A well designed and effectively enforced competition law can bring many benefits, such as lower prices, better quality products and services, more choices to consumers, and ultimately economic growth and development. To reap the benefits of competition, all competitors in a given market should be subject to the same competition rules. This chapter presents a set of questions to guide the analysis, good practices and examples on how to implement the OECD Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality in competition law and enforcement.

Competitive Neutrality Toolkit

3. Competition law and enforcement

Abstract

A well-designed and effectively enforced competition law can bring many benefits, including lower prices, better quality products and services, more choices to consumers, and ultimately economic growth and development (OECD, 2014[1]). In order for this to happen, all competitors in a given market should be subject to the same competition rules. Exceptions for some enterprises that are not subject to the application or enforcement of the competition law result in a non-neutral competition framework. In turn, an uneven playing field undercuts the benefits of competition (OECD, 2021, pp. 7-9[2]).

For these reasons, the Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality provides that jurisdictions should ensure competitive neutrality in their competition law and in its enforcement.

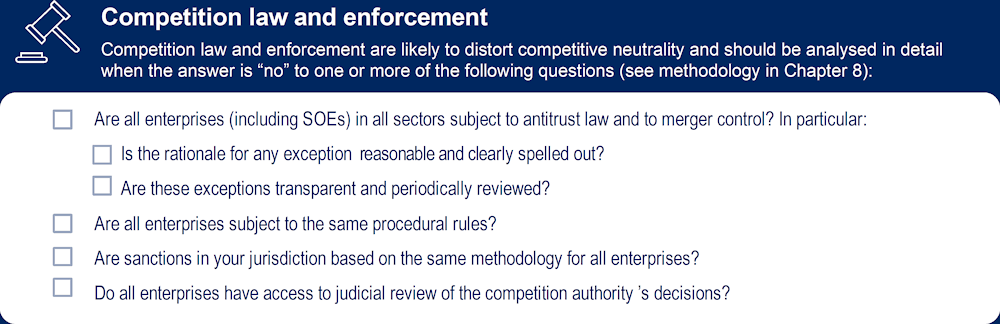

A set of questions to help identify policies that can potentially distort competitive neutrality is presented below. When a policy is not in line with at least one of the questions or good practice approaches, it has the potential to distort competition and should be analysed in detail. Chapter 8 sets out the main steps of the analysis.

Figure 3.1. Suggested questions to assess competition law and enforcement

3.1. Adopt or maintain, and enforce, a competitively neutral competition legal framework

According to the Recommendation, jurisdictions should “adopt or maintain, as appropriate, a competitively neutral competition law that addresses anti-competitive conduct and includes merger control”. This mostly concerns the question of who is subject to competition law. As stated in (OECD, 2015[3]), competition law normally applies “to any ‘person’ or ‘undertaking’, which are interpreted broadly as encompassing any entity engaged in an economic activity, regardless of its ownership, source of financing, legal status, place of business or nationality”.1

The Recommendation therefore recommends that jurisdictions make sure their competition rules are applied to all competitors in the same manner, so as not to distort the level playing field. However, there may be jurisdictions where competition law only applies to corporatised SOEs, while other types of public companies may not be subject to competition law even though they perform economic activities. Additionally, certain companies in charge of delivering public services may not be subject to competition law regardless of their ownership.

The Recommendation states the principle that jurisdictions should maintain competitive neutrality in the enforcement of competition law. It recognises that while rules may appear to be competitively neutral de jure, in practice their enforcement may be discriminatory, for example SOEs may enjoy a more favourable treatment in merger control or antitrust enforcement. The challenges of competition enforcement when dealing with SOEs have attracted significant attention. OECD (2015[3]) discusses substantive, institutional and practical challenges with enforcement. For example, it may not be straightforward to assess if various SOEs qualify as separate entities or not. This has various implications, such as whether co-ordinated practices among SOEs may amount to collusion or whether the concentration or two or more SOE undertakings is subject to merger control. On the institutional front, there is the risk of undue influence by the government on the competition authority, despite its independence, when an SOE is being investigated for competition law violations. There are also practical challenges with investigation and information gathering. For instance, government entities may be reluctant to respond to requests for information in some jurisdictions.

While competition law and its enforcement should be neutral, the Recommendation clarifies that this principle “would not rule out measures aimed at safeguarding competitive neutrality”. Therefore, the Recommendation allows for rules that may be applicable to certain types of enterprises, such as SOEs, to achieve competitive neutrality. Some jurisdictions have specific legal frameworks and powers designed to promote competitive neutrality (see Box 3.1).

The principle of competitive neutrality in competition enforcement is also encapsulated in the Recommendation on Transparency and Procedural Fairness [OECD/LEGAL/0465], which sets standards concerning impartial and non-discriminatory competition law enforcement. In particular, it calls for jurisdictions to carry out “competition law enforcement in a reasonable, consistent and non-discriminatory manner, including without prejudice to the nationalities and ownership of parties under investigation”.

Examples

The following selected examples are meant to show that SOEs are subject to competition law in the majority of jurisdictions:

In 2008, the Chilean Competition Tribunal (TDLC) found that the state-owned Chilean Railway Company abused its dominant position by charging excessive prices. The company was ordered to change its pricing and avoid arbitrary discrimination.2 This case clarified that the tribunal “can impose sanctions against the State when: (a) it acts as an economic agent, and (b) acts against the Competition Law” (OECD, 2015, p. 3[4]). This decision was confirmed by the Chilean Supreme Court in 2009.3

In 2015, the European Commission imposed fines on two subsidiaries of the Austrian and German railway incumbents (SOEs Österreichische Bundesbahnen and Schenker, respectively), for fixing prices, allocating customers, as well as exchanging information for nearly eight years. Swiss Kühne+Nagel, privately-owned, was also part of this agreement, but was not fined under the EU’s leniency program (OECD, 2016, p. 105[5]).4

In 2007, the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) enforced a case against a subsidiary of an SOE in the telecom industry. The undertaking had been setting prices for end-users in the downstream market that were lower than prices for its competitors in the upstream market, foreclosing its competitors, i.e. other telecom providers, from the downstream market (OECD, 2015, p. 3[6]).

In 2016, the Norwegian Competition Authority imposed fines on Lindum AS, a company 100% owned by the municipality of Drammen, and a private firm for illegal collusion by submitting a joint bid for the collection, transport and final treatment of sewage sludge in Bergen municipality (Norwegian Competition Authority, 2016[7]).

In 2008, the Office for Fair Trading (OFT), one of the predecessors of the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), issued a decision against publicly-owned bus company Cardiff Bus for engaging in predatory behaviour designed to eliminate a competitor (OECD, 2015, p. 5[8]).

Box 3.1. Jurisdictions with a legal framework or specific provisions on competitive neutrality

Australia has a comprehensive framework for promoting competitive neutrality between government-owned enterprises and private enterprises. Both the federal and state governments have established competitive neutrality policies and guidelines to ensure that the government’s acts and decisions do not benefit its own businesses over the private sector. When a government-owned business benefits from more favourable conditions than private enterprises, for instance lower borrowing rates, the Australian policy provides for a “neutrality adjustment” to balance this advantage. Complaints against violations of federal rules are handled by the Australian Government Competitive Neutrality Complaints Office (AGCNCO).

The Finnish Competition Act (Section 30a) gives the Finnish Competition and Consumer Authority (FCCA) the power to intervene in markets where public entities engage in business activities if a business practice or organisational structure prevents or distorts competition on the market or conflicts with the requirement of market-based pricing in the Local Government Act. The FCCA shall first strive to abolish the distortion of competition through negotiations. If this approach does not succeed, the FCCA shall prohibit the use of the business practice or organisational structure, or impose conditions to ensure neutral competitive neutrality in the market.

The Lithuanian Competition Act (Article 4) provides that public administration entities should not grant privileges to or discriminate in favour of undertakings that distort competition, except “where the different competitive conditions may not be avoided when meeting the requirements of the parliamentary laws”. The Competition Council of Lithuania has enforcement powers against public authorities’ decisions that result in a differential treatment of competitors, whether they are state-owned enterprises or privately-owned enterprises.

The Swedish Competition Act (Chapter 3, Section 27) prohibits anti-competitive sales activities by public entities. The Competition Authority can investigate conduct falling under this provision and ask the Patent and Market Court to issue a decision prohibiting “conduct by the state, a municipality or a county council within a sales activity if the conduct distorts […] the conditions for effective competition in the market”. As opposed to the general antitrust rules on unilateral conduct, this provision does not require the entity conducting the sales activity to be dominant.

Sources: OECD (2015[9]), OECD Roundtable on Competitive Neutrality in Competition in Competition Enforcement – Note https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2015)19/En/pdf; OECD (2021[10]), OECD Roundtable on the Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities – Note by Finland, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)41/en/pdf; OECD (2021[11]), OECD Roundtable on the Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities – Note by Lithuania, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)32/en/pdf.

3.2. Restrict exceptions, if any, from the coverage of competition laws to those indispensable to achieve their overriding policy objectives

Despite the overarching principle that competition law and its enforcement should be competitively neutral, some jurisdictions may still grant exceptions to certain enterprises, such as large employers or national champions. These exceptions reduce the scope of competition law and may result in anti-competitive conduct not being sanctioned by the authorities. In addition, the exempted enterprises benefit from a more lenient framework than their competitors and have lower competition law compliance costs. For these reasons, legal exceptions should be limited. However, a number of jurisdictions still grant exceptions to specific entities. For instance, in some jurisdictions the competition act gives a minister the power to exempt a specific business or activity from competition law. Moreover, as described in Section 3.6, there may be provisions that enable the government to intervene in merger control in view of public interest considerations (OECD, 2016[12]), effectively introducing an exception from competitive neutrality principles.

For competition law to be neutral, any exceptions should be limited to those that are indispensable to achieve a country’s overriding policy objectives, as outlined in the Recommendation on Hard Core Cartels [OECD/LEGAL/0452] and the Recommendation on Competition Assessment [OECD/LEGAL/0455]. The former calls on jurisdictions to “restrict exemptions, if any, from the coverage of Adherents’ laws against hard core cartels to those indispensable to achieve their overriding policy objectives”. The latter calls for exceptions to be “no broader than necessary to achieve their public interest objectives and that these […] are interpreted narrowly”.

Examples

The following are examples showing criteria adopted by selected jurisdictions to identify exceptions needed to achieve specific public objectives:

In Colombia, Article 28 of the Competition Law established that “restrictive competition practices and particularly those relating to the control of merger transactions” do not apply to cases when the Superintendence of Finance, the financial regulator that oversees competition law in the financial sector, imposes “mechanisms designed to rescue and protect the public trust”. In particular, the competition law defines these mechanisms narrowly as those deemed necessary for maintaining public confidence in the financial system (OECD, 2016, p. 90[13]).

In EU and EEA member states, there are no exceptions from competition rules. There is certain room for limiting their application though. Undertakings providing services of general economic interest (SGEI), as per Article 106(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), are subject to competition law to the extent that it does not “obstruct the performance […] of the particular tasks assigned to them”. This holds for both public and private undertakings, and it is applied very narrowly and to ensure specific strategic interests (OECD, 2012, pp. 19, 71[14]).

In a 2006 case, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held that the Tennessee Valley Authority, a large public power provider, was entitled to an implied exemption from anti-trust laws for certain conduct. This was in light of a federal statute that expressly authorised it to enter into contracts for the purpose of “promot[ing] the wider and better use of electric power for agricultural and domestic use, or for small or local industries” (OECD, 2015, p. 5[15]).5 In this case, the exemption was directly related to a specific public policy objective.

3.3. Any legal exceptions from competition law should be adopted through a formal legislative process and should periodically be subject to a formal competition assessment process

The good practices identified show that exceptions from competition law, if any, should be widely discussed through a formal legislative process. This helps ensure that exceptions are adopted in a transparent way and are publicly known, as well as allows for open discussion on the merits of the exceptions, and for objections and alternative proposals to be put forward and considered. In addition, those legal exceptions should be reviewed periodically through a formal competition assessment process following transparent criteria for evaluating suitable alternatives. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, in some jurisdictions the government can exempt specific companies from competition law without a legislative process and without defining a clear policy objective to justify the exception.

These good practices, i.e. transparency and regular review, are in line with the OECD Recommendation on Effective Action against Hard Core Cartels [OECD/LEGAL/0452] and the OECD Recommendation on Competition Assessment [OECD/LEGAL/0455]. The former provides that jurisdictions “should make their exemptions transparent and periodically assess their exemptions to determine whether they are necessary and limited to achieving their objective”. The latter recommends that any new exemptions from competition law be “defined for a limited period of time, typically by including a sunset date, so that no exception would persist when it is no longer necessary to achieve the identified policy objective”.

Examples

The following are selected examples where exceptions are transparently granted by law or where they are being assessed:

In Costa Rica, the competition act grants exceptions to certain entities, such as some concessionaries of public services and monopolies awarded by the State. In a recent review, the OECD recommended their periodic assessment to evaluate if those exceptions continued to be justified, noting that the competition authority had already advocated for repealing some of them in the past (OECD, 2020[16]).

In Israel, restrictive agreements can be exempt from competition law if they are established by law (not by mere policy or administrative decisions), and only if the application of competition rules would otherwise create an irresolvable conflict with the legislation in question (OECD, 2011, p. 76[17]).

Japan, through the Antimonopoly Act and other pieces of legislation, had previously granted many exceptions in different industries in order to develop and strengthen these industries. However, the Japan Fair Trade Commission, in co-operation with different relevant ministries, is now reviewing these exceptions to see if they are still necessary. In 2021, there were 25 exceptions in 18 laws, which have been reduced from 89 exceptions in 30 pieces of legislation in 1996 (OECD, 2021, p. 3[18]).

In a case between the US Postal Service (USPS) and Flamingo Industries, a supplier of mail sacks, the latter claimed that the former purposefully excluded it from the market for providing mail sacks. The Supreme Court held that USPS was not subject to antitrust liability, as it was considered part of the federal government and was hence not subject to antitrust laws.6 In later years, Congress opened some postal services to competition from private entities and provided that regarding these services, the US Postal Service is subject to federal antitrust laws as are its privately-owned competitors (OECD, 2015, p. 4[15]).

3.4. There should be no defences that are available to an enterprise based on criteria such as its ownership, nationality or legal form but denied to other enterprises

Competition law may not apply in a neutral way because certain enterprises benefit from exceptions, as seen in Sections 3.2 and 3.3. Moreover, enterprises that are subject to competition law could claim defences against its enforcement. These are claims raised by antitrust defendants in order to prove that even if competition law is applicable, it should not be enforced in that case (OECD, 2021[2]).

An example is the state action defence or regulated conduct defence, which shields conduct from competition law enforcement when it is required or authorised by law. There is a risk that SOEs or enterprises in strategic sectors may find it easier than their competitors to justify their actions as being directed or authorised by the State. This concern is mitigated by the fact that enterprises invoking this defence must provide, in the jurisdictions where it is admitted, substantial evidence to show that their actions were required or authorised by law (OECD, 2018[19]).

In order to ensure competitive neutrality in the enforcement of competition law, good practices among jurisdictions show that legal provisions that make defences available only to certain enterprises should be avoided. Specific criteria may help clarify the circumstances under which certain defences can be claimed.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In 2018, the Chinese State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) found two undertakings, associated with Chinese SOEs, were in violation of competition laws for price-fixing in the market for freight shipping. While the parties argued that they formed a single entity, SAMR found that they operated independently. The parties also argued that their pricing strategies were directed by the state. SAMR also disagreed with this view, noting that even in the presence of government intervention, competing undertakings should not collude (OECD, 2018, p. 10[19]). The single entity defence can be invoked by all enterprises.

In Israel, competition law does not apply to conduct if it is part of a governmental directive, leaving “no latitude for individual choice” for the undertaking. This holds for any undertakings (OECD, 2011, p. 76[17]).

Though disfavoured, US states may, under narrow circumstances, regulate their economies by adopting measures that shield anticompetitive conduct from the reach of the federal antitrust laws. A state acting in its sovereign capacity may impose restrictions on competition, confer exclusive or shared rights to dominate a market, or otherwise limit competition to achieve public objectives. Private actors, including state regulatory boards controlled by market participants, are exempt from antitrust liability if acting pursuant to a clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed state policy and if their actions are actively supervised by the state, including by a state official or state agency that is not a participant in the market being regulated. The first element seeks to ensure that the anticompetitive mechanisms adopted by the governmental entity operate because of a deliberate and intended state policy. The second element, active state supervision, ensures that entities that include active market participants are acting pursuant to a state policy rather than their private interests in restricting competition. For regulatory boards controlled by market participants, the state must review the substantive merits of particular acts to ensure consistency with state goals. Although the US Supreme Court has addressed aspects of the “state action defence” in a number of cases, most recently in North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC, the Supreme Court clarified when actions by a state regulatory board that includes active market participants satisfy this defence. In this case, the North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners (NC Board) was a state agency responsible for administering and enforcing a licensing system for dentists. The challenged competitive restraint was a rule prohibiting non-dentists from providing teeth whitening services in competition with licensed dentists. Significantly, a majority of the NC Board’s decisionmakers were practicing dentists, and, thus, they had a private incentive to limit competition from non-dentist providers of teeth whitening services. The NC Board invoked the state action defence, asserting that the prohibition did not violate the antitrust laws because the NC Board was a state agency. The Supreme Court rejected this argument, holding that the NC Board’s actions required active supervision by the state because a majority of the NC Board’s members were active participants in the market it was regulating (OECD, 2015, pp. 6-10[15]).7

3.5. Sanctions should not discriminate between enterprises based on criteria such as ownership, nationality or legal form

Sanctions, including monetary penalties, are an integral part of competition law frameworks to ensure deterrence. Even though many jurisdictions have guidelines in place for transparency purposes, there is still wide discretion in the sanctions (and in particular fines) that authorities and courts can set (OECD, 2018[20]). In turn, this discretion could result in discriminatory treatment of competitors. Sanctions should be set following the same criteria for any type of entity conducting an economic activity. Guidelines issued by competition authorities, if any, should not discriminate between different competitors. In some jurisdictions, courts rather than competition authorities determine sanctions for certain anti-competitive conducts. In those cases, it is possible that the relevant guidelines will not be specific to competition cases but will apply more generally. Even when not issued by the competition authority, any guidelines should still be in line with the principle of competitive neutrality.

For example, SOEs should have the same treatment as private entities. Determining the appropriate sanction or remedy for an anti-competitive behaviour of an SOE is important to ensure an effective degree of deterrence (OECD, 2021[2]). However, there may be some implementation challenges that are especially relevant when dealing with SOEs, for example concerning the identification of the relevant turnover to calculate fines, due to the different financial standards applicable to SOEs that may provide less transparency than for privately-owned enterprises.8 Another issue concerns the deterrence effect of financial penalties if SOEs benefit from State transfers and can pass fines on to taxpayers. Some of these factors will likely depend on wider country policies and set-up rather than the competition law itself or the competition authority’s fining guidelines.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach, in particular in relation to the treatment of SOEs:

In 2016, the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (CADE) sanctioned an international cartel in the market of compressors used in refrigeration, involving both domestic and foreign companies. The fines imposed by CADE amounted to BRL 21 million and all firms were sanctioned on the same criteria (OECD, 2017[21]).

In 2013, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) imposed a fine on an SOE, Coal India Limited, for imposing discriminatory conditions in its fuel supply agreements (OECD, 2021, p. 5[22]).9 In another case, the CCI found that four public sector general insurance companies had formed a cartel to increase the premium for a subscriber.10 The four undertakings were fined. Similarly, in 2021, the CCI found an SOE to have abused its dominant position in the milling market and ordered it to cease and desist its actions (OECD, 2021, p. 6[22]).11

Following an investigation for discriminatory practices and margin squeeze, in 2013 the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM) imposed commitments on the state-owned incumbent in the market for high-speed passenger rail transport services. The state-owned incumbent did not abide by these commitments, leading to another investigation by the AGCM in 2015 (OECD, 2018, p. 17[19]).12

The Commission for the Protection of Competition of Serbia has enforced competition rules against SOEs multiple times, mainly concerning abuse of dominance in the energy, railways, and telecommunications sectors. In general, the Commission “does not distinguish between SOEs and other firms when applying rules concerning restrictive agreements, abuse of dominance and merger control to firms in all sectors of the economy” (OECD, 2021, p. 3[23]).

In a Swedish bid-rigging scheme among several construction firms, the Swedish Road Authority acted both as damaged procuring authority and supplier of asphalt that participated in the cartel. In 2009, the Swedish Market Court decided that a public authority carrying out multiple functions could be part of a cartel in its role as a supplier and be held accountable for the anti-competitive infringement. Thus, the Road Authority was sanctioned according to the same principles as the other cartel participants (Nilsson, 2009[24]).

In 2017, the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine (AMCU) fined state-owned Boryspil International Airport for abusing its position in the aircraft ground handling services by refusing to approve applications by other entrants (OECD, 2018, p. 21[19]).

3.6. Merger control frameworks should be competitively neutral, in particular with regard to establishing jurisdiction over transactions

Good practices show that merger control frameworks apply in a neutral manner to all entities conducting an economic activity, for instance regarding their ownership and nationality. In this respect, a number of challenges arise in the design and application of merger control rules. For example, assessing if the merging parties can be considered two separate economic entities may be more complicated in the case of SOEs than other competitors. This is due to difficulties in determining the extent to which extent the State is involved in decision-making and therefore can impose its decisions on both entities, which in this case would not be seen as separate. As a consequence, calculating the relevant turnover, in order to ascertain if a transaction has to be notified, can be challenging. If the corporate perimeter is incorrectly identified, transactions that do not require notification because the entities are already part of the same group will be reviewed or, conversely, some mergers may not be notified even though the parties were separate economic entities.

The challenge of identifying the correct boundaries of merging SOEs is also linked to the ownership and governance structure of SOEs. In some countries, a central state authority may be responsible for managing the State’s shareholdings. Therefore, when assessing mergers involving foreign SOEs, competition authorities need to understand the specificities of the country in order to investigate if the merging parties are independent or belong to a wider economic unit.

In addition, there is a risk that competition authorities are or feel pressed to analyse mergers involving foreign entities somewhat more strictly, especially when they involve state assets or so-called national champions.

The legal framework may set different requirements for different competitors or there may be calls for competition authorities to treat certain cases differently in their enforcement of the legal framework. As an example of the former, in an Adherent the ex-ante merger control regime has a specific exception in some sectors. Mergers, concessions, transfers or control changes by and among non-dominant economic agents are not subject to merger control if they comply with certain requirements provided in the law. Moreover, if the competition authority identifies competition concerns following a merger, non-dominant players may not be subject to divestment rules, and only regulation and behavioural remedies may be imposed by the competition authority.

Some transactions may take place in strategic sectors, involve national security considerations or other policy objectives such as preserving media plurality, regardless of whether the entities involved are SOEs or privately-owned, foreign or domestic companies. In these cases, the legal framework may provide for such considerations in the merger review process, either by the competition authority or, more frequently within Adherents, by another entity, often a government department. However, as discussed in the OECD Roundtable on Public Interest Considerations in Merger Control (OECD, 2016[12]), public interest clauses may result in lack of predictability and transparency. For these reasons, it is a good practice to make sure that “government intervention is exercised under exceptional circumstances and in a transparent manner; and that there is effective judicial review of how the merger-specific public interest concerns outweigh the drawbacks in competition” (OECD, 2016[25]). Finally, other tools may be more suitable to address non-competition related objectives, such as foreign direct investment (FDI) screening mechanisms, although such mechanisms can also distort competitive neutrality, for example if acquisitions by foreign players are discouraged for protectionist purposes.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In Brazil, the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (CADE) acts on the premise that competition law applies to all individuals in all sectors, meaning that SOEs are subject to merger control by CADE. Accordingly, CADE reviewed a transaction between two publicly controlled banks, and the transaction was cleared with remedies (OECD, 2015, p. 4[26]). CADE has also analysed mergers involving SOEs in the fuel sector. In one case, in 2007, it imposed both structural and behavioural remedies (OECD, 2015, p. 6[26]).13

The EU Merger Regulation applies to all types of undertakings. Its preamble, as well as Article 1, highlights that certain transactions have a “community dimension”, and thus are within the jurisdiction of the Commission, if they surpass certain turnover thresholds. These thresholds are calculated “with respect [to] the principle of non-discrimination between the public and private sectors … irrespective of the way in which the [undertakings’] capital is held or of the rules of administrative supervision applicable to them”.14

More specifically, the EU Merger Regulation (preamble 22) deals with the calculation of turnover in a concentration in the public sector, stating that it should “take account of undertakings making up an economic unit with an independent power of decision, irrespective of the way in which their capital is held or of the rules of administrative supervision applicable to them”. Therefore, under the Merger Regulation, the European Commission assesses if an SOE has an independent power of decision. If not, it will need to identify the ultimate State entity that controls that SOE, together with any other SOEs owned by the same State entity.

Such transactions can then be analysed by the Commission or can be referred to the competition authority of a Member State, if a preliminary analysis finds that assessment by the national competition authority would be more appropriate. For example, in 2009, the EC assessed a merger between GDF Suez and EDF, in both of which the French State held significant shareholding interest. The EC found some concerns with the merger and approved it subject to commitments, specifically a divestiture remedy.15 In 1998, the EC reviewed a merger between two Finnish SOEs operating in the energy sector, Neste and IVO, and approved it subject to commitments by both undertakings and by the Finnish government (OECD, 2016, p. 109[5]).16

The Hungarian Competition Act allows for exemptions for undertakings (mainly SOEs) from having to fulfil merger control clearance obligations if they are of national strategic importance and serve the public interest. This exemption has been applied in a number of cases, mainly in the public utilities sector (OECD, 2018, p. 8[19]). For instance, in the energy sector the exemption was used to facilitate affordable energy supply for consumers, and in the financial sector, with the goal of preserving jobs. These exemptions have been used to achieve clear and specific policy objectives and strategic goals (Eötvös and Christoph, 2016[27]).

In 2022, Mexico’s Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT) examined a merger involving a Private Public Partnership (PPP) created to supply wholesale services to retail telecommunications providers. The private partner of the PPP notified IFT that its shareholders and the Mexican Development Bank would set up a financial agreement, and the government would hold 60% of the assets. In its competition assessment, IFT analysed who would be the stakeholders and if they participate in the market, as well as the equity participation and stakeholders’ rights post-merger (IFT, 2022[28]).

In 2021, the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) applied competition rules to a foreign undertaking carrying out a merger under its jurisdiction, fining a Portuguese SOE for gun-jumping (OECD, 2021, p. 5[29]).17

References

[27] Eötvös, O. and H. Christoph (2016), “No merger control for concentrations of national strategic importance”, International Law Office, https://www.lexology.com/commentary/competition-antitrust/hungary/schoenherr-attorneys-at-law/no-merger-control-for-concentrations-of-national-strategic-importance.

[30] Fox, E. and D. Gerard (2023), EU Competition Law: Cases, Texts and Context, Edward Elgar Publishing, https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/eu-competition-law-9781839104688.html.

[28] IFT (2022), El Pleno del IFT autoriza concentración en Altán y emite opinión en competencia económica para modificar el contrato APP de la Red Compartida Mayorista. (Comunicado 60/2022) 21 de junio, https://www.ift.org.mx/comunicacion-y-medios/comunicados-ift/es/el-pleno-del-ift-autoriza-concentracion-en-altan-y-emite-opinion-en-competencia-economica-para.

[24] Nilsson, D. (2009), The Swedish Market Court ends asphalt cartel case by increasing fines up to € 46 M, reaching the highest ever fine in a cartel case (NCC), https://www.concurrences.com/en/bulletin/news-issues/may-2009/The-Swedish-Market-Court-ends.

[7] Norwegian Competition Authority (2016), Fined for collusive bidding, https://konkurransetilsynet.no/fined-for-collusive-bidding/?lang=en.

[31] OECD (2022), Monitoring the Performance of State-Owned Enterprises: Good Practice Guide for Annual Aggregate Reporting, http://www.oecd.org/corporate/monitoring-performance-state-owned-enterprises.htm (accessed on 12 May 2022).

[10] OECD (2021), OECD Roundtable on the Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities – Note by Finland, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)41/en/pdf.

[11] OECD (2021), OECD Roundtable on the Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities - Note by Lithuania, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)32/en/pdf.

[22] OECD (2021), Roundtable on The Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities - Note by India, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)28/en/pdf.

[23] OECD (2021), Roundtable on The promotion of competitive neutrality by competition authorities - Note by Serbia, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)33/en/pdf.

[2] OECD (2021), The Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities, Discussion Paper, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/the-promotion-of-competitive-neutrality-by-competition-authorities-2021.pdf.

[18] OECD (2021), The Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities, Note by Japan, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)20/en/pdf.

[29] OECD (2021), The Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities, Note by Spain, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)39/en/pdf.

[16] OECD (2020), Costa Rica: Assessment of Competition Law and Policy 2020, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/costa-rica-assessment-of-competition-law-and-policy2020.pdf.

[19] OECD (2018), Competition Law and State-Owned Enterprises, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF(2018)10/en/pdf.

[20] OECD (2018), Pecuniary Penalties for Competition Law Infringements in Australia, http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/pecuniary-penalties-competition-law-infringements-australia-2018.htm.

[21] OECD (2017), Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in Brazil - 2016, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/AR(2017)19/en/pdf.

[13] OECD (2016), Colombia: Assessment of Competition Law and Policy, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/Colombia-assessment-competition-report-2016.pdf.

[25] OECD (2016), Executive Summary of the Roundtable on Public Interest Considerations in Merger Control, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/public-interest-considerations-in-merger-control.htm.

[12] OECD (2016), Public interest considerations in merger control, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/public-interest-considerations-in-merger-control.htm.

[5] OECD (2016), State-Owned Enterprises as Global Competitors: A Challenge or an Opportunity?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264262096-en.

[3] OECD (2015), “Competition policy and competitive neutrality”, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2015)13/FINAL/en/pdf.

[8] OECD (2015), Discussion on Competitive Neutrality, Note by the Secretariat, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2015)8/FINAL/en/pdf.

[9] OECD (2015), OECD Roundtable on Competitive Neutrality in Competition Enforcement - Note by Australia, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2015)19/En/pdf.

[26] OECD (2015), Roundtable on Competitive Neutrality in Competition Enforcement, Note by Brazil, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2015)25/En/pdf.

[4] OECD (2015), Roundtable on Competitive Neutrality in Competition Enforcement, Note by Chile, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2015)40/En/pdf.

[6] OECD (2015), Roundtable on Competitive Neutrality in Competition Enforcement, Note by Japan, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2015)6/En/pdf.

[15] OECD (2015), Roundtable on Competitive Neutrality in Competition Enforcement, Note by the United States, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2015)42/En/pdf.

[1] OECD (2014), Factsheet on how competition affects macroeconomic outcomes, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/factsheet-macroeconomics-competition.htm.

[14] OECD (2012), Competitive Neutrality: National Practices, https://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/50250966.pdf.

[17] OECD (2011), Competition Law and Policy in Israel, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264097667-en.

Notes

← 1. An activity may broadly be considered of economic nature if it is carried out or can be carried out in a market by private undertakings. The interpretation can be left to court, as demonstrate by several EU cases that have contributed to clarifying the definition (Fox and Gerard, 2023, p. 28[30])

← 2. Decision 76/2008.

← 3. Case No. 6978-2008, decision of 13 January 2009.

← 4. European Commission Decision of 15.7.2015 CASE AT.40098 – Blocktrains.

← 5. McCarthy v. Middle Tennessee Electric Membership Corp., 466 F.3d 399, 414 (6th Cir. 2006).

← 6. US Postal Service v Flamingo Industries (USA), Ltd. (“Flamingo”) 540 US 736 (2004).

← 7. North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC case (574 U.S.2015, No. 13-534).

← 8. Work by the OECD Working Party on State Ownership and Privatisation Practices supports the improvement of transparency on the financial and non-financial performance of SOEs, for instance through (OECD, 2022[31]).

← 9. Maharashtra State Power Generation Company Ltd. v. Coal India Ltd. (Case No. 03, 11 & 59 of 2012).

← 10. National Insurance Company Ltd. v. CCI.

← 11. M/s MaaMetakani Rice Industries v. Odisha State Civil Supplies Corporation Ltd (Case No. 16 of 2019).

← 12. Autoritá Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato, Bollettino settimanale Anno XXIII.

← 13. AC 08012.002820/2007-93.

← 14. Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings, preamble 22.

← 15. Case No. COMP/M.5549 - EDF/ SEGEBEL.

← 16. Case No. IV/M.931 - NESTE / IVO.

← 17. SNC/DC/048/21: DGTF/PARPÚBLICA/TAP.