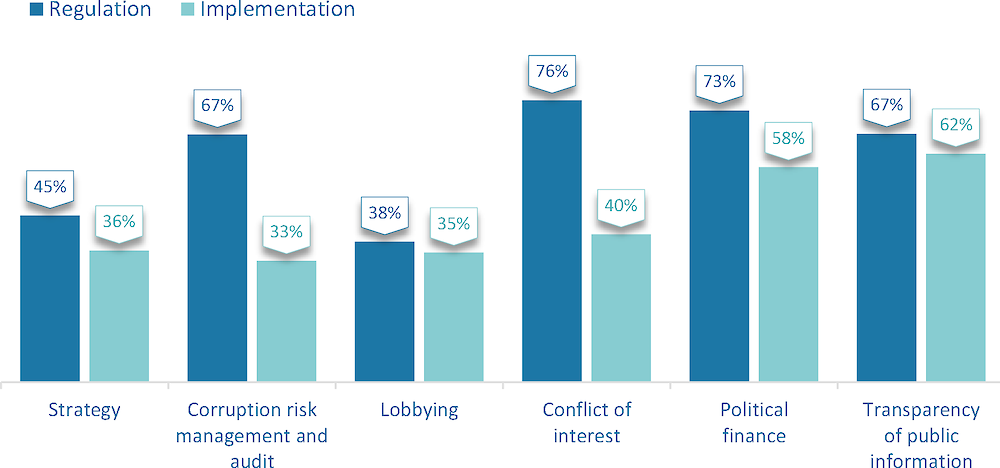

The implementation gap in these aspects of OECD countries’ integrity frameworks, where regulations and policies are not being implemented in practice, is significant. On average across OECD countries, anti-corruption and public integrity frameworks have an implementation gap of 17 percentage points, meaning the difference between the average share of standard regulations in place and the average of standard regulations implemented in practice. While it is important for OECD countries to set high standards and clear ways of working in their regulations and legislation, they should not over-rely on approaches based on the creation of rules. It is only by implementing regulations in practice through, for instance, improving office holders’ understanding of integrity standards and processes, setting clear responsibilities for overseeing aspects of the integrity framework, or monitoring and evaluating the performance of integrity policies and processes, that corruption risks are mitigated and integrity upheld. Strong legislation which is not implemented in practice can also lead to a sense of impunity and lower trust.

Moreover, it is vital that countries monitor the implementation of key parts of their anti-corruption and integrity frameworks more effectively. Monitoring is a continuous process, using the systematic collection of data on specified indicators to provide information on how far objectives are being achieved and progress made. For key aspects of their frameworks many countries are unable to evidence levels of implementation. Indeed, 60% of OECD countries do not monitor the implementation of their anti-corruption and integrity strategies. This lack of effective monitoring makes it impossible for them to evaluate whether their policies and processes are mitigating corruption risks and improving integrity in practice. Collecting data on implementation is thus fundamental to a strong integrity framework, and therefore countries unable to evidence the performance of important aspects of their frameworks could take steps to improve their monitoring processes.

The following chapters expand on these findings, and set out how key aspects of OECD countries’ integrity frameworks are currently performing.

A strategic approach can shift a country’s focus from ad hoc anti-corruption and integrity policies to a coherent and comprehensive integrity system. As Chapter 2 shows, the majority of OECD countries are now taking such an approach to corruption through the development of strategies adopted at the level of the government. However, these strategies are not as effective as they could be, remaining, for the most part, focused on traditional areas of corruption risk and anti-corruption work. In addition, on average 67% of the planned activities in countries’ strategies are implemented in practice. Countries should therefore focus on expanding the coverage of their strategies, supported by better consultation and use of evidence, and aim for better implementation through strong action plans and better monitoring and evaluation.

Effective internal audit and risk management reduce waste of public funds and vulnerabilities to fraud and corruption by reassuring managers that objectives are being met and risks effectively managed. Chapter 3 shows that countries’ regulations on risk management and internal control are strong, but their rules on internal audit need improvement. In addition, the implementation of risk management practices has not yet matured, and internal audit remains an underutilised governance tool against corruption.

Lobbying safeguards are among the weakest elements of OECD countries’ integrity frameworks. As Chapter 4 sets out the basic elements of lobbying frameworks are in place in less than half of OECD countries, leaving countries open to undue influence and exposed to new threats related to the green transition, AI and foreign interference. These risks are compounded by low levels of transparency around lobbying, which make it hard for the authorities to uphold the rules and the public to see who is influencing policy and decision making.

Countries have established strong regulations on conflicts of interest, to prevent the capture of policymaking by private interests. On average, 76% of OECD criteria for regulations on conflicts of interest are met. However, Chapter 5 demonstrates that countries’ defences against conflicts of interest remain vulnerable as their implementation and monitoring of required submissions need significant improvement. Processes to verify the accuracy of declarations could be stronger, as could measures for resolving conflicts and applying sanctions where the rules have been broken. And while some movement between the public and private sectors can improve policymaking through the exchange of knowledge and skills, most OECD countries’ data collection on this movement is not good enough for them to know whether they are mitigating integrity risks.

Political donations are an important means of expressing support to candidates and political parties, and a necessary resource for candidates and parties to run for office and represent the electorate’s interests. But, as explored in Chapter 6, where political financing is not transparent, there are significant risks that money may become an instrument of undue influence and policy capture. Although many countries ban donations from foreign sources or State-Owned Enterprises, anonymous donations remain a serious concern in many OECD countries, several countries do not have a strong central electoral commission, and many political parties do not comply with transparency requirements. Existing political finance regulations and institutions were designed to protect democracies in a national context many decades ago, and have not evolved to protect against foreign influence and transnational corruption risks. They therefore need an upgrade.

And finally, transparency is a core element of a functioning democracy and is underpinned by the right to access information about how governments and public institutions are working. Chapter 7 shows that while publication of data related to integrity is not always consistent, OECD countries have strong regulations and institutions to promote transparency. Importantly, new analysis shows that there is a positive and significant correlation between transparency of public information in practice (measured as the level of proactive disclosure of key datasets) and higher levels of public trust in countries with a trust deficit.