In line with Pillar 2 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies, Chapter 2 analyses the governance of digital government in the Republic of Türkiye with a focus on the contextual factors and institutional models that underpin the digital transformation of its public sector. The first section reviews the overall political and administrative culture in place. The second section looks at the socio-economic factors and technological context of the country. The third section analyses the macro-structure and the leading organisation in the Turkish public sector. The last section focuses on the existing co-ordination and compliance arrangements and mechanisms to ensure the coherence and sustainability of the public sector digital transformation.

Digital Government Review of Türkiye

2. Contextual factors and institutional models

Abstract

Introduction

In today’s geopolitical context, unforeseeable risks challenge governments to demonstrate their resilience, responsiveness and agility more than ever. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the digital transformation of the public sector at record speed and revealed how far the strategic use of digital technologies and data can be an asset in responding to these challenges. Governments have placed digitalisation at the core of their national agenda to further transformation efforts. It is imperative that governments continue to make sustained progress in the public sector digital transformation.

The complexity of digital transformation requires robust governance to drive change across the public sector. Such governance enables governments to envision and lead coherent and sustainable digital transformation across the public sector, establishing a collaborative and inclusive digital ecosystem. The results of the OECD Digital Government Index 2019 (OECD, 2020[1]) show that solid governance is critical for digital government maturity. Effective governance frameworks ensure the necessary cultural shift from thinking in silos to a strategic systems-thinking approach and builds the institutional foundations for the design and delivery of citizen-driven policy and services.

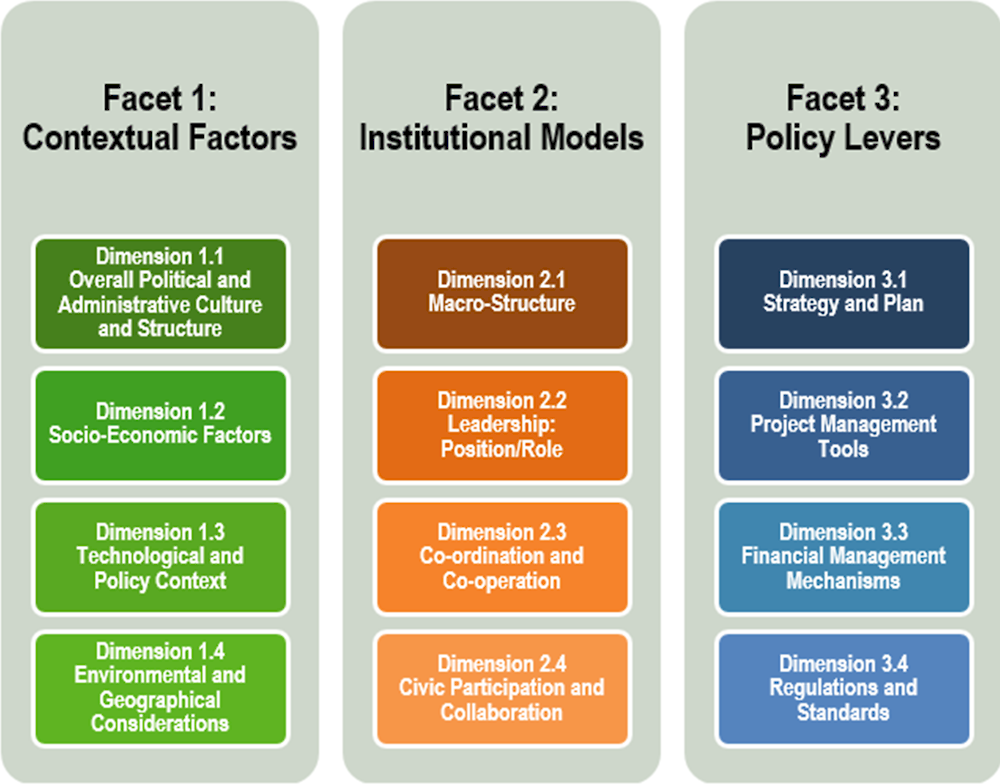

Grounded in the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]), the E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government (OECD, 2021[3]) presents a framework (see Figure 2.1) that supports governments to strengthen their digital governance. The framework provides guiding policy questions, drawn from the insights, knowledge and best practices of OECD member and non-member countries, which support policymakers to develop and implement digital government strategies towards being a mature, digitally enabled state.

Figure 2.1. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government

Source: OECD (2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government presents three critical governance facets (applied to the Turkish context and analysed in Chapter 2 and 3):

Contextual Factors which define country-specific characteristics – political, administrative, socio-economic, technological, policy and geographical – to be considered when designing policies to ensure a human-centred, inclusive and sustainable digital transformation of the public sector.

Institutional Models that present different institutional set-ups, approaches, arrangements and mechanisms within the public sector and digital ecosystem which direct the design and implementation of digital government policies in a sustainable manner.

Policy Levers which support governments to ensure a sound and coherent digital transformation of the public sector.

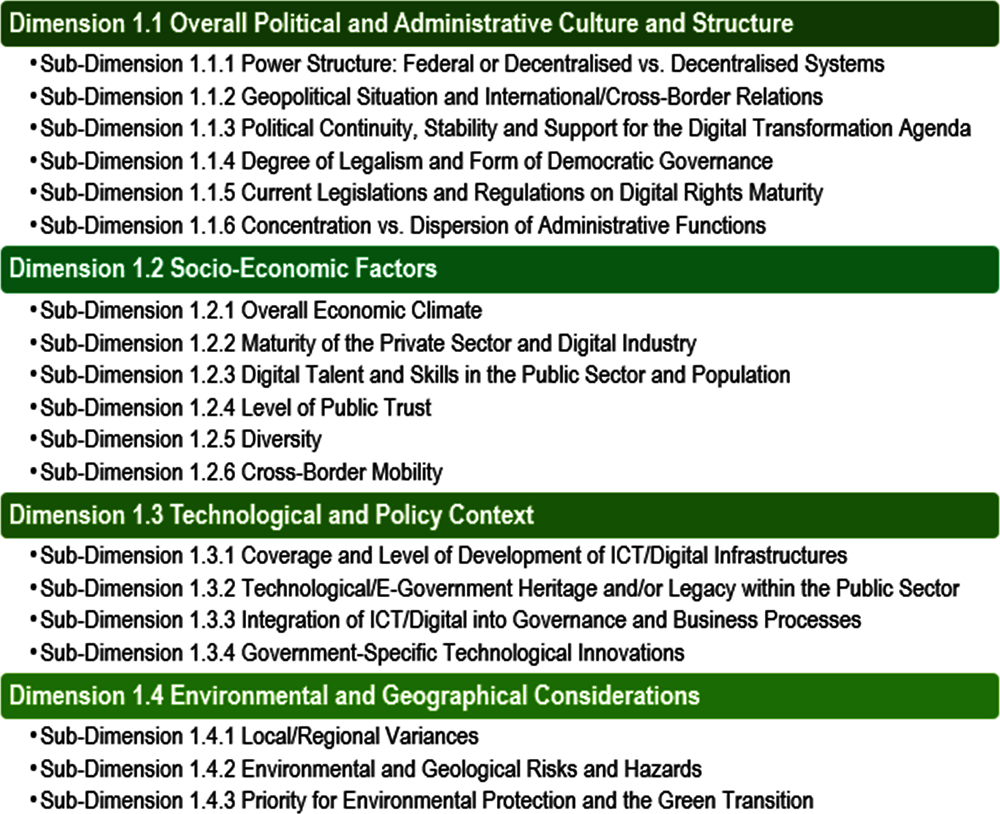

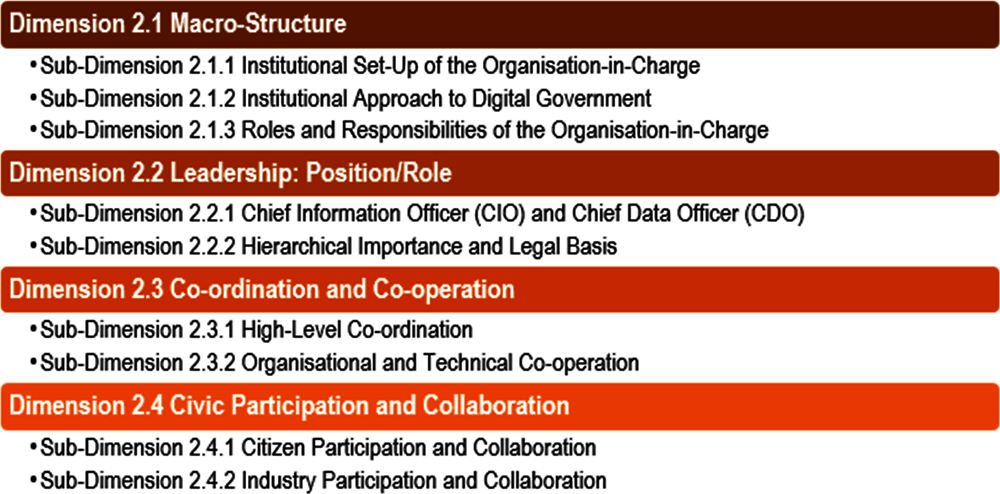

This chapter will analyse the governance of Türkiye’s digital government in four main sections, according to the first two facets of the Governance Framework – Facet 1: Contextual Factors and Facet 2: Institutional Models (see Figures 2.2 and 2.3). The first section assesses the overall political and administrative culture in place including sub-dimensions on the country’s power structure, political continuity, stability and support for the digital transformation agenda. The second section discusses socio-economic factors and technological context of the country such as the levels of digitalisation across the population and the overall maturity of digital government. The third section analyses macro-structure and the leading organisation in the Turkish public sector. The last section focuses on the existing co-ordination and compliance mechanisms to ensure the coherence and sustainability in the public sector digital transformation.

Figure 2.2. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government - Contextual Factors

Source: OECD (2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

Figure 2.3. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government - Institutional Models

Source: OECD (2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

Overall political and administrative culture

A country’s political and administrative culture greatly influences the governance of digital government. It is important for governments to understand these distinctive characteristics when designing a governance framework that best suits their national circumstances. They present different opportunities and challenges for governments in establishing and implementing national strategies on digital government.

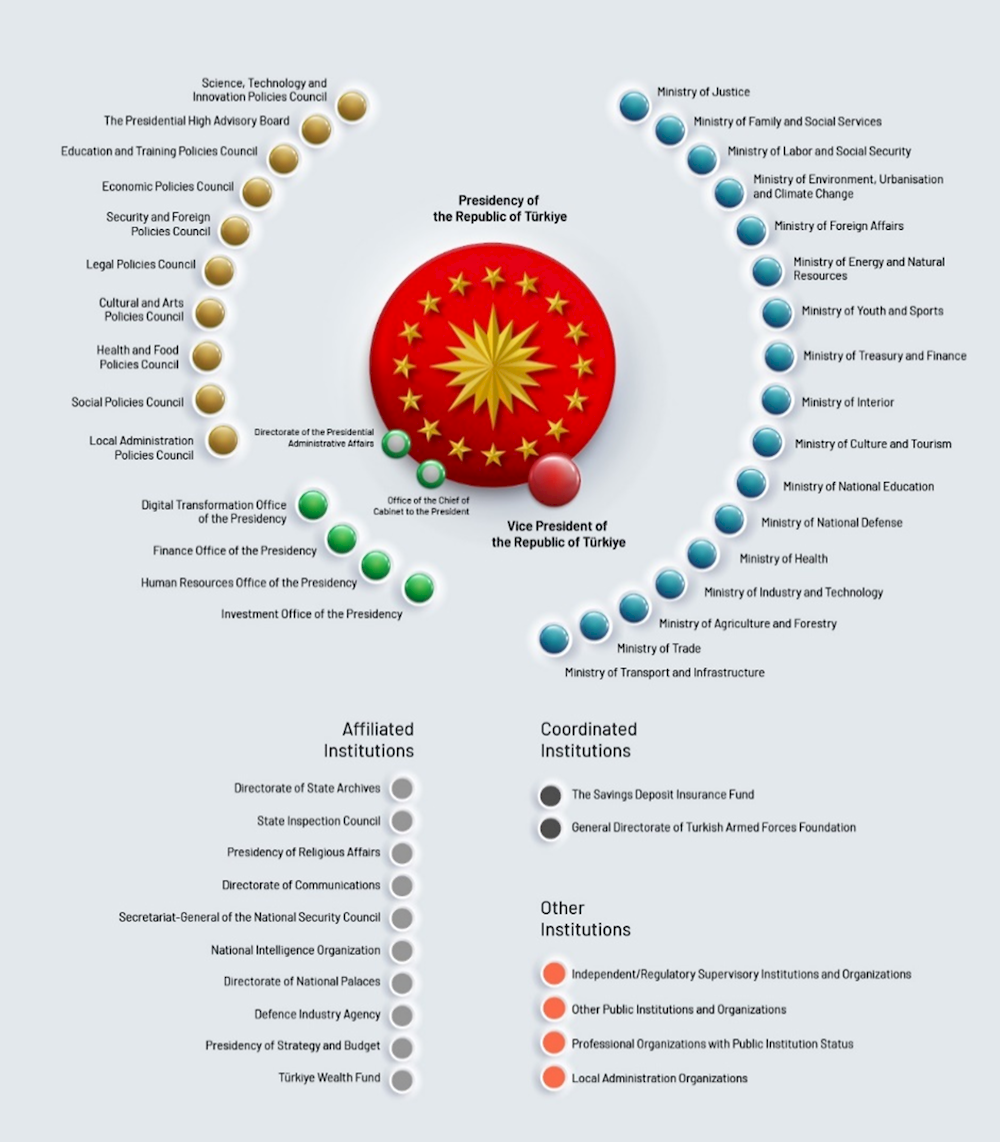

Türkiye is a presidential and constitutional republic with a population of approximately 84.7 million (TÜİK, 2021[4]). In 2018, Türkiye changed its long-standing parliamentary system to a presidential system. The president holds the executive power while the legislative and judicial powers are vested in the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye, and independent and impartial courts respectively. Most of the key institutions and regulatory authorities are affiliated directly with the executive power (see Figure 2.4) (EC, 2021[5]).

With a long history of strong traditional administrative practices and culture, Türkiye has a centralised power structure with expanded executive power. The public administration is organised in a two-tier structure, central and local government. At the central level, the president delegates the executive power to the Presidential Cabinet, which consists of the Vice President and Ministers. The 17 line ministries devise their own policies which the president validates. In addition, under the Presidency, four offices report directly to the president on finance, HR, digital transformation and investment. The administrative de‑concentration divides Türkiye into 81 provinces, which are composed of metropolitan municipalities, municipalities and villages with mayors and headmen determined by local elections. Governors of provinces, appointed by central government, function as the highest representative and steer public services at provincial level. Leadership at the local level is administered closely by the centre (EC, 2021[5]).

The longevity in leadership over the period of last 20 years has provided continued political support throughout the digitisation and now digital transformation agenda since the early 2000s. The country’s modernisation effort put e-government at the core of increasing efficiency and effectiveness of its large public sector. In 2008, under the leadership of the prime minister, the government launched türkiye.gov.tr, the e-Government Gateway. Türkiye continued to promote e-government by including specific objectives and policies in national development plans to provide user-oriented services. In 2016, the government developed its first standalone national e-government strategy, the 2016-2019 National e-Government Strategy and Action Plan (Ministry of Transport, Maritime Affairs and Communications, 2016[6]). The next chapter will cover the strategy and action plan extensively as a key policy lever.

Figure 2.4. Organisation of the Presidency of Türkiye

Note: Accurate as of December 2022.

Source: Government of Türkiye (2022[7]), The Government Organization Central Records System, https://detsis.gov.tr/ (accessed on 22 November 2022).

In general, Türkiye’s current political and administrative culture supports public sector digital transformation. The centralised power structure provides long-standing and high-level political support and offers Türkiye the opportunity to develop and implement the next digital government strategy in a coherent and sustainable manner. However, the Review noted that in the public sector more widely, there are elements of civil service culture and bureaucratic principles that may prove to be a barrier for achieving the desired change. For instance, one of the critical contributors to achieving digital transformation is the public sector workforce (which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 4). However, public service management and government human resources management in Türkiye is governed by the Civil Servants’ Act of 1965, which despite several amendments, may benefit from being reformed in light of the needs for a future-fit workforce and the provisions of the OECD Recommendations on Public Service Leadership and Capability and Public Integrity (OECD, 2019[8]; 2017[9]). Indeed, while one of the strengths of the Civil Servants’ Act is its long-standing legal basis for merit-based recruitment and preserving the neutrality of the civil service against potential politicisation, the review team observed concerns about how these are being conducted in practice, which are echoed by several documentary sources (EC, 2022[10]; OECD, 2019[11]). Furthermore, Türkiye’s large geographical size might also present some challenges in driving equally inclusive digital transformation across the entire public sector. As such it is recommended to be mindful of the overall political and administrative culture of the country and its potential impacts on the governance needed to support digital transformation.

Socio-economic factors and technological context

Understanding the socio-economic and technological context is equally important when governing digital transformation of the public sector to contribute to further economic and social development. The governance needs to take into consideration the overall economic climate, the level of digital maturity of the society, its demographic characteristics as well as the country’s past, current and prospective technological developments.

Türkiye’s economy is considered well advanced and resilient, yet the economic outlook is more uncertain than usual. With a strong response to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was able to rebound quickly from the crisis and return to growth (EC, 2021[5]). In 2021, Türkiye’s economy grew 11%, making it one of the fastest among G20 countries. However, its monetary stimulus led to deterioration of the country’s macro-financial conditions. Over the period from January 2021 to June 2022, the Turkish Lira (TRY), relative to the US Dollar (USD), has depreciated 56.5%.1 The country’s inflation rate raised to 61.1% in the first quarter of this year, directly affecting households and industry (World Bank, 2022[12]).

The country’s performance in the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) shows consistent improvement over the last two decades; however, inequality hinders further development. Between 1990 and 2019, Türkiye’s HDI value increased from 0.583 to 0.820, putting the country in the very high human development category with an increase of 40.7 percent. While Türkiye is below the 0.898 average of the very high human development group, it is above the average of 0.791 for countries in Europe and Central Asia. Nonetheless, levels of inequality affect the human development score significantly. The inequality-adjusted HDI value shows a significant drop to 0.683, putting the country far below the group average of 0.800 (see Table 2.1) (UNDP, 2020[13]).

This insight also aligned with main findings of the OECD Economic Policy Reforms 2021: Going for Growth (OECD, 2021[14]). The report identifies that the country needs to overcome structural challenges that include low levels of participation in the labour force from women, weak skills, and rigid employment rules hampering more inclusive and sustainable economic policy. Inequality in human development can prevent vulnerable groups from performing well in a digital society and benefitting from digital transformation, thereby widening the digital divide.

Table 2.1. Türkiye’s inequality-adjusted HDI for 2019 relative to selected countries and groups

|

IHDI value |

Overall loss compared to HDI value (%) |

Human inequality coefficient (%) |

Inequality in life expectancy at birth (%) |

Inequality in education (%) |

Inequality in income (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Türkiye |

0.683 |

16.7 |

16.5 |

9.0 |

16.5 |

24.1 |

|

Azerbaijan |

0.684 |

9.5 |

9.4 |

13.9 |

5.3 |

8.9 |

|

Serbia |

0.705 |

12.5 |

12.1 |

4.9 |

7.5 |

24.0 |

|

Europe and Central Asia |

0.697 |

11.9 |

11.7 |

9.7 |

8.2 |

17.2 |

|

Very high HDI |

0.800 |

10.9 |

10.7 |

5.2 |

6.4 |

20.4 |

Source: UNDP (2020[15]), “The next frontier: Human development and the Anthropocene – Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report – Türkiye”, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/tr/UNDP-TR-BRIEFING-NOTE-TURKEY-EN.pdf.

With a population of 84.7 million, Türkiye is the 17th most populous country in the world (3rd most within the OECD) and the 37th largest country in the world by territorial landmass (6th largest within the OECD) but has a population density comparable to much smaller countries such as Austria, Cuba and Sierra Leone (TÜİK, 2021[4]). The population is relatively young, with 22.4% falling in the 0–14 age bracket. These figures underline the perception in Türkiye of the society being relatively youthful and therefore more comfortable with the use of digital services. Indeed, several organisations identified that the country’s young population was the biggest factor in providing an incentive for digital transformation. Nevertheless, in the last fifteen years the proportion of the population over 65 has increased from 7.1% to 9.7% pointing to a need to avoid overlooking the needs of all parts of society.

In Türkiye, access to and use of communications infrastructures, services and data have progressed over the past decade. Nevertheless, limited access and use, and insufficient digital skills across society remains an impediment to wider adoption and use of digital technologies. According to the OECD Going Digital Toolkit, while 92% (OECD average at 89%) of households have broadband connection, and at least a 4G mobile network covers 96.7% (OECD average at 98%) of the population, the country performs far below the OECD average in certain indicators. In particular, only 55.5% (OECD average at 76.8%) of businesses have broadband at 30 Mbps or more. Türkiye also lags behind in the indicator that measures the share of adults’ who are proficient at problem solving in technology-rich environments being 7.8% (OECD average at 30.6%) (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Going Digital indicators - Türkiye

|

Indicators |

Türkiye |

OECD average |

|---|---|---|

|

Fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants |

21.6 |

34.4 |

|

M2M (machine-to-machine) SIM cards per 100 inhabitants |

8.8 |

31 |

|

Mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants |

83.2 |

124.5 |

|

Share of households with broadband connections |

92 |

89 |

|

Share of businesses with broadband contracted speed of 30 Mbps or more |

55.5 |

76.8 |

|

Share of the population covered by at least a 4G mobile network |

96.7 |

98 |

|

Share of adults proficient at problem solving in technology-rich environments |

7.8 |

30.6 |

Source: OECD (2022[16]), OECD Going Digital Toolkit – Türkiye (database), https://goingdigital.oecd.org/countries/tur.

The 2021 OECD Economic Survey of Türkiye also supports this data, and underlines that insufficient digital skills and limited access to fast broadband creates barriers for the Turkish firms to adopt the most advanced digital technologies (OECD, 2021[17]). The Survey found that while the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the use of digital technologies a digital divide between large and small size firms and overall socio-economic groups remains a challenge. In the International Digital Economy and Society Index (I‑DESI) 2020, Türkiye underperformed in five dimensions: Connectivity, Human Capital, Use of Internet Services, Integration of Digital technology and Digital Public Services among 45 countries (27 European Union (EU) member states and 18 non-EU countries) (see Table 2.3). It was lagging behind, especially, in the Connectivity and Human Capital (Digital Skills) dimensions compared to its European and international peers (EC, 2020[18]).

Table 2.3. International Digital Economy and Society Index (I-DESI) 2020: Türkiye’s performance

|

Connectivity |

Human capital (digital skills) |

Use of internet services |

Integration of digital technology |

Digital public services |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Avg. of 27 EU countries |

62 |

42 |

47 |

41 |

56 |

|

Avg. of 18 non-EU countries |

59 |

43 |

52 |

46 |

60 |

|

Türkiye |

43 |

23 |

37 |

24 |

45 |

Source: EC (2020[18]), International Digital Economy and Society Index 2020, https://doi.org/10.2759/757411.

Nevertheless, Türkiye has maintained steady progress in providing digital services to the citizens. In accordance with the 2016-2019 National e-Government Strategy and Action Plan and the Eleventh Development Plan (2019-2023), Türkiye has integrated an increasing number of services into the e‑Government Gateway (discussed in more detail in Chapters 5 and 6) (Ministry of Transport, Maritime Affairs and Communications, 2016[6]; Presidency of Strategy and Budget, 2019[19]). The I-DESI 2020 shows the impact of these efforts with Türkiye advancing in the Digital Public Services Dimension from a normalised score of 27 in 2017 to 45 in the following year (EC, 2020[18]). The eGovernment Benchmark 2022 of the European Commission also supports Türkiye's progress in the provision of online services to its citizens (EC, 2022[20]) (see Table 2.4). In addition, in the UN e-Government Survey 2022, Türkiye ranked 48th among 193 countries, landing in the “Very high” group with the overall highest performance being in the Online Service Index (UN, 2022[21]) (see Table 2.5).

Table 2.4. eGovernment Benchmark 2022: Türkiye’s performance

|

User centricity |

Transparency |

Key enablers |

Cross-border services |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EU 27+ average |

88.3 (88.3) |

59.5 (64.3) |

68.7 (65.2) |

54.5 (54.8) |

|

Türkiye |

93 (92) |

62 (56) |

79 (71) |

54 (44) |

Note: Numbers in brackets indicate scores from the eGovernment Benchmark 2021.

Source: EC (2021[22]), eGovernment Benchmark 2021 - Country Factsheets, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/redirection/document/80569; EC (2022[20]), The eGovernment Benchmark 2022, https://doi.org/10.2759/721646.

Table 2.5. UN E-Government Survey 2022: Türkiye’s performance

|

Rank |

E-Government Development Index (EGDI) Group |

EGDI |

Telecommunication Infrastructure Index (TII) |

Online Services Index (OSI) |

Human Capital Index (HCI) |

E-Participation Index (EPI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Türkiye |

48 |

Very High |

0.7983 |

0.6626 |

0.86 |

0.8722 |

0.7841 |

Source: UN (2022[21]), E‑Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government, https://desapublications.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2022-09/Web%20version%20E-Government%202022.pdf.

Furthermore, in the World Bank GovTech Maturity Index 2022, Türkiye is classified in the “GovTech Leaders” group along with its OECD peers (World Bank, 2022[23]). The OECD’s upcoming edition of the Digital Government Index will show how Türkiye has progressed towards digital government maturity among the OECD economies.

The socio-economic context in Türkiye provides a robust foundation for the governance of digital government. It would enable the government of Türkiye to invest in allocating the necessary financial, human and operational resources to support the digital transformation agenda based on long-term economic and social development goals of the country. Meanwhile, the government can also strategically allocate budget to specific digital transformation efforts to yield more economic and social outcomes. In regards to the technological context, although Türkiye has made good progress, there remain challenges in transforming into a mature digital government. These include enhancing connectivity and digital skills across society, especially for businesses, to help achieve embed a digital mindset into governance and business processes. Türkiye can benefit from promoting government-specific innovations to improve the public sector's internal processes and public service design and delivery in collaboration with the private sector. In addition to the government’s support mechanisms and incentives focusing on the digital transformation of businesses, particularly SMEs, MSMEs and entrepreneurs, there are also opportunities with respect to the work being carried out by the government to consider the increased role of public cloud computing in Türkiye where private sector investment could be encouraged to support both the public sector and wider economy of the country.

Macro-structure and leading public sector organisation

A sustainable digital transformation across the public sector derives from a clear, effective institutional model. This lays the ground for governments to adopt a holistic, coherent and co-ordinated approach to digital transformation. The formal and informal institutional arrangements enable governments to set a strategic vision, provide the necessary leadership and secure co-ordination and collaboration across the digital government ecosystem. They also provide concrete ground for governments to clarify and systematise institutional and personal leadership (e.g. Chief Information Officer, Chief Data Officer) (OECD, 2021[3]).

In order to take digital government to its full maturity, it is imperative to have an “organisation-in-charge” to lead and co-ordinate the digital transformation agenda with precise roles and responsibilities agreed and recognised across the public sector. Taking into consideration the different contextual factors, especially, the country’s political and institutional culture, this leading organisation needs to be strategically positioned within the government and have sufficient financial and human resources. It needs to be empowered to secure necessary political support, incorporate the strategy into a more comprehensive national reform agenda, and gain legitimacy within the public sector (OECD, 2021[3]).

The organisation-in-charge should embody decision-making, co-ordination and advisory responsibilities. In fact, it needs to make key decisions and be accountable for them across the government; co-ordinate with other public sector organisations and secure the alignment of the development of digital government projects with the national digital government strategy; and finally provide guidance and advice to other public sector organisations on the development, implementation and monitoring of digital government strategies (OECD, 2021[3]).

The OECD Digital Government Index (DGI) 2019 revealed that all 33 participating countries designated an organisation to lead and co-ordinate decisions on digital government at the central level of government. Nevertheless, approaches to the institutional structure varies from country to country. Some position this leading organisation under the Centre of Government (CoG) (e.g. Chile, France and the United Kingdom) whereas others in a line ministry (e.g. Estonia, Greece and Luxembourg) or under a co‑ordinating ministry such as finance or public administration (e.g. Denmark, Korea, Portugal and Sweden) (see Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Digital Government leadership – Examples from United Kingdom and Portugal

The Central Digital and Data Office and Government Digital Service of the United Kingdom

The Central Digital and Data Office (CDDO) and the Government Digital Service (GDS) of the United Kingdom lead the digital government agenda at the centre of government and part of the Cabinet Office. The CDDO leads government’s Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT) Function and set the strategic direction for government on digital, data and technology. It also administers standards such as the Government Service Standard, the Technology Code of Practice and the Cabinet Office Spend Controls for Digital and Technology. The GDS works across the whole government to assist departments transform its public services. GDS has built and maintained several cross-Government as a Platform tools such as GOV.UK, GOV.UK Verify, GOV.UK Pay, GOV.UK Notify and the Digital Marketplace.

The Administrative Modernisation Agency of Portugal

Portugal's digital transformation agency, the Administrative Modernisation Agency (AMA), was created in 2007 and sits within the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. It exercises the powers of the Ministry of State Modernisation and Public Administration in modernisation, administrative simplification and digital government, and is under the supervision of the Secretary of State for Innovation and Administrative Modernisation. The agency has a top role in the development, promotion and support of the public administration in several technological fields and is in continuous contact with focal points at institutions relevant for the implementation of digital government projects. It is responsible for the approval of ICT and digital projects over EUR 10,000 and chairs the Council for ICT in the public administration.

Source: UK Central Digital and Data Office, (2023[24]), About Us, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/central-digital-and-data-office/about; OECD (2021[3]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

Digital Transformation Office in Türkiye

In Türkiye, the Digital Transformation Office (Dijital Dönüşüm Ofisi, DTO), one of four offices directly reporting to the President, has a mandate to lead and co-ordinate the digital government agenda across the public sector (see Box 2.2). During its transition from the parliamentary to the presidential system, Türkiye consolidated its fragmented digital transformation efforts under one roof. In accordance with the Presidential Decree No. 1, the DTO was established in 2018 with strong support from the highest power and necessary legal basis (Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2018[25]) (see Box 2.2). In 2019, Presidential Decree No. 48 strengthened its roles and responsibilities by assigning the e-government tasks, previously performed by the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure (Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2019[26]).

Box 2.2. Mandate of the Digital Transformation Office of Türkiye

The aim of the office is to co-ordinate all actions in Türkiye's digital transformation, which includes holistic transformation in terms of people, business processes and technology in order to increase economic and social welfare through the use and development of digital technologies.

Source: OECD (2021[27]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye Lead/Co-ordinating Government Organisation Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Box 2.3. Legal foundation for the Digital Transformation Office of Türkiye

Presidential Decree 1 – Chapter Two Digital Transformation Office

Article 527 - Duties of the Digital Transformation Office

1. The duties of the Digital Transformation Office are as follows:

a. Leading the digital transformation of the public sector in compliance with the goals, policies and strategies determined by the President, mediating the delivery of Digital Türkiye (e‑government) services, enhancing inter-institutional co-operation and providing co‑ordination in these fields.

(1) Pursuant to Article 6 of the Presidential Decree No. 48 published in the Official Gazette no. 30928 dated October 24, 2019, chapter no. “Chapter One” and the chapter title “Establishment and Definitions” have been added to this Decree following the title “Presidential Offices” of Section Seven.

(2) Pursuant to Article 9 of the Presidential Decree No. 48 published in the Official Gazette no. 30928 dated October 24, 2019, chapter no. “Chapter Two” and the chapter title “Digital Transformation Office” have been added to this Decree following Article 526.

b. Preparing a road map for digital transformation in the public sector.

c. For the aim of creating an ecosystem for digital transformation; enhancing co-operation among the public sector, private sector, universities and non-governmental organizations, and promoting their participation in the design and presentation of digital public services.

d. Providing opinion to the Strategy and Budget Directorate with regard to investment project proposals prepared by public institutions and organizations in matters related to its field of duties, and following up and directing where necessary the developments on the projects put into practice.

e. Developing projects for improving information security and cyber security.

f. Developing strategies for effective use of big data and advanced analysis solutions in the public sector, leading respective implementations and providing co-ordination.

g. Leading artificial intelligence applications in the public sector with regard to prioritized project areas, and providing co-ordination.

h. Developing projects for improving local and national digital technologies by enhancing their use in the public sector and for building awareness in this regard.

i. Identifying a strategy for the procurement of digital technology products and services by public institutions and organizations in a cost-effective manner.

j. Providing support where necessary to projects and implementations related to its field of duties.

k. Co-ordinating the definition and sharing in an electronic medium of central, rural and foreign organizational units of those institutions and organizations involved within the state organization.

l. Proposing policies and strategies in matters related to its field of duties.

m. Performing other duties assigned by the President.

Article 527/A – Chief Digital Officer

1. The Director of the Digital Transformation Office is the Chief Digital Officer.

Note: The text is official translation provided by the Digital Transformation Office (https://cbddo.gov.tr/en/presidential-decree-no-1).

Source: Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2018[25]), Presidential Decree No. 1, https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/19.5.1.pdf.

The DTO has the mandate to establish a digital transformation roadmap for the Turkish public sector. It co-ordinates all matters related to e-government, digital public administration, cybersecurity, critical infrastructures, big data, artificial intelligence (AI) and implementation of emergent technologies. Under the leadership of the president of the DTO who also serves as the government Chief Digital Officer, the following nine sub-departments are responsible to plan and implement relevant activities within their scope of work (Digital Transformation Office, 2022[28]):

Department of Big Data and AI

Information Technologies Department

Department of Digital Expertise, Monitoring and Assessment

Department of Digital Transformation Co-ordination

Department of Digital Technologies, Procurement and Resource Management

Department of Cyber Security

Department of International Relations

Administrative Services Department

Department of Legal Consultancy.

Since its inception, the DTO has advanced several areas with the most visible achievement being the integration of fragmented services on türkiye.gov.tr, the e-Government Gateway. These efforts have largely focused on migrating transactions and integrating them according to a user-centred, life events-based approach under the “Digital Türkiye Version 1.1”. The DTO has also published the National AI Strategy with the Ministry of Industry and Technology (Sanayi ve Teknoloji Bakanlığı) and is working on strategies for public cloud and data.

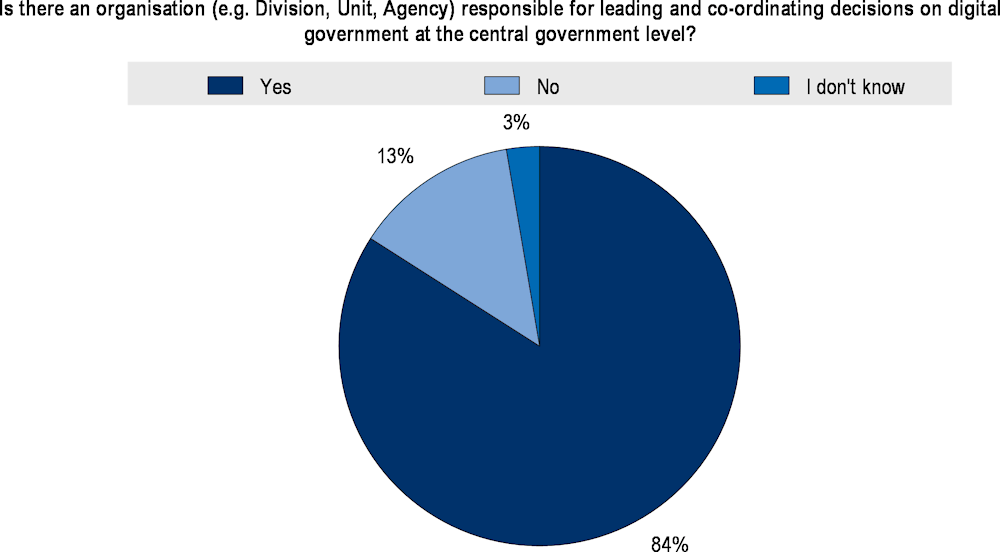

Despite its short history, the position of the DTO within the Presidency provides an adequate level of political support and ensures the ability to set a strategic vision and plan covering all policy sectors, the whole public sector and levels of government. During the review process, the OECD review team found that the leadership of the DTO is well recognised across the public sector. The survey conducted to support this review indicated 84% of participating institutions were aware of the existence of the leading organisation (see Figure 2.5) and the vast majority recognise the DTO’s leadership. During the fact-finding mission, a majority of interviewees recognised the strong presence of the DTO as the organisation-in-charge and indicated that they interact with the office on regular basis.

Figure 2.5. Recognition of an “Organisation-in-charge” of digital government in Türkiye

Note: Based on the responses of 113 institutions.

Source: OECD (2021[29]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q1.3.1.

As the organisation-in-charge, the DTO holds decision-making, co-ordination and advisory roles and responsibilities, yet at limited capacity. During the fact-finding interviews, several institutions indicated that the DTO decides on provision of services through the e-Government Gateway. However, any other major decisions related to digital initiatives still need an approval from the president.

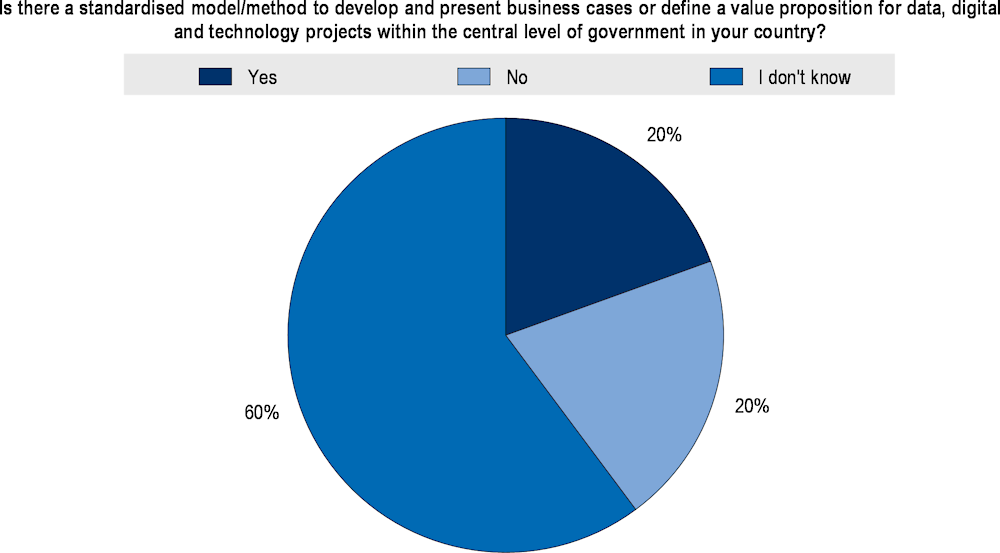

The OECD peer review team also found an insufficiently coherent approach towards establishing digital initiatives and turning strategic goals into action to lead the public sector towards a sustainable and holistic digital transformation. The survey and fact-finding interviews identified the lack of a standardised model/method and guidelines for public institutions to ensure coherent planning and implementation of digital government projects and initiatives. For instance, as seen in Figure 2.6, the survey run in the context of this review revealed that when asked about the availability or use of a standardised model/method to develop and present business cases or define a value proposition for data, digital and technology projects within the central level of government, the majority answered either "No" (20%, 23/113) or "I don't know" (60%, 68/113). Even though 22 institutions answered "Yes" they generally indicated the use of various methods obtained from different sources.

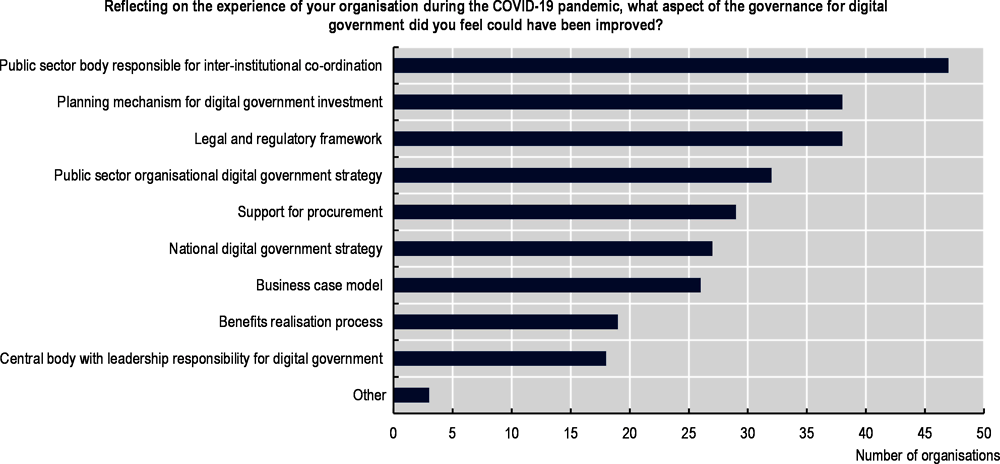

The same can be said for the DTO’s co-ordination responsibilities. Although there is high-level visibility and recognition of the DTO across the public sector, its role as the leading organisation can improve through greater engagement with relevant stakeholders. The survey results highlighted that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many institutions wished for more co-ordinated leadership from the DTO. Respondents also identified central leadership and inter-institutional co-ordination as areas of governance to be prioritised in preparation for any future crisis (see Figure 2.7). The survey also revealed that in relation to the governance of digital government, further efforts need to be invested to minimise bureaucracy, and to be more agile, innovative and collaborative (OECD, 2021[29]).

Overall, Türkiye has an influential organisation-in-charge to lead the digital transformation agenda across the public sector. It is, currently, supported by the highest leadership and with legal basis at the centre of the government. The DTO is in process of developing a new, overarching digital government strategy, which is a crucial opportunity for the organisation to reinforce the governance of digital government and its position as the organisation-in-charge to ensure a whole-of-government understanding and commitment for transitioning the government from e-government to digital government.

Figure 2.6. Use of a standardised model/methods to develop and present business cases

Note: Based on the responses of 113 institutions.

Source: OECD (2021[29]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q1.5.3.

Figure 2.7. Aspects of the governance for digital government to improve

Note: Based on the responses of 113 institutions.

Source: OECD (2021[29]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q1.8.2.

Nevertheless, there are challenges to overcome in building robust governance of digital government in Türkiye. As a newly established department based on a presidential decree, the DTO can benefit from strengthening its legitimacy and sustainability. The DTO's mandate can be further developed to cement its decision-making, co-ordinating and advisory roles and responsibilities in practice. In addition, it needs to create a more open and inclusive ecosystem for the various stakeholders from the public sector and at different levels of government to earn their trust and confidence.

Co-ordination and co-operation

Co-ordination and co-operation ensure coherency, consistency and effectiveness in public sector digital transformation. Effective institutional co-ordination allows governments to take a holistic approach to digital transformation with a sustainable impact on the society rather than fostering siloed institution-based thinking. All relevant stakeholders need to work together towards mutually set and agreed objectives and action plans to enjoy the full benefits of digital transformation. A co-operative and collaborative culture across the public sector can secure coherent policy design, development, implementation and monitoring. It can prevent possible policy gaps and foster an inclusive policy ecosystem. It can also help flourishing innovative practices in the public sector through exchanges of knowledge, experience and lessons learned.

Building upon diverse experiences and practices of OECD members and partner countries in line with the second pillar of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, the OECD Framework on the governance of digital government defines co-ordination and co-operation as a key dimension (OECD, 2014[2]; 2021[3]). It further looks into High-Level Co-ordination, and Organisational and Technical Co-operation. The former underlines institutional co-ordination at a high political and administrative level while the latter focuses on co-operation at more technical level.

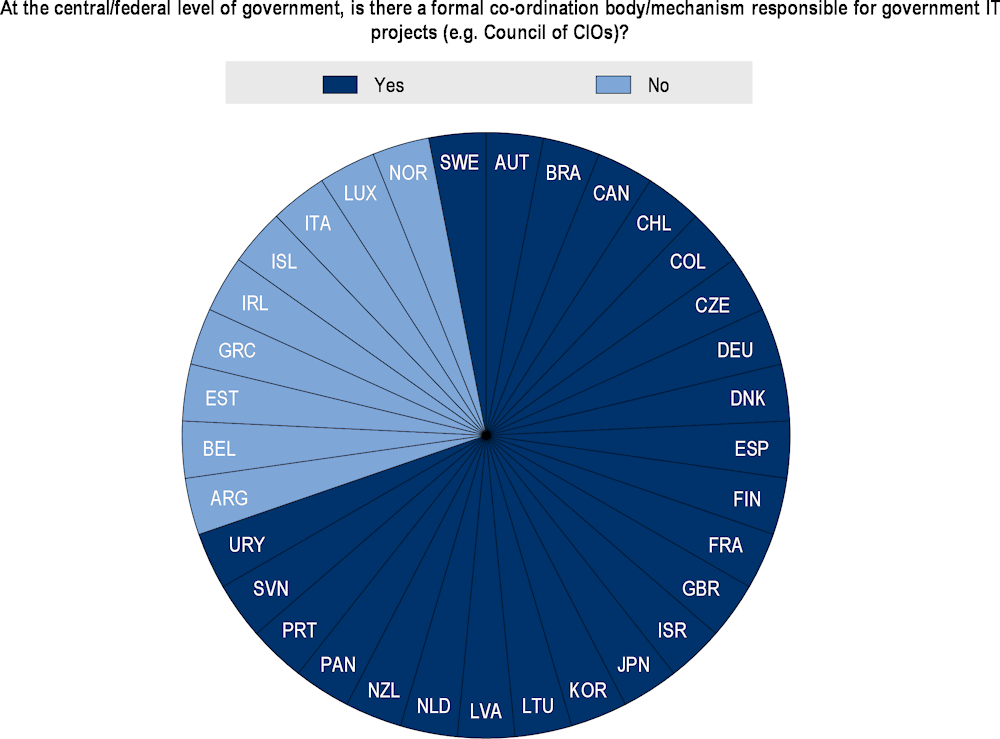

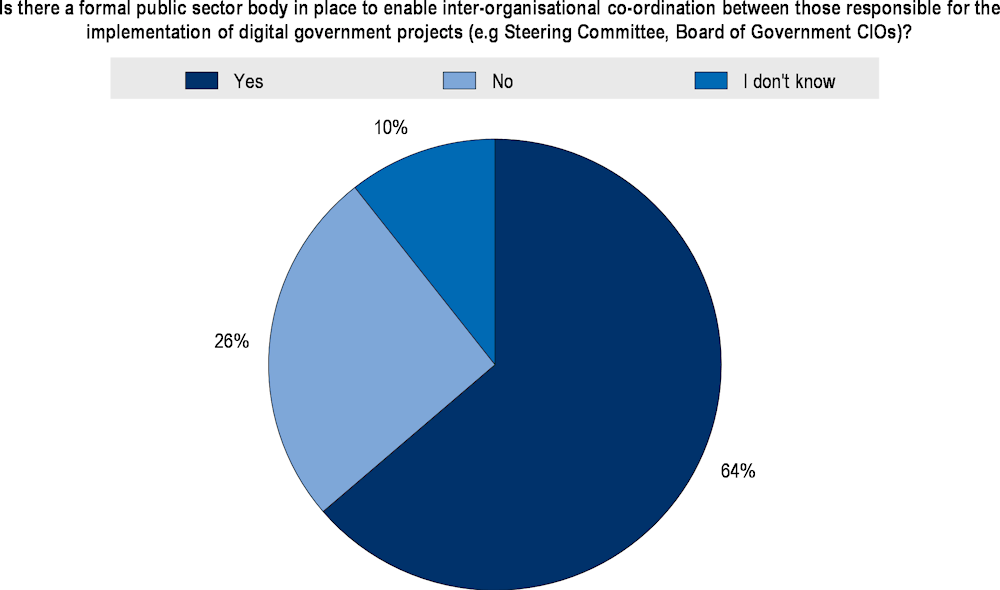

The OECD DGI 2019 highlights the importance of embedding a digital government co-ordination unit into the institutional models to ensure the leadership, co-ordination, necessary resources and legitimacy to interpret policies into actionable and concrete public services (OECD, 2020[1]). In the DGI 2019, most of the top performing countries were amongst the almost 70% indicating that they have a formal co-ordinating body/mechanism responsible for government IT projects (e.g. Council of Chief Information Officers, CIOs) (see Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. Existence of a public sector organisation leading and co-ordinating digital government in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Türkiye and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index.

Source: OECD (2020[1]), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en, Q. 59.

In Türkiye, the DTO organises the “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye Meeting” chaired by Vice President and attended by high-level representatives such as Vice Ministers or General Directors. The meeting was designed to minimise bureaucracy and red tape, and encourage collaboration and alignment on digital government priorities and initiatives. At the meeting, relevant stakeholders discuss common challenges and decide on possible solutions. The mechanism also involves the highest leadership in monitoring of progress against the decisions made at the meetings.

Among the majority of public sector stakeholders, the “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye Meeting” holds high legitimacy. Figure 2.9 shows that of the 113 public institutions that took part in the survey to support this review, 64% (72/113) acknowledged the existence of this inter-organisation co‑ordination mechanism. This important co-ordinating role was further highlighted during several interviews conducted by the OECD peer review team.

Although the “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye meeting” seems to enable co‑ordination among different stakeholders, a number of challenges remain for stronger and positive alignment, collaboration and co-ordination. First, greater effort could be made to raise awareness of this body across the public sector and secure a wider participation. Figure 2.9 indicates that 36% (41/113) of the institutions are not aware of the co-ordinating mechanism. In addition, only 27 organisations identified that they actually participate in the meeting.2 While it is important to find the necessary balance to cover a sample of public sector organisations it may be beneficial to have some core organisations with a permanent presence and a periodically rotating membership for others.

Figure 2.9. Existence of inter-organisational co-ordination for digital government projects

Note: Based on the responses of 113 institutions

Source: OECD (2021[29]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q. 1.3.5.

The seniority of representation during the “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye meeting” is valuable in creating binding expectations of delivery and implementation. However, the OECD peer review team apprehended that dynamics tend to be top-down with little evidence of two-way interaction discussions and could benefit from taking a more interactive and inclusive approach as well as including the insights of practitioners with a stronger grounding in the practicalities of digital transformation.

A co-operative and collaborative culture can further benefit from organisational and technical co‑operation. During the interviews, many stakeholders highlighted the need for inter-organisational collaboration and communication at a technical level to enable practitioners and technical stakeholders to co‑ordinate among themselves and promote institutional learning. The general lack of sharing data, information and good practices among organisations creates barriers in building trust, and ensuring coherent and sustainable implementation of digital initiatives. For instance, the majority of interviewees expressed their wish for a more integrated system and data pool; however, underlying mistrust among organisations is an impediment to advancing this process.

Overall, Türkiye, through the “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye Meeting”, has a solid foundation to build stronger and more effective co-ordination and co-operation. It would be worthwhile for the government to consider taking a few actionable steps to cement the processes that can ensure the coherence and sustainability of the digital transformation agenda across the public sector.

Formalising the “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye Meeting” can help it increase visibility and legitimacy. A clear mandate, list of participating representative and the frequency of the meeting will ensure regularity, continuity as well as wider participation. A monthly or quarterly meeting will allow regular monitoring and assessing of project implementation, contributing to turning high-level policies into concrete actions. In addition, forming working groups on key priority areas under the “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye Meeting” will provide a peer learning space where practitioners can exchange knowledge, experiences and good practices. This would spur innovative solutions to common issues through a bottom-up approach. This practice can also empower practitioners and public officials to take bigger ownership of policies and services. In the case of Slovenia for example, the Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration is a central mechanism for co-ordination across the public sector. The Council has a threefold structure that fosters co-operation and collaboration among stakeholders of different levels of mandates and political seniority (see Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. Slovenia’s Co-ordination Mechanism

Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration

The Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration, led by the Ministry of the Public Administration (MPA) and composed of secretaries of state of the most relevant ministries and other public institutions, is the government highest decision-making authority responsible for the digital government policy. The Council has a threefold structure that, with different levels of mandates and political seniority of the stakeholders involved, allows an important distribution of co-ordination responsibilities across the different sectors of government. Provided that the distinction of roles is clear, the existence of co-ordination at minister, secretary of state and director general levels is also an important mechanism to maintain the involvement, ownership and responsibility of different stakeholders and improve policy coherence and sustainability.

Strategic Council

Led by the Minister of Public Administration, the council is responsible for co-ordination and control of deployment of digital technologies in the public sector, review and approval of the strategic orientations, confirmation of action plans and other operational documents, and validation of projects of line ministries above a certain threshold.

Co-ordination Working Group

Led by the Secretary of State of the Ministry of Public Administration, this group is responsible for the preparation of proposals and action plans and for the co-ordination as well as compliance of digital government measures in line ministries and other public sector organisations.

Operational Working Group

Led by the director of the Directorate of Informatics, the Operational Working Group is responsible for the implementation of activities, the preparation and implementation of operational documents, and work reports based on action plans. It provides its consent to line ministries and government services for all projects and activities that result in the acquisition, maintenance, or development of IT equipment and solutions.

Source: OECD (2021[30]), Digital Government Review of Slovenia: Leading the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, https://doi.org/10.1787/954b0e74-en.

During the review process, the OECD review team found limited evidence of co-ordination and collaboration with local government and gaps in opportunities. In addition to ad hoc co-ordination on local governments’ integration to the e-Government Gateway, the Turkish government can further benefit from structured co-ordination and collaboration. Considering the administrative and geographical features of the country, the government can also consider organising a regular co-ordination meeting with digital leaders (e.g. Chief Digital Officer or equivalent). As the president of the DTO takes a role as the national Chief Digital Officer, it would be beneficial to co-ordinate meetings with local governments on a regular basis in co-operation with the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change who is in charge of overseeing the activities of the provinces. The regular meeting would help Türkiye steer more coherent digital transformation efforts evenly also at the local government level. The meeting will present opportunities to identify needs for local governments as well as to promote collaboration among them. In case of Korea, the Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization includes the establishment of a co‑ordination council composed of the heads of central administrative bodies, and local governments (see Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Korea’s Consultative Council of Intelligent Informatization Officers

Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization

Article 9 (Consultative Council of Intelligent Informatization Officers)

1. The heads of central administrative agencies and the heads of local governments (referring to the Special Metropolitan City Mayor, Metropolitan City Mayors, Special Self-Governing City Mayors, Do Governors, Special Self-Governing Province Governor) shall establish and operate the Consultative Council of Intelligent Informatization Officers (hereafter in this Article referred to as the “Consultative Council”) comprised of the Minister of Science and ICT, the Minister of the Interior and Safety and intelligent informatization officers for such purposes as efficiently promoting policy measures for the intelligent information society and intelligent informatization projects, exchanging necessary information, and consulting on relevant policy measures.

2. The Consultative Council shall be co-chaired by the Minister of Science and ICT and the Minister of the Interior and Safety.

3. Matters necessary concerning consultation and operation of the Consultative Council shall be prescribed by Presidential Decree.

Source: Government of the Republic of Korea (2020[31]), Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=54720&lang=ENG.

References

[28] Digital Transformation Office (2022), Organisational Chart, Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, https://cbddo.gov.tr/organizasyon-sema/.

[20] EC (2022), The eGovernment Benchmark 2022, European Commission, https://doi.org/10.2759/721646.

[10] EC (2022), Türkiye 2022 Report, Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, European Commission, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-10/T%C3%BCrkiye%20Report%202022.pdf.

[22] EC (2021), eGovernment Benchmark 2021 - Country Factsheets, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/redirection/document/80569.

[5] EC (2021), Turkey 2021 Report, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/system/files/2021-10/Turkey%202021%20report.PDF.

[18] EC (2020), International Digital Economy and Society Index 2020, European Commission, https://doi.org/10.2759/757411.

[31] Government of the Republic of Korea (2020), Framework Act on Intelligent Informatization, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=54720&lang=ENG.

[7] Government of Türkiye (2022), The Government Organization Central Records System, https://detsis.gov.tr/ (accessed on 22 November 2022).

[6] Ministry of Transport, Maritime Affairs and Communications (2016), 2016-2019 National e-Government Strategy and Action Plan, Republic of Türkiye, http://www.edevlet.gov.tr (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[16] OECD (2022), OECD Going Digital Toolkit - Türkiye (database), OECD, Paris, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/countries/tur.

[30] OECD (2021), Digital Government Review of Slovenia: Leading the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/954b0e74-en.

[27] OECD (2021), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye Lead/Co-ordinating Government Organisation Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[29] OECD (2021), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[17] OECD (2021), OECD Economic Surveys - Türkiye - Executive Summary, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/economy/surveys/TURKEY-2021-OECD-economic-survey-executive-summary.pdf.

[3] OECD (2021), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

[14] OECD (2021), “Turkey”, in Economic Policy Reforms 2021: Going for Growth: Shaping a Vibrant Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a5bfe33e-en.

[1] OECD (2020), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 03, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

[8] OECD (2019), Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability, OECD/LEGAL/0445, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0445.

[11] OECD (2019), The Principles of Public Administration - Türkiye, OECD, Paris, https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Monitoring-Report-2019-Turkey.pdf.

[9] OECD (2017), Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, OECD/LEGAL/0435, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0435.

[2] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD/LEGAL/0406, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406.

[19] Presidency of Strategy and Budget (2019), Eleventh Development Plan (2019-2023), Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye.

[26] Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2019), Presidential Decree No. 48, https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2019/10/20191024-1.pdf.

[25] Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2018), Presidential Decree No. 1, https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/19.5.1.pdf.

[4] TÜİK (2021), The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2021, Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu (Turkish Statistical Institute), https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=The-Results-of-Address-Based-Population-Registration-System-2021-45500&dil=2 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

[24] UK Central Digital and Data Office (2023), About Us, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/central-digital-and-data-office/about (accessed on 31 January 2023).

[21] UN (2022), E-Government Survey 2022: The Future of Digital Government, United Nations, https://desapublications.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2022-09/Web%20version%20E-Government%202022.pdf.

[13] UNDP (2020), Human Development Report 2020 - The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene, United Nations Development Programme, https://www.tr.undp.org/content/turkey/en/home/library/human_development/hdr-2020.html.

[15] UNDP (2020), “The next frontier: Human development and the Anthropocene – Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report – Türkiye”, United Nations Development Programme, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/tr/UNDP-TR-BRIEFING-NOTE-TURKEY-EN.pdf.

[23] World Bank (2022), The World Bank Data Catalog - GovTech Dataset, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0037889/govtech-dataset.

[12] World Bank (2022), The World Bank in Türkiye, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/overview#1.

Notes

← 1. Data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), National Currency to US Dollar Exchange Rate: Average of Daily Rates for Türkiye; monthly based from 1 June 2021 (7.3972 USD/TRY) to 1 June 2022 (16.99244 USD/TRY).

← 2. OECD (2021[29]), Question 1.3.6: “Does your organisation participate as a member of such co-ordination body?”.