This chapter outlines the variety of international instruments that collectively form an international rulemaking ecosystem. It organises these instruments into distinct “families”, highlighting the defining features, benefits and challenges of each. This provides a basis for understanding how different instruments compare and interact, how they are situated within the broader architecture of global governance, and how they are defined and adopted across international organisations. The sheer scale and diversity of the international rulemaking ecosystem can pose challenges for those seeking to use international instruments. This chapter shows the efforts IOs are undertaking to bring greater clarity into their instruments through transparent definitions and terminologies, making them accessible in databases, and introducing procedures to foster coherence.

Compendium of International Organisations’ Practices

1. Building understanding of the variety of international instruments

Abstract

Introduction

The international rule-based system is characterised by a fast-growing body of international instruments designed to support countries in addressing their policy challenges. The international organisations (IOs) that have been collaborating within the remit of the IO Partnership – some 50 to date (see Annex A) – are estimated to have collectively produced some 70 000 international instruments of varying denominations, nature and legal effects (OECD, 2016[1]) (OECD, 2019[2]). These instruments are the result of international regulatory co-operation within a multilateral setting, following specific decision-making processes agreed upon by members. Ultimately, these instruments help feed into countries’ domestic rulemaking with international evidence, expertise and co-ordinated approaches. However, in the diverse landscape of IOs, the terminologies and legal effects of international instruments vary from one organisation to another. Navigating the ecosystem of international instruments is not an easy task for IOs or their constituencies. For the ultimate beneficiaries of these international instruments, the heterogeneity of the international normative framework maintains the image of a nebulous list of distant principles or rules.

A clearer picture of existing international instruments and their legal effects is vital to supporting IOs in making more informed decisions as to which instrument to develop and why. A typology on the families of instruments can help IOs co-ordinate with each other more easily on joint instruments despite their different legal and institutional contexts. This will also support national policy makers to navigate the complex international landscape and use different instruments more systematically in support of their domestic policy objectives.

This section of the Compendium of IO Practices provides clarity to the global rulemaking landscape, by distilling the multiplicity of international instruments into various groups or ‘families’ building on considerations from past analytical work carried out with IOs (OECD, 2016[1]) (OECD, 2019[2]). This paves the way for a consideration of their defining features, benefits and challenges, to build understanding among IOs, their constituencies and the broader community of policy makers on what can be expected from a specific international instrument.

Rationale

The international landscape is marked by a diversity of instruments and vocabularies, reflecting a diverse global governance system. A variety of IOs have emerged throughout the years to engage various constituencies in the pursuit of different policy objectives. Each IO is founded by its specific constituent instrument and exercises the powers attributed to it by this document within the areas under its purview (Combacau and Sur, 2016[3]). A corollary of this is that each IO has its own decision-making processes agreed on by its members and develops its own style of normative instruments, often several different types within a broad “ecosystem” of normative instruments (OECD, 2019[2]). Overall, with limited exceptions, there is no common understanding across IOs of the key features and legal effects of different instruments. As most instruments adopted by IOs have no commonly defined status, the same descriptive term for an instrument can have different features depending on the international organisation developing it, while different labels may cover the same types of instrument.

The multiplicity of international instruments and differences in approaches among IOs may result in uncertainty and confusion as to the key features and legal effects of such instruments. Different types of instruments reflect specific benefits and responses to different situations and challenges, and the ways in which they are developed varies accordingly. For instance, Legally binding international instruments such as international agreements, conventions and decisions, which can be adopted by intergovernmental organisations’ governing or decision-making bodies or by ad hoc negotiating groups (e.g. negotiating conferences) specifically set up for this purpose. They are addressed to states, who – if any necessary procedures to become parties to them have been completed - will have an obligation under international law to implement them (OECD, 2019[2]). Non-binding international instruments may be used to capture a commitment to policy principles or best practices but without creating a legally binding obligation to implement these in any specific manner. International technical standards, as understood by the current report,1 are commonly developed in response to a targeted need expressed by stakeholders through a bottom-up approach and are voluntarily adopted by states if they are perceived as necessary (OECD, 2016[1]).

The variety of international instruments may be challenging for different regulators and policy makers to navigate, countering the very objective of supporting countries in enhancing good governance and their own rulemaking processes. Countries are members of more than 50 IOs on average (OECD, 2013[4]). States and other potential members and users have a multiplicity of international instruments to understand and use in their own regulatory contexts. At the same time, this multiplicity is often grounded in the particular history and functioning of each organisation and may also arise from a desire by countries to respect these specificities and avoid a “one size fits all” approach. Binding international treaties to which countries are parties are generally well-known by central governments and legislators, and often made accessible in public repositories. But such consolidated information is usually not available on all international instruments applicable across different sectors and resulting from different international bodies. In addition, international organisations have developed organically, leading to mandates and rules that may overlap and that are not always fully consistent with each other. Understanding this international landscape is essential to identifying the international rules that can best address national and local challenges and understanding how to use them effectively, not least because of their varying legal effects. Acquiring this knowledge can bolster local rulemaking capacities, and support the alignment and co-ordination of approaches across constituencies (OECD, 2018[5]). Improving understanding of the ecosystem of international instruments is therefore fundamental to ensuring that they are well-used by IO constituencies.

Differences in terminology used in relation to international instruments can also pose a challenge for collaboration between IOs. In particular, these differences need to be taken into account in agreements on the joint use of instruments, or referencing or endorsing other organisations’ instruments. Common understandings, definitions and aligned processes can help IOs work together to achieve common goals, and to overcome differences in rulemaking procedures without necessarily going as far as developing joint instruments (see Chapter 5). The definition of key terms used in the UN Treaty Collection,2 for example, outlines some general characteristics and purposes of treaties, conventions and declarations and helps to bring clarity into how these terms are used within the UN framework. Similarly, the WTO/TBT’s Six Principles for International Standards frame the process for developing “international standards” (within the understanding of the WTO) across a variety of standard-setting bodies (OECD/WTO, 2019[6]).

Typology: families of instruments

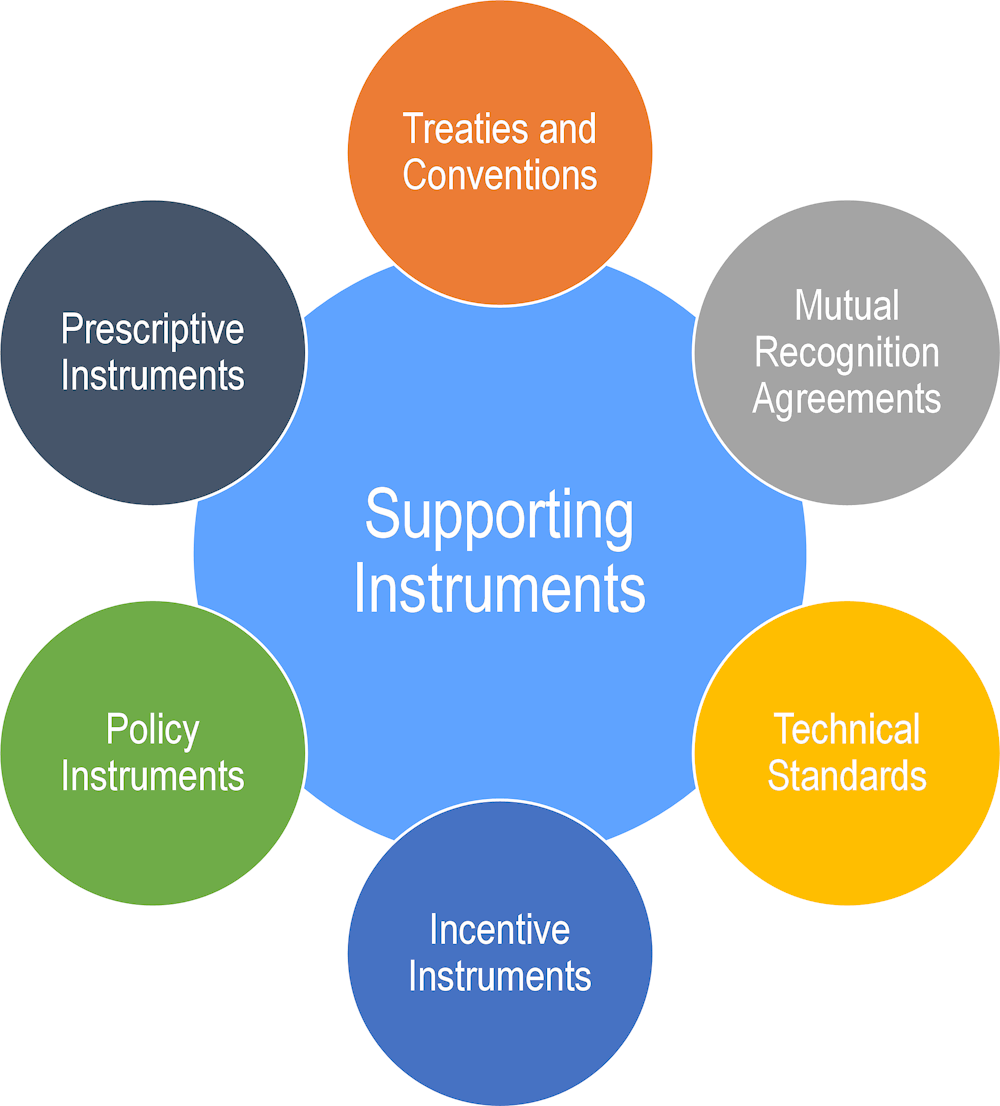

Within the diverse landscape of international instruments, some patterns can be identified across the various instruments adopted by IOs, which allows them to be grouped into broad families with shared characteristics (Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1).3 The figure and table below provide an overview of the families of instruments and their defining features, benefits and challenges. However, specific modalities and definitions may vary between IOs and the typology presented is not intended as an exhaustive categorisation of every type of instrument. There are significant fluidity and overlaps across families. International instruments form a continuum rather than a series of distinct categories. For example, treaties and conventions can be complemented by incentive instruments, supporting instruments or policy instruments, and international technical standards can serve as a basis for drafting treaties and conventions.

Figure 1.1. Families of international instruments developed by international organisations

Table 1.1. Families of instruments: defining features, benefits and challenges

|

|

Defining features |

Benefits |

Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Treaties and Conventions |

“An international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation” (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969). Subject to common definition and understanding, their provisions are legally binding, negotiated by States directly or under the supervision of an IO. |

Generate high levels of compliance, follow established processes of engagement, implementation and evaluation, and ensure significant transparency, all of which enhance predictability of the regulatory environment across borders. |

Resource-intensive creation process, requires significant political capital, may be disproportionate to the challenge addressed, finding the right balance between uniformity and the flexibility to accommodate national circumstances, ensuring updating mechanisms are available for rules to remain relevant, domestic procedures for countries to become Parties to a multilateral treaty could be lengthy (ratification process). |

|

Prescriptive Instruments (e.g. decisions, resolutions, directives) |

Instruments with legally binding provisions, which are adopted by within the framework of IOs (generally IGOs), through the intermediary of governing or decision making bodies composed of IO Member States (OECD, 2019). Require transposition and enforcement to fulfil international commitment. |

Can be tailored to local institutional contexts so long as regulatory objectives are achieved, draw legitimacy associated with compliance with international obligation. |

Members responsible for implementation; difficulties of monitoring/evaluation due to differences in transposition and implementation processes; possible resistance from implementers. |

|

Mutual Recognition Agreements |

Recognition of equivalence of legal decisions, norms and standards, compliance and certification procedures, and product and other requirements across jurisdictions. Depending on their nature, they can be both legally binding (usually bilateral governmental MRAs) and non-binding (usually multilateral MRAs). |

Preserve regulatory frameworks, low initial transaction costs, localised accountability. |

Require significant mutual trust, long-term transaction costs of monitoring regulatory changes |

|

Policy Instruments (e.g. policies, statements, declarations, communiqués) |

Express political commitment/statement of purpose on a given subject, non-binding. |

Provides overarching strategic direction, guides actions of members, sets a shared agenda. |

Lack of targeted applicability to certain policy areas/sectors |

|

Incentive Instruments (e.g. model laws, legislative guides, best practices, guidelines, codes of practice) |

Encourage certain behaviours, issue detailed guidance, non-binding. |

Carry normative weight, draw upon broad range of experiences to develop instruments, flexibility to adjustment to local circumstances, less resource-intensive. |

Non-binding nature may limit or alter compliance/adherence/implementation. |

|

Technical standards |

Instruments pertaining to this family tend to be developed “in response to a need in a particular area expressed by stakeholders through a bottom-up approach” (OECD, 2016). They are referred to by certain Organisations, though not all, as “international standards” as per the WTO TBT Committee Decision on Principles for the Development of International Standards, Guides and Recommendations. |

Draw upon specialised knowledge, produce administrative streamlining and economic gains, encourage a sense of ownership through a bottom-up approach. |

Require more frequent updating than other policy instruments, specialised nature and terminology may reduce scope. |

|

Supporting instruments |

Facilitate the implementation of normative instruments adopted by IOs (OECD, 2019). |

Bridge policy instruments with modes of practical implementation. |

May leave insufficient room for member discretion, or be of limited applicability to particular contexts. |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

State of play on the variety of international instruments

The international normative landscape today

Variety of international instruments

IOs adopt a wide variety of international instruments with external normative value. While the approaches to international rulemaking vary across IOs and the ability to design and develop an international instrument depends on their respective mandates, the following categories of international instruments can be identified in the broader international normative landscape (OECD, 2016[1]) (OECD, 2019[2]):

Legally binding instruments that are directly binding on contracting parties either upon signature or upon ratification depending on the provisions of the instrument (e.g. treaties and conventions, agreements, decisions and other forms of prescriptive instruments);

Non-legally binding instruments which by nature or wording are not intended to be legally binding.

Where States transpose these instruments (or some of their provisions) into domestic legislation or recognise them in international legally binding instruments such as treaties, the relevant instruments or provisions acquire legally binding value (e.g. Mutual Recognition Agreements, model laws, legislative guides)

Statements of intent or guidance which are aimed specifically at encouraging certain behaviours and pooling experiences, or framing priorities and expressing commitments (e.g. declarations, guidelines, best practices).

It is worth noting that the proportionate use of non-legally binding instruments over those which are legally binding has increased, and continues to do so (OECD, 2016[1]) (OECD, 2019[2]). This is all the more the case that all the IOs adopting legally binding instruments also adopt non-legally binding ones (OECD, 2016[1]).

The variety of instruments is also present within individual IOs. Most IOs adopt many different types of instruments, and this can range from one type of instrument (e.g. ASTM International standards) to 16 types of instruments (2018 IO Survey) (OECD, 2016[1]). The selection and use of different instruments are systematic for certain IOs, but merely the result of living practice and ad-hoc processes for others. The extent of systematisation frequently depends on the membership characteristics, governance arrangements, rulemaking areas, founding mandates, and organisational objectives of IOs. For instance, intergovernmental organisations (IGOs) adopt a wider range of instruments than international private standard-setting organisations – which focus primarily on issuing international technical standards – and trans-governmental networks of regulators (TGNs), which generally develop best practice documents and guidelines (OECD, 2016[1]) (Abbott, Kauffmann and Lee, 2018[7]). With the exception of treaties, which are defined under international law and notably the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties,4 there is no common denomination and/or definition of the various international instruments produced by IOs. This variety is reflected in the multiple terms used by IOs to qualify the same type of instrument, and in that a single label may cover instruments with different attributes (OECD, 2016[1]).

For example, the term “recommendation” is typically understood very differently across IOs. While some commonalities can be identified, recommendations are most often used as non-legally binding instruments, embodying characteristics of different “families” of instruments by different IOs (Figure 1.1), whether policy, incentive or supporting instruments (Box 1.1).

Beyond the definitions provided under international law, IOs themselves do not necessarily define their instruments. They sometimes rely on the texts of founding documents, or following practice over time to develop an understanding (2018 IO Survey). Because of this absence of definitions at the international level and at the level of individual IOs, there has not been any generally-accepted typology of IO international instruments to date.

Box 1.1. Diversity in the definition of recommendations across IOs: selected examples

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) refers to ‘strategic policy recommendations’ (APEC, 2020[8]), which set overarching goals and initiatives and are issued by committees and working groups to APEC Leaders.

The Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) Council of Ministers may issue recommendations which are non-binding in nature (Article 10(1) and 10(5) of the COMESA Treaty (COMESA, 2000[9]).

International Labour Organization (ILO) Recommendations (ILO, 2020[10]) provide guidance and are not subject to ratification by ILO member States. While certain recommendations stand alone, the great majority function as supplementary instruments to one or more conventions adopted concurrently or previously. These serve a variety of functions, including to focus on a particular aspect of the subject matter not covered by the convention, offer a higher level of protection, produce proposals to support ILO constituents in applying the convention which they accompany, or provide guidance specifically addressed to employers and workers (which are independent non-State actors and therefore do not directly assume obligations under international law, e.g. in the auspices of the Social Dialogue). While the content of Recommendations is non-binding, they may create reporting obligations for Member States (Article 19, paragraph 6(d) of the ILO Constitution). This aims to enhance compliance by reminding Members of unimplemented conventions and recommendations. To date, the ILO has adopted a total of 206 recommendations.

The International Organization of Security Commissions (IOSCO) produces and circulates recommendations which function essentially as best practices documents, such as in the case of the Recommendations for Liquidity Risk Management for Collective Investment Schemes (IOSCO, 2018[11]).

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines recommendations (IUCN, 2020[12]) as requests and calls for action and change, based on formal decisions of Members, and addressed to other agencies, third parties, or the world at large. However, it is important to note that there appears to be no official, organisation-level, explicit definition in this regard.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (OECD, 2020[13]) defines recommendations as “OECD legal instruments which are not legally binding but practice accords them great moral force as representing the political will of Adherents. There is an expectation that Adherents will do their utmost to fully implement a recommendation. Thus, Members which do not intend to do so usually abstain when a recommendation is adopted, although this is not required in legal terms”. 170 OECD Recommendations are in force today, and the authority to undertake this action is embedded in Article 5(b) of the OECD Convention.

International Organization of Legal Metrology (OIML) Recommendations (OIML, 2020[14]) are designated as model regulations that establish the metrological characteristics required of certain measuring instruments and which specify methods and equipment for checking their conformity. OIML Member States are morally obliged to implement these Recommendations to the greatest possible extent. As the principal instrument of the OIML, 147 Recommendations have been issued to date.

The Secretariat for Economic Integration of Central America (SIECA) refers to recommendations as legal instruments that contain principles guiding the adoption of future, binding “administrative acts”, i.e., resolutions, regulations and agreements (Art. 55.4 of the Guatemala Protocol (SIECA, 1993[15]). Recommendations are non-binding and do not generate specific duties or obligations, but their principles are expected to be observed.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) approaches recommendations as documents which provide advice, technical input and expertise to advance the implementation of the Convention, Kyoto Protocol, and Paris Agreement. These are produced by dedicated subsidiary bodies and in some instances constituted bodies, which report to and remain under the authority and guidance of their respective governing body. The Recommendations of the Standing Committee on Finance (UNFCCC, 2016[16]) provide an illustrative example of this.

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) standards are presented as recommendations (WIPO, 2020[17]) and are directed to States and IOs, in particular to their national or regional industrial property offices, to the International Bureau of WIPO, and any other national or international institution interested in industrial property documentation. Under the organisation’s Development Agenda, WIPO adopted 45 Recommendations in 2007 (WIPO, 2007[18]). These covered technical assistance and capacity-building; norm-setting, flexibilities, public policy and public domain; technology transfer, ICTs and access to knowledge; assessment, evaluation and impact studies; institutional matters including mandate and governance; and other issues.

Source: 2018 IO Survey, Author’s elaboration based on inputs from IOs.

Nevertheless, looking at international instruments holistically, there is a complementarity between the different types of instruments, forming an overall “ecosystem of instruments”. In this sense, Some instruments can be considered as “primary”, in that they provide a broad framework for operation (typically treaties and conventions), whereas other instruments can be thought of more as “secondary” or “accessory to a primary instrument”. The latter either prepare the ground ex ante (for example by building political momentum via declarations) or support implementation ex post (i.e.through “supporting instruments”) (Box 1.2).

While there is a widespread use of all families of instruments, the families of instruments that are non-legally binding (e.g. policy instruments, incentive instruments, international technical standards, and supporting instruments) tend to be used much more often than legally binding ones. This may be explicable in that non-legally binding families of instruments are often emanations of treaties or prescriptive instruments which lay down the foundational core of legally binding obligations (OECD, 2016[1]).

Box 1.2. Examples of the interaction between primary and secondary international instruments

Article 6 of the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (OECD, 2011[19]), developed jointly by the OECD and the Council of Europe, requires the Competent Authorities of the Parties to the Convention to mutually agree on the scope of the automatic exchange of information and the procedure to be complied with. To support the implementation of the provision, two multilateral competent authorities agreements have been developed at the OECD: the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement on the Exchange of CbC Reports (OECD, 2020[20]) for the automatic exchange of Country-by-Country Reports, and the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement on Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information (CRS, 2020[21]) for the automatic exchange of financial account information.

Adopted in 1979, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE)’s Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP) (OECD, 2019[2]) (OECD; UNECE, 2016[22]) (UNECE, 1979[23]) was preceded by political statements from two key international events that helped build political momentum for multilateral solutions to environmental problems: the 1972 Stockholm Declaration from the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, and the Final Act of the 1975 Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe held in Helsinki. Since its adoption, the Convention has gone through different stages including the adoption of seven protocols signed between 1985 and 1999 addressing key air pollutants. A number of guidance documents adopted together with the protocols provide paths to secure implementation and compliance of the CLRTAP.

The Parties to the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (OECD, 1997[24]) have agreed to put in place new measures that will reinforce their efforts to prevent, detect and investigate foreign bribery with the adoption of the Recommendation for Further Combating Bribery of Public Officials in International Business Transactions by the OECD Council (OECD, 2009[25]).

SIECA classifies its instruments into three broad groups. These include Principal or Original Laws (SIECA, 2020[26]), which include constitutive treaties of the Central American economic-political community, operating within the institutional framework of the Central American Integration System (SICA). These are supported by Complementary Laws (SIECA, 2020[26]), which signify international treaties that develop the provisions of the Principal Law, as well as Derivative Laws or Administrative Acts (SIECA, 2020[27]), which are decisions emanating from regional bodies that are directly applicable and binding for member states.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Radio Regulations (RRs) (ITU, 1995[28]) are adopted by World Radiocommunication Conferences and are complemented by Rules of Procedure (RoPs) that are adopted by the Radio Regulations Board. ITU-R Recommendations may be incorporated by reference into the RRs, as appropriate.

The United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, (the “Singapore Convention on Mediation”, adopted in 2018) is an example of a primary instrument of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). Its use in practice is supported through domestic enactment of the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Mediation and International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, 2018 (amending the Model Law on International Commercial Conciliation, 2002). The United Nations Convention on the Use of Electronic Communications in International Contracts (New York, 2005), which came after the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Signatures (2001) and the UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Commerce (1996), turned the provisions in the non-binding incentive instruments into an international (and binding) agreement.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on IO practice templates and inputs from IOs.

Variety of rulemaking processes

The process for developing and adopting instruments generally varies from one organisation to another (OECD, 2016[1]) (OECD, 2019[2]). The heterogeneity of international instruments and rulemaking processes is partly explained by the diversity in the types of IOs and their activities, developments in the international organisations’ environments and in changing global circumstances (OECD, 2019[2]).

Treaties, prescriptive instruments and policy instruments such as recommendations and political declarations, as well as incentive instruments such as model laws, are mainly adopted by IGOs and secretariats of conventions (OECD, 2016[1]). International technical standards are typically developed by international private standard-setting organisations which tend to focus on those instruments. However, a number of open-membership IGOs also produce such standards (e.g. IAEA, WMO) (OECD, 2016[1]).

These rulemaking processes also display substantial variations within organisations themselves (OECD, 2019[2]) (2018 IO Survey). On the one hand, IGOs and secretariats of conventions adopt a wide variety of instruments. On the other hand, TGNs and international private standard-setting organisations tend to adopt fewer families of instruments (OECD, 2016[1]). This can be generally attributed to the various mandates of different types of IOs. While the subject matter covered by IGOs is broad in nature, the activities of TGNs foreground information-sharing, issuing best practices and producing guidance, and international private standard-setters (unsurprisingly) develop international technical standards.

Challenges posed by the variety of international instruments

The variety of international instruments, together with the sheer volume of such instruments today (which exceeds 70 000) (OECD, 2016[1]), may be challenging for those wishing to navigate the international normative landscape. Authorities regulating at the national level may struggle to identify the international instruments existing in their area of work, and thus to make use of them. Countries tend to have repositories of treaties that they are parties to, but rarely – if ever – possess broader repositories of all international instruments that exist in different sectors and that could apply to them (OECD, 2018[29]) (OECD, 2020[30]) (OECD, 2016[1]).

According to the 2018 IO Survey, 19 IOs have processes for developing, adopting or revising instruments that emerge from living practice,5 and three IOs6 do not follow any specific process (OECD, 2019[2]). The lack of clear, pre-established processes for developing and adopting international instruments may cause additional uncertainties, including for IOs themselves, due to reduced visibility and predictability of successive steps in the process.

The variety of terminology used and approaches followed also results in differences in legal effects, and corresponding uncertainty for members as to what process applies to their use, adoption and potential transposition in national jurisdictions. Treaties and conventions typically follow a well-established procedure of signature, ratification and entry into force, envisaged in particular in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (UN, 1969[31]). On the other hand, whether a treaty automatically becomes domestically binding once it has come into force internationally, or whether domestic transposing legislation is required, is a matter of varying national laws. The process is much less clear for other international instruments, particularly those that are voluntary such as policy instruments, incentive instruments, international technical standards and supporting instruments. The results of a survey across OECD Members recently confirmed that the majority do not have a standardised approach to incorporating international instruments, which are not treaties or conventions, into domestic legislation (OECD, 2018[32]).

IOs efforts to bring more clarity into the international normative landscape

IOs are increasing their efforts to provide greater clarity on the types of instruments they issue and their relevant rulemaking processes to their membership, as well as to the general public. These include general databases on all their instruments made available in a single source to facilitate easy access to their normative framework (Box 1.3). Some IOs also provide information on the status of legal instruments, thus supporting the overall predictability of the international normative framework (Box 1.3).

IOs have also put in place different procedures to help foster coherence within their overall normative framework. Some IOs have developed procedures that apply across the corpus of instruments (e.g. IEC), while others have specific coherence mechanisms in place (e.g. IFAC, IUCN). A few IOs prescribe a specific duration for the development and adoption of international instruments, beyond which a formal request must be submitted (e.g. ILO, Box 1.3). This encourages the time-efficient development of IOs’ instruments.

The variety of rulemaking processes and what has long appeared as strict normative frameworks have demonstrated flexibility in the context of COVID-19. The exchange of experiences among IOs, in particular within a series of webinars on COVID-19 and international rulemaking, have underlined the shared challenges faced despite different governance structures and procedures and highlighted the benefits of mutual learning for improving the flexibility and resilience of international rulemaking (OECD, 2019[2]). IOs typically operate under strict normative frameworks which set long-term mandates and are enabled by governance modalities and decision–making practices that are heavily reliant on face-to-face interactions among different actors. These interactions and procedures were heavily impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic, with lockdown measures and travel restrictions.

Ensuring continuity of normative activities became one of the key challenges faced by IOs during the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2020[33]). While few organisations had pre-existing experience in remote decision-making, most IOs managed to rely on their existing normative frameworks to pivot to remote operations and adapt their rulemaking procedures (Box 1.5). The digitalisation of some IOs’ rulemaking activities is likely to remain in place after the crisis. Going forward, IOs would benefit from intensified efforts to ensure that their frameworks and rules of procedure are suitable for remote operations, including normative activities, and to tap into the potential of these changes to improve their rulemaking practices.

Box 1.3. Examples of online databases of international instruments

The International Bureau for Weights and Measures (BIPM)1 website (BIPM, 2021[34]) includes official (e.g. Metre Convention, Concession Convention, and Headquarters Agreement) and explanatory texts (e.g. Compendium and Notes), available in English and French. Resolutions of the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM), Decisions and Recommendations of the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM), “international technical standards” (the International System of Units, SI and Coordinated Universal Time, UTC), CIPM MRA (Mutual Recognition Arrangement), related documents and BIPM key comparison database (KCDB), guides in metrology (International Vocabulary of Metrology, VIM and Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement, GUM) maintained and promoted by the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM), an authoritative listing of available higher-order reference materials, measurement procedures and measurement laboratories maintained by the Joint Committee for Traceability in Laboratory Medicine (JCTLM), and Joint Declarations, MoUs and agreements with liaison partners.

The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) Handbook of International Public Sector Accounting Announcements (IFAC, 2021[35]) constitutes an annual report, freely and publicly available on the organisation’s website, which contains the body of standards produced by the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB). The most recent edition is provided in English and Spanish and contains a Conceptual Framework for General Purpose Financial Reporting by Public Sector Entities.

The International Laboratory Accreditation Cooperation (ILAC) publishes on its website (ILAC, 2020[36]) requirements for Members, guidance and promotional materials for stakeholders and communiqués and MoUs with liaison partners.

The IUCN Resolutions and Recommendations database (IUCN, 2020[12]) provides a platform for any IUCN constituent to report on activities that they have undertaken towards the implementation of a resolution or recommendation adopted by the Membership. Each resolution and recommendation from the most recent World Conservation Congress is assigned a Secretariat focal point to synthesise all of the activities being carried out across the Union. Users can search for IUCN instruments by code, title, type, the Congress and General Assembly in which it was adopted, geographic scope, and individual country status.

The Compendium of OECD Legal Instruments (OECD, 2020[37]) provides the texts of all the legal instruments developed within the framework of the OECD since 1961 – including abrogated instruments – together with information on the process for their development and implementation as well as non-Member adherence. A downloadable booklet gathering this information is also available for each instrument. The Compendium is available to the general public and maintained by the OECD Directorate for Legal Affairs.

The full body of OIML publications, including International Recommendations, International Documents, Vocabularies and other relevant publications, are available without charge on the OIML website (OIML, 2020[14]). Current and superseded versions of publications are available in English and, in most cases, in French. The online interface also provides a brief definition of the type and purpose of each international instrument developed by the organisation. Other language translations (OIML, 2020[38]) submitted by OIML Member States or Corresponding Members, are also made available – to date, this includes Arabic, Chinese, German, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Serbian, Spanish and Ukrainian. Prior to becoming an official OIML publication, various drafts are also made available online.

The SIECA website (SIECA, 2020[39]) includes all the legal instruments of the Central American Economic Integration Process. These are distinguished by the type of instrument (Treaties, Administrative Acts, Resolutions), as well as those currently in the process of development. Each section contains a brief description of the type of instrument, its function and its adoption procedure. There are both English and Spanish interfaces, but the legal texts are available only in the latter.

The United Nations (UN) Treaty Collection web page (UN, 2020[40]) provides access to all international treaties deposited with the United Nations Secretary-General, searchable by theme and with information on the status of the treaties’ signature and ratification. It also offers guidance and model instruments to help countries in their process to ratify, accept, approve, or submit reservations or declarations to such treaties .

The UNCITRAL both promulgates and publishes its texts for free download, provides consolidated and updated overviews of their use at the national level, and offers general and subject-specific guidance on their adoption, use and interpretation (UNCITRAL, 2020[41]). Publications are available in the six UN official languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish). Through the Case Law on UNCITRAL Texts (CLOUT) Database (UNCITRAL, 2020[42]), the Secretariat has also established a system for collecting and disseminating information – generally, case law abstracts and full-text judgments – on court decisions and arbitral awards interpreting UNCITRAL’s legal texts – including Conventions and Model Laws.

The Status of WTO Legal Instruments (WTO, 2020[43]) publication provides a regular, consolidated, and digitally-accessible overview of key developments in relation to the treaty instruments of the organisation. The current edition includes information on WTO accessions, treaty amendments, certifications and procès-verbaux relating to WTO Members' goods, services, and GPA schedules since the previous edition was issued in 2015.

1. Bureau international des poids et mesures (BIPM).

Source: Author’s elaboration based on IO practice templates and 2018 IO Survey.

Box 1.4. Procedures fostering coherence within IOs: examples

Pursuant to Article 10.6.1 – Coordination with Other Committees within the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM International) Regulations (ASTM International, 2020[44]), committees are instructed to maintain liaison representation and co-operation with other committees when mutual interests or potential conflicts exist. Upon request, committees shall also provide reviews of their standards to related or interested committees or those with particular expertise on certain sections of standards.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Secretariat has a mandate to update cross-references between existing texts following each Conference of the Parties (COP) (CITES, 2012[45]). If substantive changes are required, there are procedures through which the Secretariat can bring these to the attention of the Parties – either to the relevant Standing Committee or to the COP, depending on the content involved.

The Standardization Management Board (SMB) (IEC, 2020[46]) of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) issues horizontal standards to ensure coherence across the corpus of standardisation documents and avoid duplication or contradictory requirements.

IFAC has developed both structure and content requirements that should be followed when developing agreements and standards. Moreover, a periodic post-implementation review of standards (IFAC, 2013[47]) and a structural revision are undertaken by the independent Standard-Setting Boards (SSBs) in order to foster coherence.

The IUCN has put in place mechanisms in order to ensure coherence between the same types of instruments over time. For resolutions and recommendations, when motions for developing such instruments are submitted, Members need to determine whether there are already recommendations or resolutions covering the proposed item in order not to double the work. Over the years, Members have adopted a number of important resolutions that contribute to ensuring coherence, including one that stipulates that in cases of incoherence the last adopted instrument prevails. Moreover, in 2016 IUCN Members have adopted Resolution WCC/2016/Res/001 (IUCN, 2016[48]) which put in place a mechanism, according to which the IUCN Council has to review all existing resolutions and recommendations adopted since 1948 and retire such instruments that have already been implemented, have become obsolete, elapsed or superseded. This ensures coherence across all existing resolutions/recommendations adopted over time.

Within the ILO framework, a prescribed duration has been established for the development and adoption of the organisation’s instruments. This duration should be respected, but some flexibility is provided. When developing a project, committees have to inform the central secretariat on whether the project will take 18, 24, 36 or 48 months. With the exception of the 48-month track, if any project goes beyond the established period, it will be moved to the next track. If a project requires more than 48 months to be developed then a formal extension request is submitted by the committee. The Technical Management Board may choose to approve or deny the extension request. Committees are encouraged to stick to the timeframes they establish.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on IO practice templates, 2018 IO Survey and inputs from IOs.

Box 1.5. Pivoting to remote decision-making during the COVID-19 crisis

Before the COVID-19 crisis, only a few IOs had advanced experience with remote decision-making. These were typically IOs with large memberships that deploy virtual decision-making to facilitate participation. For example, ASTM International relies on a set of online tools to enable the participation of over 30 000 members in the standard-setting activities of 148 technical committees, including virtual balloting mechanisms. Similarly, standard-setting activities carried-out by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) offer the possibility to cast votes by correspondence using an online balloting system and to take part in meetings via WebEx. The online balloting system is a key resource for facilitating decision-making in ISO and fostering the most widespread participation possible.

Facing the COVID-19 crisis, IOs largely succeeded in shifting to virtual operations. At times, this shift required IOs to rely on new instruments to complement their constitutive text and/or rules of procedure. For instance, the OECD developed guidance to clarify procedural aspects around virtual rulemaking, and the Organisation for International Carriage by Rail (OTIF) consulted with its constituents and relied on a written procedure to make necessary adjustments, including the modification of annexes to its convention. Overall, the rulemaking work of technical committees proved easier to adjust to a virtual environment than that of governing bodies. Notably, only a small fraction of the normative activities of technical committees and governing bodies was postponed.

IOs also manage to hold large events key to the global response to the pandemic. In May and November 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) held virtual sessions of the Seventy-third World Health Assembly (WHA) and 147th session of the Executive Board as well as a special session of the Executive Board– WHO’s governing bodies at the global level. Held over two days to accommodate global participation, the May session of the WHA focused on the COVID-19 pandemic response as well as on matters required to ensure governance continuity. The session allowed, inter alia, the adoption of a Resolution on the COVID-19 Response.

References

[7] Abbott, K., C. Kauffmann and J. Lee (2018), “The contribution of trans-governmental networks of regulators to international regulatory co-operation”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 10, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/538ff99b-en.

[8] APEC (2020), About Us, https://www.apec.org/About-Us/About-APEC.

[44] ASTM International (2020), ASTM Regulations Governing Technical Committees | Green Book, https://www.astm.org/Regulations.html#s10.

[34] BIPM (2021), About the BIPM, https://www.bipm.org/en/about-us/ (accessed on 4 December 2020).

[45] CITES (2012), Submission of Draft Resolutions, Draft Decisions and other Documents for Meetings of the Conference of the Parties, https://www.cites.org/sites/default/files/document/E-Res-04-06-R18.pdf.

[3] Combacau, J. and S. Sur (2016), Droit international public, LGDJ-Lextenso, https://www.lgdj.fr/droit-international-public-9782275045092.html (accessed on 12 September 2018).

[9] COMESA (2000), Treaty Establishing the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), https://www.comesa.int/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Comesa-Treaty.pdf.

[21] CRS, I. (2020), OECD, https://www.oecd.org/tax/automatic-exchange/international-framework-for-the-crs/.

[46] IEC (2020), Standardization Management Board (SMB), https://www.iec.ch/dyn/www/f?p=103:59:0::::FSP_ORG_ID,FSP_LANG_ID:3228,25.

[35] IFAC (2021), Handbook of International Public Sector Accounting Announcements, https://www.ipsasb.org/publications/2021-handbook-international-public-sector-accounting-pronouncements.

[47] IFAC (2013), The Clarified ISAs - Findings from the Post-Implementation Review, https://www.iaasb.org/publications/clarified-isas-findings-post-implementation-review.

[36] ILAC (2020), Publications and Resources, https://ilac.org/publications-and-resources/.

[10] ILO (2020), Recommendations, https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12010:::NO:::.

[11] IOSCO (2018), Recommendations for Liquidity Risk Management for Collective Investment Schemes Final Report, https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD590.pdf.

[28] ITU (1995), Radio Regulations, https://www.itu.int/pub/R-REG-RR.

[12] IUCN (2020), IUCN Resolutions and Recommendations Database, https://portals.iucn.org/library/resrec/search?field_resrec_all_codes_value=&field_resrec_all_titles_value=&field_resrec_type_value=rec&field_resrec_status_value=1&sort_by=title&sort_order=ASC.

[48] IUCN (2016), Identifying and Archiving Resolutions and Recommendations to Strengthen IUCN Policy and to Enhance Implementation of IUCN Resolutions, https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/resrecfiles/WCC_2016_RES_001_EN.pdf.

[20] OECD (2020), Action 13 - OECD BEPS, https://www.oecd.org/tax/automatic-exchange/about-automatic-exchange/country-by-country-reporting.htm.

[37] OECD (2020), Compendium of OECD Legal Instruments, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/.

[33] OECD (2020), International organisations in the context of COVID-19: adapting rulemaking for timely, evidence-based and effective international solutions in a global crisis, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/Summary-Regulatory-management-Covid-19.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020).

[13] OECD (2020), OECD Legal Instruments, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/general-information.

[30] OECD (2020), Review of International Regulatory Co-operation of the United Kingdom, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/09be52f0-en.

[2] OECD (2019), The Contribution of International Organisations to a Rule-Based International System: Key Results from the Partnership of International Organisations for Effective Rulemaking, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/IO-Rule-Based%20System.pdf.

[5] OECD (2018), “Fostering better rules through international regulatory co-operation”, in OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-9-en.

[32] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[29] OECD (2018), Review of International Regulatory Co-operation of Mexico, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264305748-en.

[1] OECD (2016), International Regulatory Co-operation: The Role of International Organisations in Fostering Better Rules of Globalisation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264244047-en.

[4] OECD (2013), International Regulatory Co-operation: Addressing Global Challenges, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264200463-en.

[19] OECD (2011), The Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/the-multilateral-convention-on-mutual-administrative-assistance-in-tax-matters_9789264115606-en#page1.

[25] OECD (2009), Recommendation for Further Combating Bribery of Public Officials in International Business Transactions, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/corruption/anti-bribery/OECD-Anti-Bribery-Recommendation-ENG.pdf.

[24] OECD (1997), Convention on Combatting Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/ConvCombatBribery_ENG.pdf.

[49] OECD/ISO (2016), The Case of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/ISO_Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2019).

[6] OECD/WTO (2019), Facilitating Trade through Regulatory Cooperation: The Case of the WTO’s TBT/SPS Agreements and Committees, OECD Publishing, Paris/World Trade Organization, Geneva, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ad3c655f-en.

[22] OECD; UNECE (2016), International regulatory Co-operation and International Organisations: The Case of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/irc.htm (accessed on 28 April 2020).

[14] OIML (2020), Introduction to OIML Publications — English, https://www.oiml.org/en/publications/introduction.

[38] OIML (2020), Other Language Translations — English, https://www.oiml.org/en/publications/other-language-translations.

[27] SIECA (2020), Actos Administrativos, https://www.sieca.int/index.php/integracion-economica/instrumentos-juridicos/actos-administrativos/.

[39] SIECA (2020), Legal Instruments, https://www.sieca.int/index.php/economic-integration/legal-instruments/?lang=en.

[26] SIECA (2020), Tratados Internacionales, https://www.sieca.int/index.php/integracion-economica/instrumentos-juridicos/tratados-internacionales/.

[15] SIECA (1993), Guatemala Protocol, http://www.sice.oas.org/trade/sica/pdf/prot.guatemala93.pdf.

[40] UN (2020), United Nations Treaty Collection, https://treaties.un.org/Pages/Content.aspx?path=Publication/ModelInstruments/Page1_en.xml.

[31] UN (1969), Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

[42] UNCITRAL (2020), Case Law on UNCITRAL Texts (CLOUT) Database, https://www.uncitral.org/clout/.

[41] UNCITRAL (2020), Texts and Status, https://uncitral.un.org/en/texts.

[23] UNECE (1979), Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP), http://www.unece.org/fileadmin//DAM/env/lrtap/lrtap_h1.htm.

[16] UNFCCC (2016), Summary and Recommendations by the Standing Committee on Finance on the 2016 Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows 1, https://unfccc.int/files/cooperation_and_support/financial_mechanism/standing_committee/application/pdf/2016_ba_summary_and_recommendations.pdf.

[17] WIPO (2020), List of WIPO Standards, Recommendations and Guidelines, https://www.wipo.int/standards/en/part_03_standards.html.

[18] WIPO (2007), The 45 Adopted Recommendations under the WIPO Development Agenda, https://www.wipo.int/ip-development/en/agenda/recommendations.html.

[43] WTO (2020), Status of WTO Legal Instruments, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/wto_legal_instruments_e.htm.

Notes

← 1. What this report refers to as “international technical standards” for descriptive purposes are sometimes referred to as “international standards” by some IOs, though not all. For example, in the context of the World Trade Organisation, to provide some guidance on the term, the Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade has adopted a Decision which sets out six principles for the development of international standards, including: i) transparency; ii) openness; iii) impartiality and consensus; iv) effectiveness and relevance; v) coherence; and vi) the development dimension. In addition, WTO case-law provides some guidance. According to such case law, for an instrument to be considered an “international standard” under the TBT Agreement it must both: constitute a “standard” (i.e. a document approved by a recognised body, that provides, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines or characteristics for products or related processes and production methods, with which compliance is not mandatory) and be “international” in character, i.e. adopted by an international standardising body. (OECD/WTO, 2019[6]).

← 3. The figures are provided a for analytical purposes, and are not intended to create definitions.

← 4. Article 2 (a) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides the following definition: “ “treaty” means an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation.”

← 5. APEC, BIPM, CITES, ICRC, IEA (for communiqués, recommendations, joint statements), IFAC, ILAC, ILO, IOSCO, IUCN (for standard, best practice guidance, guidelines), OECD, OIE, OTIF,PIC/S, UNECE, UNFCCC, UNIDO, WCO, WMO.

← 6. IEA (for principles, best practice guidelines or best practices), IFRC (notably for the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent), IUCN (for the model treaties, declarations and principles).