressing immediate needs and fostering long-term social and economic development.

Despite these efforts, challenges remain in extending coverage and enhancing the effectiveness of Paraguay’s social protection system. A significant portion of the workforce engaged in informal employment and the rural population often lack access to comprehensive social protection measures. Efforts to reform and expand the system are ongoing, aiming to achieve universal coverage and integrate more people into a cohesive and supportive social security framework. Strengthening the social protection system in Paraguay is crucial for reducing inequality and supporting sustainable development.

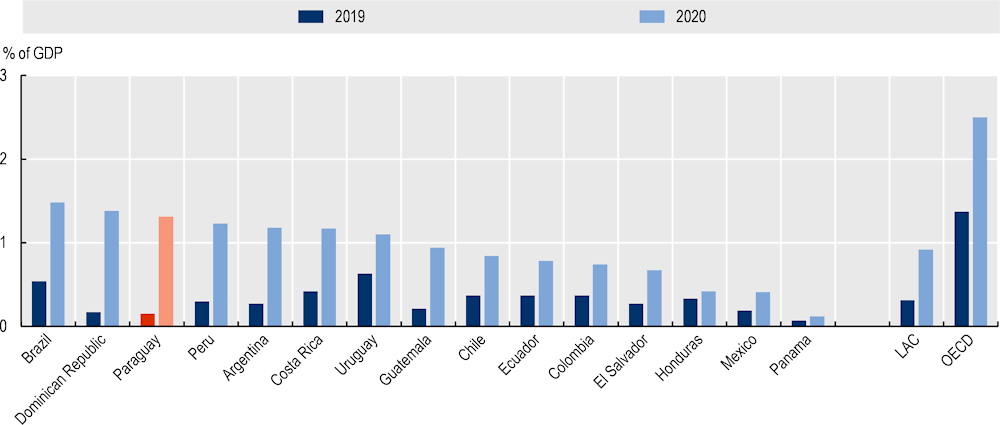

During the COVID-19 crisis, a large share of Paraguay’s budget for emergency support was directed towards social and health measures. Paraguay’s initial fiscal response to the pandemic was articulated by the Emergency Law (Law 6524/20), which set out a USD 945 million package (2.5% of GDP) and opened up the possibility for Paraguay to issue up to USD 1.6 billion in debt (a USD 1 billion bond was issued on 23 April 2020), while USD 390 million in existing credit lines were redirected towards emergency support measures. Some 34% of the USD 1.6 billion were used to make up for the shortfall in tax revenues and to strengthen and expand existing social assistance programmes (Tekoporã and Adultos Mayores), 26% was used for health measures and 28% for social protection (MH, 2022[21]). In total, Paraguay spent USD 620 million on existing and temporary emergency social protection programmes in 2020, with the largest share directed to Pytyvõ 1.0 and 2.0 (75%), followed by the subsidy for formal workers (16%) and Ñangareko (6.1%) (MH, 2021[22]).

Investment in the capacity of the health system

The emergency response included funding to increase the capacity of Paraguay’s health system. In total, USD 418 million – 26% of the USD 1.6 billion emergency package – were spent on health measures. The largest share of the health budget was allocated by the Ministry of Health (Ministerio de Salud Pública y Bienestar Social, MSPBS) (USD 381 million) for medication, biomedical equipment and protective clothes for healthcare personnel; COVID-19 vaccines; improvements in Paraguay’s healthcare system through the Ministry of Public Works (Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Comunicaciones, MOPC), outsourcing patients to private healthcare facilities; hiring additional healthcare staff and the payment of bonuses to healthcare staff for their extraordinary work during the pandemic (MSPBS, 2020[23]). Another USD 15 million or 3.5% of the emergency budget for health measures was used for the construction of 31 emergency centres and 22 molecular biology laboratories by the Ministry of Public Works. USD 5 million were spent on Pytyvõ medicamentos (see below). Funding was also provided directly to Paraguay’s University Hospital in Asunción, the Military Hospital and the Social Security Institute (IPS) (MH, 2022[21]).

Ad hoc social protection programmes in response to the pandemic

Pytyvõ transfers for informal workers

The Ministry of Finance (Ministerio de Hacienda) designed a direct transfer programme targeting informal workers whose livelihoods had been affected by the pandemic. Pytyvõ’s objective was to provide temporary relief and income support to informal and vulnerable workers – both own-account workers and workers employed by MSMEs – who prior to the start of the sanitary restrictions had not enjoyed any benefit or monetary support through government programmes such as Adulto Mayor or Tekoporã, and were not public officials. In the absence of a registry of informal workers, any person not appearing in any database, such as public servants, contributors to social security or beneficiaries of other social assistance programmes, were considered informal and eligible for Pytyvõ. Potential beneficiaries had to register online and transfers were made largely via electronic payment systems, bank accounts and an innovative system allowing beneficiaries to make payments with their national ID cards in order to avoid overcrowding at registration points (CAF, 2021[24]; Galeano and Aquino, 2022[25]).

Pytyvõ was implemented in two phases (1.0 and 2.0) in several payment cycles each worth 25% of the minimum wage. Pytyvõ 1.0 came into effect at the end of April 2020 and reached close to 1.2 million beneficiaries. Two disbursements were made in April and June 2020. Subsequently, Pytyvõ 2.0 reached another 764 000 beneficiaries, with a focus on those residing in border cities, who were most affected by the closure of borders and the decrease in cross-border trade. Three disbursements were made between September and December 2020. By the end of the pandemic, Pytyvõ had reached 1.56 million beneficiaries, with a total cost of USD 319 million, the equivalent of 0.9% of Paraguay’s GDP (Galeano and Aquino, 2022[25]; MH, 2021[22]).

Pytyvõ was effective in preventing increases in poverty and extreme poverty in Paraguay during the pandemic. An evaluation of Pytyvõ found that the programme raised the incomes of beneficiaries in a situation of poverty by 8.3% and reduced the probability of falling into extreme poverty by 4.1%. Similarly, Paraguay’s National Statistical Office (INE) found that the poverty rate would have been 1.3 percentage points higher without Pytyvõ (28.2% rather than 26.9%) in 2020, and that the extreme poverty rate would have been 0.6 percentage points higher (4.5% rather than 3.9%) (Galeano and Aquino, 2022[25]; INE, 2021[26]).

The Ñangareko food security programme

The National Emergency Secretariat (Secretaría de Emergencia Nacional, SEN) developed a targeted food security programme for vulnerable families. Ñangareko provided food vouchers worth 25% of the minimum wage (PYG 500 000, or USD 78) to 330 000 vulnerable families with incomes from subsistence activities, who were strongly affected by social distancing measures. Similarly to Pytyvõ, applicants had to meet certain requirements such as not benefiting from other social assistance programmes (e.g. Tekoporã or Adultos Mayores) and not being public officials. Ñangareko began with the distribution of food kits, but quickly evolved into the payment of monetary transfers through electronic systems in order to comply with social distancing measures and to avoid crowding at distribution points. Applicants had to submit their requests through online forms. Ñangareko cost in total USD 26 million (MTESS, 2020[27]; SEN, 2020[28]; MH, 2022[21]).

Benefits for formal workers with suspended contracts

Paraguay’s Social Security Institute (IPS) provided benefits to formal workers whose contracts had been suspended. The programme targeted workers making active contributions to IPS and with a maximum salary worth two minimum wages, whose contracts had been suspended as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The transfers amounted to 50% of the minimum wage. Public sector employees and workers earning more than twice the minimum wage were not eligible. In April 2020, 94 835 workers benefited, decreasing to 79 889 people in May and 58 972 in June. In total, 103 320 formal workers benefited from the programme (Montt, Schmidlin and Recalde, 2021[29]; IP, 2021[30]; MH, 2022[21]).

The IPS implemented several other emergency programmes directed at formal workers. While the benefit for formal workers with suspended contracts was the most important programme for this group, a quarantine transfer benefited 86 264 workers, a rest transfer benefited 24 459 workers suffering from COVID-19 and a vulnerability transfer benefited 1 861 workers. All these transfers including the benefit for formal workers with suspended contracts cost a total of USD 98 million (MH, 2022[21]).

Other programmes

Paraguay also implemented several other smaller scale programmes targeting populations in specific geographic areas and subsidising medication:

A specific programme (Pytyvõ medicamentos) was implemented to provide subsidies for the purchase of medicines for patients in intensive care in cases where hospital stocks were depleted. In total, 3 898 persons benefited from Pytyvõ medicamentos (MH, 2022[21]).

In April 2021, additional benefits for workers and businesses in 16 border towns with Argentina were introduced after new restrictions of movement were imposed on 27 March 2021 through Decree No. 5088/2021. Potential beneficiaries had to register on line and the programme was funded with the remainder of the Pytyvõ 2.0 financing up to USD 10 million. The subsidies aimed to reach around 43 000 workers and businesses through two to four transfers (IP, 2021[31]).

Expansion of existing social assistance programmes

In addition to the new social assistance programmes, Paraguay also continued and extended existing social protection programmes:

Health coverage for formal workers through the social security institute (IPS) was maintained for workers whose contracts were suspended.

Beneficiaries of Tekoporã, Paraguay’s main conditional cash transfer programme, received an extra payment. In total, 167 000 poor households benefited from an additional half instalment of the conditional cash transfer. Tekoporã is a means-tested conditional cash transfer programme operated by Paraguay’s Ministry for Social Development (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social) targeting poor families. Households with children below age 14, adolescents aged 15 to 18, people with disabilities or Indigenous people are eligible for Tekoporã. Tekoporã includes both social assistance and cash transfers, which vary depending on the number and type of beneficiaries in a household (OECD, 2018[32]; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2023[33]). As of end 2020, 164 309 families in poverty had benefited from Tekoporã (MH, 2020[34]). Coverage increased in later years reaching 184 503 at the end of 2022.

Social pension beneficiary payments (Adultos Mayores) were anticipated and the beneficiary base was expanded. Between April 2020 and December 2021, 72 799 new beneficiaries were included in Adultos Mayores as part of the recovery plan (IP, 2021[35]). Adultos Mayores is a non-contributory pension for residing elderly above the age of 65 in poverty, and consists of a monthly transfer equivalent to 25% of the minimum wage. Poor elderly without labour income, contributory pensions or other cash transfers from the state are entitled to Adultos Mayores (MH, 2020[36]; OECD, 2018[32]).

Abrazo is a means-tested conditional cash transfer programme targeted at working and street children below the age of 14 by the Ministry for Childhood and Adolescence (Ministerio de la Niñez y Adolescencia, MINNA). In addition to conditional cash transfers, the programme also provides working and street children and families with other types of support through specific centres, including psychosocial support and job placement support for mothers (UTGS, 2016[37]; Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay, 2023[38]; OECD, 2018[32]).

Other support measures for households and individuals

Other support measures for households and individuals in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic included utility bill waivers and the partial postponement of rent payments for housing:

Paraguay waived the payment of utility bills for basic services (electricity, phone services, water) for the months of March, April and May 2020 for vulnerable households and MSMEs (identified on the basis of past consumption). Other households could defer payments and make repayments in up to 18 instalments without interest (MTESS, 2020[39]).

Workers in border towns with Argentina benefited from additional support to pay utility bills in 2021. Decree 6274/21 established subsidies for up to 50% of water and electricity bills for formal workers and businesses in 16 border towns with Argentina, who benefited from the additional subsidies established in April 2021.

Failure to pay the rent would not be grounds for eviction until June 2020, provided that a payment of at least 40% of the monthly rent was made (Article 52 of Law 6524/2020). Debt could be repaid in instalments.

Social protection measures were ambitious and effective

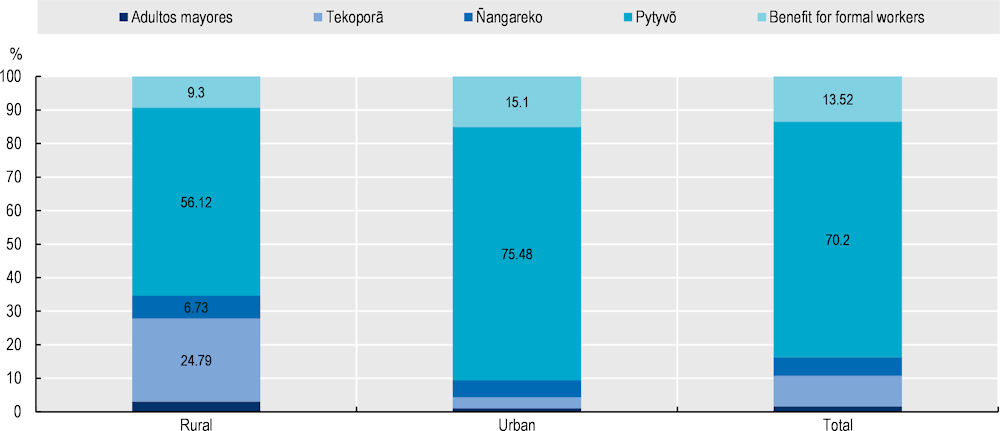

The emergency assistance programmes succeeded in quickly expanding the coverage of social protection in Paraguay during the pandemic. In June 2020, 42% of households had received emergency assistance in the context of the pandemic compared to only 14% on average in the LAC region, and a social protection coverage rate of only 31.4% of Paraguay’s population prior to the pandemic (ILO, 2022[5]) (Figure 2.10, Panel A). By mid-2021, when most emergency programmes had come to an end, 54% of households in Paraguay had received emergency assistance compared to 46% on average in the LAC region (Figure 2.10, Panel B). This is a remarkable achievement given that Paraguay’s social protection coverage through regular non-emergency programmes is low in comparison to other countries in the region (World Bank/UNDP, 2021[40]). The significant expansion of social protection during the COVID-19 pandemic was achieved largely as a result of Pytyvõ (Figure 2.11): 70.2% of households who received transfers through social assistance programmes during the pandemic benefited from Pytyvõ.

Figure 2.10. Paraguay’s social protection response to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled relatively broad coverage

Note: Panel B. For Brazil, emergency transfer coverage refers to 2020 only.

Source: World Bank (2023[9]), High-Frequency Phone Surveys, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/hfps/?page=1&ps=15&repo=hfps.

Figure 2.11. Expansion of social assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic was achieved mainly through Pytyvõ, in both rural and urban areas

Households covered by a social transfer by programme (% of households receiving social transfers), August 2020

Source: World Bank (2023[9]), High-Frequency Phone Surveys, https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/hfps/?page=1&ps=15&repo=hfps.

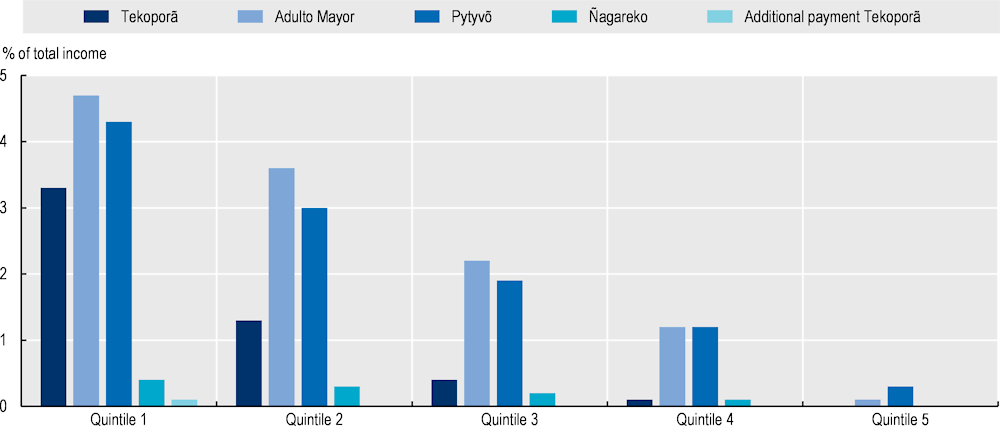

Paraguay’s emergency assistance programmes prevented increases in poverty. Without Tekoporã, Adultos Mayores and Pytyvõ, Paraguay’s official poverty rate would have reached 30.1% in 2020 rather than 26.9%, and Paraguay’s extreme poverty rate would have reached 6.5% rather than 3.9%. Without Pytyvõ alone, Paraguay’s poverty rate and extreme poverty rate would have been 28.2% and 4.5%, respectively, in 2020. Pytyvõ transfers accounted for 4.3% of the poorest quintile’s income and 3% of the second quintile’s income in the income distribution (INE, 2021[26]). The impact of the three social assistance programmes on inequality was also found to be positive, but much less pronounced than the impact on poverty (IMF, 2022[41]).

However, the high cost of these programmes makes them unsustainable in the long run. The cost of emergency assistance programmes developed during the pandemic amounted to 1.7% of Paraguay’s GDP over the years 2020 and 2021, while the cost of Tekoporã and Adultos Mayores accounted for 0.9% of GDP in 2021 (Table 2.1). Given Paraguay’s low government revenues (see Chapter 4), it would be hard to finance this increase in spending on social assistance over the long term without compromising the sustainability of public finances. In 2020, as a result of emergency measures and a decrease in revenues, Paraguay’s central government budget deficit amounted to 6.1% of GDP (MH, 2023[42]).

Table 2.1. Emergency social protection measures mobilised sizeable financial resources

Main emergency social assistance programmes by coverage and expenditure

|

Beneficiaries (thousands) |

Expenditure (% of GDP) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Emergency programmes, 2020-21 |

||

|

Ñangareko food aid programme |

285 |

0.1 |

|

Subsidies for informal workers Pytyvõ 1.0 and 2.0 |

1 232 |

0.9 |

|

Subsidies for workers with suspended contracts (IPS) |

103 |

0.2 |

|

Subsidies for public services |

0.3 |

|

|

Subsidies for medication |

3.1 |

0.01 |

|

Regular programmes (2021) |

||

|

Adultos mayores |

253 |

0.6 |

|

Tekoporã |

167 (families) |

0.3 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Mapa de inversiones (Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay, n.d.[43]) and budget execution information. Beneficiaries from contract suspension as indicated by Ministry of Finance accounts (MH, 2022[21]).

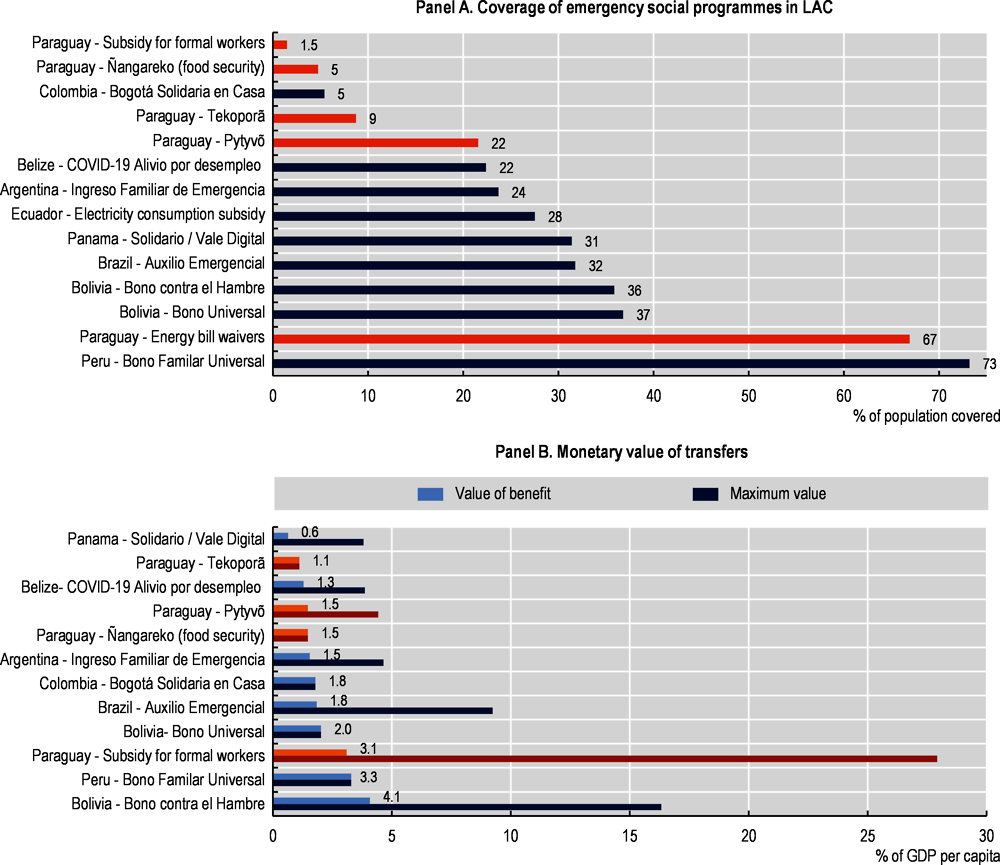

Furthermore, the most generous social assistance programme benefited only a very small share of Paraguay’s population. The subsidy to formal employees differs fundamentally from other emergency response programmes: it benefited only the 1.5% of Paraguay’s population that suffered from contract suspension during the pandemic while being covered by formal social security. Conversely, 21.6% of Paraguay’s population benefited from Pytyvõ, 82% of clients of the electricity company ANDE (or about 67% of the population) benefited from energy bill waivers, 4.7% of the population benefited from the food security programme Ñangareko and 167 000 families (or about 8.7% of the population) benefiting from Tekoporã received additional transfers. A single subsidy payment of the programme for formal workers amounted to 3.1% of Paraguay’s GDP per capita and nine monthly payments would amount to 27.9% of GDP per capita (the programme made payments until the end of 2021), whereas a single benefit of Pytyvõ amounted to only 1.5% of GDP per capita and the maximum benefit a person could receive amounted to 4.4% of GDP capita. Tekoporã and Ñangareko were even less generous (payments amounted to 1.1% and 1.5% of GDP per capita, respectively) (Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. Paraguay’s most generous emergency social subsidy benefited only a very small share of the population

Note: Panel A. Programme coverage was multiplied by average household size when programmes targeted households rather than individuals.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Cejudo et al. (2021[44]), Inventario y caracterización de los programas de apoyo al ingreso en América Latina y el Caribe frente a COVID-19, IDB, https://publications.iadb.org/es/inventario-y-caracterizacion-de-los-programas-de-apoyo-al-ingreso-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe.

The response and recovery policies hold lessons for the expansion of social protection and labour market policies

The inclusive growth agenda in national mid- and long-term development strategies

National development plan and sectorial strategies

Social security and employment are part of the second pillar of Paraguay’s National Development Plan (PND) Paraguay 2030 (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Paraguay 2030): inclusive economic growth. The PND sets the ambitious goal of universalising social protection coverage along with eradicating extreme poverty and reducing inequality. However, the PND Paraguay 2030 does not provide any information on how to achieve the objective of universal social security coverage with active labour market policies playing only a marginal role. The PND 2030 lays out policies for capacity building: aligning job training with demand from the productive sector, developing employability programmes for young people who have been left out of the education system, and quality control and regular updating of job training programmes. The PND 2030 further aims at boosting formalisation (Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay, 2014[45]).

Paraguay’s National Poverty Reduction Plan (PNRP) Jajapó (Plan Nacional de Reducción de Pobreza, Jajapó) aims at improving the quality of life of families in poverty, the economic conditions of the working age population, and social cohesion in backward regions and communities. The PNRP has three pillars: social protection, economic inclusion and social promotion. The social protection pillar aims at implementing a basic social protection system for poor families, based on six dimensions: health, food and nutrition, education and learning, income and work, housing and environment, and coexistence and participation. The three tools to achieve these objectives are i) accompanying poor households both in groups and individually, ii) creating a good social service offer within regions, and iii) transfers and subsidies (Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay, 2020[46]).

Paraguay’s National Employment Plan 2022-2026 (Plan Nacional de Empleo 2022-2026) was approved in May 2022. It aims at promoting decent employment by advancing policies and actions that contribute to economic recovery, stimulate demand, support reskilling, promote skills and capabilities that are in demand, and strengthen labour intermediation and institutional capacities. Its three main objectives are: i) generating more jobs, ii) enhancing productivity and employability, and iii) improving the quality of jobs. The plan is structured around three pillars: i) promoting demand for decent employment; ii) increasing employability and labour productivity; and iii) improving labour institutions to support decent employment. Improving the professional and job training offer to increase productivity and reskilling and enhancing the professional skills of the productive sector workforce figure among the strategic objectives of the second pillar. The plan further aims at strengthening Paraguay’s Public Employment Service (Servicio Público de Empleo, SPE), including through labour intermediation and capacity building. Promoting the approval of the unemployment insurance law is part of the document’s action plan (MTESS, 2022[47]; MTESS, 2022[48]; MTESS, 2022[49]; IP, 2022[50]).

Vamos! Social Protection System

Paraguay’s Vamos! Social Protection System is a public policy aimed at establishing a comprehensive social protection system, covering those parts of the population that are currently excluded. It aims at protecting Paraguay’s entire population against all risks and contingencies related to education, health, employment and other areas. Vamos! has three main pillars: i) social Integration of those living in poverty through education, health, housing and poverty reduction policies; ii) employability and productivity, and iii) contributory and non-contributory social protection. Co-ordinating and integrating social protection policies between the different ministries and government institutions that form part of the Social Cabinet (Gabinete Social) is a key part of the implementation process. To this end, Vamos! is governed by technical boards and a management committee at the national level, consisting of different institutions which implement social programmes (Gabinete Social, 2018[51]; Gabinete Social, 2019[52]; Gabinete Social, 2023[53]; IP, 2022[54]).

Implementation of Vamos! is ongoing. Paraguay’s Social Cabinet has defined a strategy and action plan, including numerical indicators and annual objectives until 2023, for implementing Vamos! Implementation started with a pilot phase in four regions of Paraguay. One of the key objectives is establishing an integrated social protection record (Ficha Integrada de Protección Social (FIPS)) for each individual. This process has begun in the pilot regions, for example, in Villeta, where integrated social protection records were established for around 2 900 individuals (Gabinete Social, 2018[51]; Gabinete Social, 2019[52]; Gabinete Social, 2023[53]; IP, 2022[54]).

Economic recovery plan

Social protection is a key element of Paraguay’s economic recovery plan Ñapu’ã Paraguay. Paraguay’s economic recovery plan was built around three pillars: i) public investment for employment generation, infrastructure and housing; ii) social protection; and iii) financing for economic growth. The social protection pillar aims at improving social protection coverage and strengthening Paraguay’s social protection system to prevent and alleviate poverty and social vulnerability. This is achieved by guaranteeing a minimum level of income as well as by maintaining incomes in the short term and raising them in the long run. The specific objectives are to facilitate the formalisation of companies and employment and employment generation, support the reskilling of workers, and provide direct subsidies for the most vulnerable. Specific measures include: Pytyvõ subsidies for informal workers; strengthening and extending the coverage of the social assistance programmes Abrazo, Adultos Mayores, Tekoporã and other food security and agricultural development programmes; improving the connectivity and Internet access of students; and prioritising the implementation of Vamos! Total financing for the social protection pillar amounts to USD 327.6 million (MH, 2020[36]).

Active labour market policies play an important role in Paraguay’s Plan for the Recovery of Employment (Plan de Reactivación del Empleo). Developed by the Ministry of Labour (Ministerio de Trabajo, Empleo y Seguridad Social, MTESS), the Plan forms part of Paraguay’s broader Economic Recovery Plan (Plan de Recuperación Económica Ñapu’ã Paraguay). The Plan has four pillars: i) sustaining employment through measures to protect decent work; ii) boosting formal employment generation; iii) increasing employability through reskilling; and iv) strengthening institutional capacity with an emphasis on innovation and technology. The plan was implemented in three phases: measures to maintain employment and encourage intelligent quarantine (March to June 2020); Phase 2 focused on employment recovery and reskilling (July to December 2020); and Phase 3 addressed the generation of new jobs through incentive programmes for Paraguayan firms and foreign investment combined with social security for the unemployed (January to June 2021). Reskilling is a key component of Paraguay’s Plan for the Recovery of Employment, and the country’s National Vocational Promotion Service (Servicio Nacional de Promoción Profesional, SNPP) and National Job Training System (Sistema Nacional de Formación y Capacitación Laboral, SINAFOCAL) have played key roles in its implementation. (Reinecke et al., 2020[55]; MTESS, 2020[56]).

Lessons for addressing structural challenges in social protection

Improving social protection in Paraguay is key to preserving social stability and optimising fiscal resources given the country’s vulnerability to external shocks. Paraguay is vulnerable to recurrent extreme weather events as a result of climate change, such as the recent drought (see Chapter 3), and external shocks to prices and markets as a result of uncertain geopolitics (IMF, 2022[41]). Such shocks can result in significant increases in poverty without adequate social protection. However, the repeated implementation of non-contributory emergency social assistance programmes, similar to the ones developed in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, would place a significant strain on Paraguay’s public finances.

Paraguay’s emergency social protection programmes succeeded in quickly expanding coverage to those left out of the system

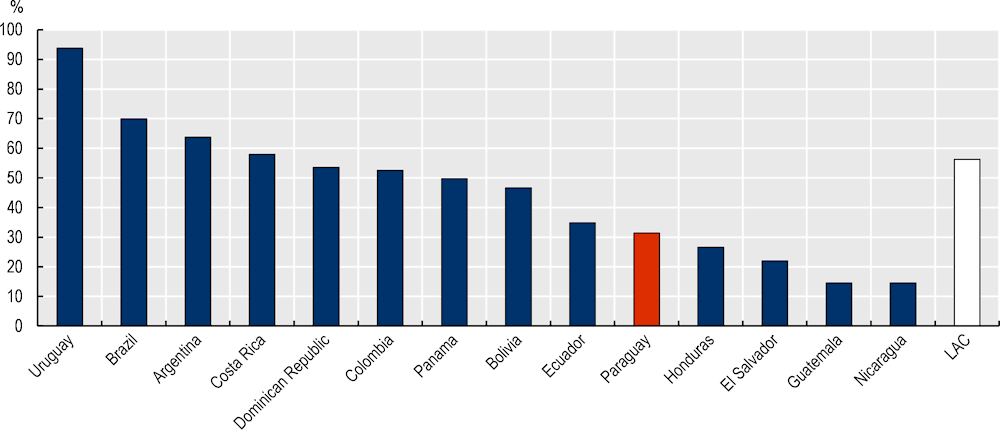

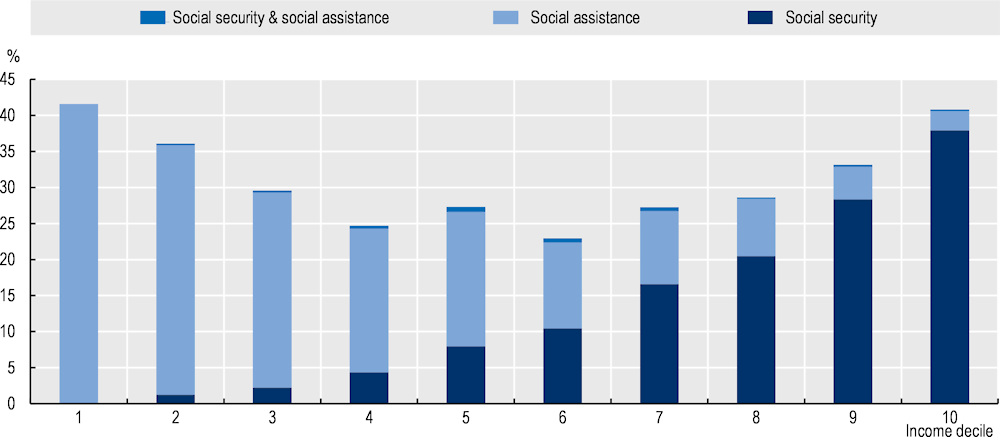

The rapid development of emergency social assistance programmes demonstrated the feasibility of expanding social protection coverage, most importantly to segments of the income distribution previously excluded. Prior to the pandemic, only 31.4% of Paraguay’s population was covered by social protection, compared to 56.3% in Latin America and the Caribbean on average (2020) (ILO, 2022[5]) (Figure 2.13). In 2021, 10.1% of Paraguayans were covered by social security (either actively contributing or receiving a contributory pension), while 16.3% received social assistance (INE, 2022[57]). Since social assistance is targeted at the poor and the main beneficiaries of contributory social security are high income earners, social protection coverage is lowest among the middle class (Figure 2.14). Paraguay’s emergency social protection programmes succeeded not only in quickly expanding the coverage of social protection to a relatively large share of the population, but also in closing this coverage gap in the middle of the income distribution, albeit temporarily. Their design reflects the gaps in Paraguay’s social protection system but also the potential of innovations in public policies.

Figure 2.13. Social protection coverage is low in Paraguay

Note: Population covered by social protection, 2020.

Source: ILO (2022[5]), ILOSTAT, https://ilostat.ilo.org.

Figure 2.14. Paraguay’s middle class is largely unprotected

Population covered by social security or social assistance, population aged 15 and over, 2021

Note: Income deciles are based on pre-transfer income. Social assistance includes conditional cash transfers (Tekoporã), in-kind transfers (food), emergency social assistance (Pytyvõ) and non-contributory pensions (merit, veterans, survivors of veterans and military or police personnel, Adultos Mayores). Social security includes contributions to a social security scheme and receipt of contributory pensions.

Source: INE (2022[58]), Encuesta Permanente de Hogares Continua (EPHC) Trimestral, www.ine.gov.py/microdatos/Encuesta-Permanente-de-Hogares-Continua.php.

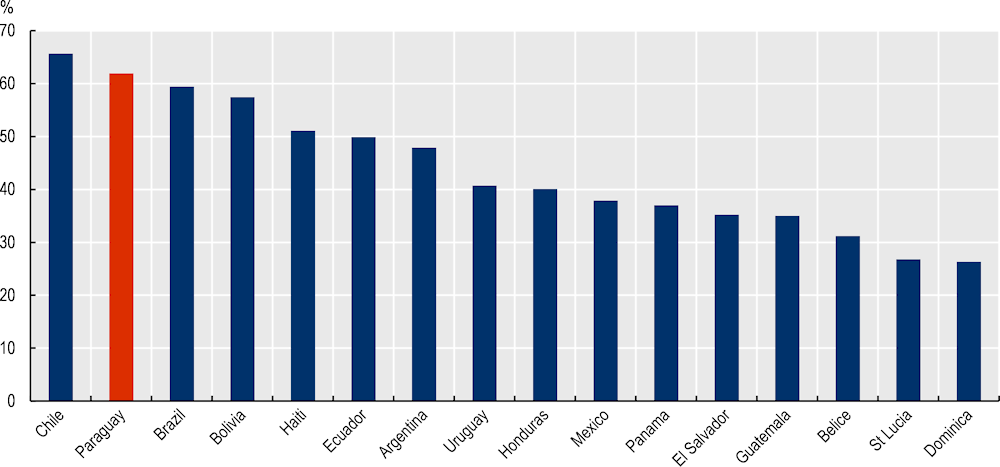

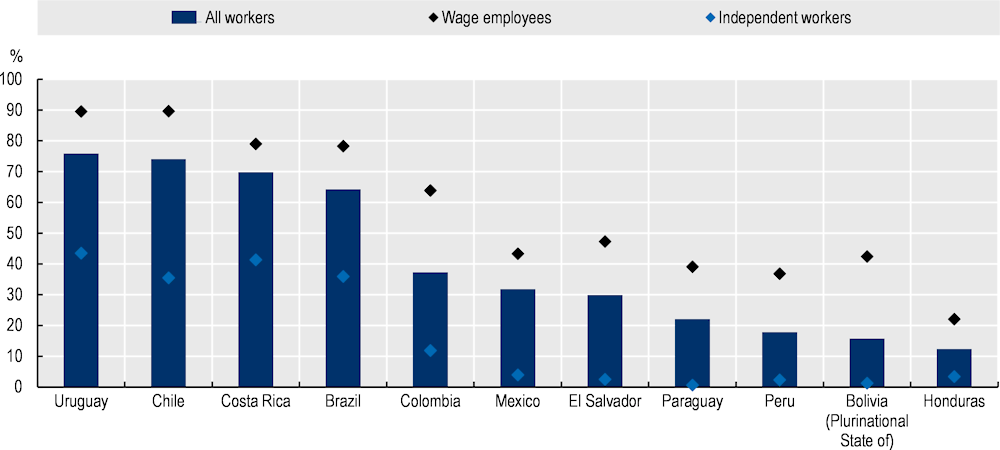

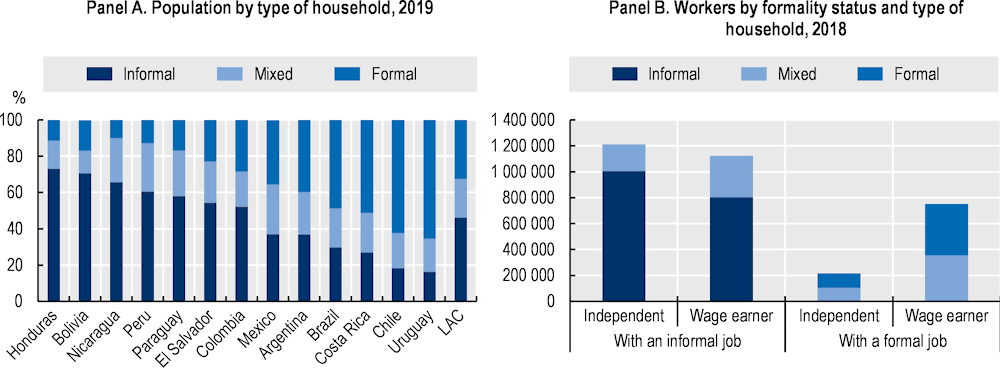

Emergency assistance programmes in the context of the pandemic succeeded in providing independent and informal workers with social protection coverage. Labour informality is high in Paraguay: informal employment amounts to 63.1% of non-agricultural employment (2022) (INE, 2023[59]) and to 69.1% of employment including the agricultural sector (2021) (ILO, 2022[5]). Some 60% of wage earners in Paraguay – about one-third of the population – are informal workers and 42.8% of the population are independent workers (defined as self-employed, employers and unpaid family workers) (2022) (INE, 2023[59]). Most of these independent and informal workers are excluded from Paraguay’s regular social protection system, which focuses on formal dependent wage employment: only 0.6% of Paraguay’s independent workers are covered by social security, via voluntary contributions (2021). This proportion is much lower than the average social security coverage in Paraguay (22%) and lower than coverage in other countries in the region such as Brazil, Chile or Uruguay, where close to 40% of independent workers are covered (Figure 2.15). Similarly, as a result of Paraguay’s high levels of labour informality, only 39.1% of wage earners are covered by social security in Paraguay compared to approximately 80% to 90% in neighbouring countries such as Brazil, Chile or Uruguay. Pytyvõ subsidies for self-employed and informal workers succeeded in providing social protection coverage for a large share of Paraguay’s self-employed and informal workers, who are excluded from the regular social protection system. It is estimated that Pytyvõ covered 62.8% of informal workers in Paraguay (MH, 2020[34]).

Figure 2.15. Social security coverage is particularly low among independent workers in Paraguay

Social security coverage, population aged 15-65, 2021

Notes: Independent workers are defined as self-employed, unpaid family workers and employers. Wage earners are salaried employees and domestic employees. Social security coverage is defined by active contributions to the pension system. In Paraguay, these contributions include all provisions of the social security system. Data for Chile, El Salvador and Mexico are for 2020 instead of 2021; data for Honduras are for 2019 instead of 2021.

Source: ECLAC (2022[4]), CEPALStat.

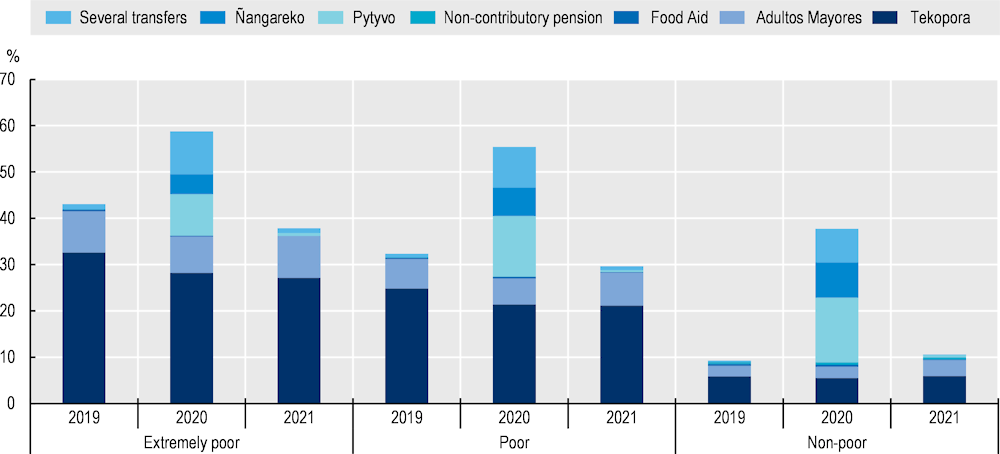

Emergency social assistance programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic succeeded in increasing the coverage of social assistance for the poor. Some 32.3% of the poor received public transfers in 2019, a share that increased to 50.9% in 2020 as a result of emergency social assistance programmes. Similarly, 43.1% of the extremely poor received public transfers in 2019, increasing to 55.6% in 2020 (Figure 2.16) (INE, 2022[58]). It is estimated that Ñangareko reached 51.1% of Paraguay’s poor (MH, 2020[34]).

Figure 2.16. The share of transfer recipients increased among the poor and the non-poor during the COVID-19 pandemic

Public transfer recipients (%) by poverty status based on pre-transfer income, 2019, 2020 and 2021

Source: Calculations based on INE (2022[58]), Encuesta Permanente de Hogares Continua (EPHC) Trimestral, www.ine.gov.py/microdatos/Encuesta-Permanente-de-Hogares-Continua.php.

Going forward, it is important to improve the targeting of social assistance and to streamline and consolidate the variety of programmes

The targeting of social assistance programmes could be further improved in Paraguay. A study published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that individuals with a job in 2019, whose income was negatively affected during the pandemic, were more likely to receive Pytyvõ transfers (IMF, 2022[41]). Meanwhile, Paraguay’s main regular social assistance programmes, Abrazo, Adultos Mayores and Tekoporã, target poor families with children and elderly, a demographic that accounted for 91.8% of poor households in Paraguay (as of 2021) (INE, 2022[58]; OECD, 2018[32]). However, only 56.2% of beneficiaries of public transfers are poor, 42.4% of benefiting households of Tekoporã are not poor, and half of the elderly benefiting from Adultos Mayores are not poor (as of 2021) (INE, 2022[58]). This is a consequence of the use of a proxy means test in the conditional cash transfer programme and possibly of success – as recipients’ incomes raise. However, the limited reach of the programmes in particular among the poorest is a cause for concern. The share of non-poor benefiting from public transfers increased further in the context of the emergency social assistance programmes during the pandemic: 9.3% of non-poor individuals and 2% of those in the highest income quintile received public transfers in 2019, shares which increased to 31.6% and 17.6%, respectively, in 2020 (Figure 2.16) (INE, 2021[26]). Social assistance programmes accounted for a non-negligible share of the income of those in the highest quintiles of Paraguay’s income distribution in 2020 (INE, 2021[26]) (Figure 2.17). This reflects the specific impact of the pandemic, which affected households with earning capacity but vulnerable livelihoods. It also implies that the emergency programmes, while demonstrating the feasibility of improving coverage, traded off efficiency against coverage and expediency at a time when both factors were particularly important.

Figure 2.17. Lower-income individuals benefit most from social transfers, but a non-negligible share is channelled to higher and middle-income individuals

Contribution of social transfers to the population’s income by quintile, 2020.

Source: Calculations based on INE (2021[26]), Principales Resultados de Pobreza Monetaria y Distribución de Ingresos EPHC 2020, www.ine.gov.py/Publicaciones/Biblioteca/documento/b6d1_Boletin%20Pobreza%20Monetaria_%20EPHC%202020.pdf.

Paraguay’s social assistance programmes remain fragmented across different ministries and institutions. While Tekoporã is managed by the Ministry for Social Development, Abrazo is managed by the Ministry for Childhood and Adolescence and Adultos Mayores by the Ministry of Finance. Similarly, during the pandemic, Pytyvõ transfers for informal workers were managed by the Ministry of Finance while the food security programme Ñangareko was designed and managed by the National Emergency Secretariat, and subsidies for formal workers were disbursed by Paraguay’s Social Security Institute. This arrangement resulted in overlaps and differences in the methods used to identify beneficiaries (Montt, Schmidlin and Recalde, 2021[29]; OECD, 2018[32]). The Vamos! social protection system aims at consolidating existing programmes and improving co-ordination among different institutions in order to develop a comprehensive social protection system in Paraguay (see above).

The COVID-19 pandemic underlined the importance of a registry of potential beneficiaries and the advantages of electronic payments and the digitalisation of programmes

One of the biggest obstacles to Pytyvõ and Ñangareko was the absence of a registry of potential beneficiaries. Paraguay lacked a systematised registry of individuals and households, which could have been used to identify potential beneficiaries of emergency social assistance programmes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Administrative data such as police records, lists of government employees and records of beneficiaries of other social programmes had to be used to identify the beneficiaries of Pytyvõ. In the absence of a registry of informal workers, any person not appearing in a database, such as public servants and contributors to social security, were considered informal and eligible for Pytyvõ. Effectively, 85% of households benefiting from emergency programmes, including Pytyvõ, were households where no member had previously received government assistance (Bordón et al., 2022[60]).

A comprehensive national registry of potential beneficiaries could further improve targeting and the impact of social assistance programmes in the future (IMF, 2022[41]). One option would be to maintain and further improve the database of people not usually found in administrative records which was generated to identify the beneficiaries of Pytyvõ and Ñangareko. This database could be used to improve targeting, the verification of means in conditional transfer programmes and to identify the beneficiaries of other social assistance programmes (Montt, Schmidlin and Recalde, 2021[29]). Furthermore, the integrated social protection records which are being developed in the context of Vamos! could eventually serve as a comprehensive unique national registry for the identification of beneficiaries of social assistance. However, at present, such records are only being developed for the populations of four pilot regions (Gabinete Social, 2023[53]).

Paraguay already has a registry of beneficiaries of existing social assistance programmes. The Integrated Social Information System (Sistema Integrado de Información Social, SIIS) is a management tool for social protection policies that centralises in a single registry information on beneficiaries, public social programmes and the budgets of these programmes. The single registry of beneficiaries contains information on people who receive or have received public benefits through a social programme (SIIS, 2015[61]). At the end of 2018, 2 051 247 beneficiaries of social programmes were registered in the SIIS (SIIS, 2018[62]). Created in 2015, the SIIS aims to optimise the implementation, follow-up and monitoring of public social services and benefits in Paraguay, and ultimately the efficiency of social spending. It aims to facilitate and improve the identification of participants of different social programmes implemented in Paraguay (SIIS, 2015[61]; SIIS, 2015[63]). However, the SIIS only covers actual beneficiaries of social assistance programmes and does not extend to potential beneficiaries.

Electronic payment systems and an innovative payment mechanism through national identity cards facilitated the disbursement of emergency financial assistance during the pandemic. Paraguay’s government entered into partnerships with local electronic payment providers to facilitate transfers of emergency assistance subsidies – both Pytyvõ and Ñangareko – to beneficiaries throughout the country, in order to avoid large crowds at payment centres. A large share of payments were made through electronic wallets, while payments to those unable to receive transfers through other channels were made via an innovative direct accreditation mechanism “Tarjeta Cédula”, which allowed people to make purchases using only their national identity cards (Bordón et al., 2022[60]; IP, 2020[64]).

The adoption of innovative payment mechanisms by emergency social assistance programmes during the pandemic promoted the use of digital technologies and enhanced financial inclusion. Pytyvõ and Ñangareko were targeted at vulnerable segments of Paraguay’s population, which are largely excluded from formal financial markets (CAF, 2021[24]). As a result of these emergency transfer programmes, a significant share of the population not previously familiar with electronic funds – especially among the more vulnerable – became familiar with electronic money accounts (Roa and Villegas, 2022[65]; Galeano and Aquino, 2022[25]). It is estimated that around 1.6 million new electronic money accounts were opened in Paraguay (Roa and Villegas, 2022[65]) and the beneficiaries of Pytyvõ were found to be 6.4% more likely to use electronic devices or to make financial transactions through smart devices (Galeano and Aquino, 2022[25]). Such electronic payment options and other digital tools open up new avenues for improving social protection coverage in Paraguay in the future.

The COVID-19 pandemic promoted the digitalisation of social assistance programmes. In addition to payments made through electronic payment systems, applicants to the social assistance programmes Ñangareko and Pytyvõ had to apply online rather than in person. This approach helped avoid overcrowding at registration points, corroborate information on applicants, and achieve greater traceability and transparency of beneficiaries (Montt, Schmidlin and Recalde, 2021[29]). Continued use of online forms for the registration of beneficiaries for permanent social assistance programmes could improve transparency and targeting in the future.

Paraguay requires systematic social protection for those excluded under the current system

Paraguay’s social security system, originally tailored for formal employment, fails to adequately protect a significant portion of the workforce in the informal or self-employment sectors. Barely half of the workforce is covered by formal social security despite efforts made since 2015 to promote inclusivity. This low uptake is largely attributed to the high cost of contributions for independent workers and those in MSMEs, underscoring the system’s failure to address the unique needs of a substantial share of the labour market (OECD, 2018[32]). The gap between the intended reach of social security and its actual coverage represents a critical challenge to policy design, which has thus far neglected the vast informal sector of the Paraguayan labour market.

The dominance of informal and independent work in Paraguay underscores the structural inadequacies of the social protection system. Approximately 60% of Paraguayans live in households where all labour income is from informal work, with nearly a fifth residing in mixed households that include at least one formal worker, and less than 20% in households with exclusively formal employment (see Figure 2.18, Panel A (OECD, 2022[66])). This distribution exposes the disconnection between social security policies and the lived realities of the majority, who navigate the volatility of informal income without the safety net of social protection. The challenges of securing retirement rights amid this volatility, coupled with strict contribution requirements, highlight the urgent need for systemic change to match the characteristics of the informal sector (Jütting and de Laiglesia, 2009[67]).

Given Paraguay’s high levels of informality, simply extending the social security of formal workers to family members is not a solution. In addition to being subject to high levels of labour informality (see Chapter 3), compared to other countries in the region, most of the informal employment in Paraguay occurs in households where all labour income is informal (Figure 2.18, Panel B). Extending formal social protection coverage to family members would therefore leave most informal wage earners still uncovered.

Figure 2.18. The majority of informal employment in Paraguay occurs in households where all labour income is informal

Source: OECD (2022[66]), Key Indicators of Informality based on Individuals and their Household (KIIbIH), www.oecd.org/dev/key-indicators-informality-individuals-household-kiibih.htm.

Paraguay needs to design systematic social protection for those not covered by the current system, most of whom are informal and independent workers. Although the new programmes implemented during the pandemic were devised in a temporary and limited manner, they could be made permanent over time or at least be reactivated quickly in the face of future crises (Montt, Schmidlin and Recalde, 2021[29]; IMF, 2022[41]). However, in both cases, it will be important to design sustainable financing mechanisms to avoid a deterioration in Paraguay’s public finances over the long term. A contributory unemployment scheme financed by employee and employer contributions could be an option for formal workers. However, independent and informal workers will require different but co-ordinated social protection solutions. Formalisation and the generation of more quality jobs is a key part of the solution to improve access to financially sustainable social protection mechanisms for these population segments.

The COVID-19 crisis has exposed the limitations of existing social protection systems and revealed potential policy options to address them. An important policy change observed during the crisis was the intended expansion of social protection coverage from the poorest populations to the “missing middle”, mostly informal workers who were not receiving social protection benefits – an approach that mirrors initiatives in other countries. Additionally, at the operational level, the COVID-19 crisis promoted greater inter-institutional co-operation and unprecedented use of pre-existing databases across the LAC region, to provide additional support to existing beneficiaries and identify new ones.

Incorporating independent workers into social protection systems requires a dedicated approach

Incorporating independent workers into the social protection system necessitates identifying suitable coverage levels and mechanisms tailored to their specific needs. Social insurance systems designed to cover employees face three challenges to incorporate independent workers. The first is the double contribution issue, that is determining who should be liable for employer contributions in the absence of an employer. Self-employed workers on average have lower incomes so charging them for both employer and employee contributions subject to statutory minima may result in exclusion. Conversely, granting identical cover for lower contributions can result in evasion and false self-employment. Second, fluctuating incomes complicate the calculation of contributions and the assessment of entitlements. Third, without employers to confirm work status and revenues, and greater control over their working conditions, moral hazard can make it difficult to cover independent workers in social insurance systems.

OECD countries employ a range of approaches to cover independent workers. In practice, coverage gaps are difficult to assess because they vary not only across countries but also across branches of social security. On the one hand, unemployment benefits are the least accessible to independent workers. In contrast, access to contingencies independent of work, such as social assistance schemes or family benefits, is similar regardless of status in employment. Maternity benefits often have separate provisions for independent workers, but where maternity coverage is compulsory, self-employed workers can either opt in voluntarily or have access to a separate benefit scheme. Pension rules typically differ between the self-employed and dependent employees: in some countries contributions by the self-employed are compulsory for basic pension pillars only (e.g. Denmark, Japan and the Netherlands), while in others affiliation is voluntary (Australia and Germany ) or workers can opt-out (Chile) (OECD, 2019[68]).

Relatively high levels of coverage can be achieved in a range of social protection systems. Social protection systems across OECD countries rely on a combination of universal, means-tested and contributory mechanisms. Systems differ in the relative importance of these three elements: some countries rely very strongly on means-tested benefits (Australia and the United Kingdom), while others depend mainly on insurance-based mechanisms (Spain) or layered systems where insurance-based mechanisms are supplemented by targeted safety nets (France). Finally, in some OECD countries (Austria, Germany and Hungary), universal benefits play an important role. It is possible to achieve comparable levels of benefit generosity regardless of the approach. In France and the United Kingdom, for instance, public benefits account for 8% of incomes of working-age households, despite relying on very different underlying mechanisms (OECD, 2023[69]).

Voluntary schemes are often used to offer cover to independent workers, but have a mixed record. When insurance is not mandatory, voluntary participation is often an option for independent workers to access a subset of social security branches. This can be achieved by allowing them to opt into the same schemes as dependent employees, auto-enrolling them with the possibility to opt out (as in Chile), or offering a similar but separate scheme. Voluntary schemes generally do not achieve high coverage. Moreover, in practice, voluntary affiliation is also confronted with issues of adverse selection, with only those more likely to receive benefits enrolling. When the scheme is separate from the general regime, the results is a financially weak regime due to the inability to pool enough risk to cover benefits.

Paraguay should use a combination of tools to expand social security coverage to independent workers

Options available to independent workers are ill-adapted to their circumstances and have so far proven ineffective. The invalidity, death and pension system was opened to voluntary contributions by independent workers in 2013. Workers contribute 13% of their declared income, which corresponds to both the employer and employee contributions of the general regime. Take-up has been extremely low. As of 2022, IPS had 888 active contributors (IPS, 2023[70]) out of a population of 1.5 million independent workers. One of the underlying reasons is that 77% of independent workers have labour incomes below the minimum wage. This includes contributing family workers, but also a large majority (88%) of own-account workers. In addition, women are particularly disadvantaged, given the average labour income gap which stands at 24% since 2016 (Serafini Geoghegan and Zavattiero, 2023[71]). Effective contribution rates are therefore very high, especially considering that access to the IPS health system is not possible for independent workers.

Paraguay has recently opened up the social insurance system to owners of microenterprises. While legal provisions have existed since 2016 through Law 5741, they had not yet been implemented. However, from January 2024, micro-entrepreneurs are able to access both the pension and the health social insurance systems, contributing 23% of the base, set at the highest wage paid to one of their employers (which cannot be below the minimum wage). Affiliation and contributions are to become mandatory gradually and will be enforced from July 2028. While this opens up the possibility of accessing health benefits, the contribution rate is likely to be prohibitive for many microenterprise owners.

Box 2.2. Policy workshop on social protection for independent workers

The OECD Development Centre, in collaboration with the governments of Panama and Paraguay, organised an international workshop entitled “Towards Social Protection Systems with Universal Coverage: Independent Workers” on 21 November 2023. The event gathered public sector officials, private sector representatives and academics from both countries, as well as international experts, reaching nearly 100 attendees. The participants discussed topical issues relating to the social protection coverage of independent workers and drew lessons from the social protection agenda in Panama and Paraguay.

The workshop featured contributions from officials of the Ministry of Labour and Social Security and the Ministry of Economy and Finance of Paraguay, the Ministry of Economy and Finance of Panama, the Ministry of Social Development of Uruguay, and the Social Security Fund of Costa Rica, who shared their valuable experiences related to integrating independent workers into contributory schemes for social protection. The event also featured the participation of experts from international organisations such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), ILO, ECLAC and the Ibero-American Social Security Organization (OISS).

The workshop served as a platform for policy dialogue, enabling participants to exchange insights on confronting similar challenges and to discuss the implementation of policy strategies to address these issues effectively. Key themes and ideas discussed during the workshop included the following:

Paradigm shift in social protection to embrace evolving forms of work. The world of work is undergoing a profound transformation, exemplified by the rise of teleworking, digital nomadism and flexible working hours, a change accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis. This evolution challenges the paradigms in use in social protection, necessitating a departure from traditional models to accommodate the diversity of modern employment practices. In the LAC region, where informal work is widespread, this shift marks a critical move towards developing more inclusive and adaptable social protection systems. By recognising and responding to the dynamics of the labour market, a new paradigm should aim to ensure comprehensive coverage and support for all workers, reflecting a significant evolution in the conceptualisation and implementation of social protection policies.

Adapted social protection mechanisms. LAC countries are called upon to design social protection mechanisms that are better tailored to the characteristics of their labour markets, where informal work is widespread. These design processes should also acknowledge that informality does not necessarily equate with poverty, recognising that many in this sector have the capacity to contribute.

Challenges posed by new forms of work. The emergence of digital platform-based work challenges traditional social protection mechanisms, necessitating adaptation to accommodate these modern employment models.

Transitional measures towards formal labour markets. The implementation of simplified regimes for informal workers must be seen as a transitional measure, one that aims to progress towards incorporating independent workers into the general contributory regime of social protection.

The need for social dialogue and consensus. Social dialogue is necessary to build consensus and ensure a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to social security.

Demographic challenges. Adapting social protection policies to demographic changes is crucial in this evolving landscape. The transformation of the demographic pyramid carries important implications for fiscal balance and public expenditure.