This chapter discusses the importance of building a vision for digital government that is widely shared, owned and recognised. It highlights the need for drawing on the consensus-based culture of the Swedish public sector as a basis to advance and put into action a digital government strategy in Sweden in a coherent fashion. This can help to ground policy objectives and build stakeholder ownership and collaboration. It first discusses the 2015‑2018 Digital First agenda. The second section discusses collaboration as means to define and advance future strategic objectives while the third and final section describes transforming government into a platform for value co-creation.

Digital Government Review of Sweden

Chapter 3. Enhancing collaboration for coherent digital government efforts in Sweden

Abstract

Introduction

The consensus-based culture of the Swedish society is one of its most prominent features. This culture favours agreement, collaboration, equality, inclusion and a temperate mindset in terms of social relationships. More importantly, it drives how decisions are taken: agreement is often sought, contrary to other societies where decision making follows a more hierarchical approach.

This culture influences the work environment and organisational ethos of the Swedish public sector. It impacts how the Swedish government and its public sector co-ordinate public policy, and the high level of autonomy and freedom that agencies have in regard to policy implementation once consensus is achieved and decisions are taken.

Yet, this social and professional tenor provides both opportunities and challenges when it is confronted with the actual need of leading and steering agility and coherency in policy making to secure the levels of speed and integration that the digital age requires.

On the one hand, this consensus-based culture provides a collaborative baseline to discuss and drive change in the Swedish public sector, engage a broader range of actors, and further transform the government into a platform for value co-creation, drawing on previous efforts and results. Nevertheless, it can also hinder efficient and agile decision making, and interfere with the need for stronger leadership to overcome organisational barriers and silo‑based decisions to boost joined-up actions.

In line with the principles of the 2014 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (see Chapter 2), this chapter highlights the need for drawing upon the culture of the Swedish public sector as a basis to advance and put into action a digital government strategy in Sweden. This can help to ground policy objectives and build stakeholder ownership and collaboration across the public sector.

The 2015-2018 Digital First agenda

In the budget bill for 2015, the Swedish government decided to fund a four-year programme that later came to be called Digital First (or Digitalt först in Swedish), with the purpose of promoting the digitalisation of the society, business activity and the public sector. As a cross-sector policy instrument, the agenda addresses digitalisation from a broader perspective ranging from digital maturity, organisational matters, legal prerequisites and digitalisation as a tool to increase the efficiency in a number of value chains.1

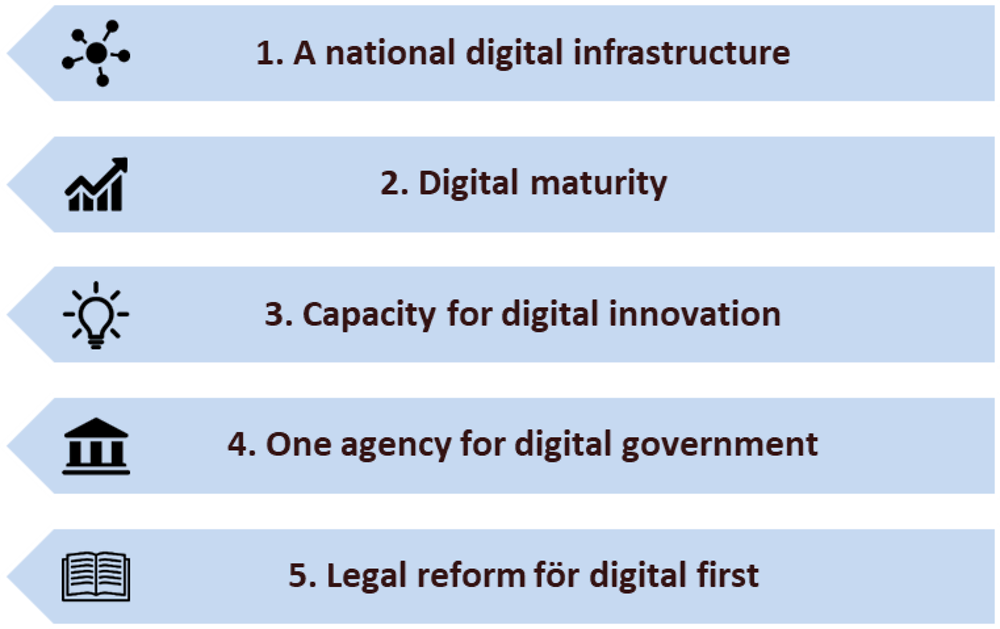

The Ministry of Finance defined five core areas of work that were specifically relevant to digital government as part of its specific responsibilities within the framework of the Digital First agenda (Figure 3.1):

1. building a solid digital infrastructure base for digital government (including data registries, eID, standards and e-procurement)

2. promoting the design of innovative digital solutions through data-driven innovation (including open data efforts), the construction of a smart government and the implementation of digital by design approaches in core policy areas (housing and building, food chain, business and environment)

3. improving the organisational culture and capacities of digital government and innovation

4. strengthening the governance of digital government (including the creation of a new digitalisation agency)

5. carrying out legal and regulatory reforms to foster the readiness and adaptability of regulatory frameworks and support the implementation of the digital agenda

Figure 3.1. Digital First agenda: Core areas of action for digital government

Source: Information provided by the Swedish Ministry of Finance.

Yet, despite the intention of the Ministry of Finance to provide a clear and comprehensive vision for digital government under the auspices of its responsibilities in the context of the broader Digital First agenda, evidence from the OECD missions and data collection exercise carried out for this Review indicate that policy goals set by the agenda relevant for digital government were perceived across the public sector more as a generic statement issued by the Ministry of Finance than a vision that is widely shared, owned and recognised. In some instances, certain public sector organisations were not even aware of its existence.

This provides an opportunity to use the potential development of a well-grounded digital government strategy as an engagement tool to build consensus around specific policy objectives, define clear roles to improve accountability and promote stakeholder collaboration in the pursue of policy impact.

Inter-institutional communication and co-ordination to define future strategic objectives

The development of the digital government agenda fell short in grounding a whole-of-government common and shared vision for digital government. Normally this is embedded in a well-structured long-term strategy, developed and implemented in co-ordination and collaboration with all relevant stakeholders from the public sector, and securing the engagement of a broader set of stakeholders from the ecosystem to crowdsource ideas and feedback.

The agenda for digital government appears to have been developed through a process that was not particularly inclusive and open, which may explain the low levels of awareness, clarity and ownership among public officials. Taking into account input from public officials is extremely beneficial to set policy goals that are shared, co-define priorities and co-create the content of the agenda. As a whole, this process would contribute to increasing policy ownership among public officials, secure accountability, and reinforce trust across the government and the public sector.

OECD work on digital government has found evidence on how communication strategies (if implemented) are, in many instances, focused on reaching the external ecosystem (e.g. through social media), but internal communication within the public sector is limited to informing public officials on what they are expected to do once goals have been defined. This can lead to a public administrator mindset that focuses on compliance.

Such a scenario hinders the possibility of increasing policy buy-in and moving towards a more collaborative environment by identifying and engaging key partners, allies and champions across the broader public sector, and building communities that can collaborate to define and achieve common objectives, co-design policy solutions, solve policy challenges, and deliver policy outcomes.

Despite the achievements in the e-government domain (e.g. mailbox and eID infrastructure, see Chapter 1), the path towards value co-creation in Sweden is somehow unclear. Sweden, as other OECD member and partner countries, often fails to acknowledge other public officials as part of the digital ecosystem and a valuable source knowledge and public sector collective intelligence.

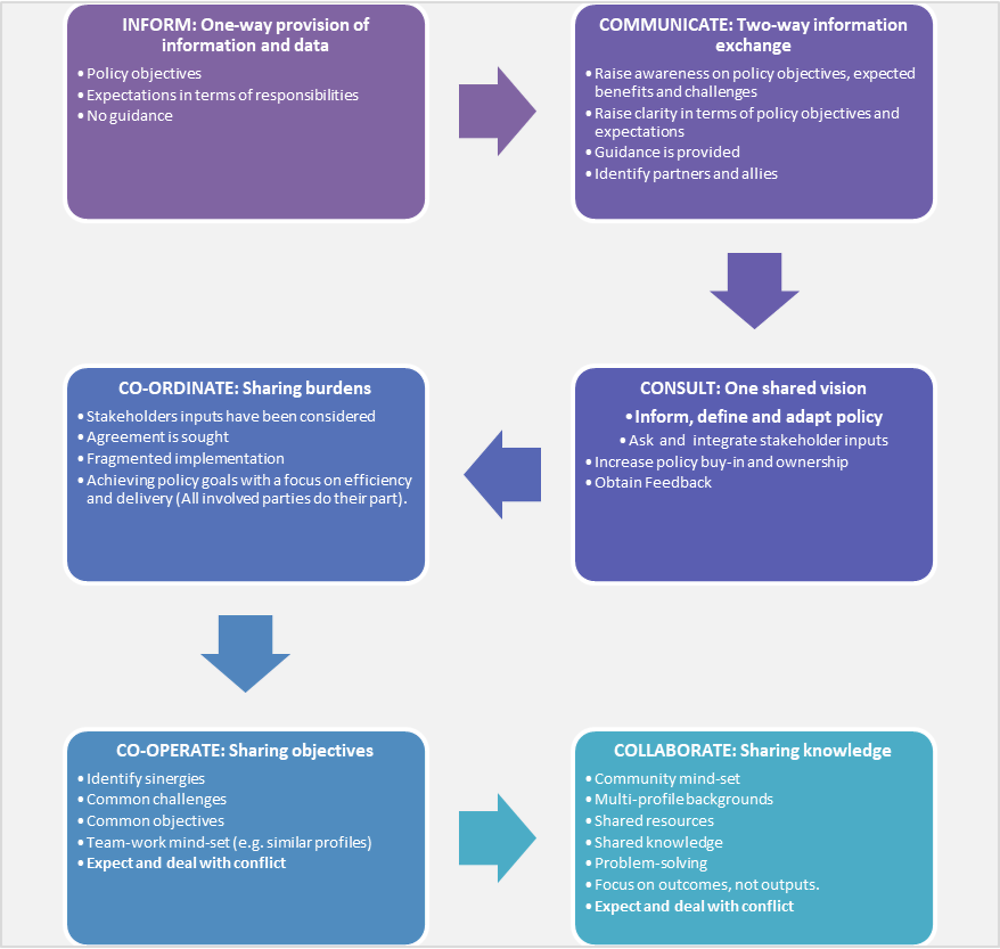

Figure 3.2. Value co-creation: A conceptual framework

Source: Adapted from OECD (2014), Open Government in Latin America, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264223639-en.

Chapter 2 observed the absence of clear stewardship and leadership associated with the overall digital government agenda in Sweden, which may explain why there are too many goals and ambitions but low levels of awareness and clarity. The absence of a clearly recognised and identifiable digital government strategy with commonly defined and shared goals led to a limited number of strategic, co-ordinated and cohesive actions, and limited multi-stakeholder collaboration.

The fact that the Digital First agenda was perceived more as the result of a political exercise than the outcome of a collaborative effort might also explain the view of many stakeholders who underlined the strong focus of the agenda on processes rather than on outcomes (e.g. public trust).

Finding mechanisms for inter-institutional co-ordination to identify and prioritise policy goals and act upon the achievement of these priorities will be essential in the future to strengthen the basis for digital government actions.

For instance, using and/or setting dynamic channels and platforms to enable inter-institutional communication, consultation and collaboration with the digital ecosystem (see Figure 3.2), from within and outside the public sector, are necessary requirements to enable government openness, inclusive policy making, raise awareness and enable value co‑creation. All this can greatly contribute to reinforcing the overall trust in and ownership of the digital government agenda.

The promise of the new digitalisation agency is greatly centred on the co-ordination role this new body will have in terms of implementing the digital government agenda.

Some examples of inter-institutional co-ordination mechanisms exist in the context of digitalisation and digital government in Sweden, namely:

The Prime Minister National Innovation Council, chaired by the Prime Minister and composed of the Ministers of Finance, Education, Enterprise and Foreign Affairs and representatives mainly from the private sector. Yet, the political nature of the council links its continuity to terms of office and the administration’s decisions.

The Digitalisation Council, composed of ten representatives from the public sector and companies such as Google, provides advice in terms of digitalisation, proposing and evaluating new projects.

The eSAM, which is made up of 21 general directors from public sector agencies and a representative from the SALAR (see below). Participation is voluntary. Institutions share a secretariat and collaborate around digitalisation objectives to facilitate the relationship between the public sector, citizens and the private sector. In line with the Swedish culture, while joint potential actions in terms of digitalisation are discussed by all members, implementation falls on the level of the individual agency.

SALAR, an organisation for regional governments comprised of representatives from all 21 regions and all municipalities in Sweden. SALAR represents local governments’ interests and acts towards the achievement of common local goals.2

Even though these are examples of well-grounded inter-institutional co-operation, the capacities of these fora vary in terms of weight and mandate.

On the one hand, while politically relevant, the National Innovation Council has a strong focus on business innovation and competitiveness, without a specific focus on public sector innovation and digital government, and only acts as an advisory body, with no enforcement powers. However, the participation of the Minister of Finance in this body provides an opportunity to scale up the political relevance of digital government and the digitisation of the public sector should this body remain in place after changes of the central administration.

There are some signs of how the relevance of digital government and public sector innovation are gaining traction in the political sphere. For instance, in June 2017, during the Digital North conference (the Nordic-Baltic Ministerial Conference on Digitalisation), the Nordic Council of Ministers issued a Ministerial Declaration setting shared policy priorities in terms of digitisation in the Nordic and Baltic Area. The Declaration3 set three core objectives, including “strengthening the ability for digital transformation of [Nordic-Baltic] governments and societies, especially by creating a common area for cross-border digital services in the public sector”. This specific goal includes cross-border free flow and share of data in the region.

This shows how, albeit slowly, the relevance of digital government is incresing at the highest level of government, thus granting equal relevance to both the digitalisation of the public sector and the digitalisation of the economy.

As a result of the 2017 Ministerial Declaration, the Ministers for Co-operation (with delegated formal authority from their respective Prime Ministers), took a decision to create the Nordic Council of Ministers for Digitalisation for 2017-2020 with the responsibilities for advancing the commitments of the 2017 Declaration. The Minister for Housing, Urban Development and Information Technology (within the Ministry of Enterprise) has been appointed to represent Sweden in this council.

On the other hand, the Digitalisation Council stands as an “external” co-ordinated forum that is not directly in charge of dealing with matters related to digital government. This council replies to the Minister for Housing, Urban Development and Information Technology. However, its mandate is not strong enough to steer digital government efforts.

Even within such a consensus-based culture, achieving the digital transformation requires co‑ordinated and focused strategic decisions, securing whole-of-government approaches, coherency and integration across institutions. The consensus-based culture has prioritised discussions, but moving beyond informal collaboration and co-ordination based on dialogue and good intentions is pivotal to address systemic challenges in a co-ordinated and collaborative fashion. It is necessary to define common goals together that require integrated actions and demand a system of shared accountability supported by the use of policy levers (e.g. like funding) to advance such co-ordination.

The eSAM is de facto the continuation of the E-Delegation. It therefore inherited some of its problems and challenges (see Section 2.2 in Chapter 2). It appears to be a forum for dialogue and exchange with no co-ordination or enforcement powers. Additionally, it appears that the perception among stakeholders is that the eSAM’s focus is still strongly linked to e-government, not to digital government, and it is slow in taking decisions and action. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the motivation of the public bodies to participate in the eSAM, and, as such, its potential key role as part of the governance framework and partner for the agency if it attempts to find a balance between enforcement and intrinsic motivation to engage the various actors. Cases like the eSAM offer a solid basis for discussing and fostering co-operation, building on the consensus-based approach, but this is insufficient to steer the agile and rapid actions required by the digital age.

Final users and citizens are also absent from these fora, thereby slowing down the adoption of user-driven and open approaches for policy making. Most commonly, practices around users’ needs are still grounded on an e-government user-centred approach where those needs are assumed by public sector institutions, but they are not identified and explored together with the service users, who are not placed at the core of problem solving and service design processes. It will be essential to prioritise the use of data and digital tools to engage with the whole ecosystem of actors if the government of Sweden is willing to build on its digital government maturity as a lever to reinforce the levels of trust within its public sector as well as public trust towards the government as a whole.

Government as a platform: Collaboration for value co-creation

The Agency for Digital Government is expected to further increase the capacity of the government to act as a driver of change and contribute to achieving higher levels of collaboration and co-operation towards attaining the goals for digital government (see Section 3.2). These goals include objectives related to the development of a solid digital infrastructure, competencies within the public sector and data-driven innovation.

In light of the above, and the budget allocated to the agency for 2018-20 (including ring-fenced funds for open data and the national digital infrastructure; see Section 2.4.3), the agency will play a crucial role in addressing key policy challenges limiting digital government advancements (see Section 1.1.1), namely to:

address fragmentation and duplication of efforts at the agency level

streamline the national digital infrastructure

enforce the use of common guidelines and standards (soft infrastructure), and stimulate the development of new common components (e.g. mailboxes) (see Chapter 1)

streamline data-sharing practices building on the data registries and improve public sector data governance and infrastructure (see Chapter 4)

use open government data to build a data infrastructure for data-driven innovation (see Chapter 5).

Yet, the recognised need for more efficient co-ordination related to digital government across the public sector in Sweden seems to have been the main driver behind the creation of the new agency rather than a real ambition to use such a new body as a driver, enabler and platform for digital innovation, value co-creation and collaboration. The agency’s mandate includes, for instance, responsibilities in terms of open data publication, yet the goal of leveraging the new agency as an active player of the open data ecosystem is unclear (see Chapter 5).

While the perception is that the new agency is seen as a driver for greater inter-institutional co‑ordination (see Section 3.3), it will be essential for it to create dynamic spaces (either physical or digital) for risk-controlled experimentation, digital- and data-driven innovation, multi-stakeholder engagement, and problem-solving collaboration. The OECD collected evidence on stakeholders’ need to “start building a beta version” of a smarter and agile government, and provide a platform where officials could design, experiment and test ideas in risk-controlled environments. The role of the new agency should be capitalised in this respect.

However, the organisational culture within the Swedish public sector emerged as both as a platform and a barrier for digital and data-driven innovation.

Some aspects of the Swedish public sector culture create a basis that can be used to lever digital innovation. These positive factors are related to equality (no hierarchic management models), teamwork mentality, and public officials’ high education levels, networking co‑operation and digital skills; and, in some cases, public officials have shown curiosity to experiment with new ways of doing things.

Together with the advancements in terms of e-government (see Chapter 1), these traits provide a sense of the maturity of the Swedish public sector to move towards a digital government. From this perspective, the agency would contribute to putting this capability into action.

Yet, some negative cultural barriers are also evident. These challenges are related to a state of complacency with the status quo (lack of urgency), a “focus on facts and not experimentation”, and unwritten social codes – e.g. to avoid causing discomfort to others or unpleasant social and work environments (Dålig stämning as known in Swedish). These seem to affect open discussions, trigger slow decision making, and support the focus on big projects rather than fostering a more incremental mindset to experiment with small initiatives that can then be matured and scaled up.

Evidence collected by the OECD indicates that this consensus-seeking culture can also lead to restricted discussions, as those who favour a cultural change may not freely express themselves so as not to upset the status quo.

On the one hand, as mentioned above, this may result from self-reticence to express one’s opinion in order to maintain cordiality and avoid conflict in line with the Swedish social norms. On the other hand, public officials also mentioned that expressing disagreement can result in the actual implementation of soft and “informal corrective measures” by managers (e.g. seclusion from relevant activities and focus on repetitive tasks), therefore leading to resignation of affected public officials. This context creates an organisational culture that punishes creativity and rewards compliance.

In addition, in Sweden, the perceived financial stability exerts a negative incentive to change the status quo as it does not create the sense of urgency to use resources to do more and better in terms of digital government. This probably explains, despite some exceptions, the apparent generalised low sense of curiosity across the public sector to experiment and explore opportunities to find new ways to create value through digital and data-driven public sector innovation. Recent OECD work provides evidence of how a vision for data-driven innovation across public sector institutions (e.g. data stewardship) is a key precondition complementing that of the main co-ordination bodies (often within the centre of government) to achieve systemic change and drive digital and data-driven innovation (OECD, 2018).

Additionally, stakeholders also expressed how external factors can hinder data-driven innovation. For instance, they pointed out how the government-media relationship can deter experimentation by public officials due to fear of failure and the resulting media scrutiny and criticism. Stakeholders also did not identify journalists as potential partners.

The role of the new agency has to be understood in light of the above-mentioned cultural context.

This body will face the challenge of going beyond co-ordination responsibilities in order to facilitate and adopt dynamic, agile, multi-stakeholder collaboration approaches and capitalise on the consensus-based culture of the public sector to bring actors from all sectors on board and drive change by enabling safe spaces that motivate creativity instead of punishing it.

The new agency should be designed and conceived as a space to enable the digital transformation of the Swedish public sector in order to tackle the current existing systemic deficit in terms of:

Pursuing the implementation of open by default and user-driven approaches for policy making across the broader public sector.

Fostering a data-driven public sector as pivotal for the digital transformation, and digital innovation, e.g. leveraging the role of this new body as a platform and space (e.g. data lab, innovation lab, digital studio) for the design, testing and iteration of digital and data-driven initiatives, and the provision of technical support and guidance for the development of data-driven and digital innovation initiatives.

Building up competencies and skills for data- and user-driven public bodies, creating people-driven networks, and providing spaces for crowdsourcing and creating collective intelligence to solve policy challenges and contribute to the development of a smarter knowledge-based soft infrastructure.

Promoting the use of approaches that are innovative, user-driven, collaborative and focused on problem-solving across public sector institutions.

Steering, guiding and accompanying public sector institutions towards the creation of data-driven public value.

Identifying key players across all sectors in Sweden, engaging them and setting strategic partnerships and communities to co-create solutions for collective challenges.

The successful establishment of the agency represents an important opportunity for the Swedish government to adjust the existing governance for digital government as needed to achieve a full digital transformation of the Swedish public sector and enabling collaborative spaces where actors from all sectors can exchange ideas, interact and experiment.

For instance, the GCTools Team within the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat created the GCcollab portal as a closed online collaborative platform hosted by the government of Canada where Canadian public servants (federal, provincial, territorial and municipal), academics, students and other key communities can communicate, exchange ideas, co‑create content, collaborate and establish communities around specific topics of common interest. The GCTools Team has also created similar initiatives like the GCconnex (a professional networking platform) and GCpedia (a wiki-based platform for knowledge sharing) that are available for federal public servants only.

The development of these platforms followed an iterative and incremental approach, therefore broadening the scope of collaborative options available to the user and their degree of openness. While GCPedia was developed first, then GCConnex, and most recently, GCCollab, GCPedia allowed for crowdsourcing documents but did not allow discussion forums. GCConnex expanded the collaborative options with blogs, discussion forums, polling and more, but was only open to federal public servants. GCCollab builds on all the things available to the other tools, but now allows users from outside the federal public service to join.

In some OECD countries, the definition of creative environments inside policy co‑ordinating units or key public sector institutions and agencies (either formal or informal) has aimed to enable such collaborative environments, while being used to build a digital innovation ecosystem inside the public sector (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Enabling spaces for public sector creativity and capacity building across OECD member and partner countries

Australia

DesignGov was an 18-month pilot (closed in December 2013) of a whole-of-government innovation lab endorsed by the portfolio secretaries of the Australian Public Service (APS) and was run from the Industry Department with support (active or in-kind) from a number of other government agencies. The mission of DesignGov, as set out in its Charter document, was to “inspire creativity, innovation and a more citizen-centric approach through consultation, collaboration and co-design.” It was to “build innovation capability in the APS and provide for better outcomes through applied problem solving, including at the interface between the APS, other jurisdictions and providers, and the users of services”. It had four streams of activity including: demonstration projects’ engagement, education and awareness capability building, methodologies and tools operating framework, governance and reporting.

Chile

The Laboratorio de Gobierno is a multidisciplinary institution of the government of Chile which was set up to implement the President’s mandate on public sector innovation. Announced by former President Michelle Bachelet in 2014, the Laboratorio has the mission of developing, facilitating and promoting human-centred innovation processes within public sector institutions. The Laboratorio represents the Chilean government’s new approach to solving public challenges which put the citizens right in the centre of public action and transformation processes.

The Laboratorio is administratively part of CORFO, the Chilean Economic Development Agency (under the auspices of the Ministry of Economy), and has a governing board composed of five ministries (including the Ministries of Economy, Finance, Social Development, Interior and Public Security, and the General Secretariat of the Presidency), the National Civil Service Directorate and three members of civil society.

The Laboratorio acts as a learning-by-doing area for civil servants and provides a controlled environment that permits risk-taking and connects a diversity of actors related to public services to co-create and test solutions. The Laboratorio engages in two main streams of activity: 1) innovation projects and ecosystem (these include actions aimed at supporting public sector institutions to seek innovative solutions that improve the services); and 2) innovation capabilities (actions focused on developing the capabilities of civil servants to initiate and carry out innovation processes within public sector institutions through learning-by-doing experiences).

Mexico

In Mexico, the General Direction of Open Data, a body within the Office of the President, has followed a test-and-experiment model for the development of initiatives using open government data that can be then scaled up and transferred to public sector institutions to reach maturity and become sustainable.

The Office of the President does not receive direct budget allocation from the federal government, therefore this approach has enabled the General Direction of Open Data as de facto a datalab that should operate with a restricted budget. As a result, the implementation of agile and flexible models of work have guided the implementation of these efforts in order to reduce losses and risks and maximise impact.

United States

The Innovation Lab of the United States’ Office for Personnel and Management aims to build innovative design workforce capabilities. The lab guides its activities with the mission of lead/do/teach, engaging in projects with a variety of government institutions as well as providing customised training courses and information sessions. In terms of evaluating the impact and results of its work and projects, the Innovation Lab looks for concrete results such as cost savings and partnerships formed or numbers of people reached. For example, the lab has a dedicated staff to decide on performance measures for certain projects, in collaboration with project partners. For broader workshops and training courses, the lab also measures customer satisfaction and gains feedback through surveys at the end of classes.

Source: Based on OECD (2017), Innovation Skills in the Public Sector: Building Capabilities in Chile, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273283-en.

There is an urgent need to capture the missed opportunity to correct a situation in which Swedish public sector agencies, currently playing the role of administrators, could exert and play a more proactive role to foster data-driven and digital public sector innovation. In general terms and despite the availability of some isolated efforts, data-driven and digital innovation is still occasional, siloed and sometimes unknown.

Additionally, due to a risk-averse and compliant organisational ethos, it does not seem to be a natural traction for digital and data-driven innovation. Even Vinnova, a key agency in this regard, seems to be playing more of an administrative and passive role (e.g. managing funds and grants for innovation projects such as labs), rather than seeing itself as a promoter of public sector innovation, e.g. identifying and soliciting champions to create capacities to foster public sector innovation and speed-up innovation procurement processes.

References

OECD (2018), Open Government Data Report: Enhancing Policy Maturity for Sustainable Impact, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264305847-en.

OECD (2017), Innovation Skills in the Public Sector: Building Capabilities in Chile, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273283-en.

OECD (2014), Open Government in Latin America, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264223639-en.

Notes

← 1. For more information see: www.regeringen.se/regeringens-politik/digitaliseringspolitik/mal-for-digitaliseringspolitik.

← 2. For more information see: https://skl.se/tjanster/englishpages.411.html.

← 3. For more information see: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/5ed83530b83c4e4ba85338c29eb50c63/ministerial-declaration.pdf.