This chapter discusses the overall relevance of moving from a focus on e‑government and public sector productivity to one where data use, digital government and public value can help address decreasing levels of public trust in Sweden. It underlines how a strategic focus on data, openness and public engagement will enable the Swedish public sector to use platforms for public value co-creation, experimentation, and data‑driven business and social innovation. It also presents a brief overview of the current state of shared components in Sweden.

Digital Government Review of Sweden

Chapter 1. Public trust as a driver for digital government efforts in Sweden

Abstract

Introduction

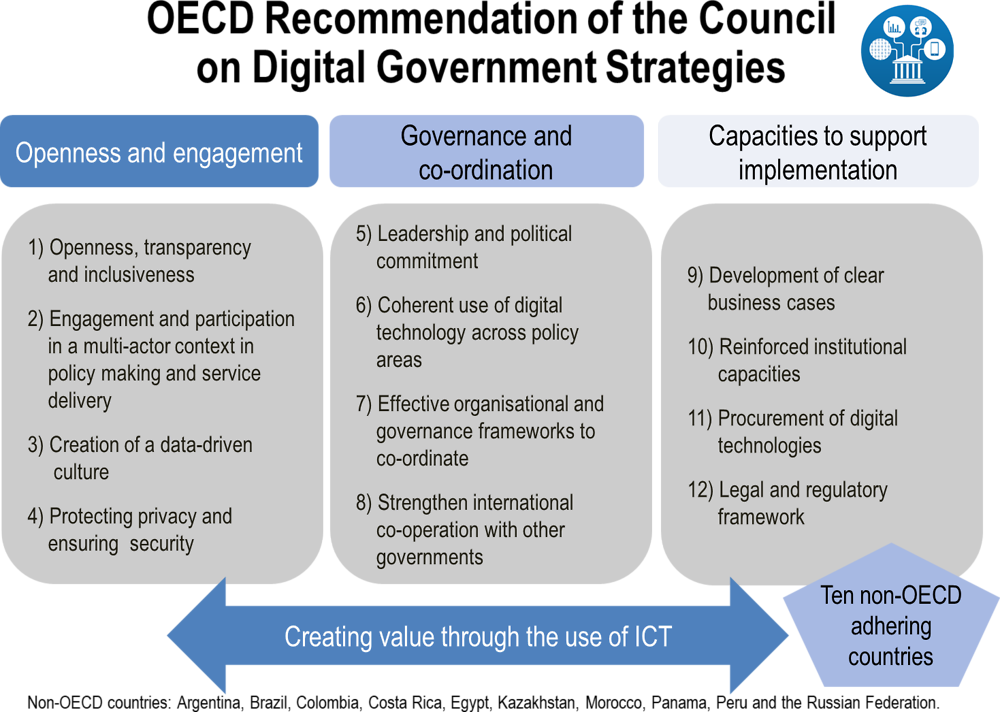

Public trust is at the core of the digital transformation of the public sector, both as a driver and an effect of such a transformation. The 2014 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies “emphasises the crucial contribution of technology as a strategic driver to create open, innovative, participatory and trustworthy public sectors, to improve social inclusiveness and government accountability, and to bring together government and non-government actors to contribute to national development and long‑term sustainable growth” (OECD, 2014) (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, 2014

The purpose of the Recommendation is to help governments adopt more strategic approaches for a use of technology and data that spurs more open, participatory and innovative governments. Key actors responsible for public sector modernisation at all levels of government (from co-ordinating units and line ministries to public sector organisations) will find the Recommendation relevant to establish more effective co‑ordination mechanisms, stronger capacities and framework conditions to improve the effectiveness of digital technologies for delivering public value and strengthening citizens’ trust. While the level of trust in government largely depends on a country’s history and culture, the Recommendation can help governments to use technology to become more agile and resilient and to foster forward-looking public institutions.

This can increase public trust through better performing and responsive services and policies, and can mobilise public support for ambitious and innovative government policies. In this regard, the principles set out in the Recommendation support a shift in culture within the public sector from a use of technology to support more efficient public sector operations to integrating digital technologies in strategic decision making and placing them at the core of overarching strategies and agendas for public sector reform and modernisation. The Recommendation hence offers guidance for a shared understanding and a common mindset on how to prepare for, and get the most out of, technological change and digital opportunities in a long‑term perspective to create public value and mitigate risks related to the quality of public service delivery, public sector efficiency, social inclusion and participation, public trust, and multi-level and multi-actor governance.

Figure 1.1. The 12 principles of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies

Source: Based on OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/recommendation-on-digital-government-strategies.htm.

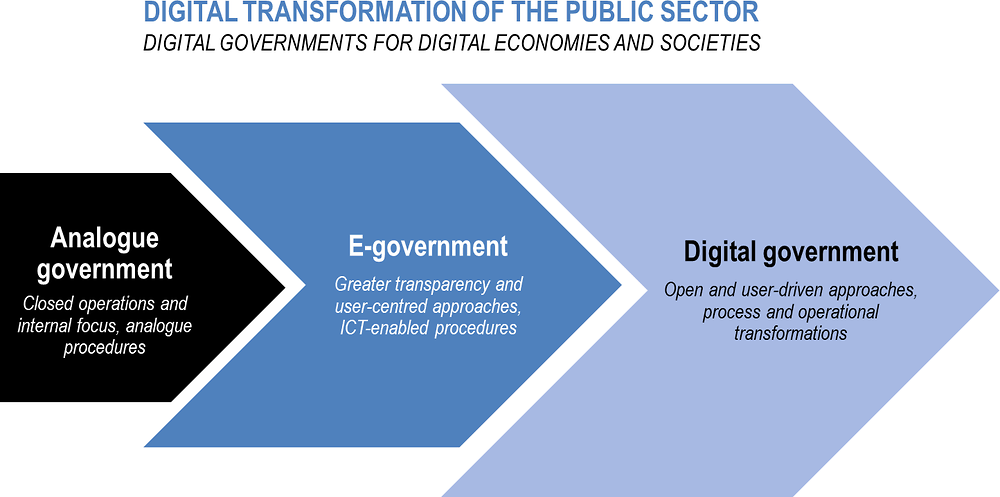

Figure 1.2. Digital transformation of the public sector

Source: Based on OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/recommendation-on-digital-government-strategies.htm.

During the peer review mission to Stockholm in March 2018, the OECD collected views from public sector stakeholders on the need of going beyond a focus on processes, productivity, internal productivity and financial stability to a broader approach where these outputs are only means to an end.

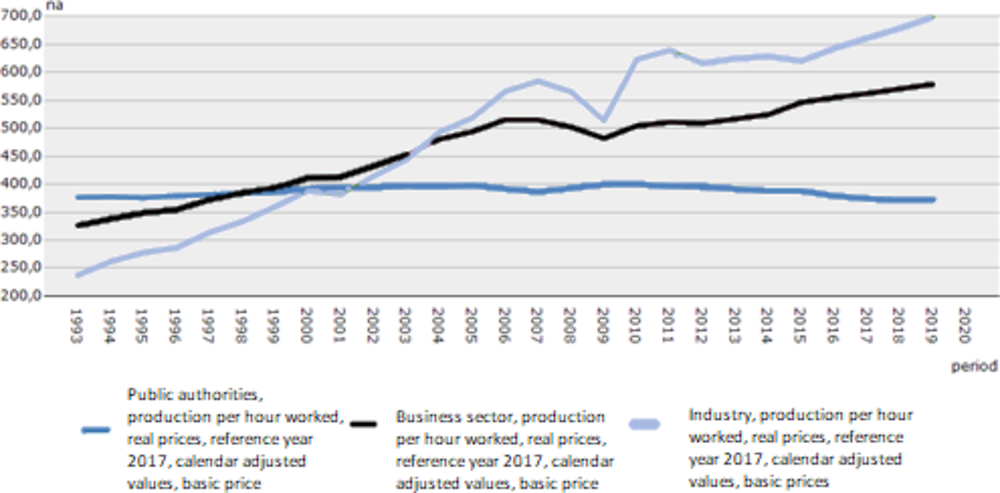

The focus on public sector productivity and efficiency in Sweden (to deliver public services and increase the efficiency of the public sector’s processes) has been the main driver behind e‑government efforts in the last decades. Such pressure for productivity drove the modernisation of public sector agencies in Sweden. Yet, the data presented in Figure 1.31 show that previous or current modernisation measures may no longer be up to the challenge. This is particularly relevant if one compares the productivity advancements in the public sector vis-à-vis those in the private sector.

Figure 1.3. Public sector productivity in Sweden

OECD work on trust has presented academic and statistical evidence on how satisfaction with public services affects the levels of public trust. There is, for instance, a “positive correlation between satisfaction with public services and trust in local governments (R2=0.75) in OECD-EU countries over the period 2008-2015” (OECD, 2017c).

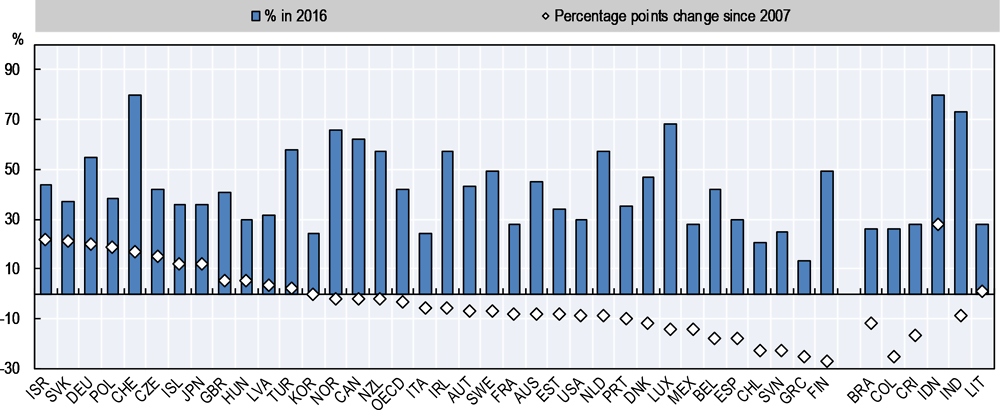

According to data from the Gallup World Poll, the levels of public trust in governments decreased by an average of 2% across OECD countries between 2007 and 2015. This trend has not changed, as data for 2016 show that levels of trust have declined by 3 percentage points since 2007 (OECD, 2017c) (Figure 1.4).

Sweden is no exception to this trend, as levels of public confidence in government decreased by 7% between 2007 and 2016.

Overall, the current levels of public sector productivity and public trust in Sweden might point to the fact that the public sector is failing not only to maintain a high level of public satisfaction with public services, but also to adapt to new challenges, stay relevant and better respond to the evolving needs of citizens.

Figure 1.4. Confidence in national government in 2016 and its change since 2007

Notes: Data on the confidence in national government for Canada, Iceland and the United States in 2016 are based on a sample of around 500 citizens. Data refer to the percentage who answered “yes” to the question: “Do you have confidence in national government?” (data arranged in descending order according to percentage point change between 2007 and 2016). Data for Austria, Finland, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Switzerland are for 2006 rather than 2007. Data for Iceland and Luxembourg are for 2008 rather than 2007. Information on data for Israel: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2017c), Government at a Glance 2017, https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en, with data from the World Gallup Poll.

The current digitalisation context and the multiplication of technological solutions raise challenges and risks for which governments must prepare. The changing societal expectations that arise from the pervasive presence of new technologies require governments to re-examine their governance approaches and strategies, the way they work, their organisational culture and capabilities to adjust and transform to better deliver public value to citizens. Failure to do so could mean an accelerated loss of trust in government and a perception that the government out of touch with societal and technological trends (OECD, 2014).

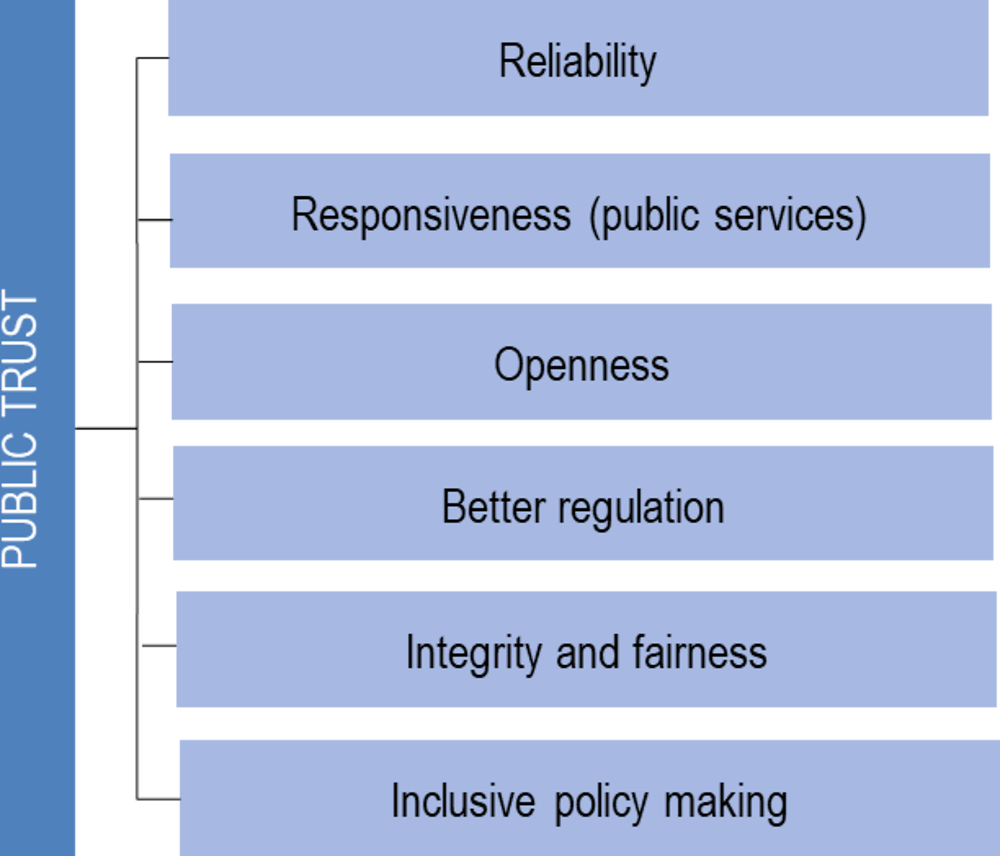

A plethora of factors – including social, economic and political variables – exert influence on levels of public trust. For instance, society’s perception of government’s capacity to deliver public services that respond to users’ needs, and its integrity and responsiveness to emerging policy challenges (see Figure 1.5), can affect the levels of public trust in government. From this perspective, for instance, distrust in government’s health services can lead to citizens’ resistance to follow health information or advice (OECD, 2017c). Hence, moving from a focus on productivity to a focus on public service delivery, government openness and public engagement can help Sweden to tackle the trust deficit.

OECD work on public trust has identified six areas that can help governments to restore, sustain and/or increase levels of public trust in government (OECD, 2017c):

1. Reliability: Governments have an obligation to minimise uncertainty in the economic, social and political environment.

2. Responsiveness: Trust in government can depend on citizens’ experiences with timely, quality, proactive and efficient public service delivery.

3. Openness: Open government and open data policies should be focused on citizen engagement and access to information.

4. Better regulation: Proper regulation is important for better justice, fairness, public services and the rule of law. This also includes the agility of governments to adapt their regulatory frameworks to meet the evolution of societies, business activities and technology.

5. Integrity and fairness: Public sector integrity is a crucial determinant of trust and is essential if governments want to be recognised as clean, fair and open.

6. Inclusive policy making: Understanding how policies are designed can strengthen institutions and promote trust between government and citizens.

Figure 1.5. Six areas for governments to win back trust

Source: based on: OECD (n.d.), “Trust in government” (webpage), www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm.

In this light, winning back trust in the Swedish public sector could provide an incentive and be a driver for future digital government efforts. Such efforts could focus on improving user- and data-driven public service, citizen engagement, government openness, and multi-stakeholder collaboration.

Nevertheless, such a change of approach implies moving away from an understanding of digital technologies as mere tools to boost public sector productivity and efficiency. It implies recognising digital technologies as levers to create a new generation of public services and form of stakeholder engagement. More responsive, proactive and inclusive public services will require a shift in mindset to design more open, iterative and innovative approaches for the design and implementation of digital government policies.

Changing the approach could help reinvigorate and create a debate about the terms of the social contract between the Swedish government and its constituents in line with the changing expectations of the digital age.

Enabling governments as platforms: A mechanism for enhanced public service delivery and greater public trust

The 12 overarching principles of the 2014 Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (see Section 1.1) are clear in terms of the relevance of openness and engagement, sound governance, and coherent policy implementation, as foundational elements of digital governments. This includes, for instance, the need to:

ensure greater transparency, openness and inclusiveness of government processes and operation (Principle 1)

encourage engagement and participation of public, private and civil society stakeholders in policy making and public service design and delivery (Principle 2)

construct data-driven public sector organisations that use data as a platform for better public service delivery and public value co-creation (Principle 3)

address digital security and privacy issues, and include the adoption of effective and appropriate security measures (Principle 4)

secure leadership, political commitment, and inter-ministerial co-ordination and collaboration (Principle 5)

ensure that legal and regulatory frameworks allow digital opportunities to be seized (Principle 12).

The 12 principles are the underlying basis of the 6 mutually reinforcing dimensions the OECD has identified as attributes of a digital government (Box 1.2). Altogether, these six dimensions aim to enhance how public services are designed and delivered to societies, spur the inclusiveness of these services in terms of digital rights, underpin trust in government, and contribute to the overall well-being of societies.

Box 1.2. The six dimensions of a digital government

1. From the digitisation of existing processes to digital by design: Government approaches “digital” with an understanding of the strategic activities involved with successful and long-lasting transformation. These activities take into account the full potential of digital technologies and data from the outset in order to rethink, re‑engineer and simplify government to deliver an efficient, sustainable and citizen-driven public sector, regardless of the channel used by the user.

2. From an information-centred government to a data-driven public sector: Government recognises data as a strategic asset and foundational enabler for the public sector to work together and uses data to forecast needs, shape delivery, understand performance and respond to change.

3. From closed processes and data to open by default: Government is committed to disclosing data in open formats, collaborating across organisational boundaries and involving those outside of government in line with the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and participation that underpin digital ways of working and the Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017b).

4. From a government-led to a user-driven administration, that is, one that is focused on users’ needs and citizens’ expectations: Government adopts an approach to delivery characterised by an “open by default” culture and ambitions of “digital by design” to provide ways for citizens and businesses to communicate their needs and for government to include, and be led by, them when developing policies and public services.

5. From government as a service provider to government as a platform for public value co-creation: Government builds supportive ecosystems that support and equip public servants to design effective policy and deliver quality services. That ecosystem enables collaboration with and between citizens, businesses, civil society and others to harness their creativity, knowledge and skills in addressing the challenges facing a country.

6. From reactive to proactive policy making and service delivery: Governments reflecting these five dimensions can anticipate, and rapidly respond to, the needs of their citizens before a request is made. They also proactively release data as open data rather than reacting to a request for access to public sector information. Transformed, proactive government allows problems to be addressed from end to end rather than the otherwise piecemeal and reactive digitisation of component parts.

These dimensions highlight how investing in efforts to enable governments as platforms can help improve how public services are designed, co-created and delivered. Enabling public servants across the entire public sector to use common tools and platforms is essential to foster coherent approaches and synergies that lead to standard quality in service delivery and economies of scale.

Similarly, providing the space and platforms to engage stakeholders is key to harnessing their creativity and levering their knowledge in the service design and delivery process. This can help close the gap between governments and their constituents, and lead to designing and delivering public services that focus on users’ needs and use data as a source of evidence in their design. Thus, services likely better fit changing demands and growing expectations and the whole process underpins government openness and responsiveness towards greater public trust.

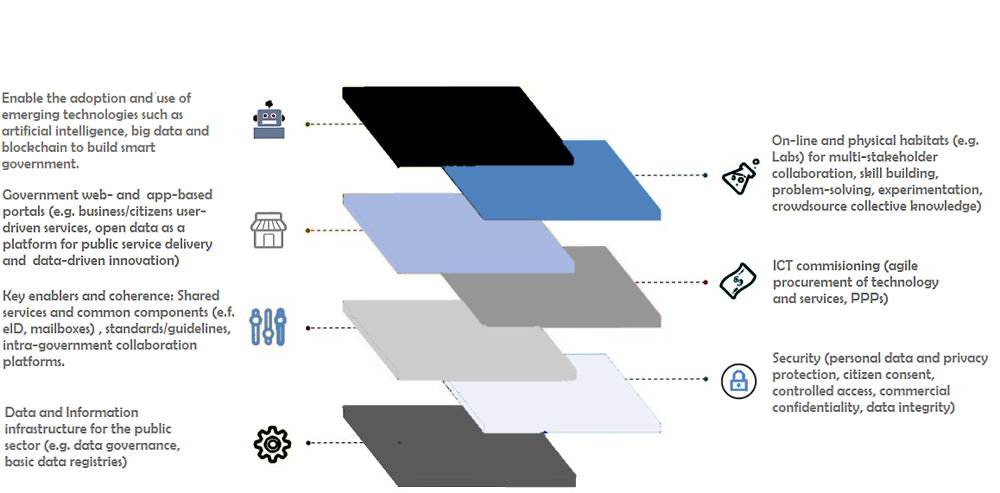

Enabling government as a platform can follow different approaches, which are composed of a series of supporting layers (Figure 1.6). These can range from technical efforts to citizen-driven and collaborative methods, for instance, to:

Construct information and data architectures and infrastructures that provide a platform for public sector intelligence. For instance, by enabling streamlined data-sharing and federation practices in the public sector. A more seamless data-sharing and simpler data integration within the public sector can help to implement core digital government principles such as once-only (i.e. the right of citizens to provide the same information and data to authorities only once).

Safeguard data privacy by putting in place strong governance frameworks to ensure that data controllers are accountable for management, handling and protection of data, and prevent data mismanagement and unauthorised access.

Define regulations and common standards, govern and stimulate the development of secured and shared services and of common components that all public sector organisations can use to improve and facilitate public service delivery (e.g. mailboxes, eID, government-citizen payment systems) of equal quality.

Procure ICT goods and services in a more agile fashion to allow external talent to solve policy challenges in a timely fashion and explore innovative ways of delivering public services.

Enable the delivery of public services through digital channels to streamline the government-citizen relationship, and using government data as a platform for social and business innovation (see Chapter 5 on open government data).

Contribute to greater stakeholder engagement (e.g. women, citizens, minorities, businesses) by enabling spaces for collaboration and experimentation supporting public sector innovation with a problem-solving mindset (e.g. policy and datalabs) in order to improve the design or the redesign of user-driven policies and services (e.g. by crowdsourcing ideas and feedback from citizens and from civil servants).

Leverage data analytics and emerging technologies such as machine learning and artificial intelligence, to build smarter governments which can anticipate citizens’ needs to inform policy and service design in advance (see Chapter 2 on data-driven public sector).

Figure 1.6. Government as a platform: The OECD digital government perspective

Sources: Author based on information from Brown, A. et al. (2017), “Appraising the impact and role of platform models and government as a platform (GaaP) in UK government public service reform: Towards a platform assessment framework (PAF)”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.03.003; Margetts, H. and A. Naumann (2017), “Government as a platform: What can Estonia show the world?”, https://www.politics.ox.ac.uk/materials/publications/16061/government-as-a-platform.pdf; O’Reilly, T. (2011), “Government as a platform”, https://doi.org/10.1162/INOV_a_00056; Ubaldi, B. (2013), “Open government data: Towards empirical analysis of open government data initiatives”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k46bj4f03s7-en; UK Government Digital Service (2018), Government as Platform blog, https://governmentasaplatform.blog.gov.uk/about-government-as-a-platform (accessed on 6 April 2018).

Digital maturity and a tradition of public sector transparency and efficiency as a starting point

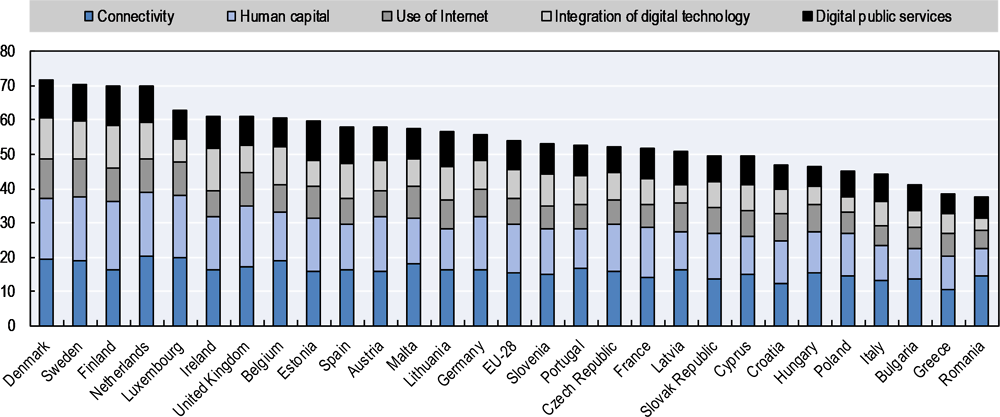

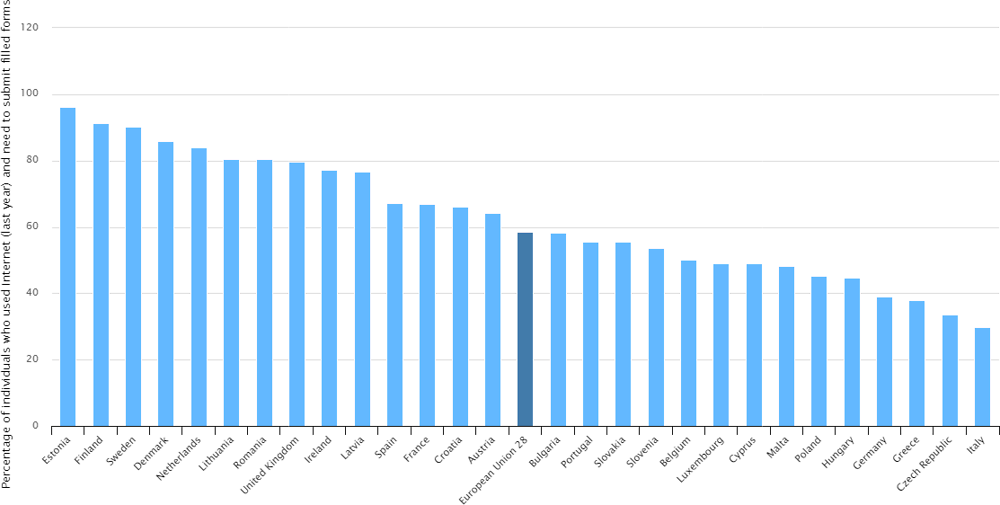

Sweden is among the most advanced OECD countries in terms of the level of digitalisation of its society and economy. This is illustrated by various international rankings, including The Digital Economy and Society Index 2018 (Figure 1.7) where Sweden ranks second regarding the use of Internet by its citizens, third in terms of the use of the Internet for transactional services (including banking and shopping), and third in terms of individuals’ “use of the Internet to send filled forms to public authorities” (see Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.7. Sweden’s overall ranking in The Digital Economy and Society Index 2018

Source: European Commission (2018), The Digital Economy and Society Index 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/desi.

Figure 1.8. Sweden in The Digital Economy and Society Index 2018: Individuals sending filled forms to public authorities, %

Source: European Commission (2018), The Digital Economy and Society Index 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/desi.

Sweden has the most digitally savvy citizens in Europe when it comes to familiarity with the Internet and the adoption of this medium in their daily lives. The sound digital skills in Sweden are also reflected in the employment market as demonstrated by a high proportion of ICT specialists as a percentage of all occupations (88%), especially relative to other OECD countries (50%) (OECD, 2017b).

The digital maturity of the Swedish society and administration are complemented by a long-standing tradition of public sector transparency dating back to the 18th century. Sweden’s Freedom of the Press Act 1766 is widely considered the oldest piece of freedom of information legislation in the world.

On 30 June 2009, the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act superseded the provisions of the 1766 Act in terms of the right of citizens to request official documents. These include, for instance, the obligation of public authorities to register official documents and appeals against decisions of authorities (Government Offices of Sweden, 2015). Sweden, as a European Union member country, is also obliged to incorporate EU directives into national laws, such as the EU directives on public sector information.

Sweden has an excellent starting point on which to build on its e-government foundations to develop a solid digital government. However, some important achievements – such as its well-established tradition of public sector transparency – risk becoming a legacy burden if the government fails to act upon them in order to transform and better respond to the needs of a digital economy and society. This would require a paradigm shift in terms of the current modus operandi – one that has been successful to realise a well-functioning e-government, but that is not sufficient enough to advance digital government efforts in the country.

A brief overview of the state of common components and shared services in Sweden

Sweden was an early adopter of e-government practices, with government agencies and some municipalities as the main drivers. The agencies for tax, social security and pensions are examples of institutions that have a large portfolio of advanced digital services. Several of these agencies collaborate around user-centric portals like Verksamt and 1177.

Many digital services use common components like eID, secure messaging and standards for data exchange. However, some policy challenges remain in terms of the current state of common components in the country. This context is paired with the lack of a strong and clear leadership (see Chapter 2), a harder approach to enforce compliance with standards and digital frameworks, stronger regulations, and insufficient central funding for digital government.

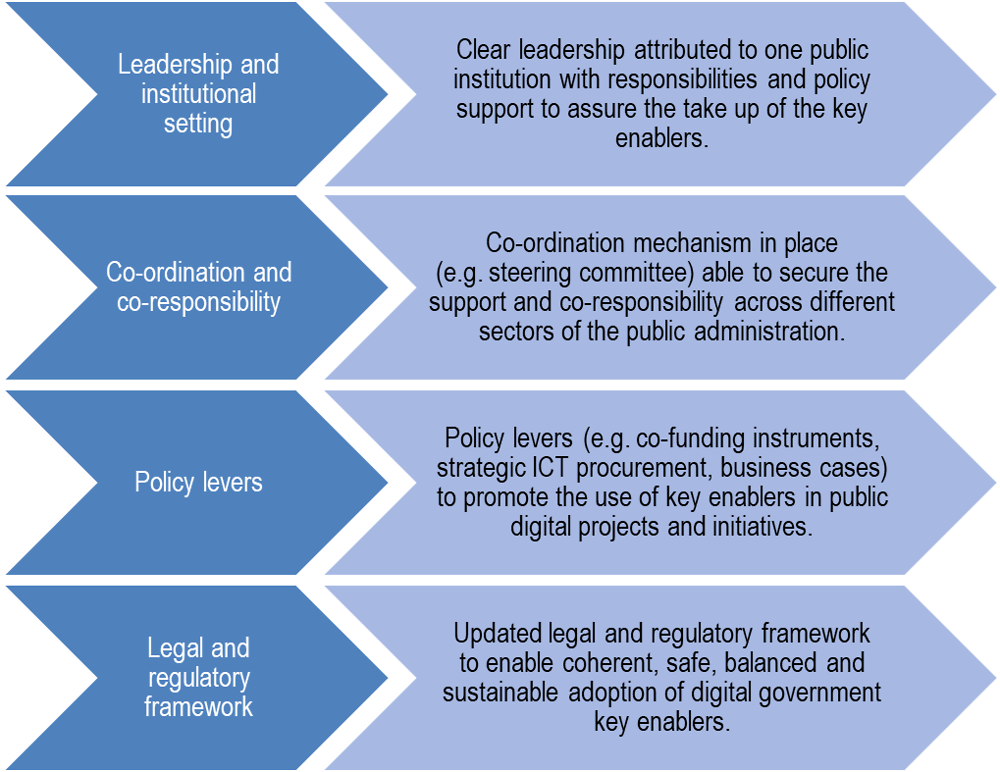

These are all crucial aspects that need to be addressed if Sweden is to strengthen the development of key enablers (Figure 1.9); the further integration of systems, data and information; and policy coherence in order to move forward in its evolution towards a fully digital and as such data-driven government (see Chapters 3 and 4).

Additionally, Sweden faces legacy challenges from a cultural, legal and organisational perspective that do not support the uptake of the key enablers (e.g. strong vertical governance structures and lack of coherent policy implementation). These challenges, which are not endemic to Sweden, can hamper the evolution towards digital government, and as such they require immediate and coherent action. This is in line with Recommendation 6 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies which stresses the relevance of ensuring “coherent use of digital technologies across policy areas and levels of government” (OECD, 2014).

Figure 1.9. Strengthening the key enablers

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Digital Government Review of Brazil, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307636-en.

Information technologies and data infrastructure

The insufficient IT soft infrastructure (e.g. regulations and standards) has led to efforts that are often unstructured and incoherent. The tangled hard IT infrastructure is the result of siloed actions, lack of adequate guidance towards the provision and adoption of common standards, and the development of fragmented IT solutions and digital services implemented by agencies.

The absence of a whole-of-government view of the public sector’s IT infrastructure impedes further integration between agencies. In order to overcome this situation, one of the key objectives of the new Agency for Digital Government (DIGG) centres on addressing issues concerning the IT infrastructure in the public sector.

Addressing issues related to the overall availability and consistency of the soft IT and data infrastructure is a priority if Sweden wants to succeed in reinforcing the state of the digital enabling frameworks (e.g. the common interoperability framework; base data registries; shared ICT/data infrastructure; business processes and services; cloud computing; open source software).

Moreover, the development of common components is normally understood from a cost-efficiency perspective, therefore losing the focus on their value as foundations for the development of shared services and a more integrated public service delivery.

The government of Sweden has commissioned2 the DIGG to co-ordinate a number of agencies to jointly submit proposals to address some of the existing challenges related to IT and data infrastructures, including:

creating a safe and efficient access to basic data by, inter alia, clarifying responsibility for and increasing the standardisation of such data by 30 April 2019

reinforcing the security and efficiency of electronic information exchanges in the public sector through increased standardisation by 15 August 2019.

Yet, in the context of the high level of self-governance granted to agencies, it will be important to focus on overcoming the existing silo-based approach by balancing actions targeting enforcement and collaboration. This would require developing a clear business case that provides convincing incentives for the development and adoption of common soft and hard components that agencies find appealing enough to prioritise government-wide solutions.

Mailbox

The case of digital government common components and shared services such as mailboxes and eID are also worth paying attention to, in particular from a digital rights perspective (digital communication channels, access to government information and data, cybersecurity and privacy protection, personal data sharing and access consent, connectivity, and transparency of artificial intelligence-based decision making tools [open algorithms]).

The Swedish government developed the Mina meddelanden mailbox infrastructure (Swedish for “My messages”) to enable digital communication between the government and its citizens. The platform is accessible through digital identification tools (see the following section on eID) and can be used to develop and provide public and private mailbox solutions to citizens.

Although public sector solutions have been developed (namely the Min myndighetspost mailbox service of the Swedish Tax Agency) citizens and businesses seem to primarily use mailbox services developed by the private sector. For instance, KIVRA, the biggest supplier of mailbox services in Sweden, provides a mailbox solution to those organisations interested in paying for their mailbox services through an app, and to those citizens and businesses choosing to use their service.

Figures provided by KIVRA to the OECD Secretariat during the peer review mission to Stockholm in November 2017 showed that at that time, 2 million Swedes were using KIVRA’s mailbox service. The vast majority of its client/profit base is integrated by private sector organisations, but some major players from the public sector (like the Swedish Tax Agency) are also part of its client base. This provided citizens with the choice of which tool to use.

KIVRA’s arrangement with the public sector provides basic services for free but premium options – like online payment functionalities – have a cost. Therefore, despite some exceptions at the municipal level, the Swedish government does not provide any financial compensation to KIVRA for its mailbox services as in most cases the free service is preferred.

KIVRA’s business case is mainly based on the provision of its services to private sector organisations, but also on the rationale that choice should be given to citizens and that public sector solutions should not compete with the private sector. Nonetheless, this also raises the question on how effective public agencies have been to develop integrated public services that could interconnect different end services provided to citizens, such as mailboxes, citizens folders or dashboards.

According to KIVRA, while mailbox services have been developed by some Swedish public sector agencies (like the Tax Angecy’s Min myndighetspost) as an alternative for people who do not want to use a private service for exchanges with the government, the number of people that prefer public solutions is roughly 100 000 vs. the 2 million KIVRA users. Indeed, if citizens are clients of KIVRA, the Swedish government opts in to use KIVRA’s platform. Otherwise, traditional postal mail service is the second-best option.

This leads to a certain level of vendor lock-in, where the sustainability of such a practice may put at risk citizens’ access to mailbox services to digitally communicate with public sector institutions should this company decide to shut down its services to those agencies not paying for its services. During the OECD mission to Stockholm in November 2017, representatives from KIVRA expressed that the legal and regulatory frameworks needed to ensure the sustainability of the service.

The case of KIVRA provides a clear example of the fact that the Swedish public sector does not seem to be sufficiently agile or fast to build end-to-end and integrated services.

eID

In Sweden, the eID policy states that eID solutions can be provided either by public or private entities (Swedish eID Board, 2018). This has led to a market-driven approach similar to the one observed for mailbox services described in the previous section, i.e. the BankID is the most used eID service in Sweden (see, for instance, Grönlund [2010]; JoinUp [2014]; Söderström [2016]).

BankID3 was developed by 11 banks to enable interoperability and integration of online and mobile services and to spur eID uptake by citizens. As a result, 7.5 million people use BankID in Sweden to access services provided by private organisations and public agencies at the central and local level (BankID, 2018).

While the success of BankID from a user uptake stance is clear, the view of public sector stakeholders differs in terms of the benefits and risks of such a model.

The success of the uptake of market-driven solutions (e.g. BankID and KIVRA) can be interpreted as a result of the limited agility of the Swedish public sector to develop its own solutions, partially caused by its consensus-based culture. Common solutions, used consistently across the public sector, are critical enablers of coherent approaches and integration which are core to a digital government that is horizontal, integrated and interconnected by nature.

Common digital solutions can be important drivers of more rapid digitalisation of public services across all sectors. Existing market solutions meet growing citizens’ expectations in terms of the quality, responsiveness and timeliness in accessing public services. However, the unwillingness of some public sector actors to implement common eID standards and frameworks caused major delays in the implementation of the Swedish public sector eID ecosystem.

Moreover, this context increases the dependence of the Swedish public sector on private solutions due to the lack of efficient and integrated public eID solutions. Stakeholders from across the government appear to be of the opinion that the development of eID solutions is not a priority for the government, leaving room for the private sector to deliver innovative solutions that meet fast-changing user needs. This scenario opens the discussion on the potential negative implication in terms of the government’s capacity to maintain control over security matters and the stability of service delivery.

A step forward in this sense, sign of the growing awareness of the government of the potential risks of the current situation, is the establishment of the e-Identification Board.4 The e-Identification Board co-ordinates and supports e-ID efforts in the public sector to further promote the coherent development of these tools and citizens’ uptake. The board is part of the Agency for Digital Government since September 2018.

References

BankID (2018), “This is BankID”, webpage, https://www.bankid.com/en/om-bankid/detta-ar-bankid.

Brown, A. et al. (2017), “Appraising the impact and role of platform models and government as a platform (GaaP) in UK government public service reform: Towards a platform assessment framework (PAF)”, Government Information Quarterly, Vol. 34/2, pp. 167-182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.03.003.

European Commission (2018), The Digital Economy and Society Index 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/desi.

Government Offices of Sweden (2015), Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act, Government Offices of Sweden, Stockholm, www.government.se/information-material/2009/09/public-access-to-information-and-secrecy-act.

Grönlund, Å. (2010), “Electronic identity management in Sweden: Governance of a market approach”, Identity in the Information Society, Vol. 3/1, pp. 195-211, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12394-010-0043-1.

JoinUp (2014), “Swedish eID”, ePractice Editorial team, 21 March, https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/document/swedish-eid-swedish-eid.

Margetts, H. and A. Naumann (2017), “Government as a platform: What can Estonia show the world?”, working paper funded by the European Social Fund, University of Oxford, https://www.politics.ox.ac.uk/materials/publications/16061/government-as-a-platform.pdf.

OECD (2018), OECD Digital Government Review of Brazil, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307636-en.

OECD (2017a), Government at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

OECD (2017b), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

OECD (2017c), Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en.

OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/Recommendation-digital-government-strategies.pdf.

OECD (n.d.), “Trust in government” (webpage), OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm.

O’Reilly, T. (2011), “Government as a platform”, Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization; Vol. 6/1, pp. 13-40, https://doi.org/10.1162/INOV_a_00056.

Söderström, F. (2016), Introducing Public Sector eIDs: The Power of Actors’ Translations and Institutional Barriers, Linkoping University, Linkoping, Sweden, http://liu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1048744/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

Swedish eID Board (2018), “The Swedish E-identification Board”, webpage, https://elegnamnden.se/inenglish.4.4498694515fe27cdbcf13d.html.

Ubaldi, B. (2013), “Open government data: Towards empirical analysis of open government data initiatives”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k46bj4f03s7-en.

UK Government Digital Service (2018), Government as Platform blog, https://governmentasaplatform.blog.gov.uk/about-government-as-a-platform (accessed on 6 April 2018).

Notes

← 1. Data from the Swedish National Institute of Economic Research.

← 2. Fi2018/02149/DF is a government mandate for some agencies to submit proposals on how to ensure secure and efficient access to basic data. Fi2018/02150/DF is a government mandate for some agencies to submit proposals on how to ensure a secure and efficient exchange of electronic information within the public sector, e.g. through standardisation.

← 3. For more information see: https://www.bankid.com/en.

← 4. For more information see: https://www.elegnamnden.se/inenglish.4.4498694515fe27cdbcf13d.html.