The direct economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was muted in Paraguay compared to other countries in the region. However, the pandemic was bookended by two severe droughts that have challenged the economic recovery. Diversifying the economy is critical to enhance growth and resilience to climate change. It is also a major challenge in a context of high informality in a landlocked country. This chapter examines how measures established during the crisis and recovery period can support the country in tackling structural challenges. Credit support measures can support a formalisation effort that will have to be broader and combine ongoing administrative simplification efforts with support to increase the productivity of MSMEs and foster integration in regional and global value chains.

A Multi-dimensional Approach to the Post-COVID-19 World for Paraguay

3. A strong recovery: Economic growth and business dynamics

Abstract

Box 3.1. Main findings and assessment

Benchmark data

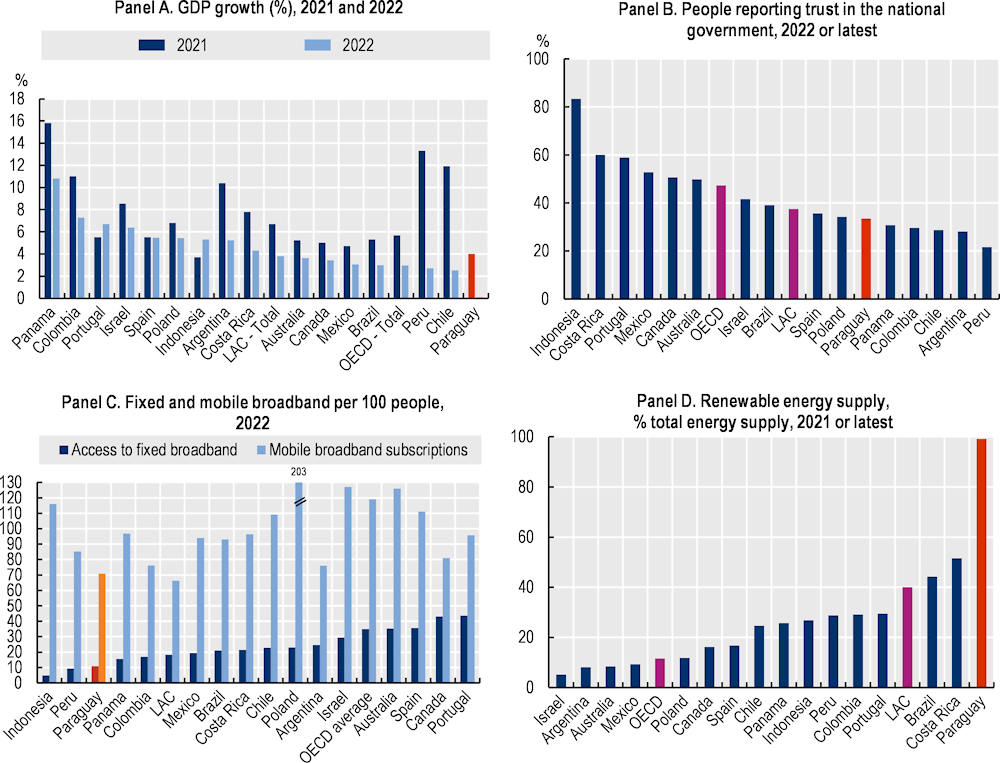

Paraguay’s GDP decreased only slightly in 2020 (-0.8%), while the GDP of all other countries, including OECD member countries, dropped by several percentage points (-4.9% on average). After a muted recovery, growth fell again to 0.1% in 2022 before recovering (4.7%) in 2023

The share of Paraguayan citizens with confidence in the national government was 33.6% in 2022. This value is relatively low compared to the OECD average of 47.4%. Improving governance, integrity and transparency within public institutions are pending challenges in Paraguay that affect citizens’ trust in government as well as the business environment.

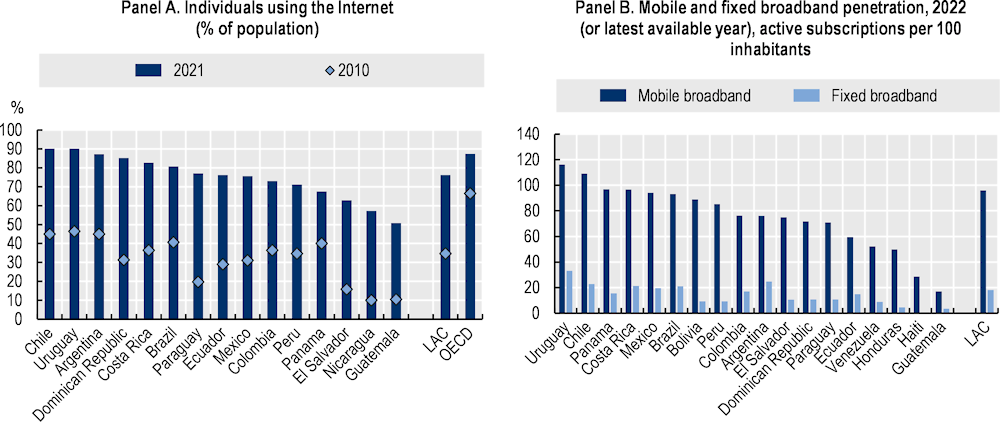

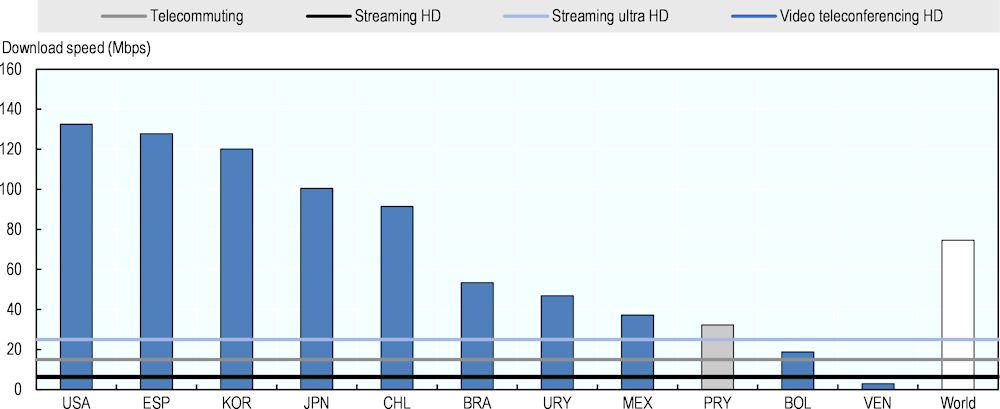

Paraguay (10.9%) lags behind in fixed broadband coverage by a wide margin with respect to the average for OECD countries (34.9%). Mobile broadband fills part of this gap (71 active subscriptions per 100 population). Broadband speed is also an important factor, in addition to accessibility. In 2022, Paraguay ranked 59th for fixed network speeds (57.89 mbps) among countries and 114th for mobile speeds (15.19 mbps).

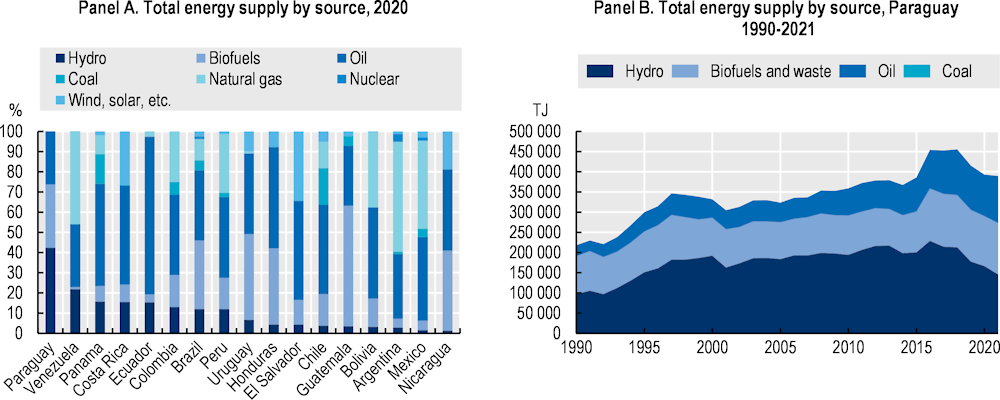

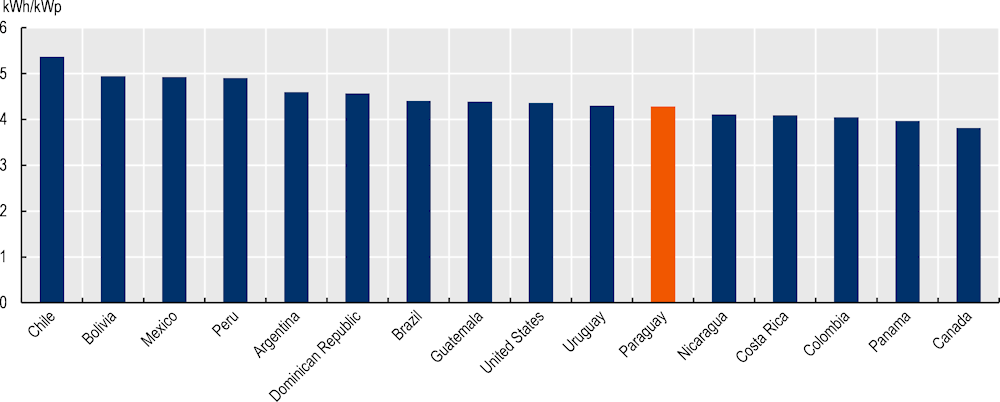

Paraguay contributes to green growth by generating renewable energy almost on par with the country’s energy supply (99%). This level of electricity production is maintained by the two binational hydroelectric plants, Itaipú and Yacyreta.

Main findings on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Paraguay experienced a relatively mild contraction in 2020 compared to the LAC and OECD averages, however the onset of a drought in 2019 had already triggered an economic slowdown.

Restaurants and hotels, services to households, business services and commerce were hit hardest during the pandemic in 2020 but showed already signs of recovery in 2021.

In 2021, the agriculture and electricity and water sectors continued to underperform as a result of a drought that negatively affected soy production and electricity generation in the two binational dams. The simultaneous shock of the pandemic and the drought highlighted Paraguay’s vulnerability to climate change.

Most employment in Paraguay is concentrated in micro- and small enterprises, both of which were severely affected by the pandemic.

Policy responses

Government policy responses to support business production and investment during the pandemic included the following measures targeted at service industries (e.g., gastronomy, events, tourism, and hotel services):

income support measures consisting of subsidised utility bills, reduced VAT for certain sectors, reductions in the employer’s contribution rate (aporte obrero patronal) and extensions for the payment of taxes.

credit support measures such as different lines of credit provided by the state-owned bank Crédito Agrícola de Habilitación (CAH), the public development bank Agencia Financiera de Desarrollo (AFD) and the Banco Nacional de Fomento (BNF), as well as a strengthened guarantee fund (FOGAPY) to support access to credit for MSMES.

Strategies for the recovery

To ensure a robust and sustainable recovery, Paraguay must tackle the structural problems exposed by the pandemic, while also learning from innovative approaches applied during the crisis:

Tackling informality remains a key priority to reduce vulnerability and increase productivity. Widespread informality in the Paraguayan economy represented one of the most serious obstacles to the government’s COVID-19 response. As formalisation is not a linear, one-step process, any successful formalisation strategy requires a holistic approach with added incentives to formalise (e.g., access to social protection, financing, capacity building and business services) as well as supervision and enforcement mechanisms (e.g., enhanced inspections).

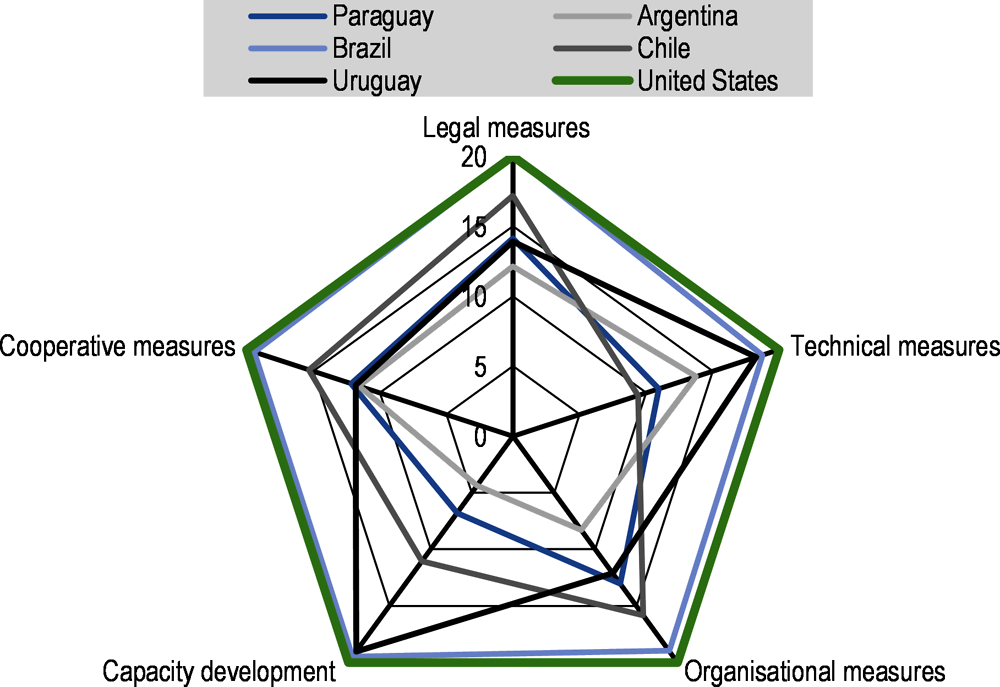

Ensuring that the process of digital transformation that accelerated during the pandemic remains a driver of inclusive growth. Supporting and accelerating digitalisation is particularly important for Paraguay given the absence of transport costs, which are high as a result of the country’s geography. This will require greater investment in digital infrastructure as well as in digital skills and access to digital technologies. Strengthening Paraguay’s digital governance will also be of importance, particularly in the areas of data protection and digital security.

Capitalising on the global reconfiguration of trade and commerce to increase Paraguay’s participation in global and regional value chains. Lockdowns, restrictions on travel and trade in goods, disruption of international transport networks and changes in demand for goods and services all disrupted GVCs during the pandemic. This led to an increase in the relocation of business operations to closer locations from more distant ones. In this context, opportunities exist for Paraguay to increase exports to countries in the region. Strengthening commercialisation and internationalisation policies will be key for this purpose.

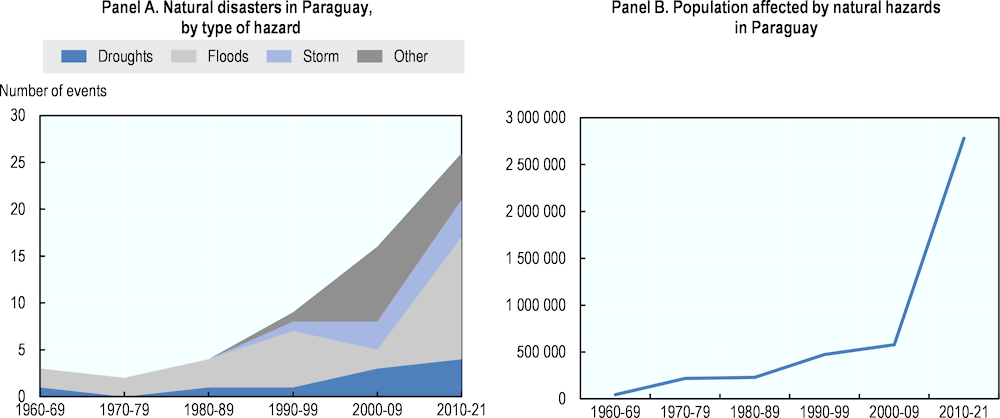

Increasing resilience to climate change. Paraguay’s reliance on agricultural commodities and hydroelectric power exports renders the country highly vulnerable to climate change. Better access to financing and crop diversification could make Paraguay’s agricultural sector more resilient to natural disasters, while improving transport infrastructure could enhance resilience to climate change. Finally, supporting the expansion of renewables other than hydropower and enhancing energy efficiency could reduce the country’s dependency on hydropower while decreasing electricity consumption, thereby strengthening Paraguay’s capacity to withstand the impacts of climate change.

Figure 3.1. The OECD COVID-19 Recovery Dashboard: Strong dimension

Source: All data for OECD countries have been extracted from the OECD Recovery Dashboard. For Paraguay, data for Panel A are taken from the World Bank (World Bank, 2022[1]), data for Panel B are from the Gallup World Poll (Gallup, 2022[2]), data for Panel C are from the World Bank (World Bank, 2022[1]) and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU, 2024[3]), and data for Panel D are from the OECD Green Growth Indicators (OECD, 2017[4]).

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Paraguay’s economy was muted but recovery was hindered by severe droughts

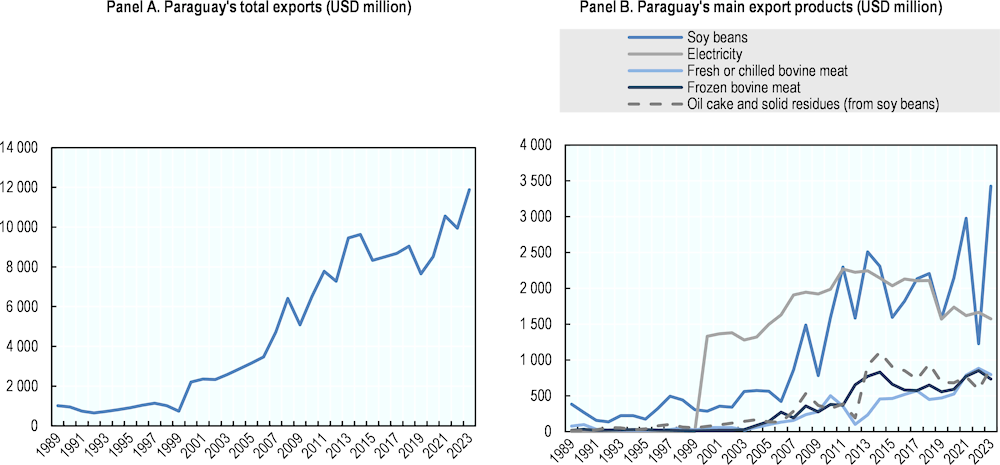

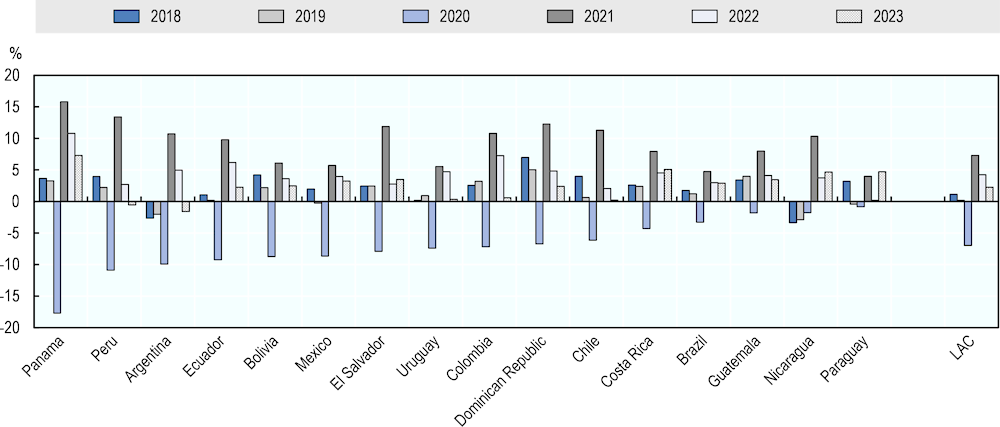

Paraguay was impacted less hard by the COVID-19 pandemic than most other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 3.2). The economy experienced a 0.8% contraction in 2020 due to the pandemic compared to a 7% contraction on average in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, even this relatively mild contraction proved harder for Paraguay to handle than for other LAC countries, due to a GDP per capita well below the LAC average (USD 5 400 in 2021 compared to a LAC average of USD 8 340 (World Bank, 2024[5])) and despite the fact that Paraguay’s growth performance prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was relatively good with a GDP growth rate averaging 4.8% between 2013 and 2018 (IMF, 2022[6]). Paraguay’s services sectors, specifically restaurants and hotels, services to households, business services and commerce, were hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic, largely as a result of mobility restrictions and lockdowns in Paraguay in 2020 (Figure 3.3, Panel C). Together, these four industries account for 20% of Paraguay’s GDP (Figure 3.3, Panel A and B). Paraguay’s exports declined as a consequence of the pandemic and an exceptional drought but rebounded quickly, with the exception of electricity exports, which were affected by the drought and only recovered in 2022 (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.2. Paraguay experienced only a mild recession in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

GDP in constant prices (% change)

Source: IMF (2024[7]) World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 and BCP (2024[8]), Anexo estadístico del informe económico, 29 April 2024, https://www.bcp.gov.py/anexo-estad%C3%ADstico-del-informe-econ%C3%B3mico-i365.

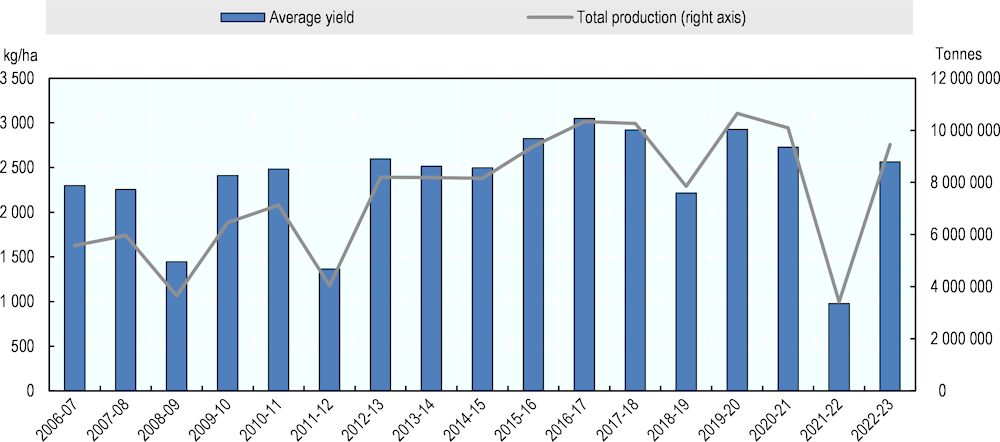

The impact of the COVID-19 crisis was compounded by a severe drought that exposed the Paraguay’s vulnerability to future extreme weather events. The drought started in 2019 and resulted in severe consequences that are still being felt years later by water-dependent sectors (SISSA, 2022[9]). The drought led to a 4.4% contraction in Paraguay’s agricultural sector in 2019 and, following a rebound in 2020, a further 18.2% contraction in 2021, despite high commodity prices, before partial recovery in 2023 (Figure 3.3, Panel B) (World Bank, 2022[10]). Paraguay’s soya production, the country’s largest export good, has been particularly affected (SISSA, 2022[9]). Soybeans and products derived from soybeans (oil, oilcake) accounted for 41.3% of Paraguay’s exports in 2021 and for 38.5% of Paraguay’s exports on average between 2017 and 2021 (UN, 2024[11]). As of 2022, agriculture accounts for 6.0% of Paraguay’s GDP (Figure 3.3, Panel A). Paraguay also experienced a three-year contraction in the electricity and water sector of 11.5% in 2019, 2.3% in 2020 and 7.6% in 2021, as a result of low water levels in the Paraná River, which led to a large fall in hydroelectricity production and exports. Electricity generation in Paraguay is based entirely on hydropower from two binational hydroelectric plants, the Itaipú (Paraguay/Brazil) and Yacyretá (Paraguay/Argentina), with the electricity and water sector accounting for 6.8% of Paraguay’s GDP (2022). Overall, the drought led to a 0.4% recession in Paraguay in 2019, even prior to the pandemic, and the draught suffered in 2022 slowed the recovery (FitchRatings, 2022[12]; World Bank, 2022[10]).

Figure 3.3. Restaurants and hotels, services to households, business services and commerce were hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: Banco Central del Paraguay, (2024[8]), Anexo Estadístico del Informe Económico, www.bcp.gov.py/anexo-estadistico-del-informe-economico-i365.

Paraguay’s reliance on agricultural commodities and hydroelectric power exports leave the country high vulnerable to climate change. Indeed, real GDP stagnated in 2022, growing only 0.1%, with a marked contraction in agriculture (-12.7%). The agriculture sector and the economy rebounded in 2023, with real GDP growth reaching 4.7% driven in part by the recovery of the agriculture sector, which grew 23% year-on-year. The recovery of agriculture also contributed to recovery in exports (Figure 3.4) (BCP, 2024[8]).

Figure 3.4. Paraguay’s exports declined as a consequence of the pandemic and a severe drought, but rebounded quickly

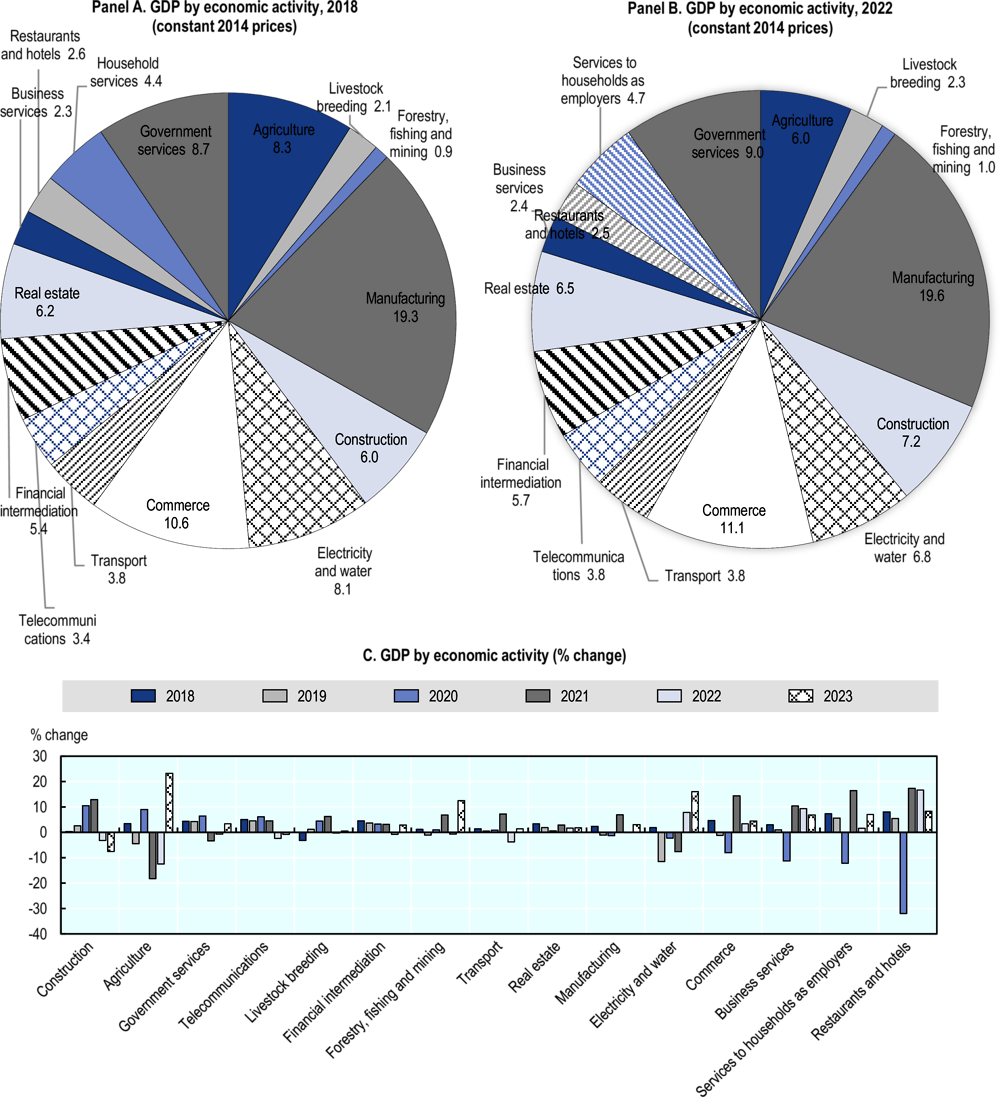

Paraguay’s micro- and small enterprises were hit hard by the pandemic. In Paraguay, both employment and companies are concentrated in micro-enterprises (Figure 3.5), which are characterised by high levels of informality. According to an online survey of 360 MSMEs conducted between February and April 2021, 70.6% of micro-enterprises, 71% of small companies and 64.7% of medium-sized companies experienced a decline in sales in 2019-20. Employment decreased in 41.8% of micro-enterprises, 53.2% of small companies and 59.2% of medium-sized firms. Companies in the services sector experienced the largest declines in both sales and employment (Sánchez Báez, Sanabria and Paredes Romero, 2021[13]). Another online survey of 635 companies, largely formal MSMEs, conducted in April 2020, found that 68% of MSMEs had completely suspended their activities as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic (as compared to 63.2% of large companies) (MIC/MTESS/SINAFOCAL, 2020[14]).

Figure 3.5. Employment is concentrated in micro- and small enterprises, which account for the majority of companies in Paraguay

Companies and employment by firm size (% of total), 2011

Source: DGEEC (2011[15]), Censo Nacional Económico 2011, https://www.ine.gov.py/publication-single.php?codec=MTE3.

Access to finance became more difficult during the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular for micro- and small companies. Some 63% of medium-sized companies requested a loan during the pandemic but only 51.8% of small companies and 50.3% of micro-enterprises. Conversely, 31.3% of micro-enterprises and 20% of small enterprises did not apply for a loan as they did not expect to be eligible; this number was lower for medium-sized firms at 4.3%. The loan applications of 36.4% of applying companies were rejected and 19.9% were granted a loan in worse conditions than in previous years (Sánchez Báez, Sanabria and Paredes Romero, 2021[13]).

Paraguay responded by supporting investment, MSMEs and productivity

Income support measures for businesses

Reduction in import tariffs. In March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Paraguay reduced import tariffs on a set of products, mainly raw materials and capital goods. Import tariffs on raw materials were dropped to 0% until December 2020 in line with MERCOSUR’s Raw Materials Regime and were reduced permanently on 162 products following an assessment of the pandemic’s impact on international trade flows under Decree No. 4694/2020. Furthermore, the reduction in import tariffs to 0% for 222 capital goods in place since 2019 was extended to December 2021 under Decree No. 5966/21.

VAT reductions. In July 2020, the VAT on gastronomy, events, tourism, and hotel services was reduced from 10% to 5% until June 2021. These reductions were subsequently extended until October 2021.

Reduction of tax on commercial rents. In July 2021, the VAT on commercial rents was reduced to 5% (instead of increasing to 10% as part of a planned fiscal reform).

Reduction in employer’s contribution for employees. In March 2021, the employer’s contribution rate (aporte obrero patronal) was temporarily reduced from 16.5% to 2.5% for the whole of 2021 retroactively from January 2021, while workers' contributions remained unchanged at 9% (see Law 6706/2021). A grace period of six months starting from July 2022 was introduced for the payment of remaining employer’s contributions (14%).

Extension of deadlines for the submission of tax returns and payments. In March 2020, the deadlines for the submission of tax returns and payments for 2019 and 2020 were extended.

Other tax reductions. In March 2021, the interest rate for the fractioned payment of taxes was reduced from 1.4% to 1.1% (13.2% annually) and late payment surcharges and interests on cash payments for old debts were eliminated for the gastronomy, events, tourism and hotel sectors.1

Utility subsidies for households and MSMEs. In March 2020, utility bill payments for basic services (electricity, telephone, and water) were waived for the months of March, April and May up to 100% for vulnerable households, MSMEs and other exposed groups. The possibility to defer payments and make them in 18 instalments with 0% interest was introduced for all other groups. In March 2021, the gastronomy, events, tourism, and hotel sectors were granted the possibility to postpone payments of electricity and water bills for March, April, May and June 2021 and additionally, debt refinancing without interest and with terms up to 18 months was possible.

Credit support measures were directed largely at MSMEs

Paraguay implemented a range of measures during the pandemic to facilitate credit for private businesses, directed mainly at MSMEs. Paraguay’s state-owned banks created several new credit lines, directed largely at MSMEs. Furthermore, two trust funds with the mission of supporting MSMEs were established and Paraguay’s guarantee fund for MSMEs was strengthened:

Establishment of new credit lines for MSMEs, particularly in rural areas and the agro-food sector. In March 2022, the state-owned bank Crédito Agrícola de Habilitación (CAH) created new lines of credit to attribute loans for up to 24 months with an annual interest rate of 8.9% (excluding administrative fees) and flexible repayment conditions, in accordance with cash flows and income generation, to smallholder farmers, small entrepreneurs and micro- and small businesses in the productive, commercial and services sectors. In March 2021, the loans were extended for an additional year.

Strengthening of Paraguay’s guarantee fund for MSMEs (Fondo de Garantía del Paraguay, FOGAPY). To encourage financial institutions to provide more loans to MSMEs, in March 2020, Paraguay’s guarantee fund for MSMEs was recapitalised and allocated an additional USD 100 million through the Ministry of Finance to support 39 financial institutions in the provision of loans to formal MSMEs. In July 2020, several articles of Law 5628/2016 that created FOGAPY were modified through Law 6579/2020 from 30 July 2020. The fund’s volume of financial resources for guarantees was augmented and the coverage of loans for riskier segments of beneficiaries was increased from 70% to 90% of the loans. Furthermore, target beneficiaries were widened to include large companies and additional guarantees were granted to businesses in the hotel, gastronomy, tourism, and events sectors (FOGAPY, 2020[16]). In October 2021, FOGAPY was attributed additional resources worth USD 25 million.

Creation of a trust fund to support MSMEs (FISALCO). In March 2020, a trust fund, the Fideicomiso para pago de Salarios y/o Capital Operativo (FISALCO), administered by Paraguay’s development bank, the Agencia Financiera de Desarrollo (AFD), was established to promote credit lines for MSMEs. The Trust Fund was funded through 20% of the Banco Nacional de Fomento’s (BNF) net profits in 2019 and endowed with approximately USD 85 million. FISALCO directly granted financial resources to credit institutions to be used to administer loans to MSMEs at interest rates capped at 5.5% annually for the payment of salaries and operating capital. It differs from FOGAPY in that financial resources for loans are transferred directly to credit institutions. FISALCO is no longer operational.

Creation of the emergency Pro-Reactivación programme by the AFD to provide liquidity to financial institutions. This emergency programme was created by the AFD and between June 2020 and September 2020 provided further liquidity to financial institutions at a 5% interest rate, supporting the creation of further credit lines with a term of up to seven years and a one-year grace period. The resources available to the programme amounted to PYG 360 billion (AFD, 2020[17]).

Creation of a programme to refinance credit operations. AFD directed PYG 800 billion to financial institutions to help their clients refinance their credit operations for operating capital or investment in productive activities with a term of up to seven years and a two-year grace period (AFD, 2020[17]).

Opening of a credit line to provide operating capital for MSEs by the Banco Nacional de Fomento (BNF). Starting from March 2020, micro- and small enterprises could obtain loans for operating capital from the public bank at an annual interest rate ranging from 7% to 8.5% for loans in PYG, and 5% for a one-year loan in USD. To qualify for these credits, MSEs should be at least one-year old, be compliant with tax obligations and not have any overdue transactions (BNF, 2020[18]).

Exemption from reserve requirements for new loans to MSMEs. In March 2020, Paraguay’s central bank, the Banco Central del Paraguay (BCP), decided that new loans granted prior to 30 June 2020 to businesses, preferably MSMEs, would be exempted from reserve requirements for a period of up to 18 months (Resolución N° 23, Acta N° 23 del 02/04/2020). Subsequently, this measure was extended until the end of 2020.

Grace period for the repayment of loans. A one-year grace period for the repayment of loans was introduced and then extended by an additional year in March 2021 for businesses in the gastronomy, events, tourism, and hotels sectors.

Trust fund to support MSMES and formal workers in the gastronomy, event, hotel, tourism, and entertainment sectors, administered by the BNF. In October 2021, a trust fund administered by BNF was established to provide financial support to MSMEs and formal workers in the gastronomy, events, hotel, tourism, and entertainment sectors. USD 20 million were attributed to the trust fund, which will provide loans at interest rates between 2% and 4% of terms of up to ten years, with a three-year grace period, to micro-entrepreneurs and self-employed workers (up to PYG 75 million), small businesses (up to PYG 150 million) and medium-sized businesses (up to PYG 300 million).

The Ministry of Industry and Commerce also provided assistance to around 1 346 MSMEs in the process of accessing credit from AFD and Crédito Agrícola de Habilitación (CAH) (MIC, 2022[19]).

Production support measures

Visibility of MSMEs in Google. To support the digitalisation of MSMEs, the Ministry of Industry partnered with the marketing platform Kolau and Google to offer digital training to firms and small businesses and help them strengthen their web presence and increase their online sales. This collaboration resulted in the creation of 483 web pages and 430 online shops (MIC, 2022[19]).

Business environment

Updating of categorisation parameters for MSMEs. Through Decree No. 3698/2020 of June 2020, the Ministry of Industry and Commerce increased by 29% the maximum annual turnover of each of the three categories in line with the cumulative variation of the consumer price index, in order to expand the number of businesses able to access the measures to support MSMEs.

Creation of a new form of incorporation. The Simplified Joint Stock Company (Empresa por Acciones Simplificadas, EAS), established by Law 6480/2020 and characterised by the simplification of procedures for incorporation and registration, was designed to reduce the bureaucratic obstacles to creating companies. This new legal personality, unlike existing corporate categories in Paraguayan legislation, can be constituted by a single person, is processed entirely online at zero cost, and is constituted in a maximum of 72 hours. As of August 2023, 6 388 EAS had been created under this new type of legal category.2

Transparency improvements. In December 2021, the Economic Development Advisory Council was created by Paraguay’s Ministry of Industry and Commerce. It convenes once a month and is composed of representatives of business associations, including MSMEs. The council’s objective is to provide a space to discuss pressing issues and public policies with the private sector.

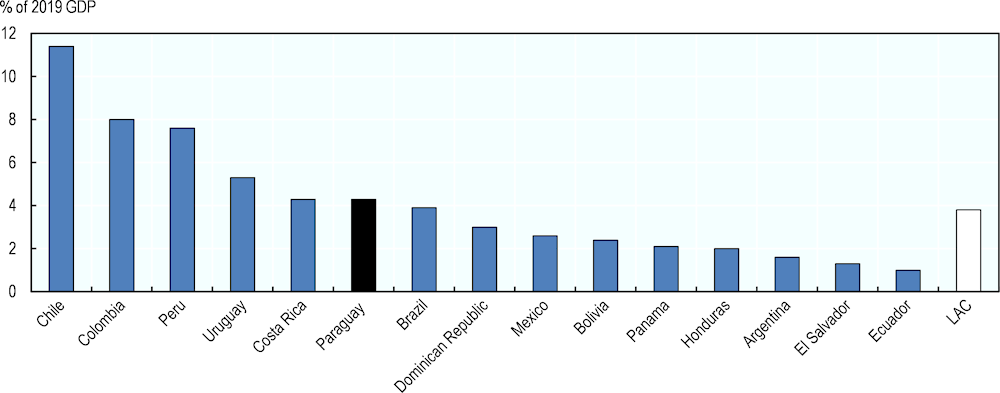

Figure 3.6. Paraguay announced a substantial amount of credit support measures directed largely at MSMEs in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Total credit support measures announced (% of 2019 GDP), 27 May 2020

Note: The estimation only includes policies for which a quantifiable amount could be identified.

Source: ECLAC (2020[20]), Sectores y empresas frente al COVID-19: emergencia y reactivación.

Geography, informality, institutional quality and skills stand out among the structural challenges for a strong economy in Paraguay

Paraguay’s geography and quality of transport infrastructure result in high transport costs

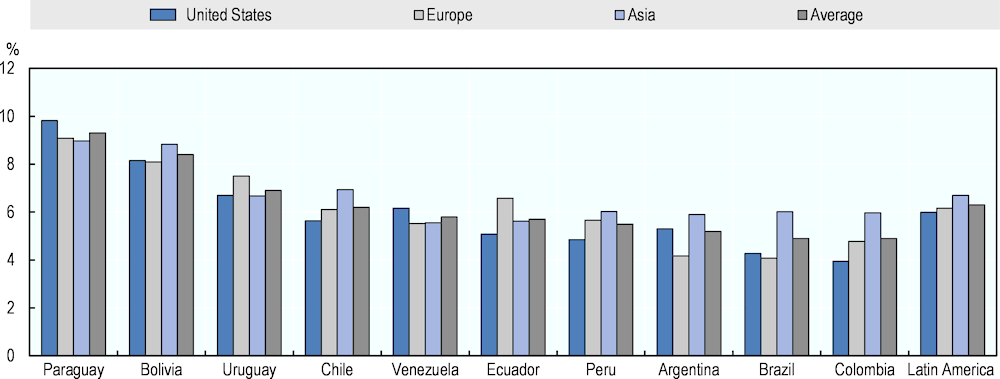

As a landlocked country, Paraguay has high transport and logistical costs. The country’s transport costs are the highest in the region, averaging 9.3% of traded value compared to 6.3% on average in Latin America (Figure 3.7). Transport costs are higher for commodities than for manufactured goods. Paraguay relies largely on its rivers for merchandise and international trade: 42% of the country’s merchandise trade is transported by river, 24% via road and the remainder by air (34%). However, river-based transport accounts for 65.6% of transport costs, while road accounts for 15.1% and air freight for 20.4%, reflecting the differences in value added of goods transported through the waterways (ALADI, 2016[21]).

Figure 3.7. Paraguay’s transport costs are the highest in the region

Transport costs (% of traded value), 2016

Source: ALADI (2016[21]), El Costo de la Mediterraneidad: Los Casos de Bolivia y Paraguay, www2.aladi.org/biblioteca/Publicaciones/ALADI/Secretaria_General/SEC_Estudios/216.pdf.

Infrastructure gaps further add to Paraguay’s high transport costs. As a landlocked country, Paraguay’s competitiveness in international trade is highly dependent on its own and neighbouring countries’ transport and logistics infrastructure to access international markets and seaports. However, the quality of this infrastructure remains an issue. The Paraguay-Paraná waterway, which connects Paraguay with the ocean ports of neighbouring countries, lacks dredging and signalling, which would enable navigation all year round. Furthermore, despite notable improvements, the quality of Paraguay’s port infrastructure remains poor (OECD, 2018[22]). The same is true for Paraguay’s airport infrastructure: Paraguay ranked 104th out of 117 countries in terms of efficiency of air transport in 2021 with a score of 3.7 out of 7 (WEF, 2022[23]). This constitutes an improvement compared to previous assessments – Paraguay ranked 122nd out of 141 countries in the 2019 Global Competitiveness Index (WEF, 2019[24]) – but still represents a low level of perceived efficiency. As such, Paraguay’s port and airport systems require administrative, technological, and infrastructural improvements (World Bank, 2019[25]). The country’s road network, however, is sufficient to cater for the majority of the population, with a road density of 0.2 km per square km, above that of neighbouring Brazil (0.19) (World Bank, 2019[26]; IRF, 2023[27]). However, the quality of road infrastructure is a constraint for businesses, and the perceived quality of roads has been a longstanding issue. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), the quality of road infrastructure indicated for Paraguay has improved from 2.48 (on a scale from 1 to 7) in 2018 to 2.9 in 2021, but remains well below that of peer countries (ranking 107 out of 117 countries in 2021) (WEF, 2019[24]; WEF, 2022[23]). The Government of Paraguay has put significant effort into developing the road network in the past five years. Notably, the proportion of the network that is paved increased from 11.8% in 2017 to 15% in 2021 (IRF, 2023[27]), with new paved roads and the paving of existing roads reaching 4 169 km between 2018 and 2023 (MOPC, 2023[28]). Regarding rail transport, the few railways that exist in Paraguay are used only for passenger travel but not for merchandise transport. Expanding and upgrading Paraguay’s rail system and integrating it with those of neighbouring countries could create new transport corridors for imports and exports and reduce transport costs (OECD, 2018[22]). There is also much scope for improvements in intermodal transport and border crossings (ECLAC, 2020[29]).

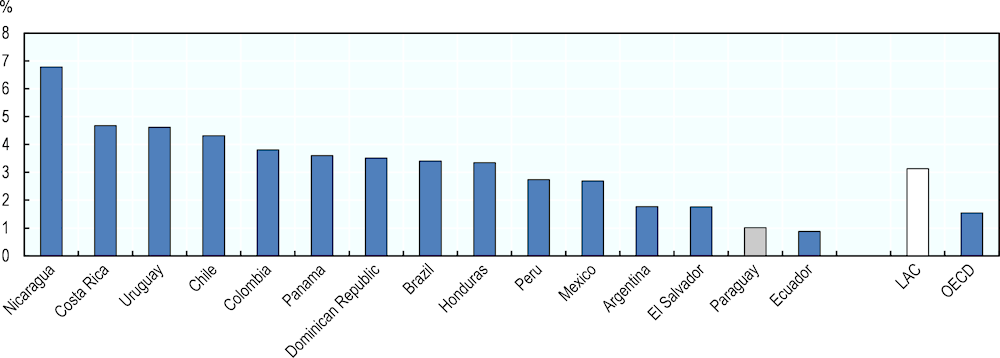

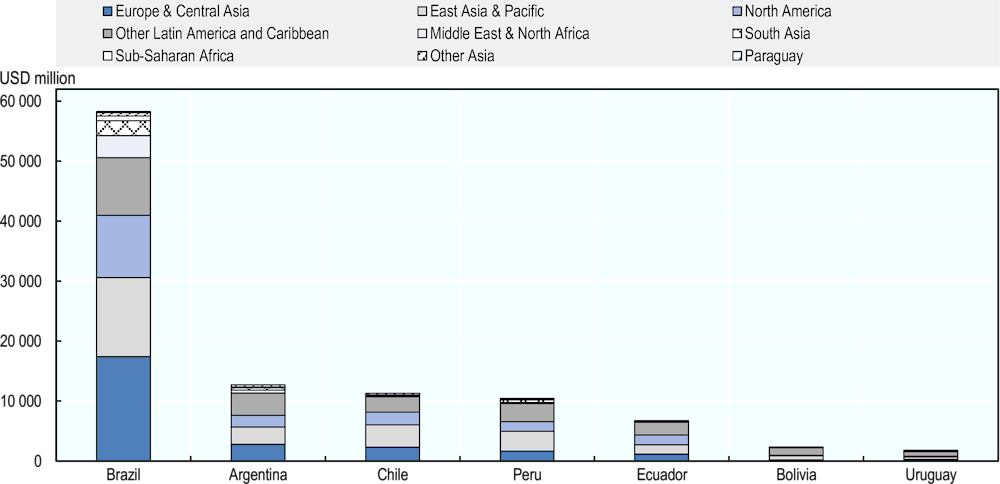

Institutional quality, a shortage of skilled workers and poor infrastructure in Paraguay limit FDI flows

FDI flows in Paraguay remain low by regional standards. Average annual FDI inflows between 2017 and 2022 amounted to only 1% of GDP compared to 3.1% of GDP on average in the LAC region and 1.5% in OECD countries (World Bank, 2024[5]). FDI inflows increased in 2022 to USD 725 million, binging the average up, but inflows remain modest in the regional landscape. This situation has persisted despite Paraguay’s advantages for investors: fast economic growth rates; macroeconomic, fiscal and political stability; low energy costs; plenty of fertile land; low taxes; a young labour force and preferential access to the Brazilian and Argentinian markets (Quijada, Sierra and Espinola, 2018[30]; Dettoni, 2022[31]). Traditionally, FDI in Paraguay has originated principally from countries in the region such as Brazil (13% of Paraguay’s FDI stock in 2021), Chile (8%) and Uruguay (7%) as well as the United States (13% of Paraguay’s FDI stock in 2021) and European countries such as the Netherlands (11% of Paraguay’s FDI stock in 2021) and Spain (8%) (BCP, 2022[32]).

Institutional quality is an important concern for investors in Paraguay. An IDB publication identifies Paraguay’s institutional quality, including perceptions of corruption, judicial independence and property rights, as important deterrents for FDI in Paraguay. The country is 25% less likely to receive FDI compared to countries with similar characteristics but better institutional quality. Moderate improvements in institutional quality would have a considerable impact on Paraguay’s competitiveness and could raise the amount of FDI the country receives compared to neighbouring Costa Rica, Guatemala, Panama, and Peru (Quijada, Sierra and Espinola, 2018[30]). In line with these results, corruption has been identified as the second-biggest obstacle by private companies in Paraguay (23.9%) following the informal sector (24.1%) (2017) (World Bank, 2017[33]). Furthermore, Paraguay performs poorly on the Global Competitiveness Index’s institutional pillar (score 44/100, rank 115/141 countries), in particular, in terms of future orientation of the government (score 38.9/100, rank 124/141 countries), checks and balances (score 38.5/100, rank 115/141 countries), corporate governance (score 46.2/100, rank 112/141 countries), transparency (score 29/100, rank 111/141 countries) and public sector performance (score 40.3/100, rank 107/141 countries). On these dimensions, Paraguay scores worse than other countries in the region (WEF, 2019[24]). Paraguay ranks only 125th out of 190 countries on the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking.

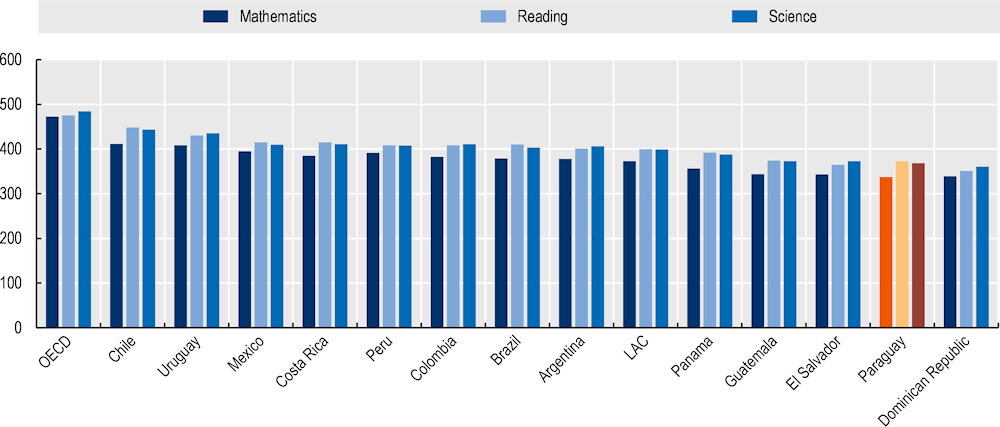

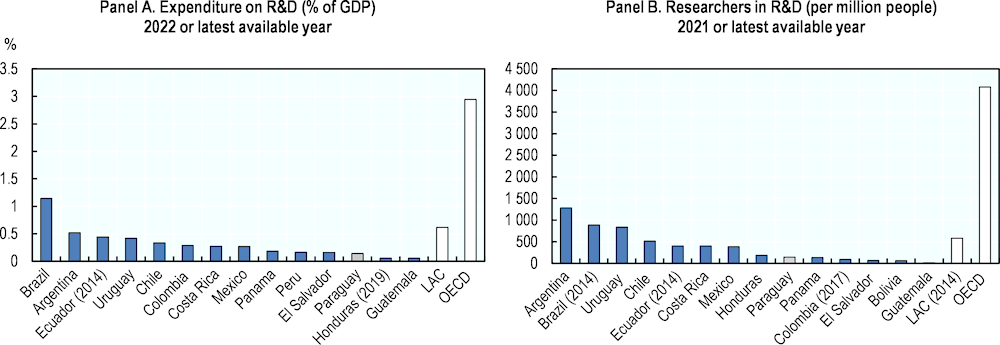

A shortage of skilled workers and poor infrastructure represent additional concerns for investors in Paraguay (Dettoni, 2022[31]). A poorly educated workforce (12.9% of companies) was the third-biggest obstacle identified by private companies in Paraguay (2017) (World Bank, 2017[33]). The country performs poorly on the Global Competitiveness Index in terms of the skills of the current workforce (score 36.8/100, rank 136/141) with the quality of vocational training, the skillset of graduates, digital skills among the active population and finding skilled employees all identified as challenges. In terms of infrastructure, 26.7% of companies in Paraguay identified transport as a major constraint compared to 23.7% of companies on average in the LAC region, and 83% of Paraguayan firms have experienced electrical outages compared to 59.2% on average in the LA region (World Bank, 2017[33]).

Figure 3.8. Paraguay’s FDI inflows are among the lowest in the LAC region

Foreign Direct Investment, net inflows (% of GDP), 2017-22 average.

Paraguay’s informal sector is large and illegal activities such as smuggling are widespread

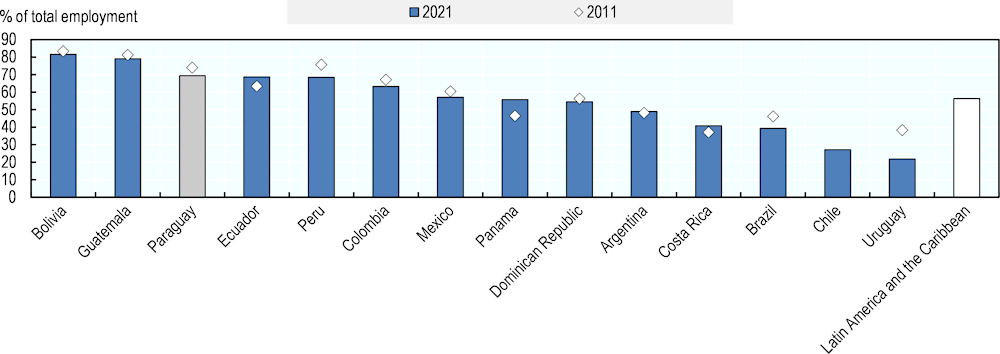

Despite the country’s relatively low tax rates, Paraguay is characterised by a high level of informality. In 2021, 69.3% of all employment in Paraguay (and 63.5% of non-agricultural employment) was informal3 compared to 56.3% on average in LAC countries (Figure 3.9) (ILO, 2022[34]). Own-account workers (21.2% of employment) and micro-enterprises with up to 10 employees (39.8% of employment) account for most informal employment (INE, 2022[35]). According to estimates by FEPRINCO, Paraguay’s informal economy amounted to 18.9% of GDP in 2020 (FEPRINCO, 2022[36]).

Figure 3.9. Paraguay’s informal sector is significant

Informal employment (% of total employment)

Note: For Dominican Republic and Uruguay, data are for 2020 instead of 2021; for Bolivia and Guatemala, data are for 2019 instead of 2021. The LAC average is based on 2019-2021 data for 18 Latin American countries.

Source : ILO (2022[34]), ILOStat, https://ilostat.ilo.org.

Illegal activities account for a large share of Paraguay’s economy. A report published by Pro Desarrollo Paraguay in partnership with the National University of Asunción estimated the value of Paraguay’s shadow economy – encompassing not only informal activities but also all types of illicit transactions, including bribes, drug trafficking, smuggling and money laundering – at USD 11 billion in 2015, the equivalent of 39.6% of Paraguay’s GDP. The report relied on differences in GDP growth and growth in electricity consumption, the demand for cash and the salaries of informal workers as compared to total labour income to estimate the size of Paraguay’s underground economy. As a result of this large shadow economy, Paraguay’s government would have lost USD 1.1 billion in tax revenues in 2015 (Clavel, 2016[37]; Pro Desarrollo Paraguay, 2016[38]). A World Bank study arrives at similar results, estimating Paraguay’s shadow economy at 36.7% to 37.4% of GDP in 2007 compared to 41.4% of GDP on average in the LAC region (Schneider, Buehn and Montenegro, 2010[39]). A report by Global Financial Integrity estimates that illicit financial outflows from Paraguay, including both trade mis-invoicing and illicit hot money flows, amounted to 20.2% of Paraguay’s GDP on average between 2004 and 2013 compared to an LAC average of 8.4% and 1.4% in Brazil, 2.2% in Argentina and 3% in Chile. Trade mis-invoicing accounts for the large majority of these illicit financial outflows from Paraguay (Kar and Spanjers, 2015[40]).

Paraguay is a regional hub for smuggling. In particular, the triple border area with Argentina and Brazil is one of the busiest smuggling corridors in the world. Cigarettes are among the most important smuggling goods due to the significant amount of illicit tobacco production in Paraguay. A recent study estimated the volume of cigarette smuggling in the country by comparing Paraguay’s cigarette exports and domestic consumption with imports and domestic production of raw materials for cigarette production (raw tobacco and cigarette filters). It found an excess supply of cigarettes of 2.5 billion packs annually on average between 2008 and 2019 (Masi et al., 2021[41]). This means that only about 10% of cigarettes produced in Paraguay are sold on legal markets, 5% domestically and 5% for exports (Bargent, 2017[42]). There is further evidence that in addition to cigarette smuggling into neighbouring countries, a significant amount of Paraguay’s legal cigarette exports to countries such as Bolivia, Aruba, Curaçao and Suriname actually continues to be illegally shipped to third countries (Masi, Rodriguez-Iglesias and Drope, 2022[43]).

Widespread smuggling is a result of price and tax differences and widespread corruption and impunity. A huge discrepancy in taxation levels for cigarettes between Brazil and Paraguay makes contraband trade highly attractive: cigarettes are taxed at only 16% in Paraguay compared to 80% in Brazil. Furthermore, while cigarette smuggling offers high profits, risks are much lower compared to more traditional smuggling activities such as drug or arms trafficking. The huge profits offered by cigarette smuggling have attracted not only smuggling rings into Paraguay but also organised crime networks, insurgent groups and money launderers (Bargent, 2017[42]; Dalby, 2022[44]).

Smuggling became even more widespread in Paraguay in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The void created by the closure of legal industries, as a result of mobility restrictions and supply shortages, was filled by smugglers supplying basic products such as meat, sugar, fruit and vegetables. Many Paraguayans continued to depend on this shadow economy for months, as uncertainty persisted and products were often cheaper on the black market (Dalby, 2022[44]).

Smuggling is particularly harmful to the Paraguayan economy, reducing current tax income and blunting investment incentives. The general level of tariffs is relatively low in Paraguay (4.1% in weighted terms in 2020) but border taxes remain important relative to a relatively modest level of total tax revenues, while lack of border controls also removes imported goods from the VAT base. Competition from the informal sector under these circumstances is particularly acute. Smugglers do not abide by tax and social security provisions, and often also focus their efforts on cheaper products that escape sector regulations – including for health and safety. This can explain why 24% of Paraguayan businesses identified competition from the informal sector as the biggest constraint to doing business in the latest enterprise survey carried out by the World Bank (2017), compared to 17% of firms in the LAC region on average (World Bank, 2017[33]).

Lessons from recovery measures and new opportunities: A holistic approach to MSME informality, building resilience to climate change, and capitalising on digitalisation and regional integration

Tackling informality in MSMEs from a holistic perspective

Strengthening micro-, small and medium-sized enterprises is a key objective for Paraguay's development. MSMEs are a major contributor to employment in Paraguay but are significantly less productive than larger firms (Feal Zubimendi and Ventura, 2023[45]). Improving the competitiveness of MSMEs is therefore a priority for the Paraguay government. Formalisation is a key objective in strengthening MSMEs, and is recognised as one of the strategic axes and a key cross-cutting axis in Paraguay’s MSME strategy (MIC, 2019[46]). As discussed during a policy workshop held as part of this review, Paraguay is advancing on multiple fronts to improve the competitiveness of MSMEs including by: i) strengthening digital resources to expand the diversification, productivity and quality of MSMEs; ii) introducing progressivity into the tax system; iii) moving beyond the current legal framework of voluntary social security contributions towards a mandatory and special scheme for MSMEs and the self-employed; iv) expanding credit opportunities; and v) better informing workers about the benefits of formality.

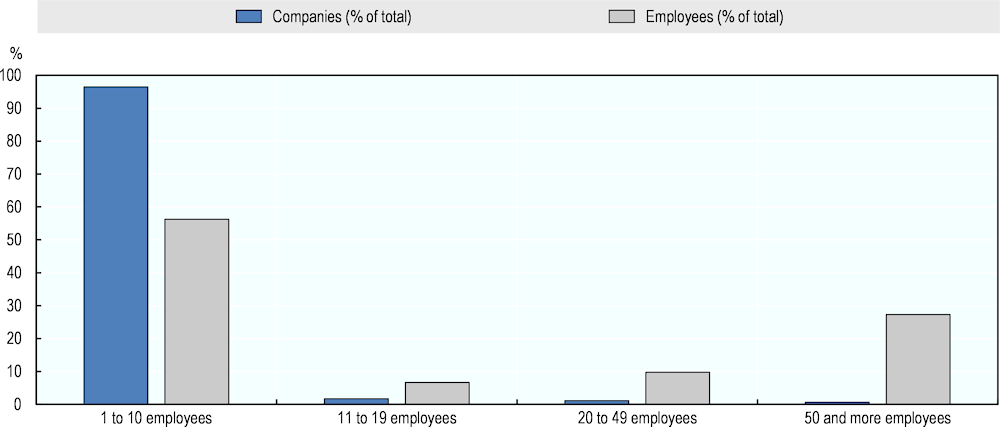

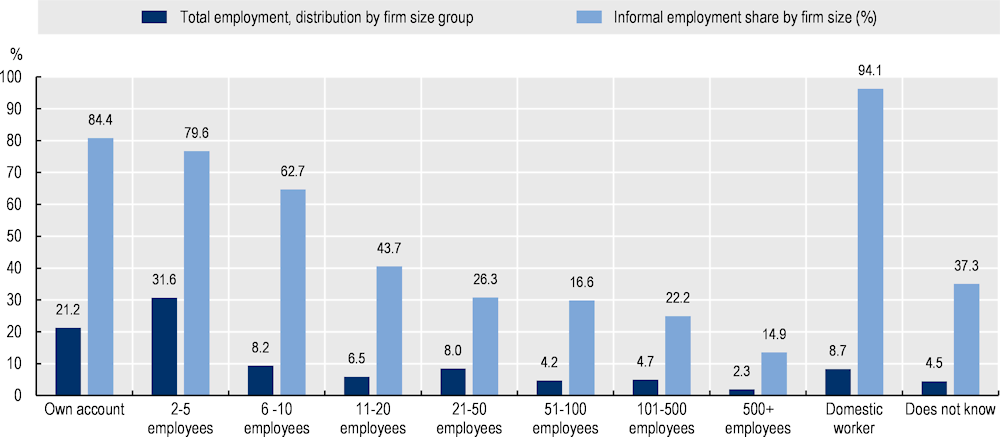

Widespread informality in Paraguay contributes to low levels of productivity and obstructs firms’ development

Widespread informality in the Paraguayan productive structure was one of the most important obstacles during the response to the COVID-19 crisis. The economy is characterised by the dominance of own-account workers (21.2% of the employed population in 2020) and micro-enterprises (up to ten employees, 39.8% of employed), which together account for over 60% of the total employed population in the country (Figure 3.10, Panel B). These small economic units tend to employ unskilled labour and have relatively lower productivity levels than bigger enterprises. They are also characterised by a higher level of business and labour informality. In fact, in 2018, 71.9% of firms with up to ten employees were not registered in the Registro Único del Contribuyente (RUC) necessary for paying taxes, equivalent to 69.8% of total firms according to joint estimates of the INE and the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (MIC) (Insfrán and Ramírez, 2021[47]).

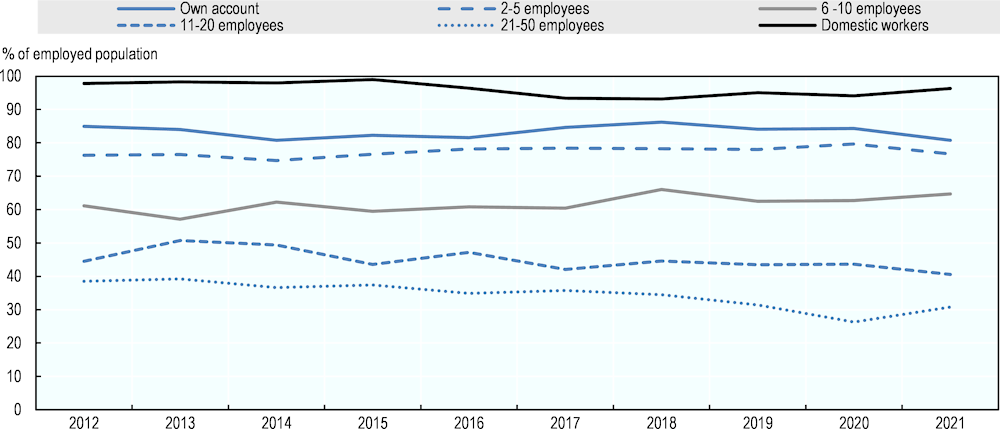

Moreover, as formalisation is a gradual process, even firms registered in the RUC may not be compliant with tax obligations or have registered workers with social security. As Figure 3.10 illustrates, a high share of employees working in this sector of the economy tends be informal, representing the majority of own-account workers that usually work subsistence jobs. This share accounts for 79.6% of those employed in firms with 2-5 employees and 62.7% of those employed in firms with 6-10 employees. However, labour informality not only affects domestic and own-account workers, and SMEs; 16.6% of those employed in firms with 51-100 employees, 22.2% of those employed in firms with 101‑500 employees and 14.9% of those employed in firms with 500+ employees were also informal (Figure 3.10). Indeed, recent estimates show that even within firms registered with the tax authorities, only 35% of small and 63% of medium-sized firms are also registered with social security (IPS) and the Ministry of Labour. The corresponding figure is 7% of very small firms, with size determined by turnover (MIC et al., 2023[48]).

Figure 3.10. Firm size is an important determinant of informality

Total employment by firm size and rate of informality by firm size, 2021.

Note: The figure does not include the departments of Boquerón and Alto Paraguay.

Source: INE. Encuesta Permanente de Hogares 2012-2016, Encuesta Permanente de Hogares Continua 2017-2021. Cuarto trimestre. Serie comparable, www.ine.gov.py/default.php?publicacion=3.

As well as resulting in lower growth and poor-quality labour conditions, informality is also associated with obstacles that inhibit a firm’s development. Examples include poor access to financing through formal channels, restricted access to business support and development services, inability to participate in public procurement processes and poor insertion in supply chains (ILO, 2017[49]). As observed during the COVID-19 crisis, informality also results in poor access to emergency support mechanisms and automatic stabilisers. The invisibility of these firms and workers further complicates the targeting of ad-hoc instruments destined for this vulnerable group.

Box 3.2. Policy workshop on the formalisation and strengthening of MSMEs

As part of the process documented in this report, the OECD and the governments of Panama and Paraguay organised an international workshop on “Policies to support and formalise MSMEs for a new model of sustainable development for the post-COVID era”, held on 13 November 2023. The online workshop gathered representatives from the public and private sectors of both countries as well international experts. The objective was to facilitate exchange sat a regional level on policies for the strengthening and formalisation of MSMEs and help identify avenues to promote this agenda in Panama and Paraguay.

The participants concurred on the importance of formalising and strengthening MSMEs in Panama and Paraguay, agreeing that MSMEs and independent workers are major contributor to employment but also have the highest levels of informality, with low levels of productivity compared to large companies.

The workshop noted the commitment of participating actors – governmental and non-governmental – to strengthen MSMEs through a multiplicity of actions and instruments, several of which were bolstered during the COVID-19 pandemic. The following key points were among those discussed in relation to supporting productivity in MSMEs:

An institutional strategy based on multistakeholder participation is essential to incorporate views and tools from each key sector.

Access to credit is a key mode of intervention, as MSMEs typically have less access to credit from the formal financial sector. Clear communication campaigns are key to expanding demand for credit and establishing the basis for a culture of entrepreneurship.

Support programmes that respond to the specificity of firms’ needs must be developed. A variety of programmes and approaches are required across different sectors and the life cycle of firms based on their positioning. These include the provision of quality advice and services to MSMEs and management training. Different kinds of training can play multiple roles in supporting the formalisation and strengthening of MSMEs. They can build capacity through the use of digital tools, but also contribute to a culture of entrepreneurship that values opportunity and innovation and understands the importance of formalisation.

The simplification of procedures can promote business registration and thus contribute to the formalisation of MSMEs. This approach should include the digitalisation of basic procedures as well as the creation of new categories better adapted to the reality of MSMEs.

MSME programmes and productivity support programmes should be better aligned. Both efforts often operate on parallel tracks despite numerous interactions. In particular, access to credit, markets and services provided through entrepreneurship and MSME support programmes can be incentives to formalise.

The workshop also noted that formalisation remains a crucial challenge, and one that requires:

legal frameworks adapted to the capacity of MSMEs in terms of incorporation, tax and social security regulation, and sector regulations.

easy procedures that limit the cost and bureaucratic burden of formalisation.

greater awareness that formalisation brings benefits, rather than simply imposing costs on entrepreneurs and MSMEs.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Formalisation requires a holistic approach based on a combined set of policies

Evidence shows that formalisation requires a holistic approach combining a range of policies and regulations. Formalisation is neither a linear nor a one-step process, as demonstrated by the number of firms that formalise and then fall back into informality, as well as by the number of firms that formalise only partially (see above). At every stage of the formalisation process, firms are assessing whether the benefits of further formalisation outweigh the costs (ILO, 2017[49]; Díaz et al., 2018[50]). Hence, tackling informality requires a comprehensive strategy responding to a variety of obstacles that firms may encounter on their path to formalisation. Moreover, policies should provide incentives for firms to remain formal and prevent them from reverting back to informality.

The policy framework for MSMEs is relatively recent in Paraguay. The adoption of Law No. 4457 in 2012 for micro, small, and medium enterprises represented an important achievement, creating a regulatory framework that acknowledges the importance of MSMEs in the Paraguayan economy and streamlining a series of policies and incentives aimed at this vital sector of the economy. The same law also created the National System of MSMEs (Sistema Nacional de MIPYMES, SINAMIPYMES), an intersectoral body involved in the creation, formalisation, development, and competitiveness of MSMEs, under the direction of the Vice Ministry of MSMEs in the MIC. The latter was created during the same year through Decree No. 9261 but has little power and resources to exercise its co-ordination role from the relatively lower rank of a vice ministry.

In recent years, the main initiatives targeted at MSMEs have addressed formalisation and registration, access to financing, and capacity building and technical assistance for innovation. These themes are also among the main pillars of the First Strategic Plan for the Promotion and Formalisation of MSMEs 2018-2023 (MIC, 2019[46]). Yet, formalisation strategies still remain fragmented across different ministries, including the Vice Ministry for MSMEs, the Ministry of Labour (MTESS) and the Subsecretary for Taxation (SET).

Beyond reducing obstacles to formalisation through the simplification of registration and licensing processes, a holistic formalisation strategy requires policies to encourage formalisation, increase productivity, facilitate dialogue, and enforce the correct application of norms. Evidence shows that the simplification of administrative processes usually results in an initial increase in business registration, but that the effect of these measures tends to fade over the medium term (Díaz et al., 2018[50]). To ensure continued commitment to the formalisation process, it is important to encourage MSMEs to remain formal through a comprehensive set of policies, including “sticks”, (e.g. increased enforcement and inspections) and “carrots” (e.g. access to public services and public procurement, simplified tax regime and business services).

Enforcement and labour inspections are essential and should accompany any incentives to formalise. Labour inspections remain scarce in Paraguay and the number of labour inspectors is insufficient to cover the entire national territory. The labour inspectors employed by MTESS decreased from 31 in 2015 to 25 in 2019 and their level of training remains insufficient. In particular, serious shortcomings in labour inspections have been found in the Chaco region and, although the government has opened a local MTESS office, it has neither the means nor the autonomy to investigate possible irregularities in situ, since inspectors can only enter rural properties with a court order (CI-IT, 2021[51]). Labour inspections could play a particularly important role in decreasing the share of informal workers in large firms with more than 50 employees (Figure 3.10).

The legal and administrative framework for MSMEs has become more conducive, but challenges remain

Enterprise formalisation strategies have focused on simplifying the administrative processes for registration of MSMEs and lowering the associated cost. This was accomplished first through the one-stop shop Sistema Unificado de Atención Empresarial para la Apertura y Cierre de Empresas (SUACE) and subsequently through the Empresa por Acciones Simplificadas (EAS). The EAS is a new form of incorporation established by Law 6480 of 2020 that allows to register a firm in 72 hours at zero cost. This new corporate form has also been adopted in Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Mexico, and more recently in Ecuador, Peru and Uruguay due to its flexibility: there are no minimum capital requirements and an EAS can be opened by a single entrepreneur (de la Medina Soto, 2021[52]). Between February and December 2021, over 1 000 businesses were created in the form of an EAS (AFD, 2021[53]).

A special tax regime has also been introduced for SMEs with the aim of simplifying tax payments and encouraging business formalisation. In 2020, a new tax reform entered into force (Law 6380 of 2019) amalgamating a number of taxes into a single corporate tax (Impuesto a la Renta Empresarial, IRE) and introducing three different regimes based on the annual turnover of the business. The RESIMPLE regime is based on a monthly fixed contribution of at least 0.1% of annual turnover for businesses with a turnover up to PYG 80 million. While a fixed contribution means that businesses at the bottom of the bracket will pay more as a share of turnover than those at the top of the bracket, the annual contribution represents at most 2.4% of annual turnover, making it highly beneficial for firms to choose this regime. In addition, businesses that do so pay no VAT. The SIMPLE regime introduces a contribution of up to 3% of annual turnover or 10% of annual net profits for businesses with a turnover up to PYG 2 billion. The general system introduces a contribution of 10% of annual net income for businesses with an annual turnover over PYG 2 billion. Assessing the benefits of this reform in terms of the number of new formal enterprises will be key as the effects of the COVID-19 crisis dissipate. The SET registered a 59.5% increase in the number of taxpayers registered with the Single Taxpayer Registry (RUC), from 824 thousand to 1 315 thousand between 2019 and 2020, and a further 3.1% increase between 2020 and 2021, from 1 315 thousand to 1 355 thousand taxpayers (SET, 2022[54]). This increase was due partly to the automatic inclusion of micro-entrepreneurs requesting assistance through the Pytyvõ programme. However, it is important to note that the current simplified regimes established by the SET only cover businesses with a turnover up to PYG 2 billion (i.e., representing only micro-enterprises and a proportion of small enterprises according to the 2020 parameters for defining MSMEs).4

Easing registration for MSMEs is a key component of Paraguay’s enterprise formalisation efforts. The MSME law (Law 4457 of 2012) grants MSMEs a number of benefits depending on their categorisation as micro-enterprises, small enterprises, and medium-sized enterprises. These include access to credit, training and technology as well as tax exemptions in the case of micro-enterprises, and access to special labour and social security provisions. They also include the possibility for firms to hold simplified accounting and personnel management records. Registration as an MSME in the SUACE is certified by a certificate (cédula mipyme) which ensures that firms can access those benefits. The strategy therefore rests on firms registering as MSMEs, as it requires registration with the tax authorities as taxpayers and with the Ministry of Labour and IPS as employers. Once recognised as MSMEs, benefits from other institutions should be easily accessible.

Despite recent efforts, inconsistencies remain in accessing the benefits granted to formal MSMEs. Some inconsistencies have been removed through normative reforms. For example, until 2021, MSMEs were limited in their access to the special “raw materials regime”, which allows the import of raw materials for industrial production. Even though MSMEs paid reduced fees for inscription into the regime, a minimum import value (of USD 1 500 free on board [FOB]) was required, which excluded a number of small enterprises. This minimum import value was removed for registered MSMEs in 2021 by Decree 6141, expanding access to this regime. However, other inconsistencies remain. For instance, companies registered as an EAS cannot access the recently enacted simplified regimes SIMPLE and RESIMPLE, which have more limited eligibility conditions. RESIMPLE is only available to unipersonal firms, which excludes incorporated entities, while SIMPLE is intended to be used by larger unipersonal enterprises as well as production committees and a number of other specific forms of collective management of productive assets. Multiple and overlapping eligibility conditions could exclude a large number of self-employed or small entrepreneurs who would otherwise benefit from support measures, and create informational and bureaucratic barriers to access. This is particularly important given the high percentage of the population in self-employment, which implies a large universe of workers with low and volatile incomes, amounting to 38.9% of the employed population (Centrángolo, 2022[55]).

Social security coverage remains a challenge for MSMEs

Efforts to encourage formalisation through expanding access to social security remain partial. The voluntary affiliation of own-account workers and MSMEs to the pension system (Law 4933 of 2013) and the mandatory incorporation to the social security system of the IPS (Law 5741 of 2016) through a special system of benefits have been introduced, but with poor results. Throughout 2012-21, the share of informal workers in these segments of the economy remained relatively stable, highlighting the ineffectiveness of these formalisation strategies (Figure 3.11). Voluntary affiliation to the pension system remains unattractive for many domestic, own-account and MSMEs workers as it covers only a small range of benefits (old age, disability and death). At the same time, the lack of a decree regulating Law 5741 on affiliation to the IPS means that domestic, own-account and MSME workers lack access to social security. Moreover, in its current formulation, the special regime created by Law 5741 risks generating less benefits than the normal regime, thereby discouraging affiliation.

Figure 3.11. The share of informal workers has not decreased despite public formalisation strategies

Informal workers as a share of the group (non-agricultural employed population), 2012-21

Source: INE (2022[35]), Encuesta Permanente de Hogares 2012-2016, Encuesta Permanente de Hogares Continua 2017-2021. Cuarto trimestre. Serie comparable, www.ine.gov.py/default.php?publicacion=3.

Contribution schemes designed to promote formalisation must consider the specific conditions of independent and MSMEs workers including their volatile income and frequent changes of employment status and category. For example, flexible contribution schedules can encourage the affiliation of workers with irregular or seasonal incomes. Instead of a monthly payment, contribution schemes could include an option allowing for irregular contributions. Another option could involve simplifying the collection of taxes and social security contributions by bundling them together into a single payment or monotributo, as in the case of Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. Determining contributions based on the minimum salary also constitutes an obstacle as the level is too high compared to the salaries of the population (OECD, 2019[56]; OECD, 2018[57]). Finally, the obligation stipulated in Law 5741 requiring that independent workers and MSMEs register and obtain a MSME Identification Card (cédula mipyme) prior to affiliation to the Social Security Institute (IPS), may constitute and obstacle. An alternative measure could draw on information collected in the Unified Register of Informal Workers (Registro unificado de trabajadores informales), created for the emergency programmes Pytyvõ 1.0 and Pytyvõ 2.0, to assess eligibility.

Access to social security by micro-entrepreneurs has recently been regulated. In December 2023, the regulation of Law 5741 (Decree 933 of 2023) established a special social security regime for micro-entrepreneurs registered as such (Presidencia de la República del Paraguay, 2023[58]). The special regime grants rights akin to those of the general regime of social security. It requires contributions of 23% of the base, which is established by the highest salary paid to a dependent worker of the firm or the minimum wage. In practice, this corresponds to the contribution rate of the general regime with the exclusion of contributions dedicated to the anti-malaria programme (SENEPA) and the technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system (SNPP and SINAFOCAL). The regulation also establishes a gradual implementation path: social security registration will be voluntary for firms registered up to 2018 and will become compulsory for all as of July 2028.

Social protection coverage of MSME workers remains a significant challenge. The 25.5% rate of contributions in the general social security regime is often cited as a barrier to formalisation by MSMEs, which as a result have incentives to under-declare wages or rely on informal arrangements to avoid these contributions (Feal Zubimendi and Ventura, 2023[45]). The Government of Paraguay is working towards establishing a special regime for MSME workers to encourage their incorporation into social security. This reform target is part of a two-year policy co-ordination agreement signed by Paraguay with the IMF (IMF, 2022[59]). Further reforms to the social security system should also consider alternatives for access of independent workers to social security, depending on the success of the newly adopted micro-enterprise regime.

The productivity and formalisation agendas for MSMEs should be more tightly linked

Offering capacity-building and business services can also help firms formalise through increases in productivity. MSMEs tend to compensate for their low productivity with informal employment arrangements. Evidence shows that firms with greater value added per worker are therefore more likely to register their workers and keep them registered (Díaz et al., 2018[50]). This suggests that firms must reach a certain level of productivity to afford to formalise their labour force. The Vice Ministry of MSMEs offers a range of classes to MSMEs to develop a business plan and strengthen financial education. However, these projects are usually small, and the Vice Ministry does not have the capacity to monitor their impact. In 2022 the Vice Ministry also began to strengthen physical centres to attend to firms needs at the local level. These Centres of Support for Entrepreneurs (Centros de Apoyo a Emprendedores, CAE) have the objective of creating a decentralised network of support for MSMEs, providing guidance on formalisation, access to credit, access to new markets and trade fairs, and training opportunities (MIC, 2022[60]). They are developed at the local level in partnership with academia, the private and public sectors or business associations. MIC has recently started expanding its networks of small business support centres with the implementation of the Small Business Development Centre (SBDC) model in Paraguay, with a first centre opening in August 2023. Two of the particularities of the model are the importance given to one-to-one coaching and mentorship alongside more traditional training activities, and the existence of long-term partnerships with local teaching institutions, governments, and private sector bodies.

Business chambers play a crucial role in the provision of services to MSMEs, and partnerships with this sector should be nurtured. As highlighted during the COVID-19 crisis, business chambers and associations play an important role in channelling claims and proposals to the government. Business chambers also provide valuable services to firms and recent years have seen improvement in their organisation and dialogue with the government. For instance, some business associations are responsible for managing CAEs, in partnership with the MIC. The Paraguayan Industrial Union (UIP), the apex business organisation for industry, is an implementing partner for a number of support programmes, including the SBDC programme, the ILO project My SME Complies (Mi Pyme Cumple), and programmes like Mipyme Compite, which offer business development and advisory services. However, it is also important for policy makers to extend their dialogue and reach beyond traditional business and employer structures to connect with informal business membership organisations and coalitions (ILO, 2016[61]).

Policies promoting business linkages can also provide incentives for MSMEs to become formal by accessing new markets or business opportunities. Formalisation via integration into the value chains of larger enterprises can often result in better market positioning, both nationally and regionally, as a result of linkage with a multinational enterprise (MNE), technology transfers by MNEs leading to greater value added of MSMEs’ products and innovation, and better enterprise management due to the adoption of administrative controls and techniques. While there is no one-size-fits-all policy, better business processes and firm management can result in higher formalisation (ILO, 2016[62]). Local and regional value chains can also help increase productivity and have positive effects on the formalisation of MSMEs. However, an active strategy on the part of the central government is needed to facilitate the insertion of MSMEs as vendors of value chains. Such a strategy should seek to: i) promote demand; ii) reduce supply-side gaps and position MSMEs appropriately in markets; and iii) improve articulation with public, private and civil society actors to achieve greater impact (UNDP, 2023[63]). Peru has made good progress on the strategic planning front, connecting the development of MSMEs with the broader productive system. As part of the Competitiveness Agenda 2014-2018, the Peruvian government developed a Supplier Development Programme and Cluster Support Programme. The main aim is to improve the quality and productivity of MSME suppliers, in order to ensure stronger ties with their respective value chains by ensuring that suppliers acquire the necessary competencies and skills required by the companies driving the process, in terms of product quality, punctuality of delivery, costs, inputs and services, among others. This results in productive development for both suppliers and client companies (CNC, 2015[64]).

Local governments and institutions can play a strategic role in strengthening MSMEs by establishing clusters of innovative businesses in regions with distinct comparative advantages. The effectiveness of such initiatives can be further boosted through co-ordinated efforts between national and local governments, considering the geographical and economic distances between businesses (Rodríguez-Clare, 2005[65]). Policy makers can glean valuable insights from international collaborations and the experiences of countries such as Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and the Caribbean, where cluster initiatives have proven particularly beneficial (OECD et al., 2023[66]). Looking beyond the LAC region, Germany and Italy offer noteworthy examples with their successful “industrial districts”, underscoring the significance of explicit policies in Europe that foster business collaboration and support an entrepreneurial culture (ECLAC, 2013[67]).

Paraguay has reformed its procurement law to promote the participation of SMEs in public procurement processes. The 2022 reform of the procurement law (Ley de suministro y contratataciones públicas) provides for 20% of public procurement to be reserved for SMEs, fulfilled gradually within the space of five years. It also allows for smaller tenders to be opened exclusively to MSMEs. However, frequent delays in payment limit the ability of MSMEs to participate in such public tenders, due to their often-limited liquidity.

Unlike neighbouring countries, no supplier development programmes exist with the private sector in Paraguay. In comparison, the Supplier Development Programme of the Chilean Corporation for Production Promotion (CORFO) focused on the creation and consolidation of stable subcontracting relationships between a long steel and wire enterprise and its suppliers. Half funded by the Supplier Development Programme, the initiative aimed at reinforcing business linkages and had a duration of three years during which SMEs were accompanied by capacity-building opportunities to increase their management skills, entrepreneurship, accounting, IT and software, inventories and sales, among others. In the first year of the initiative’s implementation, the level of compliance among participating SMEs was approximately 25% on average. This further increased to 56% and finally culminated in 70%, demonstrating increased positive impacts regarding the process of formalisation (ILO, 2016[62]; Stucchi, 2012[68]).

Access to finance remains a challenge for MSMEs in Paraguay but improved during the COVID-19 crisis

The framework to support access to financing by MSMEs is relatively recent and gaps remain. Access to financing is a key problem for MSMEs as their risky creditor profile exposes them to low credits and high interest rates. Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, only a small number of MSMEs were able to access credit, with the minimal participation of public credit institutions (MIC, 2019[46]). The Guarantee Fund for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (FOGAPY) was created in 2016 and subsequently regulated in 2017, but its initial USD 8 million capitalisation was not sufficient to attend to the needs of MSMEs, especially medium-sized enterprises (Santander, 2017[69]). In addition, the lack of formal supervision and regulation of certain financial institutions, such as microfinance institutions, payment providers and remittance providers, which tend to cater more to low-income groups and MSMEs, exposes the latter to higher risks (World Bank, 2014[70]). The lack of formalisation of many MSMEs also prevents them from accessing financing from formal credit institutions and forces them to resort to non-bank intermediaries.

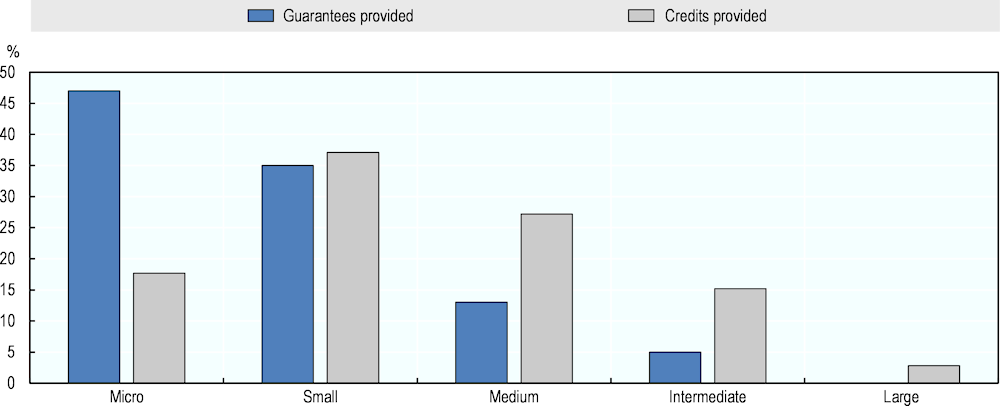

Public policies supporting access to finance for MSMEs improved during the COVID-19 crisis. Strengthening of the resources available to FOGAPY and the increase in guarantees provided to the most vulnerable sectors of the economy played a key role in the pandemic response. In terms of the number of guarantees granted, micro-enterprises benefited the most from the strengthening of FOGAPY during this period (Figure 3.12). Indeed, a strengthened FOGAPY is an important legacy of the COVID-19 response. As of August 2023, FOGAPY had granted 41 238 guarantees underpinning USD 1.09 billion in loans. Evidence from EU countries shows that credit guarantees are an important counter-cyclical policy tool. By reducing credit risk for partner institutions, they dampen market failures in SMEs’ access to credit, and support technology, innovation, growth and employment (Brault and Signore, 2019[71]). The proposal to introduce a law on movable collateral (garantías mobiliarias) as part of the Recovery Plan could also further improve financial inclusion and access to credit for MSMEs which often do not own real estate.

Figure 3.12. Guarantees provided by FOGAPY benefited micro-enterprises the most

Guarantees granted by FOGAPY by size of firm, March 2020 – December 2020.

Source: AFD (2022[72]), Reporte de Rendición de Cuentas, Garantías Emitidas por el Fondo de Garantías del Paraguay.

Working with non-bank financial intermediaries also expanded the reach of development banks towards MSMEs. During the pandemic, a fiduciary fund was put in place to channel financial resources to MSMEs with credit for operations and payroll. While AFD operates primarily as a second-tier bank with the banking sector, the funds were channelled through co-operatives and non-bank financial intermediaries, who typically have greater ability to reach MSMEs.

Financial literacy, management training and business advisory services are crucial for formalisation to lead effectively to access to credit for MSMEs. While formalisation is a precondition for access to bank credit, it is not sufficient. As many as 60% of micro-enterprises and 35% of small-sized enterprises had no active financing from banks as of end March 2023, according to the BCP. Financial literacy is an issue, as 55% of the population has a savings account, and only 7% of micro and small enterprises have a bank account, the majority relying instead on savings and credit co-operatives or non-bank financial intermediaries. Self-exclusion is also an important phenomenon. The lack of formalisation prevents these companies from complying with the requirements demanded by financial institutions to access loans. Surveys reveal that 22% of MSMEs that have not obtained credit believe they do not meet the necessary requirements to obtain financing. This self-exclusion is directly linked to MSMEs’ perception of their own ability to meet the criteria for accessing credit. Factors such as high interest rates, difficulty in meeting the requirements and lack of confidence in their ability to repay loans stand out as elements influencing this self-perception (Monsberger, 2022[73]). Business advisory and support services allowing firms to keep appropriate books and plan future operations and their financing are an important step in making formalisation pay for MSMEs, both in terms of better management and access to credit.

Digitalisation for inclusive growth

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the global digital transformation. As a result of the pandemic, school classes moved online and teleworking from home became the norm wherever possible. In this context, many firms adopted digital business models to maintain operations. Jobs, education, health, government services and even social interactions became increasingly dependent on digital technologies, with Internet traffic increasing up to 60% in some countries soon after the outbreak. Looking ahead, the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the potential of digital technologies and it is likely that the resulting changes and advances in digitalisation, including telework, e-commerce, e-health and e-payments, will persist (OECD, 2020[74]).

The pandemic heightened the importance of adopting and prioritising policies that support digitalisation and ensure widespread and trustworthy digital access and effective use. However, while digitalisation creates new opportunities, countries lagging behind risk forgoing opportunities for productive investment, the development of new sectors, and economic growth and development. The COVID-19 pandemic not only accelerated digitalisation, it also accentuated gaps in digital infrastructure, access and skills, both within and across countries. In this context, policies supporting digitalisation have assumed increasing importance, notably investment in digital infrastructure to ensure high-quality and affordable connectivity, skills to enable people and firms to use increasingly sophisticated digital solutions, and measures to close persistent digital divides as well as those newly emerged as a result of the pandemic (OECD, 2020[74]).

Supporting and accelerating digitalisation is of particular importance for Paraguay given the opportunities the digital services sector presents for the country. A major advantage of digital services industries is the absence of transport costs. As noted earlier, Paraguay is a landlocked country, and as a result of infrastructure gaps, such transport costs are relatively high. The country also relies significantly on its river network for merchandise transport and international trade; however, the feasibility of river-based transport can be affected by extreme weather events such as the recent drought (OECD, 2018[22]). The frequency of such weather events and the risks associated with river-based transport are increasing in the context of climate change, which makes digital services a very attractive sector for further development.

Paraguay has already adopted digitalisation policies but lags behind other countries in the LAC region in terms of digitalisation

Paraguay has already put in place a national digital strategy. The National Development Plan: Paraguay 2030 and the National Digital Agenda are the main reference documents for the country’s development and digital policies. The Digital Agenda aims to achieve digital transformation through: i) better connectivity, ii) digital government development, iii) a digital economy to make the country more competitive, and iv) institutional strengthening, including through cybersecurity. Digital transformation policies link directly to the development plan’s four overarching goals: poverty reduction and social development, inclusive economic growth, deeper inclusion in the international economy and institutional strengthening (STP, 2021[75]). Created in 2018, Paraguay’s Ministry of Information and Communication Technologies (MITIC) is the technical entity responsible for the formulation and implementation of public sector information, communication and technology (ICT) plans and projects. It also functions as the administrative authority responsible for social and educational aspects of the inclusion, innovation and implementation of technologies. MITIC emphasises the importance of administering the communication infrastructure and promotes the interoperability of public sector systems (OECD et al., 2020[76]).

Paraguay’s level of digitalisation is intermediate, lagging behind other LAC countries in terms of Internet use and broadband penetration. The share of Internet users in Paraguay has increased rapidly from 19.8% of the population in 2010 to 77% in 2021. This trend aligns with the LAC average but remains below the OECD average and that of neighbouring countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay (Figure 3.13, Panel A). Mobile broadband penetration is 25% lower than in the LAC region on average. Fixed broadband penetration has increased notably in the past decade but is only 60% of the LAC average (Figure 3.13, Panel B) (OECD, 2020[74]).

Figure 3.13. Potential exists to further improve digitalisation in Paraguay

Note: Panel B. Active mobile broadband subscriptions refer to the sum of standard mobile broadband and dedicated mobile broadband subscriptions to public Internet. They cover actual not potential subscribers, even though the latter may have broadband‑enabled handsets.

Source: A. World Bank (2024[5]), World Development Indicators (database), https://data.worldbank.org/ ; B. OECD et al. (2020[74]), ITU (2024[3]), ITU DataHub (database), International Telecommunication Union, Geneva, https://datahub.itu.int/ and ECLAC (2024[77]) Cepalstat (database), https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/dashboard.html.

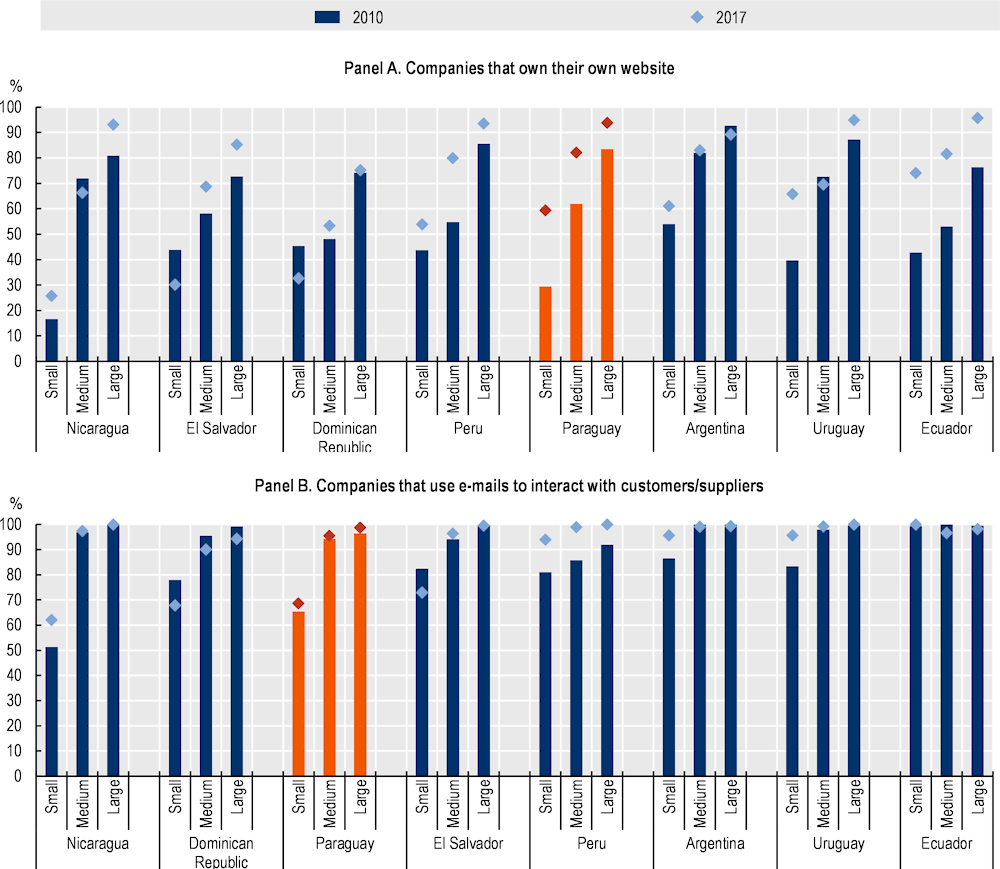

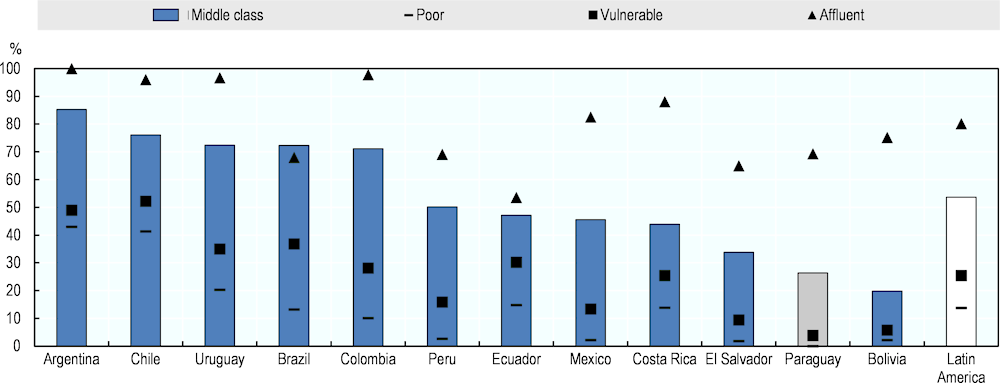

The diffusion of digital technologies remains uneven in Paraguay. Among businesses, diffusion remains especially low for small firms, in line with the regional trend (Figure 3.14). In 2017, 93.8% of large companies, but only 59.3% of small companies, owned their own website in Paraguay. Similarly, 98.7% of large companies used emails to interact with customers, but only 68.6% of small companies (2017) (Figure 3.14). Among households, 87.5% of individuals in the highest quintile of the income distribution were using the Internet in 2017 (compared to 75% in the LAC region on average), but only 48.5% of individuals in the lowest quintile (compared to 36.6% in the LAC region on average). The income divide in Internet usage is larger in Paraguay than in LAC countries with comparable levels of overall Internet usage (OECD, 2020[74]). Only 3.8% of vulnerable students and 0% of poor students enrolled at primary school have access to a computer with Internet access at home, compared to 69.3% of affluent students (Figure 3.15). Paraguay must focus on closing these digital divides to ensure that the benefits of digitalisation are shared equally.

Figure 3.14. The diffusion of digital technologies remains especially low for small firms

Use of basic digital technologies by firm size in selected Latin American and Caribbean countries, 2010 and 2017.

Source: OECD et al. (2020[76]) based on World Bank (2020), Enterprise Surveys (database), www.enterprisesurveys.org/; Correa, Leiva and Stumpo (2018), “Avances y desafíos de las políticas de fomento a las mipymes”, Mipymes en América Latina: Un Frágil Desempeño y Nuevos Desafíos para las Políticas de Fomento.

Figure 3.15. Access to digital equipment remains low among students in Paraguay, in particular among the most vulnerable

Share of students enrolled in primary education with an Internet-connected computer at home by income group, 2018 or last available year.

Note: The regional average is a simple average. “Poor” are those living with less than USD 5.5 per capita per day (PPP 2011), “vulnerable” those living with USD 5.5 to USD 13 per capita per day (PPP 2011), “middle‑class” those living with USD 13 to USD 70 per capita per day (PPP 2011) and, “affluent” those living with more than USD 70 per capita per day (PPP 2011).

Source: OECD et al. (2020[76]) based on Basto‑Aguirre, Cerutti and Nieto Parra (2020[78]).

Accelerating digitalisation in Paraguay requires investment in digital infrastructure, enhanced digital skills and support for innovation