This chapter reviews Colombia’s creative districts policies. A pioneer in the OECD, Colombia’s national creative district strategy encourages subnational governments to develop cluster-based competitive advantage in the creative economy to support local development. The Ministry of Culture is helping build local government capacity to govern, finance and administer districts. In rural areas and less populated municipalities, heritage-based districts are growing, though governance challenges exist. Mainstreaming creative districts into local policy agendas is an opportunity to harness them for development. Municipal funding drives districts revenues, though financial diversification needs are growing.

Culture and the Creative Economy in Colombia

3. Creative district policy in Colombia

Abstract

In Brief

A pioneer among OECD countries, Colombia introduced a national strategy for creative districts, known as Orange Development Areas (ADN). When an ADN is declared through local legislation, Colombian law can provide district investors with a deduction in an investor’s tax base equal to 165% of the amount invested or donated. Creative districts encourage territories to draw on broader policy planning and reflect strategically on comparative advantage. In 2022, 96 ADNs existed in 50 Colombian municipalities.

National capacity building tools accompany subnational governments as they develop creative districts. The Orange Economy Nodes and Tables strategy accompanies local governments to build inclusive governance systems. Creative Agendas serve as roadmaps for local governments to develop the ecosystem around districts.

Some districts are specialising, while other focus on leveraging spillovers between value chains in different sectors. In Cali and Ibagué, ADNs La Licorera and Capital Musical strengthen municipal support around existing clusters in the performing arts and music respectively. In Bogotá and Medellín, meanwhile, ADNs such as the Science, Technology and Innovation ADN or the Perpetuo Socorro districts, respectively, aim to stimulate innovation across sectors.

ADN policy allows municipalities facing socio-economic challenges to deepen strategic thinking on the links between tourism and cultural heritage. 35% of ADN’s declare cultural, heritage or environmental tourism as their main purpose. In San Jacinto, Bolívar, Colombia the Ministry supported the creative district by providing musical instruments, recording equipment and teaching materials through the Music in Movement programme. Valledupar, Cesar has developed three ADNs to attract tourists to heritage sites, drawing private financing.

Based on international practices, the following policy perspectives emerge as ADNs develop:

Local governments seize the opportunity brought by creative districts, but strengthening links with municipal policy may offer synergies between policies and reinforce policy continuity. Encouraging district inclusion in dedicated municipal culture plans may help foster long-term strategic thinking around ADNs. Inter-municipal cooperation may be an opportunity to embed districts in department-level planning, and coordinate strategy more broadly.

Governance design is an opportunity to further include creators, investors and citizens in district development. Initial data on ADNs reveals artist representatives are rarely involved in district management, with national and municipal governments driving decision-making.

ADNs are an opportunity to drive cultural participation through local actions. ADNs could be encouraged to integrate specific cultural participation plans into their broader strategies to increase citizen participation in ADN activity.

Diversifying financial resources available to districts could provide greater financial sustainability. According to a survey of Colombia’s districts, 23% listed external financing as the area of greatest focus, the highest of any priority. Tailoring Colombia’s tax incentive for creative districts may offer avenues to provide more adapted offering to local entrepreneurs and investors. Stronger links with existing creative economy instruments offers further perspectives.

3.1. Why creative districts?

Cultural and creative sectors tend to “cluster” in certain places, and these clusters can promote local growth. Cultural and creative clusters tend to arise in certain locations where there is a history of cultural and creative practice or a strong cultural heritage, which is further reinforced by institutional governance (Lazzeretti, Capone and Boix, 2012[1]). These clusters often build organically on existing competences and the image of a location to attract further talent, building dense networks of cultural and creative workers and firms, which benefit from agglomeration effects, such as shared infrastructure, knowledge spillovers and a dynamic labour pool, supported by freelance creative workers (Scott, 2006[2]). While creative clusters tend to be associated with large cities and urban areas, smaller “microclusters” can also be found in rural and peripheral areas, with recent research suggesting that the determinants of clustering is broadly similar for both urban and rural geographies (Velez et al., 2022[3]).

Governments can encourage the formation of creative clusters through targeted strategies and the formalisation of creative district policies. Formal creative districts differ from more general creative clusters in that they generally refer to neighbourhoods or areas which benefit from some form of policy recognition or intervention in their maintenance or development. Much like in broader creative clusters, creative districts can drive local regeneration, create wealth and jobs, contribute to place making and have positive spillover effects (such as knowledge and innovation) to other industries through social networks, labour mobility and supply chains.

Cities and regions have been experimenting with creative district policies for decades. In the past the most prominent local culture-led regeneration initiatives were often designed around a high-status cultural institution (e.g. a museum or theatre). With greater recognition of the economic and social impact of cultural and creative sectors, many local governments increasingly focus their regeneration strategies around the development of cultural and creative districts as spaces for creative production. Strong institutional support and a tailored approach to creative district policy is fundamental to developing either cultural amenity led or industry led creative district programmes (Santagata, 2002[4]).

Local governments can use a range of mechanisms to support creative district policy (OECD/ICOM, 2019[5]). This includes investing in cultural infrastructure, affordable housing requirements, subsidising rents on workshop space in cultural districts for artists, artisans, and designers, and aligning innovation, start-up and business development services to the needs of creative sector professionals. These efforts aim not only to support an innovative work force, but also to change the identity of the place as creative and modern, attracting further talent and investment. In addition, recognition of the benefits of cultural participation has led many local governments to seek to widen access to and participation in the arts, support local cultural production, and utilise arts and heritage to strengthen community identity. For example, local governments in many cities have turned vacant properties into community cultural centres, funded arts education, and stimulated interest in local heritage and culture.

Creative districts can transform local areas, but there are also risks associated with their development. Projects that lead to a large increase in tourism or that cater to high-income consumers may have negative effects. Without proper planning, these and other factors can contribute to population displacement and gentrification and the crowding out of artists and creative sector professionals through increased property and rent prices (Zukin and Braslow, 2011[6]; Cameron and Coaffee, 2005[7]). Moreover, while strong cultural heritage in a region or city represents a significant asset, over commercialisation or “commercial misappropriation” of local cultural heritage can be deeply damaging to local communities (UNESCO and The World Bank, 2021[8]). These risks need to be tackled by both local governments and cultural and creative stakeholders to ensure that cultural district policies keep the local community, artists and creative sector workers at the heart of regional or city life.

3.2. Creative districts in Colombia

Colombia has pioneered creative district development as part of a national creative economy policy. Creative districts have grown across OECD countries as knowledge, creativity and innovation-based development strategies have gained increasing recognition as drivers of local development. In Colombia, the formation of creative districts, or “Orange Development Areas” (Áreas de Desarrollo Naranja - ADN), was a core element of the Orange Economy policy and its role in Colombia’s broader 2018 – 2022 National Development Plan (PND) (DNP, 2018[9]). The PND emphasizes the potential positive economic, environmental and social effects of creative districts. Specifically, the country’s development strategy recognises districts’ potential to advance urban renovation, economic agglomeration effects, entrepreneurship, creative employment, tourism, heritage promotion, environment protection, knowledge transfer, a feeling of belonging, social inclusion and citizen access to culture and creativity (DNP, 2018[9]). The PND defines ADNs as delimited geographic spaces recognised through local government instruments or administrative decisions that aim to incentivise and strengthen cultural and creative activities, as defined in the Orange Economy Law of 2017 (Law 1834).

3.2.1. Creative district policy in Colombia

Colombia embeds its creative district strategy within the country’s creative economy policy. Few policy examples exist of countries who have mobilised creative districts in such a systematic way in national policy to achieve creative economy objectives1. In particular, Colombia stands out among OECD countries for using both traditional tools of industrial districts, such as tax incentives, with a policy toolkit that encourages subnational government to take ownership of creative district development. ADNs are seen as an opportunity to congregate people, ideas, industry and policymakers around creative economy projects that promote innovation, raise artist revenues and generate positive impact on urban renewal (Ministry of Culture and Pontificia Javeriana University, 2021[10]).

ADNs enable the dynamics sought by creative economy policy, such as innovation, value chain integration, creative entrepreneurship and urban renewal. Creative districts can be a way to leverage greater socio-economic benefits from a geographic clustering process through links with local policies while helping support creative industry competitiveness. Moreover, creative districts in Colombia build on existing competencies and heritage to promote areas of culture most relevant to local communities. For example, in Cali, the municipal government recognised its rich cultural heritage in traditional Colombian dance, salsa and the performing arts. The municipality opened the La Licorera ADN for dance and choreography, a lever for the region’s cultural attractiveness, and for the urban renewal of the neighbourhood (Ministry of Culture, 2020[11]) (Box 3.1).

By providing a legal framework and presenting policy objectives for districts, Colombia provides policy coherence for its approach across territories. The creative economy is well placed for district-based development as its activities source their competitive advantage from their local social and historic environment (Santagata, 2002[12]). In this way, district policy encourages the consolidation or leveraging of existing clusters of creative activities, giving rise to a diverse group of districts in Colombia. The literature has produced ideal types for creative districts to characterise their diversity within and across countries. The Global Cultural Districts Network (GCDN), for instance, identifies “bottom-up districts”, driven by grassroots actors, and “top-down districts” in which policy drives cluster formation (GCDN, 2018[13]).

Policy recognises that ADN development is within the purview of subnational governments and their local partners. The Ministry of Culture has focused its policy efforts on guidance and advice on municipal regulation, governance and financing of creative districts. ADN regulation specifies territorial legal or administrative instruments as the founding legal basis for creative districts. Subnational legal frameworks for districts can include diverse instruments, such as Territorial Ordinance Plans (POT) or administrative decisions. The place-based dimension of Colombia’s policy reflects local policy responsibilities in heritage preservation, cultural infrastructure, cultural service provision and creative economy development (see Chapter 2).

Two tax deduction instruments stimulate creative district creation. Once an ADN is officially decreed by a subnational government, selected creative economy projects based in ADNs are eligible for the 165% deduction on the investor’s tax base of the real invested or donated value, a tax exemption mechanism established by 2019 legislation.2 Tax incentives can only be awarded to those initiatives included in the 103 International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) codes identified as Orange Economy activities. This tax incentive functions through applications accepted within Colombia Crea Talento (CoCrea), a public-private platform that supports creative economy entrepreneurs, discussed below. The deduction mechanism is not reserved only for ADNs, though projects located within districts receive additional positive consideration when evaluated. Since 2021, this tax instrument is supplemented by a Works for Taxes (obras por impuestos) incentive, in which tax paying natural or legal persons can pay up to 30% of income tax (over the accounting equity of the contributor) and selected taxes as investment in ADNs, with deduction and investment requirements established by law (Republic of Colombia, 2021[14]). This incentive originally applied to those territories most affected by the armed conflict (ZOMAC) and those with high socio-economic vulnerability (PDET).

In 2022, Colombia’s territories had created 96 creative districts. Districts concentrate in departments (departamentos) housing Colombia’s large metropoles, such as Cundinamarca (34 districts) and Antioquia (10 districts)3. Bogotá contains 15 creative districts recognised by local administrative acts or territorial planning instruments. A share of districts have also emerged in rural areas or smaller communities, particularly those in the relative proximity of economic hubs. The geographic patterns of creative district creation in Cundinamarca in particular reflect this trend. Home of the country’s capital, districts in the department have grown in Guatavita, La Mesa, Sopó or Tocancipá, all within 100 km of the capital region. ADNs have emerged in 50 of Colombia’s 1 103 municipalities, revealing a degree of geographic spread.

Box 3.1. In Cali, the La Licorera creative district supports national dance and performing arts

The La Licorera project received State and departmental funding for an urban renovation and competitive cluster project

Cali is the largest city in Colombia’s Valle del Cauca department, bordering the Pacific coast. Cali is known as a hub of performing arts, such as traditional Colombian dance, represented in a host of festivals, such as the Festival of Salsa, the Festival Mercedes Montaño - Danza for folklore dance, Delirio, Ensálsate, the Guacarí dance festival and the biannual international of dance in Cali. Digital and audio-visual arts as well as fashion are other local strengths to lean on for ADN development. The city houses three ADNs.

The La Licorera dance and choreography centre is a pillar of the ADN’s activities. La Licorera seeks to develop a cultural and creative ecosystem for dance and the performing arts, while preserving local tradition. The Ministry of Culture played an important role in its development, investing COP 15 463 million, in addition to funding from the Valle del Cauca government and the national tourism fund, FONTUR. The investment helped convert an abandoned winery into a centre for training, circulation of and entrepreneurship in dance.

State investment in La Licorera may also reflect strategic intention to develop Cali’s clusters as part of Colombia’s international competitiveness in the performing arts. This approach has already shown results. In 2022, for example, the city hosted “Cali Distrito Moda 2022”, an international fashion industry event.

Source: (Ministry of Culture, 2019[15]), Se inaugura 'La Licorera', el centro de danza y coreografía más importante de Latinoamérica, https://www.mincultura.gov.co/prensa/noticias/Paginas/Se-inaugura-La-Licorera-el-centro-de-danza-y-coreograf%C3%ADa-m%C3%A1s-importante-de-Latinoam%C3%A9rica.aspx.

3.2.2. National policy builds on the prior experience of subnational governments in Colombia

Creative district policy builds on growing attention to cultural and creative sector clusters in Colombia, particularly through activity in Bogotá. In 2021, the Bogotá city council passed local legislation promoting creative districts as city-wide policy4. The capital launched the Bronx Creative District in 2018, with a strong emphasis on urban renovation. Planning around the city’s science, innovation and technology district, also declared as an ADN, also began in 2009 (Bogota D.C., 2022[16]). The Ministry of Culture’s guide for creative district creation was partially based on a roadmap developed by the Bogotá municipal government, reflecting the city’s early engagement in creative districts (Ministry of Culture, 2020[17]). In 2021, the capital city inaugurated a network among the city’s 15 creative districts, known as the District Network of Creative Districts.

Creative district policy finds synergies with city-level efforts to develop creative economy clusters. The UNESCO Creative Cities Network reflects efforts made in Colombian cities to promote specific creative economy clusters. Since 2004, this UNESCO network allows cities to participate in international knowledge sharing around municipal creative activity, and converge around good practices. Eight Colombian cities are members of the network for different clusters, including Popayán and Buenaventura for gastronomy (2005, 2017), Bogotá, Medellín, Valledupar and Ibagué for music (2012, 2015, 2019, 2021), Santiago de Cali for digital art (2019), and Pasto for crafts and popular art (2021).

3.2.3. Public policy encourages subnational governments to develop districts as drivers of local development

Cognisant of structural inequalities between municipal administrations, Colombia leveraged the Nodes and Tables strategy as a governance tool to reinforce local capacity to plan and manage ADNs.5 Within the multi-level governance framework brought by Nodes, municipalities are encouraged to create adapted governance structures. Involvement from actors across the quadruple helix are a supporting factor for the long-term sustainability of districts by bringing diverse input for financially, socially and environmentally balanced development (see Box 3.2). To meet these objectives, the Ministry of Culture developed a step-by-step guide for local governments when implementing ADNs (Ministry of Culture, 2020[17]). The Ministry of Culture encourages local governments to take the following steps:

Identify tools that give legal force to ADNs and strengthen delimitation and implementation;

Quantitative sectoral diagnostic;

Registration of cultural and creative economic activities;

Capacity evaluation of cultural assets on-site;

Cluster delimitation;

ADN declaration;

Strategies and instruments for district governance;

Defining priority projects and creative agendas;

Monitoring and evaluation throughout ADN development.

Creative Agendas have yielded a host of department-level roadmaps which encourage Nodes to reflect strategically on ADN position within a wider policy agenda. In Bucaramanga, Santander’s Creative Agenda, for example, the ADN Centro Fundacional Bga is recognised as housing the city’s principal administrative services, while integrating activities related to tourism, museums, editing and a historic core for the city (Ministry of Culture and Santander Orange Economy Node, 2020[18]). Bucaramanga’s Manzana Creative Cluster and Metropolitan Tourism ADN, meanwhile, sees the creative district as part of an ongoing effort to create a touristic hub in the city around the Municipal Arts Schools (EMA) and a cultural centre for eastern Colombian culture. Creative Agendas also encouraged subnational governments identify synergies with competiveness and innovation agendas, tourism corridor projects or registered industrial clusters (Ministry of Culture, 2021[19]).

For ADNs, Nodes and Agendas are an opportunity to develop inclusive governance structures and reinforce the local ecosystem. The dialogue instigated by Nodes between members of the quadruple helix can generate the base for a governance structure to formulate Agendas, and in turn, an inclusive administrative structure for a creative district. ADNs are also a place where actors within and outside the creative economy can exchange, learn and develop joint initiatives that rely on synergies between different parts of the value chain. The State’s role in Nodes and Tables, often through direct representation in Nodes structures, could help link ADNs with broader Orange Economy opportunities. Nodes can function as relay channels to inform entrepreneurs and help them access national creative economy opportunities. The role of the Nodes strategy and Creative Agendas as part of the broader Orange Economy policy is described in Chapter 2.

Box 3.2. Colombia introduced a multi-dimensional idea of district sustainability

Sustainability entails recognising the capacity a district requires to meet its objectives over the long-term

In 2021, the Ministry of Culture worked with the Pontificia Javeriana University to provide renewed capacity building efforts to Colombia’s ADNs. The Ministry of Culture and its university partners define creative district sustainability as the capacity to create, promote, and above all, maintain activities and results in time, aiming to maintain the cultural values and traditions of a community.

Sustainability allows creative districts to foster educational programmes, generate revenue and catalyse urban and environmental renovation to the benefit of ADN stakeholders. Colombia adapts a Global Cultural Districts Network (GCDN) framework to creative district development over time, highlighting the importance of a (i) cultural and creative, (ii) social and educational, (iii) infrastructure and (iv) economic dimensions.1

Colombia has introduced capacity-building tools to local government to accompany its holistic sustainability model. In 2021, the Ministry of Culture identified a sustainability roadmap for (Ruta para la Sostenibilidad) creative districts, which presents a series of monitoring indicators for district governance, cultural and creative, social and educational factors, infrastructure and economic activity. These indicators are to be measured throughout a district’s development, from its structuring phase through to consolidation.2 The Ministry complemented these indicators with a capacity-building toolkit and field activities for the country’s ADNs. For instance, in November 2021, the Ministry and its university partner organised sustainability workshops for ADN administrators. This approach reflects the country’s unique countrywide approach to creative district policy among OECD countries.

1. The government’s sustainability approach draws on the “values” model suggested by the Global Cultural Districts Network (GCDN), in which artists, educational, social-communitarian, urban-environment and economic value form five impact streams for districts to provide balanced and encompassing impact on the community (GCDN, 2021[59]).

2. A statistical database is available online with indicators on dimensions such as developmental stage, legal structure, financing source. See: Sostenibilidad de las ADN en Colombia, https://economianaranja.gov.co/reportes/.

Source: (Ministry of Culture and Pontificia Javeriana University, 2021[10]), El proyecto de Fortalecimiento de Áreas de Desarrollo Naranja, Convenio de asociación n°. 4407 de 2021 suscrito entre el Ministerio de Cultura y la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, https://economianaranja.gov.co/media/uytl3jco/informe_adn_javeriana.pdf.

3.2.4. The Nodes strategy complements the Ministry of Culture’s regional development initiatives to reduce capacity gaps for ADN development

The Ministry of Culture engages in regional development policy more broadly. The Ministry of Culture benefits from a dedicated Deputy Minister for Regional Development and Heritage, reflecting attention placed on culture’s potential to create jobs, formalise work and draw investment to economically disadvantaged territories. ADN development in rural areas and smaller municipalities faces obstacles, such as high levels of informality or poor infrastructure, structural challenges that can also inhibit other policies. In certain cases, subnational government officials may not have the experience or resources to forge private sector partnerships, invest municipal budgets strategically in ADNs or communicate with citizens on ADN opportunities.

Staff from across the Ministry of Culture regularly consult and advise subnational governments. The Ministry develops joint working plans with local authorities, propose Ministry tools and deliver information on the creative economy through the Regional Development Information System (SIFO). For example, the Ministry of Culture supported San Jacinto by mobilising capacity-building programmes from across the Ministry’s policy portfolio. In its regional development mission, the Ministry can mobilise policy tools reserved for territories affected by armed conflict (ZOMAC), such as specific funds and capacity building instruments. In San Jacinto, he Ministry of Culture provided the ADN with musical instruments, recording equipment and teaching materials for the cultural centre through the Ministry’s Music in Movement (Música en Movimiento) programme, which has donated musical production equipment to 236 municipal music schools throughout Colombia (Ministry of Culture, 2021[20]). San Jacinto also benefits from a School Workshop (Escuela Taller) programme, known as the Living Museum (Museo Vivo), where visitors can see local crafts people at work, reflecting synergies achieved between Colombia’s traditional cultural programmes and district policy.6

3.2.1. Some subnational governments are mainstreaming ADNs in their policy agendas, though opportunities exist to generalise efforts across Colombia

Some subnational governments in Colombia have integrated creative districts in wider municipal policy. In Bogotá, creative districts are a pillar of the capital’s public policy for the cultural and creative economy 2019-2038. In 2021, the city also founded the District Network of Creative Districts, aiming to tighten cooperation between the city’s creative districts and the organisations that support their development. In Medellín, the Perpetuo Socorro ADN is a policy tool within the city’s Development Plan 2020-2023 “Medellín Futuro” to consolidate the creative economy ecosystem and improve quality of life (Medellín City Hall, 2020[21]). Similarly, Bucaramanga’s Manzana 68 district has embedded its district plans into its Decadal Culture and Tourism Plan.

As districts mature in Colombia, the inclusion of districts in municipal planning instruments can help ensure all policy synergies are explored. These tools also support district continuity can be supported across political cycles. Municipal planning instruments can include decadal culture plans, as well as economically-focused creative economy policy.

3.2.2. Colombian districts are specialising and leveraging spillovers, while districts in rural areas and smaller municipalities harness heritage for tourism

Most Colombian districts house a diverse set of cultural and creative sectors. In Bogotá, in particular, the capital is home to a diverse set of cultural and creative sectors. The capital city has developed twelve ADNs, while the department of Cundinamarca, which houses the capital, contains 34 districts. For instance, the city’s Science, Technology and Innovation ADN, still under development, will seek to generate spillovers between technology-intensive sectors and the cultural and creative sector to generate new value added for the creative industries. In Evigado, Antioquia, the Innovation Valley ADN, another innovation-centred district, gathers over 1 500 enterprises from across the cultural and creative sectors. These exampes also show how Colombian municipalities have made use of ADN legislation to support existing clusters of creative industries. Similarly, in Medellín, the Perpetuo Socorro district gathers entrepreneurs from a range of sectors, ranging from the visual and performing arts to marketing. The Perpetuo Socorro project also involves a strong urban renovation dimension.

In some cities, existing clusters of creative industries leverage a single or targeted group of sectors. Ibagué, Tolima developed an ADN based on an existing cluster of musical activities. The ADN Capital Musical, for example, is a 25-hectare area in the city’s historic centre, including the landmark city institutions such as the Tolima Theatre, the Music Park and the Tolima music conservatory. The ADN is part of the city’s branding as a music capital, and complements broader municipal government activities such as the city’s musical agenda. In Cali, the La Licorera ADN is similarly anchored around development of dance and the performing arts. The district redeveloped urban spaces into performing arts spaces for a host of activities related to different value chain dimensions, such as learning, research, production circulation and entrepreneurship. The focus of such districts centres on leveraging a clustering effect from within a sector or smaller group of sectors to draw on synergies within a value chain or the potential to engage larger markets.

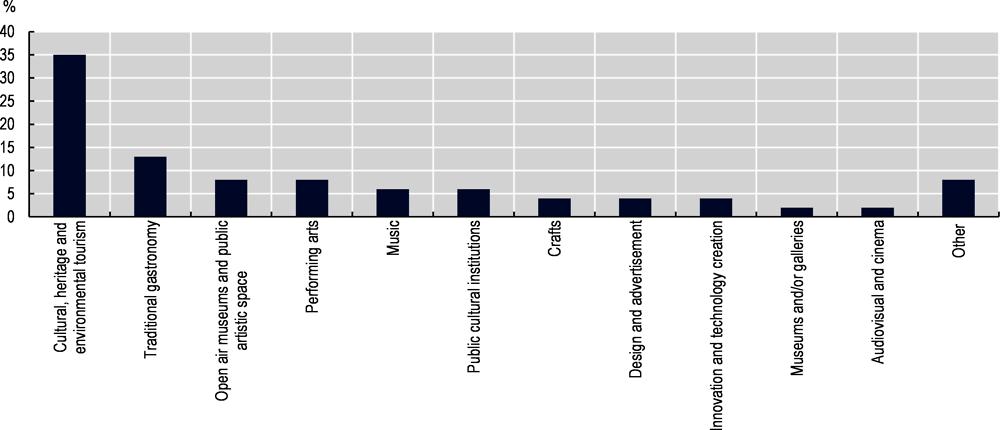

Outside major cities, local heritage and tourism tend to lead creative district specialisation. Indeed, data released by the Ministry of Culture reveals 35% of ADN’s declare cultural, heritage or environmental tourism as the main vocation of their activities, the most common specialisation for districts after traditional gastronomy, at 13% (Figure 3.1). The high share of districts in this category may reflect the large number of less populated municipalities or peripheral areas that have seized the opportunity to introduce a creative district in their town. The high share of heritage-driven districts may also reflect the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism’s Cultural Tourism policy, which has placed emphasis on the potential of heritage-based tourism (Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, 2021[22]).

Figure 3.1. Tourism leads among creative district missions in Colombia

District policy allows smaller municipalities to deepen strategic thinking on the links between tourism and cultural heritage. In Villa del Rosario, Norte de Santander, the municipality has inaugurated multiple ADNs dedicated specifically or partially to heritage-based tourism, including supporting the workforce’s skills in traditional crafts. The old town ADN (Villa Antigua) valorises and renovates the town’s historic heritage sites. A district in the municipality’s Piedecuesta neighbourhood complements the old town ADN with its historic colonial-era architecture. In the Juan Frío area of the municipality, another ADN has been activated, with a focus on both cultural tourism and traditional manufacturing activities. Many small districts are seizing districts as opportunities to further spillovers between craft production, heritage valorisation and tourism. In Juan Frío, the area is also a memorial site for the victims and those resisting paramilitary violence during the armed conflict, reflecting the role districts can play to fulfil post-conflict memory objectives.

In the country’s northern Cesar department, Valledupar, reflects heritage-specialisation in a context of economic and social challenge. Valledupar is listed among the country’s municipalities for Territorially-Focused Development Programmes (PDET). PDETs are 15-year national territorial development instruments designated to 170 selected municipalities most affected by violence, poverty, drug trafficking and institutional weakness. Valledupar has created three ADNs within the municipality, all reflecting strategically on driving tourism around cultural heritage clusters. The Old Valledupar (Viejo Valledupar) ADN draws on the town’s historic heritage designation as a Site of National Cultural Interest Site (Bien de Interés Cultural Nacional) and local vallenata musical tradition to attract visitors. The ADN also involves efforts to restore historic buildings. The municipality’s Paths of the Valley (Caminitos del Valle) district has been declared in a natural and cultural crossroads near the Guatapurí river, benefiting from a host of institutions such as the Popular University of Cesar, the Rio Luna events centre and a park. Finally, the Confidences ADN (Confidencias) has been formed around a cluster of gastronomic activities near Novalito park.

Both broader innovation based clusters and more sector specific clusters are encouraged to connect to the wider business community in the local area. Partnerships with local business clusters are an opportunity for ADNs to generate new connections between value chains (Ministry of Culture and Pontificia Javeriana University, 2021[10]). Integrating creative businesses within the wider business ecosystem can stimulate innovation through knowledge exchange and crossover projects. Moreover, raising the profile of cultural and creative businesses within the wider business community can help drive business to business (B2B) sales and promote the use of creative skills and talent across the local economy.

3.2.3. Districts offer spaces for cultural participation

Community participation in creative districts helps ADNs strengthen access to cultural rights. Literature on system-wide cultural districts highlights education of the local community and local citizen involvement as conditions to generalise participation in culture and create a district that is sensitive to change (Sacco et al., 2013[23]). Empowering the local community to learn, communicate and share their territory may help a creative district root itself in a shared vision (Nuccio and Ponzini, 2017[24]). District engagement by the local community may also help citizens reap the social benefits of culture, such as those increasingly documented related to health, wellbeing and social inclusion (WHO, 2019[25]).

In Colombia, cultural participation is best levered when ADNs collaborate with civil society and seek the buy-in of the local community. 14% of ADNs in Colombia declare their main objective as the creation of a physical meeting space for residents around local customs and traditions, while 12% of ADNs state their main goal as the creation of spaces for artistic and creative education7. These orientations rank as the fourth and fifth most common objectives for ADNs, revealing an intent among districts to foster cultural participation. This is facilitated when districts build on existing institutions, such as a popular festival, educational institution or artistic facility with ties to the community. In Barranquilla’s Barrio Abajo ADN, for example, participation in the district is favoured by links to the city’s festival, and co-construction of the district’s agenda in open public meetings.

Districts can also lean on partnership with social policies such as health, social protection or youth strategies to tie participation to positive cross-overs. In Tunja, Boyacá, the Biocultural Cuna de Conocimiento ADN engages artists to centre the district around the town’s experimental theatre (Teatro Experimental de Boyacá) and cultural activities for the community, generating spaces for expression and exchange (Ministry of Culture and Pontificia Javeriana University, 2021[10]). In Bucaramanga, Santander, the Manzana 68 Creative and Touristic Metropolitan Cluster ties musical education with health services, fostering a local hub for innovation in music-based therapy. The district embeds its project within the orientations of Bucaramanga’s Decadal Culture and Tourism Plan. Such vanguards offer examples for replication or inspiration elsewhere in Colombia, where links with community-based institutions may reinforce local participation.

3.2.4. Governance models are consolidating, though some local governments require support

Colombia’s creative districts make different choices around governance. Colombia’s Ministry of Culture defines ADN governance as the capacity through which those quadruple helix actors involved coordinate and take decisions related to their objectives and mutual interest (Ministry of Culture and Pontificia Javeriana University, 2021[10]). No one-size-fits all model exists to include all stakeholders in the decision-making process. ADNs governance frameworks are influenced by the administrative or legal structure they are given when they are created.8 The Global Creative District Network (GCDN) also highlights the important role of political dynamics in explaining a district’s governing structure, and the importance of partnership-oriented governance models, anchored in a place’s creative ecosystem (GCDN, 2018[13]). Local settings shape the conditions under which creative district governance takes form in Colombia. Geographic location, financial resources available, objectives of an ADN, leadership and local capacity all influence choices about which actors to involve and the specific structures used to govern a local district.

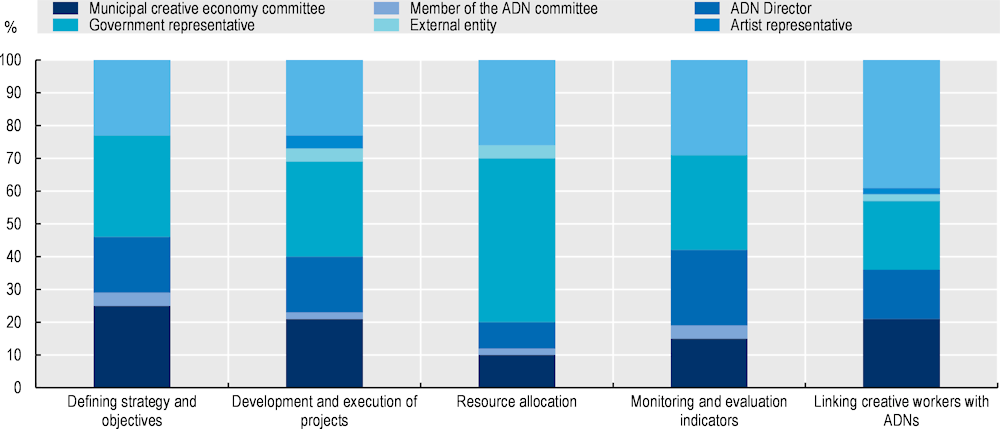

Due to the strong policy drive behind ADNs, creative districts in Colombia tend to be led by local government. The publicly-led model of district governance is common in Bogotá, where the municipality has been a major impetus behind the development of creative districts throughout the city. In other cities in which districts have grown, such as Bucaramanga, Cali or Ibagué, municipalities also lead district development. Data collected by the Ministry of Culture and a partner university also suggests the national government is involved across ADN governance areas, taking decisions related to resource assignation in 50% of districts and project development in 29% of districts (Figure 3.2). Municipal governments, through local creative economy committees, take decisions related to strategy definition and project development in 25% and 21% of ADNs respectively. These findings demonstrate the high level of national and municipal government involvement in district development. Artist representatives, meanwhile, are rarely involved in district decision-making across surveyed ADNs. Although a sign of initial policy uptake and strong policy links, the low share of ADNs with strong artist engagement may reveal a need to strengthen links with local creative communities.

Figure 3.2. Municipal and national government are involved in district governance across areas

Note: Percentages reflect the share of creative districts surveyed in Colombia in which the labelled actor takes the decision.

Source: Ministry of Culture. https://economianaranja.gov.co/reportes/.

In smaller towns and rural territories, municipalities are also actively engaged in governance. Municipal governments are well placed to lead district development in these areas due to their responsibility for promoting and preserving cultural heritage, a major creative economy activity in smaller cities or peripheral areas. For example, in Villavicencio, Orinoquía, the Centro Gramalote ADN is housed partially within public municipal buildings. The district emphasizes urban renovation, development of local trades, social participation, and links with heritage protection plans. Because of its strong focus on heritage and location within municipal buildings, public actors play a frontline role in its governance, including the Ministry of Culture, multiple local government departments, the Meta regional infrastructure agency, the department’s tourism institute, the SENA regional office and the municipal cultural corporation (CORCUMVI). Municipally led districts also benefit from close links to public financial opportunities, such as the Ministry of Culture’s grant schemes (see Chapter 4).

Self-organisation by entrepreneurs or civil society can play a greater role when a cluster of creative activity already exists and civil society takes a leadership role. Prior to the creation of Medellín’s Perpetuo Socorro district, for example, the arrival of the Mattelsa fashion company prompted creative economy organisations to agglomerate in the area. The city’s Family Compensation Fund, Comfama, and the Pontificia Bolivariana University further supported firm clustering. The organisations helped form the Perpetuo Socorro Corporation, a PPP which helped give rise to an ADN in the neighbourhood. In Salmona, Caldas, the University of Caldas has played a forefront role in the creation of the town’s creative district. The Faculty of Arts and Humanities provided the impetus for the districts, in collaboration with the Faculty of Engineering, highlighting the role that can be played by universities.

In many ADNs, still in their early stages, district governance is an ongoing process set to consolidate as local governments engage stakeholders as districts develop. Policies have helped local governments create inclusive governance structures for ADNs, though little experience with districts and weak capacity can still challenge some territories. Nodes and Creative Agendas have helped local governments enter district development with the backdrop of existing dialogue between quadruple helix actors. As districts exit their initial growth phases, more formal inclusive administrative structures may help districts ensure their continuity. International examples offer a host of examples for Colombia’s ADNs to follow, ranging from formal public-private governance boards or direct municipal administration, to community or member-led models where neighbourhood organisations take the lead.

3.2.5. High municipal funding for ADNs reflects strong policy take-up, though greater diversification can reinforce sustainability

The high level of municipal resources devoted to ADNs reflects strong policy take-up. In Colombia, districts have adopted different financing models, reflecting the diversity that exists across OECD countries. In Colombia, initial data on ADNs shows over two thirds of district revenue comes from public sources (Ministry of Culture, 2022[26]). According to the same source, 40% of district revenues comes from municipal government, 17% from the national government, 7% from departmental governments and 6% from public culture applications.9 The high level of municipal resources, particularly in ADNs early stages, may be a sign of strong interest in creative districts by subnational governments across the country. Business represented 10% of ADN revenues, while 4% of revenues were generated by capital provided by enterprises within districts and 3% from district events.

The publicly oriented financial structure of creative districts likely reflects ADNs legal structure. Colombia’s PND 2018-2022 states ADN must benefit from an established administrative act to gain the ADN label, and accompanying tax incentive eligibility. Indeed, 96% of ADNs have links with municipal cultural departments, 94% have links with the municipal government as a whole, while 89% benefit from links with the local tourism office.10 Links with local government helps ensure financial sustainability, particularly through the operation of public institutions onsite (i.e. universities, national training office, etc.) or public investment in cultural infrastructure.

Diversifying financial resources available to districts can provide greater financial sustainability. Indeed, among ADNs, finding external sources of financing for district development is one of the primary concerns. According to Ministry of Culture data, 23% of districts listed external financing as the area of greater focus, while 21% declared the primary effort to be promoting the competitiveness of local products and services (Ministry of Culture, 2022[26]). The potential to diversify funding outside municipal public sources is tied to factors such as location, ADN strategic orientation, leadership and network, member finances, the attractiveness of local goods and services to investors, and interest in drawing alternative forms of financing, such as philanthropic or crowdfunded donations (see Chapter 4).

In Colombia, some ADNs reflect higher levels of private financing. The Old Valledupar ADN (Viejo Valledupar) in Valledupar, Cesar, focuses on drawing visitors to experience its heritage sites, traditional music and local gastronomy. A high flow of tourism and strategic alliances with the local chamber of commerce, business groups and the family compensation fund, COMFACESAR, likely contribute to its financial situation. Deepening private partnerships may be a medium to long-term process for those districts with weaker networks and relative geographic isolation from investment centres. Strategic governance choices, for instance with the business community within the department, may be a particularly important step for the private or philanthropic sector actors to take stock of revenue potential, but also districts’ contribution to culture and creativity. Crowdfunding may constitute another avenue to attract funding from a larger pool of investors and donors, and showcase a district’s ability to draw funding prior to seeking larger private investors.

The group of funding instruments introduced by the Orange Economy policy may be an opportunity to diversify funding. Some steps have already been taken through existing programmes, such as within the National Stimulus Programme (PNE), which has allocated grants specifically to strengthening ADNs. Securing funding for grant-based artistic activity within ADNs can also contribute to district cultural and creative sustainability. This year, those ADNs that received grants benefited from COP 40 million.11 CoCrea applicants located on ADNs or requests for debt financing could benefit from tailored capacity building as part of the creative district sustainability roadmaps. Internationalisation, for example through closer ties to ProColombia’s creative economy programmes, also presents an opportunity to export ADN products and services or attract investment and visitors.

3.3. International creative districts: policy options for Colombia

3.3.1. Guadalajara’s digital creative city benefits from strong articulation with municipal and national polices

In 2010, the federal Mexican government helped drive policy momentum for the creation of Guadalajara’s Digital Creative City district, (CCD) in Guadalajara, Mexico. The creation of the CDD district was created as part of broader policy efforts to promote Mexico’s audio-visual sector. Mexico’s policy sought to include a place-based element to its policy through the creation of a globally oriented district. Mexico’s federal government organised a countrywide call for proposals. Guadalajara, the capital of Mexico’s State of Jalisco, was selected among eleven applicant cities.

Guadalajara developed the district around Parque Morelos, where the municipal government could mobilise public property. According to its institutional plan, the selected zone was a good fit for the development of a creative district due to the physical heritage located within the neighbourhood, as well as infrastructure well adapted to the growth of a digital hub (Agencia para el Desarrollo de Industrias Creativas y Digitales del Estado de Jalisco, 2019[27]). A “Master Plan” (Plan Maestro) was developed for the creative district by international experts, which acted as an action-plan for district development. The plan also considered the social-spatial dimension of the CCD, including its potential to reshape living styles and the urban fabric, and also commissioned a social impact evaluation study.

Guadalajara’s CCD reflects a multi-actor policy approach to creative district creation. Indeed, although the Mexico federal government drove its creation, mobilising political and economic capital, the district was able to materialise and grow through municipal government support and buy-in from actors from actors across sectors. Different government bodies were created to systematise stakeholder buy-in and governance (Ulloa, 2017[28]). For example, actors created a dedicated fund, a directing committee chaired by the federal government’s Ministry of Economy and a regional government agency with responsibility over the CCD, the Agency for the Development of the Creative and Digital Industries in Jalisco. University and education and training actors have also been involved in the project, now providing digital skills programmes linked to the CCD (Agencia para el Desarrollo de Industrias Creativas y Digitales del Estado de Jalisco, 2019[27]). The CCD 2019 institutional plan highlights that the CCD has helped draw prestigious institutions to the site, such as the Laboratorios Pisa and Tec de Monterrey. The Jalisco government, however, highlights challenges such as a relative investment gap to meet objectives and a degrading social situation around the CCD.

The CCD may provide lessons for Colombia’s ADNs for stronger articulation between local competitive advantage and the State’s industrial policy. The CCD’s development echoes federal policy to promote Mexico’s media sectors, such as audio-visual production. In Colombia, national coordination among the country’s 96 districts may reinforce articulation between national industrial policies, such as the array of policies supporting Colombian film production, and district policy concerning local clusters. Bogotá’s city-wide District Network of Creative Districts may also serve as an example for creating a central knowledge-exchange and coordination framework on a national scale.

3.3.2. Barcelona’s 22@ innovation district encourages spillovers between value chains

In 2000, Barcelona’s local government approved plans to build an innovation district within the Poblenou neighbourhood, a former industrial area. The plans were centred around reactivating the area through a new agglomeration of different knowledge-intensive sectors, R&D and education institutions (Barcelona City Hall, n.d.[29]). The government sought to attract knowledge-intensive industries to 22@, with a particular focus on creative industries, such as design, publishing, and multimedia sectors. The municipality’s vision for the district imagined a high level of interaction and synergy between the remaining industrial enterprises in the neighbourhood and new knowledge-intensive arrivals. Physical and digital infrastructure construction constituted a major investment to attract target enterprise, such as a fibre optic network, a new electrical distribution network and underground galleries to transit between buildings12. To support the project’s social objectives, social housing construction and public transportation were also included in renovation plans.

22@ has yielded results. Today, over 1 500 media, IT, energy, design and research companies operate in 22@, with many companies lodged in former industrial buildings that have been refit for the needs of knowledge-intensive companies (Barcelona City Hall, n.d.[30]). Although the local government funds infrastructure related to the district’s development, the private sector has a primary role in support 22@ financially. 22@ has contributed to shaping the city’s image and economic weight as a hub for ICT. In 2019, the ICT sector accounted for nearly 60 000 jobs in the city, representing 5.5% of all employment (Collboni, 2020[31]).

22@Barcelona functions under a flexible adaptive governance system, in which members of the quadruple helix all participate. Government, companies, academia and NGOs, dialogue and compromise within a central committee, the 22@ Office (Gianoli and Palazzolo Henkes, 2020[32]). The 22@ Office liaises with the City Council.

@22 has also accompanied the city’s strong engagement to attract talent, such as foreign students, researchers and professionals. City planning recognises talent as a driver for social innovation and competitiveness in the global marketplace (Collboni, 2020[31]). Indeed, as part of its Barcelona Green Deal strategy for future development, the municipality will open an International Welcome Desk Centre within @22 space, a “one-stop-shop” for international professionals to facilitate administrative procedures and access social opportunities. For ADNs, articulation with talent attraction may be an opportunity to come, especially for those districts housing universities or training institutions.

@22 is an example of mainstreaming an innovation district within municipal policy. Although @22 is not dedicated solely to creative activity, the district may be a reference for Colombia’s technology and innovation-focused ADNs, such as Bogotá’s innovation district or Medellin’s Perpetuo Socorro. Anchoring the district’s in all dimensions of municipal policy, such as public transit, FDI attraction and social housing, all support the value chain integration and social interaction that help districts flourish.

The @22 district’s evolution, through greater sensitivity to the green transition, social issues or the needs of the digital economy, also reveals the importance of policy learning to Colombia’s districts (Barcelona City Hall, 2020[33]) In 2020, for instance, Barcelona published a new strategy for the district based on a citizen consultation started in 2017. New initiatives include adapting the district’s urban regeneration strategy, driving innovation, expanding the governance structure to new actors and heritage preservation efforts. As ADNs develop, holding regularly citizen consultations, and adapting district policy to new priorities supports more resilient districts.

3.3.3. The Quartier des spectacles in Montreal, Québec, Canada, created an inclusive governance model

Launched in 2003, the Quartier des Spectacles (QDS) reflects a district in which artists, academics and non-profit representatives significantly shape the district. The QDS was first proposed by the Québec Association for Disk, Performance and Video Industries (ADISQ), showing the role a sectoral association can play in district foundation. The City of Montreal launched the QDS Partnership in 2003 as a non-profit. The QDS Partnership’s mission has grown over time, now overseeing QDS activities, including programming, public space management and cultural activity.

Local government, however, also helps guide and govern the QDS. Compared to entirely self-operated districts, the QDS partnership gives a significant voice to the municipal government to shape operations. Over 80% of the Partnership’s revenue comes from the Montreal municipal government. Actors from the local municipality, the City of Montreal and Quebec’s Ministry of Culture and Communications sit as observers. The QDS Partnership board is composed of a diverse group of quadruple helix representatives (Quartier des spectacles Montréal, n.d.[34]). Voting board members include representatives from the creative sector, such as the Cinéma Impérial, but also include actors from the University of Quebec in Montreal, KPMG or the Metropolitan Montreal Chamber of Commerce.

For Colombia, the QDS governance structure reflects a sector-led district with strong links with government. Through the inclusion of a host of non-profit, academic and more commercially oriented actors, governance mechanisms need to help facilitate compromises and common strategy. Districts such as the Perpetuo Socorro in Medellín, where private or university actors lead, may be able to turn to the QDS governance framework as they reflect on ways to include local government. Across Colombia, the QDS offers policy options for how to create a governance framework as districts mature.

For its 2022-2026 strategy, the QDS Partnership organised a stakeholder consultation. 350 people participated in the consultation, feeding over 2 000 ideas into strategy brainstorming (QDS Partnership, 2022[35]). Based on the process, QDS produced five axes for future development, including post-COVID recovery, cultural dynamism, territorial planning, synergy creation as well as local and international outreach. Public consultation can be a useful tool for ADNs to democratise district development, and minimise risks associated with urban redevelopment.

3.3.4. The Exhibition Road Cultural Group in London, UK self-operates, while membership fees help fund district activity

The cultural and educational organisations in South Kensington, London, jointly operate and promote its cultural district. Incorporated in 2006, the Exhibition Road Cultural Group (ERCG) is the official partnership charity composed of the neighbourhood’s cultural and educational actors.13 Members of the Road Cultural group largely reflect the scientific, academic and heritage-orientation of the district.

Rather than establishing a creative district through public policy, the Road Cultural helps tighten dialogue within a pre-existing intellectual quarter. The group strives to improve the attractiveness for living, visiting and studying of South Kensington. For ADNs, including neighbourhood attractiveness for living, studying or working can be a way to anchor districts in municipal policy. The Exhibition Road Cultural Group liaises with relevant London municipal authorities on policy issues relevant for the district. In 2020, for example, ERCG supported a planning application to provide step-free access to the district through the South Kensington station (Exhibition Road Cultural Group, 2021[36]). For ADNs, engagement in municipal zoning can help support infrastructure development to increase district access.

The group also plays a lead role in promoting the district’s attractiveness to visitors, students and residents. Chiefly, the group promotes the district by advertising the offering of its different organisations. The organisation also organises district-wide events that help synergise the district’s strengths around common cultural and educational programming. For example, in 2018 and 2019, the group organised the multi-stakeholder Day of Design Festival, bringing together different partners for events supporting the London Design Festival. In 2021, the group helped re-open to district after COVID-19 restrictions. The ERCG is a primary promoter of its cultural institution membership.

A Board of Trustees helps govern the Exhibition Road Cultural Group. Members include representatives from partner organisations, including a representative from the Westminster City Council. A small team of staff and a team of volunteers help run activities. In Colombia, the ERCG model may offers perspectives for ADNs in Colombia where district-based organisations show interest in and capacity for joint governance.

The ERCG raises funds through subscriptions from members, private donations and events organised with partners. The relatively small and member-based governing structure of the south Kensington district reveals a self-governed district with limited involved from local government. For Colombia, membership fees may be an avenue to explore to supplement revenues and tailor membership within districts.

International engagement and peer learning is also a systematic activity of the Exhibition Road Cultural Group. The organisations engages with peer creative districts internationally through the Global Cultural District Network. In Colombia, some districts are already engaging internationally, such as in the Boyacá, where the ADN Biocultural Cuna de Conocimiento has forged links with the academic sector in Mexico and Argentina. Peer learning with international districts may be an activity that can be facilitated by the Ministry of Culture of Colombia through its international network.

3.3.5. A public private partnership governs the West Kowloon Cultural District in Hong Kong, China

Hong Kong, China founded the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority (WKCDA) in 2008 as part of a vision to develop Hong Kong’s cultural sector. The WKCDA is a public-private body tasked planning, developing, operating and maintaining the cultural and creative infrastructure in the WKCD (WKCDA, 2022[37]). The local government’s spearheading role reflects the project’s strong publicly planned vision. The government held consultations with the city’s creative economy actors ahead of construction. Hong Kong, China decided to create a culture and arts-focused district, with facilities such as performing arts infrastructure, an exhibition centre and a museum. The district’s first artistic installation opened in 2019.

The Hong Kong Legislative Council provided initial funding for the high upfront cost for district construction. Hong Kong, China provided the WKCDA with a HK 21.6 billion grant to develop. In addition to the initial grant, funding for the WKCDA is drawn from programming revenue.

Although public sector leadership is a landmark feature of the WKCD, the district governing Authority embodies a shared public and private governance model. The WKCDA is divided into two parts, the Board and the Consultation Panel. The Board functions as the Authority’s executive structure, composed of thematic committees, which recommend policy-specific actions to the Board, and subsidiaries, the companies owned by the WKCDA to execute specific elements of the WKCD’s strategy (WKCDA, 2022[37]). District-owned enterprises are a specific facet of the WKCD that could offer policy perspectives for publicly-led districts to directly operate certain cultural infrastructure, along privately-administered activities. According to the WKCDA website, nineteen individuals sit on the WKCDA board, including a Chairman, Vice Chairman, three government officials and fourteen standard members. Board members include representatives from Hong Kong’s private sector and government. The Consultation panel, meanwhile, is composed of members of the community involved in the local creative economy, ranging from business actors to educational representatives and artists. As Colombia’s districts reflect on ways to involve communities in governance, forming a consultation panel which advises a governing board could be a consideration.

3.3.6. Porto Alegre’s District C is driven by local artists and entrepreneurs

Porto Alegre’s District C was founded in 2013 through the initiative of a start-up. The founding company, UrbsNOVA, delegated district design to the entrepreneurs and artists present in Porto Alegre’s District C (Distrito C, 2022[38]). District C’s mission centres on stimulating interaction between artists, entrepreneurs and their social surroundings. In 2022, the district was composed of over 100 artists and entrepreneurs.

District C distinguishes itself from most creative districts as it does not envision the transformation of the neighbourhood into a sectoral hub. Rather, the district seeks to integrate artists and entrepreneurs into the neighbourhood’s traditional economic activities. The district defines itself as a platform for the interaction of the creative economy, the knowledge economy and the experience economy. Core artistic activities are seen as the foundation of the district’s ecosystem. Beyond its economic objectives, District C also valorises and protects the physical heritage of District C. For many Colombian districts where local economic activities may form a dense cluster of activities, the Porto Alegre model may be an interesting policy option to focus a district on supporting local artistic activity.

District C’s governance model also reflects this vision, empowering local artists and entrepreneurs to govern the district. Members include both private and public organisations located within the district. District C engages in dialogue with the city’s public administration, universities and media. UrbsNOVA envisions District C as an informal organisation based on flexible collaboration (Distrito C, n.d.[39]). District C’s informal organisational model is meant to support, rather than bypass, pre-existing neighbourhood organisations. District planning is organised by its founding company, though the organisations leaves decision-making to district members through regular collaboration on specific actions and general planning. A neighbourhood-led working group offers structure for neighbourhood participation in the project. The District C modle may be a way to formulate or adapt Colombian ADN governance structures to existing organisations that benefit from legitimacy and experience within the community.

Internationalisation is a part of District C’s long term strategy. As other creative districts around the world, District C identifies the opportunities for ideas, talent, market access and investment related to engaging with artists, export markets and investors outside Brazil. As part of this effort, Porto Alegre’s District C is developing a partnership with Barcelona’s 22@ creative district. Bilateral international partnerships that consider foreign market engagement, beyond peer learning, may be a novel method for ADNs seeking internationalisation.

Through “intranalisation”, District C seeks to share its artistic experiences with cities in inland Brazil. To do so, the District provides art donations, organises events and workshops and shares its experience creating an innovation district a model for other cities. District C also engages with public authorities for public art displays and for urban development issues. The district’s inland outreach process may be an interesting policy perspective for Colombia’s urban ADNs which may be well placed to form a strategy to engage with a city’s periphery or surrounding municipalities. In Bogotá, for instance, the city’s 15 districts could consider a strategy to reach out to populations in the capital’s periphery, whose cultural access is rising as a policy priority within local policy planning.

District C has created a sustainable development model through diversified sources of support. District C engages with the city’s government as well as the State for institutional support. The district seeks financial support from private philanthropy, mainly from large companies located within the Direct. The district stresses its contribution to urban renovation and its capacity to attract visitors and investors to attract philanthropic support. To a smaller extent, District C also mobilises crowdfunding, government grants, prizes and donations.

3.3.7. The city government of Buenos Aires, Argentina spearheads the Metropolitan Design Centre, while different tax incentives target diverse actors

The Buenos Aires city municipal government established the Metropolitan Design Centre (CMD) in 2001. The CMD is a fully public institution administered by the municipal government’s Ministry for Economic Development and Production, emphasising the district’s economic focus. Due to its direct policy links, the CMD is embedded within the city’s broader strategy for the design sector. Indeed, the creation of the CMD supported the city’s designation as a UNESCO City of Design in 2005 (British Council, 2011[40]).

The district aims to act as a public policy lever for the economic, social and cultural development of design. The CMD has four missions focused on helping the design’s sector competitiveness and innovative capacity: (i) contribute to the sector’s commercial dynamics, (ii) help design entrepreneurs lever their capacity to innovative and compete, (iii) promote good management in the design sector as a strategic factor for innovation and quality of life and (iv) position the CMD as a global reference point for design.

The CMD, located in Buenos Aires’s Barracas neighbourhood, also works as an urban renovation initiative. Barracas contains a rich social and cultural heritage as the location of one of the city’s historic industrial neighbourhoods as a naval and rail transportation hub. In 2007, the city legislature declared the areas around and within the CMD a historic preservation area.

Municipal legislation introduced a tailored set of tax incentives for the CMD. Law 4761 (2013) institutionalised a tax incentive system for the district’s businesses (City of Buenos Aires, 2013[41]). The beneficiaries of the district’s tax instruments are limited to design-related sectors, defined as design service activities, intensive design activities, CMD infrastructure investors and educational centres. These firms benefit from full or partial exemption from the city’s gross revenues tax (Impuesto a los Ingresos Brutos - IIBB) and exemption from municipal real estate tax. CMD resident initiatives can also benefit from advantageous bank credits from the city’s public bank. Firms benefit from additional tax and fee exemptions based on project and firm specifics. The CMD’s tiered tax incentive system may be a source of policy examples for Colombia to tailor the current tax incentive system, offering adapted opportunities for actors or investors based on district specifics.

The district’s tax incentives are complemented by the CMD’s networking, capacity-building and internationalisation activities. The CMD provides a spaces and encourages interaction and synergies between designers, business executives, academics and public policy practitioners (City of Buenos Aires, n.d.[42]). The district also supports firm internationalisation through global engagement events, such as the CMD’s International Design Festival. The CMD offers a host of start-up incubation, acceleration and a dedicated technology laboratory to provide technical advice to entrepreneurs. The design district also delivers scholarships to connect to vocational education institutions within the district, including textile and furniture schools. Strong use of innovation and internationalisation policies within the CMD may be an example for certain ADNs who are developing a tailored innovation or attractiveness strategy.

The City’s Ministry for Economic Development and Production funds the district’s operations, though private and non-profit investment play a major role in the CMD. Municipal legislation identifies the city’s economic development Ministry as the responsible financial entity. The district complements funding with private investment into the district. For example, the district orchestrated investment from relevant chambers of commerce from the design sector and non-profits to fund and operate training courses in trades within the CMD.

3.3.8. In Dallas, Texas, US, the private sector leads district governance

The Dallas Arts District was established in 1984 as part of municipal efforts to help encourage clustering of the city’s creative industries in the city’s northeast. The district covers over 47 hectares and major institutions from across the cultural and creative sectors, such as the AT&T Performing Arts Center, the Dallas City Performance Hall and the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center. The inception of the arts district offers parallels with Colombia’s Creative Agenda strategy, as the Dallas city government and key sectoral actors reflected strategically on advancing a clustering process in the city based on existing strengths.

The district’s development has been defined by municipal policy coupled with self-organised planning from private or non-profit actors within the district. The Arts District is closely integrated within the Dallas Cultural Plan 2018, which sees the district as a core platform for the city’s cultural policies (City of Dallas, 2018[43]). The Dallas city government continues to support multiple cultural institutions financially within the district, such as the AT&T Performing Arts Center/ATTPAC (DAD, n.d.[44]). Compared to many publicly led creative districts, however, the private sector is a primary mover and planner in the district’s evolution.

The Dallas Arts District (DAD) is a non-profit that champions and stewards the district. The district’s organisations and properties sit on the Board of Direction of the DAD and spearhead its operations. Board membership ranges from major institutions within the district, such as the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, to commercial firms such as Oglesby-Greene Architects or religious organisation located within the district, such as the Guadalupe Cathedral. City development organisations, such as the tourism and investment-promotion agency, VisitDallas, also participate on the board. The municipal government also sits on the DAD board through its Office of Arts and Culture.

The DAD benefits from representation of a host of stakeholder firms, cultural institutions and city development organisations, along with the Dallas City government. Its broad composition helps it propose and advance district development plans. The DAD engages citizens and non-profits outside the arts district through consultations ahead of major planning changes. For example, ahead of proposed municipal zoning changes needed for district development, the DAD organised consultations with local organisations such as Downtown Dallas, Inc., Uptown, Inc. or the Texas Trees Foundation (TTF) and public hearings to receive input.

The DAD and district operations are financed by members, donors, business sponsors and the Dallas municipal government. The DAD also receives financial support from the Texas Commission of the Arts. The district’s financial stability has been supported by a high influx of visitors. A foundation, the Dallas Arts District Foundation (DADF), also contributes to district operations and cohesion, in particular through its DADF grant programme. The DADF has given 450 grants to local creative organisations, representing USD 1.2 million. The DADF also communicates to Dallas residents about district activities and resources. In Colombia, district foundations may be an opportunity to reinvest in district artists through local grant programmes to complement existing national programmes.

3.3.9. The MuseumsQuartier in Vienna, Austria is a State-led initiative leveraging heritage and tourism

The original core of the MuseumsQuartier is based on a dense cluster of heritage sites in Vienna’s city centre. Since its opening in 2001, the forum evolved into a district housing diverse cultural institutions, such as events spaces, theatres and a range of museums. In 2022, the district’s website defines the MuseumsQuartier as a cultural district for artistic creation, new discourses and the circulation of ideas.

The major national heritage status of the MuseumsQuartier has contributed to its position within Austria’s broader policies for the creative and cultural sectors. At inception, the project echoed views to raise the city’s competitive position for tourists and investments (De Frantz, 2005[45]). The neighbourhood’s strong heritage status, contributed to a dialogue, from 1980 to 2001, before an agreement was reached between citizens, government and different stakeholders on the form and evolution of the MuseumsQuartier. The prolonged debate around the use of heritage reflects its role as public goods, which benefit from best use when citizens are involved in their adaptation for economic purposes, such as tourism. The district has evolved to include new activities, such as artist residences and debate spaces. Artist-focused uses of district space are an opportunity for Colombia’s heritage district to diversify the targets for their activities outside of tourism, for example by attracting artists on site through a unique cultural offering. Vienna’s experience with creative districts, as in other examples, also highlights the importance of consultation and buy-in from the public around a heritage district, respecting a community’s connection with and use of a heritage site.

Austria’s federal government provided the initial momentum for the project while involving Vienna’s local government. For example, at its founding in 1980, the agency charged with developing the project (Messepalast Errichtungsgesellschaft) involved 75% State ownership and 25% city ownership. The initial major renovations conducted on the site reflected this fully public model, with the State and the city government providing capital grants and loans to the MuseumsQuartier Company (MuseumsQuartier Errichtungs- und Betriebsgesellschaft). The district also continues to benefit from direct or indirect public funding for its museums and cultural entities, as well as a model benefiting from rent collection from cultural entities leasing premises within the quarter.

3.4. Policy considerations

3.4.1. Local governments lead creative district growth, though links with municipal policy may be leveraged further

Ties to broader municipal policy enable creative districts to support the broader social, urban, environmental or economic objectives. ADNs can function as levers to meet some of Colombia’s structural challenges, such as inequality and poverty. Across international examples presented, creative districts are often major elements of local or regional development strategies. In Montreal, Canada the Quartier des Spectacles is a major element of the city’s cultural policy, while the district is also a focus of policy within the Quebec provincial government. In Barcelona, Spain the @22 innovation district has become a recurrent subject and policy tool in the city’s policy planning documents. In Dallas, US, the arts district is also a centrepiece of broader municipal policy.