This chapter analyses the service design and delivery landscape in the Panamanian public sector. It discusses the existing culture for service design and delivery, and details the resources and enablers that support delivery and adoption. The chapter highlights the challenges of digital inclusion including the country’s connectivity infrastructure, digital literacy and accessibility. It then considers Government as a Platform capabilities including the channels for accessing services, standards and guidance and digital identity (DI). Finally, the chapter looks at the issues of data and interoperability, emerging and disruptive technologies, and the potential for cross-border services in the Latin America and Caribbean region.

Digital Government Review of Panama

4. Service design and delivery

Abstract

Introduction

Service delivery is the central point of contact between a state and its citizens, residents, businesses and visitors. It has a major impact on the efficiency achieved by public agencies, the satisfaction of citizens with their government and the success of a policy in meeting its objectives. Alongside confidence in the integrity of government, the reliability and quality of government services is an important contributor to trust in government. The quality of these interactions between citizen and state shape not only their experience of government, but influence the opportunities they access and the lives they build.

In this context, users are unforgiving of services that compare poorly with experiences of high-quality delivery, whether from the private sector or elsewhere in government. To meet rising quality expectations, particularly in the digital age, governments need to focus on understanding the entirety of a user’s journey across multiple channels, as well as the associated internal processes, to transform the end-to-end experience. Doing this may require adjusting and re-designing processes, defining common standards and building shared infrastructure to create the necessary foundations for transformation as well as ensuring the interoperability of public agencies to facilitate the data flows that will make integrated, multi-channel services possible.

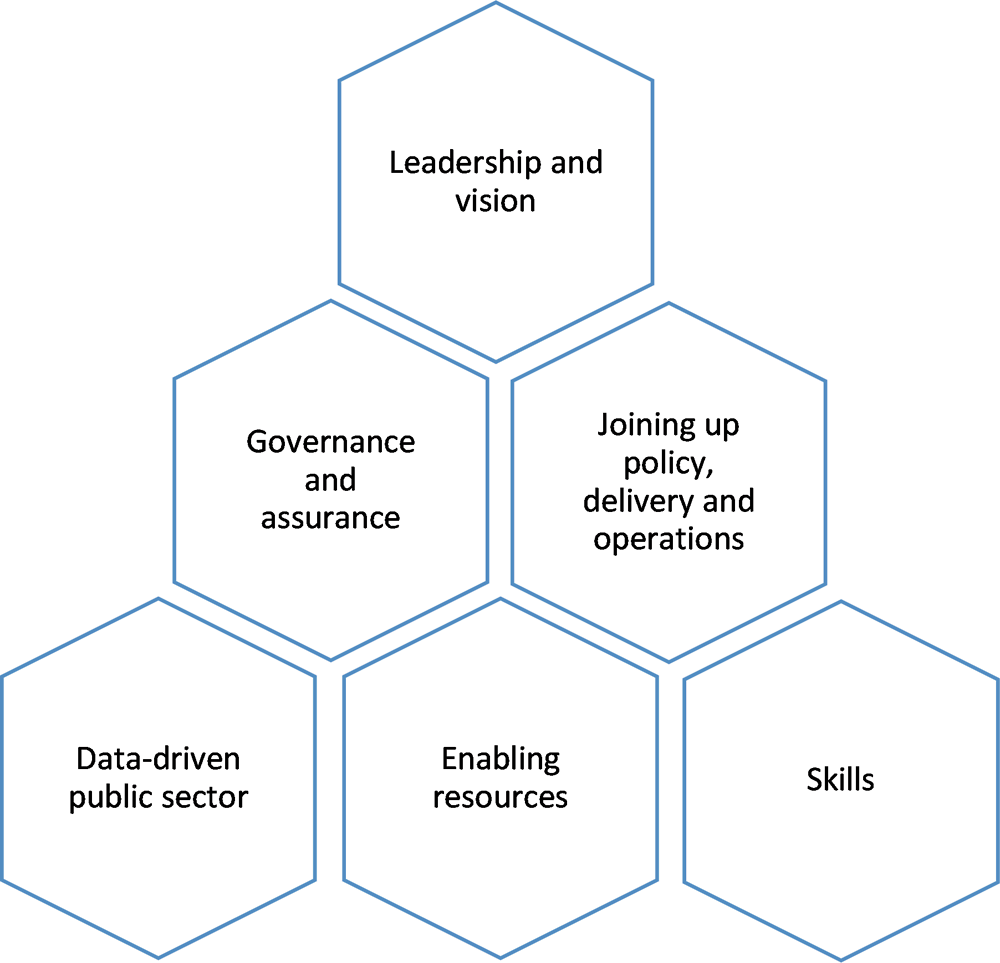

Figure 4.1. Foundations for transformed service design and delivery

Establishing a vision for the transformation of service design and creating the necessary conditions for successful delivery require several important foundations to be in place (Figure 4.1):

1. Leadership and vision: politicians recognise the application of digital, data and technology at the heart of the country’s future, establishing an agenda that is shared by all ministers and the leadership of the public service to understand the needs of citizens and include them in designing their resolution.

2. Governance and assurance: there is a clear definition of “good” in respect of services and a credible approach to quality assurance. Multiple delivery partners can work towards a shared ambition, governed by controls on spending and criteria detailed in “‘Service Standards”, informing how teams approach the problems of their users.

3. Joining up policy, delivery and operations: rather than policy being designed by one team, a service being commissioned from a supplier and, on launch, being handed over to a third team; transformed services are built by multi-disciplinary teams that bring together different perspectives. Uniting what might otherwise be siloed individuals as a team, focused on solving a particular problem together.

4. Data-driven public sector: transformed services are hard to achieve without a strategic approach to the role of data where it can be readily shared within government and its quality assured to support innovation. As a result, services are developed that do not just replace existing processes but redesign them bringing value, both to providers (i.e. public sector organisations) and users (see Chapter 3).

5. Enabling resources: technology should be seen as a way of helping to support teams meet the needs of citizens rather than an end in itself. The central provision of enabling technology and other resources can meet common needs, such as those around identity or hosting, or provide guidance on best practice approaches.

6. Skills: the redesign of services can reshape the roles required to meet the needs of citizens. There may be a need to retrain long-standing members of staff or expand the profile of roles within government and find ways to work towards a common purpose with their supplier ecosystem (see Chapter 2: Digital culture and skills in the public sector).

In the case of Panama, these six areas are being addressed to greater or lesser extents. This chapter will consider the existing culture of service design and delivery in Panama before assessing the resources that support efficient and innovative service delivery. This will look at connectivity and inclusion, Government as a Platform (GaaP) capabilities, data and interoperability, emerging and disruptive technologies, and cross‑border services.

Culture for service design and delivery in Panama

Policies and laws

The Panamanian Government (Gobierno de Panama, 2014[1]) has set out the objective for Panama of providing efficient and effective government services in three ways:

1. Providing efficient and effective personalised government services available to all citizens at no cost that are transparent, simplified, timely and free from corruption.

2. Transform the management of public services to encourage greater participation of the public and demonstrate greater transparency of government.

3. Consolidate many of the similar responsibilities of the state to create single entities with responsibility for a given subject.

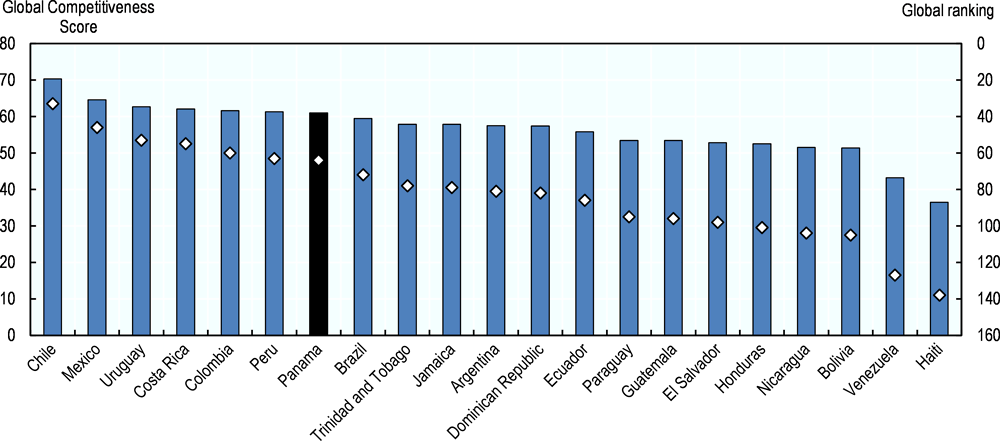

These objectives create the environment in which Panama has considered its priorities for delivering new and transformed services. The National Secretariat for Competitiveness and Logistics (Secretaría Nacional de Competitividad y Logística) and the Centre for National Competitiveness (Centro Nacional de Competitividad, CNC) identify areas where the country needs to improve its performance according to indices provided by organisations such as the World Economic Forum (Figure 4.2) (World Economic Forum, 2018[2]) and the World Bank (The World Bank, 2019[3]).

Additionally, in line with Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012 (Asamblea Nacional, 2012[4]), each institution is also expected to set out its annual plans for the simplification of procedures (see Box 4.1). These plans are expected to contain projects that improve the relationship between businesses and citizens, reduce bureaucracy and increase productivity. Central to the success of those plans is the ambition of Panama en Linea (PEL) to unify and consolidate efforts for meeting the needs of citizens and companies.

Figure 4.2. The World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index 4.0

Note: Top 10 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean Global Competitiveness Index. Overall ranking is shown on the secondary axis.

Source: World Economic Forum (2018[2]), The Global Competitiveness Report 2018, https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-competitveness-report-2018.

Box 4.1. Decree on Simplification of Procedures

In accordance with Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012, Executive Decree No. 357 of 9 August 2016 establishes that institutions are required to prepare a plan for the simplification of procedures. In those plans, institutions list and categorise processes according to the following criteria:

1. Level 1: The procedure is listed on PanamáTramita.

2. Level 2: A form can be accessed through PanamáTramita, downloaded, filled out and taken to the relevant institution.

3. Level 3: A form can be accessed through PanamáTramita and while the process can be initiated on line through Panamá en Linea (PEL), a face-to-face visit to the institution must be carried out to complete it.

4. Level 4: The process can be completed via PEL and tracked through PanamáTramita.

5. Level 5: The procedure has been eliminated and no action is required by the citizen to meet this need.

Two levels of digitalisation are defined – either with or without reengineering. This makes it possible to identify those processes where immediate value can be added by simply putting the interaction on line against those services that would benefit from a longer-term redesign and reengineering.

These efforts are supported by the 311 Citizen Contact Centre (Centro de Atención Ciudadana) which facilitates citizens and businesses to make suggestions for improvements to procedures and a route to reporting any institution that requests a document that is not listed on PanamáTramita. The Executive Decree also requires an institution to justify any new procedure before its implementation and sets out the process by which a citizen or business might challenge its introduction.

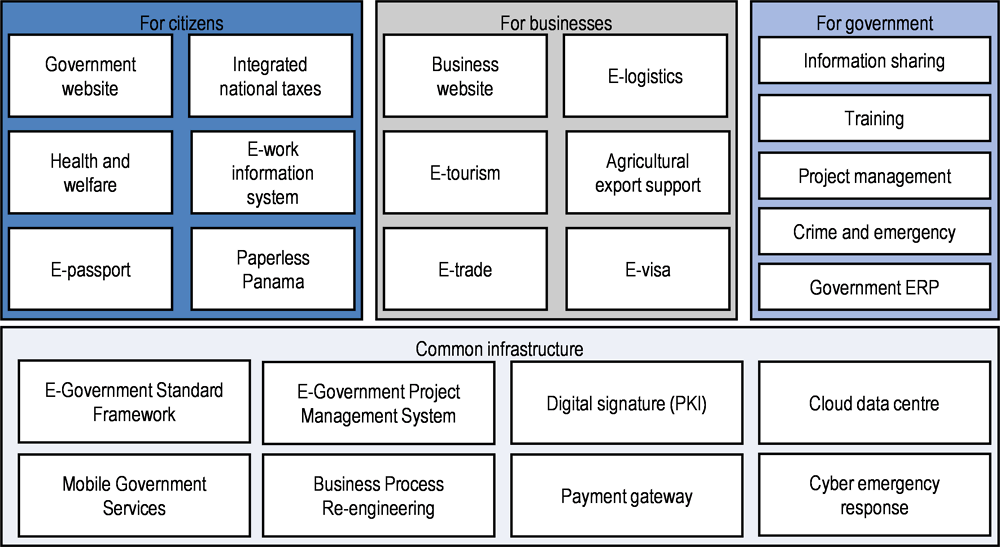

Figure 4.3. AIG provided applications and platforms

Source: Autoridad Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental (2016[5]), Agenda Digital 2014‑2019 Panamá 4.0, http://innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Agenda_Digital_Estrategica_2014-2019.pdf.

Practices and tools

Additional priorities are set by AIG in terms of identifying the 450 most important procedures and forms as well as the development of multi-channel applications and cross-government technical platforms. Those technical platforms (Figure 4.3) cover four areas: citizens, entrepreneurs, government and common infrastructure.

In 2012, AIG began working with the Justice system in Panama to transform the experience of justice across its several branches of government. This collaboration involved all the necessary stakeholders and saw a transformative approach taken to the end-to-end experience in delivering the Accusatory Penal System (Sistema Penal Acusatorio, SPA). They took the existing, complex process and broke it into its constituent parts in order to arrive at an understanding of the needs of both those accessing the services and those providing them. This made it possible to prioritise particular elements of the journey and address different elements over time. By 2018, this resulted in transforming not only existing digital elements but also the issues related to physical infrastructure and analogue interactions in the entire experience of justice. There is no longer any paper involved and, according to information obtained during the fact-finding interviews, it has reduced the time involved by 96%. This kind of end-to-end transformation that addresses the entirety of a service in both its back office and public facing experiences provides an aspirational model for the rest of Panama, and other countries, to follow.

However, apart from this excellent example, the language and characteristics of service design were less visible in the way in which public servants in Panama discuss their approaches to transform service delivery. AIG’s vision and strategy for providing the support required to deliver services in Panama are technology-led. Achieving successful digitisation and administrative simplification is equated with the implementation of common technology providing online access to government rather than in a design-led transformation of the underlying services. Several of these platforms are well used but there is a danger of seeing platforms and technology proliferate to solve ad hoc needs rather than strategic efforts to join up government and design end-to-end services.

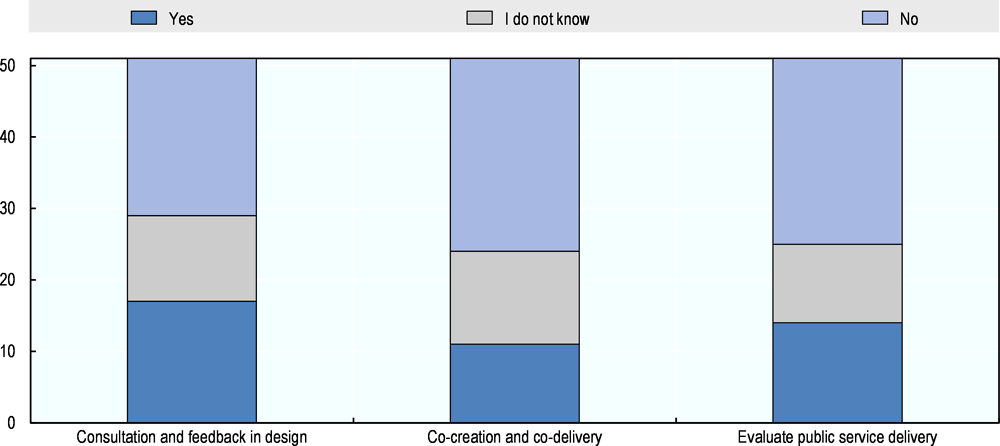

Figure 4.4. Extent to which institutions have formal policies for consultation and feedback, co-creation and co-delivery, or evaluation of public service delivery

Note: Based on the response of 51 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[6]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 37: “Is there a formal policy in your institution for Consultation and feedback in public service design?/Co-creation and co-delivery of public services?/Evaluation of public service delivery?”.

The language of teams and the process by which prioritisation happens is not reflective of users’ needs. This is reflected in the survey of institutions where, as Figure 4.4 shows, only 33% (17 out of 51) of institutions have the expectation of involving the public in consultation over service design, 27% (14 out of 51) do so in the evaluation of services and 22% (11 out of 51) in pursuit of co-creation. As a result, apps and different technologies are being built that respond to particular problems rather than considering more strategic design questions such as the importance of resolving barriers to the implementation of the once-only-principle for data exchange and a channel agnostic approach to services that reflects the diversity of the country’s population. Although there are examples of involving the public and putting them at the centre of shaping certain outcomes, the dominant culture of service design and delivery in Panama is not one that gives the public a sizeable voice.

This lack of decision-making based on an understanding of the needs of citizens highlighted that government tends to be more reactive to needs that come up in the course of implementing its agreed direction rather than proactively focusing on what is important and strategically thinking about how best to deliver the transformation of Panama’s public services in general. The voice of the private and public sectors is represented through an annual public-private dialogue between AIG and the CNC facilitated as part of the National Competitive Forum (Foro Nacional para la Competitividad), as well as special working groups and a study commissioned by AIG to CNC. However, the OECD peer review team found little evidence of actively making space for citizens to inform the understanding of their needs or contribute to the ongoing design and development of their services. The notable exception was the citizen survey commissioned by AIG for the CNC in identifying the priorities for simplification, which generated over 1 000 responses and benefitted from accessing citizens through the InfoPlazas network (see Chapter 4: Digital inclusion).

Capturing an understanding of the needs to which existing services have been responding is critical to prioritising future transformation efforts. Increasing the involvement of citizens can also generate the momentum for adoption. Several stakeholders recognised that awareness of some of the services, and the transformation which the Panamanian government has achieved, is low amongst the public. One response is Panama’s plan to invest in a communication campaign from June 2019 to promote these activities whilst another is to fund activities within the InfoPlazas network focusing on the digital skills of communities in order for them to be comfortable in transitioning to an online experience.

Government services are generally needed at a point in time rather than being offered as a consumer product and should not be judged on the same metrics of success in terms of repeat visits or time on site. The priority, therefore, is to design a service that meets needs and is delivered in a coherent, readily accessible way. The key to unlocking adoption is to provide services so good that people choose to use them, rather than needing to spend a lot of effort in persuading them to shift channels. Building a culture within Panama that places users at its heart and is driven by their needs will ensure that the government’s efforts to transform services are well received by the public and can promote public trust.

The ambition for a coherent and pan-governmental transformation of Panama was stated on several occasions. For AIG this may require moving beyond the softer behaviours of consensus building and consultancy on request towards a bolder and more directive set of strategic activities such as a service standard with an associated assessment process that develops and enforces the delivery practices of the ecosystem to transform Panamanian government services.

Providing the resources and enablers that support delivery and adoption

Support for the design and delivery of services comes in many forms. These activities meet the needs of service teams in the work of researching, designing and implementing a given approach but also speak to the challenges of adoption and ensuring that the public experience the benefits as fully as possible.

For the public, this can take the form of enhanced connectivity and increased digital literacy, single government domains that rationalise and unify the information provided by government, or common branding for non-digital service channels such as telephone call centres or face-to-face locations.

In the case of government teams, the resources that make it easier to deliver proactive government services include the interoperability and ease of sharing data (as discussed in Chapter 3), the enabling role of innovation and disruptive technologies and the provision of reusable solutions to common problems. However, the opportunities for collaborating with resources like these can sometimes rely on serendipity and prior relationships to discover what might be available. During the OECD peer review mission, the review team held one meeting where the participants discovered a solution to a long-standing problem because they had been brought around the table together; this is not efficient or sustainable and Box 4.2 discusses how the United Kingdom has implemented a “Service Toolkit" approach to surfacing these reusable resources.

In this section, the review considers questions of digital inclusion, Government as a Platform capabilities, data and interoperability, emerging and disruptive technologies and innovation, and cross-border services.

Digital inclusion

Digital divides are a significant obstacle to the successful and effective delivery of digital government strategies. As such, countries should not focus on following a “digital by default” approach that excludes all other routes to accessing government services except for digital ones, no matter how well designed they are. Nevertheless, governments should consider the role of digital infrastructure, digital inclusion and accessibility in their digital government efforts.

Box 4.2. The United Kingdom’s Service Toolkit

In the United Kingdom, the digital transformation of government is led by the Government Digital Service (GDS), a part of the Cabinet Office. As a central function, they provide leadership, set standards, offer guidance and build technological solutions. Collectively, these resources form a Government as a Platform ecosystem of support and reference that enables service teams to deliver more effectively.

Although GDS has a remit within central government, the value of their work is recognised across every level of the UK’s public sector, making it essential to provide a reference point for the different resources that they provide. This is done through the Service Toolkit, a single page bringing together all the things that are available to help teams building government services.

The Toolkit contains links to:

1. Technology and digital standards.

2. Guidance on specific technology and digital topics as well as design and style guidance for using the UK’s single domain and common approach to design.

3. GOV.UK services – technologies available to teams building and running government services like payments, notifications, digital identity and data registers.

4. Monitoring services for data on service performance.

5. Buying skills and technology for building digital services.

Each of the things that are included within the toolkit are the responsibility of a team who consider how to continually make these standards, guidance and tools better suited to the needs of colleagues within the public sector. Adopting this “product” mentality to internal resources is a valuable means of prioritising development and removing the obstacles that reduce the impact and effectiveness of the collected resources.

Source: GOV.UK, Design and build government services (https://www.gov.uk/service-toolkit)

Connectivity infrastructure

There have been important interventions to extend the ability to get online throughout the country in ways that in some cases benefit the public and in others government actors. Underpinning Panama’s digital infrastructure is the advanced connectivity offered by six fibre optic submarine cables. One of the opportunities for public sector organisations is in nationally available cloud infrastructure, the Government Cloud (Nube Computacional Gubernamental, NCG) and the National Multi-service Network (Red Nacional Multiservicios, RNMS) which securely connect government through more than 4 000 data links managed by AIG.

Of the institutions surveyed for this review, 41 knew of its availability to some parts of Panamanian society whilst 18 were using it themselves. This state-provisioned, Panama-based, secure and private cloud is available for all institutions, obviating the need for them to develop such solutions themselves. In the case of municipal governments this is particularly important, as 90% of them do not have the budget to consider developing what might be needed. All that is charged are the costs of cloud consumption. The ambition is for NCG to be the platform for all government software covering Infrastructure as a Service, Platform as a Service and Software as a Service capabilities.

Law No. 59 of 11 August 2008 (Asamblea Nacional, 2008[7]) to promote universal access to ICTs created the National Internet Network (Red Nacional Internet, RNI) to implement Internet connectivity across the country. With 39.3% of Panamanian society lacking Internet access at home (International Telecommunication Union, 2018[8]), the RNI allows every citizen access to free Wi-Fi on their personal devices within certain filtering parameters to protect citizens and guard against misuse. This network for connectivity now provides 86% of the country’s population with free access to the Internet and there are ongoing ambitions for this to increase in line with the National Broadband Plan (Gubernamental/IDB, Autoridad Nacional para la Innovación, 2013[9]).

Digital literacy

One significant intervention in attempting to close the digital divide in terms of the inequality between those who may have access to the Internet or knowledge of its benefits, compared to those who do not, is the InfoPlazas programme operated by the National Secretariat of Science, Technology and Innovation (Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, SENACYT) and funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, 2015[10]). Whilst the RNI is an important effort in providing access to Internet for the 39.7% of Panamanians without access in their homes, the 312 InfoPlazas have a remit that is more than Internet access alone in offering training and building knowledge to take full advantage of online services. Furthermore, this nationwide network could offer the ideal setting in which to involve local communities and citizens in the discovery of needs and development of solutions to their problems.

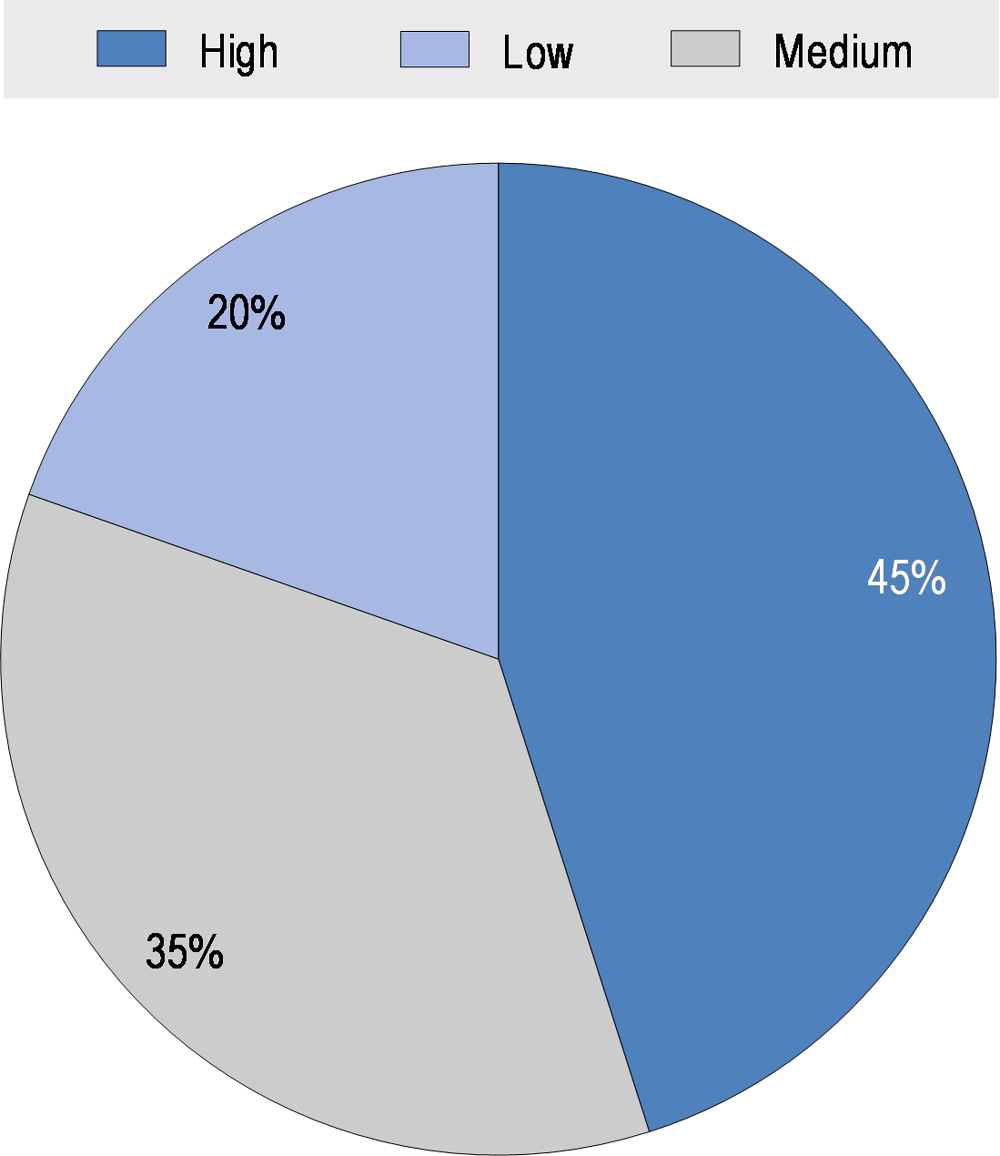

The InfoPlazas network is a valuable piece of physical infrastructure to support digital literacy, entrepreneurship and other cross-government agendas as well as for encouraging more proactive and user-driven approaches. It should be seen as a critical enabler for the 41 out of 51 institutions in Figure 4.5 that view digital inclusion as a medium to high priority, with the greatest focus being on rural communities, those with low income and indigenous communities.

Figure 4.5. Priority of digital inclusion in Panama’s digital government agenda

Note: Based on the response of 51 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[6]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 39: “How would you score the priority given to digital inclusion in your country digital government agenda?”.

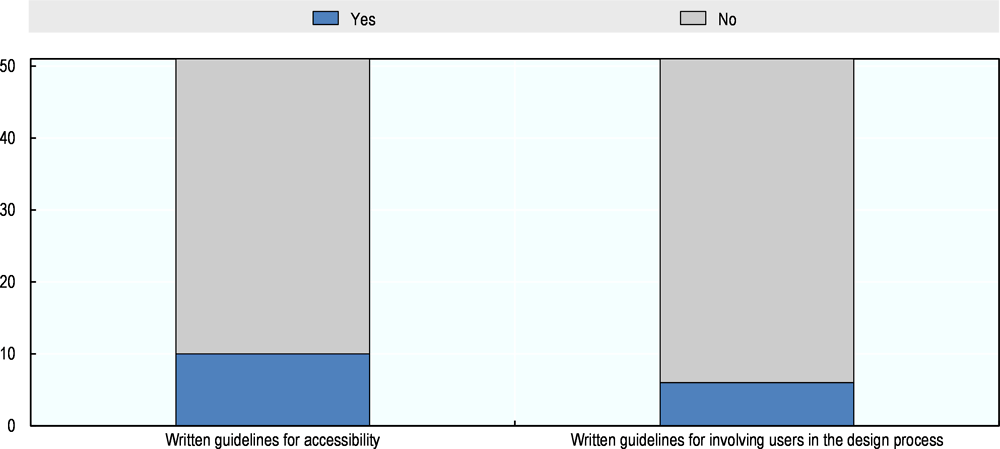

Accessibility

Alongside the connectivity to access the Internet and the skills to be able to enjoy its benefits, a third important area of inclusion is the accessibility of services. Such is the priority of this issue that countries often pass legislation to ensure access in the context of the built environment, even whilst it is overlooked when it comes to digital services. Panama is no different with Figure 4.6 showing only ten organisations were aware of written guidelines concerning accessibility. This should be seen as a priority for Panama to address, perhaps by emulating the experience of the European Union (EU) where the Directive on the Accessibility of Websites and Mobile Applications has enshrined in the law the requirement for websites and mobile apps to meet common accessibility standards built around the four principles of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 (European Union, 2016[11]).

Figure 4.6. The existence of centrally produced written guidelines for accessibility and engagement in Panama

Note: Based on the response of 51 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[6]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 41: “At the central/federal level, do you have written guidelines regarding accessibility of digital government services to meet all users’ preferences/engagement of final users in the service design process?”.

Government as a Platform capabilities

Several countries around the world have been exploring a Government as a Platform approach to meeting the frequently experienced challenges of delivery government services by providing common, reusable capabilities. The OECD defines it as “building an ecosystem to support and equip public servants to design effective policy and deliver quality services that also encourages government to collaborate with citizens, businesses, civil society and others” (Welby, 2019[12]). The ecosystem being established in Panama provides several valuable contributions that support the delivery of services, but it is not yet providing a full complement of such capabilities.

Panamá en Linea (PEL) is best understood as two separate projects working together: first, PanamáTramita, a list of all government procedures and requirements that provides the necessary information for citizens to complete the interactions and make requests of government; second, the technical platforms which allow for the development of government procedures, an authentication mechanism and the technical support for interoperability. It hints at an ambition for the future where there is a seamless user experience from the perspective of the citizen.

The transaction engine that sits behind PEL makes it possible for institutions to develop procedures and create services based on an associated workflow. This platform is designed to make it possible for government institutions to develop the skills of their own staff to maintain and deliver new online services. This technical solution to the challenge of developing an online workflow is complemented by work on process mapping that has produced a blueprint for 450 procedures and developed a mechanism for understanding the existing landscape of services in Panama.

Several platforms have been implemented to provide support in different sectors. In the health sector, there is a collaborative effort to digitise health records with participation from both public and private sector actors. At a local level, Municipios Digitales has facilitated the implementation of a standardised website for 74 out of the country’s 77 municipal authorities. In addition, the OpenBravo Municipal Government Resource Planning platform (covering financial, administrative and integrated accounting systems) has been implemented in 66 municipalities allowing for interoperability and the development of online procedures and payments through the PEL platform. This has allowed municipal governments to focus on the needs of their users rather than developing systems. Moreover, the National Payments Portal (Portal Nacional de Pagos) offers a single route for consolidating all debts across the public sector whilst the Document Management System (Sistema de Gestión Documental) platform provides a secure and confidential way of distributing electronically signed, official documents.

AIG is investing in central capacity to manage the platforms and applications that have been developed. This ensures new initiatives can be explored whilst ensuring that the Government as a Platform service offering remains reliable and of high quality.

Channels for accessing services

The ambition of the PEL agenda is to create a single route into accessing government services acting as a common brand that can support citizens in navigating the complexity of government and not needing to understand its structures. However, whilst these technical platforms may support the digitalisation of government interactions, there is not yet a single route into their access or rationalisation of the web estate for Panama’s public sector.

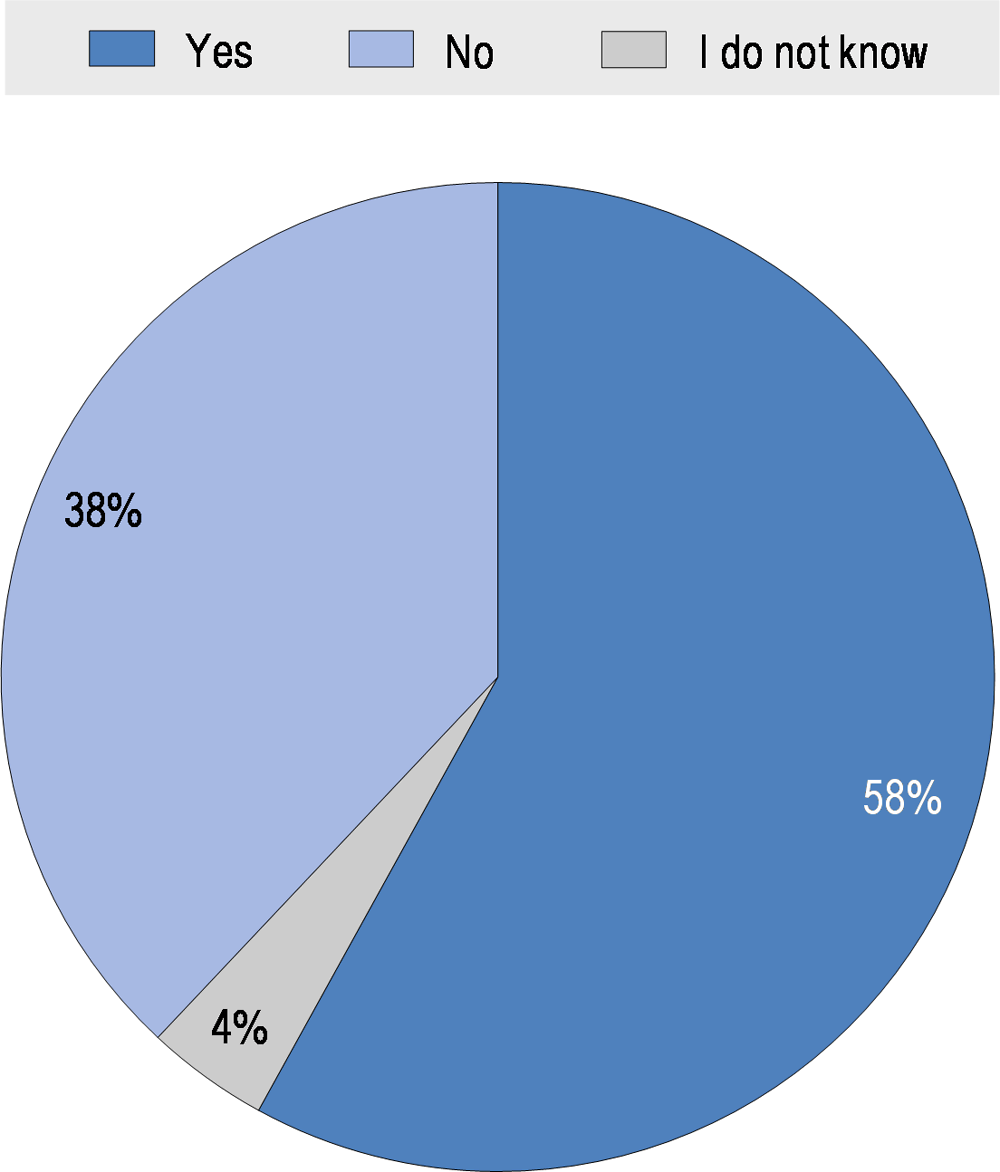

Figure 4.7. Inclusion of institutional digital services within PanamáTramita

Note: Based on the response of 50 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[6]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 51: “Are the digital services provided by your institution showcased and/or available in the main national citizens and/or businesses website for government services?”.

An important foundation for service delivery in Panama has been the development of the website PanamáTramita (www.panamatramita.gob.pa/). In indexing the 2 700 procedures which take place between citizens or business and central government and another 1 463 with the local government, it is creating an important map of activity within the government that can provide the basis for prioritising any future transformation of the state. As established in Executive Decree No. 357 of 9 August 2016, any new procedure or additional requirements must be justified before they are included within PanamáTramita, which prevents public officials requesting documents or creating new processes that are not already detailed, limiting the growth of bureaucracy. However, whilst PanamáTramita may be an effective catalogue of services, it is not the only way for them to be accessed. Figure 4.7 shows that 69% (29 out of 42) of public service-providing institutions include their services on PanamáTramita. This means that a third of organisations do not.

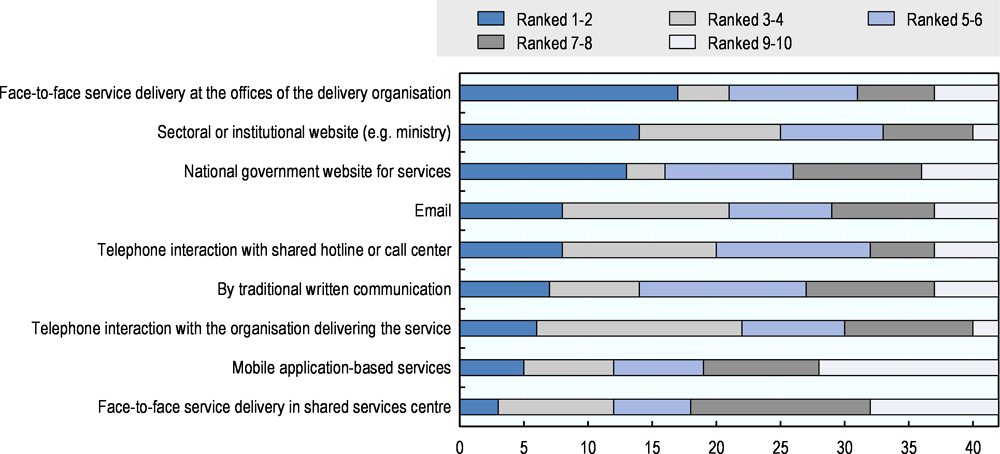

Moreover, Figure 4.8 shows that there is a preference amongst the institutions for services to be accessed through their own specific websites rather than the centralised site. Although Panama has developed a strategy of providing all services through the single access point of PanamáTramita, the persistence of separate, institutional websites has the potential to confuse users and undermine those strategic efforts at common branding and consistent user experiences.

Figure 4.8. The relative importance of different channels in accessing services in Panama

Note: Based on the response of 42 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[6]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 46: “Please indicate the relative importance of each of the following channels in delivering transactional services for your institution”.

Figure 4.8 also demonstrates the importance of non-digital channels in Panama with particularly strong support for the ongoing provision of face-to-face channels through the offices of the organisation delivering the service. However, the lowest recorded enthusiasm was for shared service centres, like InfoPlazas. As seen in Box 4.1, it is only at Stages 4 and 5 that the need for a face-to-face interaction is removed and whilst the desire will exist for users to shift away from the more expensive and less efficient physical interactions, it is clear that there is an ongoing appetite for these channels. Indeed, for those organisations prioritising the digital channel, there was a consistent drop in their promotion of telephone and face-to-face interactions.

The online channel is complemented by the 311 Citizen Contact Centre through which citizens have free access to all institutions at every level of the Panama public sector 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Through this channel, citizens can make complaints or report problems, propose ideas and enquire about particular issues whilst also carrying out procedures with the state. Crucially, the 311 Citizen Contact Centre also maintains a record of all events carried out between a citizen and the government, allowing for a single view of the user and their experience with government.

However, despite these efforts to create that single view of a citizen from the perspective of the government, the same is not the case when the government is seen by the public. Whilst the 311 Citizen Contact Centre is an effective single front door for Panamanian services, it does not share the branding of PEL and is potentially a further source of competition to the various websites or proliferation of platforms and apps elsewhere. There is, therefore, something of a fragmented user experience with competing institutional channels for different services, indicating that the importance of designing good end-to-end services is not always understood at an institutional level.

Box 4.3. Thematic Group on the Design and Delivery of Services

In 2017, the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on the Design and Delivery of Services set out to revise the best practices and main challenges for providing digital services and improving the experience of citizens when interacting with government. Bringing together the experiences of Australia, Canada, Chile, Egypt, Mexico, New Zealand, Portugal and the United Kingdom they proposed the following General Digital Service Design Principles:

1. User-driven: optimise the service around how users can, want or need to use it, rather than forcing users to change their behaviour to accommodate the service.

2. Security and privacy-focused: uphold the principles of user security and privacy whenever a digital service is provided.

3. Open standards: prioritise freely adopted, implemented and extended standards.

4. Agile methods: build services using agile, iterative and user-centred methods.

5. Government as a Platform: build modular, API-enabled data, content, transactional services and business rules for re-use across government and third-party service providers.

6. Accessibility: support social inclusion for people with disabilities as well as others, such as older people, people in rural areas and people in developing countries.

7. Consistent and responsive design: build the service with responsive design methods using common design patterns within a style guide.

8. Participatory processes: design platforms and methodologies that take into account civic participation in researching, updating and developing services.

9. Performance measurement: measure performance such as digital take-up, user satisfaction, digital service completion rates and cost per transaction for better decision-making.

10. Encourage use: promote the use of digital services across a range of channels, including emerging opportunities such as social media.

Source: Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on the Design and Delivery of Services, E‑Leaders Lisbon Meeting, 2017.

Standards and guidance

Around the world, countries are exploring ways to establish the criteria for assessing the delivery of services and judging their quality. This has resulted in at least 21 service standards being produced for different tiers and jurisdictions of government around the world alongside guidance and resources to support digital government teams in their approach to delivery and understanding of performance (Pope, n.d.[13]). The summary proposed by the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on the Design and Delivery of Services is discussed in Box 4.3. Panama does not have a comparable design assurance process for government teams or external suppliers although six organisations identified there being written guidelines on how to involve the public in informing and shaping the design of services. Nor has Panama developed an easily accessed set of reference materials for supporting the dissemination of knowledge throughout the sector (the example of the United Kingdom’s Service Toolkit is discussed in Box 4.2).

Instead, Panama has developed a repeatable model for identifying the interaction patterns of a given service and providing the necessary technical components that allow teams to create a digital representation of the approach. This has allowed Panama to move quickly in the digitisation of services. Whilst success may currently be measured by the number of processes accessible online, the next phase of Panama’s digital government efforts to reengineer end-to-end services, which are data-driven and proactively meet the needs of citizens, may require a different approach. The adoption of a service standard and the production of guidance to resource, empower and encourage teams across the government may prove beneficial.

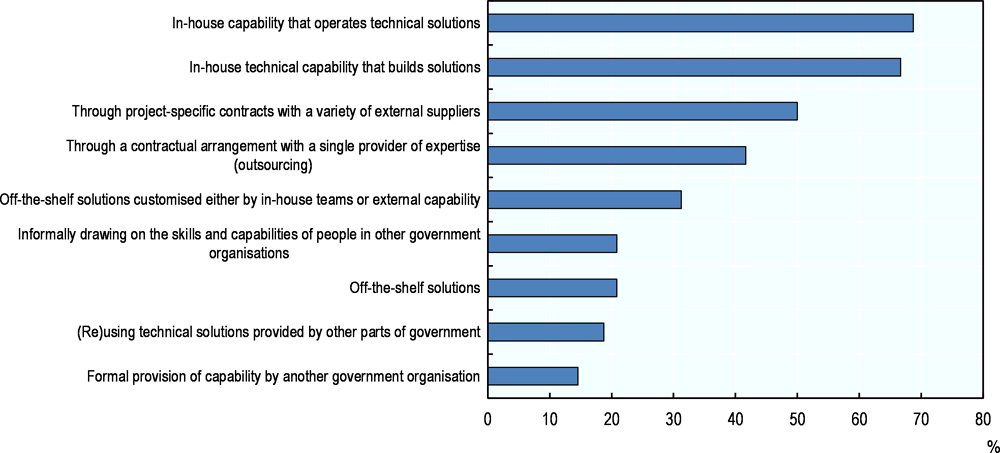

This support should be targeted at both those working within government and its supplier ecosystem. Figure 4.9 shows that 69% (33 out of 48) of institutions in Panama favour in-house capabilities but there are equally strong roles for external companies with 41% (20 out of 48) of delivery being done through wholly outsourced activities and 50% (24 out of 48) of organisations using external suppliers for project specific activities.

Figure 4.9. Approach to designing, building and maintaining online services

Note: Based on the response of 48 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[6]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 48: “How does your institution design, build and maintain online services?”

Digital identity (DI)

In personal interactions with the people we know we do not request proof of their identity. Even when we meet someone for the first time, we accept that they are who they say they are. However, in dealings with businesses and government, such questions cannot be taken on trust and an identity must be proven. As a result, individuals have ended up with physical tokens to show someone, which prove an identity. These approaches do not support successful digital government. Successful digital governments offer services that work for people wherever they are and without the need for any physical interaction to prove identity.

Technology has been applied to this problem through the creation of digital signatures and the adoption of password-based account services. These solutions tend to lack co‑ordination and result in government and citizens juggling multiple authentication credentials. Increasingly, governments are looking to develop DI strategies that resolve this complexity and provide a single, verifiable and secured identity for citizens to interact with government services and maybe even the private sector too. In a benchmarking exercise the OECD conducted to assess the DI experience of 13 countries for a forthcoming study of Chile, 7 separate identity models were identified, 2 of which are discussed in Box 4.4.

Box 4.4. DI in Italy and New Zealand

The Italian Public Digital Identity System (il Sistema Pubblico di Identità Digitale, SPID)

SPID enables Italian citizens to access online government services through a single DI (username and password). It allows public administrations to replace their locally managed authentication services with a resulting cost saving in ongoing running costs and the work involved with credentials. Moreover, compared to these legacy approaches, SPID increases the level of assurance that the person accessing the service is who they claim to be.

The basic level of authentication offered by SPID uses a single factor model with a pair of username and password credentials. The password is user-generated in accordance with a stated password policy and must be changed at least every three months. Resets to the password are only possible after successfully answering security questions. In addition to this basic authentication, more advanced levels of authentication offer greater security.

Italy has decided that SPID will be mandated in future and that all government services will retire any legacy authentication models. To do this they have developed a simple process by which it can be added to a government service, documented at https://developers.italia.it/en/spid.

SPID is confirmed as the Italian approach for providing eIDAS-compatible services (see Box 4.7) within the EU.

New Zealand’s RealMe Scheme

The RealMe scheme allows citizens to access multiple government services with the same username and password. Users wanting to access a service are handed to the RealMe platform as part of their journey and, after authentication, handed back to the service. RealMe stores no information but simply validates that a user can access a service: the individual retains control over what information they share and when they share it.

The RealMe service was developed in partnership by the Department of Internal Affairs and the New Zealand Post. It responds to the needs of government whilst also providing the basis for DI in the private sector. Users can use it for a range of services including opening a bank account, enrolling to vote, transferring foreign currency, applying for a loan or allowance, and renewing their passport online.

Source: Provided by Italy and New Zealand in response to the OECD survey Benchmarking Digital Identity Solutions (Unpublished).

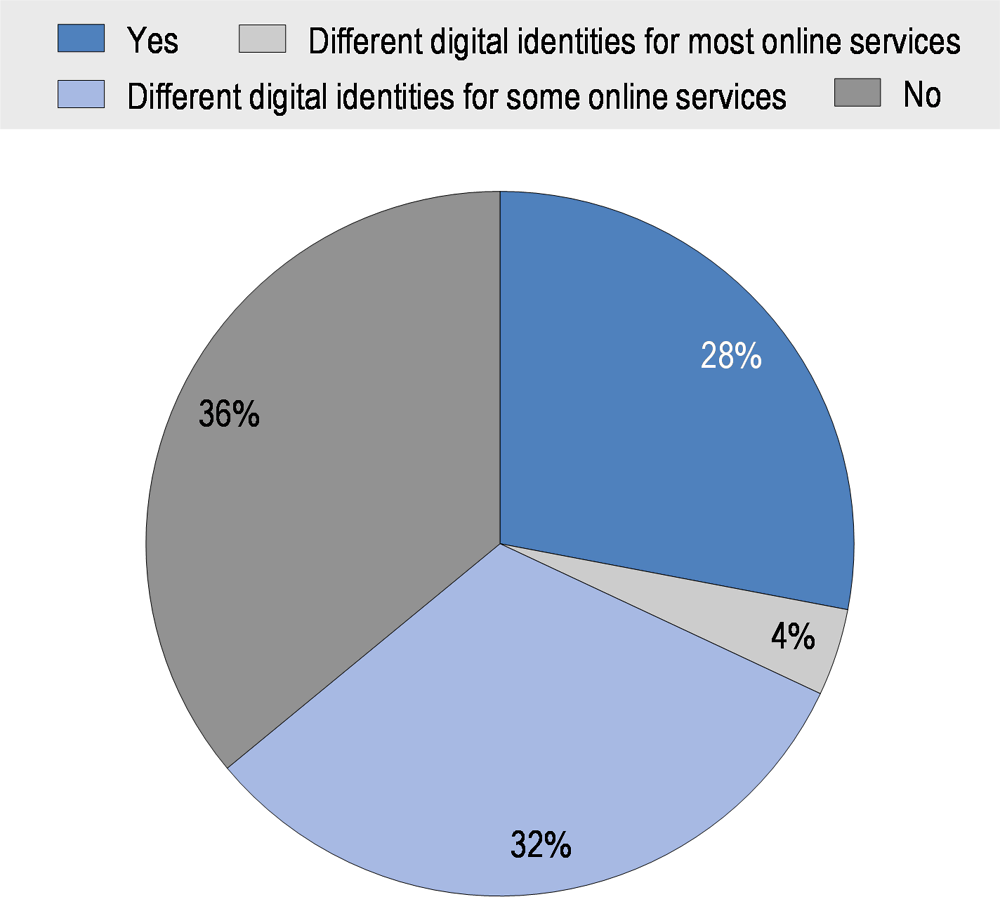

In Panama, the foundations for DI were recognised in Executive Decree No. 719 of 15 November 2013, which made provision for services using the electronic signature to be treated as though they had been conducted on a face-to-face basis. In the Agenda Digital 2014-19 PANAMÁ 4.0 (Autoridad Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2016[5]), the ambition for DI was presented with the expectation that all users would be authenticated via a mechanism administered by the Electoral Court of Panama (Tribunal Electoral de Panamá) built on top of the country’s public registry and its physical identity infrastructure. The intention was that any government applications delivered under the umbrella of PEL would do so with the backing of this DI model, eliminating the need for interaction in person and simplifying outstanding legal barriers to the transformation of services. Despite the existence of the necessary legal frameworks to implement DI and recognise electronic signatures, the efforts to implement this enabler of digital government have stalled, with a pilot test of a DI (Cédula Inteligente) only recently initiated. Figure 4.10 highlights the fragmentation of the situation. Of the 14 institutions that were aware of the proposed single identity service, only 6 were using it, whilst 3 were in the process of developing their own solution. A further 18 acknowledged that citizens could create and manage different Dis in order to access the services they require.

Figure 4.10. Institutional approaches to DI in Panama

Note: Based on the response of 50 institutions.

Source: Based on information provided in response to OECD (2019[6]), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Question 52: “Is there a single digital identity system being used by the central/federal government in your country?”

Whilst a technical solution is necessary, it is only one part of the response required to realise the transformative impact of DI. A further issue is the governance for DI. Responsibility has fallen to the Electoral Court of Panama (Tribunal Electoral de Panamá) because they are the organisation that holds the analogue records and has responsibility for analogue identity mechanisms. However, with DI so integral to the transformation of the state, AIG needs to assume increased responsibility for the strategic outcomes associated with its design, delivery and implementation rather than acting primarily on a consultative and co‑ordinating basis.

A second area for concern is Panama’s tendency to focus on technology. Rather than implementing technology that addresses the identity step in a formerly analogue process, DI mechanisms built with data-driven interoperability in mind can have a transformative impact on avoiding particular steps, reusing existing data sources and rethinking the way in which a citizen or business might interact with the state. DI should be a springboard for Panama to redesign the state in a way that recognises the context of their citizens, not simply to implement technology and digitise interactions.

Data and interoperability

Panama has done important work in terms of the foundations for interoperability. Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012 (Asamblea Nacional, 2012[4]), requires all government databases to be interoperable; Resolution No. 12 of November 16 2015 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2015[14]) created the National Interoperability and Security Committee with a standing representative from AIG; and Resolution No. 15 of 3 May 2016 (Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental, 2016[15]) set out the interoperability framework for Panama and the steps expected for how institutions would achieve its implementation.

The RNMS is a data exchange network that connects government institutions across the country with secure telephony and connections into the NCG. It forms the basis for the technical response to the challenge of interoperability through which institutions can publish and access data for delivering cross-government services.

Work on the various platforms is a clear indicator of a commitment to developing mechanisms that make interoperability possible across the Panamanian public sector but this is still nascent. Indeed, although Panama has the once-only-principle enshrined in Law No. 83 of 9 November 2012 (Asamblea Nacional, 2012[4]), the OECD peer review team was informed on multiple occasions of services where citizens or businesses would need to provide information already held by one part of government to another in order to address their issue. Greater support, whether through legislation, increased mandate or political will towards the ongoing efforts of AIG and the enforcement of the existing law, is needed for interoperability to be assured between platforms and government organisations. An increase in the integration of data and systems will enable Panama to consider the design of end-to-end services that respond proactively to the needs of citizens as well as providing a focus for surfacing and addressing the challenges of legacy technologies.

Nevertheless, as Panama looks to develop a more coherently joined-up approach to government in general, it is important to recognise that interoperability is not solely a technical challenge. In the case of SPA and Justice (discussed earlier) and the Platform for the Integration of the Logistic and Trade Systems in Panama (Plataforma Tecnológica para la Integración de los Sistemas de Logística y Comercio Exterior de Panamá, PORTCEL), the delivery of cross-cutting platforms that enable the delivery of transformed services for these sectors was made possible by getting people to work together. The capacity for collaborating in order to deliver is every bit as important as the capacity to exchange data. This does not diminish the value of addressing the full data governance issues discussed in Chapter 3 but recognises that a focus on people may prove fruitful.

Emerging and disruptive technologies and innovation

Disruptive technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and distributed ledger technology (DLT), are increasingly the focus of debate when it comes to the future of service delivery in both the public and private sectors. The opportunities offered by these technologies to governments for enabling a more effective policymaking process, enhancing the trust and integrity of record keeping and delivering services that are personalised and proactive, are seductive. Maximising their public value presents challenges in understanding where their use is worthwhile whilst at the same time maintaining the regulatory care and attention that is required. The National Secretariat of Science, Technology and Innovation (Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, SENACYT) is an active partner with AIG in exploring the role of innovation in society more broadly and there is a great opportunity for the two to work more closely together in the future.

The existing regulatory and legal frameworks in which countries operate can sometimes be constraining in terms of allowing governments and businesses to respond to the changing priorities of society and for innovators to embrace the opportunities of emerging, disruptive technologies. This is because they can be specifically tailored towards the particular industries, technologies, processes or analogue systems available when they were introduced. In light of the new challenges, which the digital transformation introduces to regulating industry and government, it is important to find ways to augment and evolve existing practices rather than introducing new, onerous, overheads on either those being regulated or carrying out the regulatory activities. As such, enforcement and compliance methodologies should increasingly put users at the centre, be they individuals or organisations (OECD, 2018[16]). One way of supporting these efforts is to build partnerships between academics, the private sector and innovation labs to explore the implication of emerging and disruptive technology and facilitate spaces for working closely together with implementing organisations that will test thinking in practice, not in theory. In Panama, the regulatory body is attempting to shift the focus away from technologies and towards the regulation of services. This focus on the outcome, rather than the technology, can set an important precedent for the way in which Panama responds to future opportunities.

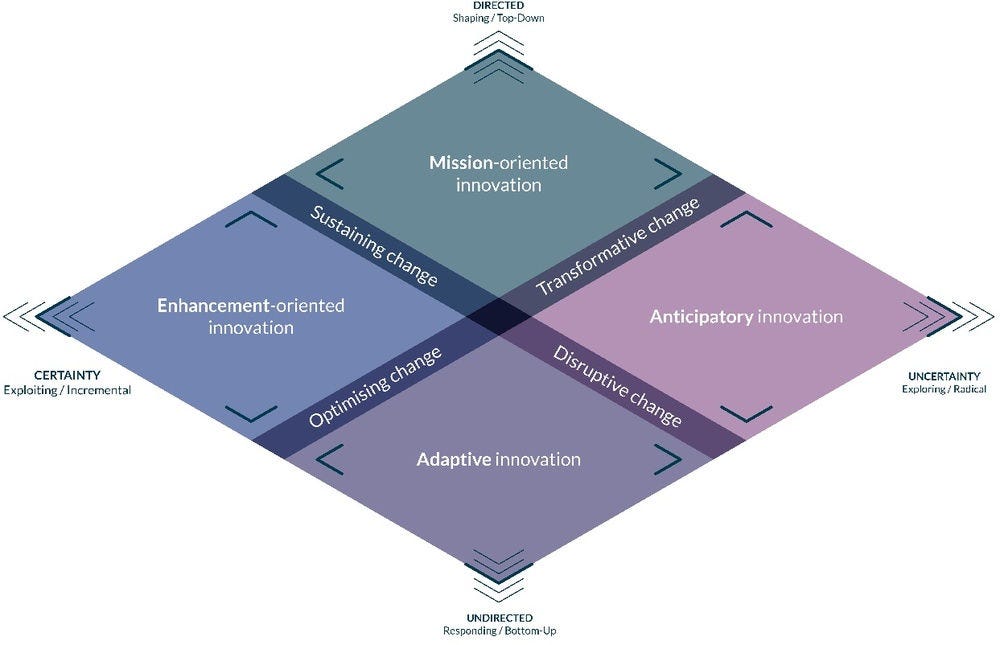

Box 4.5. Public sector innovation facets

The OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) has identified that public sector innovation has multiple facets with different change taking place at the intersections between them. The model below identifies these facets as:

1. Enhancement-oriented – starting with the question of “How might we do X better?”, it is not about questioning what is being done but rather how it is done and whether it can be done differently and hopefully better.

2. Mission-oriented – asking “How might we achieve X?”, with X ranging from the world-changing (going to the moon) to the significant but relatively contained (ensuring better services). It starts with a driving ambition to achieve an articulated goal, though the specifics of how it might be done are still unclear or fluid.

3. Adaptive – starts with the question “How might our evolved situation change how we do X?”. Adaptive innovation is about realising that things happen that do not fit with what is expected.

4. Anticipatory – starts with the question of “How might emerging possibilities fundamentally change what X could or should be?”, with X being the relevant government response or activity. Anticipatory innovation is about recognising and engaging with significant uncertainty around not only what works but also what is appropriate or possible

Figure 4.11. Public sector innovation facets

Source: OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (https://oecd-opsi.org/projects/innovation-facets/).

As the digital government agenda in Panama matures, what was once “innovative” becomes more of a mainstream activity. For AIG, this presents a challenge in balancing the need for a focus on operational excellence and continuous improvement of government services with the horizon-scanning role of stimulating and supporting innovation. The OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation has developed a model for considering the different facets of innovation and the change that it precipitates, which could prove valuable for Panama in understanding how to evolve its approach to innovation (Box 4.5).

There were only limited references to emerging or disruptive technologies during the review. This reflects the current focus of the Panamanian public sector on delivering the fundamentals of digital transformation rather than being distracted by the promise and hype of the future. Nevertheless, there are some important sectors in Panama’s economy where exploring the role of emerging and disruptive technologies may prove fruitful such as those associated with the Panama Canal. Following existing work to digitally transform trade through the development of PORTCEL, the sea, land and air logistics cluster is exploring emerging and disruptive technologies in conjunction with their international partners. The importance of Panama to global trade provides an important opportunity for Panama to develop expertise, stimulate innovation and incubate new businesses.

The plan to build AIG’s Centre of Excellence for Digital Government and Innovation at the Ciudad del Saber (City of Knowledge) and next door to SENACYT will locate AIG closer to the academic and private sectors based there with facilities that support AIG’s mandate and allow a greater contribution to developing the digital transformation and innovation ecosystem in Panama. Working with them to build public-private partnerships could provide the necessary funding and expertise to explore applications of emerging and disruptive technologies that may otherwise be impossible. Panama has shown a strong commitment to supporting innovation within the private sector, but it may now be valuable to pursue the encouragement of partnerships supporting innovation in the delivery of public services in the country by working with multilateral funding organisations to support these efforts. In the United Kingdom, the GovTech Catalyst has provided GBP 20 million to support a competition where public sector organisations can find innovative solutions to operational service and policy delivery challenges, whilst in Portugal a EUR 10 million funding program for data science and the use of artificial intelligence in the public administration has funded:

1. Pattern analysis on prescriptions (enabled by other efforts to ensure 90% of these interactions are already electronic) to identify situations where excessive prescription of antibiotics may represent a health risk.

2. Analysis of the skills present in the unemployed labour force compared to the needs of the job market to identify those who are most at risk of becoming long-term unemployed and in need of targeted training.

3. Development of models to allow better targeting of inspections by public bodies of food safety and business activity.

Box 4.6. Panama Digital Hub

The Panama Digital Hub is an alliance between public, private and academic sectors to establish Panama as a centre for digital innovation. The Panamanian Chamber of Information Technology, Innovation and Technology (Cámara Panameña de Tecnologías de Información, Innovación, y Telecomunicaciones, CAPATEC) and SENACYT have taken the lead in developing the strategy.

The strategy focuses on three things:

Building international calibre innovation that launches new products and services for an international audience through acquiring skills in research and development.

Building export capacity for those products and services

Identifying ways to ensure that these activities are sustainable and embedded in Panama so that they outlast the period of the strategy.

The Digital Hub has four pillars designed to strategically strengthen the opportunities for economic development through digital innovation and entrepreneurship:

1. Human talent.

2. Physical and social infrastructure.

3. Financial resources.

4. Legal and regulatory framework.

In July 2018, Executive Decree No. 455 of July 2018 set out five priorities for the next phase of the Digital Hub programme:

1. Establishing a National Institute of Advanced Scientific Research in Information and Communication Technologies (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas Avanzadas en Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación, INDICATIC).

2. Creating the International Center for Technological Development and Free Software (Centro Internacional de Desarrollo Tecnológico y Software Libre, CIDETYS).

3. Developing a timetable and action plan for establishing a Regional Data Exchange Center.

4. Facilitating and encouraging Fintech companies to innovate and base themselves in Panama through the development of a regulatory sandbox.

5. Updating the tax platform and the associated rules affecting the digital economy and e‑commerce.

Source: Panamá Hub Digital (https://www.panamahub.digital)

The geography of Panama places it at the confluence of global trade and at the heart of international conversations as well as with an important interest in climate change. Several of the world’s leading technology companies recruit remote workers in Panama and the ambition to become a logistical hub for the region’s humanitarian aid sector reflects the opportunities for international organisations to base themselves in the country. Multiple areas within Panama’s economy and society offer interesting opportunities to stimulate start-ups and model transformed delivery of service whether in trade, ecology, tourism or other services based on its already established base of multinationals and its privileged connectivity. As the country develops its “digital hub” strategy (Box 4.6), expands its own data protection frameworks (see Chapter 3: Data protection) and builds advanced data and interconnectivity infrastructure (see Chapter 4: Digital inclusion), the digital economy in Panama will benefit and provide increasing opportunities for the country to increase its global reach and explore new markets. Aside from the delivery of services that cross borders (see Chapter 4: Cross-border services), Panama should expand its efforts to attract inward investment in the areas of digital, data and technology to create a conducive environment for innovation.

Cross-border services

Citizens, businesses and governments increasingly consume content, access services and transact without regard to national borders or geographic context. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[17]) identifies the potential of international co‑operation for knowledge sharing, strategic co‑ordination and collaboration across borders to use digital, data and technology to deliver better outcomes for their citizens.

The geography and geopolitics of Panama and the importance to its economy of trade, and in particular the role of the Panama Canal, means that this is not a new discussion in terms of developing the country’s expertise. The logistics sector was defined as a priority by the Government in order to speed up the movement of goods through the border, minimise delays and generally introduce the benefits of digital transformation. PORTCEL is an important intervention to reduce the use of paper, ensure that data is easily shared and reduce the time it takes to cross the border (Gobierno de Panama, 2014[1]). By following open standards and working in partnership with regional and international partners, it facilitates the seamless movement of goods, vehicles and workers between jurisdictions. The survey highlighted other examples of cross-border data exchange and service delivery in Panama:

1. the work of the National Customs Authority (Autoridad Nacional de Aduanas, ANA) in terms of customs declarations and information about drivers and vehicles

2. the National System of Civil Protection (Sistema Nacional de Protección Civil, SINAPROC) works with neighbouring Costa Rica

3. and the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Ministerio de Comercio e Industria, MICI) in its interactions with the World Intellectual Property Organization.

However, there are many areas where the country is not yet thinking about the experience of services that are shaped by having to cross a border. This gap was particularly noticeable in discussions about the immigration service. Whilst this would not be seen as a priority for Panamanian citizens, the process by which someone receives permission to work impacts on several hundred people a day and generates significant internal effort. The 12-step process takes 1 to 2 months to complete and can only be initiated, in person, once they are physically in the country.

Cross-border services should respond to the needs of citizens and businesses in terms of the design and priority of issues to address. In order to enable such development to take place, there needs to be a recognition of the following critical activities (OECD, 2018[18]):

1. Alignment of legal frameworks.

2. Adoption of common data and architecture standards.

3. Interoperability of DI.

4. Mutual recognition of digital certificates.

As has been discussed elsewhere in this review, these are areas that Panama must address to fully realise the potential opportunities at a domestic level. However, such efforts would benefit from being approached with an awareness of the need for developing regional and international partnerships such as that modelled between Finland and Estonia (OECD, 2015[19]). As such, this is not something that can be implemented in the short term. Developing cross-border services requires political will as well as investment in terms of budget and capabilities.

Box 4.7. Cross-border recognition of credentials

Argentina’s driving licence

In Argentina, the Mi Argentina mobile application allows citizens to access a digital version of their driver’s licence. It has the same legal power as the physical equivalent and is automatically generated if the citizen is already in possession of a valid driver’s licence. The National Digital Driver’s Licence is built on top of the Argentinian Digital Identity System (Sistema de. Identidad Digital, SID) which provides remote validation of citizens’ identity using biometric data.

Because so many Argentinians regularly travel across the border to neighbouring Chile and Uruguay, efforts have been made with their respective governments for this digital licence to have the same validity in those countries. This approach has benefitted from the Digital Agenda Group of the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) working together to identify and prioritise public services that could be delivered across borders.

Source: Lanzan la versión digital del registro de conducir que se podrá "llevar" en el celular (Jueguen, 2019[45]), Argentina just made driving licences digital (Public Digital, 2019[46])

European Regulation 910/2014 (eIDAS)

In the EU, cross-border recognition and legitimisation of identity mechanisms are backed not by the re-use of a particular set of credentials, as in the case of Argentina, but by a focus on developing an agreed standards approach to those technical solutions.

The eIDAS regulation provides an important legal basis to the delivery of cross-border services and the easy movement of citizens from one jurisdiction to another within the single market. Established in EU Regulation No. 910/2014 of 23 July 2014, it has been providing the legal underpinnings to the conditions under which member states have developed and enhanced DI solutions that could be recognised by other countries and reused by their citizens to access services throughout the single market.

From 29 September 2018, any organisation delivering public services in an EU member state must recognise electronic identification from all EU member states. The development of DI approaches on the basis of standards makes it possible for services to be accessed across a region without people needing to create them every time.

Source: eIDAS – The Ecosystem (European Union, n.d.[47])

The experience of the EU in developing the European Digital Single Market provides a possible template for Latin America and Caribbean countries to emulate despite the significant differences between their respective political and economic alignments. The EU’s desire to simplify the way in which businesses and customers transact across borders is underpinned by efforts to address any regulatory barriers to moving from individual national markets to a single, EU-wide rulebook. The EU estimates benefits of EUR 415 billion per year in economic growth, job creation, competition, investment and innovation in the EU. Several of the opportunities here exist for the private sector with associated efforts from governments to make it easy to open businesses or comply with tax regimes but the agenda also commits to strengthening joint efforts on cybersecurity, making DI portable and guarding citizen data rights (European Commission, 2015[20]).

The countries of Latin America and the Caribbean have been working together to strengthen their co‑operation and knowledge sharing on digital government through the e-Government Network of Latin America and the Caribbean (Red de Gobierno Electrónico de América Latina y el Caribe, Red GEALC). Panama is clearly a leader in the regional discussion on digital transformation with their presidency and hosting of the V Ministerial Meeting of the Red GEALC in 2018, a demonstrable success. This role affords the country an opportunity to help define and shape a cross-border strategy for the Central American region. Efforts to develop cross-border services in the region will further benefit from the support of the IDB and Panama’s role within the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

These efforts to achieve closer relationships between countries in the region lead naturally into the development of cross-border services to simplify the movement between countries for work, study, business or leisure. Whilst this might be accepted in principle, putting it into practice may prove harder given the differing levels of digital development and domestic politics in the relevant countries. Therefore, adopting a standards-based approach to these activities would be advisable. Not only would it allow those countries that can identify and deliver value quickly to explore how such an approach might become more widely adopted (as seen by Argentina’s work on their digital driving licence in Box 4.7), but it would mean that these benefits were not limited to the Central American region. As seen in the trade agreement signed between the EU and Japan, having a clear and effective approach to data protection has allowed for a mutual recognition of equivalency between those regimes and the opening up of particular industries to trade that might otherwise have been limited (European Union/Government of Japan, 2018[21]).

References

[4] Asamblea Nacional (2012), Ley 83 de 9 de Noviembre de 2012 - Regula el uso de medios electrónicos para los tramites gubernamentales, http://www.innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Ley_83_del_9_de_noviembre_2012.pdf.

[7] Asamblea Nacional (2008), Ley 59 de 11 de agosto de 2008 que promueve el servicio y acceso universal a las tecnologias de la informacion y de las telecomunicaciones para el desarrollo y dicta otras disposiciones.

[5] Autoridad Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental (2016), Agenda Digital 2014-2019 Panamá 4.0, http://innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Agenda_Digital_Estrategica_2014-2019.pdf.

[10] Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (2015), Programa de mejora de la competitividad y los servicios públicos a través del gobierno electrónico, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=40057894.

[15] Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental (2016), Resolución No. 15 del 3 de mayo de 2016, http://innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Resolucion15_2016ApruebaEsquemadeInteroperabilidadCNIG.PDF.

[14] Consejo Nacional para la Innovación Gubernamental (2015), Resolución No 12 del 16 de noviembre de 2015, http://innovacion.gob.pa/descargas/Resolucion12RevocaResolucion22_2015.pdf.

[20] European Commission (2015), A Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe (COM(2015) 192 final), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0192.

[11] European Union (2016), Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 October 2016 on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016L2102.

[21] European Union/Government of Japan (2018), Council Decision (EU) 2018/1907 of 20 December 2018 on the conclusion of the Agreement between the European Union and Japan for an Economic Partnership, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32018D1907.

[1] Gobierno de Panama (2014), Plan Estrategico de Gobierno Panama, Gobierno de Panama, Panama City.

[9] Gubernamental/IDB, Autoridad Nacional para la Innovación (2013), Plan Estratégico de Banda Ancha de la República de Panamá.

[8] International Telecommunication Union (2018), Panama Profile (2018), International Telecommunication Union, https://www.itu.int/net4/itu-d/icteye/CountryProfileReport.aspx?countryID=189.

[6] OECD (2019), Digital Government Survey of Panama, Public Sector Organisations Version, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[16] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[18] OECD (2018), Promoting the Digital Transformation of the African Portuguese Speaking Countries and Timor-Leste, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307131-en.

[19] OECD (2015), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Estonia and Finland: Fostering Strategic Capacity across Governments and Digital Services across Borders, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264229334-en.

[17] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD/LEGAL/0406, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406.

[13] Pope, R. (n.d.), Platform Land - Mapping, https://www.platformland.org/mapping (accessed on 20 March 2019).

[3] The World Bank (2019), Doing Business 2019, The World Bank, http://www.doingbusiness.org.

[12] Welby, B. (2019), “The impact of Digital Government on citizen well-being”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 32, OECD, Paris.

[2] World Economic Forum (2018), The Global Competitiveness Report 2018, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-competitveness-report-2018.