This chapter analyses the experience of the data-driven public sector in Panama. It introduces a model for data governance featuring the facets of leadership and vision, capacities for coherent implementation, regulation, the data value cycle, and data architecture and infrastructure. The chapter then considers the application of data to unlock public value in terms of anticipatory governance, the design and delivery of policy and services, and performance monitoring and evaluation. Finally, the chapter explores the role of data in building trust with a discussion of transparency, data protection, citizen consent and ethics.

Digital Government Review of Panama

3. Data driven public sector

Abstract

Introduction

As governments undergo digital transformation, there is a growing recognition of the importance of data to underpin, shape and inform the activity of the public sector. Governments produce, collect and use data on an ongoing basis. However, this can be done in ways that emphasise existing siloes and without respecting standards or considering how it might duplicate data stored elsewhere. Sometimes this is down to a deliberate decision; other times it is simply that organisations are unaware of the impact of their choices. In other ways, the legal or governance structures in a country may be an obstacle to the easy use or reuse of the data that governments already hold. This is indicative of an inadequate understanding or recognition of data as a strategic asset for public sector organisations.

As governments have matured in their recognition of data as a strategic asset, much effort has focused on the importance of Open Government Data (OGD), leading to the publication of public sector datasets to stimulate private sector innovation, provide opportunities for the economy at large and increase government accountability (OECD, 2018[1]). In other cases, the use and reuse of data internally within government to make policy, design services or monitor performance is patchier. However, neither scenario is yet delivering fully on the potential for governments to transform the way in which they serve the public. Indeed, whilst progress has been made on approaches to both data within government and OGD, it is important that approaches to the role of data recognise that both are fundamental to transforming government rather than issues that can be handled separately.

Box 3.1. OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies: Principle 3

The [OECD] Council […] on the proposal of the Public Governance Committee […] recommends that governments develop and implement digital government strategies which:

Create a data-driven culture in the public sector, by:

developing frameworks to enable, guide, and foster access to, use and re-use of, the increasing amount of evidence, statistics and data concerning operations, processes and results to (a) increase openness and transparency, and (b) incentivise public engagement in policymaking, public value creation, service design and delivery;

balancing the need to provide timely official data with the need to deliver trustworthy data, managing risks of data misuse related to the increased availability of data in open formats (i.e. allowing use and re-use, and the possibility for non-governmental actors to re-use and supplement data with a view to maximising public economic and social value).

Source: Text from OECD (2014[2]), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406.

Principle 3 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]) (Box 3.1) discusses the need for frameworks that support the re-use of data and set the basic foundations to unlock the value of raw and isolated data to provide a foundational building block for the delivery of a twenty-first century, digital government. It is in this context that the OECD has proposed the concept of a data-driven public sector (DDPS) (van Ooijen, Ubaldi and Welby, 2019[3]). Countries that have implemented a strategic approach to the use of data throughout the public sector are better able to anticipate societal trends and needs and consequently develop more effective long-term plans. Additionally, data plays an important role in the ongoing design and delivery of public services and efforts to analyse and evaluate all types of government activity in order that the information helps to make improvements and offers transparency about success and failure, in ways that strengthen accountability and stimulate public engagement and trust.

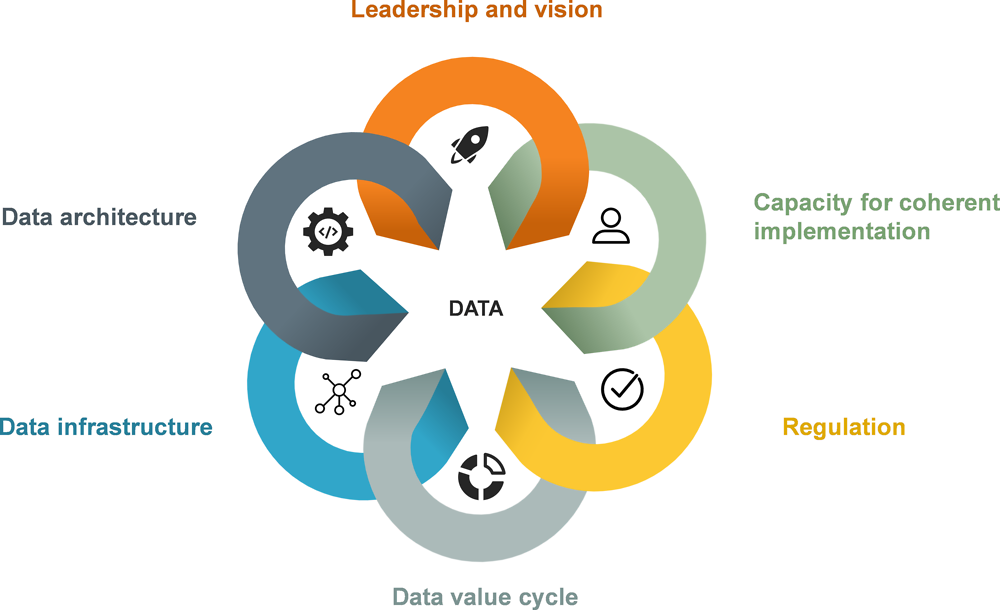

Figure 3.1. Opportunities of a DDPS

Source: van Ooijen, C., B. Ubaldi and B. Welby (2019[3]), “A data-driven public sector: Enabling the strategic use of data for productive, inclusive and trustworthy governance”, https://doi.org/10.1787/09ab162c-en.

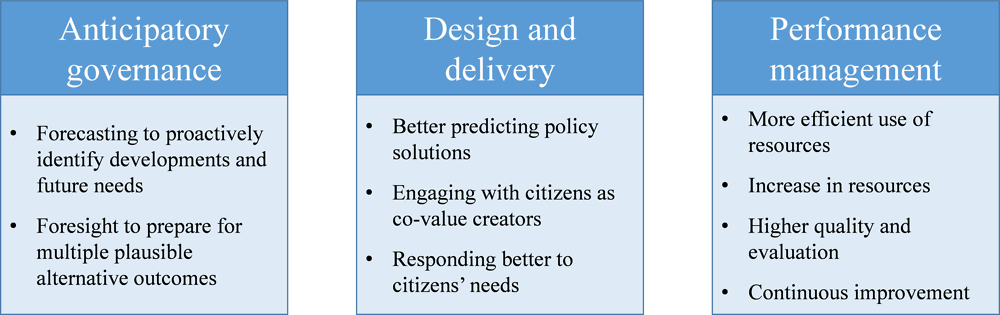

In order to maximise the value of data when applied in these ways, it is essential for countries to recognise the foundational role of data. The OECD has refined this concept of DDPS to propose a comprehensive model for data governance that reflects the importance of several areas in successfully delivering on the promise of data (Figure 3.2) (OECD, 2019[4]; OECD, 2019[5]).

Figure 3.2. Data governance in the public sector

The data governance model identified in Figure 3.2 considers six different elements as critical to the success of the DDPS in a country. They are:

1. leadership and vision

2. capacity for coherent implementation

3. regulation

4. data architecture

5. data infrastructure

6. data value cycle.

This reflects the importance of establishing how authority, control and shared decision-making take place in the context of managing data assets between those with a shared interest in those data assets, whether within one or across multiple organisations (Ladley, 2002[6]). Whilst certain aspects of that data governance are done by individuals carrying out a particular functional role, this is not a transactional set of tasks but a strategic competency that covers the activities, capacities, roles and instruments to successfully enshrine a data-driven culture within the activity of a government.

Although some of these areas may be covered by existing practices within a country, any lack of strategic co‑ordination or clarity of leadership may result in sub-optimal outcomes and disconnected or siloed approaches. In some countries this may result in a focus on a particular aspect of the data governance agenda, perhaps by implementing technical or operational elements (such as data standards) or prioritising legislation (perhaps on interoperability) but not considering the broader, government-wide concerns of leadership, data strategy and the necessary co‑ordinating guidelines and bodies that might be required.

This chapter will consider how the experience of Panama fits into this data governance model before exploring how data has been applied according to the opportunities of a DDPS shown in Figure 3.1. It will conclude with a consideration of how Panama is approaching the role of data in establishing trust.

Data governance in Panama

Leadership and vision

The Panamanian Government strategy (Gobierno de Panama, 2014[7]) recognises that development of information and communications technology (ICT) would only be an effective tool for modernising the state if accompanied by measures allowing for internal collaboration and interoperability. This strategic commitment built on the provisions made in Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012 (Asamblea Nacional, 2012[8]) for all government databases to be interoperable.

Furthermore, the country’s commitment to leadership in terms of the transparency and accountability of government through the use of OGD was marked by Law No. 33 of 25 April 2013 that created the National Authority of Transparency and Access to Information (Autoridad Nacional de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información, ANTAI) (Asamblea Nacional, 2013[9]). Alongside ANTAI, there have been important efforts to encourage the modernisation of the National Institute of Statistics and Census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo, INEC) and the role they both play in supporting the open government and open government data agenda in Panama.

This recognition of the importance of OGD and Panama’s commitment to it is supported by Executive Decree No. 511 of 24 November 2017 (Ministerio de la Presidencia, 2017[10]) and exemplified by the National Action Plan for OGD (Plan de Acción Nacional de Datos Abiertos de Gobierno) (Autoridad Nacional de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información, 2017[11]) which identified several important strengths of Panama’s approach to OGD as well as highlighting areas in which greater efforts were needed. A strong OGD policy framework is supported not only by the work of ANTAI but also by a director-level appointment within the National Authority for Government Innovation (Autoridad Nacional de Innovación Gubernamental, AIG) that focuses on the open data strategy. A commitment to OGD was also shown by six of the organisations that participated in the institutional survey having Chief Data Officers with a remit focused on open data.

This evidence of high-level political support for a strategic approach to OGD should be commended but, as Panama, AIG and ANTAI look towards their future ambitions for the country, there is an important need for this understanding of OGD to be complemented by a broader vision for the possibilities of the DDPS. When asked to identify the country’s data strategy, AIG and several other institutions highlighted the National Action Plan for OGD (Autoridad Nacional de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información, 2017[11]). Although this is an excellent resource, identifying several important crosscutting elements for the future of data governance in Panama, it is not a document designed to implement a DDPS approach.

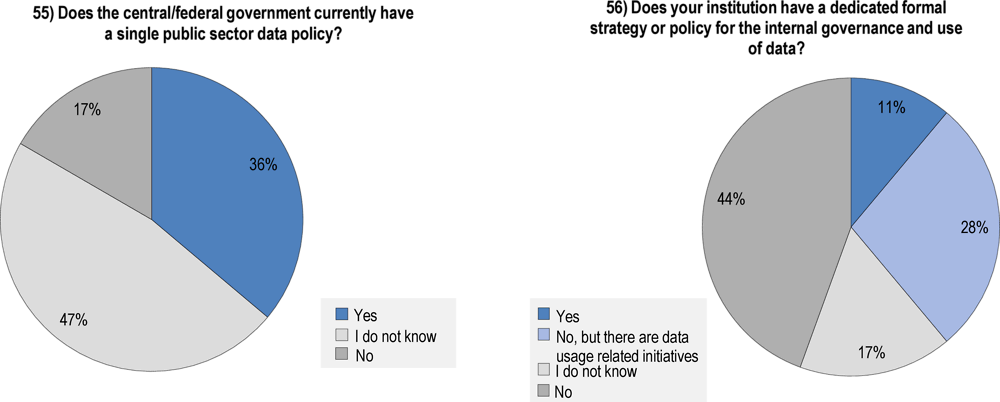

Figure 3.3 shows that only 36% of institutions identified there being a national data strategy. Irrespective of the content of the National Action Plan and its focus on OGD, this figure suggests an awareness gap between the centre and the institutions themselves. This may in part be due to the closed way in which the National Action Plan for OGD was prepared, as the survey indicated that this was carried out entirely at the centre by ANTAI and AIG with limited participation. As Panama considers the development of any renewed data strategy that places the concept of DDPS at its heart, there would be benefits to approaching it in line with the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]) in terms of wider participation and engagement of those across government. The survey showed that those outside the centre would likely add value to that process; Figure 3.3 shows that several institutions have experience in preparing their own internal data strategies. Of the 51 institutions that supplied answers, 6 (or 11%) have an institutional data strategy but a further 13 (26%) have put in place initiatives to support internal data governance and the use of data.

Figure 3.3. National and institutional data strategies in Panama

Note: Based on the response of 51 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 55: “Does the central/federal government currently have a single public sector data policy?” and Question 56: “Does your institution have a dedicated formal strategy or policy for the internal governance and use of data?”.

Several OECD countries are now exploring how to create a focal point for leading and stewarding discussions about the role of data (including but not limited to OGD) in their digital transformation. In Korea, there is a Chief Data Officer for the country, as well as specific requirements for a similar role in every public institution. This approach is legislated for in United States where the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 stipulates, “the head of each agency shall designate a non-political appointee employee in the agency as the Chief Data Officer of the agency” (115th Congress of the United States, 2019[13]). A similar ambition is being explored in Peru following the recommendations of the recent Digital Government Review (OECD, 2019[14]). Creating a specific role is a symbolic statement about the importance of data. It is also practically valuable in identifying the role and establishing the suitable mandate to lead and steward the development of national and institutional data strategies, and deliver the necessary change to embed a data-driven culture.

In Panama, ten institutions have a Chief Data Officer with six of those being focused on open data only. A further 21 institutions are planning to introduce a Chief Data Officer in the near future. Nevertheless, this excludes the government itself, which does not currently have a figurehead for leading the strategic conversation, and decisions, about the role of data. AIG has responsibility for co‑ordinating this activity, but there is a need to provide clearer leadership and ensure that the country has a clear strategy for achieving its ambitions to be a DDPS. The role of Chief Data Officer can provide a clarity of purpose in thinking through the requirements and needs associated with the data strategy for Panama. Such a strategy needs to consider the role of data for internal use in helping the government to function more effectively, the application of data for external impact and the interactions that stimulates with the public, as well as the role and opportunities for OGD to stimulate the economy and offer greater transparency and accountability.

Although questions of data infrastructure (see Chapter 3: Data architecture and infrastructure) are important, the survey responses identifying the biggest challenges to the application of data in the Panamanian public sector are instructive about what any national or institutional Chief Data Officer should prioritise in their data strategy. Many challenges were recognised as being medium barriers but the following issues were identified as being a strong barrier more often than weak:

1. Guidance on the governance and use of data in policymaking and service design.

2. Data gathering methods, sources, quality and relevance for policymaking and service design.

3. Capability training on data management and use for policymaking and service delivery.

4. Lack of clear value proposition and cost benefit for the use of data in policymaking.

5. Need for checks and balances and accountability for data-driven decision-making in policymaking, service design and service delivery.

This contrasts with the areas of relative strength where the issue was identified as being a weak barrier more often than strong:

1. Data storage capacities are not an important issue in policymaking, service design or organisational governance and management.

2. Information technology (IT) infrastructure is not seen as a barrier to policymaking or service design.

3. Digital security risk management is not seen as an issue for organisational governance and management.

Collectively, these observations underline that Panama has been able to demonstrate leadership and resolve issues from a technology point of view but that there are gaps in the guidance, training, rationale and evaluation of data-driven activity. These are areas for which leadership and vision are more important than the implementation of technology.

Capacities for coherent implementation

Leadership and vision are of critical importance in creating the strategic conditions for successful implementation of a DDPS but countries need to also address their capacities for coherent implementation within and between government institutions.

Panama has seen effective co‑ordination and activity between ANTAI and AIG in its approaches to OGD but this has not had such a significant impact in the discussion about data more broadly and its role in the transformation of institutions throughout the public sector. Panama has introduced the appropriate legal framework to make it possible for the practical activities of data sharing and re-use to take place across the public sector with Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012 (Asamblea Nacional, 2012[8]) requiring the interoperability of all government databases and establishing the once-only principle for data collection and re-use. Moreover, Resolution No. 12 of 16 November 2015 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2015[15]) established the National Interoperability and Security Committee to co‑ordinate efforts for data interoperability and involve executive representative (representing the highest authority with decision-making power) and technical representative (which should be the information technology director) from a number of institutions. Furthermore, Resolution No. 15 of 3 May 2016 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2016[16]) set out the interoperability framework for Panama and the steps that were expected for how institutions would achieve its implementation with resolutions so far having been made for the security, transportation, agriculture and logistics sectors (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2016[16]; Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2018[17]).

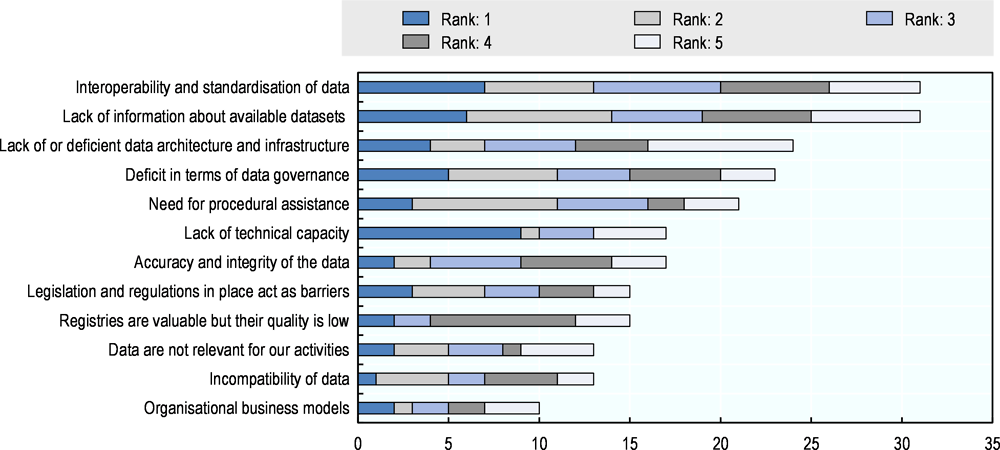

However, Figure 3.4 shows that there is something of a gap between the theory of the interoperability framework managed by the National Interoperability and Security Committee and the experience of institutions across the Panamanian public sector. The most frequently identified barriers to the coherent implementation of a data-driven culture include a lack of information about available data, a lack of interoperability for that data or the standards which shape its architecture and the processes by which that data can be accessed and applied. More than one organisation identified that data are dispersed across multiple institutions that do not want to share that data with other organisations, resulting in the duplicated collection of the same information and less effective government as a result. Others cited that the lack of canonical data supplied through registers results in challenges of accessing complete or accurate information.

Figure 3.4. The biggest barriers to the use of data within institutions

Note: Based on the response of 46 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 69: “Please indicate the five biggest challenges/barriers regarding the use of data by your institution”.

This suggests that AIG may need to revisit its role as central co‑ordinator and explore ways of enforcing particular behaviours or becoming more involved in on the ground delivery to close this gap between theory and practice. Whilst a steering committee like the National Interoperability and Security Committee has provided an important forum for setting the agenda for this aspect of data governance, a shift in approach may yield dividends. Under the oversight of a Chief Data Officer for the country, the development of country and institutional DDPS strategies should empower a network of Chief Data Officers and data professional communities of practice to identify the priorities for resolving some of the most pressing issues with data sharing and interoperability. This may require additional financial, practical and technical support to ensure that the good work in creating the conditions for success can address these outstanding areas to allow DDPS to flourish.

Whilst regulation (see Chapter 3: Regulation) should be considered in terms of hard levers like legislation and softer measures like guidelines, an important area for shaping the capacity for coherent implementation of DDPS is the availability of capable staff.

Law No. 33 of 25 April 2013 (Asamblea Nacional, 2013[9]), which created ANTAI, also made provision for an Information Officer and associated team to exist within each public institution and for them to be given the responsibility for proactive transparency, open data and information requests. However, this role and this team are not always in place and, as discussed in Chapter 3: Leadership and vision, the focus of this responsibility is more informed by an OGD agenda than by the implementation of a DDPS. Several institutions do have a team of people that focus on statistical information or data analytics, with the size of those resources ranging from 1 or 2 to more than 20. However, these are discrete teams created to process data that may otherwise have been handled on paper, rather than resources empowered to support their colleagues in considering the role of digital and data in the ongoing delivery of government itself.

There is huge potential in maximising the role of the Information Officer and any associated team. Nevertheless, in order for that team to act as the champion of a data-driven culture within their organisation, they need to be supported by leadership roles at both the national and organisational level that are currently absent. In order to support efforts around both OGD and DDPS, the Government of Panama should consider it an immediate priority to develop a strategy for appointing people into those roles and co‑ordinating that activity across different sectors and levels of the public sector.

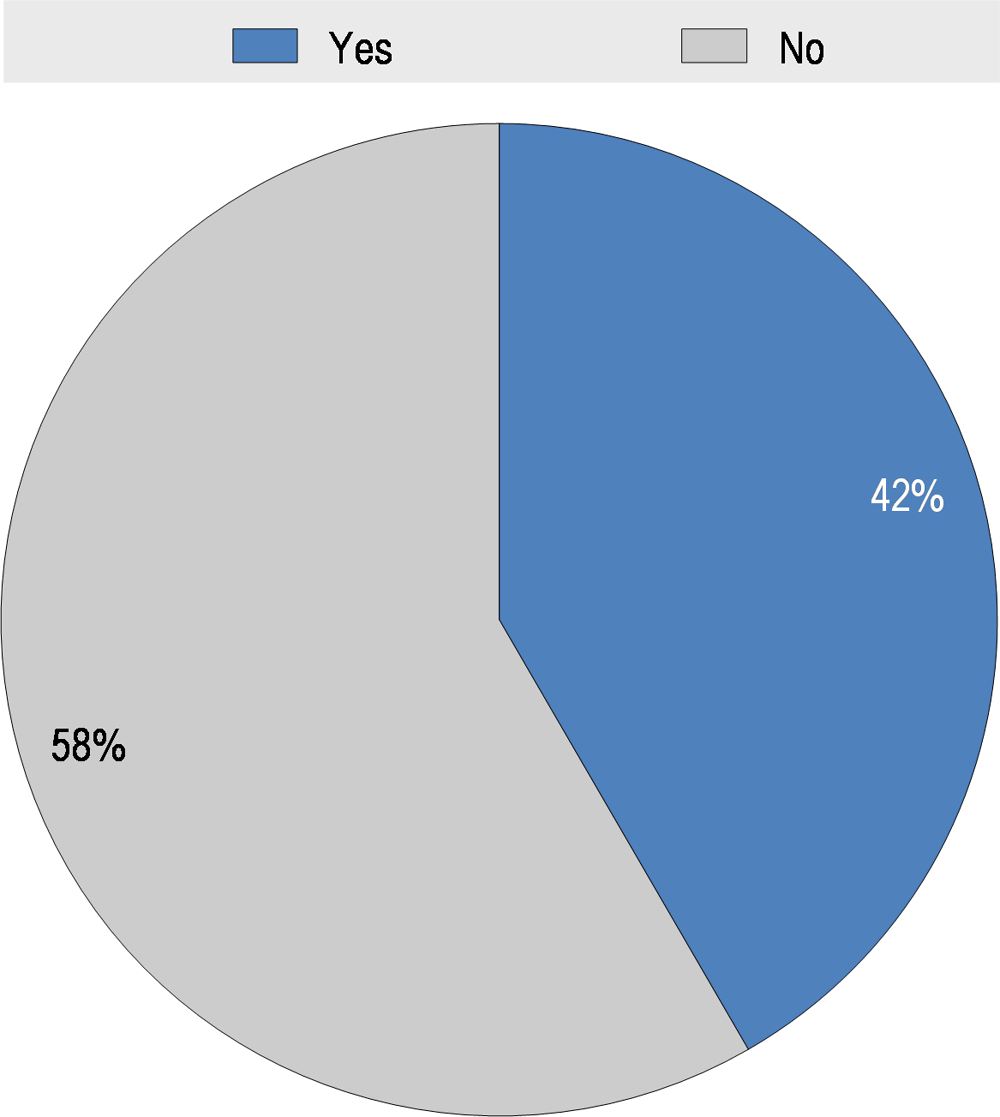

Figure 3.5. Does your institution have a strategy/initiative to develop or enhance in-house data-related literacy and skills among public officials?

Note: Based on the response of 48 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 24: “Does your institution have a strategy/initiative to develop or enhance in-house data-related literacy and skills among public officials?”.

As discussed in Chapter 2, skills are an important area for countries with ambitions of capturing the possibilities offered through implementing digital government strategies. There is an important need to focus on the skills and capabilities of the Panamanian public sector in general and it is critical that attention is given to the strategy for developing or enhancing in-house data related literacy and skills. As seen in Figure 3.5, 58% of the institutions that responded to the survey do not have such a plan in place. Such a strategy should pay attention to specific professional skills such as data scientists and data analysts but an arguably more important factor in this area is considering how teams across the public sector can acquire a sufficient grounding in data literacy that allows anyone to consider the opportunities of DDPS in their particular role.

This should increasingly be a priority for all sectors of the public service as they approach the policy needs of areas such as education, business, health and welfare. In the case of education in particular, Panama has an opportunity to work with external partners to equip their schools with the necessary digital and telecom infrastructure to train students (and teachers) to take full advantage of the digital transformation. An important part of any national curriculum should be the role of data literacy in the context of digital training, which is not currently seen in Panama’s masterplan for education.

Regulation

Panama has several hard regulatory instruments in place that relate to transparency of the public sector, OGD, interoperability and the protection of personal data. Amongst these, the following are particularly important for efforts to implement DDPS:

1. Law No. 6 of 22 January 2002, which handles transparency of the public sector (Panama’s Freedom of Information legislation).

2. Law No. 33 of 25 April 2013, which created ANTAI and makes provision for an Information Officer and associated team to exist within each public institution with responsibility for proactive transparency, open data and information requests (Asamblea Nacional, 2013[9]).

3. Executive Decree No. 511 of 24 November 2017 (Ministerio de la Presidencia, 2017[10]), which established the government’s OGD policy.

4. Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012 (Asamblea Nacional, 2012[8]), which requires all government databases to be interoperable and established the once-only principle for data collection and re‑use.

5. Resolution No. 12 of November 16 2015 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2015[15]), which created the National Interoperability and Security Committee.

6. Resolution No. 15 of 3 May 2016 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2016[16]) set out the interoperability framework for Panama and the steps that were expected for how institutions would achieve its implementation.

7. Executive Decree No. 51 of 4 February 2013 (Ministerio de la Presidencia, 2013[18]) created the Panamanian Spatial Data Infrastructure.

8. Resolution No. 4 of 9 October 2014 (Consejo Nacional de Tierras/Autoridad Nacional de Administracion de Tierras, 2014[19]) approved the Operating Regulations of the Panamanian Spatial Data Infrastructure.

9. Law No. 81 of 26 March 2019 (Asamblea Nacional, 2019[20]), which regulates the protection of personal data (see Chapter 3: Data protection).

This legal framework has been effective in placing OGD on the agenda for many institutions, with 30 out of 49 agreeing that “the potential and value of open data for the achievement of policy goals is acknowledged by the leadership of my institution”. However, despite the focus on interoperability, it is less clear that the legal framework has transformed the ease with which data sharing can take place. Figure 3.4 highlights the extent to which access to data and interoperability is seen as a challenge.

This gap between the intent of these legal frameworks and the practice of institutions across Panama may owe something to the limitations around skills and capability discussed in Chapter 2 and earlier in this chapter. Panama appears to lack softer instruments such as guidance on the governance and use of data, as well as support for implementing the interoperability framework, publishing government data or structuring metadata. Box 3.2 discusses how organisations in Denmark, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States that have similar responsibilities to AIG in terms of building capability and delivering digital transformation have produced guidance and resources to build capability but also to effectively establish standards and norms for delivery without implementing harder measures to enforce it.

Box 3.2. Guidance published and curated by central digital authorities to support teams elsewhere in government

The GOV.UK Service Manual (United Kingdom)

A resource produced through collaboration between different communities of data, digital and technology professions, this covers the delivery of digital services to reflect the country’s service standard. Although it is the responsibility of the Cabinet Office’s Government Digital Service, it is used by teams at every level and in every sector of government.

Wikiguías (Mexico)

The Wikiguías are a series of recommendations for implementing standardised digital services on Mexico’s single government website gob.mx. The content consists of the framework for contributing to the single government website as well as the guidelines for implementing according to the provisions of Mexico’s Digital Services Standard.

Source: https://www.gob.mx/wikiguias

18F Digital Service Delivery Guides (United States)

A set of technical guides produced by 18F that focus on disseminating best practice in the area of user-centred development.

Source: https://18f.gsa.gov/guides/

Fællesoffentlig Digital Arkitektur (Denmark)

A website documenting and exhibiting architecture, architectural rules and corresponding standards and guidelines adopted and implemented in connection with the common public architecture work.

Source: https://arkitektur.digst.dk

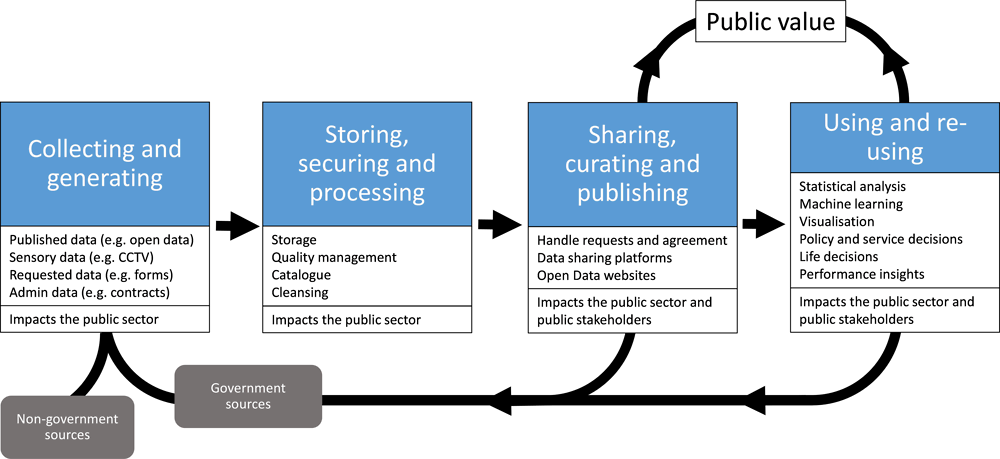

Data value cycle

The Government Data Value Cycle (Figure 3.6) presents four phases of data in government from its initial collection and generation, through its storing, securing and processing, on to the sharing, curating and publishing of that data and then finally into its use and re-use. The first two stages of the process are entirely about how the public sector manages and looks after its responsibility to the data it collects and holds whilst the final two stages offer opportunities to add public value either through the improvement of policy and services or the opportunities generated by OGD.

Figure 3.6. Government Data Value Cycle

Source: van Ooijen, C., B. Ubaldi and B. Welby (2019[3]), “A data-driven public sector: Enabling the strategic use of data for productive, inclusive and trustworthy governance”, https://doi.org/10.1787/09ab162c-en.

The process by which data (raw, isolated and unstructured datasets) is transformed into information (where relationships between data are identified) and knowledge (understanding those relationships) provides the basis for decision-making at the strategic, tactical and operational levels of government (taking action). This building of public sector intelligence and creation of public value does not happen in a linear fashion but through a cycle, which involves feedback loops throughout the process. Data can inform and affect the nature of decision-making processes which in turn can lead to the production and collection of different or more data (OECD, 2015[21]).

In Panama, certain aspects of the cycle are currently well administered with strong indications from the survey of public sector institutions that the infrastructure associated with storing and managing data is a strength (see Chapter 4: Government as a Platform capabilities). Furthermore, there is a healthy culture of organisations publishing their open data either through the national open government data website (Datos Abiertos de Panamá, https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pa) established by Executive Decree No. 511 of November 24 2017, with 720 datasets published from 32 institutions at the time of this report or through their own institutional website. Of the 49 organisations that responded to that question, 25 are publishing open datasets, with 8 of them doing so through the national website. There are some initial encouraging signs of an open data ecosystem beginning to emerge with initial conversations between academics, civic-minded software engineers and the government starting to take place late in 2018.

However, in general, there was limited evidence that these phases are seen as reinforcing and supporting one another in contributing to a coherent approach to making policy, delivering services or evaluating performance. In designing future data strategies, whether at a national or institutional level, it is important for Panama to keep the Government Data Value Cycle (Figure 3.6) in mind and recognise how a focus on each stage of the cycle allows data to flow more easily into the next. This results in the ability to enable a digital-by-design approach to public services that can proactively address the needs of citizens and businesses in the delivery of end-to-end services.

It could prove valuable for Panama to map the needs for data across the public sector and identify where existing data flows easily and where there are barriers to sharing and interoperability. Whilst this can help to establish the priorities for developing Application Processing Interfaces (APIs) or publishing particular datasets, there is an adjacent need to provide support for public servants in understanding how to make data open, useable and reusable. Such efforts should consider training and guidance for the application and reuse of data in their day-to-day work as well as applications in other parts of government and externally. This activity will rely on the development of a cross-government network of practitioners with access to the necessary resources (whether human or financial) to transform Panama’s approach to data.

Data architecture and infrastructure

Whilst it is vital for countries to implement strong leadership, set clear vision and create the right practical and regulatory conditions for success, it is equally important to address the architecture and infrastructure that shape the data and inform access to it in order to transform the Government Data Value Cycle (Figure 3.6). This includes how the architecture of data reflects standards, interoperability and semantics related to the generation, collection, storage and processing of data (the first half of the Government Data Value Cycle). It also requires an infrastructure to support the publication, sharing and re-use of data (the second half of the Government Data Value Cycle), including catalogues, sources of reliable data and the means by which that information can be accessed whether through APIs or the necessary data sharing arrangements. This architecture and infrastructure are critical to empowering government teams to apply the value of data in meeting the needs of citizens and designing solutions that transform policy outcomes.

For the citizen, one of the areas where approaches to data generate the most friction is when they are required to provide information, which government may already hold. The once-only principle of citizens not having to provide information which government should already be able to access is enshrined in Panamanian law through Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012 (Asamblea Nacional, 2012[8]). This law sets the expectation for the interoperability of databases and the sharing of data between different organisations whilst Resolution No. 15 of 3 May 2016 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2016[16]) provides a further set of principles that should be followed.

Box 3.3. Platforms in Panama that support data sharing

AIG has developed a number of platforms that underpin the collection and exchange of information within Panama. The National Health Electronic Management (Gestión Electrónica de Salud Nacional), GESNA) and the National Agro-commercial Integrated System (Sistema Integrado Agrocomercial Nacional, SIAN) are being used to source statistical data for completing census returns that help the country to plan for future needs. The data that is collected is then made available to other parts of the government.

One of the biggest opportunities for Panama is the National Intelligent System to Monitor Alerts (Sistema Inteligente Nacional de Monitoreo de Alertas, SINMA). A component of the Smart Nation strategy, it has been developed by AIG for use by many institutions as a cross-government platform to support the monitoring of public services and provide a route for citizens to report, or be alerted to, emergencies. The platform improves interoperability and simplifies the interaction and exchange of information between relevant actors in transit, natural disasters, social programmes and security, as well as others. Efforts so far show the potential for this approach to form the basis for a strategic approach to other aspects of transforming Panamanian public services.

The full value of this approach has not yet been realised but there are important indications of a platform for success. The work on the National Health Electronic Management (Gestión Electrónica de Salud Nacional, GESNA), the National Agro-commercial Integrated System (Sistema Integrado Agrocomercial Nacional, SIAN) and the National Intelligent System to Monitor Alerts (Sistema Inteligente Nacional de Monitoreo de Alertas, SINMA) discussed in Box 3.3 show a clear commitment not only to the theory but to the practice of making interoperability possible across the Panamanian public sector. Greater support, whether through legislation, increased mandate or political will towards the ongoing efforts of AIG needs to exist for the agenda of ensuring interoperability between platforms and government organisations and the true realisation of the once-only principle in the way in which teams across Panama are able to access and support data from elsewhere.

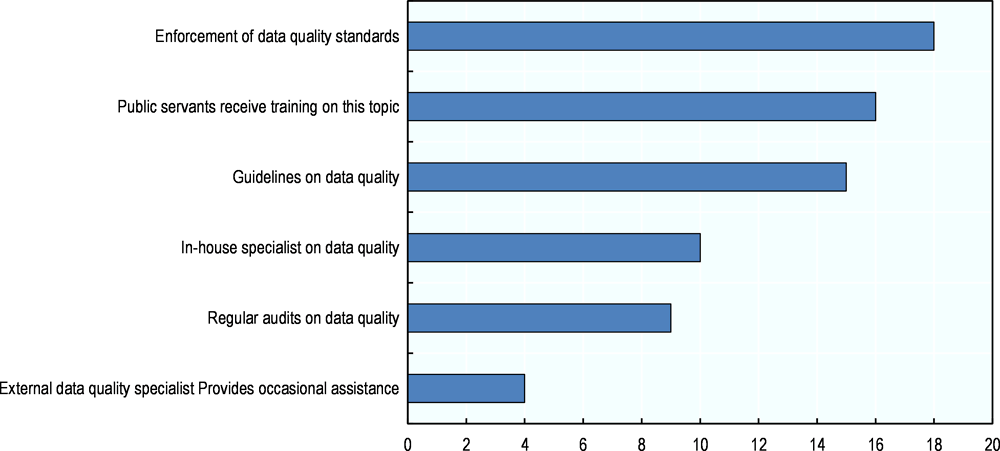

Data quality

An important aspect of data architecture is ensuring the quality of data during the generation and collection stage of the Data Value Cycle. Of the 51 institutions surveyed for this review, 12 had no steps in place to ensure the quality of their data, 22 had a single measure in place, 6 had two and 8 had three measures. Figure 3.7 shows the relative popularity of the six different measures that were identified. The most popular approaches of enforcing data quality standards, providing public servants with training and producing guidelines are all positive ways of building a culture of data awareness rather than focusing efforts on external resources, auditing of data or concentrating the knowledge of data within a particular set of in‑house specialists.

Figure 3.7. Measures for ensuring the quality of data

Note: Based on the response of 51 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 64: “How do you ensure the quality of your institutional data?”

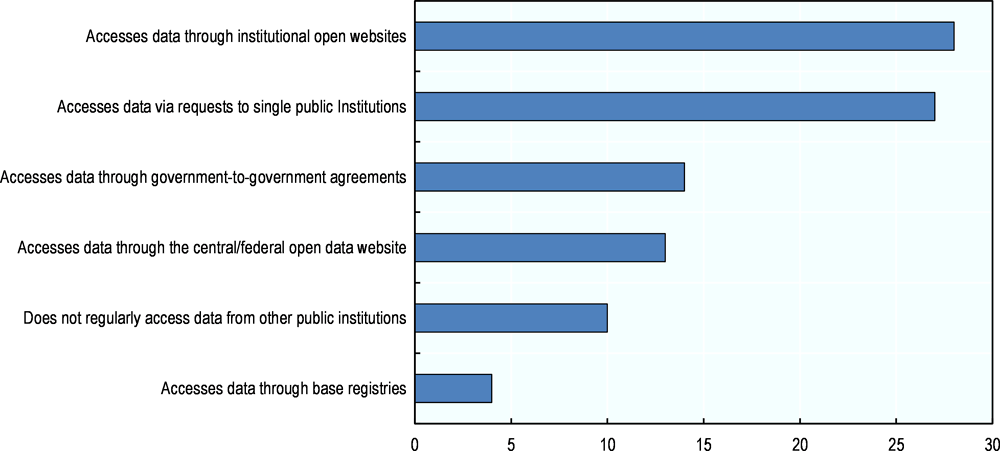

Data access and sharing

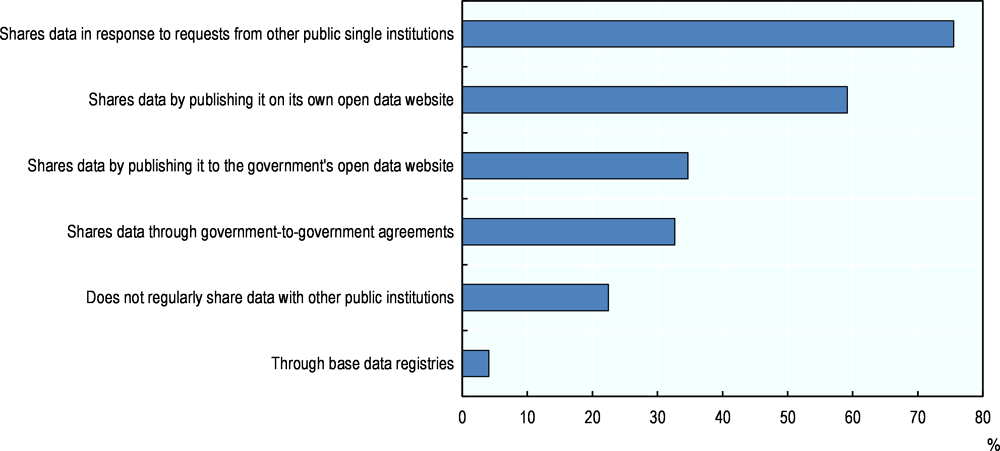

Several of the most frequently identified issues with regard to the use of data in Figure 3.4 relate to data infrastructure. In particular, the 31 organisations were clear that there was a lack of information about what data was available and there was a consistent message about the need to address the practical challenges to streamline and support the sharing and interoperability of data. Figure 3.8 shows that the most frequently used route for accessing government data is via institutional open data websites (not via Datos Abiertos de Panamá, www.datosabiertos.gob.pa). Whilst this is an endorsement of Panama’s OGD focused approach at an institutional level, it highlights an inevitable barrier to the application and re-use of personal data within the government as well as the ongoing fragmentation caused by multiple open data websites. The reasons which some of those organisations gave were instructive with several organisations citing long processes in requests for information and being given permission as well as challenges with the data architecture as reasons why they did not access data from other organisations more frequently.

Figure 3.8. How data is accessed from other public institutions

Note: Based on the response of 49 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 67: “Please indicate through which method(s) your institution regularly accesses data from other public institutions”.

Box 3.4. Basic Data in Denmark

The 2010 OECD e-government study of Denmark highlighted the importance of providing high-quality basic data registries to support the activity of government teams but also to stimulate the effectiveness of OGD efforts. Although the country had some existing registries, coupled with the necessary legal frameworks, their adoption was limited as they did not reflect the needs of their users.

To move away from pure adherence to the law and towards the provision of an enabler that responds to needs, the government undertook a three-year programme for implementing basic data registries in Denmark. This effort revisited the whole approach to data governance within the public sector, including changing the legal framework as well as building partnerships outside of government to capture views and identify valuable sources of data.

As a result, public authorities in Denmark now register various core information about individuals, businesses, real properties, buildings, addresses and more. This information, called basic data, is re‑used throughout the public sector and is an important basis for public authorities to perform their tasks properly and efficiently, not least because an ever-greater number of tasks have to be performed digitally and across units, administrations and sectors.

However, basic data also has great value for the private sector, partly because businesses use this data in their internal processes and, partly, because the information contained in public sector data can be exploited for entirely new products and solutions, in particular digital ones. In short, good basic data, which is freely available to the private sector, is a potential driver for innovation, growth and job creation.

Source: Good Basic Data for everyone – a driver for growth and efficiency (The Danish Government and Local Government Denmark, 2012[22])

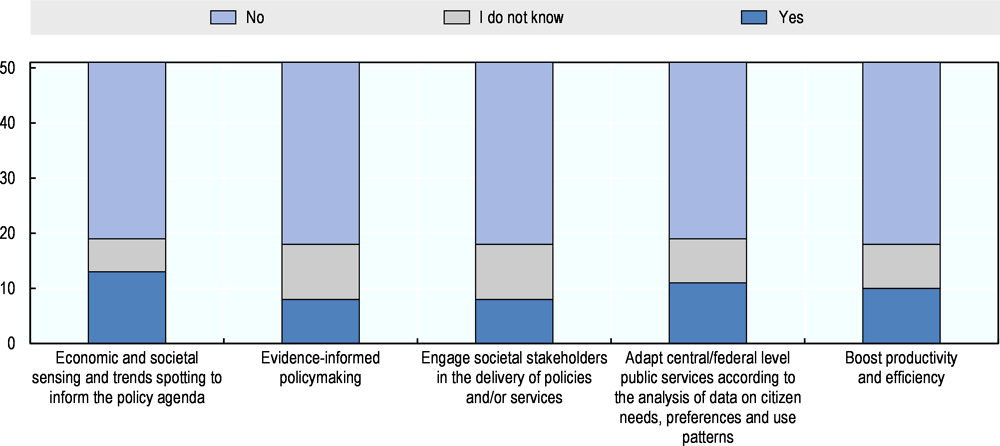

These concerns also highlight a lack of access to base registries or a comprehensive solution for data sharing within and between institutions. In Panama, significant progress has been made in creating the regulatory and oversight mechanisms for interoperability at a theoretical level but progress in this area is less clear at the institutional level where the majority of surveyed institutions highlighted challenges with access to that data. There is a clear demand for data within Panama, with Figure 3.9 showing 78% of organisations actively sharing data with other organisations. Currently, this is happening in a variety of ways – through the government’s open data website, their own open data website, government-to-government agreements and in response to ad hoc requests. There is only minimal sharing taking place through an approach of base registries. The most widely consulted data is that held by the Electoral Tribunal about citizens and for which interoperable data sharing arrangements can be made within the public sector, and with the private sector (for a fee).

One of the identified enablers for digital government is the presence of base registries providing canonical sources of information relating to populations, addresses, qualifications and others (an example of this is discussed in Box 3.4). The audit and maintenance of these sources by an identified and responsible party can provide a valuable reference for other services and reduce the potential for duplicated data to be collected elsewhere. In Panama, Executive Decree No. 719 of 15 November 2013 (Ministerio de la Presidencia, 2013[23]) established the means by which such important data sets and web services would be made available for use by government teams through their publication in a catalogue and availability within the interoperability platform (see Chapter 4: Data and interoperability). However, if such registries exist in Panama then, as shown in Figure 3.9, there is little to no awareness of them. Moreover, in those cases where sources of canonical data were identified, the provided information did not reflect the sort of canonical record of data expected to be found in a base register.

Nevertheless, whilst these registers are not yet in place, or mature in their adoption, the presence of enabling legislation provides an important foundation on which Panama might build. The examples of interoperable platforms discussed in Box 3.3 show that this agenda is building momentum but that this would benefit from the strategic approach to data flows across the Panamanian public sector discussed throughout this chapter.

Figure 3.9. How data is shared with other public institutions

Note: Based on the response of 49 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 65: “Please indicate through which method(s) your institution regularly shares data with other public institutions”.

Data catalogues

One way for countries to communicate the availability of data is through a “data catalogue”. The ambition for such a catalogue should not be to index every piece of data published by a government but to prioritise that data which is identified in the mapping of data flows across the public sector as contributing to the delivery of other services or which would obviate the need to collect duplicated data. In Panama, Resolution No. 15 of 3 May 2016 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2016[16]) refers to making web services available free of charge through a catalogue of services.

However, this was not referenced by any of the surveyed institutions and only 4 of the 51 surveyed institutions (Judicial Branch [Órgano Judicial], Mass Transportation of Panama [Transporte Masivo de Panamá], Superintendency of Insurance and Reinsurance of Panama [Superintendencia de Seguros y Reaseguros de Panamá] and the Attorney General of Accounts [Fiscalía General de Cuentas]) identified as having a single exhaustive inventory of data within their institutions with a further 19 having a non‑exhaustive institutional data inventory. These represent important resources within their organisations but these initiatives will be limited in their impact if they are not designed or co‑ordinated in order to facilitate access from outside the organisation and simplicity of re-use between them. Failure to do this will leave public servants needing to look in several places and unable to rely on the available data to be timely or licensed in a way that will allow for simple re-use.

Nevertheless, it is insufficient to create a website for indexing datasets if the level of engagement from government does not stimulate interest in the datasets it contains, promote an understanding of its benefits or encourage external parties to apply the data. In order to establish a culture that naturally considers how data could be applied, the Panamanian government needs to think about how it brings civil society actors and private sector entrepreneurs together with public servants to explore how Panamanian government data can improve lives, whether through government policy, voluntary activities or commercial solutions to everyday problems. The experience of Spain underlines the value of such an approach. The infomediary sector, those companies which analyse and treat public and/or private sector information to create value-added products to support efficient decision-making, created 5 000 jobs and enjoyed turnover of between EUR 1 500 million and EUR 1 800 million in 2015 (ONTSI, 2016[24]).

Applying data to unlock public value

The data governance approach is fundamental to the success of a country wishing to adopt a DDPS approach. Ensuring that there is leadership, capacity to deliver and the necessary legal frameworks as well as an approach that enhances the Data Value Cycle should be the priority for Panama. Getting this right will allow the country to explore ways in which the opportunities for a DDPS can be exploited. Nevertheless, there are important insights from the survey conducted with the institutions about how Panama may wish to enhance the implementation of a data-driven approach to policymaking, service design and delivery, and the monitoring and evaluation of activity.

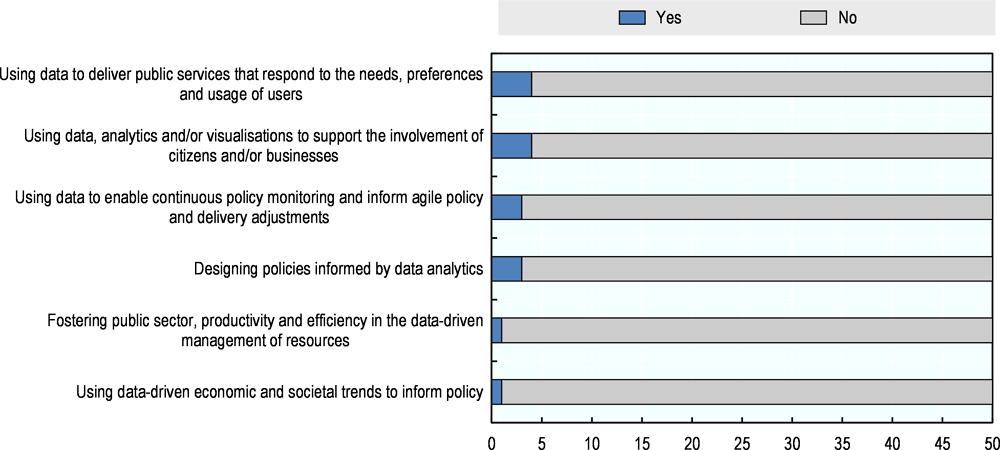

Data relating to the performance of the economy, tourism and construction are critical to how Panama plans its policy agenda. Furthermore, Panama is a committed observer of international indicators and uses these benchmarks to set government priorities. This has resulted in a focus on the competitiveness of Panama and the need to simplify bureaucracy, particularly for businesses. However, as shown by Figure 3.10, only a very limited number of Panama’s public sector institutions have considered the role data could play in the policy and delivery lifecycle as objectives. This suggests that these opportunities are not high on the list of organisational priorities and may be one of the factors in the ongoing challenges for sharing between organisations and cross-sectoral thinking around the standardisation of systems or schemas.

Figure 3.10. Objectives contained within institutional data strategies

Note: Based on the response of 50 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 56: “Does your institution have a dedicated formal strategy or policy for the internal governance and use of data (i.e. providing directions to leverage data for improved policymaking, service design and delivery and/or organisational management, performance and productivity)? Part d) If yes, which of the following strategic objectives are specified in the policy?”

Data-driven anticipatory governance

A data-driven approach can strengthen the effort of countries in exploring anticipatory governance approaches. Anticipatory governance refers to systematic efforts by governments to consider the future in order to inform policy decisions today. It allows governments to respond proactively rather than reactively, based on knowledge and evidence rather than experience and protocol. Using data can enable more proactive decision-making and policy planning, better detection of societal needs as they emerge and facilitate better predictions for future needs. Data-enabled prediction and modelling techniques support governments in anticipating societal, economic or natural developments that are likely to occur in the future. They may also capture early warnings and better assess the need to intervene, design the appropriate policy measures and anticipate their expected impacts more precisely (van Ooijen, Ubaldi and Welby, 2019[3]).

Only the Ministry of Social Development (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, MIDES), one of the minority of organisations with a dedicated statistical unit, has recognised the possibilities for a data-driven approach to economic and societal trends in shaping policy as an objective of the data strategy. Three organisations, the Social Security System (Caja del Seguro Social, CSS), ANTAI and MIDES, have a stated objective in their strategies for an anticipatory approach to evidence-informed policy design.

However, despite this lack of strategic direction, the survey identified several experiences of data influencing the anticipatory governance of Panama, suggesting that there is an active data-driven policy community for AIG to work with, and champion, in establishing a DDPS culture:

1. The Ministry of Economy and Finance (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas, MEF) compile monthly reports tracking social indicators to inform the policy agenda.

2. The Institute for the Development and Use of Human Resources (Instituto para la Formación y Aprovechamiento de Recursos Humanos, IFARHU) has been analysing the experience of 600 000 students eligible for Universal Scholarship to understand their experience in relation to other data and social indicators.

3. The National Energy Secretariat (Secretaría Nacional de Energía) is forecasting behaviours around fuel and electricity consumption to understand how climate affects demand.

4. The National Institute of Women (Instituto Nacional de La Mujer, INAMU) has developed a system of indicators that are regularly collected in order to provide an analytical basis for the creation of public policy.

5. The Ministry of Health (Ministerio de Salud) and CSS are using the GESNA platform for planning the provision of health care and associated services for 255 356 registered patients (over 40 years old) and 340 719 medical interventions (a single patient can have more than one medical intervention)

6. The Ministry of Agriculture (Ministerio de Agricultura, MIDA) and the Institute of Agricultural Marketing (Instituto de Mercadeo Agropecuario, IMA) collect detailed data on 14 752 farmers and 7 409 producers in the SIAN platform, assisting them to work with other sectoral agencies and programmes in planning and offering targeted assistance.

Box 3.5. How analysis of data and having an interoperability platform helped a Portuguese service reach an extra 600 000 people

In Portugal, the insights from data have transformed the way they provide support to some of the most vulnerable households in the country. The government created a Social Energy Tariff (SET) to subsidise energy costs. The service required eligible users to sign up and register but the initial data showed that those who should have benefitted from the tariff were not registering for it.

When research was carried out to understand why that was the case, they learnt that it was because citizens did not know that they had to ask for the special tariff. As a result, the decision was made to automate the process. However, in order to do this, data needed to be shared between the Direção Geral de Energia e Geologia, energy companies, the tax system and the social security system.

This required them to use Portugal’s Interoperability Platform for the Public Administration (iAP). The Interoperability platform provides access to a diverse set of services to meet needs both within and outside government. It works alongside identity, payment and notification platforms to provide a set of capabilities for government teams to deploy. The iAP is managed by a dedicated technical team.

As a direct result of being able to use the iAP for simply automating the SET, the number of households receiving the tariff increased from 154 648 to 726 795, providing financial support to 7% of the Portuguese population with the cost of their energy without requiring them to validate their eligibility.

Source: Information provided by Portugal to the OECD.

Data-driven design and delivery of policy and services

One of the most compelling opportunities for the DDPS is the way in which the application of data can reshape the opportunities for design and delivery in terms of better predicting policy solutions, engaging with citizens as co-value creators and better responding to the needs of citizens.

Four organisations have identified the opportunities for using data to engage citizens and other stakeholders with policy, the Authority of Micro-, Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises (Autoridad de la Micro, Pequeña y Mediana Empresa, AMPYME), ANTAI, IFARHU and CSS. Figure 3.11 shows that eight organisations are actively exploring initiatives that can do this, including the Electoral Court (Tribunal Electoral de Panamá), particularly active during elections to offer special visualisation tools that help the public to comment and participate in the process, and MIDES and MEF in their presentation of the annual Multidimensional Poverty Index.

Figure 3.11. Has your institution implemented policy initiatives to analyse data in these ways?

Note: Based on the response of 51 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 72: “Has your institution implemented policy initiatives to analyse data for evidence-informed policymaking?”; Question 73: “Has your institution implemented policy initiatives to analyse data for evidence-informed policymaking?”; Question 74: “Has your institution implemented policy initiatives to use data to engage societal stakeholders in the delivery of policies and/or services?”; Question 75: “Has your institution implemented policy initiatives to adapt central/federal level public services according to the analysis data on citizen needs, preferences and use patterns?”; and Question 76: “Has your institution implemented policy initiatives to share and analyse data to boost public sector productivity and efficiency?”.

AIG’s SmartNation initiative shows excellent promise in terms of establishing data sharing within the Panamanian public sector with interoperability achieved between 72 institutions and some of the associated datasets being released to the population as OGD. However, with very few institutions providing examples of how data is being used to deliver cross-government services or improve existing services, there remain underdeveloped opportunities for adopting a DDPS culture to transform the citizen and business experience of government in the way modelled by OECD countries such as Portugal in Box 3.5.

This opportunity extends to the application of OGD for service delivery both within and outside of the public sector. Panama is an active participant with the Open Government Partnership and since 2012 has implemented several activities to support the Open Government agenda. One of the areas in which this has been successful is the creation of ANTAI in 2013 and the subsequent development of the national open government data website (Datos Abiertos de Panamá, www.datosabiertos.gob.pa). However, with the majority of datasets detailing budgeting, national statistics, legislation and procurement, this activity has centred on questions of transparency and accountability rather than the opportunities for broader social and economic value creation.

Weather forecasting data has been opened up and although universities have done studies with the data and it has been integrated into the SIAN platform by AIG to support the farming sector, it has not stimulated much interest from app developers. Those responsible for public transport and transport infrastructure in Panama City are sharing data with global service providers like Google and Waze as well as with citizens and government institutions helping to deliver better policies for developing these services. However, this has not yet translated into the emergence of localised innovative businesses supporting public policy or service delivery. Panama’s government should consider investing more in the opportunities for OGD by partnering with external collaborators for service delivery. As an example, the Ministry of Labour and Labour Development (Ministerio de Trabajo y Desarrollo Laboral, MITRADEL) has developed a platform to which over 500 companies post their employment needs and which then sources employees for them. The data that is associated with the roles employers are recruiting, the locations where they are looking and the skills which employers are looking for are an interesting source of data that could stimulate training courses, the location of a new business and even competitors in the jobs market.

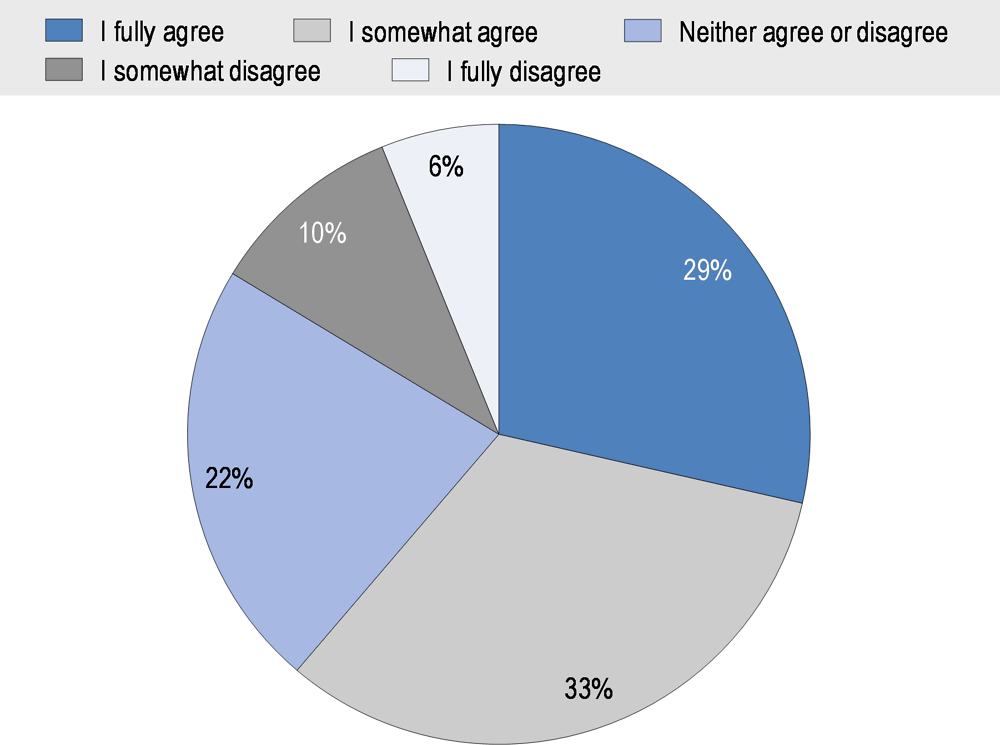

Happily, the survey indicated an appetite for pursuing this agenda with Figure 3.12 showing that 62% of institutions agree that “the potential and value of open data for the achievement of policy goals is acknowledged by the leadership of my institution”. Such a cultural receptiveness to the role of OGD can help to stimulate new services as well as the economy and provide support to the emerging OGD ecosystem by strengthening the relationship between academics, civic-minded software engineers and government’s own data practitioners.

Figure 3.12. How far institutional leadership acknowledges the potential and value of open data

Note: Based on the response of 49 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 91: “Respond to the following statement: The potential and value of open data for the achievement of policy goals is acknowledged by the leadership of my institution”.

Data-driven performance monitoring and evaluation

The third pillar of opportunities in a DDPS is the role of data in monitoring and evaluating the performance of government policies and services. In accessing real-time information about the way in which a service is being used, governments are able to respond to the demands of the public in a more timely fashion. Equally, when designing policy interventions, the importance of thinking about how to baseline, and then measure, the return on investment and impact of a given set of activities is important for understanding the value of an investment and consequently building trust and demonstrating accountability to the public.

Only AMPYME has identified the potential benefits to public sector productivity and efficiency in the use of data in their data strategy. MIDES, ANTAI and CSS were the only organisations with strategic objectives to consider how data might allow for continuous policy monitoring. Moreover, the peer review team encountered limited evidence of a strategic overview from the government as a whole in terms of data being used to understand and reflect on the continuous improvement of either policy or service delivery.

Box 3.6. Measuring the performance of digital government services in the United Kingdom

Transactions explorer

One of the early activities undertaken by the Government Digital Service after its founding in 2011 was to create an index of all government transactions. The Transactions Explorer was publicly available and listed transaction volumes against each responsible government organisation: the first version contained 671 services reporting 1.5 billion transactions a year.

The Government’s Digital Strategy

The UK published its Digital Strategy (United Kingdom Cabinet Office, 2013[25]) after this data had been collected and published. It was informed by what had been found and included three specific commitments for measuring the performance of government services:

1. All services with more than 100 000 annual transactions would be redesigned.

2. Creating a Service Standard against which all new or redesigned services would be measured.

3. Consistent management information about service performance.

Key Performance Indicators

To create consistent management information four Key Performance Indicators were developed:

Cost per transaction – to establish whether the end-to-end service was cost-effective.

User satisfaction – to identify the outliers where improvement should be focused.

Completion rates – see where there might be process flaws or ambiguities in the service.

Take-up levels – how is a digital channel performing relative to telephone or face-to-face options.

As this data was added to the list of services and transaction totals, it allowed a deeper understanding of the demand for government services and the identification of services where contracts, processes, or overheads raise further questions for research and discovery.

The Service Standard

Launched in 2014, the UK’s Service Standard guides services in their efforts to transform government services. Originally consisting of 26 points with 3 focused on reporting performance, it today is only 15 points with a single, comprehensive measure focused on collecting, measuring and publishing performance across the whole of a service and the end-to-end experience of users.

Towards a future of continuous improvement for the end-to-end experience of a service

Eight years on from the Transactions Explorer, the landscape of performance measurement is very different in the UK. The focus has shifted away from attempting to use four standardised metrics to capture performance and towards understanding end-to-end user journeys, including the interactions between digital and offline parts. The priority is measuring and improving whole services regardless of the channel being used, not individual online transactions.

Panama’s 311 Citizen Contact Centre (Centro de Atención Ciudadana) offers a valuable model for other parts of Panama to aspire to. It collects satisfaction feedback on every interaction with citizens and publishes a monthly, per-agency report on the volume of reports and performance in terms of case closures. Other than monthly institutional performance open datasets, this information is not made publicly available and so the Panamanian government should consider exploring how to increase its visibility with the public. Such transparency should not be understood as a way to highlight poor performance that could generate broader civic criticism but as an aid to ensure that empowered teams can apply the insights in support of evolving an improved service.

One of the most encouraging areas of data being applied to transform the government was the creation of an e-Government performance framework. The e-Government Indicators (Indicadores de Gobierno Digital) consist of 24 different digital government metrics (procedures, citizen attention, access to information, governance) embedded in current laws and aligned to well-known international indices, and 10 dimensions for central and local government digital transformation. These provide a means for Panama to look less at compliance with external indices and develop an internal framework for understanding performance and helping to prioritise the focus for transformation. The e-Government Indicators allow AIG to baseline its impact and look ahead to the next phase of Panama’s digital evolution. Data is collected relating to the satisfaction and performance of services and AIG publishes comma-separated values (CSV) files detailing the results of comparisons between institutions. Whilst near real-time dashboards are providing institutions and their ministers with insights into what is happening, its application for improving the delivery of services is not universal and depends on the commitment of a given institution to consider data in its approach to delivery.

It should not be considered sufficient just to measure on a periodic basis and publish this data; any of those measurements should be considered in light of how the insight can be applied to improve services or government. Therefore, the measurement approach should develop from the pure collection of statistics and become something that can hold people to account. Consequently, the performance framework should not only consider the user’s experience but the efficiency, impact and return on investment as well.

Data for trust

The way in which countries approach the digital government agenda influences the well-being of citizens in terms of being responsive to their needs, protective of their welfare and trusted to act with respect and competence (Welby, 2019[26]). Increasingly citizens are aware of the realities of how their data can be exploited and misused and have high expectations of government in its handling of their personal information. As a result, there is an imperative for governments to consider a range of issues including transparency, data protection, consent models and ethical approaches to the use of data in order to ensure that these approaches to data build trust rather than diminish it.

Transparency

The Panamanian Government has made commitments to the open government agenda through greater citizen participation, government accountability and increased transparency (Gobierno de Panama, 2014[7]). ANTAI has taken the lead, with AIG’s support, on efforts to increase the transparency of Panama’s public sector with several notable efforts:

1. Infrastructure Transparency Initiative – public infrastructure projects are disclosed into the public domain through a collaboration between government, industry and civil society. These reports are subject to periodic checks to assess the accuracy of what has been published, compliance with transparency expectations and the progress of a given project.

2. Reforms to public procurement law and standardisation of documents – Law No. 22 of 27 June 2006 (Asamblea Nacional, 2006[27]) establishes important principles in terms of streamlining and improving levels of transparency within the procurement system whilst legal documents for public procurement have been made more consistent.

3. OGD – as already discussed, Panama has implemented various efforts to support its publication.

4. PanamaCompra – the online procurement platform has gone through several iterations to support its users and make procurement more transparent.

5. PanamaTramita and the 311 Citizen Contact Centre (see Chapter 4: Channels for accessing services) – the creation of a single point of access and contact limits the ability for fraudulent or corrupt processes to be introduced into the experience of government.

The presence of extensive accountability data within the national open government data website (Datos Abiertos de Panamá, www.datosabiertos.gob.pa) indicates that Panama is making progress on the way in which the Government contributes to enhancing transparency in society through the data it publishes. Yet, the fact that the majority of those datasets detail budgeting, national statistics, legislation and procurement seem to reflect the fact that a greater focus has been given to questions of transparency and accountability rather than the opportunities to foster OGD availability, accessibility and reuse for broader social and economic value creation.

Data protection

An important development in Panama is Law No. 81 of 26 March 2019 (Asamblea Nacional, 2019[20]) which regulates the protection of personal data. Following Panama’s adherence to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime (Council of Europe, 2001[28]) in 2013, this is an important step in considering how to defend the rights of citizens and businesses in the safe and effective use of their data.

According to Figure 3.13, this legislation has had an impact on the priority of data protection and privacy in Panama. However, a number of institutions did not know about the forthcoming law and others expressed concern that the legislation may lack meaningful enforcement measures. This emphasises the importance of implementing an independent Information Commission to regulate the way in which the public sector, or businesses, handle data and to whom the public can appeal in the event of any concerns about the use of that data. Nevertheless, this important building block allows Panama to work with a consenting public to make full use of data in ways that encourage trust.

Furthermore, the creation of this framework reflects the global attention being surfaced through the creation of transnational data protection frameworks including the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (European Union, 2016[29]). As Panama contributes to the regional digital government conversations of the e-Government Network of Latin America and Caribbean (Red de Gobierno Electrónico de América Latina y el Caribe, Red GEALC), there are opportunities to build on the OECD Recommendation of the Council concerning Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data (OECD, 2013[30]) and explore how to achieve a similar, regional, approach to cross-border data sharing (see Chapter 4: Cross-border services).

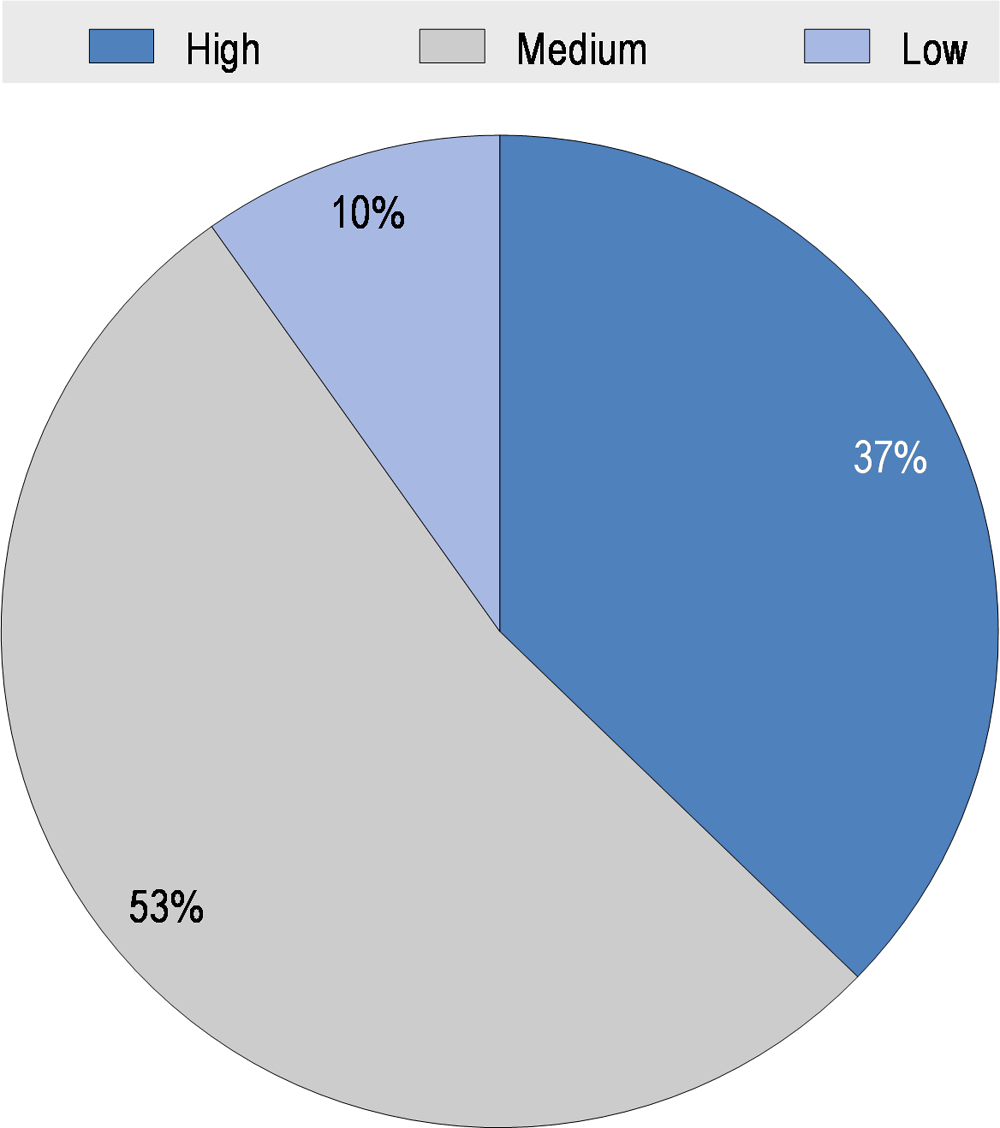

Figure 3.13. Priority of data protection and privacy in Panama’s digital government agenda

Note: Based on the response of 51 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 81: “How would you describe the level of priority given to privacy and personal data protection in your country’s digital government agenda?”.

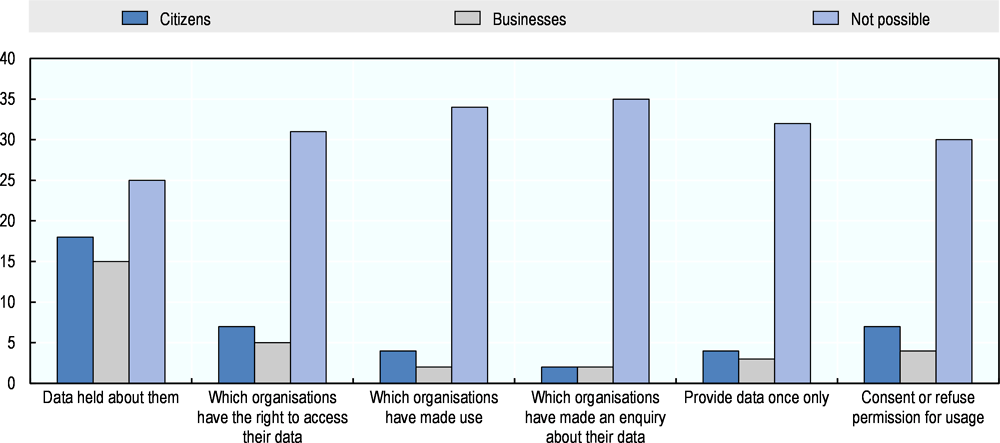

Figure 3.14. Extent to which citizens or businesses are able to view how their data is used

Note: Based on the response of 45 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 84: “Please check the boxes in the table below to indicate whether citizens and businesses can do the following in practice (e.g. through a website or a mobile application)”.

Seeking consent from citizens and managing government’s access to their data

A further way in which the role of data can influence the trust of citizens is the mechanisms by which governments allow citizens to provide consent for their data to be reused by other parts of government and to manage that access on an ongoing basis.

As Figure 3.14 shows, there is currently only limited provision for either citizens or businesses in having practical means for managing access to their data. Twenty-five of the 45 institutions that answered this particular question offer no way to identify data held about the requesting citizen or business. Even amongst those that responded positively, it was clear that there was no simple route to obtaining this information for a citizen or business. The Judicial Branch (Órgano Judicial) highlighted that everyone in Panama has the right to request information from public institutions or private companies that provide a public service. This is coupled to a right for requesting the State to correct or eliminate information that is incorrect, irrelevant, incomplete or outdated. Should such a request not be actioned in 30 days then it is possible to escalate the issue and make a request for Habeas Data to the Judicial Branch (Órgano Judicial). It is similarly difficult for citizens or businesses to discover which organisations have the right to access their data or have used or enquired about it. Although a handful of organisations suggested that it was possible for citizens or businesses to provide data only once or consent and refuse permission for usage, there was no evidence provided to support this.

Box 3.7. Carpeta Ciudadana

In Spain, Carpeta Ciudadana enables a citizen to know and control access to their data by public organisations. It provides a summary of the citizen’s information grouped by subject and displays the number of files currently open, or in the pipeline, at the time of their query, grouped by ministry or agency. It then links the user to further details about the files.

Carpeta Ciudadana shows information about the exchange of information between public organisations and the condition of consent placed upon it. The list of data that has been requested and shared with administrative bodies to complete a formality or query also displays whether the citizen has given explicit or tacit consent for its re-use.

Carpeta Ciudadana is not just focused on the digital experience of the citizen, additionally presenting logs of any face-to-face interactions between the citizen and public administration.

Source: Information provided by Spain to the OECD.

Following the implementation of GDPR, European Union member states are now obliged to consider the needs of citizens in communicating how their data is being used. For some countries, such as Spain (Box 3.7), this extends mechanisms that were already in place, whilst for others it necessitates a new approach to this interaction. Although Panama is not covered by GDPR, the lessons that are available for considering how citizens might grant consent and manage access are important, particularly in the context of Panama’s ambitions for expanding and enhancing digital identity (see Chapter 4: Government as a Platform capabilities).

Ethics

As governments explore the opportunities to disrupt the existing way in which services are delivered through the application of technology, data becomes an important raw material. The exchange of data from one organisation to another may add value but it also means data being used in ways that may not have been clearly stated when it was first collected. Moreover, as governments put data to work in anticipating the future demands of a country, it is important that any personal data is anonymised and that, as far as possible, bias is identified and understood. This is especially true when it comes to the role of machine learning and the data being used to train neural networks. Whilst algorithms can provide powerful ways for delivering services more quickly and distilling more information than humans could, it is not without its risks (van Ooijen, Ubaldi and Welby, 2019[3]; O’Neil, 2016[31]).

Around the world, different countries and organisations are exploring how they might define and enshrine an ethical approach to the role of data in designing policy, delivering services and evaluating performance with traditional methods, or via the transformation offered by disruptive technology. Several countries and organisations have given a focus to the ethical use of data in the specific context of artificial intelligence (AI). The Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on the DDPS is collecting the experience of its participant members with the aim of developing a distilled framework for ethics more generally within the DDPS.

In Panama, a Basic Course in Ethics for Public Servants has been devised as part of the Open Government agenda. It seems to introduce, improve and consolidate knowledge for public servants on ethics and anti-corruption that promote standards of conduct and provide the necessary skills to prevent, detect and denounce it. However, this does not broaden out its scope to consider the treatment of data in designing and delivering policy and services.

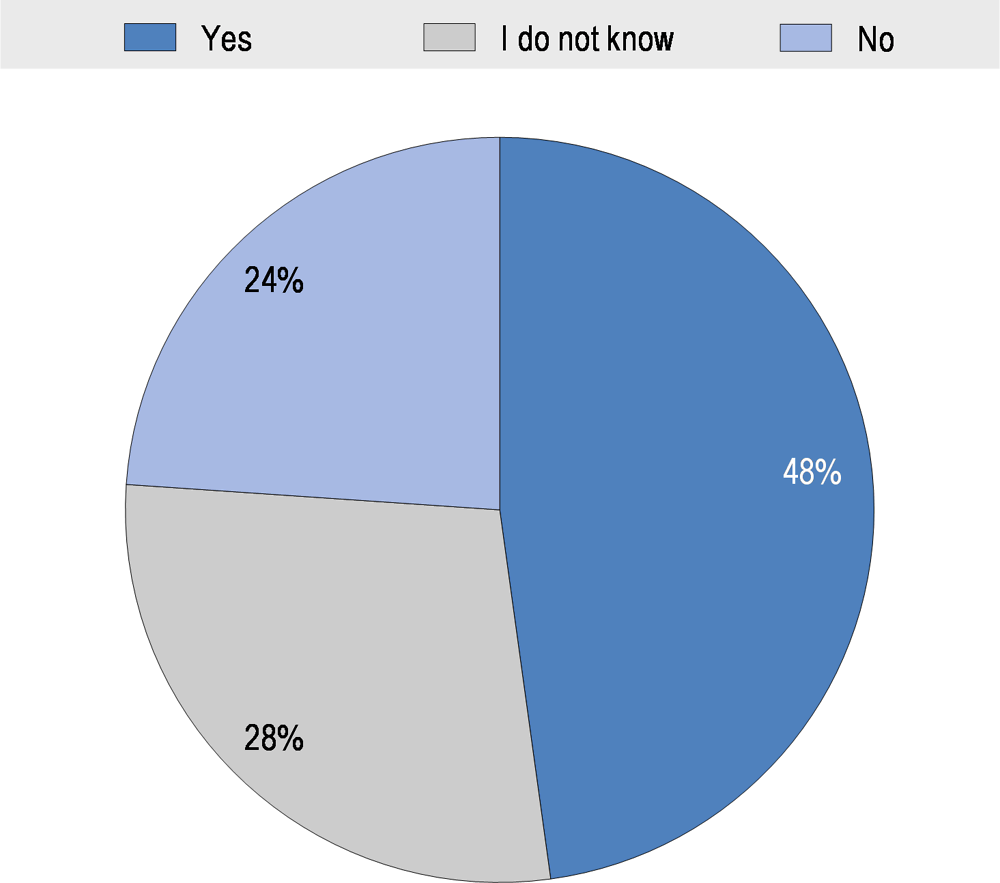

Figure 3.15. Institutional appetite for support with data ethics

Note: Based on the response of 46 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[12]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 80 e): “Would you benefit from central/federal government support on data ethics?”

Nevertheless, one in three of the institutions surveyed for this review understood that there was an expectation on them and requirement to ensure data is managed and used in an ethical way. Central support is available to these organisations but only 5 of the 51 organisations had made use of it, this was despite 22 organisations expressing an appetite for support in this area (Figure 3.15). In terms of those needs the following areas were highlighted:

support with collecting and disclosing data, especially regarding confidentiality and data protection

policies about how data should be governed within institutions

additional budgetary support to implement data related policies and establish the necessary technical infrastructures.

These responses highlight the importance of Panama extending the resources available for building capability and efforts to raise awareness about the support and services AIG can offer.

References

[13] 115th Congress of the United States (2019), Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/4174/all-actions?overview=closed#tabs.