This chapter formulates policy recommendations to facilitate the adoption of a circular approach in North Macedonia’s biomass and food sector, with a particular emphasis on bioeconomy principles. It gives an overview of the current context in this sector and its underlying policy framework, identifies key areas for potential improvement, and presents specific policy recommendations based on relevant international best practices.

A Roadmap towards Circular Economy of North Macedonia

6. Circular transition for biomass and food in North Macedonia

Abstract

The circular bioeconomy in the biomass and food system

The circular bioeconomy builds on the concepts of bioeconomy and circular economy. The bioeconomy covers all sectors and systems that rely on biological resources: animals, plants, microorganisms and derived biomass, including organic waste, their functions and principles. The bioeconomy includes and interlinks land and marine ecosystems and the services they provide; all primary production sectors that use and produce biological resources (agriculture, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture); and all economic and industrial sectors that use biological resources and processes to produce food, feed, bio-based products, energy and services (European Commission, 2018[1]). The circular bioeconomy encompasses economic activities in which biotechnology contributes centrally to primary production and industry. At the same time, waste materials are drastically reduced, and waste is recycled, remanufactured and kept in the system for as long as possible (Kardung et al., 2021[2]).

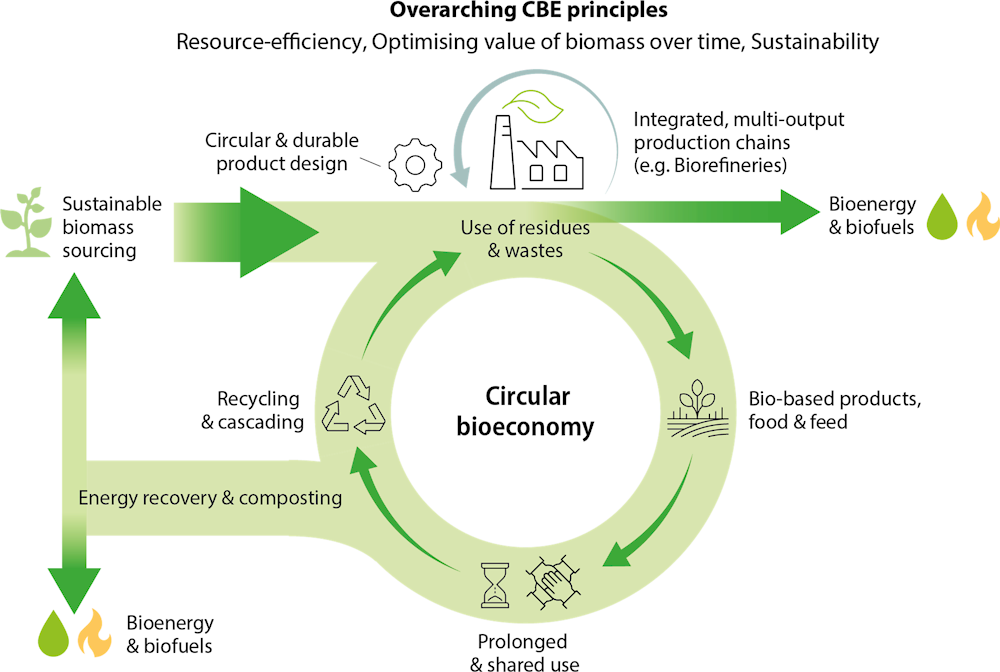

Figure 6.1 summarises the central elements of the circular bioeconomy (based on Stegmann, Londo and Junginger (2020[3])). A closer look at the life cycle along the biomass and food system helps to identify numerous opportunities for the circular bioeconomy:

Primary production. This refers to the sustainable management of land and forests, and efficient use of resources and inputs in agricultural and forestry management practices. The sustainable management of agricultural land and forests implies a fair and balanced distribution of land, water, biodiversity and other environmental resources between various competing claims, to secure human needs now and in the future. Various bio-based sources from all life cycle stages, such as biomass wastes and residues, can be used at this stage as feed, fertilisers, soil conditioners or for other purposes without pre-treatment.

Industrial processing and distribution. Circularity can be enhanced at the level of both design, processing and distribution. The specific design of a product and production process can be crucial in ensuring the product has a longer lifetime as well as the potential to reduce waste and increase recycling, the use of regenerative materials and end of life (e.g. by ensuring biodegradability). This stage also includes the bio-based production of processed food, feed, fertilisers, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, cosmetic compounds, biomaterials, packaging processes and delivery to the consumer, and reprocessing of biomass at its highest material value before its conversion into bioenergy (so-called cascading). Packaging and product distribution can be geared towards greater circularity and less food waste, including by ensuring recyclability and limiting the overall environmental impact.

Consumption. Three broad strategies can be identified at the core of this stage: 1) changing consumption patterns; 2) preventing waste; and 3) prolonging the use of products either through cascading use, reuse or recycling. This is particularly relevant for the consumption, use and disposal of food and bio-based products.

End-of-life. This stage refers to the treatment of materials and products when they become waste. This includes residues and “bio-waste” generated at different stages of the agricultural and forestry supply chains as well as waste from processing, consumption and bioenergy production stages. The circularity of waste from biomass and bio-based products means improving waste sorting to facilitate use and recycling, improving recycling technologies and processes, and extracting valuable chemicals as components from processing. In addition, biomass and organic waste are important feedstocks for bioenergy production. However, energy recovery should only be used when higher options in the waste hierarchy (waste prevention, waste reduction, reuse and recycling) cannot be achieved.

Figure 6.1. The circular bioeconomy and its principles

Motivations for the selection of biomass and food as a key priority area of the Roadmap

The biomass and food sector has been selected because of its relatively high economic and policy relevance, and high circularity and decarbonisation potentials for North Macedonia.

The sector contributes up to 10% of the national gross value added in primary production, or around 15% when combined with the food industry (Ministry of Education and Science, 2023[4]). Agriculture alone also generates around 10% of employment in the country, although jobs are mostly low-skilled and low-waged, mainly due to the prevalence of subsistence farming. The country has a long and well-developed tradition of producing a wide range of agri-food products, with established internal and external export links. Primary agriculture and the food industry have always been strategic export sectors for North Macedonia, with exports of agricultural and food products in 2021 constituting 9.6% of the country’s total exports, mainly tobacco, lamb meat, fresh and processed vegetables and fruits, wine, and confectionery products (Invest North Macedonia, 2022[5]). Moreover, organic production has grown in recent years due to government support, with agricultural area under organic farming having more than tripled between 2015 and 2022, although it still represents less than 2% of total cultivated area (Eurostat, 2023[6]; MAKSTAT, 2023[7]).

The area also has high policy relevance, in particular as part of the National Strategy on Agriculture and Rural Development (2021-2027), whose objectives include improving the competitiveness and sustainability of the agriculture sector, notably through ecological practices in production processes. Such processes are supported by programmes implemented by the Agency for Financial Support in Agriculture and Rural Development. Biomass and food is also one of the four areas to be addressed in the Smart Specialisation Strategy of North Macedonia for the period 2023-2027. In addition, the National Waste Prevention Plan (2022-2028) underscores the necessity to mitigate resource loss and address environmental impacts like soil contamination and unsustainable land use caused by landfilled waste. The Industrial Strategy (2018-2027) also aims to boost food industry exports by supporting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in export procedures and documentation, aligning with the broader development of a bioeconomy. Moreover, this area, especially food waste and bio-waste, has several obligations and targets under European Union (EU) legislation (for instance, EU member states are obliged to separately collect municipal bio-waste as of 1 January 2024), which North Macedonia will eventually have to comply with due to its status as an EU accession candidate.

The circularity and decarbonisation potential of the biomass and food sector is also high, as the sector can make a significant contribution to environmental protection and climate change mitigation over time by maintaining the value of bio-based products, materials and resources in the economy for as long as possible. Organic waste represents around 45% of the municipal waste stream (Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning, 2021[8]) and is a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Methane, generated from the decomposition of organic waste, stands out as the global solid waste sector’s largest contributor to GHG emissions (Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning, 2021[9]). This is particularly noteworthy considering that the waste sector as a whole contributed to 5.6% of all GHG emissions in North Macedonia in 2019 (Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning, 2023[10]). In addition, biomass represents an opportunity for North Macedonia by providing additional natural resources for the economy and products, and by closing the biological cycle of biodegradable materials. The food system is one of the most frequently targeted priority areas in national circular economy strategies due to its high land, water and energy consumption and large waste production (Salvatori, Holstein and Böhme, 2019[11]).

Overview and approach for selecting the proposed policy recommendations

The approach for selecting the proposed policy recommendations for the biomass and food priority area is similar to that used for the other sectoral priority areas (construction, textiles and mining/metallurgy). The recommendations advocate for a life cycle approach with a focus on design, production, (re)use and end-of-life stages. This is because the entire life cycle, from primary production of biomass to its waste management, can create significant environmental pressures affecting the ecosystem’s health and economic growth. The proposed measures also aim to bridge the gap between the current situation in North Macedonia and current and expected obligations and targets stemming from the national and EU legislation. For example, aligned with the National Waste Prevention Plan, reduction targets for bio-waste sent to landfills are set at 25% by 2026, 50% by 2031 and 65% by 2034 compared to 1995 levels. These measures extend to reducing food waste generation across primary production, processing, manufacturing, retail and food distribution, aligning with SDG 12 for halving per capita food waste by 2030. The proposed measures also aim to create synergies and complementarity with North Macedonia’s Smart Specialisation Strategy and to tap the high circularity potential this area offers. It is proposed that the roadmap focus on improving the following four key areas:

1. managing agricultural waste and bio-waste and closing their biological cycle

2. more sustainable consumption of food

3. funding and technical support for circular bioeconomy projects

4. stakeholder engagement and collaboration, and awareness raising.

Table 6.1 provides an overview of the proposed policy recommendations to support these four key areas.

Table 6.1. Overview of the proposed policy recommendations in the priority area biomass and food for North Macedonia

|

Short term |

Medium term |

Long term |

|

Establish a working group on a circular bioeconomy and improve multi-stakeholder collaboration |

Introduce and scale up infrastructure for separate collection of bio-waste |

Provide funding and technical support for circular bioeconomy projects |

|

Raise awareness, education and skills on food waste prevention, separation of bio-waste at source and composting as well as the circular bioeconomy in general |

Promote green public procurement of food and catering services |

Strengthen the regulatory framework supporting the use of compost and digestate in agriculture, with a focus on a quality assurance system |

|

Consider tax incentives to support food donations |

Support investment into small-scale industrial composting and anaerobic digestion facilities to treat agricultural waste and municipal bio-waste |

Key proposed policy recommendations

1. Improve the management of agricultural waste and bio-waste and close their biological cycle

A number of steps are necessary to improve the management of agricultural waste and bio-waste and close their biological cycle. It is recommended that this roadmap focus on three:

First, regarding bio-waste, adequate infrastructure for separate collection of bio-waste needs to be put in place and especially households need to learn how to separate their bio-waste.

Second, there needs to be sufficient composting and anaerobic digestion capacity to deal with agricultural waste and the collected bio-waste domestically.

Third, it will be important to close the biological cycle of agricultural waste and bio-waste by circulating these wastes back into the soil in the form of compost and digestate.

North Macedonia will need to introduce and scale up infrastructure and incentives for separate collection of bio-waste in the medium term. As North Macedonia has not yet introduced a mandatory separate collection of municipal bio-waste, municipalities will need to ensure that adequate infrastructure for separate collection of bio-waste is in place and that there are effective incentives for households to separate it. There may be fewer incentives for municipalities to put such infrastructure in place if bio-waste is cheaply landfilled or incinerated. Similarly, households will be less likely to separate their bio-waste if it is not easy to do or is more costly.

To improve the infrastructure for the separate collection of bio-waste, North Macedonia must ensure regular collection schedules, provide appropriately sized containers and bags, and establish an appropriate distance to waste facilities or adopt “door-to-door” collection. Regular and frequent collection will reduce issues with biodegradation (such as odours, flies or leaks) and preserve the value of the waste, which diminishes over time. Providing small kitchen caddies or bags to each household is particularly relevant for those residing in apartment buildings. Moreover, implementing measures such as maintaining an appropriate distance to the containers during kerbside collection or facilitating door-to-door collection of bio-waste can significantly enhance the convenience of separating bio-waste for households. North Macedonia could enhance its municipal bio-waste collection by implementing a door-to-door collection system. This approach has been successfully implemented in the European Union, notably in Italy, which has achieved near-complete sorting of kitchen waste in Milan using kitchen caddies provided to every household. North Macedonia may opt to limit the door-to-door collection to specific premises. For example, since 1 January 2023, the Slovak Republic mandates the separate door-to-door collection of bio-waste for households residing in single-family homes (amendment to the Ministerial Decree of the Slovak Ministry of Environment No. 371/2015). The objective is to encourage municipalities and households to separate their waste.

The government and municipalities can also enhance the implementation of economic incentives to encourage better sorting and separation of bio-waste. This can be achieved by introducing landfill taxes, and/or “pay-as-you-throw” systems, where households are charged according to the amount of mixed municipal waste they produce.

North Macedonia will need to support investment in industrial composting and anaerobic digestion facilities to treat organic agricultural waste and municipal bio-waste domestically. If agricultural waste and bio-waste cannot be prevented or used in another way (e.g. for human consumption or valorised for feed or other bio-based applications), it must be treated or disposed of. Organic agricultural waste and bio-waste can be treated through processes like composting (for compost) and anaerobic digestion (for digestate and biogas) (once waste is prepared for such processes), as these products can be used on land or as an energy source. Bio-waste and forestry waste can also be incinerated for energy recovery. From a circular economy perspective, composting needs to be prioritised over anaerobic digestion, and anaerobic digestion over energy recovery. The EU Landfill Directive also requires that biodegradable municipal waste be diverted from landfills. While reported composting rates are currently non-existent (they dropped from 0.4% in 2015 to 0% in 2020 (World Bank, 2022[12])), municipalities have undertaken a few pilot projects to encourage composting, although they remain marginal. Such projects include the conversion of waste and wastewater into compost and biogas in the municipality of Kocani and the establishment of composting stations in the municipality of Resen. However, it should be noted that home composting is not included in reported figures, hence actual composting rates may be higher. To ensure that adequate investments are made in composting and anaerobic digestion capacities, countries often strengthen the financial support for such facilities. This is often achieved by allocating more funds to this area within existing programmes (in EU countries these are often EU Structural and Cohesion Funds) and making them more accessible (e.g. to additional actors). North Macedonia could follow this example and use these programmes: IPA III Agriculture and Rural Development (IPARD III) 2021-2027, Horizon Europe 2021-2027, and the Circular Bio-based Europe Partnership operating under Horizon Europe. Bio-waste treatment could also be integrated as part of existing or future waste management programmes funded by international development co-operation partners (see Annex B). Increasing composting and anaerobic digestion capacities must go hand-in-hand with separate collection of bio-waste to ensure that the compost/digestate is of high quality and that contamination with heavy metals and impurities is limited. Moreover, measures supporting the use of compost and digestate in agriculture also need to be in place to ensure that these products that enhance soil quality and can close the biological cycle of these wastes are used. Often compost that is not used (in agriculture or at home) tends to end up in landfills.

To encourage the use of compost and digestate in agriculture, North Macedonia will need to strengthen its regulatory framework for composting and anaerobic digestion, with a focus on inspections and developing a quality assurance system for compost in the long term. Encouraging the development of bio-based alternative products such as those related to biofertilisers and biostimulants is also an objective under North Macedonia’s Smart Specialisation Strategy. Compost and digestate can improve soil quality but they also provide an opportunity to use agricultural waste and bio-waste for other applications and for climate change mitigation (compost stores more CO2 than the atmosphere and terrestrial vegetation combined (Gilbert, Ricci-Jürgensen and Ramola, 2020[13]). Box 6.1 presents examples of best practices of leading countries such as Austria, Germany and Slovenia. An optimal legal framework needs to define requirements not only for the quality of the final product (e.g. through a quality label for compost) but also for the quality of inputs and the production processes, as inputs and the technological processes are the most important determinants of the final quality of the compost.

Box 6.1. Examples of regulatory frameworks to support the use of compost and digestate

Austrian waste legislation on compost products

Since 1995, the Austrian Bio-waste Ordinance (FLG No 68/1992) requires the source separation and biological treatment of organic waste (primarily through composting and anaerobic digestion), while the Compost Ordinance (FLG II No 292/2001) established end-of-waste regulation for compost produced from defined organic wastes, as well as monitoring and external quality assurance obligations. In Austria, the aim has been to avoid recommending the imposition of excessive technical obligations to preserve the well-established decentralised, mostly on-farm, composting systems. Since the early 1990s, this has been widely recognised as a sustainable bio-waste recycling system. Compost can be classified and marketed as a product in Austria provided it meets certain quality criteria and has been processed from specific input ingredients. The minimum organic matter level of 20% is one of the most important requirements, as compared to artificial or dredged soils having substantially lower organic matter concentrations.

Slovenian Decree on the Treatment of Biodegradable Waste and the Use of Compost or Digestate

Slovenia became one of the first countries to introduce compulsory operations in the treatment of biodegradable waste and conditions for its use, as well as conditions for placing treated biodegradable waste on the market. The legislation on the recovery of biodegradable waste and the use of compost and digestate lays down, among others, the conditions for designing and operating biogas plants (e.g. applying to an environmental permit), the types of biodegradable waste that can be treated (listed in Annex 1), specific requirements for composting and anaerobic digestion, and quality control (first or second quality class in accordance with Annex 4) of compost and digestate. The regulation prescribes that digestate must be further composted following anaerobic degradation (Article 12) and that a quality control of the compost or digestate must be carried out by a company, public institution or private individual (Article 14).

Germany’s quality assurance system for compost and digestate

Since 1989, Germany has successfully run a quality assurance system for compost and digestate made from bio-waste, which comprises a body (the Bundesgütegemeinschaft Kompost e.V., BGK) qualified to oversee the quality of compost and digestate and award a quality label. This quality assurance organisation was founded by composting plant operators in 1989, following the increasing uptake of separate bio-waste collection by German municipalities throughout the 1980s. BGK is an independent association that participates in the European Compost Network (ECN) and one of four national quality assurance organisations in the European Union to have been awarded the ECN Quality Assurance Standard conformity label. It implements the quality standards which are set at the national level by the German Institute for Quality Assurance and Certification. The costs of running such quality assurance standards, including the process of on-site audits and sample analyses for quality assurance, are indirectly financed by waste management fees.

Sources: Adapted from OECD (2022[14]); European Commission (2021[15]); Ministry for Agriculture and Forestry, Environment and Water Management of Austria (2009[16]); European Commission (n.d.[17]); Dollhofer and Zettl (2018[18]).

According to an analysis carried out by the European Environment Agency, 24 of the countries surveyed have national standards for compost quality, either in legislation, as stand-alone standards or under development, while a few countries/regions have also developed quality standards for digestate (e.g. Denmark, Flanders [Belgium], Germany, Sweden and the United Kingdom) (EEA, 2020[19]). A strengthened quality assurance system for compost (and digestate) would reassure farmers when using these products on their agricultural land, as these products need to be of good quality in order to be used as soil improvers or fertilisers (EEA, 2020[19]). The ECN has also published guidelines (ECN, 2022[20]) to help EU member states implement separate collection of bio-waste and improve the quality of compost for agricultural use.

2. Moving towards a sustainable consumption of food

A variety of policy instruments can support the sustainable consumption of food. This may include food waste prevention, awareness raising, education measures and economic incentives (for example pay-as-you-throw household charges) that incentivise consumers and households to decrease the amount of food waste they generate. There are also circular business models that could be supported which develop digital tools to sell or donate surplus food from supermarkets and restaurants. It may also include making food and catering services more sustainable through green public procurement (GPP) and strengthening incentives for the food industry to make food donations. It is suggested that this roadmap focus on two economic instruments: 1) tax incentives for food donations to support a more sustainable consumption of food in North Macedonia; and 2) GPP of food products and catering services. These instruments have been widely and successfully implemented across EU member states and could be highly impactful in North Macedonia.

North Macedonia should consider introducing tax incentives to support food donations in the short term. In line with the waste hierarchy, the top priority is waste prevention, followed by waste reduction, then reuse, recycling, energy recovery and finally landfilling. In the case of food waste, if food surpluses cannot be avoided, the second best option is to prioritise food redistribution for human consumption before food is directed towards animal feed applications and lower down the waste hierarchy (OECD, 2022[14]). Food redistribution for human consumption can be facilitated by food donations. Although the primary objective of food donation is not to reduce food waste but to ensure the availability of good and healthy food to people from vulnerable groups, the potential to redirect unsold food to these end consumers is consistent with food waste prevention objectives. In North Macedonia, the Law on Donating Surplus Food Waste is currently undergoing final consultations, foreseeing collaboration with the food industry and the non-governmental sector on promoting food waste reduction strategies directed at consumers. The development of the law was supported by the association “Let’s do it Macedonia”, which has been active in preventing food waste in North Macedonia and has created a web platform connecting businesses with non-governmental organisations to redistribute surplus food. The Macedonian National Waste Prevention Programme includes tax incentives for encouraging businesses to donate food. Box 6.2 outlines the most common tax incentives for food donations. When introducing such tax incentives, it is important to consider: which foodstuffs and of which value are eligible for donations? Is foodstuff for which the best before date has passed eligible for donation? Who can receive donated food (only registered charitable organisations or others)?

Food banks and distribution channels also need to be in place. Present for more than 12 years, Food Bank Macedonia has been actively involved in redistributing food waste to aid vulnerable populations across North Macedonia, establishing localised branches in the process. The organisation received assistance from the European Union to enhance its food aid system, playing a crucial role in activities during its #WeStandTogether COVID-19 campaign. Through this initiative, Food Bank Macedonia successfully delivered over 35 tonnes of food to more than 1 500 families in 20 municipalities (Delegation of the European Union to North Macedonia, 2022[21]).

The recommended EU Guidelines on Food Donation and redistribution (European Commission, 2017[22]) provide information on how to interpret and apply relevant legislation related to food donation. Moreover, it is recommended to use tax incentives for food donations rather than regulatory instruments, for example mandatory donations for specific businesses and foodstuffs. This is because mandatory donations may lead to additional challenges, such as logistical problems for both retailers and charitable organisations, as the receiving organisations need to have sufficient organisational and operational capacity to process an increased amount of donations (European Commssion, 2020[23]).

Box 6.2. Examples of tax incentives to support food donations

Reduced or exempt value-added tax (VAT) on food donations. Some countries (e.g. Austria, Denmark, Germany, Italy and Slovenia) consider the monetary value of the donated food to be low or zero, akin to its value when close to its “best before/use by” date, equating to a very low or no VAT payable on the donated food (irrespective of the original value of the food).

Corporate tax credits on food donations. For example, in France, 60% of the net book value of donated food can be claimed as a corporate tax credit that can be deducted from the corporate revenue tax. The amount is 35% in Spain.

Enhanced tax deduction, where donors can deduct more than 100% of the value of the food at the time of donation. For example, Portugal has an enhanced tax deduction of up to 140% in place if the food is used for a social purpose and limited to 0.008% of the donor’s turnover.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2022[14]), European Commission (2017[22]); EU Platform on Food Losses and Food Waste (2019[24]).

North Macedonia should also use public authorities’ purchasing power through GPP to promote sustainable consumption of food in the medium term. The GPP of food and catering services is a well-established intervention, playing an important role within public procurement in the European Union (Box 6.3). GPP schemes can target different levels of governance (national, regional and local), food products, environmental criteria as well as life cycle phases of public procurement (Neto and Gama Caldas, 2017[25]). They can also incentivise the sustainable production of food, as green criteria tend to be applied throughout the life cycle, including related to food production (for example, the provision of organic food), distribution and packaging (preference for local production and sustainable packaging) as well as food waste prevention (through, for example, meal planning). As mentioned in Chapter 4, the Law on Public Procurement (2019) includes relevant provisions on GPP, and the corresponding Action Plan 2022 successfully achieved its measure to create a GPP manual with a catalogue of good practices for potential suppliers. North Macedonia also plans to introduce mandatory GPP criteria in procurement bids (National Plan for Waste Management 2021-2031). However, the country will need to scale up the use of GPP, as outlined in Chapter 4. It may want to start focusing on the sectors targeted in this roadmap, including the procurement of food products and catering services. This could be achieved by increasing public authorities’ understanding of how to implement GPP in this area and by raising awareness about its benefits. The authorities could also develop guidance on GPP methodology or training materials for public authorities and use the EU guidance and EU GPP criteria for food, catering services and vending machines as an example (European Commission, 2019[26]).

Box 6.3. Green public procurement of food products and catering services in the European Union

According to a recent study by the Joint Research Centre, the purchase of food products and catering services plays an important role within public procurement. Many meals are provided by contracted catering companies to public services, including the education sector (e.g. kindergartens, schools and universities), the healthcare and welfare sector (e.g. hospitals and care homes), the defence sector (e.g. army, navy and air force), the judicial sector (e.g. prisons and correctional services) and government office canteens. The study reports that the overall volume of meals served to public institutions is estimated to be 55% of the total number of meals provided by catering companies in Europe. The share distribution, in number of meals, among the distinct food service sectors is the following: 43% healthcare and welfare (e.g. hospitals and care homes), 31% education (e.g. schools and kindergartens), 18% business and industry (e.g. government building canteens), and 8% others (e.g. prisons or military services).

The study analysed the extent of the use of green criteria in the public purchase of food products and catering services in the European Union (EU) on a sample of 23 green public procurement (GPP) schemes (8 national schemes, 3 regional schemes and 10 local schemes) across 12 EU member states.

Some of the findings include:

The main food products covered by the criteria are fruits and vegetables, dairy products, fish and seafood, and meat.

The majority of the schemes reviewed focus simultaneously on both aspects (procurement of food products and catering services).

Criteria associated with kitchen equipment and vending machines are covered by some of the GPP schemes reviewed.

Cities, municipalities and counties are, within the schemes reviewed, the main public authorities reporting procurement for the education sector while national GPP guidelines have a broader scope and are applicable to multiple sectors carrying out public tendering.

Eight criteria are frequently used in the reviewed schemes: organic production (mentioned by 96% of the reviewed schemes); seasonal and fresh produce (83%); staff training (74%); transportation and packaging (both 65%); menu planning (61%); waste management (including food waste) (57%); marine and aquaculture products (52%); and animal welfare (48%).

For food procurement, most of the reviewed schemes set environmental criteria related to the production of food products and packaging, and less so related to the transport associated with the supply of the food products.

For the procurement of catering services, a large number of criteria is found to be related to the stage of the supply of the food service itself, followed by the life cycle stages of packaging and the production of food products.

Source: Eurostat (2023[27]), adapted from Neto and Gama Caldas (2017[25]).

3. Incentivising the development of the circular bioeconomy

Innovation and the adoption of circular business models play vital roles in facilitating the transition to a circular bioeconomy, as they enable companies to introduce or further develop bio-based products and services of a higher value, thereby enhancing their competitiveness in global value chains. Despite recent progress made in innovation policy implementation capacity in North Macedonia, overall investments in research and development remains low, at 0.4% of gross domestic product, and collaboration between businesses and academia as well the commercialisation of research needs to be further stimulated (OECD, 2022[28]). Macedonian SMEs, including in the biomass and food industry, continue to face challenges in significantly improving their innovation capacities, which could be mainly attributed to their engagement in low value-added activities, a lack of forward planning and a certain reluctance to innovate (BE-Rural, 2021[29]).

Funding and technical support for research and innovation projects are necessary to further incentivise the development of the circular bioeconomy in North Macedonia in the long term. Such projects would help process biomass, for example from the forestry industry, into higher value-added bio-based products and services. Technical and financial support for enterprises, as well as increased multi-stakeholder co-operation with the international research community (and across sectors), must be established to promote the development of biorefineries and biotechnology in North Macedonia. In particular, local SMEs face challenges to succeed in the circular bioeconomy market, as they typically face barriers to accessing finance and lack the skills to mobilise finance, have limited market access and knowledge as well as supply chain management issues (European Commission, 2019[30]). Numerous barriers hinder the advancement of the circular bioeconomy in North Macedonia, including: the absence of tangible measures integrated into existing strategic documents, inadequate infrastructure to support bioeconomy initiatives, insufficient dedicated funding, and the absence of robust financial models for both regional markets and broader financial support (BE-Rural, 2021[29]). To address these challenges, North Macedonia could establish a dedicated bioeconomy research and innovation programme with associated funding and technical support. Numerous regional and EU bioeconomy experts have also advocated for the establishment of bioeconomy research and innovation programmes across Central and Eastern Europe as a prerequisite for further development in this area (BIOEAST Consortium, 2021[31]). Several EU member states, including Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, have introduced bioeconomy strategies with dedicated research and innovation funding programmes for their domestic bio-based industries, such as the German SME Innovative: Bioeconomy funding scheme or the Dutch TKI Biobased Economy programme. Similar initiatives are being launched in many other European regions, such as Baden-Württemberg and North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany, Bio-based Delta in the Netherlands, Flanders in Belgium, and in some regions in Italy (Commission Expert Group for Bio-based Products, n.d.[32]).

The research and innovation support can also come through dedicated calls under some of the existing funding programmes, such as the National Programme for Financial Support of Rural Development,1 planned to be leveraged under the Smart Specialisation Strategy with the aim to develop new innovative products, processes and technologies in the agricultural and food sector. The development of the circular bioeconomy could also be supported with the implementation of the Agriculture and Rural Development Strategy, which has a specific focus on strengthening research, technology and digitalisation in the agriculture sector (in particular in the areas of smart agriculture and production methods).

4. Improving stakeholder engagement and collaboration, and awareness raising

To achieve a circular economy transition in the biomass and food sector and implement actions along the life cycle, North Macedonia will need to put in place a number of cross-cutting measures. These primarily include improving multi-stakeholder collaboration and stakeholder engagement, raising awareness on the circular bioeconomy among companies and households, and educating citizens and municipalities. It is also strongly recommended to co-ordinate these measures with similar ones proposed under the Smart Specialisation Strategy, as important synergies exist between the Smart Specialisation Strategy and the Circular Economy Roadmap in the biomass and food sector.

Collaboration across sectors, value chains and stakeholders is crucial for the success of a circular bioeconomy. This requires actors involved at various stages of the biomass and food value chains to collaborate towards shared objectives and goals. Evidence from some European countries suggests that a unified vision and collective efforts are necessary to build commitment for achieving overarching goals and targets (OECD, 2022[14]). In such an intricately interconnected value chain, every stakeholder has a vital role to play. However, they cannot operate effectively without partnering with other relevant actors.

The Law on Donating Surplus Food Waste, currently undergoing final consultations, foresees collaboration with the food industry and the non-governmental sector to promote food waste reduction strategies directed at consumers. The Smart Specialisation Strategy also includes actions that promote collaboration and partnerships towards smart agriculture and higher value-added food and the establishment of a number of working groups for this purpose. The inter-ministerial collaboration between the Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management will also need to be reinforced, as such collaboration is crucial for implementing the proposed recommendations in this sector.

In addition, a knowledgeable, well-informed and skilled population can stimulate action towards a circular bioeconomy and help provide solutions to the complex and interconnected challenges posed by the circular economy. Except for awareness-raising campaigns on food waste conducted by the association “Let’s do it Macedonia”, other awareness activities on the circular bioeconomy’s potential remain scarce. The Faculty of Technology and Metallurgy of Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje has introduced some courses on topics related to the bioeconomy, such as the development of valorisation processes for biomass and natural waste materials. Nevertheless, an overarching curriculum on this topic is lacking. Recognition of these barriers is in alignment with the objective of cultivating a professionally led and knowledge-based agri-food sector, as outlined in the Smart Specialisation Strategy.2

In the short term, North Macedonia will need to strengthen multi-stakeholder collaboration across the entire biomass and food sector, including with relevant experts, knowledge institutes and ministerial departments. This can be achieved by establishing a dedicated working group on the circular bioeconomy, which could be formed and operate as a sub-group within the wider circular economy stakeholder group set up for the preparation and implementation of this roadmap. The biomass and food sub-group could further discuss the implementation of existing and planned measures, whose implementation would benefit from improved collaboration on issues of communication, financing and legislation in line with relevant legislation and objectives. It could also develop strategic guidance on additional measures that need to be implemented to achieve a circular bioeconomy in the country. The sub-group should co-ordinate with the working groups that are planned to be formed under the Smart Specialisation Strategy to prevent duplication of efforts.

Establishing a circular economy platform (see Chapter 4) or voluntary agreements could also enhance collaboration between various stakeholders and the sharing of best practices. As outlined in the Smart Specialisation Strategy, the creation of a platform for integrated information on policy instruments and measures related to the agri-food domain presents a valuable opportunity for advancing the bioeconomy. This initiative has the potential to serve as an outlet for fostering a thriving circular bioeconomy. By leveraging this platform, North Macedonia can enhance transparency and accessibility for potential beneficiaries, offering detailed insights into available options and calls specifically tailored to the circular bioeconomy sector. This aligns with the broader objective of promoting smart agriculture and enhancing the value of food production in North Macedonia, positioning the circular bioeconomy as a key sector in this strategic initiative. North Macedonia could also draw upon the guidance provided by the EU REFRESH project (Burgos et al., 2019[33]) to establish voluntary agreements and partnerships that prompt transformation in the food sector, if possible with the support of (international) experts with experience in building voluntary agreements. In the featured five-step model, stakeholders can work together to achieve real change more rapidly and more cost-effectively (Box 6.4).

Box 6.4. Establishing voluntary agreements to strengthen multi-stakeholder collaboration on reducing food waste

Voluntary agreements (VAs) are bilateral agreements between a private party and the public administration, usually involving a subsidy for the private party to implement certain measures (e.g. changes in product design or technology through research, development and innovation), contingent upon improving environmental performance beyond regulatory obligations.

Voluntary agreements as a key policy area for reducing food waste

The objectives of a VA are collectively designed in consultation with all supply chain actors to ensure that each actor’s needs and specificities are represented, which facilitates the development of relevant and attainable targets.

The voluntary and non-legal characteristics of a VA make its structure flexible, which is advantageous, as its targets and objectives can be quickly and easily adjusted in response to changing policy contexts.

The potential for large savings and/or enhanced brand image creates a strong business case for participating members to join a VA, especially if key organisations and businesses are involved.

Creating a favourable context for a voluntary agreement

Agree on a target (link to a pre-existing target or establish a new one) – in the absence of a legislative target, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 12.3, which aims to halve per capita food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses by 2030, could act as a guiding principle.

Ensure long-term financing and governance (a donation/grant ideally from a mix of public and private funding operated by, for example, a steering committee with focused working groups).

Establish an independent third party unrelated to other public or private entities (e.g. a company, university or research institution) to lead the VA (the main pillar of a VA’s success).

Consider wider supply chain issues in VA discussions.

Define a short-list of the key actors across the value chain committed to the VA.

Establish a measurement methodology to define progress and track results.

Sources: OECD (2023[27]) adapted from Burgos et al. (2019[33]); EEA (n.d.[34]).

To implement measures that promote a circular bioeconomy more effectively, North Macedonia should build upon or collaborate on the measures proposed in the Smart Specialisation Strategy and focus on awareness raising, education and skills on preventing food waste; separating bio-waste at the source; and composting in the short term. Citizens, public entities and companies in the circular bioeconomy area should all be targeted. Raising awareness and promoting education can be achieved by showcasing successful pilot projects, initiatives and campaigns; creating a dedicated platform; and implementing targeted consumer campaigns and interactive events. Such efforts can encourage positive changes in behaviour, attitudes and practices.

International good practices offer many tools to prevent food waste by companies and consumers, managing bio-waste, improving the sorting of such waste by households at its source, and utilising date marking or marketing practices to reduce food waste. Effective tools utilise behavioural science insights and engage retail and food industries as well as social media influencers, to incentivise positive behaviour (such as offering rewards) rather than imposing penalties (OECD, 2022[14]). For instance, sharing best practices via an online platform (e.g. a circular economy platform; see Chapter 4) can promote a standardised approach to bio-waste separation at the source across municipalities. EU countries have also been adopting national EU food waste and food losses platforms, in line with the EU Platform on Food Losses and Food Waste (European Commission, 2023[35]). The platform must have a precise and defined scope, drawing on existing inventories and information channels. The resources should be easily searchable while enabling the sharing of best practices and guidance materials (OECD, 2022[14]).

References

[29] BE-Rural (2021), Bioeconomy Development Roadmap for Strumica Region, BE-Rural, https://be-rural.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/BE-Rural_D5.3_SDEWES-Skopje_EN.pdf.

[31] BIOEAST Consortium (2021), BIOEAST Foresight Exercise: Sustainable Bioeconomies Towards 2050, BIOEAST Consortium, https://bioeast.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/BIOeast-Report-2021_FINAL_compressed-1.pdf.

[33] Burgos, S. et al. (2019), Voluntary Agreements as a Collaborative Solution for Food Waste Reduction, EU Horizon 2020 REFRESH, https://eu-refresh.org/voluntary-agreements-food-waste.html.

[32] Commission Expert Group for Bio-based Products (n.d.), Working Group on Evaluation of the Implementation of the Lead Market Initiative for Bio-based Products’ Priority Recommendations, Commission Expert Group for Bio-based Products, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/13269/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

[21] Delegation of the European Union to North Macedonia (2022), “EU supports food banking: Reducing food waste – reducing hunger”, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/north-macedonia/eu-supports-food-banking-reducing-food-waste-%E2%80%93-reducing-hunger_en?s=229 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

[18] Dollhofer, M. and E. Zettl (2018), Quality Assurance of Compost and Digestate, Federal Environment Agency, Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/quality-assurance-of-compost-digestate.

[20] ECN (2022), Guidance on Separate Collection, European Compost Network, Bochum, Germany, https://www.compostnetwork.info/download/ecn-guidance-on-separate-collection.

[19] EEA (2020), Bio-waste in Europe: Turning Challenges into Opportunities, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen, https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/bio-waste-in-europe.

[34] EEA (n.d.), “Voluntary agreement”, EEA Glossary, https://www.eea.europa.eu/help/glossary/eea-glossary/voluntary-agreement.

[24] EU Platform on Food Losses and Food Waste (2019), Redistribution of Surplus Food: Examples of Practices in the Member States, https://ec.europa.eu/food/system/files/2019-06/fw_eu-actions_food-donation_ms-practices-food-redis.pdf.

[35] European Commission (2023), EU Platform on Food Losses and Food Waste, https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste/eu-platform-food-losses-and-food-waste_en (accessed on 12 December 2023).

[15] European Commission (2021), Carbon Economy: Studies on Support to Research and Innovation Policy in the Area of Bio-based Products and Services, Publications Office of the European Union.

[30] European Commission (2019), Bio-based Products: From Idea to Market “15 EU Success Stories”, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/23ab58e0-3011-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1.

[26] European Commission (2019), EU Green Public Procurement Criteria for Food, Catering Services and Vending Machines, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/pdf/190927_EU_GPP_criteria_for_food_and_catering_services_SWD_(2019)_366_final.pdf.

[1] European Commission (2018), Updated Bioeconomy Strategy 2018, European Commission, Brussels, https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/publication/updated-bioeconomy-strategy-2018_en#:~:text=The%202018%20update%20of%20the,well%20as%20the%20Paris%20Agreement.

[22] European Commission (2017), Commission Notice: EU Guidelines on Food Donation, 2017/C 361/01, European Commission, Brussels, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52017XC1025(01).

[17] European Commission (n.d.), Factsheet: Slovenia, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/waste/framework/facsheets%20and%20roadmaps/Factsheet_Slovenia.pdf.

[23] European Commssion (2020), Food Redistribution in the EU: Mapping and Analysis of Existing Regulatory and Policy Measures Impacting Food Redistribution from EU Member States, European Commssion, Brussels, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2875/406299.

[27] Eurostat (2023), “Gross value added and income by A*10 industry breakdowns [nama_10_a10__custom_8247007]”, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10_a10__custom_8247007/default/table.

[6] Eurostat (2023), “Organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops”, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/org_cropar/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 16 November 2023).

[13] Gilbert, J., M. Ricci-Jürgensen and A. Ramola (2020), Benefits of Compost and Anaerobic Digestate When Applied to Soil, International Solid Waste Association, https://www.altereko.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Report-2-Benefits-of-Compost-and-Anaerobic-Digestate.pdf.

[5] Invest North Macedonia (2022), “Introduction to key industries”, https://investnorthmacedonia.gov.mk/export-key-industries/#:~:text=Textile%20and%20clothing,of%20the%20country%20after%20metallurgy.

[2] Kardung, M. et al. (2021), “Development of the circular bioeconomy: Drivers and indicators”, Sustainability, Vol. 13/1, p. 413, https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010413.

[7] MAKSTAT (2023), “Agricultural areas and crop production, 2022”, https://www.stat.gov.mk/PrikaziSoopstenie_en.aspx?rbrtxt=127.

[16] Ministry for Agriculture and Forestry, Environment and Water Management of Austria (2009), The State of the Art of Composting, Austrian Government, https://www.bmk.gv.at/dam/jcr:69c43c71-1844-4c52-8d0c-20e0d9ced59f/Richtlinie_Kompost_en.pdf.

[4] Ministry of Education and Science (2023), Draft Smart Specialisation Strategy of the Republic of North Macedonia, https://mon.gov.mk/download/?f=EN-%20S3-MK%2020.12.2023.docx#:~:text=The%20%E2%80%9CSmart%20Specialisation%20Strategy%20of,a%20strategic%20vision%2C%20priorities%20and.

[10] Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning (2023), Fourth National Climate Change Communication, Government of the Republic of North Macedonia, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/EN%2C%20IV%20NCCC.pdf.

[9] Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning (2021), North Macedonia Waste Management Plan 2021-2031, Republic of North Macedonia, https://www.moepp.gov.mk/%d0%b4%d0%be%d0%ba%d1%83%d0%bc%d0%b5%d0%bd%d1%82%d0%b8/%d0%bf%d0%bb%d0%b0%d0%bd%d0%be%d0%b2%d0%b8/.

[8] Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning (2021), Waste Management Plan of the Republic of North Macedonia, 2021-2031, Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning.

[25] Neto, B. and M. Gama Caldas (2017), “The use of green criteria in the public procurement of food products and catering services: A review of EU schemes”, Environment, Development and Sustainability, Vol. 20/5, pp. 1905-1933, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9992-y.

[36] OECD (2023), Towards a National Circular Economy Strategy for Hungary, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1178c379-en.

[14] OECD (2022), “Closing the loop in the Slovak Republic: A roadmap towards circularity for competitiveness, eco-innovation and sustainability”, OECD Environment Policy Papers, No. 30, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/acadd43a-en.

[28] OECD (2022), SME Policy Index: Western Balkans and Turkey 2022: Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b47d15f0-en.

[11] Salvatori, G., F. Holstein and K. Böhme (2019), Circular Economy Strategies and Roadmaps in Europe: Identifying Synergies and the Potential for Cooperation and Alliance Building, European Economic and Social Committee, Brussels, https://doi.org/10.2864/554946.

[3] Stegmann, P., M. Londo and M. Junginger (2020), “The circular bioeconomy: Its elements and role in European bioeconomy clusters”, Resources, Conservation & Recycling: X, Vol. 6, p. 100029, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcrx.2019.100029.

[12] World Bank (2022), Western Balkans Regular Economic Report No.21: Steering Through Crises, World Bank Group, Washington, DC.

Notes

← 1. The Agency for Financial Support in Agriculture and Rural Development administers the National Programme for Financial Support of Rural Development, which aims to enhance the effective implementation of agricultural and rural development policies in North Macedonia. With a budget of MKD 1 346 366 000 (approximately EUR 21 852 400), the programme includes measures to support agricultural producers through training and information, promote the involvement of young people and women in the sector, invest in modern technologies and infrastructure for the processing of agricultural products, and address environmental protection concerns (particularly water use and biodiversity).

← 2. Several measures are proposed to enhance human resources through quality education and training (e.g. offering master, doctoral and post-doctoral grants to support research related to the agri-food domain or supporting twinning opportunities for knowledge transfer). This strategic approach also aims to create conditions conducive to retaining young professionals in rural areas engaged in agriculture, food processing and marketing (e.g. prioritise the sector in scholarship schemes or conducting student contests).