Building on the empirical analysis, this chapter focuses on opportunities to improve core values that inform government actions and thereby influence levels of institutional trust. These include government’s openness, integrity, and fairness. It stresses the importance of going beyond the traditional understanding of transparency towards a new and broader communicational sense, which requires planning how public information is going to be communicated and anticipating people’s needs to better arm them against mis- and disinformation. It also entails strengthening a preventive integrity approach, investing more in training beyond awareness-raising, and including integrity elements in risk management and internal control. Finally, as a way to strengthen fairness it recognizes the importance of engaging with groups that may feel left behind, particularly at the local level and in more remote regions and ensuring that there are specific spaces and channels to communicate with them.

Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in New Zealand

4. Values and trust in New Zealand

Abstract

4.1. Openness

4.1.1. Openness as a core principle that underpins public service and governance

Open government refers to a culture of governance that promotes the principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation in support of democracy and inclusive growth (OECD, 2017[1]). Cross-nationally, promoting and investing in transparency and openness initiatives is found to be associated with higher levels of public trust (OECD, 2022[2]; Bouckaert, 2012[3]; Beshi and Kaur, 2020[4]). Yet, the relationship between openness and trust is complex: cultural values play a significant role in how people perceive and evaluate openness policies and their impact (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2013[5]). Most importantly, the effect of openness on public trust is mediated by additional elements, making openness a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for positively influencing trust. For instance, greater transparency will not necessarily lead to increased trust if it exposes controversial information or corruption cases (OECD, 2017[6]; Bauhr and Grimes, 2014[7]). Furthermore, evidence shows that information on and perceptions of government performance may affect the impact of openness initiatives (Alessandro et al., 2021[8]), and that people need to feel trusted by the government in order to trust it, believing that an invitation to participate is genuine and that they are empowered to influence political systems (Schmidthuber, Ingrams and Hilgers, 2020[9]).

Building on the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (OECD, 2017[1]), the OECD Framework on the Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions measures three key aspects of openness. First, it addresses government’s mandate to inform, including letting people know and understand what the government does and improving transparency.1 Second, it assesses consultation, which entails a two-way relationship in which stakeholders provide feedback to the government and vice-versa. Third, it looks at the government’s capacity to engage citizens and other stakeholders, to include their perspectives and insights and promote co-operation in policy design and implementation. The OECD Trust Survey includes the following three questions gauging these elements in New Zealand:

If you need information about an administrative procedure (for example obtaining a passport, applying for a benefit, etc.), how unlikely or likely do you think it is that the information would be easily available?

If a decision affecting your community is to be made by the local government, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that you would have an opportunity to voice your views?

If you participate in a public consultation on reforming a major policy area (e.g. taxation, healthcare, environmental protection), how unlikely or likely do you think it is that the government would adopt the opinions expressed in the public consultation?

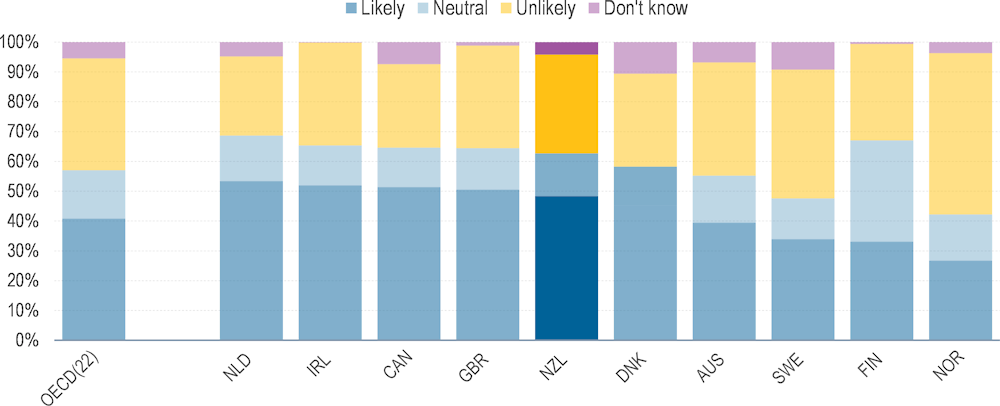

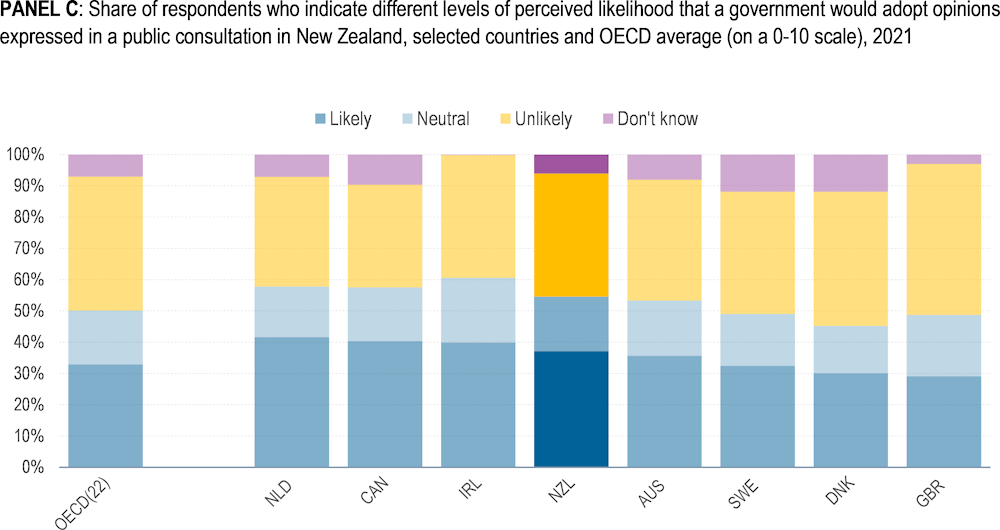

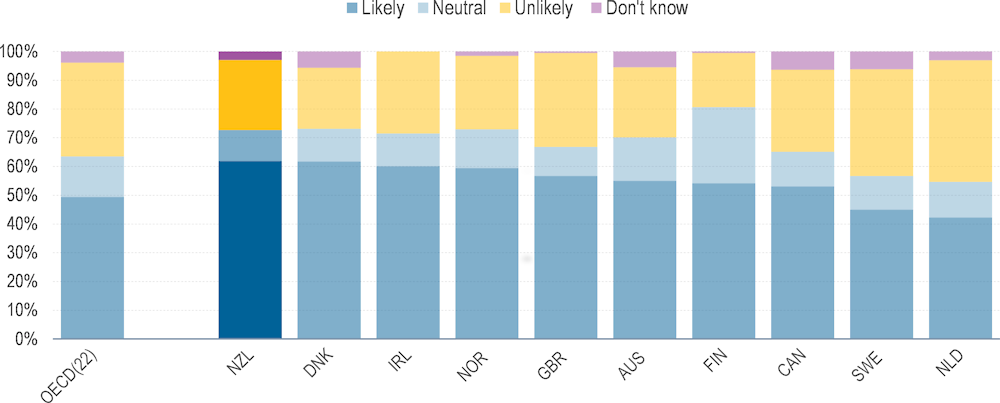

Results from the 2021 OECD Trust Survey show that New Zealanders’ perceptions of openness are quite positive on transparency of information, but less encouraging on how they see their voice in public decision making (Figure 4.1). Around 8 in 10 (77%) respondents believe that information about administrative procedures is easily accessible (12 percentage points above the average across OECD countries). However, slightly less than half New Zealanders perceive they have enough opportunities to voice their views (48%) and a minority believe that institutions would listen to these views (37%). Although these levels appear as low, New Zealand fares above OECD averages in the three indicators..

Across OECD countries, there is a widespread scepticism about opportunities for engagement and participation, as Figure 4.1C shows. In New Zealand, in line with OECD countries, positive perceptions that the government would adopt inputs provided in public consultations is found to be a key determinant of trust in the public service and the local government (Figure 2.18 and 2.20). Additionally, having the opportunity to voice one’s views has a statistically significant, albeit smaller, effect on trust in local government.

Figure 4.1. New Zealanders are satisfied with transparency of information, but a minority is confident in opportunities to voice and engage

PANEL A: Share of respondents who indicate different levels of perception of the ease of finding information about administrative procedures in New Zealand, selected countries and OECD average(on a 0-10 scale), 2021

Note: Figure presents the distributions of responses to the question “If you need information about an administrative procedure (for example obtaining a passport, applying for benefits, etc.), how likely or unlikely do you think it is that the information would be easily available?” (Panel A); “If a decision affecting your community is to be made by the local government, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that you would have an opportunity to voice your views?” (Panel B); “If you participate in a public consultation on reforming a major policy area (e.g. taxation, healthcare, environmental protection), how likely or unlikely do you think it is that the government would adopt the opinions expressed in the public consultation?” (Panel C). OECD(22) refers to the unweighted average across 22 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

4.1.2. Public institutions in New Zealand have a long-standing culture of transparency

Transparency is a cornerstone of New Zealand’s public administration. The Official Information Act (OIA) was first adopted three decades ago (1982), formalising the principle of freedom of information in a pioneering legal framework. The Act’s liberal disclosure approach creates the rights to a process for accessing public information, which goes beyond just listing relevant sources and documents that could be accessed (Liddell, 1997[10]; Snell, 2006[11]). New Zealand has also been member of the Open Government Partnership since 2013 - two years after its creation - and is currently designing its fourth national action plan in order to deepen participation, transparency and accountability. The country promotes the principle of openness by default and is one of the top 9 country leaders in digital government, mainly regarding data availability and accessibility (OECD, 2020[12]). New Zealand has also advanced in the proactive disclosure of government information. In 2019 a new policy was established to proactively release of all2 Cabinet and Cabinet committee papers.

Recent experts’ assessments consider New Zealand’s regulations as strongly transparent with predictable enforcement,3 reflecting the impact of latest initiatives, such as the creation of a single user-friendly website that brings together all national laws and facilitates access to legal information for the public, or easy online access to parliamentary hearings. Indeed, strengthening and designing innovative transparency initiatives has been an important part of New Zealand’s successful strategy to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic (Box 4.1).

Beyond multiple openness initiatives and policies, New Zealand promotes broad open government literacy – understood as the combination of awareness, knowledge and skills that public officials and stakeholders need to engage successfully in open government strategies and initiatives –, which is essential to a real culture of openness. According to the OECD Open Government Survey, the country not only provides clear guidelines on open government data and stakeholder participation, but also provides training to civil servants to embody open government principles (OECD, 2021[13]).

Box 4.1. COVID-19 and openness

As in many OECD countries, the pandemic led to physical restrictions in public life: people were unable to meet representatives, attend public hearings, etc., and commitments or initiatives related to face-to-face engagement with public institutions were halted during the lockdown. However, New Zealand developed remarkable initiatives to promote openness and to strengthen transparency and engagement through digital means during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the outbreak of the pandemic, an Epidemic Response Committee was established to deliberate on the government’s management of the COVID-19 epidemic. This was the first select committee in New Zealand to have its proceedings broadcast live on Parliament TV. The broadcast aimed to provide maximum public visibility for the Committee’s work while the House was unable to meet because of COVID-19 restrictions. Furthermore, meetings of the Committee were live-streamed to the New Zealand Parliament Facebook page around three times a week, reaching an audience of around 1000 people on average. Similar committee broadcasting was undertaken for ministerial appearances and COVID-related hearings during 2021 lockdowns.

The government also set the policy to proactively publish cabinet documents every 15 days, and the Prime Minister’s and the Director General of Health broadcast daily press conferences to update New Zealand’s “team of 5 million” on the progress in tackling the virus.

In addition, Karaehe Kaewa (wandering classroom) was developed. This initiative includes online education visits to the Parliament and allowing civic education to be offered to schools outside of the capital. Finally, the government organised a Super Saturday Vaxathon, a day-long TV livestream promoting vaccination, showing vaccination centres and people being vaccinated, with the goal of achieving 100,000 vaccine doses.

Source: Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lL5r8Gv-tQ4

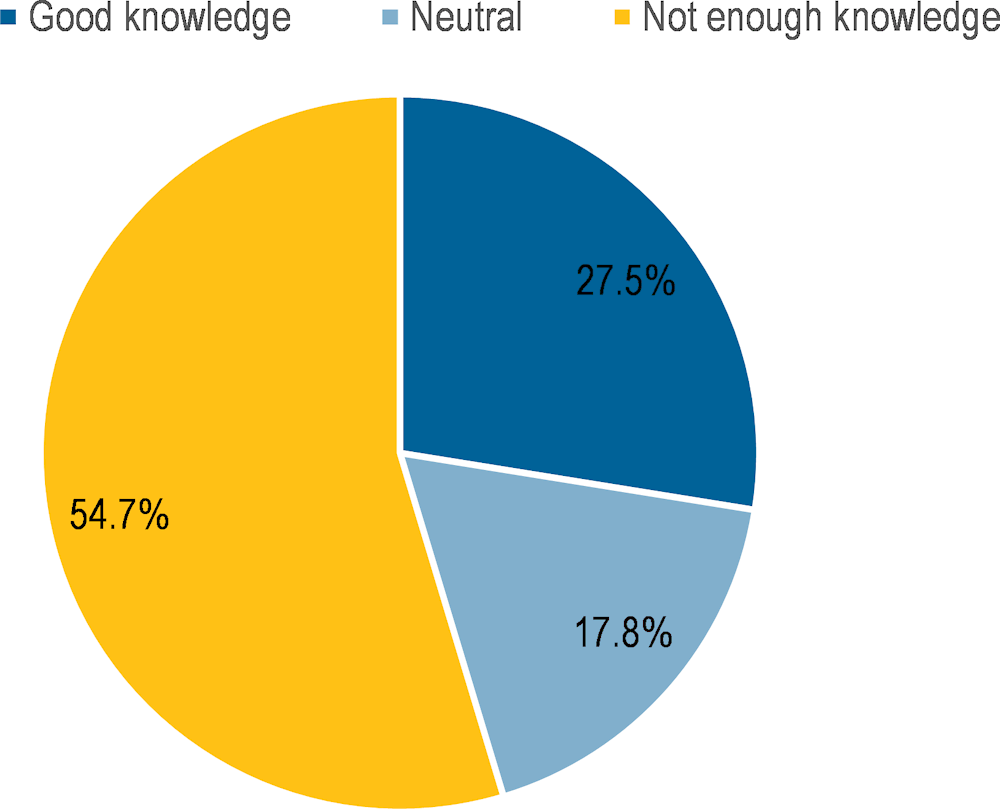

However, as per the last report of the Global Right to Information Rating (RTI), New Zealand’s legal framework on access to public information has some limitations. Access to government information may be undermined by multiple exemptions and restrictions to disclose information included in other regulations. In addition, the scope of the Act falls short of covering Parliament and some judiciary bodies, such as the Controller or Auditor General. Additional challenges can appear regarding access to government information at the local level, as lack of clear details or insufficient training to staff and counsellors may lead to misinterpretation of the Act. For instance, although the public is allowed to access local authorities’ meetings, there are exceptions if the topics to be addressed require a closed meeting, but these exemptions are not clearly specified in the regulations. This has resulted in a high number of complaints being presented to the ombudsman regarding access to public information at the local level. According to the OECD survey, 54.7% of respondents consider that they know how the government works Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2. A majority of New Zealanders report knowing how the government works

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents responses to the question “How much do you know about how central government in New Zealand works?” The ''less knowledge'' proportion is the aggregation of responses from 0-4 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “more knowledge” is the aggregation of responses from 6-10, where 0 =nothing at all and 10 =a great deal.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

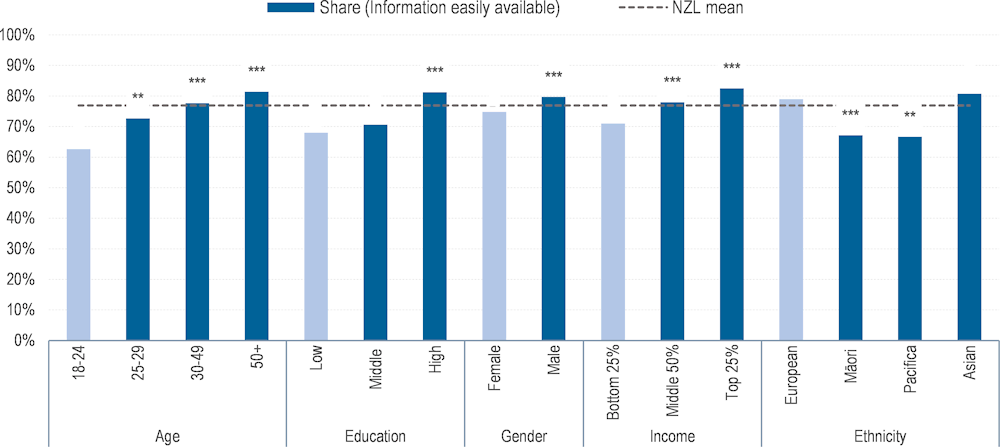

Furthermore, although perceptions of transparency are overtly positive in the country, there are some population groups that find it harder than others to access public information. The proportion of respondents of the OECD Trust Survey who believe information on administrative procedures is easily accessible is lower among the less educated, the young, the Māori and respondents from Pacific communities, as well as for those who reported having financial concerns (Figure 4.3). These groups have shown a similar perception of inaccessibility when asked about their knowledge of the functioning of the government,4 which may signal that there is a need to make the functioning of government more accessible to them (Box 4.2).

Figure 4.3. Younger people, those with lower education and income are less likely to believe that information is easily available

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents the distributions of responses to the question “If you need information about an administrative procedure (for example obtaining a passport, applying for benefits, etc.), how likely or unlikely do you think it is that the information would be easily available?” The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “NZL mean” presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. Top 25% and bottom 25% refers to the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. High education is defined as the ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, and low education refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Indeed, neither providing information (active transparency) nor granting the right to information to citizens through access to information laws (passive transparency) may be enough to ensure a broader culture of transparency and openness. The “right to know” needs to be complemented by coherent communication strategies that aim to better inform people and shield them from mis- and disinformation. These strategies should set clear goals, target audiences and messages, and identify the best channels for reaching diverse groups of people. Those population groups and individuals who feel left behind or excluded from wider society need to be a particular focus. For instance, the “Unstoppable Summer: A COVID-19 Public Service Announcement”, a short musical video featuring the Director General of Health and shown before broad audience events, is a good example of how best to target youth. Other OECD countries’ initiatives designed to target specific population groups may be also relevant for increasing transparency in a communicational sense (Box 4.2). These communication elements are especially relevant in a context where personal beliefs and emotions play a key role in shaping public opinion beyond objective facts, and social media facilitate widespread distribution of these messages (Schnell, 2022[14]). The adoption by the New Zealand Government of a Plain Language Act in October 2022 is a step in the right direction to improve the accessibility of key documents for the public and could be an important element in strengthening trust between public agencies and groups that may feel they have been left behind.

Box 4.2. OECD countries’ initiatives to reach broader audiences

In order to better communicate and broaden their understanding of transparency, OECD countries have designed various initiatives to reach broader population groups.

In 2010, the US enacted the Plain Writing Act to enhance citizen access to government information and services by establishing that government documents issued to the public must be written clearly. The Act is accompanied by guidelines on its implementation that are extended to the public administration.

Costa Rica’s Handbook on Communication (2018-2022) includes detailed guidelines on communicating with vulnerable groups and on sensitive topics (including migration, gender-based violence, LGTBQ+ rights, and people with disabilities).

The Government of Canada’s Policy on Communications and Federal Identity (2016) establishes as one of its four objectives that communication should be projected equally in both official languages to make the government visible and recognizable to the public in Canada and abroad.

Source: (OECD, 2021[15])

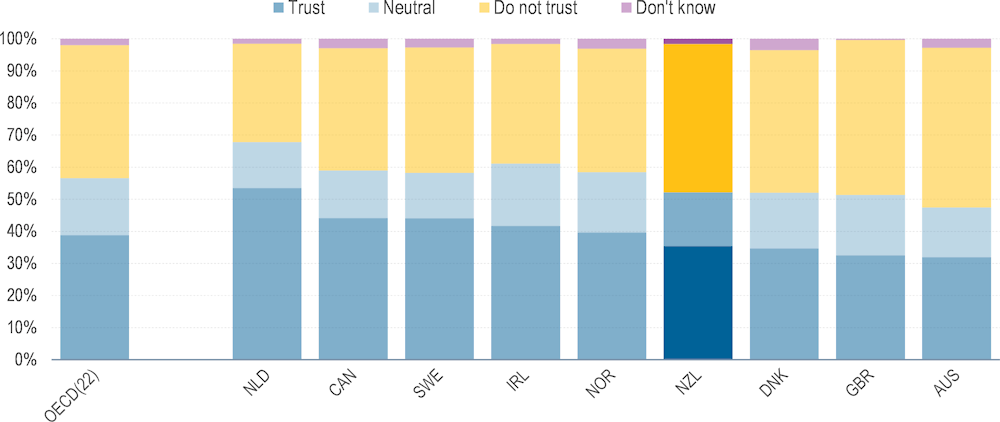

Only 35% of the population reported trusting the news media, making it the least trusted institution in the country (See Figure 2.1). Figure 4.4 shows that New Zealand fares below the OECD average (38.7%) and on the low end of the benchmarking group, just above Australia, the United Kingdom and Denmark. Promoting a healthy information ecosystem via a proactive and holistic “communicational” approach that promotes diverse, independent and quality media, supports media and digital literacy and considers transparency requirements and issues related to the business models of social media platforms would help prevent and counter mis- and disinformation (OECD, 2021[15]). This is of particular relevance considering the protests held in February- March 2022. A recent study found that during the protests, mis- and disinformation producers attracted more video views than all of the country’s mainstream media pages combined for the first time (Hannah, Hattotuwa and Taylor, 2022[16]).

Figure 4.4. About one-third of New Zealanders trust the news media

Note: Figure presents responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the news media?” The “trust” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “do not trust” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. OECD(22) refers to the unweighted average across 22 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

The OECD Principles of Good Practice for Public Communication Responses to Mis- and Disinformation can help promote a whole-of-society response to the challenges presented by the spread of misleading and harmful content. The ten principles include practical examples and reiterate the importance of governments’ communicating transparently, honestly, and impartially, and of conceiving of the public communication function as a means for two-way engagement with citizens. Ultimately, the principles provide practical guidance and present a range of good practices on government interventions aimed to counter mis- and disinformation, address underlying causes of distrust, and promote openness, transparency and inclusion. These principles could also help guide reforms to the media and social media to discourage the spread of mis- and disinformation. In addition to the principles, country experience with ongoing initiatives may support the whole communication strategy (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. RESIST initiative in the UK

The Government Communication Service of the United Kingdom launched in 2019 a counter disinformation toolkit to support public officials in preventing and tackling the spread of disinformation as well as in disseminating reliable and truthful information. The RESIST toolkit is divided into five independent components that helps to:

Recognise disinformation

use media monitoring for Early warning

develop Situational insight

carry out Impact analysis

deliver Strategic communication

Track outcomes

In addition to the toolkit, the UK Cabinet Office partnered with the University of Cambridge to create a game called Go Viral! (https://www.goviralgame.com/en). The game was designed to help the public understand and discern the most common COVID-19 misinformation tactics used by online actors, so they can better protect themselves against them. As per initial results, there have been over 207 000 digital ‘inoculations’ to health misinformation delivered through the Go Viral! Game, and the intervention was found to raise players’ ability to resist misinformation by up to 21%.

Source: UK Government Communication Service; UK’s presentation during OECD Public Governance Committee, October 2021.

4.1.3. New Zealanders are electorally active, but many feel sceptical about their political voice

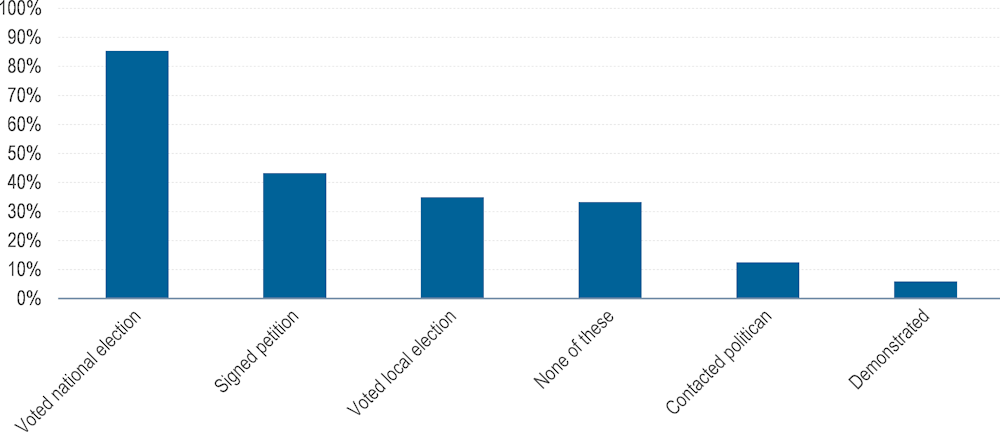

Although voting is not compulsory, levels of voter turnout in New Zealand are among the highest in the world. These levels have decreased steeply in recent decades, although in 2020 turnout levels were the highest since 1999 (New Zealand Electoral Commission, 2020[17]).According to the OECD Trust Survey, 85.1% of respondents reported voting in the 2020 Parliamentarian election elections, similar to percentages found in other high-trusting countries, such as Norway, Denmark or Sweden, and above the average across OECD countries surveyed (79%). However, New Zealanders present low levels of political engagement in other political activities - including voting in local elections (Figure 4.5) - and there is a widespread scepticism about people’s ability to influence political issues via routes other than voting.

Figure 4.5. Political participation in New Zealand

Note: Figure presents the share of respondents that mentioned having participated in the following form of political participation during the last 12 months.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

The application of the treaty of Waitangi as the foundational document of New Zealand has resulted in a multicultural society. Accordingly, institutional arrangements have been designed and improved across time to promote and enhance inclusiveness and make every New Zealander feel politically represented. Already in 1867, a Māori electoral roll was adopted, establishing parliamentary seats for Māori representatives. In turn, the 1993 electoral reform moved from a majoritarian to a mixed-member proportional system increasing the representativeness of ethnicities and ensuring that different voices and groups can be reflected and included in policy making (Karp and Banducci, 1999[18]). Indeed, according to New Zealand’s Electoral Commission, the gap between non-Māori and Māori enrolment rates was the smallest, 3.1 percentage points in 2020, and voter turnout for those on the Māori roll has been steadily increasing, from 57.6% in 2002 to 69.1% in 2020.

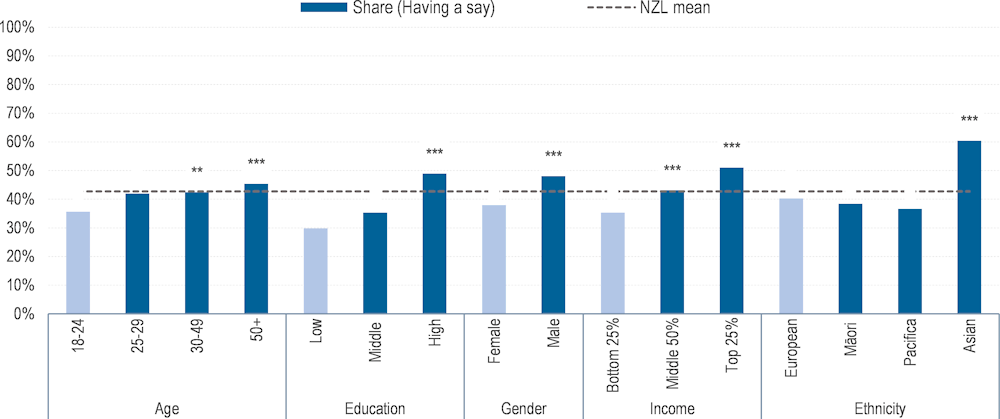

While Māori leaders have been present in political life for a long time, the first Māori party was formed in the 90s, and entered Parliament only in the 2000s; generally and for Māori political parties are one of the less trusted government institutions in the country (Nguyen, Prickett and Chapple, 2020[19]). In addition, other ethnic groups such as Pacifica population do not have the same level of organization and political participation (Nguyen, Prickett and Chapple, 2020[19]). According to the OECD Trust Survey, only around four in ten New Zealanders report feel they have a say in what the government does. The less educated and those reporting financial concerns feel more vulnerable and powerless (Figure 4.6). These results are of crucial relevance, as people’s perceptions that they can influence public decisions affecting their lives is the main determinant of trust in parliament in New Zealand (Figure 2.20). Moreover, recent studies using European Social Survey data found that initiatives that open up political processes to people, provide meaningful opportunities for political participation, and make them feel empowered to participate in politics and influence what the government does, may result in higher levels of public trust and political participation (Schmidthuber, Ingrams and Hilgers, 2020[9]; Prats and Meunier, 2021[20]).

Figure 4.6. The most vulnerable feel that they do not have a say in what government does

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents the responses to the question "How much would you say the political system in [country] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?" The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “NZL mean” presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. Top 25% and bottom 25% refers to the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. High education is defined as the ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, and low education refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

The civil society landscape in New Zealand is small. There are around one thousand groups listed in the National Residents Associations Database, but only 16.5% of New Zealanders reported participating at least once a week in sports or recreational activities and 30.2% reported volunteering through an organisation (Statistics New Zealand, 2021[21]). In interviews carried out for this study, it was also emphasized that funding was a key challenge for civil society organisations and that there was no organisation that could support civil society organisations in applying for funds, status, etc. Both of these elements may be related to feeling unheard and perceived difficulties in participating in politics (OECD, 2022).

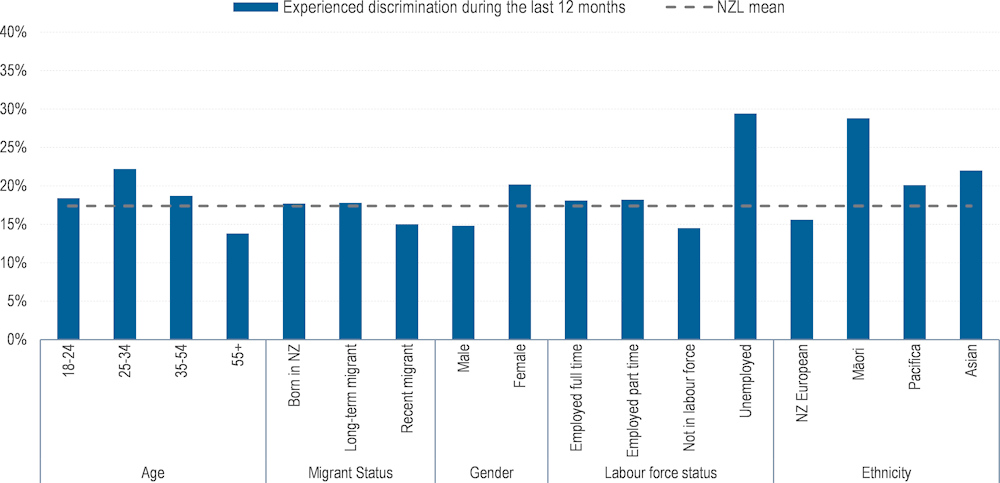

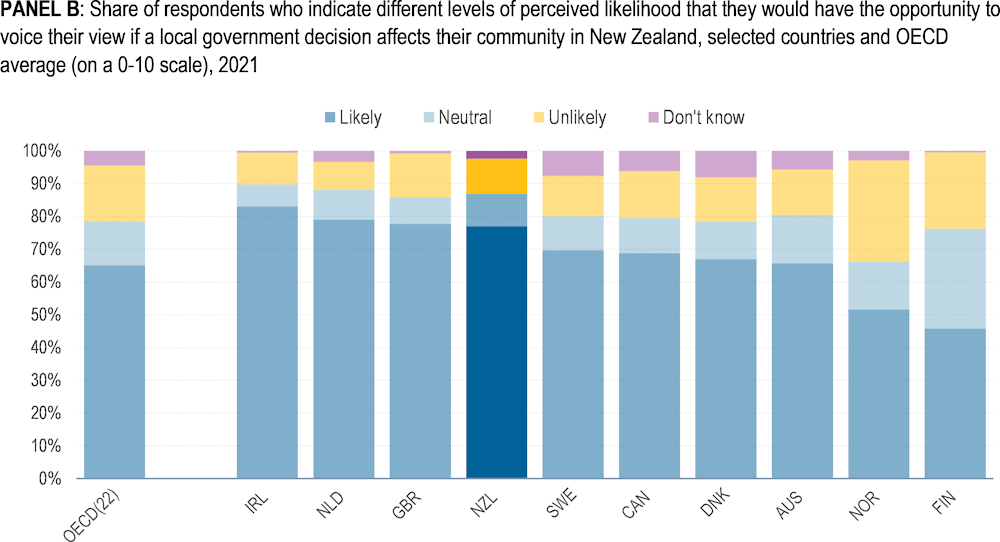

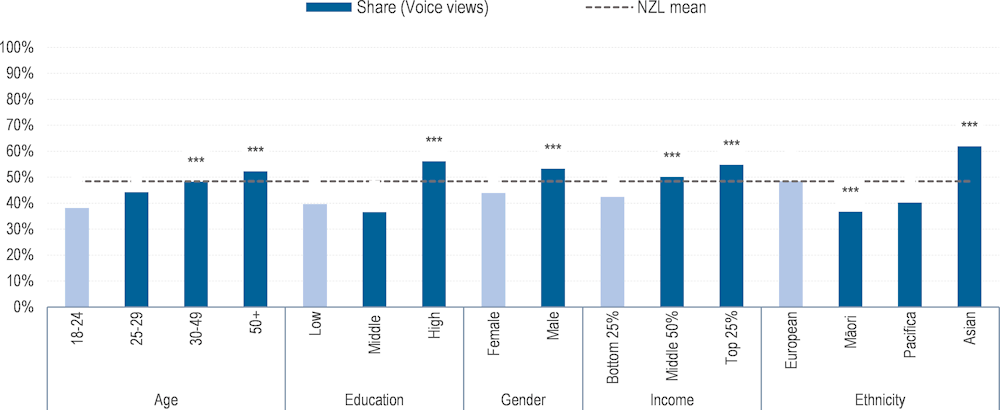

In addition, the OECD Trust Survey shows that some population groups feel more unheard than others (Figure 4.7). Across population groups, Māori are those who have the strongest feeling of not being involved: only 36.7% of Māori believe they would have the opportunity to voice their views in decisions affecting their community. In addition, and although it is not representative, there are clear participation gaps (12 percentage points) between those who are young and reported financial concerns compared to older respondents and those who do not feel economically vulnerable. These differences can have a crucial impact on the political system. Feelings of being unheard and participation gaps were found to affect electoral behaviour (Satherley et al., 2020[22]). New Zealand’s voter trends and polarisation patterns show that there are no strong divisions among voters in relation to demographic backgrounds.

Figure 4.7. The most vulnerable respondents are those more sceptical about opportunities to voice their views

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents the responses to the question "If a decision affecting your community is to be made by the local government, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that you would have an opportunity to voice your views? " The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “NZL mean” presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. Top 25% and bottom 25% refers to the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. High education is defined as the ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, and low education refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

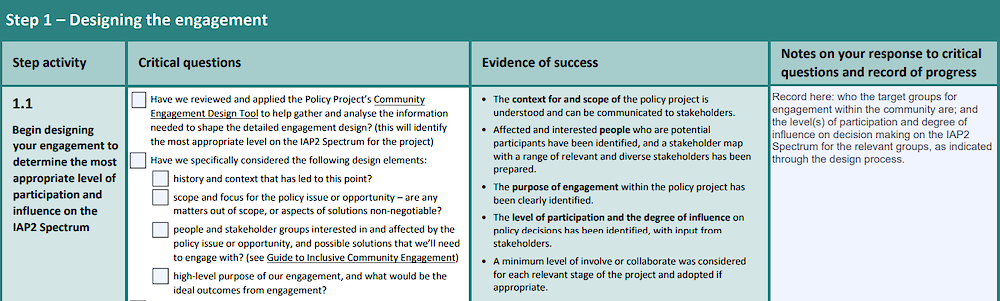

Beyond perceptions, New Zealand’s government is strongly committed to engaging people in policy making. According to New Zealand’s Cabinet Guide and Cabinet Manual, engaging and consulting with citizens is strongly recommended, and, in a number of acts, public consultation is a legislative requirement (e.g: the Local Government Actor the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act, etc). Furthermore, long-term insights briefings on key topics relevant for the future are a rather new foresight tool and public participation in policy development and is amongst the country’s main commitments in its national Open Government plan. New Zealanders can provide their feedback and make submissions to a bill, and they can also give local and central government inputs on plans through consultation listings before decisions are made. In addition, there are multiple recent initiatives to engage people and groups at the community level in both policy and service design (such as the programme to Regenerate Christchurch or the development of the Māori Strategy), which are supported by the Policy Community Engagement Tool developed and launched in December 2021 under the supervision of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Box 4.4). The recently released brief on the State of the Public Service stresses the development of active citizenship as a key focus of the New Zealand public service (Public Sector Commission, 2022[23]).

Box 4.4. New Zealand’s Policy Community Engagement Tool

The Policy Community Engagement Tool (the Tool) was first released and piloted in May 2021. It provides good practice guidance on community engagement for policy makers and agencies as they respond to the recommendations of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Terrorist Attack on Christchurch Masjidain.

The Tool advices public officials involved in the engagement activity on the steps, processes and resources that will enable them to undertake good community engagement, including a detailed checkbox guide (with critical questions, see Figure below) to ensure all key elements are considered. It encompasses all the necessary activities involved when carrying out engagement in five steps:

Step 1 – Designing the engagement

Step 2 – Planning the engagement

Step 3 – Managing the delivery of engagement

Step 4 – Analysing and sharing the results of engagement

Step 5 – Reviewing and evaluating the engagement

According to New Zealand’s self-assessment on the Open Government National Action Plan, this guidance is broadly used and has significantly increased web traffic and downloads by public officials during 2021.

Nevertheless, responsibility for public consultation lies with individual agencies are the ones responsible for public consultations as they liaise with stakeholders, communicate, keep records, etc. This fragmentation may hinder the systematic compilation of records and monitoring (providing summaries, registering who are the ones consulted and how often, etc), or the existence of a consistent approach to notifying stakeholders of upcoming opportunities to contribute (OECD, 2021[24]). Additionally, challenges and limits may arise related to actual implementation. For instance, during interviews carried out for this study, stakeholders mentioned timeliness as a challenge to meaningful engagement. Many reported that the first stage of engagement often takes place too late to influence policy outcomes. This, in turn, might undermine trust among those that interact with the government (OECD, 2021[24]).

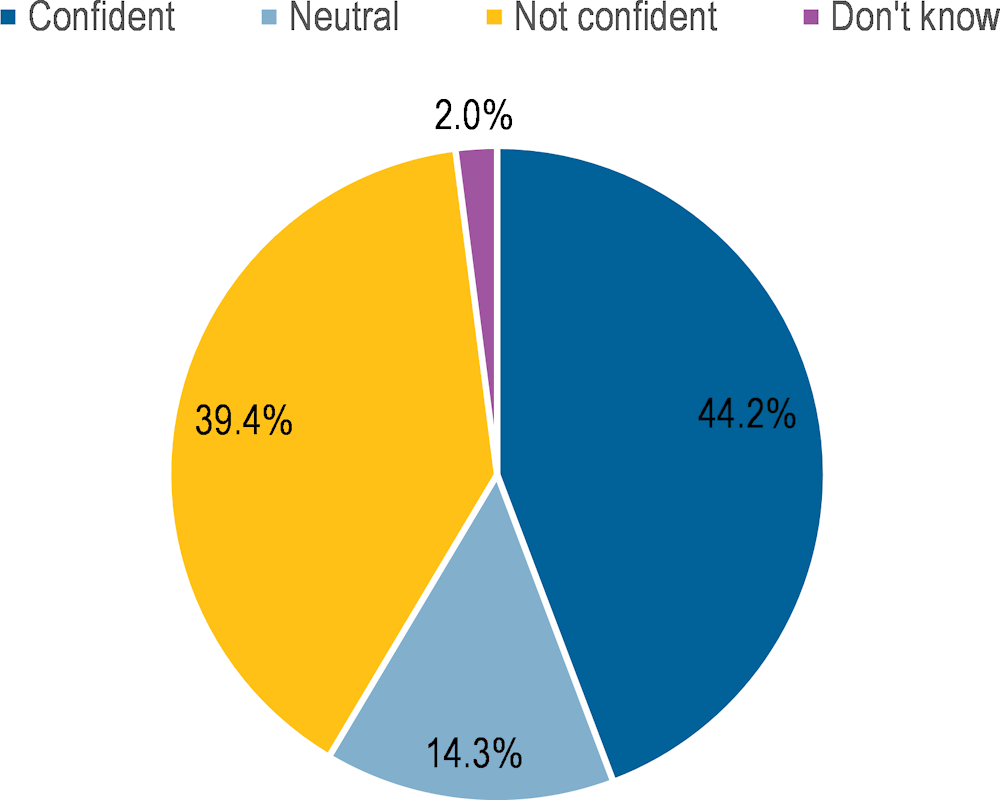

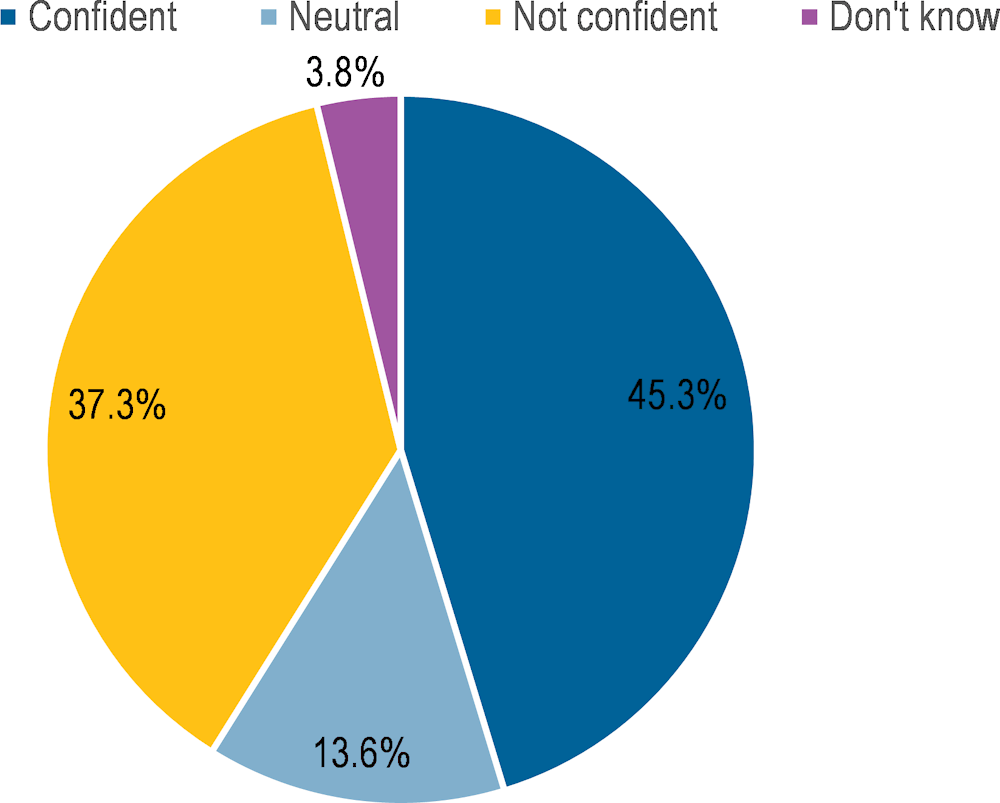

Figure 4.8. Less than half are confident that government institutions listen to citizens

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents responses to the question “How much confidence do you have in government institutions to: Listen to citizens” The “confidence” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “No confidence” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

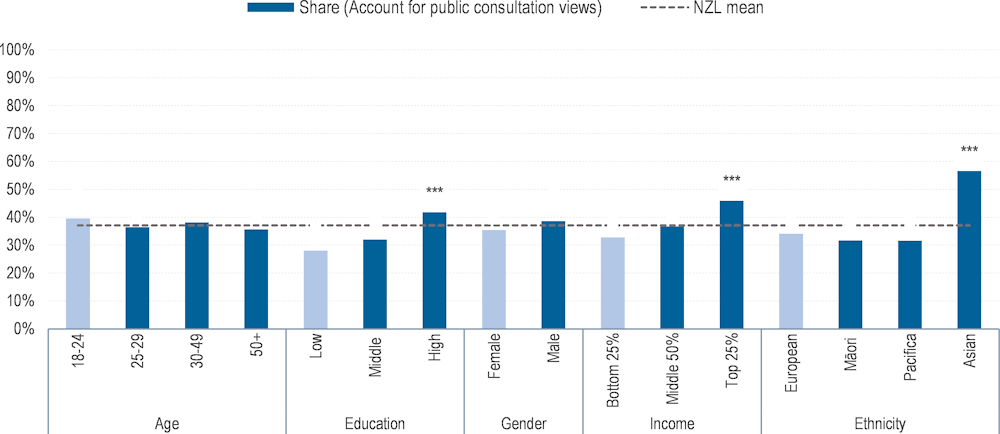

Other results support these points. Evidence from New Zealand’s Survey on Community Engagement in Policy making (2021) administered by policy advisors, community representatives and engagement specialists shows that timeframes for engagement are too short. Furthermore, according to the OECD Trust Survey, only a minority of New Zealanders (44%) are confident that government institutions listen to people (Figure 4.8). Even fewer respondents (37%) believe that if they participate in a public consultation the government would adopt the opinions expressed. Less educated New Zealanders are the most skeptical about the government being open and making policies including their concerns: fewer than 1 in 3 (28%) of those who completed lower secondary education believe the government would adopt opinions expressed in a public consultation (Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.9. New Zealanders with higher education, top 25% income and Asian population groups are more likely to believe that the government adopts opinions from public consultations

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents the responses to the question "If you participate in a public consultation on reforming a major policy area (e.g. taxation, healthcare, environmental protection), how unlikely or likely do you think it is that the government would adopt the opinions expressed in the public consultation?" The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “NZL mean” presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. Top 25% and bottom 25% refers to the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. High education is defined as the ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, and low education refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Other than providing inputs to government, citizens are not able to initiate legislation, and there are only very few instances of participatory or deliberative democracy. Public institutions promote top-down engagement opportunities, but people are not encouraged to participate on their own initiative. In fact, there are tools that facilitate access to members of parliament and for starting petitions. New Zealanders can also initiate (non-binding) referendums, and although this tool has barely been used since the Initiated Referendum Act (1993) and has many limitations (Morris, 2004[25]), it was found to have a positive impact on public trust (Qvortrup, 2008[26]; Morris, 2007[27]). In this regard, experiences from other OECD countries may suggest that more structured democratic innovations can be a good way to strengthen people’s political voice and reinforce trust, at least at the local level, where turnout levels are decreasing steadily, and there are no political parties (Box 4.5).

Box 4.5. Deliberative democracy Initiatives across OECD countries at the local level

Citizens’ Panel- Toronto Planning Review Panel (2015-2017)

The Toronto Planning Review Panel was a deliberative body, embedded into the city’s planning division, that enabled ongoing citizen input on the issues of planning and transportation. Its members served two-year terms, after which a new cohort was randomly selected to be representative of the Greater Toronto Area. A group of 28 randomly selected residents from all parts of the greater Toronto area met for 11 full-day meetings from 2015-2017. Prior to deliberation, participants met for four days of learning and training. A similar panel was appointed for the 2017-2019.

Planning Cell: A cable car for the citizens of Wuppertal, Germany (2016)

Forty-eight randomly selected citizens were brought together to discuss the possibility of building a cable car in their town. Citizens met for four full days and engaged in learning and deliberation. They listed arguments for and against the cable car and concluded by recommending the local government to conduct a thorough cost-benefit analysis and funding options before making a decision.

Citizens' Council on mobility in Vorarlberg, Austria (2018-2019)

The state government of Vorarlberg brought together 30 randomly selected citizens for one and a half days to develop principles and priorities in the field of mobility and transport for the state of Vorarlberg for the next ten to fifteen years. Following the Citizens’ Council, a Citizens’ Café took place, where the broader public could learn about the recommendations produced and discuss them with politicians and public administration.

Source: (OECD, 2020[28])

In this regard, addressing participation gaps and reaching out to people left behind may require a mix of solutions, and to this end, it is important to consider the specific context, as well as political socialisation, historic and cultural elements. For instance, during interviews it was mentioned that although Europeans consider the democratic ideal as “one person, one vote”, for Māori the idea behind democracy is that policies are collective.

A crucial starting point is to strengthen people’s self-perception of their ability to understand and participate in political processes. There is no form of participation that is enhanced when individuals feel unable to understand politics. Feeling that one can make a difference can lead to more active, effective engagement in politics and other areas of social life (Prats and Meunier, 2021[20]). The more people feel able to understand politics and have their voice heard, the more likely they are to pursue democratic endeavours (Gil de Zúñiga, Diehl and Ardévol-Abreu, 2017[29]) and the more they trust public institutions and are satisfied with democracies. New Zealand recognises that the young can play an important role in counteracting the political disengagement trend, and has developed initiatives such as the Youth Parliament, parliamentarians travelling to schools over around the country or the “Kids Voting Program”. These initiatives could benefit from other, broader activities that extend beyond civic duties or enrolment to strengthen political interest, such as the mock elections run in Norway (Box 4.6). This would also address most New Zealanders’ (83%) claim about the need to include learning about Parliament in the school curriculum.5

Box 4.6. Mock Elections and strengthening internal efficacy in Norway

Norwegians display the highest levels of internal political efficacy (i.e. people’s own ability to participate in politics) across OECD countries. This can be linked to the fact that Norway is the only country in the world where there is a national framework (and a 70-year tradition) to conduct mock elections in schools.

The exercise includes debates and interaction with party members from youth organisations - every other year, which is held one week before local or parliamentary elections. This familiarises students with the political realm and trains them to be active democratic citizens, which helps perpetuate the democratic system. A study on the impact of political education at schools in Norway showed that mock elections had a positive effect on students’ willingness to vote in parliamentary elections (Borge, 2016[30]).

In addition, comprehensive, regular and representative population surveys, such as the Kiwis Count and the OECD Trust Survey, may facilitate citizen engagement and allow the government to obtain updated feedback on people’s perceptions, experiences and evaluations of public governance and services, thus reinforcing vertical accountability beyond votes or electoral periods (OECD, 2022[31]). This may complement ongoing targeted initiatives that are designed to address specific communities, such as engaging through intermediaries, setting up conversations without a framework, and community leaders’ selecting priorities.

4.1.4. Opportunities to improve transparency and achieve meaningful engagement

This section summarizes key results and presents potential policy avenues to improve openness and strengthen public trust

New Zealand has put in place multiple initiatives to promote openness as an important value of public governance. Indeed, promoting transparency and opening the government to the public has been the cornerstone of the country’s successful strategy to tackle the pandemic. In particular, the daily briefings in which the Prime Minister and the Director General of Health directly addressed New Zealanders allowed them to establish trust with their audience through open and honest communication, inspire and motivate audiences, and establish a “duty of care” relationship through inclusive and empathetic communications (Beattie and Priestley, 2021[32]). It is possible to capitalize on these lessons and improve openness and transparency in the regular functioning of the administration.

Three-quarters of the population expect information to be easily available, and, indeed, New Zealand has put in place several law and initiatives to this end. Yet, whenever the information is not restricted, there are still challenges for some social groups to a, either because the information is presented in difficult-to-understand bureaucratic language, or because it is not proactively communicated There is room to promote more proactive disclosure of information.

In turn, the New Zealand government could go beyond the traditional understanding of transparency towards a new and broader communicational sense, which requires planning of how public information is going to be communicated and anticipating people’s needs to better arm them against mis- and disinformation. These plans include extending efforts to use plain language, such as the recently introduced plain language bill; setting goals; targeting audiences and messages; and identifying best channels to reach different population groups

The news media is the least trusted institution in New Zealand, with only 35% of the population trusting it. The country also fares at the low end of the benchmarking countries in this area. There is room to develop a holistic approach to counter the spread of mis- and disinformation. Ways to do this include promoting diverse, independent and quality media; supporting media and digital literacy; considering transparency requirements and issues related to the business models of social media platforms; and exploring other ways to strengthen the information ecosystem. Any initiatives in this area will need to directly tackle difficult issues such as existing financial incentives social and some conventional media companies to facilitate the spread of misinformation and the potential trade-offs implicit between halting the spread of misinformation and protecting fundamental values such as freedom of speech.

New Zealand needs also to enhance political representation and proactively reach out to people who feel left behind, preventing participation gaps from becoming structural political inequalities. This will require the country to keep investing in and improving initiatives related to political socialisation and outreach to specific segments of the population, such as the young, the less educated, Māori or citizens from the Pacifica communities. These initiatives should be put in place on a regular basis, beyond specific policies or reforms. Furthermore, even though specific agencies are responsible, results from the exercises should be shared in broad national dialogues and lessons from the communities’ experiences should be made public in a co-ordinated manner, in order to promote institutional inclusion and nation-wide learning.

Less than half of New Zealanders expect to be consulted on issues affecting their community and only 37% expect that the views expressed by people in public consultations will be adopted. New Zealand should ensure that opportunities for citizens’ engagement are meaningful and broad - including instances for deliberation and participation, especially at the local level - so that people perceive a sincere invitation to inclusive policy making. This type of engagement goes beyond the more procedural mentality of consultations, by involving people during early stages of policy making, when problems and potential solutions are being identified, and responding to and using the inputs they provide in the development of regulations.

4.2. Integrity

Public integrity refers to the consistent alignment of, and adherence to, shared ethical values, principles and norms for upholding and prioritising the public interest over private interests in the public sector (OECD, 2017[33]). Promoting public integrity and preventing corruption is crucial to building people’s confidence in government and public institutions. Inversely, corruption implies abusing the trust that has been placed in a public duty. By definition, corruption erodes trust in public institutions. Indeed, research in European countries shows a strong correlation between perceptions of corruption and lower levels of trust (Mungiu-Pippidi, 2015[34]).A recent study of 173 European regions found that the absence of corruption – i.e. citizens expect their public officials to act ethically – was the strongest institutional determinant of citizens’ trust in the public administration (Van de Walle and Migchelbrink, 2020[35]).

The OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions considers integrity in relation to the government’s mandate to use powers and public resources ethically, by upholding high standards of behaviour, committing to fight corruption, and promoting accountability. In the case of New Zealand, the survey includes two specific questions on perceptions of petty corruption, as well as political influence (and horizontal accountability among branches of government):

If a government employee was offered money by a citizen or a firm for speeding up access to a public service, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that they would refuse it?

If a court is about to make a decision that could negatively impact the government’s image, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that the court would make the decision free from political influence?

4.2.1. New Zealand is perceived as society with low levels of corruption

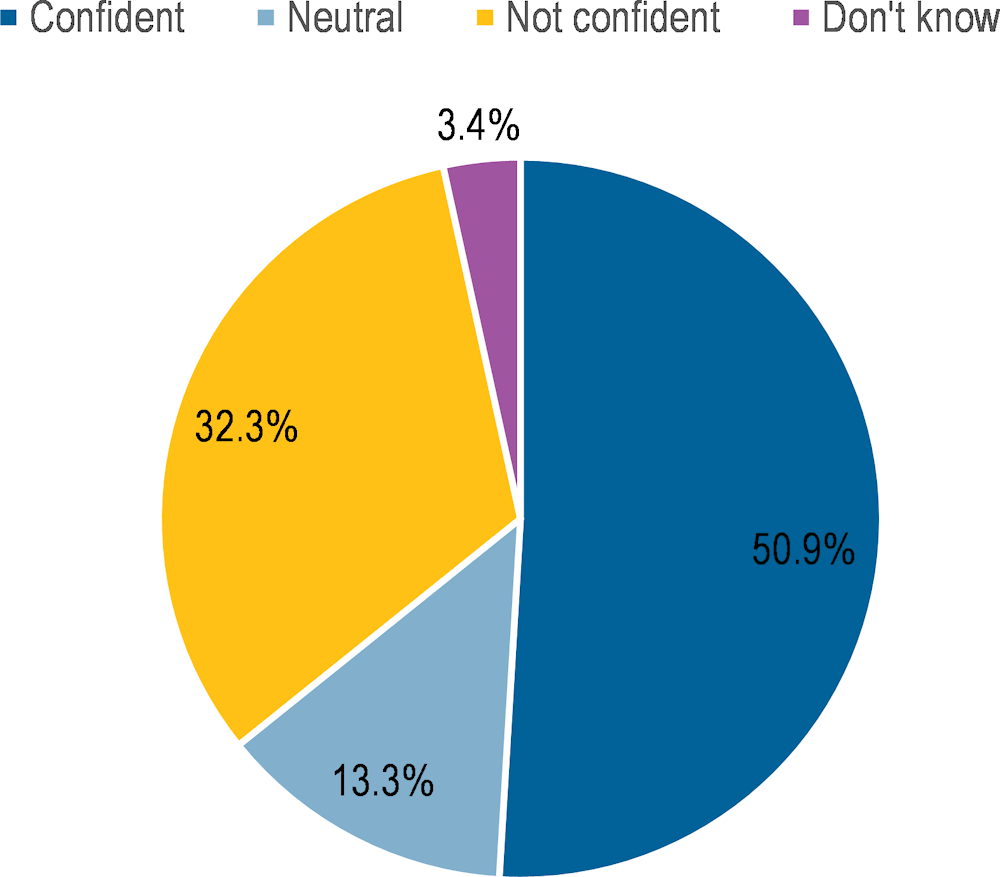

According to major institutions and indexes, New Zealand is one of the least corrupt countries in the world and experts’ assessments report that members of the executive or their agents would never, or hardly ever, grant favours in exchange for bribes, kickbacks, or other material inducements.6 Law enforcement is effective, institutions and regulations are transparent, and a comprehensive legal framework is in place to combat corruption and sanction corrupt practices (GAN Integrity, 2020[36]). The country has historically ranked amongst those with the lowest levels of perceived corruption, equalling Denmark and Finland, and around one in two New Zealanders believe that institutions will use power and resources ethically (Figure 4.10).

Figure 4.10. About half of New Zealanders believe that power and resources will be used ethically

Note: Figure presents responses to the question “How much confidence do you have in public institutions to use power ethically” The “confidence” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “No confidence” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

In practice, there are very few corruption cases, and as per regular surveys carried out by the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), they do not seem to have influence trust. The percentage of people who agree or strongly agree to trust the SFO has increased steadily since 2012, and New Zealand’s biggest bribery scandal - the Auckland’s Road Maintenance Case, in which six people were charged in relation to alleged corruption - has not affected this figure; on the contrary, it is seen as an exemplary, fairly handled case.

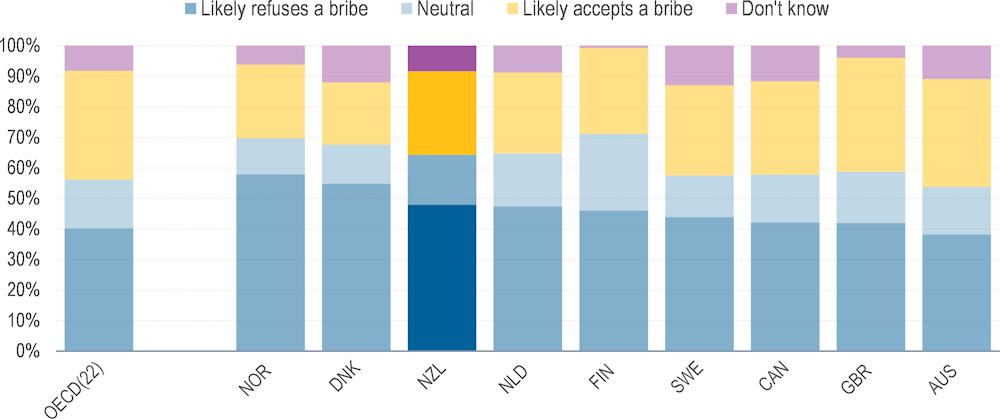

Despite this, results from the OECD Trust Survey show that less than half of survey respondents report believing that courts would act free from political influence (43.9%) (Figure 4.11) and over a quarter the population believe that public employees would accept money offered to speed up access to public services (27%) (Figure 4.12). Although this result still leaves New Zealand below the OECD average-and near the bottom of the OECD for whether a public servant would accept a bribe, it nevertheless contrasts with other sources that provide better assessments about the absence of corruption. This might reflect scepticism about public integrity not picked up elsewhere, but is also difficult to rule out some degree of survey specific bias. Because variables of the integrity dimension, were found to have a statistically significant effect of people’s trust in the public service and parliament (Figure 2.18 and 2.19) developing better understanding of this result should be of importance to the New Zealand public service.

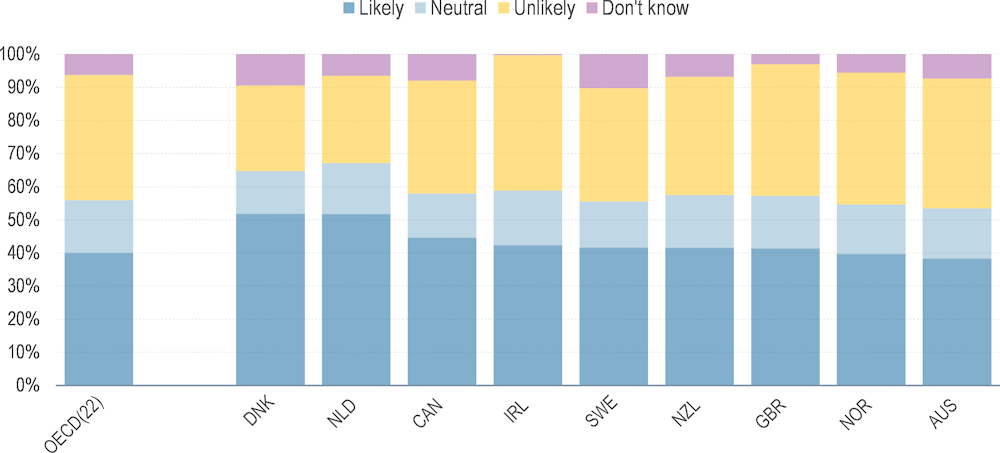

Figure 4.11. Less than half of the population expect courts to take decisions free from undue influence

Share of respondents in New Zealand, selected countries and OECD average, 2021

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question "If a court is about to make a decision that could negatively impact on the government’s image, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that the court would make the decision free from political influence?” The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; "neutral" is equal to a response of 5; "unlikely" is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and "Don't know" was a separate answer choice. Finland and Norway are excluded from the figure as the data was not available. OECD(22) refers to the unweighted average across 22 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

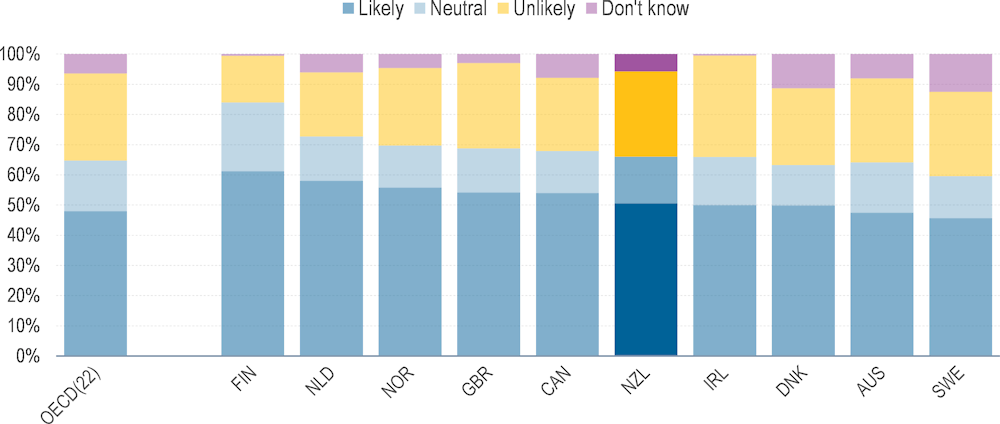

Figure 4.12. A third of New Zealanders believe that a public employee would refuse a bribe

Share of respondents in New Zealand, selected countries and OECD average, 2021

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question "If a public employee were offered money by a citizen or a firm for speeding up access to a public service, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that they would refuse it? ". The "Likely accepts a bribe" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; "neutral" is equal to a response of 5; "Likely refuses a bribe" is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and "Don't know" was a separate answer choice. "OECD" presents the unweighted average across countries. Finland's scale ranges from 1-10 and the unlikely / neutral / likely groupings are 1-4 / 5-6 / 7-10. In Norway and Finland, the question was asked in a slightly different way. In Norway, "If a member of the Storting were to be offered a bribe or other benefit in return for exercising their influence on a parliamentary matter, how likely are they to accept it?" and in Finland, "If a parliamentarian were offered a bribe to influence the awarding of a public procurement contract, do you think that he/she would refuse the bribe?". OECD(22) refers to the unweighted average across 22 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

These findings could be linked to an uneven distribution of perceptions of risk of undue influence and corruption at the central and local level (further addressed in next section), rather than to broader evaluations of the public service. Indeed, most respondents (61%) of the OECD Trust Survey also reported that the integrity of people working in government strongly influenced their trust in public institutions (Figure 2.4). This may be because New Zealand has a long-established merit-based civil service, and the recent Public Service Act (2020) includes merit-based appointments amongst its five key principles of the public service. Indeed, public employees are recruited based on advertised positions and skills and must adhere in their daily work to core values and standards that guide the public service. This is a fundamental component of any public sector integrity system (Charron, Dahlström and Lapuente, 2016[37]; Charron et al., 2017[38]), as a culture of integrity cannot be achieved without a skilled and motivated civil service, committed to the public’s interests, and delivering value for money for citizens.

Cynical perceptions on public integrity can be also related to a corruption-focused narrative guiding most of New Zealand’s initiatives on the issue. Perhaps because of its high levels of trust as well as low levels of corruption, most of country’s efforts have been concentrated on tackling and sanctioning undue behaviour, instead of investing in prevention, such as specific training or risk management of integrity issues. This approach, which has been possible because of a strong culture of ethics and a trust-based public service, is currently turning towards initiatives to preserve and strengthen integrity.

According to OECD’s Recommendation on Public Integrity, providing training to build capacities and equip public officials to manage integrity issues that may appear in their daily work is crucial to reinforce a culture of integrity. In this regard, relevant training experiences from OECD countries - in terms of timing, target, frequency, etc. - could be useful to take into account in New Zealand (Box 4.7).

Box 4.7. Integrity training experiences in OECD countries

Austrian’s Advance training course on Corruption related issues

The Federal Bureau of Anticorruption (BAK) in Austria put in place advanced training courses on all corruption-related topics, exploring the psychological background of the corruption phenomenon and addressing the possibilities of general and individual corruption prevention. The courses make references to the whole legal framework and are intended to be accompanied by a course book with a theoretical but also very practical approach, including generally applicable teaching content as well as specific innovations in research on corruption.

Explicit attention has been paid to enabling readers to concretely apply the content to themselves and their organisational units: readers can answer specific guiding questions and evaluate them using a scoring system. Based on the score obtained, the book offers ready-made solutions for preventing and combating corruption. Furthermore, the BAK course book contains case studies on corruption with practical solutions to prevent the (real) cases described, aiming to reinforce readers’ own room for manoeuvre.

Ethics training in Flanders, Belgium

The Flemish Agency for Government Employees provides public officials with practical training that is not focused on the traditional communication of dispositions and guidelines, but instead presents dilemmas officials may face in their daily activities. Public officials are given practical situations in which they confront an ethical choice and where it is not clear how they might resolve the situation with integrity. The facilitator encourages discussion among the participants about how the situation could be resolved in order to explore the different choices. The debate over the possible courses of action, rather than the solution, is the most important element, as it helps participants to identify different opposing values. Based on objectives and targets of specific groups or entities, the dilemmas presented could cover the themes of conflicts of interest, ethics, loyalty or leadership, among others

Source: Annual Report 2020, Federal Bureau of Anticorruption, Ministry of Interior, https://www.bak.gv.at/en/Downloads/files/Annual_Reports/BAK_Jahresbericht_2020_ENG_converted.pdf ; (OECD, 2019[39])

Additionally, including integrity aspects in risk management could be relevant to support New Zealand’s changes. Internal control and risk management policies reduce the vulnerability of public sector organisations to fraud and corruption, while ensuring that governments are operating optimally to deliver programmes that benefit citizens (OECD, 2020[40]). Efforts to audit and monitor different agencies could be strengthened by embedding integrity objectives into existing internal control and risk management policies and practices, informing risk definition with updated evidence (e.g. by regular surveys), and by identifying high-risks areas, as many OECD countries do (Box 4.8).

Box 4.8. Estonia’s approach to integrity risks and control

The Estonian government’s 2013-2020 Anti-Corruption Strategy recognised shortcomings in specific domains related to corruption prevention and risk mitigation, and recommended actions to remedy these challenges, stipulating that the ministry responsible for the specific area in question (e.g. health or the environment) should also be responsible for implementing subject-specific corruption prevention measures.

To target high-risk areas, the government of Estonia established domain-specific anti-corruption networks. Each ministry has a corruption prevention co-ordinator who is meant to manage the implementation of the anti-corruption policy in the relevant ministry and its area of government. The co-ordinators form the anti-corruption network – the network convenes annually around four to five times. The network also includes representatives from police, civil society, parliament, the state audit office and other stakeholders who are invited, depending on the topic chosen. There is also a network of healthcare authorities to discuss developments in their respective areas, as well as issues to resolve.

Source: (OECD, 2020[40])

4.2.2. There are concerns regarding personal networks and unbalanced influence of some interests over the public good

Beyond corrupt practices that are criminalised and sanctioned, such as active and passive bribery, there are other, more subtle activities that are not necessarily illegal but may steer public decision making away from the public interest. These may include using personal connections to influence policy, or providing decision makers with biased or manipulated data, for example.

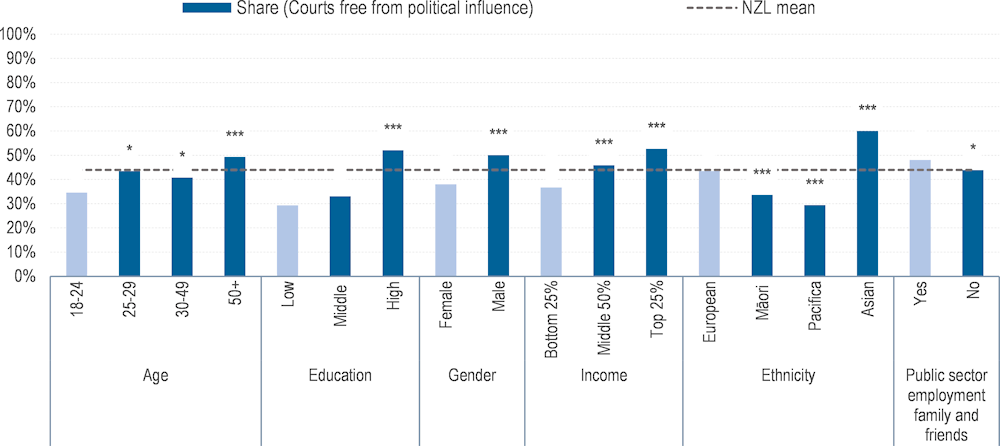

According to a report prepared by the Institute of Governance and Policy Studies at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand may suffer from ‘cosy-ism’, defined as a high degree of overly cosy relationships between members of a small society (Rashbrooke, 2017[41]). This implies that close relationships built by educational, cultural and political socialisation may influence (and bias) political decisions and appointments, translating economic or educational disparities into unequal opportunities and power over politics. Indeed, evidence from the OECD Trust Survey shows that only 29% of respondents reporting the lowest levels of education believe courts would make decisions free from political influence, and the percentage increases to 52% among those with highest levels of education (Figure 4.13).

Figure 4.13. Vulnerable groups perceive integrity of political courts negatively

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents the responses to the question "If a court is about to make a decision that could negatively impact on the government’s image, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that the court would make the decision free from political influence?" The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “NZL mean” presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. Top 25% and bottom 25% refers to the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. High education is defined as the ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, and low education refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

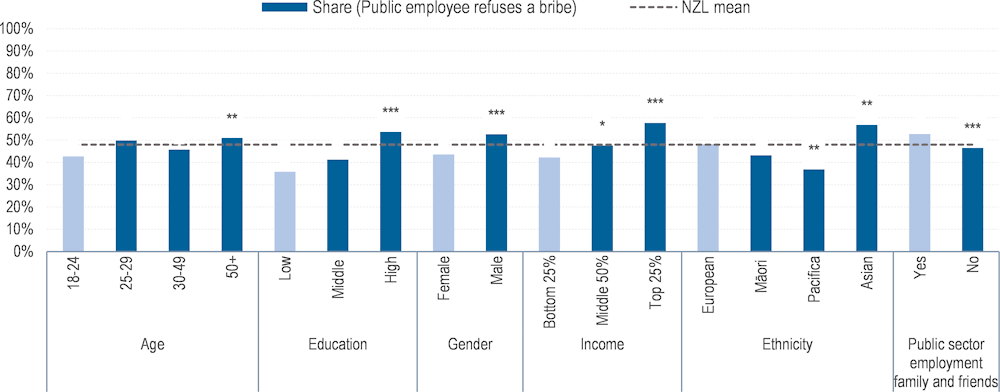

Figure 4.14. Respondents with relationships in the public sector have positive views on integrity

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021

Note: Figure presents the responses to the question "If a public employee were offered money by a citizen or a firm for speeding up access to a public service, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that they would refuse it?" The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “NZL mean” presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. Top 25% and bottom 25% refers to the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. High education is defined as the ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, and low education refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

In addition, 37% of respondents from the OECD Trust Survey have family members or friends who work or have worked in the public sector. Not surprisingly, those who reported to have a closer connection with the public sector are also those who present better integrity perceptions (Figure 4.14).Although half of New Zealanders are confident that institutions would use power or resources ethically, one in three (34%) reported cynical expectations about government institutions acting in the best interest of all.

Taking into consideration the above, New Zealand could pursue some initiatives to ensure policies are made in the public interest, and to preserve the integrity of interaction and stakeholder engagement during policy making, accompanied with proper communication of these initiatives. These include requiring disclosure of stakeholders’ names and the activities they carry out if they intend to influence policies or requiring parliamentarians to make their agendas transparent and open to the public. Furthermore, New Zealand could reopen discussions on developing lobbying regulations, currently inexistent. Such dialogue should be open to the broader society and consider different concerns, challenges and interests, following the example of discussions carried out by Ireland when designing its lobbying regulations (Box 4.9).

Box 4.9. Ireland regulations on Lobbying

The Irish regulations on lobbying were developed informed by a wide consultation process that gathered opinions on its design, structure and implementation, based on OECD Recommendation on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying.

2015 Regulation of Lobbying Act is simple and comprehensive: any individual, company or NGO that seeks to directly or indirectly influence officials on a policy issue must list themselves on a public register and disclose any lobbying activity. The rules cover any meeting with high-level public officials, as well as letters, emails or tweets intended to influence policy.

According to regulation a lobbyist is anyone who employs more than 10 individuals, works for an advocacy body, is a professional paid by a client to communicate on someone else’s behalf or is communicating about land development is required to register themselves and the lobbying activities they carry out.

In addition to the law, on 28th November 2018, the Standards in Public Office Commission launched its Code of Conduct for persons carrying on lobbying activities. It has come into effect on 1st January 2019, and will be reviewed every three years.

Source: Regulation of Lobbying Act and website https://www.lobbying.ie/

In addition, in interviews conducted for this study, it was highlighted that concerns about personal networks and policy outcomes were higher with respect to institutions at the local level. Subnational units and institutions are not necessarily affected by central government integrity policies and initiatives; moreover, officials may not be sufficiently trained to identify and prevent undue practices. In this regard, it could be relevant to consider establishing a Public Service Commissioner for the local level, responsible for ensuring coherence with national integrity efforts and policies, as well as for dealing with integrity issues at the local level. A good example that could be a relevant starting point is the experience of the French integrity advisors (Box 4.10).

Box 4.10. Integrity advisors in France

According to French regulations (Law on Ethics and the Rights and Obligations of Civil Servants, 2016) every public official has the right to access to integrity advice, and every public organisation is required to appoint an ethics officer (référent déontologue). These ethics officers have the mission to advise civil servants on questions they may have regarding their integrity obligations in the course of their duties. This requirement has also spread to other levels of government, with an increasing trend of ethics officer appointments in regions and major French cities.

The référent déontologue of the territorial civil service management centre of the Rhône and Lyon métropole published its first activity report in May 2019 highlighting trends in advice and guidance provided to public officials. Guidance recalls for instance in which cases a secondary activity can be pursued and how to proceed in such cases, and reasons why a future private function may impact the functioning of the former organisation and services if the functions are close to the ones that were performed by the public official. A selection of anonymised cases is annexed to the report. It is worth noting that this ethics officer also acts as a whistleblowing focal point for the same jurisdiction.

Source: (OECD, 2020[40])

Perceptions of vested interests influencing politics also extend to political finance (Transparency International NZL, 2019[42]). Democracy and politics need money to survive. However, if funding is not regulated, it can unbalance political competition and generate or exacerbate inequalities. According to a survey carried out by the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, only one out of four New Zealanders trust the way in which political parties are funded (Chapple and Anderson, 2021[43]), and there are some rules regarding reporting and monitoring that need to be better defined. In New Zealand, there is no ban on donations from foreign interests or from companies with ongoing contracts with the government. In turn, not all donors are required to report on their donations to political campaigns (IDEA, 2022[44]). Unregulated political finance presents clear risks related to funding sources and its legal status, as well as loopholes in regulations could leave room to privilege private interests biasing political competition. In this regard, experiences aiming to make political finance more transparent and easy to monitor can be relevant to consider and implement in the country (Box 4.11). (Transparency International NZL, 2019[42]) (IDEA, 2022[44])

Box 4.11. Transparency and accessible information on political finance in the United States

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) obliges political committees to submit financial reports to the Federal Election Commission (FEC), which in turn makes them publicly available in person at the FEC offices in Washington, DC or online. The FEC has developed detailed standard forms to be used, requiring, among other things, precise information concerning contributions, donors, disbursements and receivers. All contributions to federal candidates are aggregated based on an election cycle, which begins on the first day following the date of the previous general election and ends on the election day, whereas contributions to political parties and other political committees are aggregated on a calendar year basis.

The intensity of the reporting may differ. For example, a national party committee is obliged to file monthly reports in both election and non-election years; a principal campaign committee of a congressional candidate must file a financial report 12 days before and another report 30 days after the election in addition to quarterly reports every year. The FECA prescribes that the financial reports are to be made public within 48 hours; however, in most cases, the FEC manages to make reports available online within 24 hours.

Source: Federal Election Commission, www.fec.gov/

4.2.3. Opportunities to reinforce the integrity system

This section summarizes key results and presents potential policy avenues to improve integrity and strengthen public trust.

Public service and public officials in New Zealand are generally perceived as being honest and devoted to the public interest. They work on a trust basis and follow high standards of behaviour that are historically and culturally rooted. However, there is room to improve and better preserve integrity as a guiding principle and foundation of the public administration. New Zealand could also continue to take a more preventive integrity approach, investing more in training beyond awareness-raising, and including integrity elements in risk management and internal control. These efforts could be part of a comprehensive national integrity strategy, co-ordinated at the central government, but accompanied by integrity initiatives at the local level, aiming to bridge gaps and avoid legal loopholes.

In addition, to improve perceptions of political integrity and shield public policies from undue influence, New Zealand could reopen discussion on developing lobbying regulations, as well as tighten political finance laws by defining clearer targets and broadening the scope of transparency requirements and bans. There is also a need to examine how potential conflicts of interest are managed at the local government level where personal links may influence resource management decisions. While these links are inevitable in a small country, approaches to managing them more transparently could enhance perceived integrity.

4.3. Fairness

While no individual value can summarise an entire society, it is commonly noted that the notion of “fairness” plays a similar role in New Zealand society to that played by “freedom” in the United States or the trio of “liberté, egalité, fraternité” in France (Fischer, 2012[45]; Levine, 2022[46]). This is reflected both in popular culture and in civil society. In popular culture, the phrase “fair enough” is a common response in conversation. New Zealand’s second-longest running television show is “Fair Go” (first aired, 1977) which focuses on investigative journalism and consumer affairs. At the more formal level, the 1985 Royal Commission on the Electoral System listed fairness as the first of 10 criteria for evaluating electoral systems, while the Inland Revenue Department (responsible for tax) uses the phrase “it’s our job to be fair”.

Perhaps influenced by the focus on fairness, and perhaps also reflecting how New Zealand’s national narrative has evolved, many of the main historical milestones celebrated in New Zealand can be linked to the idea of fairness. The Treaty of Waitangi – New Zealand’s founding document signed in 1840 – can be seen in terms of fair treatment by the British Crown establishing that Māori have the rights and privileges of British subjects (article 3) and equal protection of Māori property rights (article 2), although differences in English and Māori versions and their interpretation may have blurred that sense of fairness . In turn, New Zealand celebrates its status as the first self-governing country in the world to grant women the vote in 1893, a milestone in political fairness.

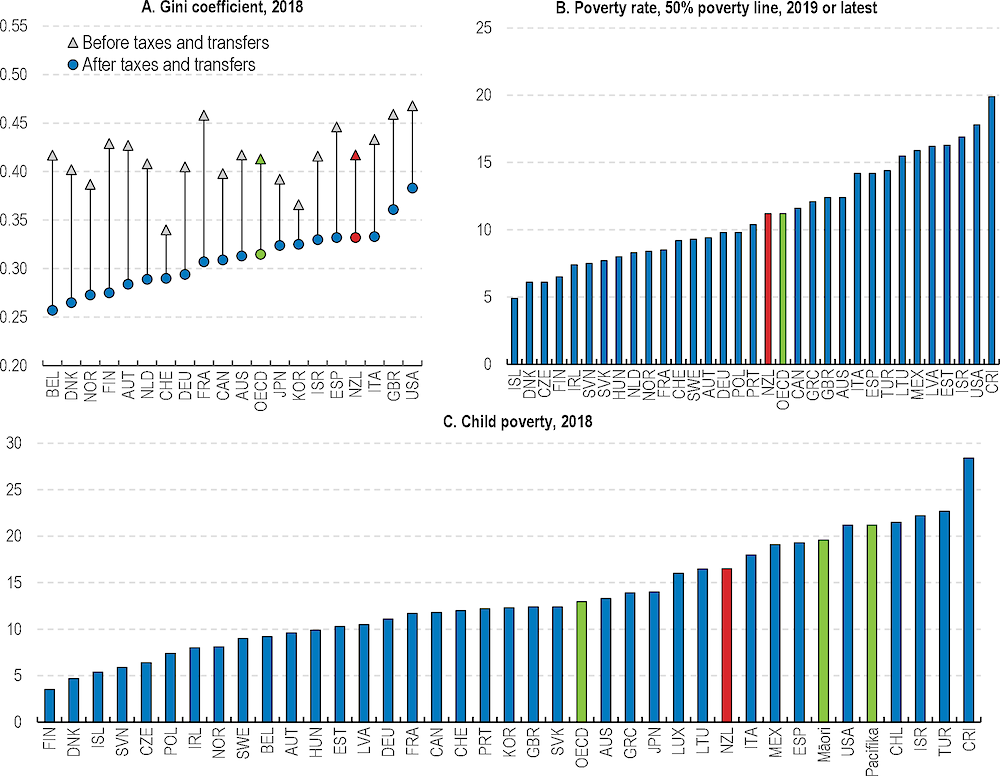

Achieving fairness remains a crucial issue, as disposable income inequality in New Zealand is higher than the OECD average despite market income inequality being around the OECD average, owing to below-average redistribution through taxes and transfers (OECD, 2022[47]). Progressing towards an even fairer society requires redressing structural trends affecting vulnerable groups, in particular as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in these groups are still not fully visible.

The OECD framework on the drivers of trust defines fairness as having two components: improving living conditions for all and providing consistent treatment to people and business regardless of their background and identity. To capture aspects of fairness, the survey implemented in New Zealand included three questions on the fairness dimension:

If you or a member of your family apply for a government benefit or service (e.g. unemployment benefits or other forms of income support), how unlikely or likely do you think it is that your application would be treated fairly?

If a government employee interacts with the public in your area, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that they would treat all people equally regardless of their gender, sexual identity, ethnicity, or country of origin?

If a government employee has contact with the public in the area where you live, how unlikely or likely is it that they would treat both rich and poor people equally?

4.3.1. Despite high levels of institutional trust, New Zealanders have mixed views on the fairness of institutions

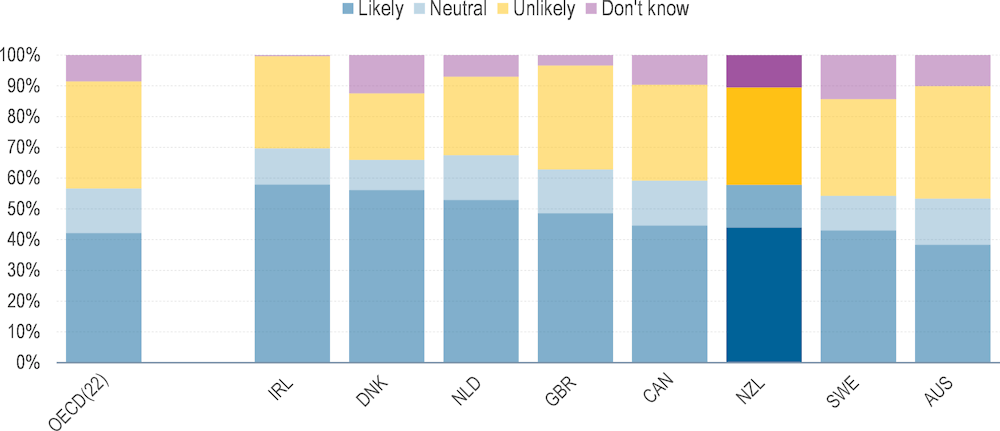

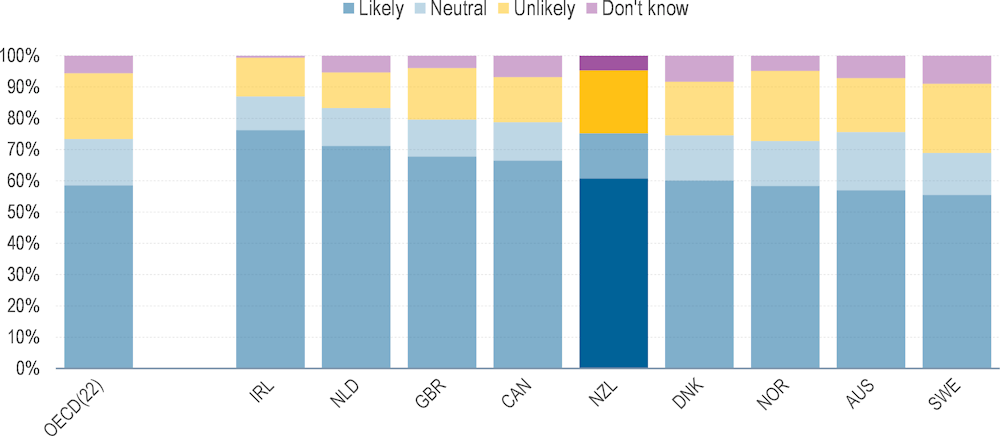

Compared to similar OECD countries, perceptions of the likelihood of fair treatment from public institutions in New Zealand is around the OECD average. Figure 4.15 shows that the proportion of people believing that it is likely that someone applying for a government service or benefit would be treated fairly is below that for Ireland, the Netherlands, Canada, or Great Britain, although higher than for Denmark, Norway, Australia, or Sweden. At first glance, this might suggest that fairness should be an area of at least some concern for New Zealand government institutions. However, some care should be applied when interpreting the data. In particular, of the four countries in the chart with levels of institutional trust similar to or better than New Zealand, three report lower levels of perceived fairness (Denmark, Norway, Sweden). One interpretation of this otherwise counter-intuitive result is that countries with higher expectations of fairness from government institutions both judge institutional performance more harshly, but also generally have more trustworthy institutions as a result.

Figure 4.15. A majority expects to be treated fairly

Share of respondents who indicate different levels of perceived likelihood that application for government services or benefits would be treated fairly in New Zealand, selected countries and OECD average (on a 0-10 scale), 2021

Note: Figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If you or a member of your family would apply for a government benefit or service (e.g. unemployment benefits or other forms of income support), how likely or unlikely do you think it is that your application would be treated fairly?“. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. In Norway, the question was formulated in a slightly different way. Finland is excluded from the figure as the data were not available. OECD(22) refers to the unweighted average across 22 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

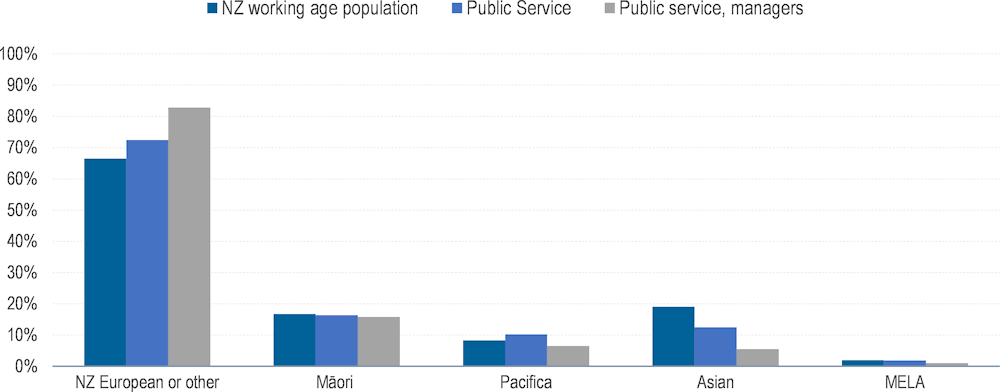

Figure 4.16 looks at how the perceived likelihood that someone applying for a government service or benefit would be treated unfairly varies across different demographic groups. While there is some variation in perceived fairness across age groups (with younger age groups being less likely to expect fair behaviour) and income (with low and middle income groups being less likely to expect fair behaviour) the largest differences in expectations of fairness are among different ethnic groups. People identifying as Māori or Pacific are much less likely to indicate that they believe an application for government benefits or services would be treated fairly. Interestingly perceptions of fairness are lower among the Pacific population (43%) than for Māori (49%). At the other extreme, Asian New Zealanders are more likely than other population groups to hold expectations of fair treatment (69%).

Figure 4.16. Perceived likelihood that application for government services or benefits would be treated fairly is lower among the young, women, Māori and Pacific communities

Share of respondents in New Zealand, 2021