This chapter is structured around the three pillars of the OECD Framework for Digital Government Talent and Skills necessary to conduct digital transformation. It will first explore the policy efforts implemented or considered by the government of Türkiye’s digital strategy in terms of how the public sector is attempting to establish a digital-enabling work environment, acquiring digital skills and implementing activities to maintain a digital workforce. Based on this analysis, this chapter will then suggest actions that can be taken to help secure the presence of the needed digital talent and skills to contribute to their digital transformation journey.

Digital Government Review of Türkiye

4. Digital talent for a transformational public sector

Abstract

Introduction

In light of the digital transformation of society, the way people communicate, work, learn and interact with each other has drastically changed. This digital era urges governments to equip the public sector talents with the necessary digital skills that enable them to navigate, lead and implement digital government strategies. To do this, across OECD member and non-member countries, governments are increasingly modifying their work environment, introducing digital user skills and offering attractive retention plans to preserve their talents and engage in a successful digital transformation journey.

In addition to this, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the interest of governments in the shift from e-government to digital government across OECD member and non-member countries. As many governments were forced to adapt to new ways of working as well as operating remotely overnight, it is crucial that the public sector workforce is well-prepared and qualified to thrive in a digital work environment. Therefore, there is a pressing need to prioritise cross-cutting policy actions to build further capacities and target shortages to address change and maintain high quality of services. According to the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), digital government transformation relies on various building blocks to foster the necessary collaboration and co-ordination across governmental entities. One of them is the need for public sectors to be equipped, not only with the right technology but also with the right working environment, the right skills and the right talents to unlock the potential of digital technologies and data to better meet citizen needs and build public trust.

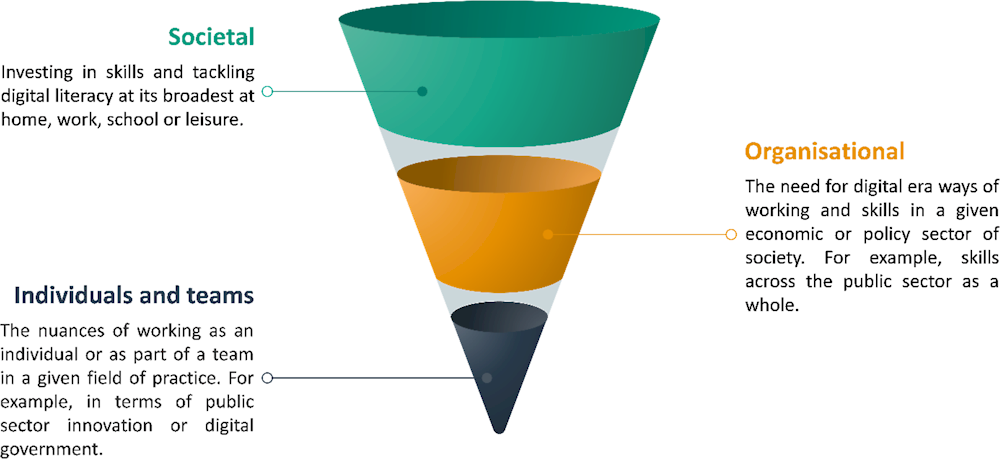

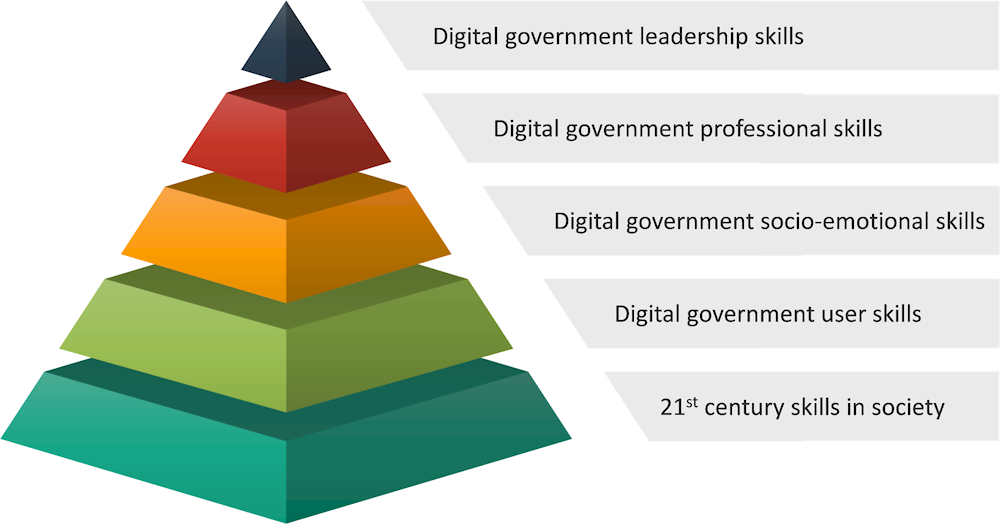

Since data and digital technologies play an increasingly significant role in our daily interactions, they have created a consequent need for wider and deeper understanding as appropriate to different contexts. This includes skills at the societal, organisational, and individual and team levels (OECD, 2021[2]). Skills at a societal level refers to digital literacy and the ability to use digital tools in our daily life; skills at organisational level relates to sector specific needs, and skills at the level of individuals and teams applies to the competencies needed to fulfil day-to-day roles in a particular job or field of expertise (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. From societal, to organisational, to individual and team skills

Source: OECD (2021[2]), “The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en.

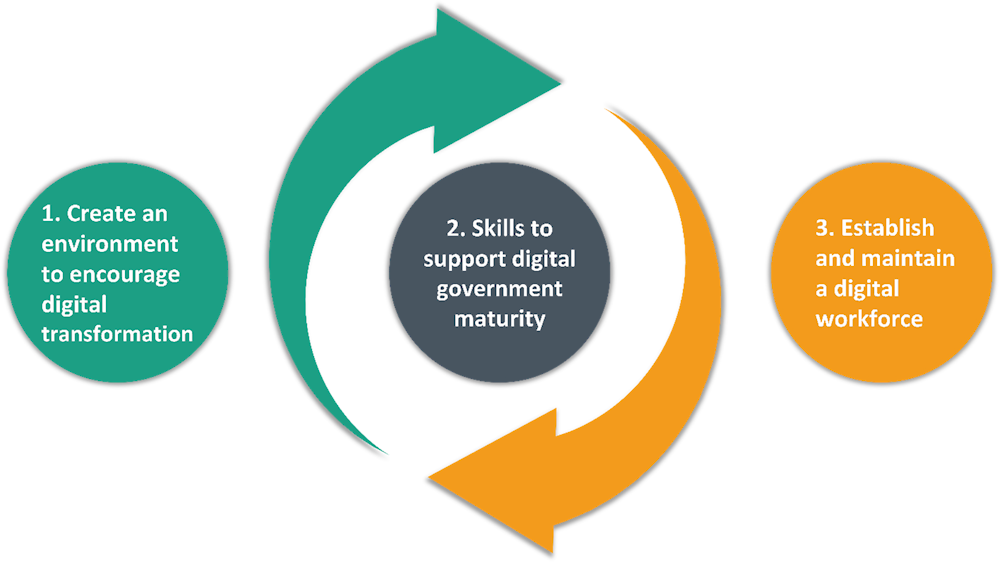

The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector (Figure 4.2) aims to support governments in developing a public sector workforce that can respond to the wider challenge of achieving digital government maturity (OECD, 2021[2]). The framework is composed of three pillars:

The first pillar addresses the environment of public servants working on digital government and establishes the right circumstances to unleash the digital workforce’s potential to conduct a successful digital transformation. This focus not only highlights how governments should appraise their leadership, organisational structures, learning culture and ways of working but also shows how conducive the workplace environment is for a digital workforce from a leadership, organisational and cultural point of view.

The second pillar dives into the necessary skills for a digital government. This part locates the skills for a digital government in the broader context of 21st century skills before looking at four additional areas of skills required for a digital government: user skills, socio-emotional skills, professional skills and leadership skills. It identifies the areas in an organisation’s model of skills and competency that need developing to support greater maturity of digital government.

The third pillar considers the specific actions and enabling activities required to build and maintain a workforce that encompasses the skills for a digital government. Recruitment methods, career planning, workplace mentoring, training and the role of the public sector need to be redesigned. This creates opportunities to improve approaches to particular areas and ensure that the workforce is, and remains, sufficiently digital.

Although the heart of this framework are digital skills, they can only flourish and benefit organisations if there is a well-established relationship between a working environment that provides the right conditions for public servants to train, develop and apply digital skills and the organisational systems that maintain a digital workforce (OECD, 2021[2]).

Figure 4.2. The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector

Source: OECD (2021[2]), “The OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en.

Since the government of Türkiye has high aspirations for successfully transforming from an e-government to a digital government, a simple upskilling of its workforce is no longer sufficient given the rapid evolution of technologies. Developing digital capability needs to go hand in hand with a work environment that provides digital talents with professional growth and encourages them to take the initiative, learn, and experiment. Equipping the public sector workforce in these areas will not only help to ensure the development of services that use technology effectively but in creating a user-centric culture, ensure that the quality of the outcomes from these services strengthens trust in government from citizens.

Based on the OECD Digital Government Talent and Skills Framework in the public sector, this chapter will explore the policy efforts implemented or considered by the government of Türkiye’s digital strategy in terms of how the public sector is attempting to establish a digital-enabling work environment, acquiring digital skills and implementing activities to maintain a digital workforce. Based on this analysis, the Review will suggest actions that can be taken to help secure the presence of the needed digital talent and skills to contribute to their digital transformation journey.

Building a digital environment in the Turkish public sector

Creating the necessary conditions that encourage the development of public sector digital talent and skills to move towards a digital government capable of responding to citizens’ evolving needs and expectations, is a challenge shared by many OECD countries. For this to happen, several elements are necessary including strong support from leaders, collaboration across entities, development of a digital culture, and flexible ways of working. If done well, the transition to a digital workplace will empower, encourage and inspire public servants to lead an internal cultural change that nurtures relationships with citizens and delivers better public services (OECD, 2021[2]).

Clear leadership vision

The preceding chapters have underlined the importance of government digital strategies backed by the leadership to set a vision for the digital transformation of the country in general. A critical element of this vision is inspiring the public sector workforce with a user-driven mindset and supporting them to develop the necessary skills to increase the level of digital government maturity.

In Türkiye, the Digital Transformation Office (Dijital Dönüşüm Ofisi, DTO) has been given a mandate, through Presidential Decree No. 1, of leading the digital transformation of the public sector and contributing to the digital transformation of the country by fostering co-operation with private sector organisations, universities and non-governmental organisations (Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2018[3]). In line with the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), the experience of several OECD member and non‑member countries shows that a clear vision articulated by strong leadership is highly important in promoting a change of working environment and establishing a work culture focused on digital practices.

During the mission to Türkiye and drawing on the survey carried out to support this review, the team identified a critical gap in the strategy underpinning the development of digital talent and skills and as a general reflection a shortage of initiatives to build a digitally-enabling environment. The Eleventh Development Plan (Presidency of Strategy and Budget, 2019[4]) contains a recognition of the importance of human resources and training, while the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi), one of four offices directly reporting to the President, has carried out concerted efforts to deliver various tools and initiatives to improve and enhance the capacity of public sector institutions (with a selection of initiatives in Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Selected initiatives of the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi)

Career Gate (Kariyer Kapısı)

Career Gate (Kariyer Kapısı) is the online platform used for applying to public sector jobs in Türkiye. The platform is integrated with the e-Government Gateway to access reliable data from central databases and make the application process faster and easier. Applicants can transfer their personal information, university graduation details, civil service examination results and other relevant information to their applications.

During the application process, candidate information is verified to ensure that only eligible candidates can apply. If an applicant fails to pass a particular phase, they receive an explanation through the platform. This transparency increases accountability in the recruitment process.

Once applications are submitted, the Career Gate (Kariyer Kapısı) also facilitates the assessment and placement stages through the same platform. This streamlines the recruitment process and makes it more efficient.

National Internship Programme

In order to support the transition between university and public sector employment, the National Internship Programme has been established. Through the Programme, university students are able to access internship opportunities through a digital platform that facilitates a transparent and traceable application and evaluation process. All processes, from application to placement, are conducted through the Career Gate.

Young talents are linked with public sector employers through talent pools that focus on particular fields, such as artificial intelligence. After expressing their preferences, the applicants are then matched with those institutions who have expressed a need.

In evaluating applications Competency Scores that reflect life-long performance are used rather than the immediate result of an exam. Employers send their offers based on scores without knowing the identity or gender of the students. This helps to reduce gender biases and ensure merit-based recruitment.

In 2022, more than 289 000 students applied to the Programme, and almost two out of three students that applied to the Programme received at least one internship offer and more than 100 000 students accepted the offers and started their internships.

National Talent Fairs

The Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi) also organises National Talent Fairs held in 11 regions of Türkiye. These career fairs give the opportunity across the country for people to discover the opportunities associated with a career in the public sector.

Talent TV (YTNK TV)

Talent TV (YTNK TV) is a training platform providing free support to young talents in their career development. As of August 2022, the platform has been viewed 17 million times and contains more than 100 different training packages, including the 14-week Career Planning Course designed for first-year university students to help them consider a range of career opportunities available in the public sector and elsewhere. The platform helps to increase awareness about potential professional paths and introduce early-career professions to different training programmes and qualifications.

Source: Information supplied by the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi).

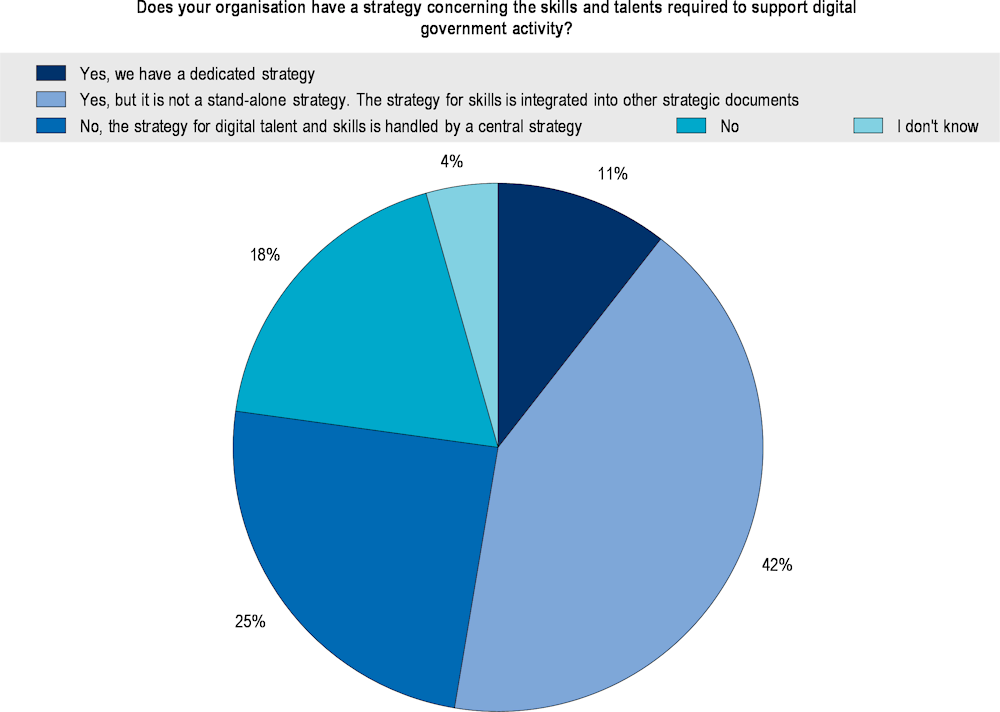

However, there is no dedicated strategic plan regarding digital talent and skills in the public sector to guide the practice across the public sector as a whole. Figure 4.3 shows that even though there is no dedicated strategy 25% of organisations believe the centre has developed one. Although just over half of the organisations recognise their organisational responsibility for digital talent and skills, only 11% of respondents (12/113) have a dedicated strategy with 42% of organisations (48/113) integrating their work on talent and skills into other strategic documents. This mixed strategic awareness in terms of public sector digital talent and skills suggests that this critical foundation for the digital transformation agenda needs further focus in Türkiye. This emphasises the importance for the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi) to take the lead in establishing a clear and dedicated talent and skills strategy at the centre to support all organisations in pursuing a common direction and developing the strategies they need to be effective in achieving digital maturity among their workforces.

Figure 4.3. Talent and skills strategy awareness at an organisational level to support digital government transformation in Türkiye

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q2.11.

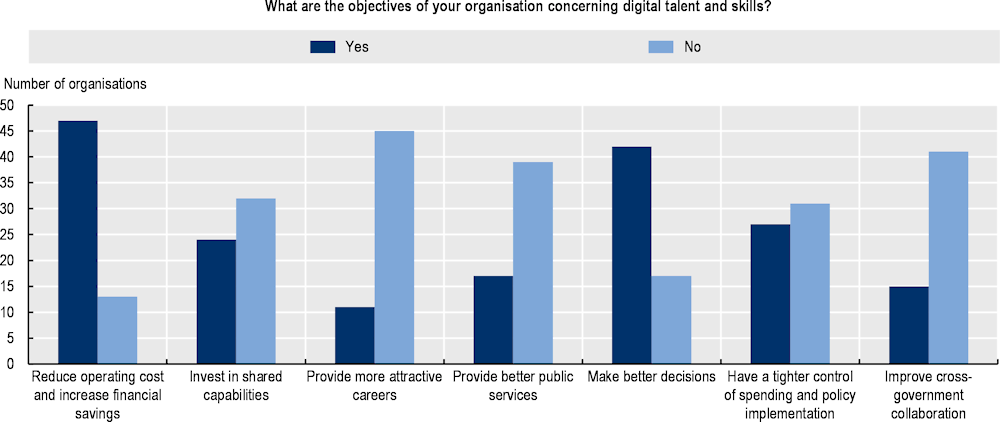

Among the 60 organisations that have developed their own organisational approaches to digital talent and skills, there was broad consensus about the objectives for doing so. As Figure 4.4 shows, a significant proportion of organisations identified reducing operating costs and increasing financial savings (78%, 47/60), and making better decisions (70%, 42/60), as the objectives for developing digital talent and skills. A much smaller number of organisations are currently looking to the development of digital talent and skills as a route to providing better public services, improving cross-government collaboration, or providing more attractive careers.

Figure 4.4. Objectives of setting a digital talent and skills strategy

Note: Based on 60 participants.

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Organisational structure

The digital transformation of society represents the latest revolution to which government must adapt. Responding to change inevitably means considering the design of organisational structures. Effecting the changes needed to deliver quality and user-centric services as part of a seamless digital transformation include establishing more horizontal and flatter hierarchies that distribute and decentralise decision making as well as designing job families, roles and their associated job descriptions with a focus on meeting user needs rather than implementing technology (OECD, 2021[2]).

Although türkiye.gov.tr, the e-Government Gateway, (further discussed in Chapters 5 and 6) is a great opportunity to work with public institutions across Türkiye, the review team noted that collaboration between entities is constrained by the rigidity of the organisational structure of the Turkish public sector. There was sense that organisations receive top-down decisions and implement strategies under the co‑ordination of the DTO without collaborating in their formulation. As discussed in Chapter 2, although it is common to witness layered government systems among countries, the Turkish Presidential system is particularly centralised and provides a hierarchical structure to the organisation of government, characterised by leaders making decisions and several organisational layers removed from operational practice. This may limit the feeling of ownership among public servants, as well as creating a more organisationally focused perspective and overlooking opportunities for collaboration and communication among different institutions.

An alternative approach would be to consider how organisational structures could be created with fewer layers and decision making responsibility distributed more evenly across teams. This is not with a view of pushing the responsibility for more things onto fewer people but to ensure that through a multi-disciplinary approach the delegation of responsibilities can be handled effectively and consistently. Minimising hierarchy-related pressures can make leaders more accessible and encourage public servants to own their work, as well as fostering more interaction and collaboration between individuals from different teams. As a concrete example, Australia looked at their centralised model and conducted the Australian Public Service Review (Box 4.2), which identified a more horizontal organisational structure as a mechanism to allow better and faster decision making by bringing together the right experts. In light of the rapid pace of digital transformation of government, public institutions need to move and adapt fast to meet society’s needs.

Box 4.2. The Australian Public Service Review

In May 2018 the Australian Government commissioned a review to ensure the Australian Public Service (APS) was fit for purpose. The process engaged with more than 11 000 individuals and organisations and over 400 consultations to conclude that service-wide transformation was needed to achieve better outcomes. This was not say that the APS was broken but that the status quo was insufficient to prepare for the changes and challenges anticipated in the next decade. Recommendation 32 was to:

Streamline management and adopt best-practice ways of working to reduce hierarchy, improve decision-making, and bring the right APS expertise and resources.

The implementation guidance called for management structures to have no more organisational layers than necessary in order to allow for decision-making at the lowest practical level with spans of control reflecting the type of work being managed, structures providing flexibility to respond to changes, and jobs classified according to work level.

Source: Commonwealth Government of Australia (2019[6]), Our Public Service, Our Future. Independent Review of the Australian Public Service, https://pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/independent-review-aps.pdf.

As well as establishing a flatter organisational structure and developing mechanisms to distribute decision making it is important to consider the nature of the roles that people perform and invest in creating more user-centric, iterative and collaborative job families and job descriptions. To design and deliver services in the digital age, it is necessary to revise existing roles and capabilities that align with the technology focus of earlier ideas around e-government and ensure that they incorporate the opportunities from focusing on needs of users. To illustrate this, the United Kingdom’s Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT) Profession Capability Framework has formally recognised a series of job families needed to effectively lead digital, data and technology projects and improve consistency in both job roles and the definition of the associated skills, with the example of Service Designer discussed in Box 4.3.

Box 4.3. United Kingdom DDaT Profession Capability Framework: Service designer

The Capability Framework describes the service designer profession, including:

introduction to the role and communicating what it involves and the skills it requires.

a description of the career path, and associated skills, from associate to head of profession.

Example of Associate service designer job description:

As a trainee in an entry-level position, working under supervision, you will need design aptitude, potential and an understanding of the role. Skills needed for this role level:

Agile working. You can show an awareness of Agile methodology and the ways to apply the principles in practice. You can take an open-minded approach. You can explain why iteration is important. You can iterate quickly. (Skill level: awareness).

Communicating between the technical and non-technical. You can show an awareness of the need to translate technical concepts into non-technical language. You can understand what communication is required with internal and external stakeholders. (Skill level: awareness).

Community collaboration. You can understand the work of others and the importance of team dynamics, collaboration and feedback. (Skill level: awareness).

Digital perspective. You can demonstrate an awareness of design, technology and data principles. You can demonstrate engagement with trends in design and can et relevant priorities. You can understand the Internet and the range of available technology choices. (Skill level: awareness).

Evidence- and context-based design. You can show an awareness of the value of evidence-based design and that design is a process. (Skill level: awareness).

Leadership and guidance. You can show commitment to agreed good practice for the team, teaching new starters and challenging substandard work by peers. You can recommend decisions and describe the reasoning behind them. You can identify and articulate technical disputes between direct peers and local stakeholders. You can show an understanding of the importance of team dynamics, collaboration and feedback. (Skill level: awareness).

Managing decisions and risks. You can identify technical disputes and describe them in ways that are relevant both to direct peers and to local stakeholders. You can work collaboratively while recommending decisions and the reasoning behind them. (Skill level: awareness).

Prototyping. You know about prototyping and can explain why and when to use it. You can understand how to work in an open and collaborative environment (by pair working, for example). (Skill level: awareness).

Prototyping in code. You can demonstrate a basic knowledge of how the Internet works. You can use tools and change text. You can edit existing code and reuse it. (Skill level: awareness).

Strategic thinking. You can explain the strategic context of your work and why it is important. You can support strategic planning in an administrative capacity. (Skill level: awareness).

User focus. You can identify and engage with users or stakeholders to collate user needs evidence. You can understand and define research that fits user needs. You can use quantitative and qualitative data about users to turn user focus into outcomes. (Skill level: working).

Source: UK Central Digital and Data Office (2020[7]), Service Designer, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/service-designer.

Learning culture

It is equally fundamental for a digital-enabling work environment to acknowledge that learning happens at all levels of the organisation as this generates opportunities for public servants to increase experimentations towards building trustworthy digital services in safe space. Leaders who are able to set a solid learning culture, support a life-long learning mindset and recognise the value of learning through testing, iterating and failing will pave the way for innovation in the public sector (OECD, 2021[2]).

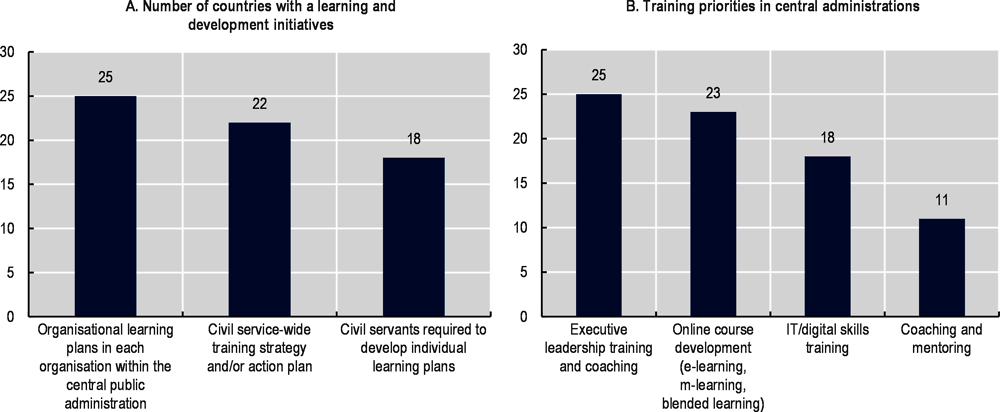

As stated in the OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability (OECD, 2019[8]), governments should create a learning culture and environment that supports public servants in their skills development. According to the OECD Survey on Strategic Human Resource Management, many OECD countries seemed to value learning and development initiatives. In 25 countries out of 36 (70%) organisational learning plans are in place in each organisation within the central public administration (Figure 4.5) (OECD, 2019[9]). Such a strategic move from leaders recognises the importance of investing in the skills of public servants to thrive and provides a model to emulate in terms of emphasising digital skills.

Figure 4.5. Learning and development initiatives and training priorities in public administrations, 2019

Note: The figure shows data for the total respondents of 36 OECD countries.

Source: OECD (2019[9]), “OECD Survey on Strategic Human Resource Management”.

The work environment within an organisation not only sets the strategic direction but helps to ensure the conditions under which strategies can be put into practice. The COVID-19 pandemic reflects a moment of crisis during which the need for a greater digital competence among the public sector workforce came to the fore. Throughout the survey supporting this review and the fact-finding interviews, many organisations noted that the Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı) (see Box 4.4) had been an important initiative to provide online training and resources to help the workforce navigate the sudden change to digital. However, the OECD team noticed that there is a lack of a formal training and learning structure dedicated specifically to digital skills such as the approaches evident in the experiences of Canada, Italy, Slovenia and the United Kingdom to build a learning culture discussed in Box 4.5.

Box 4.4. The Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı)

Under the co-ordination of the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi), the Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı) prepare newly hired public employees and employees in general for the public sector. The portal contains training contents to increase their awareness of the requirement of digital transformation in public service and enhance their digital skills.

The Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı) is the training platform of Türkiye and is used by over 1 500 public institutions and organisations. The platform provides access to 30 000 different training materials for all public employees regardless of their title, role, institution, or age. In that sense, all public employees, from newly hired employees to employees who are about to retire, can benefit from the platform freely.

Also, various training activities are carried out to develop digital literacy and 21st-century skills in Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı) for different target groups. Therefore, employees who want to improve their skills in several fields and refresh their knowledge, even if they do not work in the relevant field, can participate in available training content and benefit from these training activities. In that sense, employees can arrange their learning plans without being dependent on the training assignment of their institutions.

Source: Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2021[10]), The Distance Learning Gate, https://www.cbiko.gov.tr/cms-uploads/2021/11/distance-learning-gate.pdf.

Box 4.5. Building learning cultures within governments

Canada’s Digital Academy

The Canada School of Public Service (CSPS) Digital Academy was created in 2018 with the objective to teach Canada's federal public servants the digital skills, approaches, and mindset needed to transform public services in today's digital age.

As part of its activities, the Academy brings together partners from different spheres, including government, academia and the private sector, with the focus on collaboration and the sharing of knowledge and experience. The Academy offers both general and more specialised learning opportunities, in the classroom and online, for public servants at all levels.

Source: Government of Canada (2020[11]), Digital Academy, https://www.csps-efpc.gc.ca/About_us/Business_lines/digitalacademy-eng.aspx.

Italy’s Digital Skills for the Public Administration

"Digital Skills for the Public Administration" is an initiative promoted by the Department of Public Administration within the National Operational Programme "Governance and Institutional Capacity 2014-2020". It aims to equip all public employees with common digital skills, by implementing a structured gap detection in digital skills and targeted and effective training.

Considering the role played in supporting the digital transition of the Public Administration, the Department of Public Administration, aims to:

Establish a common base for technological and innovation knowledge and skills among public employees.

Strengthen the institutional capacity for an efficient Public Administration through training on digital skills, delivered mainly in e-learning mode and customised based on a structured and homogeneous survey of the actual training needs.

Develop digital knowledge of public employees to implement the principles of digital citizenship, eGovernment initiatives and open government.

Promote the mapping of skills in administrations at different government levels, also in order to promote more effective HR management policies.

The initiative is based on three main components:

1. The syllabus, that describes the set of knowledge and skills, organised by thematic areas and proficiency levels, which characterise the minimum set of digital skills that each public employee should have in order to be able to work easily in an increasingly digital Public Administration.

2. The web platform, that provides tools for skills verification tests and assessment of post-training learning based on the syllabus, as well as for the selection of the most appropriate training modules to meet the knowledge requirements identified; the platform also supports administrations in planning, managing and monitoring effective skills development paths in line with their organizational needs.

3. The catalogue, that collects training modules on the competences areas described in the syllabus, aimed at filling the digital skills shortcomings detected during the self-test phase.

Source: Provided by the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on Digital Talent and Skills.

Slovenian “Innovation Training in Public Administration”

In Slovenia, the Ministry of Public Administration runs "Innovation Training in Public Administration". This training aims to change the approach to workflow, problem solving and designing better solutions through effective communication. The programme is actively changing the administrative culture to implement higher quality state functions and digital services. The programme is performed in person and remotely.

Objectives of implementing the programme are:

Raising awareness of the importance of gaining new skills and knowledge in terms of alternative ways of work to enable a more agile and efficient response to the demands of the environment.

To acquire competence for creative tackling of challenges and designing solutions using different methods and approaches focusing on the user.

To acquire competence in different ways of communicating (more effective presentation of ideas, results, etc.) and in managing group communication processes.

Source: Slovenia Ministry of Public Administration (2020[12]), Inovativen.si, https://www.gov.si/zbirke/projekti-in-programi/inovativnost-v-javni-upravi-inovativen-si/.

United Kingdom’s Government Digital Service Academy

The GDS Academy aimed to give public sector professionals the necessary skills, awareness and knowledge to build the best possible public services. Originally founded by the Department for Work and Pensions in 2014, it transferred to GDS in 2017 before being closed in 2022. During its existence, over 10 000 public servants were trained, including 1 000 from local authorities. The Academy was also a model for foreign governments.

Source: Provided by the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on Digital Talent and Skills.

Very few institutions in Türkiye spoke of a digital culture within their workforces or of the opportunity for public servants to experiment, learn and grow on their own. In other words, the current practice may reduce the workforce’s capability to innovate, learn and develop the sense of empowerment. Since experimentation gets people to work in an agile way and take more risks, it not only empowers digital talents and increases job satisfaction, but also enables higher productivity as they test, acquire knowledge and adapt fast to meet the constant change of citizens’ needs. Further initiatives from leaders across the different public sector institutions would set the right vision and working conditions for the digital transformation. This would create a work environment that encourages talents to build digital skills and facilitates the development of a digital culture.

To cultivate a learning culture within the Turkish public sector, which is a cornerstone for digital transformation, the government may consider creating a work environment that fosters digital experimentation allowing its digital workforce to test, iterate and fail, while feeling empowered to experiment without judgement. This could be done by increasing the diversity of education and live training held through the Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı) (see Box 4.4) to encourage higher participation from the workforce. Leaders could also support its digital talents in the application of new digital skills by offering a safe space to learn and incentivising managers to help the change of mindset by putting the human in the centre of the strategy.

Ways of working

Ways of working are fundamental to digital government maturity with the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrating the need to quickly be able to respond to a crisis and operate in a new environment where digital became the enforced default for citizens and staff alike. Therefore, the ways institutions operate are a key determinant for its digital maturity: the more flexible and agile an organisation is, the more digitally matured it is.

The OECD Government at a Glance 2021 shows that, in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, most OECD members and non-members had existing tools and policies to enable remote working: 91% (31 out of 34) of countries reported using existing communication channels to keep staff informed, 65% (22 out of 34) had the IT infrastructure in place to enable remote working and 58% (20 out of 34) had previously established remote working regulations and policies (OECD, 2021[13]). However, 68% (23 out of 34) of countries had to upgrade their video conferencing and other communication tools to shift from occasional to full-time remote working and 24% (8 out of 34) changed recruitment and staffing regulations and policies to meet demand and allow internal mobility. Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic demanded a more flexible and agile working environment and acted as a catalyst for identifying areas of improvement and developing an effective response (OECD, 2021[13]).

In Türkiye, both the necessary IT infrastructure and communications channels to keep staff informed were well established ahead of the pandemic, enabling the country to move and adapt quickly in the face of the crisis (OECD, 2021[13]). Nevertheless, like many other countries, Türkiye invested in their video conferencing and other communication tools to better enable the sustained period of teleworking as well as enhancing existing platforms such as those to support the justice system where the full process can now take place virtually, including for judges (OECD, 2021[13]). As the pandemic progressed, the initial regulation of remote working, rotating work and administrative leave was addressed by Presidential Circular No. 2020/4 before the Remote Working Regulation enshrined these principles in law in March 2021 (Nadworny, 2021[14]). However, the OECD peer review team still observed a shortage of initiatives towards building flexibility into the working environment during the fact-finding mission. Some organisations reported the lack of flexibility in terms of working remotely and expressed their wish to work in a hybrid environment. The country has introduced regulations and can rely on the necessary technological foundations but there is a gap in terms of organisational culture in applying these ideas in practice. Better communications of these principles that aim to make the Turkish public sector more flexible could benefit the government in improving its workplace.

Although investing in adequate tools and technologies is important, establishing flexible working policies and workspace is equally essential. Türkiye could create a more flexible workplace by focusing on communicating and implementing the regulations and policies established during the COVID-19 pandemic. These measures would reflect the agile and user-centred working methodologies where digital talents are empowered to choose where to work from, when and how they want to work, which increase motivation, job satisfaction, productivity and trust. To name a few countries, Ireland, Spain and Uruguay have accelerated the implementation of flexible working policies once the pandemic hit. They have kept remote working practices, as well as the use of online collaborative tools and platforms available for the public servants. They also made the most out of online trainings to enable public organisations to quickly adopt this new way of working. Consequently, these countries have established a more flexible workplace, where a digital workforce can apply new digital skills, and work in a place and at a time that fit them best (OECD, 2021[2]).

To build a suitable workplace that welcomes digital transformation, the Government of Türkiye could ensure that its leadership not only communicates a strong vision and champions the benefits of a digital government, but also adopts a horizontal organisation structure to allow faster and better decision-making. Additionally, establishing a learning culture that encourages testing, learning and failing, with more flexible working policies could enable the digital talents to own their work and innovate to constantly provide high quality public services.

Equipping digital talents with digital skills in the public sector

The evolving nature of work in the public sector makes it crucial to identify, train and equip public servants with the right mindset, digital skills and tools to lead a successful digital transformation. Aligned with the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), many OECD member and non-member countries demonstrated a willingness to achieve further digital maturity also by prioritising institutional capacities into building a digitally skilled workforce. In 2021, the Government at a Glance publication found that 26 out of 37 OECD (70%) countries have developed online on-boarding and training tools to train staff quickly in a remote environment, which is an increase from 61% in 2019 (OECD, 2021[13]; 2019[15]).

In Türkiye, the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi), provides some general training and information to all newly hired public servants through the Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı) to ensure that they start their jobs with foundational digital skills (see Box 4.4). In responding to the needs of their users, some institutions have access to capable in-house teams, while others are more reliant on the team at Türksat responsible for the e-Government Gateway. Where in-house training schemes have been developed with a focus on specific skills, such as software development, organisations can draw on impressive in-house capability to deliver technical solutions and operating in line with national strategies. Elsewhere, Türksat provides the specific capabilities as an outsourced provider, overseen by the DTO, to ensure the operation of the e-Government Gateway. The Türksat team develops new services according to needs and objectives set by the DTO. Every December, the team receives training focusing on responding to the evolving needs of society.

Based on the fact finding mission and the survey conducted to support this review, the public sector of Türkiye is confident in its level of access to the necessary human resources, skills and capacity to achieve its digital government ambitions. Nevertheless, as reflected in the other chapters of this review, there are areas for improvement and so, as efforts to develop in-house and national training schemes continue, it would be valuable to reflect the needs in the areas covered by the OECD Framework for Digital Government Talent and Skills in the Public Sector and shown in Figure 4.6. Skills to support digital government maturity (OECD, 2021[2]).

21st century skills in Türkiye

Society as a whole must be capable and equipped with the necessary digital, cognitive and socio-emotional skills to thrive in the digital age. This is core for all to have basic confidence in using digital tools and technologies. All efforts to establish a digitally enabled state rely on this grounding. Therefore, the 21st century skills (see Box 4.6) expected of public servants should be consistent with the minimum expectations of equipping all members of society to benefit fully from the digital age (OECD, 2021[2]).

Figure 4.6. Skills to support digital government maturity

Source: OECD (2021[2]), “The OECD Framework for digital talent and skills in the public sector”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en.

Box 4.6. The definition of 21st century skills

Skills-related policies that successfully equip people with a broad mix of skills will ensure the technological revolution improves the lives of all. It is particularly important to ensure that the promise of digital transformation does not widen existing inequalities or create new ones as some jobs disappear and some skills become outmoded (OECD, 2019[16]). Therefore, addressing the skills gap in society is critical to avoid exacerbating, or creating, inequality in terms of access to the benefits of digital transformation whether through socio-economic, demographic, generational, geographic, educational or infrastructural challenges.

The ambition must be for two things to be achieved. Firstly, that over time society as a whole becomes more capable and equipped with the necessary breadth of skills to thrive in the digital age. Secondly, that alongside a recognition of the need to upskill to a particular benchmark there would be efforts to encourage a continuous, and life-long approach to these skills which ensures society remains equipped on an ongoing basis. As benefits are seen in terms of the digital economy, benefits will also flow into the public sector as its own workforce demonstrates their own foundational digital skills.

At its most basic, the notion of digital user skills indicates an ability to use Internet connected devices. The baseline for what constitutes ‘an ability to use’ is fluid and it is therefore important to avoid overly simplistic framings and instead reflecting changing habits, purposes and needs. Nevertheless, it is important to find a definition that points towards realistically deriving benefits from digital technologies. One model for understanding and defining digital literacy and digital skills in society is the European Digital Competence Framework 2.0 (DigComp) which looks at five areas of digital competencies (EC, n.d.[17]).

For example in Slovenia, the Administration Academy at the Ministry of Public Administration launched a new “Digital literacy training programme for public servants” in 2019. This programme follows the DigComp Framework for Citizens with 21 competences in five areas. The objective of the training programme is to enable civil servants to use information and communication technologies in a creative, safe and critical way. This follows from the 2018 launch of a “Data management” programme which consists of different modules tailored for different focus groups such as managers, analysts and IT experts with varying degrees of knowledge. The objective of the training is to foster data literacy and use of modern technologies for better decision making. Both programmes could be performed either in person or remotely.

Source: OECD (2021[2]), “The OECD Framework for digital talent and skills in the public sector”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4e7c3f58-en; OECD (2019[16]), OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World, https://doi.org/10.1787/df80bc12-en; EC (n.d.[17]), The Digital Competence Framework 2.0, https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/digcomp/digital-competence-framework (accessed on 16 December 2020).

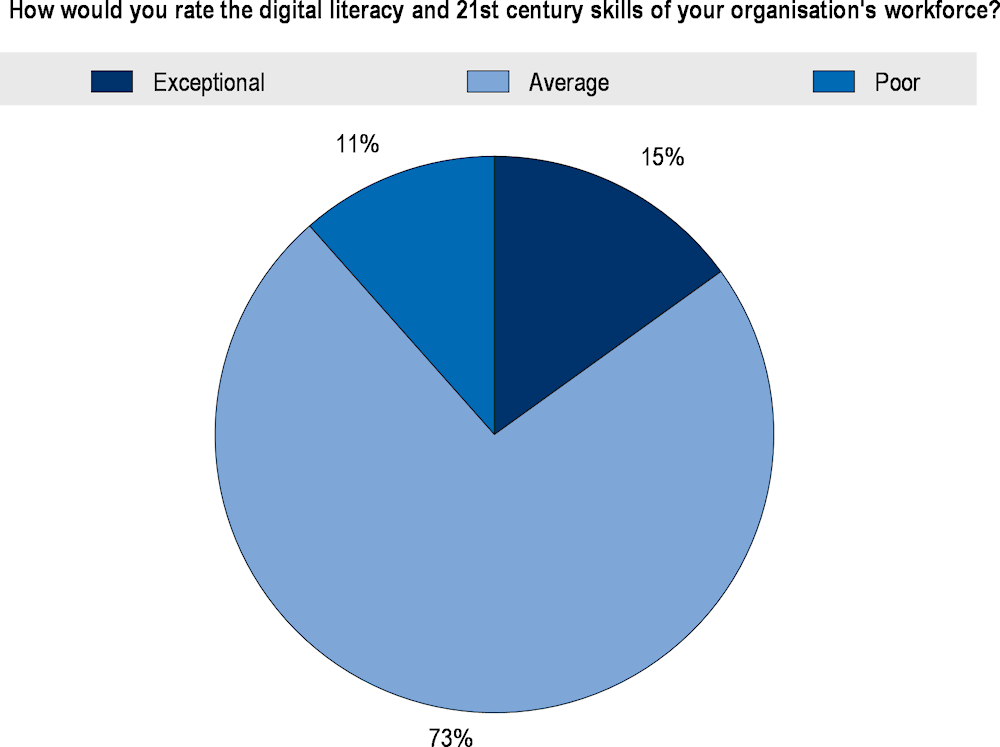

From the survey conducted to support this review, the OECD observed that a significant majority of organisations considered the digital literacy and 21st century skills to be at least average with Figure 4.7. Public servants’ Digital literacy and 21st century skills in Türkiye showing that 73% (82/112) of organisations rate theirs as average and 15% (17/112) as exceptional. In addition, a majority identified the use of in-service training and workshops to maximise the digital awareness of their workforce. Some institutions then separately work with international organisations such as the World Bank, or local stakeholders such as Türksat in the integration of technology and the subsequent development of the services they provide. However, there were concerns about the levels of digital literacy and 21st century skills at the level of municipal and sub-national government.

Figure 4.7. Public servants’ Digital literacy and 21st century skills in Türkiye

Note: Based on 112 participants.

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

To ensure high levels of inclusion, it is commonly recognised that tools and services need to be designed in ways that work for all members of society, this includes those who may have accessibility needs as well as those with lower levels of competency and skill. Inclusively designed public services respond to these needs and help the public to access them smoothly in line with any assistive technologies or suitable support without requiring special training. The same consideration should be given for the needs of the public sector workforce, in both urban and rural areas. This means not only considering the design of services on an end to end basis, to include the internal user experience (as discussed in Chapter 5) but to ensure public servants are getting the necessary equipping in the requisite skills or support to thrive in the 21st century at home, and at work.

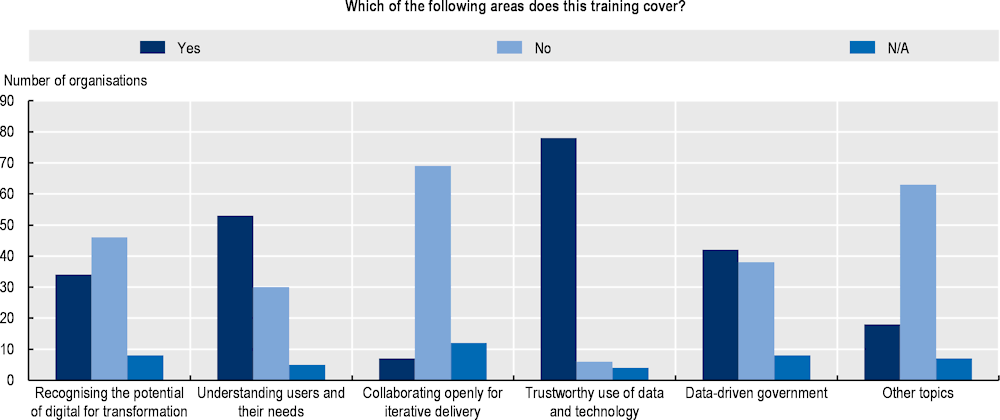

Digital government user skills

Digital government user skills are the baseline skills that all public servants need to have to support digital government maturity, such as the awareness of the potential for digital, data and technology. During the mission to Türkiye, the OECD peer review team noted a lack of training in digital government user skills for all public servants. In spite of the fact that many institutions highlighted their effective public sector workforce and showed an impressive in-house capability to build services, their skills are tailored to e‑government services instead of digital government services. This means that it needs a focus on digital government user skills, which are five core skills that all public servants must have to be effective in supporting a digitally enabled state regardless of their role or tier of government (OECD, 2021[2]):

Recognising the potential of digital for transformation.

Understanding users and their needs.

Collaborating openly for iterative delivery.

Trustworthy use of data and technology.

Data-driven government.

The results of the survey supporting this review, shown in Figure 4.8. Digital Government User Skills Trainings in Türkiye, show that in almost 90% (78 out of 88) of public sector organisations receiving trainings to conduct digital government activity, public servants in Türkiye receive training on “Trustworthy use of data and technology”, 60% (53 out of 88) on “Understanding users and their needs”, 48% (42 out of 88) on “Data-driven government”, 39% (34 out of 88) on “Recognising the potential of digital for transformation” and 8% (7 out of 88) on “Collaborating openly for iterative delivery”. The progress in some of these areas is encouraging but needs to be reinforced with more homogenous trainings in all five areas, particularly as part of the initial on boarding for new members of the workforce as these represent an additional layer to the expected baseline of digital literacy in general. To achieve digital transformation, governments need a workforce capable of grasping the opportunities that digital, data and technology offer and using them to improve government operations. Having this mindset in place, not only among digital government teams or ICT professions but across all organisations, is crucial to help re-think and re-design services in a way that meets citizens’ expectations. This is why ensuring that public servants are fully equipped with the five core areas of digital government users’ skills, as soon as they join the public sector, would highly benefit the Government of Türkiye.

Digital government socio-emotional skills

Successfully embedding a shift in the culture of government requires teams to be established that reflect a diversity of socio-emotional skills and their associated behaviours (OECD, 2021[2]). Unlike the digital government user skills discussed above, there should be no expectation for every public servant to become an expert in every socio-emotional skill. The focus should instead be on ensuring a balance of vision, analysis, diplomacy, agility and protection in the teams that work on designing and delivering government services.

Figure 4.8. Digital Government User Skills Trainings in Türkiye

Note: Based on 88 participants.

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

The value of having a mix of visionary, analytical, diplomatic, exploratory and protective talents helps teams to work together to identify coherent and holistic solutions. As this can help to generate a broad base for ideas and facilitate learning with and from each other, this is an essential ingredient in bringing together different professions within multi-disciplinary teams and is increasingly seen as a foundation for digital government success (OECD, 2021[2]). However, the OECD team noticed that there were a lack of initiatives to stimulate innovation and foster environments that would allow for creating these blended teams within public institutions in Türkiye. Critically, many participants shared that they did not have a model of working with multi-disciplinary teams in the public sector.

The different digital government socio-emotional skills are not expected to be reflected by every individual public servant but a healthy team is able to balance these perspectives to ensure diverse skills, expertise and personal backgrounds. Expanding efforts to encourage greater variety in the composition of teams and reflecting multiple disciplines and socio-emotional skills can not only support greater mobility of staff, but help staff to continuously learn from one another and contribute to different topics. This can help to increase motivation and job satisfaction among the workforce.

Digital government professional skills

One of the most important enablers for helping to achieve digital government maturity is establishing multi-disciplinary teams that bring together different professional backgrounds. This blend needs to reflect traditional disciplines alongside digital specialists. These include policy, legal and subject matter experts, commissioning and procurement, human resources, operations and customer services, and sociologists and psychologists. Digital professionals cover the disciplines of user-centred design, product, delivery, service ownership and data as well as digital era technology roles. This blend of skills is necessary to achieve the ambitions governments have for proactive and user-centred public services in the digital age. In terms of bridging the gap between digital professionals and those in more traditional roles, the Digital Government Index highlighted that training targeting public professionals remains relatively low among OECD members and non-members countries. In terms of this group, 28% of the responding countries offer training in data analytics, 30% in artificial intelligence, and 25% in usability and accessibility (OECD, 2020[18]). For successful digital government, training is needed not only for digital professionals but for those in adjacent roles who make a valuable contribution to digital transformation within a country.

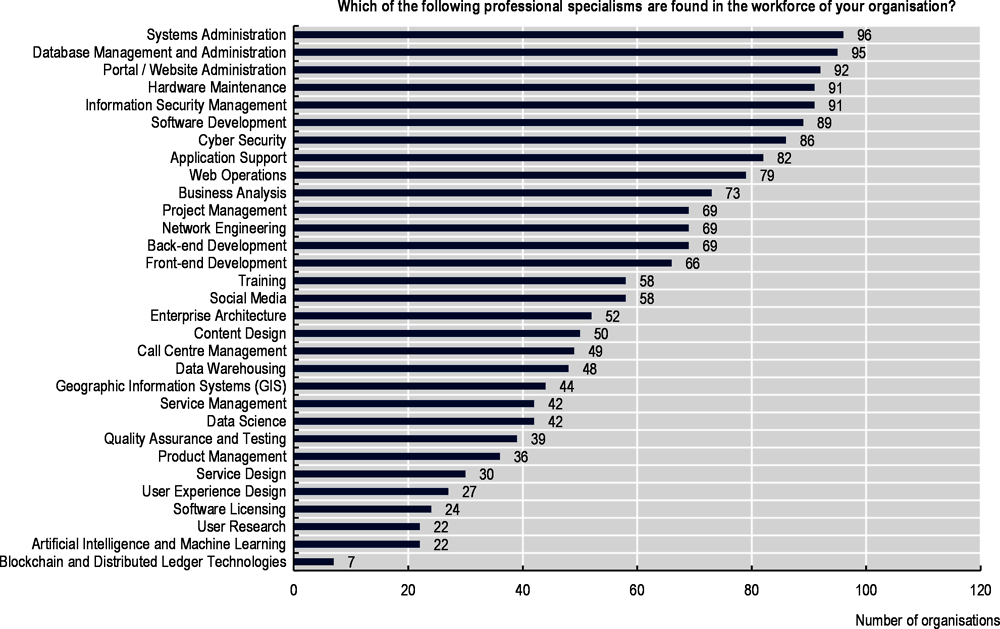

The survey supporting this review reveals that at least 80% of organisations are equipped with IT skills such as systems administration (85% or 96 out of 113), database management (84% or 95 out of 113), website administration (81% or 92 out of 113), hardware maintenance (80% or 91 out of 113) and information security management skills (80% or 91 out of 113). Although these figures are encouraging, the digital professional roles are more rare among organisations and are located at the bottom of Figure 4.9, for example data science (37% or 42 out of 113), service design (26% or 30 out 113) and distributed ledger technologies (such as Blockchain) (6% or 7 out of 113). These roles are crucial in the public sector to better understand users and best design and deliver services that could best meet their needs. Therefore, a focus on creating job positions, hiring digital experts and encouraging the workforce to upskill in these areas would be highly beneficial to the Turkish public sector in the long-run.

Figure 4.9. Professional specialists available in the workforce of the public sector

Note: Based on 113 participants.

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

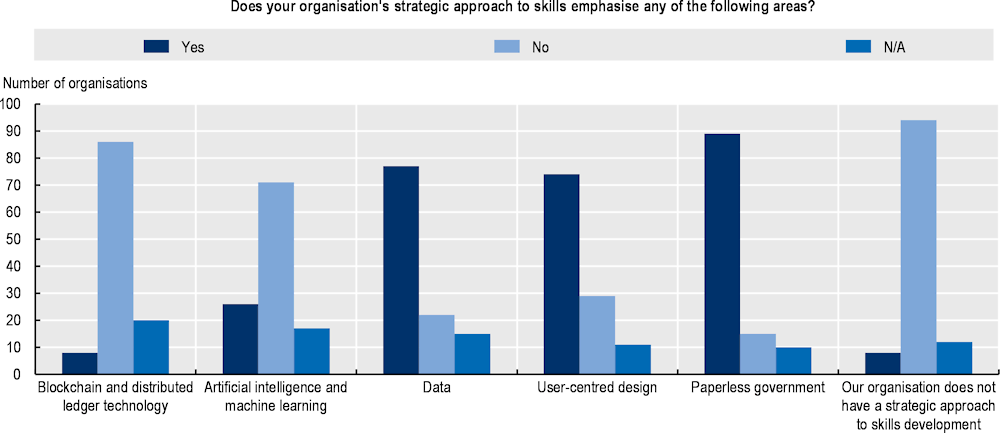

Figure 4.10 shows that the survey conducted to support this review found an emphasis on paperless government (78% or 89 out 113 participants). A large majority of organisations shared that, as part of the scope of the paperless state project, institutions organised trainings and activities for an efficient and effective use of the Electronic Document Management System (Elektronik Belge Yönetim Sistemi, EBYS), which has led the number of requested documents to drop by 70% on average. Many organisations are also focusing on data (68% or 77 out of 113) and user centred-design (65% or 74 out of 113) but only a small number are taking a strategic approach to skills in areas such as artificial intelligence and machine learning (22% or 25 out of 113), or distributed ledger technology (such as Blockchain) (6% or 7 out of 113). This shows that Türkiye overall has a good understanding of skills approaches in the public sector to produce quality services, however deeper knowledge and higher investment in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and distributed ledgers (such as Blockchain) could level up the design and delivery of services in a more accurate and safer manner.

Having the right mix of digital professional skills in the Turkish public sector is vital for its digital transformation. To achieve this, the government could consider creating an environment that encourages upskilling and learning by offering training in digital areas part of a professional development plan. It could also focus on recruiting digital talents with expertise in emerging technologies and creating new positions to accelerate the digital transformation journey. The National Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2021-2025 includes measures in recruiting and training individuals with artificial intelligence skills in the public administration (Ministry of Industry and Technology/Digital Transformation Office, 2021[19]). One example of such an initiative is the creation of a young talent pool for artificial intelligence as part of the National Internship Programme (see Box 4.1), which gives public sector employers access to these skills, and provides talented students with an opportunity to establish themselves in a public sector career.

Figure 4.10. Strategic approach to skills in the Turkish public sector

Note: Based on 113 participants.

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Digital government leadership skills

As demonstrated in the previous section, building a work environment that is ready for the digital transformation relies on leadership. The digital government leadership skills are key as leaders need to show that the application of digital, data and technology is not optional and apply digital government user skills to shape and encourage digital change.

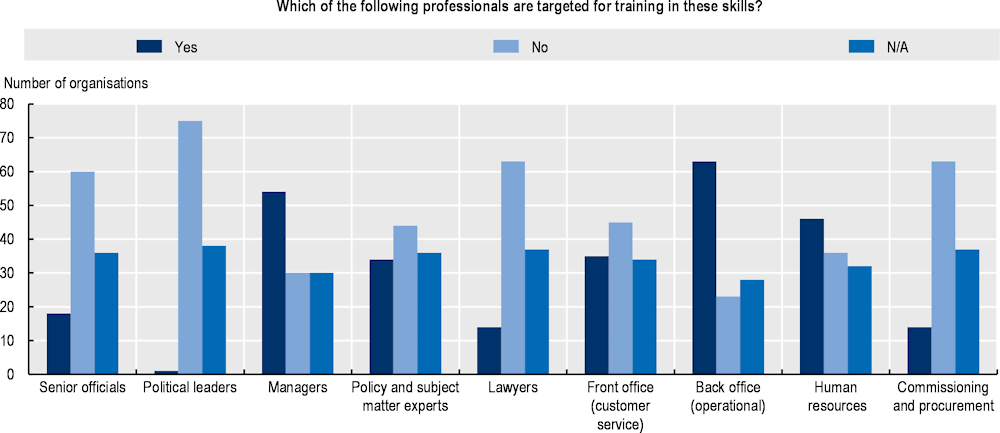

The OECD team observed through the Digital Government Survey of Türkiye that only 1% of political leaders (1 out of 113) and 16% of senior officials (18 out of 113) received trainings (Figure 4.11). These results are critical as digital government leadership trainings inform leaders about general quality of leadership, how to exercise digital government user skills and actively shape an environment that encourages digital transformation. Therefore, low engagement of political leaders and senior officials may damage trust, as the workforce may question the reliability and accountability of their leadership in their digital strategy. By acting as role models and championing the benefits of digital government, they would inspire the workforce to do the same.

To improve this, Türkiye could formalise providing the digital government user skills training to all public servants and have leaders join the training along with other staff, in addition to targeting them with specific trainings. Strengthening the digital government leadership’s skills implies targeting in building their capacities to model and demonstrate the five digital government user skills, and to embed digital government practice in the mindset of public sector leaders as they look to create the right environment and build a digital workforce (OECD, 2021[2]).

This would not only strengthen trust within the organisation and make leaders seem more approachable and open to change, but also increase their motivation and nurture curiosity. Estonia has designed a programme called the Newton Program, to develop participants’ leadership, innovation and technology skills to prepare the next generation of senior leaders. Similarly, France’s Digital Directorate (DINSIC)1 established a coaching programme for senior leaders to overcome the limits of existing trainings for senior leaders that appeared to be short and superficial (Gerson, 2020[20]).

Figure 4.11. Professionals in the public sector receiving trainings in Türkiye

Note: Based on 113 participants.

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

The role of leaders is vital in ensuring that each of these five areas is considered in supporting the environment for government transformation. Not only in their behaviour but in the support they provide to ensure training is made available for public servants to build their confidence in both 21st century and digital government user skills. Türkiye would also benefit from recognising the importance of both socio-emotional and professional skills in the composition of the teams created to tackle public policy problems in the digital age. These measures would not only promote a digital culture across all levels of the government, but also equip public servants with up-to-date digital skills to design and deliver quality services that meet users’ needs given the rapid evolution of digital tools and technologies.

Maintaining digital talents in the public sector

After establishing working conditions and identifying the necessary skills to advance the digital transformation, maintaining a competent digital workforce is the third pillar of the OECD Framework for Digital Talent and Skills in the Public Sector (OECD, 2021[2]). Governments need to apply the practical steps necessary to develop, retain and recruit a workforce to advance digital government maturity. Recruitment methods, career planning, workplace mentoring, training and the role of the public sector need to be redesigned. This creates opportunities to improve approaches to particular areas and ensure that the workforce is, and remains, sufficiently digital

Attracting talents

OECD Government at a Glance 2021 underlined the importance for governments to attract and recruit a digital workforce to keep pace with the evolution of society and address service design and delivery challenges, as well as the necessity for government to understand candidates’ motivations to apply for the public sector, match market wages and run promotion campaigns through multiple channels (OECD, 2021[13]). In line with the OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability, it is equally essential that governments “recruit, select and promote candidates through transparent, open and merit-based processes” (OECD, 2019[8]).

As the digital transformation is led by a digital workforce, there is a need to start by attracting the right talents to take part in this journey. Türkiye is well positioned in this respect when compared to the experience of the 38 countries measured by the Survey on the Composition of the Workforce in Central/Federal Governments (OECD, 2021[13]). Israel, Türkiye and Hungary are the only countries with over 30% of their public sector workforce aged between 18 and 34, compared to an average that is below 20%. Moreover, only three countries have a smaller proportion of public sector workers aged 55 years and over (OECD, 2021[13]). The youthfulness of Türkiye’s public sector is an important foundation for digital transformation. One possible factor in this is the focus given by the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi) to making the Turkish public sector an attractive place for younger workers (examples of which are discussed in Box 4.1).

However, there is an ongoing need to continue investing in activities to accommodate and welcome young talents into the public sector. The COVID-19 pandemic may have forced administrations to embrace new technologies and adjust to the needs of working remotely with a new, more flexible, culture. However, without a clear and solid recruitment and retention strategy, the public sector is likely to lose potential talents to the private sector.

Under the leadership of the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi), the “Career Gate” (Kariyer Kapısı) service integrates with the e-Government Gateway and supports recruitment of various types (see Box 4.1) (Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2022[21]). This is not the only route into public employment as there is a separate recruitment platform managed by the General Directorate of Turkish Employment Agency (Türkiye İş Kurumu, İŞKUR), which includes jobs of registered Public Institutions or Private Sector Companies.

Developing separate platforms that speak to different needs can be valuable where those audiences would not overlap. However, there are potential pitfalls in operating multiple approaches, not least in introducing greater overheads for applicants who may focus their efforts in one location and miss out on the roles advertised elsewhere. The platforms themselves help to mitigate these risks by allowing candidates to be kept informed, rapidly, of suitable jobs or updates to their applications. During the Review process the OECD team has noted the lack of a formal narrative, supported by a co-ordinated and dedicated strategic plan for talent and skills in the public sector. The existence and operations of the Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi) is however a clear indication of practical steps being taken to deliver tools, initiatives and co-ordination in the talent management and human resource efforts of the Turkish public sector from the centre, and as a whole. Although it is positive that the majority of organisations felt that there were no issues in terms of human resources and capacity, it is crucial to set up a strategy to address the full breadth of challenges involved with achieving a digitally matured workforce, including attracting the right candidates to increase governments’ digital maturity.

The power of effectively branding the public sector as an appealing place to work can increase the quality of applications and draw attention from the best candidates, an approach supported by tools such as the Career Gate (Kariyer Kapısı), which has the potential to become a singular focal point for recruitment. To increase the success of these approaches, institutions could establish their own dedicated recruitment teams and proactive recruitment strategies to take advantage of events like the National Talent Fairs (see Box 4.1) and conduct outreach with schools and through social media. They might also consider creating partnership programmes with universities and encouraging under-represented groups to apply through communication campaigns. One advantage of all organisations using Career Gate (Kariyer Kapısı), as a single platform would be to achieve economies of scale and scope in these activities with communicating the work and the worth of the public sector being able to reach a wider audience and increase the talent pool considering a career in the public sector. Besides this, public institutions also need to acknowledge that the recruitment process must evolve to capture talents’ interest and help them unleash their digital skills.

Similarly, ensuring diversity and gender equality of teams is equally important and there are important efforts evident in some of the initiatives that have already been discussed in this chapter (see Box 4.1). One inspirational example of how a country has achieved a greater gender balance is that of Estonia, discussed in Box 4.7

Box 4.7. Estonia’s nudging methods to increase the share of women in ICT professions

In 2019 Estonia started an 18-month research project led by the Ministry of Social Affairs concentrating on developing and piloting nudge methods to increase the share of women among ICT sector students and employees. The project is co-funded by the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Estonian Research Council. The following actions are a part of the study:

1. Compiling the current state of play based on existing studies and analysis (including educational choices of girls and women, dropping out of education in the ICT sector, progress in the job market, etc), mapping the possible reasons for the low number of women in the ICT sector. A qualitative study within main stakeholder groups will be carried out.

2. Presenting proposals for nudging methods with the goal of increasing the number of women in ICT, including in management. These methods need to be piloted for at least 9 months.

3. After the pilot phase carrying out an analysis of the implementation of nudging methods as the basis for a final report and recommendations about future use of nudging methods.

Source: Provided by the Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) Thematic Group on Digital Talent and Skills.

Retaining talents

A government with an older workforce has the benefit of the wisdom and experience that comes with age but can struggle to appeal to the next generation of talents. In contrast, a youthful government workforce, such as that found in Türkiye, can be attractive to young talents but will need to be aware of the needs of existing, older, staff to ensure they retain the experience they provide (OECD, 2021[13]). Once the talents are in, governments need to do their best to retain them as high turnover can be not only costly, but also affect productivity (Felps et al., 2009[22]). During the fact-finding mission, some of the interviewed public institutions expressed the fear of staff leaving the public sector in favour of better salary and benefit offers from the private sector. The Turkish government has put in efforts to become more attractive through the "contractual IT personnel" programme since 2008, which by-law allows institutions to hire digital talents and offer them extra financial benefits to increase its competitiveness against the private sector, however such programme lacks operational effectiveness in terms of administrative structure.

Since talents that join the public sector are not usually attracted by financial rewards but are rather purpose-driven and value a healthy work-life balance, organisations could focus on what the workforce wants and provide them with a well-designed, fair, trusted and attractive reward system (Gallup, 2016[23]). Along with that, a focus on clear career perspective, job growth, profession and personal development would also help retain the workforce as these measures would offer them the opportunity to try a large variety of work and take up different challenges, given the multi-disciplinary aspect of digital governments (further discussed in the chapter), without having hierarchical promotions.

For instance, in Uruguay, the National Agency for e-Government and Information Society (AGESIC) encourages the retention of its staff in several ways including creating a flexible working environment, providing attractive training in tools and vanguard technologies and offering staff the opportunity to professional challenges of working on projects with national impact. This collectively creates a powerful reason for employees to stay with the organisation (OECD, 2021[2]). In the United Kingdom, while the Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT) Professional Capability Framework allows for different pay structures for different roles it is underpinned by a clear, transparent and standardised way of compensating talents. The DDaT Pay Approach aims to provide simple, effective, and consistent guidance on pay to work with existing flexibilities in an organisation’s pay structure to attract, recruit and retain these specialist skills (UK Central Digital and Data Office, 2017[24]). Both country examples demonstrate that such structures help to maintain trust and fairness within the public sector.

Developing and maintaining skills

After setting a retention system for talents, it is fundamental to look at how to develop and maintain skills within the public sector as skills can be easily forgotten or lost if not applied, as well as taken away if knowledge is not well-managed within. The OECD team noticed great efforts in organising formal trainings to empower digital talents to own their work and increase skills within the public sector to reduce dependency on external third parties. A couple of effective examples of moving this training online were observed in the Distance Learning Gate (Uzaktan Eğitim Kapısı) (see Box 4.4) and the BTK Academy. The BTK Academy is an initiative of the Information and Communication Technologies Authority (Bilgi Teknolojileri ve İletişim Kurumu, BTK) and provides training for both public and private sector employees in ICT including innovative technologies like artificial intelligence and distributed ledgers (such as Blockchain).

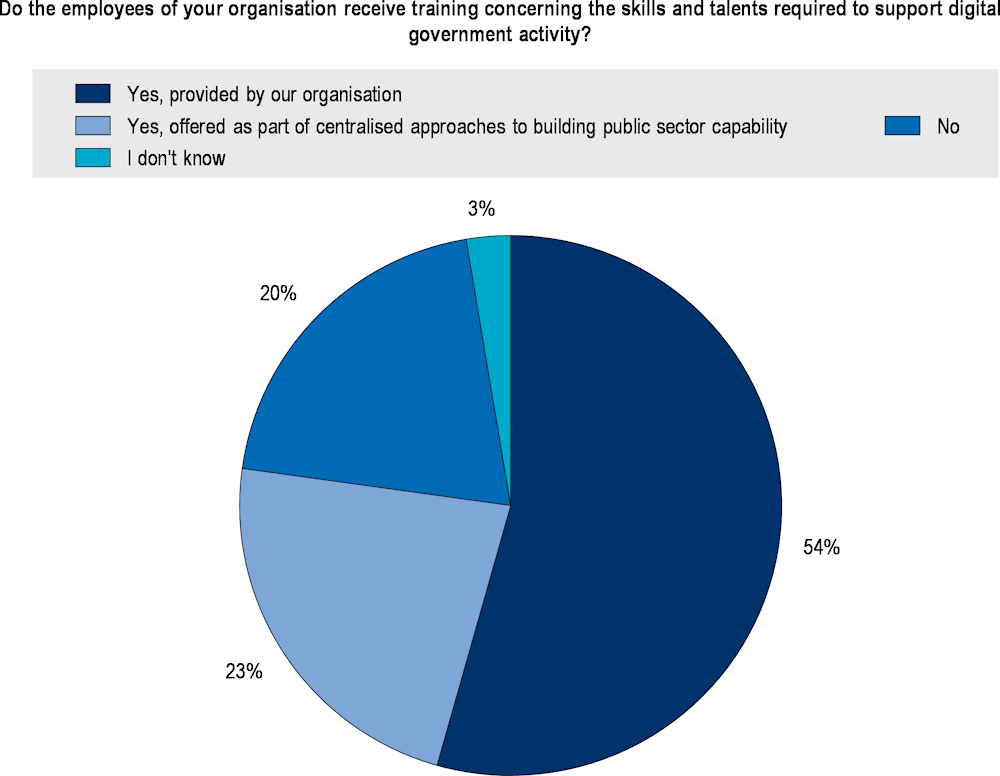

As shown in Figure 4.12, a majority of public sector institutions in Türkiye have in-house teams that initiate their own training schemes (54%). However, 23% of organisations outsource their needs and are therefore reliant on either private sector suppliers or the teams at Türksat and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (Türkiye Bilimsel ve Teknolojik Araştırma Kurumu, TÜBİTAK). The presence of third-party contractors can be an important opportunity to develop in-house capacity but throughout the review process there has not been any evidence of practices to encourage the transfer of skills from those outsourced providers to internal talents. This absence results in organisations remaining reliant on an external delivery ecosystem. To maximise alignment, institutions without internal capacity need to ensure that both the contracting bodies and their suppliers align with national strategic plans for training, including around the five core digital government user skills discussed earlier and supportive to public servants contributing to establishing a digitally enabled state regardless of their role or tier of government. Given that external and private sector suppliers can be important partners for governments in developing their capacity to deliver on their ambitions for digital transformation, formally identifying the transfer of skill to government is a common practice among several countries, such as Colombia, Spain and Uruguay.

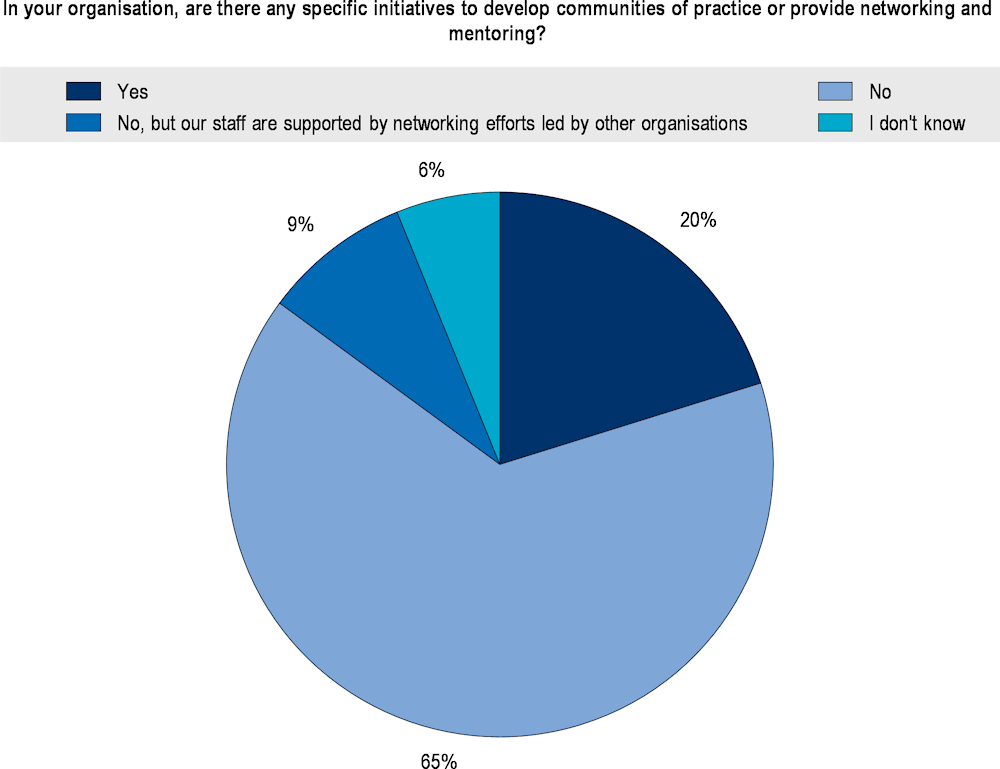

Informal support such as communities of practice, networking opportunities and mentoring can be another helpful practice for developing the skills of data, digital and technology practitioners. Informal approaches rely on creating a safe environment where talents not only develop and maintain their skills organically, but also share good and bad experiences, collaborate and learn together. Such initiatives are crucial as they aim at strengthening the digital skills of the workforce and enable them to maintain, reuse and exchange the knowledge they have acquired through formal trainings. However, as indicated in Figure 4.13, only 20% of organisations in Türkiye are investigating these approaches. The Human Resources Office (İnsan Kaynakları Ofisi) is one organisation that is doing so, with the intention to convene a community of practice for human resource professionals from across the public sector. Lessons from these efforts could be used to create similar communities of data, digital and technology practitioners. While these would be valuable within institutions, there is value in creating cross-government networks to create the widest possible sharing of experience and wisdom.

Figure 4.12. Trainings to support digital government activity

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

As part of personal growth, mentoring programmes can also be important in pairing junior staff with a more senior colleague to create opportunities for transfer of skills, experience and knowledge. By formalising such practice, this would not only reinforce the learning culture of the organisation and strengthen the sense of belonging but also generate in-house training and cultivate loyalty, which would create greater workforce sustainability.

To develop and maintain skills within the Turkish public sector, a few measures could be considered. Türkiye could encourage further development of existing communities of practice to include more institutions. They could also enlarge their informal trainings and hold retrospective meetings where teams share what went well, what did not and what could be improved, or schedule “show and tell” where people share what they have learned. In order to fulfil these ambitions it will be important to find ways to build a dialogue between those focused on digital transformation and those focused on human resources. The OECD review team found that those most heavily involved in digital transformation did not necessarily have a deep awareness of all the activity taking place to improve and enhance the quality of the workforce. As such, this highlights the importance of a common narrative and shared strategy which recognises the fundamental importance to digital transformation of a digitally mature workforce.

Figure 4.13. Initiatives to develop and maintain digital skills in the Turkish public sector

Source: OECD (2021[5]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

As an example, the United Kingdom’s Department of Health and Social Care held their first Digital Show and Tell to showcase recent digital projects and explain how they run them (Stansfield, 2015[25]). These practices make talents feel empowered, owners of their work and create an in-house production culture, which would in the long run reduce outsourcing activities and dependence on external suppliers. The government could also consider requiring third party contractors to complete training on digital government user skills to ensure they have a consistent baseline of skills with public servants. Additionally, contractual clauses can be used to ensure the transfer of specific skills from suppliers to public servants. In the United Kingdom, this process is supported by Technology Code of Practice (as discussed in Box 4.8), which set expectations for working with suppliers around the quality of outcomes, encourage skills transfer to public servants and retain access to data without losing ownership of intellectual property. Similarly, formalising mentoring programmes between a junior and a more senior staff could not only contribute to the retention of knowledge in-house, but also invest in public servants’ personal growth.

Box 4.8. The United Kingdom’s Technology Code of Practice

The Technology Code of Practice was first published in 2016 by the UK Government Digital Service and since 2021 has been the responsibility of the UK Central Digital and Data Office. The Code of Practice provides a set of criteria to help governments design, build and buy technology. It recommends that public servants consider each of its 13 points and take steps to align with those that are mandatory and follow as many of the others as are practical. Organisations are encouraged to align their organisational technology and business strategies with the Code of Practice.

The Technology Code of Practice forms part of the UK’s Digital, Data and Technology Functional Standard (DDaT Functional Standard) discussed in Chapter 3 and helps introduce or update technology so that it:

meets user needs, based on research with your users

is easier to share across government

is easy to maintain