Structural duality is an important characteristic of Argentina’s agriculture and is reflected in the differences between the Pampas region and those that surround it. In the Pampas region, most of the grains, oilseeds and beef is produced by large-scale, export-oriented producers. This agriculture is highly productive, with well-developed value chains linked to international markets. Oher regions (“the regional economies”) produce fruits and vegetables and agro-industrial products like wine, tobacco, cotton or sugar. Some of these products, like apples, pears and wine, are exported in competitive world markets but have an internal duality. In the apple-and-pear value chain farms which are fully integrated into global markets (usually large and medium size) coexist with less integrated farms (mostly small-scale). These small-scale farms have several difficulties, particular the low use of technology, deficient pest control, old orchards, and in general, very limited investments at farm level. Meanwhile, the viticulture value chain has had significant investments since 1990s by both foreign and local investors attracted by deregulation and relatively low‑price, good-quality land. Nonetheless, it still faces several constraints, particularly related to limited research and development, training and extension services.

Agricultural Policies in Argentina

Chapter 9. Value chains in Argentina: Apples and pears, and viticulture

Abstract

9.1. Introduction

Argentine agriculture has experienced substantial changes over the last five decades1. These include significant increases in output as well as in the Total Factor Productivity (TFP) of most commodities. Shifts in resource use include the dramatic rise in soybean production, increased use of fertilisers and other modern inputs, and increased use of farm machinery, with corresponding decreases in the amount of labour employed in the sector. This led to a structural adjustment, with a fall in the number of small-scale farms and an increase in average farm size in most regions. However, this success story has not taken place with equal intensity in all regions and all production activities (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

A characteristic of Argentina’s agriculture it is the duality of its structure, reflected in the differences between the Pampas region and those surrounding it. The Pampas region accounts for the production of most of the country’s grains, oilseeds and beef. It is characterised by large-scale, highly productive, export-oriented agriculture with well‑developed value chains linked to international markets. As discussed in chapter 2, it has important forward linkage to domestic and global value chains (GVCs). The remaining regions in the country – those surrounding the Pampas and called “the regional economies” – produce fruits and vegetables and other agro-industrial products like wine, tobacco, cotton or sugar. These regional economies have relatively low levels of productivity and less dynamic value chains.

In terms of agricultural policy, there has been a distinction between the Pampas region and the regional economies. For the Pampas, in general, a policy of negative support has been a common denominator over the years. The regional economies have not been similarly burdened. On the contrary, some support has been given to farmers producing specific like tobacco; however, key problems in these regions have not been widely addressed by public policy, and public investment on agricultural infrastructure, R&D, extension services, and technical assistance has been limited. This chapter explores two value chains situated in the regional economies: apples and pears, and wine.

The principal apple and pear producing region of the country comprises the provinces of Rio Negro and Neuquén. Total area of fruit production in this region is 56 000 irrigated hectares, of which more than 80% is planted with apples and pears. The apple-and-pear value chain in Argentina has a duality within its structure, whereby farms fully integrated into it (usually large and medium size ones) coexist with less integrated farms (mostly small-scale ones).

The viticulture value chain includes a set of productive linkages oriented to the production of wine and must. The total area of grapevine production is 224 706 hectares, distributed in more than 25 000 vineyards with an average area per vineyard of 9 hectares. Around 92% of vineyards are for wine production, the rest is consumed as table grapes. During the 1990s, along with the deregulation of the industry, significant investments in the viticulture sector took place, and Argentina’s exports grew alongside an improvement in quality and of average export prices.

9.2. The apple-and-pear value chain

Description of the value chain

Production

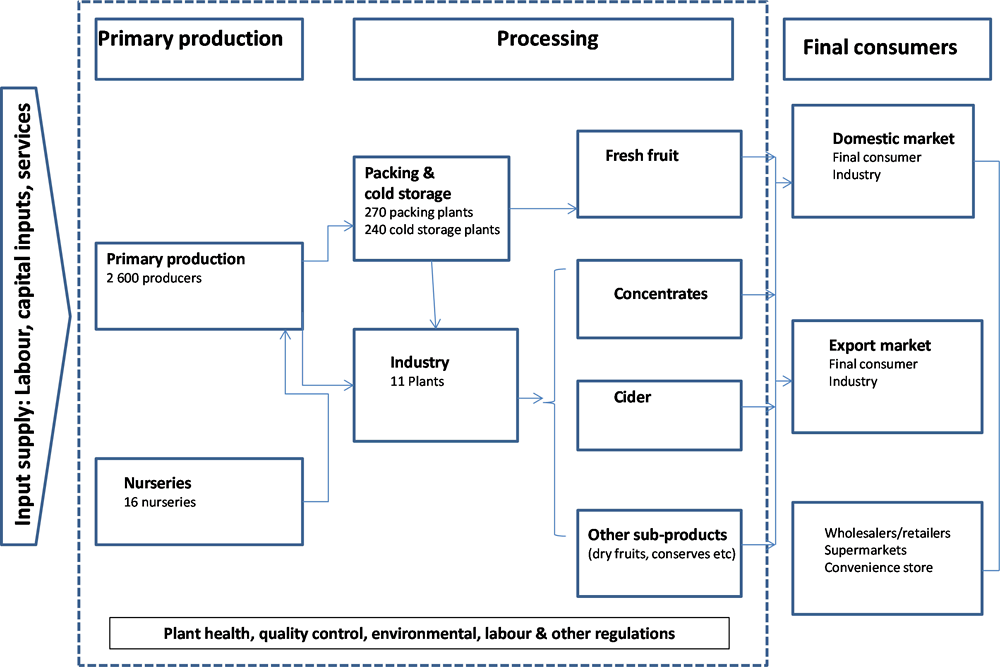

A standardised agricultural value chain connects farmers with the commercialisation of their products. The main stages include inputs provision, producers, middlemen/wholesalers, distributors and retailers. Depending on the commodity, additional stages can include industrial processors, and exporters. Figure 9.1. shows the value chain of apples and pears in Argentina.

The apple-and-pear value chain is organised around a significant infrastructure of orchards, irrigation facilities, packing and cold-storage plants, logistic and transport services, and a modern export port facility. The industry also has access to significant R&D expertise from INTA and local university resources. Heterogeneity of firm size exists, ranging from large, vertically integrated export-oriented multinational firms, medium-sized firms specialising in production linked via contracts to marketing channels, and small‑medium independent farms (Leskovar, 2016[2]).

Argentine apples and pears are produced in several areas of the country; however, Rio Negro and Neuquén provinces account for most of the country’s production, with 70% of the total planted area of the country. The rest is mostly in the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan. For this assessment, only Rio Negro and Neuquén provinces are considered. Apple and pear production is irrigated, with 24 179 hectares to apples and 22 585 to pears. The total number of apple and pear farmers in the region is 2 266, making an average size of 18.7 hectares (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016[3]).

In terms of land structure for apple- and pear-producing farms, Table 9.1. suggests that nearly 80% of farms are less than 20 hectares. Some structural change can be observed in this subsector from 2007 to 2016, where small-scale farms (less than 10 hectares) lost an important number of operations. Possible variables explaining this adjustment are labour costs, mechanisation, difficulty to access international markets, as well as relatively higher regulatory costs (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016[3]).

Technology used by apple and pear farmers range from very low to medium. Nearly half of producers in the Rio Negro and Neuquén provinces are characterised by low or very low technology, with orchards older than 26 years, and relatively small production units of less than 10 hectares. This type of farmer accounts for nearly 30% of area planted with apples and pears in the Río Negro valley. High technology farms are those with more than 30 hectares and with orchards between 14 and 20 years old. These large farms also tend to use other technologies; for example, 70% use sprinkler irrigation for frost protection versus only 15% of small-scale farms (those with less than 10 hectares).

Yields in Argentina are relatively far below the yields of the main producing countries (Table 9.2). Argentina has a better relative positioning of average yield per hectare in pear production than in apple production (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016[3]).

Figure 9.1. Argentina’s apple-and-pear value chain

Source: Ministerio de Hacienda, 2017.

Table 9.1. Size distribution of producers and number of apple and pear producers

|

Size range (ha) |

2007 |

2016 |

2016/07 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

0 - 10 |

1 380 |

1 201 |

0.87 |

|

10 - 20 |

606 |

568 |

0.94 |

|

20 - 30 |

213 |

219 |

1.03 |

|

30 - 40 |

113 |

115 |

1.02 |

|

40 - 50 |

47 |

43 |

0.91 |

|

50 - 100 |

89 |

73 |

0.82 |

|

> 100 |

48 |

47 |

0.98 |

|

Total |

2 496 |

2 266 |

0.91 |

Table 9.2. Average yields 2002-12, selected countries

|

Apples |

Pears |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Country |

Yield (tonnes/ha) |

Country |

Yield (tonnes/ha) |

|

New Zealand |

49.5 |

New Zealand |

43.4 |

|

Chile |

43.3 |

Chile |

28.9 |

|

South Africa |

35.2 |

South Africa |

28.7 |

|

Average |

33.1 |

Argentina |

27.1 |

|

Brazil |

32.9 |

Average |

26.1 |

|

Argentina |

24.6 |

Australia |

17.3 |

|

Australia |

13.2 |

Brazil |

11.4 |

Source: Ministerio de Hacienda, 2017.

In apple and pear production, labour is a significant input, representing between 45% and 50% of total costs. Output per unit of land is not necessarily the crucial metric for profitability, and output per labour-hour is more correlated with profitability.

In 2016, the total production was 594 000 tonnes of pears and 550 000 of apples (Leskovar, 2016[2]). Around 56% of these fruits are sold in the domestic market; the remainder is for export. Approximately 72% of aggregate output of both apples and pears is consumed fresh, with the remaining 28% sent to agroindustry. Around 60% of production for fresh consumption is exported, and 35% is consumed domestically. Pear exports represent 80% of fresh output and apples only 35%. The variety of apples most consumed in Argentina is Red Delicious (80%), and those of pears are Williams (61%) and Packham's (35%). The national per-capita consumption of apples is around 7 kg and only 2.2 kg for pears (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2017).

As a system, the apple-and-pear value chain is governed by both formal and informal organisations, and numerous linkages among them. Formal organisations can be public, private or of a non-governmental, non-profit type. Public institutions include INTA, SENASA, the Secretariat of Agroindustry, public banks and universities. Private organisations are formed by fruit producers, packers and storage plants, transport and general logistics firms, input suppliers including agricultural professional services, and private audit/certification services. Non-profit organisations and NGOs also play a role at the producer, packer and transport stages. Such organisations include producer associations, producer and processing co-operatives, chamber of commerce, committees of plant health, and trade unions. Informal organisations include input and output markets at all levels of the value chain, informal information exchange networks, and lobbying efforts by private agents.

At the primary level, co-ordination along the value chain involves interaction of some 2 400 producers, with more than 300 packers, industrial processing plants, transport networks, wholesalers, and exporters, input suppliers, workers and financial institutions. The organisational problem faced by this value chain is not different from other contexts: potential conflict has to be converted into co-operation, resources have to be mobilised and effort has to be co-ordinated. These activities take place among individuals whose preferences, information, knowledge and interests differ (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Conventional producer co-operatives have made modest inroads in the apple‑and‑pear value chain of Argentina’s main producing area (Río Negro province). The first fruit co‑operative was created in the late 1930s, and it currently has only 50 members. The interest in co-operatives has not translated into new effective start-ups or growth of existing co-operatives (Hak, 2009[4]). This situation of low horizontal integration contrasts with other countries, where agricultural co-operatives play a significant role. In the United States, for example, there are 167 fruit and vegetable co‑operatives, with 32 200 members and a volume of sales of USD 7.6 billion per year (USDA, 2011[5]).

Although the potential exists for improving producer profitability through co‑operative marketing arrangements, significant well-known co-operative challenges remain: the dispersion of authority, partial non‑alienability of individual property rights over resources, absence of the profit motivation, and free rider problems all conspire against co-operative survival in a competitive marketplace.

Packing/processing and retailing

Leskovar et al. (2016[2]) describe marketing channels for domestic consumption of pears and apples in Argentina:

Integrated producer (orchard + packing) with the following variants:

selling directly in the central market

from central market to self-service retailers

from central market to hyper-supermarkets

selling directly to purchasing unit of hyper-super markets

selling to wholesaler operating in central market

from large wholesaler to smaller wholesaler and then to groceries

from wholesaler to fresh produce groceries.

Non-integrated producer contracts out classification, packing and cold storage.

Non-integrated producer sells output to packing plant.

In general terms, small-scale producers (those with less than 15 hectares), tend to be non‑integrated and thus contract out the marketing work or sell their output to the packing plant, while large-scale farms use the first integrated channel Although a large number of producers are organised around channels 2 and 3, a substantial portion of output uses channels where some degree of integration exists. In the Rio Negro region, there are around 300 packing/processing plants of different sizes, suggesting a relatively high degree of competition in this link of the chain.

For producers of apples and grapes, two marketing channels can be distinguished: the city of Buenos Aires and the rest of the country. The Buenos Aires market is the largest channel where vertically integrated producers sell to the main wholesale market of the country (the Mercado Central de Buenos Aires) and from this wholesale market to retailers. This channel is followed in importance by supermarket chains purchasing directly from integrated producers, and in third place by integrated producers selling directly to retailers. For the rest of the country, supermarkets are less significant than small and medium traditional retailers, who tend to buy from non-integrated farmers (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

As in many other countries, important changes have taken place in the retail process in Argentina during the last half-century. The shift from small specialised stores (e.g. butchers, fruit stalls, dry goods stores) to large, diversified and self-service retailers (supermarkets) started in the early 1960s and has grown steadily since then. Carrefour (France), Walmart (US), CENCOSUD (Chile), and Groupe Casino (France) are some of the main companies in the country. By 2012, around 10 large supermarket chains (foreign and local) were operating in the country (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Ablin (2012[6]) provides information on the degree of market power of the retailer sector in Argentina. According to the author, the eight largest supermarket chains account for 15% of supermarket points-of-sale (POS) (1 300 of a total of 8 700). Around 32% of POS belong to firms with two or more POS, and the remaining 68% belong to firms with only one POS. About 80% of firms with only one POS are owned by individuals of Asian origin, mostly Korean or Chinese. The market shares of the principal supermarket and self‑service retail channels break down as follows: hypermarkets 34%; supermarkets 29%; self‑service stores of Asian origin 25%; other self-service stores 8%; and discount stores 3% (Ablin, 2012[6]).

Price differentials between various stages of the value chain result from associated cost differentials in transforming/transporting/selling products along successive stages. Table 9.3 shows prices along the value chain. The last two columns show price differentials between value chain stages: i.e. between the producer and packer, and between wholesaler and retailer. Under competitive conditions, these price differentials approximate the cost involved in each value chain stage. The wholesale-retail process involves considerably higher costs than the producer-packer stage. This situation reveals the importance of efficiency in the transformation process from the orchard to packing warehouse, and eventually the wholesale to retail sale. As can be calculated from the table, these strictly agribusiness costs (farm-warehouse plus warehouse‑wholesale stages) represent between 40% and 45% of the total cost of transferring products from farm to consumer (Leskovar, 2015[7]).

Table 9.3. Apple and pear prices along the value chain (USD/kg), 2015

|

Fruit |

Producer FOB packing plant |

Exit packing plant |

Wholesaler exit central market |

Retailer |

Producer-packer difference |

Wholesaler-retailer difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Williams pear Buenos Aires market |

0.26 |

0.64 |

0.80 |

1.61 |

0.38 |

0.81 |

|

Red Delicious apple Buenos Aires market |

0.31 |

0.94 |

1.25 |

2.39 |

0.63 |

1.14 |

Source: Leskovar et al. (2015[7]).

Exports and competitiveness

Future expansion of the Argentine apple and pear sector depends on access to international markets. The reason is that domestic markets are not expected to absorb large increases in production without a significant drop in prices (i.e. demand for most foods, including fruits, is generally price-inelastic). Access to international markets depends on the structure and nature of tariff and non-tariff barriers, as well as on the functioning of the value chain from the farm gate, through export ports and subsequent linkages up to the final consumer in the importing country (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Table 9.4 shows the structure of the apple-and-pear export subsector. Four firms account for 40.4% of exports. The next four account for another 17.6%, and the rest of the exporters account for 42%. There is a reasonable degree of competition as the Herfindhal‑Hirshman index2 suggests a number of 600, corresponding to an un‑concentrated industry. Notwithstanding, attention is warranted on the characteristics of price transmission in the value chain due to the heterogeneous and perishable characteristic of the product, and the possibility that significant information asymmetries exist among market participants (Leskovar, 2015[7]).

Table 9.4. Apple and pear export firms in Argentina, 2015

|

Order |

Firm |

Pear (%) |

Apple (%) |

Total (%) apple and pear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Patagonian Fruit Trade SA |

11.2 |

13.4 |

11.8 |

|

2 |

Univeg Expofrut |

9.9 |

17.2 |

11.7 |

|

3 |

Moño Azul SA |

9.6 |

8.6 |

9.4 |

|

4 |

PAI SA |

7.5 |

7.6 |

7.5 |

|

5 |

Ecofrut SA |

6.3 |

3.8 |

5.7 |

|

6 |

Kleppe SA |

4.2 |

5.9 |

4.6 |

|

7 |

Montever SA |

3.8 |

4.3 |

3.9 |

|

8 |

Tres Ases SA |

3.5 |

2.9 |

3.4 |

|

9 |

Estándar Fruit Arg. SA |

3.6 |

0.0 |

2.7 |

|

10 |

Salentein Fruit SA |

2.3 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

|

11 |

Mario Cervi e Hijos SA |

2.2 |

5.4 |

3.0 |

|

12 |

Carbajo V |

1.9 |

0.6 |

1.6 |

|

13 |

Via Frutta SA |

1.8 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

|

14 |

Martínez R. |

1.2 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

|

15 |

Others (pears 116, apples 91) |

30.8 |

25.6 |

29.5 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: Leskovar et al., (2015[7]).

Leskovar et al., (2015[7]) present a detailed analysis of marketing channels in the export markets for apples and pears, as well as of prices in different stages of the value chain. The authors identify different organisational forms in the apple-and-pear export value chain: large and medium-scale integrated producer‑exporters; and small and medium‑scale non‑integrated producers. In the case of overseas shipments (mostly to Europe) the chain includes exporter, importer, distributor, supermarkets and consumers. Importers can also link directly to wholesalers, then to medium retailers and finally to consumers. Significant economies in the cost of information transfer (including quality control) are achieved by large-volume players, and frequency on transactions is crucial in facilitating exchanges (Leskovar, 2015[7]).

The Argentine agricultural sector is characterised by a strong competitive export position in oilseeds, cereals, beef, poultry and dairy products, despite export taxes. This success story contrasts with performance of the apple-and-pear value chain, where Argentina appears to have lagged behind (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Under the standard assumption of reasonably competitive conditions, cost minimisation and resulting efficiency should prevail. However, these conditions may apply only partially due to low levels of farmer education, risk aversion, severe financial constraints, information asymmetry, government regulations, positive or negative externalities, or below-optimum provision of public goods. For example, inadequate monitoring of pesticide applications by producers selling in the domestic market may reduce the prospects of pear and apple producers aiming at the international markets: pesticide residues in irrigation water, or the presence of plant diseases require not only orchard-specific but area‑wide compliance of production practices (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Comparing competitiveness of participants in apple and pear international markets show interesting results for Argentina. In the World Apple and World Pear reviews produced by Belrose,3 factors of competitiveness are classified as: (a) orchard‑level production efficiency, (b) industrial infrastructure and inputs and (c) financing and markets4 (Villareal, 2011[8]). Table 9.5 summarises results for four Southern Hemisphere countries that compete for the same market niche: the off-season in the Northern Hemisphere: Chile, New Zealand, South Africa and Argentina. Some of these countries are middle-income economies that may face similar overall constraints for the development of an export‑based industry.

In terms of overall competitiveness, Chile is ranked first out of a sample of twenty‑nine countries, both for apples and pears. New Zealand ranks high for apples, and somewhat lower for pears. Argentina shows a poor overall ranking for apples, below South Africa and New Zealand, but a better one for pears, for which it is above both countries. Why is Argentina more competitive in pears than in apples?

Further insights are provided by rankings in the three competitiveness factors considered in Table 9.5. Infrastructure and input provision does not seem to be the most severe constraint in Argentina: it is ranked fifth for both apples and pears, slightly below New Zealand, which ranks third. Again, Chile leads the ranking for this dimension. Infrastructure and inputs include irrigation facilities, access to inputs (fertiliser, pesticides, and machinery services) as well as access to packing, logistics, marketing and export services. The medium to high ranking for Argentina in this dimension suggests that port‑facilities are efficient and reasonably priced, roads are operable year-round, and packing and classification plants are numerous and competitive (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Table 9.5. Competitiveness in apple and pear production, ranking, 2010

|

Apples |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Country |

Competitiveness dimension |

|||

|

Overall |

Production |

Infrastructure and inputs |

Financing and markets |

|

|

Chile |

1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

|

New Zealand |

5 |

5 |

3 |

8 |

|

South Africa |

13 |

6 |

9 |

21 |

|

Argentina |

16 |

14 |

5 |

24 |

|

Pears |

||||

|

Country |

Competitiveness dimension |

|||

|

Overall |

Production |

Infrastructure and inputs |

Financing and markets |

|

|

Chile |

1 |

11 |

1 |

13 |

|

New Zealand |

9 |

14 |

3 |

6 |

|

South Africa |

11 |

2 |

8 |

17 |

|

Argentina |

8 |

1 |

5 |

16 |

Source: Villareal, (2011[8]) based on Belrose, World Apple Review, World Pear Review.

However, Argentina performs poorly for both apples and pears in the financing and markets dimension. Argentina’s high interest rates and high and variable inflation has led to financial constraints and difficulties in business planning beyond the fruits subsector, or indeed the whole agricultural sector (Chapter 7). Additionally, the property rights variable is also included in the financing and markets dimension, and Argentina’s litigation system involves significant levels of red tape. Inflation, coupled with weak property rights, possibly explains the reluctance of banks to extend mortgage-backed credit to producers (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

The main factor explaining the different competitiveness ranking of pears and apples in Argentina is production efficiency at the orchard level, where significant differences are observed between the two fruits. For pears, the country produces high quality high demand varieties and ranks first, while Chile, an otherwise strong competitor, is in 11th place; for apples, Argentina occupies 14th place, far below the other countries (Table 9.5).

To recap, two points emerge from an analysis of Argentina’s apple and pear subsector. First, Argentina is characterised by significant lags in the financing/markets dimension, which in relative terms is more significant than infrastructure and input deficiencies. Secondly, as compared to other countries such as Chile, Argentina shows a significantly higher orchard-level production efficiency in pears, but not in apples, where it ranks poorly; this advantage in the primary production of pears partially compensates for other weaknesses that affect both pears and apples, positioning Argentina in the top ten competitive pear exporters.

SWOT analysis and challenges of the value chain

Several problems are faced by the Argentine apple-and-pear value chain, suggesting that the subsector has performed below its full potential. At the production stage and despite the better performance of pears, a significant portion of production units in both value chains are characterised by small-scale size and low capitalisation. There are partially abandoned or sub-managed orchards, which constitute breeding grounds for pests (in particular the codling moth). These orchards generate a negative plant health risk for modern, export-oriented production units. There are deficiencies at orchard-level management and agronomic practices such as non-adoption of risk-mitigation alternatives, low level of R&D and technology transfer, particularly for small-scale farms. High volatility of net incomes results in financial constraints and reduced incentives along the value chain (Sturzenegger, 2017[9]).

The strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) of the apple‑and‑pear value chain in Argentina are summarised in Table 9.6. The principle strengths are public institutions such as INTA and SENASA, and the long history of production and comparative advantage. The principle weaknesses relate to Argentinian macroeconomic conditions and markets, in particular financial and labour markets. Labour input costs are most significant, adding up to 50% of total costs. An important threat is the variability of the real exchange rate (RER) that has the determinant role of income volatility throughout the value chain (Sturzenegger, 2017[9]). Fluctuations in the RER (a product of macroeconomic instability) pose a threat to exporters, particularly those operating in a sector where non-tradeable inputs comprise a substantial portion of total costs. Moreover, labour markets in Argentina are highly regulated and pose risks for entrepreneurs, in particularly small and medium SMEs. For example, there is heavy red tape in the litigation processes.

In contrast with extensive grain production, fruit output can be of widely varying quality, and productivity measures should take into account the ratio of quality-adjusted output to input. The fact that fruit is exported puts a premium on environmental practices and food safety and quality attributes. The fresh fruit value chain is highly complex, and both entry into it and success are difficult for firms lacking experience, technology and scale. Furthermore, food safety, environmental, labour and other standards are a critical aspect in international trade of agricultural products. These standards are of particular importance for fresh produce, whose perishable and physical characteristics require specialised transport, storage and handling procedures. Sanitary conditions for fruit are also critical to access export markets. The increased importance of private standards in international trade is an important aspect to consider within public policy, and in particular how such standards benefit larger and more integrated producers to a greater extent than small-scale producers, who may need technical assistance to adapt.

Perspectives for further insertion of Argentine fresh fruits in the international markets will be closely linked to macro developments, political stability and the rule of law, the stability and development of domestic financial services, and labour legislation which reduces litigation and non-salary labour costs. Further insertion will also be linked to infrastructure developments (roads, ports, and communications). Improvements in these dimensions increase the rate of return to foreign direct investment and facilitate the transition of firms to world-wide player status, a necessary condition for competing in the highly complex environment of the fresh fruit markets (Table 9.6 and Lema and Gallacher (2018[1])).

Table 9.6. SWOT analysis of the apples and pears value chain, 2018

|

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

Opportunities |

Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Availability of land. |

Macroeconomic fluctuations (exchange rate). |

Export markets seem to be growing. |

Increased productivity and efficiency in other southern hemisphere producers. |

|

Availability of water and irrigation infrastructure. |

Relatively high economic and political risk. |

Possible increased FDI in Argentina. |

Possible biotech innovations reducing cost of fruit storage (delayed maturation) thus reducing advantages of SH production. |

|

Long history of apple and pear production. General community resources. |

Inflexible labour markets. High labour costs due to competition from high-revenue industries (in particular energy). |

Presence of some large, multinational producers and exporters. |

Possibility of entrance of exotic plant diseases. |

|

Potential contribution of Public Institutions (INTA and SENASA). Availability of general agronomic, accounting and engineering expertise. |

High cost of capital, credit/capital availability. High costs of inputs due to high taxes. Time and possible red tape delays for importing inputs. |

Possibility of upgrading technical and market know-how. Increased quality with use of IT for production, marketing, storage and exports. |

Variability of the real exchange rate. |

|

General managerial capabilities. |

Availability of technical know-how in some specific areas. |

||

|

Absence of serious political threats (wars). |

Thin market co‑ordination/information conditions faced by some producers. |

Possibility of improving climate forecasts thus reducing damage from wind, frost and hail. |

|

|

Inefficient value-chain channels for domestic consumption. |

|||

|

Reasonably competitive domestic wholesale and export sector. |

Lack of research on determinants of firm-level management and production efficiency. |

Possibility of improving organisation of medium producers through consortium type enterprises. |

|

|

Possible below-average size of numerous firms. |

|||

|

Production risks: high winds or hail (damage). |

|||

|

Logistics costs both for domestic and export markets. |

Source: Lema and Gallacher (2018[1]).

9.3. The viticulture value chain

Description of the value chain

Production

In Argentina the viticulture value chain includes a set of productive linkages oriented mainly to the production of wine and must. It spreads from grapevine farmers, farmer co‑operatives, winemaking companies, winemaking co‑operatives, private wineries and retailers to consumers. The principal producing regions are in the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan in the west of the country, where most of the production is concentrated, together with provinces of La Rioja, Salta, Catamarca, Neuquén and Río Negro. Mendoza province accounts for 71% of the area planted with grapevine and 76% of the production of wines, and San Juan province represents 22% and 18%, respectively. In these two main producing provinces, the value chain has an important economic role, both in terms of share of the total production value and employment (Lema and Gallacher (2018[1]) and Table 9.7).

Table 9.7. Vineyards and planted area, 2015

|

Province |

Number of vineyards |

Planted area |

Percentage of total planted area |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mendoza |

16 510 |

159 649 |

71.05% |

|

San Juan |

5 119 |

47 394 |

21.09% |

|

La Rioja |

1 237 |

7 449 |

3.32% |

|

Salta |

267 |

3 144 |

1.40% |

|

Catamarca |

1 251 |

2 678 |

1.19% |

|

Neuquén |

90 |

1 751 |

0.78% |

|

Rio Negro |

269 |

1 676 |

0.75% |

|

Córdoba |

127 |

278 |

0.12% |

|

La Pampa |

14 |

243 |

0.11% |

|

Other provinces |

165 |

443.7 |

0.20% |

|

Total |

25 049 |

224 706 |

100% |

Source: Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016.

The land structure of grapevine production suggests that 60% of farms have less than five hectares but only represent 14% of total vineyard land, while only 8% of total vineyards have more than 25 hectares and represent 45% of the total land destined to vines (Table 9.8). Regarding the age of plantations, 36% of the planted area is less than 15 years old, while more than 42% exceeds 25 years.

Table 9.8. Grapevine farms structure, 2016

|

Hectares |

Number of vineyards (%) |

Area (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

less than 5 ha |

60 |

0.14 |

|

5-15 ha |

25 |

0.25 |

|

15-25 ha |

7 |

0.16 |

|

25-50 ha |

5 |

0.18 |

|

50-100 ha |

2 |

0.14 |

|

more than 100 ha |

1 |

0.13 |

Source: Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016.

Grape varieties for wine production predominate in vineyards, with approximately 92% of the total planted area in year 2015. Grapes for fresh consumption represent 6%, and raisins 2%. Red varieties are the most significant (54%) in the total area planted with grapes for wine, followed by pink (26%) and white (20%). Since the mid-nineties the production of varietal high-quality wines expanded, and red varieties increased the planted area by 61% between the years 2000 and 2015. Pink and white varieties decreased their participation by 22% and 19%, respectively, during the same period.

In 2015, approximately 67% of the area planted with wine grapes were varieties of high quality wine, totalising 139 000 hectares. Vineyards of high‑quality varieties usually have lower yields and higher prices. Malbec is the largest high-quality red variety in Argentina; it is followed in importance by Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah. The Malbec variety covers the largest number of hectares, and the planted area has increased 141% since 2000 (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016[10]).

The total planted area has remained approximately constant at 224 000 hectares in the last 15 years, and the variability of grape production is mostly due to climatic issues. Variability in production of grapevine was relatively large in the period 2005-16, with the highest production of 3 million tonnes obtained in 2007, and the lowest level due to frosts, hail and rains in 2016 – less than 1.8 million tonnes (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016[10]).

In 2016, a total of 12.7 million hectolitres of wine and must were produced. Figure 9.2 shows that on average, 75% of the total production correspond to wine production and 25% to must production. The production of must has been increasing in the last decades, driven by external demand. Around 85% of must production is exported as concentrated must; by contrast, 20% of wine production is exported and 80% is consumed domestically.

Figure 9.2. Grapes, wine and must production

Even though the local practices, on average, are lagging relative to international standards, the technological environment of grapevine production has undergone a radical transformation in the last twenty years, regarding adoption of modern technologies and the diffusion of agricultural practices. Relevant innovations were related to greater professionalisation of agriculture, adoption of high-quality varieties, the use of the anti-hail systems, drip irrigation and the introduction of modern training systems for canopy management (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

The most important technological change in the last two decades was the introduction of grape varieties with a high oenological quality, mostly imported from Europe. This is part of a change in the production strategy from high yields per hectare and low quality, to low yields and high quality (and prices) of grapes and wine. The expansion of the planted area with Malbec varieties is a clear example of this strategy. The total planted area of this variety was, on average of 9 000 hectares in Mendoza and 1 000 hectares in the rest of the country between 1993 and 1999 (4.8% of the total planted area). In 2013 these figures were 31 000 and 4 800 respectively, covering 16% of the total planted area. High-quality oenological varieties increased from 52% of the total area in 2002 to 67% in 2015.

Despite its rapid adoption, pressurised irrigation such as sprinkler and drip systems still represents a small percentage in the main production provinces of Mendoza and San Juan, where it is used in 19% and 16% of the planted area respectively. Its use, however, is higher in other provinces, reaching 45% in La Rioja, 57% in Salta and up to 94% in Neuquén (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016[10]).

Many producers do not have access to technological improvements because the scale of their vineyards determines high unit costs. In addition, the wine industry increasingly relies on exports and the sector is more vulnerable to changes in foreign markets, consumption and production. In response to these challenges, some small-scale producers are organised in co-operatives. Co‑operatives have been important players in the wine industry since the 1950s and wine is the second agro-industrial co‑operative sector in terms of value of production after the dairy. Usually, co-operatives are present in the departments with lower shares of the total production of grapes of the province. (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

From a total of 62 wine co-operatives in Argentina, 82% are in the province of Mendoza. The largest national-level co-operative is Fecovita, formed by 29 affiliated primary co‑operatives, more than 5 000 primary producers and 25 000 vineyards in Mendoza province. Fecovita provides many services to co-operatives members, and quite often, also to non-members suppliers: credit to finance harvesting, technical advice, insurance and a promise of buying wine at an agreed price to co-operative members. Fecovita is also active in providing a channel for selling grapes and information about prices and transactions in the market (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

An important public institution that regulates the value chain is the National Institute of Viticulture (INV). Despite the important economic deregulation process undertaken in the first years of the 1990s, INV still has a relevant role, controlling all stages of the production process from primary production to marketing. The INV has the power to impose regulations that range from requiring quality attributes (e.g. alcoholic content of wines), marketing rules (authorising or temporarily limiting the quantities of wine allocated to the domestic market), labelling and varietal identification rules.

Regulation has had a greater impact in the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan with an agreement that was reached through twin provincial laws in 1994. According to these laws, the wineries must allocate to the elaboration of musts a mandatory percentage of total grapevine production. The percentage is determined by the government of San Juan and Mendoza provinces on an annual basis, depending on the total vine production. The objective is to regulate the total production of wine and to support prices. In recent years, with the rising importance of noble varieties such as Malbec and Cabernet, the regulatory system based on quantities has begun to be publicly debated. For example, one proposal was a modification of the quantitative regulation to a quality model with more detailed harvest forecasts, based on specific data by regions and varieties (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2016[10]).

In 2004, another institution, the Argentine Viticulture Corporation (COVIAR), was created by a national law as a non-state public institution, with the participation of the national government, provincial governments and science and technology organisations with the aim of implement a Strategic Viticulture Plan (PEVI) that co-ordinates actions and policies along the value chain.

Packing/processing and retailing

There are approximately 700 wine-making firms in Argentina, of which 62% are oriented primarily to the domestic market, and 38% are export-oriented. Most of the exporting firms are in the province of Mendoza, where 88% of the wineries with export profiles are concentrated. In this province a large part of firms are small or medium enterprises, some 90% of the total of firms, counting for 8% to 5% of the total production. On the other hand, a mere three firms with an export profile and fifteen oriented to the domestic market account for more than 70% of total production.

In recent years, big wineries have gradually increased their role as drivers of the sector. The structure of the wine industry is characterised by some concentration in the processing stage. Few buyers and processors may have market power to determine price and marketing conditions for small and dispersed producers. In terms of its geographical location, consistent with the distribution of the vineyards, there is a high degree of concentration in the provinces of Mendoza and San Juan. Together, these provinces account for approximately 90% of a total of 1 000 wineries, with Mendoza's share consistently above 70% (CEPAL, 2014[11]).

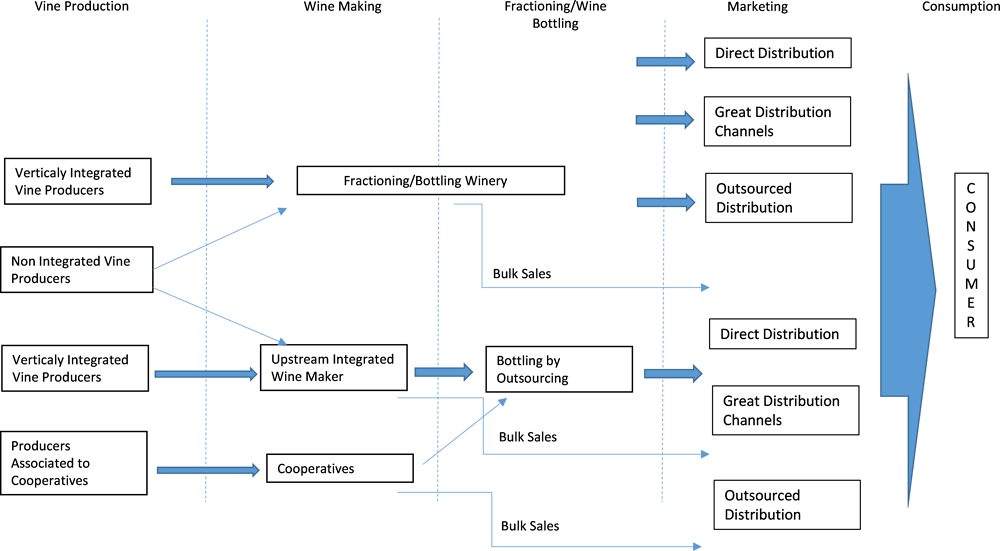

The processing of wine consists of two separate stages: elaboration and fractionation. Grapes are the basic input for wine, although they are part of other production activities such as for musts and juices. Wine is the main product and explains most of the economic results of the chain. The first industrial transformation begins with obtaining the juice of the grapes. This juice goes to the stage of alcoholic fermentation and, in the case of red wines, maceration. After maceration, the liquid is drained and separated from the solids. This concludes the basic process of winemaking. The second stage of industrial transformation involves the fractioning, bottling and packaging of wine (Figure 9.3 and Figure 9.4).

Both stages can be carried out in independent firms or in fully integrated wineries. Approximately 43% of Mendoza wineries are involved only in the first stage, selling the wine in the bulk market; the equivalent figure for the province of San Juan is 63%, and 61% for La Rioja. Some wineries (36% in Mendoza and 21% in San Juan) concentrate their activities exclusively in the second stage of the industrial transformation: bottling and marketing. The remaining wineries are vertically integrated, performing both stages of industrial transformation. The share of integrated wineries is significantly higher in the remaining provinces due to specific geographic and market conditions (CEPAL, 2014[11]).

The main characteristic of the wine industry is the great heterogeneity between firms in terms of scale, products, technology and strategy. There are winemaking firms that combine different structures of ownership (family, transnational, investment fund, national companies), activities (production and fractionation of wine, bulk sales, diversification or specialisation in high quality wine) and distribution channels (domestic or external markets) (CEPAL, 2014[11]). Despite this heterogeneity, it is possible to identify two large groups within the industry: wineries that produce table wines; and wineries focused on fine wines. These two sub-markets are characterised as much by their respective business models as by the type of product: one is based on large quantities (table wines), the other in quality differentiation.

The table wines are those with low prices and low unit margins, and economies of scale are the key factor in the production stage, with high concentration of sales in the market. Six large companies (Fecovita, Peñaflor, Baggio, Balbo, Orfila and Garbin) account for 80% of the market, while the remaining 20% is distributed among 30 wineries that sell wines, almost exclusively, in their regional area. The low margin strategy is replicated in the different stages of the table wine value chain, and the leading companies show different productive strategies and different degrees and forms of vertical integration. Figure 9.3 shows the actors of the table wines.

Figure 9.3. Value chain of table wines

Table winemaking is based on two main strategies: on one hand, the Peñaflor and Fecovita wineries are vertically integrated wineries that process, fraction and market their wines. They sometimes produce wine for small grapevine producers, using their grapes, in exchange for a percentage of the price. On the other hand, both Baggio and Garbin are firms without vineyards; they buy wine from wineries and sell the bottled (or packaged) wine in the wholesale and retail market. They market for small or medium wineries, accumulate stocks in their own warehouses and then sell the wine in the wholesale and retail market (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Fine wine can be separated in two sub-groups. The first one produces low‑priced fine wines, which are commercially known as “Seleccion”. This segment increased participation in the domestic market, attracting much of the demand from previous consumers of table wines. The strategy and competition of firms in this segment is similar to that in the table wine market: it based on low costs and high volumes, although quality is also a factor in the marketing strategy. Mergers and acquisitions during the 1990s created a large part of the current market structure, and the main players in this segment are the same leaders as among table wines, plus some traditional wineries (e.g. Finca Flichman or Viñas de Balbo) and some 30 medium-sized wineries. Figure 9.4 shows the value chain of this type of wine.

Figure 9.4. Value chain of fine wines

The second type of fine wines wineries focus on high price wines, the “Premiums” or the most expensive in the market. Large specialist companies dominate this segment, where a wide variety of price and quality strategies co-exist. The fine wines market is not driven by costs or volumes, but quality and product differentiation. Product differentiation strategies include advertising, using labels with the name and sometimes image of the winery, the variety of grape and the location. Given the importance of reputation and the specificity of assets involved, vertical integration plays a key role in this segment.

Forty-five companies produce fine wines for the domestic and export markets, showing a high degree of vertical integration. Some 33% of the grapes used by the fine wine wineries are from their own vineyards, while the rest is provided by implicit contracts with long term relationships. Two wine makers are relevant, by size and reputation, in this market, The Catena Group and Chandon wineries.

The growing importance of wineries with an export profile is a result of the modernisation and opening-up process that Argentine viticulture went through in the last two decades. However, the historical importance of the domestic market remains, accounting for almost 80% of total sales. With a clear focal point in the province of Mendoza, the growing internationalisation of the sector is gradually extending to the rest of the country, with a dual structure in terms of the size of the wine firms. Despite the large number of firms, there is some concentration in terms of volume. The two leading fine wine companies account for more than 40% of production, the twelve biggest firms account for 70% of the market and with the remaining 30% divided among 700 small wineries.

Exports and competitiveness

Until 1990, Argentina’s wine exports were occasional and focused on non-varietal wine and must. Rather than being the driver of the business, they were a way to sell the surplus of the wine industry. The deregulation process of the 1990s radically shifted the focus of the industry and boosted investment. The industry and primary producers started to look at the international markets, which demanded high-quality products. To achieve these higher standards, technological improvements and investments were introduced along the value chain.

Foreign investors in the wine sector were attracted by the relatively low price and good quality of land, while local investors were attracted by its promising perspectives in terms of high quality wine exports. Both groups had a wide range of investment options, from buying existing wineries or building new ones to acquiring land or vineyards.

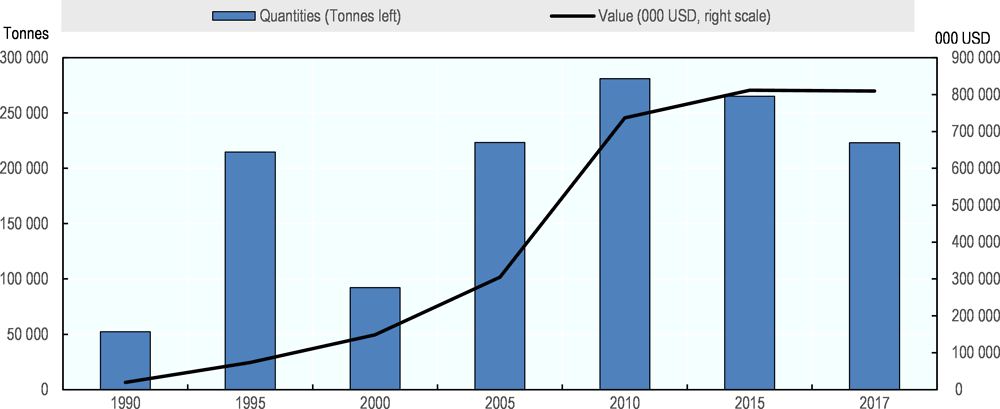

Argentine exports grew both in volume and value (Figure 9.5). The high increase in values suggests an improvement in both price and quality of the wine sold in international markets. Exports of varietal wine have increased steadily in terms of quantity and price per litre, but this is not always the case for non-varietal wine. Both non-varietal wine and must behave as commodities, with low margins and profitability linked to high exported volumes (Ruíz, 2011[12]).

Figure 9.5. Argentina wine exports

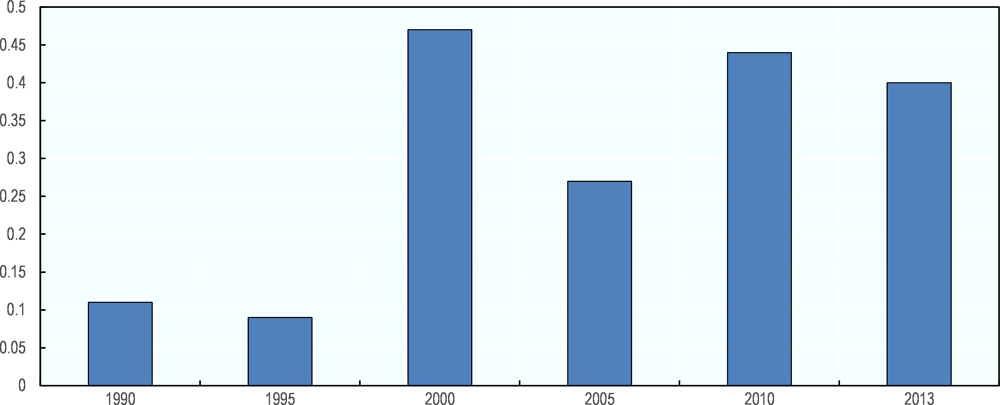

The price received for Argentine wines as a proportion of the best-rated French wines can be used as an approximation to the average improvement in their quality and to explain the increase in export values. Figure 9.6 therefore shows how the ratio of Argentine/French wines improved considerably from 1990 to 2013. Several Argentine winegrowers and investors innovated and succeeded in producing world-class wines locally, driven by the economic and institutional changes of the 1990s. A variety of investments on frontier technology and equipment and innovation paths were undertaken by industry participants in the process of internationalisation of Argentine wines (Elías and Ferro, 2018[13]).

Figure 9.6. Wine export price as a proportion of French wine export prices

SWOT analysis and challenges for the value chain

Argentina has environmental conditions that allow high-quality production of grapes and wines, giving it a comparative advantage over other producers. In addition, the country’s geographical diversity allows the production of wines that are differentiated by production areas, varieties and styles. Dynamic actors from primary producers to foreign companies installed during the nineties add to Argentina’s strengths. The presence of these dynamic actors is essential both to take advantage of the new conditions of global demand and to overcome the threats facing the wine value chain (see SWOT analysis in Table 9.9).

Argentina has a long tradition of wine co-operatives among small and medium‑scale producers. Approximately 20% of its table wine is produced by co‑operatives. This has helped the subsector to generate volumes and obtain bargaining power by obliging it to co‑ordinate a diversified supply. At the same time, it has ensured a very broad export portfolio, with different grapes, wines, qualities and prices, which is an advantage. Products other than wine such as must, concentrated juices, table grapes and raisins also contribute to the value chain.

Argentina’s Malbec variety is emblematic of the country’s viticulture, and its international recognition contributes both to the country’s brand and to that of its wines. Malbec aside, Argentine wines have not yet developed an internationally consolidated image, nor does the country have recognised brands in the world market. The diversification in export destinations for its wines does not allow it to achieve a significant share in target markets. The development and communication of an identity and a country image is a key element for consumer preference. To this end, continuous work toward the construction of the “Argentine wines” brand is required, as is boosting the international recognition of certain wineries, wine-producing regions and high-end wines.

Table 9.9. SWOT analysis of the viticulture value chain, 2018

|

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

Opportunities |

Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Comparatively advantageous climate, geographical diversity. |

Insufficient internal linkages along the value chain. |

Changing consumer preferences. |

Decrease in local wine consumption. |

|

Dynamic actors. |

Weak collective strategies. |

Targeting key markets. |

New producers with high competitiveness. |

|

Diversified supply. |

Low participation and recognition of Argentina in world markets. |

Decreasing commercial expansion of traditional wine producers. |

Trade barriers and non‑tariffs measures. |

|

Malbec as an emblematic variety, an icon of national viticulture. |

Lack of financial markets and local investments. |

Identity and country image. |

Increasing bargaining power of the retail marketing chains. |

|

Domestic market: Argentina is consuming approximately 75% of domestic production. |

Weak research and development, and training and extension services. |

Quality improvement and innovation in organisations. |

Few players in the must market (US-California). |

|

High competition in fine wines. |

Inefficiency in vineyard production managerial problems. |

Development of wine tourism. |

|

|

Long tradition of producer co‑operatives. |

Insufficient adaptation to changing markets, to market demands. |

Increase of wine sales in supermarkets. |

|

|

|

Negative perception of Argentina as a reliable supplier in international markets. |

|

|

|

|

High cost of glass for bottles, domestic suppliers with oligopolistic power and high tariff protection. |

|

|

Source: (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

The viticulture value chain faces several challenges, insufficient internal linkages being among them. For instance, a lack of co-ordination exists between primary producers and wineries. The dominant position held by the wineries allows them to transfer market instability and unpredictability to the primary producers, who are already exposed to significant weather risks. Meanwhile, a lack of horizontal integration among small primary producers inhibits co‑ordination and reduces their bargaining power. A need for greater co‑ordination between the productive sector and other components of the value chain, such as suppliers of related industries, also exists. The country lacks organisations, institutions and collective strategies that work towards strengthening both the internal market and the export market (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

Market concentration in industry and potential market power is an issue in the table‑wine market. Greater competition is observed as the quality of the wine increases. Independent wine producers appear to be the weakest link in the chain. Some 5 000 small and medium producers are co-operative associated in the secondary co‑operative Fecovita, which takes advantage of the volume integration, producing approximately 20% of all table wine.

Argentina has limited financial markets and local investors. The influx of foreign capital to the country during the 1990s was largely responsible for the important restructuring that viticulture went through in the last twenty years. Currently, the absence of alternative financing mechanisms to commercial banks limits investment and innovation. As a consequence, research and development (R&D) and training and extension on wine is weak. These shortcomings have led to inefficiency in vineyard production that is transformed into low quality grapes in certain regions. Argentina has also limited adaptability to changing markets. In spite of the varietal reconversion that took place in the 1990s, there is still insufficient adaptation to market demands. This is manifest in a shortage of high-quality red varieties and an excess of pink grapes.

9.4. Policy assessment and recommendations on value chains

During the last decades, growth and innovation in Argentinian agriculture has focused on grain production in the Pampas region. The value chains of the other regions (the “regional economies”) suffer from low productivity and lack of dynamism. But this is not unique to the pear-and-apple and wine subsectors analysed in this chapter. Key bottlenecks in the regional economies have not been widely addressed by public policy, and public investment on agricultural infrastructure, R&D, extension and technical assistance, for example, has been limited. This is particularly the case for small producers and for production located in economically poor regions, such as tobacco.

Argentina’s apple-and-pear value chain contains a duality in its structure, whereby farms which are fully integrated into value chains (usually large and medium-size ones) coexist with less integrated farms (mostly small-scale ones). Small‑scale farms of apples and pears have several difficulties, particular the low use of technology, deficient pest control, old orchards, and in general, very limited investments at the farm level. In terms of agricultural policy, the apple-and-pear value chain has received limited support over the years. Orchard renewal is a crucial factor for the improvement of fruit quality, as is reduction in pest control and labour costs. More recent orchards are generally planted with varieties better adapted to current market conditions. These are characterised by plant densities, plant size and plant arrangements that allow improvements of land and labour productivity. Pear production is slightly more competitive than that of apples.

Until the 1990s, Argentina’s viticulture value chain was oriented to the domestic market, with occasional exports focused on non-varietal wine and must. During the 1990s, along with the deregulation of the industry, significant investments took place. Foreign and local investors were attracted to the wine sector by the relatively low price and good quality of land, and the promising perspectives in terms of high quality wine exports. Investors developed a wide range of strategies: buying existing wineries, building new ones, acquiring land with existing vineyards and planting in new areas. Argentine exports grew with an increase in the prices and qualities of the wine sold in international markets.

Key public goods in the areas of knowledge and plant health and food safety are provided by public agencies such as INTA and SENASA. However, the innovation system and the public provision of R&D have delivered its main outcomes in the grain sector. The regional economies outside the Pampas region have not been the focus of INTA. INTA’s knowledge and technical assistance for these productions could be strengthened by a system of technical assistance by value chain, focused on R&D, extension services to small-scale producers, and pest control.

The future of some small-scale farmers may not lie in agriculture, and non-farm economic alternatives should be explored for a gradual re-allocation of resources such as labour, land and irrigation, and as part of technical and business advice. This could be achieved, for instance, through an increased emphasis on understanding the economics of fruit production, markets, industrialisation and logistics. Areas of knowledge to be analysed and transferred include: production efficiency and technology adoption, returns from orchard renewal and irrigation, managerial decision-making, risk management, marketing and negotiation in the production/processing interface, financial constraints, economies of size/scope, water economics, use of geographical information and monitoring systems, and the regional labour market and its impact on pear and apple production (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

The survival of small-scale producers of pears and apples is linked to the possible emergence of organisational forms that allow them to participate directly in the benefits accrued through the value chain. Additionally, as co-operatives have limited popularity, new emerging alternatives for organisational structures for improving access to markets by small and medium-sized farmers could be explored. Different types of alliances and forms of integration between the different links in the value chain may successfully compete with larger, multinational operations. A small joint private-public group could analyse and identify alternative organisational forms for the sector.

Two governance structures in the wine production chain coexist. Quality varietal wines are predominantly produced with grapes from own production and through vertical integration. Meanwhile, the production of common or table wines is co-ordinated through the market, with transformation services predominating and low vertical integration. There is a lack of co‑ordination between primary producers and wineries for better management of the problems the former face: market instability, unpredictability and climatic risk. Small primary producers could improve their horizontal integration, which would enhance co‑ordination and increase bargaining power. Finally, there is a need for greater co‑ordination between production and other components of the value chain, such as suppliers of related industries. This is particularly so for the provision of public goods and services such as market information, climatic services and technical support for risk management, all of which would contribute significantly to governance of the value chain.

Viticulture is among the most regulated sectors of the Argentine economy, through the National Institute of Viticulture (INV). Despite the deregulation of the 1990s, the state has some control of all stages of production; public regulation can complement private standards and enhance both public and private efficiency. Potential improvements in regulations include the simplification of procedures and mechanisms of command and control in wine production and export, the distinction between table and fine wines, and the improvement in forecast systems for primary production.

A limiting factor in the viticulture value chain has been the absence of a specialised institution to orient its innovation and transformation processes within a long-term plan, despite COVIAR’s attempt to develop a Strategic Viticulture Plan (PEVI). For instance, sector-wide quality improvement and innovation in organisations allows increases in quality and competitiveness to be achieved. Organisational innovation in the industry would help to build networks of knowledge and experience, to comply with appropriate standards and export specialisation, to co‑ordinate within the value chain from primary producers to wineries, to improve distribution and marketing systems and to boost R&D, extension and training in new technologies.

Increased participation in export markets is a necessary condition for growth of the apple‑and-pear and viticulture value chains. Argentina’s domestic demand for food can be expected to increase primarily as a function of (relatively low) population growth, and only secondarily as a result of per-capita income growth. A search for new markets is crucial. The government could develop agricultural promotion offices to facilitate information and access to main importing countries.

References

[6] Ablin, A. (2012), El Supermercadismo Argentino. Alimentos Argentinos, Ministerio de Agroindustria, http://www.alimentosargentinos.gob.ar/contenido/sectores/niveldeactividad/08Ago_2012_supermercado.pdf.

[11] CEPAL (2014), Estudios de las estructuras de mercado de complejos agroindustriales. Cadena vitivinícola, Documento nº 3 - parte 7, Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), Buenos Aires.

[13] Elías, J. and G. Ferro (2018), “Understanding innovations and the diffusion of knowledge in new world wines: Conceptual and experimental innovations in Argentina”, Working Paper UCEMA.

[4] Hak, L. (2009), “Frutícolas retornan a las cooperativas para salvar negocio”, Ámbito Financiero July 24, 2009.

[1] Lema, D. and M. Gallacher (2018), Apple, pears and viticulture production in Argentina, Background report for the OECD Review of Agricultural Policies in Argentina.

[2] Leskovar, E. (2016), La cadena de valor de manzanas y peras de Río Negro y Neuquén para Mercado Interno, Asociación Argentina de Economía Agraria. Reunión Anual, Septiembre 2016.

[7] Leskovar, E. (2015), Comercialización externa de manzanas y peras de río Negro y Neuquén: Aproximación a la identificación de canales relevantes, Asociación Argentina de Economía Agraria, Reunión Anual, Septiembre 2015.

[3] Ministerio de Hacienda (2016), Informes de Cadenas de Valor: Frutícola - Manazana y Pera, Subsecretaría de Programación Microeconómica, Ministerio de Hacienda y Finanzas Públicas Presidencia de la Nación.

[10] Ministerio de Hacienda (2016), Informes de Cadenas de Valor: Vitivinicultura, Sud Secretaria de Programación MicroeconómicaMinisterio de Hacienda y Finanzas Públicas Presidencia de la Nación Ministro de Hacienda y Finanzas Públicas.

[12] Ruíz, A. (2011), Prospectiva y estrategia: El caso del plan estratégico vitivinícola 2020 (PEVI).

[9] Sturzenegger, A. (2017), Producción de peras y manzanas en el Valle de Río Negro. Un programa de acción, Ministerio de Agroindustria (Argentina).

[5] USDA (2011), “Understanding cooperatives: Farmer cooperative statistics”, Cooperative Information Report 45, Section 13.

[8] Villareal (2011), Balance frutícola 2009-2010. Manzanas y peras, Secretaría de Fruticultura de Río Negro.

Notes

← 1. This section is based on the consultant background paper (Lema and Gallacher, 2018[1]).

← 2. The Herfindhal-Hirshman index is a measure of the size of firms in relation to the industry and an indicator of the amount of competition among them. A number below 0.01 (or 100) indicates a highly competitive industry. A result below 0.15 (or 1 500) indicates an un-concentrated industry. A number between 0.15 to 0.25 (or 1 500 to 2 500) indicates moderate concentration. And an index above 0.25 (above 2 500) indicates high concentration.

← 3. Belrose is a market intelligence firm located in the state of Washington, United States.

← 4. Production efficiency includes output growth, output variability, area of abandoned orchards, percentage of new varieties. Infrastructure: plant capacity and age, marketing system, irrigation availability, labour availability. Financing and markets: interest rates, inflation rates, property rights, distance to markets.