In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Paraguay mobilised sizeable fiscal resources, utilising its fiscal buffers, and put in place several credit support mechanisms. In the recovery period, it has increased capital expenditure above its historic average. Going forward, the country will need to rebuild fiscal buffers while building on the progress made in recent years in simplifying the tax system and setting a framework to mobilise sustainable development finance flows. This chapter examines lessons from the pandemic and recovery periods that can help Paraguay establish a comprehensive fiscal strategy and mobilise public and private resources towards a green and sustainable development path.

A Multi-dimensional Approach to the Post-COVID-19 World for Paraguay

4. A resilient recovery: Financing for development, short-term measures and recovery plans

Abstract

Box 4.1. Main findings and assessment

Benchmark data

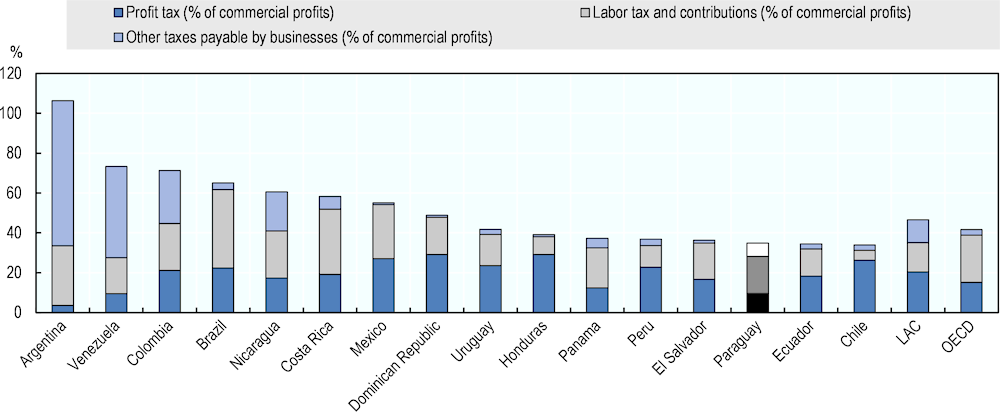

Paraguay had fully vaccinated 52.5% of the population against COVID-19 by October 2022, significantly below the OECD average (74%), as well as that of neighbouring countries Brazil (80.4%), Argentina (80.6%) and Chile (92.7%).

Gross fixed capital formation in Paraguay stood at 21.8% of GDP in 2022, a level comparable to the OECD average (22.6%).

Central government debt was 30.1% of GDP in 2021, well below the OECD average, and lower than OECD countries in the region such as Mexico (40.7%) and Chile (36.3%).

Average exposure to particulate matter (PM) pollution (12.8 micrograms per cubic meter) is lower in Paraguay than in OECD countries (13.9) and in the LAC average (18.6). However, unlike in OECD countries, 100% of Paraguay's population is exposed to more than 10 micrograms of fine particles (PM2.5) per cubic metre, the maximum level according to the WHO guidelines in force until 20211. This value is above the OECD average of 62% in 2019.

GHG emissions excluding land use, land use change and forestry reached 5.5 tCO2eq per capita in Paraguay in 2017, below the OECD average of 10.5 tCO2eq (in 2020). However, land use, land use change and forestry contribute significantly to GHG emissions.

The amount of materials used for consumption (20.7 tonnes per capita) is above the OECD average (17.5), with a larger amount of material per capita allocated to the Paraguayan economy, albeit markedly below countries such as Finland (31.24) that top the ranking, and below LAC countries such as Chile (53.0).

Main findings on the impact of COVID-19

Paraguay responded quickly to the pandemic by redirecting funds and mobilising additional resources. Emergency Law 6524, approved in March 2020, included a fiscal package of USD 1.99 billion. In view of the protracted nature of the crisis, in 2021 the government approved Law 6809 on Economic Consolidation and Social Containment (Consolidación Económica y Contención Social), which included measures to disburse an additional USD 365 million.

Paraguay’s sound fiscal discipline enabled the country to increase its debt from 22.3% of GDP in 2018 to 37.7% of GDP in 2021, while retaining a moderate level of indebtedness.

However, low tax revenues constrained government expenditure during the pandemic. Paraguay’s tax revenues amounted to only 13.4% of GDP in 2020, compared to 21.0% on average in the LAC region and 33.6% on average in the OECD.

Policy responses

The government implemented several mechanisms to increase fiscal space for emergency support measures as well as to enhance the liquidity of financial institutions:

Paraguay suspended its Fiscal Responsibility Law and expanded its fiscal deficit limit to 3% in order to finance emergency measures.

Paraguay temporarily reduced public sector wages in 2020 to free up financial resources for emergency support measures.

To support financial institutions, Paraguay announced three liquidity windows amounting to USD 3 707 million, equivalent to 10% of Paraguay’s GDP. The National Emergency Credit Facility provided access to USD 760 million, the Facilidad de Crédito por Desencaje enabled financial institutions to access USD 957 million in reserve requirements for new loans to sectors affected by the pandemic, and a third liquidity window allowed financial institutions to discount high credit quality portfolios with repurchase agreements. Furthermore, new loans to businesses made up to the end of 2020 were exempted from reserve requirements for 18 months, and reserve requirements for other loans were reduced.

Paraguay increased investment in infrastructure. The country’s economic recovery plan Ñapu’ã Paraguay included several infrastructure investment projects including, crucially, the construction and rehabilitation of roads.

Strategies for the recovery

To ensure a robust and sustainable recovery, Paraguay must tackle the structural problems exposed by the pandemic, while also learning from innovative approaches applied during the crisis:

Establishing a clear post-COVID-19 fiscal consolidation path is key to reverting to macroeconomic stability. On the expenditure side, this would require reducing inefficiencies in public spending and moving from current towards capital expenditure. On the revenues side, there is a need to expand the tax base by eliminating inefficient tax exemptions, improve the tax structure in order to increase the progressivity and equity of Paraguay’s tax system, and enhance tax collection through digital tax services. A high reliance on indirect taxes and flat rates is a particular challenge in Paraguay, with the result that the tax system has a very modest impact on income inequality.

The COVID-19 recovery represents an opportunity for Paraguay to explore new debt instruments in order to mobilise additional private and public resources to finance a green and sustainable recovery. Expanding Paraguay’s market for green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds represents one opportunity. While Paraguay was the first country in Latin America to adopt SDG bonds as part of its national regulation in 2020, it still lags behind other LAC countries in the issuance of sustainable debt securities. Tapping into multilateral financial resources via climate funds constitutes another opportunity for Paraguay. At present, Paraguay has received USD 146.4 million in financing through the Green Climate Fund (GCF) for six projects.

1. The WHO guidelines updated in 2021 state that annual average concentrations of PM2.5 should not exceed 5 micrograms per square meter.

Figure 4.1. The OECD COVID-19 Recovery Dashboard: Resilient and Green dimensions

Note: Panel D: LULUCR refers to land use, land-use change and forestry.

Source: All data for OECD countries has been extracted from the OECD Recovery Dashboard. For Paraguay, data for Panel A are from WHO (WHO, 2023[1]), data for Panels B and E are from the World Bank (2024[2]), data for Panel C are from the IMF (2023[3]), data for Panel D are drawn from national reports collected by the UNFCCC (2023[4]) and data for Panel F from the OECD Green Growth Indicators (OECD, 2017[5]).

Paraguay’s response to COVID-19 was enabled by its fiscal buffers

Sound fiscal policies and discipline benefited Paraguay during the COVID-19 pandemic. Government debt stood at only 22.3% in 2018 prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Paraguay compared to 67.1% in LAC on average. Although Paraguay’s government debt rose sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic to 37.7% in 2021 and 40.5% in 2022, this is still far below LAC average of 68% (Figure 4.2) and the OECD average of 106%. Paraguay has a record of fiscal prudence and since 2013, a Fiscal Responsibility Law (FRL) caps central government budget deficits at 1.5% of GDP (FitchRatings, 2022[6]; OECD, 2018[7]; World Bank, 2022[8]). As a consequence, Paraguay had sufficient fiscal space to increase expenditure during the pandemic despite relatively low government revenues (Figure 4.4). This move was facilitated by the suspension of the FRL to finance emergency measures and by a global context of low interest rates and ample international liquidity.

Figure 4.2. Despite an increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, Paraguay’s government debt remains low

Gross general government debt (% of GDP)

Source: IMF (2024[9]), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April.

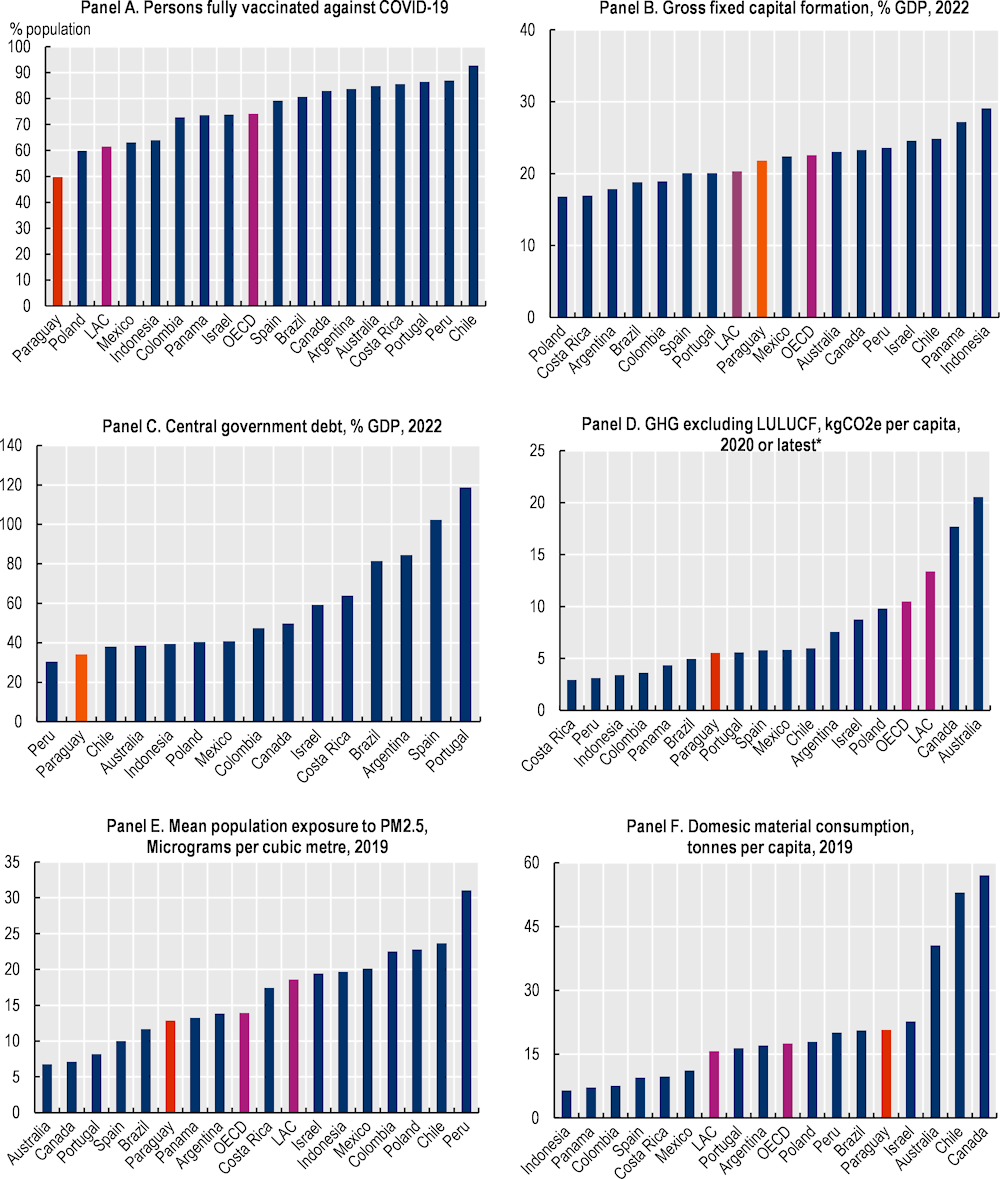

Paraguay responded quickly to the emergency by redirecting funds and mobilising additional resources. Emergency Law 6524, approved in March 2020, included a fiscal package of USD 1.99 billion, of which USD 1.6 billion came from new credits approved under the Emergency Law and USD 390 million from previously-approved debt redirected towards the COVID-19 crisis response. At the end of 2021, these emergency lines had reached a level of execution of 99% and 95%, respectively, implying an average execution of the Emergency Fund of 97%. USD 4 million was not assigned and USD 13 million was not executed, for a total of USD 17 million (MH, 2022[10]). A majority of resources were directed to the emergency from different lines of spending, including health (25.5%), new social protection programmes established ad hoc during the COVID-19 crisis (22.4%) and support to MSMEs (13%). Spending on salaries and debt also increased to cover the new hires necessary to meet pandemic demand and higher financing needs (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. The Emergency Law mobilised substantial resources to address priority needs

Total distribution of USD 1.99 billion under articles 33 and 35 of the Emergency Law, as of 31 December 2021.

Source: Own elaboration based on Emergency Law (2020) and Ministerio de Hacienda (2022[10]), Paraguay ante la pandemia, vol. 4.

To mitigate the negative socio-economic effects of the resurgence of COVID-19 infections, especially between March 2021 and June 2021, the government approved Law 6809 on Economic Consolidation and Social Containment (Consolidación Económica y Contención Social) in 2021. This law included measures totalling USD 365 million including USD 250 million derived from the IMF Special Drawing Rights, USD 50 million from Petropar, USD 25 million destined to the AFD from the emission of Treasury bonds and the rest from fund reallocations.1 Of these resources, USD 262 million were assigned to the Ministry of Health and to the payment of pensions and Adultos Mayores. The remaining funds were directed to subsidies and the creation of a Trust Fund by the BNF to support credit to MSMEs for the hotel, gastronomy, events, tourism and entertainment sectors; to the food security programme managed by the Secretaría de Emergencia Nacional (SEN); and to the Ministry of Urbanism (MUVH) for social housing projects (Congreso Nacional de Paraguay, 2021[11]; MH, 2022[10]).

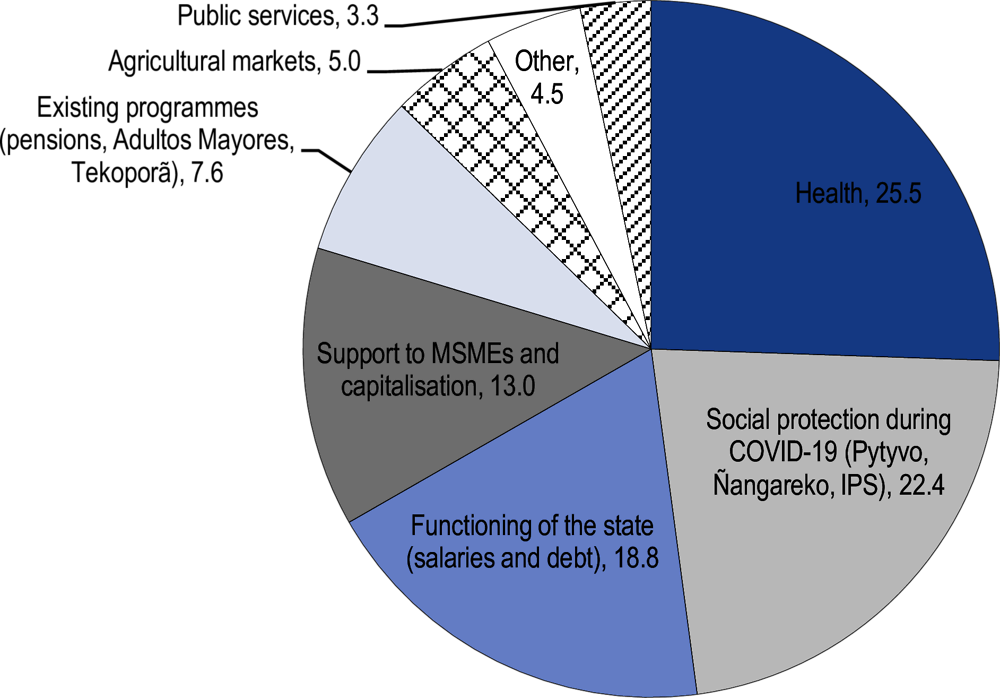

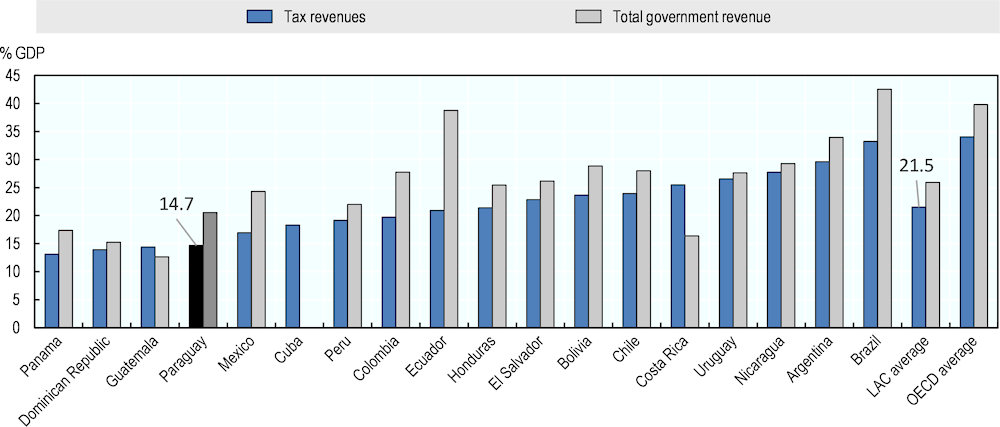

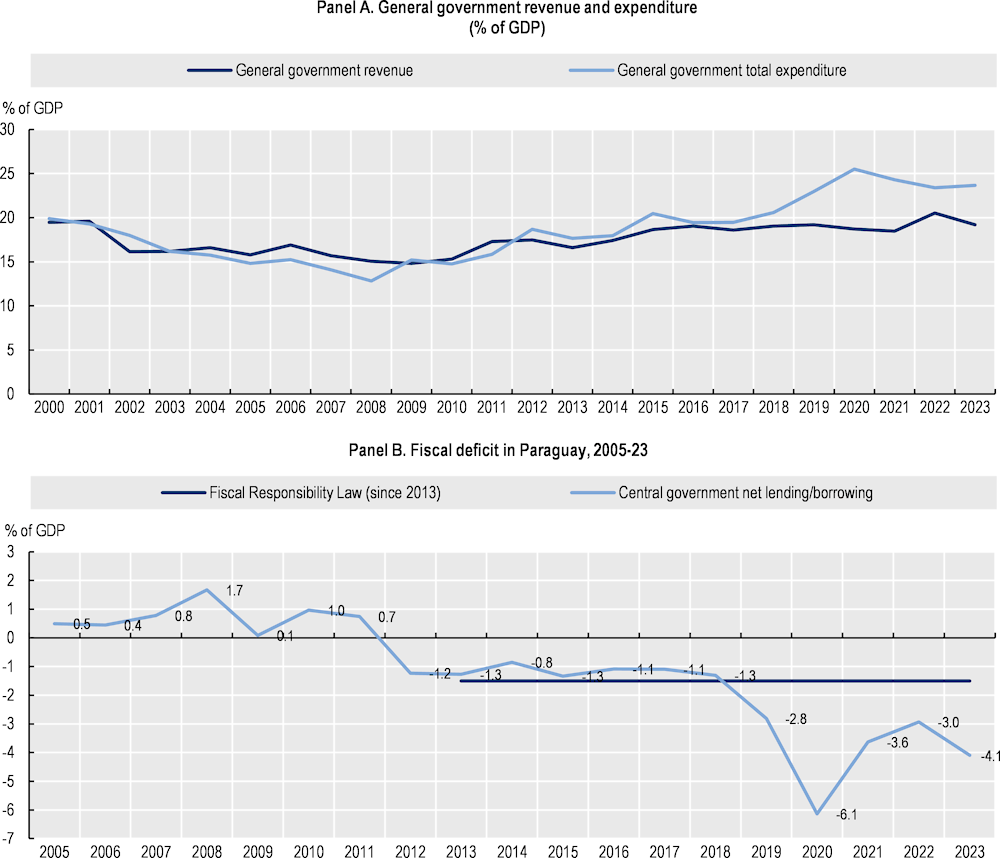

Paraguay’s low tax revenues constrained government expenditure during the pandemic. Paraguay’s tax revenues amounted to only 13.4% of GDP in 2020, compared to 21.0% on average in the LAC region and 33.6% on average in the OECD. By 2022, tax revenues had increased to 14.7% of GDP in Paraguay, compared to 21.5% in the LAC region and 34.0% on average in the OECD (Figure 4.4). Furthermore, tax revenues have increased only slowly over time in Paraguay (Figure 4.5, Panel A). These low tax revenues are partly compensated for by non-tax revenues through electricity exports from the Itaipú and Yacyretá binational hydroelectric plants (Figure 4.4). Royalties from electricity exports from the binational hydroelectric plants have averaged 3% of GDP since 2000. However, these revenues are volatile due to changing weather conditions, which are exacerbated by climate change. For example, hydroelectric power export revenues decreased by 12% as a result of a drought in the first four months of 2022 compared to the previous year. Together with pressure for counter-cyclical spending in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, this shortfall in revenues has exerted pressure on Paraguay’s government budget deficit (FitchRatings, 2022[6]) (Figure 4.5, Panel B). Paraguay closed 2022 with a fiscal deficit of 3.0% of GDP, in line with its planned fiscal consolidation path and commitments made in the context of a Policy Co-ordination Instrument Programme established with the IMF (IMF, 2023[12]). However, the performance of public finances in 2023 was worse than expected and the deficit grew again to 4.1% of GDP. Overall, Paraguay’s total government revenues remain considerably lower than in most other LAC countries (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. Paraguay’s tax revenues remain low but non-tax revenues are significant

Tax and non-tax revenues (% of GDP), 2022

Note: The LAC average for tax revenues represents the unweighted average of 26 LAC countries and excludes Venezuela due to data availability issues. LAC averages and OECD averages for total government revenue are unweighted averages of available country-level data.

Source: OECD et al., Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2024, and IMF (2024[9]), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024.

Figure 4.5. The gap between government revenues and expenditure widened during the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: A. IMF (2024[9]), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024. Panel B. Estado de Operaciones del Gobierno, Administración Central, Ministerio de Hacienda, Paraguay, https://economia.gov.py/index.php/download_file/view/1677/447.

Paraguay responded to the pandemic by increasing liquidity and increased investment to boost the recovery

Suspension of the Fiscal Responsibility Law. In March 2021, the fiscal deficit limit of 1.5% established by the Fiscal Responsibility Law was suspended to finance emergency measures. The Ministry of Economy and Finance exceptionally expanded the fiscal deficit limit to 3% in 2022 and foresees a return to the limit of 1.5% established in the Fiscal Responsibility Law by 2024.

Reduction in public sector wages. In March 2021, public sector wages between five and ten times the minimum wage were reduced by 10% and wages more than ten times the minimum wage were reduced by 20% in April, May and June 2020. Family allowances and overtime payments of public employees were suspended (except for the Ministry of Health). Similarly, subsidies for political parties were suspended.

Suspension of the calculation of arrears. Paraguay’s Central Bank granted renewals, refinancing or restructuring of the principal of any loans (including accrued interest and other charges) that on 29 February 2020 were no more than 30 days in arrears, and the interruption of the calculation of arrears for these loans (Resolución N° 4, Acta N° 18 del 18/03/2020).

Suspension of penalties for the rejection of three cheques as a result of insufficient funds. In March 2020, penalties for the rejection of three cheques due to insufficient funds, namely the closure of the bank account concerned, were suspended until 1 July 2020 (Law No. 6524/20).

Exemption from reserve requirements for new loans to MSMEs. In March 2020, Paraguay’s central bank, the Banco Central del Paraguay (BCP), decided that new loans granted up to 30 June 2020 to businesses, preferably, MSMEs, would be exempted from reserve requirements for a period up to 18 months (Resolución N° 23, Acta N° 23 del 02/04/2020). Subsequently, this measure was extended until the end of 2020 (Resolución N° 35 del 10/06/2020). Furthermore, overall reserve requirements were reduced by 2% in April 2020 to increase banks’ financial resources for loans.

National Emergency Credit Facility for financial institutions. In March 2020, Paraguay’s central bank established a National Emergency Credit Facility (Facilidad de Crédito por la Emergencia Nacional, FCE) of USD 760 million to provide liquidity to financial institutions through repurchase agreement (REPO) operations for credit support to economic agents affected by the COVID-19 crisis, especially SMEs (Resolución N° 1, Acta N° 21 del 30/03/2020).

Facilidad de Crédito por Desencaje (FCD) for financial institutions. The Facilidad de Crédito por Desencaje allowed financial institutions to use the resources deposited as reserve requirements – an estimated USD 957 million deposited both in local and foreign currency – to grant new loans to sectors affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (Resolución N° 1, Acta N° 21 del 30/03/2020). The National Emergency Credit Facility and the Facilidad de Crédito por Desencaje amount to 4% of Paraguay’s GDP.

Liquidity window for financial institutions. In April 2020, the BCP implemented another liquidity window in addition to the FCE and FCD, which allowed financial institutions to discount high credit quality portfolios with REPOs in order to increase liquidity in banks and financial institutions. This new liquidity window, the FCE and the FCD represent together around 10% of Paraguay’s GDP, or USD 3.71 billion.

External financing. Paraguay has benefited from different loans and grants from donors to cope with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of May 2020, Paraguay had USD 2.8 billion available in loans from multilaterals to be executed, most importantly from the IDB and CAF. In March 2020, Paraguay benefited from a USD 300 million loan from the World Bank to foster a more resilient economy and boost rural productivity, and a USD 100 million grant for Proyecto de Inserción a Mercados Agrarios PIMA implemented by the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock to support small and medium-size organised farmers and Indigenous agricultural producers. In April 2020, Paraguay received USD 274 million in IMF emergency financing under the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI).

Investment in infrastructure. Paraguay’s economic recovery plan Ñapu’ã Paraguay included several infrastructure investment projects, most importantly the construction and rehabilitation of roads. In the second half of 2020, total public investment expenditure amounted to USD 1 372 million. In August 2021, the regulatory framework for Paraguay’s Preinvestment Fund (FOREP) was approved. FOREP’s objective is to fund pre-feasibility and feasibility studies for public investment projects by different public institutions.

Transparency during COVID-19. In August 2020, the online platform Ñapua Paraguay was created to increase transparency in the implementation of Paraguay’s economic recovery plan and to promote citizen involvement.

Rebuild fiscal buffers and mobilise additional resources to strengthen the resilience of Paraguay’s financing for development model

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted the importance of strengthening Paraguay’s financing for development model. In the short term, the economic slowdown caused a decrease in public revenues and an increase in government debt to finance emergency measures. While debt levels remain moderate in Paraguay compared to international counterparts, it is nevertheless important to re-establish the macroeconomic stability and discipline that characterised the country in the last decade2 in order to increase the fiscal space to navigate the challenging post-pandemic context and boost investor confidence. Given the increasingly restrictive monetary conditions following the progressive increase in interest rates, fiscal policy is at the core of the recovery. In the medium term, Paraguay faces the challenge of balancing recovery stimulus, while simultaneously preserving fiscal sustainability and protecting the most vulnerable groups from the impact of inflationary pressures. Only a holistic fiscal strategy will allow Paraguay to revert to fiscal discipline without compromising the objectives of the National Development Plan 2030 and the Recovery Plan Ñapu’a Paraguay: strengthening social protection systems, improving credits to firms and entrepreneurs, and increasing investment in jobs, infrastructure and housing.

A comprehensive and gradual fiscal strategy to navigate the challenging post-COVID-19 context

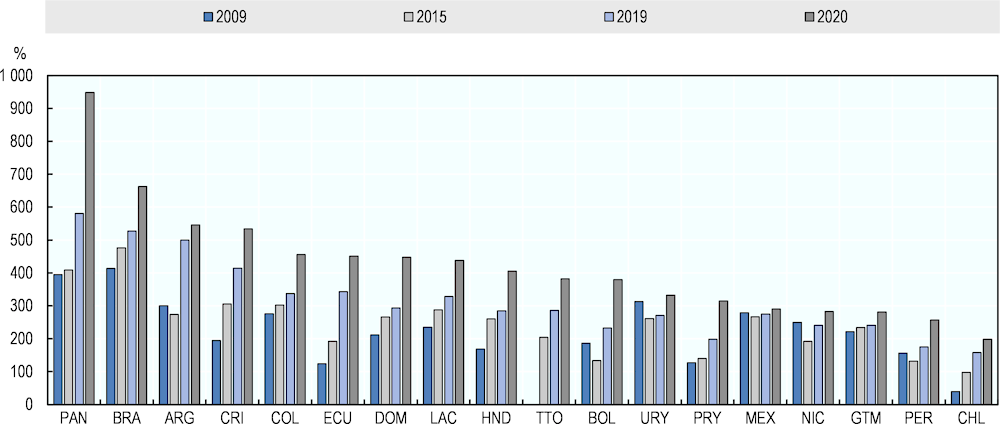

Establishing a clear post-COVID-19 fiscal consolidation path is key to reverting to macroeconomic stability, while preserving public finances from short-term political cycles. While Paraguay’s debt-to-tax ratio, a proxy for debt vulnerability, remains contained with respect to regional peers (Figure 4.6), further increases in public debt could eventually threaten the country’s fiscal sustainability. To make public spending more stable and predictable, the country could benefit from establishing a clear consolidation path to reduce the fiscal deficit in the medium term. In addition, adopting a new Fiscal Responsibility Law (FRL) 2.0 could improve the management of public finances, allowing for greater efficiency and transparency and boosting investor confidence. An adequate escape clause for unforeseen events could also help respond to emergencies without suspending the FRL.

Figure 4.6. Debt vulnerability is moderate in Paraguay but establishing a clear fiscal consolidation path remains key

Debt-to-tax ratio (gross public debt) in selected Latin America and the Caribbean countries.

Source: Panel A. Own elaboration based on OECD et al. (2022[13]), Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2022.

Refocusing expenditures and reducing inefficiencies could make government spending in Paraguay more effective

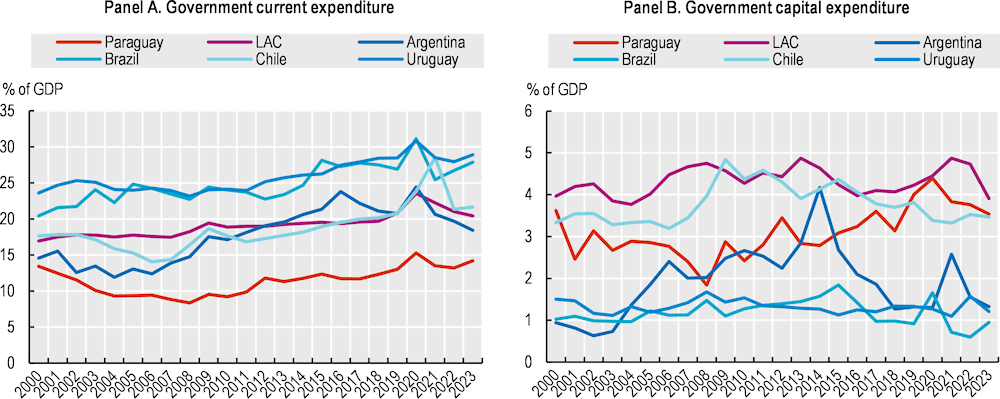

To aid the post-COVID-19 recovery, Paraguay should refocus government spending to provide more targeted support, and shift away from current expenditure towards capital expenditure. Central government current expenditure (e.g. spending on salaries, purchase of goods and services, subsidies and transfers) grew from 13% of GDP in 2019 to 15.3% in 2020, as spending increased in response to the emergency. Nonetheless, it remains much lower than the LAC average for 33 countries of 23.8% (2020) and that of regional peers (Figure 4.7, Panel A). Yet, central government current expenditure on salaries is much higher in Paraguay than in neighbouring countries (7.3% of GDP in 2020 compared to 5.3% in Chile, 5.2% in Uruguay, 4.3% in Brazil and 2.2% in Argentina). Over the last two decades, capital expenditure in Paraguay has been lower than in the LAC region on average, but increased in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising from 4% of GDP in 2019 to 4.4% in 2020, on a par with the LAC average of 4.5% in 2020, and higher than regional peers (Figure 4.7, Panel B). Capital expenditure, especially in infrastructure, is important for a robust recovery, as its multiplier effect on jobs and the economic activity is much higher than that of current expenditure (Nieto-Parra, Orozco and Mora, 2021[14]).

Figure 4.7. Capital expenditure will be important for a robust recovery

Central government expenditure (% of GDP)

Notes: LAC is the average for 33 countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region.

Source: ECLAC (2024[15]), CEPALSTAT (database).

There is also space to increase the efficiency of public spending. The estimated total value lost due to leakages in targeted transfers and inefficiency in spending on public procurement and salaries was equivalent to 3.9% of GDP in 2015/16. Even though number this is below the LAC average of 4.4% of GDP, it remains high, especially given the overall lower government expenditure in Paraguay relative to GDP, as compared to LAC countries on average (Izquierdo, Pessino and Vuletin, 2018[16]).

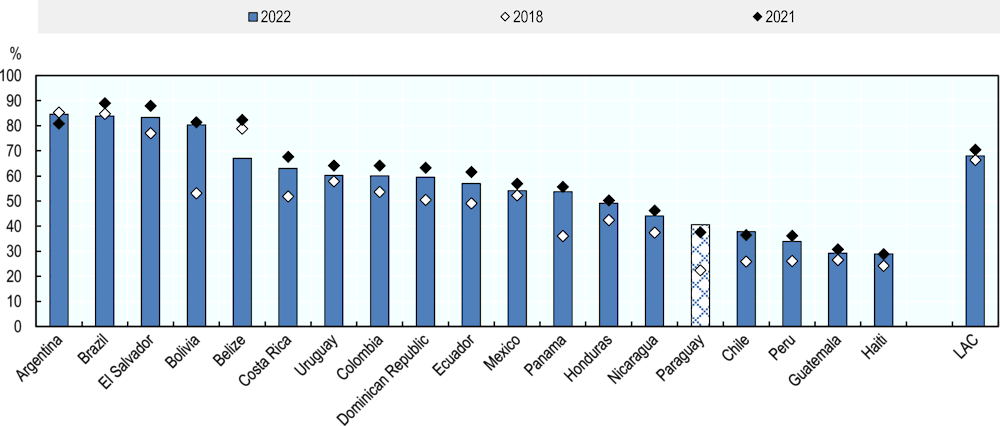

Paraguay’s low tax rates contribute to low levels of government revenues

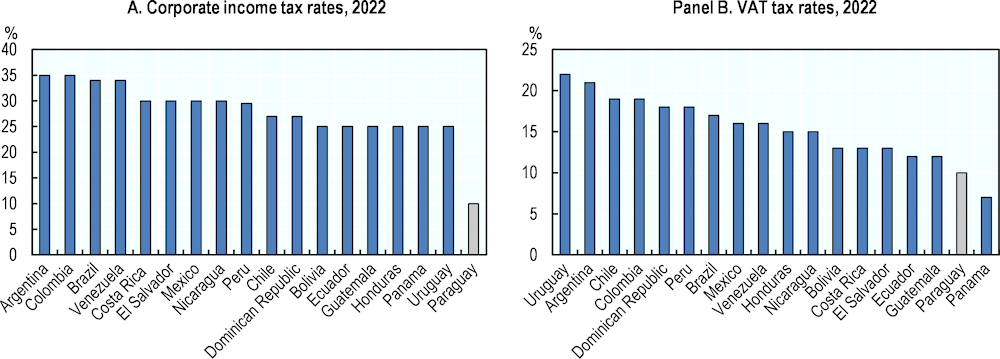

To compensate businesses for high transport costs, Paraguay has traditionally maintained low VAT, income and corporate tax rates. The country’s 10-10-10 tax regime consists of flat 10% personal income tax, 10% corporate tax and 10% VAT tax rates. As a result, Paraguay’s corporate income and VAT tax rates are among the lowest in the LAC region (Figure 4.8). The total tax contributions paid by businesses in Paraguay amount to only 34.9% of commercial profits compared to the LAC and OECD averages of 46.6% and 41.6%, respectively (Figure 4.9). These low tax rates and the regressivity of Paraguay’s tax system as a result of flat rates contribute to high levels of inequality and low levels of government revenues, which constrains spending on public goods. Paraguay’s tax revenues amounted to only 14.7% of GDP in 2022, compared to 21.5% on average in LAC and 34.0% on average in the OECD.

Figure 4.8. Corporate income taxes and VAT tax rates are low in Paraguay

Source: Panel A. PWC (2023[17]), Corporate income tax (CIT) rates, https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/corporate-income-tax-cit-rates; Tax Foundation (2022[18]), Corporate Tax Rates around the World, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/corporate-tax-rates-around-the-world/#:~:text=The%20worldwide%20average%20statutory%20corporate,statutory%20rate%20is%2025.43%20percent; Panel B. Avalara (2022[19]), International VAT and GST rates, www.avalara.com/vatlive/en/vat-rates/international-vat-and-gst-rates.html; Deloitte (2022[20]), Global indirect tax rates, https://www2.deloitte.com/bg/en/pages/tax/solutions/global-indirect-tax-rates.html; PWC (2023[21]), Value-added tax (VAT) rates, https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/value-added-tax-vat-rates.

Figure 4.9. Taxes paid by businesses are low compared to other LAC countries

Taxes paid by companies (% of commercial profits), 2019

While low corporate tax rates affect tax revenue, efforts to increase revenue should consider the balance of the entire tax structure and the tax base in particular. As Figure 4.9 shows, Paraguay stands out among other low-tax jurisdictions due to its low effective tax on profits, despite having similar levels of enterprise taxation as other low-tax jurisdictions. Expansions in the tax base are therefore important to avoid an overreliance on corporate taxation that could blunt investment incentives.

Tax digitalisation, environmentally-related taxes, a better tax structure and a reduction in tax exemptions could help Paraguay raise more tax revenues

Increasing tax revenues could generate more fiscal space and make more resources available for social programmes and investment. In addition to high non-tax income from the binational dams, Paraguay’s low tax revenues are also explained by high levels of tax evasion (VAT evasion is above 30%, equivalent to a loss of around 2.3% of GDP) and low tax rates (Paraguay’s 10-10-10 system has equal tax rates for VAT, corporate tax and personal income tax).

Investment in tax digitalisation backed by strong government support could improve tax collection and reduce tax evasion. Paraguay managed to increase tax revenues only marginally between 2010 and 2019 from 12.1% to 14% of GDP (OECD et al., 2022[13]). Over the same period, tax revenues in Rwanda rose from 12.3% to 17.7% of GDP (OECD, 2022[22]). The Rwanda Revenue Authority (RRA) has benefited from strong government support and has invested heavily in digitalising tax services to expand the tax base. The RRA has prioritised the simplification of tax forms and processes and collaborated with the private sector to create commercially viable delivery models for tax digitalisation. The number of registered taxpayers nearly doubled from 144 000 to 242 000 between 2011 and 2018, following the introduction of e-filing and e-payments. Electronic Billing Machines (EBMs) have also reduced fraudulent VAT claims by 25–35% since their introduction in 2013, and decreased the time it takes businesses to file VAT returns from 45 to 5 hours (Rosengard, 2020[23]). The mandatory adoption of the e-invoice to all groups of taxpayers by 2024 could have similar positive effects in Paraguay.

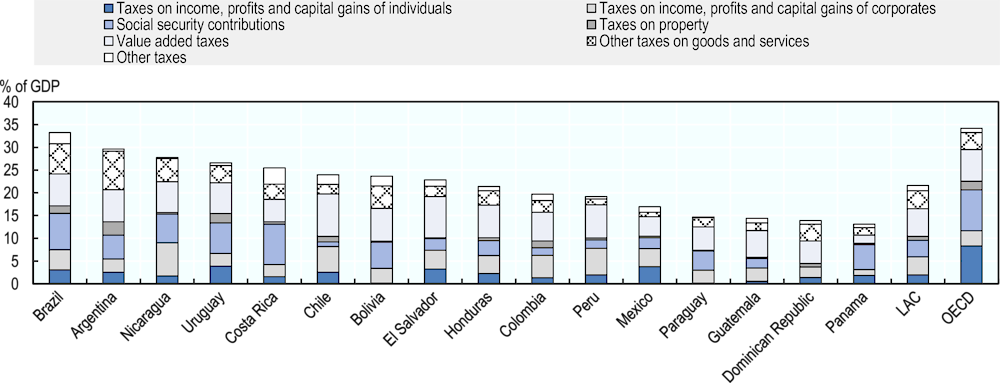

Improving the tax structure could also boost the progressivity and equity of Paraguay’s tax system. High reliance on indirect taxes and flat rates results in a tax system with only a modest impact on income inequality. VAT is the most important source of tax revenues in Paraguay, even though the country’s 10% rate is the lowest in South America. VAT accounted for 35% of total tax revenues in Paraguay in 2022 compared to 28% in the LAC region and 20% in OECD countries. However, VAT revenues accounted for only 5.1% of Paraguay’s GDP compared to 6.1% in LAC countries on average and 7.0% in the OECD (Figure 4.10). Conversely, personal income tax (PIT) only represented 1% of total tax revenues in Paraguay in 2022 compared to 9% in the LAC region and 24% in OECD countries. In addition to generating tax revenues, PIT is typically progressive – imposing steeper rates on those with a higher income – and can play an important role in promoting inclusive growth in Paraguay.

Figure 4.10. Improving tax collection and increasing progressivity are pending issues for Paraguay

Tax structure (% of GDP), 2022

Note: The LAC average represents the unweighted average of 26 LAC countries and excludes Venezuela due to data availability issues. The OECD average is for 2021.

Source: OECD et al. (2024[24]), Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2024.

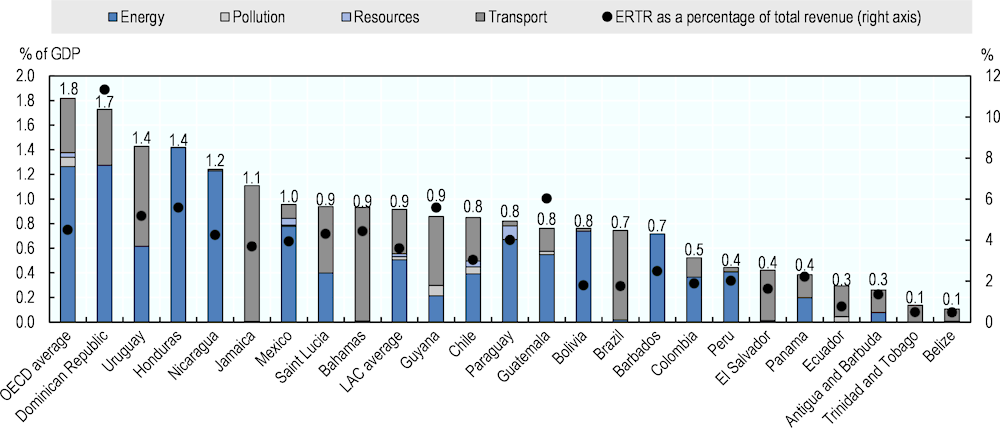

Improving the efficiency of environmentally related taxes can help increase revenues while promoting more effective resource use and advancing towards a more sustainable economy. Environmentally related tax revenues in Paraguay stood at 0.8% of GDP in 2022, slightly below the LAC average of 0.9% and significantly lower than the OECD average of 1.8%. However, Paraguay’s environmentally related tax revenues (ERTR) account for a significant proportion of total revenues, averaging 4%. This figure is close to the OECD average of 4.5% and exceeds the LAC average of 3.6%, as well as those of 14 other countries in the region. Paraguay’s ERTR structure consists primarily of energy-related taxes, in line with many other countries in the region, which rely mostly on energy and transport taxes. However, unlike the rest of the region, Paraguay also levies resource taxes, which include animal health taxes, livestock trade taxes, and taxes on the ownership and slaughtering of animals. In particular, there is potential to improve taxes related to transport, which represented only 0.04% of GDP in 2022, compared to 0.36% in LAC and 0.44% in the OECD (Figure 4.11). All environmentally related taxes should be paired with protection schemes for vulnerable households, including cash transfers, in-kind support, and active labour market policies.

Figure 4.11. Environmentally related tax revenues (ERTR) in LAC countries by main tax base and as a percentage of total revenue, 2022

Note: The LAC average represents the unweighted average of 23 LAC countries and excludes Argentina, Costa Rica, Cuba and Venezuela due to data issues. The figure does not include Jamaica’s revenues from the special consumption tax on petroleum products (estimated to be more than 2.0% of GDP in 2018) (OECD, 2021) as the data are not available. The OECD average represents the unweighted average of 37 OECD member countries excluding Costa Rica.

Source: (OECD et al., 2024[24]), Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2022, and IMF (2024[9]), World Economic Outlook Database 2024.

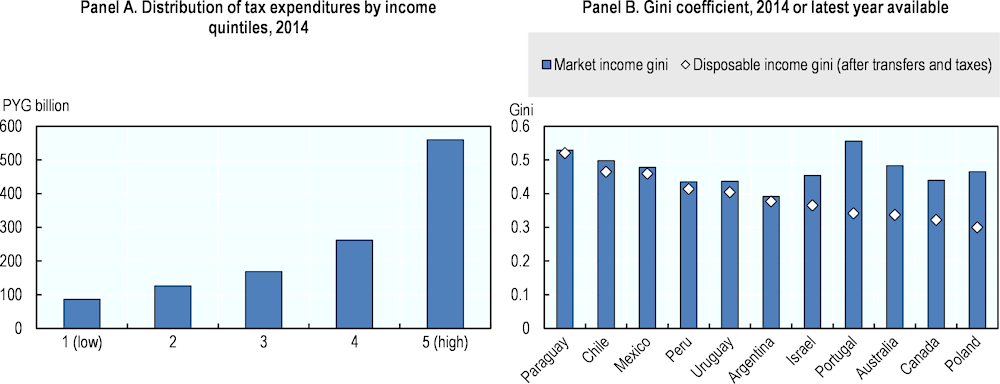

Taking into consideration the existing low tax rates, it is essential to assess the cost and the legitimacy of tax expenditures. In 2014, there were 72 tax expenditure provisions in Paraguay, amounting to an estimated 1.41% of GDP in forgone revenues (Laudage, von Haldenwang and von Schiller, 2022[25]). Although some tax expenditures (e.g. lower VAT for basic consumption goods) are aimed at decreasing the cost of a basic basket of goods and services for the lower-income population, tax expenditures tend to benefit higher-income groups more than lower income groups (Figure 4.12, Panel A). Overall, low tax rates and tax collection efforts, high evasion and tax exemptions result in a fiscal system with only a modest impact on inequality reduction (Figure 4.12, Panel B).

Figure 4.12. A more progressive tax system is key for reducing inequality

Source: Panel A: Own elaboration based on CIAT (2015[26]), Estimación de los Gastos Tributarios en la República del Paraguay 2013-2016; Panel B: OECD (2018[7]) based on IDD database for OECD countries and SEDLAC/Word Bank for Latin American countries.

Mobilising public and private resources towards a green and sustainable recovery

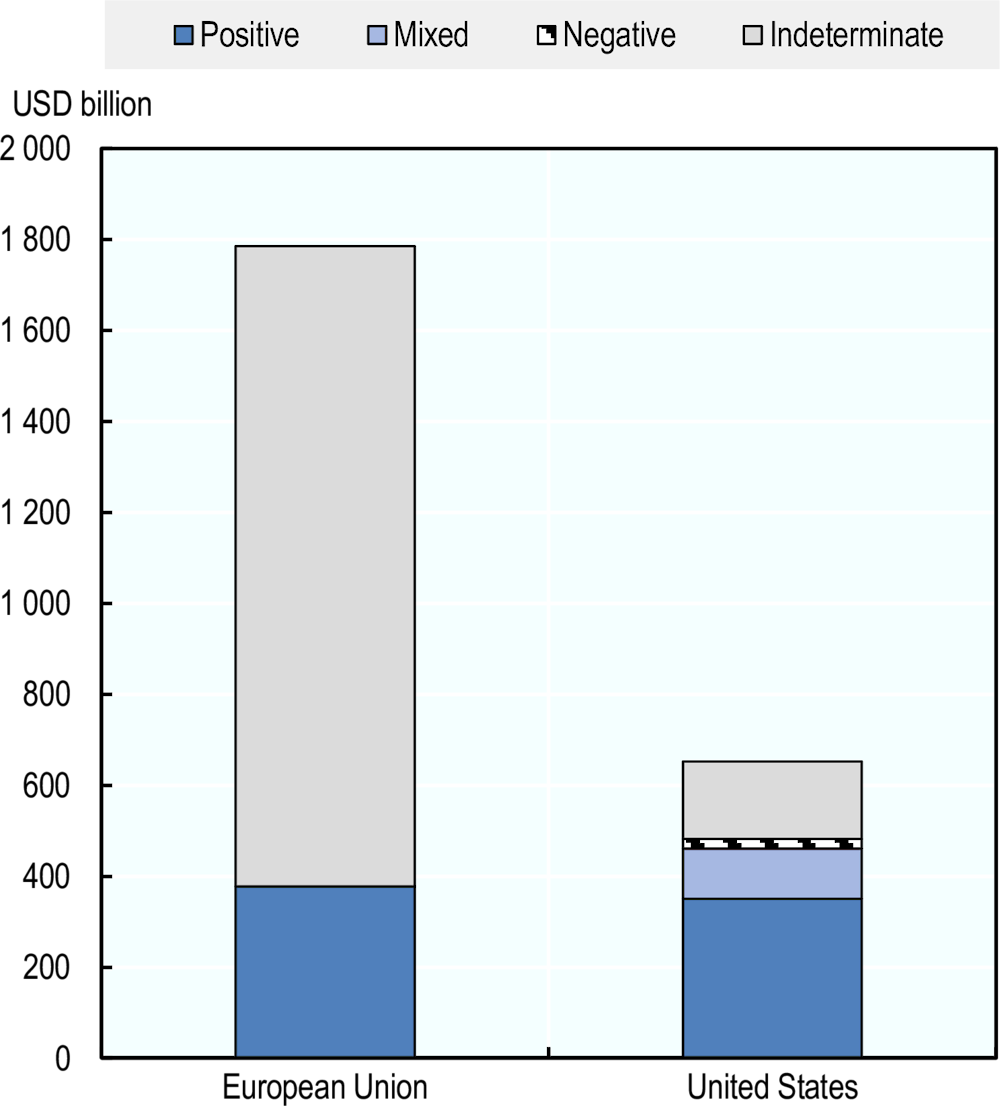

The COVID-19 recovery represents an opportunity for Paraguay to mobilise funding towards a green transition and building back better. OECD member countries, key partner countries and the European Union have already taken advantage of recovery spending to mobilise resources towards the green transition. According to the OECD Green Recovery Database, the share of green spending accounts for 21% of total recovery spending announced since the start of the pandemic, with the majority directed towards the energy and ground transportation sectors (OECD, 2021[27]). The EU Member States’ Recovery and Resilience Plans (or RRPs) were also required to include at least 37% of funding towards climate action (OECD, 2021[27]). Nonetheless, there is also evidence of an increase in measures with mixed and negative effects on the environment and the climate, although these have been outpaced by measures with a positive impact (OECD, 2021[27]).

Figure 4.13. Europe and the United States have announced important green recovery measures

Announced recovery measures by impact on the environment, United States and the European Union.

Source: OECD (2021), Green Recovery Database.

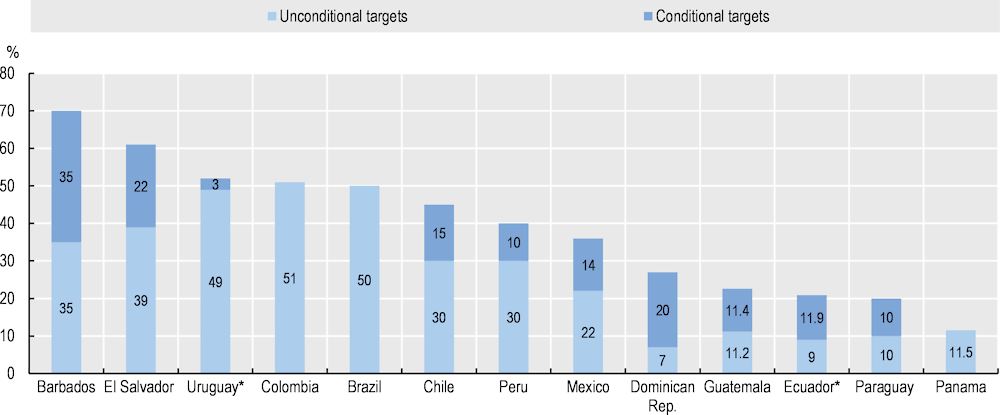

To implement the mitigation and adaptation targets laid out in Paraguay’s NDC, the country will need to promote innovative financial mechanisms. Paraguay’s 2021 updated NDC establishes a 10% unconditional CO2 reduction target by 2030 and an additional 10% conditional target (Figure 4.14). It also presents ambitious adaptation targets for sectors such as water, forestry, agriculture, land use, energy, infrastructure, health and disaster risk management (Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay, 2021[28]). A financing strategy is particularly important since the conditional targets assume that national policies will be implemented only if the required financial sources can be raised and the necessary technology transfers and capacity building take place.

Figure 4.14. For Paraguay and other LAC countries, achieving the more ambitious emission reduction targets depends on external funding

Total GHG emission reduction targets commitments in LAC NDCs by 2030

Note: * Ecuador and Uruguay targets refer to 2025, not 2030. Total GHG emission reduction targets correspond to the sum of unconditional and conditional targets. Argentina and Costa Rica did not officially set a relative target. Antigua and Barbuda did not officially set an economy-wide GHG emission reduction target in its updated NDC.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on countries’ NDCs.

Expanding Paraguay’s market for green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds

New debt instruments such as green, social, sustainable and sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds are increasingly consolidating a capital markets-based approach to sustainable finance. This approach has opened a new flow of finance from the private sector that will be essential for tackling climate change (OECD et al., 2022[29]). As defined by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), there are two types of structures in the sustainability debt market: use of proceeds and target-linked. Green, social and sustainable bonds belong to the first type of structure. They are fixed-income instruments whose proceeds are applied exclusively to finance environmental and social projects or a combination of both (OECD et al., 2022[29]; ICMA, 2022[30]). Conversely, sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are target-linked, and the proceeds are used for general purposes. They differ from GSSS bonds in that they are more easily tracked through the assessment of key performance indicators (KPI) and allow financing outside of specific projects or use of proceeds categories. For SLBs, issuers choose the targets they want to achieve with the bond, making additional payments to bondholders if these targets are not met (OECD et al., 2022[29]; ICMA, 2022[30]).

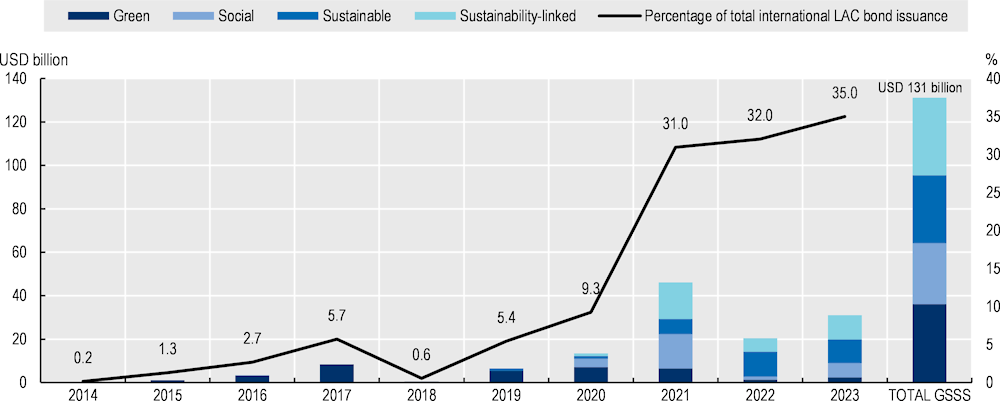

GSSS bond issuance by LAC countries in international markets has increased substantially since 2014 and the types of bonds issued have also diversified. Despite a considerable decrease in total LAC bond issuance in international markets since 2021 (falling from 149 billion in 2021 to 76 billion in October 2023), GSSS bonds continue to be an attractive financing mechanism in the region. Their share increased from 9.3% of total LAC bond issuance in 2020 to almost 35% in 2023. Between 2014 and November 2023, the GSSS international bond market in the LAC region reached a cumulative value of close to USD 128 billion (Figure 4.15) Total green bond issuance almost doubled in the region from USD 18.8 billion in 2019 to USD 36 billion in 2023. Green bonds have dominated sustainable finance throughout the years, but since 2019, other bonds such as sustainable, social and sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) have started to gain momentum with a cumulative issuance of USD 92.5 billion in November 2023 since the inception of this market segment in 2016 (OECD et al., 2023[31]).

Figure 4.15. International bond issuance in the LAC region, GSSS by type and percentage of total issuance, 2014 – November 2023

Note: GSSS refers to green, social, sustainability and sustainability-linked bonds. Total sustainable bonds for 2022 include two blue bonds issued by the Bahamas, and for 2023 one issued by Ecuador and two by the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI).

Source: (OECD et al., 2023[31]), Latin American Economic Outlook 2023: Investing in Sustainable Development and (Núñez, Velloso and Da Silva, 2022[32]), Corporate governance in Latin America and the Caribbean: Using ESG debt instruments to finance sustainable investment projects.

Sovereign GSSS issuance has grown as a share of total sovereign bond issuance in the LAC region. Meanwhile, total sovereign issuance has continued to decline since 2021 due to tightening financial conditions and higher borrowing costs. In Paraguay, total sovereign bond issuance declined from USD 800 million in 2021 to USD 500 million in 2023. Despite these challenges, sovereigns in the LAC region are increasingly opting for GSSS securities. This growth responds in part to the attractiveness of this market for increasing returns on liquid global capital, diversifying the investor base and mobilising direct capital into sustainable activities. In 2022, sovereign GSSS bond issuance in international markets in the region accounted for 35.7% of total sovereign issuance of all types of bonds in international markets. As of November 2023, this figure increased to 58%. In 2023, sovereigns led with a 73% share of total GSSS bond issuance in the LAC region, followed by corporates (18%) and supranational and quasi‑sovereign issuers (9%) (ECLAC, 2023[33]; OECD et al., 2023[31]).

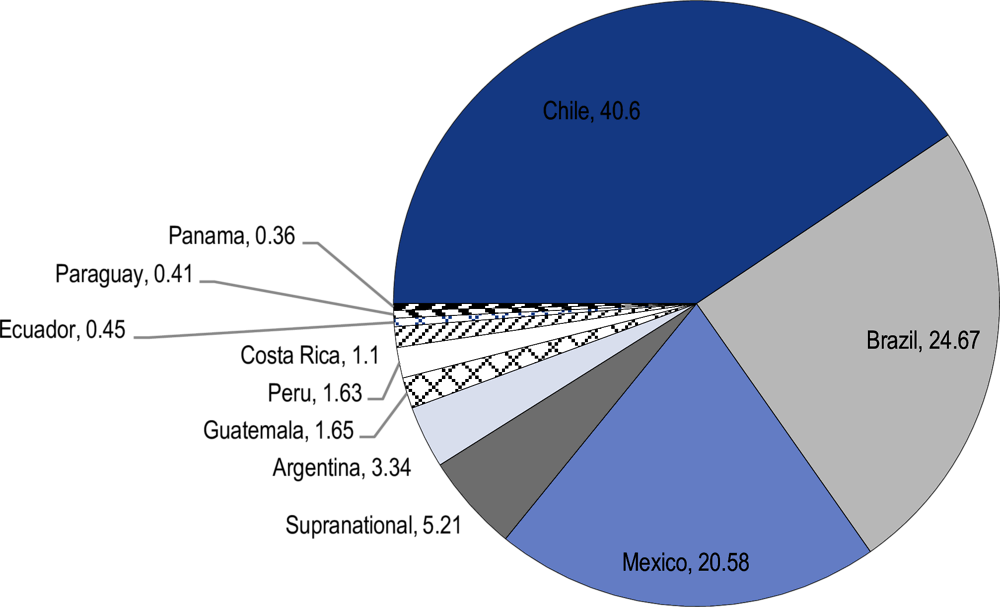

Paraguay still lags behind other LAC countries in cumulative issuance of GSSS bonds in international markets. Among LAC countries, Brazil, Chile and Mexico have taken the lead in GSSS bond issuance in international markets at 40.6%, 24.6%, and 20.5% respectively (Figure 4.16). Lagging behind on GSSS bond issuance are Argentina (3.34%), Guatemala (1.65%), Peru (1.63%), Costa Rica (1.1%) Ecuador (0.45%), Paraguay (0.41%) and Panama (0.36%). Paraguay’s only issuer prior to 2023 was the private bank Banco Continental of Paraguay. In December 2020, following the adoption of a resolution incorporating SDG bonds into Paraguay’s legal framework, Banco Continental of Paraguay issued its first sustainable bond worth USD 300 million for a term of five years to finance green and social projects (Banco Continental, 2022[34]). In December 2023, Paraguay’s public development bank, AFD, issued a PYG 100 000 million (about USD 13 million) sustainable bond in the local market.

Figure 4.16. LAC GSSS bond issuance in international markets has been dominated by Chile, Brazil and Mexico

LAC GSSS bond issuance in international markets by country (%), December 2014 – September 2021

Note: Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are notable among the category of GSSS assets, particularly for providing issuers with the opportunity to redirect capital flows to achieve multiple sustainable objectives simultaneously, while also offering the possibility of obtaining coupon discount rewards. Moving forward, innovative approaches to SLBs can offer sovereign issuers the opportunity to fulfil national government commitments under their NDCs and the Paris Agreement, while also helping to promote the long-term sustainability of their sovereign debt. These instruments have the potential to bolster domestic revenue mobilisation, enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of expenditure, and align investments with the priorities of national sustainable development. However, it is essential to evaluate the key benefits, challenges and advantages associated with the development of these instruments and other sustainable finance instruments (Box 4.2).

The success of the sustainable bond issued by the Banco Continental has been moderate. Banco Continental of Paraguay issued USD 300 million in sustainable bonds, verified by third-party Sustainalytics. Eligible projects include green initiatives such as energy efficiency, clean transportation and sustainable resource use, along with social projects focusing on basic infrastructure, service access and employment. Financing or refinancing is available for projects disbursed by Banco Continental within 36 months before the bond issue until maturity. Notably, both new projects and those funded by Banco Continental before the bond issuance are eligible, meaning additionality is not guaranteed. Moreover, as of 2021, only 33.8% of the funds raised – USD 101.3 million – were allocated to green and social projects. To expedite fund placement, Banco Continental introduced new sustainable products, including Eco-Loans for biofueled machinery, sustainable construction, hybrid/electric vehicles and Social Infrastructure Loans (Banco Continental, 2020[35]; Banco Continental, 2022[34]).

Paraguay’s mid-sized economy has a unique opportunity to issue its inaugural sovereign GSSS bond in the international market. With a focus on sustainable agricultural production and major products like soybeans and sugarcane, the country could benefit from the issuance of these thematic bonds. Some countries in the region have already set a precedent, for example, by earmarking the proceeds from sustainable bonds for sustainable agriculture projects. In 2023, Brazil issued its first sustainable bond, raising USD 2 billion for various projects, including initiatives for sustainable agriculture and smart farming. The aim is to enhance food security and promote sustainable food systems by promoting agro-ecological food production in urban and semi-urban areas, as well as purchasing and distributing food to vulnerable populations (Climate Bonds Iniative, 2023[36]). Expanding and consolidating Paraguay’s GSSS bond issuance in international markets would also have several advantages. Firstly, expanding this market is a key opportunity to encourage the greater participation of supranational, institutional and private sector investors in its debt market. Secondly, it could also enable more resources to be channelled towards sustainable investments.

Box 4.2. Policy workshop on sustainable finance

As part of the project “A New Sustainable Development Model for the Post-Covid Era in Panama and Paraguay”, the OECD Development Centre organised an international workshop entitled “Financing Sustainable Futures: The Role of GSSS Bonds in Mobilising Public and Private Capital Towards a New Model of Development”, in collaboration with the governments of Panama and Paraguay. The workshop was held online on 18 October 2023. It aimed to facilitate regional-level exchange on the benefits and opportunities of sustainable finance and foster constructive dialogue on practical tools to drive the issuance of GSSS bonds in both countries. Essential topics, such as the structuring of these types of bonds, eligibility criteria tailored to each country’s priority areas and the need for enhanced co‑operation, were addressed. The discussions brought forth perspectives from a variety of stakeholders, including representatives from international organisations, the public sector and development banks.

The workshop discussion revealed crucial insights for “greening” the financial system, exposing the main challenges involved in promoting the development of new sustainable products, and emphasising the need to enhance regulatory and institutional frameworks:

To develop bankable, investment-ready projects, collaboration between ministries and the office for public investment is key for project feasibility planning. Even if taxonomies are developed or investment appetite is consolidated, prioritising project planning is essential to direct resources. Advancing in the development of data and metrics is also necessary to accurately identify projects and their needs.

Strong overarching institutional frameworks need to be developed around sustainable finance strategies to keep regulations, metrics and a data repository updated due to the dynamic and evolving environment in which they operate.

Establishing a consolidated national strategy on sustainable finance requires the participation of all stakeholders, including institutional investors and insurers. Developing a common language among both bank and non-bank financial stakeholders and international peers is essential for advancing this strategy.

When developing a common language, it is crucial to establish green or sustainable taxonomies and economic, social and governance (ESG) standards that accurately reflect the sectoral priorities and vulnerabilities of the country. This is essential to clearly define the rules for investors.

Regional standardisation and harmonisation of sustainable finance frameworks are key to improving interoperability with global taxonomies and standards and reducing transaction costs for interested investors, while also fostering participatory processes and collaborative work across financial stakeholders.

More consolidated sustainable finance frameworks are essential for building trust and transparency. A clear legal and regulatory framework lends credibility and instils trust, thereby boosting foreign investment. Developing tracking, monitoring and verification systems to oversee all types of sustainable instruments is fundamental to preventing green/SDG-washing.

The issuance of sustainable bonds and SLBs offers issuers the opportunity to encompass a wider range of projects and attract a more diversified investor base.

Fostering sustainable instruments that drive the development of the local capital market is crucial. It is important to invest in technical and technological capacities that can measure the impact of financing from debt instruments in the local market. Doing so can facilitate the establishment of local governance and investment culture mechanisms.

Source: International experience-sharing workshop of the OECD Development Centre, co-organised with the governments of Panama and Paraguay.

Further development of Paraguay’s sustainable finance framework will be necessary to enable and scale up investment where needs are greatest

At present, Paraguay’s national sustainable finance framework consists of a series of guidelines and laws developed by different stakeholders. The Sustainable Finance Board of Paraguay (Mesa de Finanzas Sostenibles, MFS) has published several guidelines including the Environmental and Social Guide for the Sustainable Financing of Livestock (2016), the Environmental and Social Guide for Financing Agricultural Activities (2017), and the Environmental and Social Guide for Financing Agro-Industrial Activities (2018). In 2018, the Central Bank of Paraguay released the Guidelines for the Management of Environmental and Social Risks for Entities Regulated and Supervised by the Central Bank of Paraguay (SBFN/IFC, 2021[37]). Finally, in 2020, Paraguay’s National Securities Commission (Comisión Nacional de Valores, CNV) published a set of Guidelines for the Emission of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Bonds (SBFN/IFC, 2021[37]; CNV, 2020[38]). Going forward, it will be important to enforce and harmonise these guidelines across banks and other financial sector stakeholders and to ensure that they reflect international best practices.

Paraguay was the first country in Latin America to adopt SDG bonds as part of national legislation. In March 2020, Paraguay’s National Securities Commission issued a resolution (Resolution No. 9/20), which incorporates SDG bonds into Paraguay’s existing capital market legislation. SDG bonds are defined as debt instruments that finance or refinance projects with green, social or sustainable goals in line with the United Nations 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. The proceeds from issuing SDG bonds must be used exclusively for financing social, green and sustainable projects. These type of bonds must comply with the general regulations and conditions for bonds applicable in Paraguay, be reviewed and validated by an independent third party accredited by the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), and are subject to periodic public reporting on their impact (SBFN/IFC, 2022[39]; CNV, 2020[38]; UNDP, 2021[40]).

A national green or transition taxonomy for all bank and non-bank financial institutions and stakeholders is an essential part of a sustainable finance framework for Paraguay. Taxonomies consist of a set of criteria to identify whether and to what extent an asset, economic activity, project or investment contributes to the fulfilment of environmental objectives prioritised by a country or region (Gobierno de Colombia, 2022[41]). They function as important tools for mobilising financial resources to achieve sustainability goals, helping financial market participants to assess or categorise their activities or assets according to their contribution to sustainability goals. Taxonomies also help mitigate the risk of “greenwashing” – classifying a project as sustainable when in practice the project does not meet sustainability criteria (OECD et al., 2022[29]). However, although Paraguay’s Resolution No. 9/20 includes a set of criteria for SDG bonds, the country still lacks a comprehensive sustainable or green taxonomy such as the one issued by Colombia in 2022 (Box 4.3). When developing a national green or sustainable taxonomy, it is important that Paraguay harmonise this taxonomy with other countries in the region to create an integrated market and enhance transparency. To achieve this, the guidance offered by the regional Common Framework of Sustainable Finance Taxonomies, released in June 2023 by the UN system, will be crucial for the country to align its national framework with that of others in the region. This could allow for greater mobilisation of capital aligned with the country’s environmental goals.

Box 4.3. Colombia’s green taxonomy

Colombia’s green taxonomy, published in April 2022, is a good example of a classification system that facilitates the identification of projects with environmental objectives, develops capital markets for GSSS finance, and promotes the effective mobilisation of private and public resources for sustainable development (Gobierno de Colombia, 2022[41]). Table 4.1 provides guidelines for designing a comprehensive green taxonomy based on the Colombian case.

Table 4.1. A step-by-step guide to building a dynamic and comprehensive green taxonomy based on Colombia’s model

|

Step |

Details |

|---|---|

|

1. Define clear environmental objectives according to key economic sectors (the definition should be based on environmental priorities). |

Possible environmental priorities: climate change mitigation and adaptation, natural resource conservation, biodiversity conservation, pollution prevention and control, etc. |

|

2. Develop a set of eligibility criteria and compliance requirements. |

Establish a set of guidelines and requirements assessing whether the environmental performance of an asset or economic activity meets the expected environmental objective. |

|

3. Assess the taxonomy’s alignment with the regulatory and policy framework. |

|

|

4. Harmonise the national taxonomy with taxonomies at the regional and international level. |

Incorporate best practices from international and regional environmental sustainability systems into the taxonomy (e.g. the European Union’s Taxonomy of Sustainable Finance, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the Green Bond Principles and the SDGs). |

|

5. Consider the interrelationships between environmental, economic and social goals. |

|

|

6. Identify the potential users of the taxonomy and how it will be used by them. |

|

|

7. Develop mechanisms to monitor and evaluate the use of the taxonomy by financial market participants. |

The Financial Superintendency of Colombia, for example, issued different rules that reference the Green Taxonomy with the purpose of increasing the transparency of capital markets and minimising the risk of greenwashing in: (i) the issuance of green bonds, (ii) the denomination of voluntary pension fund portfolios, and (iii) the disclosure of social and environmental information. |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Gobierno de Colombia, 2022[41]), Taxonomía verde de Colombia.

The design of a green or sustainable taxonomy for Paraguay should be an inclusive process to ensure that guidelines and standards are clear for all. Relevant stakeholders who should participate in the process include private companies, financial institutions, the national stock exchange and other financial market stakeholders (e.g. pension funds, capital market investors and asset managers) as well as relevant public sector stakeholders (SBFN/IFC, 2021[37]; OECD et al., 2022[29]).

Beyond bonds and consolidating the national sustainable framework, other fundamental regulatory tools to promote sustainable financing include the 2013 Law on Environmental Services Certificates and the 2023 Carbon Credits Law. Environmental services certificates issued under the 2013 law provide legal certainty to business activities, reassurance to consumers and serve the entire value chain of corporate sustainability as a roadmap for continuing to implement new sustainable guidance measures in the future. Looking ahead, it will be important to continue working on the typologies of these services and to overcome any barriers to the acquisition of these certificates by key production sectors. For instance, the certificates would benefit sustainable soybean production by facilitating access to premium international markets. The National Forest Cover Report (2023) produced by the National Forestry Institute enables the precise identification of sustainable production areas and has verified the accuracy of forest coverage across the entire territory, including areas of soybean production that are 100% free from deforestation. More recently, the 2023 Carbon Credits Law aims to establish a legal framework for carbon credit transactions, with the goal of ensuring security and trust for foreign investment. This legislation has exerted a positive influence on the market, attracting investment funds interested in investing in forestry, energy, mobility and other projects under the Paraguay’s carbon law framework.

Paraguay has made significant progress according to the methodology developed by the Sustainable Banking and Finance Network (SBFN) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group for assessing developing countries’ progress on sustainable finance frameworks. This methodology consists of three pillars: i) ESG integration refers to “the management of ESG risks in the governance, operations, lending and investment activities of financial institutions”; ii) climate risk management relates to “new governance, risk management and disclosure practices that financial institutions can use to mitigate and adapt to climate change”; and iii) sustainability of finance concerns initiatives put in place by “regulators and financial institutions to free up capital flows for activities that support climate, green economy and social goals” (SBFN/IFC, 2021[37]; OECD et al., 2022[29]). Paraguay has shown significant progress in all three pillars and is currently amid the “implementation” stage of the overall SBFN Progression Matrix.

Using innovative financing tools to enhance the local market

To further enhance the use of sustainable finance instruments, the government could develop innovative approaches. Such approaches include issuing GSSS bonds in local currency or promoting digital and technological advances. In 2021, Colombia became the first emerging economy to issue a sovereign green bond in local currency in its domestic market (TES Verdes). Through co-operation between the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit, the National Planning Department and other public‑sector entities, and with the technical support of the World Bank and the IDB, Colombia was able to develop its first portfolio of eligible green expenditures. This portfolio amounted to COP 2.3 billion (Colombian peso) distributed across 27 projects and 8 categories: i) non-conventional energy sources, energy efficiency and connectivity; ii) ecosystem services and biodiversity; iii) sustainable, low-emission agricultural production adapted to climate change; iv) clean and sustainable transportation; v) water management, sustainable use and sanitation; vi) environmentally sustainable construction adapted to climate change; vii) waste and the circular economy; and viii) natural disaster risk management associated with climate change (OECD et al., 2022[29]; Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 2022[42]).

In December 2023, the AFD issued its first SDG bond in the local market, totalling PYG 100 billion. This marks Paraguay’s inaugural issuance of sustainable bonds locally, with the AFD the first public institution to undertake such an initiative. Bond proceeds will be used to finance projects in sustainable management of natural resources and land, energy efficiency, renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, access to basic social services, support to MSMEs, and social programmes to alleviate and mitigate unemployment. The issuance was conducted under the AFD’s Sustainable Bonds Framework and represents the first SDG Bond Programme registered with the Securities Superintendence of the Central Bank of Paraguay (AFD, 2023[43]). The AFD’s objective is not only to raise funds, but also to act as a market-maker and stimulate Paraguay’s rather shallow capital markets. Notably, the local market has shown significant appetite for the AFD’s bonds, underscoring the importance of such initiatives in promoting local market development, advancing governance and nurturing an investment culture. A key challenge will be to develop the technical and technological capacities required to measure the financing impact of these type of sustainable instruments in the local market.

Tapping into multilateral financial resources

Tapping into multilateral financial resources via climate funds constitutes an important opportunity for Paraguay to raise sufficient funding to achieve its climate mitigation and adaptation goals. Multilateral climate funds deliver support through funding provided mainly by developed countries for purposes such as adaptation, mitigation, reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and capacity building (OECD et al., 2022[29]). These funds are one means by which developed countries are distributing climate finance in accordance with their commitments made at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen. At the conference, developed countries pledged to “jointly mobilise USD 100 billion a year to help developing countries tackle climate change [by 2020]” (OECD et al., 2022[29]). The Green Climate Fund accounts for the highest amount of resources directed to the LAC region (USD 538.5 million), followed by other funds such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF) trust fund, the Global Green Growth Institute and the Clean Technology Fund (CTF) under the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) framework (OECD et al., 2022[29]).

At present, Paraguay has received USD 146.4 million in financing through the Green Climate Fund (GCF) for six projects. The projects include three multi-country initiatives. Two of these projects aim at strengthening e-mobility in multiple countries in the LAC region, including Paraguay, and are implemented by the IDB. A third project implemented in several LAC and sub-Saharan African countries by MUFG Bank focuses on sustainable forestry. Three further country projects are implemented only in Paraguay. These are a project addressing deforestation, forest degradation, enhancement of forest stocks and conservation (REDD+), implemented by UNEP; an IDB project to promote energy efficiency by SMEs in the industrial sector; and a FAO project to promote forest planting and reforestation in Eastern Paraguay. At present, all projects are under implementation. Four of the projects have a strong emphasis on mitigation and two include cross-cutting measures for both mitigation and adaptation. A further five projects in Paraguay are receiving Readiness Support worth USD 1.4 million from the GCF. The GCF’s Readiness Support supports country-driven initiatives in developing countries by strengthening the capacities of their national institutions, their governance, and their planning and programming frameworks for the climate agenda, through providing grants and technical assistance to national institutions and focal points (GCF, 2022[44]). Looking ahead, Paraguay could better leverage the GFC’s resources by applying for funding for additional projects, implemented not only by international donors but also by national institutions.

References

[43] AFD (2023), Marco de Bonos Sostenibles, Agencia Financiera de Desarrollo, Asunción, https://www.afd.gov.py/archivos/transparencia/emisiones-de-bonos/Bonos_Sostenibles/01%20-%20Marco%20Bonos%20Sostenibles.pdf.

[19] Avalara (2022), International VAT and GST rates, https://www.avalara.com/vatlive/en/vat-rates/international-vat-and-gst-rates.html.

[34] Banco Continental (2022), Informe de Bonos Sostenibles Reporte de Seguimiento, https://www.bancontinental.com.py/api/uploads/REPORTE_DE_GESTION_BONOS_SOSTENIBLES_2021_ESPANOL_779ad58971.pdf.

[35] Banco Continental (2020), Sustainability Bond Framework, https://www.bancontinental.com.py/api/uploads/Banco_Continental_Sustainability_Bond_Framework_November2020_de0cfed238.pdf.

[26] CIAT (2015), Estimación de los Gastos Tributarios en la República del Paraguay 2013-2016, Agencia Alemana de Cooperación Internacional (GIZ), Centro Interamericano de Administraciones Tributarias (CIAT), Subsecretaría de Estado de Tributación (SET), https://www.ciat.org/Biblioteca/Estudios/2015_estimacion_gasto_tributario_paraguay_giz_set_ciat.pdf.

[36] Climate Bonds Iniative (2023), Brazil becomes 50th country to crack the sovereign GSS+ market, Climate Bonds Initiative, England, https://www.climatebonds.net/2023/12/brazil-becomes-50th-country-crack-sovereign-gss-market.

[38] CNV (2020), Resolución CNV CG No.9/20, Comisión Nacional de Valores, Asunción, Paraguay, https://www.cnv.gov.py/normativas/resoluciones/res_cnv-09-CG-20.pdf.

[11] Congreso Nacional de Paraguay (2021), Ley Nº 6809 que Establece medidas transitorias de consolidación económica y de contención social, para mitigar el impacto de la pandemia del COVID-19 o coronavirus, Biblioteca y Archivo Central del Congreso Nacional, Asunción, https://www.bacn.gov.py/leyes-paraguayas/9663/ley-n-6809-establece-medidas-transitorias-de-consolidacion-economica-y-de-contencion-social-para-mitigar-el-impacto-de-la-pandemia-del-covid-19-o-coronavirus#:~:text=Ley%20N%C2%BA%206809%20%2F%20ESTABLECE%20ME.

[20] Deloitte (2022), Global indirect tax rates, https://www2.deloitte.com/bg/en/pages/tax/solutions/global-indirect-tax-rates.html.

[15] ECLAC (2024), CEPALSTAT (database), UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, https://statistics.cepal.org (accessed on 1 June 2024).

[33] ECLAC (2023), Capital Flows to Latin America and the Caribbean: 2022 year-in-review and early 2023 developments, United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, http://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/news/files/kflows2023final_web.pdf.

[6] FitchRatings (2022), Paraguay’s Severe Drought Weakens 2022 Growth Prospects, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/paraguays-severe-drought-weakens-2022-growth-prospects-10-05-2022.

[44] GCF (2022), “Paraguay”, Green Climate Fund, https://www.greenclimate.fund/countries/paraguay.

[41] Gobierno de Colombia (2022), Taxonomía verde de Colombia, https://incp.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Taxonomia-Verde-de-Colombia.pdf.

[28] Gobierno Nacional de Paraguay (2021), Actualización de la NDC de la República del Paraguay, Asunción, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Actualizaci%C3%B3n-NDC%20VF%20PAG.%20WEB_MADES%20Mayo%202022.pdf.

[30] ICMA (2022), Guidance Handbook January 2022, International Capital Market Association, Zürich, Switzerland, https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/GreenSocialSustainabilityDb/The-GBP-Guidance-Handbook-January-2022.pdf.

[9] IMF (2024), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April (accessed on 3 May 2024).

[12] IMF (2023), “First Review under the Policy Coordination Instrument and Request for Modification of Targets”, IMF Country Report, No. 23/207, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

[3] IMF (2023), “IMF Datamapper”, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

[16] Izquierdo, A., C. Pessino and G. Vuletin (eds.) (2018), Mejor Gasto para Mejores Vidas: Cómo América Latina y el Caribe puede hacer más con menos, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC.

[25] Laudage, S., C. von Haldenwang and A. von Schiller (2022), Global Tax Expenditures Database, Council on Economic Policies (CEP) and German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS), https://gted.net/.

[10] MH (2022), Paraguay ante la Pandemia, Vol 4. - Cierre del Fondo, Ministerio de Hacienda, https://www.hacienda.gov.py/web-presupuesto/archivo.php?a=d8d8dbe1ece5ebe6eaa6dae6ede0dba6e7d8e9d8deecd8f097d8e5ebdc97e3d897e7d8e5dbdce4e0d8d6ede6e397ab97eda9a5e7dbddd8077&x=8686025&y=12120b0.

[42] Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público (2022), Marco Fiscal del Mediano Plazo 2022, Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público, Bogota, https://www.minhacienda.gov.co/webcenter/ShowProperty?nodeId=%2FConexionContent%2FWCC_CLUSTER-197963%2F%2FidcPrimaryFile&revision=latestreleased.

[14] Nieto-Parra, S., R. Orozco and S. Mora (2021), La política fiscal para impulsar la recuperación en América Latina: el «cuándo» y el «cómo» son claves, Foco Económico, https://dev.focoeconomico.org/2021/06/23/la-politica-fiscal-para-impulsar-la-recuperacion-en-america-latina-el-cuando-y-el-como-son-claves/.

[32] Núñez, G., H. Velloso and F. Da Silva (2022), Corporate governance in Latin America and the Caribbean: Using ESG debt instruments to finance sustainable investment projects, UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/47778.

[22] OECD (2022), Global Revenue Statistics Database, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=RS_GBL.

[27] OECD (2021), Key findings from the update of the OECD Green Recovery Database, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/key-findings-from-the-update-of-the-oecd-green-recovery-database-55b8abba/.

[7] OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Paraguay: Volume I. Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301900-en.

[5] OECD (2017), Green Growth Indicators, https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/green-growth-indicators/ (accessed on August 2019).

[29] OECD et al. (2022), Latin American Economic Outlook 2022: Towards a Green and Just Transition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d5554fc-en.

[13] OECD et al. (2022), Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/58a2dc35-en-es.

[24] OECD et al. (2024), Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2024, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/33e226ae-en.

[31] OECD et al. (2023), Latin American Economic Outlook 2023: Investing in Sustainable Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d5554fc-en.

[17] PWC (2023), Corporate income tax (CIT) rates, https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/corporate-income-tax-cit-rates.

[21] PWC (2023), Value-added tax (VAT) rates, https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/value-added-tax-vat-rates.

[23] Rosengard, J. (2020), Tax Digitalization in Rwanda: Success Factors and Pathways Forward, Better Than Cash Alliance, https://www.betterthancash.org/explore-resources/tax-digitalization-in-rwanda-success-factors-and-pathways-forward.

[39] SBFN/IFC (2022), Paraguay, Country Progress Report, April 2022, SBFN/IFC, Washington D.C., https://sbfnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/2021_Global_Progress_Report_Downloads/2021_Country_Progress_Report_Paraguay.pdf.

[37] SBFN/IFC (2021), Accelerating Sustainable Finance Together: Global Progress Report of the Sustainable Banking and Finance Framework, Sustainable Banking and Finance Network/International Finance Corporation, New York/Washington, DC, https://sbfnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/2021_Global_Progress_Report_Downloads/SBFN_D003_GLOBAL_Progress_Report_29_Oct_2021-03_HR.pdf.

[18] Tax Foundation (2022), Corporate Tax Rates around the World, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/corporate-tax-rates-around-the-world/#:~:text=The%20worldwide%20average%20statutory%20corporate,statutory%20rate%20is%2025.43%20percent.

[40] UNDP (2021), Paraguay first to adopt SDG bonds in its national regulation, https://www.undp.org/blog/paraguay-first-adopt-sdg-bonds-its-national-regulation.

[4] UNFCCC (2023), “Profiles of Non-Annex I countries”, UNFCCC, https://di.unfccc.int/ghg_profile_non_annex1 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

[1] WHO (2023), WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, World Health Organization, https://covid19.who.int/data (accessed on 26 July 2023).

[2] World Bank (2024), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators# (accessed on 1 June 2024).

[8] World Bank (2022), Paraguay Overview, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/paraguay/overview.

Notes

← 1. https://www.ip.gov.py/ip/diputados-sanciona-ley-de-consolidacion-economica-y-contencion-social/.

← 2. The institutionalisation and professionalisation of the Central Bank of Paraguay and the Ministry of Finance (MH), together with an inflation-targeting regime with an explicit target since 2011, a sound fiscal framework and a fiscal responsibility law passed in 2013, have contributed to macroeconomic stability in recent years.