In line with Pillar 3 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, this chapter analyses and discusses the capacities and capabilities necessary for a sound digital government policy in Panama. It starts by focusing on the level of priority attributed to the development of different types of digital skills. The chapter focuses in a second section on the policy levers in place to streamline ICT investments in the public sector, namely the use of budgeting capacities, budget thresholds, business cases, project management frameworks and co-funding mechanisms. A section dedicated to ICT procurement in Panama closes the chapter, discussing the efforts necessary to support a shift towards an ICT commissioning approach.

Digital Government Review of Panama

2. Enhancing the digital transformation of the public sector

Abstract

Introduction

As the transformative role of digital technologies becomes mainstream in an increasing number of government sectors, it is rapidly reaching all policy work streams and elevating citizens’ expectations across public service efficiency, inclusiveness, convenience and sustainability. This requires governments to prioritise digital policy planning, design, development, implementation and monitoring. Besides adapting their institutional settings and legal and regulatory frameworks (see Chapter 1), increasing efforts need to be mobilised to strengthen the necessary public sector capacities for seizing the opportunities and tackling the challenges of digital transformation.

In line with Pillar 3 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (2014[1]), a sound digital government policy requires that several building blocks and policy levers are in place to secure the mobilisation and co‑ordination of efforts across the different sectors of governments. One of these is for the public workforce to have the right skills to build upon the opportunities of efficiency, connectivity, openness and intelligence brought by digital technologies. Equally important is a framework of different policy levers, which promote the articulation of policy actions needed to avoid the gaps and overlaps typically brought by siloed and agency-thinking approaches to public investment in digital technologies.

The OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability (2019[2]) also provides a fundamental framework of analysis on how countries can ensure that their public services fit for purpose for today’s policy challenges, and capable of taking the public sector into the future. The Recommendation supports governments on promoting a values-driven culture and leadership, developing skilled and effective public servants and responsive and adaptive public employment systems.

The current chapter will start by analysing the system around digital skills in the Panamanian public administration, focusing on the policy efforts underway for the development of a digital culture across the administration. The analysis will then centre on the policy levers that have already been implemented or for future consideration for co‑ordinated investment in digital technologies that contribute decisively towards a coherent and sustainable policy on digital government. A third and last section of the chapter will be dedicated to the information and communication technologies (ICT) procurement context in Panama and discussing how it can evolve towards a commissioning approach.

Digital culture and skills in the public sector

Digital skills for an empowered public workforce

Skills development is one of the most critical building blocks considered by governments as part of their efforts to enhance the digital transformation. Given the widespread use of digital technologies across the administration, competencies are needed to properly drive the digital change. Technologies are increasingly complex, diverse and with a fast-paced evolution that requires governments to increase efforts to keep the skillsets of public officers updated, but also to anticipate the needs associated with emerging change. More than being reactive, governments increasingly need foresight and anticipatory capacities to manage the competencies and capabilities of the public sector workforce and organise themselves accordingly.

The fast-changing environment where governments operate, has also transformed the needs and expectations of citizens and businesses with regards to how they interact with the public sector and/or can access public services. To address the change underway, a creative, flexible and adaptive public sector workforce with a citizen-driven mindset is required to drive an innovative public sector with the capacity to tackle the disruptive challenges of the twenty-first century and respond to the changing needs.

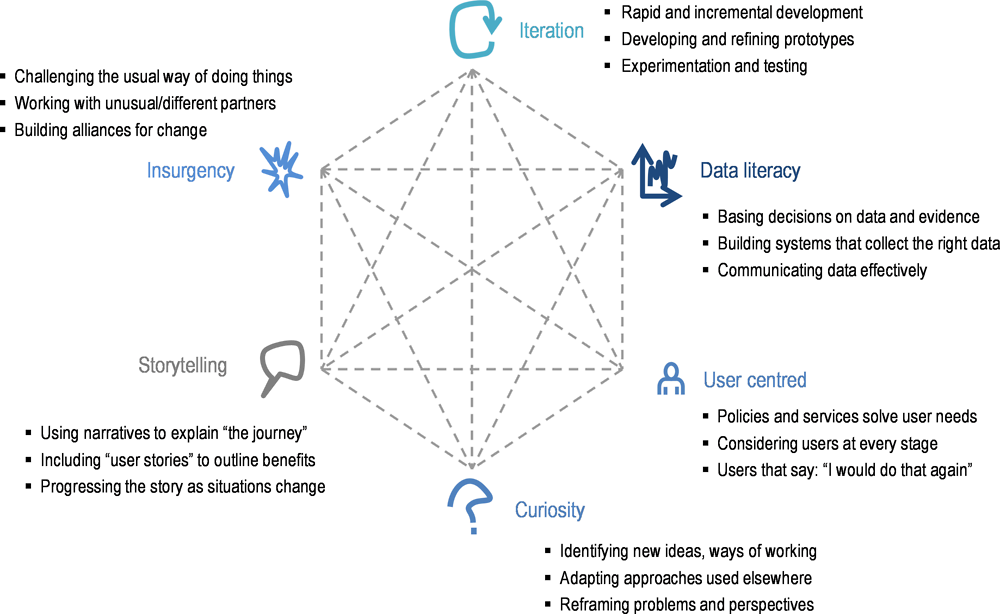

Figure 2.1. Six core skills for public sector innovation

Source: OECD (2017[3]), Core Skills for Public Sector Innovation, https://www.oecd.org/media/oecdorg/satellitesites/opsi/contents/files/OECD_OPSI-core_skills_for_public_sector_innovation-201704.pdf.

Based on research with civil servants involved in innovation projects, activities and teams from around the world, as well as public sector innovation and digital government specialists, the OECD has developed a framework of public sector innovation skills, which groups six categories of skills: iteration, data literacy, user centricity, curiosity, storytelling and insurgency. Although these are not the only skills required for public sector innovation and are not required in every aspect of a public servant’s day-to-day work, embracing or promoting this framework across the public sector can create a more supportive environment for innovation in the public sector (OPSI, 2017[4]).

Considering that the digital transformation is the background for the operation of a more innovative public sector, the aforementioned skills framework represents also the skills that are needed to support the shift from e‑government to digital government highlighted by the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (2014[1]). In other words, a shift from skills that understood technologies as a means to improve efficiency to a digital mind-set and culture where the design of government processes and services embed technologies from the outset in pursuit of more open, collaborative, inclusive, innovative and sustainable policies.

Bearing in mind that going digital is not an option but a requirement of the age we live in , public workforces are increasingly required to embrace and maintain digital skills that can allow them to be part of the digital transformation.

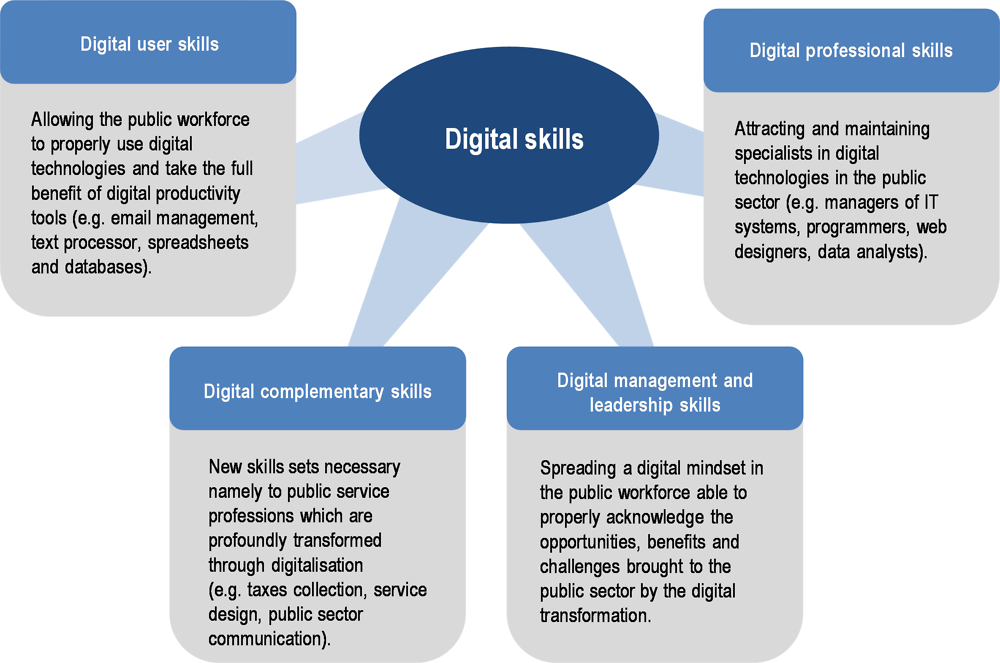

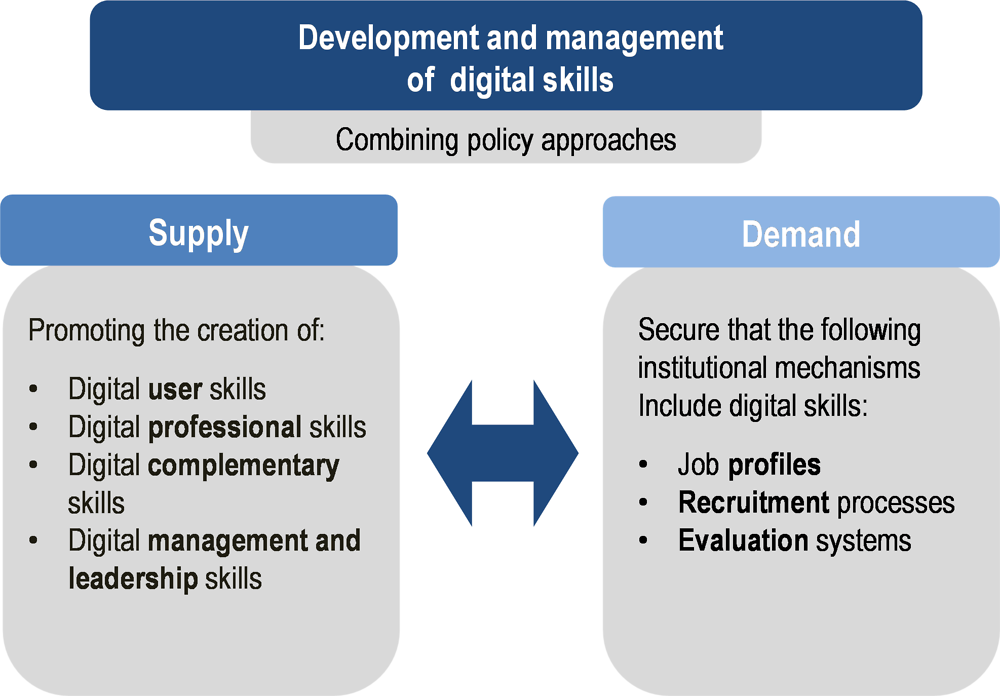

Figure 2.2. Types of digital skills required by civil servants in the context of a digital transformation of the public sector

Source: Author, based on OECD (2017[5]), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

Figure 2.2 illustrates a framework containing four kinds of different skills that should be considered by the public sector to be prepared in driving the change underway. Digital user skills are a requisite in most public sector profiles. Focused mostly on productivity, the ability to use basic digital tools such as word processing, Internet navigation, email communication and even spreadsheets programs are mainstreamed skills for most professions. On the other hand, digital professional skills are also increasingly prioritised given the public sector need to manage and develop its ICT resources. Software engineers and developers, network specialists, enterprise and system architects, data scientists, designers and user researchers, product managers and business analysts are profiles that the administrations need to attract, maintain and keep updated. Digital user skills and digital professional skills are an established part of the policies for the development of e-government for many years and are still the main type of skillsets considered by non-specialised audiences as the necessary skills for the digital transformation.

Nevertheless, as technologies become progressively embedded in public sector activities, new types of skills are emerging and increasingly considered as critical for sound digital government. Digital complementary skills are based on a strong need for dexterity in managing different tools for specific job profiles in the public sector. For instance, tax collection, project management, audit, regulation or communication are activities being profoundly transformed due to the progressive penetration of digital technologies, requiring new digital skillsets for public officers that perform them. In other words, non‑specific ICT related activities today require new skills and competencies to be effectively performed in a digital environment.

In the current environment, the traditional notions of public service leadership, mostly based on legal compliance and bureaucratic process management, need to be reconsidered in order for the senior management to be able to properly embrace and lead the digital transformation. The promotion of a digital culture and a digital transformation mind-set is increasingly recognised as a requirement by senior digital government officials from OECD member and non-member countries. The capacity of a senior public sector officer to understand the digital transformation as a phenomenon that clearly surpasses any technological or technical discussion is fundamental to achieving new stages of digital government maturity in national contexts, in line with the required new leadership capacities expressed in the OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capacity (OECD, 2019[2]). Therefore, the development of a fourth group – digital management and leadership skills – appears to be a priority. It is based on the increasing need of public officers, namely at senior level, to have basic knowledge and awareness about the digital transformation and the opportunities and challenges it offers. In the age of cloud computing, distributed ledgers, artificial intelligence and data analytics, senior public officials are not required to be experts on the use of these emerging technologies and trends, but they need to have a basic understanding of their potential role and impact in the digital transformation process, as they may have to take strategic decisions on related applications or investments..

Digital skills policies in the Panamanian public sector

Attracting, maintaining and developing digital talent in the public sector and properly balancing this approach with outsourced private solutions, commissioning of ICT goods and services and public-private co‑operation, are some of the most critical decisions governments face in a context of digital disruption. Ambitious frameworks of digital skills are increasingly perceived as a key requirement to seize the opportunities and manage the risks of the digital transformation, allowing the public sector to improve its processes and the services it provides to citizens and businesses.

Nevertheless, according to the OECD Digital Government Performance Survey, almost half of the governments of the OECD countries do not have specific strategies in place to attract, develop or retain ICT-skilled public servants (OECD, 2014[6]). While the improvement of digital skills is generally considered a priority by OECD senior digital government officials, there is significant room for improvement in order to achieve coherent and co-ordinated policy actions on this topic.

In Panama, although widely recognised as a priority area by public sector organisations, there seems to exist substantive space to reinforce the digital skills policy for the public sector. Reflecting this sense of priority, specific references to digital skills can be found in the Digital Agenda PANAMA 4.0 (AIG, 2016[7]). Nevertheless, the strategy does not contain a structured approach that can guide public sector efforts in this area.

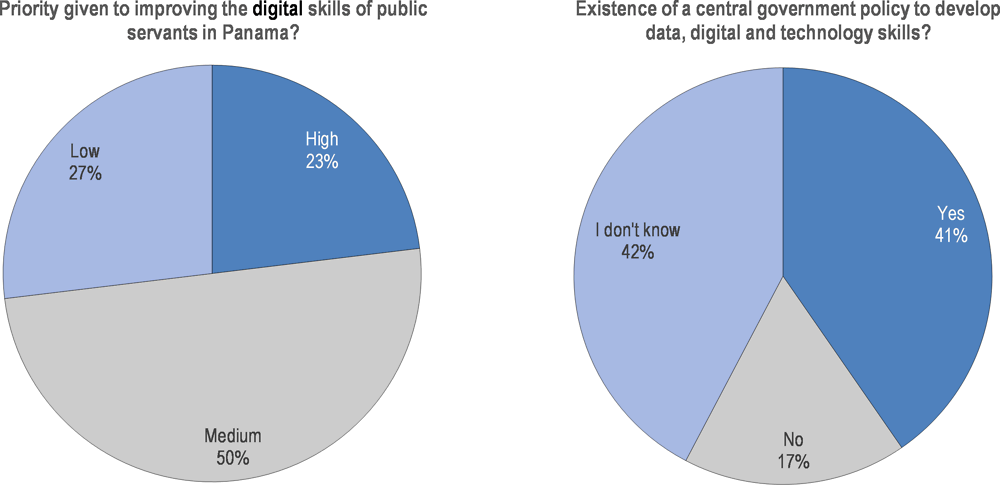

Figure 2.3. Level of priority and acknowledgement of digital skills policy in the Panamanian public sector

Source: OECD (2019[8]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

The results of the Digital Government Survey of Panama appear to be line with the perceptions of the OECD peer review team during the mission. When asked on the level of priority attributed to the development of digital skills of the public workforce only 23% of respondents indicated that they consider it high, reflecting a gap between the perceived need and the effective policy relevance of the topic in the country’s digital agenda. Only 41% of the Panamanian institutions answered in a positive way when asked about the existence of a policy to develop data-related, digital and technology skills in the public sector (Figure 2.3). AIG’s response to the Digital Government Survey of Panama affirms the existence of the policy though its exclusive focus is on the development of digital professional skills (e.g. training programmes organised by AIG) (OECD, 2018[9]).

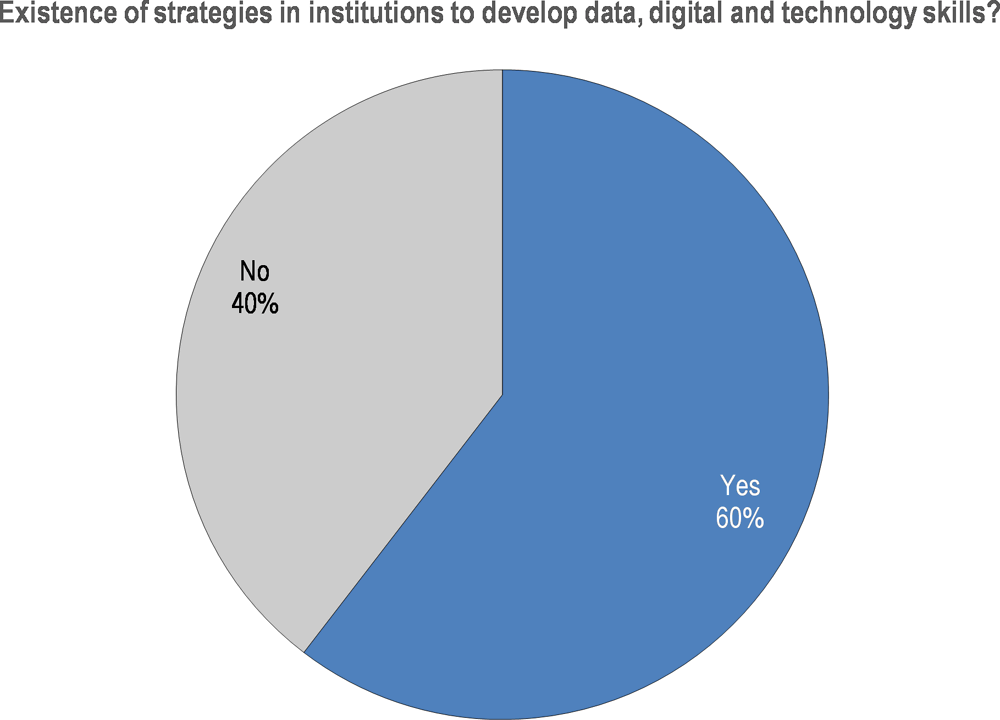

Figure 2.4. Digital skills strategies in Panamanian public sector organisations

Source: OECD (2019[8]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

When questioned about the existence of strategies to develop data, digital and technology skills in their institutions, only 60% of the respondents confirmed the existence of such a policy, demonstrating a significant recognition of the need to develop capacities and capabilities to enhance the digital transformation (Figure 2.4). Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that, based on information collected during the fact-finding interviews made in November 2018 , the practice seems mostly focused on the development of digital user skills through the organisation of capacity-building initiatives.

Additionally, during the interviews, several stakeholders underlined the development of competencies for the digital transformation as a priority for the general population (e.g. through the Infoplazas programme). Although this clear info-inclusion angle is fundamental to promote the use of digital services by Panamanian citizens and can be equally adopted as a priority for the digitalisation of the country, the digital government policy should not minimise the importance of developing skills within the public sector. In order to continue successfully driving the digital transformation of its public sector, the development of the different kinds of digital skills represented in Figure 2.2 would represent an important asset for a sound digital government policy in Panama.

Box 2.1. Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework and GDS Academy in the United Kingdom

Two interesting initiatives from the United Kingdom government can be highlighted focused on the active promotion of digital skills in the public sector

1. Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework

Based in the UK’s Civil Service, the Digital, Data and Technology function supports all departments across government to attract, develop and retain the people and skills to understand and contribute to government transformation. The function works namely on career management, attraction and recruitment, learning and development, and pay and reward.

The Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework describes the roles on the DDaT Profession, helping the civil servants and the civil society to understand the required skills for certain jobs and also work on career progression. Data engineer, IT service manager, delivery manager or software developer are examples of the more than 30 roles identified. The DDaT profession capability framework provides a good example of how a government can better manage digital professional skills in the public sector.

2. Government Digital Service Academy

The GDS Academy offers digital skills courses for specialised and non-specialised professionals. User research, user-centred design, digital and agile awareness for analysts are some of the courses provided in the academy civil servants, local government employees.

The academy acts, in this sense, as an important instrument to disseminate digital skills across the public sector.

Source: GOV.UK (2017[10]), “Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework”,

Managing the supply and demand of ICT skillsets in the public sector

Governments across OECD countries face the challenge of responding to the demand for ICT-qualified professionals within the public sector who are able to manage and respond to the rising needs of the digital transformation of the public sector.

To meet the demand and complexity of some of the activities that require ICT specialised expertise, public sectors may pursue outsourcing approaches for ICT services. These approaches can respond to non‑regular needs of expertise in certain information technology (IT) fields (e.g. develop a website or a specific software application), but also to manage in a more cost-efficient way diverse ICT routine tasks (e.g. user assistance, management of IT infrastructure). Nevertheless, the development of internal ICT professional skills is fundamental to guarantee expertise that can avoid excessive dependence from external ICT providers, a situation that several OECD member and non-member countries’ representatives underline as problematic for the sustainability of digital government development.

Governments need to secure the supply of people with the right skills, providing and promoting the required training and capacity building for the public workforce. But policy action is also fundamental to guarantee that the required demand is in place to absorb the professionals holding the abovementioned digital skills. The absence of demand drivers creates few incentives to improve and take the full benefit of supply-side interventions. In this sense, governments are required to influence the demand through the introduction of the right digital skills in institutional mechanism such as: i) public sector job profiles; ii) recruitment processes; and iii) the evaluation systems in place (OECD, 2018[12]).

Figure 2.5. Digital skills – Supply and demand policy approaches

Source: Author.

The Government of Panama could consider prioritising policy actions that co‑ordinate the supply and demand of skills in the public sector as a way to streamline and reinforce its digital skills policy (see Figure 2.5). Combining and matching policy approaches for digital skills development will provide Panama with more sustainable and mature digital government capacities, allowing the country to continue its ambitious path towards a digitally enabled state. A sound digital skills policy will also support the country in building capacities across the different sectors and levels of government, guaranteeing joint leadership for digital government that can reduce the previously mentioned over-dependency on AIG in the future (see Chapter 1: Embracing strategic policy coherence), and can stimulate a more inclusive, balanced and mature digitalisation process throughout the administration.

Strengthening a digital culture in the public sector

As a fundamental building block to support the rapid digital government development during the last years in Panama, diverse initiatives contributed to improving the skills of Panamanian public officers and improving the general capacities and capabilities across the public sector. Diverse training and capacity building activities were frequently mentioned by different actors during the peer review mission in Panama City in November 2018. Special relevance was given to training activities that could support the use of new software, applications or hardware in specific institutional contexts.

The role of AIG in the development of ICT professional skills is very significant. In the last five years, the Institute of Technology and Innovation of AIG (Instituto de Tecnología e Innovación, ITI) has contributed to the creation, development and updating of ICT capacities across the Panamanian public sector. IT departments, IT governance, enterprise architecture, cybersecurity, management of databases or geographical information systems are just some examples of the training provided by ITI in 2018. AIG has also taken important steps in mobilising e-learning mechanisms to promote capacities across the administration. The E-Learning Project (Proyecto E-Learning) is expanding the Learning Platform of AIG (Plataforma de Aprendizaje) to include relevant ICT courses that can reinforce the competencies of Panamanian public officials. Increasing the number of courses on the platform is one of the current priorities of AIG (AIG, 2018[13]).

To reinforce the ongoing efforts the Panamanian government could consider embracing the reinforcement of digital skills at a broader scale in the public sector as a critical priority for digital government development. The focus should be on the four types of digital skills presented above (Figure 2.2) and particular attention should be given to the following:

3. Promotion of a digital culture across the different sectors and levels of government, supporting the development of a mind-set that properly considers the opportunities and challenges of digital technologies across public processes and services.

4. Reinforcement of a data culture in the administration, that is capable of supporting a public sector that understands data as a critical asset for improved monitoring, forecasting and delivery capacities (see Chapter 3).

5. Development of a delivery culture across the public sector. In a digital age where citizens and businesses are used to the fast development and incredible convenience of services provided by digitally-based providers such as Amazon, Facebook or Google, the delivery of public services needs to achieve new levels of agility (see Chapter 4).

Planning of investments in digital technologies

Policy levers for coherent and sustainable digital government implementation

Given the cross-cutting and progressive digitalisation of all government activities, from automated internal processes to multichannel service delivery, digital investments represent an increasing proportion of central government procurement. Strategic and dynamic planning is required to streamline digital technology investments across sectors and levels of government. The absence or lack of priority given to this critical requirement for the digital transformation of the public sector promotes gaps or leads to duplications in public expenditures, with subsequent losses of efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability.

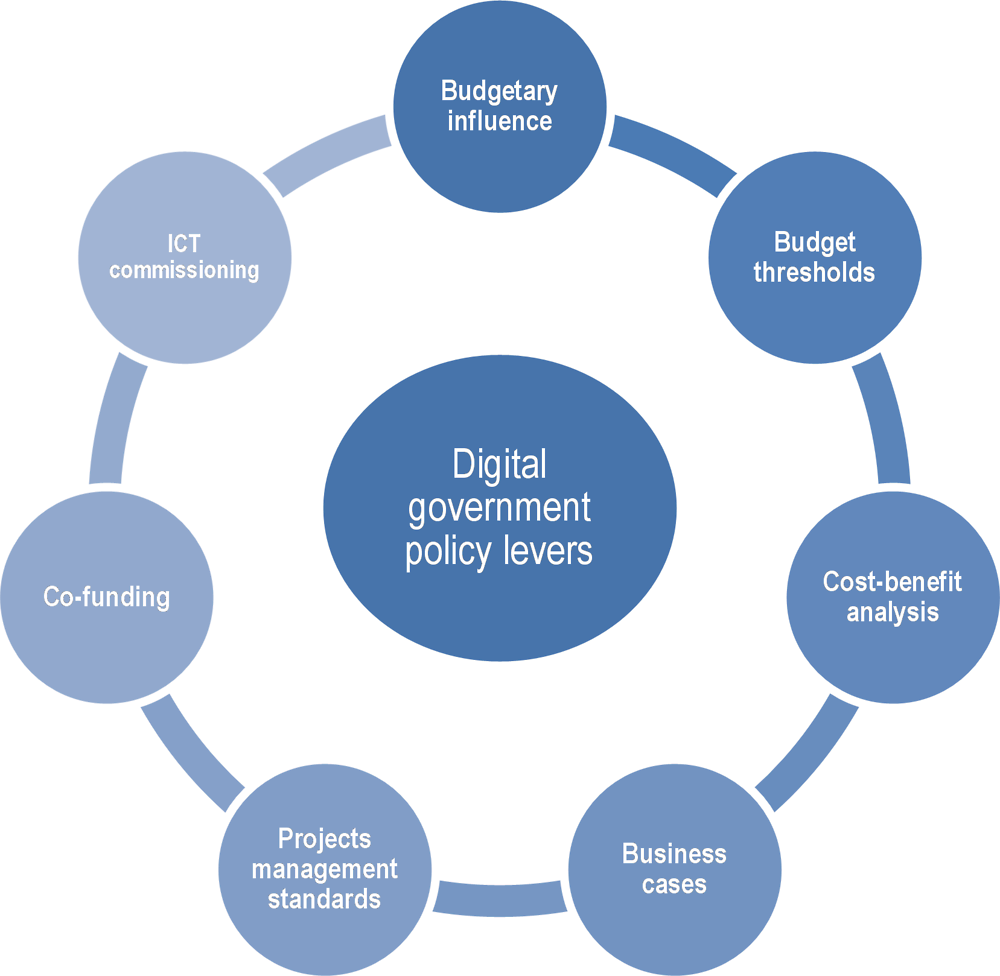

Chapter 1 highlighted the relevance of having a national digital government strategy and the institutional set up securing the leadership and co‑ordination of its implementation, as well as the existence of an updated legal and regulatory framework (see Chapter 1) as important building blocks for effective digital government implementation. Beyond promoting efficiency, the overall co‑ordination and planning of investments in digital technologies can also be an important asset to efficiently implement a national digital government policy, securing the alignment and coherence of public efforts. Governments increasingly recognise the need of having policy levers – including budget thresholds, business cases, agile project management models, ICT commissioning – to drive a coherent policy implementation across sectors and levels of government (see Figure 2.6). The development of institutional tools to plan and present investment projects for digital technologies can assist governments to make effective cost-benefit assessments of public financial efforts. This can help prioritising projects and ensuring the efficiency, effectiveness and alignment of procurement activities through synergies to avoid the gaps and overlaps that typically result from agency-driven approaches.

Figure 2.6. Policy levers for sound implementation

Source: Author.

Digital government policy levers are also fundamental for promoting the use of key enablers across the administration. Besides developing and making critical shared tools and mechanisms available, they can sustain a sound digital government. The effective adoption of these key enablers such as interoperability standards, digital identity frameworks, shared services and open source software is one of the most essential challenges faced by governments of OECD member and non-member countries. By actively promoting the adoption of the enablers through the different policy levers (e.g. accomplishment of interoperability standards and digital identity as a requisite for the approval of investments in digital technologies), governments are reinforcing the implementation capacity of their digital government policies (see Chapter 4: Providing the resources and enablers that support delivery and adoption).

The following sections will explore relevant policy levers and discuss their level of implementation in Panama.

Budgetary influence

The capacity to influence the budgetary priorities of a country and how financial resources are distributed across the administration is a critical mechanism for determining policy implementation. Budgetary procedures in the public sector are typically complex negotiation processes where finite resources are allocated to cover various needs. Different ministries representing numerous policy areas compete to obtain the largest possible share of the potential financial resources. Political influence, the capacity of aligning specific objectives with the broader national policy agenda and even technical expertise are fundamental elements to succeed in this determinant policy process.

Building on the cross-cutting role attributed to the digital transformation of the government, economy and society, and depending on the institutional mandate, attributions and political support, the public sector institution responsible for leading the digital government policy could influence the budgetary distribution of resources. Considering the level of expertise necessary to analyse investments in digital technologies, the government Chief Information Officer (CIO) or the institution responsible for the digital government policy could advise the Ministry of Finance regarding the proposals of budgeting received by the different line ministries. Although some existing examples in OECD countries reflect this practice (e.g. Agency of Digitisation in Denmark and its role in the Ministry of Finance), this policy lever is not frequently used in public administration and sometimes relies on informal mechanisms of consultation rather than in institutionalised practices.

In Panama, considering the high-level political support for the General Administrator of AIG, budgetary influence could be better exploited by the government to shape broader fiscal and planning prioritisation. Given his/her participation in Cabinet meetings (see Chapter 1: Leadership for sound transformation), the budgetary process could be used to strategically promote policy priorities through approval criteria (e.g. delivery of services to citizens and businesses, strengthening institutional digital capacities) and including the involvement of AIG earlier in the national budgetary process.

The suggested approach could reinforce the efficiency and sustainability of national digital government efforts since the budgetary influence of AIG would encourage a systems thinking approach able to contribute to more coherent and sustainable digital government development. An empowered budgetary role of AIG could also generate opportunities for more integrated processes and improved service delivery, starting earlier in the budgetary process and creating also conditions for reinforced transparency and accountability on public sector digitalisation priorities.

Budget thresholds

Centralised mechanisms of pre-evaluation of investments in digital technologies are frequently adopted by countries to reinforce the alignment across the administration. This pre-evaluation is typically supported by the establishment of thresholds for investments in digital technologies above a certain budgetary value. Countries such as Denmark, Norway or Portugal use this effective policy lever to improve the coherence and sustainability of the investments made, enforcing the use of policy guidelines and standards and ensuring the avoidance of gaps and overlaps in the investments.

This policy lever encourages a systems thinking approach that promotes consistent public expenses across the administration, stimulating co‑operation and synergies across the different sectors of government. Moreover, the existence of budget thresholds can improve the transparency, monitoring and accountability of the investments made, allowing not only the government to better oversee in a centralised way the financial efforts made by the administration, but also to create an opportunity for civil society to better track the aforementioned efforts.

The value of the budget threshold varies substantially among OECD member countries and reflects the level of enforcement for efficiency and coherence that the government has in place. The value of the threshold can also reflect more centralised administrative cultures or conversely the greater autonomy of public sector organisations. For instance, while in Portugal the budget threshold is EUR 10 000, in Denmark it is around EUR 1 300 000 (DKK 10 000 000) and in Norway around EUR 1 033 000 (NOK 10 000 000).

In Panama, investments in digital technologies above PAB 50 000 (approximately EUR 44 000) need to be pre-evaluated by AIG. This important mechanism gives the Authority an important policy lever not only to oversee investments made across the administration, but also to influence their alignment with national digital government policy (see Chapter 2: Strategies and co-ordination for ICT procurement). The budget threshold is also an important sign of a culture of evaluation and monitoring in the country, contributing decisively to the digital maturity of the Panamanian governance of digital government experience.

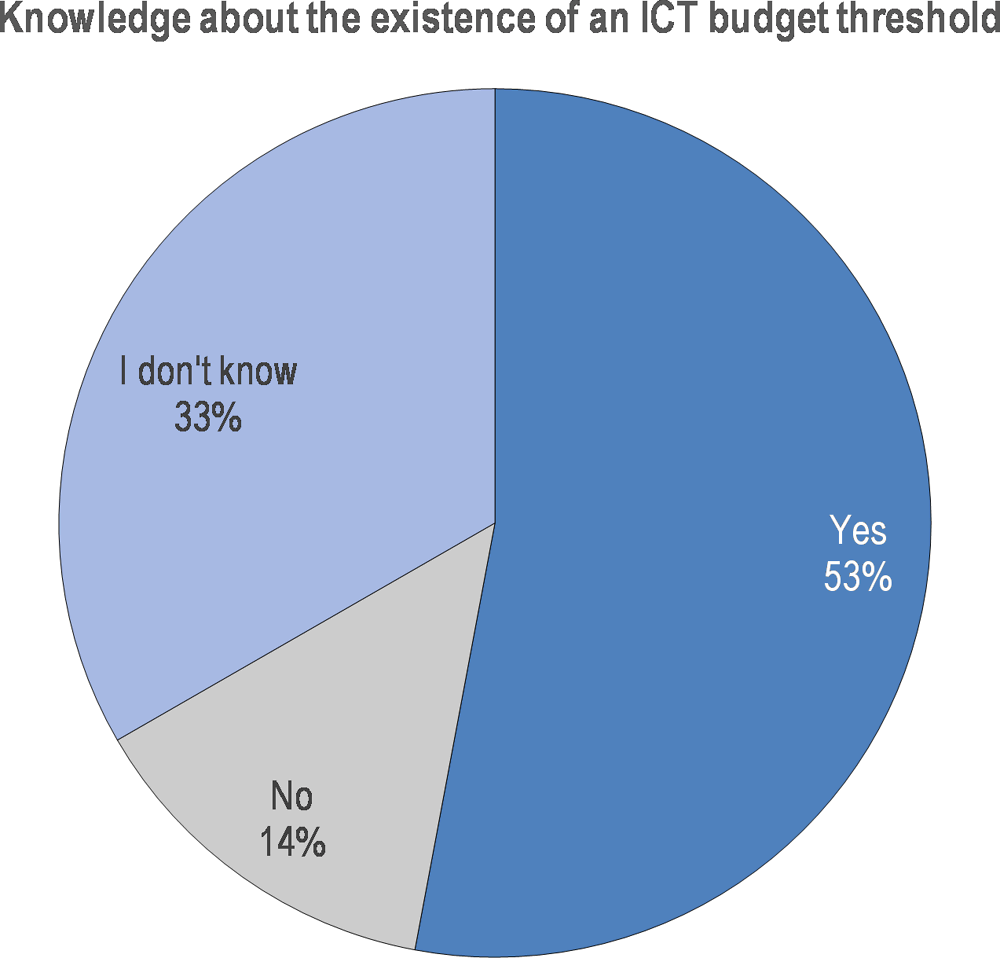

Figure 2.7. ICT budget threshold – Knowledge about its existence in Panamanian public sector organisations

Source: OECD (2019[8]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

According to the Digital Government Survey of Panama, when questioned about the existence of a budget threshold for investments in digital technologies, 53% of the Panamanian public sector responded positively. Since almost half of the respondents were not aware of the existence of a threshold, AIG could consider reinforcing the communication to raise awareness of its role and benefits for the public sector.

Cost-benefit analysis

Given the fast pace of digital disruption, investments in digital technologies are becoming progressively complex. Governments have to deal with increasingly conservative budgets, challenging procurement methods, permanently evolving technological trends and with the increasing expectations of transparency and collaboration from private and civil society stakeholders (OECD, 2016[14]). Different cost structures need to be considered (e.g. specialised human resources, specific hardware, development of tailored software, security tests, usability tests, load tests, legal consulting services) to address dependencies from multiple variables (e.g. economic or social sector to be applied, profile of final users, expected demands, foreseen technological evolution, national or international regulations) (OECD, 2017[15]).

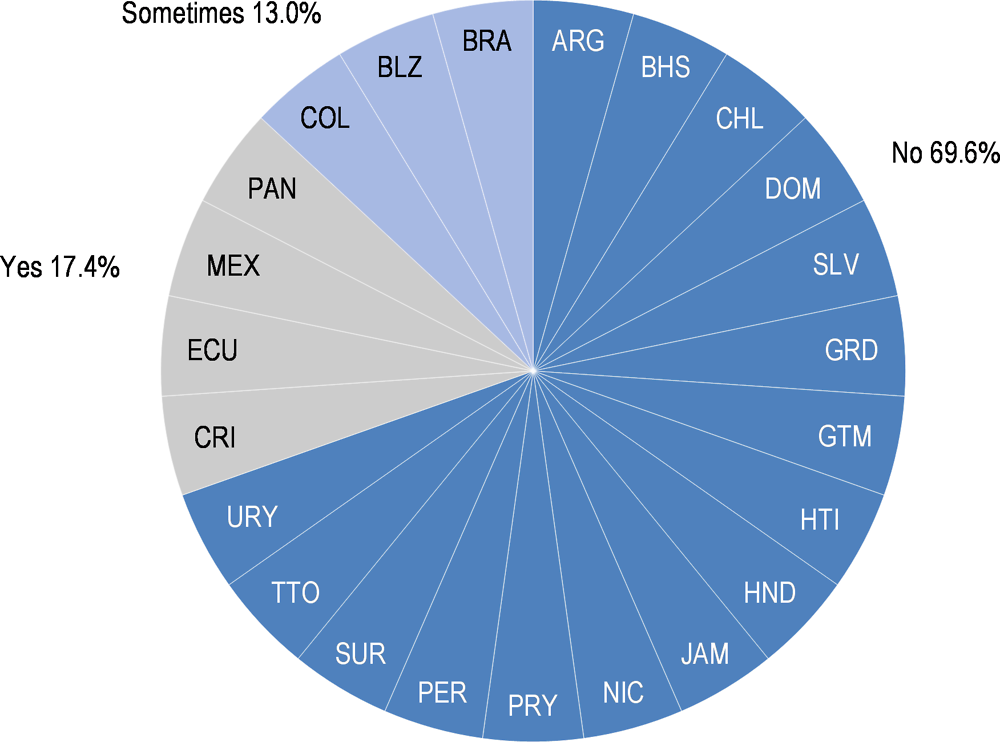

Reflecting the increasing efforts of governments to promote efficiency, coherence and sustainability of investments in digital technologies, 33% of the OECD countries that participated in the Digital Government Performance survey confirmed that financial benefits are always measured and 52% reporting doing it “sometimes” (OECD, 2014[6]). The examples Denmark, Norway, Portugal and the United Kingdom are particularly relevant for securing coherence and sustainability of ICT investments across the public sector (OECD, 2016[14]), (OECD, 2017[15]). The panorama in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region is substantially different, with only 17.4% of the countries confirming the measurement of financial benefits, 13% report doing it “sometimes” and the remaining vast majority of the countries (69.6%) not using this approach (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. ICT financial benefits – Measurement in the central government (LAC)

Source: OECD (2016[16]), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

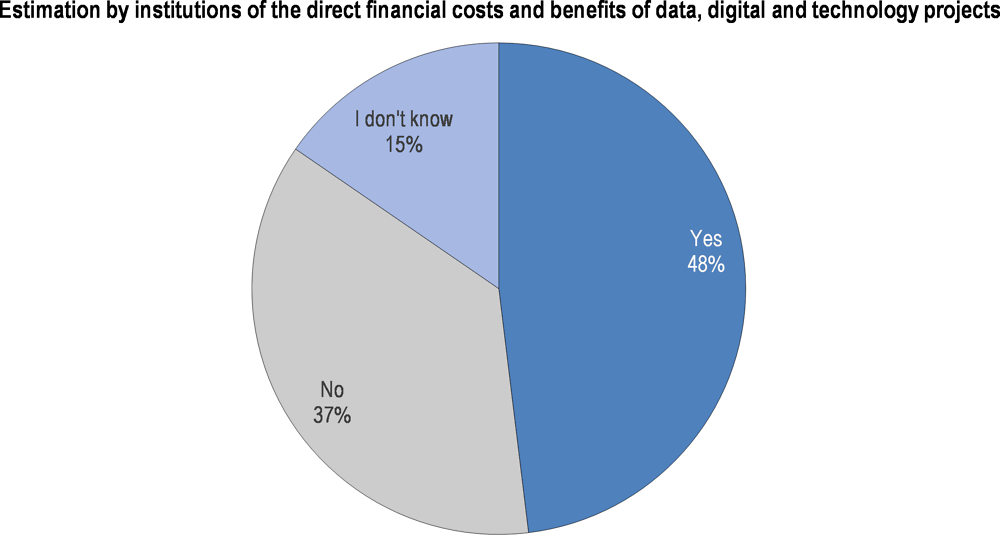

Panama is one of the four countries in the LAC region that has a partial practice of estimating the financial benefits of investments in digital technologies This practice needs to be extended to the rest of the government. When the Panamanian public sector organisations were questioned about the estimation of ICT costs and benefits, 48% confirmed this practice, whilst 37% of respondents to the Digital Government Survey of Panama said they did not (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9. ICT costs and benefits – Estimation in Panamanian public sector organisations

Source: OECD (2019[8]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Although the estimation of financial benefits is not mandatory in Panama, almost half of public sector organisations have this practice. The Government of Panama should consider building on this significant adoption and institutionalise its use across the public sector. Since AIG already provides oversight on investments in digital technologies above a certain threshold, the estimation of financial benefits could be considered mandatory when above the threshold and a recommended practice could be provided for investments below the threshold.

Business cases

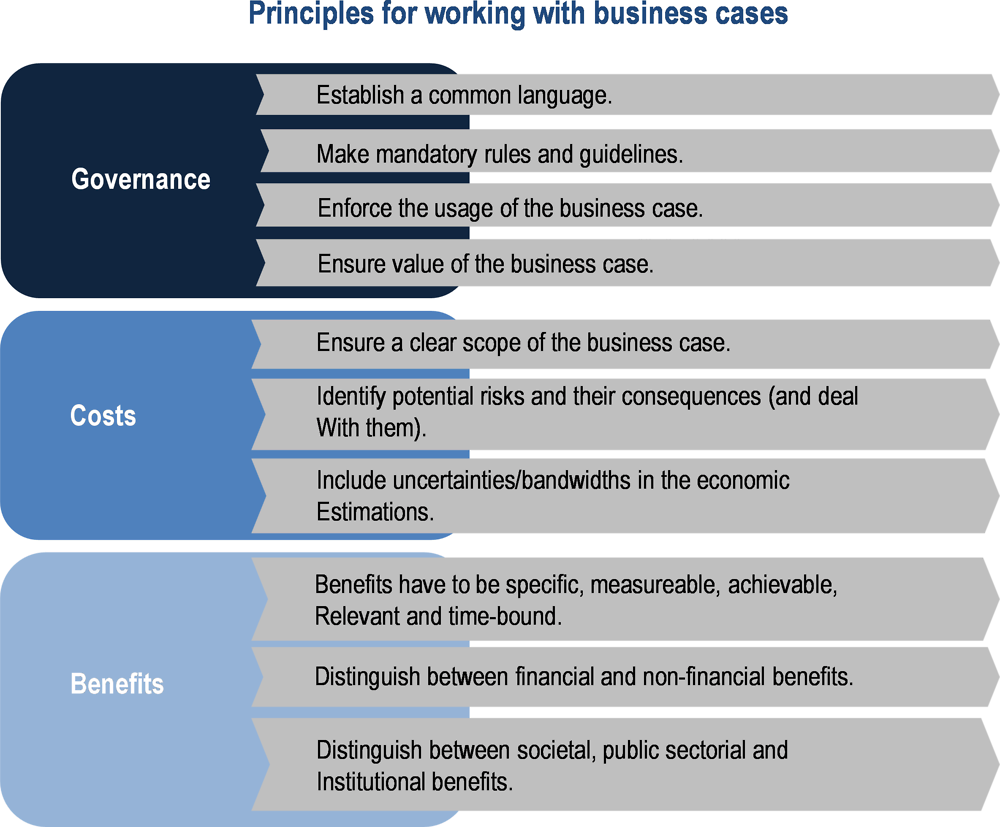

Key Recommendation no. 9 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) underlines the importance of business cases in reinforcing the digital policy of the public sector, contributing to improved planning, development, management and monitoring of the investments in digital technologies. Used as a critical tool to inform the decision-making process on investments in digital technologies and normally associated with a budget threshold, business case methodologies should consider financial but also non-financial benefits, allowing broad planning and understanding of the outreach of policy actions.

By breaking down the economy and management of the project in diverse deliverables, business case analysis contributes to tackling and mitigating project risks. These methodologies also bring transparency and improved accountability since publication of business cases allow civil society to better follow the effective implementation of the projects and the return on the investment (Agency for Digitisation, 2018[17]).

Figure 2.10. A framework for ICT business cases

Source: Based on Agency for Digitisation (2018[17]), Report from the OECD Thematic Group on Business Cases, Unpublished.

Following a request from the OECD Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders), a thematic group bringing together government representatives from several countries has been working to share practices on “what works and what doesn’t work” in business cases for investments in digital technologies. Based on the experience and views of its members, the abovementioned E-Leaders Thematic Group on Business Cases produced a framework of Principles for Working with Business Cases, focused on supporting countries to take the full benefit of these methodologies for sound digital government (Figure 2.10). The framework was being updated and reinforced with country practices during the drafting period of the current report.

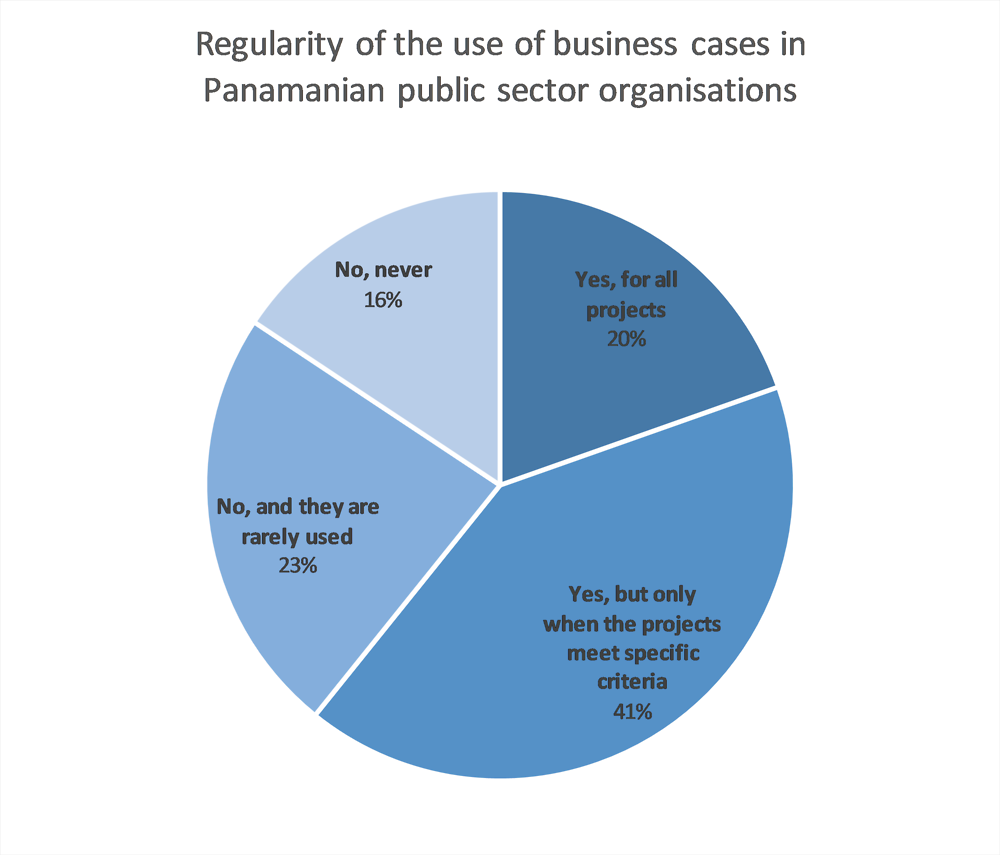

According to the Survey on Digital Government Performance, the majority of OECD member countries reported using business cases. In some cases they apply to all projects and in others only when specific criteria are met (e.g. budget threshold) (OECD, 2014[6]). The results of the survey and the permanent co‑ordination underway between OECD member countries, namely through the aforementioned thematic group, demonstrate that there is still room for improvement in order to mainstream the adoption of this important policy mechanism by public sector organisations.

Figure 2.11. ICT business cases – Use by Panamanian public sector organisations

Source: OECD (2019[8]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

In Panama, there is no specific standardised model of business cases for investment in digital technologies. Nevertheless, when questioned in the Digital Government Survey of Panama about the use of business cases for their investments in digital technologies, 20% of Panamanian public sector organisations confirmed using one for all projects and 41% when the projects met specific criteria (Figure 2.11).

Public sector institutions in Panama clearly recognised the value of these methodologies during the fact-finding interviews held by the OECD peer review team. The practice underway already demonstrates a significant level of adoption, and the Government of Panama could consider establishing the mandatory use of this important policy lever above the existing budget threshold of PAB 50 000 (approximately EUR 44 000) for coherent and sustainable digital government and increase its maturity. The mandatory use of standardised business cases for investments could help promoting improved efficiency, alignment and robustness to the public efforts and commitments already underway. The involvement of the ecosystem of digital government stakeholders in the definition of the business case, in line with the, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), would encourage buy-in and the distribution of realised benefits across the government, economy and society.

Agile project management standards

As outlined previously, encouraging the development of co‑ordinated efforts across the administration is one of the main benefits of having policy levers in place that support sound planning of investments in digital technologies. In line with Key Recommendation no. 10 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), a standardised agile project management mechanism promotes efficiency, stimulates combined efforts across the administration, encourages knowledge sharing and supports evidence-based policy-making when managing public resources. Agile approaches also encourage government to quickly develop solutions, test them and iterate their work based on regular feedback, Agile project management standards, such as those adopted in the United Kingdom, are also able to promote strategic, financial, legal and institutional alignment across the different sectors and levels of government.

When based on agile and shared platforms, advanced data-based monitoring mechanisms can be adopted, contributing to comparative project performance and comparability in the public sector. If widely used across the administration, project management standards can even allow the administration to have dashboards of projects and initiatives underway, to provide a comprehensive picture of the public efforts underway to policy decision-makers.

Fifty-nine percent of the countries that responded to the 2014 OECD Digital Government Performance Survey confirmed having a standardised project management model for the central government (OECD, 2014[6]). The results demonstrate the increasing value that governments attribute to methodologies that can allow co‑ordinated and streamlined policy action across the administration. The relevance of common management methodologies for strategic policy action can be illustrated in completely diverse contexts such as the cases of SISP Project Management Methodology in Brazil or the Project Wizard in Norway (see Box 2.2). The United Kingdom permanently promotes an agility culture across the public sector to build and run government digital services. An Agile Delivery Community shares information for agile working in the government and provided space for discussion among practitioners on the use of agile ways to deliver government projects and services (GDS, 2019[18]).

In Panama, there is no project management standard used across the administration. Nevertheless, in 2017, AIG published General Norms for the Management of ICT in government (Normas Generales para la Gestión de las Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación en el Estado) (AIG, 2017[19]). The document envisages standardised management of ICT across the public sector, incorporating control guidelines that can strengthen the technological systems and infrastructures in public sector organisations. The norms cover a wide range of subjects such as the use of shared services and the management of software licences, security norms and intellectual property rights, disaster recovery plans and even mainstreaming green ICT. The norms are a good example of how AIG uses its oversight and co‑ordination mandate to promote coherent and sustainable development of digital government across the Panamanian public sector.

Having in mind the willingness demonstrated by public sector organisations to improve the alignment and coherence of digital government efforts across the administration, boosting efficiency and sustainability, the introduction of an agile project management standard would constitute a critical asset for building a cohesive digitally- enabled state in Panama. Building on the General Norms mentioned above and being adequately co‑ordinated with the budget threshold, the cost-benefit analysis and the business case methodology, the use of this policy lever can contribute to improved outputs and outcomes for the initiatives underway, reducing risks of non-delivery and encouraging synergies and joint efforts across different public sector organisations.

Moreover, a standardised agile project management model can contribute decisively to improve the mechanisms of central monitoring and forecasting, given the amount of potential information collected in structured ways, as well as reinforce the transparency and accountability of the several initiatives underway, allowing the stakeholders outside the government to better follow project implementation.

Co-funding

Considering that oversight and control mechanisms such as budget thresholds, cost-benefit analysis and business cases enforce policy coherence, financial incentives and mechanisms such as co-funding can be critical levers to mobilise institutional wills, secure alignment and strengthen commitments in a positive way. More than demonstrating centralised control over investments in digital technologies, the existence of co-funding mechanisms managed or strongly influenced by the public sector organisation that leads the digital government policy can stimulate proactiveness towards solutions, entrepreneurship and innovation across the administration.

Box 2.2. Project management standards – The experiences of Brazil and Norway

SISP Project Management Methodology (Brazil)

In Brazil, although its use is not mandatory, public sector organisations are advised to use a project management methodology. The SISP Project Management Methodology (Metodologia de Gerenciamento de Projetos do SISP, MGP-SISP) is a set of good practices and steps to be followed in the project management of ICT projects in public sector organisations. It aims to assist public organisations involved in the System for the Administration of Information Technologies Resources (Sistema de Administração dos Recursos de Tecnologia da Informação, SISP) (see Chapter 2).

Very detailed, the SISP Project Management Methodology guides users in the steps for the correct development of IT projects and initiatives. Nevertheless, as stated in its online presentation, “the adoption of the methodology will depend on some factors, such as: reality, culture and maturity in project management, organisational structure, size of projects, etc.”. In this sense, customising the processes and procedures described in MGP-SISP to each organisation’s situation is recommended (SISP, 2011[20]). To facilitate its use, the Secretariat of ICT has designed diagrams and made available a set of templates such as a demand formalisation document, a project measurement worksheet, a project opening term, a project management plan, a schedule and a risk sheet, among others.

Project Wizard (Norway)

In 2016, the Norwegian government established the mandatory use of a best practice project management model for ICT projects over NOK 10 million, in order to maintain high levels of performance in the development of digital government, provide new opportunities for coherence and promote synergies across the administration.

The Agency for Public Management and eGovernment’s (Difi) Project Wizard is the recommended (although not mandatory) project management model (www.prosjektveiviseren.no). Understood and conceived as a shared service, this online tool directed at project managers aims to reduce complexity and risks in public ICT projects. Project Wizard describes a set of phases that projects must go through, with specific decision points. It covers full-scale project management, including benefits’ realisation.

Although its implementation across the Norwegian public sector is still very recent, the way the platform is structured and the fact that its adoption benefits from substantial institutional support, it appears that Project Wizard has become a strategic tool to improve the development and monitoring of digital government projects across the Norwegian government.

Source: OECD (2018[21]), Digital Government Review of Brazil: Towards the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307636-en; OECD (2017[15]), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en.

This strategic policy lever is also able to mobilise synergies across different public sector organisations for the development of initiatives and projects in key areas naturally aligned with the vision, objectives and goals of the national digital government policy. Additionally, co-funding should be strongly aligned with the digital government key enablers in place, ensuring that initiatives and projects that will benefit from financial support accomplish strategic systems-thinking prerequisites such as the use of the interoperability guidelines and standards or the digital identity framework.

In the OECD context, few examples can be found of leading digital government organisations that are responsible for managing or capable of deeply influencing co-funding for the development of digital government. Nevertheless, examples such as the Portuguese Agency for Administrative Modernisation that manages the provision of specific European structural funds, demonstrate how decisive this policy lever can be to effectively influence in a co‑ordinated way the development of the digital government policy in the country (see Box 2.3). Uruguay presents also a relevant example of centralised and strategic management of ICT funds (OECD, 2016[14]).

In Panama, AIG does not benefit from co-funding capacities that would constitute an extra policy lever for the co‑ordination and providing strategic leadership of the digital government policy across the administration, Building on the widespread and positive recognition of the mandate of the Authority. If properly combined with the adoption of a new business case model and project management methodology, this strong policy lever could also contribute to the recommended shift from an operational to a more strategic policy role of AIG, allowing the Authority to consolidate the necessary leadership of the digital government policy in Panama (see Chapter 1: Enabling legislation and digital rights).

Box 2.3. Governing the investment in digital technologies in the Portuguese public sector

The Portuguese Agency for Administrative Modernisation (Agência para a Modernização Administrativa, AMA), an executive agency located within the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, has substantive powers in terms of the allocation of financial resources and approval of ICT projects.

AMA manages the administrative modernisation funding programme, which is composed of EU structural funds and national resources (SAMA2020). The programme is an attractive source of funding for public sector organisations planning to develop new ICT projects. This mechanism gives AMA important institutional leverage as the approval of funding for digital government projects through this programme is conditioned on compliance with existing guidelines.

Similarly, every ICT project of EUR 10 000 or more must be pre-approved by AMA, which verifies compliance with guidelines, the non-duplication of efforts, and compares the prices and budgets with previous projects in order to ensure the best value for money.

Source: OECD (2016[14]), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en

Towards digital commissioning

Why ICT procurement matters

As governments face increasing expectations from citizens and businesses and need to manage limited budgets to respond to them, core government activities such as public procurement become strategic in improving efficiency and effectiveness. In OECD countries, public procurement spending represents about 12% of gross domestic product (GDP), ranging from 5.1% in Mexico to 20.2% in the Netherlands. The large volume associated with procurement procedures raises risks of inefficiency, mismanagement and lack of integrity, but also enables the use of this important policy mechanism for the achievement of broader economic and societal impacts (OECD, 2017[22]). If used strategically, public procurement can contribute decisively to more productive and inclusive economies, more efficient public sectors, more inclusive and more trusted institutions (Gurría, 2016[23]). The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement (2015[24]) promotes strategic and holistic use of this institutional mechanism across sectors and levels of government through overarching guiding principles addressing the entire procurement lifecycle.

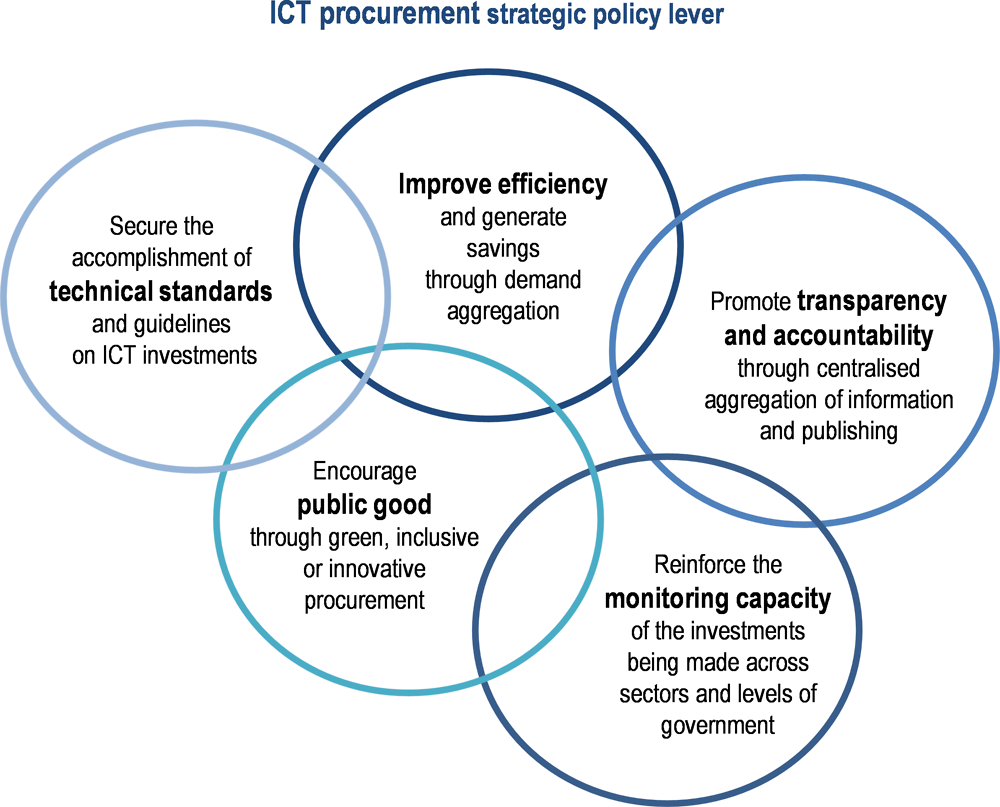

Specifically developed to support governments to drive the digital transformation of the public sector, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) identifies in its Key Recommendation no. 11 the existence of an ICT procurement framework as a fundamental requirement for a sound digital government. Given the progressive penetration of digital technologies in all sectors and levels of government, transforming the way governments operate and relate with citizens and companies, ICT procurement is a strategic policy lever capable of aggregating multiple strategic ends, from efficiency to transparency, from monitoring capacity to enforcement of standards and guidelines (see Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. ICT procurement – Different outcomes

Source: Author.

Given the rapidly evolving technological trends that governments face, the procurement of digital technologies is increasingly required to embrace agile approaches for the acquisition of services and goods. Updated legal and regulatory frameworks should support government responses to challenges such as cloud-based solutions, news requirements in terms of data ownership and sovereignty or the transition from legacy systems. Investments on digital technologies are at the forefront of the increasingly complex challenges facing public procurement but also allow for the experimentation and use of innovative and advanced solutions that can be replicated in the future in other sectors and work streams. Moreover, investment in digital technologies is evolving from an efficiency and transparency-centred perspective to a more transformative-driven approach. Issues of innovative procurement and strategic procurement (e.g. green procurement, inclusive procurement) are increasingly a priority for OECD countries.

Strategies and co‑ordination for ICT procurement

Governments of OECD member and non-member countries attribute a growing relevance to specific strategies and frameworks that can secure a strategic use of ICT procurement in the public sector. As mentioned above, the opportunities and challenges generated by the progressive adoption of new technological trends (e.g. cloud computing and the emergence of platform-as-a-service or software-as-a-service models), require governments to have strategic vision, leadership and co‑ordination capacity to properly to address the changing procurement needs in a context of digital disruptiveness. The existence of specific policies on ICT procurement, materialised in specific strategies, action plans and frameworks, reflects the importance and commitment of governments in this area.

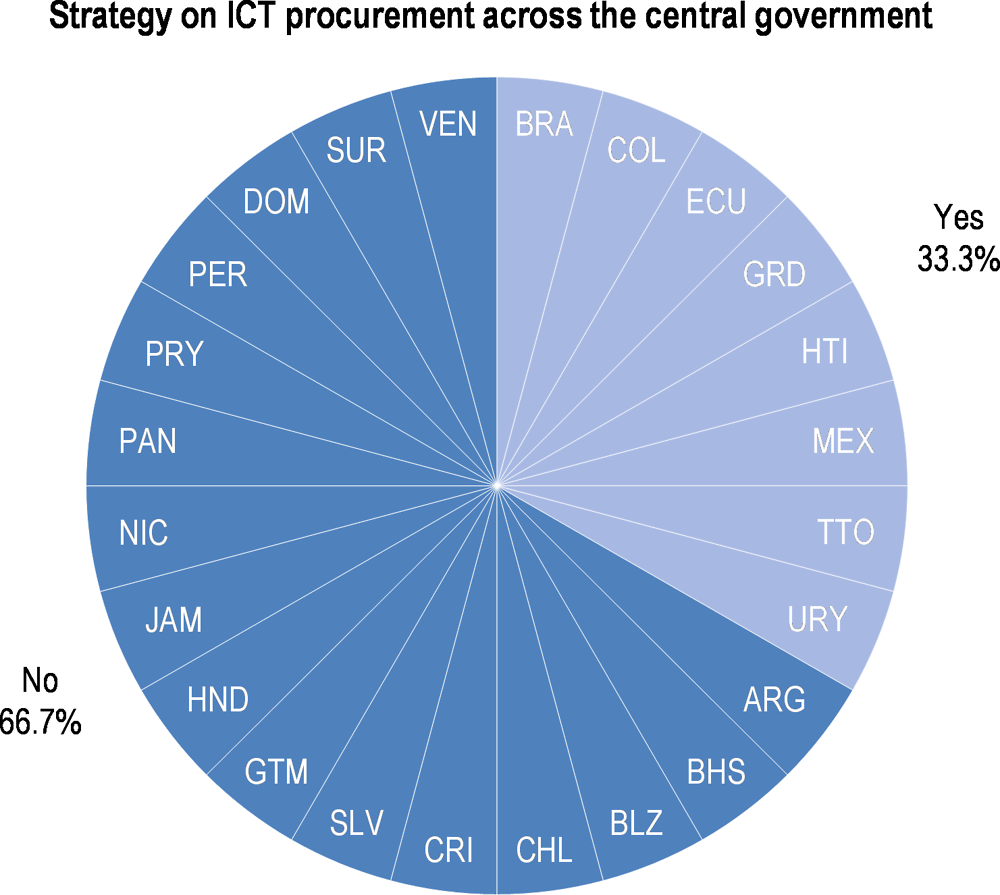

Fifty-two percent of the OECD countries that responded to the OECD Digital Government Performance Survey (2014[6]) have an ICT procurement strategy applicable to the central government. The panorama in the LAC region is less positive with one-third of the countries (33%) reporting having the abovementioned strategy, demonstrating room for improvement in the region regarding a clear establishment of procurement as a strategic policy lever for a digitally-enabled state (Figure 2.13).

Panama does not have a specific strategy dedicated to ICT procurement in place (OECD, 2019[25]). Nevertheless, in 2018, AIG approved Resolution No. 49 of 14 June containing Guidelines for the Acquisition of Information Technology and Telecommunication Goods and Services (Guía para la adquisición de bienes o servicios de tecnologías de la information y telecomunicaciones), containing very detailed instructions to be followed by public sector organisations when managing their ICT procurement processes (AIG, 2018[26]). The guidelines were approved to support the Panamanian public sector in preparing the AIG process of evaluating investments in digital technologies above the threshold of PAB 50 000 (approximately EUR 44 000) (see Chapter 2: Budget thresholds). The detailed guidelines are meant to guide the Panamanian public sector organisations in a broad range of issues such as the use of open standards, evaluating the platforms and services provided by AIG and considering mechanisms to ensure the sustainability of projects, Although a specific ICT procurement strategy is not in place in Panama, the aforementioned guidelines are an important institutional mechanism to frame and regulate ICT procurement in the public sector, allowing AIG to reinforce its oversight mandate and contribute to the coherence and sustainability of investments in digital technologies across the administration.

Figure 2.13. Existence of an ICT procurement strategy in LAC countries

Source: OECD (2016[16]), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en, updated by OECD (2019[8]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

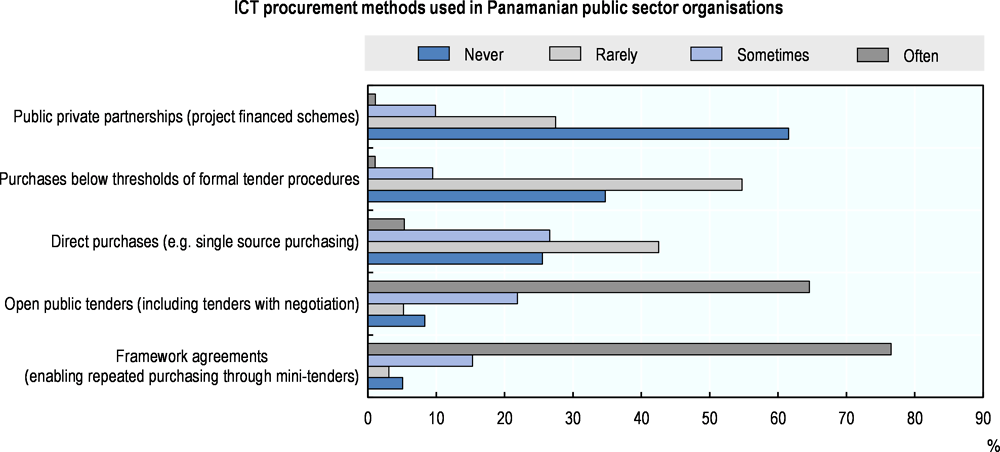

The different methods used to procure ICT goods and services can also provide insightful information about how public sector institutions manage investments in digital technologies. According to the Digital Government Survey of Panama (OECD, 2019[8]), framework agreements that enable repeated purchasing of services and goods through mini-tenders are often used by 76.5% of Panamanian public sector organisations. Open tenders are also frequently used (64.6%) according to the survey. The regular use of these two methods for the procurement of ICT goods and services demonstrates strong compliance with the regulations in place, reflecting a significant maturity in the investments in digital technologies in Panama.

Figure 2.14. ICT procurement – Methods used by Panamanian public sector organisations

Source: OECD (2019[8]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

The necessary update of the procurement law was one of the most clearly highlighted requests underlined by the ecosystem of stakeholders during the 2018 fact-finding interviews . A consensus was found about the inadequacy of the current legal and regulatory framework to support an agile acquisition of ICT goods and services. The legal and regulatory framework in place was also considered insufficient to support the development of public e‑procurement in the country. Given the strategic importance recognised by AIG to increase efforts towards an updated legal and regulatory framework in these areas, improvements are already being undertaken in order to overcome the abovementioned barriers and obstacles for more agile ICT procurement in Panama.

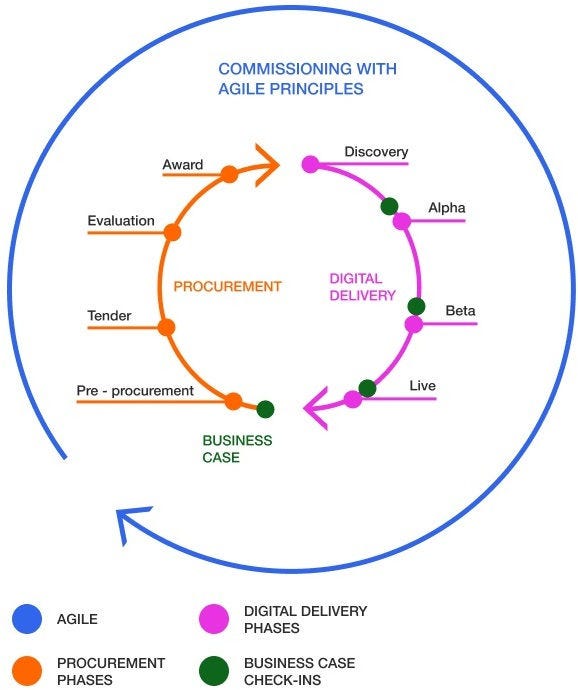

From ICT procurement to digital commissioning

In order to better respond to the speed and complexity of the digital evolution underway, countries are increasingly expected to adopt agile procurement approaches. The digital disruption determines that different cost structures need to be considered for investments in digital technologies (e.g. specific hardware and software, specialised capacity building, new requirements in terms of usability and security), as well as its necessary application to diverse and ever-mutating contexts (e.g. transformation in the different sectors of government, new legal and regulatory frameworks, citizens’ digital rights). In this sense, an evolution from an ICT procurement approach, focused on the technology itself to an ICT commissioning culture, where providers are involved earlier in the commissioning process, through agile mechanisms and proper feedback loops as part of business case check-ins is required to deliver value and realise benefits in the digital age (OECD, 2017[15]; 2018[21]).

Building on an increasing consensus among countries about the aforementioned shift, the OECD Thematic Group on ICT Commissioning, led by the United Kingdom and bringing together representatives from several governments, has been working since 2016 on the concept of agile commissioning and how it can be usefully applied to investments on digital technologies (see Figure 2.15 and Box 2.).

Figure 2.15. Agile commissioning

Source: GDS/OECD (2019[27]), The ICT Commissioning Playbook, https://playbook-ict-procurement.herokuapp.com/.

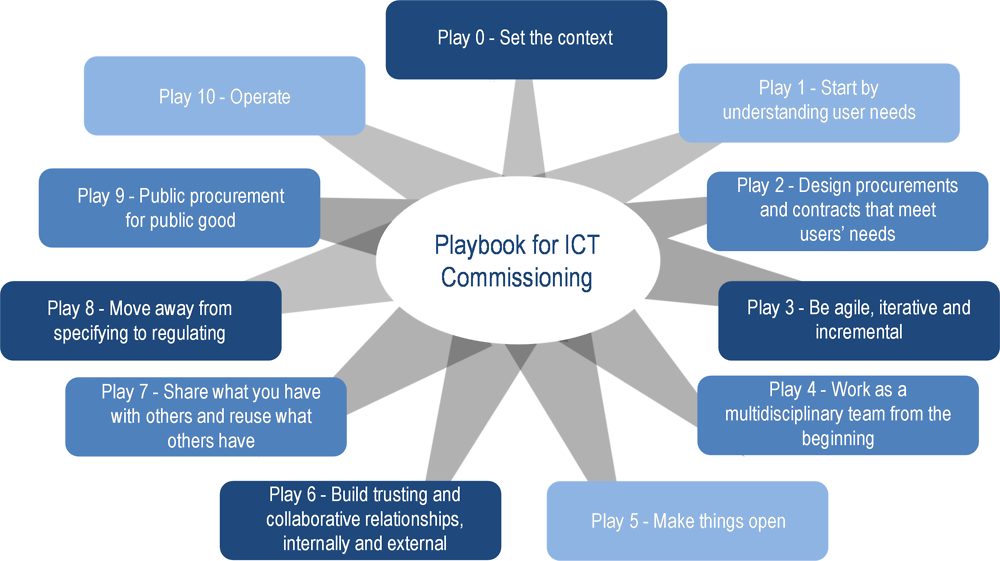

Box 2.3. The ICT Commissioning Playbook

Focused on practical advice for specific situations or “plays”, the thematic group developed a Playbook on ICT Commissioning that could support governments in embracing this advanced paradigm (GDS/OECD, 2019[27]). The group agrees that an agile commissioning approach should encourage governments to:

open up data throughout the procurement and contracting lifecycle;

promote more modular and agile approaches to contracting;

secure procurement transparency to help tackle corruption and improve value for money;

stimulate and access a more diverse digital and technology supply base;

stimulate more flexible, digital, agile and transparent interactions focused on joint delivery; and

share and reuse platforms and components, and better practices for delivering successful programmes (Smith, 2017[28]).

As a result of the inputs received from the governments and other interested stakeholders, the thematic group was able to agree on a set of principles that could support the public sector in the shift towards ICT commissioning. Setting the context, understanding users’ needs, guaranteeing agility, embracing openness and transparency, sharing and reuse, and public procurement for good are some of the principles highlighted that can help governments evolve from an efficiency and transparency-centred perspective to a more transformative-driven approach on investments in digital technologies (see Figure 2.16).

Source: GDS/OECD (2019[27]), The ICT Commissioning Playbook, https://playbook-ict-procurement.herokuapp.com/.

Building on the progressive consensus found among senior officials in charge of investments in digital technologies in the OECD countries’ public sectors, the digital transformation of procurement goes far beyond having advanced e-procurement systems/platforms in place. A real transformation of acquisition processes should be really understood from a digital by design perspective, where digital technologies are embedded from the start in the design, development, delivery and monitoring of procurement frameworks and processes. Efficient, open, trustworthy, interconnected and intelligent e-procurement platforms are only a part of the abovementioned shift towards commissioning approaches that take full advantage of the innovative potential of digital technologies.

Figure 2.16. ICT commissioning – Draft of principles

Source: Based on GDS/OECD (2019[27]), The ICT Commissioning Playbook, https://playbook-ict-procurement.herokuapp.com/.

Additionally, the digital transformation of public sector procurement should be understood as including the potential and expected capacity to use and reuse data as a core asset to improve procurement procedures; through better monitoring and forecasting; and in making procurement procedures simpler, less bureaucratic, more transparent and accountable. Commissioning is, in this sense, one of the positive outputs of a sound data-driven public sector (see Chapter 3).

During the fact-finding mission, the Panamanian institutions consensually agreed on the potential for improving the management of investments in digital technologies, and that AIG more clearly stated as a short-term policy priority, that the Government of Panama should use this opportunity to leapfrog towards a commissioning approach. Building on the experiences from some OECD member countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Panama has the opportunity to improve its policy of investments on digital technologies, making it more aligned with user needs, involving the providers throughout the procurement lifecycle and, in this sense, decisively enabling agile commissioning to seize the digital transformation underway. The foreseen short-term update of the ICT procurement legal and regulatory framework should fully integrate this ambitious mind-set.

References

[17] Agency for Digitisation (2018), Report from the OECD Thematic Group on Business Cases, Unpublished.

[13] AIG (2018), Memoria 2018, Unpublished.

[26] AIG (2018), Resolutíon No. 49 de 14 de Junio de 2018 - Aprueba la Guía para la adquisición de bienes o servicios de tecnologías de la information y telecomunicaciones, http://innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Resolucion49GuiaparaObtenciondeConceptoFavorableSESyDEROGAResolucion14de%202015.pdf.

[19] AIG (2017), Normas Generales para la Gestión de las Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación en el Estado, http://innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Normas%20Generales%20para%20la%20Gesti%C3%B3n%20de%20las%20TIC%20en%20el%20Estado%20Version%201.pdf.

[7] AIG (2016), Agenda Digital 2014-2019 - Panamá 4.0, http://innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Agenda_Digital_Estrategica_2014-2019.pdf.

[18] GDS (2019), Agile delivery.

[11] GDS (2018), GDS Academy, https://gdsacademy.campaign.gov.uk/ (accessed on 20 July 2018).

[27] GDS/OECD (2019), The ICT Commissioning Playbook, https://playbook-ict-procurement.herokuapp.com/.

[10] GOV.UK (2017), Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/digital-data-and-technology-profession-capability-framework (accessed on 20 July 2018).

[23] Gurría, A. (2016), “Generating an innovation dividend from public spending”, Welcome Remarks by Angel Gurría, Secretary-General, OECD, OECD Forum on Procurement for Innovation, Paris, 5 October 2016, https://www.oecd.org/innovation/generating-an-innovation-dividend-from-public-spending.htm.

[25] OECD (2019), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Central Version, OECD, Paris.

[8] OECD (2019), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[2] OECD (2019), OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability, https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-on-public-service-leadership-and-capability.htm.

[21] OECD (2018), Digital Government Review of Brazil: Towards the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307636-en.

[9] OECD (2018), Digital Government Survey of Brazil, Central Version, OECD, Paris.

[12] OECD (2018), Review of the Innovation Skills and Leadership in Brazil’s Senior Civil Service - Preliminary Findings, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Brazil-Leadership-Findings-web-2-002.pdf.

[3] OECD (2017), Core Skills for Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/media/oecdorg/satellitesites/opsi/contents/files/OECD_OPSI-core_skills_for_public_sector_innovation-201704.pdf.

[15] OECD (2017), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en.

[22] OECD (2017), Government at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

[5] OECD (2017), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

[14] OECD (2016), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

[16] OECD (2016), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

[24] OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/.

[1] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD/LEGAL/0406, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406 (accessed on 12 July 2018).

[6] OECD (2014), Survey on Digital Government Performance, OECD, Paris, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796 (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[4] OPSI (2017), How Can Government Officials Become Innovators?, https://oecd-opsi.org/how-can-government-officials-become-innovators/.

[20] SISP (2011), Metodologia de Gerenciamento de Projectos do SISP, http://www.sisp.gov.br/mgpsisp/wiki/download/file/MGP-SISP_Versao_1.0.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2018).

[28] Smith, W. (2017), Open Procurement for a Digital Government, https://gds.blog.gov.uk/2017/08/16/open-procurement-for-a-digital-government/.