Shifting towards more sustainable tourism and embracing digitalisation are the largest short- and medium-term challenges the tourism sector faces. Sustainable tourism involves implementing practices that minimise environmental impact ranging from carbon footprint mitigation to conservation of natural areas, such as forests and oceans. Diversifying tourism opportunities may help to address overtourism and ecosystems stress in any one region. Furthermore, tourism operations should promote linkages between tourism and other sectors and seek to minimise economic distortion or disruption. Digitalisation will further these goals by opening avenues such as virtual travel, smart tourism and the growth of MSMEs, but cost and knowledge barriers remain. Expansion of ICT infrastructure, ICT training and implementation cost support, and the development of robust and dynamic cybersecurity legislation are key priorities in this regard.

Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2023

Chapter 4. Strengthening sustainable tourism and accelerating digitalisation

Abstract

Introduction

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the future of tourism in Emerging Asia is moving towards deeper integration into the green and blue economies alongside rapid digitalisation. This trend is, among others, driven by the impacts of climate change and the increasing importance of sustainable and green tourism, as well as the role of digitalisation and technology in the travel and tourism industry.

Despite the many challenges faced by the world and the industry due to the COVID-19 pandemic, lessons learned from the pandemic present an opportunity for tourism stakeholders to re-evaluate the tourism and hospitality sector by adopting more sustainable practices. Different forms of tourism development have led to an unequal distribution of economic benefits and overexploitation of resources, and there is a growing discussion on beach resort development in Southeast Asia. Visitor management strategies are needed for sustainability and tourism should be diversified, with ecotourism as well as community-based approaches in ethnic and indigenous tourism. Meanwhile the increasing use of digital technology in travel and tourism, spurred by pandemic restrictions and health concerns, requires the attention of policy makers. Issues in Emerging Asia include cybersecurity, digital skills gaps and a lack of harmonised tourism statistics.

This chapter analyses the challenges on the road towards achieving sustainable tourism, as well as the role of the digital economy in the travel and tourism sector. Based on the analysis, the chapter presents recommendations for policy makers on making tourism more sustainable and capitalising on digitalisation.

Towards sustainable tourism

Overtourism and environmental degradation

There are many different definitions of sustainable development. Most experts tend to agree that it includes diverse pillars (UNEP and UNWTO, 2012) (Box 4.1). The Sustainable Travel Report 2022 by Booking.com found that 81% of global travellers see sustainable travel as important, with 50% stating that recent news about climate change has influenced them to travel more sustainably (Booking.com, 2022).

The G20 Rome guidelines for the future of tourism emerged in 2021 as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4.1). They provide an overview of key issues affecting the tourism industry and how policy makers can respond to these issues effectively. The guidelines have three broad objectives: restoring confidence and enabling recovery; learning from the experience of the pandemic; and prioritising a sustainable development agenda in guiding future tourism. These objectives are embedded in seven inter-related policy areas: i) safe mobility; ii) crisis management; iii) resilience; iv) inclusiveness; v) green transformation; vi) digital transition; and vii) investment and infrastructure. The guidelines were prepared by the OECD on behalf of, and in consultation with, the Italian presidency of the G20 (OECD, 2021).

Box 4.1. Definition of sustainable tourism

Sustainable tourism development guidelines and management practices are applicable to all forms of tourism at all types of destinations, including mass tourism and the various niche tourism segments. Sustainability principles refer to tourism development’s environmental, economic and sociocultural aspects.

Thus, sustainable tourism should:

make optimal use of environmental resources that constitute a key element in tourism development, maintaining essential ecological processes and helping to conserve natural resources and biodiversity

respect the sociocultural authenticity of host communities, conserve their built and living cultural heritage and traditional values, and contribute to intercultural understanding and tolerance

ensure viable long-term economic operations, and distribute socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders, including stable employment, income-earning opportunities and social services for host communities; and contribute to poverty alleviation.

Source: UNEP and UNWTO (2005), Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers, https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284408214.

Table 4.1. G20 Rome guidelines for action

|

Policy area |

Guideline actions |

|---|---|

|

Safe mobility |

|

|

Crisis management |

|

|

Resilience |

|

|

Inclusiveness |

|

|

Green transformation |

|

|

Digital transition |

|

|

Investment and infrastructure |

|

Source: OECD (2021), “G20 Rome guidelines for the future of tourism: OECD Report to G20 Tourism Working Group”, OECD Tourism Papers, No. 2021/03, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d11080db-en.

Nonetheless, the environment is often perceived as a resource to be exploited. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, popular coastal tourist destinations in Emerging Asia, such as Bali (Indonesia), Goa (India), Hainan Island (China), Phuket (Thailand), or Sihanoukville (Cambodia) received growing numbers of visitors, whose presence and activities had a negative impact on the local environment and communities. The harm included immense waste generation, the expansion of uncontrolled tourism resorts and infrastructure, and damage to marine ecosystems. Severe problems of overtourism and degradation of the environment could lead to temporary closure of the tourist destinations (Box 4.2).

As part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, some tourist destinations across Emerging Asia were closed for extended periods. Various reports have shown that wildlife and natural environments began recovering in the absence of visitors. In India and Thailand, nesting turtles were observed at undisturbed beaches, while in waters off Hong Kong, China, Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins returned (Spenceley, 2021).

Box 4.2. Temporary closure of popular coastal tourist destinations

Problems of overtourism and degradation of natural resources on the Philippines’ Boracay island and at Thailand’s Maya Bay led to government decisions in 2018 to close these popular destinations temporarily. Maya Bay, for example, received 5 000 tourists per day and up to 100 motorised boats could be counted simultaneously (Cripps, 2022). Tourists walked on reefs and corals, and boats slammed their anchors into the sea. Boracay, which welcomed 2 million visitors in 2017, reported severe sewage issues, and its beachside waters developed algal bloom, an indicator of pollution and bad water conditions. The closure of an entire tourist destination was a relatively uncommon approach prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. While such shutdowns can help the environment to recover, they also lead to the loss of jobs and revenue, strongly affecting small businesses and poorly-protected informal workers. The tourism shutdown of Boracay affected more than 30 000 employees in the hospitality and tourism industry, including an estimated 17 000 informal workers.

The reopening of Boracay began in late 2018 and was implemented in phases, with restrictions on visitor numbers and new visitor management regulations:

Table 4.2. Initiatives following the reopening of Boracay

|

Target |

Initiative |

|---|---|

|

Tourists |

A quota limited tourist arrivals to 6 400 per day, with a maximum of 19 200 visitors allowed on the island at any one time; new regulations were issued to manage tourist behaviour, for example prohibiting smoking and alcohol on the island’s most popular beach; hotel reservations are required before tourists can enter the island. |

|

Hotels |

In order to reopen, all hotels had to be compliant with the requirements of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and the Department of the Interior and Local Government; to be accredited by the Department of Tourism; and to be connected to a proper sewage treatment system. |

|

Local population |

New regulations were issued to manage the behaviour of the local population, such as prohibiting the raising of chickens and pigs. Gambling is forbidden on the island. |

|

Infrastructure |

A road-widening project was launched to resolve congestion issues. Trash and unauthorised buildings were ordered removed from the wetlands, and buildings within 30 meters of the shoreline destroyed. |

Visitor management strategies for sustainable and green tourism

Sustainable and responsible tourism require innovative approaches to stimulate but manage demand. In addition to approaches like zoning, education of visitors, fines, and limits of acceptable change, more holistic strategies need to be developed.

Managing demand

Strategies for managing tourist demand include demarketing, ensuring that visits are spread over the seasons, and discouraging particular types of tourists identified as having significant impact on and low value to the destination area. Demarketing aims to decrease demand at a particular place and time. It adopts tactics from the classic marketing mix of the “four Ps” – Product, Place, Price and Promotion, as summarised by Hall and Wood (2021) (Table 4.3). Such tactics have been used to respond to issues of overtourism and could be used to relaunch tourism in a more controlled and sustainable way. For example, a product demarketing strategy was implemented that removed the Taj Mahal from the Uttar Pradesh tourism brochure, with the aim of redirecting tourists to other, less visited sites. In addition, ticket prices were increased to attract fewer but high-yield tourists (Kainthola, Tiwari and Chowdhary, 2021).

Table 4.3. Demarketing to manage visitor demand

|

Demarketing measures |

Marketing elements |

|---|---|

|

Using pricing as a tool, e.g. charging for access or time spent |

Price |

|

Using a time booking, queuing system to increase the time and opportunity costs of the experience |

Price |

|

Limiting promotion to selected and specialised media channels or ceasing promotion altogether |

Promotion, Place |

|

Promoting and communicating the need to conserve through minimal impact and sustainable development |

Promotion |

|

Communicating the environmental degradation and negative social effects on the host community that could occur if there are too many visitors |

Promotion, Place |

|

Communicating restrictions or difficulties associated with travel to the area |

Promotion, Place |

|

Providing alternative locations or experiences for visitors and communicating them |

Place, Product, Promotion |

|

Applying zoning policies to limit activities to some locations and not others, which may be undertaken seasonally |

Place, Product |

|

Limiting accommodation, parking, entrance or area access |

Place |

|

Permitting certain activities only for a set duration and/or with supervision, or ceasing particular activities |

Product |

|

Promoting and developing alternative site uses |

Promotion, Product |

|

Promoting virtual experiences as a substitute and/or complementary experience |

Promotion, Product |

|

Utilising interpretation as a management tool to reduce undesirable and inappropriate behaviours and developing new product relationships in order to reduce visitor pressures |

Promotion, Product |

Source: Authors’ compilation based on Hall and Wood (2021), “Demarketing tourism for sustainability: Degrowing tourism or moving the deckchairs on the Titanic?”, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/3/1585.

Another relevant concept is degrowth. Instead of focusing on the continuous growth and expansion of tourism, it emphasises the reduction of tourism size and impact as well as the rights of local communities and a rebuilding of the social capacities of tourism (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., 2019).

Managing effects of tourist presence

Strategies for reducing the negative effects of tourist presence involve modifying the way tourists use a site in order to reduce damaging practices. This can be done, for example, by dispersing or concentrating use through zoning and by developing clearly managed tourist trails to regulate tourists’ interaction with the environment and the local population. Regulations and education supporting sustainable tourism and behaviour need to be geared towards various stakeholders, including tourists, local residents and the tourism industry, and can be used in tourism planning and management in different ways.

The concept of persuasion is an indirect educational approach that can influence rather than police behaviour. For example, an exhibition on the impact of unsustainable tourist practices is a soft approach that can increase awareness and persuade visitors to adopt more responsible travel behaviour. Codes of conduct are often employed to educate tourists and are mostly used on a voluntary basis. Mandatory regulations are only effective if they are enforced. In many regions they are often poorly enforced or simply impossible to enforce due to financial or other constraints. However, when mandatory regulations are not followed, there can be enforceable consequences, usually a fine, which in itself can lead to increased compliance. Voluntary codes of conduct can contribute towards filling voids in mandatory regulations, especially while the mandatory rules are being developed and fine-tuned – a process that can take much longer than implementing voluntary codes of behaviour.

Managing resource capabilities

Strategies to ensure that a site has the resources to handle tourists sustainably include developing facilities and ensuring that the quality and provision of infrastructure is aligned to demand. As natural resources and social conditions are the key considerations for tourism to take place, one tool is carrying capacity, which aims to determine the number of visitors a destination can accommodate at a certain period of time without harming the ecological, economical or sociocultural environment. Indeed, quotas, i.e. the capping of tourist numbers, have been applied at a number of urban and coastal tourist destinations across Emerging Asia where overcrowding has become critical. Examples include the Forbidden City in Beijing, Maya Bay in Thailand, and Boracay in the Philippines. Another strategy is development-density controls, which are commonly based on the number of accommodation units per unit of land area. Height restrictions can be useful to prevent the built environment from becoming intrusive. Another indicator of density can be expressed by the floor area ratio (FAR), or floor space ratio (FSR), i.e. the area of all floors of all buildings on a site divided by the area of that site. Finally, minimum distances between landscape features (e.g. between the shore and the start of permitted built infrastructure), known as “setbacks”, play a central role in sustainable landscaping design.

Sustainable tourism in the blue economy

The blue economy is defined as “the sustainable use of ocean and coastal resources to drive economic growth and improve livelihoods while protecting and nurturing marine ecosystems, which involves coral reefs, mangroves and coastal settlements” (World Bank, 2017). All Emerging Asian countries except Lao PDR have access to the sea, and thus coastal areas. A significant percentage of the population in these countries lives within 60 kilometres of the coastline. For example, India’s coastline extends over 7 500 km and spreads over nine coastal states. Coastal and marine tourism have thus been an essential part of regional tourism development. The region’s extensive beaches, reefs, biodiversity, affordable prices, developed infrastructure and easy accessibility have attracted an ever-growing number of visitors and facilitated an abundance of economic opportunities.

The blue economy has diverse components, which usually include established traditional ocean industries such as fisheries, tourism and maritime transport, but also new and emerging activities, such as offshore renewable energy, aquaculture, seabed extractive activities, marine biotechnology and bioprospecting.

Coastal and ocean-related tourism range from mass forms of tourism, such as seaside and island resorts and cruise tourism, to alternative forms such as dive tourism, maritime archaeology, surfing, ecotourism and recreational fishing. In Emerging Asia, we can identify several forms of tourism that draw on the blue economy and ocean resources, including “Sun, Sand, Sea” tourism; snorkelling, diving and marine sports; cruise tourism; ecotourism including tours of local fishing villages; gastronomic tourism, involving the consumption of seafood; and research-related tourism including scientific tourism, academic tourism and volunteer tourism (Table 4.4). As an example, Box 4.3 demonstrates four major types of ocean tourism in the Philippines.

Table 4.4. Tourism products deriving from the blue economy in Emerging Asia

|

Type of tourism |

Benefits/potential |

Negative impacts |

Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Sun, Sand, Sea tourism |

Easy to develop across all market segments (budget to luxury) Generates the most local employment Many different mechanisms to integrate sustainability into tourism operations |

Mismanagement and overcrowding can lead to unsustainable tourism Solid waste and water pollution negatively affect the water quality and marine environments Increased bacteria in the water can lead to illnesses |

Preventing the overdevelopment of beaches and coastal ecosystems Presenting the business case for investing in natural assets to mobilise the private sector |

|

Snorkelling, diving and marine sports |

Can combine diving trips and marine sports with marine educational and clean-up activities Tourist interest and activities can lead to marine life protection, prohibiting commercial fishing |

Frequently dived sites may suffer damage or loss of coral cover due to close contact with divers stirring up sediment Snorkelers trample on corals Illegal removal of biodiversity or artefacts Damage resulting from boat anchors |

Making the economic benefits of diving more inclusive since it is a niche market |

|

Cruise tourism |

Highest growth rates prior to COVID-19 pandemic, with potential to recover Shore excursions can provide immediate economic benefit locally, stimulate infrastructure development, and recruit excursionists as future tourists if co-ordinated between cruise lines and local authorities |

Large negative environmental impacts while hoteling, cruising, mooring Congestion due to a large influx of simultaneous arrivals Can push out local tourists from top attractions in favour of higher-paying cruise passengers |

Addressing the environmental impacts Requires significant investments in port-of-call infrastructure Sustainable cruise tourism as an oxymoron |

|

Ecotourism |

Implementable as community-based ecotourism in smaller communities Linking ecosystems to tourism promotes the development of natural capital |

Potential damage to ecosystems and loss of biodiversity without good management of tourism |

Developing a tour that is enticing to paying customers Balancing nature conservation with economic activity |

|

Gastronomic tourism |

Tours to fishing communities and/or aquaculture Education and awareness about local food, resources and cuisine |

Overfishing Unsustainable seafood consumption |

Sustainable seafood production and consumption |

|

Research-related tourism (RrT) |

RrT travellers view tourism as a way to learn, explore, support communities and grow Research and volunteer programmes may include tracking animal behaviour, mapping coral reefs and mangroves, and conducting marine debris surveys |

Students and volunteers may lack the necessary professional experience and cause more harm than good |

Creating a win-win situation for local communities participating in or facilitating RrT and for researchers, students and volunteers who are keen to study and work in the area |

Source: Authors’ compilation based on APEC (2020), APEC Economic Study on the Impact of Cruise Tourism: Fostering MSMEs’ Growth and Creating Sustainable Communities, https://www.apec.org/docs/default-source/publications/2020/8/apec-economic-study-on-the-impact-of-cruise-tourism/220_twg_apec-study-on-the-economic-impact-of-cruise-tourism.pdf?sfvrsn=9ffd6385_1; Lamers, Eijgelaar and Amelung (2015); “The environmental challenges of cruise tourism: Impacts and governance”, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203072332-48/environmental-challenges-cruise-tourism-impacts-governance-machiel-lamers-eke-eijgelaar-bas-amelung; Pino and Peluso (2018), “The development of cruise tourism in emerging destinations: Evidence from Salento, Italy”, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26366552; Shah, Trupp, and Stephenson (2022), “Deciphering tourism and the acquisition of knowledge: Advancing a new typology of ‘Research-related Tourism (RrT)’”, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1447677021002084; and Zafra (2021), “Developing the Philippine blue economy: Opportunities and challenges in the ocean tourism sector”, https://www.adb.org/publications/developing-philippine-blue-economy-opportunities-and-challenges-ocean-tourism-sector.

Box 4.3. Profiling ocean tourism in the Philippines

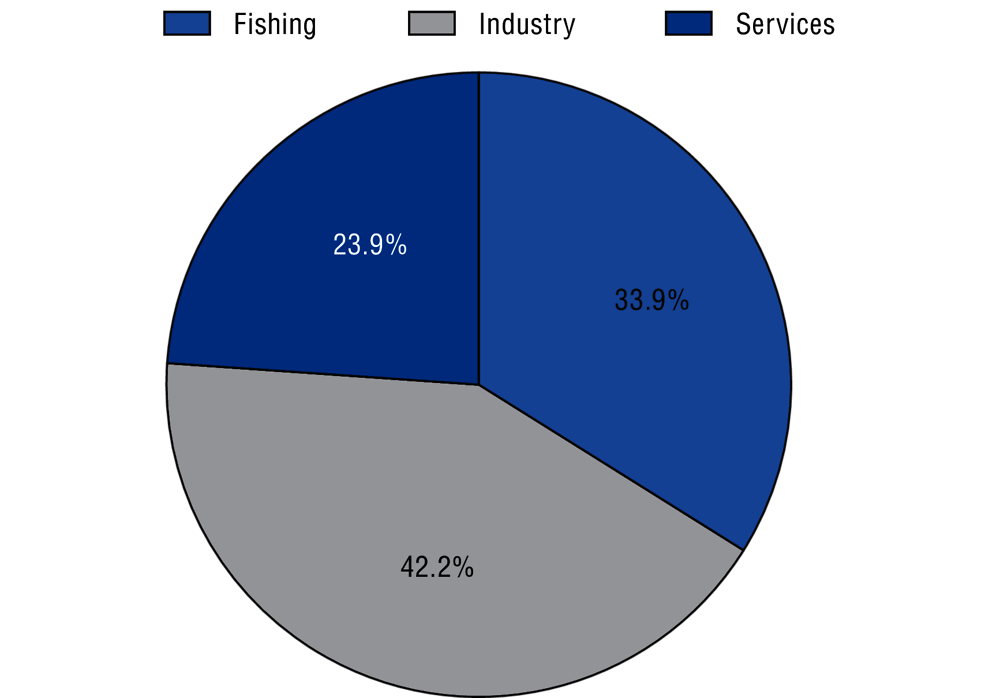

Services, which include tourism, contribute 23.9% to the Philippines’ blue economy, with ocean fishing and ocean industry accounting for the rest (Figure 4.1). The fishing sector includes fishing on open seas and sea-based aquaculture, while the industrial sector comprises the manufacture of ocean-based products, offshore and coastal mining, ocean-based power generation, transmission and distribution, and coastal construction. The services sector includes coastal accommodations, food and beverage activities and coastal recreation, together with other services activities. Opportunities and challenges are associated with certain types of ocean tourism, including sun and beach tourism, dive tourism, ecotourism and cruise tourism (Table 4.5).

Figure 4.1. Components of the ocean economy in the Philippines, 2021

Table 4.5. Blue economy tourism challenges in the Philippines

|

Activity |

Challenge |

|---|---|

|

Sun and beach tourism |

This is the major tourism product of the Philippines, as the country has more than 7 000 islands and a tropical climate. Many destinations are considered to be among the world’s best beaches or most beautiful islands, including Boracay, Palawan, Bohol and Cebu. Rapidly growing tourism on Boracay, the country’s top beach destination, generated more than USD 1 billion in 2017 from a record 2 million visitors. The island’s popularity resulted in cleanliness issues, environmental degradation and negative socio-cultural impacts, leading the government to order a 6-month closure for rehabilitation in 2018 (Box 4.2, above). |

|

Diving and marine sports |

Given the country’s location within the Coral Triangle, diving is a popular tourist activity in the Tubbataha Reefs National Marine Park in the Sulu Sea, the Apo Reef in Occidental Mindoro, Anilao in Batangas and Moalboal in Cebu. The Department of Tourism has hosted dive-centric events, trade shows, and expos to promote the country as a diving destination, while the Philippine Commission on Sports Scuba Diving regulates sports and technical diving, and the accreditation of diving establishments and individual divers. However, the lack of infrastructure, remoteness of the diving spots and seasonality can deter foreign divers from visiting, while scuba diving can be very expensive for locals. |

|

Cruise tourism |

Major cruise lines only began arriving in the Philippines in 2017. The five major ports of call (out of 140 ports) are at Manila, Boracay, Palawan, Ilocos Norte and Subic Bay. The growth rate of cruise tourism has been remarkable, from 446 international cruise passengers in January 2017 to 9 156 in January 2018. The Philippines is aiming to develop its cruise tourism product via a national cruise development strategy. |

|

Ecotourism |

Mangroves are an important part of the coastal ecosystem as a breeding ground for fish and aquatic species, a habitat for birds and a means of preventing soil erosion. Developing mangrove ecotourism is relatively low cost and easy to implement, and generates livelihoods and revenue for residents and coastal municipalities. Community-based ecotourism is thus well developed in mangrove areas. Communities put up boardwalks along the mangrove forest and offer guided educational tours, boating and kayaking trips, and bird-watching sessions. Benefits for the communities include increased mangrove cover and improvements in fishing. |

Source: Authors’ adaptation of Zafra (2021), “Developing the Philippine blue economy: Opportunities and challenges in the ocean tourism sector”, https://www.adb.org/publications/developing-philippine-blue-economy-opportunities-and-challenges-ocean-tourism-sector, and national sources.

Sustainable tourism can be part of the blue economy. It can help to promote conservation and sustainable use of marine environments and species, to generate income for local communities and to maintain and respect local cultures, traditions and heritage. Given the wealth and biodiversity of natural resources in Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Pacific Islands, the potential for a vibrant blue economy is especially high. In 2015, the share of ocean economy to gross domestic product (GDP) of countries in the region ranged from 30% (Thailand), 28% (Indonesia), 23% (Malaysia), 20.8% (Viet Nam) and 16% (Cambodia) to 9.4% (China) and 7% (Philippines and Singapore) (Global Environment Facility, United Nations Development Programme, and PEMSEA, 2018). It should be noted that the tourism sector is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and fluctuations in global economies (Connell, 2017).

The countries of Emerging Asia have expanded and improved infrastructure such as seaports and airports in the effort to expand the sectors of their blue economies. For instance, corresponding to the increase of international arrivals by water to Indonesia, the country has developed infrastructure for ground and port capacity, improving its ranking in the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitive Index by 43 points, to 34 in 2021 from 77 in 2015 (WEF, 2021). Indonesia has thus made a significant investment in resources for the blue economy. Viet Nam, China, Thailand, India and Cambodia have also improved their ground and port infrastructure. Singapore, one of the world’s most developed seaports, is ranked second in the WEF index, while Malaysia ranks just ahead of Indonesia in terms of ground and port infrastructure (Table 4.6). It should be noted that the expansion of ground and port facilities supports the development of cruise tourism as well as marine-related tourism activities.

Table 4.6. Ground and port infrastructure

|

Country |

2015 (score) |

2015 (rank) |

2021 (score) |

2021 (rank) |

Change in rank (2015- 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Indonesia |

3.27 |

77 |

4.1 |

34 |

43 |

|

Malaysia |

4.50 |

35 |

4.2 |

33 |

2 |

|

Philippines |

3.02 |

93 |

2.9 |

88 |

5 |

|

Thailand |

3.41 |

71 |

3.8 |

48 |

23 |

|

Viet Nam |

3.14 |

87 |

3.8 |

50 |

37 |

|

Singapore |

6.44 |

2 |

6.6 |

2 |

0 |

|

Cambodia |

2.61 |

116 |

2.6 |

99 |

17 |

|

Lao PDR |

3.01 |

96 |

2.5 |

105 |

-9 |

|

China |

3.91 |

53 |

4.7 |

22 |

31 |

|

India |

4.02 |

50 |

4.3 |

32 |

18 |

Source: Authors’ compilation from WEF (2021), Travel & Tourism Competitive Index, data from 2015 and 2021, https://www.weforum.org/reports/travel-and-tourism-development-index-2021/downloads-510eb47e12.

Cruise tourism

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, cruise tourism was among the fastest growing branches of the tourism industry. In Emerging Asia, the main ports for cruise tourism include Ho Chi Minh City (Viet Nam), Port Klang and Penang (Malaysia), Shanghai (China), Phuket (Thailand) and Singapore. However, cruise tourism has been highly criticised for its negative environmental and economic impacts. Cruise ships are practically floating hotels and produce a lot of waste. As documented by Lamers, Eijgelaar and Amelung (2015), on a seven-day cruise a medium-sized cruise ship with 2 000 passengers and 800 crew members aboard produces 750 000 litres of black water (water containing human waste), 3.75 million litres of grey water (from bathrooms, laundry and kitchen) and eight tonnes of solid waste. While cruising, these vessels also produce significant amounts of air and water pollutants, as well as greenhouse gases. Once they reach their destinations, cruise ships cause additional negative environmental impacts via mooring activities, including anchoring, embarking and disembarking at ports; loading supplies; and recreational activities onshore. The large influx of simultaneous arrivals often leads to overcrowding and congestion at the destination.

Nevertheless, cruise lines are increasingly aware of such negative impacts and are focusing on environmental protection. Furthermore, cruise tourism can generate positive economic spillovers for port cities. Liquid natural gas is replacing traditional fuels for cruise ships, leading to significant reduction in sulphur, particulate matter, and nitric oxide emissions and hybrid ships will soon follow, perhaps more than 15% of new ships in the next five years. Cruise lines are also supporting infrastructure development in ports to allow for connection to shoreside electricity, which is less polluting than running engines in ports (CLIA, 2023). Other benefits include infrastructure development to support excursionists, potential growth of port cities as tourist destinations, and economic opportunities for women and entrepreneurs.

The development of cruise tourism depends mainly on port facilities and access to water. Table 4.7 describes patterns of port calls in 2019 (CLIA, 2019). Singapore, China and India are generating regions for cruise passengers when the numbers of turnaround port calls are significant. The large volume of passengers from China and India contributes to the high volume of turnaround port calls in five major seaports of mainland China, Hong Kong (China) and Goa (India). Singapore, meanwhile, has become a boarding port for cruise passengers from nearby countries. Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia, which host more transit ships, are arrival destinations for cruise ships on the Asian loop. Transit calls also outnumber port calls in Viet Nam and the Philippines.

Table 4.7. Port calls, 2019

|

Country |

Port |

Transit |

Turnaround |

Overnight |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

China |

Baoshan/Shanghai |

22 |

221 |

33 |

276 |

|

Tianjin/Xinggang/Beijing |

15 |

129 |

17 |

161 |

|

|

Xiamen |

6 |

119 |

4 |

129 |

|

|

Guangzhou/Nansha |

0 |

98 |

0 |

98 |

|

|

Shenzhen/Shekou |

1 |

63 |

0 |

64 |

|

|

Hong Kong, China |

Hong Kong |

133 |

71 |

51 |

255 |

|

Philippines |

Manila |

41 |

2 |

6 |

49 |

|

Subic Bay |

21 |

0 |

1 |

22 |

|

|

Puerto Princesa |

13 |

0 |

1 |

14 |

|

|

Boracay |

12 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

|

|

Coron |

10 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

|

Thailand |

Paton Bay/Phuket |

151 |

22 |

15 |

189 |

|

Bangkok (Laem Chabang & Klong Toey) |

61 |

21 |

65 |

147 |

|

|

Koh Samui |

59 |

0 |

0 |

59 |

|

|

Phang Nga Bay |

9 |

0 |

0 |

29 |

|

|

Ko Hong |

28 |

0 |

0 |

28 |

|

|

Malaysia |

Port Klang |

126 |

43 |

7 |

176 |

|

Georgetown/Penang |

152 |

6 |

0 |

158 |

|

|

Langkawi |

95 |

0 |

8 |

103 |

|

|

Malacca |

62 |

0 |

0 |

62 |

|

|

Kota Kinabalu |

19 |

2 |

1 |

22 |

|

|

Singapore |

Singapore |

42 |

306 |

52 |

400 |

|

Indonesia |

Benoa/Bali |

28 |

26 |

16 |

70 |

|

Bintan |

51 |

0 |

0 |

51 |

|

|

Komodo/Slawi Bay |

40 |

0 |

4 |

44 |

|

|

Lembar/Lombok |

44 |

0 |

0 |

44 |

|

|

Semerang/Borobudor |

23 |

0 |

0 |

23 |

|

|

Viet Nam |

Ho Chi Minh City/Phu My |

100 |

1 |

43 |

144 |

|

Da Nang/Hue/Chan May |

106 |

0 |

10 |

116 |

|

|

Halong Bay/Hanoi |

50 |

0 |

13 |

63 |

|

|

Nha Trang |

40 |

0 |

0 |

40 |

|

|

India |

Mormugao/Goa |

66 |

61 |

19 |

146 |

|

Cochin |

35 |

2 |

10 |

47 |

|

|

Mumbai |

22 |

8 |

10 |

40 |

|

|

Mangalore |

24 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

|

|

Port Blair/Andaman Is |

7 |

0 |

1 |

8 |

|

|

Myanmar |

Yangon |

11 |

2 |

27 |

40 |

Note: Port calls are the number of planned deployments at the beginning of each year. A turnaround port call occurs when the vessel arrives under one cruise number and departs with a different cruise number. Transit port calls apply to all ships with arrival and departure scheduled on the same day. An overnight port call occurs when the vessel departs at least one day after arriving in port.

Source: Authors’ compilation from CLIA (2019), Asia Cruise Deployment and Capacity Report, Cruise Lines International Association, https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/2019-asia-deployment-and-capacity---cruise-industry-report.ashx.

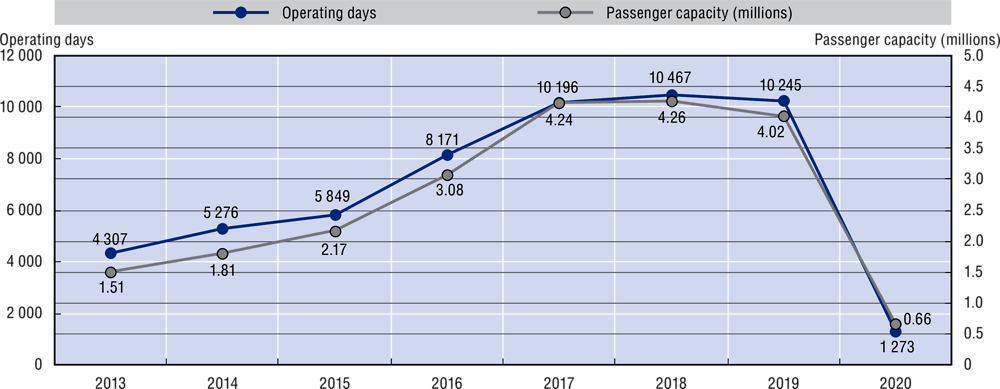

Figure 4.2 shows a sharp increase in the volume of cruise passengers in Asian waters between 2013 and 2020, demonstrating the rapid growth of the cruise tourism segment in Emerging Asia. However, cruise tourism was hit badly during the pandemic, and recovery has been slower than in other sectors.

Figure 4.2. Cruise ship capacity growth, 2013-20

Note: Operating days = days spent cruising in Asian waters. Passenger capacity = the number of lower berths multiplied by the number of cruises for each vessel.

Source: Authors’ calculations from CLIA (2020), Asia Cruise Deployment and Capacity Report, Cruise Lines International Association, https://cruising.org/-/media/clia-media/research/2021/oneresource/2020-asia-cruise-deployment-and-capacity-report.ashx.

Climate change and sustainable tourism

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China and India are home to 45% of the world’s population. Rapid modernisation and economic growth have made the region a significant contributor to climate change. Asia produces approximately half of global carbon emissions and will face rising temperatures, rising sea levels and a higher frequency of weather extremes. Climate change events include changes in precipitation, floods, storms, that endanger natural and built attractions, reduce the attractiveness of destinations and threaten livelihoods (Fang et al., 2022).

Tourism often develops in areas that are exposed to the effects of climate change, such as coastal areas, islands, low-lying urban areas and highland regions. At the same time, tourism activities contribute to carbon emissions both directly – for example, due to the combustion of petrol for transport or the use of energy for air conditioning in hotels – and indirectly, via carbon embodied in products bought or used by tourists, such as food, shopping and accommodation.

Carbon emissions

At the global level, tourism is responsible for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions (Lenzen et al., 2018). Carbon emissions in Southeast Asia have been rising at nearly 5% per year over the 1990-2010 period, mainly driven by deforestation and changes in land use and energy consumption concerning industry transport and coal and gas usage (ADB, 2015). The Asia-Pacific region produces at least 35% more greenhouse gases now than in the year 2000, and 80% of the region’s total greenhouse gas emissions were generated by just five countries – China, India, Japan, Korea and Russia (UNESCAP, 2022).

There are large regional differences in annual per capita emissions between the more economically advanced countries, such as Brunei Darussalam (16.6 metric tonnes), Singapore (8.8), China (7.4) and Malaysia (7.6), and the less developed countries such as Cambodia (0.7) and Myanmar (0.6) (World Bank, 2022). Based on absolute numbers, China is the world’s biggest carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter, followed by the United States and India. Odonkor (2020) notes that the region recorded “a total of 450 000 premature deaths as a result of energy-related air pollution” in 2018 and that this could reach at least 650 000 by 2040.

Effects of climate change

Temperature plays a significant role in tourism since it is closely correlated with climate comfort and the natural attractiveness of tourist destinations. Susanto et al. (2020) provide evidence from Indonesia, where every 1% increase in temperature is reflected in a 1.37% decrease in the number of international visitors. The region is expected to face higher economic costs from climate change than most other regions, especially in agriculture and tourism, where losses are expected to total 11% of GDP by 2100 (ADB, 2015).

Climate change has contributed to the closure or change of snorkelling and diving sites and the reduction of beach space. Evidence from Thailand’s Mu Ko Surin National Park shows how increasing sea temperatures at the destination led to mass coral bleaching, sea-level rise and increased wave height, resulting in a beach erosion rate of 0.38 metres per year and changes in precipitation (Cheablam and Shrestha, 2015). Similar developments have been observed in other coastal tourism destinations in Emerging Asia, prompting the dive tourism industry to enhance its adaptive capacity (Tapsuwan and Rongrongmuang, 2015). Suggestions include considering the effects of climate change on dive and snorkel operators’ business plans; diversification of products and services; and facilitating climate change discussions among operators within and across the region.

Poor and marginalised populations are greatly exposed to climate risks in Asia. Landlocked Lao PDR has a low adaptive capacity, making the country very vulnerable to climate change, especially floods and droughts. Since the 1990s, the heritage town of Luang Prabang, along the Mekong River, has become one of the country’s leading tourism destinations, and this has been accompanied by rapid construction, intensification of tourist businesses and displacement of the local population outside the heritage site. Climate change has exacerbated the destination’s rapid development. The combination of change in land cover and climate change increases flood risks. In Lao PDR, low capacity and limited staff and resources have played a role in hindering the country’s aim to make cities greener and more resilient (Fumagalli, 2020).

In an assessment of the optimal use of natural resources, the tourism industry faces a multitude of significant sustainability-related challenges. The importance of sustainability is included in the ASEAN Tourism Strategic Plan 2016-2025. Its core challenges include implementing Strategic Direction 2, “to ensure that ASEAN tourism is sustainable and inclusive”, and Strategic Action 2.3, to “increase the responsiveness to environmental protection and climate change” (ASEAN, 2015).

Specific challenges that need to be resolved through the greening of the industry include: i) energy and greenhouse gas emissions; ii) water consumption; iii) waste management; iv) loss of biological diversity; v) effective management of built and cultural heritage; and vi) planning and governance (UNEP and UNWTO, 2012).

Table 4.8 presents “Pillar 15: Environmental Sustainability” from the dataset of World Economic Forum’s latest Travel & Tourism Development Index (WEF, 2021). The measurement of environmental sustainability is based on three main indicators, all of which impact travel and tourism: climate change exposure and management; pollution and environmental conditions; and preservation of nature. Results are on a scale of 1-7. In Emerging Asia, the Philippines (3.11) and Thailand (3.13) score lowest on climate change. For the second indicator, which includes water stress, marine and air pollution, loss of forest cover and risk of species extinction, India scores lowest (2.64), while China (3.32) and Viet Nam (3.41) are on the critical threshold. India again scores lowest on preservation of nature (3.71). Overall, Singapore obtains the region’s best score for environmental sustainability (4.04), followed by Indonesia and Cambodia (3.90).

Countries in the region, however, have taken various initiatives to address environmental challenges in the tourism sector and shift towards sustainable practices. In Thailand, for instance, low-carbon, organic and sustainable approaches are implemented in several areas including Phuket-Phang Nga, and Pathom Organic Village in Suan Sampran that use sustainable food system and organic farming.

Table 4.8. Environmental sustainability in countries of Emerging Asia (WEF Pillar 15)

|

Indicator |

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

Philippines |

Thailand |

Viet Nam |

Singapore |

Cambodia |

Lao PDR |

China |

India |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Climate change exposure and management, 1-7 (best) |

3.63 |

3.21 |

3.11 |

3.13 |

3.58 |

3.97 |

3.92 |

3.65 |

3.44 |

3.56 |

|

Greenhouse gas emissions, tCO2e/pop |

6.37 |

12.31 |

2.2 |

6.21 |

3.81 |

11.82 |

4.26 |

5.47 |

8.4 |

2.47 |

|

Renewable energy, % of total energy consumption |

20.86 |

5.31 |

23.22 |

23.72 |

23.49 |

0.73 |

61.84 |

41.88 |

13.12 |

31.69 |

|

Global Climate Risk Index |

49.42 |

96.50 |

22.42 |

36.50 |

42.92 |

145.00 |

56.00 |

57.84 |

49.58 |

27.59 |

|

Investment in green energy and infrastructure, 1-7 (best) |

5.19 |

4.27 |

2.81 |

3.62 |

4.27 |

5.05 |

2.86 |

3.32 |

5.61 |

3.95 |

|

Pollution and environmental conditions, 1-7 (best) |

3.76 |

4.01 |

3.90 |

3.55 |

3.41 |

4.00 |

3.65 |

3.63 |

3.32 |

2.64 |

|

Particulate matter (2.5) concentration (µg/m^3) |

19.4 |

16.6 |

18.8 |

27.4 |

20.4 |

18.8 |

22.1 |

20.5 |

47.7 |

83.2 |

|

Baseline water stress, 0-5 (worst) |

2.07 |

0.28 |

1.55 |

2.98 |

0.94 |

5.00 |

0.42 |

0.03 |

2.40 |

4.12 |

|

Red List Index, 0-1 (best) |

0.76 |

0.70 |

0.67 |

0.77 |

0.72 |

0.85 |

0.78 |

0.81 |

0.73 |

0.67 |

|

Forest cover loss, average % of baseline |

0.88 |

1.46 |

0.47 |

0.75 |

1.56 |

1.23 |

1.59 |

1.83 |

0.35 |

0.39 |

|

Wastewater treatment, % |

0.03 |

19.59 |

2.58 |

12.07 |

0.20 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

16.13 |

2.25 |

|

Clean ocean water, 0-100 (best) |

58.24 |

57.68 |

54.15 |

60.33 |

45.42 |

38.77 |

53.36 |

n/a |

35.10 |

29.48 |

|

Preservation of nature, 1-7 (best) |

4.32 |

3.91 |

3.97 |

4.22 |

4.04 |

4.14 |

4.13 |

4.12 |

4.51 |

3.71 |

|

Environmental treaty ratification, 0-29 (best) |

22 |

21 |

25 |

21 |

23 |

18 |

21 |

20 |

24 |

26 |

|

Adequate protection for nature, 1-7 (best) |

4.93 |

4.11 |

3.17 |

3.95 |

4.39 |

5.50 |

3.47 |

3.87 |

5.02 |

2.84 |

|

Oversight of production impact on the environment and nature, 1-7 (best) |

4.83 |

4.33 |

4.31 |

4.43 |

4.19 |

5.02 |

3.45 |

4.05 |

4.89 |

3.91 |

|

Total protected areas, % total area |

5.27 |

7.55 |

3.72 |

13.27 |

2.93 |

2.46 |

31.77 |

18.69 |

14.75 |

4.40 |

|

Average proportion of key biodiversity areas covered by protected areas, % |

21.67 |

13.33 |

33.71 |

45.58 |

21.43 |

5.86 |

45.06 |

43.96 |

9.02 |

15.09 |

|

Pillar 15: Environmental sustainability, 1-7 (best) |

3.90 |

3.71 |

3.66 |

3.64 |

3.68 |

4.04 |

3.90 |

3.80 |

3.75 |

3.30 |

Source: WEF (2021), Travel & Tourism Competitive Index, data from 2015-21, https://www.weforum.org/reports/travel-and-tourism-development-index-2021/downloads-510eb47e12.

Depletion of forest resources in Southeast Asia is another critical issue. Statistics of forest coverage area from 1990 to 2020 from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database (World Bank, 2022) in Table 4.9 show that the highest level of accumulative forest loss has been in Cambodia, Indonesia, and Myanmar. However, forest cover expanded in China, India, and Thailand, and increased dramatically in Viet Nam.

Tourism in developing Asia is highly concentrated in certain areas (Dolezal, Trupp and Bui, 2020). This can adversely affect fragile environments such as mountains or oceans. Box 4.4 shows the negative impact of increasing numbers of tourists in India’s Himalayas.

Table 4.9. Forest area in Emerging Asia, 1990-2020

Percentage of total land area

|

Country |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brunei Darussalam |

78.4 |

75.3 |

72.1 |

72.1 |

|

Cambodia |

62.3 |

61.1 |

60.0 |

45.7 |

|

China |

16.7 |

18.8 |

21.3 |

23.3 |

|

India |

21.5 |

22.7 |

23.4 |

24.3 |

|

Indonesia |

65.4 |

53.9 |

53.1 |

49.1 |

|

Lao PDR |

77.3 |

75.5 |

73.4 |

71.9 |

|

Malaysia |

62.8 |

59.9 |

57.7 |

58.2 |

|

Myanmar |

60.0 |

53.4 |

48.1 |

43.7 |

|

Philippines |

26.1 |

24.5 |

22.9 |

24.1 |

|

Singapore |

22.1 |

25.4 |

25.3 |

21.7 |

|

Thailand |

37.9 |

37.2 |

39.3 |

38.9 |

|

Viet Nam |

28.8 |

37.9 |

42.7 |

46.7 |

Note: Forest area (% of total land area) = Land under natural or planted stands of trees of at least 5 metres in situ, whether productive or not, and excludes tree stands in agricultural production systems (for example, in fruit plantations and agroforestry systems) and trees in urban parks and gardens. Areas under reforestation that have not yet reached but are expected to reach a canopy cover of 10% and a tree height of 5 metres are included, as are temporarily unstocked areas, resulting from human intervention or natural causes, which are expected to regenerate.

Source: World Bank (2022), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Box 4.4. Mountain tourism in the Indian Himalayas

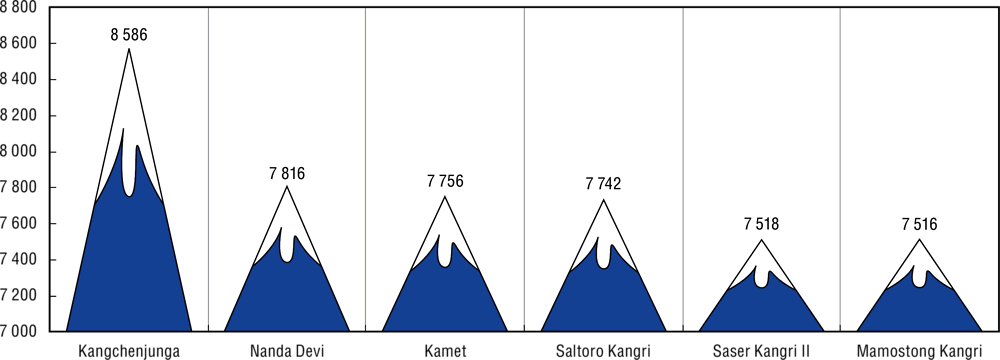

India’s Himalayan Region is well known not only for its scenic beauty, subalpine and alpine pastures, and rich biodiversity, but also for its cultural diversity. The region offers two types of tourism to domestic and international visitors. Trekkers and mountaineers come for adventure tourism, while the region draws Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims worldwide. India is home to Kangchenjunga, the third tallest mountain in the world and a particularly sacred mountain for the Lepcha and Bhutia peoples of Sikkim.

Figure 4.3. Tallest peaks in the Indian Himalayan range, metres

Source: Authors’ compilation based on data from Alpine Club (n.d.), Himalayan Index database, http://www.alpine-club.org.uk/hi/screen1.php.

Under India’s Swadesh Darshan programme, theme-based tourist circuits have been developed in the region, such as the Northeast Circuit, Eco-circuit, Himalayan Circuit and Spiritual Circuit. Tourism has been rising for decades in the region, interrupted only during the pandemic in 2020-21. However, increasing tourist flows have increased waste disposal alongside valleys and rivers in the mountains, and waste management has been a big challenge. Other issues include deforestation in Sikkim and water shortages. While local residents consume an average of 75 litres of water a day, a tourist consumes about 100 litres a day. The Ladakh region suffers from water shortages as the state is mostly dependent on snow/glacial melt and the flow of the River Indus.

Recommendations have been issued to the respective states for better tourism management. The first is an assessment of carrying capacity at tourist destinations and eco-sensitive zones prior to online registration of visitors. The second calls for the quantification and segregation of waste; development of biocomposting units; and community-based recycling of non-biodegradable waste. Third, regular monitoring of air and water quality is to be practiced in urban and rural areas to assess tourism’s impact, along with an inventory of water resources, including seasonal discharge rates. Fourth, the positive and negative aspects of tourism are to be assessed in a study on tourism activities, biodiversity and the socio-cultural system. Strengthening of community-based tourism needs to be encouraged to reinforce sustainable tourism in the Indian Himalayan Region.

Source: Government of India (2022), Environmental Assessment of Tourism in the Indian Himalayan Region, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/tourism-environmental-assessment-Himalayan-region-report-NGT-June2022.pdf.

The way forward

Studies highlight that tourism stakeholders often lack understanding of the actual causes of climate change or that they view climate change as irrelevant to their business (Mat et al., 2020). Such misconceptions can lead to wrong action or inaction regarding business or destination management. Knowledge-transfer programmes and broader public and community participation have been suggested to complement climate-change policies (Tapsuwan and Rongrongmuang, 2015).

There is also the need for a more systematic measuring of climate impacts on tourism for public and private-sector organisations alike. While governments can record climate data aligned with their climate commitments, businesses and industry stakeholders also need to be well informed about carbon and climate risks and engage in environmental commitments. Tourism and hospitality companies can collect data on energy consumption, sources and volume of carbon emissions, and usage of other resources, as suggested in a recent report (ADB and UNWTO, 2022).

Studies recommend a shift to cleaner technology and non-fossil-fuel energy, as well as more resource-saving consumer behaviour (Zhang and Liu, 2019). Governments should create additional mechanisms to encourage environmentally sustainable behaviour and to ensure that tourism stakeholders, including tourists, local communities and industries, are held accountable for their effect on the environment. Sun, Lin and Higham (2020) propose reconfiguring the tourism demand mix to promote low-carbon regional travel. Specific scenarios for achieving the reduction of tourism-based emissions include degrowth (reducing tourist numbers), low-carbon-intensity trips (longer stays and even distribution in monthly arrivals), carbon reduction (via eco-efficiency of tourist infrastructure) and carbon-offset initiatives (e.g. for inevitable air travel). Green tourism initiatives in Southeast Asia should also further encourage domestic and regional travel, which depend less on travel by air.

Community-based approaches in ethnic and indigenous tourism

Tourism not only has environmental impacts that compromise sustainability but also leads to changing sociocultural dynamics, including in gender relations (Trupp and Sunanta, 2017), cultural commodification (Cole, 2007), inequalities within the resident population (Dolezal and Novelli, 2020) and economic leakages (Geoffrey Lacher and Nepal, 2010). Such sociocultural impacts play a particularly important role in destinations where local people themselves represent part of the tourist attraction, such as in ethnic and indigenous tourism.

Ethnic tourism is when travellers choose to experience the practices of another culture first-hand. In Emerging Asia, such tourism takes place in the highlands of Southeast Asia (Thailand, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Viet Nam) and in south-western China (Yunnan). It takes the form of trekking tours; one-day excursions to easily reachable minority or indigenous villages; and ethnic-minority souvenir selling at urban markets or beachside tourist destinations (Trupp, 2017).

In Thailand, much ethnic tourism to highland villages (“hilltribe tourism”) evolved in an uncontrolled and unplanned manner. Many of these villages receive a high number of tourists (sometimes more than 100 per day), yet their participation in the planning and management of tourism and their actual benefit from it is very low. Tourist numbers often fluctuate, and there is no secured income from tourism as villagers largely depend on tourist-generated income from souvenir selling, posing for cameras and taking part in local homestays. Another common problem is that tourism-generated income often benefits a local elite, who run the accommodation or the most prominent souvenir stalls in the village. Such tourism does not necessarily support local development and can lead to further local and regional disparities.

To counter such developments, one strategy is community-based tourism (CBT), which seeks to engage the host community in tourism planning, development and management. CBT has emerged as an alternative to mass tourism and its negative impacts. It can be a catalyst for reviving local cultures, including the languages, customs and traditions of indigenous groups, thus helping to achieve sustainable development goals (Scheyvens et al., 2021). For example, in Lai Chau (Viet Nam), Sìn Suối Hồ CBT successfully promotes indigenous leadership. Villagers know that their H’Mông traditional identity attracts tourists and have integrated traditional livelihoods, such as horticulture and agriculture, into the tourism value chain (Phi and Pham, 2022).

“Pro-poor tourism”, which integrates the tourism development agenda with poverty alleviation, can be of use in the region, where a substantial proportion of the population lives below the poverty line. Pro-poor tourism is an impetus for local development in less developed countries such as Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar, and for ethnic groups communities in Thailand (Trupp and Sunanta, 2017), China (Wen, Cai and Li, 2021) and Viet Nam (Truong, Hall and Garry, 2014). A case study in Lao PDR highlights the potential that tourism offers to some communities, but also identifies challenges and consequences that can undermine the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Pasanchay and Schott, 2021). In remote mountainous areas of Viet Nam, for example, there has been unequal distribution of profit from tourism, with a large proportion of income going to the tour operators, leaving a tiny balance for poor local street vendors (Truong, Hall and Garry, 2014).

Box 4.5. Risks faced by local communities that become dependent on tourism

Tourism development is widely promoted as providing livelihoods for local communities, including those whose resources depend on the ocean, such as fishing villages. A case study on Indonesia’s Komodo island of a fishing village that became dependent on tourism shows both the opportunities and challenges of this sort of livelihood transition (Lasso and Dahles, 2018). Tourism on Komodo has been rising since the 1980s, mainly been driven by Komodo National Park, home of the famous Komodo dragon, as well as improved accessibility and increasing numbers of cruise-ship tourists.

Table 4.10. Komodo dragon facts

|

Type |

Reptile |

|

Diet |

Carnivore |

|

Average life span in the wild |

30 years |

|

IUCN Red List status* |

Endangered |

|

Size and weight |

10 feet (3 metres), 330 pounds (150 kilogrammes) |

|

Size relative to a 6-foot (1.8-metre) man |

|

Note: * International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species.

Source: Authors’ adaptation from National Geographic (n.d.), “Komodo dragon”, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/reptiles/facts/komodo-dragon.

Tourism in the coastal areas of Komodo brought in additional income and also contributed to local livelihoods by reducing pressure on natural resources. Fishermen on the island increasingly moved away from fishing and involved themselves in tourism-related entrepreneurial activities, mainly souvenir businesses, and in smaller numbers in homestays and local tour guiding. Although the transformation from a fishing-based to a tourism-based livelihood brought about relatively good income for local community members, this shift significantly increased their vulnerability. A return to the fishing economy has become very difficult as many local people have given up their boats and surrendered their fishing skills.

Dependency on tourism as a single source of income becomes highly challenging in times of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stakeholders in local coastal and island tourism contexts need to support livelihood diversification involving both tourism- and non-tourism-based businesses. Education and training for local community members are needed to expand their skills beyond souvenir production and sales.

Another issue spawned by increased tourism is the displacement of local communities, abandonment of traditional practices and increased reliance on tourism as a livelihood activity (Movono, Scheyvens and Auckram, 2022). A study of Komodo Village on Indonesia’s Komodo Island revealed that increased tourism resulted in the local community giving up fishing to focus on selling souvenirs. While this may deliver short-term gains, dependence on this new livelihood brings considerable risks given that the market is limited, competitive and seasonal (Lasso and Dahles, 2018) (Box 4.5). In search of a better model of local community participation in tourism, a partnership between the private sector and the community at the Misool Marine Reserve, also in Indonesia, sets an excellent example of linking tourism with conserving the marine environment (Box 4.6).

Box 4.6. Linking ecotourism with conservation: Misool Marine Reserve

The Misool Marine Reserve protects a complex and biodiverse coral-reef system in South Raja Ampat, Indonesia. The reserve is jointly managed by the Misool Foundation and Misool Resort, a private island resort that uses ecotourism revenue to fund the reserve. The Misool Marine Reserve was established in 2005. A unique lease agreement forged with the local community enabled the creation of a 425 km2 no-fishing zone, known as a No-Take Zone (NTZ), expanded in 2010 to cover 1 220 km2 across two connected zones. All marine extraction is prohibited within the NTZs, including small-scale artisanal fishing and the collection of turtle eggs. The initiative not only prevents overfishing and marine plastic pollution associated with the fishing industry, but also prevents destructive illegal fishing practices and protects marine species, such as sharks, from exploitation by illegal wildlife traders. By successfully expanding their outreach and engaging in multistakeholder partnerships, including with international NGOs involved in conservation, Misool Resort served as a catalyst for the declaration of a Shark and Manta Sanctuary across the entire marine area of Raja Ampat (46 000 km2), aimed at re-establishing healthy stocks of these species, and the development of a network of six marine protected areas across Raja Ampat that together protect nearly 45% of the area’s reefs and mangrove systems.

The Misool Ranger Patrol enforces the NTZs with patrols from their basecamp at the resort and three satellite ranger stations. Some rangers are former fishermen who now earn more by protecting the reserve and educating their communities on marine conservation. The ranger patrol is funded by Misool Resort as well as grants from international foundations and private donors. In 2019, the rangers conducted 383 patrols, with an average of 3.05 hours of patrol time per person per day.

Together, Misool Resort and the Misool Foundation employ about 250 people, 96% of whom are Indonesian. These salaries support an estimated 1 000 people from the local communities. In addition, Misool Foundation established two sustainable livelihood co-operatives in the Misool area and on Solor Island in East Indonesia. These co-operatives provide training in sustainable fishing techniques and assist with developing skills in business and financial management. The reserve’s management plan is periodically reviewed and updated to ensure optimum performance.

Figure 4.4. Marine Protected Area as a percentage of exclusive economic zone

Through this approach, the Misool team has demonstrated a number of best practices in conservation, including establishing a marine protected area, expanding protection outside the boundaries of the protected area, involving the local community, positively impacting the local economy, working with the government, collaborating with other conservation groups, adapting to change, mitigating the potential negative consequences of ecotourism, implementing innovative waste management solutions, conducting research and monitoring, and educating others.

Source: Authors’ adaptation from UNESCAP and Misool Foundation (n.d.), Misool Marine Reserve: Successfully Linking Ecotourism with Conservation, https://sdghelpdesk.unescap.org/technical-assistance/best-practices/misool-marine-reserve-successfully-linking-ecotourism.

Local communities in remote mountainous areas play an important role in promoting small-scale sustainable tourism. Owing to the cultural and religious symbolic meaning of the mountain, in addition to surrounding forests and landscapes, innovative tourism products with links to the local community are options for development (Jones, Bui and Apollo, 2021). Mountains are not only distinctive for biological characteristics and landscape values, but numerous Himalayan peaks are sacred in indigenous beliefs. Mountainous areas also provide excellent environments for stargazing and viewing astronomical phenomena, which can be sold as “astrotourism” experiences with facilities, lodging and guides (Table 4.11). Participants on these tours also have opportunities to interact with the local villages and appreciate their arts and crafts. A series of experiences known as Astrostays established in the Ladakh region of India demonstrate the fullest potential of this tourism model. The experiences provide jobs, especially for women, and the revenues generated are reinvested into community improvements such as greenhouses and solar water heaters (UNWTO and FAO, 2021).

Table 4.11. Examples of astrotourism locations in low- and lower-middle-income countries*

|

Location |

Country |

Attraction |

|---|---|---|

|

Siloli Desert |

Bolivia |

Nature |

|

Arsanjan |

Iran |

Nature |

|

Masai Mara National Park |

Kenya |

Stargazing |

|

Playa Maderas |

Nicaragua |

Nature |

|

Kirindy Mitea National Park |

Madagascar |

Stargazing |

|

Chenini Village |

Tunisia |

Stargazing |

Note: “Attraction” refers to the principal attraction for the location. Astrotourism can take place at all sites. *Country income classification is based on World Bank Country and Lending Groups for fiscal year 2023.

Source: Astrotourism (n.d.), “Places”, https://www.astrotourism.com/world-best-stargazing-places-top-astrotourism-destinations/.

Another such successful mountain tourism example is “The Akha Experience” in northern Lao PDR, a community-based ecotourism programme. During a three-day trek to eight Akha villages, participants meet the villagers, get acquainted with their tangible heritage (traditional dress, local food, cultural artefacts, village structure and local houses) and learn about their oral traditions, local knowledge and rituals as well as the local livelihood and environment (rice cultivation, forest products, livestock).

The Akha Experience grew out of a public-private partnership (PPP) between eight local village communities, an international development agency and a private tour operator. While the local villagers are rich in cultural knowledge and resources, many lack the experience and training to operate a tourism business. Therefore, the development agency, in co-operation with the local government, facilitated training and workshops, such as a tourism-awareness workshop; technical training in hospitality, cooking, hygiene, housekeeping and management; and education in English and tour guiding. The private-sector tour operator played an important role by facilitating access to the international tourism market. The package for tourists includes items and activities that directly benefit the community, such as a village development fund to which every visitor contributes; locally prepared food making use of local ingredients; a locally crafted souvenir that every visitor receives as a gift; a local forest preservation and trail maintenance fee; and various local entertainment and performance activities. A rotational system was put in place for hosting tourists in local homestays so that different villages and communities could share the work and the benefits. Yet there were challenges. While this approach achieved higher economic benefits for local community members and stronger participation in various activities, the transition from external to local control did not take place.

Enhancing linkages

Linkages and leakages are opposites in the local development of tourism. Leakages, or the amount of revenue that leaves the local economy (especially through payments for imported goods), represent a challenge. In contrast, linkages strengthen the relationship between the tourism sector at a particular place and local non-tourism industries such as agriculture, fisheries or crafts. There are prospects for linkages between food producers and the hospitality industry, based on the notion that it should be possible to enhance local food systems that supply tourist hotels and resorts in the region.

For example, Club Med resorts in Indonesia (and other emerging economies) collaborate with Agrisud, a non-governmental organisation (NGO), towards a lasting match between local supply of food products and the demand of Club Med resorts (UNWTO, 2018). The aim is to meet criteria for quality, quantity, diversity, regularity and prices, and to ensure fair remuneration for producers and a strong distribution of added value, giving the poorest groups access to these markets. The project works with very small enterprises and supports local farmers by: i) strengthening producers’ capacities in technical matters, management and organisation; and ii) establishing a sustainable local procurement system via participatory development of the procurement protocol and by grouping producers into commercial co-operatives. The role of Club Med is to support the NGO’s work financially and to buy the produce directly from the small farming enterprises. At the resorts, the source of the food on offer is highlighted to customers and excursions can be booked to the nearby farms. Such projects often raise concerns over costs of local production, irregularities in volume and quality of products, and interruptions of demand due to seasonality and unforeseeable events and crises.

Partnerships between NGOs and private tourism businesses can be highly effective to support local development and small businesses while simultaneously benefiting a large enterprise. At the same time, a strong and respectful relationship between a resort and farming groups needs to be established and developed. This includes agreement on production schedules, purchase commitments and pricing. Finally, such partnerships are also an opportunity to educate guests about eating locally and seasonally, thereby creating more awareness on sustainable production and consumption.

Moving towards higher quality is essential for increasing the value derived from tourism in the green economy (Box 4.7).

Box 4.7. Digital nomads: Shift of focus from mass tourism to sustainability

Indonesia is moving away from mass tourism in favour of ecotourism and sports tourism, as well as promoting nature and culture to tourists. Focusing on quality and sustainability marks a major shift of tourism and travel operations towards a green economy. Quality tourism with positive impacts on local communities is promoted by offering tourists products such as local food and traditional headgear in community-based tourism in 3 000 villages across the country. Moreover, travellers spending their holiday in Indonesia can offset the carbon footprint of their flights through activities like mangrove planting or waste management and by empowering local people, who benefit from tourist dollars.

Indonesia is also targeting longer-staying tourists, or “digital nomads” – people working remotely who stay a month or longer in destinations to combine work with leisure. Longer-stay tourists are better for the local economy because they tend to spend more on locally produced goods and services, which has economic multiplier effects. It also helps the environment, as increasing the availability and consumption of local products by fewer but longer-staying visitors can shorten supply chains and reduce negative environmental impacts – two critical factors for building destination resilience and sustainability.

Malaysia and Thailand are also seeking to attract longer-term tourists focused on sustainability. However, the intentions of each offer may vary (Table 4.12). For instance, the “digital nomad” visas offered by Indonesia and Thailand are targeted to medium-term investors, while the Malaysian visa offers more relaxed conditions. Visas may also vary by the length of eligibility, and the eligibility of family members to join the initial applicant in the destination country.

Table 4.12. “Digital nomad” visas in Asia

|

Country |

Visa name |

Terms |

Eligibility criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Indonesia |

Second-Home Visa and Temporary Stay Permit |

5 or 10 years Fees: IDR 3 million (Indonesian rupiah) |

Passport: valid for 36 months minimum Funds: IDR 2 billion minimum, must be placed in Indonesian state-owned banks |

|

Malaysia |

DE Rantau Nomad Pass |

3-12 months and renewable for up to 12 months Spouse and children eligible Fees: MYR 1 000 (Malaysian ringgit) each for applicant and spouse, MYR 500 for dependents |

IT job Employment contract >3 months Annual income > USD 24 000 |

|

Thailand |

Long-Term Residency Visa |

5 years, renewable for another 5 years with conditions Spouse and children eligible |

Minimum income, assets and investments in Thai government bonds, FDI or Thai property Possible minimum education and field requirements Conditions depend on class of visa |

Source: Authors’ compilation from Direktorat Jenderal Imigrasi (2022), “Press release: Directorate General of Immigration officially launches second-home visa”, https://www.imigrasi.go.id/en/2022/10/25/siaran-pers-ditjen-imigrasi-resmi-luncurkan-aturan-second-home-visa/; Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (n.d), “For foreign digital nomad”, https://mdec.my/derantau/foreign/; Thailand Board of Investment (2022), “Long-term residents visa Thailand”, https://ltr.boi.go.th/.

ICT infrastructure is the most important concern for attracting digital nomads. The digital nomad lifestyle is built upon not being bound to a particular physical location for work. Digital nomads are often self-employed or are otherwise in agreement with their employers to work on a fully remote basis. This means that if wireless ICT infrastructure performs poorly or fails outright (as in the case of a disaster), digital nomads risk losing their ability to produce output and earn a living as they do not have employer offices as a last resort. Improving digitalisation within countries (which should be a top priority, as discussed in previous editions of the Outlook) will expand the geographic range where the digital nomad life is feasible.

Source: Authors’ adaptation from ADB (2021a), Sustainable Tourism after COVID-19: Insights and Recommendations for Asia and the Pacific, https://www.adb.org/publications/sustainable-tourism-after-covid-19-insights-recommendations, and Teresia (2022), “Indonesia aims to lure more digital nomads to its shores”, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesia-aims-lure-more-digital-nomads-its-shores-2022-09-15/.

Rethinking tourism products in the green and blue economies

This section considers options for diversifying tourism by rethinking the development of beach and island tourist destinations, where mass tourism has caused damage, and analyses the advantages and challenges presented by alternative “niche” forms such as ecotourism.

Beach and island tourism

Tropical beaches and islands have long been part of Southeast Asia’s tourism identity and are still dominant in tourism development planning (Dolezal, Trupp and Bui, 2020). Alongside the perennial popularity of seaside resorts, the remoteness of island destinations has gradually been overcome. With cheaper airlines, higher incomes and longer vacations, tourism has brought new development to isolated islands. Those with advantages in terms of clean beaches, unpolluted seas, warm weather and the vestiges of distinct cultures have the potential to be turned into luxury hideaways. However, while some Asian islands have received overwhelming numbers of tourists owing to distinctive resources, most islands without unique cultural or natural attractions remain far from conventional tourist circuits.

Sustainable development of beaches and islands through tourism has proved difficult (Connell, 2020). Major challenges faced by seaside resorts and islands are outlined below.

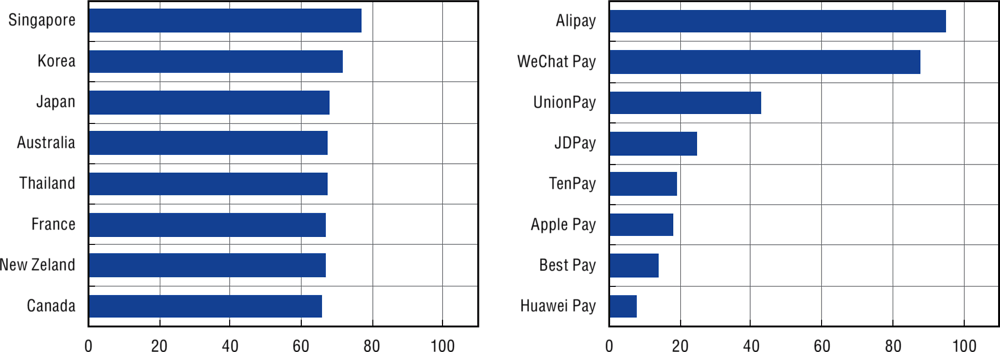

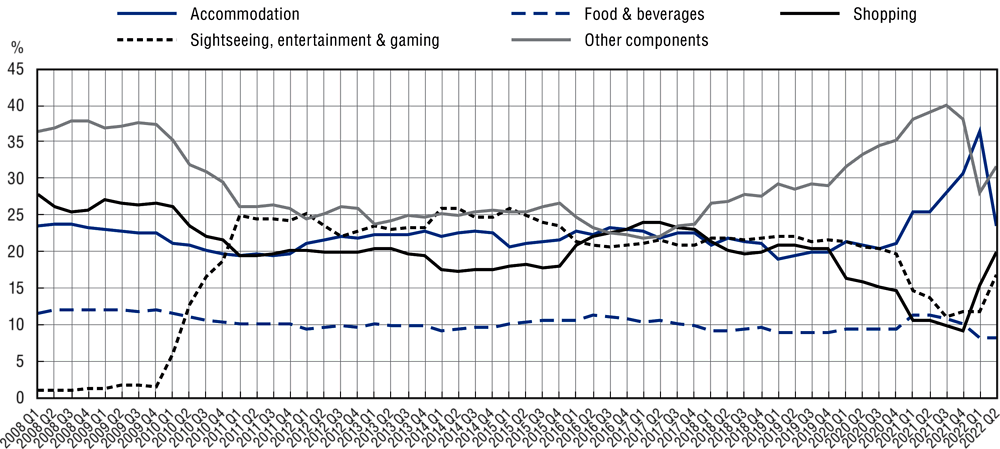

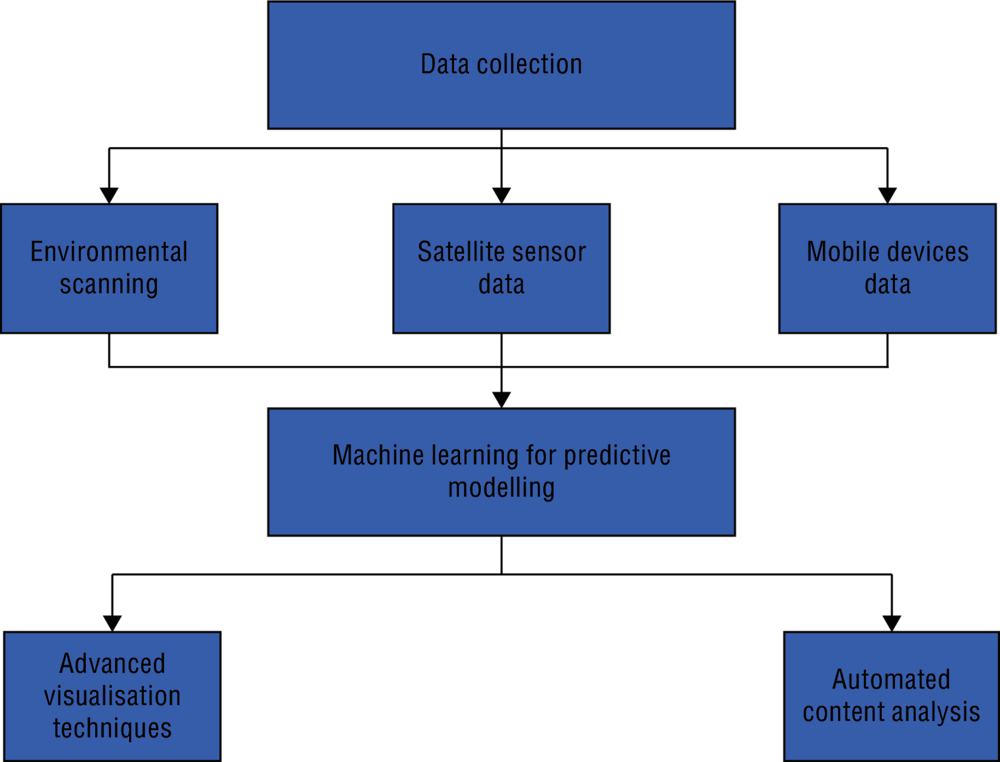

Marginalisation of locals. Promoting tourism and finding markets has usually been the province of hotels, travel agents and national and regional tourism bodies, all of which can be remote from local people. When Kuta (Bali, Indonesia) evolved from a small village to a popular tourist destination, local people played a declining economic role as people from other provinces and international interests constructed hotels and other facilities and secured employment. But sometimes locals benefit from tourism. For instance, a recent boom has brought large numbers of weekend visitors to Tap Mun Island (Hong Kong, China), which had seen a decline of agriculture, fishing and population but is now welcoming tourists who spend money on food, souvenirs of dried fish and seaweed, and water taxis (Connell, 2020).