Export restrictions and taxes on soybean, sunflower, wheat, corn, beef, milk and poultry have depressed producer prices for most of the last two decades in Argentina. Export taxes were typically lower for processed products, while quantitative restrictions and export licences have particularly affected wheat and beef. Export restrictions have proved not to be an effective and sustainable instrument for reducing food inflation, although they did generate fiscal revenue, notably in years of high food prices on world markets. This type of measures may contribute to world market price volatility. Federal revenue from export taxes is not shared with the provincial governments and represented as much as 13% of all tax revenues and 3% of GDP in 2008, a year of particularly high world food prices. Since the end of 2015, policy changes to reduce or eliminate taxes on agricultural products moved in the right direction of reducing distortions. The more recent decision to tax all exports in response to the economic turmoil of August-September 2018 should help macroeconomic stability and set the stage for more sustainable fiscal revenue over the longer term. The new export tax does not discriminate a specific sector like agriculture and has a sunset clause by the end of 2020. It should be part of an on-going process to improve the tax system.

Agricultural Policies in Argentina

Chapter 5. Export taxes generate distortions and negative support to the sector

Abstract

5.1. Introduction

The largest agricultural policy transfers in Argentina are derived from trade policies, in particular export taxes, as shown by the PSE analysis in Chapter 4. Export restrictions have been used almost continuously for the last two decades in Argentina, and included not only taxes, but also a system of licences and quantitative export restrictions. The motivations behind these measures were threefold. First, generating fiscal revenue for the Federal Government, which has limited alternatives for collecting progressive taxes due to a small fiscal base, potential tax avoidance, and the particularities of sharing tax revenues with provinces. Second, promoting domestic processing industries with cheaper agricultural inputs and lower export taxes for processed products. Finally, depressing domestic food prices by restricting their export, as a social measure to benefit the urban poor. Notwithstanding this threefold motivation for the imposition of export taxes, this distorting policy has ultimately hampered primary producers and created significant policy uncertainties.

5.2. Export tax rates have been high and unpredictable

Policies which disadvantaged Argentina’s agro-food sector began in 1933, when a differentiated exchange rate was applied to agro-food exports (Colomé, Freitag and Fusta, 2010[1]). The application of export taxes on agro-food products began in 1955, when the exchange rates for exports and imports were realigned. Subsequently, export taxes were maintained at different rates until they were almost eliminated in the 1990s for one decade, before being re-introduced in 2002 (Figure 5.1).

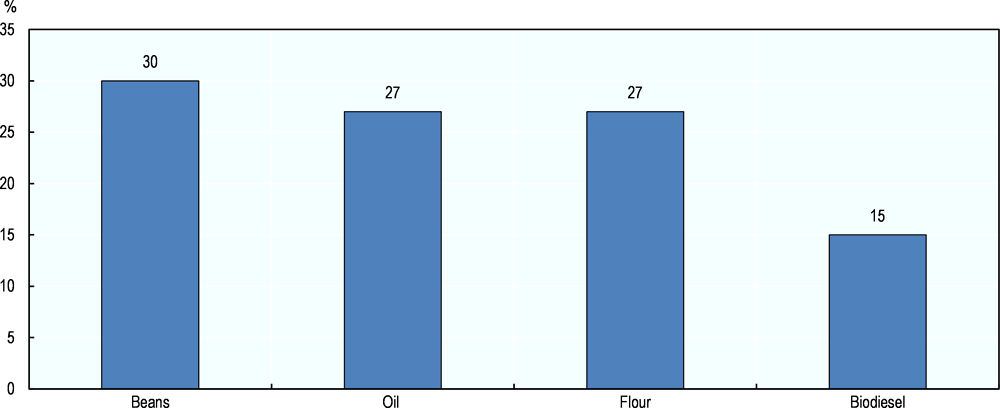

Figure 5.1. Export tax rates in Argentina

Note: The export tax rates on soybean, oil and flour were being reduced by 0.5% every month from January 2018 to September 2018. Since then a 12% tax on all exports is applied with a maximum of ARS per USD of export value.

In the last two decades, the export tax rates of agricultural commodities have been variable over time, decided in a discretionary manner through government decrees. The increase in export tax rates from 2002 to 2012 coincided with increases in the international prices of the main Argentinian export commodities. Some of these commodities – such as wheat, corn and bovine meat – are part of the basic diet of most Argentinians, and the government of the time introduced these and other export restricting measures with the explicit aim of reducing the price for domestic consumers. For a few months in 2008 a variable export tax system was established, with tax rates increasing with international prices, reaching record rates of up to 44% for soybeans. The simple average export tax rates for the period 2002‑15 were: 30% on soybeans, 28% on sunflower, 22% on wheat, 20% on maize, 12% on bovine meat and 3% on milk. In 2016 export taxes were eliminated except for soybean, for which there were reduced. To increase fiscal revenues the government established in September 2018 a temporary tax on all exports until December 31, 2020. The tax rate will be 12% and applied to all the goods and services exported including products from agriculture (Decree 793/2018). The tax rate will not exceed a maximum of ARS 4 per each dollar of exports of primary agricultural goods, and ARS 3 per dollar for the rest of products.

The export tax on soybean has had the highest rates and the highest tax revenue. Two decades ago, soybean was not a traditional component of Argentinian agricultural production, animal feed or diet. Export taxes on this oilseed had the explicit aim of raising fiscal revenue from increasingly profitable exports, whose international price had more than doubled during the 2000s. The tax rate on soybean exports climbed from 3.5% in 2001 to reach a peak value of 44% in March 2008; the rate was being gradually reduced in monthly steps of 0.5% to 30% in January 2018. In September 2018 the export rate specific for soybeans was reduced to 18% but the new tax rate on all exports is added on top. (Figure 5.1).

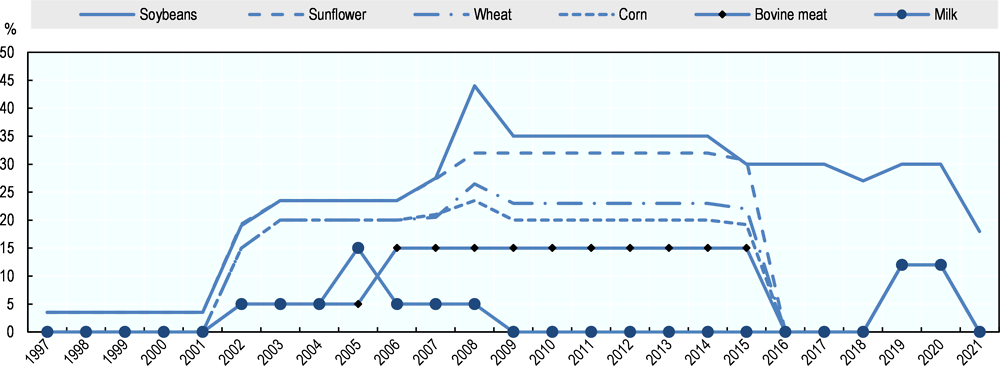

There is extensive literature on the damaging impact of Argentine export taxes on its agro‑food sector (Baracat et al., 2013[4]; Lema and Gallacher, 2017[5]; Sturzenegger and Salazni, 2007[6]; Regúnaga and Tejeda Rodriguez, 2015[3]). Export taxes create disincentives to export and produce, reducing domestic prices for producers and first buyers1 (Chapter 4). This is reflected in the Producer Support Estimates, with negative market price support (MPS) arising from the domestic prices for producers of main commodities being below the international prices at which exports compete (Figure 5.2). Only few commodities like pigmeat have positive market price support.

Market price support was relatively low (USD -142 million) in 2001, and its negative value peaked in 2014 at USD 22 billion, mostly from soybean and maize, followed by wheat and bovine meat. Export taxes began to be dismantled in 2015 and since then the negative MPS has been reduced significantly until 2017.

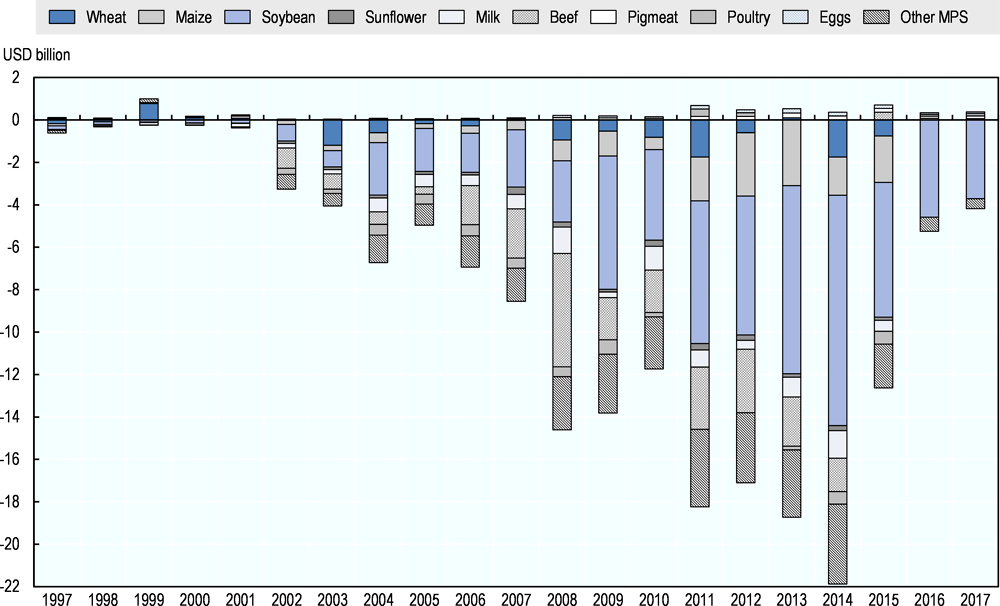

In almost all the value chains, export taxes varied with the degree of transformation. Exports of primary products were taxed at higher rates than processed ones. This was done to promote domestic processing industries and exports of products with higher domestic value added. For instance, the export tax on pasta used to be half of that on wheat flour, which latter was half of that on wheat grain. The “escalation” of export tax rates persists for soybean (Figure 5.3): the rate for beans was 30% as 1 January 2018, but only 27% for flour and oil, and 15% for biofuels. This practice mirrors import tariff escalation as defined by WTO, and it could be labelled as “tariff escalation on exports” (Regúnaga and Tejeda Rodriguez, 2015[3]).

Figure 5.2. Level and composition of Market Price Support (MPS) in Argentina

Note: MPS for fruit and vegetables was equal to zero over the period 1997-2017. See Annex C for the description of indicators.

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Estimates”, OECD Agriculture Statistics Database.

Figure 5.3. Export tax escalation

5.3. Export taxes have been a significant source of revenue for the federal government

Even if tax rates have varied over the years, export tax revenues have generally represented high shares of GDP and of total fiscal revenue in most of the years in the decades of the 1960s, 70s and 80s (Nogués, 2010[7]). Only during the 1990s were they hardly used. As export tax rates were increased in the 2000s, they became a significant source of revenue for the government, representing more than 10% of total fiscal revenue and an average of 2% of GDP in the period 2002‑15, peaking at 3.1% of GDP in 2008 (Figure 5.4). After the government decree of 2015, only export taxes on soybean remained, representing 0.6% of GDP. The persistence of export tax revenues reflect structural factors that make export taxes a readily available source of fiscal revenue for the government, and therefore difficult to reform.

Export taxes are part of a tax system that is characterised by weak enforcement with “low tax bases and highly distorting tax design”, “few people paying income taxes” and contributing “comparably little to reducing inequalities and creating strong incentives for informality” (OECD, 2017[8]). The system is complex with many taxes, the revenue of which is shared between the federal and the provincial governments. In this context, export taxes can be seen as an imperfect and distortionary alternative to tax rents from agricultural exports.

Figure 5.4. Revenue from export taxes

Source: Calculations by the authors based on official data (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[9]).

OECD (2017[8]) recommended to “undertake a revenue neutral tax reform”. In December 2017 a tax reform was approved as part of a process of improving the tax system (Law 27.430). The tax reform included: a gradual reduction over time in the maximum turnover tax rates to be applied by the provinces; a graduate reduction of the corporate income tax; phase-out of the financial transactions tax; and a reduction on employer social security charges for low income earners. The reform of export taxes was decided separately by successive decrees implying the elimination of agricultural export taxes except soybeans, which were subject to a gradual reduction planned for 2018 and 2019 (Decrees 133/2015, 1343/2016 and 486/2018). These measures were part of the effort to diminish distortions while at the same time meeting tight fiscal deficit objectives.

As part of Argentina’s federal structure, the revenue from most taxes is shared between the two main levels of government – federal and provincial – according to predefined parameters. This is the case of the corporate income tax or the value added tax. However, two taxes belong to only one of the two levels of government, and they are highly distortive measures: the export tax, imposed by the federal government, and the turnover tax, imposed by the provincial one.

Export taxes are decided by decree in a discretionary manner by the treasury and the executive of the federal government, and their revenue does not need to be shared between the central government and the provinces (Ministerio de Hacienda, 2018[9]). This circumstance has encouraged the recurrent use of export taxes as a rapid way to raise federal tax revenue. On the other hand, the provincial turnover tax (Impuesto sobre los ingresos brutos) is under the full responsibility of the provinces. This turnover tax is particularly distorting because it is levied on sales at every stage in the supply chain, without any deduction for the tax paid in earlier stages. This creates incentives for vertical integration and for avoiding the inter-provincial addition of value, and it acts like an interprovincial tariff barrier. The agro-food sector, as well as other sectors, is significantly burdened with these distortions.

The elimination of export taxes has far-reaching impacts in terms of total tax revenue and how it is distributed between levels of government. First, it reduces total tax revenue; second, it disproportionally affects the revenue of the federal government compared to the provinces; third, it can create even larger distortions through increases in the provincial turnover tax revenue. According to Nogués (2015[10]), the elimination of export taxes will increase domestic prices for producers and the turnover in the different stages of the value chain, automatically raising tax revenue from the turnover tax collected by the provinces. The reduction in export tax revenue would be partially compensated by increases in revenue from the provincial turnover tax, which is potentially more distorting than export taxes.

However, in response to the economic turmoil and the depreciation of the peso, in September 2018 the Government introduced a temporary tax on all exports that will be removed by the end of 2020 (Decree 793/2018). The new tax will be applied on top of the specific tax rate of soybeans. This measure should help macroeconomic stability and set the stage for more sustainable fiscal revenue over the longer term. To bring stability and certainty to the sector, export taxes should be part of the broad fiscal reform process.

An additional tax uncertainty for agricultural exporters arises from the tax refund system. Exporters are entitled to a total or partial refund of some of the domestic taxes paid, in particular of the VAT and the provincial turnover tax. However, these reimbursements have also created distortions and uncertainties on their own as they have tended to be discretionary, subject to political negotiations and often received after long delays (OECD, 2017[8]). The recent decree 1341/2016 has defined in a more transparent manner the maximum refund percentages for each group of commodities.

For Argentina, the decisions about how to eliminate distorting taxes have to be taken as part of the ongoing tax reform process, including federal and provincial taxes. Furthermore, fiscal reforms in a federal state such as Argentina are politically challenging due to their implications for the distribution of revenue collected by different levels of government. However, in the short term, export taxes – particularly if applied to all exports in the context of a large depreciation– may create lower distortions and be more effective to raise revenue than any other available alternative.

5.4. Quantitative restrictions on exports created additional disincentives

Export taxes are only one form of export restriction. Other restrictions include export licencing, export bans and quotas, and other non-tax measures. Quantitative restrictions on exports of some products comprising the basic food basket of Argentinians were imposed from 2006, including on wheat, maize, bovine meat and milk. These quotas were subject to discretionary management by the Ministry of the Economy and the National Office of Agricultural Trade Control (ONCCA), an agency within the Ministry of Agriculture, through a system of Export Operation Registers (ROEs). In 2011 ONCCA was dismantled and the management of the scheme was allocated to the Ministry of the Economy. Quantitative restrictions ceased to be applied in 2015 with the elimination of the ROEs for grains and the creation of a more agile system of Declaration of Sales Abroad (DJVE).

During the period 2002-15, export quotas were subjected to significant uncertainty and lack of transparency due to the absence of a domestic law governing both the restrictions and the allocation of export licences (Baracat et al., 2013[4]). On several occasions in this period, the government decided to ban exports of some products (bovine meat in 2006, and wheat in 2007 and 2013), or to close the export registers (ROEs). This distorted competition by creating economic rents for exporting companies that were awarded the licence, estimated at between 20% (Nogués, 2014[11]) and 26% (Baracat et al., 2013[4]) of the price, while leaving other companies with lower domestic prices.

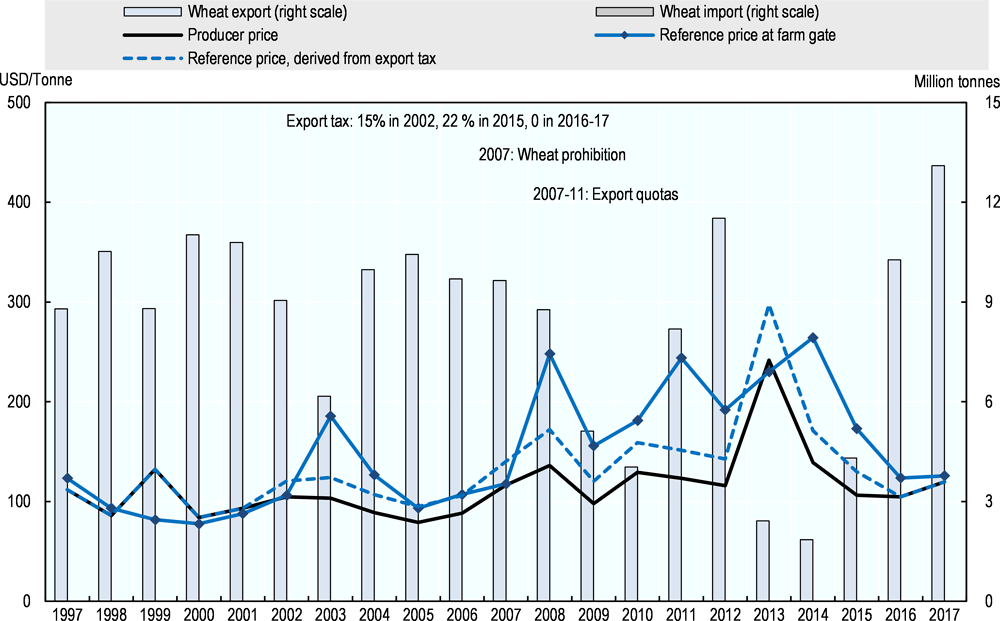

These quantitative restrictions on exports are an additional barrier to trade that is reflected in the market price differentials between the domestic Argentinian and world markets. The calculation of the market price differential for the Producer Support Estimate (PSE) reveals that the observed export unit value (adjusted EUV or reference price) of wheat was for many years significantly higher than the producer price augmented by the export tax (Figure 5.5).

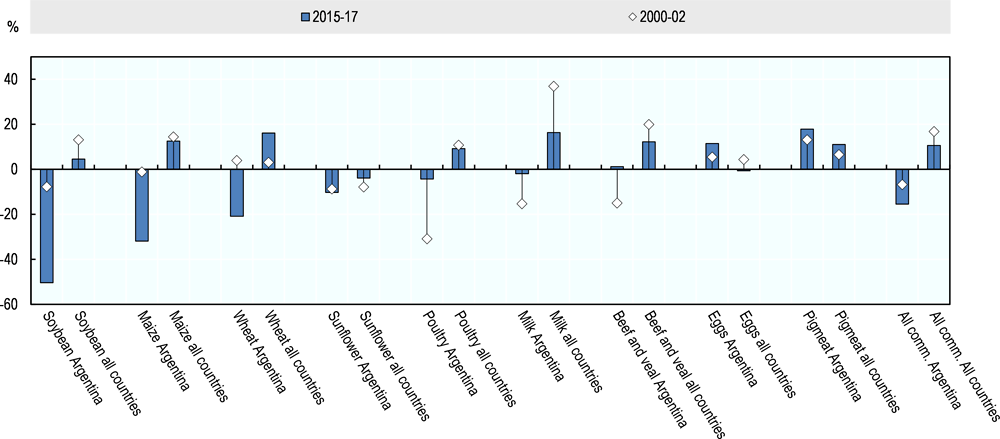

Most products have negative commodity-specific support that, as percentage of farm revenues, is larger than the corresponding export taxes (Figure 5.6). In the case of maize, soybeans and wheat the %SCT (Single Commodity Transfers) represented a burden for producers of more than 50% of gross receipts in the peak years, well above the export tax rates. Furthermore, Argentina has not provided any payments to producers that could compensate for this negative support. The only payments based on output are for tobacco producers.

Some animal products like bovine meat and milk were also subject to export restrictions. However, their SCT is only marginally negative or even positive. This is due to the positive support that these producers receive in the form of cheaper feed crops. This partially compensates the negative support caused by export restrictions and the subsequent lower output prices. In some years the lower cost of feed fully compensates for the lower output prices and brings MPS and SCT for milk and bovine meat to virtually zero or even into positive territory. In spite of this positive support, bovine meat was substantially affected by the policy uncertainty and drought in livestock producing areas, and the number of animals decreased by almost ten million or 17% between 2008 and 2011. Pigmeat is the main commodity with a systematically positive SCT in Argentina.

Figure 5.5. Wheat price differentials: Export taxes vs quantitative restrictions

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Estimates”, OECD Agriculture Statistics Database.

Figure 5.6. Single Commodity Transfers, Argentina and all countries, 2000-02 and 2015-17

Note: Commodities are ranked according to the value of % SCT in 2015-17 in Argentina.

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture Statistics Database.

The negative values of the SCT for most commodities reflects the fact that farmers in Argentina were not supported with policies, unlike farmers in most other emerging economies and in OECD ones. Furthermore, there have been significant transfers from producers to the government and the processing industries. For example, wheat and maize producers were supported by OECD and emerging economies with policy transfers, mostly highly distorting, that represented 16% and 12% of the value of production in 2015-17, respectively, while Argentine producers were burdened with negative transfers of more than 20% (Figure 5.6). Agricultural policies have harmed Argentine’s position in its main exporting markets: its exporters, who are subject to negative policy transfers, need to compete with those from other countries, some of whom benefit from distorting positive support from their governments.

5.5. Export restrictions distorted production without controlling food inflation

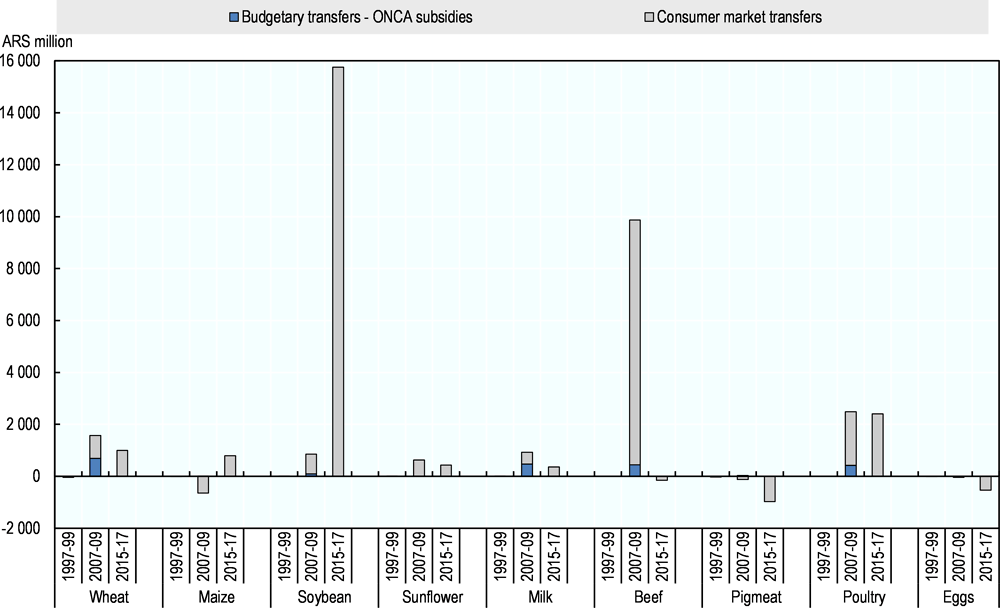

Some of the above export taxes and trade restrictions were implemented with the aim of reducing Argentinian consumer prices for the basic food basket. From 2007, the National Office of Agricultural Trade Control (ONCCA) provided subsidies to food processors as first buyers of mainly wheat, beef and milk, but also poultry, pork, maize and soybean (Figure 5.7). These subsidies were small compared to the size of market transfer, except for wheat and milk. After a congressional inquiry into its activities, ONCCA was closed in 2011. During the period 2007-10, the subsidies – together with export taxes and restrictions – had a direct impact on reducing the price at which the primary commodity was purchased by the first processor (Grundke and Foders, 2010[12]).

Figure 5.7. Consumer transfers

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Estimates”, OECD Agriculture Statistics Database.

However, the impact of these polices on the food prices for final consumers is much smaller, even if this is difficult to assess in Argentina due to the absence of reliable Consumer Price Indexes for the period 2002-15, in particular for food prices. Inflation started to rise to double digits in 2007 and reached 40% in 2014, while the Central Bank increasingly printed money to finance the fiscal deficit (OECD, 2017[8]). Inflation was starting to be contained up to 2017 and the national statistics institute, INDEC, began the publication of a new series in 2016.

Despite this lack of statistical information, there is evidence that the use of trade policies to control inflationary pressures has not been effective. The share of the primary product in the price of the final product is too insignificant for these measures to have a relevant impact on consumer prices. For instance, wheat flour represents only 10% of the price of bread, and export restrictions were reported to reduce the domestic price of wheat and flour, but not of bread and other derived products (Regúnaga and Tejeda Rodriguez, 2015[3]). These results are confirmed by econometric analysis that estimate an impact of only 1% on the consumer prices for wheat-derived products (Calvo, 2014[13])

The large size of export taxes is likely to have had significant impacts on production decisions. It has been argued that, despite the higher tax rates on soybean, the market for this product was more predictable than that for wheat or maize, which were subject to uncertain quantitative restrictions. This predictability, together with higher international prices and lower requirements on investment and working capital, could have created additional incentives for the expansion of soybean production compared to other crops (Baracat et al., 2013[4]). There is also evidence that export taxes created a bias against yield-enhancing technologies and in favour of cost-reducing ones, favouring soybean production (Cristini, Chisari and Bermúdez, 2009[14]).

Furthermore, during the 2008 episode of price spikes, “export restrictions by major food exporters had strong destabilising effects on international markets. As more countries followed the first movers, volatility was exacerbated and the upward price movement was amplified. Export restrictions proved extremely damaging to third countries, especially the poorest import dependent countries” (FAO, IFAD, IMF,OECD, UNCTAD, WFP, the World Bank, the WTO, 2011[15]).

5.6. Import tariffs have played only a secondary role for agricultural commodities

Since the creation of the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) in 1991, Argentine tariffs essentially correspond to the former’s Common External Tariff (CET) (Table 5.1). In principle, tariffs among MERCOSUR members with mostly highly competitive and exporting agricultural sectors (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) are set at zero. Argentina is a net exporter of most agricultural products and the level of the CET tariffs is particularly relevant only for a few imported commodities. Several commodities produced outside the Pampas region such as wine, apples, pears and lemons (the so called “regional economies”) are exported but are not subject to export restrictions. For these commodities import tariffs are also not relevant.

Average and maximum applied import tariffs are lower for agriculture than for other products (Table 5.1). Only certain imported agricultural commodities are subject to import tariffs. For instance, pigmeat is the most significant imported commodity and the applied MFN tariff is 10%. In the past ONCCA also managed the Import Operation Register ROI that included pigmeat products. This is the only commodity that contributes with a positive market price support to the PSE. However, the magnitude of this positive support is small compared with the size of the negative support to most exporting commodities.

Import restrictions and tariffs affect agriculture’s access to inputs. Argentina has systematically used non-automatic import licenses since 1999 for a large set of manufactured products, including agriculture machinery and agrochemicals. There is evidence that during the period 2002-15 the licence mechanism created significant delays and administrative uncertainty (Baracat et al., 2013[4]). The Argentinian import licensing system has been the subject of several disputes in the WTO. The protection (through import tariffs) of the domestic production of agro-chemicals, fertilisers and machinery have created additional input costs that have been growing in recent years due to the increasing use of all these inputs in the new technological packages adopted by agriculture in the Pampas region (Sturzenegger and Salazni, 2007[6]).

Table 5.1. Tariffs on imports by product groups

|

|

Final bound duties |

MFN applied duties |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Product groups |

Average |

Duty-free |

Max |

Average |

Duty-free |

Max |

|

|

|

in % |

|

|

in % |

|

|

Animal products |

26.5 |

0 |

35 |

8.3 |

6.5 |

16 |

|

Dairy products |

35 |

0 |

35 |

18.3 |

0 |

28 |

|

Fruit, vegetables, plants |

33.8 |

0 |

35 |

10.0 |

5.6 |

35 |

|

Coffee, tea |

34.2 |

0 |

35 |

14.3 |

0 |

35 |

|

Cereals & preparations |

33 |

0 |

35 |

10.9 |

14.7 |

31 |

|

Oilseeds, fats & oils |

34.6 |

0 |

35 |

8.5 |

10.8 |

35 |

|

Sugars and confectionery |

33.3 |

0 |

35 |

17.6 |

0 |

20 |

|

Beverages & tobacco |

35 |

0 |

35 |

17.8 |

0 |

35 |

|

Cotton |

35 |

0 |

35 |

6.4 |

0 |

8 |

|

Other agricultural products |

31 |

0.7 |

35 |

7.7 |

10.4 |

20 |

|

Fish & fish products |

34.5 |

0 |

35 |

10.4 |

3.9 |

16 |

|

Minerals & metals |

33.8 |

0 |

35 |

10.1 |

7.2 |

35 |

|

Petroleum |

33.6 |

0 |

35 |

0.1 |

97.2 |

6 |

|

Chemicals |

21.4 |

0 |

35 |

8.2 |

1.4 |

35 |

|

Wood, paper, etc. |

30.2 |

0 |

35 |

11.2 |

3.3 |

35 |

|

Textiles |

34.9 |

0 |

35 |

23.3 |

0 |

35 |

|

Clothing |

35 |

0 |

35 |

35.0 |

0 |

35 |

|

Leather, footwear, etc. |

35 |

0 |

35 |

16.0 |

2.8 |

35 |

|

Non-electrical machinery |

34.9 |

0 |

35 |

13.4 |

11.8 |

35 |

|

Electrical machinery |

34.9 |

0 |

35 |

14.8 |

10.1 |

35 |

|

Transport equipment |

34.5 |

0 |

35 |

18.5 |

12.0 |

35 |

|

Manufactures, n.e.s. |

33.5 |

0 |

35 |

15.7 |

8.8 |

35 |

Source: WTO (2018).

5.7. Overall policy assessment and recommendations

Market Price Support (MPS) policies – either negative or positive – are among the most distorting forms of support to agriculture. Previously in Argentina, export restrictions and taxes were used heavily in pursuit of policy objectives related to fiscal revenue and control of food inflation to favour consumers and food processors. During agricultural price spikes, export taxes accounted for 13% of all fiscal revenue, but they were not effective in controlling food inflation. In this sense, the reduction of export taxes for agricultural products undertaken in 2015 and 2016 were movements in the right direction. They significantly reduced the size of market distortions created by negative market price support. Only soybean export remained taxed, which may affect relative incentives across the sector. The large size of the agro-food sector in Argentina makes the elimination of export taxes more challenging: it is likely to have positive impacts on GDP while increasing the government deficit and decreasing the world price of some of its exporting commodities (Piñeiro et al., 2018[16])2. The new temporary tax on all exports was introduced in September 2018 to raise government revenue and reduce its deficit.

Export restrictions are not only market distorting, they also generate uncertainty because they are decided and implemented in an ad hoc discretionary manner through government decrees with low transparency and predictability. This uncertainty creates additional distortions and disincentives for long-term investment. Furthermore, export restrictions and policy uncertainty have direct spillover effects in exacerbating volatility in agricultural world markets.

The first priority for agricultural export taxes in Argentina would be to accompany the gradual reduction in the tax rates with more certainty in the way they are determined, modified and implemented, in order to improve the investment decision environment in the agricultural sector and in the whole economy. The soybean exporting subsector and the rest of the agriculture sector could be more appropriately taxed through non‑sectoral, less distorting taxes for the whole economy, such as corporate and income taxes.

A first-best policy option is a fiscal system that replaces export taxes with less distorting measures. The tax system in Argentina should in the long term phase out distorting taxes like the provincial turnover tax and the federal export tax. The discussion about the potential substitution of these distorting taxes by other measures is not new in Argentina. Piffano and Sturzenegger (2010[17]) proposed the substitution of export taxes by less distorting taxes on rural property. OECD (2017[8]) proposes a phase-out and integration of the turnover tax into the existing VAT. The 2017 tax reform (Law 27.430) gradually reduces maximum turnover tax rates, while export taxes were reduced and modified by a succession of decrees: 133/2015, 1343/2016 and 486/2018. The decree 793/2018 introduced in September 2018 a temporary tax on all exports in response to economic turmoil when the economy began to stall and the currency depreciated.

Tax reforms need to combine the long-term objective of phasing out distorting taxes with short-term measures that facilitate the path to the long term and permit financing the government deficit. The decisions about the reduction of distorting taxes have to be taken considering the limited capacity of the whole system to collect fiscal revenues in a progressive and non-distorting manner. Additionally, the tax reform faces political and institutional complexities and needs to ensure that the new distribution of revenues is acceptable for both federal and provincial governments.

The long term reduction of export taxes should be part of the ongoing more ambitious tax reform process beyond agricultural policies, providing more stability and certainty as part of structural reforms, and preventing their future use as discretionary arrangements to close public revenue gaps. As part of such a package, provisions could be made to facilitate the consistent achievement of long- and short-term objectives such as the sunset clause in the Decree 793/2018 that expires in 2021, or temporary compensation arrangements.

Finally, the reduction in the taxes to the sector has to be undertaken in a manner consistent with other objectives. The expansion of the production of the main commodities and the use of existing or new technological packages could potentially increase environmental sustainability pressures (negative externalities). Those who increase these pressures should be subject to the “polluter pays principle” PPP rights (OECD, 2001[18]), It is therefore essential that any export tax reform should be accompanied by measures to offset potential negative environmental consequences and ensure any eventual costs to society as a whole are borne by those who generate them, strengthening the responsibility of producers in reducing negative agri-environmental impacts, as discussed in Chapter 7.

References

[4] Baracat, E. et al. (2013), Sustaining Trade Reform Institutional Lessons from Argentina and Peru, World Bank, Washington, DC.

[13] Calvo, P. (2014), Welfare Impact of Wheat Export Restrictions in Argentina: Non-parametric Analysis on Urban Households, UNCTAD.

[19] Cicowiez, M., C. Diaz-Bonilla and E. Diaz-Bonilla (2010), “Impacts of trade liberalization on poverty and inequality in Argentina: Policy insights from a non-parametric CGE microsimulation analysis”, International Journal of Microsimulations, Vol. 3/(1), pp. 118-122.

[1] Colomé, R., J. Freitag and G. Fusta (2010), “Tipos de cambio real y tasas de " protección " a la agricultura argentina en el período 1930-1959”, Anales de la Asociación Argentina de Economía Política. XLV Reunión Anual: Tipos de Cambio Real y Tasas de Protección a la Agricultural Argentina.

[14] Cristini, M., O. Chisari and G. Bermúdez (2009), “Agricultural and macroeconomic policies, technology adoption and agro-industrial development in Argentina: Old and new facts”, Argentine Agricultural Economics Review, Vol. XI/2, pp. 95-114.

[15] FAO, IFAD, IMF,OECD, UNCTAD, WFP, the World Bank, the WTO, I. (2011), Price Volatility in Food and Agricultural Markets: Policy Responses, Interagency report for the G20.

[12] Grundke, R. and F. Foders (2010), “The economic and social consequences of agricultural export taxes: A CGE – analysis for Argentina”, GTAP Conference paper.

[5] Lema, D. and M. Gallacher (2017), Producer Support Estimates: Argentine Agriculture 2007-16, The Inter American Development Bank.

[2] Ministerio de Agroindustria (2018), Sector background information provided by the Ministry of Agroindustry for the OECD Review of Agricultural Policies of Argentina.

[9] Ministerio de Hacienda (2018), Destino de la Recaudacion de los Impuestos al 30/03/2018, Dirección Nacional de Investigaciones y Analisis Fiscal, Subsecretaría de Política Tributaria, Ministerio de Hacienda de la Republica Argentina.

[10] Nogués, J. (2015), “Bareras sobre las exportaciones agropecuarias: Impactos económicos y sociales de su eliminación”, Serie de Informes Técnicos del Banco Mundial en Argentina, Paraguay y Uruguay No. 3.

[11] Nogués, J. (2014), “Rentas proteccionistas generadas por las políticas restrictivas sobre las exportaciones: Argentina”.

[7] Nogués, J. (2010), “Agro e Industria una interpretacion de la decadencia Argentina ente dos centenarios”.

[8] OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Argentina 2017: Multi-dimensional Economic Survey, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-arg-2017-en.

[18] OECD (2001), Improving the Environmental Performance of Agriculture: Policy options and market approaches, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264033801-en.

[17] Piffano, H. and A. Sturzenegger (2010), Una Propuesta de Cambio Tributario: Sustitución de las Retenciones a las Exportaciones Agropecuarias y Agroindustriales por un Impuesto al Valor de la Propiedad Rural Libe de Mejoras Productivas.

[16] Piñeiro, V. et al. (2018), Looking at export tariffs and export restrictions: The case of Argentina, IFPRI Discussion paper.

[3] Regúnaga, M. and A. Tejeda Rodriguez (2015), Argentina's agricultural policies, trade and sustainable development objectives, International Center for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD).

[6] Sturzenegger, A. and M. Salazni (2007), Distortions to Agricutural Incentives in Argentina, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Notes

← 1. The total amount of the export tax may not be fully transmitted into lower prices, particularly in the case of a large exporting country or a situation of market power.

← 2. Other quantitative studies also estimate small potential impacts in increasing poverty and inequality (Cicowiez, Diaz-Bonilla and Diaz-Bonilla, 2010[19]).