Although state support can have a sound rationale and achieve important policy objectives, it might distort competition in favour of certain enterprises. As a result of state support, some enterprises may have artificially lower costs or a stronger financial position than their competitors. The competitors that gain market shares and are more successful would therefore be those that gain privileges instead of those that offer better value to consumers. This chapter presents a set of questions to guide the analysis, good practices and examples on how to implement the OECD Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality in state support.

Competitive Neutrality Toolkit

6. State support

Abstract

State support can take many forms, including direct cash injections, loans granted at more favourable terms or conditions, or tax incentives. It can be disbursed directly by the state, or can flow indirectly to beneficiaries, for instance through state-owned banks (OECD, 2021[1]) or state energy companies (OECD, 2023[2]). As discussed in Chapter 2, state support has a variety of objectives, for instance to address environmental externalities or underinvestment in Research & Development (R&D). Subsidies can have sound rationales and achieve important policy objectives, in situations when markets may not deliver optimal outcomes or to pursue social objectives, such as regional cohesion.

An unintended consequence of state support may be that it might distort competition in favour of certain enterprises, which may, as a result, have lower costs or a stronger financial position than their competitors. For this reason, the Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality calls for jurisdictions to preserve “Competitive Neutrality when designing measures that may enhance an Enterprise’s market performance and distort competition”, in order to ensure a level playing field and reap its benefits. As state support can distort competition, it can become relevant in competition enforcement cases especially in light of the growth of state support measures in recent years (OECD, 2022[3]).

This Competitive Neutrality Toolkit uses the generic term of state support measures to indicate the various forms of financial support provided by the state. The term covers both support provided to one or several specific recipients and general support provided to the whole economy. Crucially, it does not imply that this support necessarily benefits an enterprise in a selective way and distorts competition. The good practice approaches presented in this chapter are precisely meant to help evaluate if state support is indeed selective and distortive, inspired in particular by the State Aid framework in the European Union.

The overall principle, stated in Article 107 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), is that “any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods shall, in so far as it affects trade between Member States, be incompatible with the internal market”.1 Under EU legislation, State Aid is generally prohibited but there are some circumstances in which it can be justified. This assessment results from a balancing exercise between the negative impact of aid in terms of distortion of competition, on the one hand, and its positive effect of achieving a public policy objective, on the other. Similarly, the approach outlined in Chapter 8 calls for an assessment of the policies that may distort competition. The good practice approaches in this chapter help identify those policies that deserve such in-depth assessment.

State support can distort international markets too, and for this reason it is regulated in the multi-lateral World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) (IMF et al., 2021, pp. 17-22[4]), as well as in certain preferential trade agreements (OECD, 2022[5]).2 The former contains a definition of a subsidy (defined as a financial contribution conferring a benefit that is specific to a certain company, group of companies or sector) and distinguishes between those subsidies that are prohibited, which are presumed to distort trade, and actionable subsidies, whose adverse trade effects need to be demonstrated before any countermeasures can be deployed. Some trade agreements contain provisions about state support granted specifically to SOEs (see Box 6.3). Recognising the important role of SOEs in many economies, as well as for international trade and investment, the Recommendation recognises that SOEs “may be subject to more stringent specific rules which limit the provision of government support to such entities”.

Support directly provided to consumers to purchase a certain product or service would not appear to fall within the scope of analysis, if consumers can use this financial support freely to purchase the good or service from any supplier. However, if support is only disbursed when consumers purchase from certain suppliers or from suppliers with certain characteristics, such as local suppliers, this may result in distortions and merit in-depth analysis (Hancher and Salerno, 2021, p. 75[6]).3

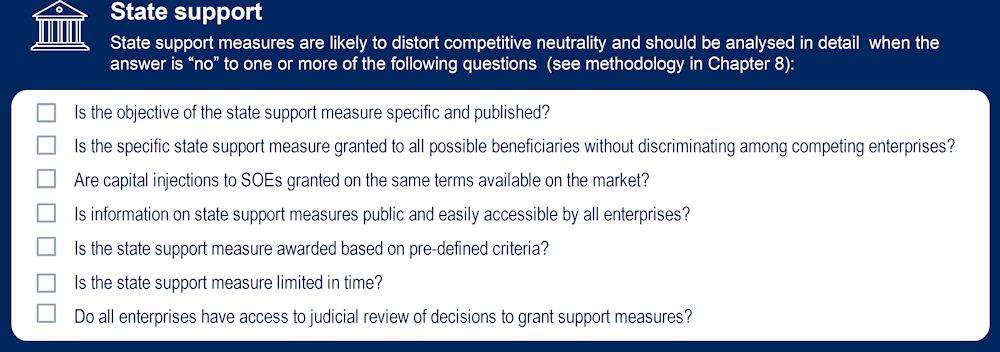

A set of questions to help identify policies that can potentially distort competitive neutrality is presented below. When a policy is not in line with at least one of the questions or good practice approaches, it has the potential to distort competition and should be analysed in detail. Chapter 8 sets out the main steps of the analysis.

Figure 6.1. Suggested questions to assess state support

6.1. Identify and disclose the specific public policy objective to address and the extent to which the state support measure is likely to address it

Good practices show that state support measures are designed with a clear public policy objective in mind. As discussed in Chapter 2, the objective of state intervention may be to address market failures, such as externalities, or to promote social objectives, such as reducing inequality among a country’s regions. In addition, state support may be granted in exceptional circumstances to address emergency situations, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, or to restructure firms in financial difficulty.4

State support targeting a market failure is granted to influence business behaviour. As an example of intervention that addresses externalities, investment in R&D by a business produces spill overs that benefit other businesses that have not invested. The business that invests in R&D cannot appropriate all the returns on its investment and therefore would have an incentive to underinvest. This externality provides the rationale for state support of R&D. State support aims to increase R&D investment compared to the level that businesses would choose without support. There are alternative ways to support investment, for instance by lowering the cost of capital or by providing subsidies. However, the different alternatives may not be equally effective in influencing business behaviour, in this case increasing R&D investment (Criscuolo et al., 2022[7]).

Authorities are expected to spell out how state support contributes to achieving the policy objective and to what extent it addresses it. For instance, in an opinion concerning purchase subsidies for vehicles by the Spanish government, the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) recommended that state support measures be designed to closely address the specific policy objective at hand (CNMC, 2022[8]).5

If the public policy objective and the mechanism through which it should affect behaviour are clear, policy makers can compare state support with alternative tools that might have a less distortive effect on competition There may be equally effective policy interventions that require less financial support. Therefore policy makers should grant the minimum support necessary to achieve the desired change in behaviour while minimising potential distortions, in line with the examples below.

Finally, it is a good practice to disclose the objective of state support measures early on to promote accountability and limit discretion. In particular, it can facilitate ex post reviews of the effectiveness of state support (Oxera, 2017[9]). Nevertheless, as further discussed in Section 6.2, lack of transparency on state support is still an issue, which may prevent the identification and assessment of the objective of the measures.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In the EU, the assessment of state support6 involves the identification of the possible objectives of common interest relating to economic and social development which are targeted by the support.7 This is necessary to conduct the so-called balancing test, which aims at balancing the support measure’s negative effects on trade and competition within the EU with its positive effects in terms of achieving well-defined objectives of common interest (European Commission, 2009[10]).

In Japan, according to the guidelines by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC), when “public support for revitalization is necessary to achieve various policy objectives, it should be provided on a scale and with a method that are the minimum necessary for revitalizing the business concerned” (JFTC, 2016[11]).

In the US, during the 2008 financial crisis the government intervened in the car industry to rescue and restructure GM and Chrysler. The assessment conducted in order to decide how to respond to the companies’ requests for extraordinary support involved economic arguments, as well as political and social ones. This required identifying what public policy objectives the government would be able to achieve through the rescue. It was agreed that the costs of not rescuing would be too high. This would have entailed extreme job losses, with “widespread spillovers into supplier industries and auto dealerships, as well as knock-on macroeconomic effects”. Overall, it was considered that the rescue was needed to “prevent an uncontrolled bankruptcy and the failure of countless suppliers, with potentially systemic effects that could sink the entire auto industry” (Goolsbee and Krueger, 2015[12]). Following the intervention, the companies returned in private hands.

6.2. Identify and disclose state support measures

Transparency about the support granted by the state is considered a starting point to address state support issues (IMF et al., 2021, p. 26[4]). Good practice approaches show that information on the support measures made available by the state and information on the actual support granted to individual enterprises is published:

When the state issues programmes to fund directly or otherwise support certain activities. If these schemes are published and advertised clearly, any potential beneficiary will become aware and can request the support. Similar access to information is given to every competitor if they are to have similar access to the available support measures.

Once the support has been granted, the specific measures that benefit individual enterprises are disclosed to help promote accountability, reducing the risk of discretionary behaviour by the authority in charge of state support. Making data available can also help assess the extent and the impact of the measures, including in an international context (OECD, 2023[13]).

Transparency is addressed in other OECD standards, specifically the SOE Guidelines and the Voluntary Transparency Standard for Internationally Active SOEs (the “Voluntary Transparency Standard”). Building on transparency requirements in the SOE Guidelines, the OECD Voluntary Transparency Standard includes a recommendation to “disclose any subsidies and other forms of government support (direct or indirect) that confers an advantage to the recipient SOEs over private competitors and accorded by virtue of government ownership or control. […] Disclose any relation with state-owned financial institutions.” The standard applies to “large SOEs” that carry out economic activities and are active in international markets,8 while the good practice approach identified in this section, based on the OECD Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality, concerns government support granted to either SOEs or private competitors.

Lack of transparency on state support undermines confidence in a level playing field and opens the possibility for more discretion in granting support, potentially distorting competition. It also prevents the correct measurement of support measures and related analysis, such as evaluating their impact and whether they ultimately achieve their objective. There is evidence that this good practice approach is often not followed in practice, even though there is a WTO obligation to notify subsidies:9 “The share of WTO members that provide subsidy notifications to the SCM Committee decreased from 75 to 35 percent between 1995 and 2021” (IMF et al., 2021, p. 16[4]). In part, this is because, under current rules, it is sometimes unclear whether a particular measure can be considered a subsidy and by whom. This makes it difficult to determine the amount of subsidies and, consequently, their degree of trade distortion. In addition, opacity is helped by funding granted indirectly through SOEs and other entities that are related to the government, instead of flowing directly from the State (OECD, 2021[1]).10 Countries may differ in the definition of SOEs and the degree of disclosure of actions taken by them, contributing to the difficulty of assessing funding flowing through SOEs.

The growing importance of internationally active SOEs, combined with little transparency on support measures, is among the factors leading to the new Regulation on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market that came into force in the European Union in January 2023 (see Box 6.1).

Box 6.1. The EU Foreign Subsidies Regulation

The EU’s state aid regime seeks to promote the EU internal market by preventing EU Member States from granting distortive subsidies. Foreign subsidies granted to enterprises active in the EU are not subject to this framework.

In November 2022, the EU adopted a regulation on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market. The regulation seeks to address a regulatory gap in the control of foreign subsidies and aims to ensure a level playing field by addressing such market distortions.

Under the Regulation, two ex-ante notification regimes and a general screening tool apply. These tools address 1. Mergers and acquisitions, 2. Public procurement and 3. Other market situations, where there is a selective financial contribution by a non-EU government conferring a benefit on an undertaking that is carrying out an economic activity in the internal market (a foreign subsidy).

1. Mergers and acquisitions

Mergers and acquisitions involving financial contributions granted by non-EU governments, where at least one of the merging undertakings, the acquired undertaking or the joint venture is established in the Union and generates an aggregate turnover in the Union of at least EUR 500 million and the parties were granted a foreign financial contribution of more than EUR 50 million over the previous three years) must be notified to the Commission and are subject to an ex-ante review.

2. Public procurement

The Regulation sets out a notification regime for bidders in public procurement processes above a certain threshold (value is equal to or higher than EUR 250 million). Bidders must submit information on any foreign financial contributions received in the preceding three-year period or confirm that no such contributions were received.

3. Other market situations

The Regulation sets out ex officio review powers where the Commission can examine potentially distortive foreign subsidies, which do not meet the stipulated thresholds and for other market situations, such as greenfield investments. The Commission may undertake a preliminary review and where there are sufficient grounds, can initiate an in-depth investigation.

The Commission will conduct an assessment to determine whether the transaction involves a distortive subsidy. The Regulation sets out a non-exhaustive list of indicators of distortions on the internal market such as the amount, purpose, and nature of the subsidy. It also sets out categories of foreign subsidies most likely to distort the internal market such as unlimited guarantees and those granted to failing undertakings without appropriate safeguards.

Where the Commission considers the subsidy distortive, it will conduct a balancing test, which involves considering the potential positive and distortive effects of the subsidy. Depending on the outcome, it may then accept commitments, impose redressive measures or prohibit the transaction.

Sources: European Union (2021[14]), Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/PE-46-2022-INIT/en/pdf.

Examples

The following examples show that selected jurisdictions publish information on state support:

In the European Union, a portal makes available information on state support measures notified by Member States to the European Commission under its State Aid Framework.11 It covers support schemes and individual awards, with information including the name of the beneficiary, the amount of State Aid and its objective (e.g. investment aid to SMEs, aid for broadband infrastructure). The European Commission also publishes yearly analyses of State Aid data provided by Member States.12 In addition to reporting at EU level, member states publish information on state support, as in the following examples:

In Latvia, the individual ownership entities publish information on state funding, grants, or subsidies, both planned and received, by each SOE (OECD, 2022, p. 57[15]).

In Spain, the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) “has legislative power to release annual reports on national state aid. The annual report typically includes statistical information about the aid granted (e.g. whether it increased over the past year, the type of aid), and summaries of new legislation, case law and the initiatives of the CNMC in the field of State aid. The CNMC also has a database with the aid measures granted in Spain” (OECD, 2021, p. 37[16]).

Sweden discloses the benefits applicable to SOEs including non-commercial assistance or other exemptions / immunities. In the case of enterprises that have public policy assignments for which they receive funds, the country annually publishes the amount of budget appropriation for the financial year and the total income of the SOE (OECD, 2022, p. 57[15]).

In Japan, the guidelines by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) on public support for revitalisation (JFTC, 2016[11]) recommend that “information on individual cases and on general matters such as support standards or procedures should be disclosed as much as possible, so that the possible impacts of public support for revitalization on the market mechanism can be identified, and competitors of beneficiaries are able to submit their opinions regarding the possible impacts of public support for revitalization on competition and can take appropriate measures in response.” In addition, the Regional Economy Vitalization Corporation of Japan (REVIC) was established with funds from the Japanese government and private financial institutions to provide business revitalisation support to enterprises with useful management resources but excessive debts. REVIC’s support standards have been published and follow the JFTC’s guidelines. The relevant regulations also state that in case of supporting large-scale business, REVIC should disclose the name of the individual business and a summary of its revitalisation plan (Regional Economy Vitalization Corporation of Japan (REVIC), 2023[17]).13

In Moldova, the Competition Council implemented a “Register of State Aid in Moldova”, with the support of the World Bank. The State Aid Register has introduced a monitoring system for State Aid and its impact on the competitive environment (OECD-GVH, 2020, p. 8[18]).

In Ukraine, the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine (AMCU) is the body authorised to monitor and control State Aid. The competition authority maintains a State Aid Portal on its official website with information on state aid cases and decisions (OECD, 2021[19]).

In the UK, the subsidy transparency database provides information on all available schemes and the subsidies awarded to businesses.14

The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) requires the parties to disclose every year the specific subsidies they grant (WTO, 2021[20]). Subsidies are defined as financial contributions “by a government or any public body within the territory of a member” as well as “income or price support which increases exports of any product from, or reduce imports into, a member’s territory” (IMF et al., 2021[4]). For a financial contribution or for income or price support to constitute a subsidy, they must also confer a benefit to the recipient.

6.3. Assess if state support measures, such as loans, guarantees and state investment in capital, are granted in line with market principles

According to the Recommendation jurisdictions should “avoid offering undue advantages that distort competition and selectively benefit some Enterprises over others”. This provision can be broken down into its components to provide some practical guidance on how jurisdictions can implement the Recommendation by assessing if an Enterprise receives a benefit, i.e. better conditions than those available in a market transaction. If a support measure indeed confers an advantage, the next steps based on the Recommendation would be to analyse if this is a selective benefit (see the good practice approach 6.4) and to analyse the distortions of competition the measure creates, following the methodology in Chapter 8. In some cases, these benefits arise from the availability of state assets to SOEs from the time when they were not corporatised and markets were not liberalised yet. For instance, in a Competitive Neutrality Review of Small Parcel Delivery Services in ASEAN, the OECD found that in some countries SOEs benefitted from “wide distribution networks with facilities in prime locations on state-owned land, assigned under long-term leases at nominal rates” (OECD, 2021, p. 76[21]).

The SOE Guidelines contain a similar provision, referring specifically to SOEs, while the present Competitive Neutrality Toolkit concerns also privately-owned market players. According to the SOE Guidelines, “SOEs’ economic activities should face market consistent conditions including with regard to debt and equity finance” [OECD/LEGAL/0414]. State ownership can grant benefits such as an implicit guarantee, which would lower the SOE’s cost of capital. These should be recognised as ongoing forms of support, as in the Australian framework (Australian Government, 2004[22]). The SOE Guidelines also refer to funding by state-owned financial institutions, flagging the risk that granting finance at beneficial terms alters SOEs’ incentives and leads to wasted resources and market distortions. To address this risk, the SOE Guidelines provide that “the state should implement measures to ensure that inter-SOE transactions take place on purely commercial terms” [OECD/LEGAL/0414].

Determining in practice whether state support is granted in line with market principles involves comparing the conditions at which similar funding would be provided by the private sector. There is extensive guidance and case law in the EU on how to conduct this assessment, using the so-called Market Economy Operator Principle (MEOP) (Box 6.2). Equally, several cases in Australia focus on the comparison between the terms at which funding is available to SOEs and those available on the market for competitors. More broadly, there is a question of whether SOEs earn a commercial rate of return on their activities, which is what a privately-owned competitor would be required to. Annex 6.A to this chapter includes some examples.

Box 6.2. The Market Economy Operator Principle (MEOP)

In the EU framework for State Aid control, if the State grants funding to an enterprise on terms that the enterprise could have received from the market, this funding does not confer an advantage to the enterprise, and it is allowed under EU rules. It is therefore important to assess if state support measures are granted in line with the terms that would be acceptable to a market operator. In essence, this is the Market Economy Operator Principle (MEOP).

Developed initially to assess investments by the State, the MEOP has evolved into a tool that is applied, for example, to loans, guarantees or tax measures. It is also relevant in transactions by SOEs, for instance when they supply products and services, based on the so-called “private vendor test”. Given the comparison with a market economy operator, the MEOP is applicable only when the State pursues economic activities and is not acting as a public authority. The circumstances under which the MEOP can be used, for instance whether to take into account previous State Aid, are an area subject to intense debate.

The European Commission establishes MEOP compliance using direct (pari passu transactions, tenders) and indirect (benchmarking, profitability) methods:

The direct methods include situations when a transaction involves pari passu the State and private operators. This is interpreted to mean that the State and private operators enter the transaction at the same time, and they face the same risks and rewards. Another pre-requisite is that the role of private operators is not marginal, so their contribution to the transaction must be significant.

MEOP compliance can also be established if a transaction is carried out using tender procedures. In this case, the tender should be “competitive, transparent, non-discriminatory, unconditional and in line with public procurement rules” (Robins and Puglisi, 2021, p. 23[23]).

Benchmarking involves comparing the price and other terms of a transaction with those of similar transactions conducted by private operators. When the price of the public transaction falls within the range of prices from similar transaction, the price is in line with the MEOP.

Under profitability analysis, the State’s expected return from the transaction is compared with the return that a market operator would require in similar transactions, for instance with similar levels of risk. If the expected return of the State is greater than or equal to the return in similar transactions, the measure is MEOP compliant.

Source: Robins and Puglisi (2021[23]), The market economy operator principle: an economic role model for assessing economic advantage, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789909258.00009.

If support is not granted in line with market conditions, this suggests that absent state intervention a market operator would not provide the support or funding, for instance because the investment is not viable on its own. There may be other explanations for the lack of funding by a market operator, though, such as financing constraints. If the beneficiary of state support faces financing constraints it may not be able to fund the investment at market rates. For example, the availability of finance is one of the reasons that firms mention as a barrier to climate investment in a survey by the European Investment Bank (European Investment Bank, 2022[24]). The authors of the report conclude that policymakers should support firms in those countries where they face constraints.

Examples

The following examples show how different jurisdictions assess whether state support is granted in line with market conditions:

In Australia, when government-owned enterprises are able to borrow at a lower cost than their competitors, thanks to the lower perceived risk of government-owned enterprises, they are required to make so called debt “neutrality adjustments” (Australian Government, 2004, p. 21[22]). This involves comparing the government-owned enterprise’s cost of debt with the benchmarking rate that would be charged to the enterprise if it was privately-owned.

Under the EU framework, benchmarking methods can be used to assess compliance with the MEOP. Portugal developed a methodology to calculate the market prices of state guarantees on loans provided to SMEs by the State under the so-called national system of mutual guarantees (Sistema Nacional de Garantia Mutua, “SNGM”).15 The pricing model established the market premium for State guarantees, building on the European Commission’s Guarantee Notice (European Commission, 2008[25]). If the premiums charged by the State on loan guarantees are calculated based on the methodology, the guarantees are provided in line with market principles and are not considered to grant an advantage to the enterprises receiving those guarantees.

6.4. State support should be based on clear, objective and non-discriminatory criteria rather than the identity of the enterprise that receives it, except for emergency measures

As mentioned earlier, according to the Recommendation, jurisdictions should refrain from awarding selective benefits to certain market players. This provision is to be read in conjunction with the previous good practice approach, about assessing if a state support measure grants a benefit to enterprises. By its very nature, a selective benefit has the potential of distorting competition and would need to be assessed in detail using the methodology in Chapter 8.

Unlike benefits awarded horizontally to all market players, such as the option of paying taxes in instalments, some state support measures are granted only to enterprises in a certain sector or in a certain region. For instance, policies to reduce regional disparities include incentives for enterprises to invest in lagging regions, such as tax incentives dependent on location, investment subsidies and infrastructure policies. In some cases, these may distort competition, for example tax measures that benefit specific companies can be presumed to be selective.

Establishing whether a measure is selective in the first place is not clear-cut, though, and the details of the measure and its impact on competition need investigating on a case-by-case basis. While measures targeting specific sectors or regions may appear selective and discriminatory, this is not a foregone conclusion (see example on Redegal below).

When public policy objectives seem to require targeted interventions, it is at least important that those interventions follow clear, objective and non-discriminatory criteria. However, even in these cases support measures may still result in selective benefits with their impact on competition being assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Moreover, horizontal measures can also be deemed selective if authorities retain excessive discretion, enabling them to award support based on unclear criteria and favour specific competitors. Guidance by the European Commission (2009[10]), states that a scheme can be considered selective if the authorities “enjoy a degree of discretionary power”.

Given the importance of SOEs in certain economies and the fact that they tend to receive relatively more support than privately-owned companies (OECD, 2023[13]), the Recommendation recognises that “State-Owned Enterprises may be subject to more stringent specific rules which limit the provision of government support to such entities". Examples of provisions that address specifically SOEs can be found in some Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) (see Box 6.3).

Box 6.3. Provisions on SOEs in trade agreements

While the current WTO rules on subsidies apply both to privately-owned and state-owned enterprises, some Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) deal specifically with support provided to SOEs. These agreements are the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Australia-Peru agreement and the United States, Mexico and Canada Agreement (USMCA).

The agreements deal with so-called “Non-Commercial Assistance” (NCA) provided directly or indirectly by a government to its SOEs. They prohibit NCAs that have “‘adverse effects to the interests” of another party to the agreement. The USMCA goes beyond this rule and prohibits certain types of subsidies to SOEs without the need to show their negative effects. For instance, this includes support to SOEs that are insolvent or almost insolvent, without having a restructuring plan. It also includes converting debt into equity, when this is not done according to the normal investment practice that a private investor would follow.

The clauses dealing with SOEs specifically improve the available legal tools to challenge NCAs, such as enabling the signatories to the agreement to request information on NCAs granted by another signatory. However, there are still difficulties in enforcing the provisions. For example, in the case of the NCAs provided to SOEs in financial difficulties, which are directly prohibited by the USMCA, it may not be easy for a signatory to assess the financial situation of an SOE located in another party to the agreement.

Source: OECD (2022[5]), Government support and state enterprises in industrial sectors, https://one.oecd.org/document/TAD/TC(2022)9/FINAL/en/pdf.

In emergency situations, certain enterprises may require liquidity support or other targeted support that is not awarded through standard procedures. For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic, certain requirements for awarding state support in the European Union were relaxed (see example below about the so-called Temporary Framework). Under similar circumstances, the targeting might be necessary, for example to reach companies that are facing temporary liquidity constraints due to financial-market turmoil but are otherwise solvent.

Examples

The examples below illustrate the assessment of selectivity and refer to situations where state support was granted based on clear, transparent and objective criteria:

As part of its plan to connect all Canadians to high-speed Internet, in 2020 the Government of Canada launched a $2.75 billion Universal Broadband Fund (UBF) to support broadband projects that bring Internet at speeds of 50/10 Megabits per second (Mbps) to rural and remote communities. Applicants to the fund were required to have the ability to design, build and run broadband infrastructure and needed to identify who would build, own and operate the broadband network. The process to select the projects involved a 3-stage assessment: “Stage one involves meeting basic eligibility requirements. Stage two evaluates essential criteria such as managerial capacity, technical feasibility and sustainability, and stage three involves comparing projects in the same geographic area against each other, focusing on relative technical and financial merits, as well as community benefits, such as commitment to local employment” (Government of Canada, 2021[26]).

In the Redegal case, the European Commission argued that a measure designed to facilitate the transition from analogue to digital terrestrial television in the Spanish region of Galicia was selective and constituted State Aid. The assessment of whether state support is State Aid is carried out on the basis of a set of criteria set out in the EU State Aid framework.16 These include whether the support measure grants an “advantage on a selective basis”. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) however found that a measure that applies only to a certain economic sector is not necessarily selective. It noted that the notion of “selectivity” means that a measure “has the effect of conferring an advantage on certain undertakings over others, in a different sector or the same sector, which are, in the light of the objective pursued by that regime, in a comparable factual and legal situation” (paragraph 61, emphasis added) (European Court of Justice, 2017[27]). Therefore, it was not possible to presume that the measure would be selective only because it applied to a certain economic sector. The Court concluded that the situation of broadcasters using terrestrial technology, which benefitted from the measure, should have been analysed and compared with the situation of broadcasters using other technologies.

To support the economy after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the European Commission issued a Temporary Framework for State Aid Measures (European Commission, 2021[28]).17 Under the framework, Member States could provide support to a company, e.g. for up to EUR 2.3 million under chapter 3.1 (“Limited amounts of aid”), through mechanisms such as direct grants, loans or equity, provided that the company was not in financial difficulty as of 31 December 2019. In the case of micro or small enterprises, the requirement about financial difficulty could be relaxed, provided that they did not benefit from rescue or restructuring aid. Lower limits were set for companies active in the agricultural and fisheries sectors. Further support measures were possible under other chapters of the Temporary Framework.

In many countries, SMEs benefit from tax preferences that lower their taxes and from simplification measures to reduce their costs of compliance. These exceptions are available to all enterprises fulfilling objective criteria. For instance, Germany allows accelerated depreciation for SME assets that cost less than EUR 235 000 (OECD, 2015, p. 64[29]).18

Governments support investment in Research and Development (R&D) by private and public enterprises through measures such as tax incentives and direct funding (OECD, 2020[30]). For instance, Italy uses tax credits to promote innovation in technologies for the technological and digital transformation of production processes. The tax credit consists of different percentages of the investment cost, depending on the amount of the investment itself. The credit can be granted to all enterprises, regardless of their ownership, size and legal form.19

6.5. State support measures should include clear exit strategies, in order not to perpetuate state support beyond the necessary

State support to achieve a specific public policy objective is likely to be timebound and to be withdrawn when that objective has been achieved. In practice, state support may be provided to certain market players on an ongoing basis, which reduces their incentives for greater efficiency and innovation. When this support grants a selective benefit to some competitors only, at the expense of others, it distorts competition, and its negative effects cumulate over time. At the extreme, overgenerous support risks keeping in the market firms that are not viable and would exit the market (so-called “zombie” firms), absent state support. In addition to distorting competition, this has a negative impact on the broader economy as zombies absorb resources from more productive competitors and reduce aggregate productivity (Fontoura Gouveia and Osterhold, 2018[31]).

Long-standing support to certain sectors, such as agriculture, are well documented and over time even more sectors, including steel, aluminium and ship building, have benefitted from structural support which has resulted in market distortions and excess capacity (OECD, 2021, p. 80[32]).

It may be useful to distinguish between state support to invest (e.g. to overcome market failures and provide incentives to recipients) and support to operating expenses. The former can be beneficial even though it may result in distortions if it becomes permanent, as highlighted in the paragraph above. Granting financial support to cover operating expenses may not have a clear time limit, unless it is provided to address very specific circumstances, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, and is not typically designed to address efficiency or equity considerations. These features make it more likely to be distortive compared to support to investment. In terms of type of support, equity investment by its own nature is not a one-off benefit but amounts to continuous support if the State accepts below-market returns (OECD, 2021, p. 85[32]).

Examples

The following examples show how different jurisdictions have implemented this good practice approach:

During the Covid-19 pandemic, several countries provided support to the air transport sector. Some of these measures included clear exit clauses. For instance, this was the case with Estonia’s equity increase in AS Nordic Aviation Group and Latvia’s equity investment in Air Baltic Corporation AS (OECD, 2021[33]).

In Japan, the guidelines by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) on state support advise against providing rolling support to enterprises, given that this would reduce their incentives to become more efficient: “repeatedly providing support has a larger impact on competition compared to support provided on a once-only basis, in the sense that the former is likely to impair incentives for beneficiaries to improve their business efficiency” (JFTC, 2016[11]).

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the Portuguese Competition Authority (AdC) issued a publication on the role of competition in the economic recovery. In relation to state support, AdC advocated that, “in deploying financial support to firms, it is important to forestall a restructuring plan and an effective a transparent exit strategy for public financing” (Autoridade de Concorrencia, 2021[34]). This was motivated by empirical evidence on the negative effects that funding “zombie” firms (i.e. those that only survive in the market thanks to financial support) have on productivity and efficiency.

In 2009, the US Congress approved a plan to respond to the economic crisis and promote growth. The Troubled Assets and Relief Programme (TARP) included, among other instruments, grants, loans and funds to recapitalise banks and corporates. Embedded in the programme was the aim to exit investments while “maximising returns, promoting financial stability and minimising market disruption” (OECD, 2020, p. 16[35]).

6.6. Consider remedial measures that may reduce the competition distortions arising from state support

The checklist in annex includes a list of questions, based on good practice approaches in this Chapter, to help competition authorities and policy makers identify the state support measures that should be analysed to assess if they distort competition. Chapter 8 describes a general methodology to analyse the expected impact of state support measures and regulations. If, based on that methodology, a state measure is found to distort competition the authorities may look for alternatives that are less distortive. For instance, lowering the amount of support could still achieve the objective while not distorting competition or having a less distortive impact.

When the authorities cannot identify any alternative measures and consider proceeding with measures that distort competition, good practices show that remedies may reduce competition distortions arising from state support. These remedies could include structural provisions or behavioural constraints. For instance, a support beneficiary, especially if it is a large company, may be required to divest certain assets to help competitors grow or to attract new entrants, ultimately increasing competition in the market. Remedial measures are usually considered carefully to make sure that they do not introduce further distortions. For instance, following the financial crisis and the provision of restructuring aid to banks in the European Union, there were some questions that behavioural constraints, such as those limiting the banks’ abilities to lend or to access deposits, limited competition in the market and could restrict output further than was already the case, with negative effects on consumers and the economy (Ahlborn and Piccinin, 2009[36]).

Examples

The following examples show how different jurisdictions have implemented this good practice approach:

In the European Commission’s 2010 decision (C 9/2009), the State Aid package to support Dexia was complemented by measures to limit distortions of competition. In particular, Dexia was required to divest some subsidiaries and faced a ban on acquisitions (Boudghene et al., 2010[37]).

In Japan, the 2016 guidelines by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) on public support for revitalisation (JFTC, 2016[11]) state that the following measures could be taken for minimising the effects of public support for vitalisation on market competition: (i) behavioural measures to restrict business activities, such as restricting investment in new production facilities and new business sectors for a certain period, when the absolute business size and market share of beneficiaries are expected to be large and they are expected to gain a significant competitive advantage due to the support; (ii) structural measures to reduce in advance the beneficiaries’ production capacity within the market, such as transferring certain business and disposing of certain production facilities, when the beneficiaries’ absolute size and market share are large at the time the details of support are finalised and they are expected to gain a significant competitive advantage due to public support for revitalisation, which can serve as leverage upon its completion. When impact minimisation measures are implemented, their specific details and timing should be determined when the support is decided, as there is a risk of reducing the incentives for beneficiaries to improve efficiency through their own business management efforts, and for their stakeholders to be involved in the business revitalisation.

6.7. Procedures and guidelines should provide transparency on how state support measures are assessed

As jurisdictions accumulate experience in assessing the impact of state support on competition, they may identify certain types of support that are less likely to create distortions. They may consider that there is limited benefit in investing resources in assessing all state support measures and choose to focus the assessment on those that are potentially more distortive. The checklist in Chapter 8 can provide an additional resource to identify problematic state support measures.

This experience can be encapsulated in guidelines, which can help policy makers when designing future state support (even though this is not a common practice in most jurisdictions). For example, there is a low risk of distortion from supporting investment in infrastructure in areas where this infrastructure is not present and is not likely to be deployed in the near future. Moreover, some state support does not concern economic activities (e.g. cultural and heritage conservation) and does not risk distorting the level playing field, therefore its assessment is not necessary.

State support granted to enterprises, when of limited amount, may be less likely to distort competition. Each jurisdiction may define monetary thresholds below which state support is presumed not to harm competition. In setting these thresholds, they may consider factors such as the size of the economy and average turnover. In practice, monetary thresholds may be more straightforward to apply when the state provides direct grants or capital injections. In other cases, such as loans or guarantees, determining the actual amount of state support is more complex. For instance, since these instruments involve several instalments over time, it is necessary to calculate their value at the time they were granted, based on suitable assumptions about interest rates.

More generally, the assessment of state support measures should be transparent and predictable, in line with the Recommendation on Transparency and Procedural Fairness in Competition Law Enforcement [OECD/LEGAL/0465]. Procedures to carry out the assessment can improve its predictability and reassure market players on the impartiality of the assessment.

Examples

The following examples show how different jurisdictions have implemented this good practice approach:

Australia has published guides on competitive neutrality, including on how to assess whether government-backed enterprises enjoy benefits such as cost of equity or debt lower than their privately-owned competitors (Australian Government, 2004[22]). The states and the federal government are expected to carry out this assessment.

The European Commission has issued a regulation setting out criteria for the exemption of some types of aid from the notification requirement that applies to state support in the EU, specifically de minimis aid not exceeding EUR 200 000 per undertaking over any period of three fiscal years.20 The Commission has published various regulations identifying thresholds for notification which may vary by sector, for instance there are different rules applicable to aid in the agriculture sector and to services of general economic interest.

The UK has published guidance to help public authorities with the requirements under the Subsidy Control Act 2022. This provides step by step instructions, for instance to assess whether state support qualifies as a subsidy and needs assessment (Department for Business & Trade; Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022[38]). The government has also identified exemptions from assessment for so-called minimal financial assistance, capped at GBP 315 000 over three financial years.

Finally, ex post evaluation can inform the design of future support measures and can help develop criteria to reduce competitive distortions. In the EU, ex post evaluation may be introduced as a requirement in state support measures, such as large schemes (Robins and Geldof, 2018[39]). In addition, the European Commission publishes annual reports on State Aid amounts, based on information that member states are required to submit every year.

Annex 6.A. Assessing the commercial rate of return of an SOE – examples from the Australian experience

The good practice approach 6.3 covers assessing if state support measures are granted in line with market principles. This involves, for instance, that debt provided by the state, directly or indirectly, attracts the same interest rate, and be applied the same terms, as debt provided by privately-owned financial institutions. In addition, jurisdictions may monitor if an SOE receives implicit benefits, for example if loan rates charged by financial institutions are lower than those charged to the SOE’s privately-owned competitors.

The Australian experience offers a practical illustration of this good practice approach. It is a well-established framework that focuses on competitive neutrality between SOEs and privately-owned businesses (Smith, Healey and Bai, 2023[40]). Under the Australian Competitive Neutrality framework, SOEs are generally referred to as government businesses, therefore this annex adopts the same terminology.

To ensure competitive neutrality, government businesses are expected to earn a commercial rate of return, intended as the rate that justifies retaining the assets in the business over the medium to long term. Investors need to be compensated for the opportunity cost of investing in the business, that is “the return that they could have earned from the next best available investment” (IPART, 2023[41]).

In order to assess if a government business earns a commercial rate of return, it is necessary to determine the following: (a) an appropriate commercial rate of return for the particular government business (the target rate of return); (b) the actual rate of return of the government business. If the actual rate of return falls short of the commercial rate of return, it means that the government accepts a lower return than a commercial investor would and therefore the business receives implicit benefits.

This Annex includes a high-level overview of the approach to set a target rate of return and to estimate the government business’s actual rate of return, complemented by relevant examples. While the overall framework of assessment is specific to competitive neutrality, the concepts used in the assessment are also commonly used in antitrust and in regulatory assessments.

The rate of return

Setting the target rate of return may involve a different approach, depending on the situation. Where capital costs are not significant, the approach adopted in Australia is to require that a government business should earn a rate of return equal to the government’s long-term bond rate plus a margin for risk (Australian Government, 2004, p. 30[22]) (IPART, 2023, p. 84[41]). For example, with a long-term (10-year) government bond rate of 5% and the margin for a medium risk of 5%, the target rate of return is 10%.

Where the capital costs of a business activity are significant, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) could be used to estimate the target rate of return. This is essentially the average rate that a business pays to finance its assets.21 It quantifies the cost of the business’s debt and equity and takes account of factors such as market risk. This approach will require benchmark data on similar activities in the private sector, therefore it is suitable for government businesses that are active in sectors with a reasonable number of relevant businesses.

In order to determine whether the target rate of return is being achieved, it is necessary to assess the actual rate of return of the government business. It should be noted that there are several methods to estimate the actual rate of return and the most suitable one may depend on factors such as the activity in question. For example, it may be reasonable to use indicators such as return on assets or return on capital employed in capital-intensive activities, while they may not be appropriate for services businesses, where the profit margin approach would be more appropriate.

Estimating a measure of rate of return requires assessing:

a. the earnings of the government business (i.e. revenue minus costs);

b. the market value of total assets (i.e. debt plus equity);

c. the appropriate time period over which to make the assessment.

The remainder of this Annex provides examples from the Australian experience about point (a) above and some discussion of points (b) and (c).

Revenues and costs

Under the Australian Competitive Neutrality framework the relevant revenues and costs refer only to the particular business activity under consideration, not all activities of the government business (such as non-commercial activities). This information may be available from the standard business accounts of the business, but this may not necessarily be the case for businesses involved in more than one activity. Requests for information may be needed when the information is not readily available.

For a government-owned business to be competitively neutral all the costs attributable to its productive activity are to be paid. When the business supplies more than one product or service, there will inevitably be costs that need to be allocated to the activity under consideration. This can be accomplished in various ways, for instance by estimating the fully distributed cost or the avoidable cost of the business activity.

Costs can be measured based on all costs that are exclusive to the particular government-owned business plus any shared costs on a pro-rata basis, referred to as fully distributed cost. This method of allocating costs would be appropriate when the investment in the joint resource is not fully justified by the non-commercial use of the resource. For example, if a government body purchases a large building that it will partly use as a library and will partly rent out, the building is a joint cost between the two different uses. The cost of the building should therefore be shared between them. Fully distributed cost would be appropriate to allocate the cost of the building to the different activities (IPART, 2023, p. 81[41]).

Avoidable cost is an alternative basis for allocating common costs where a business supplies multiple products or services. It measures those costs that would be avoided if the commercial activity did not occur. It is appropriate where a government-owned business supplies multiple products and the investment in the joint resource would have been justified even in the absence of the non-commercial activity. For example, if rural community is connected via a railway line for social policy reasons, there may be excess capacity on that line and it could be made available on commercial terms to a rail freight operator. Since a single track is the minimum possible unit of capacity, that is spare capacity is unavoidable, the suitable cost allocation method would be avoidable cost. The commercial activity of rail freight would therefore pay its avoidable cost (IPART, 2023, p. 81[41]).

Further adjustments

A government may impose additional costs on government businesses that are not borne by their private sector competitors. For example, they may be required to meet more rigorous product or safety standards or to meet uncompensated public service obligations. Such costs would need to be deducted to determine the net cost of supply of the goods or service.

Non-cost advantages could include preferential access to information or customers, and the bundling of commercial and non-commercial products, while a non-cost disadvantage could be application of stricter regulation to government-owned businesses, such as adherence to stricter safety standards or the requirement to provide more product information (IPART, 2023, p. 90[41]).

Non-cost advantages and disadvantages do not affect the cost base but are still a competitive neutrality concern because they change the relationship between SOEs and privately-owned businesses. The preferred approach to these is to remove them. However, if this is not possible, it may be possible to impute a monetary value derived from them. If this is not possible, adjustment could involve adding an arbitrarily determined premium to costs to represent advantages or a discount to reflect disadvantages.

Annex Box 6.A.1. Examples about cost allocation methods

EDI Post (EDI) is a division within Australia Post. EDI specialises in the electronic acceptance, preparation and printing of invoices, statements, accounts, cheques and direct mail from high-volume business mailers. Mailhouse services are the major product line within EDI. In its transactional mail business, EDI competes with a range of private mailhouses. It was alleged inter alia that in relation to its mailhouse services, EDI was not competitively neutral because it priced below commercial rates and it derived an advantage in the market because it had access to information about the mail volumes of competitors’ clients. EDI is not a stand-alone government business; rather, it operates within Australia Post. Whether its operations are competitively neutral depends on whether it bears an appropriate share of Australia Post’s common costs. Australia Post was found to allocate the cost of centrally provided services based on each activity’s proportion of use, consumption and/or occupancy which was accepted as consistent with competitive neutrality.

Docimage Business Services (DBS) is an in-house competitive tendering and contracting business unit within the Australian Securities & Investment Commission (ASIC). DBS provides documentary imaging services to a variety of Commonwealth agencies, as well as to other organisations such as major public and private corporations, private law firms, various universities and local government authorities. In 2001, the Legal Services Association Australia (LSAA) lodged a complaint that DBS was able to undercut its competitors because its prices did not include the full cost of supplying the service. The investigation found that DBS used a fully distributed cost allocation methodology to attribute its share of joint agency costs and that its costs included an appropriate allowance for tax and that it did not receive any advantage in relation to interest. Fluctuations in ASIC’s activities mean fluctuations in its requirement for the supply of services from DBS. DBS uses its document-imaging hardware capacity in excess of ASIC requirements to bid for competitive tenders and contracts. The Australian Government Competitive Neutrality Complaints Office (CCNCO) noted that ‘competitive neutrality does not require pricing that will deliver a commercial rate of return on each and every bid.’ Consequently, so long as ‘DBS’s pricing regime is, in aggregate, successfully recovering all relevant costs including a commercial rate of return, …DBS’s pricing regime is consistent with its obligations under competitive neutrality.’ CCNCO also considered that this allowed ‘ASIC to use its imaging equipment and human resources more efficiently and allowing ASIC to build its expertise in the area of electronic imaging and CD production which, in turn, allows it to better support its core functions.’

Source: Reproduced from Smith, Healey and Bai (2023[40]), Competitive Neutrality: OECD Recommendations and the Australian Experience, Journal of Competition Law & Economics, Volume 19, Issue 2, June 2023, Pages 250–276, https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhad003.

Value of assets

Information concerning the value of the business’s assets may be available through normal government reporting responsibilities and would otherwise require an information request to the government business. Care is to be taken that the principles for valuing government assets correspond with those applied by private sector competitors. For example, if government policy is to value assets based on replacement cost but the private sector values assets based on historical cost, the appropriate valuation basis for achieving competitive neutrality will be historical value (IPART, 2023, p. 85[41]).

Time period

It is inappropriate to measure the rate of return over too short a period. In any given year, full cost recovery may not occur and the target rate of return may not be achieved. Year to year returns will vary, as for private sector businesses, due to factors such as the strength of demand, the level of competition, the competitiveness of the business (e.g. due to degree of technology advantages available to service providers) and market pricing strategies.

Given the year-on-year fluctuation in returns, it is reasonable to expect established government-owned businesses on average to achieve the target rate of return over a 5-year period, while for a start-up government business the period could be set at 10 years, although for highly capital-intensive businesses the period may need to be longer.

Annex Box 6.A.2. Petnet Australia

Petnet Australia Pty Limited (Petnet) was a government-owned body. In August 2011, Cyclopharm Limited (operating in Australia as Cyclopet) complained to AGCNCO that the conduct of Petnet, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), failed to comply with competitive neutrality policy. It was claimed that in a tender for a public hospital supply contract its prices ‘[did] not fully reflect its costs’ and the business ‘[was] not generating commercially acceptable profits.’ In March 2012, AGCNCO issued its finding that Petnet’s business model could not be expected to yield a commercial rate of return over an appropriate period and so was not competitively neutral.

Petnet was established with a small amount of equity from ANSTO, but with most of the start-up finance provided as loans. ANSTO provided Petnet with four loans totalling AUSD10 million between 2008 and 2009, which matured in 2015. In June 2011 (after it had won the NSW Health contract), following a review which found that the financing supplied to Petnet was inadequate, ANSTO entered into an agreement with Petnet to vary the terms of the existing loans and convert them into equity, thereby avoiding the requirement for ongoing interest payments.

In relation to the complaint, AGCNCO stated that ‘[w]hat is relevant for compliance with competitive neutrality policy is the rate of return earned on the total amount of capital invested (recognising that the cost of equity is higher than the cost of debt).’ The financial restructuring of Petnet resulted in ANSTO having an investment of AUSD 17.228 million in Petnet. This provides the denominator for assessing the rate of return from the contract with NSW Health. It was necessary for AGCNCO to determine:

the appropriate rate of return that should be achieved on this investment; and

the period within which this should occur.

ANSTO originally stated that the payback period was 10 years but later increased it to 15 years, claiming it better reflected the useful life of the cyclotron machine.

The expected rate of return on investment in Petnet was 13.5%. However, ANSTO admitted that this was unlikely to be achieved, but not because its conduct was not competitively neutral. AGCNCO found that Petnet’s expected internal rate of return over 10 years was around 5.3%, well below the weighted average cost of capital. Over a 15-year payback period, Petnet’s commercial rate of return was found to be 9.2%, still well short of the 13.5% target of ANSTO. AGCNCO concluded that ‘[r]evenue and expenditure forecasts over 10 and 15 years demonstrate that PETNET Australia’s commercial operations are unlikely to achieve a commercial rate of return on the equity invested over either time period.’ Its conduct was found to be an ex-ante breach of competitive neutrality policy.

Source: Australian Government Competitive Neutrality Complaints Office (2012[42]), PETNET Australia, Investigation No. 15, https://www.pc.gov.au/competitive-neutrality/investigations/petnet/report15-petnet.pdf.

References

[36] Ahlborn, C. and D. Piccinin (2009), “Bank restructuring aid in the financial crisis”, Oxera Agenda, http://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Bank-restructuring-aid_1.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

[22] Australian Government (2004), Competitive Neutrality Guidelines for Managers, https://www.pc.gov.au/about/core-functions/competitive-neutrality/2004-competitive-neutrality-guidelines-for-managers.pdf.

[42] Australian Government Competitive Neutrality Complaints Office (2012), PETNET Australia, Investigation No. 15, https://www.pc.gov.au/competitive-neutrality/investigations/petnet/report15-petnet.pdf.

[34] Autoridade de Concorrencia (2021), The Role of Competition in Implementing the Economic Recovery Strategy, http://www.concorrencia.pt/sites/default/files/2021-AdC-contribution-on-economic-recovery.pdf.

[37] Boudghene, Y. et al. (2010), “The Dexia restructuring decision”, Competition Policy Newsletter, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/cpn/2010_2_11.pdf.

[8] CNMC (2022), Informe relativo a las ayudas concedidas mediante el plan MOVES III, PRO/CNMC/003/21, http://www.cnmc.es/sites/default/files/4111236.pdf.

[7] Criscuolo, C. et al. (2022), “Are industrial policy instruments effective?: A review of the evidence in OECD countries”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 128, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/57b3dae2-en.

[38] Department for Business & Trade; Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2022), Subsidy Control rules: quick guide to key requirements for public authorities, http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/subsidy-control-rules-key-requirements-for-public-authorities/subsidy-control-rules-quick-guide-to-key-requirements-for-public-authorities (accessed on 8 March 2023).

[28] European Commission (2021), Temporary Framework for State Aid Measures to Support the Economy in the Current Covid-19 Outbreak - Consolidated Version, C(2021) 8442 of 18 November 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/competition-policy/system/files/2021-11/TF_consolidated_version_amended_18_nov_2021_en_2.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2022).

[10] European Commission (2009), Common Principles for an Economic Assessment of the Compatibility of State Aid under Article 87.3, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/reform/economic_assessment_en.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2022).

[25] European Commission (2008), Commission Notice on the application of Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty to State aid in the form of guarantees, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52008XC0620%2802%29.

[27] European Court of Justice (2017), Retegal, Case C‑70/16 P, ECLI:EU:C:2017:1002, https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=198062&pageIndex=0&doclang=en&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=10734571.

[24] European Investment Bank (2022), What drives firms’ investment in climate action? Evidence from the 2021-2022 EIB Investment Survey, https://doi.org/10.2867/048422.

[14] European Union (2021), Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/PE-46-2022-INIT/en/pdf.

[31] Fontoura Gouveia, A. and C. Osterhold (2018), “Fear the walking dead: Zombie firms, spillovers and exit barriers”, OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 13, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6c6e51d-en.

[12] Goolsbee, A. and A. Krueger (2015), “A retrospective look at rescuing and restructuring General Motors and Chrysler”, NBER Working Paper 21000, https://www.nber.org/papers/w21000.

[26] Government of Canada (2021), Universal Broadband Fund, https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/high-speed-internet-canada/en/universal-broadband-fund.

[6] Hancher, L. and F. Salerno (2021), “Chapter 4. State aid in the energy sector”, Research Handbook on European State Aid Law, pp. 64-86, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789909258.

[4] IMF et al. (2021), Subsidies, Trade, and International Cooperation, http://www.elibrary.IMF.org.

[41] IPART (2023), Competitive Neutrality in New South Wales - Final Report, https://www.ipart.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/cm9_documents/Final-Report-Competitive-neutrality-in-NSW-May-2023.PDF.

[11] JFTC (2016), Guidelines for Public Support for Revitalization in view of Competition Policy, https://www.jftc.go.jp/en/pressreleases/yearly-2016/March/160331_files/160331_2.pdf.

[13] OECD (2023), “Government support in industrial sectors: A synthesis report”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 270, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1d28d299-en.

[2] OECD (2023), “Measuring distortions in international markets: Below-market energy inputs”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 268, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b26140ff-en.

[3] OECD (2022), “Competition, Subsidies and Trade”, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/subsidies-competition-and-trade-2022.pdf.

[5] OECD (2022), Government support and state enterprises in industrial sectors, https://one.oecd.org/document/TAD/TC(2022)9/FINAL/en/pdf.

[15] OECD (2022), Monitoring the Performance of State-Owned Enterprises: Good Practice Guide for Annual Aggregate Reporting, http://www.oecd.org/corporate/monitoring-performance-state-owned-enterprises.htm (accessed on 12 May 2022).

[19] OECD (2021), Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in Ukraine in 2020, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/AR(2021)55/en/pdf.

[32] OECD (2021), Fostering economic resilience in a world of open and integrated markets, http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/OECD-G7-Report-Fostering-Economic-Resilience-in-a-World-of-Open-and-Integrated-Markets.pdf.

[1] OECD (2021), “Measuring distortions in international markets: Below-market finance”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 247, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a1a5aa8a-en.

[21] OECD (2021), OECD Competitive Neutrality Reviews: Small-package delivery services in ASEAN, http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-competitive-neutrality-reviews-asean-2021.pdf.

[33] OECD (2021), State Support to the Air Transport Sector: Monitoring developments related to the Covid-19 crisis, http://www.oecd.org/corporate/State-Support-to-the-Air-Transport-Sector-Monitoring-Developments-Related-to-the-COVID-19-Crisis.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2023).

[16] OECD (2021), “The promotion of competitive neutrality by competition authorities”, OECD Global Forum on Competition Background Paper, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/the-promotion-of-competitive-neutrality-by-competition-authorities.htm.

[30] OECD (2020), “The effects of R&D tax incentives and their role in the innovation policy mix: Findings from the OECD microBeRD project, 2016-19”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 92, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/65234003-en.

[35] OECD (2020), The Role of Competition Policy in Promoting Economic Recovery, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/the-role-of-competition-policy-in-promoting-economic-recovery-2020.pdf.

[29] OECD (2015), Taxation of SMEs in OECD and G20 Countries, OECD Tax Policy Studies, No. 23, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264243507-en.

[18] OECD-GVH (2020), “Competition Policy in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Focus on Competitive Neutrality”, OECD-GVH Regional Centre for Competition Newsletter, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-gvh-newsletter15-july2020-en.pdf.

[9] Oxera (2017), Ex post assessment of the impact of state aid on competition, European Union, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/reports/kd0617275enn.pdf.

[17] Regional Economy Vitalization Corporation of Japan (REVIC) (2023), Company Profiles, http://www.revic.co.jp/en/about/index.html.

[39] Robins, N. and H. Geldof (2018), “Ex Post Assessment of the Impact of State Aid on Competition”, European State Aid Law Quarterly, Vol. 17/4, pp. 494–508, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26694276.

[23] Robins, N. and L. Puglisi (2021), The market economy operator principle: an economic role model for assessing economic advantage, Edward Elgar Publishing, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789909258.00009.

[40] Smith, R., D. Healey and X. Bai (2023), “Competitive Neutrality: OECD Recommendations and the Australian Experience”, Journal of Competition Law & Economics, Vol. 19/2, pp. 250-276, https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhad003.

[20] WTO (2021), Notification Provisions under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures - Background Note by the Secretariat, G/SCM/W/546/Rev.12, https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/G/SCM/W546R12.pdf&Open=True (accessed on 8 May 2022).

Notes

← 1. Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Official Journal 115, 09/05/2008 P. 0091 – 0092, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A12008E107.

← 2. (OECD, 2022[3]) discusses the effects of state support on trade and competition.

← 3. With reference to the WTO framework, local-content requirements confer benefits that are prohibited.

← 4. Supporting firms in distress keeps in the market inefficient firms and distorts competition. For this reason, any such support should be subject to significant scrutiny. For instance, in the European Union there are specific Guidelines on State aid for rescuing and restructuring firms, OJ C 249, 31.07.2014.

← 5. In the same opinion, the CNMC carefully examined the requirement imposed by some regions to purchase cars from local suppliers as a condition for the financial support to buy electric cars. Therefore, consumers are not free to choose any car supplier and the CNMC considered it as a restriction on competition. The CNMC recommended to avoid such unjustified geographical limitation.

← 6. More precisely, this concerns measures which have been found to fall under Article 107(1) of the Treaty, i.e. aid incompatible with the internal market.

← 7. The balancing between the beneficial effects of the aid and its negative effects is not required for aid that aims to “remedy a serious disturbance in the economy of a Member State”, under Article 107(3)(b) TFEU. This is because the result of the balancing is presumed positive: “the fact that a Member State manages to remedy a serious disturbance in its economy can only benefit the European Union in general and the internal market in particular.” (see the judgement of the General Court of 17 February 2021 in Rynanair vs. European Commission, Case T‑238/20, https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?dir=&docid=237881&doclang=en&mode=req&occ=first&pageIndex=0&part=1&text=).

← 8. According to the Voluntary Standard “large” “is defined based on thresholds established by national authorities in a given jurisdiction or as established in applicable international/multilateral/bilateral agreements”.

← 9. Article 25 of the SCM Agreement.

← 10. The EU Regulation on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market (article 3) includes in the definition of subsidies not only granted by governments and public entities, but also those provided by “a private entity whose actions can be attributed to the third country, taking into account all relevant circumstances”.

← 13. See Article 34 of “The Act on Regional Economy Vitalization Corporation”, available in Japanese at https://www5.cao.go.jp/revic/pdf/houan.pdf.

Article 15, paragraph (2) Item(i) and (Article 15,) paragraph (5) Items (i)(a) and (i)(b) of “Ordinance for Enforcement of the Act on Regional Economy Vitalization Corporation”, available in Japanese at https://www5.cao.go.jp/revic/pdf/houan.pdf.

← 15. European Commission Decision of 1.12.2020, Case SA.61340 – Pricing model proposed for guarantee schemes under the SNGM (Sistema Nacional de Garantia Mútua), https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases1/202132/294366_2304860_57_2.pdf.

← 16. The European Commission notes that a measure is State Aid if it has four features: “(1) there has been an intervention by the State or through State resources which can take a variety of forms (e.g. grants, interest and tax reliefs, guarantees, government holdings of all or part of a company, or providing goods and services on preferential terms, etc.); (2) the intervention gives the recipient an advantage on a selective basis, for example to specific companies or industry sectors, or to companies located in specific regions; (3) competition has been or may be distorted; (4) the intervention is likely to affect trade between Member States.” Source: https://ec.europa.eu/competition-policy/state-aid/state-aid-overview_en (accessed on 22 October 2021).