Financial markets and intermediaries are central to attaining public policy objectives in housing. This chapter documents the extent to which housing finance arrangements vary across OECD countries, with different implications, especially in terms of risk sharing between borrowers and lenders. It takes stock of trends in housing finance, especially the ascent of non-bank lenders. The chapter discusses policy options to create favourable conditions for housing finance markets that provide adequate funding, underpin efficient housing markets and contribute to the decarbonisation of homes.

Brick by Brick (Volume 2)

3. Gearing housing finance towards efficiency, resilience and decarbonisation

Abstract

Main policy lessons

Housing finance is one of the largest financial market segments. Well-functioning housing finance markets are essential to fund home buying and homebuilding as well as the large retrofitting expenses required to attain net-zero emissions. Another key policy objective is to ensure that the sector contributes to, rather than undermines, economic resilience in the face of shocks.

Policy options to improve housing finance include:

Policy should shift the focus away from promoting homeownership, which is often achieved through tax breaks for borrowers, and instead provide support, where appropriate, across the tenure spectrum. This would imply ensuring inclusive access to good-quality housing through a combination of well-functioning private rental markets, and adequate social and affordable housing.

To correct the bias towards homeownership, mortgage-interest deductibility should be gradually phased out, where it exists. Mortgage interest deductibility is both inefficient and inequitable, as it pushes up house prices. Other mortgage support measures, such as subsidised insurance or public guarantees, also have the undesirable effect of putting upward pressure on house prices and exacerbating default risk, with sizeable fiscal costs.

The revenue foregone due to tax breaks for borrowers could instead be used to finance meritorious programmes, such as the provision of social and affordable housing; and improve the public finances.

As regards financial resilience risks at a time of downward pressure on house prices, macroprudential policy should focus on avoiding adverse feedback loops triggered by asset repricing: key tools are capital requirements and leverage caps combined with close scrutiny of linkages between banks and leveraged holders of mortgage-backed securities.

The effectiveness of the regulatory tools for mortgage real estate investment trusts and real estate mutual funds should be further assessed. There is merit in implementing more comprehensive, risk-based approaches to regulating non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers. The objective is to address nascent vulnerabilities without undermining the benefits of market-based finance. Non-bank financial institutions should have adequate incentives to internalise their liquidity and maturity-transformation risks to avoid unnecessary cyclical spillovers to the rest of the financial system and the real economy.

There is a need to strengthen the resilience of real estate mutual funds to allow them to absorb outflows without resorting to redemption suspensions. These could include the imposition of capital buffers and additional liquidity requirements, adoption of swing pricing and use of liquidity management tools. The risks of mortgage real estate investment trusts are centred on maturity mismatch and debt rollover, and could be dealt with using risk management tools to strengthen their capacity to absorb losses and improve their liquidity positions.

Prudential regulations on non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers could be further improved, including by adopting a risk-based approach in line with the regulatory framework for banks. Also, it is important to adjust liquidity surcharges in light of market conditions to avoid a pro-cyclical stance that would force some lenders to raise funds at times of financial stress.

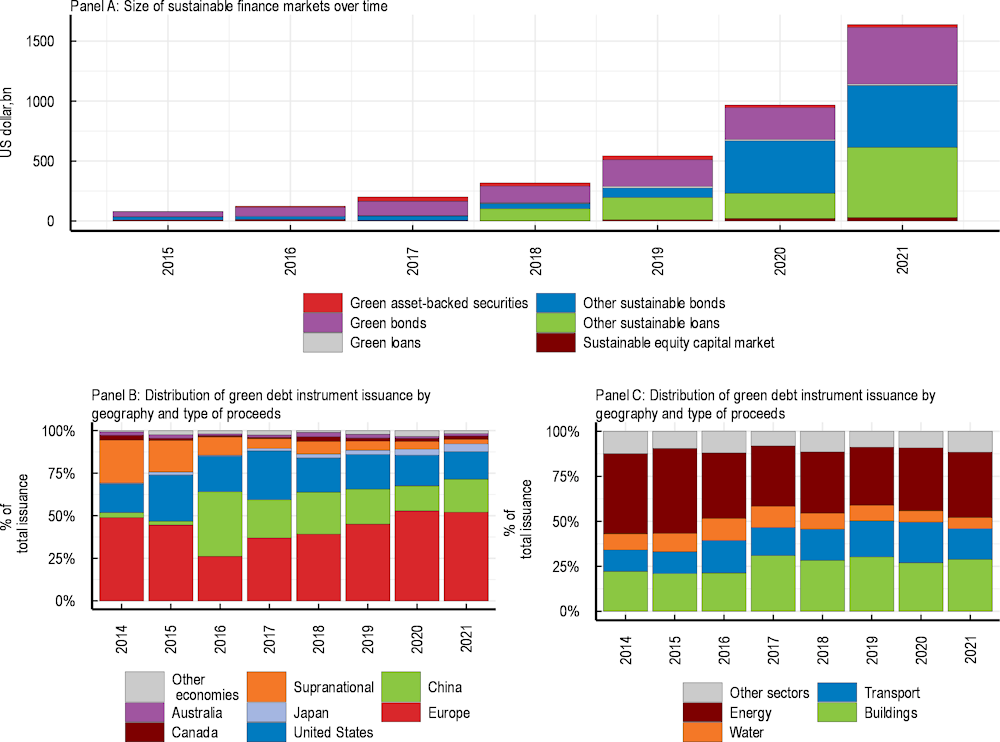

A central objective of green finance is to fund decarbonisation of the real estate sector. In that regard, policy needs to take a more active role in promoting transparency for the various green building rating systems to improve clarity and comparability to allow the various markets to merge and deepen across boundaries, thereby exploiting scale economies and overcoming the fragmentation that has slowed the low-carbon transition. Policymakers should likewise seek to strengthen green real estate bond and mortgage-loan frameworks. They should also support the development of green real estate finance instruments to underpin the expansion of green real estate finance markets needed to fund the transition to net zero carbon emissions.

Keep in mind country-specific features of mortgage markets

Housing-finance markets differ along many dimensions across OECD countries.1 Mortgage market depth, the characteristics of the products (e.g., years of amortisation, availability of foreign currency borrowing, fixed versus variable-rate lending), tax treatment, policies supporting mortgage take-up, the macroprudential framework and foreclosure rules all vary across economies. These features structure access to and affordability of owner-occupied housing. Yet, ownership is only one route to ensuring good housing outcomes: private rentals are an alternative option, and social and co-operative forms can also provide good-quality housing for lower-income segments of the population.

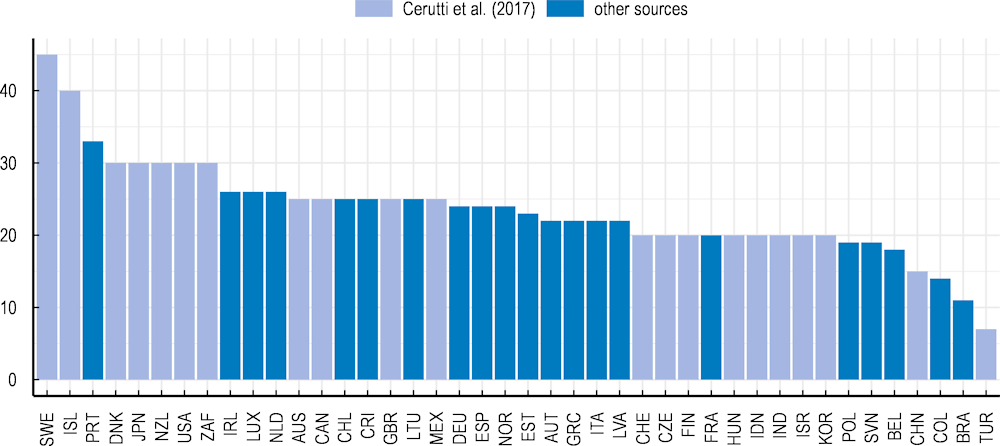

Homeownership and mortgage holding rates vary considerably across OECD countries

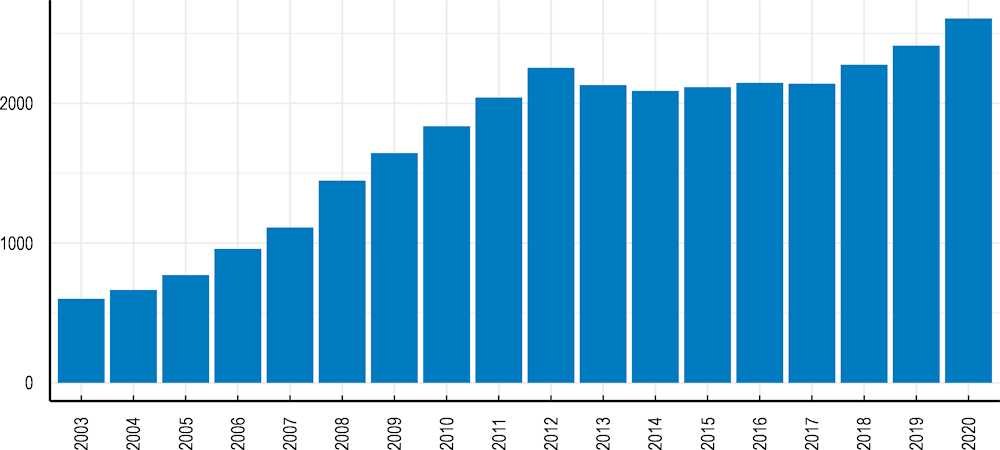

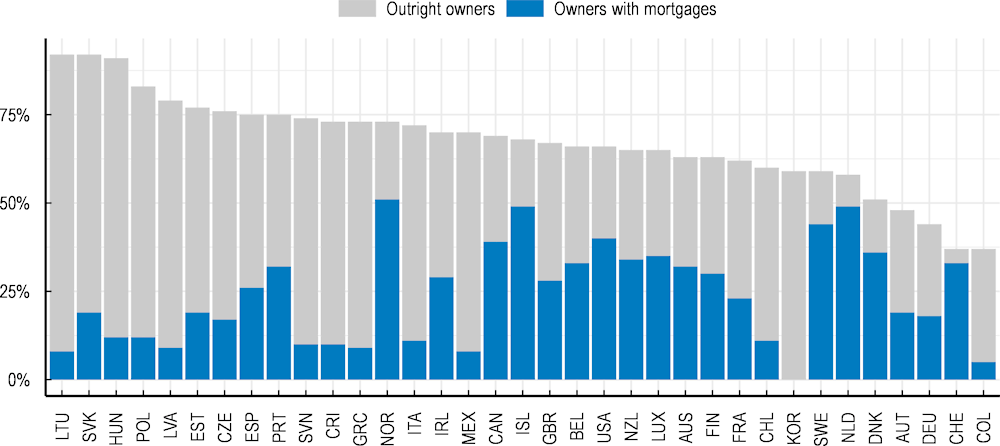

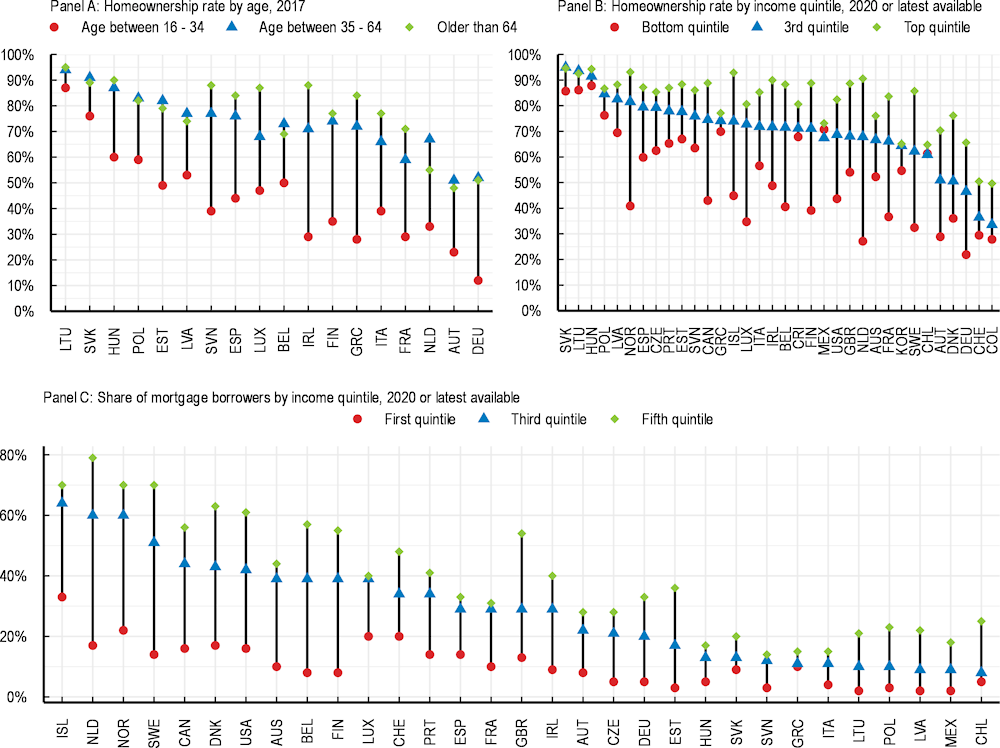

Homeownership rates vary considerably across OECD countries and social groups. Homeownership is particularly high in central and eastern European countries (Figure 3.1). Among owner-occupiers, those with a mortgage are fewer than one in ten in Colombia but about one in two in Norway, Iceland and the Netherlands. Moreover, homeownership is lower for younger households, even though age gaps in homeownership rates vary considerably across countries (Figure 3.2, Panel A). Furthermore, homeownership is correlated with income: income gaps in homeownership are particularly high in the Netherlands, Norway and France (Panel B). Similar income gaps are found in mortgage holding (Panel C). Mortgage costs also tend to be higher in relation to disposable income for low-income households (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.1. Homeownership rates vary considerably across OECD countries

Note:Data on the share of owners with mortgages is missing for Korea.

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database.

Figure 3.2. Homeownership and mortgage rates differ by age and income quintile

Source: ECB (2017), Household Finance and Consumption Survey; OECD Affordable Housing Database.

Figure 3.3. Mortgage costs burden low-income households more

Note: 2019 or latest available year. The average is calculated only across households with a mortgage. For the United States and Chile, gross household income is used due to data limitations.

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database.

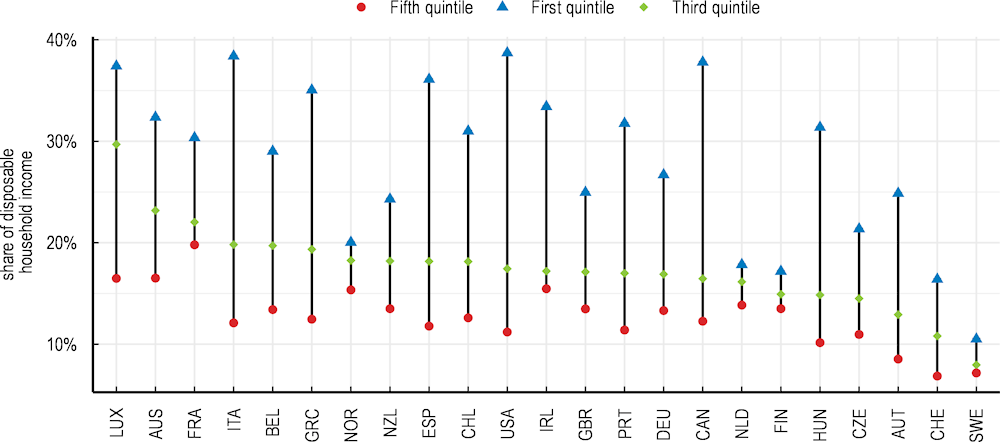

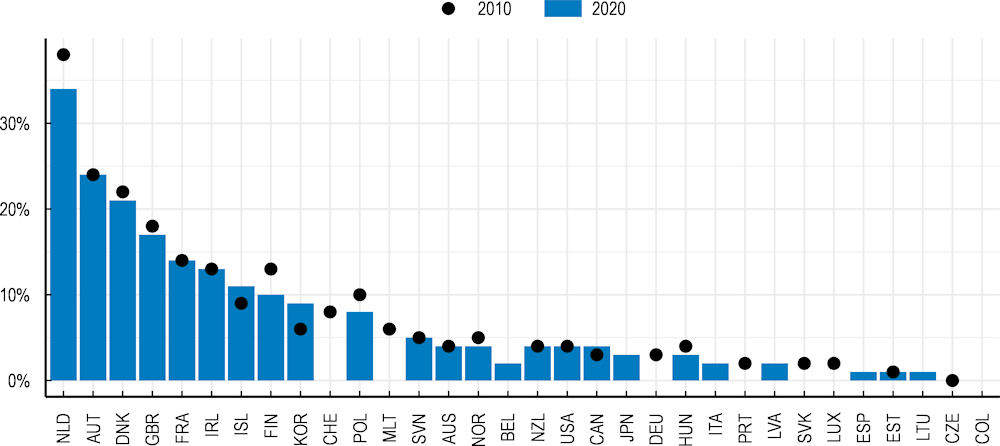

Mortgage markets also differ considerably across countries. The share of fixed-rate mortgages has increased substantially over the past decade, given the decline in interest rates in most countries, which makes floating-rate mortgages less attractive. Also the average maturity of new housing loans varies across countries (Figure 3.4), while the share of foreign-currency mortgage lending has shrunk.

Figure 3.4. The average maturity of mortgage loans varies considerably across countries

Note: Other sources refer to data from national sources from Van Hoenselaar et al. (2021[1]), when 2020 statistics from national sources are unavailable, the figure shows 2015 data from Cerutti, Dagher et Dell’Ariccia (2017[2]). The national sources give actual averages across loans at origination, while the data collected by Cerutti, Dagher et Dell’Ariccia (2017[2]) refer to the most typical maturity in the country.

Recognise the tension between supporting mortgage borrowing and promoting financial resilience

Many tax systems include mortgage interest tax deductibility and other support measures

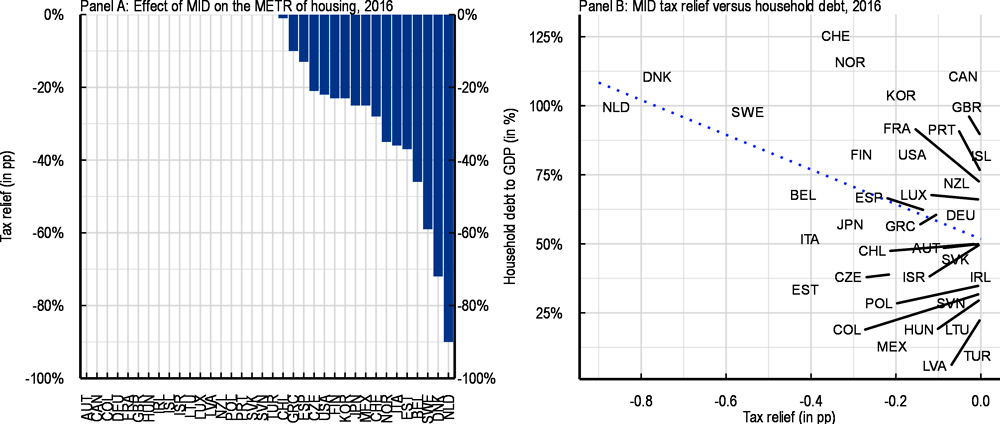

The tax system plays an important role in shaping housing demand (OECD, 2022[3]). The most important aspect is mortgage interest deductibility (MID). Mortgage interest on owner-occupied housing benefits from tax relief in 17 OECD countries via tax deductions or credits (Table 3.1). Marginal effective tax rates vary across countries and tend to be higher where household debt is high (Figure 3.5).

Table 3.1. Most countries support mortgage borrowers

National programmes1

|

|

Mortgage interest relief2 |

Mortgage guarantee schemes |

Subsidised mortgages |

Public mortgages |

|

Belgium |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Canada |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Chile |

X |

|

|

|

|

Costa Rica |

|

X |

|

|

|

Czech Republic |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

Denmark |

X |

|

|

|

|

Estonia |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Finland |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

France |

|

|

X |

|

|

Greece |

X |

|

|

|

|

Hungary |

|

|

X |

|

|

Ireland |

|

|

|

X |

|

Israel |

|

|

X |

|

|

Italy |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Japan |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Korea |

X |

|

|

|

|

Latvia |

|

X |

|

|

|

Lithuania |

|

|

X |

|

|

Luxembourg |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Mexico |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Netherlands |

X |

X |

|

|

|

New Zealand |

|

X |

|

|

|

Norway |

X |

|

|

X |

|

Russia |

|

|

X |

|

|

Spain |

X |

|

|

|

|

Sweden |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Switzerland |

X |

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom |

|

|

|

X |

|

United States |

X |

X |

X |

|

Notes: (1) Only programmes at the central-government level are reported. Many local and regional governments also have programmes.

(2) This relates to mortgage interest relief for owner-occupied housing.

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database.

Figure 3.5. Mortgage interest deductibility pushes up household debt

Various types of mortgage support to facilitate access to housing loans are available in OECD countries. For example, the US Federal Housing Administration offers insurance to about 20% of all owners up to a ceiling (Box 3.1), and various Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) are active in the secondary mortgage market (see below). The Korean Housing Finance Corporation plays a similar role. New Zealand has a guarantee scheme that allows higher loan-to-value (LTV) ratios than what would otherwise be provided by financial markets. Eleven other countries also operate various guarantee schemes. Tax-favoured saving plans for savings directed towards the purchase of a home are also fairly widespread. Finally, subsidised or publicly provided mortgages exist in 14 countries.

There is a case for reassessing mortgage support measures

Governments would do well to phase out mortgage-interest deductibility (MID), where it exists. To the extent that housing supply is imperfectly elastic, the tax break is at least partially capitalised in prices, which benefits existing homeowners, who are usually more affluent than potential buyers, while reducing borrowing costs. The additional tax revenue from removing or capping tax relief on homeownership could be used to lower other distortionary taxes or to improve after-tax income equality, depending on social choices. Other instruments, such as subsidised insurance or mortgage loan guarantees, are less distortionary, but they may exacerbate default risks with non-negligible fiscal costs (Box 3.1). Support may also be capitalised in higher property prices, which is undesirable.

Box 3.1. Public finance risks from mortgage loan guarantees: the US FHA and Canada’s CMHC

An important historical example of the materialisation of public finance risk is the 30 September 2013 budgetary transfer of USD 1.69 billion to recapitalise the US Federal Housing Administration (FHA).

This federal agency, established in 1934, insures mortgages for first-time and low-income buyers of single-family residences as well as the construction of affordable rental properties. It insured about 5% of all residential mortgages originated in 2006, a share that surged to about 40% in 2011 before falling back to 11.4% in 2019. Thanks to the unforeseen housing-market effects of the GFC the cumulative effects of its loan guarantees from 1992 to 2012 – a period during which the FHA insured USD 2.679 trillion in residential mortgages – fell short of predicted savings of USD 45 billion and became an estimated cost of USD 15 billion. According to the Congressional Budget Office, including the year 2013 as well, its cumulative loan guarantees would contribute only USD 3 billion to its capital reserves, USD 73 billion less than what would have resulted from the originally estimated subsidy rates.

Despite five increases in premium rates starting in 2009, tightened credit requirements and tougher enforcement actions, the General Accountability Office included the FHA as a high-risk entity in early 2013 because of its vulnerability to fraud, waste, abuse and mismanagement. With a negative net worth at the time of USD 16.3 billion and a capital ratio of -1.44% (compared to the legally mandated 2%, a level that it failed to reach each year from 2009 to 2014), along with the results of a Federal Reserve stress test that showed a potential need for USD 115 billion in extra funding in the event of a severe downturn, the FHA was forced to accept the “bailout”.

Another interesting case is that of Canada, where the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) is the federal government’s agency for its housing market interventions. It has never incurred a direct fiscal cost to taxpayers, though with almost CAD 401 billion in insurance in force and CAD 461 billion in guarantees in place (CAD 257 billion in Canada Mortgage Bonds and CAD 202 billion in MBS) and equity of only CAD 13.2 billion it is obviously highly leveraged. The federal government undertook a public consultation in 2017 ago to seek reactions to the idea of shifting more of the risks to mortgage originators by implementing a lender risk-sharing arrangement (Finance Canada, 2017[5]), but no major changes have been made since then.

For all these reasons, a case can be made to shift the focus of policy support away from promoting homeownership toward ensuring inclusive access to good-quality housing through a combination of social and affordable housing, private rental markets and well-functioning mortgage markets. The large amounts spent on tax breaks for mortgage borrowers provide opportunities for policy reforms that enhance financial stability, by reducing incentives to borrow, improve public finances and expand housing supply, through social and affordable housing construction. The capacity of private rental markets to provide affordable housing depends on the degree to which regulations allow homebuilding (Molloy, 2020[6]); without sufficiently flexible supply, there is a risk that financial investment into rental housing might contribute to high rent levels (Lima, 2020[7]).

Social housing provision is a powerful tool to improve affordability

Affordability is a challenge everywhere in the OECD with important implications not just for well-being but also for local economic dynamism and competitiveness. Low-income households have been under increasing financial pressure from rising housing costs, despite very low borrowing costs until recently. Housing poverty is measured by the “overburden rate”: the share of the population in the bottom quintile of the income distribution spending at least 40% of their disposable income on housing. It has afflicted one in four such households in the OECD on average. Overburden rates are lower among low-income renters, at about one-third among those in the private market and 10-15% for those in subsidised social housing.

Most OECD countries offer at least a certain amount of publicly-owned housing (Figure 3.6). However, at an average of about 7% of the dwelling stock, it is a smaller share than private rentals. The amount of government expenditure in support of rental social housing has generally been declining as a share of GDP (Adema, Plouin and Fluchtmann, 2020[8]).

Figure 3.6. The social rental dwelling stock is large in only a few countries

Source: OECD Affordable Housing Database (indicator PH4.2); Italy: Federcasa and the Tax Revenue Agency; Finland: national authorities.

Compared to ownership, renting has the advantage of encouraging greater labour mobility, which helps to deepen the labour market. However, that benefit is lost when it comes to subsidised (social) housing due to lock-in effects, unless coupled with portable eligibility. Housing allowances are an alternative policy option, but they are to some extent capitalised in rental prices. Affordability is also influenced by land-use regulations and planning (OECD, 2021[9]), to the extent that the relaxation of restrictions unlocks opportunities for housing developments more closely aligned with socio-economic and demographic trends (Phillips, 2020[10]).

Financial stability needs to be ensured against mortgage borrowing risks

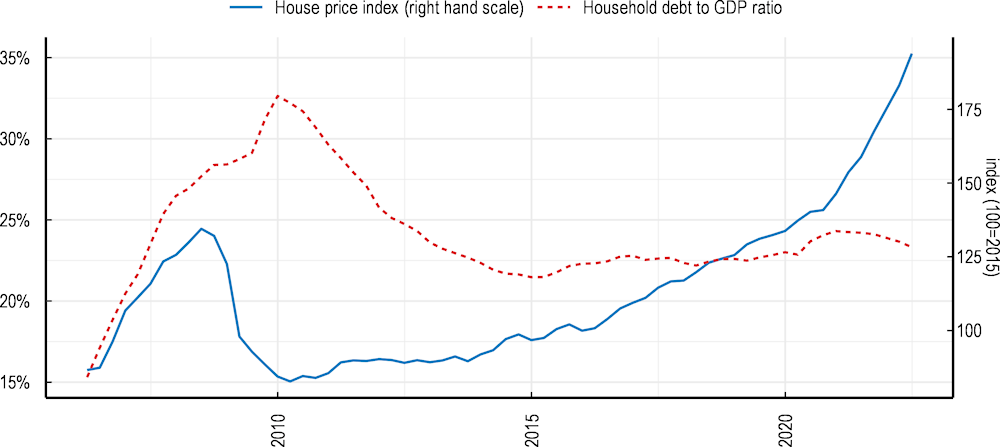

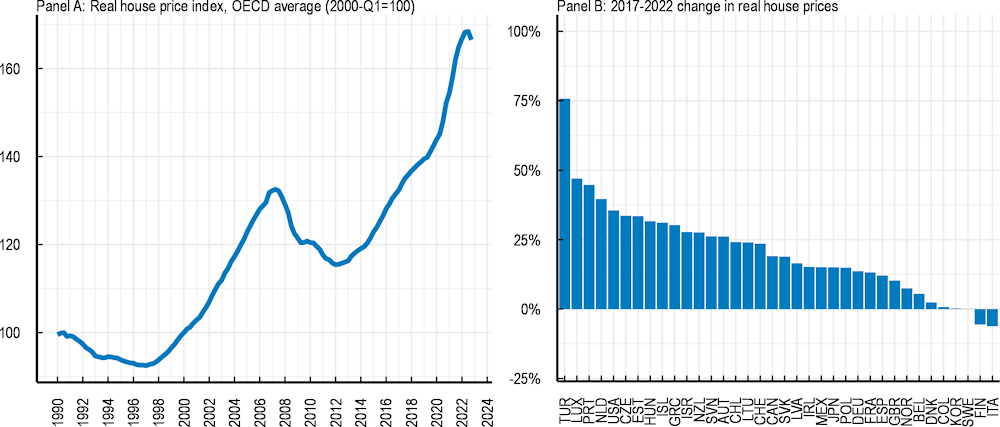

Housing provides key consumption services while being a long-term investment, a store of wealth and a collateral. Its financing is an important driver of business cycles. With interest rates rising after a long and rapid house price expansion (Figure 3.7), high levels of household debt and highly leveraged financial institutions, the macroeconomic role of housing finance may prove particularly significant. In the past, similar imbalances have affected the stability and resilience of financial markets and generated financial crises. The onset of the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 is a prime example of such consequences. Experience shows that the economic cost of such crises can be very large and recalls that public authorities need to provide a particular attention to the risks associated to this sector.

Figure 3.7. Real estate prices have risen rapidly

Note: Nominal house prices deflated using the private consumption deflator from the national account statistics.

Source: OECD Analytical House Price Indicators.

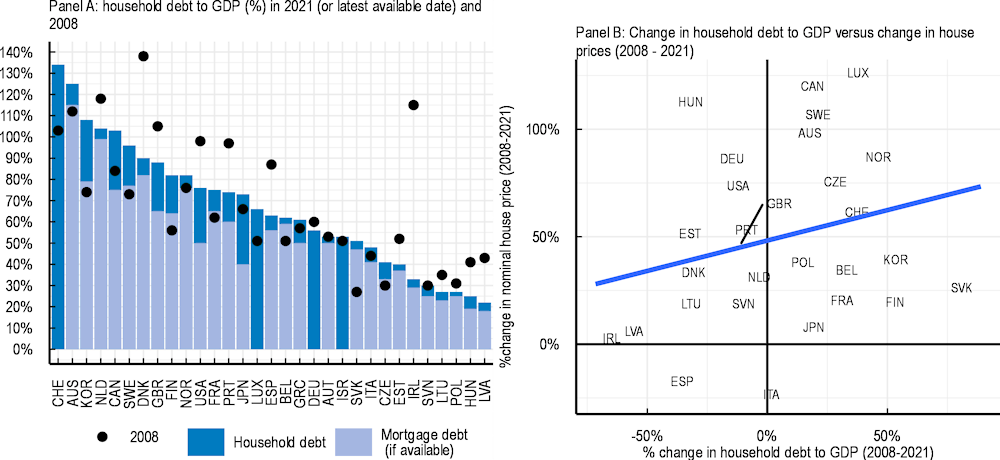

Measures to facilitate access to mortgage borrowing often come with adverse side-effects on house prices, and macroeconomic and financial stability, especially when they encourage excessive borrowing. Overall, household indebtedness varies substantially across OECD countries (Figure 3.8, Panel A) and is closely influenced by house price developments (Panel B). Many governments intervene in mortgage markets because of the associated financial risks, especially through macroprudential regulations (OECD (2021[9]) and Box 3.2 for the example of Italy). These can work on the side of borrowers, to keep indebtedness in check and reduce default risk, or lenders, to limit risk taking and excessive leverage.

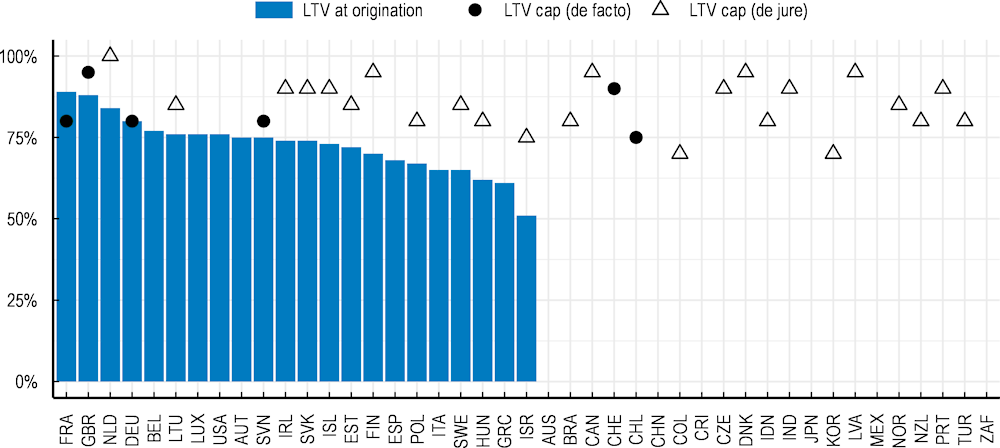

Borrower-side macroprudential policy

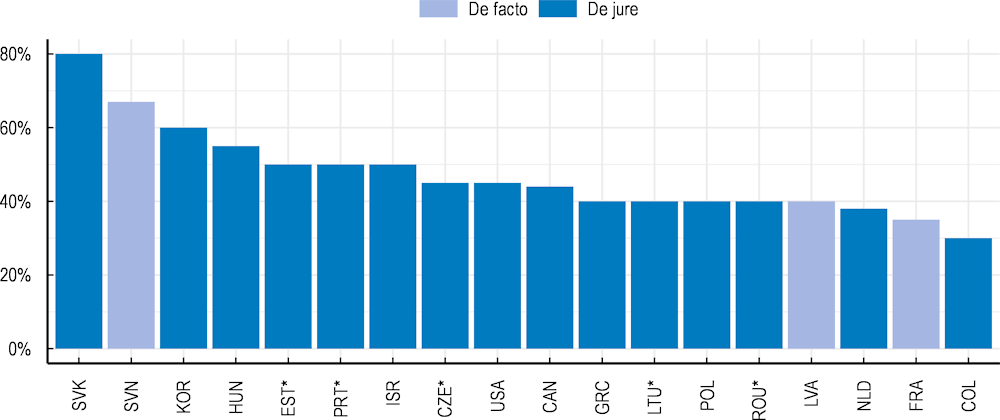

Prudential regulations in this area include caps on individual borrowers’ housing debt in relation to their income (DTI), debt service relative to income (DSTI) and the amount of borrowing relative to the value of the associated property (LTV). LTV ceilings at origination range from 50% in Israel to 95% in Finland, Canada, Denmark and Latvia (Figure 3.9). DSTI limits are in some cases only recommended, income definitions differ (i.e., gross versus net), and some countries allow a certain amount of lending to exceed the cap. They vary from 30% of income in Colombia to 80% in the Slovak Republic (Figure 3.10) and have empirically found to be more effective in curbing credit growth than those imposed on LTVs. DTI caps, which present the advantage of being insensitive to changes in interest rates or house prices, have so far been more rarely used (Van Hoenselaar et al., 2021[1]).

Box 3.2. Italy’s macroprudential framework

A regulatory framework for borrower-based instruments allows Italy to face systemic risks that could stem from the real estate market and the indebtedness of households or non-financial firms. The Bank of Italy can impose a number of restrictions on new loans, including limits on the LTV ratio, DTI, LTI, DSTI, leverage, maximum maturity and amortisation requirements of loans. The definition of measures is flexible, and limits can be applied: (a) on loans to households and firms; (b) with or without exemption thresholds; (c) in the same way on all loans or differentiated based on borrower and loan characteristics; (d) at the national level or for specific geographical areas; and (e) alone or in combination, with other measures.

In addition to banks, the Bank of Italy may apply borrower-based measures also to other financial intermediaries who, like banks, carry out the activity of granting loans in any form to the public. As of end 2022, the macroprudential authorities were not applying restrictive policy settings, as they assessed risks from the Italian residential real estate sector as low.

Source: Communication by the national authorities to the OECD.

Figure 3.8. Household debt levels and dynamics have differed across countries

Figure 3.9. Average loan-to-value at origination is typically well below loan-to-value caps

Note: De jure LTV-caps refer to official regulation of government institutions. The de facto caps are caps that follow from self-imposed constraints by financial institutions or recommendations from public authorities.

Source: ESRB (2021) Macroprudential database; OECD QUASH 2019 survey; IMF Macroprudential database; (ECB, 2020[11]); Bank of England.

Figure 3.10. Countries cap debt service relative to income at different levels

Note: The income used for the DSTI differs by country; some use gross income and some net income. In Estonia, Portugal, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Romania, a certain percentage of loans are extended above the DSTI cap. In the Czech Republic, a higher DSTI cap (50%) applies to borrowers aged under 36 years.For the United States the DSTI cap applies only for qualified mortgages that are eligible for purchase or guarantee by either Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.

Source: (ECB, 2020[11]); Bank of England; ESRB Macroprudential database; IMF Macroprudential database; OECD QUASH survey.

Lender-side macroprudential policy

Mortgage indebtedness also creates risks for lenders and holders of repackaged housing loans. While household balance sheets are currently stronger than before the global financial crisis, aggregate numbers might conceal important heterogeneity. Risks remain that the repayment capacity of low-income borrowers could deteriorate, given the withdrawal of pandemic income support measures, higher inflation and rising financing costs (OECD, 2022[12]). These developments may test the adequacy of the macroprudential tools to counter mortgage default, such as DSTI or LTV caps, deployed at the time when housing markets expanded rapidly. Therefore, trends in new defaults should be carefully monitored as deteriorating credit quality of households could lead to substantial losses for mortgage lenders and holders of mortgage-backed securities, with negative impacts on the resilience of the financial system.

Higher interest rates in response to higher inflation reduce the value of mortgages and their derived securities on the balance sheets of financial institutions, making asset valuation a major risk for macroprudential policy to manage. Tools directly focussing on the health of financial institutions, such as risk-weighted capital requirements and non-risk-weighted leverage caps, are well suited to tackle the risk of adverse feedback loops that could be triggered by asset revaluation. They need to be combined with close scrutiny of linkages between banks and leveraged holders of mortgage-backed securities. As well, the risks associated with variable-rate and foreign-currency mortgage loans need to be appropriately accounted for.

Tailoring macroprudential policy to economic circumstances

The steering of macroprudential policy, which can build on a wide body of accumulated international experience (Box 3.3), needs to consider higher inflation and rising interest rates. Regulatory caps on DSTI ratios need to be forward-looking, incorporating the likelihood of higher interest-rate payments for variable-rate loans as interest rates increase. In an environment of rising inflation and interest rates, fixed-rate mortgage lending involves risks to financial stability through channels that differ from the recent low-inflation, low-interest-rate period. In as much as wages, capital income and disposable household income at least partly follow inflation, servicing fixed-rate loans should become easier for households over time, even if the squeeze from higher energy and food prices may temporarily complicate mortgage servicing and ultimately such loans will have to be rolled over at higher borrowing rates.

Box 3.3. Conducting macroprudential housing policies: the experiences of three countries

Lithuania

In Lithuania, the global financial crisis underlined the importance of macroprudential policy implementation to ensure sound financing of the housing sector and mitigate credit-fueled unsustainable housing price dynamics.

The Lithuanian housing market experienced a substantial boom-and-bust cycle over the period 2006-2009 amid easy lending conditions and an underestimation of credit risk. To encourage more responsible lending practices and to strengthen market discipline in the aftermath of the housing crisis, in 2011, the Bank of Lithuania issued a set of Responsible Lending Regulations. These regulations implemented a mix of borrower-based measures (BBMs) applying LTV, DSTI and maturity limits on newly issued housing loans. As the mortgage market remained depressed and lending standards set by credit institutions were extremely strict at that time, it allowed for a non-binding calibration of BBM limits with the aim of preventing a subsequent build-up of vulnerabilities.

The BBMs were successful in ensuring responsible lending practices, as after 2011 the share of loans with high LTV and DSTI at origination remained low and household debt declined to well below pre-crisis levels, despite the significant recovery in the mortgage market since 2016 (Figure 3.11). In contrast to the 2006-2008 episode, the increase in house prices during the post-pandemic period has been fuelled by different factors including a sharp rise in construction costs, high consumer confidence and a significant increase in housing demand (Karmelavičius, Mikaliūnaitė-Jouvanceau and Petrokaitė, 2022[13]).

Figure 3.11. Lithuanian house prices have been rising while indebtedness has remained stable

The prolonged environment of low interest rates implied that DSTI limits became less binding. Lower interest rates allow borrowers to take on more debt without breaching the DSTI threshold. To safeguard borrowers from excessive borrowing when interest rates are low and to ensure their ability to service their loans under higher interest rates, the 40% DSTI requirement was supplemented in 2015 with the obligation to ensure that DSTI would not exceed 50% if calculated using a 5% interest rate. The implementation of this requirement indirectly implied a maximum debt-to income ratio of 7.8 and therefore reduced the effective DSTI limit to 35% for those close to the DTI limit. As of 2022, loans issued adhering to this requirement constitute 70% of the mortgage loan portfolio, a situation that contributes to resilience to increasing interest rates.

In 2017, with the transposition of the EU Mortgage Credit Directive into Lithuanian legislation, the scope of the Responsible Lending Regulations was expanded to ensure that BBMs would be applicable to all credit providers issuing housing loans in Lithuania. Such an activity-based application of BBMs treats all credit providers equally, reducing opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.

The increase in second and subsequent housing loans raised concerns regarding their impact on financial stability. Their share rose from 10% to 13% of new housing loans between 2019 and 2021 (Bank of Lithuania, 2022[14]). To reduce risks from such loans and discourage households from taking mortgages for housing other than their primary residence, the LTV requirement for second and subsequent housing loans was tightened from 85% to 70% as of 1 February 2022.

Growing risk in residential real estate markets also called for action to improve the resilience of credit providers. To enhance their capacity to absorb losses in the event of a housing market correction and resulting inability of households to meet their obligations, a 2% systemic risk buffer became applicable on 1 July 2022 for domestic exposures to household debt secured by a residential property.

In Lithuania a significant share of housing transactions is financed by own funds: 50% of total acquisition costs on average over the period 2015-2021. Therefore, macroprudential policy measures can affect only a fraction of the housing market transactions, and additional policy measures with a broader reach, such as an immovable property tax, are needed. Currently only households whose real estate worth exceeds a relatively high threshold are subject to the immovable property tax. Such tax design does not sufficiently address housing market stability goals and could be adjusted imposing a recurring tax on a broader range of taxpayers while maintaining overall tax system progressivity (Bank of Lithuania, 2022[15]).

The Lithuanian housing market is affected by a wide range of factors, including by the stance of monetary policy. Challenges are best addressed by combining several macroprudential and tax policy tools with effective land-use planning and social housing development to ensure a flexible housing supply.

Norway

High household debt and house prices are important vulnerabilities in the Norwegian financial system. Since 2010, Norway has implemented a number of macroprudential measures to promote a more sustainable development in household debt and to address risks related to household indebtedness and other vulnerabilities.

Borrower-based measures

Borrower-based measures were first introduced in the form of non-binding guidelines on mortgages from the Financial Supervisory Authority in 2010. The guidelines were replaced by a mortgage regulation laid down by the Ministry of Finance in 2015. In 2019, the regulation was broadened to include consumer loans. The measure is evaluated regularly, and subject to public consultation.

The current regulation is set to expire at the end of 2024. The regulation caps the loan-to-value ratio (LTV) of new mortgages at 85%, and the debt-to-income (DTI) ratio at 500%. Furthermore, it requires the lender to assess the borrower’s debt-serving ability, allowing for an interest rate increase of 3 percentage points or an interest rate of at least 7 per cent. To ensure that banks can make customer-specific assessments, a share of banks’ loans can exceed the regulation’s requirements.

Since the measure was introduced, fewer mortgages with a very high LTV and DTI ratios have been granted. However, the average DTI ratio has increased, and an increasing number of mortgages have been granted to borrowers with a DTI ratio close to 500%.

Capital requirements

Developments in residential and commercial property prices are important indicators for the assessment of cyclical vulnerabilities. Both indicators often rose substantially ahead of financial instability episodes. The counter-cyclical capital buffer requirement, which is intended to strengthen banks’ ability to absorb loan losses, was decreased during the pandemic. Since then, it has been increased several times, and is set to increase to 2.5% as of March 2023. The central bank has the decision authority over the countercyclical buffer.

A systemic risk buffer for banks was implemented in Norway in 2013, and set at 3%. In 2020, the buffer was increased from 3 to 4.5 per cent and targeted towards domestic exposures. The systemic risk buffer is in large part calibrated based on structural vulnerabilities stemming from high household debt and substantial exposure towards commercial real estate among Norwegian banks.

To prevent large banks from using the Internal Ratings Based (IRB) approach to assign unjustifiably low risk weights on Norwegian residential and commercial real estate exposures, the Ministry of Finance adopted from year-end 2020 temporary floors for average risk weights for such exposures at 20 and 35 per cent, respectively. The floors are reviewed biennially, and were extended for two more years from year-end 2022.

Switzerland

To reduce risks in the Swiss mortgage and real estate markets, a series of measures were taken between 2012 and 2022. These measures include stricter capital requirements for high-LTV mortgage loans, several revisions to the self-regulation rules and the use of the sectoral counter-cyclical capital buffer.

Self-regulation rules were tightened in 2012, 2014 and 2020. The revisions restricted the use of pension savings as down payment or as collateral for borrowers (10% own equity, not taking into account any pension assets, was required in 2012 and 2014; and 25% for investment properties in 2020). Moreover, they stipulated that mortgages must be paid down to two thirds of the collateral value within a maximum amortisation period (20 years in 2012, 15 years in 2014).

The sectoral counter-cyclical buffer was activated and set at 1% of risk-weighted mortgage positions financing residential real estate located in Switzerland in early 2013. In 2014, it was increased to 2%. After the onset of COVID-19, the sectoral countercyclical buffer was deactivated in March 2020 to cushion the economic impact of the pandemic and give banks – together with other measures – more latitude for lending. The sectoral counter-cyclical buffer was reactivated in January 2022 (at 2.5%) in light of the persistent risks facing Swiss mortgage and real estate markets.

Overall, the combination of supply and demand-side measures coupled with repeated public warnings by authorities seems to have had an important impact on housing-related risks. In particular, the sectoral counter-cyclical buffer has contributed to the resilience of the banking system. Moreover, tightened down-payment requirements appear to have had an impact on the dynamics of the mortgage and residential real estate markets.

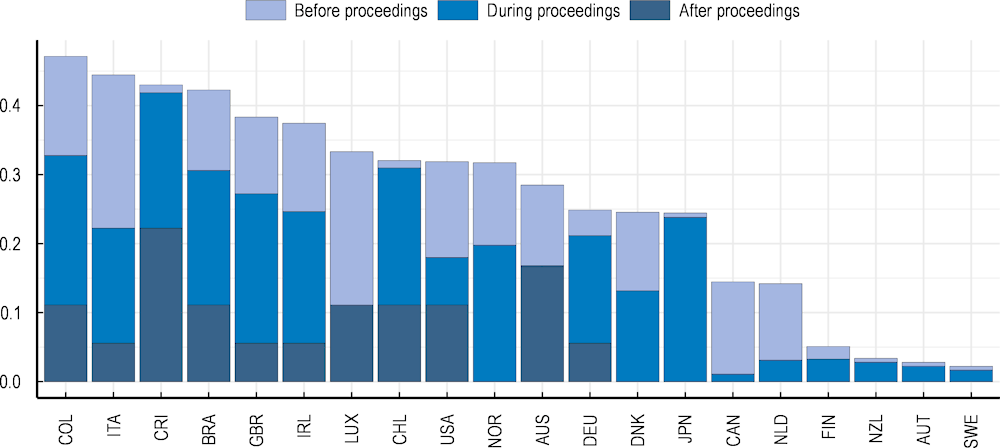

Legal systems need to balance the rights of borrowers and lenders in foreclosure proceedings

Foreclosure procedures vary considerably across OECD countries. The balance between the protection of borrower and lender rights determines how the default burden is shared between households and the loan-issuing institution. The OECD has recently developed a Foreclosure Regulation Index, which measures the balance between the protection of lenders and borrowers based on eight features of mortgage regulation (Van Hoenselaar et al., 2021[1]). The results for 20 OECD and partner countries show that Colombia and Italy have the most borrower-friendly regulations, whereas Sweden and Austria are the most lender-friendly jurisdictions (Figure 3.12).

In some countries foreclosure can begin immediately after the first missed payment, but in others the delay can run well above a year. The process takes anywhere from a few weeks in Austria and Luxembourg to an average of 120 weeks in Italy. This increases the risk facing lenders, as the quality of the underlying collateral might deteriorate in the interim.

Out-of-court procedures are available in about half of the countries considered. If in- and out-of-court procedures both co-exist, the latter are generally most used because they are faster and less costly. Specialised bankruptcy courts exist in only five of the countries considered. Liability for the unpaid part of the loan is clearly indicated in nine countries but can apply in another five.

Foreclosure rules need to be balanced between borrowers and lenders, as regulatory systems tilted to one or the other side tend to stifle the mortgage market. There are also benefits to having legal frameworks that allow the operation of credit information systems, which allow credit scoring. Jurisdictions with stronger legal rights and more extensive credit information systems generally have deeper mortgage markets.

Figure 3.12. The OECD Foreclosure Regulation Index illustrates differences in the balance of rights between borrowers and lenders

Monitor the rise of non-bank real estate finance

Since the global financial crisis the credit quality of structured real estate finance products has broadly improved. Typical mortgage-backed securities are no longer backed by riskier lower-quality subprime and Alt-A collateral. This situation results from the shift in market risk perceptions following the crisis, and the strengthening of regulation and oversight of securitisation activities. Overall, national authorities and international organisations have made considerable progress in identifying and better understanding activities and risks in financial intermediation. The result has been a clear improvement in credit quality for banks’ mortgage supply, but at the cost of some reduction in supply and thus an increase in cost, at least at the margin. However, the low-rate environment that lasted until recently was the dominant factor together with weak supply of new housing, and in many locations real estate prices surged with associated jumps in debt levels of households and corporations.

In parallel, a profound structural shift in real estate finance from structured products to leveraged institutions and collective investment vehicles that perform liquidity transformation, has been occurring in the United States and in several other countries since the global financial crisis. The low-interest-rate environment of the past decade has increased investors’ appetite for yield and supported the growth of collective investment vehicles, including mortgage real estate investment trusts (mREITs) and real estate mutual funds (REMFs). Concomitantly, more stringent capital requirements on mortgage lending activities under the Basel III regulatory framework have weakened banks’ incentives to lend for real estate purchases, opening space for the rise of non-bank mortgage originators and servicers as an alternative to traditional bank mortgage lending. In Europe and elsewhere, institutional investors (including insurance companies and pension funds) and investment funds have shown growing interest in real estate lending, all the while accepting the downside risks from various accompanying shocks.

Downside risks can emerge for some mortgage-backed security (MBS) markets

Real estate finance markets can be vulnerable to a turn in the housing cycle and fragile commercial real estate following the COVID-19 pandemic. The monetary and fiscal support and loan forbearance measures that followed the pandemic alleviated the problems that would otherwise have manifested themselves, especially in the residential sector, which benefited from strong protection (OECD, 2020[16]). For its part, commercial real estate price performance has been much weaker since the outbreak of the pandemic because of both the office space surplus that resulted from the surge in remote working and reduced shopping footfall due to social distancing rules and stay-at-home behaviour. In addition, real estate assets and subsequently real estate finance markets are exposed to medium-term challenges from physical and climate change-related risks, which may lead to credit quality deterioration of non-financial corporations and a declining value of real estate collateral.

Furthermore, mortgages originated by non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), which at least in the United States are generally of lower quality than those coming from banks, are likely to be particularly vulnerable to sharp increases in investor risk aversion. Therefore, a decline in real estate prices, or a shock that implies a substantial deterioration in the credit quality of mortgage borrowers or a significant depreciation of real estate collateral value, may cause mortgage-based security (MBS) prices to decline, implying losses, share redemptions and margin calls for a wide range of financial intermediaries and investors. While international, the MBS market is dominated by U.S. issuance (Box 3.4). Rising investor risk aversion may trigger feedback loops from desired deleveraging to MBS market turbulence and defaults and ultimately lower mortgage availability, real estate prices and overall economic growth.

Box 3.4. MBS markets: the experience of the United States

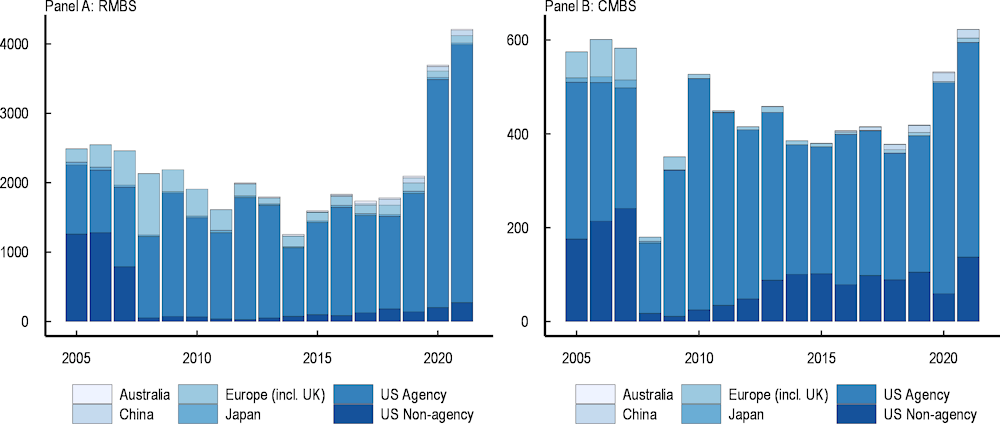

Real estate MBS markets have recovered well in the United States from the global financial crisis, while issuance has remained subdued in other major markets (Figure 3.13). Another notable development is the dominance of MBS issuance by US GSEs. After US MBS markets, Europe and China are the two next largest. While the Chinese real estate MBS market remains small in nominal terms, RMBS and CMBS issuance both recorded their highest growth rates there over recent years.

Figure 3.13. The US real estate MBS market has recovered from the global financial crisis

Note: These figures show the nominal amount of RMBS and CMBS issuance in major MBS markets. US agency issuance includes both agency and residential and multifamily securitisations by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or Ginnie Mae excluding risk transfer deals. All other government agency or GSE securitisations or guarantees and GSE risk transfer deals are part of non-agency ABS or MBS. Other selected RMBS markets include Australia, China, the European Union (including the United Kingdom) and Japan.

The effect of the pandemic on MBS issuance has been diverse across major MBS markets. For instance, agency CMBS and agency MBS purchasing programmes implemented by the Federal Reserve since March 2020 supported record high US agency RMBS and CMBS issuance in 2020 and 2021. However, RMBS and CMBS issuance has declined sharply in most other major markets (except CMBS issuance in Australia and China). Despite the severity of the COVID-19 crisis, residential mortgage delinquencies generally increased only moderately in 2020 in major real estate finance markets, as guarantees and moratoria, which were implemented in many jurisdictions, avoided defaults on many loan exposures that might otherwise have gone sour (Green, 2022[17]).

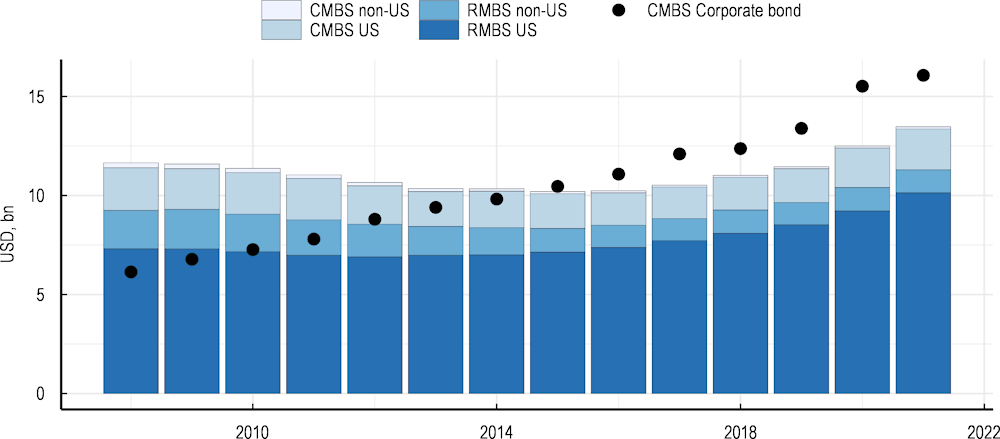

At USD 10 trillion outstanding, US RMBS remain by far the largest segment of the global ABS market of USD 13 trillion in 2021 (Figure 3.14). The US Federal Reserve held about USD 2.6 trillion worth of MBS as of end-December 2021. In comparison, in 2008 global real estate MBS markets were twice as large as corporate bond markets in major real estate finance markets. However, in 2021 the relative size of global real estate MBS markets represented 84% of total outstanding corporate bonds. While global real estate MBS markets have expanded substantially over the last decade, other market-based finance markets have experienced even stronger growth.

Figure 3.14. The US MBS and corporate bond markets are by far the largest

Note: The aggregate amount of corporate bonds outstanding is calculated including data from the United States, the European Union (including the United Kingdom), Japan, Australia and China.

Source: SIFMA, AFME, JSDA, Australian Securitisation Forum, CNABS, BIS Debt securities statistics database, OECD calculations.

The strengthening of the US government-sponsored-entity (GSE or agency) regulatory framework and oversight following the global financial crisis has helped improve US credit standards, with agency MBS being safer than they were a decade ago. Nonetheless, financial innovations continue to flourish in CMBS markets as reflected by the rising market share of commercial real estate collateralised loan obligations (CRE CLOs). These developments recall the innovation-fragility view that identified financial innovations as the root cause of the GFC. It was characterised by the creation of securities perceived to be safe, but exposed to neglected risks. They underscore the need to monitor associated risks and adapt regulation.

Hedging activities on MBS markets, which are fixed-income products sensitive to changes in interest rates, may have substantial spillover effects on US Treasury markets. However, very large Federal Reserve holdings of MBS reduce the impact of interest-rate fluctuations. When interest rates increase, the price of an MBS tends to fall at an increasing rate and much faster than a comparable Treasury security due to mortgage duration extension. To mitigate interest rate fluctuation risk MBS holders use either interest-rate swaps or Treasury sales, which can potentially lead to volatility in the Treasury market.

Concerns have increased following the widespread rise in interest rates in the context of higher inflation and tapering of asset purchases of major central banks, two developments that imply a substantial repricing of Treasury securities. Nevertheless, Federal Reserve holdings of MBS may help to mitigate the impact of hedging activities on the volatility of MBS and Treasury markets. For instance, unlike many institutional investors, the Federal Reserve does not hedge pre-payment risk, because it does not target the duration of its portfolio.

Covered bonds remain key instruments in European mortgage finance

Covered bonds are debt instruments issued by a bank or a mortgage institution that are backed by collateral, a so-called cover pool, which includes real estate mortgage loans and public-sector debt instruments. While covered bonds are a source of secured and low-cost funding, they may increase the refinancing risks that the issuer bank faces on unsecured wholesale funding sources. By contrast with MBS, where a given set of underlying mortgages are transferred to a special purpose entity, covered bonds require the issuer bank to maintain a cover pool of high-quality assets backing the bonds. Since the asset pool backing the covered bonds needs to be replenished, accumulated losses on mortgages that surpass the bank’s capital are concentrated on unsecured debt holders. Therefore, the more covered bonds a bank issues, the higher the risk that its unsecured obligors incur, which exposes the bank to higher rollover risk on its unsecured debt. This differs from MBS, where the mortgage risk is transferred to the buyers of MBS. Greater covered bond funding may thereby exacerbate bank-liquidity risk and increase pressures on unsecured wholesale funding markets. Unprecedented monetary and fiscal support combined with loan forbearance measures following the pandemic have helped to contain mortgage defaults and preserve the resilience of covered bond markets. Notably, the negative credit impact on residential mortgage loans in the cover pool of assets backing the bond has been small. In addition, the impact of the pandemic on the performance of commercial real estate assets may be more severe, but cover pools’ exposures to such assets are limited.

The global covered bond market has expanded substantially over the last decade (Figure 3.15) .Covered bonds backed by mortgages account for the largest share of outstanding covered bonds. Covered bond markets are dominated by European markets but have expanded globally over the last decade, including in the Asia Pacific region, North America and in several emerging economies. Still, top issuers in 2020 remained European banks. However, issuance dried up during the pandemic, because so much policy support was unspent and ended up in higher household savings in the form of bank deposits, which are a particularly low-cost source of bank funding. Little impact on prime residential mortgage markets is expected as policy and regulatory support is withdrawn, but the same cannot be said for commercial real estate assets.

Figure 3.15. The covered bond market has expanded substantially

The role of REITS and REMFs is rising

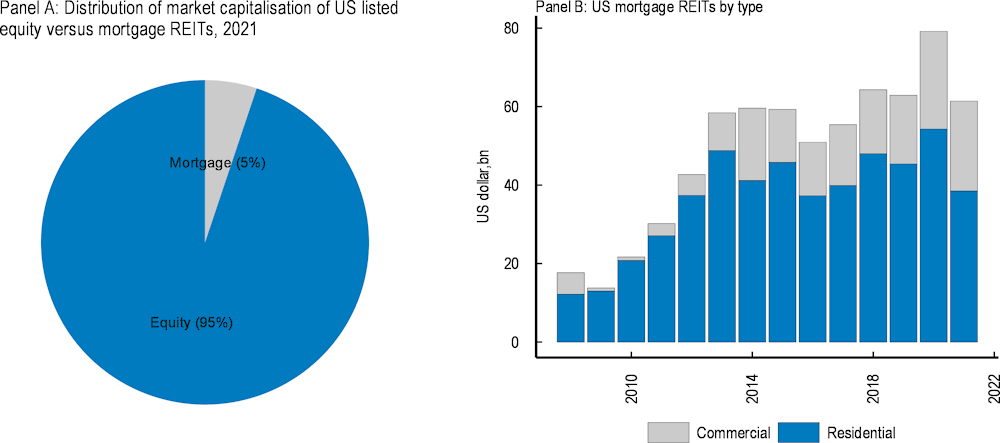

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) are specialised investment vehicles that derive most of their income from real estate-related assets. REITs generally specialise in either owning physical real estate assets or providing debt financing to real estate investors or developers. REITs issue share-like securities that give investors access to more liquid real estate investments than holding physical real estate assets. During the prolonged low-interest-rate environment since the global financial crisis, REITs have provided attractive investment opportunities, because in many jurisdictions they benefit from favourable legal treatment,2 offer relatively higher dividend pay-out ratios compared to equities, and/or provide diversified and liquid real estate investments. Over the past decade, the equity market capitalisation of the REIT industry globally has tripled (from USD 430 billion in 2010 to over USD 1.3 trillion in 2021), some 65% of which is in the United States, though rapid growth has also been recorded in the Asia-Pacific region (Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Trends and challenges in the REIT industry

Within the REIT industry, there are two broad types of REITs: equity REITs and mortgage REITs (mREITs) with very distinct characteristics. Whereas equity REITs invest in physical properties, mREITs invest in mortgages and MBS, making them real estate debt owners. Within mREITs, these entities tend to focus either on residential mortgages and RMBS or commercial mortgages and CMBS.

Most residential mREITs focus their investments on MBS issued by GSEs and are often called agency mREITs. Following the global financial crisis, several mREITs developed business models that buy distressed mortgage assets (both residential and commercial) from banks and other lenders, helping to recapitalise the banking sector, and restructure and service these debts. Most US publicly traded REITs are equity REITs (Figure 3.16, Panel A), but mREITs issuance has grown significantly since the global financial crisis (Panel B). Notably, the market capitalisation of US mREITs has more than tripled over the past decade (from USD 18 billion in 2008 to USD 61 billion in 2021). Though US residential mREITs are still the largest market segment, accounting for 63% of the capitalisation of US mREITs in 2021, commercial mREITs have also been expanding.

Figure 3.16. Mortgage REITs remain small relative to equity REITs despite expanding

Note: These figures show aggregate market capitalisation of US equity versus mortgage REITs from the NAREIT REIT Market Database that includes all US REITs listed in several sectoral indices.

Source: REIT.com, Refinitiv, OECD calculations.

Downside risks surround mREITs, which use short-term financing and leverage. They typically derive their returns from the income generated by underlying mortgages as well as changes in the mortgages’ net present value. Short-term secured financing – notably through revolving credit facilities from banks and other financial institutions, and also borrowing from short-term secured funding (i.e., also known as repo) and bond markets – provides mREITs with funding at low interest rates to purchase long-term assets that provide higher returns. A common practice for mREITs is to multiply the difference between their short-term borrowing rates and long-term lending rates by adding leverage. In this process the mREIT initially uses the cash it raises from investors to purchase MBS. Then it uses those MBS as collateral to borrow money to purchase more MBS, a process that it repeats multiple times. However, the number of rounds is limited, as the repo lender requires a collateral margin on each loan (a gap that serves as a buffer for the repo lender’s protection) or may impose covenants limiting leverage.

Leveraged mREITs are typically vulnerable to substantial rises in interest rates, which hurt their profitability and complicate their refinancing. Maturing short-term funding would have to be rolled over at higher interest rates, which would contribute to an erosion of their profit margin. More importantly, a substantial rise in interest rates would reduce the market prices and net present values of outstanding MBS and mortgages, in turn lowering the value of mREIT assets. If mREIT assets used as collateral for short-term secured funding see their value diminish, they may trigger margin calls and subsequent deleveraging, implying further MBS sales and price declines. A deleveraging spiral could entail substantial losses for a wide range of financial intermediaries and investors.

The onset of the pandemic saw a breakdown in heretofore stable relationships between different mortgage pools due to the bout of extreme risk aversion and heightened volatility. But the Federal Reserve intervened directly by purchasing agency MBS and allowing temporary capital relief to banks so they could keep lending. Together with loan forbearance this action succeeded in stabilising the MBS market as well as short-term markets for repos and commercial paper. However, long after the first wave of COVID-19, some types of US property were still suffering, notably office buildings, lodging and resorts, and health care. More recently, as the financial markets became afraid of a surge in inflation, exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, participants have been comforted by the fact that, historically, real estate and REITs have performed comparatively well in eras of higher inflation during which rents usually kept up with overall prices and property values appreciated.

Closely related to mREITS are real estate mutual funds (REMFs), which are akin to funds of funds. About a sixth of REMFs are exchange listed (including through real estate-focused exchange-traded funds, ETFs). REMFs have expanded sharply from USD 650 billion in 2005 to USD 4.1 trillion in 2021 (ANREV / INREV / NCREIF, 2022[18]). Real estate-focused ETFs are performing liquidity transformation, which renders them vulnerable to share redemptions by investors when market conditions deteriorate. Real estate-focused ETFs provide liquid investments by offering redemptions at higher frequency. As with mREITs the materialisation of redemption risk can force sales, further adding to volatility. REMF net asset values are often subject to particularly high levels of uncertainty, prompting their regulatory overseers to encourage them to cease trading, as for example occurred in the United Kingdom during some periods of the Brexit negotiations. In 2020, REMFs recorded significant outflows following the weakening of mREITs (SEC, 2020[19]). The deterioration in the market liquidity of REMF assets was particularly severe for funds facing larger share redemptions from investors. Notably, REMFs attempted to use a liquidity waterfall strategy, to initially meet increased redemption demand using cash and cash equivalents. However, some REMFs ran out of cash and cash equivalents forcing them to sell real estate assets into increasingly illiquid markets. Developments since the onset of the pandemic have shown that structural vulnerabilities remain in mREIT and REMF products, which are contributing to the price volatility in MBS markets.

Non-bank mortgage lending entails risks

Since the global financial crisis, low interest rates and more stringent bank regulation3 have contributed to the rise of leveraged non-bank mortgage originators and servicers, mainly in the United States (Box 3.6). These non-bank mortgage firms perform liquidity and maturity transformation. Their development has brought several benefits: heightened competition; longer maturity horizons (from insurance companies and pension funds), which lessen the need for maturity transformation; and likely less pro-cyclicality of supply (as no money is created), even if the limited empirical evidence may point in the opposite direction (BIS, 2020[20]). However, as mentioned above, the average credit quality of NBFI mortgages is generally lower than that of banks.

Box 3.6. Trends and international experience in non-bank housing finance

The rise of non-bank mortgage origination and servicing since the global financial crisis has occurred at very different speeds across countries.

Housing mortgages issued by non-bank mortgage lenders have risen substantially in the United States over the past decade, from 30% in 2010 to 55% of total origination in 2020. The market share of banks went below 50% in 2014. Like banks, non-bank mortgage lenders use the originate-to-distribute business model4 and sell a substantial share of their mortgages to government agencies (including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae), which held about two-thirds of all residential mortgages in 2020. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which have been under the conservatorship of the US Treasury since 2008, hedge their credit risk though private mortgage insurance (PMI) and the issuance of Credit Risk Transfer securities (CRTs).5

In China, sources of funding for real estate developers mainly comprise non-banks. Notably, self-raised financing (i.e., equity IPOs, corporate bond issuance and loans from trust companies) represented 70% of total sources of funding for real estate developers in 2020. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the decline in trust loans that already started at end-2017. In 2019, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission introduced more explicit caps on real estate financing for trust companies to prevent them financing property developers that do not have all necessary licenses or meet requirements on shareholders and capital.

In other major real estate finance markets the shares of non-bank residential mortgages have remained roughly stable at moderate levels (i.e., under 10% in Japan, the United Kingdom and the European Union).

As for commercial mortgages available data for major real estate finance markets show moderate non-bank lending ranging from under 5% in Australia to 16% on average in the European Union at end-2020. Nevertheless, there is considerable heterogeneity across European economies, characterised by substantial financing shares from insurance companies (i.e., Belgium, Croatia and Germany,), pension funds and investment funds (i.e., Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Malta and the Netherlands).

Fintech lending has expanded in major real estate finance markets, bringing efficiency gains, while raising potential concerns for financial resilience. The origination process has been streamlined and automated by new entrants, resulting in faster approvals and lower costs, fraud and errors, albeit at the expense of greater vulnerability to cyber attacks (Fuster et al., 2019[21]). Fintech lending promises convenience for borrowers and a more accurate assessment of risks for lenders. Traditional lenders have adopted some of their innovations, blurring the distinction between fintech and traditional lenders. Furthermore, some cooperation has occurred; for example, a bank might contract with a fintech to provide the digital infrastructure for its mortgage originations. By 2020, the two largest fintech firms had between them 30% of all residential originations of the top 25 firms in the United States (which represented two-thirds of the market).

Other forms of non-bank real estate lending include peer-to-peer (P2P) or marketplace lending, balance sheet property lending and real estate crowdfunding. Originations of all these forms of loans were suspended or scaled back during the first half of 2020 following the COVID-19 shock but seem to have recovered since then. New lending technologies have the potential to increase efficiency by reducing operating costs, enhancing the accuracy of mortgage transactions and reducing fraud. Yet fintech digital platforms are also vulnerable to external threats and risks of cyber-attacks, which can expose consumers to higher risks of loss and other harms, including from third-party fraud.

Non-bank financial institutions’ high leverage and considerable liquidity transformation involves risks (Box 3.7). Furthermore, the performance of these institutions also depends on real estate prices, the quality and diversification of their assets, their reliance on the occasionally volatile wholesale funding market, periodic redemption surges and links to other financial markets.

Box 3.7. Non-bank housing finance: leverage, liquidity and other main risks

United States

Non-bank mortgage lenders are exposed to liquidity risk because of their business model, which includes a combination of various funding sources6 and equity. The reliance of these institutions on short-term warehouse lines of credit to fund long-term mortgages may expose them to liquidity mismatch. They can face liquidity shortages following an unexpected shock that leads to less liquid securitisation markets. In the event of a shock that negatively affects the credit quality of mortgages and raises investor concerns over non-bank mortgage lenders, these institutions are likely to experience reduced access to funding at a higher cost. Unlike banks, which can rely on deposits as a fairly stable funding source, non-bank mortgage lenders lack such a largely captive deposit base and can be subject to sharp changes in funding costs.

Non-bank mortgage lenders are increasingly exposed to volatility through the rising share of mortgage servicing rights (MSRs) on their balance sheets. For instance, non-bank mortgage lenders serviced 60% of mortgages in 2021, up from 6% in 2011 (CSBS, 2021[22]). They have also expanded their mortgage servicing market share largely through bulk purchases of MSRs of non-performing loan portfolios originally held by banks. Non-bank mortgage servicers are exposed to liquidity risk because when a mortgage defaults, the servicer not only loses servicing income but must also keep settling payments to investors, tax authorities and insurers using its own funds, as well as incurring the high cost of servicing delinquent mortgages.7 In particular, Ginnie Mae servicers are exposed to greater liquidity risk, as they are likely to face higher impaired or defaulted loan servicing (Ginnie Mae, 2016[23]). For loans in both GSE (including Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) and Ginnie Mae pools, the mortgage borrower takes the initial credit loss. Then, the private mortgage insurance company or the government entity that guarantees the loan takes second-round losses. However, Ginnie Mae servicers are expected to bear any credit losses that the government or the insurer does not cover.

A collapse of some non-bank US mortgage lenders and servicers could amplify negative shocks, but regulators have recognised the risk and strengthened regulatory oversight. Subsequently, the authorities must assess the risk that stresses in the non-bank sector will be transmitted to the regulated banking system, especially because the relationships between them are complex and opaque.8 If non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers were to default in large numbers, then overall mortgage supply would shrink and real estate prices decline. Accordingly, early in the COVID-19 crisis the US Federal Reserve supported the MBS market, and mortgage forbearance, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of March 2020 and higher unemployment assistance all helped to underpin the financial sector and the real economy (GAO, 2021[24]). The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) and Ginnie Mae have announced several measures to facilitate liquidity by making it easier for mortgage lenders and servicers to make various forms of short-term cash advances.

Europe

In a number of European countries, insurance companies and investment funds have some exposure to solvency or redemption risks from their commercial real estate investments (i.e., Belgium, Bulgaria, Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal and Slovenia). Yet pension funds in most European jurisdictions face moderate exposure to the real estate sector. Valuation losses from commercial real estate exposures could make affected insurance companies and investment funds less willing or able to provide new financing in several European jurisdictions. On the whole, however, the relatively small direct exposure of pension funds and insurance companies to the real estate sector in most jurisdictions and the fact that indirect investments in real estate are often internationally diversified and covered by risk management frameworks should reduce the risks of financial distress

Source: (OECD, 2021[25])

There is a need to manage risks from non-bank mortgage finance

The efficacy of regulatory tools for mREITS and REMFs also needs to be assessed to ascertain whether or not a more comprehensive risk-based approach is required to regulating non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers. Nascent vulnerabilities should be addressed, without undermining the benefits of market-based finance. The key challenge is to determine whether sufficient tools are available to incentivise leveraged real estate non-bank financial institutions to take heed of liquidity and maturity transformation risks to avoid unnecessary cyclical spillovers to the rest of the financial system and the real economy (Box 3.8). Beyond policies mitigating poorly coordinated redemptions, significant liquidity mismatch suggests a need to expand liquidity management tools so that REMFs can absorb outflows without resorting to the option of redemption suspensions (IMF, 2021[26]). Ireland provides an example of reforms to regulate property funds with a view to enhancing financial stability (Box 3.9).

Box 3.8. Open-ended funds: vulnerabilities and reform options

In 2017-18, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) made considerable efforts to articulate key structural vulnerabilities from open-ended funds (OEFs) and detailed recommendations were developed by IOSCO.9 In October 2021, the FSB issued policy proposals to enhance money market fund (MMF) resilience, including with respect to the appropriate structure of the sector and of underlying short-term funding markets (Financial Stability Board, 2021[27]). Like open-ended investment funds, REMFs are prone to share redemptions. Therefore, among the key policy proposals by the FSB for MMFs, some measures could also be relevant for REMFs, including:

A capital buffer of sufficient size or a leverage limit would mitigate the risk of losses by investors, and thus reduce their incentives to rush to redeem shares. Imposing criteria for eligible assets would mitigate the impact of large redemptions by reducing the liquidity transformation performed by REMFs. REMFs would have to invest a higher portion of their assets in shorter dated and/or more liquid instruments, making them less dependent on liquidity conditions in the markets for the assets they hold, and reducing the first-mover advantage for redeeming investors. For example, the Central Bank of Ireland is introducing a 60% leverage limit on the ratio of property funds’ total debt to their total assets and guidance limiting liquidity mismatches for property funds (Box 3.9).

Swing pricing10 could help mitigate redemption risk and first-mover advantages arising from mutualised liquidity, if it is implemented in a manner that is likely to pass the costs they impose on the fund on to redeeming investors. In addition, basing redemption values on minimum balance at risk could reduce the first-mover advantage from potential losses in a REMF because investors remaining in the fund would no longer bear losses disproportionately.

Additional liquidity requirements and the use of liquidity-management tools could make REMFs more liquid on the asset side and provide funds with flexible risk-management solutions. While these policy measures could be beneficial to strengthen the resilience of REMFs, further consideration should be given to the prioritisation and combination of policy measures into a reform package to address identified REMF vulnerabilities by jurisdiction.

Box 3.9. Measures to limit leverage and liquidity mismatches for property funds in Ireland

Funds investing in property have become key participants in the Irish commercial real estate (CRE) market, holding some EUR 22 billion of property as of 2022.11 This growing form of financial intermediation offers potential benefits for macroeconomic and financial stability. Often established and funded by overseas investors, property funds provide an alternative channel of financial intermediation for investment in the commercial real estate market, reducing reliance on domestic sources of capital.

This changing nature of financial intermediation also raises the potential that new vulnerabilities could emerge, so it is important that the macroprudential framework adapts accordingly. Given the growth in the property fund sector, the resilience of this form of financial intermediation matters more today for the functioning of the overall commercial real estate market than a decade ago. In turn, dislocations in the market have the potential to cause and/or amplify adverse macroeconomic consequences, through various channels. These include potential losses on lenders’ exposures, funding constraints for borrowers using commercial real estate as collateral and potential adverse implications for construction sector activity.

To make this growing form of financial intermediation more resilient to shocks, in November 2022, the Central Bank of Ireland introduced macroprudential measures for property funds. These were the first policy measures to be introduced under the third pillar of the Central Bank’s macroprudential framework, covering non-bank financial intermediaries. In particular, it introduced a 60% leverage limit on the ratio of property funds’ total debt to their total assets (the “leverage limit”) and Central Bank Guidance (the “Guidance”) to limit liquidity mismatch for property funds.

The main risk targeted by the Central Bank relates to the potential that financial vulnerabilities in the property fund sector lead to forced selling in times of stress. Excessive leverage and liquidity mismatch are potential sources of vulnerability in property funds.12 The presence of high leverage and liquidity mismatch increase the risk that – in response to adverse shocks – some property funds may need to sell property assets over a relatively short period of time, causing and/or amplifying price pressures in the commercial real estate market.

The Central Bank of Ireland provides a five-year implementation period to allow for the gradual and orderly adjustment of leverage in existing property funds and an eighteen month implementation period for existing funds to take appropriate actions in response to the Guidance. The Central Bank authorises new funds only if they meet the 60% leverage limit, while it expects that property funds authorised on or after 24 November 2022 to adhere to the Guidance from their inception.

The proposed measures aim to safeguard the resilience of this growing form of financial intermediation, so that property funds are better able to absorb – rather than amplify – future adverse shocks. In turn, this should better equip the sector to continue to serve as a sustainable source of investment in economic activity.

For mREITs liquidity management challenges are related to maturity mismatch and debt rollover risk, which result from the use of short-term secured funding and/or bank warehouse credit lines to finance longer-term MBS and mortgages. Notably, risk-management tools aimed at strengthening the ability of mREITs to absorb losses and strengthen their liquidity positions would help to mitigate their sensitivity to margin calls.

In the United States, non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers are regulated for safety-and-soundness purposes and are subject to capital and liquidity requirements. While non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers do not pose the risk of a claim on the deposit insurance fund, financial distress in that sector may be a substantial threat to financial system resilience, both directly and through its interconnectedness with the regular banking system. In 2019, the US Conference of State Bank Supervisors and the American Association of Residential Mortgage Regulators jointly published procedures for examining the safety and soundness of all financial institutions that have since been adopted in whole or in part by most states (CSBS, 2019[28]; CSBS, 2021[22]).

While these prudential standards are welcome, the Final Model Standards could be further enhanced. In particular, the capital regulatory standards are not defined using a risk-based approach for non-bank mortgage lenders’ assets, in contrast with the bank regulatory framework that takes many factors into account. Also, neither the maturity and capacity of its debt facilities, nor the effectiveness of its hedging strategies, nor the idiosyncratic aspects of the lender’s business model are considered for liquidity requirements. In addition, the GSE liquidity surcharge of 200 basis points when delinquencies reach a certain level may require non-bank servicers to raise more funds at a time when they may already be under financial stress. A counter-cyclical requirement would be a more suitable approach. Therefore, regulatory requirements for non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers may not be completely adequate relative to the risks posed by these firms. Further consideration should be given to additional relevant risk factors to define capital and liquidity requirements for non-bank mortgage lenders and servicers. However, if regulators detect rising vulnerabilities at a particular firm, they may decide to impose more stringent capital and liquidity requirements on a firm-by-firm basis to mitigate idiosyncratic risk and spillovers that may threaten the resilience of the sector and possibly beyond. This suggests that more work is needed to further develop and implement various tools to address vulnerabilities of mortgage lenders and servicers. Also, an assessment of the use and efficacy of these tools would ensure that they help to mitigate excessive risk taking with respect to liquidity and leverage, and improve resilience during periods of stress.

Harness mortgage finance for housing decarbonisation

Housing finance has a key contribution to bring to cutting emissions from the residential sector, an effort that is going to require costly investment (Chapter 2). Mortgage lenders can support housing decarbonisation at different stages:

For new construction, mortgage lenders can recognise that homes built in accordance with standards compatible with the net-zero target will imply lower recurring energy costs and avoid the risk of expensive later retrofitting by their owners. These two characteristics respectively improve the cash flow and collateral value of borrowers, both enhancing the credit quality of the loan. Transparent, reliable energy certification would facilitate the take-up of building loans that can recognise the lower risk associated with a strong environmental quality of construction.

For existing homes, similarly, reliable certification would make it easier for banks to recognise the credit enhancement, also in terms of both collateral value and borrower cash flow, from greater energy efficiency.

Retrofitting is currently missing a lending market. For an individual dwelling, the amount is much smaller than a mortgage, complicating the coverage of administrative and other issuance costs. The consumer credit market is also ill suited to the funding of retrofitting: the payback period of retrofits is typically longer than the maturity of consumer loans, and the higher risk associated with a consumer credit results in elevated interest rates that can make retrofitting investment unprofitable. Again, reliable, transparent information on the energy quality of the retrofitted homes would help lenders to recognise the specific benefits of energy-efficiency renovation loans, by comparison for instance with consumer loans, such as reducing future energy bills and raising the value of the home. Such an advance would create more favourable conditions for deep markets to develop for the funding of retrofitting.

Green building rating systems have proliferated

A variety of green building rating systems (GBRSs) have been developed to provide the information required to facilitate the incorporation of environmental objectives in the buildings sector. GBRSs are typically third-party, voluntary and market-driven standards, which provide information to real estate investors and bondholders about an existing building or a construction project’s performance from a sustainability and environmental perspective. Favourable energy ratings tend to be reflected in higher property prices (Taruttis and Weber, 2022[29]; Copiello and Donati, 2021[30]; Fuerst et al., 2015[31]; Hyland, Lyons and Lyons, 2013[32]). However, evidence on their effect on housing loans is scarcer, although analysis of Dutch residential mortgage data linked greater energy efficiency with a lower probability of default (Billio et al., 2021[33]). Furthermore, studies of commercial mortgages in the United States (which fund both office and multi-family residential buildings) found that default risk is higher for borrowers facing higher energy costs (Mathew, Issler and Wallace, 2021[34]) and significantly diminishes after the funded buildings became energy certified (An and Pivo, 2018[35])).

Box 3.10. The rise of green building rating systems: Types and international experience