The world is facing interconnected challenges arising from the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, high inflation and rising interest rates, and the transition to low-carbon economies. The housing sector is affected, directly and indirectly, calling for appropriate policy responses. The sharp rise in energy prices has increased energy poverty in many countries, undermining affordability. Inflation and rising interest rates are testing the resilience of housing finance. The mainstreaming of remote work and search for better environmental quality are reshaping demand for real estate. This chapter reviews policy options to address these challenges and highlights potential trade-offs.

Brick by Brick (Volume 2)

1. Housing policies for the post-COVID-19 era

Abstract

Recent developments are posing interconnected policy challenges that, directly or indirectly, affect the housing sector. The run-up in energy prices has recalled the urgency to decarbonise housing in pursuit of agreed climate change targets. Tightening monetary conditions to quell high inflation in the wake of the pandemic and the energy price shock have increased housing finance costs. Repeated experiences of lockdowns and increased uptake of working-from-home practices may have changed work-life balances for good, as efforts to protect the environment are also reshaping housing markets.

This chapter examines how public policies can respond to these challenges. It identifies tools that policymakers can mobilise to provide affordable homes, ensure the efficient functioning of housing markets and preserve today’s and tomorrow’s environment while recognising that some policy options involve trade-offs among these goals. The chapter draws on the analyses and recommendations developed with greater detail in the rest of the book, including policy tools to decarbonise housing (Chapter 2), mobilise housing finance to fund the climate transition in addition to making the economy more efficient and resilient (Chapter 3), reap the benefits of an emerging new geography of housing shaped by the digital revolution and demand for environmental amenities (Chapter 4).

Monitor the impacts of the pandemic and cost-of-living crises on housing affordability

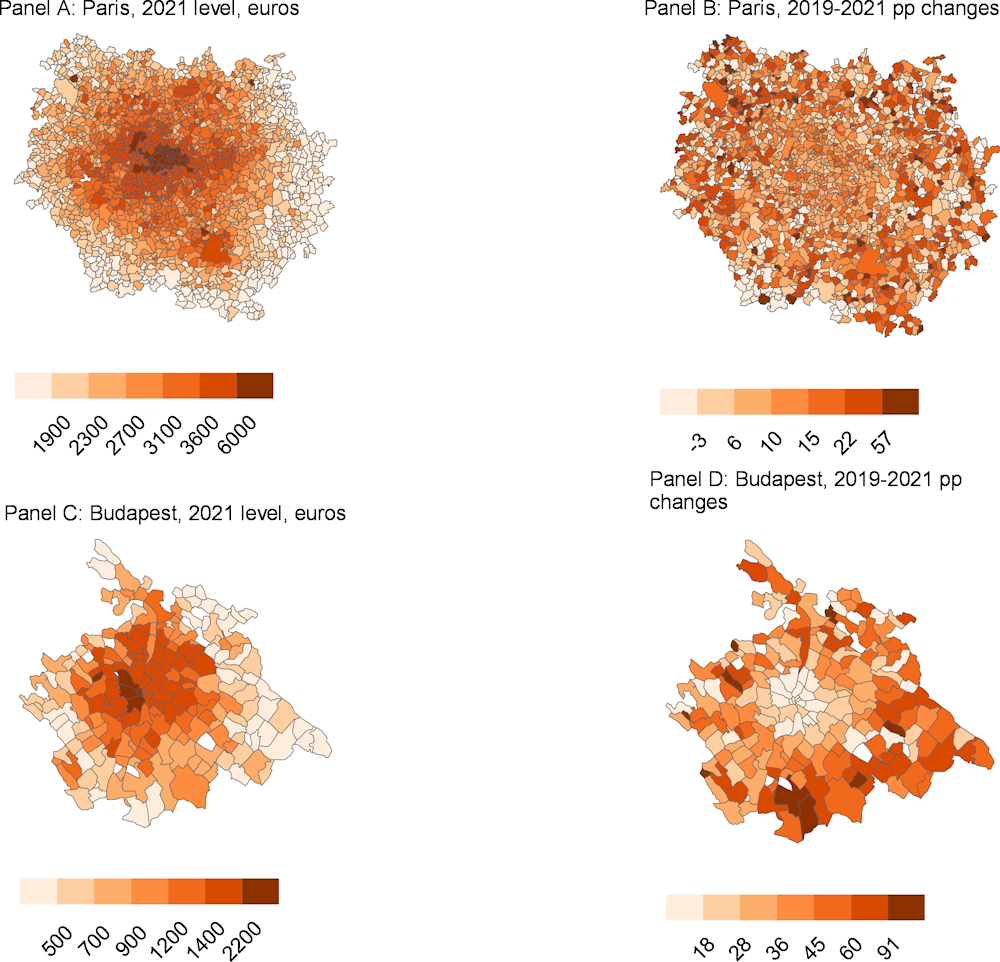

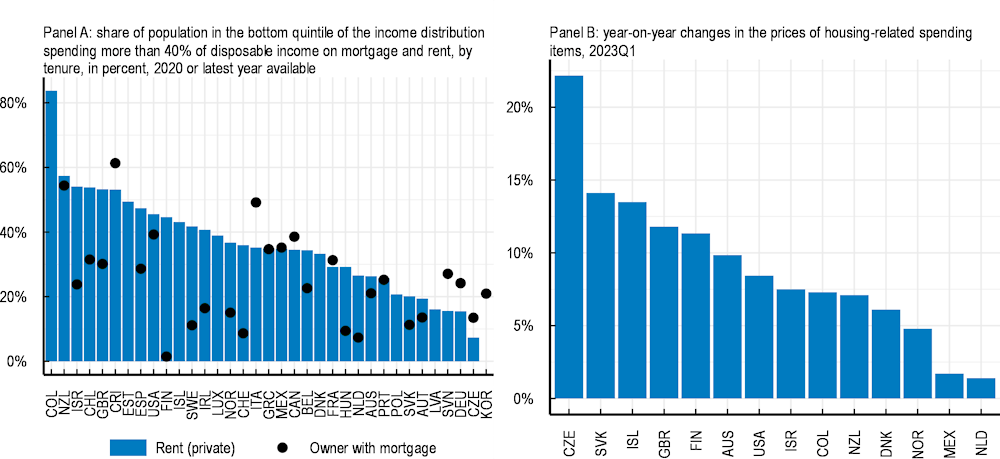

Low-income households, many of whom were already overburdened by rental and mortgage costs before the pandemic, are at risk of further housing stress. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, on average in the OECD, more than one in three low-income tenants in the private rental market spent over 40% of their disposable income on rent alone and were thus considered overburdened by housing costs (Figure 1.1, Panel A). Meanwhile, overburden rates among low-income homeowners with a mortgage reached 61% in Costa Rica, 54% in New Zealand and 49% in Italy, with considerable variation across OECD countries (Figure 1.1, Panel A). The sharp price increases in housing-related spending items experienced in 2022 exacerbate the pressure on household budgets and will likely increase overburden rates even further (Figure 1.1, Panel B). These developments should be monitored closely and evaluated together with recent income support and subsidies introduced by governments across OECD countries.1

Figure 1.1. Current inflationary pressures are likely to result in more households becoming overburdened by housing costs

Note: Panel B: Housing-related expenditures include i) actual and imputed rents for housing, ii) maintenance and repair spending and iii) water, electricity, gas and other fuels, and miscellaneous services, as defined in the Classification of Individual Consumption According to Purpose (COICOP). The figure covers only 14 economies because it excludes countries for which homeowners’ imputed rents data are missing in the source. By contrast, countries with missing data for maintenance and repairs of dwellings (Mexico and Colombia) are included in Panel B, as this group of items has a much smaller weight than imputed rents.

Source: OECD databases on Affordable Housing (Panel A) and Consumer Price (Panel B).

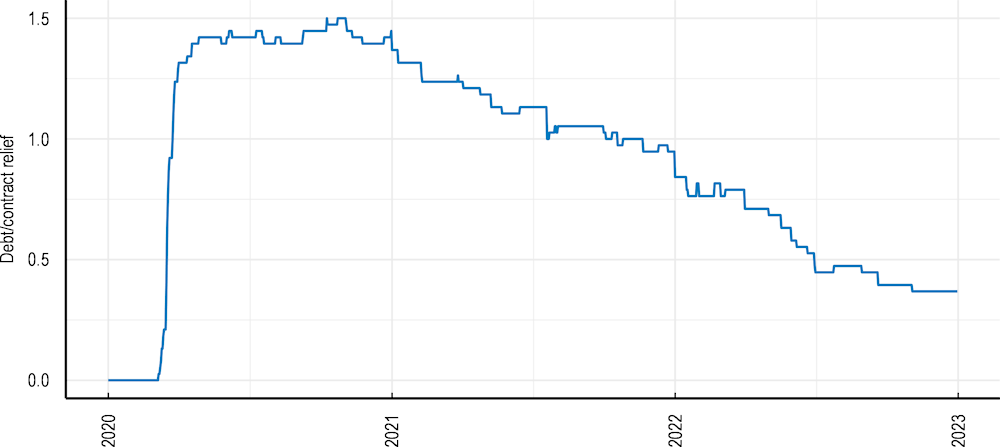

Higher interest rates, rising construction and labour costs, high house prices and the lifting of temporary COVID-related housing support measures carry implications for affordability over the near and medium terms (Figure 1.2). There is a risk of an uptick in evictions and homelessness (Box 1.1), as temporary housing support (such as eviction bans and mortgage forbearance) introduced at the onset of the pandemic are phased out. Recent data available for some countries suggest a drop or stabilisation in the tenant eviction rate in 2021 compared with pre-pandemic figures. For example, eviction orders carried out in Italy decreased from 32 546 in 2015 to 9 537 in 2021, while evictions dropped in the United Kingdom (England) from 41 453 to 9 471. Eviction bans and mortgage forbearance schemes were always conceived as temporary interventions to deal with more structural challenges, as they fail to address the root causes of housing cost vulnerability.

Figure 1.2. Pandemic-related temporary relief measures have been phased out across many OECD countries

Note: The “debt/contract relief” variable records if governments are freezing financial obligations for households (e.g., stopping loan repayments, preventing services like water from stopping) or banning evictions. The figure above displays the mean across all 38 OECD countries for data through 1 January 2023. For each country, coding is carried out in the following way: 0 no debt/contract relief; 1 narrow relief, specific to one kind of contract; 2 broad debt/contract relief.

Source: OECD calculations using data from Hale, T. et al. (2021), “A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker)”, Nature Human Behaviour, Vol. 5/4, pp. 529-538, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8.

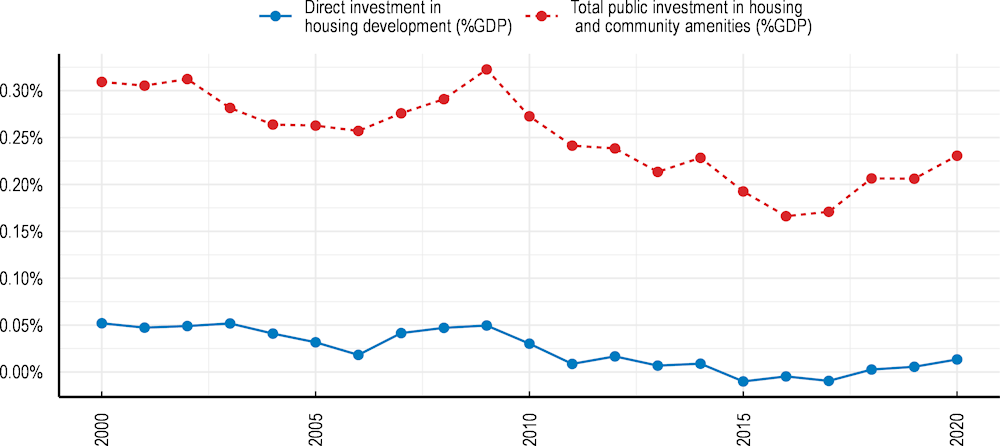

However, the current context is complicating a key structural response to make housing more affordable: the construction of new social and affordable housing development, which was already in short supply prior to the pandemic. Indeed, over the past two decades, public investment in housing has declined on average across OECD countries, and particularly since its peak in 2009 (Figure 1.3). Total public investment in housing and community amenities, a broad category that includes both public capital transfers and direct investment in many areas, including housing development, community development, water supply and street lighting, dropped by nearly 30% between 2009 and 2020. Total public investment in housing development alone was nearly cut in half between 2009 and 2020.

Box 1.1. Ending homelessness: Support to governments to improve measurement and policy responses

As temporary housing support measures introduced at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as eviction bans and rent freezes, are lifted in OECD countries (Figure 1.2), there is a risk of rising homelessness and housing precarity. While the pandemic first spurred rapid government responses to support people experiencing homelessness, their subsequent withdrawal, combined with the cost-of-living crisis, further strains many economically vulnerable households across the OECD.

Monitoring homelessness trends and implementing pro-active policies to prevent homelessness and help people experiencing homelessness to transition to stable housing should be a priority for policymakers in the OECD. Notwithstanding the challenges associated with data collection during the pandemic, homelessness remains hard to measure and compare across countries.2 Because there are many pathways into homelessness and people’s experiences with homelessness differ – from temporary or transitional periods without housing, to more chronic or repeated periods of homelessness – the policy responses to prevent homelessness and help people transition into stable housing must be tailored to individual needs, preferences and circumstances.3

Building on OECD data and analysis, the OECD is working to address the measurement gap and help governments develop effective solutions to end homelessness. Concretely, the OECD will develop i) a mapping of the existing evidence base, data collection methods on homelessness; ii) a monitoring framework to help governments better measure and monitor homelessness; and iii) a policy toolkit that provides guidance and good practice to combat homelessness and housing exclusion in OECD and EU countries.

Figure 1.3. Public investment in housing has dropped considerably since its peak in 2009

Note: Total public investment in housing and community amenities includes both direct investment and public capital transfers. Housing and community amenities includes housing development, water supply, street lighting, R&D in housing and the provision of community amenities. Housing development include the acquisition of land for the construction of new dwellings and the improvement or maintenance of the existing housing stock. OECD-30 average refers to the unweighted average across 30 OECD countries and excludes Canada, Colombia, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Türkiye and the United States.

Source: OECD calculations drawing on the OECD National Accounts Database (Government expenditure by function) doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/5b0629cc-en.

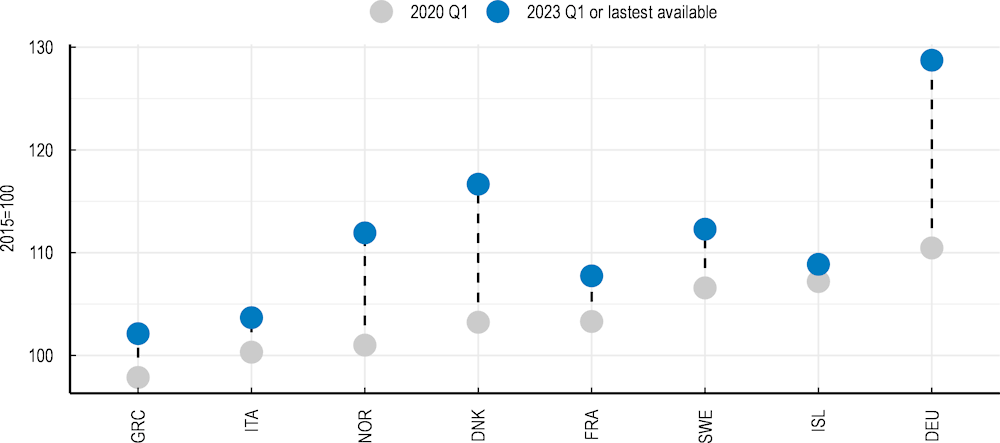

In the current context, increases in construction costs arising from more expensive raw materials, machinery and labour, and more demanding energy-efficiency standards (see Chapter 2), as well as rising interest rates (see below), are driving up development costs (Figure 1.4). As a result, many developments have been put on hold, especially in social and affordable housing, where developers are limited in their ability to raise rents to pass on higher costs to tenants. In Germany, municipalities and representatives of the construction sector predict that 70% of planned social and affordable housing projects are at risk. In the United Kingdom, planned affordable developments may not materialise or will deliver less than expected under England’s Affordable Homes Programme.4 More expensive development costs are also fuelling pressure on an already strained rental market, which could drive up rents for vulnerable tenants further. For instance, in the United Kingdom, in November 2022, private rental prices saw the largest annual percentage increase since records began in January 2016.5

Taking a long-term systemic approach to investing in affordable and social housing could help better manage some of these risks and put the sector on a more stable footing. A number of OECD countries have established revolving funds with the aim to create a long-term, sustainable mechanism to channel investment into affordable and social housing (Box 1.2).

Figure 1.4. Homebuilding costs have been rising much faster than inflation

Note: Real residential construction cost refers to the construction cost index for new residential buildings, in national currency deflated by the consumer price index.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators and OECD Analytical Database.

Box 1.2. Revolving funds to invest in affordable and social housing

To boost investment in housing, a number of OECD countries have established revolving funds, or more complex systems achieving the same effect, to finance the construction of affordable and social rental dwellings. These funds channel part of the rents or loan repayments into new affordable and social housing developments. The key features in establishing and operating a dedicated funding mechanism vary widely across countries, including with respect to the institutional set-up of the scheme, the funding and financing arrangements, and decisions around management and monitoring (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Framework for establishing and operating a revolving fund scheme to channel investment in affordable and social housing

|

Institutional set-up |

Funding and financing |

Management and monitoring |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Frame |

• Enabling legislation • National housing policy • Structure of the funding approach |

Investment environment: • Land-use regulations • Infrastructure • Size of existing rental market |

Management of the units: • Eligibility criteria • Allocation criteria • Rent-setting approach • Maintenance of units • Financing building improvements |

|

Scope |

• Scope of the housing activities financed • Geographic scope of the activities financed |

Funding sources: • Funding sources • Revolving fund mechanisms • Impact of funding scheme on public finances |

|

|

Tools |

• Actors and expertise involved in the funding approach |

Financing instruments: • Long-term loans • Incentives for affordable housing investments |

Management of the Fund: • Monitoring and control of the Fund • External auditing requirements • Tenant protections and complaints |

Institutional set-up

Institutional issues include decisions about the structure, function and scope of activities of the funding scheme, as well as the enabling legislation, policy environment and various actors involved in the scheme.

The structure of the funding scheme varies widely: for instance, such schemes may be established within a dedicated, stand-alone institution (such as Denmark’s National Building Fund) or via existing funding institutions to which additional resources are allocated (such as Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund); the fund may be a public or not-for-profit entity – or it may not be a formal entity at all (as in Austria and the Netherlands, where the entire system, led by housing associations, functions as a revolving fund scheme).

The scope of activities supported through the funding scheme may include new construction of rental and/or owner-occupied housing, renovations and/or demolitions of existing dwellings, and/or investments in broader infrastructure and neighbourhood improvements.

Relevant actors engaged in the scheme may include the central government, including ministries as well as other public agencies; sub-national actors (regions, municipalities, municipal housing companies); housing developers (including non-profit, limited-profit and co-operative housing developers); and commercial banks as well as international development banks.

Funding and financing

Financial matters include identifying potential funding sources at different stages, the different financing instruments, and the investment environment. Typically, such funds are established with initial equity (often but not always from public resources), often complemented by concessional or commercial loans and/or government guarantees. The funding schemes use a share of tenant rents (and, in the case of Austria, a share of the developers’ profits) to finance new construction, renovations and/or the purchase of existing dwellings.

Examples from OECD countries

OECD country experiences include:

Denmark’s National Building Fund: A dedicated, stand-alone, self-governing funding institution that was established by housing associations to promote the self-financing of construction, renovations, improvements and neighbourhood improvements. Funding is based on a share of tenants’ rents and contributions from housing associations to mortgage loans.

Austria’s affordable and social housing model: Austria’s funding approach relies on limited-profit housing associations that operate revolving funds under the supervision and with the steering of the federal, regional and municipal governments. Projects developed by limited-profit housing associations are typically financed by multiple sources, including tenant contributions, housing associations’ own equity, and public and commercial loans.

The Slovak Republic’s State Housing Development Fund: A fund established to finance the housing priorities of the government, the fund is an independent entity supervised by the Ministry of Transport and Construction. Originally financed exclusively from the State budget, the fund currently draws on a small amount of government funding and European structural funding, along with repayments on the loans it issues.

Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund: Latvia has established a new funding scheme to channel investment in affordable housing, with initial funding from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility, with the possibility for additional resources from State and commercial loans. In a first phase, the fund intends to finance the construction of new affordable rental housing outside the Riga capital area, which will be leased at below-market rents to households that meet income threshold requirements.

Slovenia’s Housing Fund: a dedicated fund for housing established to finance and implement the National Housing Programme. The Housing Fund is a public finance and real estate fund that provides long-term loans with a favourable interest rate to public and private entities to purchase, maintain and renovate non-profit rental housing or owner-occupied dwellings. The fund also invests in construction and land for development and supports the construction, refurbishment and renovation of housing for vulnerable groups.

The Netherlands’ affordable and social housing model: Housing associations have access to a guarantee fund (the Social Housing Guarantee Fund, or WSW). This system of housing associations operates as a sort of “revolving fund”, benefitting from lower interest rates thanks to the WSW and their mutual co-operation agreement to bail out housing associations. Furthermore, the Dutch State and municipalities act as guarantors of last resort for bank loans.

Source: (OECD, 2020[6]; OECD, 2023[7]; OECD, 2023[8]).

Face the energy crisis by laying the groundwork for low-carbon housing

Home energy costs have been highly volatile

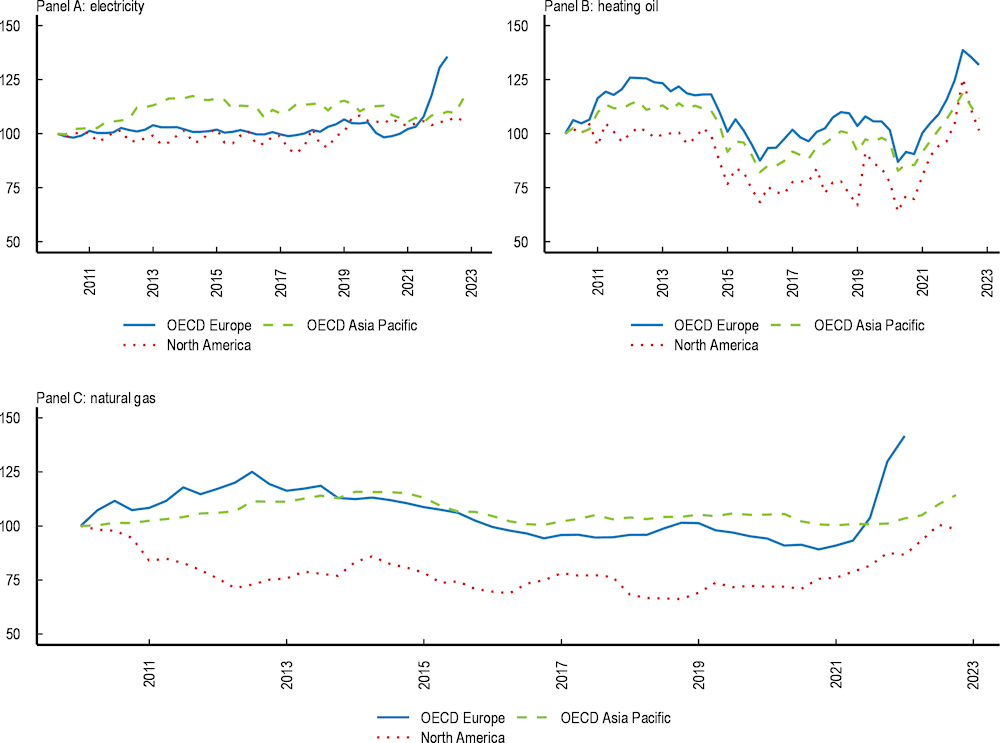

Household spending on energy has risen sharply as a result of the fossil fuel price shock triggered by the onset of the war in Ukraine (Figure 1.5). In some countries, droughts have put further upward pressure on electricity prices. Heating and hot water account for an average of 75% of home energy use across OECD countries (Chapter 2).

Figure 1.5. Home energy costs soared, especially in Europe

Note: Real retail energy price corresponds to the sub-indices for energy products of the CPI deflated by the CPI. OECD Asia + Oceania includes Japan, Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, North America includes Canada and the United States.

Source: IEA Energy Prices Database.

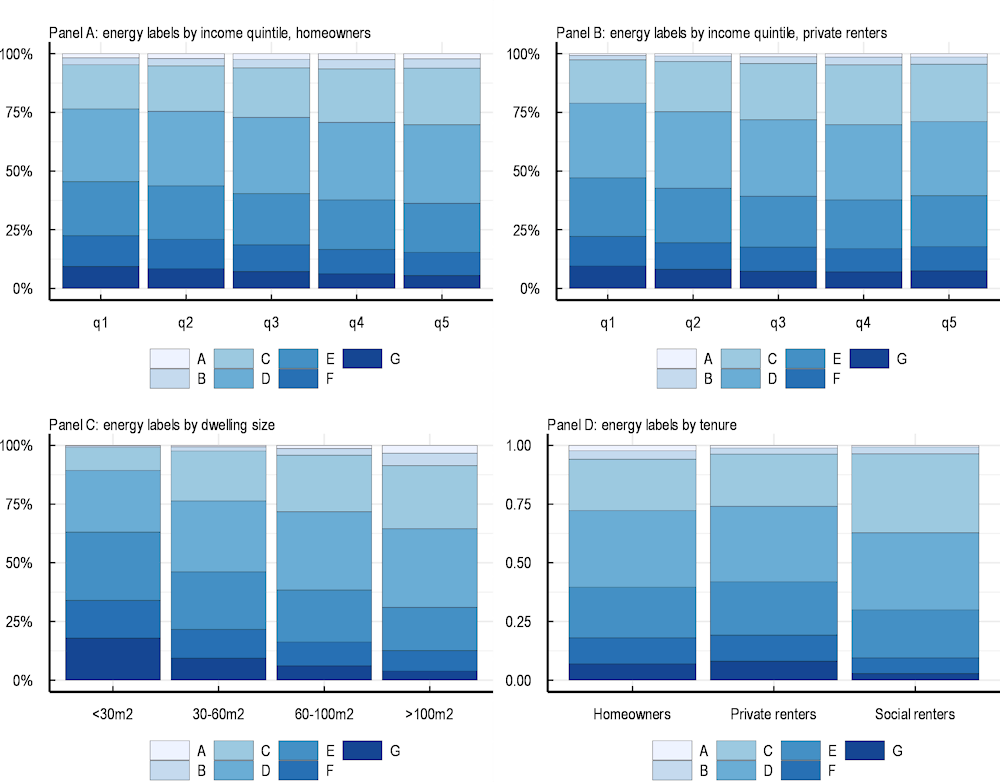

Energy price shocks pose particularly acute difficulties for low-income households and those living in poorly insulated homes. These characteristics often reinforce each other (Figure 1.6). Because households use energy at home to fulfil basic needs, they cannot respond to sharp price rises by quickly reducing consumption. As a result, low-income families spend a higher share of their income on energy (Figure 1.7), although the difference vis-à-vis higher-income groups is relatively modest in several countries.

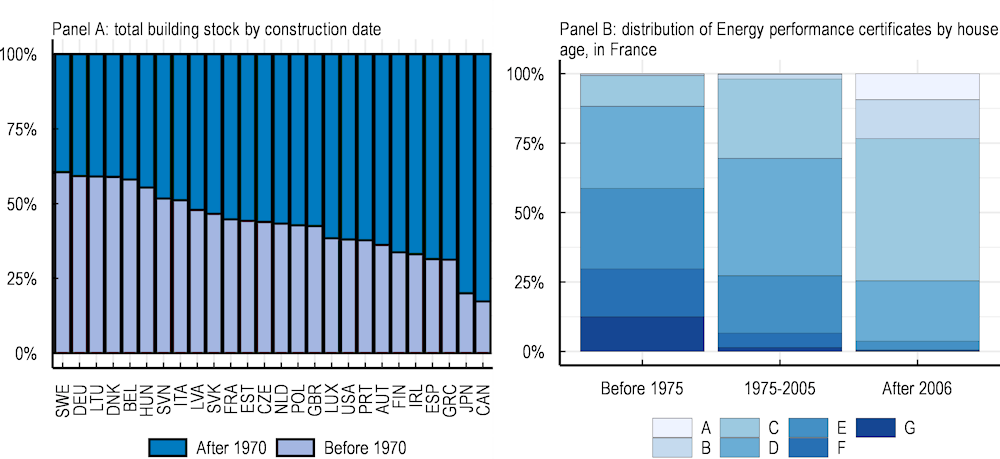

Figure 1.6. The energy performance of homes varies according to household income, dwelling size and tenure status

Note: The housing stock includes all primary residences on 1 January 2022 in metropolitan France. The energy certificate labels are estimated for the entire housing stock on the basis of 310 000 energy certificates collected by Ademe from December 2021 to March 2022 and tax data. Certificates classify energy efficiency from high (A) to very low (G).

Source: France’s National Observatory of Energy-Efficiency Retrofitting.

Figure 1.7. Home energy costs weigh particularly heavily on low-income households

Note: Top (bottom) income corresponds to the fifth (first) quintile of the income distribution in the Czech Republic, France, Japan, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States. In Germany and Spain top (bottom) income refers to monthly income higher than EUR 5 000 (below EUR 1 300 in Germany and below EUR 1 000 in Spain). In Denmark top (bottom) income refers to yearly income above DNK 1 000 000 (under 250 000 DKK).

Source: Causa, Soldani and Luu (2023[9]) and OECD calculations.

Decarbonising housing has become more urgent

The sharp rise in fossil fuel prices has brought to the fore the need to decarbonise the housing sector by enhancing the energy efficiency of buildings and promoting a shift towards greater use of green fuels for direct and indirect energy use. Better insulated homes with energy-efficient appliances reduce energy consumption and mitigate the impact of energy price spikes on household finances. Greening the sources of energy used in buildings further reduces the sector’s dependence on fossil fuels. Greater home energy efficiency and low-carbon energy sources would also reduce the need for short-term relief measures to lighten the burden on household budgets from fossil fuel price shocks (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Selected short-term energy cost relief measures, 2022-23

|

Country |

Name |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

France |

Energy check |

Supplementary “energy checks”, of EUR 100-200 have been paid to the 40% lowest-income households in 2022 in addition to the “energy checks” paid since 2008 to the poorest households. This measure complements the tariff shield applicable in 2022-2023, which caps retail electricity and gas prices. |

|

Germany |

Energy relief plan |

The plan aims to help ease the energy crisis for industries and households with EUR 200 billion of support. The fund, to last until 2024, is set to finance energy price caps and subsidies. Households will benefit from a price cap of 80% of their usual gas-consumption bill starting in March 2023 until the end of April 2024. They will pay EUR (0.12/check) per kilowatt hour for the first 80% of last year’s use of gas. |

|

Nether-lands |

Energy price cap |

From 1 January to 31 December 2023, the energy price of all small consumers of energy – households, self-employed people, small businesses and associations – is capped. Up to a consumption of 1 200 m³, the price of gas will be kept under EUR 1.45 per m³. Electricity will be available at EUR 0.40 per kWh for a maximum consumption of 2 900 kWh. In 2022, small consumers are receiving EUR 190 discounts on their energy bills of November and December. |

|

Spain |

Gas price cap |

The Spanish government capped wholesale gas prices to lower the electricity bill for households, since natural gas prices are the key driver of the electricity price on the Spanish power market. The average electricity price is expected to fall significantly to around EUR 130 per megawatt hour on average over 2023 from EUR 210 in the first quarter of 2022. |

|

United Kingdom |

Energy Price Guarantee |

This scheme aims to reduce the unit cost of electricity and gas so that a household with average energy use pays around GBP 2 500 a year for their energy use. The scheme entered into effect on 1 October 2022 to run at least until April 2023. As a result, an average household is estimated to save GPB 1 000 a year. Energy suppliers are fully compensated by the government for the savings delivered to households. |

Source: Decarbonising Homes In Cities in the Netherlands: a Neighbourhood Approach, OECD (2023[10])

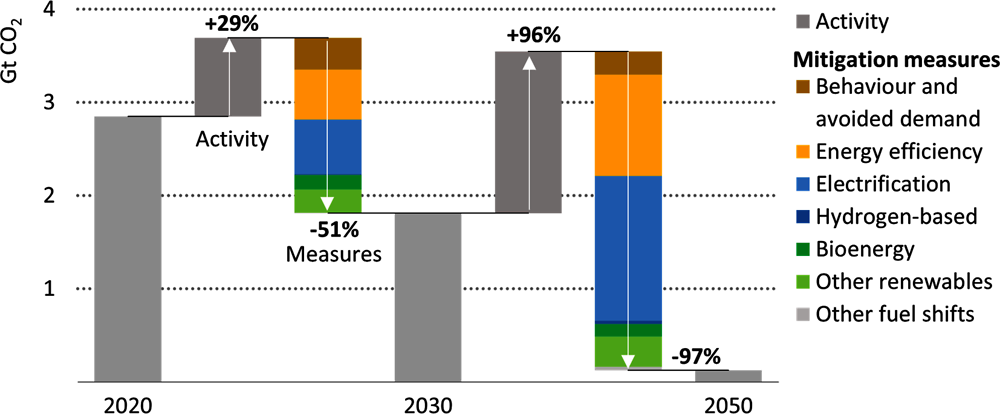

An array of tools is available to put housing-sector emissions on track to net zero

Together with greater energy efficiency, the other pillar of housing decarbonisation is the phasing out of fossil fuel use in homes coupled with the decarbonisation of electricity generation. Natural gas, fuel oil and coal boilers need to make way for electricity and, to a lesser extent, biomass (such as wood) and renewables (such as rooftop photovoltaic panels) (Figure 1.8). Electrification helps to decarbonise the housing sector to the extent that power generation shifts to carbon-free sources: in this respect, the reduction of housing-related emissions also depends on the success of efforts to decarbonise electricity generation.

Figure 1.8. Energy efficiency and electrification are the two main pillars of housing decarbonisation

Note: OECD or country breakdowns are unavailable for the IEA Net Zero scenario. Activity refers to demand created by rising population as well as increased per capita floor area and income. Behaviour refers to demand changes resulting from user decisions such as changing heating or cooling temperatures. Avoided demand refers to changes flowing from technology developments such as smart appliances.

Source: Net Zero by 2050 – A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, IEA (2020[11]).

Efforts to decarbonise housing would have the additional benefit of reducing vulnerabilities to fossil fuel price swings. Still, their primary purpose is to contribute to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 in line with agreed climate change targets. Housing is central to the success of climate change mitigation strategies, as the sector is responsible for more than a quarter of CO2 emitted on average in OECD countries. Over the past two decades, housing-related emissions declined by 17% on average across OECD countries, even though a much faster reduction, well beyond what the current announced policies are expected to achieve, is required to get to net zero emissions by 2050.

As detailed in Chapter 2, effective policy packages to decarbonise buildings need to price housing-related emissions while deploying additional measures that consider the sector’s specificities that make pricing alone insufficient. Pricing is a powerful tool to create incentives to avoid emissions in housing as in other sectors (D’Arcangelo et al., 2022[12]). Properly calibrated taxes on fossil fuels used in homes or emission trading offer an effective way of pricing residential emissions (Table 1.3).In countries where indirect taxes are already high, the pricing of fossil fuels used in homes need not imply additional taxes but may require a reorganisation of tax rates to better align them with emissions of CO2 and other pollutants.

The pricing of direct emissions from homes has to go hand-in-hand with the effective pricing of carbon emissions from power generation. This combination is important for three reasons: first, to create incentives to substitute electricity for fossil fuels in homes; second, to ensure that the power used in electrified homes comes from low-carbon sources; and third, to create appropriate incentives for energy saving and investment in energy retrofitting.

Carbon pricing needs to be complemented by additional policies. This is because of split incentives along the tenure spectrum. Importantly, landlords have weak incentives to invest in electrification and insulation if the resulting energy-bill savings accrue to tenants and if renovation costs cannot be passed on to tenants through higher rents. Tenants also have weak incentives to invest, because rental contracts are often too short for lower future energy bills to compensate for often onerous upfront investments. Indeed, the period before investments in home energy retrofitting break-even is usually long, especially for insulation (Chapter 2). Challenging coordination issues can also arise among homeowners in multi-apartment buildings. Such factors explain why the housing sector responds more weakly to changes in carbon pricing than other sectors, such as transport, industry or power generation.

Against this background, a variety of policy interventions can complement carbon pricing, ranging from environmental regulation through subsidies and financial support (Table 1.3). Regulation is well suited to phasing out fossil fuel boilers, mandating net-zero standards in new construction and rolling out energy-performance certification for buildings. It is particularly important to extend energy performance certification to all buildings, not only new ones, because new construction accounts for less than 1.5% of the building stock in OECD countries, making the energy renovation of existing homes a necessity (Figure 1.9). Tighter regulation in this area often triggers resistance, which can be overcome by a combination of mandates and financial support through subsidies (Chapter 2). The timeline for phasing-in net-zero-compatible requirements needs to take into account the pace at which the renovation sector can grow whilst acquiring the necessary competencies and the availability of the needed raw materials. Another consideration for the timing of energy retrofitting mandates is to avoid triggering a sharp depreciation of the value of housing assets that might create financial-stability risks.

Table 1.3. Main measures to decarbonise the housing sector

|

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Carbon pricing: |

Creates incentives for emission reductions Necessary for most other measures to be fully effective |

Insufficient on its own due to housing specificities such as landlord-tenant split incentives, frequent low awareness and lack of information about home energy efficiency and funding issues |

|

- Carbon tax |

Fairly straightforward to administer Provides revenue |

Exacerbates energy poverty especially in the short term Regressive along the income distribution before revenue use |

|

- Tradeable permits |

Easy to administer if traded upstream Provides revenue if auctioned |

Exacerbates energy poverty especially in the short term Regressive before revenue use Creates windfall gains if grandfathered |

|

Carbon regulation: |

Delivers carbon-efficiency gains directly |

Can see their direct effects partly offset by greater demand (“rebound effect”) |

|

- Ban on fossil fuel boilers |

Prompts electrification |

Requires decarbonisation of power generation Can be unpopular |

|

- Energy performance labelling mandates for buildings |

Guarantees awareness of energy performance |

Slow to take up if applied only at the time of transactions (sales or new leases) Unpopular if required outside transactions |

|

- Net-zero compatible building standards |

Ensure that new homes are compatible with net zero |

Entail some increase in building costs Insufficient on their own as the stock is only slowly renewed |

|

- Net-zero upgrade requirements on existing homes |

Provide very fast progress |

Very unpopular except if coupled with large subsidies Require a sufficiently developed energy renovation sector May involve high costs relative to decarbonisation options available in other sectors |

|

Subsidies: |

Help to fund options with long pay-off periods |

Can result in rebound effect unless backed by carbon pricing |

|

- For renovation or the deployment of existing technologies |

Help to overcome the up-front cost of renovations Receive strong support |

Can be very costly for the public purse Can be inefficient, if they involve a high cost per tonne of avoided CO2 emissions |

|

- For research and development |

Very useful especially on the basic research side of the R&D spectrum |

Require carbon pricing for technologies to become attractive on the market |

|

Property regulation: |

||

|

- Allow a split of the energy saving bill between landlords and tenants |

Reconciles the incentives of tenants and landlords towards energy-efficiency improvements |

Requires modifying rent-adjustment contracts, involving administrative complexity and potential opposition |

|

- Lower the bar for votes on energy renovation work in multi-family buildings |

Avoids stalemates that can prevent energy-efficiency improvements |

Possible opposition from liquidity-constrained owners |

|

Financial policy |

||

|

- Require that the green labels given to buildings and real estate-backed financial products are transparent and comparable |

Helps green real estate finance get scale Makes it possible for a renovation-funding market segment to develop Allows lenders to recognise the credit quality associated with high energy-efficiency homes |

None |

Note: The table summarises the main advantages and limitations of the measures. For more detail, see Chapter 2 for pricing, regulation and subsidies and Chapter 3 for financial policy.

Source: OECD.

Figure 1.9. A large share of the building stock is more than 50 years old in OECD countries

Notes: Panel A: Year of data collection: EU - 2014 (Austria - 2009), Canada - 2018, Japan - 2008, US - 2019.

Panel B: The housing stock includes all primary residences on 1 January 2022, metropolitan France. The energy certificate labels are estimated for the entire housing stock on the basis of 310 000 energy certificates collected by Ademe from December 2021 to March 2022 and tax data. Certificates classify energy efficiency from high (A) to very low (G).

Source: EU Buildings database, Canada National Energy Use database, NAHB 2021, and OECD calculations (Panel A); and France’s National Observatory of Energy-Efficiency Retrofitting (Panel B).

Financial markets can do a great deal to decarbonise housing

There is scope for making greater use of financial markets to accelerate the decarbonisation of housing. Financial intermediaries can play an important role and help smooth the costs of investment in the energy retrofitting of homes over often very long pay-off periods. However, financing for energy renovation is in short supply, especially by comparison with consumer loans or mortgages. Yet, empirical evidence suggests that investment in energy efficiency improvements tends to be capitalised in house prices and reduce homeowners’ future energy bills, bolstering borrowers’ loan repayment capacity, which should be reflected in lower borrowing costs.

A requirement for progress in this area is to instil greater transparency and comparability in the energy efficiency labelling of real-estate-backed financial products (Table 1.3 and Chapter 3). The fragmentation and opaqueness of this market prevent lenders and their funding markets from reflecting the lower risk attached to loans for the energy retrofitting of homes. Scaling up the market for green housing finance products requires reliable, internationally comparable energy performance certification of all buildings, not just those for sale or rent, with sufficient transparency of the related financial products, lending or investment vehicles.

Maintain resilience in the face of a turning housing cycle

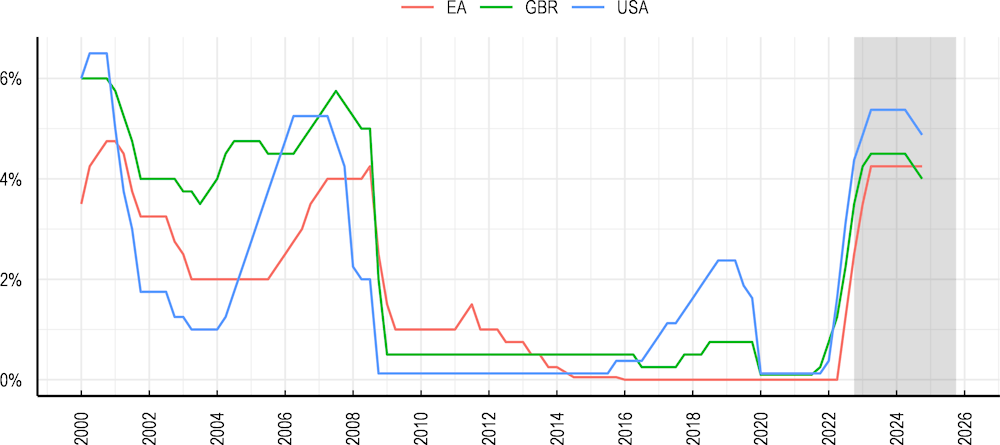

Conditions have changed in the housing market. For buyers, after a prolonged period of low interest rates, nominal interest rates have risen across OECD countries (Figure 1.10), as monetary authorities grapple with high inflation. Even if household incomes partly adjust to inflation, higher nominal interest rates reduce the mortgage servicing capacity of households for a given level of house prices. On the supply side, together with higher interest rates, sharp increases in raw material, machinery and labour costs are making development more expensive (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.10. Nominal interest rates have risen sharply

Note: The shaded area corresponds to projections.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, March 2023.

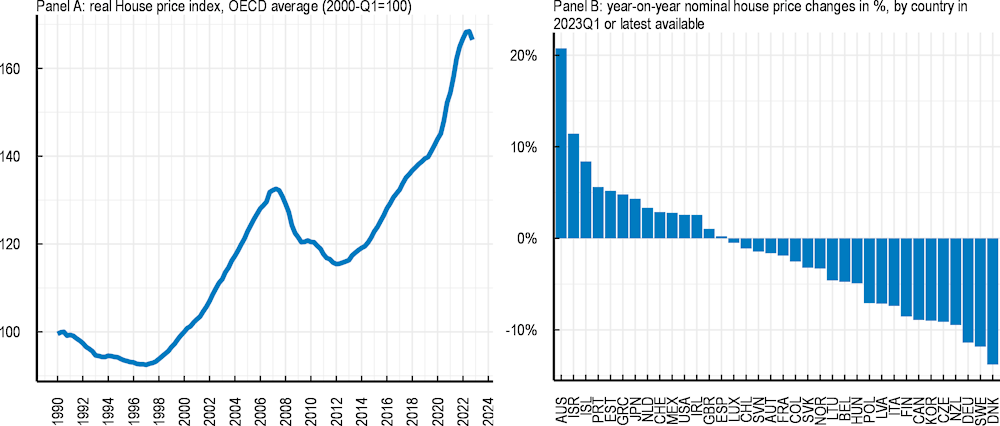

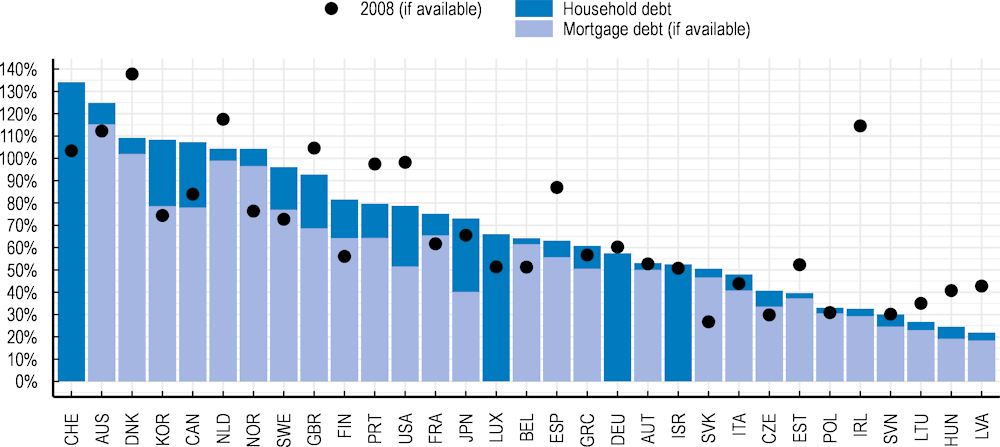

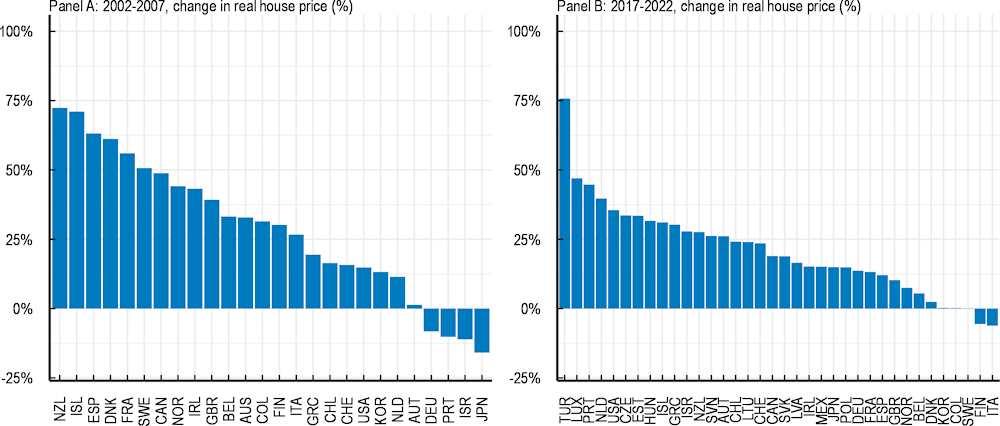

As a result of these developments, housing markets are facing a turn in the cycle in many countries. Real house prices, which stand at elevated levels after a long period of strong increases, have recently started to decline in a number of OECD countries (Figure 1.11). A turn in the housing cycle could potentially test financial stability by reducing the capacity of households and developers to service loans, threatening the value and credit quality of loans and other financial assets related to housing. In many OECD countries, mortgage debt stands at higher levels, even relative to income, than at the onset of the global financial crisis (Figure 1.13). In this environment, monetary and prudential authorities have been sharpening their focus on housing markets (Figure 1.12).

Figure 1.11. Real house prices are high but may have peaked in many countries

Note: Nominal house prices deflated by the private consumption deflator from the national account statistics.

Source: OECD Analytical House Price Indicators.

Figure 1.12. Central bankers are monitoring house prices with renewed attention

Note: The y axis shows the frequency at which “house price” or “house prices” appear in official speeches by central bankers.

Source: BIS repository of central banker speeches and OECD calculations.

Figure 1.13. Household debt has risen in many countries

Note: Data for 2020 for Austria, Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, France, Croatia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia and Slovakia. Data for 2019 for Greece.

Source: OECD Analytical Database.

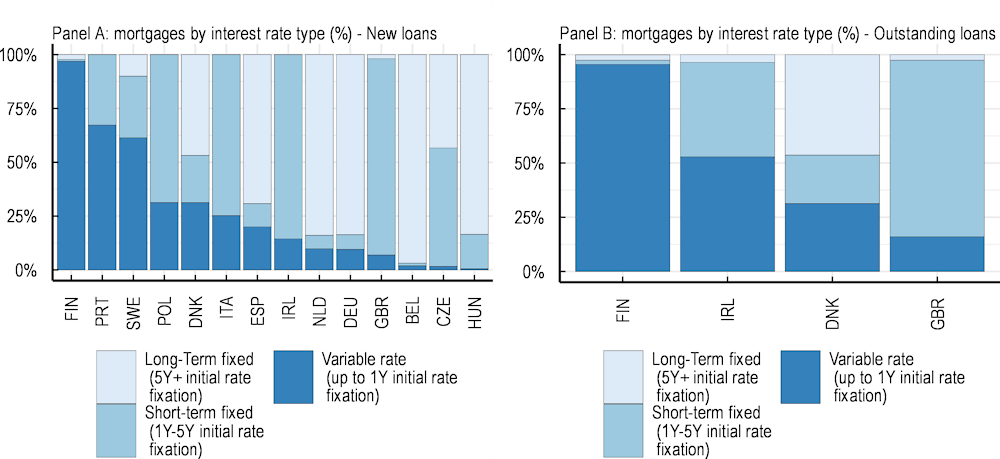

The transmission of tightening monetary conditions to housing borrowing costs is swifter where mortgages feature variable interest rates. Variable-rate mortgages represent the majority of existing and new loans in several OECD countries (Figure 1.14). The pressure associated with rising borrowing costs is particularly strong on low-income borrowers with adjustable-rate mortgages. In countries such as the United Kingdom and Sweden, the interest rates of the majority of outstanding mortgages are fixed during the first five years, and borrowers face the prospect of interest rates increases when they renew their mortgage. 6

As further developed in Chapter 3, OECD countries have deployed an array of macroprudential measures to safeguard financial stability in the face of housing market pressures. On the borrower side, many regulators have imposed limits on loan amounts relative to house values (loan-to-value, LTV caps), debt-service to income ratios (DSTIs), and/or debt amounts relative to income (DTI). As for lenders, regulators have, among other measures, been requiring banks to hold more equity capital against mortgages, build additional counter-cyclical capital buffers where necessary, and better consolidate their mortgage-related commitments to other market players on their balance sheets. Structural measures, such as personal income tax reforms that gradually withdraw mortgage interest relief for homeowners, also contribute to make housing finance more efficient and stable (Table 1.4).

Figure 1.14. A number of countries have a large share of variable-rate mortgage lending

Note: Data on adjustable-rate mortgages refer to the amount of gross lending. Data on new mortgages in Panel (A) refers to data from the second quarter of 2022. Data on outstanding mortgages in Panel (B) refers to the latest available data (second quarter of 2022), except for Ireland (first quarter of 2022).

Source: European Mortgage Federation.

Table 1.4. Selected policy tools for housing finance

|

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Gradually withdrawing mortgage interest relief for homeowners |

Avoids encouraging excessive mortgage debt build-up Reduces upward pressure on house prices Yields substantial tax revenue |

May narrow access to homeownership before prices adjust to the reform Increases the overall tax burden except if accompanied by other tax changes |

|

Macroprudential policy: |

||

|

Lending side |

||

|

- Capital requirements - Leverage caps |

Makes financial intermediaries more resilient to non-performing loan Reduces upward house price pressures |

May limit access to housing finance |

|

- Implement a risk-based approach to the regulation of non-bank mortgage lenders and services |

Reduces the risk of contagion from non-bank housing-finance market players |

May limit access to housing finance |

|

- Impose capital buffers and additional liquidity requirements on real-estate investment trusts and mutual funds |

Enhances capacity to absorb losses or funding shortages |

Could reduce funding channeled by real estate investment trusts and mutual funds |

|

- Adapt capital and liquidity surcharges to cyclical conditions |

Reduces financial amplification of housing-market swings |

May be difficult to calibrate in real time |

|

Borrowing side |

||

|

- Cap loans in relation to property value |

Limits excessive borrowing |

Makes housing finance sensitive to the housing price cycle |

|

- Cap debt service payments in relation to borrower’s income |

Reduces housing debt overhang |

Makes housing finance sensitive to interest rate changes |

|

- Cap housing debt in relation to borrower’s income |

Avoids excessive borrowing even in a low-interest environment |

Note: The table summarises the main advantages and limitations of the measures. For more detail, see Chapter 3.

Source: OECD.

The experience of OECD countries suggests that these measures are effective at improving financial and economic resilience.7 While substantial, the rise in real house prices prior to 2022 was not as strong as prior to the global financial crisis (Figure 1.15). Banks globally have ample liquidity, providing them with buffers against adverse scenarios.8 Many countries have counter-cyclical buffers in place (Chapter 3). This suggests that policymakers have the needed tools to address risks that may emerge from housing markets and prevent adverse feedback loops from house price reductions to financial markets more generally.

Figure 1.15. Real house prices rose strongly before 2022 but overall not as much as before 2007

Note: Real house prices are calculated as nominal indices deflated by the private consumption deflator.

Source: OECD Analytical Database.

The digital revolution has been a key driving force behind the rapid expansion of housing finance, some of which require particular regulatory vigilance in the current environment. Non-bank mortgage lenders and mortgage servicers, which have expanded considerably over the past decade (Chapter 3), need to be monitored to ensure that they do not provide undue levels of liquidity and maturity-transformation that could pose systemic risks. There is also a risk of spillovers if real estate mutual funds (REMFs), which face large outflows, respond by suspending redemptions. A central option to mitigate this risk would be to impose capital buffers and strengthen liquidity requirements.

Facilitate the reshaping of housing markets amid the rise of remote work and environmental concerns

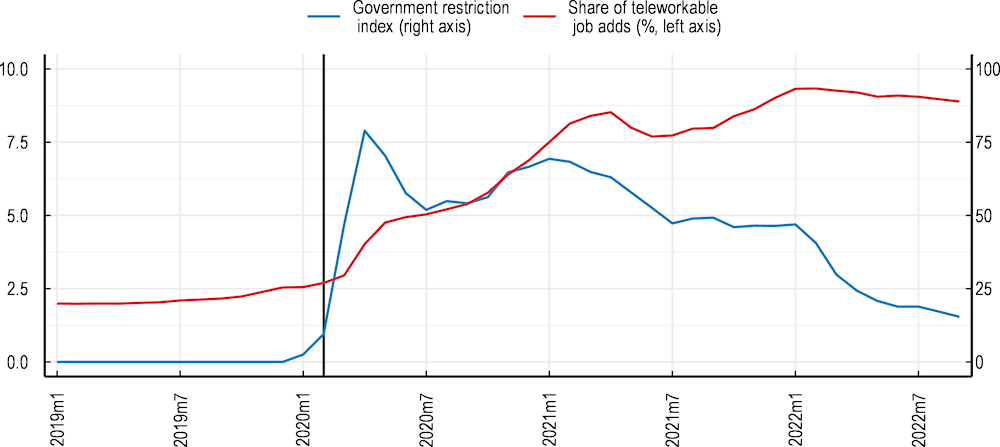

Digitalisation is reshaping housing location choices due to the increased uptake of remote work enabled by the spread of high-speed internet and advances in remote conferencing (OECD, 2021[13]). This trend was accelerated during the pandemic (Figure 1.16), and there are increasing signs that partial working from home is becoming the norm in many sectors. Surveys and job postings indeed indicate that remote work is set to remain much more prevalent than before the COVID-19 pandemic.9

Figure 1.16. Remote work is here to stay

Note: The stringency of restrictions is measured with the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (Hale et al., 2021[14]). Based on job data using proprietary information contained on the online job site “Indeed” for 20 countries, see the source for methodological detail.

Source: “Will it stay or will it go? Analysing developments in telework during COVID-19 using online job postings data” (Adrjan et al., 2021[15]).

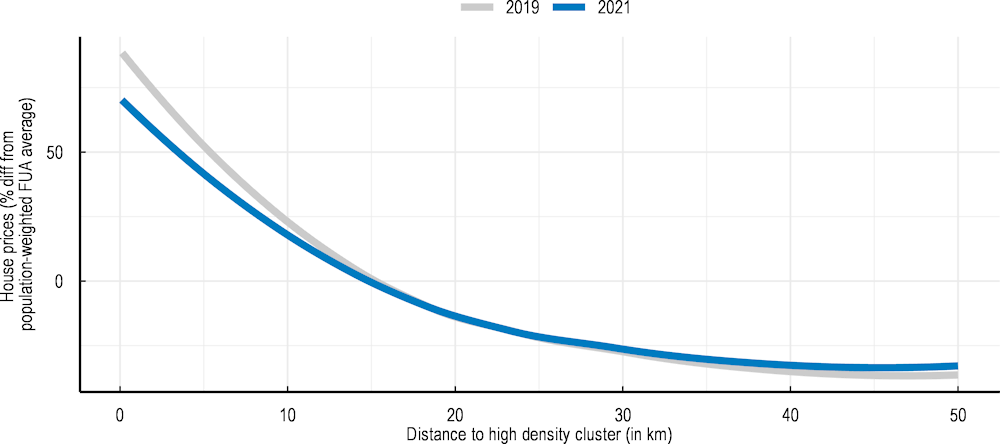

As a result of these forces, housing demand has been shifting, especially within large metropolitan areas (Figure 1.17). Accordingly, empirical evidence suggests a changing “house price gradient” with a shallower decline in house prices as the distance from urban centres increases (Figure 1.17). In other words, price differences between city centres and suburban areas have narrowed in many large urban areas since 2019, while they had been widening in the run-up to the pandemic (Chapter 4). This phenomenon is more prevalent where the take-up of remote work has been most pronounced.

Figure 1.17. House prices have risen faster around large cities than in their more expensive cores

Figure 1.18. Price pressures have typically been stronger in suburbs than city centres

Note: The graph shows the deviation of house prices from the Functional Urban Area’s (FUA) population-weighted average house price as a function of the distance to the respective urban centre, averaged across locations of monocentric cities with a population of more than 1.5 million.

Source: “Urban House Price Gradients in the Post-COVID-19 Era” (Ziemann et al., 2023[16]).

The new geography of housing demand poses challenges for policy (Table 1.5). First and foremost is the need to unlock supply where demand is growing fast to avoid price pressures that would further undermine affordability without prompting urban sprawl or exacerbating environmental challenges.10 This includes frequently revisiting urban boundaries, overcoming fragmentation across levels of government in the governance of land-use planning responsibilities and rethinking urban passenger transport systems. It is also vital that housing policies refrain from measures that discourage new supply, such as overly restrictive rental regulations. Shifting emphasis towards recurrent property taxes rather than transaction levies can facilitate residential mobility, ideally with split rate taxes where land is taxed higher than structures to favour compact development.

To reap the benefits of the working-from-home revolution and avoid the emergence of new inequalities, governments need to ensure widespread access to digital services. This starts with the provision of a secure and efficient digital infrastructure covering remote areas as well as dense urban areas. The development of digital government solutions can make access to public services more inclusive. Finally, it is vital to close the digital skill gap by providing tailored lifelong learning and training solutions to children, students, apprentices, parents and the elderly alike.

Table 1.5. Selected options to promote widely shared gains from the new geography of housing and better urban environmental amenities

|

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Make land-use regulations more flexible in accordance with urban strategies including by relaxing building height restrictions in high-environmental-quality areas and more generally allowing densification in areas where demand expands |

Unlocks supply; curbs house price growth Reduces the risks of urban sprawl and traffic congestion Broadens access to environmental amenities |

Vulnerable to political economy headwinds |

|

Make landlord-tenant regulations more balanced and flexible |

Facilitates residential and labour mobility |

May create vulnerabilities among current low-income tenants if insufficiently balanced |

|

Move towards recurrent property taxes rather than transaction taxes |

Facilitates residential and labour mobility |

May require compensatory measures to avoid hardship for “house-rich, income-poor” households |

|

Ensure widespread access to high-speed internet |

Enables remote work |

Can involve substantial budgetary costs especially in sparsely populated areas |

|

Ensure access to lifelong digital training |

Narrows digital divides |

Implies costs for employers and/or the government |

|

Systematically assess distributional consequences when designing environmental interventions |

Allows better incorporation of the objective of sharing the benefits of improvements |

Distributional effects may be difficult to estimate ex-ante and measure ex-post |

|

Supply social and affordable housing in areas benefitting most from improvements in environmental amenities |

Makes access to high environmental quality more inclusive |

Entails budgetary costs Vulnerable to political economy headwinds |

|

Deploy land-value capture mechanisms |

Mitigates distributional effects Facilitates investment in infrastructure and amenities |

May be legally and administratively complex |

Note: The table summarises the main advantages and limitations. For more detail, see Chapter 4.

Source: OECD.

Changes in housing demand also highlight the role of access to green spaces and environmental amenities, such as clean air and water, and lower noise levels in urban areas, and the possible distributive effects of urban environmental policies. Living in a place surrounded by a high-quality environment makes specific locations more attractive to residents, which is likely to push up house prices, undermining affordability for low or middle-income households. Consequently, environmental policies to improve urban amenities and reduce pollution can have negative distributional consequences (Chapter 4). Better provision of environmental amenities can price out low-income households: would-be renters and buyers face this effect immediately, whereas incumbent low-income renters may ultimately have to leave the area if rents become too expensive for them.

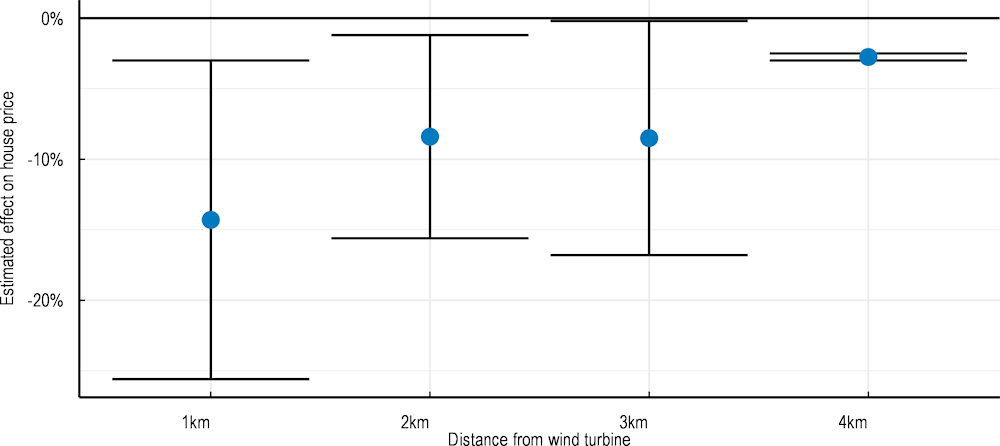

Complementary measures can mitigate these adverse side-effects to ensure that low-income households can afford to live in sought-after areas of high environmental quality (Table 1.5). Providing social and affordable housing in the areas benefiting most from better amenities is an important policy tool. Mechanisms to capture part of the value generated by environmental improvements offer a way to fund such provisions, even if there is limited precedent for their use (Chapter 4). Environmental policy can also have distributional consequences, as illustrated by the adverse house price effects of deploying wind turbines (Figure 1.19). These examples underscore the importance of reconciling environmental and social objectives, including through redistributive measures, to enhance the acceptability of decarbonisation policies.

Figure 1.19. Decarbonisation efforts can have adverse effects on house prices

Note: The intervals depict the range of estimates in the studies surveyed by the source. The points represent median estimates.

Source: “Provision of urban environmental amenities: A policy toolkit for inclusiveness”, (Farrow et al., 2022[17]).

References

[15] Adrjan, P. et al. (2021), “Will it stay or will it go? Analysing developments in telework during COVID-19 using online job postings data”, OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 30, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/aed3816e-en.

[23] Aksoy, C. et al. (2022), “Working from Home Around the World”, pp. 38-41.

[22] Barrero, J., N. Bloom and S. Davis (2021), Why Working from Home Will Stick, NBER, http://www.nber.org/papers/w28731.

[9] Causa, O., E. Soldani and N. Luu (2023), “A cost-of-living squeeze? Distributional implications of rising inflation”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper, forthcoming..

[12] D’Arcangelo, F. et al. (2022), “A framework to decarbonise the economy”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 31, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e4d973d-en.

[19] Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (2022), Scoping Report for the Evaluation of the Affordable Homes Programme 2021-2026, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1096533/Scoping_Report_for_the_Evaluation_of_the_Affordable_Homes_Programme_2021-26_FINAL.pdf.

[17] Farrow, K. et al. (2022), “Provision of urban environmental amenities: A policy toolkit for inclusiveness”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 204, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0866d566-en.

[14] Hale, T. et al. (2021), “A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker)”, Nature Human Behaviour, Vol. 5/4, pp. 529-538, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8.

[11] IEA (2020), “Net Zero by 2050 - A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector”, https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

[24] IMF (2022), “Global Financial Stability Report- Navigating the High Inflation Environment”, October, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2022/10/11/global-financial-stability-report-october-2022.

[5] Jarrett, P. (2021), “Improving the well-being of Canadians”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1669, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6ab6b718-en.

[8] OECD (2023), Affordable Housing Review of Lithuania, forthcoming.

[10] OECD (2023), “Decarbonising homes in cities in the Netherlands: A neighbourhood approach”, OECD Regional Development Papers, No. 42, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b94727de-en.

[7] OECD (2023), Road Map for a Revolving Fund Scheme in Latvia, forthcoming.

[4] OECD (2022), Affordable Housing Database - OECD, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

[21] OECD (2022), Coping with the cost of living crisis - Income support for working-age individuals and their families, http://OECD Policy Brief – COPING WITH THE COST OF LIVING CRISIS - Income support for working-age individuals and their families.

[3] OECD (2021), Brick by Brick: Building Better Housing Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b453b043-en.

[13] OECD (2021), “Teleworking in the COVID-19 pandemic: Trends and prospects”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/72a416b6-en.

[2] OECD (2020), Better data and policies to fight homelessness in the OECD. Policy Brief on Affordable Housing, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://oe.cd/homelessness-2020. (accessed on 16 March 2020).

[6] OECD (2020), Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Latvia, OECD Publishing.

[1] OECD (2015), Integrating Social Services for Vulnerable Groups - Bridging Sectors for Better Service Delivery., OECD Publishing, http://pac-apps.oecd.org/kappa/Publications/Description.asp?ProductId=341015 (accessed on 11 December 2017).

[18] Tagesschau (2022), Sozialer Wohnungsbau droht einzubrechen, https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/kommunen-sozialwohnungsbau-101.html (accessed on 6 December 2022).

[20] U.K Office for National Statistics (2023), https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/articles/howincreasesinhousingcostsimpacthouseholds/2023-01-09.

[16] Ziemann, V. et al. (2023), Urban House Price Gradients in the Post-COVID-19 Era, OECD Publishing, p. No. 1756.

Notes

← 1. See “Coping with the cost of living crisis - Income support for working-age individuals and their families”, (OECD, 2022[21]).

← 2. For more information on the methodological difficulties and available data, see (OECD, 2020[2]; OECD, 2021[3]; OECD, 2022[4]).

← 3. For a more detailed presentation of policy options, see (OECD, 2020[2]; OECD, 2015[1]).

← 4. Information on the German and UK examples come from (Tagesschau, 2022[18]) and (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022[19]).

← 6. UK Office for National Statistics (2023).

← 8. This assessment is taken from IMF (2022[24]).

← 10. This is one of the key themes in the original issue of Brick by Brick: Building Better Housing Policies (OECD, 2021[3]).